The Paris Review's Blog, page 187

January 24, 2020

Staff Picks: Dolls, Dakar, and Doomsday Preppers

Francis Bacon’s studio at the Hugh Lane, Dublin, Ireland. Photo: antomoro (FAL or FAL).

At this magazine, we like to think we know a thing or two about interviewing. But to read Interviews with Francis Bacon, the art critic David Sylvester’s book-length dialogue with the painter, is to find a proudly messy rejoinder to our own tidy conversations. Sylvester chronologically presents nine sessions with Bacon over two decades, condensed for length but never edited for clarity or precision. Over the years, in a kind of psychological time-lapse video, the two return to the same topics again and again, and Bacon’s philosophies mutate and crystallize. His interest in the narrative quality of triptych painting evolves to include plans to construct sculptures that can be adjusted and moved. His hedonistic lifestyle becomes a way of thinking about his all-consuming attitude about his work. His desire for realism gives way to a resignation to the artifice of creation. The result is a portrait in dialogue, as warped and fascinating as Bacon’s own depictions of twisted faces and writhing bodies. —Lauren Kane

If you’re a woman between the ages of twenty-six and thirty-five, you probably have, in a deep corner of your parents’ basement, a forsaken stash of American Girl dolls, Pleasant Company’s (later Mattel’s) line of historical character dolls that ascended to popularity in the nineties. I count myself among this cohort and was recently reminded of my own such collection over the holidays. I watched as my cousin’s three-year-old unearthed my old Kirsten doll, messily undoing her neat, long-untouched Swedish braids. One eye on the doll, I sipped my wine, coolly restraining myself from intervening. Last year, a piece in the New York Times directed my attention to The American Girls Podcast, a show in which the thirty-something historians Mary Mahoney and Allison Horrocks explore all things American Girl. Re-examining the historical fiction series that accompanies the dolls, one book at a time, the podcast is part Ph.D.-level history, part pop-culture analysis. Mahoney and Horrocks playfully manage to keep listeners up to date on The Bachelor while also addressing the misrepresentation of slavery and indigenous people in American children’s literature. But the hosts’ chemistry carries them further than the content. They let conversation wander blissfully away from the topic at hand, allowing us a moment, as women, to just enjoy still being girls. —Elinor Hitt

Jenny Offill. Photo: © Emily Tobey.

Jenny Offill makes it look effortless. In the spare, self-contained paragraphs of her 2014 novel, Dept. of Speculation, she combines the profundity of Zen koans with the profanity of an exhausted artist-mother’s interior monologue; that book can be read in two hours, and it holds the intimacy, ease, and mystery of a stranger’s diary (if that stranger had an impeccable ear for language). Offill’s distinctive voice spawned a raft of imitators and helped carve out space for the quotidian concerns of a woman’s life to be taken seriously as literature. Six years later, her newest novel, Weather, risks being read as derivative, so much has the style she pioneered become the dominant mode. Offill chafes at the term autofiction, the ways it has been used to mean something gendered, to mean something new when it isn’t, to mean something insular. Weather is more ambitious. It remarks on our “current climate”—politically, existentially, literally—while also offering a sharp satire of how we use precisely that kind of phrase to contain our terror. Mantras, online prepper guides, and ecological terminology float through the mind of a small-town librarian while a larger global anxiety threatens to subsume her. “Talking about the weather” is transformed from the cliché of alighting on a safe, banal topic into the urgent disaster we all see coming and attempt, for our own sanity, to avoid in polite company. In Weather, the coming winds whip through the consciousness of the narrator, lacerating her, in a way that will be uncomfortably familiar to anyone who has lain awake at night in the past decade. “How does the last generation know it’s the last?” —Nadja Spiegelman

Cassie Donish’s On the Mezzanine is a small book that I’ve found myself returning to since I first encountered its magic last summer. Donish charts the evolution of a new relationship, managing, over the course of seventy-one pages, to erase the very notion of gender from the reader’s concerns (or at least that’s what it accomplished in this reader’s heart). There are echoes of Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts here (and indeed, Nelson’s words of praise grace the cover), but Donish’s poetry is different from Nelson’s. Donish’s gaze is focused on their own heart and that of their partner, a personal history written in the flesh. The result is ultimately an exegesis of what it means to be human, to live in a body, and to love. And God, the writing! These are words that sear and lift and crush, sometimes all in the same sentence, the effect of which decenters heteronormative narrative spaces and creates, instead, its own topography, redefined and redefining. —Christian Kiefer

I was tricked by a friend into leaving my apartment to see a film, only to find out I could have watched it in bed. The deep wound of deception aside, all is forgiven because that film was Atlantics, the utterly beguiling first feature by the French Senegalese director Mati Diop. (I’m late, and the film is leaving cinemas, but please see it on the big screen if you can; or, at the very least, plant your laptop close to your eyes.) Atlantics opens with the image of a spectral glass tower looming above Dakar, a shot that establishes Diop’s cinematic mode, which slips between the observational and the visionary. Construction workers demand pay for their labor on the building, to no avail. One, Souleiman, meets his girlfriend, Ada (in a phenomenal performance by Mame Bineta Sane). They make out by the seaside; she defers his advances until the evening. Later, when she arrives at a bar, she hears from other women that the men have gone “out to sea,” toward Europe and, it appears, to their death. She sees Omar, her wealthy fiancé, who gives her a phone and then swims, with what scans as contempt, in the still water of an infinity pool that vanishes at the restless sea ahead. The sly insights on wealth, power, gender, and class accumulate. Then, things happen. I don’t want to reveal what the film becomes, but I found it a comfort to have no sense of where the shifts in tone and mood would lead. Though the Atlantic is an ever-present image, its significance is constantly in flux. I have rarely seen the ocean shot so well and with such variety: the way it glints in the dark, roils with threat, or glows with a rose-pink haze. Love blooms, as ever, in retrospect. But what resounds is the grace with which the film turns the hauntings of the past toward the future. —Chris Littlewood

Still from Atlantics. © Les Films du Bal.

Playwright, Puppeteer, Artist, Cyclist

For the avant-garde playwright, puppeteer, critic, novelist, artist, and cyclist Alfred Jarry, life was a series of artful acts. Perhaps best known in his day for the controversial play Ubu Roi, Jarry is often credited with helping spark the fires of surrealism, Dada, and futurism. “Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being” (on view at the Morgan Library and Museum through May 10) is the first major U.S. museum exhibition of his work; it demonstrates the breadth of his artistic practice. A selection of images from the show—including photographs of Jarry’s experiments with typography and woodblocks—appears below.

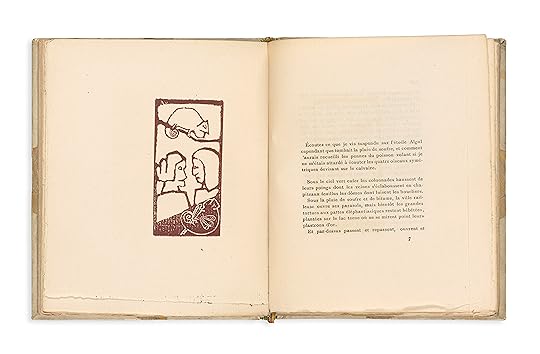

Alfred Jarry, Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Alfred Jarry, “Ubu roi,” in Livre d’Art no. 2 (April 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Alfred Jarry, autographed manuscript of three poems “after and for” Paul Gauguin, ca. 1893–1894. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2019. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Alfred Jarry, César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Alfred Jarry, Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Alfred Jarry, Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Alfred Jarry, César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

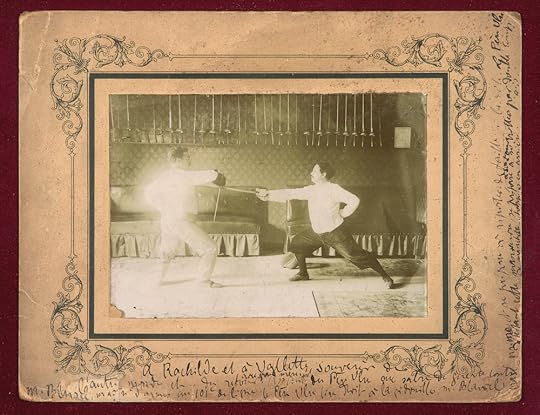

Alfred Jarry (at right) fencing with Félix Blaviel in Laval, 1906. The Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection.

Alfred Jarry, Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Photo: Janny Chiu.

All images from the Morgan Library and Museum’s “Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being,” on view through May 10, 2020.

Pendulum

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces the moments before her daughter leaves for college. It ran every Friday in November and returns this winter month, then will return again in the spring and summer.

I grew up inside the smoke of my grandmother’s Pall Malls. The air between her and my mother was dangerous. On our visits to east Texas, the two women would sit in stiff silence for what seemed like hours to my six-year-old sense of time. My mother sat on the brocade couch, my grandmother in her gold velour chair. In every room, there was at least one painting of flowers—roses or daises—all of them done by my grandmother. I’d sit on the floor, counting the chimes from the grandfather clocks in the hallway, not one of which kept the same time as any other. After my grandmother had wandered off to the back room to clink the crystal decanter against her highball glass too many times, we’d go. My mother never left without leaning over that gold chair to kiss her mother goodbye. She never left without saying, “I love you,” like a sigh you let out when the night’s too long. Then that high-chinned stride for the screen door. Every time, just before my mother pushed it open, my grandmother would surrender: “Love you, Martha Jo.”

The day I found out I was having a girl, I sat in my car in the parking lot of the doctor’s office and sobbed. Deep, ragged sobs.

A few months after my mother died, I was in her kitchen with Mary and Jean, her two best friends, whom she had known since the first grade. While I pulled down pieces of china from the kitchen hutch and wrapped each one in newspaper, Mary and Jean helped my daughter, Indie, then sixteen, pack her own set of dishes, the ones my grandmother gave to my parents when they married in 1969. That china set was hand-painted with pink roses, had gilded handles and my grandmother’s initials on the bottom of each delicate piece. Mary and Jean’s mothers had taken the same painting classes as my grandmother. As Mary liked to say, “What else was there to do in that small town in the fifties?” Mary and Jean still live in that small town. I placed an empty box on the kitchen table and asked the question I had never been able to ask my own mother: “How bad was my grandmother’s drinking?” None of us stopped packing while they took turns telling stories—my grandmother’s long drives to the closest wet county, the afternoon she “took a nap” during one of their Girl Scout meetings, an ad she put in the newspaper for her lost red purse with two possible locations where it might have been left.

My mother-grief trembles. Regret, apology, a deep missing. When I sit inside it—as when I pull on one of her sweaters or use her measuring spoons or listen to her Patsy Cline CD—the ache feels like a cacophony of clock chimes. My mother and I never kept the same time.

After all the boxes were taped, Mary and Jean grabbed their purses. I walked them out to the driveway and said I didn’t feel like my mother ever really liked me. Mary hugged me close and whispered in my ear, “Jill, she loved you.” Jean sighed, “She just never learned how.”

Eighteen years ago, with my daughter growing inside me, I knew I contained a difficult history—my mother and her mother, my mother and me. I could feel it ticking, ticking, ticking.

After I left home for college, I often went to east Texas alone to visit my grandmother. As a child, I’d only known the lonely widow who kept cashews on the kitchen counter, the woman who pretended there wasn’t bourbon in the back room. I wanted to know more. During those solo visits, she’d tell me stories—about my mother, the man she sent a Dear John letter to during the war, the time she caught my mother and Mary smoking (Mary denies this)—but mostly she’d gossip about the neighbor across the way. Sometimes we’d laugh so hard she’d fall into a fit of Pall Mall coughing.

Indie has the same shoe size as my mother and kept some of her shoes. Her favorite is a pair of black suede bootees with a thick wedge heel. She wears them every time she has a band concert, an audition, something special. Last week, before leaving for a jazz festival, she came home from the store with superglue, said that one of Gramma’s heels had come loose.

Most nights, Indie and I like to sit on the couch and watch one of our shows. She puts her feet in my lap, and every few minutes, we hit pause to tell each other a story from our day or update an ongoing saga: “Okay, do you remember when I told you?” One-hour shows take us two hours to finish. We like to stretch the time.

I never knew how much Indie and my mother talked and texted until Indie opened a present, one of the last ones, it turned out, that my mother gave her. It was a floral duvet cover, black with gray and rose-pink colors. “We picked it out together,” Indie told me. Sometimes when I’m in Indie’s room, I smooth the flowers on the bed.

In the hospital, when I knew it was time to say what I needed to say to my mother, I held her hand and began, “Thank you,” and as I continued, the words that were pushing from the back of my throat—the ones I really wanted to say—wouldn’t come out. I’m sorry.

When Indie was an infant, I’d sit on the couch with my feet on the coffee table, my knees bent. I’d place Indie on my thighs and take her hands to sing “Do-Re-Mi.” I made up hand movements for each note—so that she’d trace sundrops as if they were falling rain for re, tap, tap, tap her own heart for mi, and pump her arms for the long run of fa, her favorite. She doesn’t remember it. But I do. I remember it as the first time I knew we would reverse the pendulum’s swing.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

January 23, 2020

The Silurian Hypothesis

In his monthly column, Conspiracy, Rich Cohen gets to the bottom of it all.

When I was eleven, we lived in an English Tudor on Bluff Road in Glencoe, Illinois. One day, three strange men (two young, one old) knocked on the door. Their last name was Frank. They said they’d lived in this house before us, not for weeks but decades. For twenty years, this had been their house. They’d grown up here. Though I knew the house was old, it never occurred to me until then that someone else had lived in these rooms, that even my own room was not entirely my own. The youngest of the men, whose room would become mine, showed me the place on a brick wall hidden by ivy where he’d carved his name. “Bobby Frank, 1972.” It had been there all along. And I never even knew it.

That is the condition of the human race: we have woken to life with no idea how we got here, where that is or what happened before. Nor do we think much about it. Not because we are incurious, but because we do not know how much we don’t know.

What is a conspiracy?

It’s a truth that’s been kept from us. It can be a secret but it can also be the answer to a question we’ve not yet asked.

Modern humans have been around for about 200,000 years, but life has existed on this planet for 3.5 billion. That leaves 3,495,888,000 pre-human years unaccounted for—more than enough time for the rise and fall of not one but several pre-human industrial civilizations. Same screen, different show. Same field, different team. An alien race with alien technology, alien vehicles, alien folklore, and alien fears, beneath the familiar sky. There’d be no evidence of such bygone civilizations, built objects and industry lasting no more than a few hundred thousand years. After a few million, with plate tectonics at work, what is on the surface, including the earth itself, will be at the bottom of the sea and the bottom will have become the mountain peaks. The oldest place on the earth’s surface—a stretch of Israel’s Negev Desert—is just over a million years old, nothing on a geological clock.

The result of this is one of my favorite conspiracy theories, though it’s not a conspiracy in the conventional sense, a conspiracy usually being a secret kept by a nefarious elite. In this case, the secret, which belongs to the earth itself, has been kept from all of humanity, which believes it has done the only real thinking and the only real building on this planet, as it once believed the earth was at the center of the universe.

Called the Silurian Hypothesis, the theory was written in 2018 by Gavin Schmidt, a climate modeler at NASA’s Goddard Institute, and Adam Frank, an astrophysicist at the University of Rochester. Schmidt had been studying distant planets for hints of climate change, “hyperthermals,” the sort of quick temperature rises that might indicate the moment a civilization industrialized. It would suggest the presence of a species advanced enough to turn on the lights. Such a jump, perhaps resulting from a release of carbon, might be the only evidence that any race, including our own, will leave behind. Not the pyramids, not the skyscrapers, not Styrofoam, not Shakespeare—in the end, we will be known only by a change in the rock that marked the start of the Anthropocene.

It was logical for Schmidt and Frank to turn their attention from the upper to the under, from the cosmos to our own earth. Why look for alien life there when we might find it here, removed not by miles but years. There was indeed a mysterious jump in surface heat; 55 million years ago, global temperatures rose from 9 to 14 degrees Fahrenheit. Called the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, it left the same sort of geological evidence that will be left by our current carbon binge. There may have been other jumps, but we wouldn’t know it, as the geologic record only goes back so far. (We live in a compactor, where all things are crushed, recycled, and returned as new.) A meteor could’ve caused the Thermal Maximum, or it could’ve been the eruption of a monster volcano, the sort that presently smolders beneath the Atlantic. Or it could have been caused by the awakening of an ancient civilization, which rose like we rose, then fell as we will. That could be the fate of all advanced species, a rise and fall that flows as naturally as the change of seasons. Such a universe is ironic, continually creating characters whose technology brings on the very end they’re trying to avoid.

When Schmidt and Frank searched, they found a single forerunner to their idea of deep time. It came not from science, but from science fiction. At this level of conjecture, there’s little difference. It was an episode of Dr. Who, in which the time traveler visits an ancient species of advanced, long-extinct lizard people who’d achieved technological mastery 450 million years before modern man. The lizards were called Silurians, hence the Silurian Hypotheses.

It’s not really a new idea. Ancient mystical texts hint at earlier creation, the life that preceded the Garden, prequels to Genesis. These incarnations are not reported in the Bible because they are none of your goddamn business, but the evidence is everywhere. Some students of conspiracy believe there was a time when lizard people shared the earth with modern men, the older race dying as the younger emerged from the forest. The last of the lizards were worshipped as gods; these were the deities of ancient India and Greece. The technology—weapons and machines—created miracles. You can see the lizard kings in carvings from Mesopotamia, the oldest historical records, where humans bow before reptile men. You find them again in the Torah, where they appear as Nephilim, the so-called watchers—“The Nephilim were on the earth in those days and also afterward when the sons of God went to the daughters of humans and had children by them,” according to Genesis, “they were the heroes of old, men of renown”—which no priest, minister, or rabbi can properly explain. Just ask a clergyman and see for yourself. (I asked my rabbi.) There is some weird shit in the Bible.

According to a kabbalah-besotted friend, this world is God’s seventh creation, which explains dinosaur bones and other fossils. “The evidence is everywhere,” he told me one night. “They can say a meteor wiped out the past, but what is a meteor? God.” Some believe there are still Silurians walking the earth, holdovers who share their technology with a hidden elite—possibly Freemasons, possibly Jews. Some pseudoscientists speak of an atomic blast that took place in India 10,000 years ago. It might’ve been a natural phenomenon, or might’ve been the war that wiped out the Silurians or drove them off the earth. A website called Vedic Knowledge reported evidence “of an atomic blast dating back thousands of years. It destroyed most of the buildings and probably a half-million people in Rajasthan, India. One researcher estimates that the bomb used was about the size of the ones dropped on Japan in 1945.”

This ancient catastrophe, which some take as evidence of an ancient nuclear war, shows up in the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit epic, with the appearance of “a single projectile charged with all the power in the Universe … An incandescent column of smoke and flame as bright as 10,000 suns, rose in all its splendor … it was an unknown weapon, an iron thunderbolt, a gigantic messenger of death which reduced to ashes an entire race.”

It’s heartbreaking—the fact that, as we face the nightmare of climate change, some of us have read our own perilous present back into the geological past and have come to see even our apocalypse as unremarkable, something that’s been experienced before and was inevitable from the start. It’s thrilling, too, the idea of a pre-human industrial civilization. It means we don’t know anything: who we are, or where, or even the history of our own home.

Read more of Rich Cohen’s Conspiracy column here.

Rich Cohen is the author of The Last Pirate of New York: A Ghost Ship, a Killer, and the Birth of a Gangster Nation.

Less Is More

Writing a book about minimalism opens you up to a lot of easy jokes. There’s the simplest, the mismatch of form and content: You wrote a whole book on minimalism? That’s not very minimalist! Then there’s the added wrinkle of the book’s size: How could minimalism fill such a long book? (In my defense, the book I wrote is only a bit over two hundred pages.) People ask if they should actually buy the book, since it’s not minimalist to own extraneous objects. (Please do—buy the e-book if you must.) Someone suggested that instead of text I should have just published a volume of empty pages: the only form of writing that could be properly minimalist is no writing at all.

In fact, many minimalist books have already been written. In the context of literature, the word is associated with a hard-boiled quality, like Raymond Carver or Bret Easton Ellis: terse sentences, tight plots, literalism. Or it can be in reference to scale, like flash fiction, in which a large effect is created within a small space. Diane Williams is a minimalist, as are haiku and Zen koans, fragments of language. I have begun to think that autofiction is our dominant form of minimalist writing today because it dispenses with some of the usual qualities of fictional literature, like dramatic plot, character arcs, and the boundary with nonfiction, in the same way that an artist like Donald Judd left out human figures, varied colors, and aggressive brushstrokes from his works. Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy is minimalist because it leaves the narrator blank, a protagonist who listens instead of acts.

But my book, The Longing for Less, is mostly about the visual associations of minimalism, in art, design, and architecture. Those forms have an antipathy of language and resist subtle description. There aren’t enough words to capture the various shades of visual emptiness—I’ve used blank, austere, and spare too many times to tally without hating myself. Labeling something indescribable is an excuse for lazy writing, yet it seems to apply here. Writing that one of Judd’s works is a box made of unpolished aluminum about a meter square, with its longer sides empty so that you can see through it, is both literally correct and missing the point entirely, like describing a Picasso only as oil and pigment caked on stretched cloth.

At one point I went maximalist in frustration, spending many ekphrastic paragraphs on the epiphany of seeing a Judd box from multiple angles, the shallow pool of empty space in its top, the psychedelic effects of the SoHo sunlight glinting off its powder-coated angles in the upper floors of the artist’s loft home. My editor wisely cut it down to a few sentences.

Minimalist art is meant to exist for and as itself. There is no interpretation or explanation needed—it’s all evanescent effect. By contrast, all language seems like explanation, particularly in nonfiction. As soon as you point to something in writing, it’s there, even if what you point to is the empty floor. Words break the delicate emptiness of a room or the thoughtlessness of pure observation without judgment, which is what I came to think minimalist art is actually about.

Judd, who began his career as a prolific critic, wound up hating words. He used language to summon the absence of language. In his notebook in 1986 he observed a jackrabbit hopping in the grass in rural Texas, where he lived. “The desert was spare, as usual, but very green and beautiful. I realized that the land and presumably the rabbits, quail, lizards, and bugs didn’t know that this was beautiful,” he wrote. “The observation is only ours, the same as the lizard’s opinion of the bug. The observation has no relevance, no validity, no objectivity, and so the land was not beautiful—who’s to say. It simply exists.” Or, as the 1953 John Cage poem that I used as my epigraph puts it: “No object / No beauty / No message.”

Judd was constantly aggrieved by the idea of minimalism as a movement, which he didn’t identify with. He saw it as marketing shorthand. “Instead of thinking about each person’s work, critics invent labels to pad their irrelevant discourse,” he wrote in a letter to the Village Voice in 1981. It’s true, but we critics do it because we have to: language is a way of communicating the abstract ideas of art to an audience that might not be amenable to them otherwise. The simplification is a necessary evil, despite the artists’ feelings. And simplify it does, unfortunately: “When I hear the same nonsense about Minimalism and impersonality for twenty years, I realize that the clichés have stuck,” Judd wrote in 1984.

The painter Agnes Martin wrote, too, though much less frequently, from statements on her work to more abstract poetry. Her writing is also anti-language, offering koans that must be resolved by the reader. “It is commonly thought that everything that is can be put into words. But there is a wide range of emotional response that we make that cannot be put into words,” Martin wrote in “Beauty Is the Mystery of Life.” “We are so used to making these emotional responses that we are not consciously aware of them till they are represented in art work.”

Martin’s ethereal grids and stripes evoke rather than describe. They present a form of transcendence that writing usually fails at, a heightened emotional plane in which the artifacts of the human world fall away. “My interest is in experience that is wordless and silent, and in the fact that this experience can be expressed for me in art work which is also wordless and silent,” she wrote. Late in her career she chose titles like Beautiful Life, Happiness-Glee, and I Love the Whole World. I wouldn’t call these good writing, but the language was not the point. Under minimalism, “metaphor died,” as the critic and artist Brian O’Doherty wrote. Like Judd’s description of the desert, art “simply exists,” and that is enough.

Philip Johnson, the figure most responsible for propagating the minimalist aesthetic by popularizing modernism in architecture and design in the United States, also spoke out the most vociferously against language. “The word kills art,” Johnson proclaimed in a 1955 speech at Barnard College. “The word is an abstraction and art is concrete. The word is old, loaded with accreted meanings from usage. Art is new.” Language always gets bogged down in its past; only art can surpass it and create something truly unprecedented—or so he argued. It could be a boast for Johnson’s own Glass House, which envisioned its own new way of living in 1949.

This idea that anything can emerge fully formed from a blank slate without history or context is one of the dangers of minimalism, which has a tendency to erase its own origins. (Johnson affiliated for years with the Nazis, who maintained their own regime of aesthetic homogeneity.) Charting the history and heritage of minimalism in its varied forms and iterations is one way of complicating the idea, allowing for more interpretations to coexist.

Ironically, it was a writer who first came up with the fateful phrase “less is more.” It’s usually credited to the architect Mies van der Rohe and associated with the chilly minimalist geometry of his glass-and-steel buildings, in which less visual stimulus leads to more effect. But the phrase actually first appeared in English from the Victorian poet Robert Browning, who was decidedly maximalist.

In an 1855 poem, Browning wrote from the perspective of Andrea del Sarto, an Italian Renaissance painter who was known for his technical brilliance. Browning’s del Sarto delivers monologues to his wife, Lucrezia, confessing his own ultimate lack of emotion. Other painters try to match the skill that he seems to display so effortlessly, but they end up achieving “less, so much less.” “Well, less is more, Lucrezia: I am judged,” del Sarto admits. “There burns a truer light of God in them.” The other painters are able to capture the deeper truth that del Sarto misses as he focuses too much on the cold exactness of each line. “All is silver-grey, / Placid and perfect with my art: the worse!”

So “less is more” is a complaint instead of praise, and placid perfection a fault. The harder you try to nail something down, the more it escapes. My mistake.

Kyle Chayka is the author of The Longing For Less: Living with Minimalism, out this week from Bloomsbury.

January 22, 2020

Cole Porter’s College Days

Cole Porter, Yale College Class of 1913

My father graduated from Yale in 1913.

At the time, getting into Yale must have been a bit like making a reservation at 21. If you were one of the fortunate few, the only real question was did you want a table at seven thirty or eight thirty.

He played football (“badly, very badly”), was a member of the mandolin club, and was fired early on as drama critic at the Yale Courant for asking Sarah Bernhardt rude questions about her love life.

In later years, he found that boys from his dorms, ones with names like Pinky, Weasel, and Lefty, were now ambassadors to Sweden, vice presidents of General Electric, or on the board of the Federal Reserve. And he came to remember that one of the boys down the hall, someone he barely knew back then, was Cole Porter.

“He had this boola-boola image that he liked to present in his songs about all the camaraderie and good times of college life, but he wasn’t very well liked. Just the opposite. He was a little guy, sort of awkward and a bit of a loner, and he was pretty badly teased. More than teased. The football players used to stuff him in a laundry basket and roll him down several flights of stairs. I never did that. But I also never tried to stop them. I should have. I didn’t.”

They reconnected, briefly, when my family got financially involved in his musical Kiss Me Kate in 1948 and held backers’ auditions at my parents’ Midtown apartment. As my dad recalls:

I took him aside before the audition started, we went out on the terrace, and I mentioned Yale and the rooms I’d been in, and he just nodded. Those couldn’t have been happy times for him, no matter how he liked to present them. He was bullied pretty badly.

“Oh, they weren’t so bad,” he shrugged.

I reminded him about the laundry basket banging away down the stairs. Bump. Bump. Bump.

But he shrugged again and pulled out a cigarette case, a gold cigarette case, and he lit up a cigarette. He didn’t puff on it, he just held it there in front of him and looked at it and nodded.

“It wasn’t so bad,” he said, finally. “At least they left all the laundry in it. So it didn’t hurt that much.”

The Letters of Cole Porter , edited by Cliff Eisen, was recently published by Yale University Press.

Brian Cullman is a musician, producer, and writer living in New York City.

Announcing Our New Publisher, Mona Simpson

Mona Simpson. Photo: Gaspar Tringale.

The Paris Review Foundation is delighted to announce the appointment of Mona Simpson as the magazine’s new publisher. Simpson succeeds Susannah Hunnewell, who passed away in June 2019. Previous publishers include founding publisher Sadruddin Aga Khan, Drue Heinz, Deborah Pease, and Antonio Weiss.

Simpson began her involvement with The Paris Review as a work-study student in Columbia’s M.F.A. program, eventually joining the staff as a senior editor, serving in that capacity for five years. During her tenure, Simpson convinced George Plimpton to provide the staff with health insurance for the first time, and she discovered several unknown authors in the magazine’s slush pile, a number of whom have gone on to become significant voices in contemporary literature.

During her time as an editor, Simpson completed her first novel, Anywhere but Here. She left the magazine for Princeton’s Hodder Fellowship. She held the Samuelson Levy Chair in Languages and Literature at Bard College, where she is now a visiting writer, while on the faculty at UCLA. She has been a member of the board of directors and the editorial committee of The Paris Review since 2014.

Simpson is the author of six acclaimed novels, which have been widely translated. A film was adapted from one of them. She’s received many awards for her fiction, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, an NEA award, the Whiting Award, the Lila Acheson Wallace–Reader’s Digest Award, the Heartland Prize, the Mary McCarthy Prize, and a Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This year, her short story “Wrong Object,” first published in Harper’s, is included in the Best American Short Stories anthology. Her seventh novel, The Humble House, will be published next year.

We welcome Mona into her expanded role with The Paris Review!

Alasdair Gray, the Man and the Work

Alasdair Gray (courtesy Rodge Glass)

One night in summer 2015, under a vast night sky mural in the Òran Mór Arts Centre auditorium in Glasgow, there was a film showing. In fact, two. The subject of both, Alasdair Gray, once an intense, asthmatic working-class boy from northeast Glasgow and now Scotland’s most celebrated literary artist, was in the audience, fidgeting and scratching as he watched. Above us, I could see his Garden of Eden mural writ large on the ceiling, despite the low light. I was also scratching myself—seeing Alasdair do it always made my eczema worse. I was waiting for the right moment to ask him to sign a picture for my baby daughter. He was eighty, at the time. I was afraid I might not see him again; I was living in England. Now, in the weeks after his death, days after I’ve moved back to Glasgow again, I wonder how to make sense of his loss. Our conversation that night, conducted while watching the pop-up screen, made me re-engage with his work in a new way. And it gives me something to do now he’s gone.

Over the twenty years we knew each other Alasdair was always charitable with me, unfailingly kind and supportive, even though the publication of the biography I’d written about his life, a not entirely uncritical book, was difficult for him. But honesty matters, now: ours was a pretty one-sided relationship. I was forty-five years younger than Alasdair, a young fan when we met in 1999. I was one among so many aspiring writers, keen to learn, dizzied by his achievements, and by the way he seemed both extraordinary and ordinary. Gray referred to himself as “an increasingly fat Glasgow pedestrian”; the novelist Will Self called him “a little grey diety.” Alasdair used Tipp-Ex to write his name onto his rucksack in distinctive capitals—he designed his own font—then carried it around the streets of Glasgow’s West End while locals and tourists whispered about who they’d just spotted on the street. He was the internationally regarded author and illustrator of Lanark, Poor Things, Unlikely Stories, Mostly, and 1982, Janine. He was responsible, along with the likes of Liz Lochhead, James Kelman, Agnes Owens, and Edwin Morgan, for transforming the Scottish literary landscape Morgan had once called “a wasteland” into the rich, varied, diverse, and outward-looking place it is today. He made Glasgow the subject of his life’s work, creating “imagined objects,” as he called his creations, about his disappearing, changing city. In Lanark, the famous line, “not even the people of Glasgow live in it imaginatively” was rendered obsolete by his own achievements. No wonder people whispered when he passed them on Byres Road.

I first met Alasdair when I served him a drink at a pub, then was his tutee at the University of Glasgow when I was working on my debut novel (he once rewrote an entire chapter by hand, sticking bits of paper on with glue to cover over my words). Later, I worked for him as secretary, dogsbody, driver, and much else besides. My writer’s education took place in his bedroom, on a cheap chair at his bulky old computer, while he waved his finger shakily over my shoulder, shuffling words around on the screen, writing his books off the top of his head as I typed. He sang music hall ditties on the toilet. He was free, and maddened, and maddening, too. He was utterly single-minded at times, easily distracted at others. He was disarmingly honest and was often taken advantage of by others. From the day I began work at his home, Alasdair insisted on paying me a “tradesman’s wage,” which was sometimes more than he was earning himself, and certainly more than I’d been paid at the pub. Over the four years I worked with him, Alasdair turned plays into novels, recycled emblems and vignettes, reused and reworded old sentences he felt he hadn’t got quite right decades earlier. He wrote a novel based on rejected radio plays from the seventies and once fell asleep trying to finish off a political book, having got horribly distracted by the Act of Union of 1707. It was not a regular job.

He was the most inspiring individual I’ve met and he shaped my worldview. In more recent years, though I’ve grown up, moved away, had a family of my own, and mostly concentrated on my own work, I’ve always returned to both the man and his work. In the avalanche of good wishes, emails, pictures, sketches, and videos sent by well-wishers in recent weeks—some just wanted to tell their Gray anecdote to someone, so they told me—I felt grateful to find out new things about the life I had spent so long trying to piece together. One man contacted me with details of Alasdair’s anti-apartheid work with South African writers, way back when. Another sent a personal sketch doodled inside a book. Another, a copy of a letter I had long ago typed for Alasdair while he boomed with laughter behind me. Despite his death, because of it, people kept bringing him back to life.

The first film shown in Òran Mór was a rarely seen BBC documentary, Under the Helmet, from 1964. In flickering black and white it showed a stick thin, serious, be-suited young Alasdair Gray looking into the camera saying, “This isn’t how I talk to my wife. This is how I talk to a television machine.” By today’s standards, the pace of the film was achingly slow, the tone dry. The camera panned steadily over Gray’s visual works, lingering on details while the artist read his grim poetry over the top. A black Adam and white Eve, embracing, their chins locked together facing skyward on a Glasgow church wall, soon to be demolished. The serpent, feet sticking out, looking on. In Under the Helmet, the documentarians indirectly suggest that their buttoned-up subject was no longer alive, believing a dead young Scottish artist might be more interesting to viewers than a live one. They had good reason for that suspicion. Gray had been ignored by critics and the public, painting his murals for free, sleeping on floors. Soon, his major early murals would be knocked down, neglected, marginalized, painted or papered over. This would keep happening for another forty years before a radical reappraisal in his old age. In the early sixties, Gray’s literary reputation was also still in its infancy, with Lanark nearly two decades from publication.

I first watched Under the Helmet on an old video copy while writing my Gray biography. At the time, what preoccupied me was the detail: which works were featured, how they were featured, and what material difference the broadcast made to Gray’s working life at the time. Soon after it aired, he published a piece called “An Apology for My Recent Death.” Meanwhile, the documentary made him connections that led to radio play commissions in London. But seeing the film a second time, something struck me that suddenly seemed incredibly obvious. The program had been curated by Gray himself, with one aim: to focus on the work, backgrounding the artist. In the near-darkness of Òran Mór, the old Alasdair watched his younger self quizzically. He was unsure what to do with himself. At one point, his whiskey sloshed onto my hand as he talked. His opinion on how art should be perceived, he whispered, had not changed in the intervening fifty years. Using almost exactly the same words as the Alasdair on the screen, Gray complained into my ear that artists are so often seen within the context of their personal lives, and that these things have nothing at all to do with art itself. I remember smiling. “I respectfully disagree, sir,” I said, in my bad impression of a Radio 4 voice. “But then, I would.” I think he laughed, though maybe it was a wince. I wish I’d just had the courage to listen and not speak. These are the things that bother you, when someone dies. The stupid things you said. How you can’t unsay them.

The second film shown that night, made by director Kevin Cameron and again broadcast by the BBC, this time for Gray’s eightieth birthday in 2014, was a different beast entirely. But for the subject’s distinctive reedy, stuttering voice and his way of moving his head when talking, it might have been a film about someone else entirely. This artist was a confident extrovert—overweight, joyful, loud, often laughing or talking in different accents—shown designing the subway mural at his local station, or wobbling on the scaffolding of his greatest work at Òran Mór, totally consumed by painting, which he said was more relaxing than writing because it was physical exercise as well as mental. In this incarnation Gray was still highly self-aware, but he was now playful with it. He had already achieved his aims. Against the odds, Gray had become famous in his own lifetime, an overnight sensation in middle age. After Lanark, he produced over thirty books and a thousand paintings, portraits, illustrations. and murals. This was the man many in Scotland and around the world now recognize, the so-called national treasure (he hated that), the socialist, the democratizer, who said his favorite sound was the “the sound of deadlines whooshing past my ears!”–and whose misattributed quotation (“Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation.”) adorns the Canongate wall of the Scottish Parliament. Who turned down a knighthood, honorary degrees, and literary awards, and who reveled in replying to aspiring writers that no, sorry, he couldn’t help them get published because he was “such a selfish auld bugger.”

Cameron’s film is done with subtlety and affection, and no small amount of insight, though Gray the man, the personality, is very much front and center. In one scene, Alasdair is shown hungover, having lost the plans for the next stage of his Òran Mór mural. He looks every bit the hapless alcoholic as he ambles down the road from his house, manic with fear at all that work wasted. (The plans were later found in the pub.) While watching, Alasdair turned to me and said, “I do understand why folk show me this way. But I wish they’d just concentrate on the work.” I’m not going to pretend I know if he was referring to me, too, in that comment, but whether he was or not doesn’t matter. I know that’s what I did in my biography. So concerned to get the man on the page for future generations, his voice, his movements, his opinions, his loves, and his losses, I sometimes forgot to foreground the work. Which is why, after that night in 2015, I told Alasdair I would return to writing about him, but this time concentrating on the work and its legacy. The last conversation we had in person discussed all the ways we might approach this together in years ahead. “If I’m spared,” he said, as he always did. After he was confined to a wheelchair, that sentence held greater weight.

Over the next few years, I’ll be closer to Alasdair’s Gray work than ever. I’ll be convening a conference in Glasgow reappraising his art, which was for too long seen as a small room in the house of his reputation. I’ll be commissioning new works that respond to Alasdair’s, as he responded to those who came before him. Meanwhile, he and I were due to appear together at Glasgow’s Aye Write! Book Festival in March to discuss his last book, Purgatory, part two of his response to Dante’s Inferno. We spoke about it shortly before he died. Instead I’ve curated an event featuring writers, artists, and friends who will read from his writing and discuss his work, its scope, its impact. The event will be called Remember Alasdair; I expect it to be busy and emotional. But after our discussion in Òran Mór, we will focus on the work. Many of us will miss the man. The man was worth remembering. But it’s the work that matters most.

Rodge Glass is a novelist, senior lecturer in creative writing at the University of Strathclyde, and Alasdair Gray’s biographer.

Who Are the Hanged Men?

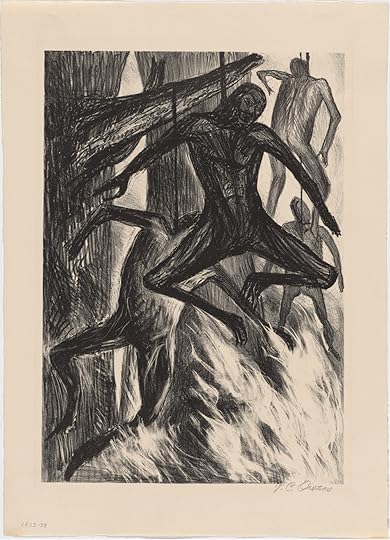

José Clemente Orozco, The Hanged Men from The American Scene, no. 1, 1933–34, published 1935. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City.

Who were these bloated neutered monsters hanging in the branches, who become the branches, the forest, barklike limbs, truncated, cut down, howling, angled, parched, rocked by the wind-kicked flames that lick, then tickle, then singe, then engulf?

Why so many here in such disarray of splay? Who is the victor? Who wins when the torture is complete, this death upon death? Who gazes upon the eyeless socket, the seedless groin, the voiceless lips that crack under suspicion? What is this thing born guilty before being proved human? How is it able to possess a supernatural capacity to be lazy, shiftless, yet to rape, be conniving, thieving, uppity, unctuous enough to speak, to yell at, scream at, lash out in frustration at your changing rules, your shifting laws, your erased boundaries? How has it deserved this fate? And why will it not die? How are you unable to kill it to your satisfaction?

Erasure, no time for it—is there a crayon black enough to portray the heart of the American Scene? Nineteen thirty-five was also the year of my great-grandfather’s unceremonious Southern death. The drama of the Jim Crow lynch system, medieval in its execution, modern in its speed and dissemination of photos and souvenirs. The laws were simple: to be black, in skin or heritage, is a death sentence. The body that houses the supernatural ailment “nigger” is readily dissolved by the teamwork, rope, and flame of white supremacy. The prize? Skin, kinky blood-matted hair, a severed ear, finger, or penis, a postcard made the night of the “picnic.” Skinned. Cleansed. Sacrificed, but to what bloodthirsty god?

The psychosis apparent to José Clemente Orozco was not unfamiliar territory for the great muralist, who specialized in social commentary and the history of the Americas and thus was not a stranger to violence in all its extremes. The plight of the powerless is universal, the powerless who are aware of their human rights—they are the New Negro. Our old twentieth century ushered in new revolutions of the spirit and, with them, new forms of suppression, new aesthetic geometries, mass-produced graphic arts to meet mass graphic violence. Impassioned and dispassionate, using colorless and raw lithographic crayon—the tool of the social-realist painter—the work is ready for reproduction, ready to supplement the voice of the imperiled and annihilated.

Where is the moral? The uplift? The right that will meet this apparent wrong? Why does the artist fail to show the heroes in our midst fighting for justice, fighting to legitimize the law? Why does he not expose the perpetrators? The NAACP requested this work for an exhibition on racial violence, so why are we even looking at this? We are the good guys, we would never commit crimes this heinous, we would never fail to recognize the humanity of others, we were victims once, too! We haven’t got a prejudiced bone in our bodies. We detest violence in all its forms, we are pacifists. We chafe at the sight of this image; our arms go numb and stiff. Our skin crawls. Our blood runs cold. Tears fill our eyes and our throats tighten. The flames lick our toes. Our thighs begin to burn, crackle, and stiffen. Our arms extend at angles away from our distended bellies, and we are left hanging.

Kara Walker is best known for her candid investigation of race, gender, sexuality, and violence through silhouetted figures that have appeared in numerous exhibitions worldwide.

Excerpt from Among Others: Blackness at MoMA © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

January 21, 2020

Redux: Two Eyes That Are the Sunset of Two Knees

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

John Fowles. Photo: Carolyn Djanogly.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re inspired by the art of dance. Read on for John Fowles’s Art of Fiction interview, Vilma Howard’s short story “Belle,” and Frank O’Hara’s poem “Ode to Tanaquil Leclerc.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And don’t forget to listen to Season 2 of The Paris Review Podcast.

John Fowles, The Art of Fiction No. 109

Issue no. 111 (Summer 1989)

I am a great believer in diaries, if only in the sense that bar exercises are good for ballet dancers: it’s often through personal diaries—however embarrassing they are to read now—that the novelist discovers his true bent—that he can narrate real events and distort them to please himself, describe character, observe other human beings, hypothesize, invent, all the rest.

Belle

By Vilma Howard

Issue no. 8 (Spring 1955)

Belle was always running from or after somebody. One time at the Musetta house party she ran from Skeezer all night until Pretty Willie came after her and then she started looking for Skeezer again. But he was mad at her by that time because he didn’t think she should of danced with Pretty Willie in the first place.

When Pretty Willie’d come over, Skeezer told him, “You better not let your wife catch you over here fooling around.”

But Pretty Willie said, “Aw, she told me I could dance with Belle.”

So Belle danced with him anyway because he was a good dancer before he got married. And then he had to start carrying on.

Ode to Tanaquil Leclerc

By Frank O’Hara

Issue no. 49 (Summer 1970)

Smiling through my own memories of painful excitement

your wide eyes stare

…….and narrow like a lost forest of childhood stolen from

…….gypsies

two eyes that are the sunset of

…….…….…….…….…….…….………two knees

…….…….…….…….…….…….……………………..two wrists

…….…….…….…….…….…….…….…….…….…….…….…….two minds

and the extended philosophical column …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers