The Paris Review's Blog, page 77

July 21, 2022

Speculative Tax Fraud: Reading John Hersey’s White Lotus

Rison Thumboor from Thrissur, India, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

I’m defeatist when it comes to taxes (meaning: I don’t understand deductions and pay whatever TurboTax tells me to), but I’m fascinated by those who aren’t. In 2001, for example, eighty thousand Black Americans filed for reparations with the IRS. Some made this their actual business. For $500, you could pay a self-taught financial advisor named Vernon James to apply on your behalf for a “Black Investment Tax Credit,” as he did for more than three hundred clients. James, who is Black, had a capacious “yes, and” attitude that bound together the case for reparations with workaday “Taxation is theft” libertarianism. Speaking to CBS in 2002, James asserted that Americans, whether Black or white, didn’t have to pay up come April. “The IRS took money from slaves. They are taking money from Americans. That is an investment. They have a right to get it back.” The IRS cut a number of claimants their requested checks, ranging from $40,000 to $100,000 per return and totaling more than $1 million. On realizing what had happened, the agency swiftly demanded their money back. James was sent to prison for six and a half years for tax fraud.

I discovered James in the midst of a depressive spell—that is, post my filing in 2015. It was a summer of right-wing memes about white slavery. After Dylann Roof’s attack on a church in Charleston renewed opprobrium of the Confederate flag’s public prominence, Southern Cross supporters began trotting out claims about Irish ancestors in American bondage. “At some point, you just have to get over it,” a Mississippi man told a Washington Post reporter at a rally in support of the banner of Dixie, the you being Black people, the it being slavery’s legacy.

It was also the summer of Rachel Dolezal. Sometimes, especially when you’re broke, your brain attempts a haphazard alchemy with the elements at hand: why not appropriate and invert James’s enterprise? One could set up a fake service, analogous to James’s: the White Inheritance Tax Credit, for which, for a mere $500, the supposed descendants of Irish slaves could apply—only, rather than filing their IRS Form-2439s on their behalf, one would just keep the service fee. The WITC has remained a speculative exercise. Every year after tax season—while recovering from the handover of my ill-begotten gains—I’ve found myself instead doing some ritual tinkering with a half-formed novella about a Vernon James figure serving white customers. (He’s usually white in this telling, for some reason, though he doesn’t have to be—perhaps it’s a nod to Dolezal.)

Over time, I’ve compiled a five-page document collating my research that I should probably retitle. This year, I made it through the reading list in SHIT ABOUT WHITE SLAVERY.docx to John Hersey’s 1964 novel White Lotus. Like many works of alternate history, the book concerns an American populace vanquished, the victor in this instance not Hitler’s Germany or Hirohito’s Japan but warlord-era China. The titular narrator recounts her experiences following the U.S. defeat in the “Yellow War,” beginning with her capture as a teenager in Arizona, where her village is ransacked by a group of white jazzbo musicians in a Packard touring car, blasting “Stormy Weather.” She’s marched to Los Angeles, where captured whites are billeted in abandoned film lots before being shipped across the Pacific. In Hollywood she sees a Chinese person for the first time, describing his skin as “the underside of the stretching foot of a desert snail” and “the color of curds.”

White Lotus lives through a compressed timeline of the struggle for Black freedom, as transposed from the United States to the Middle Kingdom before Communist rule. After her enslavement and renaming, she lives in domestic servitude in Beijing, picks cotton and tobacco in the south, sharecrops tea after the Emperor frees the slaves while under the violent thrall of a Chinese Ku Klux Klan called the Hall, and participates in a Great Migration back to the capital, where she experiences a version of the Harlem Renaissance. Hersey depicts the slaves’ struggle to reclaim whiteness itself, as both hue and creed: most memorably, in a prolonged passage about a milk-plumed fighting cock named Bad Hog. Armed and nonviolent paths toward white liberation are both represented, the latter encouraged by a priest named Runner who tells his flock, “We must be better than they are in their own terms.” The novel is bookended by the equivalent of a sit-in, in which White Lotus perches silently on a single leg in the “Sleeping-Bird Method” in face-to-face defiance of the cruel Governor K’ung. Yet when the governor retreats, White Lotus feels not victory but a puzzling fear, and the novel ends with a query: “What if someday we are the masters and they are the underdogs?”

What if, indeed! Hersey, best known as the author of Hiroshima, makes no mention of White Lotus in his Art of Fiction interview, in which he describes growing up in China as the son of missionaries and playing in a string quartet with jazz record producer John Hammond. But he speaks of reporting from Mississippi during 1964’s Freedom Summer and cites the feeling “that the situation of the black in America had a kind of urgency” as his motivation for writing The Algiers Motel Incident, which concerns the killing of three Black teenage boys by law enforcement in the Detroit Riot of 1967.

“You are trying to make flesh and blood of things that are remembered,” Hersey says of writing fiction. “It’s absolutely essential to make the past concrete. There have to be real, palpable objects, things seen, things heard.” White Lotus’s meticulous thought experiment in making a nonpast concrete, then, wasn’t meant to inculcate white chauvinism but to make real for white people the situation of those American “underdogs” who had actually been enslaved. This, despite nearly seven hundred pages of Caucasian suffering containing not a single Black person. (There is one mention of nonwhite Americans, a simile featuring a creeping plant brewed by the Indigenous to make a psychedelic tea.)

Reviews were mixed upon publication, but even now some readers seem convinced of the novel’s insights as to race relations, as well as geopolitics. Per a few select if representative Amazon reviews: “It tells of the injustice that slavery causes for any race of people and I also think it brought me down a notch or two when I was a teenager thinking that just because I was white and had it all that nothing like slavery could happen to me.” (Cathy, 5/5 stars.) “It taught me what it must be like to be a slave.” (Terry, 5/5 stars.) “THIS BOOK TELLS ABOUT CHINA TAKING OVER THE USA AND ENSLAVING AMERICANS IN CHINA. GOOD READ BUT IN PRESENT CONTEXT FRIGHTENING.” (HELPS, 5/5 stars.)

I myself was nonplussed, neither thrilled by Hersey’s invocation of a Chinese global century nor convinced that I now understood what it meant to be a slave. (In White Lotus’s parlance, I’d be a “mixie,” a Chinese-white equivalent of the tragic mulatto trope.) Rather than adding “flesh and blood” to an alternate history, each new instance in Hersey’s exhaustive series of translations of real historical events merely reiterated, ad nauseam, the book’s originary proposition: what if white people had been slaves?

As regards my own novella: if I do ever finish it, I’ll likely report any income I make off of racial speculation. (Dolezal didn’t, omitting tens of thousands of dollars of revenue from the sale of her memoir In Full Color as she applied for food and child care assistance; unlike Vernon James, she avoided trial for fraud, instead paying $9,000 in restitution and performing 120 hours of community service.) My progress is halted each year, however, by a failure of imagination—in the sense that reality seems to be catching up with mine. The conceit feels decreasingly novel, and I wonder if I’ll be beaten to the punch, perhaps by the likes of that man in Mississippi, who might treat White Lotus’s concluding line not as speculation but as a rallying cry. Why wouldn’t this country’s growing intertwinement of white revanchism and QAnon-style conspiratorial thinking produce a consensus reality powerful enough for some Americans to flock to fill out their own IRS Form-2439s and turn a fictional history not concrete but liquid—as in cash?

Matthew Shen Goodman is the author of “Lording,” published in issue no. 24o of the Review.

September Notebook, 2018

At my old job, I wrote descriptions of objects; at my new job, I write descriptions of talks, concerts, classes, Jewish holiday services, and other events.

Once I was in the business of selling matter. Now I am in the business of selling time.

But how to use it?

*

Parable of Uncle Martin

September 2, 2018

1:13 P.M.

Dear Uncle Martin,

Just wanted to drop you a quick note to wish you a very happy birthday—100 is a big one! Apologies for the belated note, though I’m sure you were inundated that day. I hope this finds you well and that we can see each other again soon.

Lots of love,

Dan

September 3, 2018

1:26 P.M.

Dear Dan: Thank you for the greeting. I just read your Dumpster poem. Congratulations. I will be learning how to interpret your style of poetry. Across the street from where I live, there was recently a dumpster, into which all the furniture, house cleaning equipments, lamps, tools, furniture, books, were being tossed. I knew those neighbors well. Although the debris never existed in close association before, they now did. Examined closely, as by an anthropologist, they revealed an entire type of life.

For some reason, I was always interested in poetry. In fact, the only book I ever kept after graduating from high school was “The Golden Treasury,” a book of old English poetry. So, it was only a matter of time before one of my parents’ greatgrand whatevers would be a poet. Excelsior! Love, Martin

September 4, 2018

11:31 A.M.

Dear Martin,

Thank you so much for this lovely note, and I’m delighted that you read the poem. I’ve heard that there’s been a recessive poetry gene in our family for some time—my dad tells me that my grandpa Harry used to love reading Keats, a favorite of mine as well—and I seem to remember you telling me at some point about the Golden Treasury book.

On a related note—I’m currently working on a long scrapbook poem of sorts, very different from “Dumpster” or really anything else I’ve written, which includes (among other things) pieces of overheard dialogue and lots of found language that I myself did not write. Think of it as a collage. I wonder how you’d feel about me including some portion or all of your previous email in the scrapbook poem (credited to you of course). It’s an experiment, so it might never come to anything, or it’s possible that someday down the road I would publish it in a book—too early to tell. If this is confusing or you’d prefer I not include it, it’s completely fine—just say so and I’ll leave it out. But if you grant permission I’d love to include it. Just let me know what you think. In any case thank you again.

Love,

Dan

September 5, 2018

12:07 P.M.

Dear Daniel: You can quote me it you wish. I just read a poem by Wisława Szymborska entitled “The Stagecoach.” In a sense, a stagecoach is a dumpster of people, and she gets inspiration from it. Love, Martin

*

Weep in relation to x.

Weep adjacent to x.

Weep for x.

X is weeping.

*

If you ever feel lonely, remember that somewhere someone is making millions of dollars off of a self-help book entitled Deep Work. The author of this book believes that if you could just not look at your phone, you would not only be less of an idiot, but also a millionaire.

Turn off your phone? I find this compelling not only because it’s in a book, but also because it’s an author who in book are believing it. And here’s the even more million-dollar question.

Are we brain to work deepest of all with phone pre-inside brain?

In my book you will learn how. Please take a moment to silence your phones.

*

Sunlit, obsequious, and revoltingly basic.

*

Parable of Labor Day

At Rockaway Beach I run into a colleague from the job I lost last year. She tells me that after everyone had been fired, she had continued on as a “transitional copywriter,” which meant a customer service and shipping agent, the company’s only employee other than the CEO. I asked her how our former boss was doing. “I don’t know,” she said. “About six weeks ago he stopped responding to my emails. Ghosted! I called the parent company, and apparently he no longer works there. I’m the only one left.”

We regarded one another in the sand as two who would never have occasion to meet again save for serendipity, smiled, and waved goodbye.

*

He suffered the music of the proximate tweens with quiet dignity.

Avoid no vocabulary, raise no suspicion.

*

He reached a pitch of exaltedness such that no amount of sherbet could calm him down.

*

Entire birds, consisting of a black dot and two lines. Imagine.

*

So at long last, the natural resource that capitalism extracts most brutally of all, on every scale and by every metric—from the hour we spend decoding latent aggression on social media to the boring novel we feel compelled by taste to read to planetary collapse—is time.

*

The mirrored surface of that cantor’s bald head as he sings the Kaddish.

*

Today was Yom Kippur.

Cast your lint into this river.

Give your lint to this intern.

*

Parable of Ariel

“I hit my peak as a writer in third grade. Those stories were good. They were about real things. Ferrets, immigration, poachers in Wyoming, the industrial revolution, the bread and roses strike of 1812, the state of Texas. You’ve seen the anthology my mom put together.”

*

Worms woweth under dew, soil, and cloud. All my life I wondered at what. But at what they woweth, I know now.

Evil and beauty need each other.

*

Questions to which the answer is “night.”

With what instrument does one best see the instrument?

What time is the right time?

Which watchman?

*

A chiseled chest of song.

*

Gasoline: the final land art.

*

This science is suspenseful!

*

Parable of a Bell

I am ringing a call bell at a bar, a bell I purchased that morning, debating whether or not to use it in the reading of this poem at the Poetry Project. At previous readings I have knocked on hard surfaces to signify breaks. This bell sounds sharp and clear, lovely really, though admittedly a little loud. Eric says he prefers the knocking, as it sounds like fate at the door; Paola says ringing the bell sounds like I’m asking for service. Do I want to sound like that? I don’t. But what if I mute it just so, like this, with a folded napkin. They listen as the paper absorbs the outer edge of the ring. A good solution. I ring again and again to test it. A woman at the bar does not turn to me, but speaks so I can hear.

“Every time that bell rings an angel loses its fucking wings.”

In the end I decide to knock.

*

This ill star.

*

Parable of the New Job

“Did your weekend have a highlight?” I ask my new colleague. The office lights flicker. Coffee steams from her cup. She does not drink it.

“The highlight of my weekend was time.”

Daniel Poppick is the author of The Police and of the National Poetry Series winner Fear of Description.

July 20, 2022

E. E. Cummings and Krazy Kat

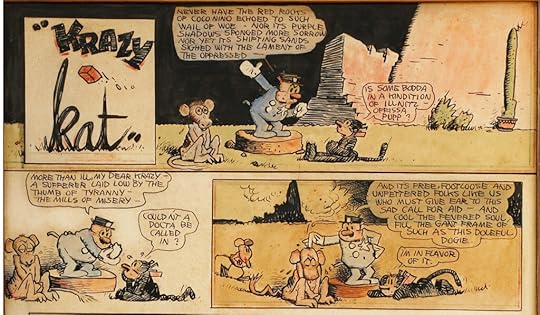

Krazy Kat by George Herriman.

In 1910, a mouse named Ignatz first beaned Krazy Kat with a brick. The plot of this comic strip, centered on a “heppy go lucky kat,” is simple. Krazy Kat loves Ignatz Mouse. Officer Pup loves Krazy Kat. Ignatz Mouse hits Krazy over the head with a brick; Officer Pup pursues and usually arrests Ignatz Mouse; Krazy, to whom the brick seems to be a sign of love, is ecstatic. A small heart pops up above his head. The cartoonist, George Herriman, twisted and tangled the three-lover triad and cat-mouse-dog triad and spent thirty-one years retying the same surreal knot. You know what will happen in any strip of Krazy Kat—the same sequence reoccurs eternally—but somehow there is still room for unexpected delight.

E. E. Cummings was one of the Kat’s biggest fans. In 1922, he wrote from Paris to request clippings from friends in America. (“Thank you moreover for a Kat of indescribable beauty!” he wrote to an obliging friend.) In his 1946 introduction to the first edition of the collected strips, Cummings wrote that the brick unleashed joy within the “ultraprogressive game” of the real world, with its preestablished rules, of which it flouted the most sacred: “THOU SHALT NOT PLAY.” (Winnicott defines play as “the continuous evidence of creativity, which means aliveness.”) Herriman gives pleasure without the instant gratification of a punch line, undercutting the expected gag trajectory. The brick hurtling across the page doesn’t end the joke; games end, but play is infinite. There is no winner, and if there is, it is Krazy, who, for private reasons, interprets the brick as love.

The strips were published daily in Hearst newspapers between 1913 and 1944, but Herriman never repeated himself. Or at least, the strip didn’t look the same. The improbable landscape of Coconino County, Arizona, where the strip is set, seems almost to move on the page. Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes and a Herriman megafan, wrote, “Mountains are striped. Mesas are spotted … The horizon is a low wall the characters climb over … The moon is a melon wedge, suspended upside down.” Herriman juggled all the elements the form allowed: language (hyperbolic Creole, Spanish, Yiddish); comedy (existential, vaudevillian, burlesque); and gender—the Kat is neither he nor she, but rather, as Herriman put it, “a pixie,” whose pronouns switch within a strip and occasionally within a sentence, making the possible configurations and miscommunications of the comic infinite. Somehow, in this static form, nothing is inanimate. Only a killjoy would try to extract too much meaning from Krazy Kat, but it’s not surprising that Herriman created art that depended on fluid identities. Twenty-seven years after Herriman died, the sociologist Arthur Asa Berger published the birth certificate on which Herriman was registered as “col,” for “colored.” Herriman was born in New Orleans in 1880 to a mixed-race family that moved to Los Angeles ten years later and from then on passed as white. Herriman had plenty of reasons to keep it up, including his job at the Los Angeles Examiner, a publication that regularly outed people for their race, and the fact that he lived with his white wife in a neighborhood with racist housing covenants. Telling different stories at different times, Herriman explained his light brown skin as the result of years spent living under the Greek sun to some people and claimed various ancestries—often French—to others. (As Krazy tells Ignatz, “Lenguage is that we may mis-unda-stend each udda.”)

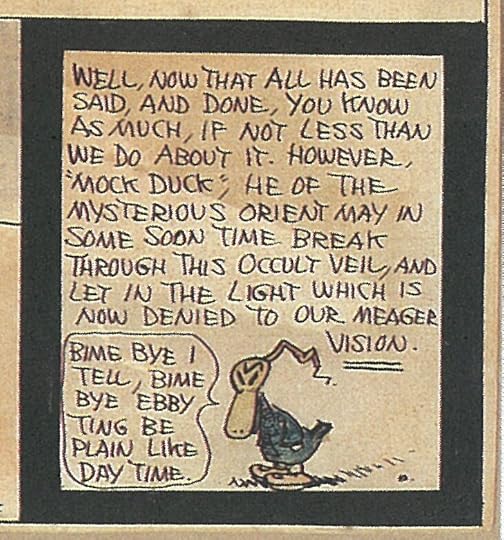

The Kat had a cult following among the modernists. For Joyce, Fitzgerald, Stein, and Picasso, all of whose work fed on playful energies similar to those unleashed in the strip, he had a double appeal, in being commercially nonviable and carrying the reek of authenticity in seeming to belong to mass culture. By the thirties, strips like Blondie were appearing daily in roughly a thousand newspapers; Krazy appeared in only thirty-five. The Kat was one of those niche-but-not-really phenomena, a darling of critics and artists alike, even after it stopped appearing in newspapers. Since then: Umberto Eco called Herriman’s work “raw poetry”; Kerouac claimed the Kat as “the immediate progenitor” of the beats; Stan Lee (Spider-Man) went with “genius”; Herriman was revered by Charles Schulz and Theodor Geisel alike. But Krazy Kat was never popular. The strip began as a sideline for Herriman, who had been making a name for himself as a cartoonist since 1902. It ran in “the waste space,” literally underfoot the characters of his more conventional 1910 comic strip The Dingbat Family, published in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Evening Journal. Hearst gave Herriman a rare lifetime contract and, with his backing, by 1913 the liminal kreatures had their own strip. Most people disliked not being able to understand it. Soon advertisers worried that formerly loyal readers would skip the strips and miss the ads. Editors were infuriated by devices like Herriman’s “intermission” panel, which disrupted the narrative by stalling the action. There was also just the sheer strangeness of some of his characters, such as Mock Duck:

Panel from Krazy Kat by George Herriman. Digitized by Joël Franusic.

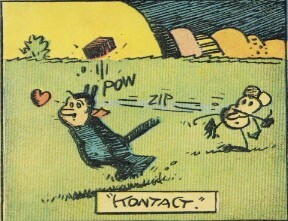

For Cummings, who, with his flagrant anti-intellectual stance, privileged what he called “Aliveness” above all else, Charlie Chaplin was the only artist to rival Herriman. But technology disrupted both Chaplin’s and Herriman’s idiosyncratic work. At the introduction of sound in film in 1927, Chaplin said that the “spontaneity of the gags had been lost,” but what he really lost was his control of time. Sound erases distance; there was no longer a delay in which the incongruity between seeing and comprehending could bloom. In his essay “What People Laugh At” (1918), Chaplin noted “the liking of the average person for contrast and surprise in his entertainment.” Both Herriman and Chaplin orchestrated meticulously timed, silent dialogues between images and words. Slapstick—a word that originally referred to two pieces of wood joined together, used by pantomime clowns to make loud noises—is, in their work, a deliberately clumsy cleaving of the relationship between words and images. If people could explain themselves, there would be no time to revel in ludicrous situations, as when in The Kid, Chaplin, caressing the hand of a policeman’s wife, is accidentally caressed by her husband.

T. S. Eliot commented that Chaplin had escaped “in his own way from the realism of the cinema and invented a rhythm.” This rhythm in Chaplin’s work is a personal tempo. Chaplin has perfect control of his own time; his bodily movement controls the rate at which the story unfolds. Rhythm is an acoustic metaphor for a visual form with its own internal logic, and it is evident too in Krazy Kat, where it creates an elastic, almost spatial experience of time rather than a narrative one. Chaplin and Herriman’s work presents discrete moments that appear as part of the same present, although they are not serial narrative; they create strange, self-contained temporalities.

Many criticized Chaplin for resisting the lure of sound, but in a 1940 letter, Cummings wrote, “I like Charlie Chaplin as is and my lightning raw”—no accompanying thrum of thunder. Cummings understood that sound could kill play; he once said, “Not all of my poems are to be read aloud.” The 1922 ballet Krazy Kat: A Jazz Pantomime, based on Herriman’s strip, was a flop for the same reason: it robbed the reader of the internal, private experience of making connections between frames. (Likewise, a series of attempts to animate Krazy was a disaster.) It’s funny when Krazy misreads signs we can see, because there’s an ironic distance; both meanings are there at once. With sound, Herriman’s wit was reduced to a series of quips and the crash of a brick hitting a cat.

Panel from Krazy Kat by George Herriman. Digitized by Joël Franusic.

I first encountered the Kat in my early twenties, trying to wean myself off Cummings’s love poetry by reading his letters. Heartbroken and too raw for new experiences, I took comfort in the strange repetition of each strip. In 2020, in between lockdowns, I started prowling the internet again for the Kat. The strips felt very of the moment; I couldn’t escape my awareness of how quickly time was passing and how few things it took to fill it up. I was bored, but in the acutely happy moments, eating with friends, or when my friend’s baby held a phone to her ear and then to her doll’s ear—a baby on a phone holding a baby on a phone—I didn’t want anything to change. No news was good news. Repetition seemed like a space in which creativity could thrive.

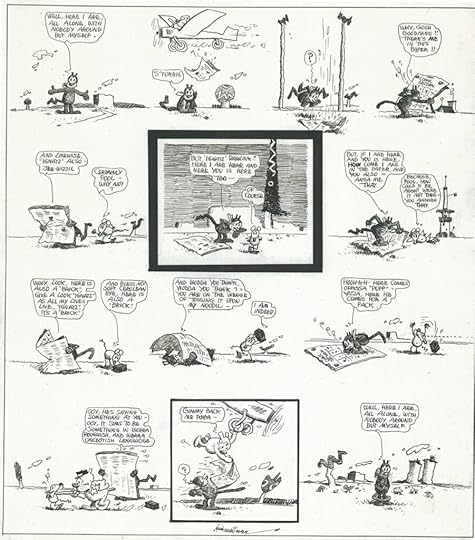

Part of the reason the strip didn’t catch on more widely is that it isn’t easy to read quickly. Because of the changing layout, scattered phonemes, and rotation of themes in Herriman’s strips, you can’t read them left to right or in a hurry. Spatially, the strip defies the linear progression of a gag, both in the way we read—sometimes the brick hurls against us, whizzing from right to left—and in the uneven panels, which defy chronology. In one of my favorite strips, Krazy reads Krazy Kat. Naturally, he is astounded. He says, “But ignatz dahlink!! Here I am here, and here you is here too.” Ignatz, ever superior, replies, in a nonchalant pose: “Of course.” The panel is delineated and thickly framed, emphasizing Ignatz’s comfort within the cartoon world; by contrast, in the next frame Krazy jumps up and down on the paper (“but, if I are here, and you is here, how come I are in the paper, and you als—ansa me that”). Ignatz’s pose is then rotated so that he lies on his side, in exactly the same construction of lines, and replies, “Because, fol, how could it be aught were it not thus—you answer that.” Here, like Krazy, we are perplexed. We cannot answer. Ignatz raises an eyebrow.

Krazy Kat by George Herriman.

Cummings also sought to control time by manipulating space in his poems. For this reason, he disliked technology, particularly the Linotype, which he saw as intruding on his freedom. In one plaintive letter to his aunt Jane, he writes about the urgent need to “retranslate 71 poems out of typewriter language into linotype-ese,” which “inflicts a pre-established whole—the type ‘line’ on every smallest part; so that words, letters, punctuation marks & (most important of all) spaces between these various elements.” The Linotype’s enforcement of the linear destroyed the potential space within the typewritten poems for chance collisions and a hidden choreography of readerly eye movements. In 1920, after reading a book asserting that the eye remains in constant motion, Cummings scrawled excitedly: “THE EYE MUST NEVER STOP.”

Ironically, the digitization of Herriman’s strips has improved the experience of reading them. We read differently on screens; we’re used to tabs, pop-ups, watching movies, toggling around. As I discovered during lockdown, having hijacked the huge monitor my boyfriend’s company sent him, these digital versions of Herriman’s strips preserve their strange logic; technology doesn’t interfere with the artist’s control of time but lets us read vertically and horizontally at once. Gazing at them on the screen made me realize why Cummings felt such a kinship with Herriman, whom he called a “poet-painter,” a title he otherwise reserved for himself. Try looking at one of Cummings’s poems, the ones not meant to be read aloud—one imitating striptease, or a drunk still drinking, or the twirl of a snowflake, or even a grasshopper on the page—and then looking at the screen. See how it hops.

Amber Medland’s debut novel Wild Pets was published by Faber last year.

July 18, 2022

On Paris Blues

Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman in Paris Blues (1961). Courtesy of Metrograph.

“For me as a kid,” writes Darryl Pinckney in a memoir in the Review’s Summer issue, “the film had everything I couldn’t have: cigarettes and train stations, late nights and drinking. Sex.” The film in question is Paris Blues (1961), directed by Martin Ritt and starring Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman. In honor of Pinckney’s essay, the Review and Metrograph cohosted a screening of the film on the evening of Sunday, July 10—the first in an ongoing series of cohosted evenings. Before a sold-out theater, Pinckney greeted the enthusiastic audience with a talk that spanned the glory of Sidney Poitier, the changing role of race in postwar cinema, and dreams of integration and artistic integrity. Today, we are publishing his remarks in full.

The black character entered mainstream postwar cinema as a social problem. This is the milieu of Sidney Poitier’s debut, in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s No Way Out in 1950. He is a doctor, and the black community beats off the white mob come for revenge on Poitier’s character after a bigot’s brother dies in his care. Two decades went by before a network television station was willing to air the film in prime time. In Richard Brooks’s Blackboard Jungle (1955), Poitier is thirty-one years old but completely convincing as a bright, ambivalent black student at a high school troubled by violent ethnic rivalries and nihilistic juvenile crime. In The Devil Finds Work (1976), James Baldwin recalls that Harlem audiences bayed at the Sidney Poitier character at the end of Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958). A black convict is suddenly free of the white convict he’s been chained to for more than an hour on-screen, but he falls off the train he hopped on to escape, because he extended his hand too far to the white convict, who had been giving him such an awful, racist time. Poitier found a film world opposed to the Hays Code, segregation, and McCarthyism by temperament as well as from principle. He fit right in. He worked with the best people right off. These films were made with studio commitment, if not entirely wanted by them. The black director Lloyd Richards made a Broadway hit of Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, but he was passed over when it came to the making of the film, which featured the original cast, including Sidney Poitier. The film came out in 1961, a few months ahead of Paris Blues.

As the sixties went on, Poitier’s characters saved white women: a blind girl in A Patch of Blue (1965); a suicidal woman in The Slender Thread (1965); a rich girl who doesn’t need saving in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967); and the peace of mind of the widow of a murdered factory owner in In the Heat of the Night (1967). No wonder Poitier went in for comedies in the seventies, light detective fare, his version of the blaxploitation film that provided professional relief from social-problem dramas, not to mention a chance to project images of black characters formed by pressures not having to do with a white executive’s ability to accept them. But we identify Poitier with those daring social dramas. He embodied the moral superiority of—what to call it—blackness, black spirit, black people when in conflict with the dupes of their own white racism. His intelligence and good looks and poise and strength left race theorists on their own ground. Like Paul Robeson, Poitier didn’t have to be accounted for. He was box office magic.

Both Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman had worked with the director Martin Ritt before. Poitier had starred in Ritt’s gritty labor drama Edge of the City (1957), with John Cassavetes as a white worker in need whom Poitier’s character befriends on the docks. (Ruby Dee plays his wife in this film, as she would in A Raisin in the Sun.) Paul Newman is the drifter who marries up in the world in Ritt’s The Long, Hot Summer (1958). (Joanne Woodward plays the rich girl he shapes up for.) It’s supposed to be Faulkner, but it’s impossible not to think of Tennessee Williams. All that steaminess. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, directed by Richard Brooks, came out the same year as The Long, Hot Summer. In the wishing-well world of Tennessee Williams, Paul Newman is on crutches—any excuse not to be eaten alive by Elizabeth Taylor.

Ritt’s Paris Blues recasts the social drama of race, turning it into a portrayal of the sacrifices of art, the cost of charting your own destiny. Ram Bowen, played by Paul Newman, is a trombonist, and Eddie Cook, the Sidney Poitier role, is a saxophonist and a member of Ram’s band, which has a regular job at a Paris club. Connie (Diahann Carroll), a black schoolteacher, and her white best friend, Lillian (Joanne Woodward), a mother of two, arrive in Paris for an inexpensive two-week winter holiday. Though Ram initially hits on Connie, she and Eddie will fall in love, as will Ram and Lillian. The tension of the film is in whether the men will give up on their lives in Paris and go home with the women. In his study Blacks in Films (1975), Jim Pines argues that Ritt uses racial understatement as a form of alternate characterization. The racial theme is secondary to his purpose; his focus is on the struggle of the characters to maintain their individuality and integrity.

The music talks for them, is interior consciousness, an alternative narration itself. Critics at the time admired the underscore of the film that Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn composed. (Strayhorn was not credited, even though his composition “Take the ‘A’ Train” opens the film, as David Hajdu points out in his 1996 biography, Lush Life). The sound track also mixes in Ellington favorites. Johnny Hodges makes a guest appearance in the last measures of “Paris Blues.” The Ellington-Strayhorn score laughs that swing isn’t over. Here comes Louis Armstrong, a sort of father figure of the music. The film was released as cool jazz arrived, but its music is already encouraging nostalgia. Paris, city of self-discovery, heartache, and American regret.

By comparison, love’s streets are mean in the New York of John Cassavetes’s Shadows (1959), in which a white Beat guy shows himself not hip enough to have a girlfriend who turns out to be black. Josephine Baker is called upon to renounce either the white man or Paris itself in her early films; Kenneth Macpherson made Borderline (1930) in Switzerland—with Paul Robeson and H.D. It is a story in which the injured party, the white wife, pays with her life for her husband’s interracial love affair. But Paris Blues is neither a film about passing nor one about interracial romance. At the time of its release, Paris Blues appeared to have few antecedents in film history. However, the novel on which the film is based, Harold Flender’s Paris Blues (1957), is in a literary tradition, that of the American in Paris: Henry James, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Henry Miller.

Flender’s novel concentrates on Eddie, on the seediness of his hot music scene, his several loves, and his bitterness toward America. Norman Mailer’s essay “The White Negro” announced a cultural fascination with the black man as a born star of the existential crisis of man. Flender, a white writer, was already on message. The film, on the other hand, is concerned mostly with Ram Bowen, the white trombonist, which is maybe one of those examples of what can happen when a subject such as black alienation goes mainstream. Flender’s dark realism on the page blossomed into a beautifully photographed romance of light and shade. What the film keeps of the novel’s central story is Connie’s challenge to Eddie to return to the United States and face whatever is coming in the struggle for social change. The novel is set in the brooding fifties; in the film we see Kennedy’s name in a newspaper headline. The world is new.

Clifford Thompson, in an essay on Paris Blues in his collection Love for Sale: And Other Essays (2013), notes that the romance of the black couple and that of the white couple are handled very differently. Eddie and his girlfriend, Connie, walk all over the tourist town, arm in arm, while Ram and Lillian wake up in his bed her first morning in Paris. To make Connie intelligently virtuous gets around the fears there may have been at the time that audiences, black as well as white, might be offended by showing black people being sexual on the screen. The film is also innocent about drugs, having a sort of Reefer Madness ignorance about cocaine addiction, in the case of Ram’s guitarist, whom Ram tries to save. The film cleans up the milieu we think of when we think of jazz. Only wine and cigarettes, cigarettes. Bohemia in Ritt’s film is not escapist; it is opportunity.

The essays of Richard Wright and James Baldwin from the late fifties and early sixties have little to say about the treatment of Algerians in Paris, because the French government was clear that any outspokenness on the subject would put a black American writer’s visa at risk. What seems to have made an impression on black audiences in 1961 was how freely the black characters in Paris Blues move around the city, how accepting of their presence the French are shown to be. And the film came out in a year of violent upheaval in francophone Africa, in the Congo and Algeria. When Connie exhorts Eddie that trouble for her family—i.e., black people—is the same as trouble for her, the summer of the Freedom Riders is about to come. Change is powerful, as giddy-making as the love Eddie and Connie declare for each other. Because he is going back committed to the crusade of racial justice, he’s not like the white American characters in postwar film and literature who go home because they’ve been defeated by the sophistication of Europe or stand in psychological need of the stability offered by the conventional life they thought they wanted to get away from.

Expatriatism was understood in black America as an individual solution to a mass problem, which was what it had in common with passing. To cross the color line was a decision about the cost of personal liberty. To cross the ocean was also an effort to remove the black self from U.S. color laws. A handful of black American artists and musicians studied in Paris in the nineteenth century, but the legends of the black American musician in Paris began in the aftermath of World War I. Why go home to get lynched? World War II answered the question. Then, another generation of black veterans delayed going back to racial discrimination in the United States by studying in Paris on the GI Bill. Jazz audiences in Europe were larger, more generous to black musicians than those in the States. Ralph Ellison said in the fifties that he got sick of hearing about the freedom of Parisian cafés. Black expatriates were aware that Paris was the capital of a colonial empire, but Paris was not segregated, the urban freedom was real. In Paris Blues, the pairs of lovers are not interracial, but bohemian Paris is integrated, the jazz tunes are anthems of revolutionary personal combinations. Moreover, the music Ram has lived, jazz, is black, just as his ambition to make what was considered serious music of it is Ellingtonian. His wish to succeed with black music as his roots is a kind of integration working the other way. Ram is not of the devil’s party; he is the anti-Chet, worthy, far from self-destructive myths about creativity. Throughout the film, the talk between the musician friends is about work, finding time to work.

Maybe that is why Paris Blues brings to mind those works that remember what an integrated scene the literary and music worlds were in the early sixties. Hettie Jones’s memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones (1990), recalls the mixed-race couples, the jazz magazines, the clubs, the poetry journals of a downtown New York scene in the fifties and early sixties. Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967) storms about this mixed-race cultural scene of the provisional, yet real. Cruse remembers the year 1961, when downtown political groups such as the Organization of Young Men were criticized for being interracial. White people were afraid to offend black people or figured they had no grounds on which to object. Much got thrown away culturally in order to discover what the Black Arts movement found. Where do you see race in this, Hettie Jones demanded when her husband walked out and became a black militant in Harlem. In Paris Blues the interracial is a part of the city’s glamour.

Darryl Pinckney’s memoir, Come Back in September, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the fall.

July 15, 2022

Balenciaga, Light Verse, and Dancing on Command

Look 7 in Demna Gvesalia’s 2022 Balenciaga haute couture show.

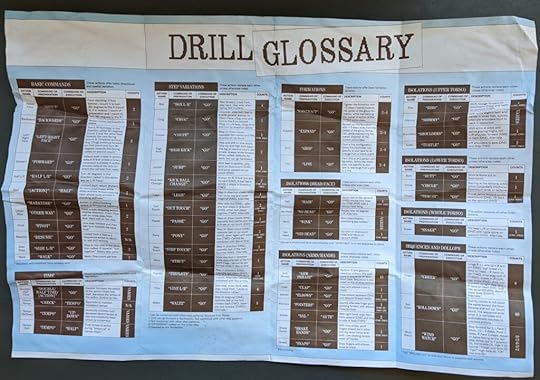

For someone who spends most of life reading and writing, dance is a miracle. Literature twists language to get at truth, but dance circumvents it altogether. Of course, this is only true at the moment of performance; the work of dance is full of language–often commands, usually unheard by the audience. Milka Djordjevich’s CORPS, which I saw at NY Live Arts a couple of weeks ago, invites us to consider the interplay of communication and labor in dance. It opens with a two-word command, “Snaps, go,” spoken by one of six dancers in drab gym uniforms as they march into view, fingers obediently snapping. When another says “no-head, go,” they begin to shake their heads, still snapping. This continues, with about forty moves in different combinations—from sources including military drill, ballet, and cheerleading—for the first half of the piece. (My personal favorite was “pointers,” a raffish shaking of double finger-guns that I plan to try at my cousin’s wedding). It’s a strangely anarchic, nonhierarchical performance of command-giving: any dancer can call the next move, and the official vocabulary is interspersed with chatty asides. Controlling their own collective fate, they still end up doing things that none of them seem to want—like jumping up and down for what feels like ten minutes, breathless, awaiting instruction. Anyone who has had a job, or a family, will recognize the inertia of the group project. In the second half, the drill team, now in gold-spangled, softly jingling, not-quite-matching costumes, begins a magnificent disintegration, each dancer interpreting the moves from the first sequence in their own ways, then getting weirder, ultimately collapsing into a pile on the floor. There they chat, all speaking at once, repeating everyday phrases until they morph into new ones (“in or out/in and out/In-N-Out/have you been to In-N-Out?/best burgers…”). This psychedelic segment is a bit more exciting than the flawed austerity that precedes it, but you can’t choose a favorite—each half relies on the other for meaning.

—Jane Breakell, development director

For his 1973 anthology The Oxford Book of Light Verse, W. H. Auden included poetry that took as its subject “the everyday social life of its period or the experiences of the poet as an ordinary human being.” The collection, which includes Byron and Pope, confirms that “lightness” doesn’t preclude “greatness.” I wonder: would Auden consider Tim Key’s Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush light verse? Certainly, it tackles contemporary social life from the perspective of an everyman—it takes place during COVID lockdown in London, featuring a poet-narrator who traipses around the capital while talking on his iPhone.

The book, subtitled “an anthology of poems and conversations,” is difficult to classify. It has theatrical and fantastical touches, and Key revels in an absurdity that verges on nonsense poetry—but this isn’t that. Maybe if you squint a bit—or a lot—you could call it vers de société. As with Key’s first lockdown anthology, I felt I was encountering a comic novel. It’s a preposterous volume, in which “the Poet” is contemptuous, rash, insecure, ridiculous, and farcically ordinary. His personality comes through so strongly in these pages that it’s easy to imagine him delivering each line, exasperated mumbles and all. Here’s a silly example, from “Leaning”:

The government banned leaning.

“What the -?!”

I could barely believe what I was reading on

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk

Light verse, indeed, from our Byronic hero! In some happy corner of my mind, Auden is alive, back in that dive on Fifty-Second Street. But this time, he’s not beleaguered by “negation and despair,” and there’s no war in Europe—neither his generation’s nor ours. This time, he’s just reading a bit of Tim Key and giggling.

—Robin Jones, business manager

My love of clothes has always appeared to me merely as a secondary surface effect of another medium—film, photography, music, history—and “style” as a persona—noir heroine, Spring Breaker—with which to accessorize my own personality. I never really liked Fashion, in the proper sense, until I watched Balenciaga’s 51st couture show, which was streamed to the public last week from Paris. The show, staged on snow white carpets in a recreation of Cristobal Balenciaga’s original couture salon, is a mesmerizing dramatization of the gesture of interpretation: Demna Gvasalia’s almost campily pure pageant of Fashion signifies nothing but itself, reducing clothes to abstractions of the medium’s elementary materials—shape, texture, movement.

There are inflated ballgowns and hyper-architected trench coats, but also T-shirts, the comparative structurelessness of which is illustrated via hyperbolic rumples in the fabric. All of the looks somehow amplify classical silhouettes, either by literally magnifying their proportions, or alienating the form from its fabric. The first half dozen are dresses, suits, and coats rendered in a black rubber that makes them look literally un-textured, like a 3D-model that has yet to be assigned a material. The next couple looks repeat many of the same silhouettes, only “colored in”—with sparkly tweeds, for example. This progression makes these fabrics more sparkly, more tweed-y, more Platonically themselves than they’d otherwise appear.

Much of the show’s dramatic arc is structured by this kind of evolution from ideal to particular. The first thirty-eight models wear shiny, insect-like masks. The various kinds of gimp-y black face coverings that Demna has made his signature have often read to me as embarrassingly “edgy” in their evocation of fetishwear—but in the context of his hyper-couture, the masks don’t “read” at all: instead, they successfully evacuate the clothes of content, allowing them to figure as impersonal animations of Fashion itself. The final models are unmasked, an inversion which elevates their faces into something like masks, casting the real people (many of them celebrities) as iconic versions of themselves.

Rather than digital, everything in the video looks virtual, which is to say perfectly idealized. Watching it on my laptop, I had the uncanny feeling of accessing a world more high-resolution—with cleaner lines, more fabric-like fabrics, more highly characterized characters—than my actual life: muddled, glitchy, pixelated by comparison.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

“Drill Glossary,” from a pamphlet designed by Ella Gold for Milka Djordjevich’s CORPS.

July 13, 2022

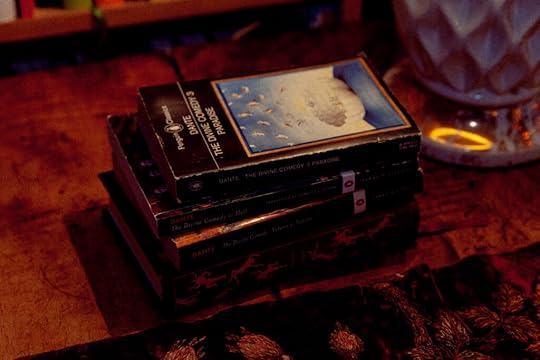

Cooking with Dante Alighieri

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

For the past fourteen months I have been on a path of conversion to Catholicism. In addition to going to mass, trying to memorize prayers, and worrying about my singing voice, I attend a staid biweekly discussion group moderated by a priest. We are slowly reading a book of contemporary Italian theology. My conversion was spurred by a specific—and specifically Catholic—experience of grace. I am confident about it, but less so about reconciling myself with the many dogmas of Catholic Church. I have struggled especially, as a previously secular person, with believing in sin. As a category, it has always seemed socially malignant, an excuse to burn witches. And in my personal life both gluttony and lust might be problems, especially because they don’t really seem like problems: sex and food are good things.

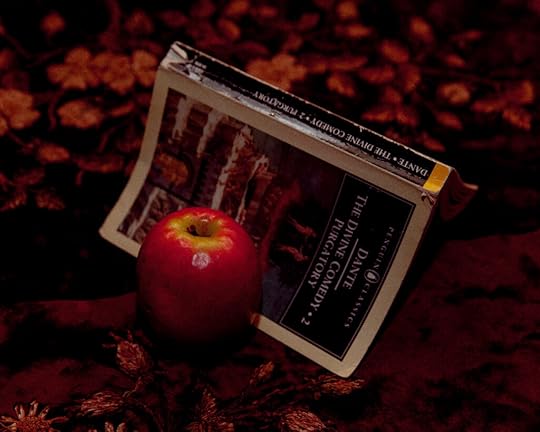

“The ideal way of reading The Divine Comedy would be to start at the first line and go straight through to the end, surrendering to the vigor of the story-telling,” writes translator Dorothy Sayers. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

And so I was overjoyed to find an articulation of sin that makes sense to me in The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), a three-volume work wherein a pilgrim travels through nine circles of hell and then seven cornices of purgatory, before reaching paradise. The version I’m reading was translated and annotated by English mystery writer Dorothy Sayers, who was also a theologian, and I found her work on natural and moral law, laid out in the book The Mind of the Maker, helpful as background to understanding Dante. Natural laws, Sayers wrote, are “statements of observed facts inherent in the nature of the universe”—along the lines of “if you hold your finger in the fire it will be burnt.” The religious viewpoint says there is also a “universal moral law,” which is itself a natural law, “which consists of certain statements of fact about the nature of man.” By behaving in conformity with moral law, “man enjoys his true freedom”—a state available in this life, which we might call happiness, or a kind of soul-deep fulfillment. Behavior that does not conform with the moral law “tends to enslave mankind and produce the catastrophes called ‘judgements of God,’” Sayers says. Sin, then, is behavior that does not conform with moral law; behavior which is spiritually and soulfully bad for us and will hurt ourselves and others. Injunctions on sin do not exist to deny us pleasures but to save us from harm.

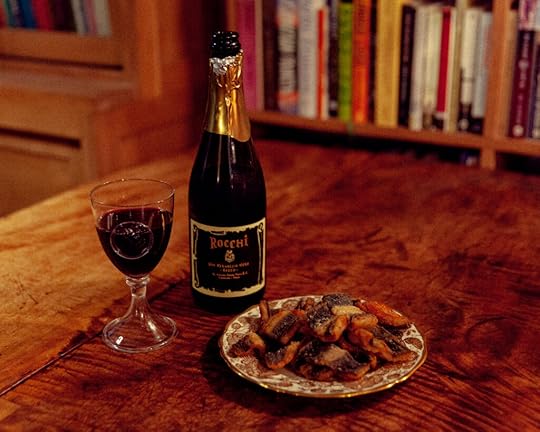

The pleasures that landed a French pope in purgatory: fried eels and sweet Vernaccia wine. Red Vernaccia Nera bubbles sourced for me by spirits consultant Hank Zona. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Viewed through this lens, The Divine Comedy becomes the page-tuner Sayers claims it is, offering “the drama of the soul’s choice” in this life. And while my general-secularist understanding of sin has been that it condemns activities that really aren’t bad at all, what I found in the lowest rings of The Inferno were behaviors that did seem like our human worst. In the last trench of circle eight, for example, alchemists are punished. These are “transmuters of metals,” as Sayers puts it, “every kind of deceiver who tampers with the basic commodities by which society lives.” Dante indicates that their behavior breaks “the general bond of love and nature’s tie” between people—almost the worst thing you can do. I imagine today’s alchemists as makers of poison baby formula or builders of shoddy public housing; circle eight, trench ten is just what they deserve. Just below them are three giants whom Sayers believes are “images of the blind forces which remain in the soul and in society” when the general bond of love is withdrawn. The giants are “blocks of primitive mass emotion” representing “nonsense,” “senseless rage,” and “brainless vanity.” Reading this, I thought about the contemporary internet and especially the impacts of social media—which seems to me located between rings eight and nine of hell.

An Italian preparation of eels asks for a marinade of garlic and bay leaves. For more authenticity, substitute a white Vernaccia wine for the vinegar in the recipe. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

In this moral universe, my own sins of lust and gluttony turn out to be the least bad sins, punished in the first two circles of hell and purged on the last two cornices of purgatory. Both my vices are what Sayers calls sins of “incontinence” produced by “self-indulgence, weakness of will and easy yielding to appetite.” Their mitigating factors, according to Dante: they are not related to desire to do harm; they often concern pleasure and mutuality. But there are ways in which these behaviors often just don’t work for us. Punishments throughout the Divine Comedy are “simply the sin itself, experienced without illusion,” Sayers writes. What unrepentant sinners did in life, they will do forever in hell, without the illusion that the sin was pleasurable.

In hell, for example, the lustful are swept along by a black wind. “The bright, voluptuous sin is now seen as it is—a howling darkness of helpless discomfort,” Sayers says. This helpless discomfort is of course not located in all forms of sexuality—but I know it can be found there. And gluttony, a sin which begins in mutual indulgence, leads, according to Sayers, by “imperceptible degradation to solitary self-indulgence.” I’d understand that to mean that it’s not the dinner and drinks with friends that are the problem but the binge-eating afterwards. And if we take the lessons of The Divine Comedy seriously, perhaps one leads to the other more than we realize. The gluttonous in Canto VI wallow in the mud, being torn by the claws of Cerberus, an experience Sayers calls “a cold sensuality, a sodden and filthy spiritual wretchedness.” This description dovetails with my experiences of binge-eating—enjoyment of food gone too far.

Instead of stuffing oneself with eel, Dante recommends: “Blessed are they whom so great grace illumes, /… that in their bosom’s core / The palate’s lust kindles no craving fumes.” Photograph by Erica LacLean.

Equally important, Dante’s gluttonous are responsible for “prey[ing] on people and things,” Sayers says, a concept that relates to our increasing awareness of food systems and food ethics. If your consumption preyed upon others in life, in hell you are turned into the prey of a three-headed dog. In purgatory, the punishment for gluttony is starvation—a fate which also seems illuminating when we think in the network of global consumption. I turned to this concept, with Purgatory as my guide, in order to cook from Dante. Dante describes the this fate in Cantos XXII-XXIV; the emaciated shades of the gluttonous are teased by a tree “green with laden boughs” whose “crop of tempting fruit ambrosial odours spread.” The tree tapers from bottom to top, so the shades cannot reach its fruit, and it is cascaded with spray at the top from a mountain stream, also out of reach of the thirsty sinners. Beneath the tree we meet people who ate and drank too much. One is a Frenchman named Simon de Brie, who died from a surfeit of “Bolsena eels and sweet Vernaccia wine.” Another is Ubaldin dalla Pila, “a liberal and cultivated man, with a great knack for inventing new culinary recipes,” as Sayers explains in a note. (As an inventor of recipes, I am concerned!) In contrast with these peoples’ behaviors, Dante celebrates a “primal age … beautiful as gold” when “Hunger made acorns savory to its need” and “Streams for its thirst like rills of nectar rolled.”

“Gluttony tends to be, on the whole, a warm-hearted and companionable sin,” Sayers wrote. I served the scones made from these acorns to as many friends as possible. Photography by Erica MacLean.

I decided to make a combination of gluttonous and virtuous foods: I’d serve “bad” Italian-style fried eel with Vernaccia wine, but would also make “good” scones with tree fruit and acorns. And a third dish would be a mixture of bad and good: an apple, taken straight from the tree of the knowledge (and my favorite fruit, incidentally), sweetened virtuously with honey. Dante remarks that “locusts and honey were enough to feed / The Baptist in the desert.” The usage of acorns seemed especially appropriate to counteract gluttony, since I have tried to make acorn flour before and discovered that processing acorns is so time-consuming, finicky and laborious that the results must be energy-negative. Acorns are also the kind of foraged and wild-crafted food recommended for a more sustainable lifestyle (though humans should harvest them only in years when they are bountiful in order not to negatively impact squirrel populations).

I had acorns in my freezer from a previous adventure cooking from the work of Mary Shelley and began working on them about a month in advance; there was no easy gluttony in this task. Acorns are bitter and very tannic, and their interior meat is encased in a tightly fitting husk that might be poisonous (sources conflict). I tried various methods recommended online to remove the husk, including boiling the acorns, which didn’t work, and shaving it off with a knife, which did, but was incredibly slow. Since I was doing penance for my sins, I dutifully shaved acorns in my free time for about a week before discovering, mostly by accident, that the husk falls right off previously frozen acorns cracked and left out on the counter to dry for a few days. Leaving the acorns exposed to the air makes the outer flesh oxidize and turn black, but it didn’t seem to affect the color of the final flour. In fact, my final flour was lighter in color than that of the commercial kind I’ve bought before.

My flour, during the cold-leaching process. The finished product was worth the time. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Once the acorns were peeled, I had to leach out their tannins, a process that can take between three days and two weeks depending on the type of acorn. I ground my acorns with water in the blender, making a mixture that looked like a coffee milkshake, and then placed it in a large jar in the refrigerator. Once the mixture settled, I began pouring off the water and refreshing it twice a day. Internet sources instructed me to preserve the white layer on top of the flour, allegedly the fat and starch, by straining the mixture through cheesecloth with every refresh. I tried, but my cloth was too porous and my fat and starch layer was lost—perhaps better from the standpoint of gluttony. At first, the mixture was overpoweringly oaky and bitter and smelled strongly of vanilla; but as promised, after two weeks of assiduous leaching, it became bland and pleasant with an oaty, milky scent. At that point I drained it and spread it out on a cutting board, fluffing and stirring it with my fingers every day or two until it dried. This might take a few days in a warm climate, but for me it took a week. I then ground it again (by the three-quarters cup in a coffee grinder—also a slow task) and set out to bake the world’s most hard-earned scone, using a recipe I’d previously had success with using commercial acorn flour, and substituting dried figs, a classic Italian ingredient, for the foraged dried apples I’d previously used.

A recommendation to preserve the flour’s fat and starch by draining the water off through cheesecloth was not effective. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

My three dishes were some of the ugliest food I’ve ever made—which made me happy morally, if not creatively. To see ugly truths behind illusions is, I think, the first steps toward the kind of spiritual self-improvement I’m seeking. I thought the unaesthetic results might also reveal my sins from a new angle. I propagate photos of pretty foodstuffs on the internet—which I have located between circles eight and nine, don’t forget—a practice that encourages appetite in others and supports a lazy subconscious assumption that our food is all pretty and good. Yet we know the stories behind it are often ugly.

In terms of taste, my dishes fell neatly into the categories of bad, mixed, and good, almost as if Dante had placed them there. I have never had much success cooking eel. When cooked well, it is tender and melting, but mine always turns out tough. Neither the texture nor the oily, fishy flavor would tempt anyone to overconsume. The baked apple was fine, a reliable dish of moderate sweetness. I ate it but thought it really could have used some ice cream. (Would this have been a sin?) And the homemade acorn flour scones were incredible, and even grew on me as I polished them off over several days. The flour had a sweet, nutty, faintly oaky flavor, and a unique brawny toothsomeness. Its relative lack of fat and starch made the scones crisp-dry on the outside and perfectly pillowy in the center. I’ve since made a second version without figs and with pecans, which was even better, and the recipe below reflects the changes. The virtue of restraint, in this case, really was its own reward.

The fruit tree which taunts the gluttonous in purgatory with unreachable branches is “a scion of the self-same stock … which fed that greed of Eve’s,” Dante wrote. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The wine for my meal was a Vernaccia, a type which appears frequently in medieval and early Renaissance Italian literature. My spirits consultant Hank Zona explained that in that time period, it was a lightly macerated sweet wine that could have been made from any number of grapes. Today the term refers to wine made from a specific Vernaccia grape, of which there are several. Hank chose a bubbly red Vernaccia Nera from Italian producer Paris Rocchi, a second-generation vineyard run by a brother-sister team. He said that bubbles and fried food go well together, and that the eel’s meaty flesh would pair with the earthy, dark-berry notes in the wine. The wine went a long way towards improving the dish, and unlike the other sinful food, was delicious.

I enjoyed drinking the wine and pulling together the meal, odd as it may have been. Despite the complexities, I hope such enjoyment is not a sin—but I suppose, someday, I’ll find out.

Fried Eel

½ pound eel fillets

2 cloves garlic, smashed

3 bay leaves, crumbled

Salt

Pepper

Olive oil

1 tablespoon champagne vinegar

⅓ cup flour, for dredging

Light flavorless oil for frying

Lemon wedges to serve

Chop the eel fillets in three-inch pieces. Set them in a flat-bottomed dish, topped with garlic and bay leaves. Season with salt and pepper, drizzle with olive oil and vinegar, and set aside to marinade for at least an hour or ideally overnight. When you’re ready to cook, place the flour in a shallow dish, season with salt and pepper, and dredge the eel pieces. Heat the oil in a large skillet to approximately 350 degrees and fry the eel until browned and crispy, being careful not to crowd the pan. Set on paper towels to drain and serve with lemon wedges.

Acorn Scones

For the acorn flour:

1 gallon freezer bag filled with acorns.

For the scones:

1 cup white flour

¾ cup acorn flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

¼ cup sugar

¾ teaspoon salt

8 tablespoons cold unsalted butter, diced

⅓ cup pecans, chopped

3 tablespoons buttermilk

1 egg

To make the acorn flour:

Pre-freeze your acorns for at least a day. Remove from the freezer, crack the shells, and spread them out on a countertop to dry for two or more days, waiting until the inner husk of the acorn falls off easily. The acorn flesh will turn black, but don’t worry about it. When you can easily remove the husks, do so, then process the acorns in your blender in batches, using about a 1:2 ratio of acorns to water. Put the resulting mixture in a large jar with a lid, refrigerate, and wait for the flour to settle to the bottom. When it has, you can pour off the top of the liquid, add more water, shake and repeat. Refresh the water in this way twice daily until the tannins have leached out and the flour is bland and pleasant to taste, anywhere from three days to two weeks. If you are not sure if the flour is bland enough, give it more time. When ready, drain and spread out in a warm place to dry on a large baking sheet, anywhere from one day to one week. At this point you’ll have a chunky, polenta-like meal. Grind again in a coffee grinder until fine. One gallon freezer bag of acorns produces about three cups of flour.

To make the scones:

Preheat the oven to 375. Mix together the acorn flour, white flour, baking powder, sugar, and salt in a medium mixing bowl. Add the cold butter and cut in with a pastry blender until the mixture is mostly combined and any remaining chunks of butter are smaller than pea-size. Add the pecans and stir. Make a well in the center and add the egg and the buttermilk. Whip with a fork to combine, and then start pulling in the flour mixture, stirring until the entire mass is moistened. Use your hands to crunch the dough together until it is homogenous and forms a single ball. Place the dough on a baking sheet, flatten slightly with a rolling pin, and cut it into six wedges. Pull the wedges apart a little so they don’t stick together when they cook. Bake for sixteen minutes, until puffy and cooked through.

A Single Baked Apple

1 apple

2 teaspoons honey

1 teaspoon chopped pecans

Preheat the oven to 350. Cut the cap off the apple and remove the core. Fill with the honey and pecans, place in your smallest baking dish, cover the dish with foil, and bake for thirty to forty-five minutes, until the apple is soft.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

July 12, 2022

Bona Nit, Estimat (An Ordinary Night)

Illustration by Na Kim.

I can’t fall asleep till my skin—sweaty, sticky, sizzling with bacteria, random fungal itches, swellings, vague histamine eruptions—has been unified by a bath or shower. I wear a white cotton T-shirt softened by age to tame this commotion and to guard my insanely sensitive nipples against the onslaught of, say, the blanket’s edge.

Mr. X. and I read for a while. I’m reading Derek McCormack’s wondrous Castle Faggot, but after a few paragraphs the words stop making sense. I whisper, “Bona nit, estimat.” Xavi whispers, “Bona nit, malparits,” and we kiss. Why do we whisper? Sometimes we whisper “I love you.” I roll onto my right side, and incredibly Xavi slides closer and drapes an arm over me. Ceding bed territory sets off a small alarm. “Sweet dreams, honey,” he might add, amused to be using the English endearment. Thirty seconds later he snores softly in my ear and a toenail digs into my calf. I am on the edge, he gathers the quilt in such a way that I am half-exposed and if I want more space or more covers there will be a struggle. I find this adorable. Everything explains why we should be together in this bed.

I often think about the dead before sleep—saying goodnight to them? Not think about—more like have the feeling of them. Are they my default setting? Is default consciousness what happens before sleep? My mother and I disliked talking on the phone so we spent most of our weekly calls saying goodbye, but now I mentally pick up the phone to say hello, a gesture. I think of Kathy Acker with a pang of love, a welter of unfinished business. When Xavi holds me, he contains these feelings. Tonight it’s simple—I wish Kathy were alive to be held like this.

I move Xavi’s hand from my waist to my hip, free the scrotum skin caught between my legs, and crack my right foot. When I yawn, sleep is near. But I rise onto my elbow to write these notes, or other notes, in my black notebook, by the cell phone light. Xavi sleeps—my efforts don’t disturb him. It has taken most of my life to learn to withdraw into myself, to sleep with a lover’s arm around me. It’s a level of trust, I suppose. The ability to trust.

Going to sleep is so general. Am I most like others or most like myself? I kick the covers off, I run hot, that’s okay. Xavi pulls the covers to him. I photo-documented this at four in the morning one night, every scrap of blanket gathered around him like a cocoon. J’accuse! He goes to sleep so quickly and stays asleep, I suppose. What a wonderful mammal! Sleep is complicated for me. I fall asleep, but staying asleep is a question, because melatonin levels decline with age.

I wake after four or five hours. My heavy body hurts more in the middle of the night than in the morning—why? The taut feeling in my side—liver disease? Pancreatic cancer? Gallstones? Why do my feet buzz? Why does the horizontal hurt my knee? Bruce Boone and I decided we dislike the terms old and older to describe ourselves. We prefer entropic, thus observing a majestic cosmic law. My disintegration enthralls me. I am the pain in my back, stiff, achy. I hope I’m finished when I die, like Great-Aunt Olga. How clumsy I was on the ladder and on our pitched roof when Xavi and I collected the leaves from the massive California pepper next door. Like a toddler. At some point, climbing a ladder onto my roof will be a bad idea. Goodbye, roof! Goodbye, view! I mentally avert my eyes.

Olga had an elegant death. She was ninety-five, I believe. She phoned my mother. “Dorothy, I’m calling to say goodbye. I finished what I was put on earth to do and I am not having fun anymore.” She got in bed and turned her face to the wall. A few days later she slipped into a coma, a few more and she was gone. To Olga’s credit, she used the word fun. Fun fun fun till her daddy takes the T-bird away.

***

My night is divided by a subtle chronology, first sleep and second sleep. I sit for a moment, groggy, then stand for a moment to assess the situation—back, knees, hands. Entropic bodies move tentatively, trying to avoid a shock. It’s not that every movement hurts, but which movement and how much? My bladder sends a message of necessity. I step into the cold air of the kitchen, it’s 4:22. A swallow of water sweetens my mouth. Pure water from the High Sierras, though now augmented by San Francisco groundwater—worried thought. I take half a trazodone with a second sip. I shuffle to the toilet for a long pee, eyes closed. I aim by sound, a gentle treble. Sometimes it’s a short piss even though the urgency is the same. Do I wake up and sense my bladder, or does it wake me?

During “human history,” people in most of the world experienced periods of biphasic sleep. After a few hours of slumber, we prayed, read, worked, whittled, stared at the stars, fucked, visited one another, busied ourselves in myriad ways. In some accounts, we used the time to meditate on our dreams. Percy Bysshe Shelley: “I arise from dreams of thee / In the first sweet sleep of night.”

I do what I am advised not to do. The bright screen displays what’s new in the world and in my life. It’s like returning home wanting to feel that something happened, something is different. I check email and read the NYT and go other “places.” Sitting at the dining-room table, I try to maintain my posture. If I sink into my body like Humpty Dumpty my back freezes and movement is painful. I twist in the chair, loosening my torso. Stony-eyed, I hunt for images: an auction of modernist carpets, a site where men purvey their nakedness, mid-century decorative art, ceramic objects by Gertrud Vasegaard, Gutte Eriksen, and Edward Eberle. Caucasian rugs. Iznik tiles. According to Temple Grandin, predators feel elated when they hunt—or shop? I turn on the heater and there’s that hiss and smell of burning dust. I might tinker with a few sentences, like this one. Hissing, clicking.

I go back to bed: left side, right side? I like a cool room. The heat comes from our bodies. I rest on the edge of hot and cold, feel both at once. I lie in the dark, eyes closed yet watching for sleep, though of course I don’t see it. It’s not like entering a dark room or a dark box—I am already there. It’s more like an encounter along the way. Xavi moves closer in his sleep. That is a beautiful instinct, is it not? Sometimes he puts his hand on my butt. I can’t believe my luck. Another dead friend arrives, Kathleen Fraser.

Kathleen Fraser at B. Patisserie, San Francisco. May 11, 2018. Photograph by Robert Glück.

At the amazing B. Patisserie, where I liked to take her, she once played with my hat, mugging, and I took her picture with my cell phone to show her how well it suited her. She considered my life with Xavi and pronounced, “Good! I’m glad you have this experience!” Kathleen was like that—she took stock and put it into words. Decades earlier, about a different relationship, she’d warned, “Bob, he’s a cloud. You push, he’ll disappear.” I suppose she was glad that I’d found the kind of love she shared with her husband, Art. Love that is—what?—fulfilled. This was our last meeting out in the world. Our next visits took place at her bedside. This photo is a reminder of our lunch and of Kathleen’s bright eyes.

I wake a few hours later with this dream: I seem to have options—I choose to turn into a grouty cement wall. My gray cratered face looks like Méliès’s man in the moon as I dissolve into thick mortar on the top row of cinder blocks. I’m round as Humpty Dumpty—is this comedy? Instead of turning my face to the wall, I’m turning my face into a wall. Am I the wall Humpty falls from? The wall Olga turns to?

Robert Glück is the author of nine books of poetry and prose, including the novel Margery Kempe and the long poem I, Boombox, forthcoming from Roof Books in spring 2023. Read “About Ed” in our Summer issue.

July 11, 2022

Diary, 2011

To my retroactive disappointment, the journals I keep—I fill about one marble composition book a year—are an undifferentiated, undated jumble of fiction drafts, semifictionalized self-reflections, actual diary entries, to-do lists, lesson plans, notes for articles I’m writing, and strange doodles often in the form of heavily inked trapezoidal grids. I wish that the notebooks more frequently included scenes like this, in which I simply recorded, without much commentary or elaboration, what I remembered right after a conversation with my younger sister sometime in 2011, when she would have been thirteen and I twenty-five. Too often when I write personally I simply record states of mind, which have been frustratingly static and melodramatic over the years and often seem to be stylized in a way that I find unconvincing, even to myself. This page presents a clearer picture of what life was like at the time—quizzing my sister about her religious beliefs, asking her about TV shows and who Bruno Mars was. I was encouraging her to be open-minded about religion, even as a devout nonbeliever myself, probably out of some quasiparental instinct. She described an idiosyncratic cosmography: no to God, yes to guardian angels. Apparently she wanted to be a doctor at the time. (She ended up going to art school, a family tradition.) I was living in New York, home for the weekend, visiting my parents in New Jersey. The next decade took me to Montana, Virginia, and Boston before I circled back to Brooklyn just in time for the pandemic. I saw my sister in Philadelphia recently. She was driving the car, and we talked about what was on her mind now. Gay bars, the Supreme Court. I did not ask about angels.

Andrew Martin is the author of the novel Early Work and the story collection Cool for America.

July 7, 2022

More Summer Issue Poets Recommend

Aerial view of Agios Nikolaos Beach in Hydra, Greece. Photograph by dronepicr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

This week, we bring you reviews from two of our issue no. 240 contributors. If you enjoy these, why not read recommendations from four more of our Summer issue poets?

I was watching the sunset on the Greek island of Hydra with my best friend when I suddenly said, “I think I hate Henry Miller.” I’d just raced through The Colossus of Maroussi and then Tropic of Cancer. So, as my friend and I perched on rough stones by the sea, I forced her to listen to my least favorite passages from Tropic of Cancer. Miller brags about his penis—“a bone in my prick six inches long”! He catalogs what seems like “every cunt I grab hold of.” At a bar, he ejaculates on a stranger’s dress. (She’s “sore as hell.”) In 1934, when Tropic was published, this ecstatic obscenity could have been appealing; in 2022, reading it reminds me of being trapped in the bathroom queue at a party next to a coked-up man with a PhD and a browser tab permanently open to PornHub. The book feels, in Miller’s words, like “a thick tide of semen flooding the gutters.”

“I think I hate Henry Miller.” I think. Why did I qualify? Well, there is Tropic’s bravura opening. And despite the ethnographic gaze that saturates The Colossus of Maroussi, certain episodes of hilarity delighted me: the saga of Miller’s diarrhea during his visit to Crete, for example, in which he shits his pants, then shits at “the bottom of a moat near a dead horse swarming with bottle flies” and embarks on an oft-frustrated quest for “soggy rice with a little lemon juice in it” to quiet his bowels, all while touring ruins and being plied with victuals that are decidedly disquieting to his bowels. There are also passages of arresting beauty, where the writing has the feeling not of mania but of deep dreaming. Miller’s first approach to the island of Poros can only be quoted in full; it is perfect.

Does the moment redeem the mass of it? Can I recommend The Colossus of Maroussi for the sake of one gemlike isle? The question engenders other questions: what, if anything, redeems a work of literature? Is the language of redemption even appropriate? What about the language of possession? Yours, mine. Give, take. In college, listening to people debate that problematic, shifting thing called “the canon,” I privately thought that the books included in it are far weirder than either its defenders or detractors usually admit. I’ve rarely felt that what I read “excludes” me: no matter who wrote it or when, it is mine for the taking, or leaving. I cling to that feeling even now—even when I read “while it’s all very nice to know that a woman has a mind, literature coming from the cold corpse of a whore is the last thing to be served in bed.”

—Elisa Gonzalez, author of “ In Cyprus ”

After teaching The Epic of Gilgamesh for more than thirty years, I have only grown increasingly enamored with the myth’s iconic narratives, which depict the age-old, all too human desire for immortality. The adventures of Gilgamesh—a real Sumerian king who ruled between 2900–2350 BC—are many, and take place in both the upper and lower worlds. Around 1600–1155 BC, they were carved into clay tablets by a scribe. Herbert Mason’s translation of the myth, which captures the pathos of Gilgamesh’s heroic journey so memorably, inspired “Tablet,” my poem that appears in the summer issue of The Paris Review. I was particularly moved by the following commentary on mourning that’s delivered by the chorus in the aftermath of Gilgamesh’s dear friend Enkidu’s death:

For being human holds the special grief

Of privacy within the universe

That yearns and waits to be retouched

By someone who can take away

The memory of death.

It is Gilgamesh’s grief which allows him to transform from a misogynistic demigod/king into a fully human character who finds a way to accept his own mortality. During this time of worldwide grief following the pandemic, Gilgamesh is a beautiful reminder of the universality of that most tragic foundation of our humanity. In my apocryphal poem, I imagine Gilgamesh learning how to live, through his “special grief of privacy,” in the present: as a wise comedian, lying contentedly at last in his hammock “dreaming and waking, waking and dreaming.”

—Chard deNiord, author of “ Tablet ”

Diary, 2001

“Today I’m REALLY worried about death. I almost started crying. However, my new calligraphy kit is AWSOME.”

“My dollys are so fun to play with. They bend and move and pose. : )

P.S. the police think that Peterson might be guilty because there was blood all over the scene of the crime and a used condom (EW!) and a bloody soda can with hair on it.”

*