The Paris Review's Blog, page 829

April 17, 2013

If Heavy, Then Lift

Every morning, I would start the day with the Smashing Pumpkins—haunting “Disarm,” anthemic “Today.” Over and over, in a bedroom still mired in childhood, where a mound of carelessly tossed stuffed animals crept up my white wood dresser, I relentlessly played Siamese Dream. This, I thought, is how one becomes a teenager.

When the sun was at its hottest, late in the afternoon, I would stand at my front door, forehead pressed against the mesh screen, waiting for some friend’s mother to pull up in a beige Nissan and carry us to the mall. Here, I would spend hours in too-short shorts in too-cold air conditioning deliberating between pungent Plumeria or Freesia lotions at Bath & Body Works, scarfing down greasy slices of food-court pizza, and buying a hideous glittery cropped tee my mother would take one look at and matter-of-factly proclaim I would never wear. Until I was called for dinner, I’d read Seventeen, wondering if, once my dreaded braces came off, I’d be as beautiful as the young girls staring back at me with their wisps of charcoal eyeliner rimming their almond-shaped eyes, the ones who looked like they hadn’t cried since they fell off pretty pink bicycles with white baskets and streamers flowing from the handlebars. After that night’s iteration of chicken and rice, the phone would ring. For the next hour and a half, I would talk about nothing with the person I had had nothing to say to at the mall just a few hours before.

It was the summer of 1993, and I was bored. Read More »

A Bigger, Brighter Screen

Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Virginia Tusi, 1965, still from a silent black-and-white film in 16mm, 4 minutes at 16 frames per second.

Readers of The Paris Review will remember a portfolio and a novel excerpt by Rachel Kushner in our Winter issue. Now that book—The Flamethrowers—is out and earning raves (“It unfolds on a bigger, brighter screen than nearly any recent American novel I can remember,” says today’s New York Times). Click here to read our excerpt and here to see (and read about) the artworks that inspired the novel.

Bull City Summer

At Durham Bulls Athletic Park. Photo: Kate Joyce.

Unless you are a baseball adept, or familiar with Durham, North Carolina, your relationship to the words Durham Bulls may be an inverted one. Perhaps your mind flips the words to Bull Durham, the 1988 movie about life and love in the minor leagues. Kevin Costner stars as journeyman catcher Crash Davis (there was a real player by that name, long ago), who is sent to Durham to tutor the young, talented, and wild Nuke LaLoosh (Tim Robbins), a flamethrowing pitcher who is never sure where his pitches will go. Nuke spends the summer canoodling with Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon), an aging baseball groupie, before he is called up to the “Show,” the major leagues. That clears the way for Crash and Annie to become the batterymates, as baseball argot puts it, they were destined to be. It is a mellow, even melancholy consummation, a sadder-but-wiser ending to an antic, shaggy, often profane baseball tale of getting all the way to the major leagues, or just to the end of summer—to the end of a dream.

Bull Durham gets a lot right, and real minor-leaguers approve of it—my multiyear polling of ballplayers in clubhouses shows it to be the truest baseball movie: they identify with the bus-ride scenes (the minors are still known colloquially as the bus leagues), with Crash lamenting the “dying quail” difference between hitting .250 and .300 (the difference that’ll get you to the majors), and with the lecture Crash gives Nuke on how to fob off sports clichés on reporters like me.

But Bull Durham does omit a crucial detail, one that the casual viewer will probably overlook. Read More »

Challenges, and Other News

“At times of tragedy, the mind goes to certain favored zones; mine goes automatically to poetry.” Dan Chiasson offers the tested comforts of William Langland.

The Los Angeles Times brings us a nifty map of literary LA.

The most frequently challenged library book of 2012? Captain Underpants.

Bells, whistles, and animation: the so-called next generation of e-books.

Flann O’Brien’s “alleged role as author of an allegedly fake interview with John Stanislaus Joyce, father of James Joyce.”

April 16, 2013

William Wordsworth’s “Resolution and Independence”

It was Eid al-Adha, the Feast of Sacrifice, so the bazaars in Istanbul were closed. We walked along the silent streets, wondering how thirteen million city dwellers could go so quiet and how we were going to spend our leftover lira before our departing flights in a few hours. Toward the Galata Bridge, we found a commotion of doves and pigeons by the Yeni Cami.

It was Eid al-Adha, the Feast of Sacrifice, so the bazaars in Istanbul were closed. We walked along the silent streets, wondering how thirteen million city dwellers could go so quiet and how we were going to spend our leftover lira before our departing flights in a few hours. Toward the Galata Bridge, we found a commotion of doves and pigeons by the Yeni Cami.

Birds of a feather do flock together: leading from Eminönü Square was an avenue lined with animal stalls. A menagerie of birds—cranes, ducks, fancy chickens, peacocks, and pheasants—called from their cages. In other wire cages, puppies, kittens, and rabbits formed furry masses. Another set of aquatic stalls had turtle hatchlings and goldfish. Bags full of seed, dry food, and wood shavings spilled into one another—supplies for every sort of pet.

We stopped before a collection of three-gallon drums. “Prof. Dr. Sülük,” read placards at the top of all the drums, each of which was two-thirds full of cerulean-tinted water. A man stood beside the drums, resting his weight on one of them, shifting his baseball cap with the other hand, gray hair falling from underneath.

“I saw a Man before me unawares: / The oldest man he seemed that ever wore grey hairs.” This was not the Lake District, but in this busy market I thought of William Wordsworth’s “Resolution and Independence.” Facing these tiny barrels of leeches and their keeper, all I could think of was the Romantic’s leech gatherer.

Several hundred leeches writhed. They gathered like a black belt round the middle of each container, near the water’s surface. A few ambitious leeches left the waistband, inching their way toward the lid; a few fell from those curving heights to the bottom of the barrels. Read More »

Eugenides on Moshfegh

Every year, at our Spring Revel, we give three honors: the Hadada Prize, the Plimpton Prize, and the Terry Southern Prize. This year, Jeffrey Eugenides presented the Plimpton Prize to Ottessa Moshfegh.

The Plimpton Prize for Fiction is a $10,000 prize awarded to an author who made his or her debut in our pages in the previous year. Moshfegh had two stories in the Review: “Disgust” (issue 202) and “Bettering Myself” (issue 204).

Nothing is harder for a writer than getting published for the first time. The road from the bypass to the byline is paved with misery. In fact, it’s not even paved—that’s the problem: you’re stuck knee-deep in a bog, and no one cares if you ever get out.

Of equal difficulty, on the other side of the equation, is the task of finding an unknown writer. Reading through the slush pile is like looking for tigers in the jungle: they’re camouflaged not only by their stripes but their surroundings. An editor has to be unflaggingly alert and discerning, alive to any perceptible movement in the shadows. Read More »

Afterlife

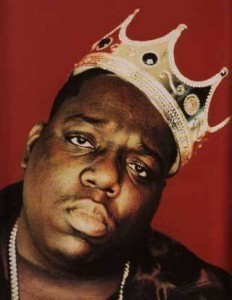

Christopher Wallace is dead, murdered in the early hours of March 9, 1997, one block from my childhood home in Los Angeles. But exactly two weeks after his death, Wallace’s alter ego, the Notorious B.I.G., rose again with the album Life After Death. Geppetto was gone, but his Pinocchio lived on.

Like Wallace, “Biggie” grew up in Brooklyn, but in Bed-Stuy rather than Wallace’s more middle-class Clinton Hill. He dealt drugs, toted four-fours, and took falls, all of which Wallace did. But Biggie was a goddamned capo compared to his dramaturge’s small-time crook. Where Wallace was really gifted—almost preternaturally so, considering he died at twenty-four—was in the constructing and performing of a character, his character. Biggie was a fiction—not so farfetched as to court credulity, but idealized, a romanticization of the writer. He was autobiographical to a point, but embellished into a Mitty-esque wish-fulfillment through whom his audience could vicariously fantasize about the good life: popping bottles and topping models.

In character, and within the strictures of the medium, Wallace could do and say things he’d never get away with as himself. With his heavy tongue he could probe the decay of poverty in a bouncy radio hit, or parody our nihilistic materialism with a club banger that made him millions, and never be in danger of hypocrisy.

Biggie was, his fans understood, the Flatbush Falstaff, dedicated to excess and frivolity, while Wallace was the mysterious magus who spawned him. Sadly, even magi are mortal. But, luckily for us, Big Poppa is forever.

Christopher Wallace is dead. Long live Biggie Smalls. Read More »

Honors Galore, and Other News

The lit Pulitzer: back and better than ever.

Granta presents its Best of Young British Novelists issue.

A gorgeous slide show of the selected writers.

Simon & Schuster is test-driving an e-book lending program with New York libraries. In addition to checking out titles, patrons will be able to buy directly, with libraries taking a cut.

“Intrigued” would be putting it too strongly, but we are mildly curious to see how Go the Fuck to Sleep gets stretched into a movie.

April 15, 2013

Hodgman on Daniels

Every year at our Spring Revel we give three honors: the Hadada Prize, the Plimpton Prize, and the Terry Southern Prize. This year, John Hodgman of the New York Times Magazine, the Daily Show, and those Mac ads presented the Southern Prize to J. D. Daniels.

Every year at our Spring Revel we give three honors: the Hadada Prize, the Plimpton Prize, and the Terry Southern Prize. This year, John Hodgman of the New York Times Magazine, the Daily Show, and those Mac ads presented the Southern Prize to J. D. Daniels.

Like the other two honors, the Southern Prize is chosen by our board. Unlike those, it recognizes writing in both The Paris Review and The Paris Review Daily. Click here to see Daniels’s latest piece from the magazine and here for his Web archive.

Good evening.

My name is John Hodgman. It’s my pleasure tonight to hand over this B-52 model airplane, which represents the Terry Southern Prize, awarded each year along with $5,000 to honor work from The Paris Review that embodies the qualities of humor, wit, and sprezzatura, which sounds like a word Lorin Stein made up and put into the Wikipedia to describe himself—an artful nonchalant, carrying himself with a a cared-for carelessness.

I’ve read J. D. Daniels’s letters from Majorca and Kentucky and I agree that they also seem effortless, which makes me furious, as they are often achingly well written.

They’re dispatches, and they feel that way, dashed off travelogues from corners of globe and memory, full of crafty rambling and quick jumps from his current home in the fancy eastern edge of Massachusetts to his first home in Kentucky, where J. D. counts out the strip malls and storefront churches and ghosts of bars lovingly like animals climbing aboard a blighted ark, to the vomit-slicked deck of an actual boat at sea, a pilgrimage he takes to leave both homes behind to fight it out while he watches Ibiza burn up in a wildfire.

And it may seem that in all this sprezzatura that his work is a little nonchalant; you don’t know what all these little flash narratives add up to, but then you’ll get one moment: a memory, say, of Daniels being strangled by his own father, whom he still loves, and the running from and returning to that moment, which he’s done ever since; you see a narrative flash like lightning, spreading quick blue light for a moment over the whole shadowy, tortured territory.

It doesn’t sound very funny, and it’s not very funny. Unless you count the part where J. D. Daniels gets strangled by his own father, which is hilarious; we know this from The Simpsons. And if you’re wondering why he’s getting the Terry Southern Prize for Humor it is because, like Southern, his work is sly, and wicked, and playful, and, most of all, it’s true.

People ask me why is the Daily Show funny and I usually say it’s because of the jokes. Because explaining humor is neither funny, fun, nor possible. But some jokes always work because they break taboos. That’s why dirty jokes work, as Albert Brooks discovered opening for Richie Havens; there’s one word you can say into a microphone that will always win over one thousand drunk Texan Richie Havens fans who hate you, and that word is a miracle word, and that word is shit. But when it comes to the Daily Show, and J. D. Daniels too, the greatest taboo-breaking is simply to say what is true, plainly, and without apology. That joke always works, even when it’s no joke. J. D. Daniels’s letters know intimately that space between the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves when we’re sitting on a bar, and the queasy, daylit truth that awaits us once we are kicked outside into the afternoon sun.

In a recent posting to The Paris Review Daily he wrote, “We know what comedy is: life is increased. Think of Rodney Dangerfield addressing the crowd at the end of Caddyshack: ‘Hey, everybody, we’re all gonna get laid!’” [Dirty joke.] And we know what tragedy is: isolation increases. I used to think that life was about winning everything, Mike Tyson once said, but now I know that life is about losing everything.”

So J. D. Daniels is a plain good writer, but not like every good writer, he is clear, he is also a very funny guy. And when he doesn’t make you laugh, it’s on purpose, and when he does, that’s on purpose, too. What better definition of humor is there?

So it’s my pleasure to offer the Terry Southern Prize to J. D. Daniels of Kentucky, Massachusetts, and the world. Congratulations, to him and to us all.

We’re all going to get laid.

Jimmy Ernst, Untitled, 1976

Since 1964 The Paris Review has commissioned a series of prints and posters by major contemporary artists. Contributing artists have included Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Louise Bourgeois, Ed Ruscha, and William Bailey. Each print is published in an edition of sixty to two hundred, most of them signed and numbered by the artist. All have been made especially and exclusively for The Paris Review. Many are still available for purchase. Proceeds go to The Paris Review Foundation, established in 2000 to support The Paris Review.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers