The Paris Review's Blog, page 74

September 6, 2022

For the Record, the Review Has Not Abolished Fiction

Subject: Inquiry about a small change beginning with issue 238

Dear Emily,

Volume 238 dropped the fiction and nonfiction labels previously attached to prose pieces. I found no rationale for the decision in your editor’s note to that edition, although your reference to “fiction or nonfiction or something in between” may be an allusion to an answer I am not sophisticated enough to understand. Why has The Paris Review dropped the fiction and nonfiction labels? Were the labels always included in past editions (I’ve only been subscribing since 2019)? I ask because perhaps my need to categorize a piece of writing before I begin reading is telling of something about me that I’ve never considered before. And granted some fiction is obviously so and could not be understood to be otherwise, but when I read on page 187 of your latest that “It’s 4:38 P.M., eight minutes after I usually go home, but now I’m rooting around under my chair cushion …” I want to know, was this ever true?

Thank you for your time,

Walter

Yellowknife, NT

Canada

p.s. I love what you’ve done with The Paris Review in terms of its physicality. The writing continues to awe (for example, the Sterling Holywhitemountain piece was brilliant).

Dear Walter,

Thank you so much for your email, which is beautifully written and generous, and which also gave me the tiniest flash of dread. The decision to alter the table of contents was one we made a year ago, in the thick of redesigning the Review and putting together our first issue as a new editorial staff—and I confess, I’d been rather hoping we had gotten away with it. I’ve even asked myself once or twice whether we were unduly influenced by the elegant, minimalist covers of the seventies, from which we adapted our new tagline: “Prose Interviews Poetry Art.” (Catchier, we thought, than “Fiction Nonfiction Interviews Poetry Art,” or “Fiction Nonfiction Drama Interviews Poetry Art” …) On balance, though, I’m grateful for this opportunity to explain myself to you, and to anyone else who’s been wondering what we’re playing at.

For the record, the Review has not abolished fiction. Nor do we doubt its existence: we still publish more of it than of anything else, and we care about it a great deal. And, of course, we work hard behind the scenes—editing all our stories in conversation with their authors—to ensure that each piece adheres to the rules that best serve the writer’s intentions as well as the needs of readers. (We also fact-check everything we publish, including poetry, to differing levels of stringency—a vital process that produces occasional moments of absurdity.) That kind of work would be indispensable regardless of the broad categories of fiction and nonfiction: different conventions apply to reportage than to memoir, for instance, or to letters and diaries, which might be filled with half truths no one would want to expunge.

Last year, we found ourselves discussing the effects—some helpful, others less so—of categorizing prose by its degree of veracity. After all, no equivalent warning labels are necessary in the case of “Poetry” (or “Art,” for that matter). A poem is defined primarily not by the accuracy of its contents but by its language and form. That’s not to say that it’s unimportant whether a poem is autobiographical, or responding to real events. But—notwithstanding any hints a title or a dedication may offer—readers must usually figure out a poem the old-fashioned way: by reading it.

Many publications have good reasons to prepare readers for what they are about to receive—but the Review is not like most other publications. We are fortunate in not having to respond to the news or the debates of the day according to any prescribed formula, and that is a freedom we wanted to try extending to our readers. In cases where the absence of categories seems likely to sow unhelpful confusion, we will offer the reader a clue, in a subheading or an explanatory note (and online, too, for those who feel the urge to do some extra research)—but we try not to dictate the terms of your encounter with a piece of writing in advance. Where possible, we’d rather leave you alone, at least at first, with the consciousness you’re meeting on the page. Reading is, in my own experience, one of the most intimate acts we have. And isn’t real intimacy always a little destabilizing?

At the risk of sounding like someone who never got over I. A. Richards, I believe that the writing we publish will teach its readers how to interpret it. The example you give—“Lording” by Matthew Shen Goodman—is a good one. The piece does have an almost documentary quality. By the end of that first page, the reader might even suspect the benzodiazepine-addicted speaker of showing off—of wearily dropping those “PHQ-9s” and “LCSW”s as evidence of his unrivaled access to the gritty world of a Brooklyn housing facility. Like you, I still wonder whether any of the events “Lording” describes were ever true—whether Goodman ever worked as a social worker, or whether he, like Elliot, had a friend whose story he decided to turn into a work of art. Knowing that “Lording” is fiction hasn’t helped me answer these questions, and grappling with them is part of what the story asks of me.

Then there are certain pieces that particularly benefit from letting readers feel their own way through. I didn’t know, on first reading a rough translation of Christian Kracht’s Eurotrash, from which “The Gold Coast” in our Fall issue (out tomorrow!) is adapted, whether it was fiction or memoir—but by the time I had finished reading, I understood that its narrator was reveling in that ambiguity. The uncertainty sharpened my discomfort and enjoyment alike.

I want to make it clear that this decision was and is an experiment; we hereby reserve the right to invent new categories of prose for future issues—“Inaccurate Recollections,” perhaps, or “Ghostwriting.” Whatever label it may fall under, we aspire always to publish prose that rewards your closest attention.

Emily Stokes

Editor

Custody

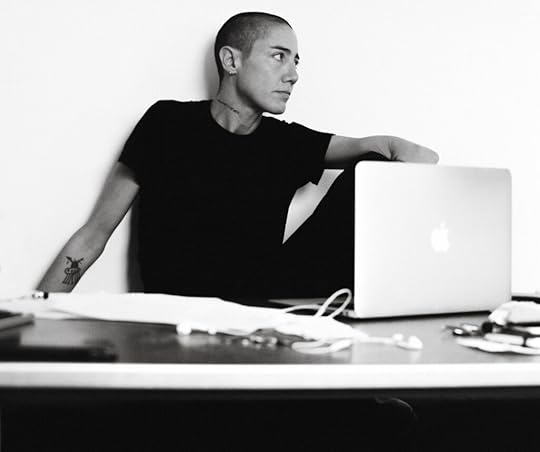

Constance Debré. Photograph by Adam Peter Johnson. Courtesy of Flammarion.

Three years ago. We’re at the Flore, sitting outside, rue Saint-Benoît. It’s summer. I’m dipping my black-pepper potato chips in some ketchup. I’ve ordered a club sandwich, he’s having a croque monsieur. He’s my ex. The first man I was with, and until further notice, the last. We’re actually still married because we never got a divorce. We lasted twenty years, he and I. It’s been three years since I left him. His name is Laurent. With our eight-year-old son, with Paul, we do alternate weeks, all civil, we’ve never had any problems. A few months ago I switched to girls. That’s what I want to tell him. That’s the point of this dinner. I picked the Flore out of habit. We met here when we were twenty, it became one of our haunts. I grew up here, I’ve never really lived anywhere else. But I don’t go to the Flore anymore. I quit my job as a lawyer, I’m writing a book, I’ve got the tax people on my back and no cash to my name. It’s a pain, obviously, but it’s not important. So I spit it out, I say, I’ve started seeing girls. Just in case there was any doubt in his mind, with the new short hair, the new tattoos, the look in general. It’s basically the same as before, obviously just a bit more distinct. It’s not as if he never had his doubts. We had a little chat about it, a good ten years ago. I said, Nope, no idea what you’re talking about. I mean I’m dating girls, I say to him now. Fucking girls would be more accurate. He says, All I want is for you to be happy. This, I don’t reply, sounds like a lie but it suits me fine. He’s barely touched his croque monsieur, he lights a cigarette, calls the waiter over, orders more champagne. That’s what he’s drinking these days, he says it agrees with him, that it makes him feel less shitty in the morning. The check comes, he pays, we leave. Instead of going his own way on le boulevard Saint-Germain, he walks me towards the Seine. When we get to my door, he goes to follow me upstairs, as if we hadn’t been separated for three years, as if I hadn’t just told him what I’d just told him. I say no. He says, Have it your way.

The next day he messages me, Yesterday was nice what are you doing tonight? I thought we’d settled things but maybe he’s thought about it and wants to talk some more. We’ve hardly seen each other in three years, I liked it just fine that way. But I agree to meet him, I tell myself I probably owe him that much. He comes to pick me up outside my house in a taxi, it looks like he’s made an effort, he’s made reservations at a restaurant in another district, a fairly chic place in the courtyard of an hôtel particulier. He talks to the waiters like a regular, he orders a good wine like a connoisseur, he acts like some guy trying to impress his girlfriend. Maybe this is what he does now with girls, maybe he wants to show me, try out his techniques. He wanted to meet but he’s not saying anything, he’s not asking any questions, not a word about yesterday, nothing about him or me, we talk about holidays, foreign countries, books we’ve read, as though we’re politely humoring each other on a date that’s not going anywhere. He wants us to walk home together, I make sure there’s enough space between our bodies, not too close, not too far, as if everything were normal. The Marais, the Seine, the Notre Dame, we’re like a couple on honeymoon. Once again he walks me right to my door, once again he wants to come up with me, to kiss me, once again he seems surprised when I say no.

In October, I bring up the subject of divorce. There’s a girl I’ve been seeing since summer. She’s young, she doesn’t like the fact that I’m married. She’s been on my case, she keeps making scenes, in the end I give in. And she’s right, it isn’t healthy, I call him my ex, he still calls me his wife. I invite Laurent for coffee, one day, then another day, he says he doesn’t have time, he’s avoiding me. In the end I send him an email. I want to get divorced, it’d make things clearer for everyone, come over for dinner one night and we can talk, take care. Stop you’re turning me on. That’s his reply, which he sends in an email. In the moment, I find it funny. A little crazy, but funny.

Fifteen days later, around Halloween, he tells me something’s up with Paul. He says he’s keeping him, that there’s no need for me to pick him up. He says Paul can’t stand me, that he’s rolling around on the floor, that he hates me. I go over. My son is rolling around on the floor. He hates me. At this point, I don’t make any connection between the facts, between the father and the son. Maybe Laurent’s right, maybe Paul does hate me, maybe it is my fault, maybe I have done something wrong. I try to understand what I’ve done, what I’ve failed to do. I haven’t been giving him as much attention recently, I have to admit. I’ve been there the whole time but I’ve been a little distracted. I’ve been writing my book. You don’t have space for anyone when you’re writing. And then there were the girls. At first, I didn’t say anything to Paul. But in the end, we had a chat. Not right away, not about the first girl, nor the second, but the third girl he met in passing, he liked her. He said, Why don’t we go on holiday with her, that would be nice. But I told him we couldn’t, we’d just broken up, I explained. I asked him whether he’d already suspected something, whether it bothered him. He’d already suspected something, it didn’t bother him. We went out, he took my hand, we went to get a soda at La Palette downstairs, we were both in a good mood, we often were, come to think of it. We carried on as before. There were the weeks where he stayed with me and I took care of him, then there were the weeks where he stayed with his dad and I took care of the girls. I was always careful. Everything was going well. I know it was. Some things you just know.

Since November, Paul’s been staying with his dad, I don’t see him anymore, I don’t speak to him anymore. Every time I propose something, Laurent either refuses or doesn’t reply. Nothing, no news, not a word. The weeks go by, then the weeks turn into months. I don’t threaten to take him to court, I don’t want to make things worse. One day, when I’m feeling fed up, more so than usual, I go over to his, to theirs. Laurent opens up, doesn’t say a word, goes to the living room. Paul’s in his bed, duvet pulled over his head, head on the pillow. Laurent’s in the next room, smoking. I speak to Paul but he doesn’t move, doesn’t look at me, doesn’t answer me. I try different tones of voice, I ask him how he is, I try to make him laugh, I talk about something else, I ask him what this is all about, I say, Come on, come and get a Coke downstairs with me, he doesn’t open his eyes, he doesn’t move a muscle, he’s tense, stubborn, heavy as lead. Finally I lose my temper, I yell at him, That’s enough now, get up, get dressed, come with me just for five minutes. He gets out of bed, he goes to his dad in the living room, he hides behind him, he’s shaking and yelling, he tells me to go to hell, he gives me the finger. Laurent points at the door and yells, Now get out. I look at him and realize he’s stronger, physically stronger than me, the fact that we’re the same height, that we wear the same clothes, that we occupy space in the same way, that we speak at the same volume, none of that makes any difference. That’s when I realize that the difference between a man and a woman is just a question of weight and muscles. I look at Laurent and see he’s thinking the same thing, I look at Paul standing behind his dad and see there’s nothing I can do, I tell myself this is between them, their little guy thing, I shrug my shoulders, I leave.

At the local dive bar run by a Chinese family, I tell my friends from the swimming pool what happened. Dominique and Ming say, That’s crazy, you have to do something, speak to Laurent’s parents, go to the police. André says, Leave it, it’ll be all right, your son will come round sooner or later. He says something similar happened with his daughter after his own separation. It all worked out in the end.

Fall comes and goes, then winter, then spring. The whole time I wait for things to settle, I figure they’ll get tired eventually, I try to speak to Laurent, try to see Paul. There’s no getting through, it’s the Berlin Wall. I haven’t seen Paul for six months. A friend of mine, a family lawyer, offers to help me. For free, seeing as I’m broke. When summer comes around, he files for divorce on my behalf with a request for urgent measures to be granted so I can see Paul every other week, just as before. I say to myself, worst-case scenario, I’ll have him for half the school vacation and on weekends, just like any dad who walks out on his family.

The hearing is set for the end of July. One year after the episode at the Flore. Two days before the hearing, I receive Laurent’s written submissions, signed by his lawyer. He’s applying for sole custody with termination of my parental rights. He’s accusing me of incest and pedophilia committed against my eight-year-old son, directly or through involvement of a third party. He’s written about my homosexual friends “who may or may not be pedophiles.” He’s included a picture of my son sitting outside on a terrace with one of my fag friends the day we went to get a soda together, a photo of a sign that reads DANGER! HUNTING that I found in a field and kept on my desk, near Paul’s bedroom door. He’s quoted passages from books selected from my bookshelves, Bataille, Duvert, Guibert. He’s putting everything together, making his case, sowing doubt. My nine-year-old son has written a letter to the court saying that living with me is inhumane, that his dad says I’m insane, and he agrees. He says he doesn’t want to see me anymore.

The hearing lasts fifteen minutes, Laurent’s lawyer reads passages from Crazy for Vincent, as if I were Hervé Guibert’s narrator, as if Paul were the young boy he sleeps with in the book, the judge stares at the tattoo poking out from beneath my sleeve, she asks me why I’m writing a book and what it’s about, she wants to know why I speak to my son about my homosexuality, she says that these subjects are not appropriate for children, that it’s not a question of legality, it’s a question of morals, she’s sure I can understand, I am, after all, an intelligent woman.

The judge’s ruling is issued a few days later. She’s appointed a psychiatrist to examine all three of us. She’s giving him six months to hand in his report. As always when it comes to legal matters, the time frame is just a guideline. It could take a year, two years, three years. In the meantime, Laurent has been granted sole custody. I have only limited, supervised visitation rights, according to the ruling. One hour every fifteen days at an association, a “meeting space” near République, where pedagogical experts will monitor meetings between me and Paul, just like they do for some (but not all) moms on crack or dads who beat their kids. “Unless the parties agree otherwise,” it says. “Until we have a clearer understanding of the situation,” explains Madame C., family judge at the Judicial Court of Paris. I appeal, but it doesn’t halt the proceedings. The decision and its provisional enforcement still apply. There won’t be a hearing for two years. Two years might as well be a thousand years. Two years might as well be never.

Translated by Holly James.

Constance Debré is a writer and former lawyer whose books include Nom and Play Boy. This previously unpublished piece is adapted from Love Me Tender, which will be published in late September 2022 by Semiotext(e) (U.S.) and Tuskar Rock Press (UK).

September 2, 2022

On Cary Grant, Darryl Pinckney, and Whit Stillman

Cary Grant in North by Northwest.

During the COVID confinement and afterward, I watched around sixty films starring Cary Grant. What a comfort to have him in my mind before I slept. No matter if he is comic or desperate, self-possessed or wounded, romantic or cool, he is ridiculously good-looking and seems never to know this. I love it when he puts his hands on his waist and pushes his hips forward as if about to dive or perform some acrobatic trick. His slim, athletic torso and long arms are always tanned. Sometimes he wears a fine shimmering gold medal around his neck. I love his dark eyes that have not forgotten his youthful suffering. He makes me laugh when he rolls his eyes around with his own special brand of sophisticated nonchalance. Though he isn’t aggressive, he doesn’t seem weak either. I find him buoyantly masculine. I can’t resist watching him. A few days ago, on a flight to Los Angeles, I watched Alfred Hitchcock’s hugely entertaining thriller North by Northwest again. Grant was fifty-five when he made this film and long past his box office peak in the screwball comedies that made him famous. In the Hitchcock film he wears a nice-fitting, light gray suit with a gray silk tie and cuff links. The suit gets dirty, sponged off and pressed, then dirty again. Grant’s hair is a little gray, too. I don’t wear ties anymore, but I would wear a tie worn by Cary Grant. North by Northwest appeared in 1959, around the time that he was experimenting with medical LSD and searching for more “peace of mind,” as he called it. I don’t really know what a great actor is, but I think Grant is sensational.

—Henri Cole

Read Henri Cole’s recent essay on James Merrill here.

In a scene midway through Whit Stillman’s Barcelona, which I rewatched this week, the Spanish Marta (played by a not-so-Spanish Mira Sorvino) is explaining to patriotic American naval officer Fred why her friend Montserrat has left his also American cousin, Ted.

Ted’s romantic rival, she says—in close-up, in a possibly Catalan accent—has lectured Montserrat about the ills of American society:

And he painted a terrible picture of what it would be like for her to live the rest of her life in America, with all of its crime, consumerism, and vulgarity. All those loud, badly-dressed, fat people watching their eighty channels of television and visiting shopping malls. The plastic throw-everything-away society with its notorious violence and racism. And finally, the total lack of culture.

“It’s a problem,” agrees Fred.

—Rebecca Panovka

Read Rebecca Panovka’s culture diary, which chronicles a week of June in New York, here.

I usually start my summer by reading Sleepless Nights, mostly because of the opening sentences: “It is June. This is what I have decided to do with my life just now.” My love for reading Elizabeth Hardwick is matched only by my love for reading about Elizabeth Hardwick, so it’s only fitting that I’m finishing the summer reading Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-Seventh Street, Manhattan by Darryl Pinckney. The memoir, which will be released in October, is an impressionistic recollection of Pinckney’s early years as a writer in New York City, when he was fresh out of school and trying to learn who he wanted to be by studying Hardwick, his former professor, as well as Barbara Epstein, his new editor at The New York Review of Books. I especially liked Pinckney’s anecdotes: Hardwick bringing home a cardboard box of what would become Sleepless Nights but was then called “The Cost of Living”; dinners and joints with Hardwick’s daughter Harriet; and nights spent watching the B-52s perform. It’s a portrait of a special phase in many young lives, when our relationships with the people who have the greatest influence on us can feel both fated and random.

—Haley Mlotek

Read Haley Mlotek’s essay on the perils of the month of August

here.

Softball Season

Summer softball. Photograph by Sophie Haigney.

I took over the Paris Review softball team this year because the former captain, Lauren Kane, left the magazine for a big job at The New York Review of Books just before I was hired, and someone noted during my first week that I might be a good replacement because I “like sports” (i.e., I sometimes watch Premier League soccer on weekend mornings). I am not, strictly speaking, an athlete, and had never played a full game of softball; still, wanting to be amenable, I agreed and found myself on the phone intermittently all spring with the New York City Parks Department, trying to get our field permits nailed down. At one point I was arguing with someone about the timing of sunset on a specific day in July.

The list of things I didn’t know about softball when the season began in May is long and comical. Among them: Not every field has bases—if you don’t bring them, you might need to use your shoes as second and third. Turf can be very slippery and you should expect bloody knees and have a first aid kit on hand. The play is often at second, and even more often at first. Pitching badly is sometimes actually preferable to pitching well. You can run through first base but not the other ones. You have to shift over in the field when a lefty is batting. You should not attempt to catch with your bare hands, even if it seems like the ball is coming at you very slowly. Right field is actually kind of a chill place to be, except when it isn’t. It all comes down to the quality of your ringers—and sending people shamelessly pleading emails to get them to show up to your games.

When I arrived to play our first game, against Vanity Fair, I didn’t even know how many outfielders a team required. It was a bleak beginning of the season, pre–Memorial Day; there were only seven of us, most of whom had never played and the rest of whom hadn’t practiced. I had expected a few people hitting around jovially in the summer twilight, and instead we arrived to face a team of guys who were saying things like, “My favorite spring ritual is dusting off my cleats!” One of them got really mad at me over the way I was standing at first base. (I was standing wrong.) We lost 27–1. I was surprisingly demoralized by the experience and wasn’t relishing the concept of forking my summer evenings over to what seemed like the perfectly miserable pastime of taking the subway up to Central Park to get crushed. All in all it seemed like it was going to end up being a raw deal, being softball captain—the kind of thing I would try to foist on someone else next summer. In our second game, we lost 11–3 to The Drift.

Then something happened. On the solstice, we were scheduled to play The New Yorker. It was a Tuesday. My friend Nick and I were having bad weeks for similar reasons, and we got a beer and commiserated about how absolutely feckless we can both be from time to time. Neither of us felt much like going to softball, especially because it looked like it was going to really rain and Nick was wearing his suede shoes. All afternoon I’d been trying to subtly convince the New Yorker captain to cancel the game, but he didn’t, and so we sighed and lugged our crates of mitts and balls up to Ninety-Sixth Street, where we got off the the subway into sheets of driving rain. Surely, then, the game would be canceled; I told people at the office not to bother making the trek. But a smattering of New Yorker players were determined to play, and if there’s one thing Nick and I hate, it’s being seen as cowards. So we went along with it, and the rain let up a bit, and after a while a few of the old guard team members—Jeff Gleaves and Dan Piepenbring and Matt Levin—surprised us by showing up, and so did Adrienne Raphel and Moses Tannenbaum, a star player we’d recruited from the Drift team, and my friend Ben. The New Yorker had at least twenty more people than us, but somehow we put up a good fight, and the final score was 9–6 (arguably 9–7, though it’s probably uncouth to point this out months later).

Something about the rain made the game feel different, higher stakes, and I figured out how to hold the bat properly, which helped. Eventually there was a sunset, and green fireflies rising off the wet steamy grass, and we walked to Tap a Keg after the game was over. We had pizza with the nice New Yorker team, and drank more beers than perhaps we intended to on a Tuesday night before a long subway ride home. Nick’s shoes got ruined. Later he texted me to say that he was “reinvigorated by taking a spin around the diamond,” and I agreed. I felt overwhelming affection for my friend Nick, who is among the kindest people I know, and perhaps my favorite person to spend a summer evening with. He and I decided that despite everything else it was very good to remember what life is all about, which is taking a spin around the diamond with your best friends.

***

The first game we won this summer was against the New York Review of Books in July. We played in East River Park— unusual for us—at a strange but pretty spot squeezed in between the highway and the river. It threatened to thunder but didn’t. Adam Wilson came in a Jerry Garcia Band hat and promptly hit a home run into the water. The sky turned orange and we kept scoring until the moon started rising: 25–12. We went to a funny nearby bar to hide out in the air-conditioning and eat Dominos. Some people stayed and played pool. I was exhilarated.

The season continued. A lot of people came out of the woodwork to play—friends from college who played softball in high school, ex–Paris Review staffers, people with tenuous connections to people who have tenuous connections to the magazine. There were lots of highlights: Everyone showed up to beat Vanity Fair in a rematch. Paris Review softball veteran Josh Pashman drove from upstate to pitch for us many times, and basically whipped the team into shape. After losing to Forbes, we sat around at a beautiful outdoor bar in Riverside Park, foraged through some leftover catering platters, and played my favorite game, dichotomies. (Are you thunder or lightning? New Hampshire or Vermont? Et cetera.) We had a mini batting practice with DC Comics in Central Park on one of the nicest nights of the summer. I started noticing the earlier and earlier onset of darkness, and some changes in the air—it wasn’t any less hot but was less humid, maybe. There were fewer threats of rainstorms. I began to prematurely mourn the end of the season.

What I am describing—coming to like this sport—happened to me for the obvious reasons: the camaraderie, the running around outside on sunny summer evenings, the drinking of beer in parks, the surprise of suddenly caring about winning, the frustration of losing. It’s hard not to get sentimental when writing about softball, probably because of how it aligns with the seasons. When we started playing in May, we were still on the brink of summer. Now, that summer has more or less come to an end. Over the course of it, we did some of the things we planned to do and failed to do others. We went away and came back. We indulged in certain things that are characteristic of July and August. We stayed out occasionally too late, we complained about the heat and lounged around, we missed some deadlines, we went to the beach and the lake and swam in cold water. We had wins and losses of all kinds—at least I did, or I was noticing them more than usual, because I’ve had more of both this year than I have ever had in my life.

We won our last game, very handily, against Harper’s in Chelsea Park. It was August 31 but there was a bit of September in the air—something we were remarking on before the game because that’s the kind of thing one remarks on at this time of year. The floodlights had come on and it was really dusk by the time we headed to the bar, where we stayed a little too long, though in fact that was the right thing to do on this particular evening. When I got home I sat on my stoop a little drunk and called my friend Ben, who is maybe the most angelic of all my friends, on whose couch I have slept in the middle of crises for nearly a decade now, and who came to all our softball games this summer except the last one, something I appreciated much more than I had told him. He was at a party in Bushwick but picked up. We talked on the phone for a little while—I wanted to tell him about some problem I had been having, some minor drama of the heart (feckless, indecisive, et cetera). I started to, but instead I ended up talking about softball, which was more interesting anyway. What I wanted to tell him but didn’t manage to (drunk, shy, et cetera) was that I had been so happy to play the game with him all summer—that it had in fact reinvigorated me during what might have been a difficult time in my life. I realized all of a sudden that I was very happy and that softball was more or less the reason for it, or one of them, and that this was a funny and surprising turn my summer had taken, one which makes me laugh a little just thinking about it.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

September 1, 2022

Seven, Seven, Seven: A Week in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Edouard Godard & Vilmorin-Andrieux & Cie, Les plantes potagères, 1904. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

DAY ONE

I sit at the long blond pine table I use for a desk. Nothing happens. Maybe I can make something happen.

A few years ago there was a popular self-help book called How To Make Sh*t Happen, never mind that peristalsis is involuntary. I eat some mango slices and a green apple and a banana. I drink twelve ounces of whole milk with a scoop of whey protein. I find a leftover fried artichoke in the fridge, wrapped in aluminum foil.

I listen to Michael Gielen conducting Anton Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, but it’s not loud enough.

“Have you seen the ghost of John?” we used to sing at my elementary school. “Long thin bones with the skin all gone. Wouldn’t it be chilly with no skin on?” It would be red. My inner life is none of my business.

Now I’m listening to Otto Klemperer conducting Bruckner’s Seventh, turned up loud enough that it’s antisocial.

*

In the beginning was the plan, and my plan for this culture diary was seven days of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony.

Seven different conductors: Böhm, Klemperer, Gielen, Sanderling, Haitink, Barenboim, and Celibidache.

Seven friends: Barry, Andy, James, Hank, Michael, Billy, and Mark, all of them Bruckner hounds.

“Seven, Seven, / Seven is my name,” as Glenn Danzig howled when I was in high school in Kentucky. But the plan failed, as plans do. I thought it might.

*

My first full-time job was on an assembly line. We made furniture-moving pads: quilted them, sewed their edges shut, pressed them flat and packed them in clear plastic bags, and loaded tractor trailers full of the bags. One day the kid at the next machine asked if he could listen to the cassette I had in my Walkman. He pressed Play and he made a face. “What is this?” he said. “Classical music, like Beethoven or some shit?”

The job paid minimum wage, and it wasn’t safe. One day my machine jammed and kicked and spat needle fragments at me that cut my face near my right eye. But I liked throwing the bags into the trailers. It made me feel strong. At lunch I could walk across the train tracks to Xpressway Liquors—which was run by flinty, mulleted twins who kept a pair of bratty cockatoos in big cages in the store—and buy a box of fried chicken livers and be back at my machine on time.

Now I am listening to Bruckner or some shit, highfalutin as can be, drinking a cold beer on a summer day, thinking of all the decent people who loved me, encouraged me, taught me, helped me, and were patient with me, who wished the best for me, who wanted or even demanded that I leave my family behind and become someone completely different from my father, who was my hero—all those well-meaning people who insisted that I would enjoy being a class traitor in the air-conditioning, educated beyond my station.

But I remember Eden. Eden was green and it was called Fern Creek, south on Bardstown Road until the super-Kroger parking lot before you run into I-265/KY-841, the Gene Snyder Freeway.

*

My interest in Bruckner’s symphonies comes from the scroungiest source possible, a 1969 science fiction novel by Colin Wilson called The Philosopher’s Stone:

I came across Fürtwangler’s remark that Bruckner was a descendant of the great German mystics, and that the aim of his symphonies had been to ‘make the supernatural real’ … I put on Fürtwangler’s recording of the Seventh Symphony, and immediately understood that this was true. This music was slow, deliberate, because it was an attempt to escape the nature of music—which, after all, is dramatic; that is to say, it has the nature of a story … Bruckner, according to Fürtwangler, wanted to suspend the mind’s normal expectation of development, to say something that could only be expressed if the mind fell into a slower rhythm.

The book’s hero develops supernatural powers of focus and attention, beginning by listening to Fürtwangler conduct Bruckner’s long symphonies. He uses his insight to rip the veil, to see through the mask, to penetrate our world’s inner life. Wilson wrote the story on a bet, having mocked H. P. Lovecraft until August Derleth, executor of Lovecraft’s estate, dared Wilson to produce something superior.

Most of us know how a Lovecraft-style story goes. A terrifying secret exists. The secret is a secret by virtue of its being unnameable. Are words adequate to the task? This permanent secret can be called God, and God, an unknowable creator-origin, is generative to the point of being unsanitary and self-contradictory, perceptible only as a flickering, disjunct, climactic-orgasmic list of characteristics. The cost of a revelation of God is a shattering insanity and a need to escape from life, whether into institutionalization or through death, but in any case to no longer exist in an unmasked world. A Lovecraft story is the discovery of an insight that brings only unhappiness and terror.

All this to say that twenty-five years ago, I set out to develop my own powers of insight by listening to Bruckner symphonies. Dumb.

*

I can’t stand the stench of this orchestra any more. I call Jean at Guitar Stop, and we special order the Gretsch G5700 Electromatic lap steel I’ve had my eye on since May.

I listen to The Economist’s podcast on how to prevent a war between the United States and China, as if anyone, anywhere, knows how to do that. It’s like Daron Acemoglu’s book Why Nations Fail. I read it. But did I learn why nations fail?

I give up on Kultur for the day and listen to James Burton and Ralph Mooney’s Corn Pickin’ and Slick Slidin’, Sonny Clark’s Leapin’ and Lopin’ with Billy Higgins on drums, and the Jesus Lizard: “Why don’t you set up a camera to record your own death, dear?” Maybe I will.

DAY TWO

No culture consumed today. Closed until further notice.

To-do lists are bogus. What you want is a to-don’t list. The most important part is knowing what to leave out.

Socrates, in the marketplace, said: How many things exist that I do not desire.

A quick look back at my summer reading. The Financial Times, The Economist, Kim Stanley Robinson’s The High Sierra: A Love Story, Stephen R. Donaldson’s five-volume Gap series, Scott Jurek’s Eat and Run, David C. Lees and Alberto Zilli’s Moths, the London Review of Books, The New Yorker, Harper’s, the Times Literary Supplement, Michio Kaku’s The God Equation, Francesca Stavrakopoulou’s God: An Anatomy, Meghan O’Gieblyn’s God Human Animal Machine, Jack Miles’s God: A Biography, John Scalzi’s The Kaiju Preservation Society, Martha Wells’s All Systems Red, and Nicole Kornher-Stace’s Firebreak.

It’s too much. Closed systems starve, open systems drown. That’s why you feel like you’re drowning, Johnny: because you are. I need more nothing in my life.

Mary Gaitskill reports a conversation with George Saunders: “Who looks out the window and thinks about trees? Only people in books do that.” More proof, if more proof were needed, that I am a person in a book.

DAY THREE

Coleman Hawkins on WHRB 95.3 FM’s The Jazz Spectrum.

If the most important part is knowing what to leave out, then what now? What next? What is culture? What is a diary?

That sounds kind of familiar. I consult my Paris Review culture diary of August 2010. Day three: “I am always inquiring into origins—what is culture, what is a diary—why not just make a mess of things. Stop preparing and act.”

I can’t stop sweating. I turn on Daniel Barenboim conducting Bruckner no. 7. It has a majesty that Sanderling and Klemperer’s interpretations lack. Often they seem merely dutiful, but maybe they are subtle and restrained where Barenboim is obvious or overemphatic. I’m no connoisseur—I can’t even spell that word. But we can’t quite call Barenboim bombastic, because no force of expression could be too great for Bruckner’s ideas. After all, his Ninth Symphony is dedicated “to my dear God, if He accepts it.”

Shut up about God. Shut up about God!

The problem is that religious devotion, as a habit of mind, is portable and nonspecific.

Jay Nordlinger writes that Bruckner was “a very, very religious man … When he heard church bells ring, he would drop to his knees, even if he was teaching a class.”

But Bruckner also “worshiped Wagner, and I do not intend much of an exaggeration: On his knees, he once said to the older composer, ‘Master, I worship you.’ ”

Bruckner had a habit of worship. And he didn’t pay much mind to whatever happened to be on the altar.

DAY FOUR

Barry’s in New Jersey, Andy’s in Vermont, James is in Quebec, Mark’s in California, Michael’s in Ohio, Hank is in Qatar.

Now Bernard Haitink conducts no. 7. This version is James’s favorite. “Very crisp brass,” he texts me, and it’s true that the articulation of many phrases is sharp, clipped, even bitten off. Many performances of these symphonies evoke the ocean, with a constant danger of blissed-out gloppiness. But Haitink is architectural, orthogonal, even gawky in moments. I like the sharp edges. Like Tyrone Power in The Mark of Zorro, sometimes I need a scratch to awaken me.

*

When I ask Barry for his favorite conductor of no. 7, instead he tells me the one he likes least: Sergiu Celibidache. “Made a career of excruciatingly slow performances … Almost parodically attenuated.”

As for slow, yes, the performance takes 33 percent longer than any version I’ve heard. But I wouldn’t call it excruciating. That’s not what pain means to me.

DAY FIVE

Long blank summer days. The silence between the notes is the most important part of the music.

When my friend S. got killed, I helped his sister clean out his house. It was full. Full of “art,” sure, whatever, but mostly just packed full, tumorized, slam-crammed. Hard to breathe in there. Horror vacui.

Opposing view: Douglas Coupland said, “I hoard space.”

Now Sanderling conducts no. 7. It really is a lot of Bruckner. Tell me what you hear, I will tell you who you are.

That’s enough Bruckner for the day. Instead, Paul Humphrey drumming with Zappa on “The Gumbo Variations,” and a video that always makes me feel happy: Dan Weiss’s “Drumset/Speech pairing” of Big Pun’s “Twinz.”

DAY SIX

“Even as Thou, Eternal Spirit, hast seen me, so have I laid bare my soul”: thus Rousseau.

In 2018, Stig Abell compared me to Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the Times Literary Supplement. “Rousseau certainly did not invent the literary confession (one would not wish to snub St Augustine in any credit-giving stakes), but he did establish a new tone of honesty and chaotic inclusivity … Daniels is a worthy descendant, then, of Rousseau himself.” Abell did not mean it as a compliment, but I have rarely received a more flattering insult.

My playlist laid bare. The CD player and record player don’t keep score. What are the last hundred-odd tracks I listened to on this laptop?

Bruckner, Miff Mole, Jay-Z, more Bruckner, Glass Animals, Kodak Black, Kanye, Zappa, Richter playing Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, Guitar Slim, Gary Burton, Nathaniel Rateliff & the Night Sweats, Ron Jarzombek, Lloyd Green and Jay Dee Maness, Waylon Jennings, Clarence White, Traditional Fiddle Music of Kentucky, Turnstile, AC/DC, Anthrax, Kvelertak, more AC/DC, Ogdon playing Scriabin, Mastodon, Pantera, Twin Temple, Haydn’s String Quartet no. 63, still more AC/DC, Rob Zombie, the Jesus Lizard, Eric B. & Rakim, Lil Wayne, John Coltrane with Red Garland, Nicki Minaj, Kate Bush, Rich Homie Quan, UGK, Stan Getz, Kid Ory, Artie Shaw, Theo Hill, Wayne Shorter, Jay McShann, Thelonious Monk, still more Bruckner, more Jesus Lizard, more Waylon, Merle Haggard, Bach, the Flying Burrito Brothers, New Riders of the Purple Sage, John Scofield, Jack Teagarden, Lee Morgan, Charlie Parker, Superwolf, more Scofield, Steve Reich, and even more Bruckner.

DAY SEVEN

This is the end.

I haven’t developed new Brucknerian powers of insight. I feel as smashed and scatterational as I ever did. But maybe that is the insight. Maybe it is an accurate instrument reading. Or maybe I didn’t give Wilson’s method a fair shot. After all, I haven’t listened to a Fürtwangler version.

“Let me put this in the clearest way possible,” Wilson writes on the last page of The Philosopher’s Stone. “Man should possess an infinite appetite for life. It should be self-evident to him, all the time, that life is superb, glorious, endlessly rich, infinitely desirable.”

A happy beginning, in other words, and a happy middle, and a happy ending. Once upon a time, nothing happened.

But never mind all that now. Fürtwangler is conducting the adagio to Bruckner no. 7. I hear the secret. I burst into flames.

J. D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Award and the Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His collection The Correspondence was published in 2017. His writing has appeared in The Paris Review, Esquire, n+1, Oxford American, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

August 31, 2022

Goethe’s Advice for Young Writers

“Here lived Peter Eckermann, Goethe’s Friend, in the Year 1854” (plaque honoring Eckermann in Ilmenau). Photo by Michael Sander, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Johann Peter Eckermann was born in 1792. In 1823 he sent Johann Wolfgang von Goethe a collection of his essays about the writer’s works, and he became Goethe’s literary assistant till the latter’s death in 1832. The following is an entry from Eckermann’s diary that recounts one of their early meetings.

Thursday, September 18, 1823

Yesterday morning, before Goethe left for Weimar, I was fortunate enough to spend an hour with him again. What he had to say was most remarkable, quite invaluable for me, and food for thought to last a lifetime. All Germany’s young poets should hear this—it could be very helpful.

He began by asking me whether I had written any poems this summer. I said that I had written a few, but on the whole had not felt in the right frame of mind for poetry. To which he replied:

Beware of embarking on a great work. This is the mistake that our best minds make, the very people with the most talent and the fiercest ambition. I made the same mistake myself, and I know what it cost me. There was so much that came to nothing! If I had written everything that I perfectly well could have, it would have filled more than a hundred volumes.

The present demands its due; the thoughts and feelings that crowd in upon the poet every day need to be put into words, and so they should be. But if your mind is taken up with some great work, nothing else can get a look in; all other thoughts are pushed aside, and you cannot even enjoy the ordinary pleasures of life. It requires a vast amount of exertion and mental effort just to shape and organize a great whole, and a vast amount of energy, plus a period of uninterrupted peace and quiet in one’s life, to get it all down on paper in one continuous draft. But if you have picked the wrong subject to start with, then all your efforts are wasted; and if, furthermore, having undertaken something so large, you are not fully in command of your material in some of its parts, the whole thing will be unsatisfactory in places, and the critics will take you to task. So what the poet gets for so much effort and sacrifice is not reward and pleasure, but only stress and the undermining of his confidence. But if, on the other hand, the poet attends to the present moment each day, and writes with freshness and spontaneity about whatever comes his way, he is sure to produce something of value; and if, once in a while, something doesn’t work out, then nothing is lost.

August Hagen in Königsberg, for example, is a splendidly talented writer. Have you read his Olfrid und Lisena? There are passages in there that cannot be improved upon: the evocation of life on the Baltic coast, and anything relating to the local setting, are all masterly. But these are only beautiful passages: the work as a whole fails to satisfy. And yet to think what labor and effort he lavished upon it—the man almost worked himself to exhaustion! And now he has written a tragedy.

Goethe paused a moment and smiled. I spoke up to say that, unless I was very much mistaken, he had advised Hagen in Kunst und Altertum to tackle only small subjects.

“I certainly did,” replied Goethe,

but do people take any notice of what we old-timers say? Everyone thinks he knows best, with the result that many young writers lose their way, and many stay lost for a long time. But people should not be getting lost now; that’s what our generation was about—seeking and going astray; and what was the point of it all, if you young people are just going to go down the same paths that we did? We’d never get anywhere like that! Our generation’s errors were not held against us, because we found no beaten paths to tread, but we must expect more of those who come after us. Instead of seeking and going astray all over again, they should be heeding the advice of us old folk and following the right path from the beginning. It is not enough to take steps that will one day lead you to your destination; each step should be both a destination in itself, and a step along the way.

Keep in mind what I have said and see how much of it works for you. I am actually not worried about you, but with my encouragement, perhaps, you will quickly get through a phase that does not suit your present situation. For now, as I say, you should stick to small subjects and keep it spontaneous, just the things that present themselves each day—and generally speaking, you will always produce something good, and each day will bring you joy. Start by sending your work to the pocketbooks and periodicals, but never submit to the demands of others. Always follow your own instincts.

The world is so vast and rich, and life so full of variety, that you will never be short of inspiration for poems. But they must always be “occasional poems,” in the sense that real life must present both the occasion and the material. A particular instance becomes universal and poetic by virtue of the fact that the poet writes about it. All my poems are “occasional,” being inspired by real life and firmly grounded in it. I have no time for poems that are plucked out of thin air.

Don’t let anyone tell you that real life is lacking in poetic interest. This is exactly what the poet is for: he has the mind and the imagination to find something of interest in everyday things. Real life supplies the motifs, the points that need to be said—the actual heart of the matter; but it is the poet’s job to fashion it all into a beautiful, animated whole. You are familiar with Fürnstein, the so-called “nature poet”? He has written a poem about growing hops, and you couldn’t imagine anything nicer. I have now asked him to write some poems celebrating the work of skilled artisans, in particular weavers, and I am quite sure he will succeed; he has lived among such people from an early age, he knows the subject inside out, and will be in full command of his material. That is the advantage of small works: you need only choose subjects that you know and have at your command. With a longer poetic work, however, this is not possible. There is no way around it: all the different threads that tie the whole thing together, and are woven into the design, have to be shown in accurate detail. Young people only have a one-sided view of things, whereas a longer work requires a multiplicity of viewpoints—and that’s where they come unstuck.

I told Goethe that I was planning to write a longer poem about the seasons, into which I would weave the occupations and amusements of all the different classes. “This is exactly what I am talking about,” said Goethe:

You may succeed in large parts of the poem, but in others you will fail, because you have not studied the subject properly and lack the necessary knowledge. So you might get the fisherman right—but not the hunter. But if you get anything at all wrong, then the whole thing is compromised, however good it might be in parts, and you have failed to produce something perfect. If, on the other hand, you take only those parts that are within your capabilities, and make them into separate works, then you are sure to produce something good.

I must warn you especially against grand subjects of your own invention. That involves giving a particular view of things—and young people are seldom mature enough for that. Furthermore, the poet’s stock is depleted by the characters and viewpoints he creates; so he lacks the resources for further productions. And finally, think how much time it takes to dream up the material, then structure it and tie it all together—time that nobody thanks us for, even supposing we manage to complete the work in the first place.

With given material, on the other hand, it’s all different, and so much easier. The situations and characters are already sup plied, and all the poet has to do is bring them to life. He keeps his own stock intact, not needing to bring much of himself to the task; the expenditure of time and energy is far less, because all he has to worry about is the execution. I would go so far as to advise choosing subjects that have already been done. Iphigenia, for example, has been done so many times, yet each version is different, because each writer sees things differently and presents them in his own way.

But for now, you should put aside any grand schemes. You have pushed yourself hard for long enough; it is time for you to start enjoying life, and the best way to do that is to tackle small subjects.

During this conversation we had been pacing up and down the room. I found myself agreeing with everything he said, as every word rang true in my innermost being. I felt lighter and happier with every step, for I have to confess that various larger projects of mine, which I had not yet been able to sort out in my mind, had been weighing quite heavily upon me. I have now put them to one side, where I will leave them until such time as I can come back to them with a light heart and work up one subject and one scene after another, as I gradually, through study of the world, become master of each part of my material.

I feel that I am several years further on and several years the wiser as a result of Goethe’s words, and deep within my heart I know the special joy of understanding what it means to meet with a true master. The rewards are incalculable.

I shall learn so much from him this winter, and I shall gain so much just by spending time in his company—even when he is not saying anything of particular moment. It seems to me that his person, his mere physical presence, has a civilizing and formative effect, even if he says nothing at all.

Translated by Allan Blunden.

Eckermann’s Conversations with Goethe will be published by Penguin Classics this September.

August 30, 2022

Like Disaster

Nature × Humanity: Oxman Architects at SFMOMA. Photograph by Matthew Millman.

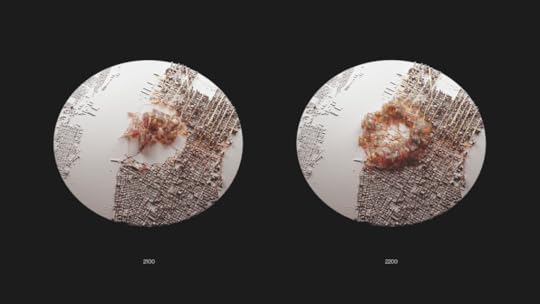

If you went to the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco this spring you could see a big small thing, a model that imagines what Manhattan will look like in 400 years. Actually Man-Nahāta is not one model but four, which hang in a square. Starting at the bottom left and walking clockwise you see a version of the city every hundred years, beginning in 2100. Emergence, the first in the series, is a grid of streets and skyscrapers, except for where an organic glassy form appears in Central Park, black and yellow and blue lit from below, awful. In Growth (set in 2200) the form expands in concentric and overlapping spirograph shapes, an almost periwinkle blue at the edges, rippling amber toward the center, where it calcifies into hills. By Decay (2300) it flows back, leaving edges of buildings made soft, eroded into shapes like melted candles. In Rebirth (2400) the built environment is overgrown, peaks and valleys where a city used to be, made of white chalky photopolymers and fiberglass.

Man-Nahāta was commissioned by the director Francis Ford Coppola, who hired the architect Neri Oxman and the OXMAN group to create studies for Megalopolis, an epic set in a future New York City that starts production this year. Made for a movie that does not yet exist, the model has its own narrative, based in part on the projected mean global sea level and surface temperature rise in the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Most people walked around it the wrong way, or maybe not wrong but counterclockwise, changing the story. The glassy form recedes, buildings sharpen, streets reappear. You could circle the model again and again, speeding up or slowing down time, repeating the disaster or undoing it. Susan Stewart writes in On Longing that the miniature, “linked to nostalgic versions of childhood and history, presents a diminutive, and thereby manipulatable, version of experience, a version which is domesticated and protected from contamination. It marks the pure body, the organic body of the machine and its repetition of a death that is thereby not a death.”

***

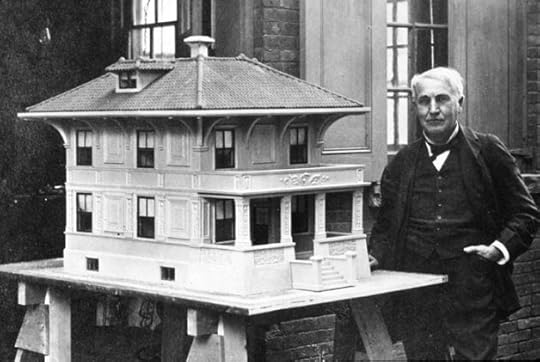

Film has always tangled with architecture and invention. In 1888, Eadweard Muybridge took his pictures of horses in motion to the New Jersey laboratory of Thomas Edison. Soon after, Edison filed a patent for the kinetoscope, an early moving picture machine. William K. L. Dickson and William Heise made the first film for the Edison Manufacturing Company in 1892. Around this time Edison was bought out of General Electric and started the Edison Portland Cement Company. He made designs for concrete homes that could be built with a single pour, which Edison described as “the most wonderful advance in science and invention the world has ever known, or hoped for.” The houses would be affordable, fireproof, and made on site. There is a photograph of the inventor next to a two-story prototype with a covered porch and balcony, windows evenly spaced, and decorative molding. Edison wears a dark suit, his tie askew and his left hand in his front pocket. Man and his little house.

Thomas Edison. Courtesy of the National Parks Service.

Architects and filmmakers use models to picture the new, unseen, or impossible. In this way they tend toward the utopian. They share a capacity to make and unmake, not always successful. Only a few of the Edison concrete homes were ever made. There is a 1901 stop-motion nonfiction film called Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre, made by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, rival to Edison. In the film, the Star is not a model, but filmed from across the street it looks little, manipulable. Awnings shift in the wind below a marquee decorated with stars, an arch where the name of the theater is printed in capital letters. Time passes in traffic and shadows, and the Star disappears brick by brick, from the top down: the deconstruction of a real building, but never the repair promised in the title.

The research team for Man-Nahāta included Christoph Bader, Anran Li, Nitzan Zilberman, David Franck, Grey Wartinger, Khoa Vu, and Neri Oxman, who collaborated with Kennedy Fabrications and Boris Belacon. Materials at SFMOMA directed visitors to the OXMAN website, though the first time I visited the museum there was nothing online about Man-Nahāta. Now there are computer simulations, architectural renderings, and an exploded view of the physical models. Coppola plans to spend $100 million making Megalopolis, here summarized as “about an architect seeking to rebuild New York City as a utopia in the wake of disaster.” Adam Driver plays the architect. @oxmanofficial describes itself as “fusing design, technology, and biology to enable a future of complete synergy between Nature and humanity.” Among their first principles is “I. Nature as co-client: We call for a shift in how we perceive clientele and commercial viability, turning Nature into a co-client within the design practice.”

***

At SFMOMA two different kids asked the adults with them, “Is this all of San Francisco?” I watched a couple try to guess the city. The woman said it looked like New York. The man said, “It’s not Chicago,” which was funny to me. It was easy to miss the wall text—for some reason printed on what looked like tracing paper—which included the projected temperature and sea level rise for each subsequent model and said: “OXMAN, based in New York’s populous Manhattan borough, revisited the precolonial history of the local terrain, when it was known as Mannahatta (‘land of many hills’), identifying a period of rich biodiversity. In the four site-specific models on view here, OXMAN envisions an ecological evolution in which Manhattan’s urban grid and Mannahatta’s biotic garden achieve symbiosis.” The model shows climate change and a way out of it, or at least the recovery of the built environment by the natural world. But something makes it hard to read.

By making disaster small we can see it better, or maybe we just like it that way. In the nineteenth century you could buy transferware plates of the Merchants’ Exchange Building during the 1835 Great Fire or see a touring diorama of the Royal Tar, a Canadian circus steamer that exploded in 1836. On May 31, 1881, a dam on the Little Conemaugh River broke and flooded Johnstown, Pennsylvania, killing at least 2,209 people. The 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo included a mechanical reenactment of the event, which the Edison Company recorded on film. San Francisco Disaster was made by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company in May 1906, under a month after the April 18 earthquake and fire that destroyed almost 80 percent of the city and killed over three thousand people. From an aerial view somewhere south of Market Street, you watch a model of San Francisco burn, three minutes of real flames with the Ferry Building at lower right and a few other landmarks—the Call Building and a painted backdrop of Russian Hill and Telegraph Hill. Nothing is exactly where it should be, a compressed geography. When I showed this film in a class on disasters the students seemed relieved when I said it was maybe kind of boring. Like watching the Yule log on television.

“The amusement park and the historical reconstruction often promise to bring history to life,” Stewart writes, and like these the miniature can bring events “to immediacy, and thereby erase their history, to lose us within their presentness.” A few months ago a friend sent me a picture of an animatronic model of the 1906 landslide at the Haverstraw Brick Factory, taken at the Haverstraw Brick Museum in Haverstraw, New York. Nineteen people died in the disaster. You could watch a video of the model, but the model itself was not working. They were waiting, my friend said, for the animatronic landslide model mechanic from Massachusetts, who was coming the next day.

***

There are two kinds of special effects, visual and practical. Visual effects involve the manipulation of film stock, or computer generated images. Practical effects include things like makeup, props, and explosions. Some kinds of disasters are easier to make than others, like wind and storms. Fire and floods are harder. Before backlots and movie ranches, California studios filmed at nearby locations like Griffith Park, and once burned down a ranger cabin. In mid-century Hollywood, mechanical sets and models were used to stage disasters. Some of these were made for movies about real events, which spend an hour on detailed reconstruction of the historical past, and then destroy it. Here comes the big one.

James Basevi and A. Arnold Gillespie designed a full-size set for the earthquake in San Francisco (1936) that rolled and split apart to precede a montage directed by John Hoffman. For In Old Chicago (1938), Fred Sersen, Ralph Hammeras, Louis J. Witte, H. Bruce Humberstone, and Daniel B. Clark used matte screens and burning eight-foot miniatures to recreate the 1871 Great Fire. “The transcendence presented by the miniature is a spatial transcendence, a transcendence which erases the productive possibilities of understanding through time,” Stewart writes. “Its locus is thereby the nostalgic. The miniature here erases not only labor but causality and effect. Understanding is sacrificed to being in context. Hence the miniature is often a material allusion to a text which is no longer available to us, or which, because of its fictiveness, never was available to us except through a second-order fictive world.”

Theodore and Howard Lydecker made many of the best practical effects in mid-century Hollywood. Their father worked for the actor Douglas Fairbanks and designed miniature golf courses. The brothers joined Republic Pictures in 1938 and created everything from title cards to props. They were skilled at pyrotechnics and demolition but their main work was building and filming miniatures, with Theodore as designer and Howard behind the camera. Not every model was wrecked. Some gave a sense of place, a wider view: towns and cities and the scale railroad they built for the Joan Crawford western noir Johnny Guitar, shot in natural light. They hardly ever used painted backdrops, instead filming from well-chosen angles and in slow motion, which when sped up to normal rate gave footage the right sense of mass and scale, complete with papier-mâché bat men and balsam airplanes that exploded in the sky. (Stewart writes that the “reduction in scale which the miniature presents skews the time and space relations of the everyday lifeworld, and as an object consumed, the miniature finds its ‘use value’ transformed into the infinite time of reverie.”) An outdoor model based on photographs of the San Gabriel Dam was decorated with tiny trees and held up to thirty gallons of water. In The Phantom Empire (1935), Gene Autry is captured by aliens and taken to an underground city called Murania, a model kingdom later destroyed.

Flame of Barbary Coast (1945) is set before the 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco, and like in San Francisco and In Old Chicago you wait around for the disaster. John Wayne plays a cowboy turned casino owner whose first line is “Big, isn’t it?” He is looking at the Pacific Ocean. But a disaster movie is always a question of scale. The earthquake sequence cuts together collapsing set walls, rolling pavement, cracking brick, a broken water main, a falling telegraph pole, and fire. Some of the footage has an odd and almost tilted focus: small made to look big. The Lydecker brothers built a six-foot-tall San Francisco. In one production photograph, Howard, Theodore, and two crew members work on a row of Victorian buildings. Through the windows you can see interior walls already collapsed. A man in a white shirt extends to reach the top floor, one last touch before the model is burned down. After the disaster a newspaper reads:

Quake damage less than expected

Destruction confined to limited area

Fire greatest hazard

***

OXMAN, Man-Nahāta (detail), 2021. Courtesy of OXMAN, 2021.

A sign at the beginning of the OXMAN show:

The artworks in this show are delicate.

Please do not touch or interact with them.

Man-Nahāta was suspended about three feet off the floor, for me about waist height. To look at it I had to bend. Crouched, forward, curious, I saw a layer of dust had settled on the city. I felt self-conscious, aware of how small and fragile the model was. It was easy to imagine Manhattan ruined by me. Maybe this is an accident, the way the model recreates the disaster it describes, or at least our responsibility for it—the anthropocene in miniature.

The second time I went to the museum, I watched a guard warn visitors away. It happened at least four times. There was a pair of women, and a man on his own who moved to another part of the gallery after being told to watch his feet. A teenage boy and his mom, who walked right to the center of Man-Nahāta. Another woman did the same thing. I smiled at the guard, who came over to talk to me. She told me to take a picture, now that the area was clear of people, and because it seemed like I liked the model, let me know that the show was closing soon. I thanked her and went back to a nearby bench. I sat there a long time. I think what I really liked was watching people cross the line.

Rachel Heise Bolten is a writer based in California.

August 26, 2022

Our Favorite Sentences

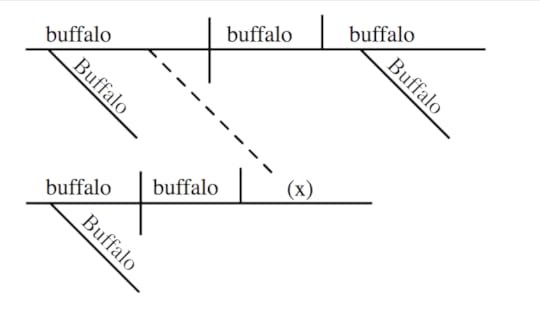

Sentence diagram of the sentence Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo. Craig Butz, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

From Stoner by John Williams:

And so he had his love affair.

And:

In his forty-third year William Stoner learned what others, much younger, had learned before him: that the person one loves at first is not the person one loves at last, and that love is not an end but a process through which one person attempts to know another.

These two sentences, pages apart, are both perfect. It should be obvious why, but perhaps they are more perfect because the first precedes the second, and the second is a kind of cracking open of the first or maybe a kind of blooming, grammatically and otherwise.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

And more of our favorite lines from our recent reading:

From “The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick:

She only stood, because if she ran they would shoot, and if she tried to pick up the sticks of Magda’s body they would shoot, and if she let the wolf’s screech ascending now through the ladder of her skeleton break out, they would shoot; so she took Magda’s shawl and filled her own mouth with it, stuffed it in and stuffed it in, until she was swallowing up the wolf’s screech and tasting the cinnamon and almond depth of Magda’s saliva; and Rosa drank Magda’s shawl until it dried.

—Camille Jacobson, business manager

From Milkweed Smithereens by Bernadette Mayer, forthcoming November 2022:

the rain it raineth every day & it will never stop, this will be good for the tomatoes, just above the bird feeder is blue sky, now thunder, no rainbows though

—David Wallace, advisory editor

I enjoyed many of the sentences in Amy Larocca’s profile of Kaitlin Phillips, but this was my favorite:

“So much of press is like, they teach you safe press,” Ms. Phillips said. “I’m incredibly into, like, edging.”

—Emily Stokes, editor

From Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer:

There are thick layers of filth coating her once-white feathers; the soot and dust and debris gathered over years of rare exchanges and scratchy landline calls made far too late; she stinks with it, shrinks in it, can’t rid her lead-grey life of it, and I feel quite encouraged, quite invigorated by this one, as she puffs her chest out and makes a few snide comments about a time when life was pure, before regret and penance and me.

—Clarissa Fragoso Pinheiro, intern

From “On the Island” by Gerald Stern, in Lucky Life:

I like to think of floating again in my first home,

still remembering the warm rock

and its slow destruction,

still remembering the first conversion to blood

and the forcing of the sea into those cramped vessels.

—Owen Park, reader

From Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land by N. Scott Momaday:

She has gone to the farther camps, but her bones are at home in the dress, in the earth.

—Jane Breakell, development director

From Youth by Tove Ditlevsen:

Childhood is dark and it’s always moaning like a little animal that’s locked in a cellar and forgotten.

—Campbell Campbell, intern

From Untitled (1–5) by Nazareth Hassan:

sounds of crusts falling

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

Cooking with Nora Ephron

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

I am a baker of pies and a believer in pleasures, but also the kind of killjoy who can’t take a rom-com in the spirit it’s intended. Hence my fraught relationship with Heartburn by Nora Ephron. I remember—from 1983, the year the book was published—it being marketed as a “hilarious” comedy about a woman cooking her way out of a broken heart at the end of a marriage. Heartburn was a cultural sensation in the suburbs of my youth, such that I recall my mother cackling over the film adaptation and criticizing Meryl Streep’s looks—not pretty enough! The story was said to be inspired by Ephron’s divorce from Carl Bernstein and has always been considered a delicious revenge plot by a spurned woman upon a cheating man.

Ephron had a dazzling career as a trailblazer for women in journalism, and she wrote many of the greatest movies of all time, including When Harry Met Sally. She was a master, so my cavils over Heartburn‘s myths about romance will be brief: I don’t think a woman who stays in a bad relationship is just a starry-eyed believer in true love, as the heroine, Rachel Samstat, is presented to be. Nor do I think that men are just dogs—which is the book’s explanation for her husband, Mark Feldman’s, behavior—or that the happiest ending is finding a new relationship. But Ephron, in Heartburn, wasn’t looking to soul-search—this was her revenge novel. At one point, Rachel, who is a food columnist, admits to her therapist that she tells stories about her life in order to “control” the narrative. Ephron, writing Heartburn, was controlling the narrative of her divorce while showing off her wit, and she did it wonderfully. The one-liners never cease, as when Rachel says that Mark celebrates the political dysfunction of Washington, D.C., because if the city worked, “something might actually be accomplished and then we’d really be in bad shape” and adds, “This is a very clever way of being cynical, but never mind.”

Ephron describes linguine alla cecca as a “hot pasta with a cold tomato and basil sauce” that’s “so light and delicate that it’s almost like eating a salad.” Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Heartburn includes sixteen recipes integrated into the narrative and an index at the back listing their page numbers (a convenience I wish more novels included). Could the dishes be as good as the story? Some are daily staples, like bacon hash, the perfect vinaigrette, or a “four-minute egg.” Others Rachel perfects in her personal life or writes about in her column, such as peach pie and “Lillian Hellman’s pot roast.” The pièce de résistance, a key lime pie, has plot significance: when Rachel finally decides to leave Mark, she throws it in his face.

More ingredients than I’m used to came from cans and packages. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The food in the novel reflects a transitional time in American cuisine, when cooking from cans was still respectable but the from-scratch movement was in its embryonic stages. Julia Child and Craig Claiborne had already, in the sixties and seventies, introduced Americans to a greater number of international cuisines, and to higher standards. The Silver Palate Cookbook, published in 1982, suggested we might make sophisticated foods casually at home. Ephron’s Rachel reflects these changing times. She uses more canned ingredients than we would today and cooks simply, but her linguine alla cecca, sorrel soup, and homemade pies have ambition. I wondered, while recreating her recipes for this column, if her kind of eighties cooking might have been, counterintuitively, a pinnacle: classy yet easy. Rachel’s vinaigrette has three ingredients—Dijon mustard, red wine, and olive oil. If they’re perfectly balanced, do we ever need to think about vinaigrette again? Her cheesecake filling has four ingredients, and the recipe makes it simple enough to be thrown together on a weeknight: no bringing things to room temperature before combining; no stress-inducing water bath while baking. Such dishes seemed promising.

I hadn’t eaten a lima bean since my seventies childhood. The casserole, baked overnight in a low oven, did not have a pleasing scent. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Others, like Lillian Hellman’s pot roast, which asks for “low-rent ingredients” like a can of cream of mushroom soup and a packet of dried French onion soup, seemed less so. There were also a few truly ominous outliers: a bread pudding calling for what seemed like too much of two powerful flavorings, nutmeg and vanilla; and a casserole of pears and lima beans from Rachel’s mother. This appalling dish is presented as an example of Rachel’s mother’s casual, irreverent attitude towards cooking, emblematic of her first-wave feminism, which Rachel, to some degree, reacts against. “My mother was a good recreational cook, but what she basically believed about cooking was that if you worked hard and prospered, someone else would do it for you,” Rachel says. She chooses a different path, one which does not include a pear-and-lima-bean casserole.

Because the recipes were so simple, I decided to try them all—with a small caveat—and thus provide the definitive word on the food in Heartburn. I’ve chosen the five best to reproduce below; anyone who wants the others need only buy a copy of the book. (The caveat was that there were three treatments for potatoes, grouped together in a single scene. I tried only one, and even better, I didn’t really have to try it, because Rachel’s method was identical to my own for making blissfully light and fluffy mashed potatoes.) The four-minute egg and the bacon hash were a morning’s breakfast. The outlier lima bean casserole required twelve hours in a two-hundred-degree oven, but even so, when I finally did the cooking, I made nine dishes in one day—in the time it usually takes me to make three or four. If I cooked like this every day, dinner would be more than fifty percent faster.

Ephron’s simple cooking method produced an incredibly tender pot roast. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Ephron’s recipes were fabulous. Almost every dish was either the best version of its kind I’d ever made, or a fresh, simple take on a classic. Linguine alla cecca is a Sicilian cart-style pasta made with garlic-tomato-basil sauce—everyone should be doing this if they aren’t already. Cold, green, lemony sorrel soup has fallen out of favor, but it should come back. The bread pudding with “too much” vanilla and nutmeg was perfect and took about five minutes to assemble prior to baking. The cheesecake is a recipe from Rachel’s father’s second wife, of whom Rachel says, “Everything she made was the lightest, the flakiest, the tenderest, the creamiest, the whateverest.” Its method went against all my rules of cheesecake and its filling was lumpy-looking, liquidy, and thrown-together prior to baking—yet the results were indeed the lightest, tenderest, creamiest. The four-minute egg has become my new breakfast. The vinaigrette, so flavorful it doesn’t require salt, is my new vinaigrette. The key lime pie was tart, creamy, and classic. The peach pie asked that a custard be poured over the fresh peaches, a new technique for me. (I found it, in the end, too sweet.) The pot roast skipped the tedious flavor-developing steps of browning the meat and caramelizing the onions, instead using the two instant soups and a lot of red wine. Perhaps this was a sacrifice on health or on authenticity, but it didn’t affect taste.

Sterling Vineyards makes a popular and conventional California chardonnay. Toasted almonds was another recipe from Rachel’s mother. Photograph by Erica MacLean.