The Paris Review's Blog, page 73

September 20, 2022

Has Henry James Put Me in This Mood?

A collage by Dennis, reflecting her interest in how interior spaces relate to feminism. Made in 1971 in her loft on Grand Street. Courtesy of Donna Dennis.

Ted Berrigan was the first in the circle of poets around the Poetry Project at Saint Mark’s Church to ask me to design an announcement mailer for one of his readings. He encouraged others to do the same. In the late sixties, I designed a number of flyers and covers for mimeographed poetry books. These gave me the first public exposure for my work.

Ted and I saw one another off and on for about five years. In the spring of 1970, we lived together on Saint Mark’s Place in the East Village, until June, when Ted went to teach a course in Buffalo. I moved into the artists Rudy Burckhardt and Yvonne Jacquette’s loft on East Fourteenth Street while they summered in Maine. Ted stayed with me for a number of weekends that summer, and he proposed that we undertake a collaborative book. As I remember, I began the collaboration by making drawings with empty word balloons. I’m pretty sure Ted provided the project’s title at the outset. Ted would take the drawings—I think I made them in batches of four or five—back to Buffalo, where he began to fill in the words. We went back and forth this way, sometimes in person, sometimes by mail. I had forgotten all about this collaboration by the time Ted Berrigan’s youngest son, Eddie, contacted me in the summer of 2018. He wanted to bring me something his father and I had done together, which had recently turned up. As I looked at sixteen pages of my drawings and Ted’s handwritten words, the memories came back. These diaries describe some of them, along with the artistic milieu I was in in New York at that time—which included the painter Martha Diamond and the poets Bernadette Mayer, Michael Brownstein, Anne Waldman, and John Giorno.

The summer of 1970 was a turbulent time in our relationship. Where would Ted be in the fall, and with whom? Could I live with someone and make my work in the same space? In September I moved out of Rudy and Yvonne’s place and into a loft on Grand Street in Little Italy. One day, Ted came to pick something up while I was at work. I had left him a note saying that I couldn’t go on with the relationship. He left a note in response, clearly upset. Separately, we each created one more drawing for our collaboration. I made an angry alternative version of the cover and Ted made an angry drawing for the end. Neither of us ever saw these private expressions of pain and disappointment until Eddie brought the long-ago collaboration to me in 2018. I had kept mine over the years, and now here was Ted’s.

In the end, Ted and I remained great friends. When I completed a new piece, he’d often be the first to see it. His enthusiastic reactions and always interesting observations meant the world to me. When he died in 1983 at age forty-eight, I realized that he had been my mentor. One thing I learned from him was to always finish what I began. I learned that when I kept going, past the hope of creating anything good, I often had my breakthroughs.

May 30, 1970

Have been working hard since Ted left. It was way past time. But I’ve finally surfaced through despair and nausea and a two-day headache. I’ve done one acceptable (for now) self-portrait in oils and today I did four or five India-ink drawings with word balloons for Ted to fill in. In both cases (oil-painting) and drawing (from photos) I’ve surprised myself.

It is such a relief to be working—really working with my hands—eyes—head—heart for hours at a time. Whatever else one can say for or against it, working on paper & canvas keeps you busy.

I’ve so much work to do—drawing, at last, is something I know I want to have—and it will take work, many, many drawings—gradually getting better with practice & thought and involvement. I feel almost as if I’m waking up from some dream in which I sat waiting for works to happen like magic when the feeling was on me. Now I feel that I should do one drawing perhaps every day.

Monday night I had a brief but nearly total depression. I thought if I couldn’t begin work again and find satisfaction in it, there would be no reason nor shape to my existence. To me.

Ted is wonderful but being with him and not working was becoming a nightmare. I want him to be here next fall—but if he is, there will be the challenge of finding the time and privacy to work and work hard. It will be absolutely necessary to meet that challenge and resolve it successfully or else I will have to live alone.

I “slipped” on the phone today and let mother guess I was talking on my own telephone. I said, “I just got it.” She said, “You didn’t tell us.” I really don’t care—or can’t afford to.

May 31, 1970

Oh, to have my only work be my art work. I’ve just woken up at noon. I won’t begin work yet for maybe several hours, but I’ve promised myself to do four or five drawings today and already there is purpose and excitement to my day. Everything I do will be working up to doing that drawing.

In the last two weeks I’ve read The Town and the City by Jack Kerouac, a really full and inspiring book. If I could get the “sweetness and sadness” of life, all of it into my works as Kerouac does, I’d feel my works were really worthwhile. I think I am coming to understand what Ted means about getting more than just flashes into your work—about getting everything in. Aiming at only the great ecstatic moments is what put me in the position of waiting and waiting for the work to come. That is no way to work. I think maybe that is what I’ve come to understand in the last week.

June 9, 1970

Rented a Polaroid today and took pictures of Jim Carroll—to use on the cover I’m designing for his book 4 Ups and 1 Down (four love poems and one hate poem). I had fun with the Polaroid (I want to own one) and I got one picture that I think will be good for the cover.

I went down to Les Levine’s this morning at 9:00 to see if he had any good pictures of Jim (he didn’t for my purposes & I woke Les up though we’d had an appointment). Coming back in a cab, I saw a man dragging a big square piece of plywood across the street to plunk it down next to a big earthy hole he was digging in the street. The plywood looked as if it might cover the hole. I felt a vague excitement—a stirring of memories about how exciting a hole with earth heaped beside it had been to me a few years ago—I remembered digging for red clay—digging into a hill, digging for Australia, digging ’til water came in, the danger of digging a deep hole and getting inside, etc.

Collage made as a proposed cover for “Memorial Day,” a long poem by Anne Waldman and Ted Berrigan. Courtesy of Donna Dennis.

June 10, 1970

Had a great long talk with Martha about working, about boyfriends, about working with boyfriends around, etc.

Then Ted called. Another great but briefer talk. He asked me if I wanted to come see him—I said YES—he said O.K. and maybe I can stay for awhile and we can see Niagara Falls and visit painters there and look out his 8th-story window at the Poussin-like landscape and there’s a big desk where I can do great works.

He says he’s working on putting writings to the drawings I did—might need more drawings. He wants his mail sent, says he’s really getting into poetry, wants me to pick up some of the Sonnets for him—and he’ll be here a week from Friday—about the time I get home from work.

June 11, 1970

Went to see Red Grooms’s show Tappy Toes at Tibor de Nagy today. It was violent, rich and exhilarating. I returned to work feeling cocky and giddy and inspired to get a bit of the Red Grooms’s zaniness into my cover design for Jim Carroll’s book. Especially appropriate because Jim and Devereaux happened to be at the show the same time I was. And on the street outside, I met Larry Fagin and Joan Inglis.

As I’ve been walking around the city lately, New York has been looking quite wonderful to me. I found a terrific street just below Gramercy Park today between 3rd Ave. & Irving Place that had all kinds of houses. There was a Spanish one with a tiled roof and a beautiful tiled doorway below street level that looked wonderful, cool & inviting.

And then there was a kind of Dutch one with a stepped roof.

On Irving Place up just below Gramercy Park there was a doorway inside another doorway that was the richest, darkest, shiniest, classiest, most opulent doorway I’ve ever seen. Wide and generous and exclusive with gas lamps mounted on either side.

Along the west side of Gramercy Park, I found a row of New Orleans-style houses that looked cool and relaxed and southern with their white wrought iron porches and balconies. On one balcony someone had put a round wrought iron table and two chairs—and a vase of flowers on the table. A big, shiny motorcycle leaned near the doorway of another house.

Has Henry James put me in this mood? I was inspired to see New York through Red Grooms’s eyes too, though it all seems quite ’40ish & ’50ish that way—or maybe it’s just that his New York is like the New York I saw in childhood Little Golden books. There was a wonderful interior of a taxi with a frame in the shape of the taxi sign.

June 12, 1970

The cover for Jim Carroll’s book 4 Ups and 1 Down is finished. I’m pretty happy with it. Jim striding through a black sky filled with whirling, flashing stars.

Dennis’s cover for Jim Carroll’s 4 Ups and 1 Down, published in 1970 by Angel Hair, a press run by Anne Waldman and Lewis Warsh. Courtesy of the Morgan Museum and Library.

June 19, 1970

Sitting here in Rudy and Yvonne’s loft (airy, bright, late-afternoon feel) drinking wine, waiting for Ted who said he’d be here soon.

Still getting the feel of this place. I haven’t had much time for contemplation yet. Monday, late, Lewis MacAdams and Tom Veitch helped me to move in here. Tuesday, I had Fran Williams and Bob Cobuzio and Martha here for Fran’s birthday—one day late. I gave Fran a fish poacher with a paper fish made by me inside—stuffed with little candies. The dinner was not a great success because I wasn’t used to shopping here or cooking in this kitchen. I thought of giving Fran keys for her birthday so that she could work here in one of the back rooms but I want very much to be by myself at least until I know what I want to do. (The workspace here is quite inspiring.)

Last night I went to dinner at Larre’s with just about everyone—a kind of farewell for the summer. People there were:

Ron & Pat Padgett

George & Katie Schneeman

Anne & Michael

Clark Coolidge

Tom Veitch (later)

Gerard Malanga

Tessie Mitchell

Bill Berkson

Carol & Dick Gallup

Jim Carroll

Joan & Larry

I sat beside George & Larry & across from Ron. We ate at the long table in the garden under a tent but there was a terrible rainstorm and it was rather damp & funny.

Later we went to George’s where George did a giant nude portrait of everyone sitting in a corner. Larry took movies. I really wanted to be part of it all (it feels weird, too, to have your clothes on when no one else does) but I had to get home to get some sleep.

Jim made a special point of telling me how much he liked the cover I did for his book 4 Ups and 1 Down. Anne said it will be printed by Monday.

The question now: What works?

Since it’s been bothering me for years—should I take the time to acquire the traditional tools of the artist—esp. drawing? Even if I don’t use it, it might set me free for other things. Or is this desire to learn to draw just a basic insecurity that I should overcome by pure guts?

June 23, 1970

Got a $25 refund from the government today (miscalculation on my part) so I paid some bills and my debt is down to $800 (not counting what I owe Daddy for the loft security deposit).

Ron and Pat and Wayne Padgett came over to bring me plants I will keep for them this summer.

I did four drawings tonight for Ted’s collaboration. They’re a little looser & I hope more interesting because I know they’ll be used.

June 25, 1970

Just woke up from an after-work nap. I’m going to try that for a while and see if that’s a good way to get into work. I wake every morning to the new day and all the bright light in this place— so excited and at peace and full of the new day. But gradually as I have to leave and go uptown and the day wears on, the good feeling drains away and when I get back here, it’s hard to feel great about going to work. So the new plan is to take a nap. Then wake up and work. There isn’t the morning light but there is the waking up and beginning again.

I went to Andy Warhol’s (the Factory) today to get Andy’s new flower print for Ted and from Gerard Malanga three prints each for Ted and me of self-portraits (photo-silkscreen) Gerard did for his new Black Sparrow book. Andy rode up in the elevator with me, and we talked about the weather. “It’s really getting hot!” said Andy. “I know, and very heavy,” I said. Then I remarked on the mirror at the end of the hall, and he said, “I don’t know why they put that in. When they raised the rent, they put in that mirror but they didn’t put in other things that we needed more.”

The print Andy gave Ted is very beautiful lavender and yellow green and fuschia and chrome yellow with a wonderful violent green darkening around the fuschia flowers’ edges.

Rudy and Yvonne called last night to see how things were and asked me to send some film up to them. Yvonne practically insisted I come up to see them in Maine. We talked about how much work we were getting done. I had a great feeling that I have some obligation to Yvonne and Rudy to make good use of their place. To get some good work done to show them what a wonderful thing they have done for me in letting me use their place this summer.

I have the Warhol print up now. It certainly is totally inspiring.

Thinking of doing a new (and color) version of my star print—using the variety of stars I used in Jim’s cover—I remembered my idea about white flowers bursting in the night sky. Bursting, blooming. I could do a combination of drawn flowers, engraved flowers, photographed flowers—in different colors, etc.

Maybe there could be a nude in it. —Nude in the Garden. Look up some N. Renaissance things!

I’M GOING TO FLOWER. Blossom out.

Plant works. Growing things works.

Everything humming, spinning, filigree, fine, like things were when I was on acid and it was SPRING. And I had POWER. I am in command!

It has just occurred to me that the way things looked to me on acid was a bit like Van Gogh—(though not so brutal). Even Ted’s face when I wasn’t on top of it (the acid)—looked greenish and moving (physically) when I looked at him—like Van Gogh’s green-faced self-portrait.

I think, too, of Matisse’s The Green Line. Portrait of Mme. Matisse.

Wow! Feeling better and better—I know what I’m going to do—my LSD trip turned my visual experience up a key—and I’m going to do it (my work) with much more force, pizzazz, and COLOR.

As with Jim Carroll’s cover. I did my usual thing (or another version of the star lady) and then I realized I wanted to pull out all the stops—turn it tighter and brighter and I knew how and I did.

A kind of new sense of motion. Not things just moving as units but every molecule, particle in each unit spinning and spinning and giving off sparks to make the whole thing incredibly larger than life (as large as life) and there (here) and aggressively, evilly, dazzlingly beautiful.

WOW. I would like also to do this flower, star work I’m thinking of large to take in a whole eye-span. What sort of a surface—what sort of a shape should I give that surface. JESUS. I know what I want to do for the first time in years.

Photograph of Dennis jumping, taken by Martha Diamond in Rudy Burckhardt and Yvonne Jacquette’s studio, where Dennis spent the summer of 1970. Dennis planned to use this series of photos for her “jumping lady print.” Courtesy of Donna Dennis.

June 27, 1970

Martha just came over to take pictures of me jumping, nude, for the large print I want to make. She told me that Tandy Brodey heard from Jane DeLynn that Alice Notley is in Buffalo. Gossip. But I know it’s true. Somehow, though, I’ve just shed a few angry tears and feel some despair about what I can expect in the future. The future. I can’t feel too angry at Ted as I sit down to write about it.

(Edwin Denby just called and he is taking me out for dinner. Isn’t that great—and when I was feeling so low.)

This morning, when Ted called, asking me to wire $25, he said, “Maybe I’ll come down next weekend—since you can’t come here.” (Now I know why I can’t come there.)

Still, Ted does seem to be trying to balance things out, to make amends to me. When he was here, he said, “It was great; I wish I could come down here every weekend.” And he did come.

And then he called this morning and asked me to send him some money. (I wish I could understand how a man could love two women!) Is it time for me to be more aggressive? At least more aggressively me. I’m going to turn up all my dials the way I did with the Jim Carroll cover.

July 1, 1970

New York’s new abortion law went into effect today.

Last night, I felt pretty down and lost after work, though I cheered myself with a resolution to go to Martha’s as soon as it grew dark enough to print up the photos for my new super-great silkscreen print. Then Phoebe and Lewis MacAdams called to say they would come by and get me for the Museum opening. As we turned onto 53rd Street, Phoebe told me how terribly moved she’d been by my jumping lady print at Martha’s. And I said, Wow, it’s really great to hear someone say that, it really makes me feel good, because Ted doesn’t like my work, thinks it’s too slick or something—and Lewis said that’s not true. He told me he did like your work—but that you didn’t feel so good about it. TERRIFIC UP #1.

Then we went inside the Museum, past my little friend the Russian guard (he must have been rather handsome in younger, svelter days). Right away we saw people we knew. Bernadette, Michael, Brigid Polk, John Giorno. There were drinks, great loud “jukebox” music and the garden looked beautiful. Glamorous NYC. We drifted about and Lewis was friendly and confidential, asking me how Phoebe seemed, telling me how his father arrived at a reading he gave last year with two limousines.

I had a friendly, easy chat with John Giorno, then Phoebe began to tell me how much the jumping lady print had impressed her. “I’m a little bit pregnant and pregnant women feel things in a very strong and hard way and that print made me want to cry. It was so beautiful. It’s so true,” she said, “and I’ve been dealing with shadows a lot lately.” WOW, I thought. This is what I make art works for and I told her I’ve been moved to tears by other people’s work and I’ve always wanted to make works that would move other people to tears. And then she started talking to me about Ted. “Listen,” she said, “If you are going to be Ted Berrigan’s girlfriend you’ve got to be STRONG,” and I said, “I know.” Actually I didn’t get, or remember, all she was saying—but the gist of it was—you’re great, you’re strong, you’re beautiful—know it and be it all the time. We hugged and grinned. TERRIFIC UP #2.

July 14, 1970

I’ve been in this loft almost a month now—but I do feel I’ve accomplished things, especially if I finish up this print tonight.

Feeling a little fuzzy in the head from lack of sleep and lack of food. Wow. Am I running on adrenalin now. Losing weight too, which is nice.

What I like is that I’ve called on my strength and force and power and optimism and they’re there and serving me beautifully. I feel exciting, strong, bold, daring, ready to take on anything and succeed.

One thing I remembered today that gave me greater courage … When Lee Crabtree was over, last spring, just the evening Ted came back from R.I., the time everything was so great and he’d told his mother about me, Lee analyzed my handwriting and said—you’re not as aggressive as it is in your nature to be. And Ted said, “Pretty good, Lee.” And then I felt happily aggressive and Ted and I had one of our most terrific love-makings ever. The point of remembering this is—It is in my nature to be more aggressive—so I can be plenty—and Ted probably wished I would be more aggressive more of the time. The chances are he’ll be very happy to find the new Donna.

July 26, 1970

What I did today. Woke up. Thought about Ted. Felt O.K. Felt pretty good, even. Had breakfast. Put together Ted’s hi-fi. Listened to Ted on John Giorno’s pornographic poem. It was great that he laughed on it just a little.

Went for a walk along Eighth Street to buy this notebook. Incredibly hot. Came back here. Called Tom Veitch. He can’t come over tonight. He’ll call tomorrow. Read the Sunday paper. Cried some. Started writing in here. Ate a few eggs.

Now I’m listening to the new Bob Dylan album I bought today with my Mastercharge. Dylan is singing “In the Early Morning Rain.” Wow. Ted’s song.

I have a sense today I’m listening to music with a new depth, really hearing, not being afraid of any human emotion. Older, wiser, mellower, more understanding. In the past week I’ve felt I really have come to understand what Ted was trying to tell me last year. That art is all about your feelings—not just the great ecstatic moments—all your life and feelings have value. I thought this as Ted lay in my bed and I was not happy and he was not happy but it was real life—my life. What I mean to say is—I think I’m ready to make great mature real works in a steady strong way—no longer the high thin ecstatic dreaming way of working that worked so rarely. Now it’s everything.

September 16, 1970

Sitting cross-legged on my orange bed in my new white loft with high black ceiling on Grand Street. Sounds of San Gennaro festival clean-up outside. It’s 1:30 A.M., but I’m trying not to notice I’m tired for I must learn to stay up working ’til 2 or 3 every morning now. Ted calls me a lazy-ass and he’s right. I want it soft, he says. Yes, I’ve been complaining a lot. About having a job. About having no heroes. About not being taught how to draw. But those are excuses and if I accept them as obstacles to my work and therefore fail to work, well I’ll just lose that’s all. What I want is to make great works. I’m an artist. Ted says an artist never lets money come between him and his art. For the time being I need a good deal of money so I need a job so, though I’ve just lost my job with the Paul Bacon Studio, I’m looking for a job. A job takes time, but it can’t become an excuse for not being a working, producing artist. If I need more time, I take it from sleep-time, social-time, etc. That’s all.

Courtesy of Donna Dennis.

September 20, 1970

Just back from a wonderful evening with Yvonne and Rudy. Still cringing a bit at how awkward I am saying goodnight to people but excuse myself this time since I was dazed from seeing Satyricon. Wow. I’m completely wiped out. Guess I liked it.

Yvonne served a good dinner, we talked about parents (Yvonne’s father threw Rudy out of the house), Rudy’s in-progress movie about drugs, looked at Yvonne and Rudy’s summer paintings. Both very nice. Yvonne all sky and clouds. (A terrific sky through barn window.) Rudy all deep quiet forest. Yvonne gave me a photo of a study of her fluorescent light painting in exchange for a horizon-change print by me.

Did four drawings today which I don’t dislike. All very different. Yvonne said Ted said of me, “She’s so good at small things I don’t see why she has to do anything big.”

September 28, 1970

Started a new job today at Grolier. It will be O.K. I think, but will perhaps push me more toward my own work.

Mailed a letter off to Ted. The envelope looked terrific with stickers and stamps and little drawings. I’m quite proud of it and feel it’s a good work. I should be more generous and send more letters and drawings to more people. Everything I do can be an artwork.

A kitty is watching the pen as I write this. I got two little gray kitties last Friday. They’re completely sweet and scary. I’m not sure how I feel about having them here. I’m waiting for names to come. One has blue eyes. The other looks constantly worried.

Saw the Picabia show at the Guggenheim. I want to go back.

Larry Rivers’s “non-intellectual” approach interests me—his early career. The way he went about being an artist. “Every time I become interested in my own contemporaries, I feel that I am becoming unsure of my own direction.”

What I have to do is to come to trust myself—all of me and my intuition again.

October 4, 1970

Took my jacket sketch for Brainstorms to Bobbs-Merrill today. I think it’s a little slick and commercial. They loved it.

I’ll also be doing the whole inside design, etc., as well as illustrating it with drawings. Michael said he thought the drawings I did for Spirit in the Sky were terrific.

Anne asked me to do the cover of the second World Anthology. I’ll photograph the audience at Wednesday’s reading (with luck). George’s nice design was rejected. I feel a bit like the compromising hack in this one but then it was me or some outside designer, so I guess it’s O.K. And I’ll try to make the most I can of the opportunity for the sake of the Saint Mark’s Poetry Project. Documentary—personal approach.

In 1970, Donna Dennis and Ted Berrigan created the book The Spirit in the Sky, which was never published. Courtesy of Donna Dennis.

October 7, 1970

Ted was at the reading tonight. Back from Europe I don’t know when. When I came in he had his arm around Bernadette Mayer. So what? But still ….. He was back and he hadn’t seen me. I was taking pictures for the World Anthology cover so I was walking all around. Passed him. Smiled. Knelt down, told him what I was doing—taking pictures. He rubbed my back and asked me to take pictures of him and Lewis Warsh. They read a collaboration written at Rudy’s this summer where he refers to me as half his vital organ. He left early. So did Alice.

I put on a brave front and everyone was friendly to me and now I’m home crying. Why can’t Ted play it straight?

Still, I enjoyed at the reading tonight being my own person and not somebody’s girlfriend.

October 19, 1970

I’m thinking to write, wow a dying love doesn’t go without an incredible struggle. Well there, I wrote it.

So what happened today? Well, I went to John Giorno’s party at the Gotham Book Mart and Ted comes in with a present for me—One Hundred Years of Solitude (!—why that!) by Gabriel García Márquez and Scenes Along the Road, photos of Kerouac, Ginsberg, Orlovsky, etc. Said he was sick on my birthday and had no phone. Said he wanted to come by later to pick up his Jim Dine work. O.K. I nodded. He imitated me and said, “Wow, Donna, you’re so tough. It scares me.”

Anyway, an evening of working on Michael’s drawings shot and he never came by anyway, goddammit. I can’t let that happen again. These drawings must be good and they must be done! Maybe I take the phone off the hook tomorrow. To feel free of Ted might feel great!

And horrible.

Next Monday I sit for Alex Katz. I feel so much more that I have a community now. Everyone’s being great and things keep happening.

December 11–12, 1970

I am in one of the great, opening up, gaining ground times of my life. Comparable to my freshman year in college. Hard, painful, scary, exciting and so full of hope and faith. I’m learning to know myself all over again, better than I ever have. I’m coming to terms with myself in a way that can open up the future to be what I want it to be. Anne wrote in the book she gave me the other night, ”May all your wishes come true!” They may! The way is opening up for that to happen. And there is less and less reason, with every new day, for me not to go where I want to go, do what I want to do. I’m learning again to trust my hunches and my intuition. I knew about all I’m learning now, but I didn’t really understand it. I only knew what I wanted and what I feared. But not why. Now I’m gaining clarity every day.

What I am coming to understand is what it is to be a woman in this world. What it is now and what it can be and why.

I’m learning how women are their own worst enemy because they learn not to believe in their powers. Power is what I’m beginning to feel. I’m reading Betty Freidan’s [sic] The Feminine Mystique. It’s changing my life (or shaping that change) at a time when I am open and free to change in a major way. To GROW.

February 14, 1971

Lucy Lippard came to see my works today. Yvonne Burckhardt had recommended my work to her very highly, for an all-woman show at the Larry Aldrich Museum.

I’m not sure what she thought. She stood too close, I thought, and looked at each piece for a long time. Especially the one with mirrors slanted in. She said she thought the one with lightning and lights worked very nicely. I was sorry she could not see them at night. They really look 100 percent better then. I’m beginning to be sorry that I didn’t buy window shades that really block out the light.

Martha and Denise Green and I went to the Women’s Liberation Center to attend a meeting on How to Start a Consciousness-Raising Group. There was not much real information given out and a lot of random discussion but I’m very excited at the idea of forming a group.

Lucy Lippard also holds some kind of artist’s group and is also compiling a file of women artists.

This all seems terrific to me. Here finally is a chance to meet and discuss with other artists, find out about opportunities for exhibition, etc.

Courtesy of Donna Dennis.

February 20, 1971 (early A.M.)

Yvonne and I have talked of interior spaces in the art of women (her term). I’m rethinking my works and everyone else’s. I have been continually interested in interior spaces.

Interior space has nothing to do with Renaissance space which was made by men—and which was made so that there was a place to put the people. Yvonne sees interior space as being empty and so do I. That is why, of course, I did not want my mirrors to be big enough to reflect anyone, or anything, except perhaps a floor or ceiling, which showed more emptiness. I’m fascinated by an empty storefront on 3rd Avenue. All the interior surfaces of the display case are mirror surfaces.

I’m becoming very sensitive to older buildings. Their vulnerability. Like Atget. I want to take photographs and record their existence and their last days. They are very beautiful and very sad. I like Walker Evans front-on approach to buildings. That is my natural approach too, but without seeing him I might not have dared.

Donna Dennis is a sculptor known for her large-scale installations and public art inspired by American vernacular architecture. Her work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, the Neuberger Museum of Art, and SculptureCenter, among other institutions.

Excerpts from Donna’s journals from 1968 to 1982, which have been coedited with Nicole Miller, will be published by Bamberger Books in late 2023; a monograph of her work is forthcoming from the Monacelli Press in March 2023.

September 19, 2022

Terrance Hayes’s Soundtracks for Most Any Occasion

Photograph by Jem Stone, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

When we asked Terrance Hayes to make a playlist for you, our readers, he wrote us a poem. Of course he did. As Hayes told Hilton Als in his Art of Poetry interview in our new Fall issue, formal constraints offer him “a way to get free.” Many of Hayes’s poems derive their titles from song names and lyrics; others are influenced by the mood of a particular album or track. Music, he tells Als, “changes the air in the room.” This particular playlist-poem has a track for almost any kind of air—or room—you might find yourself in this week. Read and listen to “Occasional Soundtracks” below.

Soundtrack for almost any morning: “I’ve Got My Mind Set on You” by James Ray

Soundtrack for twelve minutes in the bathroom: “Mind Power” by James Brown

Soundtrack for grooming: “Look” by Leikeli47

Soundtrack for any occasion: “Your Sweet Love” by Lee Hazlewood

Soundtrack for a Friday night: “If It Wasn’t True” By Shamir

Soundtrack for a carefree, slightly bittersweet day: “Free” by Deniece Williams

Soundtrack for internet surfing: “Expensive Shit” by Fela Kuti

Soundtrack for freestyle song and dance in the hall: “A Million Days” by Paul Kalkbrenner

Soundtrack for a loose modern dance in the living room: “Blue Pepper (Far East of the Blues)” by Duke Ellington

Soundtrack for a range of low-key excursions: “Excursions” by A Tribe Called Quest

Soundtrack for dancing while cooking: “Don’t Look Any Further” by Dennis Edwards and Siedah Garrett

Soundtrack for most any occasion: “Islands in the Stream” by Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers

Soundtrack for Detroit-tough joy: “Joy” by Bettye LaVette

Song for walking for coffee: “I’ll Take Care Of You,” live at Western Recorders Studio, by Bobby “Blue” Bland and B.B. King

Soundtrack for a future Paris sunrise: “Paris Sunrise #7” by Ben Harper and the Innocent Criminals

Soundtrack for a moderately spiritual occasion: “How Far Am I From Canaan?” by Sam Cooke and the Soul Sisters

Soundtrack for an eighteen-minute siesta: “Dís” by Jóhann Jóhannsson

Soundtrack for idle walks: “The Homeless Wanderer” by Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou

Soundtrack for moderate walks: “Good Days” by SZA

Soundtrack for Saturday at the flea market or home depot: “Satisfied ‘N’ Tickled Too” by Taj Mahal

Soundtrack for standing in line for groceries: “A Man Is Like A Tree” by Albert Ayler

Soundtrack for awe at Joan: “The Ride” by Joan As Police Woman

Soundtrack for awe at Joan: “Valid Jagger” by Joan As Police Woman

Soundtrack for Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” inside a song: “The Creator Has a Master Plan” by Leon Thomas

Soundtrack for a disco-in-church kind of feeling, a.k.a. a song that encourages ass-shaking, singing, and clapping: “Over and Over” by Sylvester

Soundtrack for middle-aged people who still go to clubs that have bouncers at the door: “Wristband” by Paul Simon

Soundtrack for walking through the park: “State of Shock” by the Jacksons and Mick Jagger

Soundtrack for a Joan-and-Tony groove: “Enter the Dragon” and “The Geometry of You” by Joan As Police Woman, Tony Allen, and Dave Okumu

Soundtrack for public transit: “You Don’t Know What Love Is” by Rachelle Ferrell

Soundtrack for driving a Cadillac: “Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac” by Dizzy Gillespie

Soundtrack for big orchestral self-reflective occasion: “four ethers” by serpentwithfeet

Soundtrack for dinnertime background: “Cosmic Slop” by Funkadelic

Soundtrack for twenty-four-minute activities such as writing, bath soaks, and occasions you feel like the protagonist in an independent movie: “In Another Life” by Sandro Perri

Soundtrack for Saturday at the flea market or home depot: “Satisfied ‘N’ Tickled Too” by Taj Mahal

Soundtrack for quiet storms: “Seconds of Pleasure (Acoustic / Live)” by Van Hunt

Soundtrack for musing on your mortality: “It’ll All Be Over” by the Supreme Jubilees

Soundtrack for most any occasion: “Les Fleur” by Minnie Riperton

Soundtrack for most any occasion: “Fly Me to the Moon (In Other Words)” by Bobby Womack.

Terrance Hayes’s recent books are American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin and To Float in the Space Between.

September 16, 2022

Helen Garner, Daniel Halpern, and Keith Hollaman Recommend

Marilyn Monroe’s hand and footprints outside the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Photo by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0,

This week, we bring you recommendations from three of our issue no. 241 contributors.

Twenty-two years late I picked up Blonde, Joyce Carol Oates’s enormous novel about Marilyn Monroe. At first it jolted me with its jangling, sick vulgarity. My pulse rate shot up. I was trembling. I wanted to throw it across the room. But I also had to acknowledge immediately that it was brilliant. Three days later I dragged myself out the other end, shaken by a sort of angst and awestruck by Oates’s manic power, her huge imagination, her ability to command great cataracts of material—to convey a soul mortally wounded in childhood, laboring in its squalor to recreate itself.

—Helen Garner, interviewed in “The Art of Fiction No. 255”

I first read Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude in my family’s summer cottage on Doolittle Lake in Norfolk, Connecticut: an A-frame constructed in the thirties as an afternoon teahouse, with beautiful interior wooden beams and an immense rock slab capping the chimney. An occasional mouse, of course, would seek shelter in the loft spaces, but that August I started to hear a constant grinding noise at night that was not very mouselike. I tried to determine the source of this pesky sound, with no luck. Then one day, as I was completely locked into the last few pages of García Márquez’s book—when “all the ants in the world” are “dragging toward their holes” the “dry and bloated bag of skin” of a dead baby with the tail of a pig—the heavens broke open inside our cabin. A panel of insulation had collapsed from the weight of sawdust created by a colony of carpenter ants gnawing into the rafters. I jumped up from my chair in shock and terror, madly brushing them off, gasping from the physical and emotional reality of the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude—this was magical realism at its best.

—Keith Hollaman, author of “Dark Suit and Bow Tie”

Three-part insomnia: I awake at 4 A.M. with a divided mind anchored to the word snake. How it is the perfect representation for the reptile it embodies—starting with the apprising sibilant, then quickly moving off the page by way of a speedy quartet of letters. A lightning-strike piece of diction. Like calling out fire in a crowded space. But while snake is an auditory slither, fire is a fist. That is the first of my early morning’s non sequiturs.

Then I think about my current reread of The Age of Innocence, a nearly perfect novel (Wharton is a kinder, American Flaubert), and of the canniness of Wharton’s depiction of May, who is the true archer, the personage of the bull’s-eye and the off-stage orchestrator of her novel. I find it challenging to understand why Newland Archer doesn’t climb the five flights of stairs to Ellen’s apartment, where he would have found the woman of his true passion—and handily displaced the Frenchman. It’s worth reading the last chapter again for the subtleties planted there: “Perhaps she too had kept her memory of him as something apart; but if she had, it must have been like a relic in a small dim chapel, where there was not time to pray every day.”

And before rising for the day, as the sun rises, I let the memory of Wu Tianming’s 1996 movie The King of Masks come back into focus. I see the many faces of a man who, at the end of his life, wants a grandson to continue the art of mask opera and ends up with something equally beautiful that he could not have imagined, in whatever guise. I might have been dreaming of my daughter earlier. I might have allowed the avatars of the imagination and the past to form a portal, a foothold, a path forward into the new day …

—Daniel Halpern, author of “ Mating Tango ”

Helen Garner, Dan Halpern, and Keith Hollaman Recommend

Marilyn Monroe’s hand and footprints outside the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Photo by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0,

This week, we bring you recommendations from three of our issue no. 241 contributors.

Twenty-two years late I picked up Blonde, Joyce Carol Oates’s enormous novel about Marilyn Monroe. At first it jolted me with its jangling, sick vulgarity. My pulse rate shot up. I was trembling. I wanted to throw it across the room. But I also had to acknowledge immediately that it was brilliant. Three days later I dragged myself out the other end, shaken by a sort of angst and awestruck by Oates’s manic power, her huge imagination, her ability to command great cataracts of material—to convey a soul mortally wounded in childhood, laboring in its squalor to recreate itself.

—Helen Garner, interviewed in “The Art of Fiction No. 255”

I first read Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude in my family’s summer cottage on Doolittle Lake in Norfolk, Connecticut: an A-frame constructed in the thirties as an afternoon teahouse, with beautiful interior wooden beams and an immense rock slab capping the chimney. An occasional mouse, of course, would seek shelter in the loft spaces, but that August I started to hear a constant grinding noise at night that was not very mouselike. I tried to determine the source of this pesky sound, with no luck. Then one day, as I was completely locked into the last few pages of Márquez’s book—when “all the ants in the world” are “dragging toward their holes” the “dry and bloated bag of skin” of a dead baby with the tail of a pig—the heavens broke open inside our cabin. A panel of insulation had collapsed from the weight of sawdust created by a colony of carpenter ants gnawing into the rafters. I jumped up from my chair in shock and terror, madly brushing them off, gasping from the physical and emotional reality of the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude—this was magical realism at its best.

—Keith Hollaman, author of “Dark Suit and Bow Tie”

Three-part insomnia: I awake at 4 A.M. with a divided mind anchored to the word snake. How it is the perfect representation for the reptile it embodies—starting with the apprising sibilant, then quickly moving off the page by way of a speedy quartet of letters. A lightning-strike piece of diction. Like calling out fire in a crowded space. But while snake is an auditory slither, fire is a fist. That is the first of my early morning’s non sequiturs.

Then I think about my current reread of The Age of Innocence, a nearly perfect novel (Wharton is a kinder, American Flaubert), and of the canniness of Wharton’s depiction of May, who is the true archer, the personage of the bull’s-eye and the off-stage orchestrator of her novel. I find it challenging to understand why Newland Archer doesn’t climb the five flights of stairs to Ellen’s apartment, where he would have found the woman of his true passion—and handily displaced the Frenchman. It’s worth reading the last chapter again for the subtleties planted there: “Perhaps she too had kept her memory of him as something apart; but if she had, it must have been like a relic in a small dim chapel, where there was not time to pray every day.”

And before rising for the day, as the rising sun, I let the memory of Wu Tianming’s 1996 movie The King of Masks come back into focus. I see the many faces of a man who, at the end of his life, wants a grandson to continue the art of mask opera and ends up with something equally beautiful that he could not have imagined, in whatever guise. I might have been dreaming of my daughter earlier. I might have allowed the avatars of the imagination and the past to form a portal, a foothold, a path forward into the new day …

—Daniel Halpern, author of “ Mating Tango ”

September 15, 2022

The Entangled Life: On Nancy Lemann

Photograph by Sophie Haigney.

In our new Fall issue, no. 241, we published Nancy Lemann’s “Diary of Remorse.” To mark the occasion, we asked writers to reflect on Lemann’s remarkable literary career.

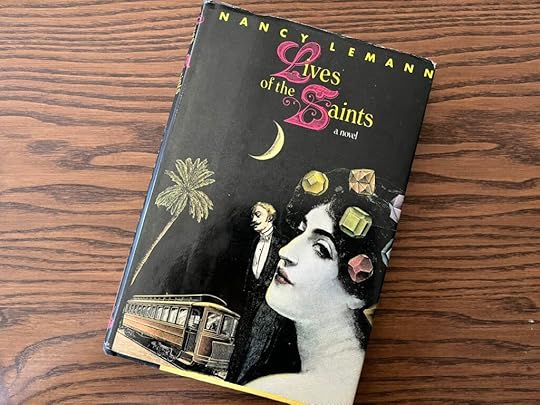

I picked up Nancy Lemann’s Lives of the Saints from a sidewalk pile in Greenpoint in October 2020, just a few minutes before it started raining in sheets. I read the novel in one sitting when I got home. The next day, I lent it to a friend with whom I was crashing for a few weeks. She returned it twenty-two months later, at the beach. Before we even left Fort Tilden I found myself lending it out to another friend. I’m not very generous with books, to be honest, but for some reason, this novel, like an early-aughts chain email, demands to be forwarded. It is a short book, which makes it a good loan to a friend, because you can jointly anticipate a sense of accomplishment. And it may then become a field guide to certain shared experiences of Youth—allowing you both to observe, for instance, on a summer night when everyone around you is having Breakdowns, that this is exactly like Lives of the Saints.

Why had I read it in one afternoon, though? I remembered feeling warm, somehow, like I’d been drinking hot chocolate; that was something I also hoped to pass on to my friends. But I’d forgotten precisely how the sensation arose out of the book’s setting: decadent, upper-crust New Orleans, where desultory people young and old drink heroic quantities of gin, embark on doomed marriages and affairs, and generally go to seed. As I revisited my (second) copy of Lives of the Saints, I realized what appealed to me so much, then and now, was the portrait of the thick, interdependent, entangled community within which these eccentrics thrive. The virtues and morals of this Southern hothouse are as lucid as those of Jane Austen’s or George Eliot’s provincial outposts. We learn that Claude, the narrator’s clumsy love interest, is not only “kind” and “honorable” but also likes people more the longer he has known them. (Thus, reasons the narrator, she will always have an “edge” on his affections.) Would that we had such a firm theory of every character in our own lives—and their extended families, too! The narrator also knows that Claude’s father has been eating a dozen oysters “at noon in The Pearl” every day for four decades—and that Claude’s great-great-grandfather came to Louisiana from Germany in 1836. The verb tenses that scaffold this fictional world indicate reliable recurrences of a dim, shared past in a nostalgia-soaked present: one aging grandee “always quotes from” a dreaded verse history of the Civil War, and a senescent debutante trots out “the story of the Countless Offers.” And then there’s the bracingly intimate “we,” as in: “We used to hear Henry Laines scream at his girl friends … in the apartment across the garden at night from his house.” And so do we, for the hours we spend in this book.

The aimless narrator’s return to New Orleans after her four years at a northeastern college is a clever device with which to reconstruct this milieu for us outsiders. It is not a world you long to join or one whose passing you lament—a world where Black people serve white “wastrel youth,” where parties are staged unselfconsciously at plantations, where a typical setting of a scene includes “everyone screaming for the black maids, with vivid colors of black maids in white uniforms on the velvet green lawn.” These characters inhabit less a stratum than a caste—one that you can’t help but feel deserved the same ultimate Breakdown as most of its members. But to thread the needle so deftly on such people is the supreme achievement of the novel’s voice: deadpan, hilarious, histrionic, anthropological, fatalistic. Some of the narrator’s lines have rattled around my head for the past two years, like: “I could only love one person. This was my innate principle.” She does not write this off—unlike other sentiments of her youth—with her backward glance, and that seemed, and seems, important to me. Many of us cling to similar credos that can appear, especially in what the narrator might call the cold Yankee North, like relics of a bygone era, but maybe we don’t have to let them go. At least, that’s how I felt rereading this novel, as I once again underlined words I had long ago committed to memory: “I cannot just transfer my affections, for they are carved in stone.”

Krithika Varagur is the author of The Call: Inside the Global Saudi Religious Project and an editor of The Drift.

September 14, 2022

The Pleasure of a Petty Thief: Letters, 1982–83

Hans Georg Berger, Hervé Guibert and Eugène Savitzkaya, New Year’s Eve, Rio nell’Elba, 1984. Courtesy of Semiotext(e).

In 1977, the writers Hervé Guibert and Eugène Savitzkaya began exchanging letters. Though the two rarely met, Guibert became increasingly obsessed with Savitzkaya as they continued writing to each other over the course of a decade. This selection of their messages is the first in our new series featuring correspondence, Letters.

Paris

March 11, 1982

Eugène

a belgian stamp sticks out of my mailbox, what if it’s a letter from Eugène, and anyone could have taken it, between the moment when the mailman delivered it and the moment I return home, cluttered with files and folders and newspapers and a flan that will be delicious but yes it is a letter from Eugène, and it, it risks not being delicious, I ready myself for anything: a letter full of insults, or even worse, a letter that mocks me (yesterday on the telephone I heard the voice of a girl who asked me for a photo of Eugène and I clearly sensed in her sugary and whispering tone a caricature of my affection, my own expectation), first off, the letter is quite thin, and maybe there’s nothing at all inside the envelope, and if someone has stolen the letter that will cause yet another misunderstanding, but delicious your letter is still closed, and that’s why I wait to open it, I even crack open the flan first, and start this beginning of a reply, in case some polite or distant words end up cutting my desire to write you off at the knees, do you realize what’s happening right now, on my end? I’m missing an interlocutor, and I’ve chosen you, perhaps wrongly, to be one … Enough, I open the letter, shielding my eyes.

But no, look, your letter is sweet, so sweet, even if the warnings about your twisted character would like to make me question what you say. I’d love to see you in April when you come, and to take you to Bernard Faucon’s, I told him about you and he’s expecting us, I hope it will be a fun evening.

Don’t feel at all obliged to respond to this letter, I am a bit more confident now, and I’ll wait for you to give a sign that alerts me of your arrival.

Je t’embrasse:

hervé

*

Liège

April 27, 1982

Dear Hervé,

I very much enjoyed Les aventures singulières, texts that I had already, for the most part, read, especially “Le désir d’imitation.” Thank you for sending me your two books. Je t’embrasse.

Eugène

*

April 30, 1982

Eugène

At first, to the touch, I wondered if the thickness of your letter was a flattened-out bomb, or a little present: thank you for the old photograph. Afterward, I wondered if your note meant to humiliate me or make me laugh.* And I examined the date, asking myself if it could be a “vexatious action” (I stole this expression from Brigitte Bardot’s secretary who used it several days ago on the telephone to refuse an interview!) following the probable delivery—and your reaction to my piece about you—of the review. Always I speak of you and always I think of you with much veneration, respect, affection, and love. Did you come to Paris and not contact me or did you not contact me because you didn’t come?

Write me.

Je t’embrasse: hervé

(*Meaning that I almost always have the impression that your words are “living” autographs even before they are words that signify something, or transmit a feeling, that’s what leapt out at me tonight, later on, because I left your letter open on my table, and your note appeared all of a sudden in reverse and visually this inversion, its graphic perfection simultaneous with its illegibility, seemed to project it into the future and like the X-ray of a painting reveal its retro-posthumous character, but maybe you think that’s a little much, and that I’m the one who wants to see inside you, as a correspondent, a creator of autographs …)

As a correspondent I seem to be striving, a bit vainly, to make you fly off the handle …

*

Liège

June 4, 1982

Dear Hervé,

I hope you’ve already forgiven me for standing you up at 11 at the Palace Hotel. I went back to Belgium last night, slightly ill. We will undoubtedly have another chance to see each other.

Sincerely

Eugène

*

June 8, 1982

Dear Eugène

i was thinking just now that i was really hurt not to have had any news from you. I would like to know, quite simply, how you are, if you’re working right now, and on what, are you still writing from Faucon’s photos? I read in Munich, where I went on vacation, Un jeune homme trop gros, which I made the mistake of not wanting to read when it came out because of a stupid aversion to the character and the title. I was ashamed while reading it of having run the risk of dying without knowing this book, which is really very beautiful.

And so I await something from you, letter or book, or letter and book, which would be even better!

Je t’embrasse:

hervé

(P.S. If you don’t dare write me, out of embarrassment or a lack of desire to respond to my “letter” that appeared in the review, you would be very wrong, that isn’t at all what I expect from you: in reality nothing specific, but definitely something …)

*

July 18, 1982

Dear Eugène

i read yesterday, while standing up in a bookstore, and with the pleasure of a petty thief, the love of Évoé [Savitzkaya’s novel La disparition de maman]. I think your persistent and almost hurtful silence confirms your twisted character …

Je t’embrasse:

hervé

*

Liège

September 28, 1982

Dear Hervé,

Many thanks for your book, which I’ve started reading with great emotion (up until page 37, line 21).

I’ve been paralyzed by an enormous torpor all summer, to the point that I’ve written practically nothing. Nothing devious in my silence, in my apathy. Your letter in Minuit overwhelmed me and tore up my nerves. I cut my hair because it was infested with lice.

Je t’embrasse.

Eugène

*

Liège

November 4, 1982

Dear Hervé,

I adored your book, Voyage avec deux enfants, and after taking an arbitrary break at page thirtysomething, I read it all in one go. Thank you. Je t’embrasse.

Eugène

*

Paris

December 6, 1982

Dear Eugène

on the eve of a departure, and after a certain silence, between two aphorisms of Marcus Aurelius, would you permit me to foment an impetuous vow: that one day you come to Paris to see me, or to see someone else in secret, but that you stay with me, that you sleep in my bed, that you wash yourself with my soap, that you sit in my chair like the heroine in that familiar fairy tale that I can’t remember exactly, who leaves her little trace behind in a house of giants? (not that I take myself for a giant), do you know that story? but you, maybe you’re thinking: who cares, or maybe all of this turns you off. I’ve placed your second-to-last little letter, precious, on the hearth in my bedroom, amidst the dried flowers and against the shrunken face of an ex-voto Napolitan. I bought a cabinet to store your other letters, which are very thin, so thin that one might think the envelopes were empty: they rest against each other on the second bolt of one of the ten flat drawers of that antique paint box, a completely impractical piece that takes up lots of space and holds nothing, well, not nothing, since it holds you. Je t’embrasse, Eugène, I hope that this gratuitous letter will distract you a bit. Write me.

hervé

*

Paris

February 8, 1983

Dear Eugène,

yet another letter into the void, yet another gratuitous letter, why do you neglect me so? I imagine you’ve nailed my letters to a board in the town square to expose me, and my tenacious and ridiculous affection, as a laughingstock.

I think of you so often, especially when I pass by a shop full of stuffed toys: whenever they have a nice-looking teddy bear or a sweet little rabbit, I think of buying one and sending it to you in a shoebox, I don’t even know if it’s out of rancor or laziness that I don’t ever do it.

Kissing your beautiful cheeks:

hervé

*

Paris

February 15, 1983

Dear Eugène

you see: I am prompt, to respond to you, too prompt, certainly for I know you will sense in that eagerness something menacing, paralyzing, in short a good excuse to play deaf for several months. Recognizing your handwriting on an envelope, standing in front of my mailbox, with a wet head, in this frigid corridor (it’s snowing outside) makes me physically tremble: as if I were receiving a summons to appear in front of an athletic or disciplinary committee, a tribunal, as if I would find in it a censure, or a gluey prank, something that could cut off my fingers or paste them together. I wonder if cutting one side of the envelope clumsily with my index finger would be a heretical thing to do. I continue to tremble and flip between the two images, in search of a little note, and I tremble again finding nothing between them but space, reckoning that you may have sent me two pictures, which I couldn’t even see since they seemed opaque to me: which I couldn’t see as images, as illustrative and charming vignettes as long as I sought to find in them a message, to detect in them some sign of admonishment or flattery. But on the back of one of them I find your writing: thank God. At first it is very difficult to read, so I devour it blindly, from top to bottom, across, until I can steal a a bit of sweetness—and there is always a little bit, thank you Eugène—to appease me and I carry it with me all the way to to the boulangerie where I buy a croissant and to the barstool in the café where I drink, alone, amidst the vile stench of garlic, a black coffee. Now I’ve returned home, with no time to write you, but I’m writing you nonetheless. You will undoubtedly be the person, in the end, in time, to whom I will have written the most: perhaps this is a senseless fidelity, but I hold to it.

Coincidentally, the day before yesterday, because I have to do an interview with a writer whom I like very much (less than you), I reread a little bit of our interview, and I thought it was really nice, funny almost, and I felt a sense of contentment that was quite strong—to have done it with you, and that it had been written down, preserved somewhere.

I think of you often: you know that I live alone, and quite depressingly so, and I have lots of time, in between or during two everyday gestures, to have loving thoughts: I obviously don’t have a purely amorous feeling for you, since that would be crazy, but an affection whose reality sometime verges on irreality, and that gives me a sense of well-being.

I liked the two pictures very much, and in one of them I recognized myself in a way that I’ve never recognized myself in an image before; I don’t know if you did it on purpose or not but either way the attention really touched me. I love your letters that say so little and that are so present, like letters someone writes in the country, I imagine, to one’s family. I’ll stop here even though I still have lots of things to tell you, because you’re right, a letter shouldn’t be too long.

Je t’embrasse, Eugène, so affectionately:

hervé

*

Paris

February 27, 1983

Dear Eugène,

a young girl is waiting at the door and says that she’s come at your request. She’s lying: when she sees your photograph she admits she’s never spoken to you. But she sees you often, at the Winter Circus, and I have a vision of you sitting on a red banquette, or on a wooden bench, in the stench of sawdust and urine, near the wild animals. But she soon explains that the Winter Circus is the name of a café, and she describes you as being always wrapped up in very heavy coats and adds: he must be really thin under all those layers, and I reply: yes, he must be really thin, in a tone I try so hard to make sound innocent that it must sound suspicious: no trace of boastfulness with this young girl, just irritated embarrassment. She leaves, saying to me: “When I see him again, I’ll tell him that I came here,” and I tell her: “Oh, he probably won’t respond well to that,” and she says, “Then I’ll be sad.” The young girl is charming, but it’s crazy how much I don’t like girls, she’s shown me that. Maybe you like them more than me. I like girls like you, that’s all. I’m writing you, my dear Eugène, not to tell you all that nonsense, but to tell you I feel sick, my eyelid twitches constantly as soon as I wake up, it has for ten days, it’s truly horrifying, and in the absence of your lips that could perhaps tame it a bit, that poor eyelid, a little word from you would be like a bouquet of flowers that you’d bring—and you’d be so very kind—to an unhappy acquaintance lying in a hospital bed. I’m not there yet.

Je t’embrasse:

hervé

*

Liège

March 15, 1983

Dear Hervé,

I hereby delegate a little bird that I charge with taming your rebellious eyelid, but perhaps it has already calmed down? He will hover over you while you sleep and be vigilant. I hope that you’re not in a hospital bed and that you’re better. A curious miracle has happened to me: my hair has begun to curl. I’ll end up resembling you.

Je t’embrasse

Eugène

Translated by Christine Pichini.

Hervé Guibert (1955–1991) was a writer, a photographer, a filmmaker, and a photography critic for Le Monde. In 1984 he and Patrice Chéreau were awarded a César for best screenplay for L’homme blessé. Shortly before his death from AIDS, he completed La pudeur ou l’impudeur, a video work that chronicles the last days of his life.

Eugène Savitzkaya is a poet, playwright, essayist, and novelist who was born in Saint-Nicolas, Belgium, in 1955. His poetry collections include Les couleurs de boucherie and Bufo bufo bufo.

These letters are excerpted from Letters to Eugène, which will be published by Semiotext(e) on October 25, 2022.

September 13, 2022

Other People’s Partings

Fall River, Massachusetts. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound.

His last sip of champagne. The whole thing about the popping of the cork, I forget what exactly. The enigmatic words he likely never said: Has the sailor left? But wouldn’t it be wonderful if he had said them? What sailor? Where’d he go?

His wife, the actress Olga Knipper, wrote that a huge black moth careened around the room crashing into light bulbs as he took his final breaths. Olga was present in the room, of course, but I don’t think she was above creating myths, either. They had only so little time together, less than five years.

In 2018, a team of scientists examined the proteins in the bloodstains on Chekhov’s nightshirt, in an effort to determine the precise cause of death. The shirt had been preserved as a relic.

This morning I’ve been wandering through Gustaw Herling’s Journal Written at Night, a book that took thirty years to finish and that consists of essays and fragments that read like private messages. Herling was a member of the Polish resistance who was sentenced, by the Soviets, to hard labor in a prison camp near the Arctic Ocean. The reason? The Soviets didn’t like his name. Herling, in Russian, sounded too much like Göring, as in Hermann. After his release, he spent much of the rest of his life in Italy. In a brief paragraph on the death of Chekhov, Herling includes a detail I don’t remember having come across before. Herling says that in June 1904, just after Chekhov and Olga arrived in Badenweiler, Chekhov insisted they change hotels because he wanted a room with a balcony. They found another hotel. Nobody ever mentions the balcony. Or that Chekhov must have spent hours sitting out there, watching people go in and out of the post office across the street. Till the end, he worked. Imagine him studying each face, what he could see of them from up there, every gesture.

***

In chapter nine of Shirley Hazzard’s The Evening of the Holiday, Luisa, a graceful matriarch and an otherwise kind and generous person, has this thought about two people in love:

One would always think of oneself as being on the side of love, ready to recognize it and wish it well—but, when confronted with it in others, one so often resented it, questioned its true nature … Was it merely jealousy, or a reluctance to admit so noble and enviable a sentiment in anyone but oneself?

Luisa is having lunch with Sophie, her niece, and Tancredi, an old friend. Sophie is visiting Italy from England. Tancredi is allegedly an architect, though he never seems to have to go to work. These two have only recently fallen hard for each other and are so overcome they can hardly contain themselves. Luisa adores her niece, and Tancredi, well, he’s practically part of the family, too. Of course, there are complications. Aren’t there always? Tancredi’s married (separated) and there are two children—or is it three? I forget. They’re hardly mentioned. Anyway, why not be happy that these two are happy? Why not simply wish lovers well? Look at them. Deep in that period when everything, including time itself, is weightless. Why? We know why. Because new love is always a little repulsive to the rest of us. Unless—need it be said?—we’re one of the two. To be a third at a table with lovers in the beginning throes is a special hell, as intolerable as it is annoying. Any third exists, if at all, only on the periphery. Luisa is sitting at her own table and she’s nowhere. And the fact that Sophie and Tancredi are trying so desperately to concentrate on Luisa only makes it worse. The only respite is the storm that’s begun to wail outside. It gives Luisa something else to think about. The garden, imagine all the destruction taking place in the garden.

Does Luisa take pleasure in the fact that she knows it won’t last? That soon enough Sophie and Tancredi will be knocked off their ecstatic perch, just as, outside in the garden, the urns are currently being blown off their pedestals? Do I take pleasure in it? Every patient sentence in this short burst of a novel brings us closer to the end of these two, of this time that isn’t time. Maybe all readers are Luisa. All of us onlookers experiencing the passion at a remove.

***

If the things we put in parenthesis might be described as the things we can’t help but say (no matter how much they distract) then I wonder if all sentences shouldn’t be in parentheses. From a moment in Tomas Tranströmer’s poem “Baltics,” about his grandparents:

(We’re walking together. She’s been dead for thirty years.)

What is it about prose, especially my own, that’s begun to feel so leaden? And what it is about a line of poetry that’s like the fleet bite of a mosquito? That imperceptible surgical injection of the proboscis, in, out, finished—

(We’re walking together. She’s been

My eyes, as so often happens, wander off. The grief that’s called to the surface by someone else’s words. She used to wait for me when I’d drive down to Fall River those years I lived in Boston. I’d climb over the railing and come in through the sliding door without knocking. The sweet, pungent smell of that little apartment, a kind of sugary rot, and she’d rise from the couch happy to see me but at the same time pissed off at how late I am again. What, do I think do you think I have nothing better to do than lounge around the house and wait for you all day? Do you know how many plans I canceled? How many of these shriekers and pouters I’ve had to put off so I could be available—and how these contradictory reactions didn’t cancel each other out but instead merged into a begrudging relief that I’d made it down here alive again. Help yourself to the half sandwich in the fridge, it’s tuna from Newport Creamery. Pretty good! And there are some of those shoestring potato chips you like.

We didn’t walk, we drove. All over Fall River. To the dressmaker, to the pharmacy, to the podiatrist. To the Chinese restaurant in the mall out by Airport Road. Even to the pool at her complex, which was just down the hill. We’d get in her Plymouth Sundance and drive. At the pool was a social club. She wouldn’t talk to her friends when I was with her. She could be haughty. I’d do laps in the little pool as best I could. She’d sit on the deck and read Anne Tyler. She said, Anne Tyler can tell a story. When was I going to learn to tell a story?

So you’ve met someone?

What makes you say that?

Maybe the clean shirt.

It’s that clean?

Wishful looking.

She volunteered in the hospital gift shop, a job she liked. She liked to bring a little joy to people. I sell some chocolate, a stuffed animal, she’d say. You’d think it wouldn’t mean much. When it was time for me to leave her, she’d hand me my hat. Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?

When I didn’t have a hat, she handed me one of hers. Here’s your hat …

In March of her last year, my mother brought her out to Chicago from Fall River. She was seventy-eight. (My mother went on paying the rent for her apartment even though we all knew she’d never make it back to Massachusetts.) She died in Chicago, a foreign city, at Rush Presbyterian–St. Luke’s in June 1995.

***

A Garielle Lutz story. It doesn’t take up a whole page. Like a tiny fortress. I’ve read it eleven times this morning. A dead sister’s phone number. Her brother keeps calling it, again and again. This was back when we punched in phone numbers, each and every time, punched in the numbers. Lutz compares the muscle memory of that repetition to haiku. What’s irrecoverable made tangible by the movement of fingers alone.

I mean, there was something physical about the way I kept ringing her up—

I’ve got my own numbers that no longer—

432-5181. 432-4474. 432-8719.

***

I’m reading on the porch of a rented house in the north end of Burlington. My mother is upstairs in a small bedroom, in a narrow bed, trying to sleep. Now she sleeps late. She never used to. Grief has tired her like few things ever have.

It’s after ten in June. The Air National Guard is flying training missions over Lake Champlain. These sleek black planes, their sonic boomings.

The house is across the street from a cemetery. Mismatched stones crowd the hillside. Pike, Dumas, Kane, McAuliffe, Dattilo, Greenough. Yesterday, wandering around up there, I came across blankets and a camping mattress unfurled at the foot of a grave. On the branch of a nearby tree hung a sweatshirt.

I’m three-quarters of the way through Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Beginning of Spring, past the point where the swath of pages I’ve read is thicker than what’s left. There’s a metaphor in my hand.

A family of British expatriates in Moscow before the revolution. In the opening sentence we learn that Frank’s wife, Nellie, has left him. She takes the children with her on a train heading west, but then changes her mind. During a stopover, Nellie sends the kids back to Moscow, back to Frank. In the second chapter, Frank arrives at the station to retrieve them. Fitzgerald describes the people Frank sees waiting around: “lost souls who haunt stations and hospitals in the hope of acquiring some purpose of their own in the presence of so much urgent business, other people’s partings, reunions, sickness and death.”

I’m thinking about other people’s partings when the front door slaps open and my mother, fully dressed and wearing sunglasses and a baseball hat, charges past me, off the porch, and onto the sidewalk, shouting at the sky, at all that deafening noise, What the hell’s happening?

Peter Orner is the author of seven books, including Am I Alone Here?, Maggie Brown & Others, and Love and Shame and Love. He directs the creative writing program at Dartmouth College. This piece is adapted from Still No Word from You: Notes in the Margin, which will be published by Catapult on October 11.September 9, 2022

Ben Lerner, Diane Seuss, and Ange Mlinko Recommend

Claude Monet, The Beach at Trouville, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

This week, we bring you recommendations from three of our issue no. 241 poetry contributors.

This August I read three great books. In Anahid Nersessian’s Keats’s Odes: A Lover’s Discourse (about to be reprinted by Verso), red life streams again through Keats’s poems. It is a risky, passionate criticism that—in addition to yielding all sorts of insights into the man and his writing—tests what of her own life the poems might hold (and quicken). This is living in and through and with and against poetry, a brilliant and refreshingly unprofessional book. I’ve also been reading and admiring Elisa Tamarkin’s Apropos of Something: A History of Irrelevance and Relevance, a beautifully written account of the development of the concept of “relevance” in nineteenth-century Anglo American thought and art. The book says almost nothing about our own century—“the Internet,” for instance, doesn’t appear in the index—but that just makes its relevance to the present more acutely felt. Tamarkin has all sorts of insightful things to say about attention and “attentional communities,” which leads me to a final recommendation: the big strange wonderful In Search of the Third Bird, which describes itself as “the real history”—although much of it is quite fake—“of the covey of attention-artists who call themselves ‘the Birds,’ ” an actual group (or “attentional cult”) of scholars and artists who have been conducting experiments in sustained, collective attention. That James Tate line occurs to me: “Everything is relevant. I call it loving.”

—Ben Lerner, author of “The Readers”

I read selectively, so as not to flood myself, especially when I am generating my own poems, which is always. Part of me is a cold observer. The other part, an impressionable child. Either way, what I read reconfigures me, as do all things that I take in through the senses. During a recent drive to my hometown of Niles, Michigan, I was transformed by a cream-colored ox, a stone silo, and an assertive stalk of goldenrod reaching from a ditch. The poems in David Baker’s newest collection, Whale Fall, move me similarly, and deeply. It strikes me that the purpose of craftedness, of exquisite and intentional madeness, is to create a kind of eternity in a poem. Maybe such a goal, at this point in history, seems unreachable, even Romantic, in the literary sense. But let us aim for eternity anyway. “Keep walking, pilgrim,” Baker writes. “This is your great tale.” (The poem is called “Extinction.”) A collection of poems can be scattershot; it can reflect the fragmentation of our times. Or it can build something in defiance of chaos: a structure the reader can live within, while taking time to examine its architectural nuance (even as a silo burns on the horizon “with the half-life of the sun”). The craft of Whale Fall defies. It asserts, for me, a definition of poetry: an unbearable gulf of feeling made indelible by form.

—Diane Seuss, author of “Legacy”

As I say farewell to summer, I look back at a painting I saw at the National Gallery in London in June. It is Monet’s The Beach at Trouville, painted in plein air in 1870 on his honeymoon. The placard notes that sand and bits of shell are embedded in its surface, authenticating it with local grit—so different from our own time-stamped, etherized photos!

—Ange Mlinko, author of “Art Tourism”

September 8, 2022

Free Dirt

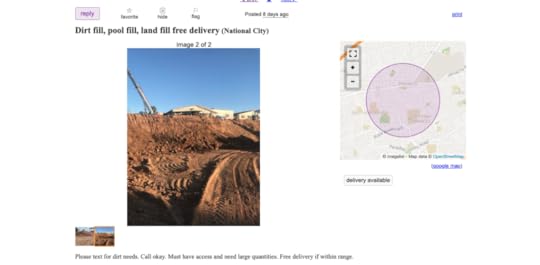

Free dirt. Photograph via Craigslist.

For the past three years, I’ve filled a folder on my desktop with pictures of dirt that I found on Craigslist. The dirt in each picture was offered free of charge to whoever was willing to pick it up (“You haul”) or, if you were lucky, a free-dirter might have offered free delivery. Depending on the angle and composition of the images, “free dirt” posts on Craigslist can look like unintentional landscape vistas. Some shots feature calloused hands covered in tawny fill dirt, vignetted by palm trees and paved driveways in postwar cul-de-sacs. There are endless frames of earth spilling onto asphalt, flattened mounds of rich brown soil indented with tire tracks, craggy piles of dirt gathered evenly along the perimeters of blue tarp in driveways. Where I’m from, in Southern California, free dirt is abundant.

Dirt moves and circulates as part of its role in the man-made ecosystem of building, demolishing, and rebuilding. But there’s a paradox: the more that dirt is touched and handled by human hands, the more expensive it becomes to move around. If you bring “non-native” soil to a construction project, you are subject to costly soils testing. When a project has tight specifications—public libraries, for instance, have highly regulated dimensions and measurements—leftover dirt becomes surplus material. And you can’t simply throw it out. Disposing of dirt in Southern California is a long, bureaucratic process, one San Diego landscaper told me; one must apply for a permit to dump excess dirt and must transport it in a vehicle of a particular class. Some construction companies have even turned to posting their excess soil inventories online via dirt-matching sites. (“Connecting people who have dirt with people who need dirt,” reads the ad copy on DirtMatch.com. They boast 5,914 matches in the last ninety days.) For the homeowner who just wants to build up the ground around their new in-ground pool or the young couple working on the raised beds in their vegetable garden, all of this is expensive and time-consuming. And so they turn to Craigslist, and to the world of free dirt.

A free-dirt listing on Craigslist.

The language in these online ads is friendly; the soil identification is anecdotal. “Fill,” or nutrient-poor excess dirt, is most abundant and available online because it’s surfeit junk—the petty cash of land use. “This was dug up from our backyard when redoing our lawn,” reads a recent post from Rancho Bernardo, alongside a photo of a medium-size pile of brown dirt and the neon-green handle of a shovel. “I don’t have a truck so you will have to pick up but I can give a helping hand to load the dirt.” It’s nothing fancy, even in the world of dirt.

Free dirt. Photograph via Craigslist.