The Paris Review's Blog, page 828

April 22, 2013

Red and Blue

It was October, and I was alone. I lived in Greenpoint with a close friend from college, but we were rarely home, and never home together. We floated in and out of each other’s lives. We left ourselves reminders that we had both been there: wet towels tossed over the shower curtain, mugs face down in the sink.

I was reading or writing or worrying; I can’t remember, but it hardly matters. The curtains were open, and the head of the plastic owl strapped to the ledge outside of the living room window was swirling. In retrospect, I should say “swirling ominously,” but this was not unusual: it was loose and spun wildly in light breeze. What I mean to say is I didn’t think twice about anything, certainly not about the lights flashing blue-red-blue-red-blue-red-blue against the wall, until I did.

I went downstairs to take a look.

Around the corner, an intersection was cordoned off with orange police tape. Two cruisers blocked traffic. A small van had stopped in the middle, and as I approached I saw that it was empty and the hood was crushed against the windshield. Read More »

Mixed-Up Tweeters, and Other News

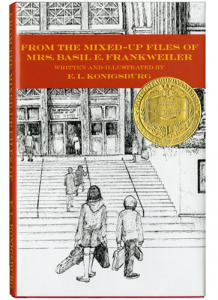

E. L. Konigsburg, author of beloved children’s titles The View from Saturday, A Proud Taste for Scarlet and Miniver, and, most famously, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, has died, at eighty-three.

Speaking of people in museums past closing hours, Whitey Bulger is the subject of another book. (Considering he is “known to be a book reader,” maybe he won’t mind too much.)

In other Boston news, The New Yorker talks literature, violence, and the Caucasus in light of last week’s tragic events.

And in case you missed this informative memo to tweeters: Chechens are not from the Czech Republic.

The 2012 LA Times Book Prize winners have been announced.

April 19, 2013

A Theory of Love

I remember sitting in red tights and buckled shoes in my childhood room as my word processor booted up. My father had taught himself DOS programming, and boxy yellow letters blinked on the gray green screen. “THIS IS KATIE RYDER’S WORD PROCESSOR. HELLO KATE.” A system-check flashed through my existing files—“/a_bad_day” (child minimalist), “/last_unicorn” (child plagiarist)—before bringing me to the composition page. My dad’s words changed slightly from week to week by mysterious means; this time, they declared: “YOU’RE READY TO WRITE KATE.”

I remember sitting in red tights and buckled shoes in my childhood room as my word processor booted up. My father had taught himself DOS programming, and boxy yellow letters blinked on the gray green screen. “THIS IS KATIE RYDER’S WORD PROCESSOR. HELLO KATE.” A system-check flashed through my existing files—“/a_bad_day” (child minimalist), “/last_unicorn” (child plagiarist)—before bringing me to the composition page. My dad’s words changed slightly from week to week by mysterious means; this time, they declared: “YOU’RE READY TO WRITE KATE.”

In Scott Hutchins’s debut novel, A Working Theory of Love, Neill Bassett Jr. communicates with his dead father through a computer. Dr. Neill Bassett Sr. committed suicide while his son was in college and left behind a tome of meticulous journals. These—painstaking and only superficially personal—are used to form the base “personality” of a computer run by a small team of scientists aiming to develop the world’s first “sentient” machine, by the standards of the Turing test. Neill’s task is to “chat” with DrBas, as the program is called, and work out the kinks, training the computer in the rules of language and interaction. Soon it begins to demonstrate inclinations and preferences—something a bit like a will—and DrBas comes to closely resemble Neill’s dead father. The two talk of Neill Sr.’s best friend; his wife, Libby; Neill Jr.’s childhood and current life—a recent divorce and a new, stunted romance with a much younger woman—all the while skirting the black hole of the computer’s knowledge: that the real Dr. Bassett killed himself in 1995, that the person Dr. Bassett is dead.

Meanwhile, in the real world, inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil has stored a warehouse room full of information about his own dead father for the purpose of bringing him back to life as an electronic consciousness. The chief inventor of the flatbed scanner and the Kurzweil keyboard synthesizer, and a millionaire many times over, Kurzweil described the Internet before its existence and accurately projected the year a computer would defeat a human chess champion. He now predicts computers will reach sentience by 2029—a point at which they will “match human intelligence and go beyond it.” This moment is sometimes referred to as the singularity—a mythic, multipurpose term, borrowed from physics and mathematics. At its most basic, the singularity is the moment when “the model breaks down”: when we can no longer know what we knew before. In a 2009 documentary about Kurzweil called Transcendent Man, Ray explains that he will live forever (through transhumanistic nanotechnology: microscopic machines that will aid in “reprogramming” our “Version 1” bodies to more perfect health), and, he says, eyes into the camera, “I do plan to bring back my father.” Fred Kurzweil’s letters, sheet music, financial ledgers, and electric bills all sit in wait. Read More »

On the Anniversary of Lord Byron’s Death

Joseph Denis Odevaere, Lord Byron on His Deathbed, 1826.

Roll on, thou deep and dark blue Ocean – roll!

Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain;

Man marks the earth with ruin – his control

Stops with the shore; – upon the watery plain

The wrecks are all thy deed, not does remain

A shadow of man’s ravage, save his own,

When for a moment, like a drop of rain,

He sinks into thy depths with bubbling groan,

Without a grave, unknell’d, uncoffin’d, and unknown.

—George Gordon Byron, from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, canto II

What We’re Loving: Works That Work

Yesterday I was handed the first issue of a Dutch magazine that bills itself as “a kind of National Geographic of design.” Oddly, the design of Works That Work (in print) leaves much to be desired: it’s the size and shape of a puffy playbill. But there is an online edition, and the features range from an interview with the translator Linda Asher to an article on battlefield cooking to an investigation of that crowd-management fad, the fly in the urinal. (Yes, it’s published in English.) —Lorin Stein

Yesterday I was handed the first issue of a Dutch magazine that bills itself as “a kind of National Geographic of design.” Oddly, the design of Works That Work (in print) leaves much to be desired: it’s the size and shape of a puffy playbill. But there is an online edition, and the features range from an interview with the translator Linda Asher to an article on battlefield cooking to an investigation of that crowd-management fad, the fly in the urinal. (Yes, it’s published in English.) —Lorin Stein

Every now and then, I go back to my copy of Musicality, a collaboration between Barbara Guest and June Felter, and this week was one of those times (maybe it’s the advent—finally!—of spring that drew me to the book). Published in 1988 by Kelsey St. Press, it combines a single poem by Guest interspersed among pages of Felter’s pencil drawings of rural landscapes—scribbled trees, grasses, and hillocks; knotted loops for clouds; and the simplest geometry to describe farmhouses. Guest’s lines likewise employ the smallest marks, the slightest movements to render nature’s, well, musicality: “Hanging apples half notes / in the rhythmic ceiling red flagged / rag clefs / notational margins / the unfinished / cloudburst / a barrel cloud fallen from the cyclone truck / they hid under a table the cloud / with menacing disc / Leafs ripple in the dry cyclonic.” It doesn’t hurt that the book’s cover stock has a very pleasing, toothy texture (Fabriano Artistico, for you paper fiends out there), so it’s doubly nice to pick up. —Nicole Rudick Read More »

Close Reading, and Other News

A sly French literacy campaign wins international plaudits. (Look again: that’s it right there!)

Writers mobilize to save Venice’s bookshops.

Sadly, Portland’s Murder by the Book is meeting an unkinder fate.

“When she went to New York [from Boston], she wasn’t thinking about the work she was going to do—she was thinking about the clothes she was going to wear.” Sylvia Plath’s month at Mademoiselle, an experience that would figure in The Bell Jar.

Well, this was clearly never going to bother anyone: “10 Talented Female Authors I Wouldn’t Kick Out of Bed for Writing About Crackers.” (He has a type.)

April 18, 2013

Help Wanted

We were extremely intrigued by the following classified, which advertises work for a “writer and editor.”

We were extremely intrigued by the following classified, which advertises work for a “writer and editor.”

Watson Adventures seeks a writer and editor of cultural scavenger hunts. Must have excellent sense of humor, fanatical attention to detail, slavish devotion to deadlines. Must be flexible and a team player, with good interpersonal skills. Please send published examples of your writing and 3 examples of hunt questions suitable for our style of hunt. Full time, salary $40k per year, plus health insurance, 401k plan, optional dental. Send resume and clips to writer@watsonadventures.com.

Guessing there are a few qualified applicants at my alma mater.

An Enormous Amount of Pictures: In the Studio with Miriam Katin

Miriam Katin’s first book, We Are On Our Own, told the story of her escape, as a child, from the Nazi invasion of Budapest. An attempt to come to terms with her past, to reconcile faith and history, and an elegantly stark tribute to her mother, that graphic memoir was also a beautifully realized work of art. The story it told, retained all the wonder and pain of a child’s impressions, tempered by experience and wisdom.

Miriam Katin’s first book, We Are On Our Own, told the story of her escape, as a child, from the Nazi invasion of Budapest. An attempt to come to terms with her past, to reconcile faith and history, and an elegantly stark tribute to her mother, that graphic memoir was also a beautifully realized work of art. The story it told, retained all the wonder and pain of a child’s impressions, tempered by experience and wisdom.

In her new book, Letting It Go, Katin grapples with her son Ilan’s decision to move to Berlin, a city she identifies with Nazis. An investigation of the price survival exacts, it is also an unabashedly personal investigation of family dynamics, a sequel of sorts to We Are On Our Own.

On a recent March afternoon, I visited Katin, who bears an uncanny resemblance to her cartoon-self, in her Washington Heights apartment, her home for the past twenty-two years and the site of her studio in what used to be her son’s room. She made tea for me and coffee for herself, set out a plate of freshly baked, sugar-dusted cookies, and, with a softly melodious Hungarian accent, recounted the process of working on her books, her feelings about contemporary Berlin, her nine-year-stint living on a kibbutz, her love of the city (“I’m an asphalt flower. Nature is okay, it’s good. But I like asphalt,” she said), and what it was like to be the oldest employee at MTV, where she worked on Beavis and Butthead and Daria.

The first book stood on its own, a story from A to Z, a start and a finish. Now this story, this new book, is so personal. And it really depends on the first one. I think it would be hard, just getting to it, to say, That’s interesting. It’s more fragmented and extremely personal. And vulgar. And dirty. I didn’t hold anything back. Read More »

Perspective

Poets Without Clothes, and Other News

Talk about truth in advertising: meet Poets Without Clothes. [NSFW]

Check out this nifty animation of a 1996 DFW interview.

George Orwell’s northern Indian birthplace is being turned into a memorial … for Gandhi.

What are libraries doing with old books? Lots of things.

Pew: “About seven in ten of those who used a library over a twelve-month period did so to borrow print books or to browse the shelves.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers