The Paris Review's Blog, page 76

August 5, 2022

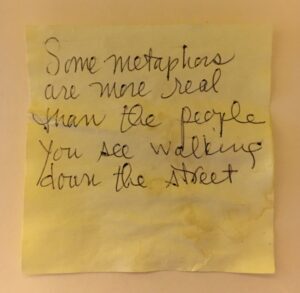

Mary Gaitskill’s Veronica and the Choreography of Chicken Soup

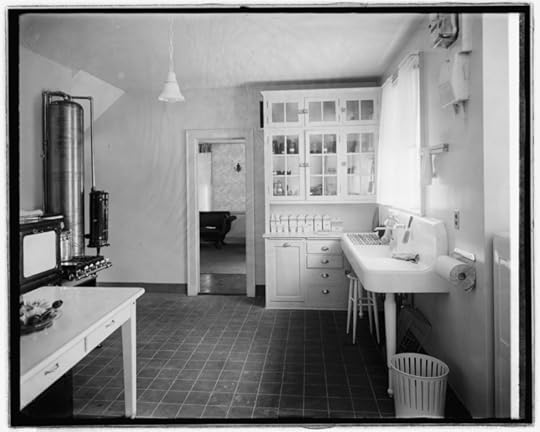

National Photo Company Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The seventies and eighties were a high point in American dance, and consequently, dance on television. As video technologies advanced, one-off performances inaccessible to most could be seamlessly captured and broadcast to the masses. Like all art forms, dance at this time was also influenced aesthetically by this new medium, as cinematic techniques permeated the choreographic (and vice versa). Today, many of these dance films are archived on YouTube. My favorite is a recording of avant-garde choreographer Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup, a one-woman monologue in dance that aired in 1988 on a TV program called Alive from Off Center. The piece is set to a minimalist score Cummings composed with Brian Eno and Meredith Monk. Over the music, a soft feminine voice narrates: “Coming through the open-window kitchen, all summer they drank iced coffee. With milk in it.” Cummings repeats a series of gestures: sipping coffee, threading a needle, and rocking a child. She glances with an exaggerated tilt of the head at an imaginary companion and mouths small talk—what Glenn Phillips of the Getty Museum calls her signature “facial choreography.” Her movements are sharp and distinct, creating the illusion that she is under a strobe light, or caught on slowly projected 35 mm film. She sways back and forth like a metronome, keeping time with her gestures.

This particular performance placed Cummings in a detailed set evocative of a fifties household. But when she performed Chicken Soup onstage, accompanied solely by piano music, there was no set at all aside from a wooden chair. In this recording, for example, of a 1989 live performance at Jacob’s Pillow, her movements themselves seem endowed with greater importance, and the barrier between storyteller and audience feels gauze thin. Chicken Soup is an invitation inside, into a conversation that is both private and familiar. “They sat in their flower-print housedresses at the white enameled kitchen table,” the voiceover continues, “endlessly talking about childhood friends. Operations. And abortions.” The work premiered in 1973, the year the Supreme Court ruled on Roe vs. Wade, but Cummings’s kitchen could be any woman’s—anytime, anywhere.

—Elinor Hitt, reader

I was recently gifted a copy of Mary Gaitskill’s 2005 novel Veronica by a friend, with a warning: You might like this a bit too much. Indeed, I was immediately engrossed by Gaitskill’s narrator—the wistful, appearance-obsessed Alison—and her own habit of liking things a bit too much. The Alison of the novel’s bleak present, a feeble woman plagued by hepatitis, a codeine addiction, and a stiff arm, is preoccupied by her glamorous past, constantly revisiting the series of events that took her from Californian teenage runaway to Parisian fashion model, and ultimately ejected her into the glum world in which she finds herself several decades later. Now, every interaction in her daily life—from riding the bus to cleaning offices as a temp—hurtles Alison into a well of memories, reminding her of the porcelain-faced model she once was. In interviews, Gaitskill has described the book’s structure as “almost like a palimpsest, rather than flashbacks—it was one time bleeding through another. Sometimes I changed the time frame by decades in one paragraph or even in one sentence.” There’s a violence in the way the past mercilessly seeps into Alison’s life, soaks it, weighs her down. But she doesn’t see it that way: “I feel like the bright past is coming through the gray present,” she says hopefully, “and I want to look at it one more time.”

Alison’s vanity prevails even as her physical body decays, providing opportunities for shrewd, annihilating appraisals of the strangers she meets, descriptions which linger for a beat longer than you’d expect. “He’s got the face of someone who’s been beat too many times,” Alison notes of her neighbor Freddie. “He’s also got the face of somebody who, after the beating is done, gets up, says ‘Okay,’ and keeps trying to find something good to eat or drink or roll in.” Nearly every sentence of the book is profoundly energetic, with each darting line pushing up against the next in surprising ways: “I loved them like you love your hand or your liver,” she says of her parents, “without thinking about it or even being able to see it.”

—Camille Jacobson, business manager

Blondell Cummings in Chicken Soup (1988, Alive from Off Center).

If Kim Novak Were to Die: A Conversation with Patrizia Cavalli

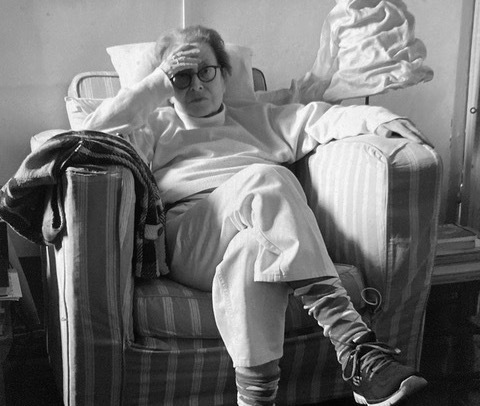

Patrizia Cavalli. Photograph by Mario Martone.

I first met Patrizia Cavalli in 2018, in her apartment near Campo de’ Fiori, where we drank tea with honey and talked from early afternoon until sunset. Every surface was covered with books, papers, notebooks, scissors, and scarves, and each bore the same handwritten note, a warning to visitors: “Do not move! If you move anything, I’ll kill you.” Over the course of two years, we had three more conversations, speaking for five hours at a stretch. The apartment had been her home for decades: in the late sixties, as a twenty-year-old philosophy student, she rented a single room there; she had just left Todi, the town in Umbria where she grew up, and in Rome she felt unmoored and lonely. In 1969, through a mutual friend, she met the writer Elsa Morante, who was then working on her novel History. Morante was the first person to look at Cavalli’s poems, and after reading them, she called to say, “Patrizia, I’m happy to tell you that you are a poet.”

More than fifty years later, Cavalli’s poems are translated and loved across Europe and the United States. Her first collection, My Poems Won’t Change the World (1974), signaled the forthrightness and disregard for authority that would characterize all her work. Cavalli examines the causes and conditions of pleasure and pain, and the moments in life, often imperceptible at the time, that herald change. Her work explores infatuation, boredom, deception, conflict, grief—all in a poetic voice whose nonchalance belies its artistry.

When Cavalli died in June, it felt as though all of Rome wanted to pay tribute. A beautiful ceremony took place at the Campidoglio, where flowers were piled upon flowers. Her admirers and friends crowded the stairwell, and the room where her body lay in state. Cavalli might have criticized the extravagant floral arrangements, but she would have been moved by the words her loved ones chose to speak—some of them her own.

INTERVIEWER

How did you start writing poems?

PATRIZIA CAVALLI

My first poems were written for Kim Novak, in the fifth grade, after I saw the film Picnic. At one point, Novak is coming down the stairs, blond and beautiful, clapping her hands in time to the music that’s playing, and William Holden is watching her, fascinated, and he leaves the other woman to dance with her. I fell in love, went home, fasted for a week in protest because I’d never be able to know Kim Novak—and after the fast I wrote two poems. I found them recently while going through some old notebooks. One is titled “If Kim Novak were to die.” “Where are those black clothes of mine?” I wrote. “Where is the grief that shows on the outside? It’s not there? Well, doesn’t matter. I’ll have precocious grief in this deep heart of mine.”

This is what I’ve always done in my poems—they begin from something physical. I am sustained by eros when I write. Now, with this illness—this cancer that was diagnosed in 2015—it’s as if I’ve lost the memory of certain passionate feelings. But I haven’t lost my ear. I can hear when a word isn’t the exact word. Poetry is about being precise. The word must surprise you even in its necessity, as if you were hearing it for the first time. You should never slide into habits of speech, because there’s nothing more beautiful, more startling, than language. “Thinking about you / might let me forget you, my love.” This couplet, it glides into the air—do you hear it? Poetry knows how to glide into the air.

INTERVIEWER

So you’ve been writing since the fifties. Were you difficult as a child? Your book of essays, Con passi giapponesi (With Japanese steps), is a portrait of your mother and her sadness.

CAVALLI

My mother was in a state of despair, but for her own reasons. She’d chase me around the house with the rug beater; she’d wait behind a door to surprise me with a beating. But I’ve always done whatever I wanted—I’ve never asked anyone for permission. I wanted to get sick, to contract pneumonia or something else serious, so that my mother would feel it was her fault. I tried everything—I’d go into a freezing cave when I was hot, or stand out in the rain to drench myself. But my health withstood every assault, so I could never avenge myself against her that way.

As an adolescent, I’d go and get drunk in the countryside, and we’d have to be taken home all passed out, me and my girlfriends—I was always corrupting them. We’d drink gin because I’d read that Billie Holiday drank gin. I was living a dissolute life, truly dissolute. I’d ask truck drivers for rides, or challenge them to a game of morra. And I’d always win. I’d win chocolates or sweets, and then they’d drive me back home in their trucks.

INTERVIEWER

Did you never feel that you were in danger?

CAVALLI

Nothing ever happened to me. The truck drivers behaved perfectly, they were kind—in those days, at least. None of them tried to lay so much as a hand on me. They must have been stunned to see a fifteen-year-old girl asking for a ride to the service station at two in the morning. It was like a dare. Maybe I was just so strange that I brought out some timidity in them.

Those who did try something with me were all people of a different sort—lawyers, my piano teacher, family friends. It was fun sometimes, I liked the perversion of the unfamiliar. It was a kind of power, and I enjoyed exercising that power. I lived in Ancona for two years because of my father’s job, and there—it was incredible—every man tried to touch me. It’s not that I was shocked, but I did think less of them. I was never the victim. I was too full of myself to stand for being the victim.

INTERVIEWER

And you never fell in love with a man back then?

CAVALLI

You could see it from a mile away, my predilection for women. Except for one time, when I got a bit of a crush on my neighbor, a beautiful boy—we’d become friends in a way that was almost erotic. But no, I never fell in love. Mine was also a moral decision. I couldn’t stand being the one who had to submit. I couldn’t stand being told, Well, but he’s the man—in the sense that he was freer than me, stronger than me. I would go crazy. I could never have stayed one step behind, been less important than a man. I’ve made love with so many women who’ve been disappointed by their men. And I used every experience of falling in love, every one of my body’s sensations, to write my poems. I don’t have a soul, I have only feelings and words.

INTERVIEWER

Have you always written in the same way?

CAVALLI

Of course not. For a while, until I left Todi in the sixties, I thought that writing poetry meant changing words a little. I invented words, truncated them and made them mysterious, and I wrote things that meant nothing, absolutely nothing. I was unhappy, even in my writing—I was fake. But I never stopped writing.

Then one day I announced that I was going to Rome, and I went, to a rented room near Termini Station. I didn’t know anyone, didn’t have a watch, couldn’t get my bearings. I’d stand on the sidewalk with one hand in my pocket and I wouldn’t ask anyone for directions because I didn’t want to seem like a tourist. Every month I’d spend all the money I had right away because I was always taking taxis, so then I’d have to go back to Todi. All I had was this group of gay American friends, who were elegant and sophisticated. I’d go out with them at night. I was the only woman, and I spoke very little English. I’d ask, So, where are the lesbians? They found me funny. Really, I was depressed and alone.

INTERVIEWER

You once said, “Elsa Morante pulled me out of my unhappiness and made me a poet.”

CAVALLI

In 1969, Elsa Morante had just published The World Saved by Kids. Pier Paolo Pasolini called it “a political manifesto written with the grace of a fable, with humor, with joy.” Once I’d read that book, I was certain that I was like her—but I was just a conformist, still stuck in 1968, while she was already past that, and impatient with my platitudes. In Rome, I finally met her, thanks to a friend of mine who introduced us. But I was too proud, and I arrived late, just as she was leaving. Still, she said, Telephone me if you want. I was a snob then—I pretended I was cool when I wasn’t, pretended I had money though I didn’t—but I did telephone her. I can say with certainty that that’s where everything began for me. I met all my dearest friends thanks to her—critics, editors, historians, actors, artists, set designers. A whole bunch of us would go out to lunch in a pub, some humble, unpretentious spot—this was when she was writing History, so her head was deep in that world—and she was the queen of those lunches. Almost always she’d pay for everyone. Then we’d go have a gelato somewhere. We spoke properly, were careful not to use words that annoyed her. We’d be together from twelve thirty on the dot until four or four thirty, when we’d walk her to her front door, and she’d sit down to write until late into the night.

She was thirty-five years older, but she always treated me as an equal. I took care at first not to mention that I wrote poems—I knew how difficult she could be, how quick to scorn and exclude. For her, poetry was the ultimate, the most important art form. I knew that what I’d written up to that point would have horrified her. I imagined she would say, Aren’t you embarrassed? But one day she stopped short in front of me and said, So you, what do you do? I don’t know how it came to me, this wicked, impulsive idea to say, I write poems. She gave me a sadistic look and said, Oh yes? Well, let me read them—not because I’m interested from a literary standpoint, I just want to see what you’re made of.

It was hell. After that, I went into hiding. I shut myself in at home to rewrite—that is, to write—my poems. It was a kind of spiritual exercise, and the wonderful thing—no, the miraculous thing—is that from this quasi-fraud emerged the truth of my lines. After six months, I brought to the restaurant a little folder of thirty poems, all short. Then I went home. Half an hour later, the phone rang and it was her. I don’t think I’ve ever again in my life been so glad. I had been accepted—no one could kick me out. Now I was a poet. Everything that happened after that seemed natural. Writing, publishing, the reviews—nothing mattered more than the recognition from Elsa Morante. She was the one who chose the title of my collection, My Poems Won’t Change the World.

We argued a lot over the years of our friendship. Actually, we argued right up until the end of her life. By the end, it had become very painful. And then I abandoned her. I can’t say I have any regrets—being with her had become impossible. But that was the crucial meeting of my life.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve published six collections of poetry, but you’ve also translated Shakespeare, Molière, Oscar Wilde. What does the work of translation mean to you?

CAVALLI

I’ve translated The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Othello, and Twelfth Night. I sought to understand the voices Shakespeare wanted to give his characters. I listened to them, imagined them. I tried always to produce living translations, ready for the stage. It’s like verbal gymnastics. You can’t just ferry the words from one language to another, and you can never search for synonyms, which don’t exist, because every word is unique—every word wants to mean exactly that. You even have to imagine the faces of the actors and their voices, an audience applauding, the box office revenue you’ll rake in. That’s the only way for the work to be open and fruitful, the only way for me to speak directly to Shakespeare, to Molière, the only way not to wrong them.

INTERVIEWER

You often personify what you write about. One of the brilliant, labyrinthine essays in Con passi giapponesi is titled “Headache.” Like Joan Didion, who also wrote beautifully on the subject, you treat this painful invader of the head as a companion.

CAVALLI

My headache was almost always preceded by euphoria, and then it would crash into me brutally. When I got the aura, I’d collapse into a visionary state. First comes that uncontrollable happiness—you feel the universe, the continents, the seasons, infancy. I’d start singing in the street. It was irresistible. I wasn’t even embarrassed. I’d start singing operas that didn’t exist … then I’d get emotional, and I’d cry. Maybe it was a kind of lunacy, a primal passion. And then, all of a sudden, boom! As if I’d been struck in the head, that ecstatic experience would become pain, pain, pain. It was a confluence that made me levitate, until it passed and I felt at peace. Then it felt as if there were two of me, because it seemed impossible to have borne such intense pain.

But now he won’t come back, and I miss him. I get bored. The headache was an extraordinary thing—like love, when it lands and shatters everything—and as I said, when it comes to writing, I’m always moved by some ecstatic form of adoration, or contempt, or hate. By something corporeal that possesses me—desire, or a headache. It seems to me, now that I have neither, that I’ve grown duller, dazed, that I don’t feel anything anymore.

INTERVIEWER

You have described this moment as a kind of poetic crisis.

CAVALLI

Writing poems is strange, like being dragged toward something that, before, didn’t exist, that you hadn’t conceived of. Inspiration, for me, was a mode of transport toward a vision that was dictated to me. Now, well, no one’s dictating. I don’t feel the wave. Once in a while you can conceive of some poems mentally, but it’s no good. Especially if you have no memory. There must be an immediate memory, while you’re writing. Writing is a memory, a word-for-word memory. The cancer has caused so many changes in mood and such physical weakness. There are moments when I forget my own feelings. I can only repeat the old ones, like something I know, more or less.

I’ve always written to be loved, but now what? I haven’t been writing beautiful poems. I wake myself up at night, I think of something, and transcribe it. Then I go back to reread what I’ve written, and I think, Are you stupid? Right now, I feel far from poetry. And if I reread my shortest poems, well, I tell myself, often they’re bullshit. So as a result, all I do is self-cannibalize. I take these millions of manuscripts I have and recopy them in nice handwriting. Since they’re also fairly old and I’ve forgotten about them, this gives me a kind of pleasure—discovering that I wrote that thing.

INTERVIEWER

You are also famous for your fantastic dinners, which delight and terrorize your friends.

CAVALLI

Yes, I love—and in this love, too, there is eros—making dinner for my friends. Even now, when I tire so easily. Setting the table with the most beautiful tablecloth, marvelous glasses, flowers arranged just so. My friends are terrified because they know that if they bring wine, the wine has to be only the best. The flowers have to smell good, and not everyone knows how to choose flowers. And not all the guests will be wearing a nice scent—for me, smell is the most developed of my senses, the one that is the source of the most pain. I buy cheese in only one place, marrons glacés in another, breadsticks in another. My dinners are a work of seduction. There was a time when everything came very easily, even soufflés. You know how hard it is to prepare the perfect tomato sauce, to make the perfect spaghetti in tomato sauce? But what I like most is a messy table, after dinner, with the remnants of the meal, the half-empty glasses, the stains on the tablecloth, the crumbs, the pitchers of water, the chairs out of place. I’ll take pictures of the scene.

I need this continuous mise-en-scène. I used to love climbing onto the table to tap dance. I need to perform, to be on the stage, to let my comic side come out, to use my whole body. The voice, the words, the body. The truth is, I wish I had a kind of entourage with me at all times, someone to compliment me, someone else to compliment me again, someone to touch me lovingly. And I’d read a poem, sing a song, fall in love, have fun, let myself be coddled. This is the life that I like and that gives me that bit of happiness I need to write poems.

INTERVIEWER

Although you said that to write poems is to be dragged toward something that previously didn’t exist. A kind of miracle, something beyond the body.

CAVALLI

It’s like that, and it’s also like being dragged toward precision. There are many ways to write poems. The shortest ones are like shards that have broken off from a larger whole. Poetry is the collision of intention and chance. Something needs to fit into something else, but without overwhelming it, in such a way that it seems that everything has to be like this—that the first time you open your mouth, this is the breath that comes out. If you can manage to stay just at the point when the words resonate, where they arrange themselves into a whole that is obvious, necessary, and surprising—then what’s happened is a manmade miracle.

But when I open some book of poetry and my eyes slide along as if over a mirror, and they don’t stop on any word, they keep moving because the words are insignificant and hinder every emotion and you don’t know why they’re there, then I feel as if I’m sliding into a black pool, and I have to close the book right away. And I can never remember who wrote those lines.

INTERVIEWER

When do you write? How do you write?

CAVALLI

I write wherever, at whatever hour, with a pen. Usually, I write on sheets of paper. My house is full of papers, my drawers are overflowing. I’d need a secretary to organize everything.

INTERVIEWER

Geoffrey Brock has written that you “revitalize the traditional techniques.” What’s your technique?

CAVALLI

I wouldn’t say that I have a technique. I’m open to anything so long as the poem sounds a certain way, so long as it resembles an unexpected reality. The sound of a word, which is not an empty sound, produces a wave that has its own duration. I have no preconceptions, nor do I have any preformed forms. I don’t try to make a sonnet. The rhymes have to be almost inadvertent, casual. The most important principle is to leave the words their liberty, as if they were animals on a soft, flexible leash.

INTERVIEWER

Who are your poetic models?

CAVALLI

Contemporary poets, unfortunately, don’t come to mind. What can I do if there’s no one I admire? Maybe it’s a form of rivalry or envy. When you read the real poets, the words come at you, they open themselves up rather than close themselves down. This happens to me with Dante, with Cavalcanti, with Leopardi, with Emily Dickinson, with Sandro Penna. I learn them by heart, they keep me company. I’m walking down the street, or around my house, and at a certain point they come to my rescue. With them, it’s never just the beginning of a poem, it’s more like the beginning of a concerto. I set the poems of Emily Dickinson to music, and when I read them the music comes to me along with the sound of the words. My nature is theatrical, and my poems are inseparable from my voice and from my way of saying them. I don’t recite poems, I say them. Or I sing them.

INTERVIEWER

What is your definition of poetry?

CAVALLI

I studied Greek as well as Latin meter—I have it in my ear. It’s a natural, musical rhythm that has guided me, always. I wouldn’t be able to start writing a poem if I didn’t immediately hear something that sounds—call it a regular rhythm, or stress, the eruption of a line that already has its own form.

But many of the short poems I’ve written are like stories in verse. Rarely could you say of me that I’m a lyric poet. There are some poems that are like songs, but those are few. In my poems, there’s always some visible, solid matter. This is lightened and rendered more delicate by the language, by the rhymes, by the assonances, by how the lines move, how long they are, all things that are natural, and that are also born before the thought—that the thought is chasing after. The idea reveals itself, it inheres in the words that brought it along. It never precedes them.

INTERVIEWER

There is also the familiar furniture of your poetics—the chairs, the pillows, the lamps, the kitchen tiles, the basket of dirty laundry, the brush.

CAVALLI

I love objects, it’s true. In fact, if I think about my death, I almost—almost—feel sadder about the objects than about the people. My eyes will never again rest on that armchair with that fabric. I’ll miss the beauty of vases, of books, of photo albums, of little wooden chairs. I love to listen to music on my record players. I love to look at my piano even when I’m not playing it. No one can move my things, no one can borrow my books.

But against the serenity, against the lightness of these domestic objects, there’s always this contrast, the unpredictability of the body and the environment—it’s a double movement. Right now, this one bathroom at the top of the stairs torments me. It made me fall one night. There’s a feeling inside objects, but above all they contain the memory of feelings—these paper lampshades, these notebooks with their white pages, on which I may never again write.

Translated from the Italian by Miranda Popkey. Introduction translated by Oriana Ullman.

Annalena Benini is an Italian journalist, columnist, and author. She has been writing about books and culture for the daily newspaper Il Foglio since 2001, and currently edits its monthly magazine. In 2021, she received the Premio Viareggio Repaci for journalism.

Read Patrizia Cavalli’s poetry in the archive.

August 3, 2022

Diary, 2001

June 5, 2001

When I wrote this, I was living full-time in an idyllic southwest German university town where I had been a familiar figure since the eighties, spending money saved up from fifteen years of menial work elsewhere while sharing a small apartment with two other women. My last job had involved documenting C++, so people were leaning on me to learn to code.

My diaries are rife with shorthand made up of proper names. People stand in for their lifestyles, values, and even for chance remarks. For example, the Christe doctrine refers to a principle casually formulated by the heavy metal critic Ian Christe circa 1994. He felt that people should move where they want to live and look for work there, instead of the other way around, because people always give the really plum jobs to their friends. At the time he was making a living beta-testing video games.

The words in this entry are also abbreviations. Settle means to abjure free love and live with a partner again, likely tripling my household income. Computers means a full-time tech job. Tü, of course, is Universitätsstadt Tübingen, the notoriously livable earthly paradise where I was working my way through a friend’s list of sexual recommendations. Having slept with basically every man she knew, she had informed opinions as to which ones I’d enjoy. During the day, I wrote letters and blog entries (e.g. https://shats.com/AR/Previous/NellNov...). I was having a good time. Did I really want to “settle?”

The diary entry reflects a significant turning point in my thinking. I liked sexual freedom, but I also liked the idea of owning a drafty Gothic revival mansion on brick pilings in a field. The epicycles (twirling motion of the planets in Ptolemaic astronomy) showed me that my desires were mutually exclusive, so I dropped one (the house, obviously) and never looked back.

Nell Zink has published six novels, including the recent Avalon.

August 1, 2022

The Discovery of the World

Clarice Lispector at work. Courtesy of Paulo Gurgel Valente.

In 1967, the Jornal do Brasil asked Clarice Lispector to write a Saturday newspaper column on any topic she wished. For nearly seven years, she wrote weekly, covering a wide range of topics—humans and animals, bad dinner parties, the daily activities of her two sons—but the subject matter was often besides the point. These genre-defying missives are defined by a lyricism and strangeness that readers of her fiction will recognize, though they are a thing apart in their brevity and interiority. Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas will be published in English by New Directions this September. As her son, Paulo Gurgel Valente, has written, “Enjoy the columns, I know of nothing quite like them.” Today, the Review is publishing a selection of these crônicas.

July 6, 1968

The Discovery of the World

What I want to tell you is as delicate as life itself. And I want to use the delicacy that exists inside me along with the peasant coarseness that is my saving grace.

As a child and, later, as an adolescent, I was precocious in many things. In sensing an atmosphere, for example, in picking up on someone else’s personal atmosphere. On the other hand, far from being precocious, I was incredibly backward as regards other important things. Indeed, I continue to be backward in many areas. And there’s nothing I can do about it: it seems there is a childish side of me that will never grow up.

For example, until I turned thirteen, I was very backward in learning what Americans call “the facts of life.” The expression, “facts of life,” refers to the profound love relationship between a man and a woman out of which children are born. Or did I understand, but deliberately muddied my potential for understanding so that I could, without feeling too shocked at myself, continue innocently to dress myself up for the benefit of boys? Dressing myself up when I was eleven consisted in washing my face until my taut skin gleamed. I would feel ready then. Was my ignorance a sly, unconscious way of keeping myself innocent so that I could guiltlessly continue to think about boys? I believe it was. Because I always knew about things that I didn’t even know I knew.

My school friends knew everything and even told stories about it. I didn’t understand, but I pretended to understand so that they would not despise me and my ignorance.

Meanwhile, unaware of what the reality was, I continued, purely instinctively, to flirt with the boys I liked, and to think about them. My instinct preceded my intelligence.

Until one day, when I had already turned thirteen, as if only then did I feel mature enough to receive some shocking real-life news, I told my secret to a close friend: that I was ignorant and had only pretended to be in the know. She found this hard to believe because I had pretended so well. However, finally convinced that I was telling the truth, she took it upon herself, right there on the street corner, to explain the mystery of life to me. Except that she was equally young and didn’t know how to talk about it in a way that would not wound the sensitive soul I was at the time. I stood staring at her, open-mouthed, paralyzed, filled with a mixture of bewilderment, horror, indignation and mortally wounded innocence. Mentally I was stammering: but why? what for? The shock was so great — and for a few months really traumatizing — that right there on that street corner I swore out loud that I would never marry.

Some months later, though, I forgot my oath and continued my little romances.

Later, when more time had passed, instead of feeling shocked by the way a man and a woman come together, I thought it perfect. And extremely delicate too. I had, by then, been transformed into a young woman, tall, thoughtful, rebellious, with a large dose of wildness and more than a pinch of shyness.

And yet before I became fully reconciled to the way life works, I suffered a lot, something I could have avoided had a responsible adult taken it upon themselves to explain about love. That adult would have known how to approach a childish soul without tormenting her with that unpleasant surprise, without obliging her, all alone, to come to terms with it in order, once again, to accept life and its mysteries.

Because what is truly surprising is that, even when I did know all the facts, the mystery remained intact. Even though I know that a plant produces flowers, I am still surprised by nature’s secret paths. And if, today, I still retain my modesty, it is not because I see anything shameful in the facts — it is merely female modesty.

And life, I swear, is beautiful.

March 14, 1970

Quietly Weeping

. . . I suddenly noticed him, and he was such an extraordinarily handsome, virile man that I felt a rush of joy as if I had created him. Not that I wanted him for myself just as I don’t want the Moon on those nights when she’s as light and cool as a pearl. Just as I don’t want the little nine-year-old boy with the hair of an archangel, who I saw running after a ball. All I wanted was to look. The man glanced at me for a moment and smiled quietly: he knew how handsome he was, and I know he knew that I didn’t want him for myself, he smiled because he didn’t feel in the least threatened. (Exceptional beings are more subject to dangers than ordinary people.) I crossed the road and hailed a cab. The breeze lifted the hairs on the back of my neck, and it was autumn, but it seemed to speak of a new spring as if the weary summer deserved the coolness of newly sprung flowers. And yet it was autumn and the leaves on the almond trees were turning yellow. I was so happy that I huddled fearfully in one corner of the taxi because happiness hurts too. And all because I had seen a handsome man. I still didn’t want him for myself, but he had, in a way, given me so much with that comradely smile of his, a smile between two people who understand each other. By then, approaching the viaduct near the Museum of Modern Art, I no longer felt happy, and the autumn seemed like a threat aimed directly at me. I felt like quietly weeping.

April 17, 1971

As Fast as I Can Type

Goodness gracious, how love keeps death at bay! I don’t know quite what I mean by that: I rely on my incomprehension, which has given me an instinctive and intuitive life, whereas so-called comprehension is so limited. I have lost friends. I don’t understand death, but I’m not afraid of dying. It will be a rest: a cradle at last. I won’t hurry it though; I will live until the last bitter drop. I don’t like it when people say I have an affinity with Virginia Woolf (I only read her after writing my first book): the reason is that I do not want to forgive her for committing suicide. Our horrible duty is to keep going to the end. And not to rely on anyone. Live your own reality. Discover the truth. And in order to suffer less, numb yourself slightly. Because I can no longer carry the sorrows of the world. What to do, though, since I feel totally what other peoples are and feel? I live in their lives, but I’ve run out of strength. I’m going to live a little in my life. I’m going to waterproof myself a little more. — There are some things I will never say: not in books, much less in a newspaper. And which I will never tell anyone in the world. A man told me that in the Talmud it says there are things that can be said to many people, others to few people, and others to no one. To which I would add: there are certain things I don’t even want to tell myself. I feel I know some truths. But I don’t know if I would understand them mentally. And I need to mature a little more if I am to draw closer to those truths. Which I can already sense. But truths don’t have words. Truths or truth? No, don’t even think that I’m going to talk about God: it’s a secret of mine.

It has turned out to be a beautiful autumn day. The beach was filled with a fine wind, a freedom. And I was alone. And at such moments I don’t need anyone. I need to learn not to need anyone. It’s difficult, because I need to share what I feel with someone. The sea was calm. I was too. But on the lookout, suspicious. As if this calm couldn’t last. Something is always about to happen. The unforeseen fascinates me.

There were two people with whom I had such a strong connection that I ceased to exist, while still continuing to be. How can I explain that? We would gaze into each other’s eyes and say nothing, and I was the other person and the other person was me. It’s so difficult to speak, so difficult to say things that cannot be said, so silent. How to translate the profound silence of the meeting of two souls? It’s very hard to explain: we were gazing straight at each other, and we remained like that for several moments.

We were one single being. Those moments are my secret. There was what is called perfect communion. I call this an “acute state of happiness.” I am terrifically lucid and I seem to be reaching a loftier plane of humanity. They were the loftiest moments I have ever had. Except that afterward . . . Afterward, I realized that, for those two people, such moments were meaningless; they were thinking about someone else. I had been alone, all alone. That was a pain too deep for words. I will pause briefly to answer the door to the man who has come to fix the record player. I don’t know what mood I will be in when I return to the typewriter. I haven’t listened to music for quite some time as I am trying to desensitize myself. One day, though, I was taken unawares while watching the movie Five Easy Pieces. There was music on the soundtrack, and I cried. There’s nothing shameful about crying. What’s shameful is me saying in public that I cried. But then they pay me to write. Therefore, I write.

Right, I’m back. The day is still just as beautiful. But life is very expensive (I say this because of how much the man wanted for the repair). I need to work a lot to have the things I want or need. I don’t think I ever want to write books again. I am only going to write for this newspaper. I would like a job for just a few hours a day, let’s say two or three hours, and that it (the job) would involve me interviewing people. I have a knack for this, even though I might appear a little absent at times. But when I’m with a genuine person, I, too, become genuine. If you think I’m going to copy out what I’m writing or correct this text, you are mistaken. It will go as it is. I will only read it through again to correct any typos.

As for a person I’m thinking of at this moment and who uses punctuation completely different from me, I say that punctuation is the breath of the sentence. I think I have already said this. I write at the same pace as I breathe. Am I being hermetic? Because it seems that in a newspaper you have to be terribly explicit. Am I explicit? I couldn’t care less.

Now I’m going to pause and light a cigarette. Perhaps I’ll go back to the typewriter or perhaps I’ll stop right here.

I’m back. I’m now thinking about turtles. When I wrote about animals, I said, out of pure intuition, that the turtle was a dinosaurian animal. Only later did I come to read that it actually is. How weird! One day I will write about turtles. They interest me a lot. As a matter of fact, all living beings, apart from man, are a riot of amazingness. It seems that, if we were made by someone, there must have been a lot of surplus energetic matter out of which the animals were made. What use, dear God, is a turtle? The title of what I am now writing should not be “As fast as I can type.” It should be more or less this, in the form of a question: “What about turtles?” And whoever reads me would say: “It’s true, I haven’t thought about turtles for a long time.” Now I really will stop. Goodbye. Until next Saturday.

Translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson. From Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas, which will be published by New Directions in September. Originally published as Todas as Crônicas in 2018. Courtesy of Paulo Gurgel Valente.

Clarice Lispector was born in 1920 to a Jewish family in western Ukraine. As a result of the anti-Semitic violence they endured, the family fled to Brazil in 1922, and Clarice Lispector grew up in Recife. Following the death of her mother when Clarice was nine, she moved to Rio de Janeiro. She is the author if nine novels, as well as a number of short stories, children’s books, and newspaper columns.

July 29, 2022

Ghosts, the Grateful Dead, and Earth Room

“The Ghost in the Stereoscope,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, licensed under CC0 1.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

When my wife was giving birth to our child, she saw—waiting at the door of the delivery room—her grandmother, my grandmother, and the grandmother of our sperm donor. In daily life all three of these women are dead. In the delivery room my wife’s grandmother was a reassuring presence, my grandmother—and here my wife is likely influenced by my own childhood reports—held herself at some distance, and our donor’s grandmother held a sign in the style of the airport pickup, welcoming our child. Never before had my wife felt the presence of the dead, but in the months of our baby’s babyhood they have been a recurring presence: a tiny man dressed in rags, muttering Latin by our baby’s bed; a man rocking in our nursing chair whom she first identified as my grandfather, then my father. I am scared of the dark and do not take the pleasure she takes in these appearances. But if there is satisfaction to be had from her morning announcements, it is the way they keep present, alongside the dead, David Ferry’s poem “Resemblance,” from his 2012 collection, Bewilderment. In the poem, the speaker describes seeing his dead father in a restaurant in Orange, New Jersey:

It was the eerie persistence of his not

Seeming to recognize that I was there,

Watching him from my table across the room;

It was also the sense of his being included

In the conversation around him, and yet not,

Though this in life had been familiar to me

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Where were we, in that restaurant that day?

Had I gone down into the world of the dead?

Were those other people really Shades of the Dead?

We expect that, if they came back, they would come back

To impart some knowledge of what it was they had learned

Except for the man muttering Latin, none of the dead speak to my wife. She knows what she needs to know from their presence, from the fact that they’ve come to be near our child. Where she feels clarity and reassurance, I feel, as I do about most things, bewildered. “Unable to know is a condition I’ve lived in / All my life,” Ferry writes in the poem. Earlier in the book he quotes a letter Goethe wrote a friend whose son had died: “It’s still, alas, the same old story: to live / Long is to outlive many; and after all, // We don’t even know, then, what it was all about.”

—Harriet Clark, author of “ Descent ”

On July 15 and 16, Dead & Company came to New York to play two shows at Citi Field. It was the end of the summer tour for the band, which includes a smattering of former members of The Grateful Dead—Bob Weir, Bill Kreutzmann, and Mickey Hart—alongside bassist Oteil Burbridge, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, and, most notably, John Mayer. This event is, for me, a kind of midsummer psychedelic Christmas, one also celebrated alongside approximately 40,000 other people. It dissolves, at long range, into undulations of tie-dye, dancing bear T-shirts, multicolored macramé, butterfly clips, neon bucket hats, infinity slinkies, skulls shot through with lightning. A varied cast of characters fill the makeshift parking-lot-village (nicknamed Shakedown Street) beside the field: there are aging Heads who were on the road in the seventies and eighties; shirtless twenty-somethings with waist-length hair huffing nitrous balloons in the lot; clean-shaven Manhattanites lucky to be off on summer Friday, one of them talking about a friend who’d recently been indicted for securities fraud. Then there are people who are just curious about the baffling and persistent phenomenon that is the music of The Grateful Dead.

And how to describe this phenomenon, exactly, and the experience of these shows? I might say, “And then they played ‘Franklin’s Tower’ and I cried,” but that means nothing if you haven’t, like me, gotten into the trunk of a car with your best friends, two of you facing backwards while you drive through the Berkshires, watching the reverse movie of the road late at night while Jerry sings: “Roll away… the dew…” I want to tell you something about these shows that’s not just a list of songs and a series of superlatives. “Best weekend of my life,” I told my oldest friend, the following Sunday. He said, “You’re always going to these shows and having the best weekend of your life,” which is true.

Someone once told me that if you do anything eleven times, you’ll come to love it. Maybe The Grateful Dead is just the particular thing I have chosen to do over and over and over again. Of course, the band itself was an engine of repetition, always remaking versions of the same thing, night in night out, over the course of decades. I see the unfathomably large trove of recorded live shows as fossilized evidence of the creative potential of recurrence. Dead & Company, which has existed for seven years now, as the result of Mayer and Weir’s surprising collaboration, is itself a remaking. It is miraculous that this band exists. Since the original band formed in 1965, the near-ends have been too many to enumerate: death after death after death, countless shows and tours that everyone said would be the last. There were rumors that this would be Dead & Company’s final tour, just as there were rumors that last summer’s would be.

But on Saturday night, there was a heavy sense of finality, when they circled back to their opener, “Playing in the Band,” for a moving, closing reprise that made us wonder, maybe, if they might really be done playing in the band. Kreutzmann is seventy-six and struggled with health issues throughout the tour; Weir is seventy-four; there are certain facts that one must face about the march of time. After the show, back in the parking lot, my friends and I were elated and also bereft, considering the possibility that all good things really do come to end, that the music might have to stop some time. But then again—it’s all a reprise. In the days since, we have all been rehashing, replaying, repeating the same old songs all over again.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

The cover of Rachel Mannheimer’s Earth Room features the choreographic score for Yvonne Rainer’s dance “Trio B: Running,” printed in neon lime green on equally fluorescent orange paper. Its interlocking lines and arrows are so thin and so blinding that they almost appear to be laser-cut into the paper, which takes on a peculiar charge in the absence of bright light. The sentences in Earth Room—a collection of linked verse and prose poems cataloging Mannheimer’s encounters with performance art, sculpture, and installation, published by Changes Press in April—form a similarly improbable architecture, built from description so clean and granular that it seems to burn its own vanishing shape into the block of text.

Mannheimer looks at work by artists including Rainer, Walter De Maria, Isamu Noguchi, and Pina Bausch with close attention to their theories of mutability—and to the changing reality of what the viewer can see, and feel. She’s particularly informed by the sculptor Robert Smithson’s theory of nonsites, which he developed while making small-scale geological works in the late sixties. In this series, Smithson transferred rocks and minerals from their natural “site” in the world—what he called “physical, raw reality”—to new formations in the museum or gallery—the “nonsite,” where he repackaged them in rigid metal structures. The text block is something of a nonsite in Earth Room, a location at which to reconfigure an art object at the smallest of scales—here, through minute description. The title of each poem deposits a trace of the object’s site in the world: Berlin, Beacon, Anchorage, Tempelhof, New York, the moon, or Mars. Mannheimer reminds us of that other definition of revision, in which to look at an object closely—to write about it—is to see all the versions of reality to which it is attached begin to come into focus. (For Mannheimer, this kind of looking involves other people—art critics and her loved ones both—and her lover’s face, in turn, is also an object of devoted study.)

Later in the collection, Mannheimer recalls the critic Michael Fried’s infamous essay “Objecthood and Art,” in which Fried disparages literalist art by Robert Morris, among others, for being “fundamentally theatrical,” somehow perverse for casting the viewer as an audience member. “But what Morris describes isn’t viewer as audience,” Mannheimer says. “Both viewer and object are dancers.” I read these poems in awe of their slowness, which, as a historically bad dancer, I thought I’d never be able to match. I tried to move with or against them as they revolved around each other like planets in orbit, first revealing one side, then another, some part of them always obscured in shadow. There’s a mathematical precision to Mannheimer’s work of gesture, even when it looks like improvisation: she calculates the exact distance from which you feel at once very far away from the thing you see and also, as she tells us, “very very very very / very very close.”

—Oriana Ullman, intern

July 28, 2022

The Face That Replicates

Collage of Norman Rockwell, “Girl at Mirror,” 1954. Licensed under CC0 4.0.

Sylvia refused to wear her glasses, which is why she saw me everywhere on campus. It seemed like it was every day that she’d come to our dorm’s living room and tell me about the not-Katy. “I yelled at her again,” she sighed, flopping onto the worn couch. “It wasn’t you.” It never was.

There wasn’t only one not-me. There were several other girls on our small liberal arts campus who had dirty-blond hair and shaggy bangs, girls who wore knee-high boots and short skirts, low-rise jeans and V-neck sweaters and too many tangled necklaces. In 2005, I didn’t stand out. I still don’t. My face, I suspect, is rather forgettable. I’m neither pretty enough to be remarkable nor strange enough to be interesting. This is true for the majority of people, though I have wondered if I have “one of those faces” that is particularly prone to inducing déjà vu. Some people seem like permanent doppelgängers. I became hypervigilant, on the lookout for not-mes that were also, sort of, me.

Looking back, I’m not surprised that I became obsessed with these look-alikes during this particular time period, in those heady and exciting early days of social media. Although the idea of doubling and mimesis dates back to the ancient Greeks and flourished in the popular imagination in gothic horror, my experience with doppelgängers still feels distinctly contemporary to me, an anxiety that arose with the camera in the nineteenth century and was then compounded by social media and its endless catalogues of faces. Although Facebook back then was limited to college students, it was still a place where one could get lost. You could lose hours searching, as I did, for people with your exact same name and friend requesting each and every one of them. You could meander through the uncanny haze of “doppelgänger week,” a destabilizing moment in the early 2000s when my classmates’ pimpled, imperfect, earnest faces were suddenly replaced by thumbnails of Angelina Jolie, Natalie Portman, and Halle Berry. It was more than just embarrassing. It was a massive Freudian slip, a sudden reveal of latent desires and delusions. We wanted to replace our faces with better, more beautiful ones—but not completely. We wanted to represent ourselves with images that weren’t us, exactly, but that were close.

***

One of my favorite doppelgänger stories is Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson,” which I read around the same time that my not-me began appearing in the edges of Sylvia’s blurry vision. This Poe tale is about a boy named William Wilson who meets another William Wilson and is dogged, throughout his life, by the disturbing presence of this other William Wilson. As the story progresses, we learn that this weird fellow is not actually our narrator’s evil twin, as we might have expected. He’s better than our narrator. He stops our narrator from doing a number of bad things before the original William succeeds in reasserting his uniqueness—by an act of murder, naturally.

William Wilson is not a funny story, exactly. But it’s full of little ironies that start to feel like jokes, from the name (William, son of Will, a pseudonym that’s also an echo) to the weird origins of the text itself. First of all, the story is a homage to a story that Washington Irving wrote called “An Unwritten Drama of Lord Byron.” Poe even wrote to Irving, sending him a copy of his tale, and asked him for a blurb to help sell the story. Later, in a review of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales, Poe wrote that one of them, “Howe’s Masquerade,” was very similar to “William Wilson,” so much so that “we observe something which resembles a plagiarism—but which may be a very flattering coincidence of thought.” A few years later, in 1846, Fyodor Dostoyevsky published his own similar novella, The Double: A Petersburg Poem, which he later rewrote and republished in 1866.

This type of doppelgänger story continued to multiply. Vladimir Nabokov called The Double a “perfect work of art” in his classroom lectures, though of course the story was ripe for rewritings—hence Nabokov’s own beleaguered and haunted narrators. The novels Despair and Lolita feature not quite doppelgängers but pairs of men behaving badly. In the twentieth century, we became adept at capturing, manipulating, and presenting precise visual copies of individuals through photography, film, and digital manipulation. Humans no longer had to use a hall of mirrors (or a skilled portrait artist) to see themselves doubled, tripled, quadrupled. We also became better at selective breeding and genetic manipulation. Dolly the sheep emerged from an adult cell in 1996, and attendant anxieties and sensational interest in the literal copies spiked Eventually, the concept of the double in art was superseded by the clone, as we slouched closer and closer to literal self-replication.

It makes sense, then, that in twentieth-century cinema and television the question was no longer “What if there was another?” but rather “What if there were many others? What if there were closets full of others, or storage facilities packed with others?” Slowly, the fear of the double stopped being about individual bodies and their capacity for violence and perversion. In the early double stories, characters were often forced to confront their failures, their fragility, their mortality. Clones could present this sort of threat, too, but they gestured toward even larger menaces. The Twilight Zone and The X-Files both featured story lines about clones, suffused with that same ambiguous mixture of desire and loathing that I’ve always felt toward my own mirror image. In these narratives, the clone could be a replacement for a lost loved one, or it could be an extra self employed to do our dirty work, but it was also always, by necessity, a reminder of powers vaster and greater than any one person could possess. Structures, institutions, governments, laboratories—these things all came together to make clones, just as movies and TV shows are products industry, vast teams of people working to represent visions of futuristic dystopia.

In the twenty-first century, bioethical questions about cloning took a back seat to the driving narrative force of physical replication. The idea that one could be replaced—or perhaps that one is a replacement—is closely tied to our obsession with authenticity, mimesis, and originality. People are supposedly unique. But what if we weren’t? What if we had already been divided and reproduced? What if it wasn’t the future we needed to fear but the present? In the 2009 movie Moon, astronaut Sam Bell is a clone of a clone of a clone, a chain of men with hangdog expressions. In the television show Orphan Black, there’s a group of clones who team up to take down the Big Bad. In Never Let Me Go—a 2010 adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel—we’re given a tale of body horror and cloning, longing and dread. Usually in these narratives, the enemy isn’t the cloned body or consciousness. It’s the biotech corporations that created the clones, the governments that want to control the clones, the police who are hunting the clones, the religious sects that want to murder the clones. In these science-fiction dystopias, we’re not supposed to be afraid of a couple of extra bodies. We’re supposed to fear instead their connection to something far more diffuse–the illuminati-like, omnipresent powers of surveillance and control. Jordan Peele’s 2019 film, Us, hits a similar note. He sets the viewer up to fear the doppelgängers, slowly building dread around their upsetting intrusion into one family’s rosy reality. Eventually, Peele pulls back the curtain and reveals the true source of horror. It’s not the twin-like bodies who fail to follow the rules of society that we need to fear; it’s the state. The horrible thing isn’t intruding upon us. It was already there, under our feet. It’s not invading our homes. It lives here, too.

***

There’s another type of doppelgänger. More ephemeral than the look-alike is the double self that is actually, in some fundamental and destabilizing way, really you. This second sort of doppelgänger is trickier to pin down and rather older, more mysterious, and often coded more feminine. Unlike the biological marvel of the clone or the intrusive physicality of the body double, this trope tends to be psychological or supernatural or both. This not-you might appear as a ghost, a mirage, or even an unwanted alter ego. In some stories, it’s a version of you that hides from your consciousness, doing things you wouldn’t normally do. (Though maybe you want to.) It’s your Tyler Durden, your Mr. Hyde. It’s not your replica; it’s maybe even more fully you than you are yourself.

By the time I went to college, I had already been acquainted with my depressive side for years. I’d gone on and off SSRIs, never finding quite the right fit. Like most depressives, I was a bit self-obsessed when I fell into my pits. I tended to mythologize the blue periods, turning them into phases of inescapable, indescribable, utterly unique suffering, though of course they were nothing of the sort. When I was well, I told romantic stories about my shadow self without even realizing how boring I was being, or how repetitive.

My vision of feminine suffering had been shaped, perhaps a little too heavily, by Romantic and gothic narratives. I’ve always loved stories about girls and their ghosts. These evergreen tales tend to follow certain patterns: the beautiful protagonist is going mad—or maybe she’s really haunted. She’s unfamiliar with her surroundings or entering into a new stage of life. She’s destabilized somehow. She’s a governess on a new job (Jane Eyre), a second wife brought to her new home (Rebecca), or even a ballerina playing her dream role (Black Swan was inspired by Dostoyevsky). Often, mirrors are central to the plot, or at least a device used to both reveal the characters’ vanity and their split nature. The reader or viewer can see that her demons are real, or at least partly so, but no one else can see the flames that lick the sides of her face. No one else can see the face that floats behind her own.

Sometimes these apparitions appear as omens. There are dozens of examples of ghostlike doubles appearing, and some of these are supposedly true stories. The American writer Robert Dale Owen made Émilie Sagée, a French schoolteacher, world famous when he published the supposedly substantiated account of her wraith. According to Owen, Sagée’s students saw her apparition frequently on campus. Once, she even appeared to be both in a classroom and on the lawn, within sight of over forty people. John Donne supposedly saw his pregnant wife’s doppelgänger appear to him, holding a baby in her arms, at the very moment when she was actually delivering her stillborn child. Percy Shelley saw his own wraith once, reported Mary Shelley, as did a few of their mutual friends. His second self approached him on a garden path and asked him how much longer he planned to be content. Not long, apparently.

What’s appealing about these ectoplasmic excesses and shadow-self lurkers is the same thing that’s terrifying: they could be real. You might really want to cook human fat into soap. You might really crave destruction. You might actually have unaddressed crimes, secret knowledge, and repressed memories hidden within you. There might be darkness in your mind, a place you can’t see. It’s an idea that underpins our entire understanding of psychology—that we have an unconscious mind, a second self beneath the surface.

***

It was only after I had a baby—a daughter—that I stopped looking for my doppelgänger. I was suddenly more absorbed in her face than in my own. Of course, this is when I finally stumbled across a doppegänger story that would really scare me. I picked up Helen Phillips’s novel The Need without knowing much at all about its plot. It was, I thought, a horror story about an intruder. This is correct, but the intruder that climbs out of the hallway trunk in the middle of the night isn’t a rapist or a murderer. It’s the narrator herself, visiting from another timeline. In this timeline, her children are dead. The doppelgänger wants what doppelgängers so often want: to take the place of the original. She wants to breastfeed her baby, take her children, share her responsibilities. To offer her body for consumption; to be consumed.

According to horror theorist Mark Fisher, the weird is a category defined by the presence of something that shouldn’t be there. The eerie is the absence of something that should be present. The Need is horrible because it’s both. There’s a longing and a lack. The intruder is, in a way, both types of doppelgänger: the external replacement and the shadow self. The other woman is an existential threat to the narrator, but she’s also a mother who wants to breastfeed and hold the baby. Reading this, I felt sick to my stomach. The idea that my baby could die is abhorrent in a way that feels contaminating—just thinking it is dangerous. None of the other double stories have affected me in this way. I’ve always found the idea of a second self a bit exciting, a frisson of possibility that borders on the sexual. While so many of these earlier stories end with a slash or a bang, Phillips ends hers with something far stickier. It’s not clear whether one mother supplants the other or if they somehow meld into one woman. The Jungian shadow self is integrated—or is she banished? The depressive lack is gone—or has it taken over completely? With “William Wilson” you know more or less what happens, even if it ends violently. Phillips gives us no such resolution.

This ambiguous ending conveys the instability of my own experience. Motherhood has been nothing if not destabilizing. It drew my focus inward during pregnancy, then outward during my daughter’s infancy. Suddenly, as she grows into a toddler and pulls away from me, I’m left alone again with my vague face and unfinished self. The truth is that I’ve been looking in the mirror far too much lately. I’ve been snapping selfies and setting my phone up so that I can record a video on the front-facing camera, since I’ve heard this is more accurate than a flipped screen. I’ve been trying to figure out what I actually look like, who I actually look like. When I scroll through photos on my phone or look at images I’ve posted on social media, I have trouble figuring out which of the many flat versions actually represents me. Even pictures I have taken in the past year look terribly strange, not at all like the person in the mirror with her tired eyes and long nose. My face has changed over the past few years. It’s partially because of pregnancy, but it’s also stress, a pandemic, and the result of Zoom distortion. My face no longer feels like my own.

The other day, I used a Russian search engine to reverse image search my face, revealing hundreds of women with shaggy blond hair and bangs, women with white faces and blunt chins. I was curious if I’d recognize any of them as being my exact match, my true doppelgänger. I found a few that made me pause, but no one was close enough. There was no thrill of discovery, no warm feelings of belonging. I had hoped for more, for some evidence that my face is out there, living and breathing, moving through some city I’ve never visited, kissing people I have never met, maybe even smoking a brand of cigarettes I’ve never smoked. I wanted there to be someone who, despite looking just like me, isn’t.

Katy Kelleher is a freelance writer whose book of essays, The Ugly History of Beautiful Things, is due out in 2023 from Simon & Schuster.

July 27, 2022

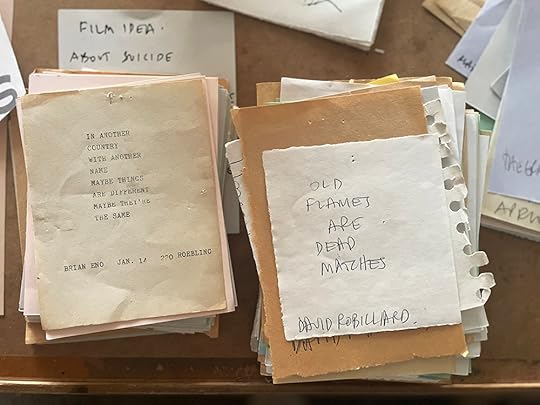

Infinite Dictionaries: A Conversation with Marc Hundley

Marc Hundley. Photograph by Na Kim.

Marc Hundley, whose portfolio of posters appears in the Review’s Summer issue, first moved to New York City in 1993 to model for Vogue with his twin brother, Ian. They were twenty-two and modeling was a means to an end—funding what Hundley calls their “club kid” lifestyle. As their final job in the industry, Marc and Ian walked Comme des Garçons runway shows in Paris and Tokyo alongside the supermodel Linda Evangelista, for a payout of two thousand dollars each. The two brothers then moved from Manhattan to the apartment in Williamsburg where Marc still lives. In the late nineties, he worked as a carpenter and still-life photographer before beginning to make T-shirts and posters for his friends in the downtown club scene, which led him to an interest in text-based art. His prints and drawings often take the form of flyers that play with the associative potential of text and imagery. He still works across various disciplines including graphic design, carpentry, photography, and fine art.

Hundley’s portfolio for the Review’s Summer issue constitutes something like a diary of several weeks he spent exploring the magazine’s archives this spring. The posters he created connect imagery and text in unexpected ways: each includes a particular phrase that caught his eye and pays homage to a work of art found in the same issue. (Four of these posters are now available to purchase in the Review’s online store.) In June, we sat down in his large studio in Bed-Stuy on chairs he had built. We shared a bottle of natural wine and talked about his work, the intimacy of being a twin, and how to write a love letter to a stranger.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever used your work to send somebody a love letter?

HUNDLEY

I have, and usually they’re love letters to people I don’t know. I once made a photocopied flyer that included a quote from a Magnetic Fields song—“While we’re still holding on, counting days until we’re gone, can we spend some time alone in our free love zone?” I added my address and the date, and I left part of it blank so that whoever picked it up could write in their own address. Another time I used an Arthur Russell quote—”I hope you need someone in your life, someone like me”—along with the date and place of one of my exhibition openings. I put romance into my work. Sometimes I think, I’m lonely, I’m single, I have no game—but then I realize that if there’s something I can’t say out loud to a person, I can use that. And I can be inspired by any kind of relationship. One of my pieces reads “It’s time that we began to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again,” from “So Long, Marianne” by Leonard Cohen. That was for my brother.

In Marc Hundley’s studio. Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

You like making what you call takeaways—flyers, pamphlets, postcards. What appeals to you about this form?

HUNDLEY

When I first moved to New York and was learning about art, I was very influenced by House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home by Martha Rosler. She writes that art succeeds better in reproduction. Most of the work we know and love, we never see in its original form. I like takeaways because they’re not precious. I can give you something and you can throw it out or keep it. It’s almost like a book—you can either read it now or read it later, when you’re in a different headspace. It’s not like a piece that’s in an art gallery, where there are no seats and usually no bathroom—there’s not a lot of time for a piece to actually do its work on the viewer. The longer you get to live with a work, the better.

INTERVIEWER

How do you decide whether a work is going to be a painting or a book or a T-shirt?

HUNDLEY

I’m always writing down quotes from songs or books or poems, and always collecting images. When I’m about to make something out of them, I ask myself, Is this something I want to say to a lot of people? If it is, I might make a free takeaway—maybe something photocopied and cropped. If I want to say something loudly, I’ll make the piece big, and make only one of it. But if the thing I want to say is more subtle, which it usually is, I’ll make it something small.

Marc Hundley. Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned your brother, Ian. What’s it like being a twin?

HUNDLEY

I appreciate it more and more as I get older. We’ve always had a good and very close relationship. The first time we lived apart was when I was thirty-eight. I think being a twin can interfere with the need for another kind of intimate relationship, like with a partner—I’ve already got someone, so the need’s not there. He could say he hates me, that I’m disgusting, and I wouldn’t believe him. He’s still the person.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about putting together your portfolio for the Review. How did you approach the magazine’s archives?

HUNDLEY

The Paris Review project was about using one thing to say another. The archives were like a catalog. They gave me a dictionary to work from. It’s like what W. H. Auden says—if I was on a desert island, the book I would want is the dictionary, because it’s infinite. A novel is finite in how many ways you can read it, and the Paris Review archives contain so much—I thought, If I couldn’t say something out of what’s in these things, then I have nothing to say. I liked the idea that the posters would lead people back into the archives that had inspired me.

In Marc Hundley’s studio. Photograph by Na Kim.

Na Kim is the art director of The Paris Review.

July 25, 2022

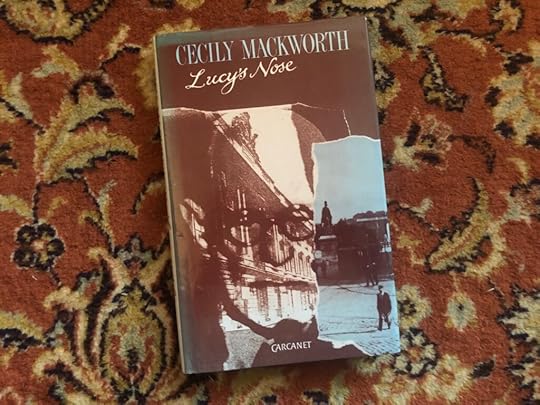

Re-Covered: Lucy’s Nose by Cecily Mackworth

PHOTOGRAPH BY LUCY SCHOLES.

In the winter of 1892, in his consulting room at his home on Vienna’s Berggasse, Sigmund Freud treated an otherwise healthy but “laconic” English governess suffering from both a loss of her sense of smell and olfactory hallucinations. The most unsettling of these was a pervasive odor of burnt pudding that worsened whenever she was feeling agitated. Miss Lucy R., as Freud refers to her in his and Joseph Breuer’s Studies on Hysteria (1895), was a thirty-year-old woman, originally from Glasgow, living in the home of a managing director of a factory on the outskirts of the city. She was looking after his two children whose mother, a distant relative, had recently died. Freud interpreted Lucy’s symptoms in accordance with his—then, still nascent—theory of hysteria, a condition in which the troubles of the mind manifest themselves in torments of the body. After nine weeks of sessions, Freud came to the conclusion that Lucy was secretly in love with her employer. When this hypothesis was proposed to her, Lucy agreed immediately, her symptoms disappeared, and the analysis was brought to an end.

Unlike some of Freud’s more famous analysands, the case is not especially noteworthy, and Lucy herself remains something of an enigma. Nevertheless, a century later, the Welsh journalist, poet, and writer Cecily Mackworth, who was then in her eighties, went to Vienna to find out what she could about the real woman behind the pseudonym. She encountered a series of dead-ends; few of the city’s official records survived the cataclysmic destruction of World War II. Yet, as the real Lucy—whoever she was—drifted ever further out of Mackworth’s reach, a different Lucy begins to take shape in Mackworth’s imagination instead.

Lucy’s Nose (1992), the book Mackworth published about her quest, is an act of imaginative audacity that mimics Freud’s imposition of narrative onto the fragmented stories his patients told him about their lives. Mackworth employs both her powers of deduction and imagination to piece together an entirely credible but utterly fictional story of Lucy’s encounter with Freud that fills the gaps, silences, and elisions in the original case study. The life that emerges on the page is less a unified, uninterrupted narrative and more a series of novelistic episodes interwoven with Mackworth’s reflections on her own experiences. “At what point does fact drift into fiction, possibilities become translated into probabilities, one kind of reality give place to another?” she asks in the book’s opening line. “What and where is the borderline between biography and a novel?” Part hybrid novel, part memoir, part travelogue, Lucy’s Nose unfolds in these borderlands.

***

Lucy R.’s story begins back in Calvinist Glasgow, “where thousands of fires stoked with cheap coal spread a veil of smutty fog over the streets,” and even the icy flagstones on the pavement shine “black under the gas-lamps.” This sooty, gray city, Mackworth tells us, contrasts starkly with the “bright colours and exuberant architecture” that await Lucy in Vienna. Mackworth gives Lucy’s employer the name of Meyer. She calls the two children in her charge Mechtilde and Mitzi. Their grandfather—who, in Freud’s account, is mentioned only in passing—becomes “a spritely old gentleman,” technically retired, but still meddling in the running of the factory, “a source of annoyance to his son.” The mistress of the house welcomes Lucy into their family when she first arrives, proudly showing off the city’s sights—the great Ring, the Parliament building—and calls her “little cousin” in tender moments. Shortly thereafter comes the scene of her death, which—in Mackworth’s telling—replays itself in Lucy’s mind after she has described it to Freud. “When I am gone, my children will be motherless,” the dying woman begs. “Promise me you will always be there to take my place and care for them.” Meanwhile, “Herr Meyer stands at the foot of the bed, rigid, his face stiff, because he is Herr Direktor and must remain in control of himself and his subordinates.”

Lucy’s Nose describes this world in sumptuous detail, moving vividly from the Herr Doktor’s flamboyant, cluttered consulting room to the grandeur of Herr Meyer’s house, with its roaring fires and staff of servants, between bustling coffeehouses and the fair at Luna Park. Mackworth writes scene after scene of captivating, highly believable description and dialogue that center on the two-month period during which Lucy’s analysis took place. She recreates these sessions—Lucy “seated nervously on the edge of her chair,” on her first visit; the doctor, meanwhile, with a look of excitement in his “large, dark and extremely shiny” eyes as he questions her—but also spins all manner of additional episodes around them, inspired by tidbits found in Freud’s original text. We see Lucy at home with the Meyer family, and Freud with his own children, or discussing his work with his colleagues. Mackworth peppers this narrative with snatches of authorial commentary: “(This man, who will be important in Lucy’s story, must have a name and ‘Meyer’ seems neutral, suitable for whatever sort of person he will turn out to be. What did he make in his factory, I wonder? Furniture comes first to my mind and seems right, or at least as likely as anything else.)” Rather than serving as distractions, or stumbling blocks in the plot, these asides are integral to Mackworth’s unorthodox narrative form.

Once Lucy leaves the house on the Berggasse, Mackworth’s investigative trail goes cold. The impending wars cast ominous shadows on her possible future. Assuming she lived that long, did she eventually end up in Auschwitz? (Lucy must have been Jewish, Mackworth reasons, because “it would have been difficult, back in the 1890s, for a non-Jewish girl to follow the path from Glasgow to the Berggasse, and because her employer belonged to the middle-class of industrialists who were mostly Jewish at that time.”) Or did she somehow survive? Could she have been living in Vienna still when Mackworth herself first visited, as a journalist, in 1946?