The Paris Review's Blog, page 78

July 6, 2022

Why Write?

Photograph of light on water by Aayugoyal. Licensed under CC0 4.0.

I encountered Joan Didion’s famous line about why she writes—“entirely to find out what I’m thinking”—many times before I read the essay it comes from, and was reminded once again to never assume you know what anything means out of context. I had always thought the line was about her essays, about writing nonfiction to discover her own beliefs—because of course the act of making an argument clear on the page brings clarity to the writer too. She may have believed that; she may have thought it a truth too obvious to state. In any case, it’s not what she meant. She was talking about why she writes fiction:

I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means … Why did the oil refineries around Carquinez Strait seem sinister to me in the summer of 1956? Why have the night lights in the Bevatron burned in my mind for twenty years? What is going on in these pictures in my mind?

These pictures, Didion writes, are “images that shimmer around the edges,” reminiscent of “an illustration in every elementary psychology book showing a cat drawn by a patient in varying stages of schizophrenia.” (I know these frightening psychedelic cats, the art of Louis Wain, very well—I saw them as a child, in just such a book, which I found on my parents’ shelves.) Play It As It Lays, she explains, began “with no notion of ‘character’ or ‘plot’ or even ‘incident,’” but with pictures. One was of a woman in a short white dress walking through a casino to make a phone call; this woman became Maria. The Bevatron (a particle accelerator at Berkeley Lab) was one of the pictures in her mind when she began writing A Book of Common Prayer. Fiction, for Didion, was the task of finding “the grammar in the picture,” the corresponding language: “The arrangement of the words matters, and the arrangement you want can be found in the picture in your mind. The picture dictates the arrangement.” This is a much stranger reason to write than to clarify an argument. It makes me think of the scenes that I sometimes see just before I fall asleep. I know I’m still awake—they’re not as immersive as dreams—but they seem to be something that’s happening to me, not something I’m creating. I’m not manning the projector.

Nabokov spoke of shimmers too. “Literature was born on the day when a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him,” he said in a lecture in 1948. “Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story, there is a shimmering go-between.” In this view, it seems to me, the writer’s not the wraith who can pass between realms of reality and fantasy. The art itself is the wraith, which the artist only grasps at. Elsewhere, Nabokov writes that inspiration comes in the form of “a prefatory glow, not unlike some benign variety of the aura before an epileptic attack.” In his Paris Review interview, Martin Amis describes the urge to write this way: “What happens is what Nabokov described as a throb. A throb or a glimmer, an act of recognition on the writer’s part. At this stage the writer thinks, Here is something I can write a novel about.” Amis also saw images, a sudden person in a setting, as if a pawn had popped into existence on a board: “With Money, for example, I had an idea of a big fat guy in New York, trying to make a film. That was all.” Likewise for Don DeLillo: “The scene comes first, an idea of a character in a place. It’s visual, it’s Technicolor—something I see in a vague way. Then sentence by sentence into the breach.” For these writers that begin from something like hallucination, the novel is a universe that justifies the image, a replica of Vegas to be built out of words.

William Faulkner wrote The Sound and the Fury five separate times, “trying to tell the story, to rid myself of the dream.” “It began with a mental picture,” he told Jean Stein in 1956, “of the muddy seat of a little girl’s drawers in a pear tree.” He couldn’t seem to get it right, to find the picture’s grammar, or hear it. (According to Didion, “It tells you. You don’t tell it.”) This was part of the work, this getting it wrong—Faulkner believed failure was what kept writers going, and that if you ever could write something equal to your vision, you’d kill yourself. In his own Paris Review interview, Ted Hughes tells a story about Thomas Hardy’s vision of a novel—“all the characters, many episodes, even some dialogue—the one ultimate novel that he absolutely had to write”—which came to him up in an apple tree. This may be apocryphal, but I hope it isn’t. (I imagine him on a ladder, my filigree on the myth.) By the time he came down “the whole vision had fled,” Hughes said, like an untold dream. We have to write while the image is shimmering.

There is often something compulsive about the act of writing, as if to cast out invasive thoughts. Kafka said, “God doesn’t want me to write, but I—I must.” Hughes wondered if poetry might be “a revealing of something that the writer doesn’t actually want to say but desperately needs to communicate, to be delivered of.” It’s the fear of discovery, then, that makes poems poetic, a way of telling riddles in the confession booth. “The writer daren’t actually put it into words, so it leaks out obliquely,” Hughes said. Speaking of Sylvia Plath, in 1995, he added, “You can’t overestimate her compulsion to write like that. She had to write those things—even against her most vital interests. She died before she knew what The Bell Jar and the Ariel poems were going to do to her life, but she had to get them out.” Jean Rhys also looked at writing as a purgative process: “I would write to forget, to get rid of sad moments.” Some reach a point where the writing is almost involuntary. The novelist Patrick Cottrell has said he only writes when he absolutely has to. “I have to feel borderline desperate,” he said, and “going long periods without writing” helps feed the desperation. Ann Patchett, in an essay called “Writing and a Life Lived Well,” writes that working on a novel is like living a double life, “my own and the one I create.” It’s much easier not to be working on a novel—I sometimes hear novelists speak of a work in progress as an all-consuming crisis—but the ease of not working, after a while, feels cheap: “this life lived only for myself takes on a certain lightness that I find almost unbearable.”

Some writers write in the name of Art in general—James Salter for instance: “A great book may be an accident, but a good one is a possibility, and it is thinking of that that one writes. In short, to achieve.” Eudora Welty said she wrote “for it, for the pleasure of it.” Or as Joy Williams puts it, in a wonderfully strange essay called “Uncanny the Singing that Comes from Certain Husks,” “The writer doesn’t write for the reader. He doesn’t write for himself, either. He writes to serve … something. Somethingness. The somethingness that is sheltered by the wings of nothingness—those exquisite, enveloping, protecting wings.” Is that somethingness the wraith, the shimmering go-between? Or a godlike observer? “The writer writes to serve,” she writes, “that great cold elemental grace which knows us.”

Though Faulkner felt a duty toward the work that superseded all other ethics (“If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies”!), he also found writing fun, at least when it was new. David Foster Wallace, in a piece from the 1998 anthology Why I Write, edited by Will Blythe, agrees: “In the beginning, when you first start out trying to write fiction, the whole endeavor’s about fun … You’re writing almost wholly to get yourself off.” (He’s not the only writer in the volume to describe writing as physical, almost sexual pleasure; William Vollmann claims he would write just for thrills but also likes getting paid, “like a good prostitute.”) But once you’ve been published, the innocent pleasure is tainted. “The motive of pure personal fun starts to get supplanted by the motive of being liked,” Wallace writes, and the fun “is offset by a terrible fear of rejection.” Beyond the pleasure in itself, the fun for fun’s sake, writing for fun wards off ego and blinding vanity.

For every author who finds writing fun there is one for whom it’s pain, for whom Nabokov’s shimmerings would not be benign but premonitions of the suffering. Ha Jin said, “To write is to suffer.” Spalding Gray said, “Writing is like a disease.” Truman Capote, in his introduction to The Collected Works of Jane Bowles, and perhaps a particularly self-pitying mood, called writing “the hardest work around.” Annie Dillard said that “writing sentences is difficult whatever their subject”—and further, “It is no less difficult to write sentences in a recipe than sentences in Moby-Dick. So you might as well write Moby-Dick.” (Annie Dillard says such preposterous things—“Some people eat cars”!) It’s fashionable now to object on principle to the idea that writing is hard. Writing isn’t hard, this camp says; working in coal mines is hard. Having a baby is hard. But this is a category error. Writing isn’t hard the way physical labor, or recovery from surgery, is hard; it’s hard the way math or physics is hard, the way chess is hard. What’s hard about art is getting any good—and then getting better. What’s hard is solving problems with infinite solutions and your finite brain.

Then there’s the question of whether the pain comes from writing or the writing comes from pain. “I’ve never written when I was happy,” Jean Rhys said. “I didn’t want to … When I think about it, if I had to choose, I’d rather be happy than write.” Bud Smith has said he’s only prolific because he ditched all his other hobbies, so all he can do is write—but “people are probably better off with a yard, a couple kids, and sixteen dogs.” Here’s Williams again: “Writing has never given me any pleasure.” And then there’s Dorothy Parker, simply: “I hate writing.” I love writing, but I hate almost everything about being a writer. The striving, the pitching, the longueurs and bureaucracy of publishing, the professional jealousy, the waiting and waiting and waiting for something to happen that might make it all feel worth it. But when I’m actually writing, I’m happy.

Didion borrowed the title of her lecture “Why I Write” from George Orwell, who in his essay of this name outlined four potential reasons why anyone might write: “sheer egoism” (Gertrude Stein claimed she wrote “for praise,” like Wallace in his weaker moments); “aesthetic enthusiasm” or the mere love of beauty (William Gass: “The poet, every artist, is a maker, a maker whose aim is to make something supremely worthwhile, to make something inherently valuable in itself”); “historical impulse,” or “desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity”; and finally “political purpose.” This last cause was what mattered to Orwell. “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936”—he was writing this ten years later—“has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.” He considered it “nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects.”

I’m unsure if Orwell meant that avoiding moral subjects was an unthinkable error, or a true impossibility, in the sense that one can’t escape the spirit of the age. Was any post-war novel, any novel written or even read in 1946, a war novel ineluctably? Kazuo Ishiguro has said he never writes to assert a moral: “I like to highlight some aspect of being human. I’m not really trying to say, so don’t do this, or do that. I’m saying, this is how it feels to me.” But having a moral, a didactic lesson, and being moral are different. Writers might try to avoid an argument and fail, even if it is less a thesis than an emergent property, a slow meaning that arises through cause and effect or mere juxtaposition. Ishiguro’s novels, in the course of unfolding, do triangulate a worldview. John Gardner would say, if the work is didactic, that means it’s too simple: “The didactic writer is anything but moral because he is always simplifying the argument.” (He also said, hilariously, “If you believe that life is fundamentally a volcano full of baby skulls, you’ve got two main choices as an artist: You can either stare into the volcano and count the skulls for the thousandth time and tell everybody, There are the skulls; that’s your baby, Mrs. Miller. Or you can try to build walls so that fewer baby skulls go in.”) The book can also stand in as an argument for its own existence. Toni Morrison wrote her first novel to fill what she saw as a treacherous gap in literature, to create a kind of book that she had always wanted to read but couldn’t find—a book about “those most vulnerable, most undescribed, not taken seriously little black girls.” Her ambition was not to make white people empathize with black girls. “I’m writing for black people,” Morrison once said, “in the same way that Tolstoy was not writing for me.”

Only one writer in the Blythe anthology, a magazine writer named Mark Jacobson, claims he does it “for the money.” (“What other reason could there be? For my soul? Gimme a break.”) No one in the book claims they do it for fame, though the luster of fame is tempting, distracting. In a TV documentary about Madonna that I saw many years ago, she said she always knew she wanted to be famous, and didn’t really care how she got there—music was just the path that worked out. This is not so different from Susan Sontag, who was also obsessed with fame from an early age. Plath too made such confessions in her diary. Capote often said he always knew he would be rich and famous. I think the wish for fame is reasonable, since practically there’s not much money in writing unless you are famous. For most the rewards are meager. As Salter writes, “So much praise is given to insignificant things that there is hardly any sense in striving for it.” The thing about success, good fortune, and maybe even happiness is this: You can see that there are people who “deserve” whatever you have as much as you do but have less, as well as people who “deserve” it less or equally and have more. So, at the same time, you want more and feel you don’t deserve what you have. It’s a source of anxiety, guilt, and resentment and troubles the very idea of what one “deserves.” In the end I believe you don’t deserve anything; you get what you get.

I’ve been collecting these theories of why writers write because so many writers have written about it. I love reading writers on writing. I love writers on their bullshit. During the first year of the pandemic, I started listening obsessively to interview podcasts. At first this was strategic. I had a book coming out, and I thought of them as training; I thought they would help me get better at talking about my own book. But I was also lonely. I wasn’t going to readings or parties, and I missed writers’ voices. The practice has diminishing comforts. After a while most writers sound the same, and some days, after bingeing on writers, I can start to feel pointless, interchangeable. Faulkner said he disliked giving interviews because the artist was “of no importance”: “If I had not existed, someone else would have written me, Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, all of us.” (And yet he named himself as one of the five most important authors of the twentieth century; there are limits to humility.) Some days I think the very question is banal, like photos of a writer’s “workspace.” They’re all just desks! Why write? Why do anything? Why not write? It’s the same as the impulse to make a handprint in wet concrete or trace your finger in the mist on a window. What you wrote, as a kid, on a window was the simplest version of the vision. Why that vision? Why that vision, and why you?

Tillie Olsen, in her 1965 essay “Silences,” called the not-writing that has to happen sometimes—“what Keats called agonie ennuyeuse (the tedious agony)”—instead “natural silences,” or “necessary time for renewal, lying fallow, gestation.” Breaks or blocks, times when the author has nothing to say or can only repeat themselves, are the opposite of “the unnatural thwarting of what struggles to come into being, but cannot.” The unnatural silence of writers is suppression of the glimmer. This is Melville who, in Olsen’s words, was “damned by dollars into a Customs House job; to have only weary evenings and Sundays left for writing.” And likewise Hardy, who stopped writing novels after “the Victorian vileness to his Jude the Obscure,” Olsen writes, though he lived another thirty years—thirty years gone, gone as that novel in the apple tree. She quotes a line from his poem “The Missed Train”: “Less and less shrink the visions then vast in me.” And this same fate came to Olsen herself, who wrote what she wrote in “snatches of time” between jobs and motherhood, until “there came a time when this triple life was no longer possible. The fifteen hours of daily realities became too much distraction for the writing.” I read Olsen’s essay during a period in my life when stress from my day job, among other sources, was making it especially difficult to write. I didn’t have the energy to do both jobs well, but I couldn’t choose between them, so I did both badly. Like Olsen, I’d lost “craziness of endurance.”

James Thurber said “the characteristic fear of the American writer” is aging—we fear we’ll get old and die or simply lose the mental capacity to do the work we want to do, to make our little bids for immortality. Of late I’ve been obsessed with the idea of a “body of work.” I’ve gotten it into my head that seven books, even short, minor books, will constitute a body of work, my body of work. When I finish, if I finish, seven books I can retire from writing, or die. But how long can the corpus really outlast the corpse? I heard Nicholson Baker on a podcast say his grandfather, or maybe some uncle or other, was a well-known writer in his day and is now totally unknown. Unless we’re very, very famous, we’ll be forgotten that quickly, he said, so you might as well write what you want. I think about that a lot. Since I don’t have children, I have more time to write than Tillie Olsen did. But I don’t have that built-in generation of buffer between my death and obscurity. At least I won’t be around to know I’m not known. DeLillo again: “We die indoors, and alone.”

That year when I walked so much while listening to writers that I wore clean holes through my shoes, I kept asking myself why I write—or more so, why my default state is writing, since on any given day I might be writing for morality, Art, or attention, for just a little money. (I can’t go very long without writing, though I can go for a while without writing something good.) I think I write to think—not to find out what I think; surely I know what I already think—but to do better thinking. Staring at my laptop screen makes me better at thinking. Even thinking about writing makes me better at thinking. And when I’m thinking well, I can sometimes write that rare, rare sentence or paragraph that feels exactly right, only in the sense that I found the exact right sequence of words and punctuation to express my own thought—the grammar in the thought. That rightness feels so good, like sinking an unlikely shot in pool. The ball is away and apart from you, but you feel it in your body, the knowledge of causation. Never mind luck or skill or free will, you caused that effect—you’re alive!

Elisa Gabbert is the author of six collections of poetry, essays, and criticism, most recently Normal Distance, out from Soft Skull in September 2022, and The Unreality of Memory & Other Essays. She writes the “On Poetry” column for the New York Times, and her work has appeared recently in Harper’s, The Atlantic, The New York Review of Books, and The Believer.

July 5, 2022

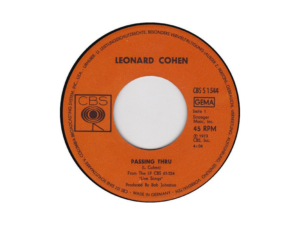

Beautiful Losers: On Leonard Cohen

From “The Lost Radio Interview.”

To mark the appearance of Leonard Cohen’s “Begin Again” in our Summer issue, we’re publishing a series of short reflections on his life and work.

In December 1981, I visited my older brother at the University of Michigan. There three men taught me to play three songs on guitar: “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” “Genesis,” and “Suzanne.” The first left me cold. The second, its melodic charms notwithstanding, featured the line “They say I’m harder than … a marble shaft,” leading me to believe, until just now when I finally looked him up, that Jorma Kaukonen was born in Finland and never really learned English. The third rocketed me, on my return to William & Mary, straight to the town record store, where the cashier sold me Songs of Leonard Cohen with a money-back guarantee on the condition that I listen to it ten times before complaining.

There existed milieus where Cohen’s music was inescapable, such as kibbutzim and the GDR. Tidewater, Virginia, was not that milieu. A basic tenet of its all-pervasive racism was that white people couldn’t do music. Black people were denied decent jobs and homes, but there was no question that high school dances would be themed “Always and Forever” and culminate in “Brick House” and “Flashlight.” At college, surrounded by northern suburbanites’ awkward skanking to babyish punk rock, I realized that I had been inadvertently blessed. But it did take me at least ten listens to acclimate to Cohen’s chansonnier velocity and compound meters while his lyrics were sinking their claws into my soul.

I taught myself all the songs on the record and borrowed his novels from the library. An image of sainthood from Beautiful Losers haunted me for decades: to live like a runaway ski. I blame The Favorite Game for the image of a sentient vibrator that drives a couple from their home, as well as a description of getting trapped in a writhing mass of young people at a political rally but failing to orgasm. I suspect they’re also from Beautiful Losers. The Favorite Game is about getting laid a lot in swinging Montreal (autobiographical).

I preferred the songs, which restored the human dignity the novels attacked. I remember singing “Why are you so quiet now / Standing there in the doorway” while a housemate I had a crush on stood quietly in the doorway. For once we were in each other’s presence yet not acting like idiots, our dopiness suspended by the schematic innocence of a simple song—transfixed by poetry, lost in the timeless intimacy of two people listening to one of them perform the beauty of someone else.

Then time resumed, and soon afterward he plunked down on my bed unannounced, not to sing “You Know Who I Am,” but to plead his stunningly counterproductive case for sex with me, citing what he saw as my indiscriminate promiscuity. I think the last time I saw him he was either cooking shirtless or staring at me across a dance floor, dressed as a pumpkin. Life could be so lyrical, if it weren’t a novel.

Nell Zink has published six novels, including the recent Avalon.

July 1, 2022

Emma Cline, Dan Bevacqua, and Robert Glück Recommend

Photograph by makeshiftlove, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 2.0,

This week, we bring you reviews from three of our issue no. 240 contributors.

The documentary Rocco, which follows the Italian porn actor and director Rocco Siffredi, feels like a hundred perfect short stories. We learn that Rocco carries around a photo of his mother at all times. We watch Rocco and his teenage sons chat in their cavernous and starkly lit climbing gym/weight room in Croatia. We discover that Rocco’s hapless cameraman of many decades, Gabriel, is actually his cousin, a thwarted porn star. During one virtuosic shoot (Rocco Siffredi Anal Threesome with Abella Danger) Gabriel accidentally leaves the lens cap on, which they discover only after shooting the entire scene. There’s a surprising sweetness in Rocco, a man in the twilight of a certain era. “They used to focus on the women’s faces,” he says, sadly. He’s decided to retire. The final scene finds Rocco carrying a giant wooden cross on his back through the hallways of the Kink.com Armory. This tableau is the brainchild of Gabriel. “Because you die for everyone’s sins,” he tells Rocco.

—Emma Cline, author of “Pleasant Glen”

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is about a lot of things: the last ever screening at Taipei’s Fu-Ho Grand Movie Palace; a ticket-taker who wants to gift half of a steamed bun to the projectionist; a young man cruising the theater for sex; and that lonely, amorphous feeling of THE END—not so much death as the cinematic mood of loss. When I heard about Goodbye, Dragon Inn, which was directed by Tsai Ming-liang and released in 2003, I could neither see it in a movie theater nor stream it anywhere. At the time, my brother was quarantining in a high-rise apartment building in Santiago, Chile. He found an illegal copy of it on the internet and sent it to me. I liked the criminality of this exchange. No character in Goodbye, Dragon Inn breaks the law, but it feels like there’s a crime going on. Part of this is due to the rain and the shadows and the grimy brokenness of the Fu-Ho Grand, but it’s mostly because Goodbye, Dragon Inn is a stripped down melodrama of longing. The ticket-taker is the film’s star. At one point, she goes behind the movie screen. The light hits her face. We seem to know nothing about her, but that’s not true. We know how, in the light of the screen, despite the forces that would stop her, she hopes and dreams. In this way, we know her exactly.

—Dan Bevacqua, author of “Riccardo ”

I’m currently reading INRI (published in William Rowe’s translation by NYRB/POETS), a book-length poem in which Raúl Zurita remembers the “disappeared” in Chile: those who vanished in the seventies, especially those who were thrown out of planes and helicopters into Chile’s ocean, volcanoes, and deserts. My dear friend Norma Cole gave me the book—her wonderful, learned preface provides an account of the different forms Zurita has used to address Pinochet’s murders. When the trauma of mass death replaces the rich complexity of the lives that have ended, it may take a generation or two for the richness of those lives to reenter the culture, in the past tense, as a memory. But what of a trauma whose existence has been suppressed? Zurita initiates this work of mourning by turning the world upside down, creating a new reality with a place for the knowledge of the dead. As William Rowe writes, “This poem seeks a place where the wound can be included inside the making of a different reality. That place requires a particular type of space, where what has been concealed, expunged from history, can appear.”

This is the kind of book I love—a book that is ambitious for literature itself. Zurita goes as far as he can, he goes to the limit. Sensation enters through the ear, because the victims’ eyes were torn out with hooks before they were thrown into the air. “I can hear the rabbit stunned by the headlights.” The dead are bait for the fish, snow for the mountains. The author enters the poem: first the murdered are “they,” then Zurita appears as himself. Then he joins the murdered “we.”

The Pacific breaks away from the coastline and

falls. First it was the cordilleras and now it is the

sea that falls. From the coast to the horizon it

falls. In an enemy country it is common for

bodies to fall, for the sea to break away from the

coast and fall like the daisies that groan as they

hear the cordilleras sinking where love, where

maybe love, Zurita, moans and weeps because

in an enemy country it is common for the Pacific

to collapse face down like a broken torso on the

Stones.

INRI is unsparing and sometimes ugly. When dealing with catastrophe, tact can be repellent. The strange title INRI is a salute to Christianity, but Zurita detaches love from the Christian narrative and recognizes it in the Chilean landscape. He proceeds by accretion and repetition of images that go through variations as a fugue, “from horror to love,” as Norma Cole says. There is no consolation, or if so, it is the conviction that life has value even when squandered in holocausts.

—Robert Glück, author of “About Ed”

The New York Review of Books and The Paris Review: Announcing Our Summer Subscription Deal

Love to read but hate to choose? Announcing our summer subscription deal: starting today and through the end of August, you really can have it all when you subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for a combined price of $99. That’s one year of issues from both publications, as well as their entire archives—sixty-nine years of The Paris Review and fifty-nine years of The New York Review of Books—for $50 off the regular subscription price.

Love to read but hate to choose? Announcing our summer subscription deal: starting today and through the end of August, you really can have it all when you subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for a combined price of $99. That’s one year of issues from both publications, as well as their entire archives—sixty-nine years of The Paris Review and fifty-nine years of The New York Review of Books—for $50 off the regular subscription price.

Ever since former Paris Review managing editor Robert Silvers cofounded The New York Review of Books with Barbara Epstein, the two magazines have been closely aligned. With your subscription to both, you’ll have access to fiction, poetry, interviews, criticism, and more from some of the most important writers of our time, from T. S. Eliot to Sigrid Nunez, James Baldwin to Toni Morrison, and Joan Didion to Jamaica Kincaid.

Subscribe today and you’ll receive:

One year of The Paris Review (4 issues)One year of The New York Review of Books (20 issues)Full access to both the New York Review and Paris Review digital archives—that’s fifty-nine years of The New York Review of Books and sixty-nine years of The Paris Review.If you already subscribe to The Paris Review, we’ve got good news: this deal will extend your current subscription, while your new subscription to The New York Review of Books will begin immediately.

June 30, 2022

A Laborer Called a Writer: On Leonard Cohen

Mount Baldy in clouds. Photograph by josephmachine. Licensed under CC0 4.0.

To mark the appearance of Leonard Cohen’s “Begin Again” in our Summer issue, we’re publishing a series of short reflections on his life and work.

On “Tower of Song” (1988), Leonard Cohen’s weary croak cracks the joke: “I was born like this / I had no choice / I was born with the gift of a golden voice.” He can’t quite sustain his own melody, but some of us remain enchanted—and not merely by his self-effacement. The irony, we suspect, involves us, too. Choicelessness is one of his great themes: we don’t choose our blessings or our deficits, and we don’t choose our material conditions. Fine. But Leonard Cohen takes it further: maybe we can’t even control the impulse to defy our deficits, to work against the grain of what we’ve been given. We feel sentenced to sing even without a golden voice—by our own unruly desires, or by “twenty-seven angels from the great beyond.” The metaphorical cause matters less than the effect: “They tied me to this table right here in the Tower of Song.”

Leonard Cohen came to music late, at least compared to his countercultural contemporaries. Bob Dylan was twenty-one when he released his first album; Leonard Cohen was thirty-three. He struggled to adapt his literary strategies to the new form. Even before his baritone stiffened with age, there was something workmanlike in his sensuous, spiritual, serious songs—not just in his delivery, but in his compositional structure, his preference for the heavy-handed end rhyme. Park / dark. Alone / stone. Pinned / sin. Soon / moon. He never made much use of slant rhyme, syncopation, or any of the sinuous tricks of great vocalists from the blues tradition. The second verse of “Tonight Will Be Fine” (1969) seems to describe the monastic simplicity of his compositions: “I choose the rooms that I live in with care / The windows are small and the walls almost bare / There’s only one bed and there’s only one prayer / I listen all night for your step on the stair.” For me, Leonard Cohen’s voice is that step on the stair—stumbling through the song’s tidy rooms, making the floorboards groan. His flatfooted rhythm makes wisdom’s weight hit harder.

I sometimes think of Leonard Cohen seated like a stone on Mount Baldy, where he became an actual monk in 1994 and where he lived for five years. I know a guy who studied at the same monastery. He would try to catch the singer stirring during morning meditation—even just breathing—but his stillness seemed absolute. This discipline frightens me, though it must have been hard-won. I like his songs because they let us overhear the rage and desire rattling discipline’s wooden frame: “I’m interested in things that contribute to my survival,” Cohen told David Remnick. He liked the Beatles just fine, but he needed Ray Charles. And I need Leonard Cohen—not the Zen master, but “this laborer called a writer” (his words) arduously working through a voice too plain for his own poetry. He keeps me company in the difficult silence between my own sentences. “I can hear him coughing all night long, / a hundred floors above me in the Tower of Song.” We’re both still straining—sweetly—for the music.

Carina del Valle Schorske is a literary translator and a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine. Her debut essay collection, The Other Island, is forthcoming from Riverhead.

June 29, 2022

Scenes from an Open Marriage

Illustration by Na Kim.

About six months after our daughter was born, my husband calmly set the idea on the table, like a decorative gun. I said I’d think about it.

I couldn’t pretend to be that surprised by the proposition, or ignorant of my part in engendering it. I was too tired. I was too busy. The baby the baby the baby. I had a deadline. I was reading. I was watching The Sopranos (again). I was depressed. I just wanted a nap, needed a nap, ached for a hot throbbing nap. This might, I figured, be “real” marriage, harder deeper marriage, marriage opening its cute mouth all the way and showing the mess that was back there.

Accidental iPhone video of forty minutes in the kitchen one night, a view of the cutting board and the wallpaper: You can hear a baby and the banging of something metal and you can hear our two adult bodies rustling around the space, running water, sliding a knife into the knife holder, dragging a chair across the wood floor, opening and closing the fridge―a sound like a breath and then nothing. We speak in short, muffled bursts, loving to her, not unloving to each other.

Maybe, I thought, the libido of a certain kind of woman is an animal that lives a little and then crawls into a cave and lies there panting for a few decades until, with a final ragged pant, it expires. Could it expire so early? Or perhaps it was taking a breather postpartum—understandable, surely, given how a six-and-a half-pound human body had been slither-pulled out of the place I get fucked, or one of the places.

And the child herself, coextensive with me at first and then tantalizing in her change, a body of mixed signals that consumed me and spared only meager scraps, like the dried bits of Play-Doh I sit among on the rug as I study a knee skinned for the very first time, knowing this leg will only get longer, thinner, and stranger to me. The way the legs grow is diabolical, absolutely no mercy.

Plus the drugs: Prozac’s gloved hand over libido’s mouth. For days and even weeks at a time I would forget there were such things as organs or pleasure or pleasure organs, like I was in the freezer, coldly buzzing on top of the dinosaur-shaped Broccoli Littles®. Until some lazy afternoon he would come into the bedroom while I was napping and wake me up and escort me through four shuddering orgasms and then, clearing his throat, go turn on the shower. Escort, what an odd verb to use.

***

What is there to want, after all? He is mine, sacredly, in sickness and in other states of being.

Except he is not, and his absolute, nonproprietary realness can flash out so suddenly that the spell of marital monotony is reversed and he becomes again a free man. Sometimes this happens when I see him from afar, struck by the full shape of him as if sighting a rare animal in the wild, or when I watch him playing the drums, the muscles in his neck twitching, the slight tilt of his head coinciding with the gulp of the kick, the ambush speed when he silences the cymbal. All of it stops when he senses I’m there.

That vision whereby one part of the man—shoulder, neck, wrist—seems all at once to radiate the whole of him can be so hot (loverly, worshipful) and so cold (clinical, dismembering), and in either case wifely. Spouses do chop each other into pieces, fashion new forms and uses for each other. I have been, at various times, the villain (when I cheated), the home front (during his long stretches of touring), the critic at whose feet to lay new work. For my part, I may, at least for a few years, have made of my husband a shelter for my exhausted, heaving materials, a threshold beyond which a strong wind abruptly dies. If I had made him that, could sex with others somehow transform him back? “You and I have taken refuge in a hermetically sealed existence,” Johan says to Marianne as he prepares to leave her for his lover in Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. “The lack of oxygen has smothered us.”

Finally I asked my husband, “Which scenario endangers us more: you sleeping with other women, or you not sleeping with other women?” I told him to think about it, assess, and render a verdict; I would do whatever gave us the best chance.

***

Originally, the term open marriage referred to an arrangement that today we might just call marriage. In their 1972 runaway bestseller Open Marriage, the husband-and-wife team of anthropologists Nena and George O’Neill hyped a “new lifestyle,” defined in opposition to the claustrophobic fifties model with its enforced gender and sexual role-play (husband works, pays, and tops; wife housekeeps, mothers, and enjoys—per Freud’s prescription—exclusively vaginal orgasms). The new lifestyle included such radical possibilities as having friends of the opposite sex, sharing the responsibilities of parenthood, and “some mutual privacy.” Sexually open marriage, or SOM, made an appearance in a single chapter, as one option that might suit some open couples.

Equality in marriage being now assumed if rarely achieved, the qualifier open has resumed its primary sense of “enterable by outsiders,” or the more degenerate-sounding “pervious.” (It strikes me that sex, marriage, and procreation intrinsically imply an escalating perviousness—will you let another in? Having let them in, will the two of you accommodate a third, or more?) The elusive feminist promise of the seventies model would seem to have carried over into today’s concept of open marriage. But there are different kinds of liberation. The kind I stood to gain at first felt shamefully backward, which only increased its illicit appeal: openness might offer deliverance not only for the restless, horny, lonely, or unsatisfied but also for the depressive working parent who has, as I hissed one night after another complaint about unmet needs, “absolutely nothing left for you.”

***

The first time, he came home boyish, whisper-laughing in the dark as he tore off his sweatshirt and climbed into bed. He used the word fun.

I had been waiting, braced for some seismic shift, but here he was home and mine again without so much as waking the baby. Just penis-vagina, I reminded myself. With people attached, though: My husband and someone else, moving deliberately, perhaps tenderly, in pursuit of each other and of a pleasure beyond … But: didn’t he deserve some compartment of his own, a chamber of mystery? Don’t we all?

I found I could be happy for my husband in his fun. More than happy, in fact. It can be a real thrill to let your partner go out, give it fully to another woman, and then come home and look you in the eyes over that, kiss you deeply and touch you over that. It is romantic in a way that culturally underscripted moments often are.

***

Once, before we were parents, a maroon sedan T-boned us at an intersection, going about thirty miles per hour. We flipped twice and skidded upside down for a small eternity, he said my name, I answered, hanging there, groping for his hand in the inverted space. “Be careful when you undo your seatbelt,” he said. I nodded, then pressed the release and dropped like a diver, face smacking dashboard. We laughed hysterically as we scrambled out the broken windows, and for hours afterward we were elated, marveling at each other’s unbroken bodies.

The inherent risk of open marriage is exhilarating. Nothing reifies a romance like proximate disaster. In fact, ours began when, at seventeen, we went home together from the funeral of a mutual friend who had been on American Airlines Flight 11. (The city was covered in ash that fall, and for us city kids there was a strong buddy-system vibe, like, Everyone quick grab your buddy, this is not a drill.) I still think of that friend whenever I’m traveling alone and the plane leaves the ground. I think of my husband at these times too, imagine him mourning me, review our parting words or final text exchange: “Cool,” “Coming,” “Can you look on the floor in the front seat?”

***

Last month I attended a funeral on my own. Afterward I went with a group of friends and acquaintances to a divey bar nearby. There were six of us, all women, all thirtysomething, four married with children, one simply married, one single. We packed ourselves in on two sides of a picnic table out back. The mood was giddily beleaguered; sudden death made our lives briefly thrilling and ridiculous.

As the third round of drinks arrived, the woman across from me said with a laugh that she hardly ever had sex anymore. “Oh yeah,” came a voice from farther down the bench, “we haven’t since H. was born.” A third agreed that sex was barely a thing lately. Reflexively I joined the rush to wrap the initial confession in assurances. Even the married woman without kids seemed, in her looks and noises, to allow that some lessening was inevitable after a while (or else, outnumbered by new and newish mothers, she just knew her audience). Only the single woman, who listened wide-eyed and wavering in the Schadenfreude exurbs of concerned alarm, was left to insist on the value of frequent, high-quality fucking.

With any question of private behavior, one tends to find the confirmation one goes looking for. I have no data from the other long-partnered women, some of them mothers, who attended the funeral but opted not to join us at the bar. (The black-box privacy of a “closed” marriage can be its own kind of intimacy, an unassailable communion not unlike sex, perhaps.) “We have an early morning,” said one woman, squeezing my hand, and her family retracted into its protective case.

***

A few months into our arrangement, while my husband was on tour in Europe, I noticed a new playlist on his Spotify and put it on in the car, quiet enough not to wake my daughter. I knew right away: the songs were too expressive of his core taste to have been thrown together for his own casual listening or for a group. The sensation was disorienting. I opened a window, letting the noise of the highway roar against the beat of a great love song, a song we’d danced to at our wedding.

Then came righteousness—our child in the back seat; self-pity, as a casualty of the great hurtling, impersonal male drive; the urge to drive through the discomfort, speed past it, newly self-reliant in my wound … though, of course, he was only doing what I had given him explicit permission to do. The woundedness felt strangely romantic; I was excited to confront him. Perhaps this was simply another woman’s bid driving up his price.

I have heard the argument that true intimacy cannot exist where one partner is having any significant, preoccupying experience from which the other is excluded. Maybe there’s something to that. Then again, people find all kinds of ways to be preoccupied.

On the phone, when I asked my husband about the woman for whom he’d made the playlist, I had to concede that if his love—or his preoccupation—was developing toward this new person, it was not noticeably being withdrawn from me. Where was it coming from, then? Maybe it was being spontaneously created, generated as a song generates pleasure, without diminishing anything else.

***

I did and do worry, especially about the younger girls, in their twenties. Were they all right, these kids? How did they feel about being “on the side”? Occasionally I stumbled into something like outrage on their behalf, as though I were the spirited friend in their drama: “Fuck that guy!” Weren’t they being exploited? In fact, wasn’t I exploiting them, outsourcing the labor of care, pleasure, attention, affirmation to this scattered, precarious workforce? How sinister, in this light, those nights my husband and I spent scrolling through the faces of sexual supply, our ethic blatantly consumerist, collecting primary and vicarious thrills that redounded to our own marriage, strengthening our family through the efforts and maybe even the pain of others …

These women would probably smirk at my anxiety for them, feel insulted by it. After all, they were out there making choices, getting into compelling snares, pleasing themselves. What was troubling me most, I suspected, was that among the squatting archetypes I’d been discovering in myself—the wronged wife (righteous, sympathetic, a bit tiresome); the “don’t ask” wife (practical, family-oriented, nobly incurious); the mother of a girl (protective of these youngsters wasting their time on a married man)—was the complacently cucked wife, shoring up the patriarchy for her own convenience. My husband’s extramarital activity was (and is) convenient. His date nights gave me much that I had yearned for, lusted after: relief from the distraction of guilt, space and solitude, time to write.

Maybe this was my erotic life now, these late-night vigils at my laptop, hitting a joint just until the spectating bitch-self got stupid, then taking some notes, wolfing popcorn and smearing butter on the keys, testing the rhythm of a line, the pressure of a word in that spot, seeing how it felt, right there.

But words are words and flesh is flesh, its phantom vibrations notifying me every now and then, and I needed to act out, make some other use of my freedom.

***

“When people meet on an open market,” Eva Illouz writes in The End of Love, “they do it using scripts of exchange, time efficiency, hedonic calculus, and a comparative mindset.” The dating app rewards a comfort and facility with choice, perhaps not the strong suit of the long-partnered. Choice can be humiliating, time-consuming, and cruel. Leave, stay, leave, leave, stay, and when you decide against someone, based on the angle of a tooth or on a popped collar or eerie lighting, the face disappears like a frisbee into the night.

“What about this guy?” my husband said one evening from the couch, swiping through men on my phone. Our daughter was on the rug fitting shapes into shape holes, a CNN anchor enunciating severely over her head. I had just got home from work and showered. It was raining hard and I didn’t feel like going out again, but I came over in my towel to look.

The man had sent a message: Hey there  . In the first picture you could see his whole body. He was leaning up against a wall, shirtless, wiry but with a hint of muscle, the waistband of his ratty jeans slung just low enough to show the hollows framing his groin, a cigarette hanging from his hand. Above his squinting eyes his hair was dark and messily buzzed. The second picture made for a jarring transition: his face filled almost the entire frame; his hair, now curly and possibly wet(?), looked longer and lighter, and his eyes were startlingly blue. There was something cheesy about how blue they were, and about the way he was looking into his own phone as though it were a person he was exaggeratedly listening to. These were the only two pictures of the man, too far away and too close, and I scrolled back and forth between them as though peering through a stereoscope.

. In the first picture you could see his whole body. He was leaning up against a wall, shirtless, wiry but with a hint of muscle, the waistband of his ratty jeans slung just low enough to show the hollows framing his groin, a cigarette hanging from his hand. Above his squinting eyes his hair was dark and messily buzzed. The second picture made for a jarring transition: his face filled almost the entire frame; his hair, now curly and possibly wet(?), looked longer and lighter, and his eyes were startlingly blue. There was something cheesy about how blue they were, and about the way he was looking into his own phone as though it were a person he was exaggeratedly listening to. These were the only two pictures of the man, too far away and too close, and I scrolled back and forth between them as though peering through a stereoscope.

Hi

How goes it?

It goes. You?

Yes it doesWhat ya up to?

My husband helped me dress. We settled on faded 501®s, a loose black shirt, Nike high-tops, and a teal trench with a hole in the seam. I was conscious while walking the few blocks to the bar of performing a purposeful stride. The man was standing in the rain holding a black umbrella whose canopy had slipped up to reveal one metal rib. I greeted him with a bro-y hug.

We ordered ginger ales and sat on low chairs by the bar’s front windows, talking about something—work, place of origin, who knows. Yoga came up and I said I hated it, hated staying still and breathing. I could tell he was weighing my pros and cons and I was doing the same for him. He was a good-looking man but there was a light in his eyes like he was spacing out during a firework.

I exerted myself to be charming. I had set out to play this game and I intended to score a goal. On the walk back to his place he smoked a cigarette and I smoked part of a joint. Getting high makes me panic, sex is one of the few things that helps, and creating a problem that only sex could solve eased my suspense. There was hardly any furniture in his condo—a futon, a coffee table, a speaker—and he explained he wasn’t really living there at the moment. The only book appeared to be a new copy of Oh, The Places You’ll Go! lying on the floor. Where was the man going? I got the vibe that he was dazed but in a deeply familiar way, like, Here I am again, dazed.

He was an excellent kisser, a lucky first toss. We started in on some slow, delirious motion. Springing merrily from his boxer briefs, the first nonhusband dick I’d met in a decade. Greetings, totemic power of random dick! (My husband would later ask about the size of it—what could I say, it was a beaut.) When I was naked the man pulled back to survey me, then brought his slightly unnerving eyes level with mine. He seemed to be seeing me for the first time, and I guess he was—seeing the part I’d brought to show, carrying it to the bar like a creature in a sheet-draped cage.

The experience was difficult to savor in the moment, but it lingered on, casting a glow. The next morning walking near Rockefeller Center I saw a pretty man and was instantly wet. I felt it with my husband, too, driving up the West Side Highway that week—a saturated, suspenseful energy, the warm wind pawing the hairs on my arm, the charged space between our bodies, his tensing jaw and tendons. A defamiliarizing layer of awareness stole over our lovemaking, a sense of trespass on the well-known body. One night in the dark I whispered into his mouth, You’re such a pervert. He whispered into my mouth, Does it turn you on to call me a pervert? I whispered into his mouth, Does it turn you on to ask me if it turns me on to call you—and before I could finish we were both rigid with laughter.

***

This morning M. is already in the kitchen when I come down, sitting by the window with her fresh black coffee and her mass of dark hair in a loose topknot. She looks peaceful, thoughtful, having not yet donned her high-energy persona. I get my tea and phone and sit across from her, and we share the words we’ve gotten in the Times Spelling Bee. Arrow, wallow, ardor.

M. has been coming to stay with us every few weeks since COVID began. Some nights, after my daughter is asleep, when my husband is working late or out on a date, M. and I will smoke a joint and play Bananagrams at the kitchen table, or we’ll bring the ashtray and some blankets and cookies to the couch and watch a stupid show, laughing at the outfits and canned dialogue. Or we’ll just talk, about articles, movies, my daughter’s development, how things are going with M.’s longtime boyfriend. I sometimes feel a little vampiric, trawling for narrative scraps about M.’s friends and their partners and parties and dramas—who has a secret crush, who has been modeling or hanging out with someone kinda famous, who got dumped or a new job or into graduate school.

If you ask M. about her future she may start to cry. “It’s just a physical response,” she says, and laughs. She’s at that age, twenty-five, twenty-six, when you begin to have a long memory of yourself. To me she is a bright, talented young woman on the brink of decisions and commitments that will consume her later years. To herself she is paralyzed, indecisive, falling behind. I try to argue the point but this only agitates her more, and then I remember how crazy it used to drive me, at her age, when my parents insisted on my value, my promise, my being “on track.” What offended me, I realize now, was the implication that I was not permitted to feel disappointed in myself. So now when M. expresses anxiety about her life, I don’t argue. I hope I can remember the lesson with my daughter, later on.

***

A few months prepandemic, my husband told me that E., a young woman he’d met on Tinder, had a guy friend who thought I was cute, and she wanted to set us up. I prodded for more detail. “You should ask her,” he said, and gave me E.’s number.

I had already decided, based on a few inches of her Insta grid, that E. was much more in command of the powers of her youth than I had been at her age. Good for her. My husband and E. had been seeing each other for a minute, and something about her put me on the alert. It wasn’t just that I could tell he genuinely cared for E.—that had happened before. It was more that E. had become real to me in a way none of the others had when she’d suggested M., her best friend, as a babysitter for our daughter. We liked M. immediately, and as I came to respect and trust her, E. gained a certain status in my eyes not just from my husband’s esteem but from M.’s.

E. replied to my text quickly, sharing her friend’s name and contact info.

And if this hot young manchild doesn’t do it for you I have more on retainer.

I said we should hang out sometime. She agreed. I was free right then, actually. Worked for her. I headed straight to the subway and rumbled along Myrtle Avenue. She met me at the door and led me up some dusty white steps, offered me tea. Her hair was bleached blond, her lips full, her cheeks pink as though from recent sleep. She had an aura of tentative but brave knowingness; her eyes seemed to make a point of neither darting around nor burning into me but just holding their ground with amused sympathy. My husband has great taste in women, I thought.

We sat at a small table and drank our tea, talked a little about books and about how great M. is, how thankful my husband and I were to have found someone like her to care for our child. E. was in a serious relationship with someone her own age, though not married or anywhere near it. I told her about the man with the Dr. Seuss book, how I had got lucky there but was wary of rolling the Tinder dice again. She advanced a seize-the-day attitude. I noticed my own attraction to her, the kind of rivalrous magnetism that is mostly just a desire to take a quick spin in someone, rifle through their memories, glimpse their face in the mirror. We chatted for maybe an hour, and as I was getting up to leave she came back to the subject of her guy friend.

When we reached the bottom of the stairs I turned and said, “He’s really too young for me. Don’t you think?”

She cocked her head. “Do I seem too young for your husband?”

I didn’t have to think about it. “No,” I said, and hugged her goodbye, smelling the familiar smell.

And the next thing you know I’m in a cab on the BQE, on the way to a blind date with E.’s friend, who is too young, I know he is, but I have agreed to meet him anyway because fuck you, no one is too young for me. I am out on a school night, a work night, I’m scooting across the slick leather of a cab again, I am fifteen, seventeen, nineteen, twenty-three, thirty-five—my age is a finite sequence happening all at once and here I go to meet this stranger. I might fuck this stranger, I might fuck him I might fuck him, and this potential fucking is both exciting and oppressive, the way it hovers in my thoughts, relentless, thrusting, threatening to shatter my very selfhood as I am about to become the stranger this young man is thinking he might fuck, I am about to become a fucking stranger.

***

I met E.’s friend in a dark, nearly empty bar. He was scruffy, a poet, and I liked talking to him. Again I smoked a joint on the way back to his place and once there we gave it the old college try. There was not only no chemistry between us but a kind of antichemistry, a lack of resistance so total that the physics of our bodies seemed to fail; instead of buttressing each other we kept yielding and collapsing like the flailing tube man at the car dealership. It may have been partly the weed, which hit me a little wrong this time, pinballed me into a solitary dimension. I was distracted by the docility I sensed in him, like he was ready to do whatever I commanded. Nonetheless we stuck it out right up to the point of imminent penetration, both of us naked on his mattress on the floor, a T-shirt thrown over the harsh bedside lamp. I tried to stay “in” it, but something kept disfiguring the scene, turning the bare, engorged boy on the mattress into a placidly obedient child. We got dressed and had a nice chat over tea.

With my husband and with M., I play the story of this date for laughs and am gratified when I get them. (Marriage might be the ideal place to process a bad sexual encounter with someone else.) To say that by now I’ve become close with M. doesn’t quite capture it—she has grown as dear to me as she is vital to the operation of my family. The cliché of falling in love with the nanny makes so much sense to me now. It does something to you to see a person devote themselves to your child, to see your child trust that person and enjoy their full attention. I love to see M.’s navy-blue scarf hanging in the entryway and to hear her turn her fist into a gruff-voiced character named Frumpkin at my daughter’s request. I love how generous she is with her laughter and how she sighs wistfully after a good laugh.

It’s a risky opening, letting an outsider into the role of parent. But a new kind of freedom emerges from these periods of open motherhood when M. visits. Her presence is miraculous, releasing me even as it solidifies my status, giving my daughter the opportunity to want me. I close my office door against her small crying body and hear M.’s bright, breathless voice calling her to finish a puzzle or come quick and see the deer out the window, and after a pause I hear the small feet go running.

***

The new woman’s piney smell comes home on the neatly folded hand-me-downs she sends back with my husband, from her child to mine. As a rival I find her formidable in an unfamiliar way. A single mother’s time seems particularly dangerous to waste; she must plan ahead, must not be kept waiting or canceled on at the last minute. I have seen a picture of her son, his tangled dark hair framing a dreamy frown, and have allowed my daughter to go on playdates with him. My husband and I discuss the situation as we unload the dishwasher. Where is the relationship going? How does this other child fit in? Openness has placed his mother and me in this tender, fanged relation; I wish her well, but when it comes to the distribution of something finite—my husband’s ultimate loyalty—one of us is going to lose.

One March evening we are approaching a restaurant, our daughter in my arms, and my husband says quietly, “She’s here.” Entering the crowded room, I know her by her child—that face, which in my mind has become mildly accusatory, and those dangling sneakers, blue with a red stripe just like the ones handed down to us. As we walk past the row of tables arranged along the western-facing window I take in, peripherally, an attractive man sitting next to the child, his mouth moving in the sunset glare, and, closer to me, inches from my arm, her ponytail of thick, dark, wavy hair, unmoving as I pass.

We meet our friends at a table a few yards southeast of the ponytail, which burns behind me but I do not turn. Someone has brought crayons and paper for the kids. What are you drawing? A house? I read somewhere that you should not say, What a beautiful drawing, or, I love your drawing, but rather something specific and affirming of the child’s will: You gave your house a big green door.

The drinks arrive. I sense, to my left, the alertness of my husband’s body, a certain buoyancy in his laughter, and I wonder if her presence and mine together have sharpened his reality, made him feel honored in some way. He does seem special to me at this moment—a man to know. It is as if the cord running between him and me, strong but a little slack, has been snapped taut by a third force, the ponytail.

My daughter needs to go to the bathroom, which is near the restaurant’s entrance. My husband rises, leading her, and I follow them. The ponytail turns and belongs to a woman whose expression is shy and warm—I extend my hand to her and she reaches up to embrace me. Later, after dinner, as our children chase each other shrieking around a planter out front, I watch her hugging herself and laughing in the cold. She is very beautiful, a beauty I feel both disarmed and affirmed by, as though I have brought a new friend home and she has won over the whole gang. I owe her something, but it is not yet clear what, and this makes me nervous—to care in this eager, unresolving way about someone I don’t know. Not like falling in love, but not entirely unlike it.

***

Lately my daughter and I keep getting locked in standoffs. I am saying Don’t do it and she is doing it, watching me expectantly at first as though to confirm a hypothesis, then with mounting rage, and I am trying to remember to use the language from the book (“I can see you’re really upset”) even though my instinct is to impose consequences, demonstrate who has the power, because fuck the book, the words from the book aren’t having any effect, I am trying them in every kind of cadence with every variation of emphasis (“I don’t like it when you hit me”) but they are broken and as a result I am broken, jammed, and just like my daughter I am doing the thing and doing the thing and doing the thing, and then I am yelling and she is yelling and there is one of me and one of her and we both want reunion and separation at once and the only answer is no. In these moments we need an interruption from outside—M. is that benevolent figure passing through, caring for us without making any promises. After all, M. will not be our nanny forever, just as E. has not remained my husband’s lover.

Here’s another scene: My husband and daughter and me in the car, parked at the station, waiting for M. We hear the rush of the train, the opening of the doors, the distant announcer’s voice. Various strangers emerge in masks, greet their rides, depart. Suddenly I hear my daughter singing M.’s name, my husband’s window humming down as he calls out to her, and, catching sight of the familiar baseball hat pulled low over the messy curls, I feel the approach of the world itself, coming to puncture the seal, let in some light and air.

Jean Garnett is a senior editor at Little, Brown and Company. Her work has been published in The Yale Review, and she is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize.

June 28, 2022

The Other Side of Pleasure: On Leonard Cohen

Photo copyright gudenkoa, via Adobe Stock.

To mark the appearance of Leonard Cohen’s “Begin Again” in our Summer issue, we’re publishing a series of short reflections on his life and work.

If apocalypse were at hand, would you choose to light a seventy-dollar Bois Cire scented candle by your bed and leaf through a Penguin Classics copy of George Herbert’s The Temple as the air conditioner ran on high, “Who By Fire” playing softly on your phone, the world slowly sifting itself down to ash? Some of us might. Some of us would. Leonard Cohen embraced the spiritual and the carnal, and his aching insistence on chasing pleasure at the edges of oblivion has made his voice ever more seductive—comforting, troubling—since his death in 2016.

That we are now at the edge of several oblivions needs no elaboration. The question of pleasure remains—what we might do with it, since we are all but numb to spectacular shock, and whether it can or should be comforting. I first heard Jeff Buckley’s version of “Hallelujah” as a teenager, before I heard Cohen’s original. At the time I preferred the cover; its beauty was immediate, seamless, intoxicating. But over time I’ve come to love Cohen’s churchly lounge act for the opposite reasons. There’s something uncanny in the synthetic sheen and gravel of Cohen’s track—a self-negating camp performance of spiritual grandeur that erases the line between rapture and sleaze.

And on the other side of pleasure—a luxury candle, poetry, air-conditioning—there is often both rapture and sleaze: tender depravity. How much of it are we willing to accept? A lot, maybe. While there’s a time for the sensuous charms of “Suzanne” and “So Long, Marianne,” I’ve always been drawn to the songs in which Cohen allowed himself to sound unhinged. In “Diamonds in the Mine” he is an unlikely vector of proto-punk rage, particularly at the end, as he genuinely screams his way through the final refrain—“And there are no letters in the mailbox / And there are no grapes upon the vine”—in an atonal vocal shred, his unfazed backup singers hoisting up the chorus’s sunny melody behind him, a spring breeze blowing through a nuclear meltdown. Amid the decadent, Oedipal party music of “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On,” he snarls, “It will only drive you insane / You can’t shake it or break it with your Motown / You can’t melt it down in the rain”—a meltdown of a different order.

He was fatalistic, but he wasn’t a nihilist. In a Leonard Cohen song pleasure comes at a price. In “Tower of Song,” he sings, “You can say I have grown bitter, but of this you may be sure / The rich have got their channels in the bedrooms of the poor / And there’s a mighty judgment coming—but I may be wrong.” You paid seventy dollars for that candle; you may as well take a big whiff as you burn it down. There is pleasure of the spirit and pleasure of the flesh, and here on Earth they are forever intertwined. Is that comforting? “You want it darker,” he intones on his final album, released just weeks before his death, “we kill the flame.” He is blowing out the candle and crooning us into the abyss as we try, in our way, to be free.

Daniel Poppick is the author of the National Poetry Series winner Fear of Description and of The Police.

Marilyn the Poet

Monroe in Don’t Bother to Knock (1952), from the July 1953 issue of Modern Screen.

“It’s good they told me what / the moon was when I was a child,” reads a line from a poem by Marilyn Monroe. “It’s better they told me as a child what it was / for I could not understand it now.” The untitled poem, narrating a nighttime taxi ride in Manhattan, flits between the cityscape, a view of the East River, and, across it, the neon Pepsi-Cola sign, though, she tells us, “I am not looking at these things. / I am looking for my lover.” The very real moon comes to symbolize the confusion of adult experience. I quote these lines back to myself when I feel acutely that I understand less, not more, than I used to.

The poet Marilyn was the first Marilyn I encountered. Like her when she was young, I lived in a strict Pentecostal environment that forbade much of pop culture, but unlike her, I didn’t gorge myself on movies after escaping the prohibition. Although I had heard of “Marilyn Monroe,” I hadn’t yet happened to see any of her films when I came across Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters by Marilyn Monroe in a bookstore. I, like so many, fell for the allure—still, to me, a forbidden one—of her image: Marilyn on a sofa seemingly caught looking up and away from the black notebook in her lap. Her expression suggests she hasn’t yet decided whether the distraction is a source of apprehension or delight. Wearing coral lipstick and a black turtleneck, she is beautiful and bookish. The apparently candid photo is actually from a 1953 series for Life by the photojournalist Alfred Eisenstaedt. Then twenty-six, Marilyn was famous, and only becoming more so: she’d started dating the baseball star Joe DiMaggio. The revelation that years before she’d posed nude for a calendar (and wasn’t ashamed) had recently scandalized McCarthyite America. Life’s portraits of a sex symbol among books play to an audience’s wish to condescend to the object of their desire, to laugh at the “dumb blond” who thinks she can read. (Desire, after all, is an involuntary subjection often trailed by resentment.) As always, Marilyn insisted on approving the images; the contact sheets show her red pen. And in this photo, whatever anyone else intended, I also see her considered self-creation.

Marilyn’s poems are, as the book’s title indicates, mostly fragmentary. Rarely (if ever) did a first draft become a second, but themes and motifs recur as though being reworked. They were written in notebooks and on scrap paper alongside lines of dialogue from her films, song titles, lists, outpourings of anxiety, and accounts of both real events and dreams. Sometimes lines that read like poems actually aren’t, as with some of the notes made during her years spent in psychoanalysis and in classes with Lee Strasberg, a controversial proponent of the “Method,” a technique that demands actors dig deep into their emotions and memories in order to fully inhabit their roles. Some of Marilyn’s pages are tidily penned, starting precisely at the red vertical margin, but often the poems and notes range across or even around the page, with words crossed out and sentences connected by arrows. Because the lines often end where the paper does, it’s not always obvious where they break, or whether they should break at all. According to Norman Rosten, a poet who became better known for being a friend of hers, “She had the instinct and reflexes of the poet, but she lacked the control.”

Marilyn left high school when she married her first husband and, aside from a continuing-education course in literature at UCLA, never had further formal education. But she was a committed if haphazard autodidact, going to a now-defunct bookstore in Los Angeles to leaf through and buy whatever books interested her (Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, for instance). Although the playwright Arthur Miller, her third husband, claimed she never finished anything “with the possible exception of Colette’s Chéri and a few short stories,” others contradict this. She professed a love for The Brothers Karamazov and a wish to play its central female character, Grushenka. Her library contained more than four hundred books, including verse collections by D. H. Lawrence, Emily Dickinson, and Yuan Mei, and an anthology of African American poetry.

Insecure about her lack of formal education, Marilyn nonetheless resented being seen as stupid. She complained that some of Miller’s intellectual friends “treated me like a dull little sex object with no brains and talked to me like a high school principal with a backward student.” I am inclined to think she did read rather more than they thought, if only because her writings suggest an attunement to poetry that goes beyond instinct—that can only be learned by listening, so to speak. Yes, her choice of line often seems naïve, her images are sometimes clichéd, but in places something flares, that strangeness I associate with poetry that feels open rather than finished before it begins. It is the kind of poetry that risks failing to go anywhere at all but, when it succeeds, surprises the reader, and the poet, too.

***

When I moved from New York City to Poland in 2016, I packed most of my books—slightly more than four hundred, in my case, as in Marilyn’s—into storage. Among the relatively few books that crossed the Atlantic with me was Fragments. It wasn’t useful to my research, and it wasn’t especially portable. But every so often I wanted to flip through Marilyn’s thoughts. Every so often, too, I wanted to revisit the two poems that struck me, coup de foudre style. In my first Warsaw apartment, she leaned against a copy of Madame Bovary (also in Marilyn’s library) in French, left by the previous tenant.

The first of those two poems I loved so much dramatizes the suicidal mind’s attempt to solve the problem of how to die. In her handwriting, it looks like a prose poem:

Oh damn I wish that I were dead—absolutely nonexistent—gone away from here—from everywhere but how would I—There is always bridges—the Brooklyn Bridge—But I love that bridge (everything is beautiful from there and the air is so clean) walking it seems peaceful even with all those cars going crazy underneath. So it would have be some other bridge an ugly one and with no view—except I like in particular all bridges—there’s something about them and besides I’ve never seen an ugly bridge.

The poem is a frantic rush from the very beginning. Seeking a method for dying, the poet happens upon the thing that will keep her living: the bridge, which becomes an existential problem—or, rather, a problem that will preserve existence. After ruling out the Brooklyn Bridge, with darkly comic pragmatism she decides on “some other” bridge. But her focus on the details of this world has turned her too far back toward living. By the end, we don’t know if the desire to die has been vanquished, but we see that the action has been thwarted by wry practicality and the world’s ordinary loveliness. She’s telling the truth, or a truth: sometimes it is only the fact that “there’s something about” bridges that keeps us from jumping off them.

It’s natural to connect the poem’s preoccupation with Marilyn’s known depressive episodes (“I tried it once,” she said, meaning suicide, to the journalist William J. Weatherby, “and I was kind of disappointed it didn’t work.”) But another reason for her, at least occasionally, to wish for nonexistence might have been her experience of hypervisibility. “When I was a kid, the world often seemed a pretty grim place,” she told Weatherby. “I loved to escape through games and make-believe. You can do that even better as an actress, but sometimes it seems you escape altogether and people never let you come back.” The complaint about celebrity is more complicated than it first seems: for Marilyn, the trap of fame is not just immurement. Rather, when the path of escape reveals itself as a dead end, she finds the way back garrisoned.

The one good line in Arthur Miller’s dull, self-serving memoir describes Marilyn as “a poet on a street corner trying to recite to a crowd pulling at her clothes.” His metaphor echoes, perhaps intentionally, the time when frenzied fans at an airport tore at Marilyn’s clothes and hair until guards intervened. When I first read this, the image that lingered was the “poet on a street corner.” Only on a subsequent reading did I take in the violence that follows the lyric.

***

Life—

I am of both your directions

Somehow remain hanging downward

the most

but strong as a cobweb in the

wind—I exist more with the cold glistening frost.

But my beaded rays have the colors I’ve

seen in a painting—ah life they

have cheated you

This is one of Marilyn’s most striking poems, and my favorite. The bold apostrophe followed by the emphatic dash—both reminiscent of Emily Dickinson—immediately endows the poem with a potentially ritual significance, evoking the abstraction of “life” as a possible interlocutor, at least within the slim space of the poem. Direct address to inanimate forces, as Jonathan Culler notes in Theory of the Lyric, hardly exists outside of poetry and connects the person who employs it to the poetic tradition, “as if each address to winds, flowers, mountains, gods, beloveds, were a repetition of earlier poetic calls.” It also risks being ridiculous, given that we know that the called upon cannot, in fact, call back. Will we—can we—allow the poet such a power? Marilyn, intriguingly, does not ask anything of Life: this is not prayer but description. Ostensibly, she just wants to tell Life about herself.

Life’s two directions, it seems, are up and down, not, as one might expect, forward or backward. Marilyn figures “life” as a polar condition, the person suspended between like a taut rope, tugged toward—we can guess—either happiness or sorrow. (“Hanging downward” clearly gestures to suicide.) The “but” that introduces the cobweb’s strength indicates that a flimsy appearance may be deceptive; it also builds in ironic possibility. Perhaps the whole clause is a joke. Perhaps such strength is the act of resistance rather than a state of solidity. The “I” may be just barely hanging on.

The tension will stay unresolved. The poem moves toward its conclusion via another “but,” a contradiction that isn’t one at all. It’s a revision of focus. Abandoning questions of strength, we turn toward beauty: the beauty claimed by the self is—surprisingly—the beauty of art, even though the self, still pictured as a cobweb, remains a part of nature.