The Paris Review's Blog, page 75

August 24, 2022

Against August

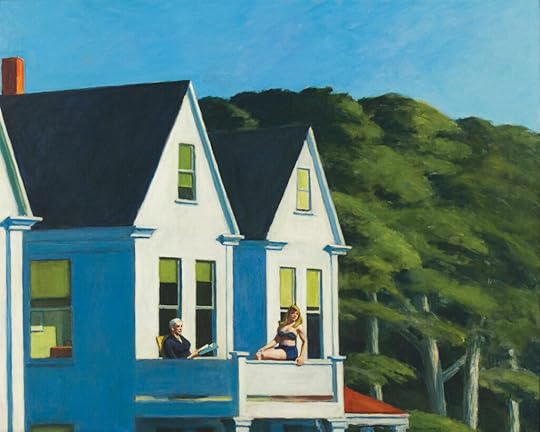

Edward Hopper, Second Story Sunlight, 1960.

There is something off about August. This part of the summer season brings about an atmospheric unease. The long light stops feeling languorous and starts to seem like it’s just a way of putting off the night. There is no position of the earth in relation to the sun that comes as a relief. Insomnia arrives in August; bedsheets become heavy under humidity. No good habits are possible in August, much less good decisions. All I do is think about my outfits and my commute, constantly trying to choose between my sweatiness and my vanity. People are not themselves. I go see the party girls and find them wistful. I meet up with the melancholics and find them wanting to stay out all night.

In August I cannot think, so I cannot work. This is not not-working in a restful or decadent way. This is not-working as certain doom. And I can’t not-work in peace either: if I leave in July I consider myself traveling but if I leave in August I am just leaving. The best I can hope for, in the absence of a purpose like business or pleasure, is an escape. Maybe a light excursion. In any case I am rarely in the place I can reasonably call my home in August, and instead stay in other people’s basements, in their living rooms, on their couches. I sleep on what was once a little brother’s bunk bed and wash my hair in his parents’ shower. I walk down the stairs and see their children’s fingerprint smudges on the banister. I stay in hotel rooms by myself and think: What a waste. (I am convinced that hotel rooms are designed for sex, even though I am not particularly into the quality they have—sealed, hermetic, identical. Hotels are to sex what time zones are to jet lag, I think. A change of interiors out of proportion with the body.)

I am against August. When I try to explain this position, some people instinctively want to argue. These people seem to love the beach beyond all reason, to have never suffered a yellowed pit stain on a favorite white T-shirt in their life, and to eagerly welcome all thirty-one days of August as though they are a reward for a year well-lived rather than a final trial before the beginning of another. These are people who vacation with peace of mind. To them, I say: Go away. To the people who agree with me, I say: Go on.

Many friends who share my malaise compare the experience of the month to the Sunday feeling of knowing work or routine is imminent after a break. I don’t agree exactly, but I recognize the comparison. In August summer ends, and so whether or not you are done with it you must accept that it is finished. Everything you meant to say or do now exists in the past tense: it was said or it wasn’t, it was completed or never even begun. The month does function, I will admit, as an excellent excuse. I reassure myself and others about mistakes or failures with promises of what we’ll be like in September. Any accomplishment, no matter how minor, is astounding to me: In August?! I think.

***

I note references to August when I find them, and keep them as though I am preparing a defense of my position. I must have my rhetoric for when pettiness alone fails me. There are, of course, many who have romanticized August in art. In Emily of New Moon, L. M. Montgomery describes a vacation spent in “the long, smoky, delicious August evenings when the white moths sailed over the tansy plantation and the golden twilight faded into dusk and purple over the green slopes beyond and fireflies lighted their goblin torches by the pond.” I probably read that for the first time as a child indoors, while hiding from an August unlike the one she had written about. I have never experienced this delicious smoky August that looms large in our cultural imagination; instead of white moths, for me, there are mosquitoes.

Some poets agree with me, some don’t. I am always on the lookout for allies. Marge Piercy’s 1984 poem “Blue Tuesday in August” begins:

The world smelled like a mattress you find

on the street and leave there,

or like a humid house reciting yesterday’s

dinner menu and the day before’s.

Like that, yes. “In an invented summer,” wrote Etel Adnan in Sea and Fog, “the world breaks apart … Love is wedded to time, and revelation is their breaking apart. In one of August’s sizzling days, the sea swallowed a woman whose flesh gave up resistance.” Also just like that, yes. In Mary Oliver’s 1983 poem “August,” she writes that she is

cramming

the black honey of summer

into my mouth; all day my body

accepts what it is.

Hmm. “What I want,” writes Kim Addonzio in her poem called “August,” “is to slice open its stomach and watch / its toxic sun uncoil into the sea.” Yes, that’s better. “August rain: the best of the summer gone, and the new fall not yet born,” wrote Sylvia Plath in her journals. “The odd uneven time.” Another entry:

Today is the first of August. It is hot, steamy and wet. It is raining. I am tempted to write a poem. But I remember what it said on one rejection slip: “After a heavy rainfall, poems titled ‘Rain’ pour in from across the nation.”

Many experience it with a sense of finality. “The summer ended,” writes James Baldwin in Just Above My Head:

Day by day, and taking its time, the summer ended. The noises in the street began to change, diminish, voices became fewer, the music sparse … The houses stared down a bitter landscape, seeming, not without bitterness, to have resolved to endure another year.

Then there are movies set in August, many defined by catastrophe: August 5 is the day Do the Right Thing takes place; August 29 is the day, according to Terminator 2, the world ends. And there are the movies I believe should be watched in August because they capture something of its claustrophobia (Rear Window, The Talented Mr. Ripley). There are the heroines of Rohmer’s films, undone by the pressures of vacationing alone and the vacuousness of beach holidays.

The Hottest August, Brett Story’s documentary filmed in 2017, has a title that is inherently ominous and incomplete—after all, it shows what is the hottest August only thus far. She interviews people in the various boroughs of New York in front of their homes, in their favorite bars, in parks, on beaches. Each scene has a sense of foregrounding: there are layers between the viewer and her subjects, like sandcastles in front of the water, that both direct and obscure your line of vision.

August Is a Wicked Month by Edna O’Brien begins with a description of the weather as evil incarnate. “People who had hoped for summer wished now for a breeze and a little respite.” Ellen, O’Brien’s tragic heroine, will get neither, no matter how hard she tries. Her marriage is about to end and she goes on a vacation, throws her wedding ring into the ocean, and doesn’t regret it. Even after a true tragedy she finds it hard to return home. It is difficult for Ellen to decide, while grieving, if the month is wicked or if it holds “her own pathetic struggles towards wickedness.” She feels too much, finally, to feel anything at all. “It was a new sensation, indifference,” she thinks. “It was like observing a party as one passed by a sleek and softly lit front room and having no feeling of regret about being uninvited because to walk the streets alone provided a greater and surer pleasure.”

***

In August of the only year I was married, we flew to the West Coast of Canada for a wedding. I was distracted; I didn’t plan. Not understanding either Canada’s geography or its seasons, I had packed for what I considered to be August weather. I spent the entire time cold and cursing myself for the missed opportunity to wear sweaters and jackets. The dress I brought was too big, and so were my shoes. But it was a beautiful wedding. I guess they all are. The bride’s father, a carpenter, made the pews for the ceremony and the tables and chairs for the reception. The sun was on the water and we traded blankets back and forth when the wind blew. At night we drank, and cried. I had already said goodbye to these friends so many times before; when I had moved, when I came back to visit, and now I would again, before getting on a plane to fly to a different city than the one we’d grown up in together. “It doesn’t get easier,” one friend said through his tears. I held my hand on his cheek without wiping them away.

Back in New York the season was what I’d expected and dreaded. Airless, choking heat, sunlight that seemed to burn without warmth. Steam lifted off the sidewalk. The hours were slow but gone before I could count them. The feeling of August was as uncomfortable as the weather. Enough time had passed to know how I would remember this summer. There was still enough time to convince myself the future might prove me wrong. I read the letters that writers I loved had written to the people they loved, and circled the passages that felt important even if I couldn’t say why. One I kept with me for a long time, waiting to understand how I knew what it meant. On August 12, 1971, Elizabeth Hardwick had written to Robert Lowell:

I have had a really fine summer, strange in many ways, in others exactly the same. In the afternoons the light drops suddenly, the day waits and you feel a melancholy repetition, as though you were living moments before, maybe long ago by someone else.

In September she wrote to say that she had started divorce proceedings.

***

Now I am alone when I leave town in August. I remember one night spent solo at a bar someone had recommended, with a patio with a view that I knew I should see. Behind it the sky was almost-thunderstorm purple. I thought the canopies over the patio would protect us from the rain, but they were, it turned out, mostly for decoration. Half the people scattered under columns supporting a slim roof; the other half clustered around the bar. All of us kept our hands around the stem of our wineglasses. I sat on the stoop with a man, close to the columns. I could see feet poking out and tried to lean over to see who they belonged to, what they thought of the rain. We made eye contact but not conversation, so I lit a cigarette. The photos on the pack depicted the absolute limits of what can happen to a body. The man beside me watched a French comedian perform standup on his phone but didn’t laugh. When the rain stopped skateboarders arrived. I watched them for a while, then went to where I was staying and laid in bed, planning what else I could do in the morning. I pretended to sleep until I was bored and then I showered. Sometimes I forgot to be glad I was alone. I would daydream about bumping into someone I knew. Not a friend, exactly. Someone unlikely but not unwelcome to find in the same restaurant, café, or park. Someone also away from themselves in the month defined by absences.

Still, I don’t text people back. Instead I collect the oddities of the month I see and hear. I sit in the shade of a park beside the cigarette butts and a broken pair of sunglasses half-buried in the dirt. I sit in the sun at a baseball game in front of a man who, only half joking, heckles the other team: How dare you! How dare you try to win! On the way to the game I pass a woman on a patio talking about being too hot, about the ever-present light: It’s like, I get it, I know how the sun works. I walk behind a barber carrying a white bag sticky with pastry oils on his way back to work, a sparkling water and a half-drunk Gatorade in his hands, a tattoo on his neck in Gothic script that reads “In Fair Verona.” A phone call on the bus, a woman explaining to her friend that another person they knew had told her, She doesn’t need us anymore, she has new friends. A girl with pink barrettes holding her hair back from her face, her phone held to her ear, listening to whoever is on the other line with a smile she hasn’t yet realized she’s making. I sit outside the ice cream shop with my friend’s baby and golden retriever, waiting for her return. A man walking by gestures at us. Nice life.

He’s right. It is. There is much to enjoy about hating a month so completely. It would be romantic—except the only tension between us is the dread I feel as I anticipate August’s inevitable return. While I am drifting in the scorched grass under a tree, or hearing the sound of my legs sticking to the cheap plastic melting on a shadeless patio, or feeling my hair curl into a sweaty knot against my neck, I remember that I’ve known it would be exactly like this—that at least I did not exaggerate. As the month winds down, I can feel some sort of solace: after all, I’ll make it to after August.

Haley Mlotek is a writer based in Montreal. Her first book, about romance and divorce, is forthcoming from Viking.

August 23, 2022

Saturday Is the Rose of the Week

Clarice Lispector. Photo courtesy of Paulo Gurgel Valente.

In 1967, the Jornal do Brasil asked Clarice Lispector to write a Saturday newspaper column on any topic she wished. For nearly seven years she wrote weekly, covering a wide range of topics—humans and animals, bad dinner parties, the daily activities of her two sons—but the subject matter was often besides the point. These genre-defying missives are defined by a lyricism and strangeness that readers of her fiction will recognize, though they are a thing apart in their brevity and interiority. Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas, which collects these columns and others Lispector wrote throughout her career, will be published in English by New Directions this September. As Lispector’s son Paulo Gurgel Valente has written, “Enjoy the columns, I know of nothing quite like them.” Today, the Review is publishing a selection of these crônicas, the final installment in a series.

March 13, 1971

Animals (I)

Sometimes a shiver runs through me when I come into physical contact with animals, or even at the mere sight of them. I seem to have a certain fear and horror of those living beings that, though not human, share our instincts, although theirs are freer and less biddable. An animal never substitutes one thing for another, never sublimates as we are forced to do. And it moves, this living thing! It moves independently, by virtue of that nameless thing that is Life.

I remarked to someone that animals do not smile, and she told me that Bergson comments on this in his essay about laughter. While a dog does, I’m sure, sometimes laugh — its smile expressed by its eyes brightening, its half-open mouth panting, and its tail wagging — a cat never laughs. It does, however, know how to play. I have a lot of experience with cats. When I was small, I had a cat of a rather common sort, striped in various shades of gray, and cunning in that feline, distrustful, aggressive way cats are. My cat was continually having litters, and every time the same tragedy would unfold: I would want to keep all the kittens and turn the house into a cattery. Behind my back, the offspring were given away to goodness knows who, which made the problem still more acute because I wouldn’t stop complaining about the absent kittens. And then, one day while I was at school, they gave my cat away. I was so shocked I took to my bed with a fever. To console me they gave me a present of a cat made out of rags, which to me was ridiculous: how could an object that was dead and floppy and a “thing” ever replace the elasticity of a living cat?

Speaking of living cats, a friend of mine wants nothing more to do with cats. He got fed up with them for good after having a female cat that periodically went mad: her instincts were so strong, so imperative, that when she was in heat, after uttering long, plangent meows that echoed through the whole neighborhood, she would suddenly become half-hysterical and throw herself off the roof, injuring herself in the process. A servant to whom I told the story crossed herself and exclaimed, “Get thee behind me.”

Of the slow and dusty turtle carrying its stony shell, I would rather not say anything. This animal, which comes to us from the era of the dinosaurs, does not interest me: it is too stupid, it doesn’t engage with anyone, not even with itself. The act of lovemaking between two turtles must surely have neither warmth nor life. While not an expert, I venture to predict that a few millennia from now the species will come to an end.

Regarding chickens and their relationships with each other, with people, and above all with their gestation period, I have said all there is to say. I have also spoken about monkeys.

As an adult, I owned a mongrel that I bought from an ordinary woman I happened to meet in the hurly-burly of a Naples backstreet, because I sensed that he had been born to be mine, which, happily, he also sensed, immediately following me without a thought for his former owner — not even a backward glance—as he wagged his tail and licked me. But it’s a very long story, my life with that dog who had the face of a mischievous mulatto Brazilian despite being a born and bred Neapolitan, and to whom I gave the rather recherché name of Dilermando on account of his pretentious charm and his air of being some garrulous raconteur from the turn of the century. I could have many things to say about Dilermando. Our relationship was so close, his sensibility so akin to mine, that he anticipated and felt my difficulties. Whenever I was writing on the typewriter, he would position himself half-lying, half-sitting by my side, sphinxlike, dozing. If I stopped typing because I’d encountered an obstacle and become disheartened, he would immediately open his eyes, raise his head, and look at me with one ear cocked, waiting. Once I had resolved the problem and carried on typing, he would settle back into his somnolent state populated by goodness knows what dreams — because dogs do dream, I’ve seen it. No human being ever gave me the feeling of being loved so totally, the way I felt loved unreservedly by that dog.

After my sons were born and had grown a little, we gave them a very large and beautiful dog, who patiently let them take turns climbing onto his back and who, without anyone charging him with the task, kept guard over the house and street, waking up all the neighbors at night with his warning barks. I gave my sons little yellow chicks that followed close behind us, tripping us up, as if we were the mother hen; those tiny little things needed their mother just as humans do. I also gave them two rabbits, some ducks, and marmosets. The relationships between man and beast are unique, irreplaceable. Owning an animal is a vital experience. And anyone who has not lived with an animal lacks a certain intuition about the living world. Anyone who recoils at the sight of an animal clearly feels afraid of themselves.

But sometimes I do shudder on seeing an animal. Yes, at times I feel the mute ancestral cry within me when I am with them: it seems I no longer know which of us is the animal, me or the beast, and I get thoroughly confused; I become almost afraid of facing up to my own stifled instincts that, demanding as they are, I am obliged to assume when confronted by the animal. What else can we miserable creatures do? I once knew a woman who humanized animals, talking to them and lending them her own characteristics. But I don’t humanize animals, I think that’s offensive — we should respect their own natures. Instead I animalize myself. It isn’t difficult, it comes easily; just don’t fight it, just surrender.

But if I go deeper, I arrive very pensively at the conclusion that there is nothing more difficult than total surrender. This difficulty is one of our human afflictions.

Holding a little bird in the half-closed palm of your hand is terrible. Petrified, it beats its wings fast and frenetically; suddenly you have in your half-closed fist thousands of delicate wings thrashing and fluttering, and suddenly it all becomes unbearable and you open your hand to free the bird, or hand it back to its owner so that they can return it to the greater relative freedom of a cage. In short, I want to see birds flying or perched in trees—but far from my hands. Perhaps some day, in more sustained contact with Augusto Rodrigues’s birds at Largo do Boticário, I might become close to them, and enjoy their featherlight presence. (The phrase “enjoy their featherlight presence” gives me the sensation of having written a complete sentence by describing something exactly as it is. It’s a funny feeling; I don’t know whether I’m right or wrong, but that’s another problem.)

It would never occur to me to own an owl, but a little friend of mine found an owl chick on the ground in the Santa Teresa forest, all alone and without its mother. She took it home, kept it warm, fed it, whispered to it, and ended up discovering that it liked raw meat. Once it was strong enough, she expected it to fly off immediately, but it delayed going in search of its own destiny and rejoining its own kind: that strange bird had become attached to my little friend. Very reluctant to leave, it would fly a little way off and then come straight back. Until one day, as if after a long battle with itself, it seized its freedom and flew off into the depths of the world.

April 3, 1971

De Natura Florum

And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom He had formed.

—Genesis 2:8

Dictionary

Nectar : Sweet juice that many flowers contain and which insects seek avidly.

Pistil : Female organ of a flower. Generally occupies its center and contains the beginnings of the seed.

Pollen : Fertilizing powder, produced in the stamens and contained in the anthers.

Stamen : Male organ of a flower, made up of the style and the anther in its lower part surrounding the pistil, which, as set out above, is the flower’s female organ.

Fertilization : Union of two elements of reproduction (male and female), from which comes the fertile fruit.

Rose : The feminine flower; she gives herself so wholly and so generously that, for her, there remains only the joy of having given herself. Her perfume has a feminine mystery about it; if inhaled deeply, it touches the depths of the heart and leaves the body entirely perfumed. The way she opens out into a woman is exquisitely beautiful. Her petals taste good in the mouth: just try. Red roses, or the Black Prince variety, are enormously sensual. Yellow ones are alarmingly cheerful. White ones are peace. Pink ones are generally fleshier and their color is just perfect. Orange roses are sexually attractive.

Carnation : Has an aggressiveness that comes from a certain degree of irritation. The edges of its petals are sharp and snub-nosed. The carnation’s scent is somehow mortal. Red carnations bellow with violent beauty. White ones recall the little coffin of a dead child; their scent then turns pungent.

Sunflower: The great child of the Sun, so much so that it is born with the instinct to turn its enormous head toward its mother. Does it matter whether the Sun is the father or the mother? I don’t know. Is the sunflower female or male? Male, I think. But one thing is certain: the sunflower is Russian, probably Ukrainian.

Violet : Introverted, profoundly introspective. It doesn’t hide itself, as some would say, out of modesty. It hides in order to understand its own secret. Its scent is a glory but demands that we go in search of it: its scent says what cannot be said. A bunch of violets means, Love others as you love yourself.

Sempervivum : An ever-dead. Its aridity tends toward eternity. Its Greek name means golden sun.

Daisy : A cheerful little flower. Simple: it has only one layer of petals. Its yellow center is a childish plaything.

Palm : Has no scent. Shows itself off haughtily — for it is haughty — in form and color. It is frankly masculine.

Orchid : Beautiful, exquise, and unfriendly. Unspontaneous. In need of a glass dome. Yet it is a magnificent woman, this cannot be denied. It can also not be denied that it is noble; it is an epiphyte—that is, it is born on another plant without taking nutrition from it. I’m lying: I adore orchids.

Tulip: It’s only a tulip when in a large field covered by them, as in Holland. A single tulip simply isn’t.

Cornflower : Only grows among wheat. In its humility, it has the audacity to display itself in various forms and colors. The cornflower is biblical. In Spain it is used to decorate the Christmas crib, along with the sheaves of wheat from which it is inseparable.

Angelica: Has the scent of a chapel. It brings mystic ecstasy. It recalls the Host. Many wish to eat it and fill their mouths with its intense, sacred scent.

Jasmine : For lovers—they walk hand in hand swinging their arms, and exchange soft kisses, I would say, to the odorous murmur of jasmine.

Bird-of-paradise : Preeminently masculine. It has an aggressiveness grown out of love and healthy pride. It appears to have a coxcomb and, like the cockerel, it crows, but it doesn’t wait for dawn — when seen, it gives its visual cry of greeting to the world, for the world is in a constant state of sunrise.

Azaleia : Some people use other spellings, but I prefer this one. It is spiritual and bright: it is a happy flower and brings happiness. It is humbly beautiful. People who are called Azaleia — like my friend Azaleia — take on the qualities of the flower: it is a pure delight to be around them. I received from Azaleia many white azaleias that scented the whole room.

Night-blooming jasmine: Has the scent of the full moon. It is phantasmagorical and a little frightening—it only comes out at night, with its intoxicating smell, mysterious, silent. It belongs also to deserted street corners and darkness, to the gardens of houses with their lights turned off and their shutters closed. It is dangerous.

Cactus flower: The cactus flower is succulent, sometimes large, scented, and brightly colored: red, yellow, and white. It is a succulent revenge on behalf of all desert plants: it is splendor arising from despotic sterility.

Edelweiss : Found only at high altitudes, although never above eleven thousand feet. This Queen of the Alps, as it is also called, is the symbol of man’s conquest. It is white and woolly. Rarely attainable, it is a human aspiration.

Geranium : Flower of window boxes in Switzerland, São Paulo, and Grajaú. It has a sarcophyllum, i.e., a succulent, highly scented leaf.

Giant water lily : There are enormous ones in Rio’s botanical garden, almost seven feet in diameter. Aquatic and drop-dead gorgeous. They are the great Brazil, constantly evolving: on the first day white, then pink or even reddish. They spread a vast sense of tranquility. At once majestic and simple. Despite living on the water, they provide shade.

July 11, 1970

Saturday

I think Saturday is the rose of the week; on Saturday afternoon, the apartment is made of curtains blowing in the wind and someone emptying out a bucket of water on the terrace: Saturday in the wind is the rose of the week. Saturday morning is a garden, a bee flying past, and the wind: a beesting, my face swollen, blood and honey, the sting lost inside me: other bees will come sniffing around, and next Saturday morning I’ll go and see if the garden is full of bees. In my childhood Saturday gardens the ants would file across the flagstones. It was a Saturday when I saw a man sitting in the shade on the sidewalk eating dried meat and cassava broth out of a gourd: it was Saturday afternoon and we had already been swimming. At two o’clock in the afternoon, the bell announced to the wind that it was time for the movie matinee: and to the wind, Saturday was the rose of our rather dull week. If it rained, only I knew it was Saturday: a rather damp rose. In Rio de Janeiro, just when you think the weary week is about to expire, it opens out into a rose with a great metallic clatter: on the Avenida Atlântica a car screeches to a halt and, suddenly, before the startled wind can begin blowing again, I feel that it is Saturday afternoon. It was Saturday, but it’s not the same. I say nothing then, apparently resigned: but the truth is that I’ve picked up my things and gone straight to Sunday morning. Sunday morning is also the rose of the week. Although Saturday is much more so. I’ll never know why.

Translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson. Adapted from Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas, which will be published by New Directions in September. Originally published as Todas as crônicas in 2018. Courtesy of Paulo Gurgel Valente.

Clarice Lispector (1920–1977) was born to a Jewish family in western Ukraine. As a result of the anti-Semitic violence they endured, the family fled to Brazil in 1922. Lispector grew up in Recife and moved to Rio de Janeiro at the age of nine, following the death of her mother. She is the author of nine novels as well as of a number of short stories, children’s books, and newspaper columns.

August 22, 2022

Chateaubriand on Writing Memoir between Two Societies

Charles Etienne Pierre Motte, The Surroundings of Dieppe, 1833, licensed under CC0 1.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848) was born in Saint-Malo, on the northern coast of Brittany, the youngest son of an aristocratic family. After an isolated adolescence spent largely in his father’s castle, he moved to Paris not long before the revolution began. In 1791, he sailed for America but quickly returned to his home country, where he was wounded as a counterrevolutionary soldier, and then emigrated to England. The novellas Atala and René, published shortly after his return to France in 1800, made him a literary celebrity. Long recognized as one of the first French Romantics, Chateaubriand was also a historian, a diplomat, and a staunch defender of the freedom of the press. Today he is best remembered for his posthumously published Memoirs from Beyond the Grave.

Sojourn in Dieppe—Two Societies

Dieppe, 1836; revised in December 1846.

You know that I have moved from place to place many times while writing these memoirs, that I have often described these places, spoken of the feelings they inspired in me, and retraced my memories, mingling the stories of my restless thoughts and sojourns with the story of my life.

You see where I am living now. This morning, out walking on the cliffs behind the Château de Dieppe, I gazed at the archway that leads to those cliffs by means of a bridge thrown over a moat. Through that same archway, Madame de Longueville escaped from Queen Anne of Austria. Stealing away on a ship that set sail from Le Havre, she landed in Rotterdam and rendezvoused in Stenay with Marshal de Turenne. The great captain’s laurels had by then been sullied, and the exiled tease treated him none too well.

Madame de Longueville, who did honor to the Hôtel de Rambouillet, the throne of Versailles, and the city of Paris, fell in love with the author of the Maxims [Turenne] and tried her best to be faithful to him. The latter lives on thanks less to his “thoughts” than to the friendship of Madame de La Fayette and Madame de Sévigné, the poetry of La Fontaine, and the love of Madame de Longueville. So you see the value of having famous friends.

The princesse de Condé on her deathbed said to Madame de Brienne, “My dear friend, write to that poor wretch in Stenay and acquaint her with the state in which you see me, so that she may learn how to die.” Fine words—but the princess was forgetting that she had once been courted by Henry IV and that, when her husband took her to Brussels, she yearned to find her way back to Béarn, “to climb out a window at night and ride thirty or forty leagues on horseback.” She was at that time a “poor wretch” of seventeen.

At the foot of the cliff, I found myself on the high road to Paris. This road rises steeply as it leaves Dieppe. To the right, on the ascendant line of an embankment, stands a cemetery wall; along this wall is a wheel for winding rope. Two rope makers, walking backward side by side, swinging their weight from one leg to the other, were singing together in low voices. I pricked up my ears. They had come to these two lines in “Le vieux caporal,” that fine poetic lie which has led us where we are today:

Qui là-bas sanglote et regarde?

Eh! c’est la veuve du tambour.

The two men sang the refrain, Conscrits, au pas; ne pleurez pas … Marchez au pas, au pas, in such manly and melancholy voices that tears welled in my eyes. As they kept in step and wound their hemp, they seemed to be spinning out the old corporal’s dying moments. I cannot say what share of this glory, so forlornly disclosed by two sailors singing of a soldier’s death in plain view of the sea, belonged to Béranger.

The cliff had put me in mind of monarchical grandeur, the road of plebeian celebrity, and I now compared the men at these two ends of society. I asked myself to which of these epochs I would prefer to belong. When the present has vanished like the past, which of these two forms of fame will most attract the attention of posterity?

And yet if facts were everything, if in history the value of names did not counterweigh the value of events, what a difference between my days and the days that passed between the deaths of Henry IV and Mazarin! What are the troubles of 1648 compared to the revolution that has devoured the old world, of which it will die perhaps, leaving behind neither an old nor a new society? The scenes I have described in my memoirs—are they not incomparably more important than those recounted by the duc de La Rochefoucauld? Even here in Dieppe, what is the blithe and voluptuous idol of seduced, insurgent Paris set beside Madame la Duchesse de Berry? The cannon fire that announced the royal widow to the sea sounds no longer; those blandishments of powder and smoke have left nothing on shore except the moaning waves.

The two Bourbon daughters, Anne-Geneviève and Marie-Caroline, are nowhere to be found; the two sailors singing the song of the plebeian poet will sink into obscurity; Dieppe is void of me. It was another “I,” an “I” of early days long gone who lived in these places, and that “I” has already succumbed, for our days die before us. Here, you have seen me as a sublieutenant in the Navarre regiment exercising recruits on the shale. Here, you have seen me exiled by Bonaparte. Here, you will see me once more, when the days of July take me by surprise. Here I am again, and here I take up my pen one more time to continue my confessions.

So that we understand each other, it will be useful to take a look around at the current state of my memoirs.

What has happened to me is what happens to every contractor working on a large scale. To begin with, I built the outer wings, then—shifting and reshifting my scaffolding—raised the stone and mortar of the structures in between. It took many centuries to complete the Gothic cathedrals. If heaven permits me to go on living, this monument of mine will be finished in the course of my years; the architect, still one and the same, will have changed only in age. Still, it is taxing to keep one’s intellectual being intact, imprisoned in its weather-beaten shell. Saint Augustine, feeling his clay crumbling, said unto God, “Be Thou a tabernacle unto my soul.” And to men he said, “When you find me in these books of mine, pray for me.”

Thirty-six years divide the events that set my memoirs in motion from those that occupy me today. How can I resume, with any real intensity, the narration of a subject that once filled me with fire and passion, now that there are no longer any living people with whom I can speak of these things, now that it is a matter of reviving frozen effigies from the depths of Eternity and descending into a burial vault to play at life? Am I not already half-dead myself? Have my opinions not changed? Can I still see things from the same point of view? The prodigious public events that accompanied or followed those private events that so perturbed me—has their importance not dwindled in the eyes of the world, as it has in my own? Anyone who prolongs his career on earth feels a chill descending on his days; he no longer finds tomorrow as interesting as he found it yesterday. When I rack my brains, there are names, and even people, that escape me, no matter how much they once may have caused my heart to pound. Oh, the vanity of man forgetting and forgotten! It is not enough to say “Wake up!” to our dreams, our loves, for them to come to life again. The realm of the shades can only be opened with the golden bough, and a young hand is needed to pull it down.

From Memoirs from Beyond the Grave: 1800–1815 by François-René de Chateaubriand, translated by Alex Andriesse, which will be published by NYRB Classics in September.

François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848) was a writer, historian, and diplomat, and is considered one of France’s first Romantic authors.

Alex Andriesse is a writer and translator. In addition to Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, he has translated the work of Roberto Bazlen, Italo Calvino, and Marcel Schwob. He is the editor of The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick and an associate editor at New York Review Books.

August 19, 2022

Abandoned Books, Anonymous Sculpture, and Curves to the Apple

Bernd and Hilla Becher photographs at Galerie Rudolfinum Praha. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

In August, I become regretful about everything that I haven’t squeezed into my summer and probably won’t. Here is an incomplete list of books I have started and not finished: First Love by Gwendoline Riley, At Freddie’s by Penelope Fitzgerald, The Palace Papers by Tina Brown, Sex in the Archives by Barry Reay, and—many times—Swann’s Way (the first few pages). I abandoned all these books at different points and for the usual reasons; I was busy, bored, or left my copy at the beach. It seems like they are no longer going to be my summer reading—maybe in September.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

This week, I returned to one of my favorite explorations of the strange geometries of syntax: “Way down the deserted street, I thought I saw a bus which, with luck, might get me out of this sentence which might go on forever, knotting phrase onto phrase with fire hydrants and parking meters, and still not take me to my language waiting, surely, around some corner.” In Curves to the Apple, Rosmarie Waldrop’s sentences accelerate and swerve, reconfiguring the modern discourse on embodiment and subjectivity; there’s a spectacular volta lying in wait in each of these prose poems. “I learned about communication by twisting my legs around yours,” she writes, “as, in spinning a thought, we twist fiber on fiber.”

—Oriana Ullman, assistant editor

The Bernd and Hilla Becher photographs currently on view at the Met amazed me. They feature austere, serial portraits of industrial sites in Europe and America—lime kilns, cooling stations, gravel plants—which were already falling into abandonment in the last century. The photographers, who were a married team, called their practice “anonymous sculpture,” and the result is a surprising blend of conceptual and haunted that rigorously documents the past and transforms it into something almost tender: a monument of labor lost.

—David Wallace, advisory editor

August 18, 2022

Barefoot Astroturf Situation: June in New York

The Drift launch party on the rooftop at the Public Hotel. Photograph by Meredith Huelbig.

June 10

I wake up to three missed calls and matching voice mails from a blocked number that turns out to be FedEx Express Heavyweight informing me that since I was not around to receive my thousand-pound skid, it’s on its way to JFK. The delivery in question is Issue Seven of The Drift, the magazine I cofounded and co-run, and it was supposed to arrive next Monday or Tuesday in time for our launch party Thursday at the Public Hotel. Evidently it’s early … and sleeping in was a potentially multithousand-dollar mistake.

Kicking myself for how late I stayed out last night—there was a party at Russian Samovar for Joshua Cohen, whose novel The Netanyahus won this year’s Pulitzer in fiction—I dial FedEx and shoot an email to our printer. I got through most of The Netanyahus in a single sitting last summer, before I’d met its author. It’s mostly a satire based on an anecdote told to Cohen by the late literary critic Harold Bloom, but it’s also pointedly presentist, a self-conscious parable for liberalism in the Trump years. Early on it draws a dichotomy between history and theology that I’ve been mulling over since I encountered it.

While I’m on hold with FedEx I receive an email asking me to write a culture diary for this website, and I decide to start right away—no cherry-picking. Not that what I’m doing now is particularly “cultural”: I’m telling the automated system I’d like to “speak to a representative … speak to a representative,” getting transferred to incorrect extensions, hanging up, and dialing the line again. I haven’t even gotten out of bed.

Finally our printer manages to get in touch with their FedEx rep, and we’re told the issues have been successfully rerouted to my coeditor, Kiara, and will arrive at her apartment in fifteen minutes. I pull on some shorts and do my best approximation of a sprint. When the truck materializes, we watch the driver unload the skid and build a makeshift plywood ramp to wheel it up to the sidewalk. With the help of our new editorial assistant, Jordan, we cart all forty-something boxes up Kiara’s stairs. It is more exercise than I’ve had in months. I reward myself with an iced coffee and walk home in a daze.

My plans for the day derailed, I deal with the most urgent items in my inbox, and by then it’s already five and I have to shower and head over to Helena Anrather gallery, where the curator and Drift contributor Simon Wu has put together a group show.

By the time I make it there, late, the friends I’m meeting are done looking at the art and have located the tub of complimentary Pabst Blue Ribbons in the back. I walk through the main room on my own. The show, “Victoriassecret,” is woven together with a text Simon has written about his family’s immigration from Myanmar when he was a baby, the experience of moving back in with his parents during the pandemic, and what he calls “the emotional landscape of class aspirationalism.” I read a picture book Simon has written about his family history and watch one of the artists pose for a photo next to her sculpture of a Korean Jindo dog, which people keep whispering weighs two hundred pounds. It’s sitting on what looks like a cardboard box.

My friends are leaving for David Lewis Gallery, where Danny Bredar, a painter I know but haven’t seen in a while, is featured in another group show opening tonight. This one is called “A Mimetic Theory of Desire,” an apparent reference to the René Girard thesis that convinced Peter Thiel to invest in Facebook—Thiel understood, from Girard, that the impulse to imitate friends and acquaintances could be a marketable commodity—but I’m not sure I see the connection. One of the works shows a man looking at his phone below a bubble that reads, “OH DOING FINE Y’KNOW JUST BORED & HORNY LOL HOW BOUT YOU.” Danny’s is a striking oil painting of John Coltrane and Miles Davis.

Half our group has already departed, and we walk over to Spicy Village to meet them for noodles on a park bench. Danny’s sent us the cryptic invitation to the opening’s after-party, and since we’re a block away, we agree to drop by.

Now we’re on an Astroturfed rooftop where buff Nordic-looking men are handing out Aperol spritzes. There’s a DJ playing electronic music, and the ground is shaking as people jump up and down. Danny notes that the ladder to the water tower one roof over is too low.

For a while I eavesdrop on a guy complaining loudly about how he’s in love with an Orthodox Jewish girl who’s turned off her phone for Shabbat.

“I can’t even text her right now, bro,” he says. “It’s like, a paradox.”

Turning around, I see the silhouette of a man who’s climbed the too-low ladder up to the water tower and is now standing at the edge of the even higher roof. For a terrifying second I’m certain he’s going to jump, but then he does a little posturinatory shake and everything’s back to normal.

My friends are still chatting—something about the institutions of the art world—but I don’t want to talk anymore. I just want to zone out to the music, run my toes through the fake grass, and watch the spire on the Freedom Tower change color.

June 11

There’s a gash on the bottom of my foot! Initially I blame the barefoot Astroturf situation, but the culprit turns out to be a little nail poking out of one of the shoes I was wearing last night.

I spend most of the day on the emails I was supposed to send yesterday, scheduling them for Monday so people don’t think I work full-time seven days a week, and then it’s on to fiction submissions. Over the past few months The Drift has developed a massive slush pile, which our fiction editor, Emma, has been fighting through valiantly. It’s important to us to read and respond to every submission and pitch we receive—we want The Drift to be a place where new writers can publish for the first time—but it does mean we always have a backlog.

In theory I enjoy short stories, but today I’m having trouble focusing. It takes a while to get my bearings—decode what the writer’s going for, assess whether or not she’s succeeding—and by the time I’ve done that, the story’s over and it’s on to the next one. Reading slush can get disheartening, but then it’s always a thrill when we find something we love in the pile—something sharp and surprising and funny, at once intentional and light on its feet. Still plenty of time before we have to make our Issue Eight selections, I reassure myself.

I take a break to read Sam Adler-Bell’s essay on wokeness, which I’ve been saving for a few days in an open tab. I send it along to my family group text to resolve a recent debate about what “woke” means and whether or not it’s an insult. I like Sam’s definition: “Wokeness refers to the invocation of unintuitive and morally burdensome political norms and ideas in a manner which suggests they are self-evident.”

I read some more stories before deciding to clean my apartment, which is cluttered because it’s doubling as a Drift storage and mailing facility. My mom always used to tease me about my cleaning method—do one small corner with an unnecessary level of care and attention, then get distracted and forget to clean the rest of the room. She died about a year and a half ago, and I’m missing her especially today. I put on some James Taylor, her favorite, and start with the piles of books that have accumulated on my desk and coffee table. True to form, after about ten minutes and a single shelf tidied up, I remember an email I’ve forgotten to write.

June 12

Kiara has put together a script for the reading we’ll have at our issue launch party, and she sends me a Google Doc to mark up. We both often find literary readings intolerable, so we try to keep ours short—under twenty minutes total, divided among a group of issue contributors, each of whom is limited to a paragraph or two only.

I look through the most recent issue of the London Review of Books and read a piece on Tina Brown’s The Palace Papers, which I listened to on audiobook last month. Like many people in my demographic, I got hooked on the royal family by watching The Crown; unlike many people in my demographic, I watched all four seasons in a single week high out of my mind on painkillers after jaw surgery. When I’ve since discussed The Crown with friends, their reactions have led me to believe I absorbed more of its royalist ideology than otherwise accords with my ideas about the world. I turned to The Palace Papers hoping to be disenchanted, but the opposite happened. Things I’m now convinced of: Princess Kate is a Trollope heroine, Meghan represents everything wrong with 2010s self-promotion culture, Brown is a fabulous reader.

I’m still avoiding all the emails I need to write and to-do list items I need to cross off, so I scroll through the Iris Murdoch page on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. I’ve been asked to write a review that has to do with Murdoch, and while I probably don’t have time, I’m tempted. I look through my bookshelf for The Sacred and Profane Love Machine, which I was given as a present in high school and have still never read. (An unfortunate thing about me is that I hate receiving books as gifts. Once I’m given a book, it feels like homework and I’d rather read almost anything else. I was given Tess of the D’Urbervilles four times, by four different people, before I finally cracked it.)

Murdoch is a writer I should like more than I do. An Oxford academic turned novelist, her fiction in some sense extends from her critique of the limitations of analytic philosophy. She believed that philosophers too often neglected psychological complexity, and that without a more nuanced understanding of the psyche, it was simplistic to talk about a freely choosing will. She also saw the internal effort to be more generous in our judgments of others as crucial moral work. In part because I like these ideas so much, I always end up reading her novels programmatically. I find myself mapping her philosophy onto whatever the characters are thinking and doing, which tends to flatten the stories into the kinds of examples you’re given in a course like “Introduction to Ethics.”

Later on, I’m wasting time online and see that Bernadette Peters has sung “Children Will Listen” from Into the Woods as part of a Sondheim tribute at the Tonys. I click on the clip but it doesn’t scratch the itch, so I watch some YouTube videos of a younger Bernadette singing Sondheim. None of the recordings are very good. What I really want, I realize, is to listen to the original cast album. I grab my headphones and take a walk.

Into the Woods is probably the first work of art I loved as a child that I still think is perfect—encyclopedic, an attempt to interrogate foundational myths while putting a full spectrum of experiences and emotions on display. Sondheim’s is a bleak, if magical, view of the human condition: we’re doomed to not know what we want, to want what we can’t have, to be dissatisfied when we get it, to love the wrong people, then abandon and betray and outgrow them, to make mistakes and cast blame elsewhere, to try and warn our children, to ignore our parents’ advice. Every time I revisit it, a different lyric seems to shout out what’s been preoccupying me. This time it’s: “But how can you know what you want / Till you get what you want and you see if you like it?”

On the street I run into the artist David Levine, and he asks if I want to come to his studio to see a short holographic film he’s just finished exhibiting in Paris—I wasn’t free the night of his New York screening a few months ago. He says, “I won’t keep you, you’re probably heading off to dinner,” and I neglect to tell him that what I’m doing is listening to a musical about witches and princes on my phone.

June 13

Today I have to tutor high schoolers over Zoom. I also help prepare the Drift issue for online publication tomorrow and send a bunch of emails related to the fundraiser we’re throwing next week.

At five, Kiara and I have drinks with Zain Khalid to discuss the possibility of his joining us as fiction editor. (Emma is leaving to focus on her dissertation.) When I met Zain last summer, he gave me a hard time about The Drift’s fiction selections, and every time we’ve bumped into each other since then he’s commented on our newest stories. Zain appears to read everything published everywhere and has seemingly perfect recall and intelligent things to say about all of it. He hands me a galley of his soon-to-be-released novel, Brother Alive, and I walk out of the bar excited, a little buzzed, and a few minutes late for our seven o’clock Zoom.

Monday-night remote staff meetings are a Drift tradition that started in deep-COVID and has thankfully continued. As an issue deadline approaches, the meetings tend to be logistical—who’s taking an editing pass on what, when various pieces need to be finalized, which ones might be pushed to a future issue. This time, since our most recent issue has just arrived from the printers, we’re thinking about what the next issue should include. Sometimes our staff comes up with ideas, and we approach writers who might be willing to execute what we have in mind. But for the most part, Drift pieces result from cold pitches sent to editors@thedriftmag.com. Each meeting, we go through a Google Doc of the best pitches we’ve received the previous week and discuss the ones we might want to accept. Tonight we also talk over the plan for the party on Thursday—members of our editorial team will take turns manning the door and selling issues.

The meeting ends at eight sharp, and I’m out the door for oysters with my friend Gideon. After dinner it’s cooled down and lovely out, so I convince him to join me for another long walk.

June 14

The morning is a mad dash to release the issue—finalizing our newsletter, noticing that an image is too small, getting a broken link to load correctly on social media, etc.—and I’ve conveniently run out of coffee in my apartment. By the time we publish at noon, I’m in outrageous need of a caffeine fix. I look through the early reactions to the issue on my phone at the nearest coffee shop.

Almost immediately, it’s clear that the issue is being received more warmly than I’d expected. There are a few pieces I’ve been nervous about—pieces that challenge established progressive wisdom, and that I worried might prompt objections, but, at least so far, they haven’t.

In the late afternoon I go over to David Levine’s studio to see his film. I’m not sure what to expect, and as soon as I get there I start to feel how much pressure is involved in letting an artist watch you watch his work. This piece, called Dissolution, is a hologram delivering a monologue from the perspective of a woman trapped in, or maybe as, a work of art. David tells me I can walk around and view it from any angle, so I initially try to indicate my engagement by circling the machine, going up and down, side to side. It’s too hard to focus on the text at the same time as varying my position, though, and eventually I settle on the spot closest to the speaker. Most directly, Dissolution is a commentary on the powerlessness of art in contemporary society—its commodification for and by the rich, its political irrelevance. But the piece is also a kaleidoscope of topics from the news, a mix-and-match of contemporary idioms filtered through a trippy early video-game aesthetic. There are references to Epstein and cryptocurrency, as well as to the Orpheus myth and the Library of Alexandria. When it’s over, I wish I could watch it again. I’m not lying when I tell David I loved it.

On the way home I drop into the new Crown Heights Union Market. Distracted trying to parse David’s argument about commodification and attention, I grab a small bag of cherries without looking at the price and am grateful when the cashier asks if I’m sure I want them. They are nineteen dollars.

Back in my apartment, I start Brother Alive. From the first page, the language is purposeful and evocative, and it soon becomes clear how ambitious the novel is in scope. But at the beginning I’m still getting acclimated to the world of three adopted boys, each with a different skin tone, being raised by a mysterious imam on Staten Island. The narrator, Youssef, might be mad, or haunted—it’s too early to tell.

Around two in the morning, Kiara and I realize we’re both up late plodding through the Drift email account.

June 15

Kiara, Jordan, and I work together at my place for a while, and then I head out to David Zwirner, where The Drift is hosting a fundraiser for the second anniversary of our launch next week. I’m supposed to check out the gallery and go over details with Felice, who has been helping us coordinate the event. It’s the first time we’ve ever organized anything of this sort. Two years ago, Lucas Zwirner, who is head of content at the gallery, sent a cold pitch to our general inbox, and we published his essay on self-consciousness and absorption in modern art in our second issue. When we met him in person this spring, Lucas asked if we might like to use the gallery for a fundraiser.

The Upper East Side location of David Zwirner is housed in a Sixty-Ninth Street townhouse with an elegant spiral staircase that twists up five stories. As I’ll later learn, the building used to be the Iranian consulate before the 1980 diplomatic freeze. Even later, I’ll dig up a picture of Princess Ashraf Pahlavi leaning against the fireplace on the second floor and wearing what the caption calls “a red Dior.” For now I’m the only person in the gallery, and it’s strange to have a show to myself. “By Land, Air, Home, and Sea: The World of Frank Walter,” curated by Hilton Als, is an understated exhibition of paintings and sketches. Walter, who traveled to Europe as the first manager of color within the Antiguan Sugar Syndicate, returned to the Caribbean in the sixties as an artist, writer, and critic of racism. As Als writes, viewing the series of small, fragmentary paintings is “like looking through a scrim at someone else’s dreams.”

After Felice arrives and we discuss where the toasts should be given and whether or not a microphone will be needed, I walk around the neighborhood in search of a venue for our after-party. I poke my head into a few of the Upper East Side’s more dive-adjacent establishments before making my selection. (As I’ll be informed too late, the one I’ve chosen is the Fox News happy hour spot.)

I head to dinner with my cousin and her new fiancé. They’re in town from Australia and meeting me and my dad before they see A Strange Loop on Broadway. I walk past the Park Avenue Armory, where I saw The Lehman Trilogy three years ago (stunning, original, a capsule history of capitalism). I walk past a painting class in which everyone’s copying a cityscape at sunset (not so stunning or original, nothing to say about capitalism). I walk past the Central Park Zoo, and it makes me think back to a scene in Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, which I finished this winter. Building the zoo as a favor to Al Smith is the nicest thing Robert Moses does in all 1,344 pages. At its opening ceremony, Smith was appointed “Honorary Night Superintendent,” and for the rest of his life, he was allowed to enter the animal houses after hours, any time he liked. When he had dinner guests at his apartment across the street at 820 Fifth Avenue, he’d take them to see the zoo’s largest tiger, whom he knew how to make growl at the name “La Guardia.”

June 16

I try to sleep in so I can make it through our party tonight, but the sidewalk outside my window is being jackhammered. The day disappears into a morass of party prep, and somehow by the time I leave the house I’m running late for our mic check.

On the subway ride over to The Public I receive a series of confused-to-alarmed texts from Kiara, who says the hotel is not expecting us. We’ve arranged the event with a PR person who offered us the rooftop for free and had several calls with Kiara to coordinate details. Unfortunately none of that information was passed along to the hotel staff: the roof has been double-and-triple-booked, and there’s some sort of NFT happy hour happening in the space where we’d planned to set up our reading. People are arriving for drinks and dinner reservations, and the staff is saying we’re not in their system. Someone named Paloma promises us no one will be turned away, but of course this is a lie, and soon enough our editors on door duty downstairs are reporting that the bouncer is sending home hundreds of guests, telling them they aren’t even allowed to wait in line. (People are also being denied entry for offenses like wearing Tevas and graphic tees.) I take the elevator down and explain to the bouncer what Paloma had told me only two hours earlier. “I never said that,” she says, after being summoned via walkie-talkie. “Did you get that in writing?” asks the bouncer.

Back upstairs, the guests who’ve managed to get in seem to have no idea anything’s wrong. The readings went better than we could have hoped—jam-packed room, audience listening attentively and laughing in all the right places—and for the next few days people will keep texting me “amazing party!!!” as if it wasn’t an outright catastrophe. By this point in the evening, our group has displaced the NFT crowd from the prime rooftop real estate, and I listen to newcomers describe Caveh Zahedi’s Ulysses performance, which they’ve just come from. It’s Bloomsday on the centenary of Ulysses’s publication, and I’m sad I’m not doing anything more appropriate. I wonder what Joyce would make of Ian Schrager.

Around midnight the staff starts ushering us toward the elevators, which is also contrary to the arrangement we’ve made, but I’m past caring. A few people suggest a bar for an after-party, and Kiara and I decide to tag along. Our friend Ben offers to pick us up empanadas, and someone I haven’t met orders a pizza. It’s the first food I’ve had in many hours.

Kiara and I Uber back to Brooklyn together with the leftover box of issues we haven’t sold. She’s locked out of her place, though, so she comes over to mine. It’s late but we’re both still keyed up, and we lie around laughing about the NFT happy hour and “Did you get that in writing” and vowing never to trust a PR person again … and then it’s four or five and we fall, at last, asleep.

Rebecca Panovka is a writer and coeditor of The Drift.

August 16, 2022

Past, Present, Perfect: An Overdue Pilgrimage to Stonington, Connecticut

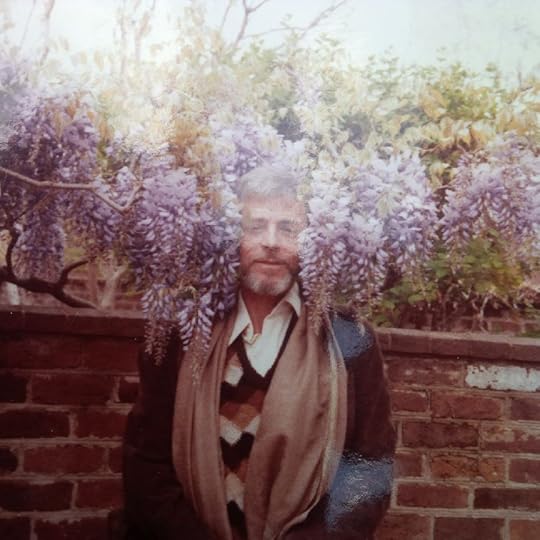

James Merrill with wisteria in Charlottesville, 1976. Photograph by Rachel Jacoff.

In French the word merle means blackbird, a dark bird of the thrush family. A blackbird’s song marks its territory. The male has black feathers and a yellow beak. It is in the same genus as the meadowlark. Forty years after first meeting James Merrill at my teacher David Kalstone’s Chelsea apartment, I am sitting at his desk in Stonington, Connecticut, with his large Petit Larousse open before me. Searching for the meanings of our names in French, I am distracted by a blackbird perched on the windowsill, drinking a little dew and then swaying on a nearby branch. It speaks in polished, rudimentary tones with a slow tempo.

Merrill’s big desk is in a small room—in an apartment of small rooms—behind a hinged bookcase that creates a very private space. Still, I can hear a train whistle, a foghorn, halyard lines clinking against the masts of sloops anchored in the harbor, church chimes, and bits of conversation from villagers below on Water Street. These must be the sounds Merrill heard, too, while working. He was an early riser and liked to give the first hours of the day to his poems, which reflect, mirrorlike, so many of my own feelings. Mirrors are also a motif in his poems—mirrors that remember us across the years, reflecting our beauty and dissolution alike. It has taken me some days to sit at his desk.

Mirror in the Merrill House. Photograph by Henri Cole.

In French, my name means collar, and I think immediately of the metaphysical poet George Herbert’s poem “The Collar,” published in 1633, a poem in which the fervid speaker seeks more freedom in his life. It is a poem of strong feeling, almost like a rant. Like his friend Elizabeth Bishop, Merrill loved Herbert’s poems and could quote them by heart. During my twenties and thirties, perhaps there was no living poet I admired more than Merrill, and I am drawn still to this American poet, who was said to be writing even while needing oxygen on the night before his death more than twenty-five years ago.

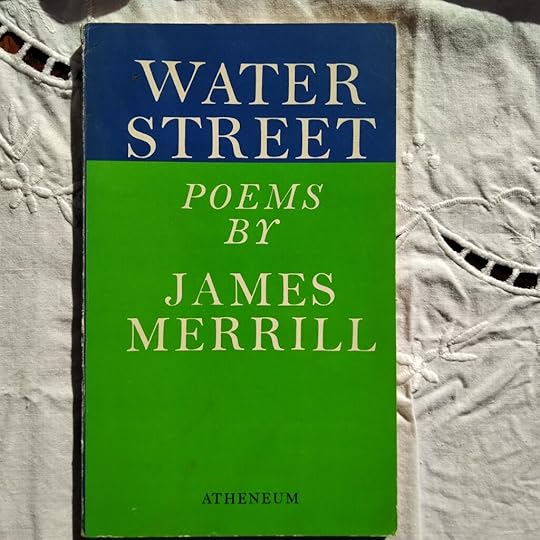

Long ago, in the eighties and nineties, Merrill and I shared an editor, Harry Ford, who seemed unconcerned that publishing poetry can be a money-losing proposition and gave our books his distinctive typographical cover designs. When he took me on, I was his youngest poet, as Merrill had been years before. Though Harry had found Merrill’s First Poems “ornate,” he loved his second book, The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace, and eagerly published it. This put Merrill on the map of American poetry, if there is such a map hanging in a long hall somewhere in America. In 1995, when Merrill died unexpectedly in Arizona while vacationing, his body was flown to New York City, where Kathleen Ford, Harry’s wife, was asked to identify it. She told me, “Its solidness befitted the great poet he was.”

Photograph by Henri Cole.

Sometimes I think Merrill is misunderstood as a technically masterful, unemotional poet. This is what was once said about his friend Elizabeth Bishop, too. Because he is so often described as elegant, I wonder if this is code for homosexual, for this is how my work is sometimes described also. Long ago, Merrill told me that he was grateful for the neglect of his early work, because when the praise came later in his life, it came abundantly, for this visionary author of The Changing Light at Sandover. This was his complex, epic poem, one which seemed authorized by Dante, with its guide figure, Ephraim, standing in for Virgil, with its conversations with “the other side,” with its occasional terza rima, with its repeated theme of stars, and with an epigraph from Paradiso XV: “You believe the truth, for the lesser and the great / of this life gaze into the mirror / in which, before you think, you display your thought.”

In Stonington, I am pretending not to be a guest as I climb the steep and narrow studio stairs to water Merrill’s ancient jade plant. It appears to thrive even in neglect, like a poet in middle age. Is it true that a jade plant brings financial good luck? Is it true that an extract from its succulent leaves can be used to treat wounds? Is it true that the jade is a tree of friendship, something Merrill had a marvelous gift for?

Dining room table. Photograph by Henri Cole.

Each day I walk around the village. Sometimes Gigi, a friend of my youth, accompanies me. Her family has lived in Stonington for six generations. When she was a teenager, she met Merrill because her grandparents lived across from him on Water Street. He read Gigi’s first poems before she went off to study writing at Iowa, and she gave him vegetables grown in her backyard garden. As a young woman, she married a local artist and teacher, who later died at sea while lobstering. She once lived in a little house without central heat over on Gold Street. The village was different then, with its noble houses falling down and laundry hanging out on lines to dry. Now the homes have been refurbished. The artists and the Portuguese fishermen have been replaced by wealthy summer people, but there is still a fishing and lobstering fleet.

On Saturday mornings, I accompany Penny, a new village friend, to the farmers market on the other side of the railroad tracks, where we buy fresh bread, local vegetables, and a basket of white peaches to share. Because Penny is a patient listener, the pretty cheesemonger tells her the story of her life, while angry bees fly around and explore the little mountains of pungent cheeses. Every evening a small group of villagers swims from DuBois Beach to the breakwater. I am afraid of the jellyfish and stand alone on the shore to watch the swimmers until their arms and legs disappear into the chop of dark water.

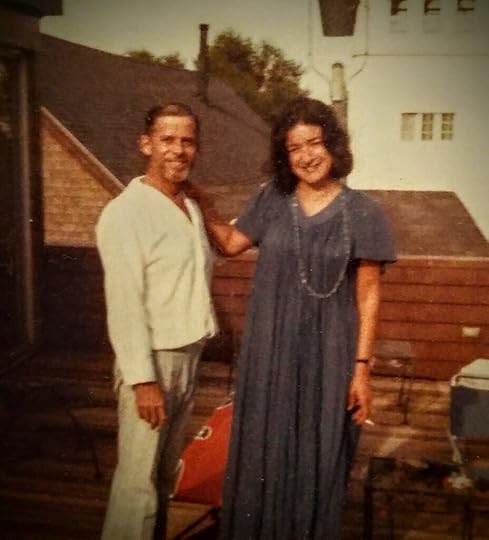

James Merrill and Rachel Jacoff. Photograph courtesy of Rachel Jacoff.

Ever since Hurricane Henri, the tropical cyclone that made landfall in late August, the blue sky has sparkled without a cloud. All day I listen to seagulls, who have so much to say as they circle around the harbor. I am relieved not to be visited by the restless, lonely spirits that frequented Merrill’s Ouija board. Later today, I am meeting Jonathan for a BLT. We’ll sit on a park bench near the library and talk about his new book on Bishop. He’ll show me his signed first edition of Geography III, and I will feel covetous. Then Sibby, a villager, will introduce me to her goats, her hens, and her aggressive, polyamorous rooster, whose comb will turn pale a few days later, a fatal sign. Then I’ll have a drink with the village warden, Jeff, the mayor of the borough, and his wife, Lynn, who will dig up a gorgeous autumn fern from their yard for me to plant at Merrill’s grave.

“What would Merrill think of my being here?” I ask my friend Rachel, a retired Dante specialist who knew him. “He would be so delighted,” she insists. In his too short, peripatetic life—like Bishop, he died at sixty-eight—he frequently loaned his homes to his friends, as he did to Rachel during a sabbatical in the eighties. In his will, Merrill left the three-story building at 107 Water Street, including his penthouse apartment, to the Stonington Village Improvement Association, which conceived of the one-month writers’ residency program that brought me here. I imagine Merrill folding his clothes in the basement laundry room like me, and walking to the post office to mail his postcards, and putting an avocado pit in a glass of water to start its rooting. He kept no garden, but he was “earth’s no less.”

The Perényi’s front door. Photograph by Henri Cole.

At a handsome house on Main Street, I visit the ashes of my poetry teacher David Kalstone, who was a brother-like friend of Merrill’s from the sixties. David died of AIDS in 1986, when he was only fifty-three. That was the year I came out to my parents. I don’t know how I survived that dark decade. David’s illness was mercifully brief—pneumonia, the dimming of his mind, and confinement to bed. Like many, he was cared for by friends and had no formal funeral. Some of his ashes were emptied “into the black, starlit water of the Grand Canal” in Venice, as Merrill told those gathered later at a memorial. Some more of his ashes were taken in a dinghy out into the tidal river just east of Stonington and emptied underwater. In an unpublished diary, which was preserved along with his papers, Merrill describes “a ‘man-sized’ cloud of white, dispersing, attended by a purple-&-white jellyfish acolyte.” A last teaspoon was sprinkled with lilies of the valley under an old apple tree in the writer Eleanor Perényi’s garden. There was a reading of the Sidneys’ translation of the twenty-third Psalm: “Thus thus shall all my days be fede, / This mercy is so sure / It shall endure.” Though the apple tree is gone, a horse chestnut reaches happily toward the sunlight today. Perényi’s son, Peter, and his wife, Sharon, who live there now, serve me a slice of coffee cake with a cappuccino on their back porch. While we talk about the past, Libby, their handsome rescue dog—part Great Pyrenees, part Anatolian shepherd—sits at my feet. Unusual mushrooms like “shameless phalluses,” known as stinkhorns, grow around the garden. If eaten when young, they are said to be crisp and crunchy with a radishy taste. Their caps are coated in a dark, olive-green slime and crowned with a small white ring.

Shameless phalluses. Photograph by Henri Cole.

Soon after David’s death, Merrill composed a quatrain in his diary: “Beloved friend, the sky + sea / of Stonington’s your limit? No: / To Heaven fly, to Venice flow. / Home-free, home-free.” And there are these sorrowful sentences: “Every ½ hour I just break into sobs—sounds I’ve never before heard come out of me. No quarrel ever. No tension. Pure fun & communion. A 2nd self I could reach by telephone, or walking into the next room … there are no more where they came from, the friends of one’s heart.” The poet Adrienne Rich wrote to J. D. McClatchy, who’d helped care for David: “When I first knew David he was a graduate student at Harvard and I was a divided woman poet/faculty wife with 3 young children … He and Randall Jarrell were the first critics to encourage what I was doing in the 1960’s when many who had approved my earlier work were getting uneasy.” Unlike other critics of the day, David didn’t think the generation preceding Rich and Merrill’s was “the last word, the ultimate canon.”

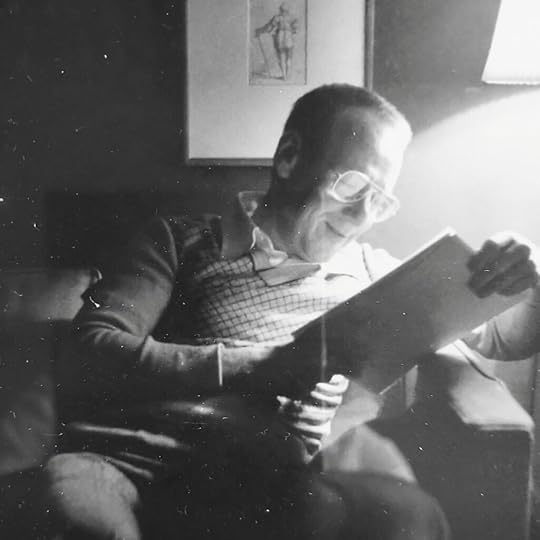

David Kalstone in his apartment reading. Photograph courtesy of Rachel Jacoff.

Some years after David died, I visited Merrill in Key West, where he then spent his winters. We sat at the back of his house in a big sunny room with cedar walls. John Malcolm Brinnin—the biographer, critic, and poet—was there. Both men wore Birkenstock sandals, and Merrill sat in a big bamboo chair that was a birthday gift from the poet Mona Van Duyn. They were talking about their elderly mothers—Merrill’s was 92 and Brinnin’s 102. When Brinnin recounted how on his mother’s hundredth birthday she’d asked, “What’s birthday?” and there was silence. After all, they were elderly, too.

Merrill invited me to lunch at a small Spanish restaurant with only a handful of tables that was tucked away on a back street. It was unchanged from “Elizabeth’s time,” he told me. In 1938, Elizabeth Bishop had bought a house in Key West at 624 White Street, with her friend Louise Crane. In her journal, she writes about the lime tree in her yard, in whose “cool shadow” love was nurtured and betrayed. We shared an order of rice and beans with plantains, and for dessert, we divided a serving of flan, which he slid off the plate with his fingers and then licked them. On a tiny shelf over the door to the kitchen, there was a display of large dusty santos—ornamental figures from the Christmas crèche—and I remembered Merrill’s poem “Santo”:

Francisco on his shelf,

Wreathed in dusty wax

Roses, for weeks and weeks

Hadn’t been himself—

Making no day come true

By answering a prayer

Just dully standing there …

Merrill said this poem expressed “in miniature the whole self-revising nature of the Sandover books, where no ‘truth’ is allowed to rot under a single, final aspect.”

After Merrill paid for our lunch, he calculated to the penny what the tip should be and left this exact amount. Then we walked to the library, where he hoped to find an English-French dictionary at the used-book sale to help him translate a sonnet by the French poet, novelist, dramatist, freethinker, and occultist Victor Hugo. Today I can find no translation of Hugo in his Collected Poems and I wonder which sonnet it was. It was Merrill’s sonnet sequence “The Broken Home” that first made me a fan of his work. The poem appeared in his breakthrough volume, Nights and Days, published when he was only forty. It is composed of seven sonnets about his relationship with his wealthy, energetic father, Charles E. Merrill, a founding partner of the investment firm of Merrill Lynch. The poem is a meditative lyric, but narrative, too, with psychological intensity. As there are in some of Bishop’s poems, there are discreet references to the poet’s homosexuality.

The poem’s sonnets are not strict—each is linked to another by a theme or image. Because each sonnet presents a self-contained scene, the poem expands and contracts like the reader breathing, feeling, and thinking. It begins with the speaker alone on the street observing a little family framed by a window. Then, later, “in a room on the floor below,” Merrill lights a candle and speaks to the flame: “Tell me, tongue of fire, / that you and I are as real / At least as the people upstairs.” The word real reappears, because the solitary speaker longs to be as real as the little family he sees in the window.

James Merrill’s embroidered child’s chair. Photograph by Henri Cole.

Some years before my visit to Key West, Merrill had flown to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and been diagnosed with ARC or AIDS-related complex, though this was something he remained silent about for the rest of his life, telling only a few friends. Merrill was not a poet of grievances, but in his diary he opens up:

“The state of my health has made me stop drinking (or all but) + smoking (entirely) and kept me harder at work, I think, than I’d have been otherwise.”

“Art is a not-at-all reluctant alternative to life.”

“My days are numbered. But so are everyone’s, if only in retrospect … Thousands of people are in my exact position, only they haven’t thought (or wished) to take a blood test. I know that I shall (unless a miracle cure emerges) be dead in 3 years, more or less.”

Though Merrill described his illness as “bearable,” he wrote that it was nevertheless “appalling to live in a present whose future … has been so frostbitten.” He reminded himself to reread the lines 8–14 on page 304 of his Changing Light at Sandover:

Ah, it’s grim. Yet what to ask

Of death but that it come wearing a mask

We’ve seen before; to die of complications

Invited by the way we live. Bad habits,

Overloaded fuses, the foreknown

Stroke or tumor—these we call our own

And face with poise.

This was written before the modern drugs for treating HIV. I say modern, though forty years later there is still no miracle vaccine or cure.

James Merrill’s dictionary. Photograph by Henri Cole.

During my stay in Key West, I borrowed Merrill’s bicycle and rode across town while he exercised on his cross-country skiing machine. I rode through the vast cemetery and found Bishop’s house, which was hidden by a jungle of trees and potted plants. Its unpretentiousness pleased me—its wide-open shutters and front door, motor scooter parked in the yard, and comforter hanging from a second-floor window. Merrill wrote in his diary: “EB more present in later poems. The figures walking up and down the icy beach … we stand back from them … we see more of the human condition mimed out for us than ever previously.” Certainly, this is true of one of Merrill’s last poems, “Christmas Tree,” in which he sees himself and his destiny in a tree brought down from “the cold sighing mountain” to be “wound in jewels” and kept warm for a short time, with a “primitive IV” behind it “to keep the show going,” before it is left out on the “cold street”—just “needles and bone”—to be “plowed back into the Earth for lives to come.” Elsewhere in his diary, Merrill writes, “Life is so like Chekhov—the characters + motives all sweetness, the plot deadly nightshade.”