The Paris Review's Blog, page 833

April 4, 2013

Good Little Girls, and Other News

“Good little girls ought not to make mouths at their teachers for every trifling offense. This retaliation should only be resorted to under peculiarly aggravated circumstances.” Mark Twain’s advice to little girls, illustrated by Vladimir Radunsky.

Speaking of: the always fun Wodehouse Prize shortlist is posted.

“British writing will be far less incisive and fun when he stops.” Tim Martin pays tribute to Iain Banks, who just revealed his terminal illness.

“Banks manages to be both popular and profound,” says Stuart Kelly in The Scotsman.

April 3, 2013

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, 1927–2013

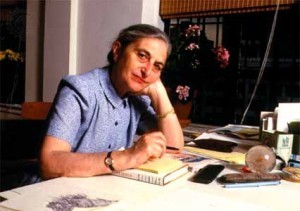

It was announced this morning that Ruth Prawer Jhabvala died today at her home in Manhattan, at the age of eighty-five. Jhabvala is best known as an award-winning screenwriter for Merchant Ivory Productions. Together, with the late producer Ismail Merchant and the director James Ivory, she helped make twenty-two films. Perhaps, like me, you have watched her adaptation of E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View dozens of times, which garnered her an Academy Award for screenwriting in 1986. Or perhaps you, too, lusted after a Kelly bag after watching her adaptation of Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce. Over the course of three decades, she helped project the stories of writers such as Forster, Henry James, Evan S. Connell, Jean Rhys, and others onto the screen. Often, though not always, these films captured a lost era. One where women were chaperoned to Italy, where a stolen kiss on a hilltop could cause scandal, where class was never directly discussed, and fortune was hunted like prey. And today we must mourn the loss of a kind of filmmaking that took care to not appear superficial in obsessing over the past. (Much as Merchant Ivory always got the look right, one never said that the best part of the movie was the costumes. Look, for example, at Hollywood’s latest adaptation of Anna Karenina.) As Jhabvala explained to Philip Horne around 2001: “The main purpose is that I have such a good time. I mean, think of all that marvelous material. Just think of spending all that time in The Golden Bowl and the other James and Forster books we have done. But especially Henry James because he has such marvelous characters and he has such strong dramatic scenes. You just put your hand in and pull them out.”

It was announced this morning that Ruth Prawer Jhabvala died today at her home in Manhattan, at the age of eighty-five. Jhabvala is best known as an award-winning screenwriter for Merchant Ivory Productions. Together, with the late producer Ismail Merchant and the director James Ivory, she helped make twenty-two films. Perhaps, like me, you have watched her adaptation of E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View dozens of times, which garnered her an Academy Award for screenwriting in 1986. Or perhaps you, too, lusted after a Kelly bag after watching her adaptation of Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce. Over the course of three decades, she helped project the stories of writers such as Forster, Henry James, Evan S. Connell, Jean Rhys, and others onto the screen. Often, though not always, these films captured a lost era. One where women were chaperoned to Italy, where a stolen kiss on a hilltop could cause scandal, where class was never directly discussed, and fortune was hunted like prey. And today we must mourn the loss of a kind of filmmaking that took care to not appear superficial in obsessing over the past. (Much as Merchant Ivory always got the look right, one never said that the best part of the movie was the costumes. Look, for example, at Hollywood’s latest adaptation of Anna Karenina.) As Jhabvala explained to Philip Horne around 2001: “The main purpose is that I have such a good time. I mean, think of all that marvelous material. Just think of spending all that time in The Golden Bowl and the other James and Forster books we have done. But especially Henry James because he has such marvelous characters and he has such strong dramatic scenes. You just put your hand in and pull them out.”

This is because Jhabvala read as a writer. Despite—or perhaps because of—her many successes, she called herself a novelist first and foremost. And with reason. Heat and Dust was awarded the Booker Prize in 1975. She was given a MacArthur in 1984, and her short stories were published in The New Yorker throughout her career. “I was never interested in adapting classics at all,” she told Horne. “I’d written four novels. I was never interested in film. Never. I never even thought of it. I never thought of it until Merchant and Ivory came to India and filmed one of my books—they said: ‘Why don’t you write the screenplay?’ I said I’d never written a screenplay and I hadn’t seen many films because I was in India by that time and hadn’t really had any opportunity to see new films or art films or classic films or anything. So they said, ‘Well, try. We haven’t made a feature film before.’ So that was really my introduction into film.”

Thessaly La Force is a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and coauthor of My Ideal Bookshelf.

One Ring to Rule Them All

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.

Such is the object that starts Bilbo Baggins’s quest and, later, marks the glowing center of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. And some speculate that it was based on a real Roman ring, currently on display at a Hampshire mansion.

Originally discovered by a farmer in the late eighteenth century in what the Guardian terms “one of the most enigmatic Roman sites in the country,” the ring was presumably sold to the family who owned the great house the Vyne.

It was a strikingly odd object, 12g of gold so large that it would only fit on a gloved thumb, ornamented with a peculiar spiky head wearing a diadem, and a Latin inscription reading: “Senicianus live well in God.” A few decades later and 100 miles away, more of the story turned up: at Lydney in Gloucestershire, a Roman site known locally as the Dwarfs Hill, a tablet with an inscribed curse was found. A Roman called Silvianus informs the god Nodens that his ring has been stolen. He knows the villain responsible, and he wants the god to sort them out: “Among those who bear the name of Senicianus to none grant health until he bring back the ring to the temple of Nodens.”

Here’s where Tolkien comes in. When archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler reexcavated Lydney in 1929, he consulted Professor Tolkien about the god’s unusual name; both men were apparently struck by the fact that the name appeared on both ring and curse.

Whether or not you believe this to be the inspiration for the One Ring, you can judge for yourself: it is on view, along with a copy of the curse and a first edition of The Hobbit, at the Vyne.

Insurrection: An Interview with Rachel Kushner

I filled up half a notebook preparing for my interview with Rachel Kushner, whose second novel, The Flamethrowers, arrives this week. [It was excerpted and served as the inspiration for the portfolio in our last issue.] The notes are wide-ranging and imprecise, a record of the experience of reading this intellectually voracious book and trying to keep up with it. There are descriptions of American land art, scraps of World War I history, digressions on Italian counterculture in the late seventies. There are facts about those same years in New York, sometimes appreciating a particularly lovely observation, sometimes just noting what has changed (“on the Manhattan side, the Williamsburg Bridge had steps”). There are names, so many names: Aldo Moro, Virginia Tusi, Grifi and Sarchielli, Robert Smithson, and a hundred more. There are isolated flashes of pop-culture ephemera, like an otherwise blank page with “Jane Fonda wins an Oscar” written in the middle. That these elements, incoherent in my notebook, not only connect in Flamethrowers but create a dense and beautiful and polyphonic Bolaño-esque harmony meant that Ms. Kushner, by the time our interview rolled around, had started to seem somewhat miraculous.

Perhaps appropriately for an author concerned with the self-conscious production of ideas and images, Ms. Kushner spoke to me on Skype from LA, where she lives, as she put it, “incognito.” Her disguise on this particular day consisted of a black sweater and a few auburn highlights in her brown hair. When she answers questions, she has a habit of looking down past the camera, and her elaborate, delicate responses—complete with qualifications and footnotes—make it seem that she must be consulting a notebook propped open in the corner of the room. She isn’t.

The Flamethrowers spans a hundred years and follows multiple sets of characters across two countries, but I think it can be separated into three strands. Reno moves from Nevada to New York in the late seventies to be an artist, Italy is upended during the Years of Lead, Italian motorcyclists form a gang in World War I. Did you start out looking for a large and polyphonic book?

I like the way you divide up the three strands.

Is that not how you would divide them?

Well, at first there were two spheres—New York in the seventies and Italy in the seventies. And I knew they may have had some kind of en-tissuing or overlap, but I didn’t know what it was, and I didn’t want to reduce it by linking them in forced or artificial ways. The only viable manner of figuring out how they were connected—and weren’t—was to write the novel. Read More »

Times-ian Haiku, and Other News

Foxing and diapers: learn the anatomy of a book.

A Tumblr blog displays incidental New York Times haiku (not all of which mention nature, but still).

The AP has dropped illegal immigrant from its stylebook. The New York Times (haiku generators) are considering following suit.

A Jane Austen guide to thrift. Retrench!

“I am officially Very Poorly”: Iain Banks reveals that he has terminal cancer.

April 2, 2013

In the Margins

Last Christmas, my brother, Charlie, gifted me with a piece of paper on which was scrawled, “Good for 1 tattoo.” This was perhaps a slight improvement over his gift of the year before (“Good for one dinner with Charlie. On you”) and arguably approaching his 2010 present-giving apex (autographed baby pictures of himself.) But it was still a pretty low-risk investment on his part; Charlie knew I was never going to break down and actually ink a permanent Dimples on my shoulder, something I’d flirted with through the years. “Just a small, classic Dimples,” I would explain to my mother. “A tribute!” And she would say, “Munnie would be appalled. And so would Yumma.”

Last Christmas, my brother, Charlie, gifted me with a piece of paper on which was scrawled, “Good for 1 tattoo.” This was perhaps a slight improvement over his gift of the year before (“Good for one dinner with Charlie. On you”) and arguably approaching his 2010 present-giving apex (autographed baby pictures of himself.) But it was still a pretty low-risk investment on his part; Charlie knew I was never going to break down and actually ink a permanent Dimples on my shoulder, something I’d flirted with through the years. “Just a small, classic Dimples,” I would explain to my mother. “A tribute!” And she would say, “Munnie would be appalled. And so would Yumma.”

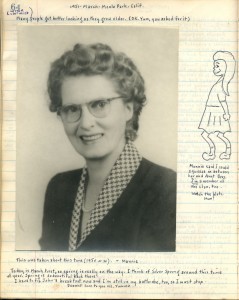

As might be clear from the nomenclature, we have entered the Land of the WASP. Yumma, my grandmother (née Ruth Mary), was the daughter of Munnie (Margaret), whom I am said to, but do not, resemble. Munnie was a legendary figure, a mother of five who managed to render even the hardships of the Depression magical with her ingenuity, her creativity, her sense of fun. A hard worker who held things together after her husband died, she maintained a busy, cheerful existence until her death from cancer in her sixties.

As might be clear from the nomenclature, we have entered the Land of the WASP. Yumma, my grandmother (née Ruth Mary), was the daughter of Munnie (Margaret), whom I am said to, but do not, resemble. Munnie was a legendary figure, a mother of five who managed to render even the hardships of the Depression magical with her ingenuity, her creativity, her sense of fun. A hard worker who held things together after her husband died, she maintained a busy, cheerful existence until her death from cancer in her sixties.

Munnie, with Dimples

Although Munnie died many years before I was born, she has always been a vivid presence to me, kept alive by Yumma’s stories of cream-puff swans and Halloween parties, and by the Scrapbook. The Scrapbook is a remarkable thing: two volumes in which Munnie hand-copied every scrap of correspondence she and my grandmother ever exchanged and bound them, with photographs and newsclippings and tracings of any drawings, into two large volumes, each 300 pages long. Munnie made one of these for each of her five children. My father calls the resulting tomes the Least Jewish Thing Ever Created. Read More »

Paris Review Nominated for Two National Magazine Awards

On the eve of celebrating our sixtieth birthday, The Paris Review is up for two National Magazine Awards: Fiction and General Excellence. Our fiction finalist is Sarah Frisch, whose story “Housebreaking” appeared in issue 203.

On the eve of celebrating our sixtieth birthday, The Paris Review is up for two National Magazine Awards: Fiction and General Excellence. Our fiction finalist is Sarah Frisch, whose story “Housebreaking” appeared in issue 203.

These nominations are the latest in a series of recent plaudits. Last month, we received seven nominations for the Pushcart Prize. We also had a story (“The Chair,” by David Means) chosen for The Best American Short Stories and an essay (“Human Snowball,” by Davy Rothbart) selected for the year’s Best Nonrequired Reading.

This week, New York magazine placed our new issue in the top quadrant of its famous, feared Approval Matrix, while Adam Sternbergh, blogging for the New York Times, called it “great … great … great.” He singles out “a great, long interview with Mark Leyner,” the Art of Fiction with “New York literary icon Deborah Eisenberg,” and “a great new poem from Frederick Seidel”; plus, “you’ll look great toting The Paris Review,” thanks, presumably, to our great cover.

You Take Your Love Where You Get It: An Interview with Kenneth Goldsmith

Kenneth Goldsmith’s writing has been called “some of the most exhaustive and beautiful collage work yet produced in poetry.” Goldsmith is the author of eleven books of poetry, founding editor of the online archive UbuWeb, and the editor of I'll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, which was the basis for an opera, Trans-Warhol, that premiered in Geneva in 2007. An hour-long documentary on his work, Sucking on Words, was first shown at the British Library that same year. In 2011, he was invited to read at President Obama’s “A Celebration of American Poetry” at the White House, where he also held a poetry workshop with First Lady Michelle Obama. Earlier this year, he began his tenure as the first-ever Poet Laureate of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Kenneth Goldsmith’s writing has been called “some of the most exhaustive and beautiful collage work yet produced in poetry.” Goldsmith is the author of eleven books of poetry, founding editor of the online archive UbuWeb, and the editor of I'll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, which was the basis for an opera, Trans-Warhol, that premiered in Geneva in 2007. An hour-long documentary on his work, Sucking on Words, was first shown at the British Library that same year. In 2011, he was invited to read at President Obama’s “A Celebration of American Poetry” at the White House, where he also held a poetry workshop with First Lady Michelle Obama. Earlier this year, he began his tenure as the first-ever Poet Laureate of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

I recently sat down with Goldsmith to discuss his new book, Seven American Deaths and Disasters.

Since your practice emphasizes the value of the selection process over the creation process, how do you choose what to include and exclude from Seven American Deaths and Disasters?

I began with the assassination of JFK, which is arguably the beginning of media spectacle, as defined and framed by Warhol. His portrait of Jackie mourning iconizes that moment forever. Although he made Marilyn’ss, he never memorialized her death, thus it never entered into the realm of media spectacle in the same way. From JFK, I naturally proceeded to RFK, an eyewitness account of his shooting at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. It’s an incredible linguistic document—you really feel the newsman’s struggle to find words to describe what is unfolding before his eyes. John Lennon is taken from a cassette tape made by someone scanning the radio the night of and days following his assassination, which feels like an audio document from a lost time. Space Shuttle Challenger is from a TV broadcast of the event and its long, weird, silent aftermath. Columbine is straight transcript of a harrowing 911 call. The World Trade Center, the longest piece in the book, is from several sources—talk radio, news radio, color commentary—stitched together into a multichapter epic, thus mirroring the gargantuan scale of the event. And Michael Jackson is from a catty FM station, where the shock jocks have no problem cracking jokes and making racist comments at his expense. Read More »

The Bookstore of the Year, and Other News

Oxford, Mississippi’s amazing has been named the PW Bookstore of the Year.

All the book industry April Fool’s Day pranks—from a 52 Shades imprint to the Big Six becoming a Big One—seem depressingly plausible.

Buck up! Here are seven pranks and tricks from literature.

You can take a cruise with Margaret Atwood. The novel she’s promoting, MaddAddam, is a dystopian tale described as “unpredictable, chilling and hilarious,” all words we like applied to our cruises, too.

BuzzFeed is launching a long-form reads section, which the editor characterizes as “BuzzFeed for people who are afraid of BuzzFeed.” We imagine the fearless are also welcome.

</>

April 1, 2013

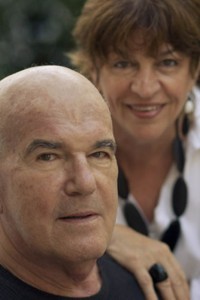

Marie Chaix and Harry Mathews at La Maison Française

Here’s one we won’t be missing: tomorrow evening, at 7:30 P.M., join Marie Chaix and Harry Mathews as they discuss writing, translation, and collaboration at NYU’s Maison Française.

Read more about their story here!

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers