The Paris Review's Blog, page 824

May 3, 2013

What We’re Loving: Trains, Stalkers, and Virgins

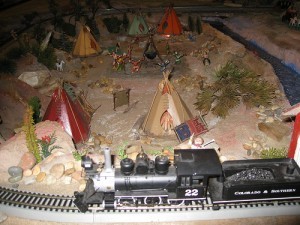

In the 1930s, thirteen-year-old Frank Moshinskie started to build a miniature town for his toy trains. Now run by his son and made up of hundreds of buildings, hand-carved figures, and replicas of national landmarks, Tiny Town Trains is a beloved attraction of Hot Springs, Arkansas. If, like me, you can’t make it down any time soon, check out this amazing video from the Oxford American. It’s no wonder Tiny Town! was nominated for a National Magazine Award; it truly conveys the magic of the miniature, and the definition of labor of love. —Sadie Stein

In the 1930s, thirteen-year-old Frank Moshinskie started to build a miniature town for his toy trains. Now run by his son and made up of hundreds of buildings, hand-carved figures, and replicas of national landmarks, Tiny Town Trains is a beloved attraction of Hot Springs, Arkansas. If, like me, you can’t make it down any time soon, check out this amazing video from the Oxford American. It’s no wonder Tiny Town! was nominated for a National Magazine Award; it truly conveys the magic of the miniature, and the definition of labor of love. —Sadie Stein

Last month, Text Publishing launched its Text Classics in the United States, reprints of long out-of-print books, many of which have never been available here. Their first list is made up primarily of books by Australian novelists, and I think I can count on one hand the number of Australian novels I’ve read. So I seized on Elizabeth Harrower’s The Watch Tower, originally published in 1966. What a discovery! Harrower’s voice in this book is disconcerting at first: almost fatigued, as though she knows that everything to come is fated to be so and there’s little to do but tell the story. And her characters—two young sisters—likewise passively accept the events that befall them. This fatalism is absorbing, though, as you watch the women move slowly through a comatose state into a kind of awakening. In fact, the story reminded me at times of A Doll’s House—namely, in the younger sister’s internal striving for selfhood and independence—but the long tale of the sisters’ subjugation is far more excruciating than what Ibsen imagined. —Nicole Rudick Read More »

The Funnies, Part 5

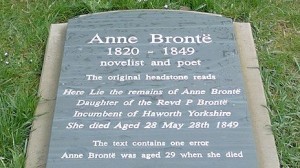

Anne Brontë Gets a Headstone, and Other News

Anne Brontë finally gets an accurate headstone. (The original misstated her age.)

“For heaven’s sake, what kind of question is that?” Claire Messud bristles at the notion that characters should be likable.

The Atlantic is launching a line of e-books.

HBO gives Olive Kitteridge the miniseries treatment.

In other film news, can you distinguish an Atwood novel from a Hollywood thriller?

May 2, 2013

We Are Made of Memories: A Conversation with Mia Couto

Born in 1955 in Mozambique, to Portuguese immigrants, Mia Couto is widely considered one of the foremost wielders of the Portuguese language. He has written more than twenty books that have been translated into at least as many languages, and those translated into English since 1990 have garnered him a dedicated Anglophone following. Although Couto’s fiction varies widely, he frequently deals with Mozambique’s civil war, which erupted in 1977, two years after he turned twenty and his nation gained its independence from Portugal. His recurrent use in his work of surreal effects has led many critics to liken his fiction to Latin America’s magical realism, a label at which he bristles.

Born in 1955 in Mozambique, to Portuguese immigrants, Mia Couto is widely considered one of the foremost wielders of the Portuguese language. He has written more than twenty books that have been translated into at least as many languages, and those translated into English since 1990 have garnered him a dedicated Anglophone following. Although Couto’s fiction varies widely, he frequently deals with Mozambique’s civil war, which erupted in 1977, two years after he turned twenty and his nation gained its independence from Portugal. His recurrent use in his work of surreal effects has led many critics to liken his fiction to Latin America’s magical realism, a label at which he bristles.

The Tuner of Silences , brought into English by Couto’s longtime translator David Brookshaw and published this year by Biblioasis, tells the story of Vítalico, a father who has dragged his children to an abandoned Mozambican nature preserve after the horrifying death of his wife. As Couto explores the nature of Vítalico’s regime and its eventual collapse, he delves into frequent obsessions: the construction of identity and the role that memory and language play in that process.

Recently, over e-mail, I discussed Tuner, influences, labels, and the curious provenance of Couto’s first name in our e-mail correspondence.

You’ve mentioned the Angolan writer José Luandino Vieira and the Brazilian João Guimarães Rosa as two influences on your understanding of the Portuguese language. What sorts of cultural influences from within Mozambique have you drawn from?

I usually refer to Luandino and Guimarães Rosa as those who inspired me most, but the most important influences on my writing come from those I can’t identify, persons that populated my childhood, my hometown in the Indian ocean, the neighborhood where I was born and where I started to dream about other places and other lives. So, ironically, the main source of inspiration of my writing came from the nonwriting world. Oral culture is still dominant in Mozambique, and the ability to convert reality into stories is still very alive here, even in the urban areas. Storytelling is not exclusively a skill of the griots—the common citizen shares this capacity, telling stories not just with words but with their whole body, using dance and songs and poetry as a unique language. Read More »

Hell Is Other Cats

Henri the Existential Cat waxes philosophical on the price of literary fame.

Counter Culture

“I would have said, You’re getting there. Now that you said, ‘You nailed it,’ we can never go to the Bluebird again.”

“I would have said, You’re getting there. Now that you said, ‘You nailed it,’ we can never go to the Bluebird again.”

“I was trying to give him a little encouragement,” Clancy said.

“Well, you fucked us.”

The first restaurant we liked in Iowa City was the Bluebird. It’s also the only decent cappuccino in town. We’d go every morning, order our fried eggs, and get three cappuccinos each. The waitresses had to make the cappuccinos themselves. We ordered so many that some of them began to dislike us. One in particular, whom we called Lower East Side. But all of them tried to get away before we had a chance to say, Could we get another.

All, that is, except for a Swingers-looking guy, slightly pudgy, whom we were convinced was gay until Clancy complimented his signet ring. Read More »

The Funnies, Part 4

Unpoetic Day Jobs, and Other News

Day Jobs of the Poets.

Have you seen James Patterson’s personally-funded “book industry bailout” ads?

By a hair, print still trumps digital in the UK.

“How I overcame snobbery to self-publish an e-book.” One man’s story.

Gillian Flynn: “That’s exactly my goal: to make spouses look askance at each other.”

May 1, 2013

The World of Tomorrow

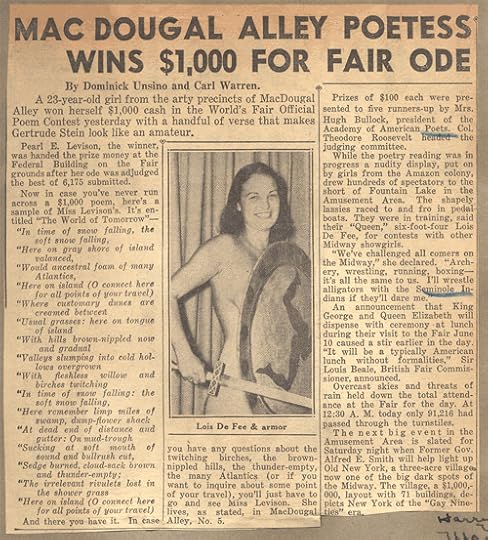

On April 30, 1939, the New York World’s Fair opened in Flushing Meadows. You’re probably familiar with the fair’s iconic deco aesthetic and modern marvels, but did you know there was poetry, too? The Academy of American Poets sponsored a contest to find the Official Poem of the New York World’s Fair, with contestants encouraged to write on the theme “The World of Tomorrow.” The prize was $1,000; the judges were poets William Rose Benét, Louis Untermeyer, and, oddly, Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

The winner was Pearl Levison and “World of Tomorrow.” (Of the five runners-up, three are also called “The World of Tomorrow.” One is titled “Tomorrow, America,” while Rosalie Moore opted for the economical “Tomorrow.”) A New York Times article from May of 1939 describes Levison as “a 23-year-old poet who has lived all her life in this city,” while the Daily News specifies that the winner hails from “the arty precincts of MacDougal Alley” in Greenwich Village.

The poem (which is ten pages long) may be found .

(And no, as close readers will have noticed, the woman pictured is not the poet but “showgirl” Lois De Fee, engaging in “a nudity display” of archery, wrestling, running, and boxing.)

How William Eggleston Would Photograph a Baseball Game

Photo: Leah Sobsey/leahsobsey.com

I am at war with the obvious. —William Eggleston

Not long ago, I wrote about the formal and spiritual affinities between baseball and the genre of music called power pop. Both observe an “unwavering, repetitive adherence to form” while pushing hard against strict, self-imposed formal limits, thus “mak[ing] music out of a very precise, narrow, angular geometry.”

Then, on April 8, the day before the Durham Bulls’ inaugural home game of the season, Bull City Summer’s first guest photographer, Alec Soth, gave a talk at the North Carolina Museum of Art, where his show “Wanderlust” is currently on view. He began by showing a slide, not of his own work, but of Flowers for Lucia by the photographer William Eggleston. Eggleston “hangs over me,” Soth confessed, before showing a picture he made of Eggleston himself.

These disparate elements—power pop and Eggleston—came together for me just a few hours after Soth’s talk, when the documentary film, Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, about the seminal power-pop band, closed Durham’s annual Full Frame Documentary Film Festival. (Eggleston appears in the documentary, so ravaged and slurred by years of hard living that the filmmakers resort to subtitling their interview with him in order to make him intelligible.) To make a nakedly baseball-centric comparison, you could say that Big Star was a can’t-miss major-league prospect that somehow missed: led by the late Alex Chilton, the band should have found international fame but barely got out of Memphis, the Triple-A city it called home. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers