The Paris Review's Blog, page 184

February 12, 2020

The Torment of Cats

In her monthly column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Right, Hrabal with one of his cats (courtesy of New Directions)

“If you want to write, keep cats,” Aldous Huxley famously said. As I read Bohumil Hrabal’s haunting but strange slip of a memoir, All My Cats, I wondered if the Czech writer would have agreed with him. Hrabal’s book was originally published in 1986, as Autičko—which translates as “the Little Car,” the nickname Hrabal gave first to his Renault 5, a small white car with ginger-colored seat covers. He later gave the same name to one of his cats, a kitten with “white socks and a white bib, and the rest of it had a tabby pattern, but in ginger.” The volume has only recently been translated into English, excellently so by Paul Wilson. Do not be fooled by the cuteness of the book’s original title, though. In it, we encounter a cat lover trapped in a hell of his own making, driven to the brink of madness.

Hrabal, who was born in 1914 in Morovia, began writing poetry in the forties, and by the following decade switched to prose. Little of what he was writing made it into print—instead he read his work aloud at meetings of an underground literary group, attended by the novelist Josef Skvorecky and run by the poet Jiri Kolar. Some of Hrabal’s stories appeared in samizdat editions, but his first officially published work, Lark on a String, was withdrawn in 1959, a week before it was due to be released; his formally inventive style regarded as the antithesis of the realist works glorified by the Communist regime. (It eventually appeared, four years later, as Pearl on the Bottom.) In the early sixties, Hrabal’s émigré friends helped distribute his work abroad, where it found a success that allowed him to write full time. He’d worked, before then, as a railway laborer, an insurance agent, a traveling salesman, a laborer at a steelworks, a compactor of wastepaper at a trash plant, and a theater stagehand. Those odd jobs inspired certain of his novels, such as Closely Observed Trains, a story about a Czech railway worker who defies his Nazi oppressors, and Too Loud a Solitude, in which the narrator builds his own library from books he’s salvaged, as Hrabal did during his time at the trash plant. The publication, in 1963, of Pearl on the Bottom launched Hrabal’s career properly in Czechoslovakia. This was followed, only a year later, by Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age—a book that, like Lucy Ellmann’s recently lauded Ducks, Newburyport, unfurls in a single, rambling sentence—and the year after that by Closely Observed Trains, which further cemented Hrabal’s success when it was adapted into a movie. Directed by Jiří Menzel, Ostře sledované vlaky won the 1968 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and remains today one of the popular works of the Czech New Wave.

Although by the mid-’60s Hrabal was famous, this didn’t mean he had carte blanche to publish whatever he wanted. After the Prague Spring in 1968, his work was once again banned until the late seventies. It’s thanks to people like Skvorecky—who had left Czechoslovakia for Toronto, where he published the works of his friends—that Hrabal’s writing still reached readers. Not that the years of censorship did much to dim Hrabal’s fame. In 2008, his fellow countryman Milan Kundera called Hrabal “our very best writer today,” and with each new translation of one of his works, Hrabal continues to find new admirers further afield.

That it has taken thirty-odd years for All My Cats to join these translations perhaps isn’t surprising. Although it showcases many of the same stylistic elements that distinguish Hrabal’s fiction—such as the near stream-of-consciousness, meandering soliloquizing of his narrator—this memoir is a trickier beast to wrangle with. Although All My Cats starts out as an enchanting account of a cat lover’s feline-filled existence, the book soon transmogrifies into something much darker, becoming a meditation on love, loss, genocide, and guilt.

*

Writing in the New York Times three years ago, Parul Sehgal memorably described Hrabal as “one of the great prose stylists of the twentieth century; the scourge of state censors; the gregarious bar hound and lover of gossip, beer, cats and women (in roughly that order).” In 1983, when Hrabal sat down to write All My Cats, he was sixty-nine years old and recovering from a serious car accident. The cats in his life, he admits at the very beginning of the book, had by this point replaced the women of his youth: “Somehow I had reached an age where being in love with a beautiful woman was beyond my reach because now I was bald and my face was full of wrinkles, yet the cats loved me the ways girls used to love me when I was young.”

The cats he’s talking about live at the country cottage Hrabal shares with his wife in Kersko—about an hour’s drive east of Prague. They’d bought it back in 1965, when Hrabal was reaping the first financial rewards of his writing. It was a weekend getaway from the city; somewhere Hrabal could supposedly write undisturbed. At first, all was wonderful. The cats—of which there were initially five—eagerly awaited Hrabal and his wife’s visits. “I’d gather them, one by one, into my arms and press them to my forehead,” he writes, “and somehow or other, those cats cured me of my hangovers and depressions.” As if to corroborate Jean Cocteau’s assertion that cats are “the visible soul” of a person’s home, Hrabal describes the early morning “meshugge Stunde”—the “crazy hour”—during which the cats, warmed against the cold night air by the covers of Hrabal’s bed, would take off, running wild around the house in joyful excitement, swinging on the curtains, pulling clothes off chairs, fighting over slippers and “winding themselves into little balls and knocking everything off the table.” Before long, the cats become a responsibility weighted round Hrabal’s neck, turning his former bucolic idyll into “a hell,” a “house of horrors and humiliations.”

When he’s in Prague, he worries that the cats are cold, hungry, and lonely without him. Thus, unable to concentrate on his writing, he’s drawn back to Kersko—in the winter, he travels by bus, which is safer, he thinks, than driving himself, for who would feed his cats if he was hurt in an accident? But once there, his writing again eludes him: “The typewriter would clatter away but there was never enough time to attend to stylistic niceties, I had to write quickly so I could spend time with the cats because, though they lay there with their eyes closed, they’d be watching me through tiny slits, lulled by the clacking of the machine.”

Soon enough, distraction turns to anger. Hrabal forcefully boots a particularly annoying feline out into the garden, and then is immediately overwhelmed with regret: “I couldn’t write because I had struck a cat that I loved, I had kicked an innocent creature who meant everything to me.” This oscillation—between exasperation, rage and violence, and contrition, love and self-reproach—is what drives the narrative. Hrabal is trapped in a limbo. His distinctive “palavering”—Skvorecky’s translation of what Hrabal himself termed his “pábení” style—or, in other words, his free-flowing monologue (as James Woods helpfully elucidates, an “anecdote without end”) lends itself particularly well to such undulations. Repetitions become a considered stylistic element, most notably Hrabal’s wife’s exasperated protest, “What are we going to do with all those cats?” It’s the very first line of the book; foreshadowing the actions Hrabal will eventually find himself forced to take. She herself is a vague figure, this is the only thing she says, but it’s echoed as a refrain throughout the volume.

What, indeed, is Hrabal going to do about all those cats? When two of Hrabal’s cats produce a litter of five kittens each at the same time, enough is enough. Acting “in a kind of fever,” he sends his wife to the neighbors before picking three kittens—still blind, and as tiny as “transistor radio batteries”—from each litter and bundling them into an old mail bag. As if “in a trance,” he carries the sack into the woods and “battered” it “against a tree, again and again and again.” It’s a scene of shocking violence, leaving him feeling “crushed, suffocated by what I had felt compelled to do”:

I was trembling all over but I had to keep going so I bent over and felt those tiny heads and realized to my horror that the kitten were still stirring and so, just like that time in the winter, I took the axe I used to split wood…

The reality of what Hrabal has done terrifies him. Looking down at the “mishmash” of what’s left of the dead kittens, now lying in the hole in the ground he’s dug for them, they remind him of “images from Nazi mass graves.” Later that day, stroking the kittens he left alive, he realizes “that this was just like those photographs from the ghetto, where an SS officer or an executioner squad would have their pictures taken standing over a pit filled with corpses.”

It’s an appalling comparison, but one that befits the gravity of the deep rumination on guilt that follows: “Nothing could calm me, and I suddenly knew that the crime I had committed was greater than that of Raskolnikov, who beat two old women to death only to test the foolish notion that it is possible to kill and escape punishment.” Hrabal is “racked with self-loathing,” plagued by remorse, yet at the same time, he can feel his face turning “pale and ashen” at the thought of his cats producing more kittens. He doesn’t want to live without his beloved pets, but neither can he exist peaceably alongside so many of them. The only real solution would be for both him and the cats to “simply cease to exist,” but instead he has to keep killing them, which in turn tortures his conscience.

The torment he suffers is so acute that he comes close to committing suicide. But, contemplating the act, he realizes that he doesn’t want to die: “I wanted to be in the world. There were still things I wanted to write.” All the same, he’s completely preoccupied by the crimes he’s committed, likening his anguish to that of “all those who had taken part in wars and had killed millions of innocent people.” His feelings of guilt intensify when he wonders at his “audacity in comparing the life and death of cats to the life and death of people”:

Yet having realized that, my feelings of guilt for the death of those kitten and cats did not go away, because in the end I came to the conclusion that one cannot even kill a cat, let alone a person, with impunity, nor can one with impunity expel a person, let alone drive away a cat, without consequences.

*

When Hrabal began writing, he was drawn to the work of the French Surrealists. Although he departed from that model relatively early on in his career, he remained a writer always able to see—as Seghal so perfectly puts it—“the strangeness in ordinary life.” As such, All My Cats is both a simple tale about a man and his many pets, and a powerful metaphor. It’s a book that forces us to reckon with the idea that to be human and to be alive is also to be guilty and to suffer for it. This is a book about what one does when existence becomes untenable, and how guilt—as it gnaws relentlessly through us—must be carried for a lifetime.

In the epilogue, Hrabal is out walking one cold winter’s day when he comes across a swan, trapped in a frozen river. He inches out across the ice to try to rescue the bird, but she’s wild with rage, raining jabs as sharp as axe blows down on his hands with her beak. Distraught and bleeding, he retreats. He returns though, the next day with thick leather gloves, only to find the bird has perished in the night. It’s not just a coincidence, he thinks:

the swan who refused to let me save her had been placed there by my destiny, which comes from outside of one, a part, a fragment, of a message from elsewhere and that in fact, since I was capable of beating to death those cats who had so passionately desired nothing more than to be with me in the world, so this swan, whom I had wanted to help survive and be in the world, instead sacrificed herself, preferring to die, to deny herself life, to show me, not that the opposite of everything is true, but on the contrary, that the opposite of everything is not true and that once again, I was guilty, just as I had been guilty all my life, even though I did not know why or what could have been the cause.

Hrabal died in 1997, at the age of eighty-two, after falling from the fifth-floor window of a hospital in Prague, where he was being treated for severe arthritis. It was officially declared an accident—he was supposedly reaching out of the window to feed the pigeons outside—but in the run up to his death he’d become increasingly obsessed with jumping from the fifth-floor window of his own apartment. Regardless of whether the fall was an accident or Hrabal intentionally took his own life, it’s a tragic story, but in the light of the torments recounted in All My Cats, I can’t help but find something serene and consoling in the knowledge that Hrabal finally found release from the burdens of his conscience.

Read earlier installments of Re-Covered here . Read an excerpt from All My Cats on the Daily here.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

February 11, 2020

The Bird Master

The below is an excerpt from Yoshiharu Tsuge’s semiautobiographical manga The Man without Talent (translated from the Japanese by Ryan Holmberg). In keeping with the customs of the medium, both the panels and the text are intended to be read from right to left.

Yoshiharu Tsuge is a cartoonist and essayist best known for his surrealistic, avant-garde work. He began drawing comics in 1955, working primarily in the rental comics industry that was popular in impoverished postwar Japan. In the sixties, Tsuge was discovered by the publishers of the avant-garde comics magazine Garo and gained increasing recognition. He withdrew from Garo in the seventies, and his work became more autobiographical. Tsuge has not published cartoons since the late eighties, elevating him to cult status in Japan. He lives in Tokyo.

Ryan Holmberg is an arts and comics historian. He has edited and translated books by Seiichi Hayashi, Osamu Tezuka, Sasaki Maki, Tadao Tsuge, and others.

From The Man without Talent , by Yoshiharu Tsuge, translated from the Japanese by Ryan Holmberg. Images courtesy of New York Review Comics.

Redux: Film Is Death at Work

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Billy Wilder.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re watching some flicks, some pictures, some movies. Read on for Billy Wilder’s Art of Screenwriting interview, Hernan Diaz’s short story “The Stay,” and Chase Twichell’s poem “Bad Movie, Bad Audience.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And don’t forget to listen to Season 2 of The Paris Review Podcast!

Billy Wilder, The Art of Screenwriting No. 1

Issue no. 138 (Spring 1996)

I used stars wherever I could in Sunset Boulevard … The picture industry was only fifty or sixty years old, so some of the original people were still around. Because old Hollywood was dead, these people weren’t exactly busy. They had the time, got some money, a little recognition. They were delighted to do it.

The Stay

By Hernan Diaz

Issue no. 227 (Winter 2018)

I decided to go to the movies. I didn’t really care what was playing; I just wanted the sense of relief when the lights fade out and the world dissolves, the slight confusion when they are turned back up and it reassembles itself.

Bad Movie, Bad Audience

By Chase Twichell

Issue no. 124 (Fall 1992)

… In our ears the turbo revs,

the cheekbone cracks,

a stocking slithers to the floor.

Cocteau said film is death at work.

Out of the twilight a small voice

hisses shut up, just shut the fuck up.

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

The Paris Review Wins the 2020 National Magazine Award for Fiction

Kimberly King Parsons, Jonathan Escoffery, and Leigh Newman.

The Paris Review is honored to be the recipient of this year’s National Magazine Award for Fiction, recognizing in particular three stories published in 2019: “Foxes,” by Kimberly King Parsons; “Under the Ackee Tree,” by Jonathan Escoffery; and “Howl Palace,” by Leigh Newman. Nominees and winners were announced in a live Twittercast on February 6, and the magazine will be recognized at the awards ceremony in Brooklyn on March 12.

Below you can get a taste of all three stories.

From Kimberly King Parsons’s “Foxes” (issue no. 229)

What’s worth happening happens in deep woods. Or so my daughter tells me.

Her plotlines: In the deep woods someone is chasing, someone else is getting hacked. Hatchets are lifted, brought downdowndown. Men stutter blood onto snow. A cast of animals—some local, some outlandish—show up to feast on the bits. “The bitty bits,” she’ll say, “the tasty remainderings.” Good luck diverting her. Good luck correcting or getting a word in once she gets going. It’s gruesome, but this type of storytelling, I’ve been assured, is perfectly normal among children her age.

From Jonathan Escoffery’s “Under the Ackee Tree” (issue no. 229)

If you carry on like before with Reyha and Sanya and Cherie, is Sanya who will come beat down your door and cuss you while Cherie sneak out back. You’ll make promise and beg you a beg for she hand in marriage one time. Is Sanya you love, like you love bread pudding and stew, which is more than you have loved before. You love that when she walk with she brass hand in yours, you can’ tell where yours ends and hers begins. You love that where you see practical solution to the world’ problem, Sanya sees only the way things should be; where you see a beggar boy in Coronation Market, Sanya sees infinite potential.

Most of all, is she smile you fall for. Sanya’ teeth and dimples flawless and you hope she’ll pass this to your pickney, and that them will inherit your light eyes, which your father passed down to you.

From Leigh Newman’s “Howl Palace” (issue no. 230)

To the families on the lake, my home is a bit of an institution. And not just for the wolf room, which my agent suggested we leave off the list of amenities, as most people wouldn’t understand what we meant. About the snow-machine shed and clamshell grotto, I was less flexible. Nobody likes a yard strewn with snow machines and three-wheelers, one or two of which will always be busted and covered in blue tarp. Ours is just not that kind of neighborhood. The clamshell grotto, on the other hand, might fail to fulfill your basic home-owning needs, but it is a showstopper. My fourth husband, Lon, built it for me in the basement as a surprise for my fifty-third birthday. He had a romantic nature, when he hadn’t had too much to drink. Embedded in the coral and shells are more than a few freshwater pearls that a future owner might consider tempting enough to jackhammer out of the cement.

For more great fiction—as well as top-of-the-line poetry, art, interviews, and essays—subscribe to The Paris Review today.

Witchcraft and Brattiness: An Interview with Amina Cain

I met Amina Cain in the early aughts, when I took over her spot as roommate to a mutual friend in a Wolcott walk-up in Chicago. Amina would come by with her new roommates, a perfectly friendly couple who nonetheless seemed rather fancy to me, as did anyone back then who talked easily about Roland Barthes. But Amina was not fancy; if anything, she had a sort of radical simplicity. Long before I’d read her writing, even longer before I published any of it (my wife and I published her second book through our press, Dorothy, in 2013), my impression of Amina was of a unique soul, quietly pursuing thoughts and concerns outside the more or less conventional life everyone else was living.

People change—I, for one, have come to love reading, teaching, and talking about Roland Barthes. But Amina seems less to have changed than to have become more fully the person she always was, with this important difference: over the interceding years, she has beautifully articulated her vision in two story collections and, now, a novel.

Indelicacy, out in February from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is a work of feminist existentialism, or existentialist feminism—searching, like Lispector, and lucid, like Camus. The story follows Vitória, a poor cleaning woman at an art museum, who marries into money and begins a journey of artistic self-discovery as she navigates society, friendship, and marriage. It is a novel about class and art, about the roles available to women and the instinct for something more. In 176 nimbly woven pages, it brings together many recurring themes or concerns of Amina’s earlier work, things like looking, walking, art, freedom, self-awareness, silence, and the possibilities of life outside the patriarchy.

This interview was conducted by email over a couple of weeks in December.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a story about how the young Donald Barthelme, wondering what sort of writer he wanted to be, attended an early performance of Waiting for Godot and discovered in Beckett a path toward his own sound. Not his voice or his style, but his sound, like a musician. Like Miles Davis or Thelonious Monk. Miles didn’t just have a style, he reimagined what a trumpet sounds like.

In thinking about what makes your writing unique, the best starting point I’ve come up with is that you have not just a voice, but a sound. I suspect that what I experience as your sound has as much to do with your attitude toward literature as with the particular words you choose to use, so I wanted to ask first about your relationship to writing in this general way—what sort of experience does writing give you and what sort of experiences do you hope your writing will give others?

CAIN

I like imagining Barthelme making this kind of discovery while watching Waiting for Godot. I’m so used to talking about voice and about tone, but I think you’re right, sound more specifically comes into it, too. To consider sound when thinking about fiction is reorienting in a really nice way, and it may actually be what’s drawn me to certain writers, that I’ve heard the sound of their writing so strongly and satisfyingly in my mind. And some stories and novels do that more than others. Sometimes, as a reader, you’re just sinking into the world or space that’s appearing before you, or you’re urged on by the story, but sometimes fiction presents itself in this other way as well, to be heard.

I’m happy to think that my writing has a sound. I certainly hear it when I work, and when writing is going well, I’m pulled along by it. Sometimes I whisper or mutter what I’m writing. With particular sentences, it feels like I am in them somehow, or that they are taking me over, that I am sitting at my desk with them, that they are part of what gives me access to a story. In order to write at all, I suppose I need this kind of experience, to be possessed by something, carried along, and this is what writing gives me, a kind of space that becomes more animate and striking than the physical space I’m in, or that joins with it. And in turn this is probably what makes me continue to write, to have access to this kind of moment, which sometimes feels closer to experiencing a work of music or art than reading. I want the reader to be able to encounter this kind of moment as well, and I hope I’ve been able to do that. On a very basic level, I want to create experience itself for readers, not just a narrative, whatever that experience ends up being for them.

INTERVIEWER

You mention space—“a kind of space that becomes more animate and striking than the physical space I’m in”—and that was my other jumping off point, your interest in spatial experiences, which is so much a part of Indelicacy. Before we turn to Indelicacy, though, what are some different ideas about narrative and space that you’ve been drawn to in others—Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, for example—or pursued in your own work?

CAIN

To be honest, I think that spatial experience is something I’ve just naturally been drawn to in my life, in many different parts of it. A few years ago, I realized that I am often trying to get to the same thing—a kind of emptied out space—not only in my writing, but also in the rooms of my house, or in a landscape like the desert, which is part of why I moved to Los Angeles, to be near it. Though I don’t enjoy the act of cleaning, I do it a lot in order to clear away clutter and dirt, to make a space feel clean and spacious. And I can’t really write if my house is messy. In the same way, I like getting rid of sentences or passages or whole sections in a text. It’s not that I want to get rid of everything so that nothing is there, it’s just that with only a few objects or images present, you can really see them, and together the objects (or the images) can join to make something new. I suppose that’s a kind of theory. It’s probably why I like so much novels like Marguerite Duras’s The Ravishing of Lol Stein, or Clarice Lispector’s The Apple in the Dark, for their different ways of feeling emptied out. I just read a new novel by writer/artist Susan Finlay called Objektophilia, out in the UK with a press called Ma Bibliothèque, and while it is actually quite filled to the brim, there is still an airiness to it, which comes perhaps from its sound, and I love how it sees space, almost as a medium for objects to appear. There is a narrative, but it really does seem to exist as a way to “exhibit” these objects. It’s fascinating.

INTERVIEWER

In Indelicacy, one place we see your interest in space is in your protagonist Vitória’s intense, imaginative looking. In front of a painting, she thinks, “I was there in that village, though I was also still in my seat, completely taken in, the way I was so often taken in by scenes in paintings.” She transcribes what she sees in paintings, and through these transcriptions she teaches herself to write, and ultimately starts to write about other things, her life. I’m interested in the role that looking plays in Vitória’s development as an artist and a person.

CAIN

The novel was written very much through a process of looking at and describing art, as well as objects, like clothes and jewelry and furniture, and buildings, and nature, and weather. And it’s very much about that development of Vitória as a person and an artist/writer, as you say, through this kind of looking. It is the way in which she makes contact with the world, finds her place in it, and feels alive. Her looking is active, the first part of her writing process. I’ve always been drawn to the idea of not separating art from life, that a person can live creatively, not just in what s/he does, but in how s/he sees. If we really look at things in our own lives, like palm trees and mountains, for example, we see that they, too, can join to form a strong image together. Then something new is created for us, and that can be a backdrop to our lives, like the set of a play.

So Vitória is transcribing the paintings she sees, but she is also transcribing a reality for herself, and the paintings and other objects begin to make up the imagery of her life, as well as her writing. She finds them so pleasurable that they intoxicate her, drive her to writing. She wants to go further into what looking at them gives her. For her, there’s almost an addictive quality to all of this.

INTERVIEWER

She’s a superbly complex character, Vitória. In some ways she’s like a child, full of wonder and selfishness, and in other ways she’s like a witch, dangerously individual and free of social expectations. She compares herself at various points to each. Looking at a painting of noblemen and witches, for example, she wonders if she is a witch or a noble. To me it seems clear that she’s a witch, if only because she casts the most wonderful hexes, like the curses of an ingeniously cruel child. To a pair of arrogant male writers, she says, “When you open your mouths, you are male worms eating from a toilet.” She is also, of course, a writer. Is a writer someone who is both a child and a witch?

CAIN

What a good question! I think a writer probably has to be many things, and that a child and a witch are two of them. In order to write, do we not need to be infinitely free? A novel attached to social expectations sounds terrible. Even if we, as people, sometimes get caught in them ourselves, our writing never should. For me, writing is relieving because within it I can leave all of that behind. And I believe that writing is an alchemical process, or at least that it can be, and maybe it is close to witchcraft in that way. If you believe in writing as art, as I do, then you know that something can happen that has very little to do with notions of craft in the ways we usually talk about it. I hate the word craft when it comes to writing, and also words like tool and toolbox, which makes writing sound so boring and utilitarian. But if craft is attached to witch, maybe I can use it. And as writers, we of course have to be interested in the world, even fixated, in order to enter a childlike, dreaming space of it. But also, I am interested in brattiness, and I wanted to explore that in the character of Vitória. I wanted to explore her flaws.

INTERVIEWER

She is a brat, but in a kind of heroic way, I think. By the way, at no point did I feel tempted to read Vitória as you, though for some reason I did come away feeling that many of her opinions are, in fact, your opinions. At the same time, I know from my own writing that whenever I include ideas or opinions that I think of as mine, they suddenly aren’t anymore. They become the character’s ideas, and I’m left largely idea-less, which I don’t mind at all. How do you feel about Vitória’s ideas and opinions?

CAIN

I do share many of Vitória’s ideas and opinions, it’s true, but going back to the idea of flaws—I also wanted to look at her blind spots, and the self that isn’t, and maybe never can be, fully formed. Her outspokenness is important because it’s one of the ways in which she moves toward freedom, and pushes off repressive expectations for how she should be and live, but I also enjoy humor, and not making fun of my characters, necessarily, but in having fun with them, and engaging in a certain amount of absurdity. Sometimes my characters say ridiculous things. So her ideas and opinions exist in different ways for me. I also wanted to challenge this notion that a protagonist should go through a major change in the course of a novel. Vitória does change, certainly the circumstances of her life do, but at the end she is still flawed, we are always still flawed no matter what changes we go through. There’s not another side we can get to in which we are completely transformed, but the people who like to say what fiction should and shouldn’t do perpetuate that myth.

As you might have noticed, Vitória’s opinions of men are not great. In general, the male characters in Indelicacy, as well as in my stories, especially husbands, are flat and undeveloped, or annoying, and yet I have a husband who is anything but, who is very good, and male friends to whom I feel close. The goodness of men is not what I wanted to explore in the book. Men, and the institutions and ways of being they’ve established, are part of what Vitória must push off to be free. She must also push off women tied to these systems, who compete with other women, or who she thinks are shallow. These are my opinions, too, for sure, but they are larger than me.

INTERVIEWER

She also has strong feelings about class, and the book’s engagement with art is inextricably tied up with all the questions raised by Vitória’s unexpected encounter with wealth, which she embraces and resists in specific ways. Artistic desire is not class-bound for her, but access to certain kinds of art—dance, opera—and time to make her own art certainly are.

CAIN

Yes, it’s not until she’s married a rich man that she even has the chance to go to the ballet and the opera. On her own, she’d never be able to afford them, and yet they, too, make her want to write, and become part of her process of writing. Luckily she finds inspiration as well in the image of a simple wreath hanging on a door and wood stacked next to it for a fire, and the sparseness of her own rooms, but it’s a privilege she doesn’t take for granted to be able to look at stage sets, and experience dance performances, and take dance classes, and go to concerts.

Early on in the book she says of herself, “I wasn’t seen as someone who could say something interesting about art. I wasn’t seen as someone who could say anything at all and then publish it.” So there’s that aspect as well, a class barrier that makes her invisible. No one expects her to be an artist or a writer; no one sees her in that way. She is looking all around her, but until her future husband first notices her, no one is looking back. She is not a perfect person—later she remarks that she makes people invisible, too. She is very judgmental. No one looks at her friend Antoinette, who is also poor, either, which is something Vitória notices kind of bitterly. So there’s a lot about seeing in the novel, and a lot about not seeing, too.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve been a story writer up to now, and I’ve always loved seeing how you make use of the space of a story. But in reading Indelicacy, it was exciting to watch you embrace the breadth and freedom of the novel form. What drew you to work on a novel? How was that experience different?

CAIN

The desire to work on a novel started, I think, when I was writing Creature. Even though that book is a collection of short stories, I found myself within them moving closer to a singular narrative voice, and a more singular sensibility. That seemed important to pay attention to. I love the short story form, and I love writing stories, but I wanted to stay in something for a longer time. I also wanted to challenge myself as a writer, to try to inhabit the space of a novel, to see what happened when I was in it. That said, I found it really hard at times. I’m not an ideas person, and I certainly don’t begin with them. I wait for a piece of writing to make itself known to me while I’m working on it, so to start with such a blank slate, larger than it ever had been with a story, was daunting. Also, though I’m not a plot-driven fiction writer, Indelicacy does have more of a plot than my short stories, and as my wonderful editor at FSG, Jeremy Davies, said so well when I was having trouble tying things together toward the end in a way that felt right to me, “you unwittingly wrote a plot, and now you have to deal with it!” I’m paraphrasing. I don’t know if he said it in exactly that way, as he’s very witty, and I probably can’t reproduce that here, but he was right. Wrangling plot is my least favorite part of writing, and I felt I could ignore it a bit more in my stories. In that way, short stories offer me more freedom than the space of a novel does.

Though now, strangely, the short story form feels foreign to me. I don’t think it always will be. Maybe any form feels distant and mysterious when you are not in it.

INTERVIEWER

In fact, that was my last question, to ask, now that the book is done, where are you now, what are you doing? Not necessarily what are you working on, but what are you thinking about, or looking at.

CAIN

Well, I am reading a lot, and thinking about fiction, and trying to write essays on what I read and think about. But recently, currently, I am also looking at wildfires and smoke, whether in my own state of California, or in images from afar, in Australia. It’s not what I want to be looking at, but it’s certainly what I see, and for the first time, I’m asking myself what kind of writer I will be, can be, in this time of climate crisis. Yesterday I read an article by Emily Raboteau in New York Magazine called “This Is How We Live Now,” in which she records all of the conversations she had with people in 2019 about climate change and anxiety. It’s a hard piece to read, but hopeful in terms of how much people actually wanted to talk about it. I want to keep talking about it also, in order to, as Raboteau says, “make private anxieties public concerns.” I don’t think we should keep them to ourselves, which is a way of making them invisible. And for me, this is changing the space of writing.

Martin Riker is the author of the novel Samuel Johnson’s Eternal Return. His critical writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the London Review of Books, TLS, and elsewhere. With his wife, Danielle Dutton, he co-runs the publishing house Dorothy, a Publishing Project.

February 10, 2020

Zane Grey’s Westerns

Revisited is a series in which writers look back on a work of art they first encountered long ago. Here, Rae Armantrout revisits Zane Grey’s novel Riders of the Purple Sage.

As I mentioned in my Art of Poetry interview in The Paris Review’s Winter issue, my mother loved Westerns, especially Zane Grey. Only a few books were available in my household, and I read whatever I could get my hands on. Some, like The Grapes of Wrath, were forbidden—but I was allowed to read Gone with the Wind and Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage. Presumably these were considered wholesome. This is highly dubious in both cases.

The Paris Review asked if I would write something about Riders. Because I hadn’t read it since I was around twelve, I remembered very little. When I reread it, I was surprised. Wikipedia says that this is the book on which the Western genre was founded. To me it seems more like a romance novel set in the West. To say the least, sex is in the air. Perhaps this is why the sage is so continuously purple. (I counted six uses of the word purple in the first page and a quarter.) I began to wonder if this book was the origin of the phrase “purple prose.” This ambient sexual tension is all I remembered about the book from my first pubescent encounter with it.

The plot centers on two couples who clearly want to have sex but never do. I remembered that much. What I didn’t recall, what appears to have made no impression upon me at the time, is that the book is an anti-Mormon tract. It is set in southern Utah where “gentiles,” or non-Mormons, are threatened, harassed, and impoverished by the Mormon townsfolk. I don’t know how that part slipped my mind. I was living in an evangelical household against which I was already in rebellion, and the theme of defying religious conformity should have made a larger impression on me.

Of the four main characters, only one, Jane Withersteen, is a Mormon. She is unusual in that she’s a single woman who has inherited and operates a large cattle ranch. This, of course, gives her a measure of autonomy that offends the Mormon elders. The bishop of the nearby town wants to force her into polygamous marriage, but she is holding him at bay. I don’t want to spoil the plot for you (just joking, I will). As the book opens, the bishop and his henchmen are threatening Bern Ventners, a “gentile” ranch hand Jane has taken a liking to. Just in time to save the day, a mysterious stranger appears and undertakes to defend the outnumbered cowboy or, as the book always puts it, “rider.” (Just as the sage is always purple, the ranch hands are always “riders.”) The mysterious stranger is, almost needless to say, an infamous “gunman” called Lassiter. Someone recognizes him and the attackers decide to drop the fight. Actually, the Mormon elders decide to let a band of local rustlers led by an outlaw named Oldrig do their work for them. To defend herself, Jane decides to keep Lassiter around, although she also fears he will murder many of her fellow citizens.

I do seem to have strayed pretty far into plot summary. The more important thing, certainly for me as a young girl, was the constant atmosphere of sexual threat. The Mormons are said to hold women prisoners. The outlaws are rumored to kidnap them. Sexual slavery is always in the background, though never named as such. Fortunately, there is Lassiter and his “big, black guns” to hold it off. The guns are always described in terms of their large size. Jane swoons several times in the book, including at the sight of the guns. This despite the fact that she is often portrayed as an independent, strong woman.

In one fracas, Bernt Ventners shoots Oldrig’s infamous “masked rider,” a horseman who makes terrifying runs through the Mormon villages without, it seems, actually harming anyone. Still, rumors abound about the fearful deeds of this desperado. When Ventners goes to check on the outlaw he’s wounded, he discovers, only after removing the mask, that “he” is really a slender young girl called Bess. This is the other thing I remember about the book. I was very much interested in the idea of an outlaw girl who was an expert rider. Ventners feels terrible about having shot a woman so he patches her up. After she says she wants nothing more to do with the rustlers, he undertakes to carry her to safety. He carries her to a hidden, paradise-like valley he’s found and nurses her back to health. Even so, he is rather squeamish about her because he assumes she is “bad,” which seems to mean guilty (?) of having been raped. Worse, she admits to loving the gang leader, Oldrig. But then, pages later, comes the revelation that she is Oldrig’s daughter, thus eliminating any chance of sexual abuse (at least in the quasi-Victorian mind of Zane Grey): “She was the rustler’s nameless daughter … He had so guarded her … that her mind was as a child’s. … That was the wonderful truth. Not only was she not bad, but good, pure, innocent.” His passion for her grows, spiced by his memory of her as an outlaw boy. She is an emblem of potential female empowerment in the book, as is Jane Withersteen, but the narrative allows neither to hold onto her freedom for long.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the gunman Jim Lassiter is falling in love with Jane. He is quite the gentleman, though, and she doesn’t suspect his feelings at first. She sees him as her protector. Despite his protection, however, her “riders” defect and she loses both her cattle herds. Then Fay, the orphan girl she’s raising (did I mention her?), is kidnapped. Finally, at the height of her desperation, she realizes that Lassiter loves her—and she begins to love him in return. Sounds like a happy, if convenient, ending. But we’re not quite through yet. While escaping from a posse of Mormons, Lassiter and Jane come upon Fay’s captors and Lassiter kills them. Now with the child in tow, the twosome become a sort of nuclear family. Here things take a rather disturbing turn, at least for this reader. Despite the novel’s flirtation with unconventional roles for women, Lassiter takes Jane to the secret valley (Ventners and Bess are gone by then. Don’t ask.) and rolls a balancing boulder down a mountain, causing an avalanche which imprisons the not-yet lovers and the girl in the paradise valley forever. Yes, when pressed, Jane consents. But it’s notable that she is described as stunned and passive. “Like an automaton she followed Lassiter down the steep trail of dust and weathered stone.” This is the novel’s most extreme form of female imprisonment yet. Lassiter has saved Jane from (purportedly) oppressive Mormon marriage so that he can have her to himself for the rest of their lives. Let’s not even imagine Fay’s life or the lives of the children Jane and Lassiter may produce! Riders of the Purple Sage, after flirting with unconventional roles for women, ends by closing off such possibilities with the literal thud of an avalanche. Now that’s melodrama!

Given that the novel’s ending promises (or threatens) a kind of romantic imprisonment, I wonder if the book’s audience skewed male or female. Does anyone, of any gender, truly want this? My mother, though she had a job at a time when most women didn’t, shared a small house with an abusive husband. I wonder if she read Grey’s books as an escape from her circumstances. If so, I can’t help but find it ironic.

Read our Art of Poetry interview with Rae Armantrout, and her poems “The News,” “Array,” and “Contrast” in our Winter 2019 issue.

Rae Armantrout is the author of over a dozen poetry collections, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Versed.

February 7, 2020

Staff Picks: Scenes, Screens, and Snubs

Still from Mark Jenkin’s Bait.

This Sunday the Oscars, like seasonal depression or unwashed salad, returns with a grim inevitability. It also provides a good juncture to rave with righteousness about films that were overlooked. I wrote about Atlantics two weeks prior and would be happy to rattle on about its snubbing, but I have other reasons to shake my fists. Also ignored was my other favorite film that ends with a freeing glance into the camera, the wry and ruthless The Souvenir, with a scalpel-sharp script in my mother tongue, passive-aggressive British condescension. The marvelous oddity Bait charts the battle between a Cornish fisherman and the gentrifiers of his town. They buy him out of his house and drag it up with nautical kitsch and knotted ropes—“like a sex dungeon,” he fumes. Bait has the “fuck the rich” fury of Parasite but is filmed as a throwback, in grainy black-and-white film stock, with dubbed sound. The abrasive aesthetic unsettles: it drains the familiar romance of Cornwall’s coast and shows the present as if it were a prophetic nightmare from the past. Another bewildering experiment is the gorgeous Long Day’s Journey into Night, which should have got a nod for every technical award. It is a lonely man’s reverie, as expected, full of the flickers and fragments of lost love. There is weeping and gnashing of apples. There are curlicues of cigarette smoke and telling smudges of lipstick. Lovers speak vaguely in flooded rooms, as if this were a perfume ad directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. Then it all converges in a single take: an hour-long dreamscape that gathers and riddles all that came before. The camera loops and plummets; fate is tempted as a horse bucks fruit into its path, and a man bets he can sink the eight ball in the pool hall. It’s no spoiler to say the spell does not break—this melancholy is intoxicating, immaculate. If only real sadness felt so good. —Chris Littlewood

I understand the Academy doesn’t love a horror flick (in ninety-two years, all of six have been nominated for Best Picture), but that doesn’t mean I can’t be miffed that Jordan Peele’s excellent Us didn’t get any nominations. It’s probably too late in the week to start a write-in campaign for Lupita Nyong’o to win the Best Actress statuette, but she deserves it, playing the twinned characters of Adelaide and Red with precision, ferocity, and intelligence. Sure, there are some scenes that recall The Parent Trap, but in Peele’s commanding hands even this old trope is fresh, and Nyong’o has both sides of the face-off on lockdown. “Old made fresh” could be applied to almost every angle of how Peele approaches making a horror flick in 2019—the suspense and the slash, the sinister and the silly. —Emily Nemens

Still from Murray Lerner’s Festival!

I lived in Newport, Rhode Island, for four years and never attended the Newport Folk Festival, which has happened every summer since 1959. It always felt distant, with its crowds of tourists and bands that are popular on the radio. Not until a screening this past December of Murray Lerner’s documentary Festival! did I understand how the event was once distinguished by a shared feeling of intimacy. From 1963 to 1966, Lerner recorded American bohemianism as enacted by young people of all class backgrounds (the cross-sectional fashion sense of this set is the reason for the movie’s inclusion in a series of films curated by the fashion designer Anna Sui at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York). Much of Festival! is spent on the performances of now-iconic musicians (Peter, Paul and Mary; Johnny Cash; Bob Dylan; Donovan) and the moments afterward. Joan Baez talks over her shoulder to Lerner and his camera, riding in the back seat of a car, about celebrity, how antithetical to folk music it feels to be idolized. Lerner’s lens is an equalizer; the reverent eye trained on Baez is the same one that lingers on attendees sleeping under their sweaters in the early-morning dew. Whether it’s the cultural moment itself or Lerner’s perspective that defines the scenes in Festival!, neither would have been possible for me to experience during my own coastal tenure, making the documentary both art and artifact. —Lauren Kane

The Farewell was staff picked by my predecessor Noor Qasim after its 2019 release. But upon the Academy’s decision not to nominate Lulu Wang for Best Director, the praise bears repeating. Wang tells the true-to-life story of Billi’s (Awkwafina) return to Beijing to say farewell to the family matriarch, Nai Nai (Zhao Shuzhen), who has been diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. But here’s the kicker: everyone except Nai Nai knows the gravity of her condition. And to keep it hidden, Billi’s trip is planned around a sham wedding banquet for her cousin Hao Hao and his girlfriend of three months. Perhaps the most striking element of the film is its soundtrack, a spare classical score that places Wang in the tradition of Robert Bresson. Wang’s wide shots are as precise and intentional as the music; she is unafraid of stillness and tableau, allowing the viewer uninterrupted immersion in her painterly world. Wang’s genius aside, Awkwafina is an intelligent and beautiful actor, as is Shuzhen, and each surely deserves award consideration. It is an injustice that The Farewell has been overlooked, and a clear indicator that the Academy often fails to recognize moviemaking at its highest level. —Elinor Hitt

Time moves fitfully in the films of Angela Schanelec. Locations change abruptly, and characters’ relationships with one another remain unexplained, understood only through minimal context clues. Her plots don’t exactly follow dream logic, but they’re made to be absorbed rather than articulated. Fittingly, I cannot explain exactly what it is that I love about her films, because after one watches them, they have a habit of evaporating; their events elude memory, becoming felt instead of known. It is this feeling of being imprinted upon that keeps me watching her work, and it’s what makes me so excited for the Schanelec retrospective that Film at Lincoln Center is showing beginning today, February 7. The program honors the release of her latest film, I Was Home But … , which won the Silver Bear at last year’s Berlinale. But I can’t imagine Schanelec winning any accolades stateside—her films are the antithesis of Oscar bait. I am reminded of the abrupt, unexplained location change from Marseilles to Berlin halfway through Marseilles (2004) or the theater scene, shot from the perspective of the stage, that opens Afternoon (2007), itself based on Chekhov’s The Seagull. In one of Schanelec’s earlier movies (and a personal favorite), Passing Summer (2001), the main character spends her summer at home in Berlin after her friends depart on vacation (the film also features a charming dance sequence). And there will be more shown at this retrospective that I haven’t seen, including a series of shorts and Schanelec’s debut feature, My Sister’s Good Fortune (1995). “It doesn’t make sense to explain anything,” Schanelec told an interviewer in 2019. For me, it’s this sense of the unexplained, this refusal to make things easy, that is one of her films’ most alluring qualities. —Rhian Sasseen

Maren Eggert in I Was at Home, But … Courtesy of Cinema Guild.

Cooking with Hilda Hilst

In Valerie Stivers’s Eat Your Words series, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

“ … oh I only know about God when I enter the hairy mouth of the wild sugar apple … ” Hilst’s creative use of foodstuffs to mean genitalia is one of the joys of her prose. Here, an engorged chayote rests suggestively against Hilst’s novel The Obscene Madame D.

The recipe for the work of the Brazilian author Hilda Hilst (1930–2004) is equal parts language and nonsense, obscenity and literary references, disparagement of writers and striving toward God. It’s thrilling to read but challenging as narrative, which is perhaps why Hilst is famous in her own country but not in ours. Despite a fifty-plus-year career and a sweep of honors, Hilst wasn’t published in English until 2012. If she’s known at all in the U.S., it’s in the shadow of the Brazilian grande dame Clarice Lispector, who worked in a similar vein.

My favorite of Hilst’s novels, Letters from a Seducer (1991), is the centerpiece of a late series often considered her masterwork. In it, Stamatius, a homeless writer, begs on the street for “everything that you are going to throw in the trash, everything that isn’t worth a dime anymore, and if there’s leftover food we still want it.” Hilst’s work resists quotation; it’s difficult to find a place to stop. Every line is a pirouette. The passage continues: “The burlap sacks fill up, bric-a-brac books stones, then some people put rats and shit in the bag, what faces those rats had, my God, what injured little eyes those rats had, my God, we separated everything out right there: Rats and shit here, books stones and bric-a-brac there. Never any food.”

Stamatius’s perspective bookends a series of letters of obscene invective—we assume he’s found or stolen them—from a man named Karl, a slick bourgeois, to his sister Cordélia, who has retreated to a nunnery, perhaps to get away from him. These letters begin: “Cordélia my sister, come out of your cloister. / the countryside ages women and cows. / Once again nourish your holes / With gentle swine-cresses, blunt poles / Or if it’s pussies your tongue wants / I’ll get you dozens: mature cunts / Youthful cunts, purple cunts / for your vile, repressed feelings.”

“God himself, with the face of a wanderer … was displaying I know not what …a pink and kitsch enough giant chorizo, decorated with stars.”

Hilst’s work teems with literary reference—pull any string and you’ll go far—but the one that jumped out at me most was Søren Kierkegaard. The Danish religious philosopher’s masterpiece, Either/Or, is a series of papers passed between A., an aesthete, and B., an ethical man, and has a doubly found, possibly fictional passage nested within called Diary of a Seducer, in which the aesthete’s life philosophy is put in to action, repugnantly, in order to seduce a young girl named Cordélia. How we are to judge him is one of the book’s many puzzles.

Hilst’s Letters from a Seducer isolates this section from Kierkegaard’s masterpiece and makes it avant-garde, bringing Kierkegaard into the company of Georges Bataille and other writers of transgressive fiction, who use obscene language to shock the reader clear of their preconceptions. It’s a brilliant transmutation, since Hilst, like Kierkegaard, was also a God seeker whose work was spiritually animated by a belief in individual contact with the divine. The Hilst translator and scholar Adam Morris, writing in Essays on Hilda Hilst: Between Brazil and World Literature, explains that Hilst’s style of language is “a method of incitement aimed at her readers,” pushing us to “seek out personal contact with the beauty and dread of the divine,” which “must be known and pursued individually if one’s life is to have any meaning.” Hilst took every opportunity to deflate the self-importance of writers, but she also believed that “poetry, above all else, came closest to communicating the emotions, ideas, and other nameless affects of raw gnostic enrapture and horror.”

Hilst was not a nationalist, but these beyond-the-nut-mix Brazil nuts are the foundation for a divine fish curry.

The divine—like poetry and pornography—is one of those “I know it when I see it” situations, but for me, the beautiful, unspooling oddity of Hilst’s sentences creates the conditions in which to seek it. To take one almost at random, Karl writes: “What do you mean by ‘healthy in bed’? Now I see a certain type eating watermelons, popcorn, splayed out drooling, soiling the sheets, filling them with seeds and peanuts …” It’s such a melodic string of sounds, of freeing obscenity and silliness. We grasp, as Karl says, that the writer is following a “crazy urge to write in the fundamental language.”

I wondered what it would be like to apply that urge in the kitchen. Hilst’s “fundamental language,” to my great delight—and to the benefit of readers wanting a meal drawn from her work—employs food terms in frequently eccentric ways. Blouses smell of apples; people sell clams, oysters, coconuts, hearts of palm, dried meat; a penis is a giant chorizo or a “wise and mighty catfish” or a strawberry (!); testicles are beans; a vagina tastes like a mixture of “yellow star apples and loquats.” At one memorable moment, “The Trickster, The Whore, The Rascal, Death” tells Stamatius to “sample her codfish.”

“ …and the Little Fairy widow dressed completely in tulle, stood on the doorstep and when the little girls passed by, she would say: pretty little thing, come eat a tapioca cookie.”

I took such ingredients mentioned in the book as a jumping-off place, defying, in the avant-garde way, all bourgeois convention. These were: codfish, carne seca, pumpkin, chorizo, clams, tapioca, and popcorn. I then mixed them with some of Brazil’s iconic ingredients and dishes: Brazil nuts, cassava topping, chayote, and passion fruit. I was trying to make good food but also freeing myself to experiment. One recipe, a codfish stew in Brazil-nut milk, is fast and easy (well, easy after you order the nuts off the internet and make the nut milk) and turned out as a superb weeknight dinner—I’ve already made it again. The dish has okra (acceptable bursts of slime) and hot cucumber, plus thyme, the combination of which creates a unique, mild, intriguing flavor profile. My rice creation also ended up being wonderful. Various forms of crunchy cassava topping are emblematic of Brazilian food, as is carne seca (dried meat). I combined the two, using Brooklyn hipster jerky instead of carne seca (a trial run with the authentic Brazilian grocery-store version didn’t quite work, despite the meat being boiled and soaked for hours) and tossing both on a priapic chorizo-clam rice.

My two desserts—a spicy passion fruit soup topped with “popcorn flour” and a tapioca cake topped with cinnamon, chayote, and caramel—had moments of promise in the tasting stage but weren’t really edible. The soup was way too spicy (I’ve adjusted the recipe below to call for a mild chili instead of the one I used), and the instruction to blend the passion fruit pulp with its seeds creates speckled black grit. The cinnamon and chayote were not a harmonious combination, and the crunchy topping with the soft tapioca cake both tasted and looked (as you’ll see in the photos) wrong.

Enrapture and horror—achieved.

“Sample My Codfish” Stew, with Brazil-Nut Milk

Adapted from Brazilian Food , by Thiago Castanho.

2 1/4 cups raw Brazil nuts

2 1/2 cups water

2 fresh codfish fillets, about 7 oz (200 g) each, skin on if possible

black pepper

small chunk of winter squash, 2 1/2 oz (60 g), scant 1/2 cup when cut

small chunk of sweet potato, 2 1/2 oz (60 g), scant 1/2 cup when cut

small amount of parsnip, 2 1/2 oz (60 g), scant 1/2 cup when cut

8 okra

a small tomato, quartered

2 tbs coconut oil

1/2 tsp salt (plus extra salt, to taste)

1/2 a cucumber (or similar quantity of West Indian gherkins), peeled and cut lengthwise in sticks

2 tbs coarsely chopped cilantro

3 or 4 sprigs thyme, plus more to serve

Preheat the oven to 425.

To make the Brazil-nut milk, mix the Brazil nuts and water in a blender for five minutes, until completely smooth. Refrigerate for thirty minutes, then strain through a fine sieve and set aside. You should end up with about two cups of liquid. (Note: the nut mash left over after straining can be used to make cakes, pies, and cookies).

Clean the codfish fillets, running your fingers along the lines and pulling out any remaining pinbones with tweezers. Salt and pepper them generously on both sides, and let stand for thirty minutes.

Prepare the vegetables. The balance of this dish calls for many types of vegetable in very small quantities; it helps to weigh them out, but if you don’t have a kitchen scale, measure the processed vegetables out by the cup amounts indicated above. Do not be tempted to throw in a little extra—all those additional bits will add up.

Peel the squash, and cut into quarter-inch slices. Peel the sweet potato, cut into quarter-inch slices, then halve or quarter to make large rounds. Peel the parsnip, quarter lengthwise, remove the woody core, and cut into quarter-inch slices.

Clean your work surface and your knife, and dry thoroughly. Cut off the tops of the okra and discard. Halve the okra lengthwise, wiping the knife frequently on a towel to keep it completely dry. The less water okra comes in contact with, the less slimy it will be.

Pour the coconut oil into your largest skillet, and heat on medium-high until the oil shimmers. Place the squash, sweet potato, and parsnip in a single layer, without crowding, and sear, watching carefully and flipping when the vegetables are beginning to blacken in spots but have not yet burned. This should take less than three minutes.

When they’ve blackened on both sides, remove and reserve. Add more coconut oil if the pan is dry, then add the okra, cut side down, and blacken (only one side is fine). Finally, turn down the heat a little, and fry the tomato slices, cut side down, to remove the rawness and get some color if possible.

Place the fish in a medium-size baking dish. Top with the blackened vegetables. Sprinkle with half a teaspoon of salt. Add the cucumber, cilantro, thyme, and Brazil-nut milk, filling the dish until the fish and vegetables are fully submerged (if necessary, add a bit of water to accomplish this). Bake for twenty minutes or until the fish is flaky and falling apart and the vegetables are cooked. Serve garnished with fresh thyme.

Rice with “Giant” Chorizo and Clams

Adapted from Brazilian Food , by Thiago Castanho.

For the cassava-crumble topping:

a stick of butter

3 tbs diced shallot

1 2/3 cups untoasted cassava flour

1/3 cup beef jerky, not too rocklike (I used Brooklyn Biltong)

For the rice:

a small chorizo (uncooked is preferable)

3 tbs neutral-tasting oil

a red pepper, sliced

2 cloves garlic, sliced

1/2 cup fennel, diced

1 cup chicken stock (I use Better Than Bouillon)

a dozen clams

1/2 cup rice

1/3 cup parsley, minced

Remove the chorizo from its casing, break it up into chunks, and fry in oil in a medium-size skillet until browned on all sides. (If your chorizo is cooked already, just brown it a bit and release some of the juices in the skillet). Remove the chorizo from the pan and set aside.

To the same pan, add the red pepper, and fry on medium-low heat, five to seven minutes, until well softened. Add the garlic and fennel, and fry, stirring occasionally, two to three minutes, until the garlic is fragrant.

Add the chicken stock and the clams, cover, and bring to just a boil, then turn down to a lively simmer and steam, five to seven minutes, until the clams have all opened. Do not cook past the point when most of the clams have opened; prolonged cooking will make the clams tough.

Discard any clams that have not opened. Remove the opened clams from the pan, and set aside in a small bowl, covered under foil to keep warm.

Add the rice to the liquid in the pan. Cover and cook about ten minutes, until the rice has absorbed the liquid and small holes have appeared in the surface. Turn off the heat, and leave the rice to sit for five minutes longer.

Return the chorizo and the clams to the pan. Heat briefly to meld. Top with parsley and a generous helping of cassava-crumble topping, and serve.

Tapioca Cake with Cinnamon-Chayote Topping and Tapioca Caramel

Adapted from Brazilian Food , by Thiago Castanho

For the tapioca cake:

1 tsp vanilla extract

1/2 cup unsweetened, shredded dried coconut

2 cups whole milk

a 14 oz can of sweetened condensed milk

1 cup granulated tapioca

butter, for greasing

For the tapioca caramel:

3/4 cup granulated tapioca

1/4 cup sugar

1/8 tsp salt (ideally a tasty large-flake kind like Maldon)

To serve:

1/3 cup chayote, peeled and finely cubed

1/4 tsp cinnamon

To make the cake:

Grease a nine-inch Bundt or angel food cake pan.

Combine the vanilla extract, shredded dried coconut, whole milk, and condensed milk in a medium saucepan, and bring just to the point of scalding, stirring continually. (A scald is just prior to a boil; look for the milk to release steam and start to turn frothy at the edges). As soon as the mixture reaches a scald, turn off the burner, and stir to release some heat.

Pour the granulated tapioca into a medium-size heatproof bowl, then add the hot mixture and stir. Leave to sit about ten minutes, stirring occasionally, until the tapioca has become soft, swollen, and gelatinous and the liquid has mostly absorbed. Pour into the prepared container, and refrigerate until set, about two hours.

To make the tapioca caramel:

Set up a small nonstick pan, greased with butter or a neutral-tasting oil, next to your stove.

Combine the granulated tapioca, sugar, and salt in a saucepan, and heat gently, stirring constantly to melt the sugar. Cook, stirring, until the caramel is a light golden brown and the tapioca has begun to clump. Pour out onto the prepared surface, and let cool. Break the mixture up into smaller chunks.

To serve:

Using a rubber spatula, gently release the cake from the sides of the tin, working as far beneath it as you can without breaking it. Invert over a plate, and tap to loosen. Repeat if necessary.

Top with chayote and tapioca caramel, and dust with cinnamon. Serve cold.

Cold Passion Fruit Soup with Chili and Popcorn Flour

Adapted from Brazilian Food , by Thiago Castanho.

2 cups carrots, peeled and roughly chopped

3/4 cup sugar

4 cups water

2/3 cup passion fruit pulp (including the seeds)

a Cumari do Para or other mild yellow chili, seeded

1 tbs vegetable oil

1/2 cup popcorn kernels

Put the carrots in a saucepan with the sugar and water, and bring to a boil. Cook for twenty minutes or until the carrots are very tender. Strain, reserving both liquid and carrots.

Combine the cooked carrots, passion fruit pulp, chili, and a cup and a third of the carrot liquid in the blender. Blend on high until fluffy and completely smooth. Add more liquid if the mixture seems too thick; I like mine a little soupier and less like a puree. Chill for at least two hours before serving.

To make the popcorn, heat the oil in a large saucepan over medium heat, tossing in the occasional test kernel until they begin to pop. When that happens, add the rest of the kernels, cover, and cook, shaking occasionally, until the corn has mostly all popped. If it starts to scorch, turn the heat down to medium-low.

Remove the popped corn, discarding any blackened or unpopped kernels, and process in the blender to make a medium-fine flour. Sprinkle on the soup, and serve.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

February 6, 2020

The Collages of Max Ernst

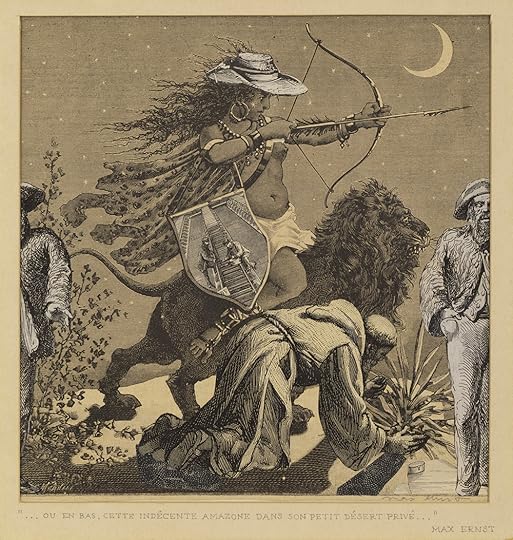

Few bodies of work represent the splintering of the twentieth-century Western psyche like the collages of Max Ernst. Striking and playful, the German surrealist’s clipped-together creations, produced throughout his life, attest to a roving eye for materials and a deep curiosity about harmony and dissonance. The art historian Werner Spies has said that “collage is the thread that runs through all of his works; it is the foundation on which his lifework is built.” A new exhibition of Ernst’s collages (on view at Paul Kasmin’s 297 Tenth Avenue location through February 29, 2020) presents approximately forty of them, some of which are being displayed for the first time. A selection of images from the show appears below.

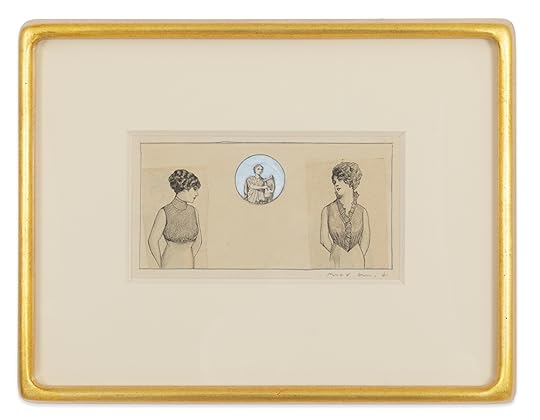

Max Ernst, Deux jeunes Dames, 1972, gouache, pencil, ink, and collage on paperboard, 9″ x 11 3/4″ x 1 1/2″, framed. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

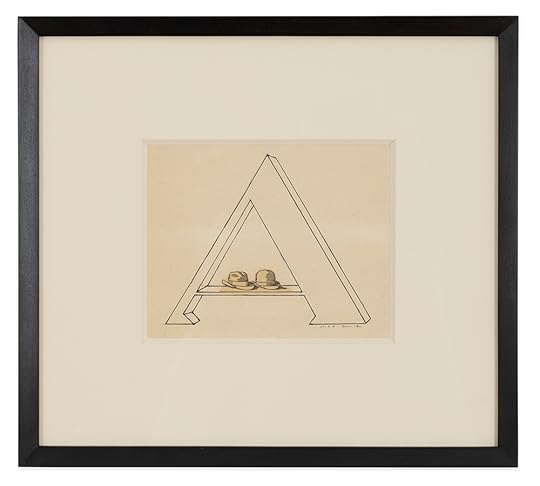

Max Ernst, Lettrine A, 1958, pen, ink, and collage on paper, 10″ x 11 1/8″ x 1 1/4″, framed. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, Clôture, 1967/1975, collage and gouache on paper, mounted on paperboard, 10 1/4″ x 6 3/4″. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, Lettrine D, 1974, collage on paper, 5 3/4″ x 4 3/8″. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, … ou en bas, cette indécente amazone dans son petit desert privé … , 1929/30, collage on paper, 8 7/8″ x 8 1/2″. Private collection. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

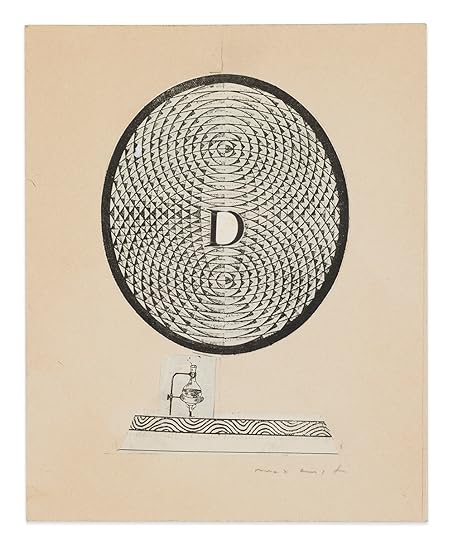

Max Ernst, Lettrine D, 1948, ink and collage on paper, 10 3/8″ x 8 7/8″ x 1 1/4″, framed. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, Les Filles, La Mort, Le Diable, 1970, gouache, watercolor, pencil, and paper collage on paper, 12 1/2″ x 9 1/4″. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, Lettrine U, 1958, pen, ink, and collage on paper, 9 1/2″ x 9 1/2″ x 1 1/4″, framed. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, Le plus beau mur de mon royaume, 1968, collage, gouache, and pencil on cardboard, 17″ x 13 1/4″. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

Max Ernst, Singe, 1970, gouache, ink, and collage on paper, 7 1/4″ x 6″. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York.

“Collages” will be on view at Paul Kasmin’s 297 Tenth Avenue location through February 29, 2020.

A Good Convent Should Have No History

Eileen Power, Sylvia Townsend Warner, and Virginia Woolf

When the visiting bishop arrives to inspect the ramshackle convent in Sylvia Townsend Warner’s 1948 novel The Corner That Held Them, he is distressed to find unmistakable evidence of unchaste activities. Instead of being greeted by peals of holy music, “his hearing had been tormented by the yelpings of little dogs and the clatterings of egg-whisks.” He finds the nuns devouring sweets in the dormitories, keeping pets, lounging on soft cushions; they wear perfumed mantles “better befitting harlots than the brides of Christ”; and this devout sisterhood appears to be “bristling with quarrels and slanders.” He considers that a household of nuns might be forgiven for careless stewardship of their financial assets, “since women are ordained the weaker vessel and have no business sense.” But when these natural infirmities are not compensated for by piety and devotion, this, concludes the disappointed bishop, is true depravity.

“A good convent,” writes Warner with knowing irony, “should have no history. Its life is hid with Christ who is above. History is of the world, costly and deadly.” The novel—which covers three centuries in the life of Oby, a small Norfolk parish—presents the humdrum minutiae of daily happenings, too insignificant (and worldly) to be recorded on the expensive vellum of medieval chronicles but making up the lives of the generations of unsung women who pass through these cloisters: the shard of eggshell found in a pancake, ants marching through the larder, intrigue over priory elections, and long nights spent in the treasury poring over accounts. The convent was founded in commemoration of a twelfth-century adulteress by a stern husband, eager that history should forget her ancient passion (now masked effectively by an ugly stone effigy), and dedicated to the patron saint of prisoners. As the nuns, bored at prayer, count up the women who have died in the convent before them, they know that their duty is to act as a group (“a flock soberly ascending to a heavenly pasture”) and retain a decorous anonymity. In any case, they see few opportunities to leave a mark on history. With the convent in the grip of poverty and all energies expended on attempts to balance revenues with expenditures, “there was no place for aberrations of individuality.” “In songs and romances,” writes Warner, “an apostate nun may be a romantic figure. God’s Mother becomes her proxy in the convent and pins up the curtain before her frailties; but in real life she is a drab like any other drab, nursing her baby and eyeing her lover and the tankards from the tavern doorway.”

“I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman,” wrote Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (1929). In that essay, commenting on the fact that women’s lives are “all but absent from history,” she argues that this is not only a consequence of the ways women have been deprived of the material conditions under which their talents can prosper but also reveals the sort of events and lives historians have traditionally considered worth remembering—primarily, the public activities of “great men.” Perusing the index of G. M. Trevelyan’s History of England, Woolf looks up “position of women” and is dismayed to find only a smattering of references, mostly to customs of arranged marriage, wife-beating, and the fictional heroines of Shakespeare. Flicking through chapters on wars and kings, she wonders why so little room is left for women’s activities in the events that “constitute this historian’s view of the past.” It was clear to Woolf that new histories were needed, which would examine the reality of women’s lives, their relationships and activities, and the forces that thwarted their ambitions. In the last year of her life, Woolf began work on a history of English literature that would uncover a range of “anonymous” voices from the past. As bombers zipped low over her Sussex home, Woolf immersed herself in reading about witches, nuns, poets, actresses, servants, and governesses, eager to draw these “lives of the obscure” together in an alternative portrait of English society, which would expose the way history was constructed and the voices it excluded. Looking for erudite, imaginative history writing that performed a similar excavation, she reread the very book to which Warner would turn a few years later when composing The Corner That Held Them: an imposing seven-hundred-page tome titled Medieval English Nunneries, by a young economic historian named Eileen Power.

Born in Cheshire in 1889, Power had studied at Girton, one of Cambridge University’s first women’s colleges, where she spoke at suffrage meetings alongside the leading feminists of her day. After a spell reading medieval history at the Sorbonne in Paris, Power received an offer of a fellowship at the newly established London School of Economics on a grant given specifically to support research into women’s lives, in the hope that the monographs produced by fellows would form a much-needed canon of women’s history. Power joined a radical faculty abuzz with new ideas for how history could be written.

In the early years of the twentieth century, the fight for equal suffrage had sparked a growing interest in women’s history and working-class history. Frustrated at their political disenfranchisement, women looked to the past for models and alternatives, eager to reread history through the lens of gender and power and to establish a historical framework from which to agitate for change. Power and her contemporaries—among them the historians Alice Clark, Vera Anstey, and Ivy Pinchbeck—huddled over Olive Schreiner’s 1911 book Woman and Labour, which argued that capitalism had systematically eroded women’s productive labor and thus their independence; they devoured the work of Cambridge classicist Jane Ellen Harrison, whose groundbreaking studies Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1908) and Themis (1912) proposed that the origins of ancient Greek mythology and religion lay in much older worship, centered around the worship of powerful mother goddesses. When ideology wanted to confine women to the domestic sphere, Harrison suggested, these strong, public goddesses appeared to be a threat to state order, and so their powers were subsumed into new cults dedicated to male gods like Zeus and Dionysus, who reflected not only human form but also man-made hierarchies. The prominence in subsequent art and literature of the rationalized Olympian pantheon—the family of gods headed by the almighty, adulterous patriarch Zeus—was testament to the gradual erosion of women’s importance in Greek society. What’s more, it erased the experience of generations of ancient women whose religious activities had been considered essential for community survival. Harrison’s books offered proof that women’s subordination was not based on any “natural” order but had been carefully and deliberately constructed over time. When Woolf notes in A Room of One’s Own that “until very recently, women in literature were the creation of men,” she cites “Jane Harrison’s books on Greek archaeology” as an example of how writers are starting to “write of women as women have never been written of before.” Eileen Power, too, took inspiration from those earlier works as she researched Medieval English Nunneries.