The Paris Review's Blog, page 831

April 10, 2013

No Amusement May Be Made

“I forgot my camera,” I said to Wayan, the tour guide on our bicycle trip. He had, moments earlier, announced “Kodak moment!” as we slowed for our first stop—a lookout point over a mist-filled valley of tiered rice terraces. Two Swedish girls, two Dutch girls, and an English girl posed at the precipice, photographing themselves with evidence of having been to a beautiful vista in northeastern Bali.

“Oh no,” said Wayan. “Well, you will keep it in your head.”

My head already resembled a home interior from the TV show Hoarders, more so now that the compulsive caretakers within had made it their mission to collect as many Indonesian words as possible. I knew the word for “beautiful,” but lacked the impulse to document beauty. If I had to build a new mental wing to house the active volcano Mount Batur, so be it.

Still, imagined disappointment from intimates ate at me. It seemed I could not cement a solid habit of picture-taking, and in this way I felt I failed the demands of our time at every picturesque turn, successful only in my failure to do the thing I should have, in retrospect, done—done for friends, for family, for Facebook.

The feeling left me as the day progressed. The Swedish girls took cheeky snapshots of themselves knee-deep in the mud of a rice paddy outside a small village. “Dirty feet!” they cried, flashing smiles.

“It’s like a spa treatment,” one joked, stepping out with wet muck on her calves.

“I used to help my father do this when I was a boy,” said Wayan. He crouched down to plant a few sprouted seedlings.

“It must be kind of fun for little kids to be in the mud and the water,” said one of the Swedes. “Like playing.”

When we stopped at a coffee plantation, the Dutch girls took pictures of a caged civet, whose digestion and excretion of raw beans is essential to the production of expensive, earthy kopi luwak. Pictures of old Balinese women in their family compounds chopping and peeling bamboo into usable strips. Pictures of a five-hundred-year-old banyan tree. I would later persuade my fellow tourists to e-mail me these pictures, so that I could pass them off as my own when I returned.

At a particularly stunning view of the volcano, the English girl said to me, “Bet you wish you’d brought your camera now.”

“There’s a lot of things I wish,” I said in my head, keeping that there as well.

“What do you do all day? Just sit around?” Read More »

Happy Birthday, Great Gatsby!

“Reserving judgements is a matter of infinite hope.” —F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, published on this day in 1925

Decadent Prose: An Interview with Translator Kit Schluter

It is 1891. Marcel Schwob, a well-know author, meets a “girl of the streets” in the rain, in a slum of Paris. Her name is Louise, and she is sick with tuberculosis. He takes her home and cares for her. He writes her stories—fairy tales—which she loves. They grow close. Louise shows Marcel the beauty of innocence. Two years later, she dies. He is crippled by his grief. For six months, he doesn’t write.

It is 1891. Marcel Schwob, a well-know author, meets a “girl of the streets” in the rain, in a slum of Paris. Her name is Louise, and she is sick with tuberculosis. He takes her home and cares for her. He writes her stories—fairy tales—which she loves. They grow close. Louise shows Marcel the beauty of innocence. Two years later, she dies. He is crippled by his grief. For six months, he doesn’t write.

Then, he publishes The Book of Monelle, a groundbreaking work of decadence. An assemblage of fairy tales, nihilist philosophy, and aphorisms tightly woven into a tapestry of deep emotional suffering, it becomes the unofficial bible of the French Symbolist movement. Schwob influences writers and thinkers from Alfred Jarry to André Gide to Stéphane Mallarmé to Jorge Luis Borges and Roberto Bolaño. Translated obscurely into English in 1927, The Book of Monelle all but falls into obscurity shortly thereafter.

Now, thanks to a new translation by Kit Schluter, Monelle is once again available in the States, with a biographical afterword. In addition to his translation work, otherwise focused on Pierre Alferi, Amandine André, and Danielle Collobert, Schluter is a poet and an editor at CLOCK Magazine and O’Clock Press, and will begin his graduate studies at Brown in the fall. We met to talk at a café in New York’s West Village.

Why don’t you start by telling me how you found Schwob’s work and what drew you to it?

I studied in Paris for a little bit in early 2010, and went to work in Tours, a city southwest of Paris, for about a month in the summer. I lived with my friend Sylvain Burgaud, who the translation is dedicated to, and a dear friend Bruno Chartier. Sylvain and I worked in these vineyards outside of town, trimming grapevines for about ten hours a day. Then we’d go to this bar at night called Le Serpant Volant, or the Flying Snake. The bartender, a wonderful person named Omar, when he found out that we were translating each other’s poems, offered us the second floor of the bar as a translating space in the evenings. Sylvain and I were translating almost every night, my first experience with the frenzy of translation and its conversations, obsessing over single words.

One weekend, we went out to his house in La Roche Bernard, and we were translating a poem of mine, which is called “Journals.” We got to a passage and he asked, Have you ever heard of Marcel Schwob? I said, No, definitely not. And he said, Well, you need to read him, because you write a lot like him. I said, Okay, fine. Show me the book. I was really excited, and a little flattered.

So, he went and got the book. I read one sentence, or two sentences, from “The Words of Monelle.” It was, “And Monelle said again, ‘I shall speak to you of moments,’” but in French, and something like, “Love the moment. All love that lasts is hatred.” It’s a little adolescent, isn’t it? But it really spoke to me, so I said, “Sylvain, will you loan me this book? I want to translate it into English.” But he wouldn’t lend me the book because he’d lent it out so many times before to people who didn’t return it. When he asked for it back, they had already lent it to someone else! That’s my favorite part of the whole story—that Sylvain couldn’t lend me the book because he had lost it so many times by way of lending. Read More »

Rumors of the Death of the Book Greatly Exaggerated, and Other News

Peter Workman, “known in the publishing world as a genially offbeat entrepreneur of nonfiction, with an on-base percentage—in publishing terms—worthy of Cooperstown,” has died. Workman hits included The Preppy Handbook, What to Expect When You’re Expecting, and The Silver Palate Cookbook.

Barnes & Noble gets into the self-publishing game with NOOK Press.

The death of the book, like doomsday, has been predicted since time immemorial.

But: “If reading is going be all digital in fifty years, so be it.” Tim Waterstone, founder of the eponymous bookstore chain, is philosophical.

Listen to John le Carré read from his new novel.

April 9, 2013

Paula Fox, Fighting Perfection

Our Spring Revel will take place tonight! In anticipation of the event, the Daily is featuring a series of essays celebrating Paula Fox, who is being honored this year with The Paris Review’s Hadada Prize. The following is excerpted from an essay that originally ran as the introduction to Desperate Characters.

A book that has fallen, however briefly, out of print can put a strain on even the most devoted reader’s love. In the way that a man might regret certain shy mannerisms in his wife that cloud her beauty, or a woman might wish that her husband laughed less loudly at his own jokes, though the jokes are very funny, I’ve suffered for the tiny imperfections that might prejudice potential readers against Desperate Characters. I’m thinking of the stiffness and impersonality of the opening paragraph, the austerity of the opening sentence, the creaky word “repast”: as a lover of the book, I now appreciate how the formality and stasis of the paragraph set up the short, sharp line of dialogue that follows (“The cat is back”); but what if a reader never makes it past “repast”? I wonder, too, if the name of the protagonist, “Otto Bentwood,” might be diffi cult to take on first reading. Fox generally works her characters’ names very hard— the name “Russel,” for instance, nicely echoes Charlie’s restless, furtive energies (Otto suspects him of literally “rustling” clients), and just as something is surely missing in Charlie’s character, a second “l” is missing in his surname. I do admire how the old- fashioned and vaguely Teutonic name “Otto” saddles Otto the way his compulsive orderliness saddles him; but “Bentwood,” even after many readings, remains for me a little artificial in its bonsai imagery. And then there’s the title of the book. It’s apt, certainly, and yet it’s no The Day of the Locust, no The Great Gatsby, no Absalom, Absalom! It’s a title that people may forget or confuse with other titles. Sometimes, wishing it were stronger, I feel lonely in the peculiar way of someone deeply married.

Let the Memory Live Again

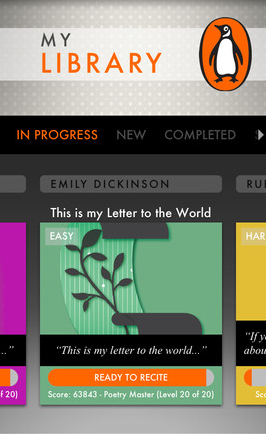

I remember in sixth grade a substitute teacher asked the class if we knew any poems by heart. Did I! I favored the assembled company with a little Wordsworth, some Blake, and, because I was cool like that, a soupçon of Ogden Nash. Needless to say, everyone was really impressed, and I was incredibly popular for the rest of the school year. My penchant for oversize flannel jumpers only helped!

I remember in sixth grade a substitute teacher asked the class if we knew any poems by heart. Did I! I favored the assembled company with a little Wordsworth, some Blake, and, because I was cool like that, a soupçon of Ogden Nash. Needless to say, everyone was really impressed, and I was incredibly popular for the rest of the school year. My penchant for oversize flannel jumpers only helped!

As usual, I was ahead of my time: Penguin Classics has released an amazing app called Poems by Heart, a memorization game that helps users learn poetry. For me the virtues of rote learning were their own reward. But for those who require slightly more incentive, the app provides a scoring program, a recording mechanism, and original art. Flannel jumper optional.

End of an Era

Annette Funicello’s death, at age seventy, occurred one day after the Sunday night premiere of season 6 of Mad Men. The pilot of the show, you will recall, was set in the year 1960: the same year Annette Funicello segued from The Mickey Mouse Club (which aired from 1955 to 1959) to her career as a singer and performer in a passel of musicals produced in Hollywood, before the British Invasion transformed youth culture. Mad Men’s narrative trek through the decade now compels its protagonists to face the increasingly surreal and riotous mayhem of America’s social and political panorama in the late 1960s: the shift from “We Shall Overcome” to black power. Our total plunge into Vietnam’s quagmire. The generation gap. Two assassinations in 1968: the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Plus, of course, the incipient women’s movement. All that, set against a sound track ruled by the Doors, the Stones, and the White Album incarnation of the Beatles, whose aural evolution defined the whole epoch.

According to one school of thought, the “real” 1960s did not unfold until well after JFK’s death, definitely after the onset of the Beatles’ psychedelic phase in 1966 (“Strawberry Fields Forever” in lieu of “She Loves You”), and eons after the earlier half of the decade was sweetly personified by Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon in a slew of beach movies, replete with “Twist”-era rock-and-roll dance music. Of course, it was that earlier part of the 1960s—the Annette Era, so to speak—that first created Mad Men’s buzz. The meticulous re-creation of the fashions, manners, and mores of 1960–63 reminded (or taught) viewers how drastically different the first part of the decade was from the latter. Read More »

The Digital Public Library, and Other News

Welcome, Digital Public Library of America!

Neruda, as promised, has been exhumed. Watch this space for toxicology reports.

The Kindle publication of a Cornish-English children’s book marks a victory for minority languages.

Books stolen by the Nazis, like other precious objects, are still being returned.

“Speaking of Grindr, who knew it would prove to be such an effective marketing tool for an author who is trying to make his mark in the LGBT community?” On unconventional marketing.

April 8, 2013

Singing the Blues

Documentary filmmaker Les Blank has died, at age seventy-seven. In memoriam, a clip from one of his many films devoted to traditional American music, The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins.

The Way We Were

It’s a busy time here at The Paris Review. Tomorrow is our annual gala, the Spring Revel, and in two weeks, we move our little office from the Tribeca loft that has been our home for the past eight years to a new space in Chelsea. Boxes are piled high; loose books and papers are strewn about; scissors and tape will not stay in the same place.

It’s a busy time here at The Paris Review. Tomorrow is our annual gala, the Spring Revel, and in two weeks, we move our little office from the Tribeca loft that has been our home for the past eight years to a new space in Chelsea. Boxes are piled high; loose books and papers are strewn about; scissors and tape will not stay in the same place.

Last week, we were clearing a bookshelf of its contents and came across a batch of small, white booklets. The Paris Review: Twenty Year Index, Issues 1–56, they were titled; they appeared to be lists of everything that had been published during the magazine’s first twenty-three years, and were put aside for recycling. Flipping through them later, we realized that the booklets also contained an introduction by George Plimpton, a founder of the magazine and its editor for the first fifty years of its history.

A minihistory of the Review, full of forgotten anecdotes and remembrances, the introduction is particularly poignant as we prepare for these two (for us) significant events. George recalls early offices of the magazine, angering Ernest Hemingway with brash interview questions, the many volunteers who flocked to the Review and gave a fledgling publication a boost. He writes—hilariously—of Revels past: “The Revels were memorable affairs, with so much effort spent by staff members in entertaining the guests that very often the fund-raising aspects of the events were forgotten. The extravaganza on Welfare Island (although 750 people turned up) actually lost money—and primarily because a piano was left out in a glade and was ruined in a post-party rain squall.”

Here’s to a Revel that’s just as fun, but minus the rain.

An Index is simply a statistical compilation which does not suggest the quality of the material listed, or the critical standards that guided its selection. It can only record the appearance, not the gist, of William Styron’s introductory “letter” which set forth the magazine’s principles in the first pages of the first issue—a letter addressed to John P. C. Train, the managing editor, who in questioning Styron’s manifesto elicited a reply which turned out to be lively and pertinent and a considerable improvement on the original document.

An Index can list the people who have worked for the magazine, but it cannot acknowledge their individual contributions. Their number has been vast. The Paris Review has traditionally published a masthead longer by far than Fortune magazine’s. Indeed, so many volunteers turned up to help in the early days that the managing editor referred to the females by the collective name of “Apotheker” (Joan Apotheker … Mary Apo …)—from the German for “druggist,” which he apparently thought appropriate. Their male counterparts were referred to as “Musinskys”—named after the first of their breed who came to work for a Paris summer. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers