The Paris Review's Blog, page 188

January 21, 2020

A Slap in the Face of Stalinism

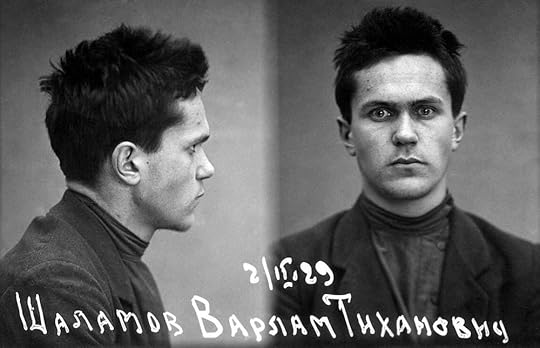

Varlam Shalamov in 1929. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“Every story of mine is a slap in the face of Stalinism,” Varlam Shalamov wrote to his friend Irina Sirotinskaya in 1971, “and like any slap in the face, has laws of a purely muscular character.” He returns to the idea a little later in the letter, contrasting his own ideal of prose to the expansive “spadework” of Tolstoy: “A slap in the face must be short, resonant.” Most of Shalamov’s stories are indeed short, some extremely so, and constitute an argument both with the great nineteenth-century Russian novels and with the wretched ones of the Stalinist era that sought to pour the pap of socialist realism into a pseudo-epic form. The slap works simultaneously as a figure for aesthetic form and political protest, and in Shalamov’s late essays and letters, it functions as a motto of sorts, a creed of laconic defiance echoing, distantly, the Russian futurist manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste and—more intimately and immediately—the famous opening of Nadezhda Mandelstam’s memoir Hope against Hope: “After slapping Aleksey Tolstoy in the face, M. immediately returned to Moscow.”

Mandelstam sent the manuscript of her memoir about life with the poet Osip Mandelstam to Shalamov in 1965, and while neither could hope to publish their prose in the Soviet Union at that time, the two established in the correspondence that followed a shared sense of purpose. He writes: “If I had to give a literature course on the second half of the twentieth century, I would start by burning all the textbooks on the podium, in front of the students. The link between eras, between cultures has been broken; the exchange has been interrupted and our mission is to pick up the ends of string and tie them back together.” She replies: “I don’t think we should burn textbooks: it’s too classical a gesture … Let’s just not use any”; her main concern, too, she writes, is “the link that connects one era to another, the only thing that allows society to be human, a human being to be human.”

The task Shalamov took on as a writer was what Osip Mandelstam in the celebrated and chilling poem “The Age” (“Vek”) figured as piecing together the broken back of an animal.

My age, my beast, who will look you

straight into the eye

And with his own blood fuse

Two centuries’ vertebrae?

Shalamov conceives of his writing not only as an act of witness (to a crime) but also as an act of healing or at least of treating an illness or injury. The crimes of Stalinism were committed by a country against itself, in a self-consuming process by which each generation of executioners soon became the next group of victims. Giving an account of the gulag means finding a form for a suicidal cycle of alienation and death. What is being documented has no end, either logically (since to rid the Soviet state of all its possible “enemies” Stalin would have had to exterminate every single citizen) or historically (there was no liberation of the camps, no formal end to the system, even after Stalin’s death and Khrushchev’s denunciation). The literary means to find an escape from a vicious cycle is necessarily elliptical. A narrative slap in the face, as opposed to a physical one, is the opposite of mimetic violence: it is a transformation of pain into artistic form—a form that, like a set fracture, makes the bone stronger than it was before.

But the Stalinist years brought with them—along with the torture, starvation, and destruction of millions of human beings—an assault on language that systematically subverted and diminished the power and viability of words. To resurrect the dead in living memory Shalamov had to bring words back into an organic relation with reality. He found help in the Acmeist movement to which Mandelstam had belonged, the work of a group of poets reacting against the mystical vagaries of symbolism and striving to plant poetry firmly back in the soil of the physical, perceptible world. The essays that Shalamov wrote alongside his stories in the fifties and sixties—including one titled “Diseases of Language and Their Treatment”—are his continuation of that struggle. In their polemical, battle-ready tone and their call for a “new prose” equal to the new crisis conditions of Soviet life, they bring to mind the manifestos of the prewar avant-garde. Challenge and disputation are methods of “tying the ends together” no less than reverence and emulation.

Shalamov’s insistence on the direct participation of literature in life has its roots in the twenties, when he was a student and, briefly, a journalist in Moscow. Few environments in modern history can have been more exciting to an aspiring writer than the Moscow of those years, a revolutionary city teeming with artistic movements, publications, performances, and quarrels. The futurist movement, the radical formal explorations of the journal LEF, and slightly later Novyi LEF and its promotion of “factography” all had a profound appeal for Shalamov, who sincerely believed in the aim of raising millions out of illiteracy and out of the poverty he himself had known growing up in Vologda. Inclined to believe in the place of art in that struggle, he spent several years exploring the contending ideas of art as political instrument and the work of art as a sovereign creation.

In 1925, the year Shalamov arrived in Moscow, the critic Viktor Shklovsky published his Theory of Prose, and in the years that followed Shalamov eagerly read the publications of OPOYAZ, the Society for the Study of Poetic Language, a group that in addition to Shklovsky included the critics Boris Eikhenbaum and Yuri Tynyanov. Although Shalamov didn’t develop into an exemplar of the formalist program, it is hard not to see an affinity between the stony reality of the Kolyma stories and the kind of prose Shklovsky argued for in his Theory: “And so, in order to return sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art. The purpose of art, then, is to lead us to a knowledge of a thing through the organ of sight instead of recognition.” It was also Shklovsky who gave, in Knight’s Move (1923), a brutal description of hunger in civil war–era Petersburg that is already more than halfway to the long drawn-out starvation in the gulag that sounds the ground tone of Kolyma in Shalamov’s stories.

In 1958, drawing from his own experience of near starvation and his passage (a year earlier) through the same transit camp near Vladivostok where Osip Mandelstam died, Shalamov wrote the story “Cherry Brandy” about the poet’s last days hovering between life and death, a narrative of the end of a life permeated and animated by a poetic consciousness (reminiscent in some ways of Hermann Broch’s magisterial novel The Death of Virgil, but condensed into six pages). The later story “The Resurrection of the Larch” enacts an oblique resurrection in the form of a larch branch sent from Kolyma to the poet’s widow. Aided by the woman’s “passionate will,” the branch miraculously returns to life standing in an empty food can with dirty Moscow tap water, growing fresh green needles and exuding the vague odor of turpentine, which is “the voice of the dead.” Only a living culture can remember and mourn. In bringing the branch back to life, both sender and recipient resurrect for a moment “a memory of the millions who were killed and tortured to death, who are laid in common graves to the north of Magadan.”

The story invokes the great age of the Dahurian larch, which is still maturing at two hundred years and achieves maturity at three hundred. The gulag alters not only the measures of human life—emotion, ethical choice, and spirit—but also the scale of historical time. The natural world, on the other hand, even in the hostile climate of Kolyma, can sometimes be enlisted as an ally of art against the prisoner’s extremes of deprivation and erasure. The larch can be called as a witness not only to the fate of a prisoner in the Far North under Stalin but also to the journey Shalamov invokes of the eighteenth-century writer Natalia Sheremeteva-Dolgorukova, who as a young wife followed her husband into exile in Siberia, where he perished: “[The larch] can see and shout out that nothing has changed in Russia, neither men’s fates, nor human spite, nor indifference.”

In the story “Graphite,” the marks (“tags”) made by topographers on notches cut in trees connect the twentieth-century dwellers in Kolyma with the vast time span of the geological earth. The author follows this observation with the unsentimental comment that dead prisoners go into the earth each with a tag of their own tied to one toe and marked with graphite—a product of millennia of compressed organic matter. In “The Resurrection of the Larch” and “Graphite” Shalamov reminds the reader that the bodies of the dead do not decay in the Arctic permafrost: they endure in an icy immortality that is a terrible inversion of heroic glory and also a powerful metaphor for the Soviet inability to mourn the victims of Stalin. (By the same token, the current signs of thaw in the Arctic permafrost as a result of climate change may bring the dead back to press their claims on a world that denied them.)

Nothing has changed: yet elsewhere, Shalamov insists on contrasting the conditions of earlier prisoners with those he himself experienced in Kolyma. In the story “Grishka Logun’s Thermometer,” he marks the distance between the prisoner-narrator and the prisoner Dostoyevsky by pointing to the novelist’s many “miserable, tearful, humiliating but touching letters to his seniors for all of the ten years he spent as a soldier after the ‘House of the Dead,’ ” even his “poems to the empress.” The narrator writes a petition on behalf of his immediate boss, Zuyev, a mining inspector and former prisoner, who is trying to get his conviction annulled by the authorities. The narrator agrees to the job in order to spend a day indoors, out of the lethal cold, but he fails to produce a letter of sufficient rhetorical power because he is so depleted and damaged that “the repository where I used to keep grandiose adjectives now had nothing in it except hatred … There was no Kolyma in the ‘House of the Dead.’ If there had been, Dostoyevsky would have been struck dumb.”

To Shalamov, Dostoyevsky is a genius and an example of artistic integrity, but he is also to be judged severely for his failure to reveal the true depths of depravity in penal-camp life. In “What Fiction Writers Get Wrong,” an argument against nineteenth-century literary romanticization of criminals, Shalamov claims that Dostoyevsky mistook the accidental criminals he came across during his imprisonment for gangsters, for the professional class of criminals who live by their own brutal code of law and have dominated camp life for generations. Shalamov is willing to allow for the possibility that “Dostoyevsky never knew them,” because “if he did see and know them, then, as an artist, he turned his back on them.” Tolstoy and Chekhov also failed in this regard, in Shalamov’s view, although he felt Chekhov had undoubtedly come across real criminals on his journey to the prison island of Sakhalin; in “Crooks by Blood” he is pleased to be able to correct Chekhov on a fragment of gangster cardplayers’ slang misheard on Sakhalin.

Shalamov considered swashbuckling portrayals of criminal outlaws by twentieth-century writers like Babel to be frivolous. In the letter to Sirotinskaya quoted earlier, his censure also falls on Babel’s prose style (to many a model of concision): “If I practically never thought about how to write a novel, I thought about how to write a short story from early on and for decades … I once took a pencil and crossed out of Babel’s stories all their beauty, all those fires like resurrections, and looked at what was left. Of Babel not much was left, and of Larissa Reissner, nothing at all.” As for poets, Sergei Yesenin, despite his great lyrical gifts, was fatally compromised in Shalamov’s eyes by sucking up to the criminal world and by the fact that criminals had adopted him as their bard, tattooing lines from his poems on their bodies. “The gangster … is not wholly without aesthetic needs, however little he may be human. His needs are satisfied by prison songs … usually very sentimental, plaintive, and touching” (this from “Apollo among the Criminals”). Yesenin caters to that taste.

Written in the late fifties, the stories in the fourth volume of his Kolyma tales, “Sketches of the Criminal World,” are a merciless indictment of this corrosive, brutal criminal subculture but also of the ideological delusions Shalamov saw at work in popular attitudes toward it. Soviet propaganda put forward a model of punitive labor as moral transformation: Shalamov more than once refers contemptuously to the primary ideologue of labor in education, Anton Makarenko, whose thirties hit novel The Pedagogical Poem was made into a popular Soviet film in 1955. Shalamov writes of the “fashion for ‘reforging’ ” by labor as a paltry smoke screen for extreme exploitation, which allowed criminals to manipulate themselves into positions of power in the gulag. Another connoisseur of Soviet prisons, the Polish poet Aleksander Wat, recalls in My Century his own bewildering contact during his wartime odyssey with the “immense pararepublic of criminals … a dense network covering Stalin’s tsardom” and remarks on the close sympathy between the gangs of juvenile delinquents he observed in prison camps and the NKVD officers overseeing them, many of whom he rightly assumed had emerged from gangs in the first place. Traditions of criminal organization predating the revolution (and manifest in slang that Shalamov knew well) were themselves preserved and absorbed into the culture of the new Soviet state—institutionalized, just when the prerevolutionary traditions of the Russian intelligentsia were being systematically destroyed. His stories show better than anything written about the gulag how these processes were parallel and inseparable.

It should be said that features of the gulag endure in the current Russian prison system. In an important 2017 book titled Imperiya FSIN (FSIN is an acronym for the Federal Service for the Implementation of Punishments), the Russian human rights advocate and researcher Nikolai Shchur writes that blatnye (gangsters, though not necessarily direct descendants from gulag gangsters) still hold a great deal of power over political prisoners and, with the collusion and often encouragement of the authorities, are able to exert influence on important aspects of prison life, like the number of visits or packages a political prisoner is allowed to receive in a given period. Although during the period of Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency tentative moves (most likely motivated by a transient wish to improve Russia’s international image) were made to de-gulagize the Russian penal system, with Vladimir Putin’s return to the highest office in 2012 all such reforming gestures were abandoned. The system retains the main features of the gulag: pretrial facilities in metropolitan areas and “correctional colonies” mostly in remote locations, with terrifying transports that are an integral part of the punishment. Judith Pallot’s work based on interviews with women prisoners in Russia also throws up grim parallels with Shalamov’s stories.

Shalamov is rare as a writer on camp life because he refuses to provide any variety of redemptive narrative, whether by portraying death in the gulag as martyrdom or by finding heroism in survival or in acts of witness. Survivors have no aura of courage or strength, just qualities of luck or cunning that do not reflect particularly well on their character. Nor does Shalamov participate in the process by which the state, having lost the ability to justify its killing by keeping its victims within a zone of exception, chooses to portray them as tragic sacrifices of a cruel but rational strategy.

In order to resist the inscription of meaning on what is to him, strictly speaking, meaningless suffering, Shalamov employs radical ambiguity and inconsistency. The same stories are given in slightly differing versions; an incident is rendered in such a way as to have contrary meanings. In the story “Brave Eyes,” a geologist’s senseless shooting of a weasel, spilling unborn cubs from its belly, is a whimsical, wasteful killing that echoes how people die in the gulag; on the other hand, the geological excursion is an escape into a wilderness where the dying animal’s eyes have a proud dignity that moves the broken-spirited prisoners. In “The Nameless Cat,” a gulag driver who “wasn’t a spiteful man” breaks a cat’s spine and ribs with an industrial drill bit. It crawls to shelter and, adopted for a time by a paramedic in the psychiatric department of the camp hospital, somehow gives birth to a litter of kittens, one of which survives and works alongside a prisoner attempting to supplement his starvation diet with freshly caught fish from a stream near the camp. After a time it just as unaccountably disappears. Has it been caught and cooked by thieves, like its mother and her other kittens, or has it found a freedom superior to the cowed and humiliated life of men? The question, and its pendant, as to whether this or any life is worth living, is left like an unresolved chord, a snatch of subversive “formalism.” Animals are the repositories of virtues—courage, strength, care—that have fled from human lives.

Alert to the aura of martyrdom that attached itself to the hosts of gulag victims, Shalamov refuses to sanctify them. He repeatedly declared himself an atheist, though the Orthodox Christian culture of his father shaped his imagination in unmistakable ways. Christian symbols, when he discovers them, are irrevocably altered like parts of the human body after exposure to frostbite, to employ one of his central metaphors. They are unhealing wounds rather than trophies. In the story “Graphite,” the larch’s “wounded body is like a newly revealed icon, the Chukotka Mother of God, if you like, or the Virgin Mary of Kolyma, expecting a miracle and declaring a miracle.” In “The Path,” the mere sign of the intrusion of another, anonymous person is enough to curtail the brief spiritual freedom that allows the narrator to compose poems in his head, and the path itself proves resistant to his attempts to turn it into poetry.

Shalamov himself left a body of poetry that, as Donald Rayfield has said, belongs to an earlier century than his prose. Jorge Luis Borges and Ivan Bunin are other examples of twentieth-century authors of innovative prose whose poems for the greater part read like imitations of their fin de siècle predecessors. Shalamov’s stylistic ideals are “early Pasternak and late Pushkin,” and it is Pushkin above all who in his eyes provides a moral and aesthetic antidote to the nineteenth century: to its sentimentality, its distended forms and messianic delusions. Shalamov’s critical essays on poets show him to be an acutely sensitive reader and rigorous analyst of the poetic form, notably patterns of sound repetition and intonation. Svetlana Boym wrote incisively about Shalamov’s use of intonation in prose to counteract the wooden speech, the novoyaz or newspeak of his era. His own poems are well built, honest, and relentless, but it is in his prose that Shalamov’s ear is most exquisitely employed in catching living speech rhythms, desolate cadences of event and emotion in which the pitch patterns of the speaker’s voice, moving against the warp of novoyaz, expose the false harmony imposed in the camp universe.

In 2007, on the centenary of Shalamov’s birth, an exhibition devoted to his life and work took place at the Memorial Society in Moscow. During a discussion organized as part of the commemoration, the critic Ilya Kukulin spoke of the distance between Shalamov’s prose and poetry in terms of the author’s discovery in prose that the formal harmony and order he sought in his poems existed in the world of the gulag only in a malignant form; in Mandelstam’s words, “In the undergrowth a serpent breathes / The golden measure of the age.” In the last of Shalamov’s Kolyma stories, “Riva-Rocci,” we read that “even third-class camps need flowers and symmetry.” Where poetry appears as a natural, even vital human impulse, as in the story “Athenian Nights,” it is interrupted by the incursion of a vindictive superior. This story begins with a curious presentation of what Shalamov cites as “man’s four basic feelings,” listed in Thomas More’s Utopia, “that, when satisfied, provide the highest form of bliss”: eating, sex, urinating, and defecating. It is these urges men are prevented from satisfying properly in the camp. To this list Shalamov adds poetry, also a physical need that manifests itself as soon as the immediate threat of death recedes slightly.

In fact More does not sum up human needs in quite this way; in a chapter titled “Of the Travelling of the Utopians” we are told that they “divide the pleasures of the body into two sorts—the one is that which gives our senses some real delight, and is performed either by recruiting Nature and supplying those parts which feed the internal heat of life by eating and drinking, or when Nature is eased of any surcharge that oppresses it, when we are relieved from sudden pain, or that which arises from satisfying the appetite which Nature has wisely given to lead us to the propagation of the species.” Significantly, More also includes in the top Utopian pleasures the enjoyment of music, which “strikes the mind with generous impressions.” But Shalamov’s argument for poetry is different: it is as vital to prisoners as food, so that even if gathering for recitations in the bandaging room of the camp hospital exposes them to the danger of discovery and punishment, they continue to meet until they are prevented by the imposter “Dr. Doctor.” They recite Pushkin, Mandelstam, and Akhmatova to one another not because they are sublimating or rising above their physical needs but because poetry can aid the return of “goners” to the world of the living.

Shalamov’s Kolyma stories are an astonishing achievement in a tradition of high art that surprises by surviving and describing the very conditions created to destroy it. In Shalamov’s own account, when he wrote he paced and raged in his room, weeping and shouting, saying every story aloud. Most of his best stories, he told Sirotinskaya, “were written in one go, or rather, copied from a draft only once.” They were intentionally left unpolished, in a conventional sense unfinished, meant to retain the rough edges that proved they had been torn whole from real experience. How Shalamov found the strength to carry out this arduous labor after almost two decades of crippling prison life and exile, in impoverished isolation and recurrent physical and mental pain, with no hope of recognition or publication, without the slightest compromise with a timid post-Stalinist literary establishment and without allowing himself to be used as a pawn in the Cold War, is one of the miracles of modern literature.

Alissa Valles is the author of the poetry books Orphan Fire (2008) and Anastylosis (2014) and the editor and cotranslator of Zbigniew Herbert’s Collected Poems and Collected Prose.

From Sketches of the Criminal World: Further Kolyma Stories , by Varlam Shalamov, translated from the Russian by Donald Rayfield, published by New York Review Books. Introduction copyright © 2020 by Alissa Valles.

Errant Daughters: A Conversation between Saidiya Hartman and Hazel Carby

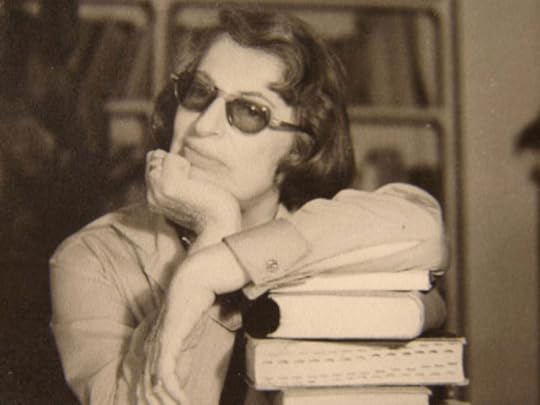

Left: Hazel Carby. Right: Saidiya Hartman.

On a rainy winter morning, Hazel Carby arrived at my office in Columbia University’s Philosophy Hall to discuss her new book, Imperial Intimacies , which is a history of empire, slavery, colonialism, and migration written in the form of a memoir. This eloquent and moving account of the entanglements of empire is narrated from the perspective of a young black girl of Welsh and Jamaican descent trying to survive in postwar Britain, a world that would prefer for her not to exist at all and that never for a moment fails to see her as an outsider, an eternal alien. “Where are you from?” is the question that each day challenges her right to belong, that routinely marks her as a foreigner in the country where she was born. The narrative advances on dual tracks and the story oscillates between “the girl” and the “I” of the adult narrator, a scholar and researcher, in search of the pieces of her past and reckoning with what it means to be black and British.

Imperial Intimacies sets out to challenge “the binary thinking that opposed colonial center and colonized margin” and the conviction that British identity is predicated on the non-belonging of black and brown people, whether citizens, migrants, or refugees. The book does so by traversing the “geographies of pain” that emerge in the wake of empire; connecting the rural hamlets of Wales and Jamaica; linking the factory, workhouse, and plantation; following the dense web of connections between the lives of peasants and workers, soldiers and the enslaved; and tracing “the perverse lines of descent” created by racial slavery.

The movement of conscripts and migrants and young working women and errant daughters reveal the forms of violence and domination, exploitation and precariousness that connect the imperial metropole to the colony. Imperial Intimacies is an assemblage comprised of the recollections of a precocious and lonely young girl in postwar Britain and the arduous research of a scholar “pitting memory, history and poetics against each other” to produce a story comfortable with the unresolvable contradictions and mysteries of the past.

Stories shared in the kitchen and recollected from the sick bed compete with the archive regarding the truth of what happened when. The scholar’s research discloses the rifts and failures that no one can bear to admit—a stint in the work house and the lines of kinship ruptured by the categories of human and slave, master and object of property, free black and chattel. Imperial Intimacies explores and intensifies the conflict between familial stories, national histories, imperial accounts, and archival documents. Carby writes across these registers to trouble and unsettle national and imperial projects. Hers is an account of Britain articulated in the relation between two islands and in the explication of personal and public inventories, which range from the political arithmetic of imperial governance and the double-entry bookkeeping of the slave ledger to the brutal and terrifying acts staged in a kitchen—a mother’s lessons in duty and sacrifice and a suicidal father lying unconscious on the linoleum floor. At every turn, Carby refuses to tell a tidy or convenient story and instead produces an account of empire that is as expansive as it is heartbreaking.

INTERVIEWER

In the acknowledgments to Imperial Intimacies, you mention that the book began in conversation with Stuart Hall, when you were students at the Birmingham Centre for Cultural Studies. How did that provide the groundwork for the book?

CARBY

I remember very, very clearly that Stuart and I used to sneak into the side room where they kept the television, and we would watch cricket in there while everyone else was busy. Of course we were watching the West Indies play England. We would have these conversations about the Caribbean, and he would ask me about my father. I realized it was amazing what I actually didn’t know, to be quite honest. We talked about what our Caribbean parents didn’t tell us. So I think the idea of speaking into that silence actually began in those conversations.

INTERVIEWER

Were the silences as great as you imagined?

CARBY

Oh, absolutely. I had to think, more critically about the silences in general throughout my childhood, one of which was about the racism that my brother and I faced. My parents found it very difficult to talk about that. They both told us, if you’re just the best in your class, if you’re just first and the best at everything, they’ll leave you alone. But of course, being left alone also meant being lonely.

One of the pieces that I wrote at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, in the race and politics group, was on racism in education. When I started to publish pieces, my father started to read them. And at one point when I was at home visiting for the weekend, he started to talk about it and actually broke down. It was the first time we ever really had a conversation about all the complicated reasons he’d stayed in the UK after the war. He cried, because it was the first time he was expressing any doubt to me. And he asked me, very frankly, Do you think I was wrong to stay? He said that he and my mom thought that the education system would be better in Britain. So for me to be writing a piece about the structural racism of the education system—that really took him aback.

At that point, we started to have the conversations that we’d never had before, and it opened what turned out to be a flood of stories over many years. When I think back to that moment, I think it opened a door for us to be partners in a project of thinking about Britain in a way we never had before, not just as father and daughter but as a critical exchange.

INTERVIEWER

One of the things I love about the book is the way you reveal the intimate and psychic landscape of structural racism and colonial violence. The forces and logics that define and determine the social relations of empire are explicated, but in a manner that conveys their emotional weight and power. We are forced to contend with the intimate dimensions of social and historical violence.

For me, it brought to mind all the young people who were a part of the school desegregation movement in the American South. Elizabeth Eckford was never the same after being assaulted by a mob of white adults when she tried to enter Little Rock Central High School. Other children burnt their schoolbooks and experienced severe depression and had breakdowns after the intensity of navigating such hate and hostility. Those narratives trouble the one-dimensional portrait of these young people as solely heroic or triumphant. They paid a great psychic cost for trying to desegregate their schools. As a child, you, too, paid a great cost in the racist landscape of postwar Britain. Imperial Intimacies deftly illuminates the way we inhabit these systems, and how they harm and shape us, how they disfigure the contours of intimate life.

CARBY

Well, for us as children, the Windrush moment—the arrival in 1948 of the ship bearing migrants from Jamaica, popularly understood as a turning point for British culture—was actually a burden to bear, it was nothing to celebrate. This is something that Stuart Hall said a very long time ago. It was as if, in Britain, concerns about race and racism were actually carried by those people who arrived in Britain in the postwar period. Historical erasure was very important to that whole postwar story of black British history. For example, I was told in school that I was a liar for saying that my father was in the RAF, because “there were no black people serving in the military, leave alone the RAF, the creme-de-la-creme of the of the British fighting force.” So I knew that my stories and the school’s stories were not just opposed to each other—my stories were dangerous. So you learnt to be silent, you just learnt to silence yourself.

I found the process of actually writing the book to be an excavation of sorts. I found myself thinking of terms like “archaeologist.” I had the feeling of moving through layers, not just of history, but the layers of being and becoming in the world that have accrued to us over time and that need to be peeled away level by level.

INTERVIEWER

There are a thousand questions I want to ask you related to what you’ve just said! But can you talk a bit about the title Imperial Intimacies? It suggests this entanglement or conflict between familial stories, national histories, imperial accounts, and archival documents, yet you write across all of these registers to trouble and unsettle national and imperial projects—and, as important, you refuse to tell a tidy cohesive story.

I’d love to hear you talk about building your spider’s web, as you call it, to create the links between all these stories. And then please talk about the multiple modes of the writing you use to break open these archives and documents—memoir, history, auto-theory, narrative, and poetics.

CARBY

I’ll start with the image, the Anansi spider’s web that I talk about at the very beginning of the book. First, a web has to be constantly maintained, the spider is constantly running around to different parts of it, mending pieces that are broken. If you actually watch them, they’re very canny about what they’re going to leave unmended when they turn away to strengthen a different part. I felt a lot like that when I was working on this book, there were threads I just had to leave broken sometimes. But also, you know when something lands on a spider’s web and there’s a resonance around the spot so the spider knows where to go? When I found different memories in the colonial archive, they acted similarly, and made me move in a direction I didn’t think I was going to go in. So there was always this tension and this constant movement. You had to move between one part of the story to elucidate another part of the story.

I originally imagined that the book would be called “Child of Empire.” But I moved away from that title, because I wasn’t actually at the center of the book. Books had been published like Niall Ferguson’s Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, in which he uncritically positioned himself as a child at the center of empire. I remember he wrote this extraordinary passage about being raised in Kenya which he remembered as “a magical time” filled with the singing of the Kikuyu women. There was such a sense of entitlement of the British subject in Ferguson’s account that I realized I didn’t want to make the same mistake of writing a story in which my right to belong, my right as a national citizen was assumed. Because that was not my story.

I wanted to show how my claim to belonging was denied, and was met with very volatile, violent responses. I wanted to write against being a child of empire. If we are going to tell stories that involve us, we have to realize that there are all these conventional modes of writing that aren’t sufficient, that cannot possibly encompass the multiplicity of the tales that we want to tell. I also wanted to write within a framework that could create a sense of how different parts of the empire were intimately tied to each other, intimately dependent on each other. And that it didn’t matter where in Britain you started to excavate the relationship with colonialism and imperialism, it’s a story that involves ordinary people, everyday places, extremely small hamlets.

The deeper I went into this project, the more I realized that I had to talk about how ordinary people became educated into understanding themselves not just as white, but as imperial subjects with the right to govern other people. This gave them some investment in being British that made them superior to other people, even if they themselves were poor. I found that sense of privilege in my maternal family, even though they came from very, very poor circumstances.

INTERVIEWER

The book attends to these entanglements and investments with such nuance and complexity. For example, when you talk about your childhood summers in South Wales, you are able to convey the sense that you and your brother are deeply loved by your mother’s family, and, at the same time, you are being instructed in a model of imperial subjectivity that is explicitly marked as white. You capture the contradictory textures of love and kinship.

The book addresses the ways in which the white working class is conscripted to the project of empire, but it does more than this. You don’t avoid the difficult questions, such as what does it mean that these people who love you so much were also deeply invested in colonialism? That even in this beautiful place, you cannot avoid the painful lessons directed at you as the errant daughter, the black daughter?

CARBY

I had to think not just back to those conversations with Stuart, about what our Caribbean parents didn’t tell us, but their counterpart on my maternal side—what I was being told. So, yes, there were all these cousins who loved us but were also trying to wash the brown off our skin because they thought we weren’t bathing properly. We would hear them talk about the black children in Cardiff as pickaninnies, without any sense that my brother and I were pickaninnies, too, but you know—their pickaninnies, so beloved. I should say that we were sent there in the summers, because my parents were working two jobs at night. And they were doing that because they pulled us out of the public school and put us in private schools. And I think actually, that was their way of trying to manage the racism that we were facing.

So we would spend our summers down in Wales with this family who taught us to be strivers. They would recount stories that were pedagogical, they were to teach us how we were supposed to succeed and what we were supposed to aim for. They were supposed to teach us how to behave if we wanted to have good jobs. And by good jobs, they really meant becoming teachers and nurses, maybe even a bank manager. But it was in the context of their own history, of how they had gone from blue collar to white collar work because of working for the Great Western Railway.

It wasn’t until I actually did this project and was in the archives and looked up the history of the Great Western Railway that I found the company handbooks on behavior. They were word for word, exactly, how we used to be instructed to get a job, and stay with it, and mark incremental promotions and rewards of recognition. This made me consider how a particular form of Britishness has to do with the historic moments through which people move, but also what they repress. In the adoption of this work discipline from the nineteenth century, my family had repressed the histories of where they actually came from. So the stories they were telling me were passing over all the stories of extreme poverty and disease.

I wanted to write under this title of “intimacy,” how, in fact, the empire had colonies that appeared to be marginal to the metropole of course, but that within Britain itself there were areas that were marginal. Marginal agricultural areas, marginal extremes of poverty. For example, the city of Bristol was very important to my family, even though they existed in an extremely poor section of Bristol. But my grandmother was moving about a city that had some of the first-ever girls’ schools, a university, a civic culture, a theater, libraries that she could use. Her beliefs were shaped by that civic culture, poor as she was. My great-great-grandmother Rebecca grew up in the city of Bath—she was a laundress. At the end of her day working in a commercial laundry, she moved from the wealthy part of the city to the most impoverished part of the city.

So I realized that there was a geographic, or geopolitical, framework to reveal in the book. It couldn’t only be explained by class—I had to take account of how empire creates these centers and peripheries, both in Britain and in the colonies. I wanted to talk about how cities themselves were divided by empire. There were people in Bath who were very, very rich, whose wealth had come from enslavement, supported by people like my great-great-grandmother Rebecca, who was servicing them. I wanted to think about the relationship between that sort of maintenance alongside the maintenance that people were providing from the colonies. The work of the book was being able to reveal those intimate relations, those connections, while attending to the specificity of the differences. Empire and imperialism work in ways that are not obvious on the surface. And that’s why I said at the beginning, it’s a story of ordinary people.

INTERVIEWER

I want to focus on you and the issues of belonging and identity. I’m thinking about two short chapters in the first section of the book, “Where are you from?” and “Lost.” These chapters convey the violence and torment that accompany being a black child of empire in postwar Britain. These chapters are not narrated from the perspective of an “I” but from the view of “the girl.” These distinct narrative perspectives are related to issues of withholding and disclosing stories and with disassociation and traumatic memory. Where does pain lodge and who is responsible for narrating it? Can you say more about these different narrative voices?

CARBY

This is really where you come in, Saidiya! We’ve exchanged writing and ideas for so many years. From the very beginning, I wanted to write for an audience that wasn’t just an academic audience, I wanted to write about ordinary people, and I wanted ordinary people to read the book. And I knew that I wanted to take all my training as a feminist theorist and scholar of race, and to take all the power and insights of my career, but to translate it into a different kind of project. Well, it was easier said than done, I think! I found that I could easily think and analyze and critique these stories, but I was still writing in a way where I was denying my own experience, and what it all meant to me.

There was one moment when I was writing about something I discovered in the in the National Archives and you said to me, “Why don’t you dwell on that moment, the moment when you actually found that? Put yourself there, what were you thinking?” Oh, I knew what I was thinking! But I hadn’t written about any of that. So when you said to me, “dwell,” you were also asking me to think about my own investment. You were asking me to think about how I was shaped by the history and by the act of finding out what I was finding out, by hearing stories I wasn’t meant to hear. It opened the floodgates, in some ways. So I decided to begin the book there, with what I call “the question.”

INTERVIEWER

“Where are you from?”

CARBY

Yes, how I was asked this question, which became a constant part of daily life, a question that asked you to account for yourself. Posing the question was a denial that I could belong to Britain. I realized that the book was a whole response to that question, Where are you from?

I had to confront how difficult that was to handle as a child, how much of that I had buried, just like my father had buried things. I wanted to think very seriously about what had happened to that child, who I had been and had left behind. However painful that child’s growing up was, it hadn’t totally shaped the adult I became. So I felt that one way I really could deal with this in terms of narrative was to treat the child—“the girl”—as a character. She’s a character that develops in a particular moment in history, and she was shaped by that history, and she resisted that history. It was important that I find a way to acknowledge that who the girl had been, how she was shaped, didn’t determine everything “the writer,”—that is, my adult self—had become.

Relatedly, I think it’s really important to think of the way in which we are multiple selves, and I wanted to reflect this in the book. And I found this even in doing the research. Sometimes the professor, or the researcher, wanted to dive gung-ho into archives, but it was actually very painful for the girl or the writer to discover and to think about these things. I wanted a way to talk about all these selves coexisting, and I wanted to reveal the tension in these moments. Because there’s a cost.

So in the in the act of writing, there were selves who became characters, who had lives and whose potential could have gone in multiple directions. And I was just following some of the threads.

INTERVIEWER

I don’t know if it actually lessens the pain of the account or intensifies it. As a reader, you feel that the narrator needs the “I” and “the girl” to hold the weight of this history, the burden is enormous. The doubling is also dramatic—it makes apparent the multiplicity of selves who inhabit the narrative. As a strategy, it also complicates the matter of time. Imperial Intimacies doesn’t have a straightforward narrative or a teleological arc—as a reader, you feel that time itself is entangled or sedimented or broken. Even when the “I” is narrating, the “girl” is there, too.

CARBY

I think broken time is often that which is left unresolved. And I don’t try to resolve that in any narrative sense. I actually think it’s important to leave that broken, frankly.

INTERVIEWER

Over the course of your intellectual trajectory from Reconstructing Womanhood to Imperial Intimacies, there is a sustained and ongoing engagement with black women writers. In Imperial Intimacies, you trouble the framing of black woman’s writing as a maternal inheritance and disenchant the domestic space. As a scholar, you have produced a genealogy that determines how we read and understand that tradition. But as a writer and a memoirist, it is as if you enter that tradition through the back door. You enter it as an errant black daughter, and, in fact, the text opens with Jamaica Kincaid, another errant black daughter. Can you talk about what it means to be deeply informed by this tradition of black women’s writing and to transgress?

On a personal note, one of the things that I loved about having you as a teacher and a mentor was that there was never the expectation that I be dutiful. It was so pronounced, and it was so rare. After reading Imperial Intimacies, I thought, Of course you would never expect me to be a dutiful daughter! You spent your whole life refusing that imposition.

CARBY

Errancy is a really interesting concept. I felt errant from the moment I arrived here. And I claim it. It’s not that I don’t feel totally accepted now. It’s just that I cleave to feeling unsettled. I think it’s one of the things that’s very important to feel. I feel unsettled with the nationalism of African American studies, so I’m constantly trying to make it more worldly, more global, to encourage my students to think much more critically and unsettle some of the assumptions that they’re receiving. So errancy is the way I live and the way I think.

I remember walking into the African American studies department at Yale, and Professor Henry Louis Gates saying, “What’s a nice white girl like you doing teaching African American studies?” or “Why are you interested?” It was another dimension of the question “Where are you from?” This experience of racially marking and unmarking bodies is something that I also tried to bring into my teaching, to actually get people to think critically about how blackness is inhabited.

Relatedly, my father could never understand why I, as a student, joined the African Student Association. It was a moment when he said to me, Why would you join an organization for African students? Because Africans were slaves. When I thought back to that, I realized how across the Caribbean, that history of enslavement was hidden because of shame. There was deep, deep, deep shame. So a history had been erased, not just in the metropole, but in the islands themselves, and it has only fairly recently been excavated and memorialized.

But the other erasure was about the role of enslaved women. I had to reconsider the stories I was told about the history. As my aunt used to say, “There were planters in our family.” Well, that didn’t mean what I thought it meant at the time! My mother, my father, and my aunt used to talk about, a “housekeeper” and a planter. And I realized only in the archives who that was, this free black woman, Mary Ivey, but there was no acknowledgement of how women like her were implicated in enslavement’s sexual economy of violence and rape and sexual exploitation. It was as if language itself was being cleansed of history. Just a planter and a housekeeper. No relationship, no language of enslavement, of brutality, of force, of sexual abuse.

INTERVIEWER

That’s so resonant for me, because for my father’s family there was never a peep about slavery. And Curaçao was an island at the center of the slave trade, yet there’s no memory of it! Zora Neale Hurston joked about how in the West Indies, we all come from roosters. Only the men are named because of their status, because they’re white. As a result, the black maternal line is erased.

Can you talk about this in relation to writing? Writing isn’t a process, as you say in the book, that will provide closure or a tidy working through of this history. You talk about writing as a method for being able to perceive complexity. At other times, you speak of writing as betrayal, as a refusal to obey the injunction of silence.

CARBY

Very much so. When my mother discovered she had Parkinson’s disease, I was constantly going to the UK. I felt as if I actually lived in a plane in the middle of the Atlantic. But to her, I wasn’t there, I was in the United States. At one point, she demanded that I give up my job, and move away from my husband and my son, and care for her. Because if I was a real devoted daughter, that’s exactly what I would do. And I didn’t need her, she said, to tell me that. I should just have done it. My brother in the UK daughtered in my place, along with an army of care workers, but it was not good enough for her. I explore the various torments my mother had in her life, both internal and external, but the image I have of what I was doing was analogous to capturing a butterfly with words, pinning it through the thorax as in a museum display, because once you’ve written it, those words fix people in place.

My mother would have been absolutely horrified and, I think, deeply hurt to read them. But I didn’t know any other way to explore the difficulties of what daughtering and mothering meant.

This is exactly what the writer has to try and expose. I don’t try to resolve everything in the book. I do try to expose the unresolvable. I don’t know if as women, as daughters, we know how to resolve all of those different pressures. I am indeed an errant daughter, in multiple ways.

Saidiya Hartman is the author of Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval .

January 20, 2020

August Wilson on the Legacy of Martin Luther King

On this archival recording, playwright August Wilson celebrates the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. with a reading at the 92nd Street Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center on January 21, 1991. Wilson reads poems and selections from the plays Fences and Two Trains Running (which had yet to be produced), and participates in an extended audience Q&A. Before reading from Fences, set in Pittsburgh in the fifties, he reads the play’s introduction:

Near the turn of the century, the destitute of Europe sprang on the city with tenacious claws and an honest and solid dream. The city devoured them. They swelled its belly until it burst into a thousand furnaces and sewing machines, a thousand butcher shops and bakers’ ovens, a thousand churches and hospitals and funeral parlors and moneylenders. The city grew. It nourished itself and offered each man a partnership limited only by his talent, his guile and his willingness and capacity for hard work. For the immigrants of Europe, a dream dared and won true.

The descendants of African slaves were offered no such welcome or participation. They came from places called the Carolinas and the Virginias, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee. They came strong, eager, searching. The city rejected them and they fled and settled along the riverbanks and under bridges in shallow, ramshackle houses made of sticks and tar paper. They collected rags and wood. They sold the use of their muscles and their bodies. They cleaned houses and washed clothes, they shined shoes, and in quiet desperation and vengeful pride, they stole, and lived in pursuit of their own dream. That they could breathe free, finally, and stand to meet life with the force of dignity and whatever eloquence the heart could call upon.

By 1957, the hard-won victories of the European immigrants had solidified the industrial might of America. War had been confronted and won with new energies that used loyalty and patriotism as its fuel. Life was rich, full and flourishing. The Milwaukee Braves won the World Series, and the hot winds of change that would make the sixties a turbulent, racing, dangerous and provocative decade had not yet begun to blow full.

Listen to the full recording from the event below:

January 17, 2020

Staff Picks: Diamonds, Dionysus, and Drowning

Silvina Ocampo. Photo: Adolfo Bioy Casares. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I love a good hundred-page novel. Too many books go for quantity over quality, choosing to bloat their page counts with unnecessary plot twists—and don’t even get me started on that silly term novella. Not so for Silvina Ocampo’s The Promise, recently translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell. Ocampo—an aristocratic Argentine who was friendly with Borges and whose elder sister Victoria was the founder of the prestigious literary journal Sur—purportedly took twenty-five years to finish The Promise, and every sentence glints with precision. The plot is minimal at best: While traveling from Buenos Aires to Cape Town to visit family, the narrator falls ill. On the way back to Argentina, she falls off the side of the ship and spends the rest of the book swimming—and presumably, eventually drowning—as she recalls various persons and experiences from her life back home. A few characters reoccur: Leandro, an untrustworthy doctor; Irene, his lover; and Gabriela, also known as Gabriel, Irene’s daughter. Entire paragraphs repeat themselves with small variations, and water seeps in again and again. The confusion is part of the appeal—what you’re after are the sentences, which have the feel of epigrams: “I envy people who cry; they show off their tears like necklaces,” goes one. “Women love with their eyes closed, men with their eyes open,” goes another. I think I took a photo of nearly every other page so as not to forget them. The twenty-five years of work were worth it. —Rhian Sasseen

I’ve been knocked out by the new titles from Seagull’s celebrated German List. Georg Trakl’s poems, previously published in individual hardcover editions, are now collected in a single paperback, met with titles from Thomas Bernhard, Ralf Rothmann, Peter Weiss, and others. Of particular interest to me has been a volume of correspondence between Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan (translated by Wieland Hoban). In these letters, Bachmann is needful, especially early on, and Celan less so; the imbalanced exchange is reminiscent of that between Rainer Maria Rilke and Marina Tsvetayeva. With Bachmann-Celan, the correspondence is also one of unequal weight: Bachmann’s letters tend to be lengthy, and Celan’s are shorter or absent altogether, his responses often apologetic for not having written sooner (or not having written at all). And yet we receive a sense of the tumultuous times in which they lived and the development of their thinking and writing. The volume’s editors have included voluminous useful notes and appendixes and a sheaf of correspondence between Celan and Max Frisch, and Bachmann and Celan’s wife, Gisèle Lestrange, the latter tracing the bloom of an unlikely friendship. —Christian Kiefer

David Whyte. Photo: Christopher Michel (CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)).

About a month ago, I unexpectedly tuned into an episode of NPR’s On Being featuring the writer David Whyte. His voice was deep and magnetic; he philosophized in improvised incantations, possessing a natural poeticism in conversation. When asked to read his poems, Whyte had them committed to memory. He intoned each with great force, emphatically repeating the most powerful lines as if unable to get past them. This week, I began reading Whyte’s 2018 collection of poetry, The Bell and the Blackbird, in which his poetic lineage is clear. His verse, exactly like that of W. B. Yeats, exists at the threshold of the subconscious, just beyond the realm of everyday life. There is a deep religiosity to the collection, including a series of blessings that seem meant to be collectively uttered by a congregation. But these prayers center on earthly matters rather than godly. The most earnest among them, “Blessing for Unrequited Love,” offers “A blessing on the eyes that do not see me as I wish. / A blessing to the ears that can never hear the far inward / footfall of my own shy heart … A blessing for the way you will not know me / in years to come.” No matter the Yeatsian symbolism and lyricism, Whyte’s more Minimalist verse inevitably returns to the lived moment. The collection begins with an invitation to journey through

the shadow,

not of death,

but of

the unconquerable

kingdom of life.

Within his lyric medium, human existence is, above all, the primary subject. —Elinor Hitt

Since reading Esquire’s “The Secret Oral History of Bennington” at least a dozen times, I’ve developed a sort of preoccupation with Donna Tartt—how she’s described in the piece, her striking sartorial choices, the nostalgia with which she discusses her college years. So it’s strange that it’s taken me until quite recently to read her enthralling literary debut, The Secret History. The novel opens with a murder among a group of friends at the fictitious Hampden College, which is presumably based on Bennington, where Tartt wrote the book while still a student. The rest of the story explains how exactly this all came to be, tracking the narrator’s start at Hampden, his journey into the classics students’ inner circle, and his discovery of how dark the Dionysian can really be. The plot is both melodramatic and cerebral, Tartt’s prose textured and supple. The way she describes student life feels at once familiar and aspirational (and very eighties)—the best possible version of the campus novel. —Camille Jacobson

I tore through Ágota Kristóf’s extraordinary trilogy in the bleak British midwinter, giddy with jet lag. She is a writer perhaps best read in the dead of night. There is a profound loneliness to her books, an unsettling mix of memory and delusion, all written with the clarity of insomniac thoughts. Even more than Beckett, her prose has a style “without style.” It is blank and precise, even as it voices great horrors. The first of the trilogy, The Notebook, starts with twin boys who act and speak as one; they record their lives with a rigorous commitment to objective truth. “It is forbidden to write, ‘The Little Town is beautiful,’ because the Little Town may be beautiful to us and ugly to someone else,” they note. This method is the first lie; facades continually collapse, and every book undermines its predecessor. This combination of an utterly direct style and the endless misdirection of the narrative unnerves. Behind it all is a truth that can be neither told nor forgotten. As one character notes, “No book, no matter how sad, can be as sad as a life.” I have read few books that engage so profoundly with what it means to write from life, and the fantasy and failure of fiction. Selves fall apart; narratives break into irreconcilable parts. Each immaculate section reshapes the whole and casts a different light: it is like watching a jeweler cut a diamond into dust. —Chris Littlewood

Ágota Kristóf. Photo: Ulif Anderson.

First Snow

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces the moments before her daughter leaves for college. It ran every Friday in November, and returns this winter month, then will return again in the spring and summer.

A silver mixing bowl, that’s what I remember my mother handing me. I was five. My first snow ice cream. For five years, my daughter and I have lived in this Texas town. For five years, no snow. But this morning, snow rushed down as my daughter slept. I snuck outside and cupped enough from the hood of her car. Milk, vanilla, sugar, and a pinch of salt. My mother’s bowl.

This is not missing. This is us, living.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

January 16, 2020

Inner Climate Change

Joseph Farquharson, The Shortening Winter’s Day Is Near a Close, ca. 1903. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

After living alone for nearly two years in a house in the northern Vermont woods, I returned to the city alert in all the wrong ways. The timpani of the symphony playing in a Chinese restaurant struck me as a herd of deer soon to bound through the wall. At first glance, every street light seemed a full moon. I’d gone through a kind of inner climate change: my attention had dilated to take in the subtleties of the woods and weather; my memory had sharpened to navigate miles of drifted snow. Reacclimating to the city would have been challenge enough, but there was an extra challenge. It was the early aughts, screens were suddenly everywhere, and everyone else was going through inner climate change, too.

On my daily snowshoe treks through the trees, I’d begun to be able to see black-capped chickadees, no matter the camouflage of the snowy branches. My eyes gone soft, the space between the trees would flicker with movement. On rare phone calls with my friend Ray, I realized I was listening the same way—not hunting for what he wasn’t saying about his medical-school unease but just picturing everything he said and waiting for a flicker in the spaces between. My memory was opening, too. As I unloaded groceries from the village market, the songs that had been playing on the overhead speakers would follow like a souvenir map—without any effort, I could remember my progress, lyric by lyric, through the aisles.

At the time, I didn’t know why this was happening, but the invisible lens through which I experienced the world, a lens whose existence I’d never felt or considered—my sense of time, my sense of place, my attention, and my memory—was adapting to help me see in the woods and to help me navigate. Perhaps even stranger, I could only register these changes once Ray found me an oddly perceptive listener, or once my groceries became a kind of radio, which itself was a kind of map, both of my market visit and, more indirectly, of my changing attention and memory.

Our brains evolved to have plasticity in order for us to survive, and evolution did such a good job that the basic structure of the human brain hasn’t needed to change in the past forty thousand years. Our adaptations to new places and ways of life—to being hunters and gatherers in Africa, to navigating the streets of modern-day cities (as a famous study of London cabbies has shown, the gray matter in their posterior hippocampi is notably greater than that of the average Londoner), and now to tapping our way through digital life—all happen within our forty-thousand-year-old brains, through the strengthening of links between neurons, through the growth of new neurons and synapses, and through the release of neurotransmitters.

Basically, we begged out of evolution by developing brains adaptable enough to handle the changes in our physical and cognitive environments on their own. As the Nobel Prize–winning biologist Gerald Edelman pointed out with his theory of “neural Darwinism,” selection works at the cellular level within each person’s life span much as natural selection works at the species level over many generations. Our brains adapt to our environments to help us survive.

But while my brain adapted to less sensory information in the woods, everyone else’s had adapted to more. Screens mushroomed in nearly everybody’s hand—and for a forty-thousand-year-old brain, the flashes and resulting dopamine hits, and the social threats and resulting fight-or-flight responses, might as well have been happening in a new kind of forest. Cognitive traits shifted in ways that were maladaptive to life offline: our attention spans dropped; our ability to be alone waned (six minutes without a phone and subjects in one study chose to receive electroshocks rather than confront “solitude”); and we lost our ability, quite literally, to be where we are (25 percent of U.S. car accidents are tied to texting).

I felt like a tawny owl whose plumage had gone whiter in some remote snowy outpost, only to return to his native woods to find the trees had gone brown due to climate change and now demanded brown plumage to thrive. To live in the new digital woods, you needed not to pay attention to most things and not to remember most of what you saw.

But I wasn’t sure I wanted to lose the brain the woods had given me. Not that I needed to remember every lyric from the aisles of the grocery store. Not that I didn’t want to be able to filter out more of what I saw flashing on screens. But I wanted to hold on to a kind of attention that could wait for answers to questions I didn’t know how to ask, and to hold on to a kind of memory that recalled whatever I needed as a means of orientation, as a way of knowing where I fit in the world.

But the adaptations in my brain wouldn’t be my choice—I could make choices only about my screen time and hope the trades were worth it. Not just the trades on my time, which I could track, and my data, which I couldn’t, but the trades on my cognitive traits. What happens to my attention span for every hour I spend on social media? What happens to my memory? And what happens to my openness to new ideas?

For the majority of the past forty thousand years, there was no possibility of a virtual man-made realm superimposed on the physical realm we walked through, no possibility of getting caught daily between two different environments, and between traits for one realm that were ill-suited to the other.

Now, almost two decades after my return from the woods, I still long for a new kind of map. A map with the digital world and the traits it calls for, and with the old physical world and the traits it calls for, and with the borders clearly marked where the two realms conflict: where the border crossings are treacherous, where we’re bound to lose the parts of ourselves we value. So we know the trades we’re making. So we don’t get lost, and lose ourselves, in the digital woods.

Howard Axelrod is the author of the new book The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age and The Point of Vanishing: A Memoir of Two Years in Solitude, named one of the best books of 2015 by Slate, the Chicago Tribune, and Entropy magazine and one of the best memoirs of 2015 by Library Journal. His essays have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, O Magazine, Politico, Salon, the Virginia Quarterly Review, and the Boston Globe. He has taught at Harvard and the University of Arizona and is currently the director of the creative writing program at Loyola University in Chicago.

Excerpt adapted from The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in Our Digital Age , by Howard Axelrod (Beacon Press, 2020). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Bah, Humbug

Sabrina Orah Mark’s monthly column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

It is December in Georgia, and we are driving past twinkling lights, and wreaths, and mildly poisonous winterberries, and a wire reindeer whose red nose softly glows on and off, on and off. My six year old, Eli, looks out the window.

“Can we have a Christmas tree, Mama?”

“No.”

Silence.

“What if we paint it black?”

I consider this.

The holiday season does not bring out the best in me. I go sour and frantic. Mandatory cheer sinks my spirit. For my sons, I pile up presents for the eight days of Chanukah. The house grows small and dizzy as toys and more toys are torn from their boxes. The menorahs flicker and, yes, they’re beautiful, but if there is a miracle here, who could find it under all this pleasure? “It is possible I am doing everything wrong.” I say this to my husband three times a day, like I’m praying, until December is over. I’m awful at holidays, I know. Years ago, watching the Thanksgiving Day Parade in Manhattan, I was so nervous my whole family would fall off the roof that I was told to sit in the stairwell because I was ruining it for everybody. Where’s my December stairwell? I’ll go sit in it until everybody comes back down.

E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 1817 “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” opens with Marie and Fritz “huddled together in a corner of a little back room.” They hear a “distant hammering,” and shuffling and murmuring, and Fritz tells his sister a small, dark man has crept down the hallway with a big box under his arm. The small man is Drosselmeier. The children call him their godpapa. He wears a black eyepatch, and a wig made from strands of glass. He is as much toy as he is toymaker. “You’re just like my old Jumping Jack,” says Marie, “that I threw away last month.” “Dross” is waste, and “drossel” is to stir things up. And Drosselmeir is both. He is December. He is the month that makes waste inseparable from delight.

“Drossel” also means to choke. And it also means “a thrush,” a speckled songbird. The bird that sounds like a flute in the woods. Over and over again, Drosselmeir is exactly what he isn’t.

Around the time I was trying to get pregnant, and my step-daughter was eight, my husband bought her two goldfish. Over the years the tank darkened, and smelled like old garlic, but the fish thrived. One of the fish (I don’t remember if she had a name) was always pregnant, or having babies, or eating her babies. This is how December makes me feel. Like I am the most un-pregnant person on earth watching a goldfish that is endlessly fertile eat her babies. “I am nothing,” writes Karl Marx, “but I must be everything.”

The holiday season, like a fairy tale, is for breeding the myths we consume, which will nourish us so that we can breed more myths to consume. An elliptical feast! A banquet of myths! We nibble our tales until we get to our head. By the end of December, we are full of ourselves. We are swollen with myth. And then on January 1, we make a resolution to be somehow different than how we are. We clean off our desks, thin out our air, and start again.

I don’t buy my sons a Christmas tree and paint it black, but my mother and I do bring them to the Nutcracker ballet where she buys them each their own wooden nutcracker. Eli clicks the mouth open and shut, open and shut, open and shut, and is shushed. The Balanchine has the muscle of Hoffmann’s story, but not its bite. The astronomer is missing. Marie is now Clare. There is no Princess Pirlipat, and the horror of the mice has been softened into a joke involving a canon that shoots cheese. Eli is wearing his pajamas, and I hear at intermission at least four audience members comment on this. “Is that boy in his pajamas?” I want to remind them that we’re all in a nightmare disguised as a dream. That we’re all fast asleep. That it’s way past our bedtime. But I say nothing instead.

At the end of the ballet the Cavalier almost doesn’t catch the Sugarplum Fairy, and her fury brightens the stage like fake snow.

Like most fairy tales,“The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” is all hole and shell. If there is a kernel, it’s already inside us. There are cracks everywhere: the ones in the kitchen for the mice to come through, the Nutcracker’s broken teeth, Marie’s cut arm, the bites in the sugar figures, the cracks that let fiction leak into reality, the toys running free through shattered glass, and a mother who disbelieves everything her daughter feels.

There is even an extra hole in the toymaker’s face. I imagine a ballerina peeling back Drosselmeier’s eyepatch and climbing into the abyss in his head. I’d follow her. All the way down the socket. Maybe that’s where we’ll spend next December. Inside Drosselmeier. Not where the toys are, but where they begin. A forest of rattles before they are shaken. The stirrings of a doll before her mouth is sewn on. A miniature airplane before its first soar. A four-day, five-night family vacation at the precipice of a man’s imagination.

“And then you wonder,” says my mother, “why Noah has anxiety.” “What do you mean,” I say. But I know what she means. She means my heart is contagious, and my eight-year-old son might be catching what I have. All winter, living with Noah has been a little like living with Werner Herzog. What would happen if there was no wind? Where do we go when we no longer exist? Did you hear that sound? What if love was a person we didn’t know. What would happen if I had no DNA? Can you die from spilling milk on a mushroom? Each question arrives like a pirouette balanced at the edge of a stage only Noah can see. Each question is the dance of one thousand wise sons. “To be radical,” wrote Karl Marx, “is to grasp things by the root.” Noah has a fistful of roots. A stunning bouquet. I sniff them and these questions, to be honest, flood me with relief. It’s when I don’t know where the roots are, that’s when I’m sullen.

None of Noah’s questions comes with a toy. A toy is an answer to a question a child hasn’t learned how to ask.

“My favorite part of the ballet,” says my mother, “is Mother Ginger.” Mother Ginger’s giant crinoline skirt is a house filled with children. The door opens and out they run. The tallest male ballerina plays this birth scene, forward and backward. At the end of the dance, he rewinds the children back into his body, which is also a house and a joke and a spectacle and a garment. Attached to Mother Ginger is a parasol, a fan, a mirror, and tambourine. She is well-stocked, but she can only move sideways. The trick is not to step on the children. The trick is for the children to never grow old.

Mother Ginger is everybody’s favorite part, but it’s not really my mother’s favorite part. Her real favorite part is when the Sugarplum Fairy almost falls, and smacks the Cavalier in the face. “I like when things go awry,” says my mother. She likes seeing the roots, too.

“Where’s your holiday spirit?” asks a friend. “It’s hiding,” I say. “It won’t come out until yours goes back inside.”

I don’t know what’s bothering me. Maybe it’s that I spend a lot of time picking up broken toys, and so it’s impossible to see piles of beautifully wrapped gifts without seeing the shred and the shard. Without seeing the albatross’s belly turned vibrant from the plastics it picks from the ocean. A belly as colorful as a toy shop, and as dead. “Remember,” says my husband, “when there was only one Superman?” And I do. I remember when there wasn’t even one. I remember when all there was, at first, was biodegradable me. What if all a toy really is is just the absence of a mother? This morning I reached into my pocket for my house key, and found a small blue plastic leg instead. Every day I am reminded that ending up where you actually belong might be the biggest miracle of all.

When I was a little kid, I spent every Shabbat at my great-aunt’s house. After lunch, our whole family would sit around the dining room table talking, and singing, and arguing, and cracking open walnuts. The nutcracker didn’t have a face. It was just a pair of long silver legs as strong as a ballerina’s. I cracked open nut after nut, and studied its wrinkles and folds. Its two hemispheres looked exactly like the brain, and this delighted me. I would eat too many, and feel a little sick and happy. By late afternoon, the plastic tablecloth would be covered with shells and fading winter light. I want so badly to bring my sons to this table, but no one is sitting there anymore. As each December cracks open, and leaves only its shell behind, I want to give something to my sons to hold. Something like belonging. Something that will last. But I don’t know what. All I have is this kernel. And it’s too small to see.

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

January 15, 2020

Is Professor Bhaer Jewish, and Other Mysteries

Louis Garrel as Professor Bhaer in Greta Gerwig’s Little Women

Last week, my parents saw Little Women. My mother immediately phoned me. “I think Professor Bhaer is Jewish,” she said, her voice vibrating with barely suppressed excitement. I said I didn’t think the facts supported this theory. But several days later, I got an email from her with the subject line “FYI!!!” When I clicked on the link, I saw it was a Forward piece by Eve LaPlante headed, “Discovering Louisa May Alcott’s Jewish History on Portuguese Tour.”

I knew her game: my mom regarded this as proof that Alcott, apparently proud of her Sephardic ancestry—which, I read, the family credited with some of its dark coloring—had, indeed, written in a sympathetic Jewish foil for Jo. I couldn’t help but suspect that my mother was projecting; just because she had married a Jewish guy didn’t necessarily mean her favorite childhood literary figure had. “I just don’t see the evidence,” I wrote back, not without regret. “Bhaer is pretty Christian in the later books. He’s probably a 48er. And fwiw, the actor Louis Garrel isn’t Jewish, I don’t think.”

“Look into it!” she wrote back. “You are the Bhaer detective!”

I knew what she meant, and my heart sank. You see, a couple of years ago, in these pages, I wrote a five-part investigation of the Little Women character Professor Bhaer. Why? I don’t know. There was no peg. There was certainly no clamoring demand. The resulting tell-all did not contain any dramatic reveals. Serial, it wasn’t.

It’s never fun to reread one’s own work, and less still when the text in question reveals slightly-younger-you to have been some horrible mixture of visibly mad and really boring. But in light of Greta Gerwig’s reimagined Little Women, with its truly disruptive interpretation of the Bhaer character, it seemed worth revisiting the subject. At least, according to my mom.