The Paris Review's Blog, page 823

May 7, 2013

Happy Birthday, Angela Carter

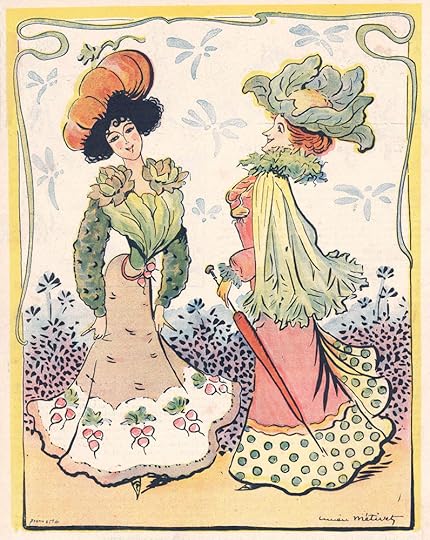

La Couture Comique

Lucien Métivet’s name may not be familiar to many contemporary readers or art aficionada, and placed alongside that of his friend and fellow art student Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec it may seem, by comparison, thoroughly obscure. A century ago, however, Métivet was a hugely popular belle epoque artist, celebrated not so much for his paintings as for his posters, book and magazine illustrations, advertising art, and—especially—his humorous drawings. He embodied, in the 1890s and after, an idea that the world has only now begun to embrace: that a cartoonist and fine artist can be one and the same.

His 1893 poster portraying chanteuse Eugénie Buffet as a woman of the cold streets not only advertised her performances at the club Ambassadeurs; it immortalized her stage persona and made Métivet’s name at the age of thirty. It remains as much a part of the visual legacy of the era as Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters of Buffet’s mentor Aristide Bruant. But Métivet’s stock in trade for the decades that followed was drawing, swiftly and prolifically, for publication—whether supplying covers and cartoons for Le Rire (Laughter), the most popular humor journal in Paris, or dozens of illustrations for an edition of Maupassant or Balzac, or for a lesbian-themed erotic novel (or two) by Pierre Louÿs, or for the first two adventure-filled volumes of Paul d’Ivoi’s Voyages Excentriques, a hugely successful (and conspicuously deliberate) competitor to Jules Verne’s Les Voyages Extraordinaires.

Quantity and artistic quality, however, rarely go hand in hand, especially under deadline, and an undiscriminating catch-all collection of L. M.’s work is liable to make a poor impression, cluttered as it is with examples of the slapdash and the merely adequate. That the appreciation of a prolific artist requires selectivity is no surprise; the surprise, instead, is the insouciance of the exceptions, the fact that among drawings printed as amusing diversions a century ago there are those that still charm, still resurface with a wink and a smile to inspire a reciprocal smile across a divide of so many generations. The survival of the sunny and comic, as if blithely stepping over world wars, cultural upheavals, and time itself, is always a kind of miracle.

And now it is spring again, a time when ladies, and at least a few gentlemen, think of fashion. Métivet’s Modes Potagères (Vegetable Fashion), a full-page color illustration from the April 6, 1901, issue of Le Rire included a brief text as caption, which encourages us to note, and savor, such features as the lettuce bodice, pickle sleeves, and artichoke ruffle on the outfit of the dark-haired beauty in the pumpkin toque; and the beetroot princess dress with its green-pea flowerbed and cardoon collar with curly-endive neck ruff on the elegant lady of the cauliflower hat and carrot umbrella. With its precisely enumerated whimsicality, cheerful colors, and the evident and so-human pride and pleasure in the faces and postures of the models, this is an image perpetually floriferous. Read More »

Wild and Crazy Libraries, and Other News

“It is definitely not your mother’s Donnell,” says the New York Times, ominously, of the new plans for the Fifty-Third Street branch of the New York Public Library.

Famously reclusive eighty-seven-year-old national treasure Harper Lee is suing literary agent Samuel Pinkus over the copyright for To Kill a Mockingbird. Says Lee’s lawyer, “Pinkus knew that Harper Lee was an elderly woman with physical infirmities that made it difficult for her to read and see … Harper Lee had no idea she had assigned her copyright.”

The new Goodreads archnemesis (our word), Riffle, is live.

Martin Amis apparently “views the Brooklyn hipster scene as populated by conventional posers.”

If fictional mothers wrote hypothetical parenting books—because why not?

May 6, 2013

Kent Johnson’s / Araki Yasusada’s / Tosa Motokiyu’s “Mad Daughter and Big-Bang”

Pen names have long been a means for writers to inhabit another identity—to attain privacy, assume the acceptably literate gender, or play with the freedom of a psychic unburdening. But at what point does a pseudonym become obfuscation, transgression? What happens when a poem of witness—a poem set in the aftermath of the August 6, 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, a poem more compelling than many of its peers for its haunting, even oblique and morbid surrealist humor—is in fact written by a middle-aged white community college professor named Kent Johnson, rather than a hibakusha, or actual Hiroshima survivor?

Kent Johnson’s / Araki Yasusada’s / Tosa Motokiyu’s “Mad Daughter and the Big-Bang”

Pen names have long been a means for writers to inhabit another identity—to attain privacy, assume the acceptably literate gender, or play with the freedom of a psychic unburdening. But at what point does a pseudonym become obfuscation, transgression? What happens when a poem of witness—a poem set in the aftermath of the August 6, 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, a poem more compelling than many of its peers for its haunting, even oblique and morbid surrealist humor—is in fact written by a middle-aged white community college professor named Kent Johnson, rather than a hibakusha, or actual Hiroshima survivor?

In the Beginning

In the Year of Our Lord, 2000, I was a freshman at the University of Chicago. Come the (locally) famous scavenger hunt, I was charged by older residents of Breckinridge House with the task of transcribing, by hand, the entire Oxford English Dictionary. I regret to inform you that my efforts didn’t garner our team many points. But it did give me a unique appreciation for the achievements of Phillip Patterson.

Phillip Patterson, you see, has hand-written a copy of the King James Bible. And more than that, it’s a work of art. Says the Los Angeles Times,

A 63-year-old resident of Philmont, N.Y., a town near the Massachusetts border, may be an unlikely scribe for the Bible. He is not especially religious, for one thing, though he does go to church. A retired interior designer whose battles with anemia and AIDS have often slowed his work, he began the monumental task mostly out of curiosity.

In 2007, Patterson’s longtime partner, Mohammed, told him about the Islamic tradition of writing out the Koran by hand. When Patterson said that the Bible was too long for Christianity to have a similar tradition, Mohammed said, well, he should start it.

The project took him four years. See more images of Patterson’s transcription, documented by Laura Glazer, here.

Proust, Lost in Translation

The first volume of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time: Swann’s Waywas published almost exactly a hundred years ago. Its opening lines make one thing inescapably apparent: Proust’s style is inimitable; there is much more to it than long sentences, pauses for reminiscence and brittle cookie breaks, and whatever other tropes readers have associated with Proust. It is a style that tussles with our notion of literary temporality itself. Over the last century, countless translators have struggled with these famous opening lines:

Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure. Parfois, à peine ma bougie éteinte, mes yeux se fermaient si vite que je n’avais pas le temps de me dire: « Je m’endors. »

Nobody seems to be able to agree whether to translate the verb of the principal clause as a conditional or a past participle, because while in French it is obviously the latter, it seems to act as the former. We’ve had various degrees of “went to bed early,” “used to go to bed early,” “would go to bed early,” each meaning more or less the same thing, but none hitting the nail directly on the head.

Scholars have found these lines, at once, undeniably charming and a huge pain to work with.

But in this seemingly untranslatable sentence, even among translators—whose very job it is to take troublesome idioms and phrases and grammatical twists and make them legible and appropriate, and to do so by imparting as much of Proust’s style and as little of their own as possible—there is so much variety that it raises another important question: How would this sentence have been handled by other writers? Read More »

Hemingway Moves North, and Other News

More than two thousand papers and other materials from Ernest Hemingway’s Havana estate, Finca Vigia, are being transferred to the John F. Kennedy Library.

Everything you did not know about the Desmond Elliott Prize, which is a prize.

William S. Burroughs’s daily routine: methadone, lemonade, knife-throwing.

One hundred academics write an open letter to the British education secretary; get taken to task for bad grammar.

Taschen wants to corner the market on “big, collectible books.” (The formal industry term.)

May 3, 2013

Andrea Hirata, Jakarta, Indonesia

A series on what writers from around the world see from their windows.

Since my childhood, I have rarely had the power to control where I can be. Life has not given me many choices. But after writing my first novel, I started thinking of leaving my place of employment, where I worked for almost twelve years. Though writing is a very risky way of making a living in Indonesia, I finally resigned from my job, and now I’ve got this strange feeling of relief.

The decision to write full-time meant I couldn’t afford to buy a house. A friend kindly offered me the use of his apartment in a thirty-six–story building full of newlywed couples in the southern area of Jakarta. I didn’t like my working space at first, but the scenery and everything going on outside have worked their magic on me. From a building right in front of my windows, I can observe the speed of the sunrises and sunsets. The voices of children playing, laughing, yelling, and crying on the playground crawl up to the eighth floor, where I write. Their voices sound so innocent from a distance. —Andrea Hirata

The Paris Review Wins National Magazine Award

Over the years The Paris Review has been nominated several times for a National Magazine Award, and even won a couple, but we never won the prize for General Excellence—until last night. The other finalists in our circulation category included The New Republic and Mother Jones. We are very proud to be in their company—and can’t imagine how the poor judges reached their decision. We will take it as a vote of confidence in the poetry, fiction, and essays of today, and in the power of literature to hold its own, even in an election year.

We send our warmest thanks and congratulations to the writers and artists whose work is recognized by this high honor. You deserve it.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers