The Paris Review's Blog, page 189

January 14, 2020

Redux: Even Forests Engage in a Form of Family Planning

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Deborah Eisenberg.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re trying to separate the forest from the trees. Read on for Deborah Eisenberg’s Art of Fiction interview, Gisela Elsner’s short story “A Pastoral,” and Mónica de la Torre’s poem “Boxed In.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And don’t forget to listen to Season 2 of The Paris Review Podcast.

Deborah Eisenberg, The Art of Fiction No. 218

Issue no. 204 (Spring 2013)

I find it endlessly interesting, endlessly funny, the fact that we’re rather arbitrarily divided up into these discrete humans and that your physical self, your physical attributes, your moment of history and the place where you were born determine who you are as much as all that indefinable stuff that’s inside of you. It seems so ridiculous. Why can’t I just buckle on my sword and leap on my horse and go charging through the forests?

A Pastoral

By Gisela Elsner

Issue no. 34 (Spring–Summer 1965)

My mother shook herself and scratched herself. We walked along a narrow path, through meadows with yellow flowers alternating with fields, perhaps wheat fields.

“There,” said my father, pointing his stick horizontally away from himself at a second forest that looked like the first, which I had taken for a fir or a pine forest or an evergreen forest of some other kind, “there we can rest.”

Boxed In

By Mónica de la Torre

Issue no. 224 (Spring 2018)

Heads up, false friends use familiarity as camouflage.

In the source language deciduous might be confused with apathy,

but nothing could be further away from desidia than the timed impermanence of leaves.

Yes, even forests engage in a form of family planning …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

Promiscuity Is a Virtue: An Interview with Garth Greenwell

I first met Garth Greenwell when we were both undergraduates. At that time, Garth had studied music and wrote very beautiful poetry. His native talent with the English language was evident to anyone who met him or saw him speak. His commitment to writing was inspirational; even as a young student, he lived in a room with two cats and many, many hundreds of books. He could talk about poetry for hours, and everything he said was formulated in eloquent, unpredictable sentences. Twenty years have passed since then, as have many poems, three books of prose, and thousands of miles between us. Garth and I have since crossed paths in Michigan, Washington, DC, New York City, Iowa, Texas, and several times in Sofia, Bulgaria, where he lived for a number of years and where all of his books are set. He still speaks in more beautiful sentences than anyone else I know. There is simply no one like him, no one so able to give musical shape to ideas both on a page and in person. His books, the prize-winning novella Mitko, the much-acclaimed novel What Belongs To You, and now the new work, Cleanness, all vibrate with intelligence and passion, and with exquisite control of language.

Garth Greenwell has received the British Book Award for Debut of the Year, was longlisted for the National Book Award, and was a finalist for six other awards, including the PEN/Faulkner Award, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. A New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, What Belongs To You was selected as a best book of 2016 by over fifty publications in nine countries, and is being translated into a dozen languages. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, A Public Space, and VICE, and he has written criticism for The New Yorker, the London Review of Books, and the New York Times Book Review, among others. He lives in Iowa City. When we conducted this conversation, Garth was in Iowa and I was in Atlanta, so the following took place over email.

INTERVIEWER

As I was reading Cleanness, I couldn’t help but think of lines from Louise Gluck. “I thought / that pain meant / I was not loved. / It meant I loved.” I thought also of Catullus’s famous line: “I hate and love.” Your work captures this tension with enviable clarity and precision. Can you speak a little bit about this?

GREENWELL

The whole point of art, for me, is to give us tools to explore feelings or situations or dilemmas that defeat our other ways of making meaning. When a situation is so vertiginous, so ethically complex, so emotionally fraught, that I feel like I’m staring into an abyss—that’s when I feel moved to make art, when I feel I need the peculiar tools of fiction to figure out what I think. I mean, to inhabit my bewilderment. I think art is the realm in which we can give full rein to the ambiguity, uncertainty, and doubt that we often feel we have to suppress in other kinds of expression—in our political speech, say. I think an ability to dwell in ambiguity, uncertainty, and doubt is a central virtue of humanness. I think it’s crucial to any thinking that might adequately capture the complexity of reality.

INTERVIEWER

Between is the word reviewers of your work mention most often. Your work is described as mapping the territory between vulnerability and sustainability, between love and alienation, between desire and shame, between passion and confusion. Where do you locate this “between”?

GREENWELL

The “Ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds,” Stevens calls for at the end of “Idea of Order at Key West” have always seemed to me like a goal of art. I’m drawn to art that expands and multiplies complexity, art that seeks ever finer gradations of feeling and thought. When do we ever feel a single feeling, or for long? When are we ever wholehearted? How long can we stay in a single place, or stay there happily? Between-ness is the human condition, it seems to me. Certainly itinerancy has characterized my life. Between-ness is also the condition of art. We love to draw lines and borders. Desire and art-making are border-crossing impulses. Promiscuity—an eagerness for mixture, excitement at the new things arrived at through unexpected encounters—is one of the virtues I most admire in thinking, in art-making, in life.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if you could also speak about the book’s existence between Europe and the U.S.? I mean this about both the physical location—you have spent many years in Bulgaria—and also in terms of literary influences—James, Mann, Sebald, among others, are an influence on your work, and yet your writing is unmistakably American. Do you see Cleanness as a European book or an American one? Do these distinctions even exist for you?

GREENWELL

I don’t know how much these distinctions exist for me. Certainly I think the conversation of art doesn’t care about them very much. I’ve always been turned off by a kind of assertive Americanism, and the American writers I love best, from Hawthorne and James and Baldwin to Alexander Chee and Yiyun Li, have all been cosmopolitan in their tastes and views. Of course, America is important to my writing—the landscape of the American South, the rhythms of American speech, the expansive, sometimes-redemptive, sometimes-toxic sense of American selfhood. What it means to be American is one of the subjects of my books, as it is of any book about Americans abroad. Bulgaria is important to the books, too. I was speaking Bulgarian every day as I wrote What Belongs to You. Often enough, I spoke only Bulgarian. The rhythms of Bulgarian—the most beautiful, the most musical language in the world, so far as I’m concerned—are part of those sentences, as is the cityscape of Mladost, the quarter of Sofia where I lived, which I also think is very beautiful, though maybe with a difficult kind of beauty.

Again, for me the great human virtue is promiscuity, the fact that we love mixture, that we are excited by collisions between cultures, languages, traditions. This is why I’m so disgusted by the rejection of this virtue by nationalists of various stripes—and also why I’m resistant to “stay in your lane” condemnations of “cultural appropriation.” Of course, encounters with the other are fraught with peril and—like any ethically meaningful human endeavor—inherently “problematic.” Of course, we need to be mindful and reverent as we attempt to reach across borders of various kinds. But any attempt to build walls—between bodies, between cultural traditions, between languages and aesthetics—is abhorrent to me.

INTERVIEWER

The characters in Cleanness experience suffering. And yet, “Frog King,” at the very center of the book, is a story that opens up the possibility of profound happiness. When asked about that elsewhere, you responded, “To a certain kind of temperament—my temperament, I guess—the assumption that happiness is less interesting than suffering (“happy families are all alike,” etc.) and therefore a less worthy subject for art, seems natural, self-evident. But I think that assumption is wrong. It’s an aesthetic failing but also a moral one, it seems to me now, to see happiness, even very ordinary happiness, as somehow less profound, variegated, interesting, less accommodating of insight, than other kinds of experience. I worry sometimes, in contemporary fiction, that we assume trauma is the most interesting story we have to tell.” I love that answer, and wonder if you could expand a bit?

GREEENWELL

Well, one of the differences between the books is that I hope Cleanness is better. What Belongs to You was my first attempt to write fiction, and I do think Cleanness does things I couldn’t have managed in the first book. Its canvas is broader. There are many more characters, many more settings. And yes, I hope that there are many more emotional notes. We all have our particular temperaments—they aren’t things we can justify or defend—and mine tends to a tragic view of life. My tendency is to feel profundity and resonance most immediately in melancholy things. But I want the art I make to be bigger than my temperament, and it is among my central beliefs that any human experience, any human feeling, is profound when we explore it with the right tools.

When it comes to “The Frog King,” there was also a kind of existential imperative. I love the characters at the heart of the book, and the book is often quite hard on them, and I wanted to give them a kind of idyll. I wanted to allow them a less complicated happiness than they get in the rest of the book. I found that chapter incredibly hard to write, and weirdly devastating. It’s the lesson of Keats’s “Ode on Melancholy,” I guess—if you want to be heartbroken, take happiness as your theme.

INTERVIEWER

One way in which Cleanness is a departure from your previous work is its frank and candid depiction of sexual intimacy. You said, in another interview, that “sex is one of our most charged forms of communication, and that makes it a unique opportunity for a writer. One thing that interests me is expanding charged moments and dissecting their emotional intricacies; in that way, sex is a kind of provocation, a challenge.” You also said, “Sex is inextricable from philosophy. It is a source of all of our metaphysics. It’s the experience that puts us most in our animal bodies, and yet also gives us our most intense intimations of something beyond those bodies.” Might you speak a bit more on this, specifically as it applies to Cleanness?

GREENWELL

The prejudice against writing sex in Anglo-American literature is something that utterly baffles me. What a bizarre thing it is to claim that this central, profound territory of human life is off-limits to literary or artistic representation. Sex seems to me one of the densest and most intense human phenomena, one of the things I find it hardest to think about—and so something I want to think about in art. The biggest surprise to me about the reception of my first book—other than the fact of there being any reception at all—was how much discussion there was about the sex in it. There isn’t very much sex in it! It said something about the culture of mainstream publishing in America in 2016 that a novel with maybe three or four pages of explicit sex between men could seem surprising.

In Cleanness, I wanted to think about sex much more deeply—as a form of sociality, as an excavation of the self, as an attempt to engage ethically with the other, an attempt that often fails. I wanted to try to get to the bottom of the abyss desire is for me. Of course, one never gets to the bottom of an abyss, an abyss has no bottom—but I had the experience, especially writing “Gospodar” and its companion chapter, “The Little Saint,” of going far enough I was afraid I wouldn’t find my way back. I think sex and desire are great revelations, often but not always comfortless revelations, of our ethical capacities and limitations, of our porousness to elements of culture we might want to inoculate ourselves against. I wanted to write them in all their changes, as modes of sustained intimacy, as modes of encountering strangers, as modes of power and submission. I wanted to think about the way that sex and desire lead us to precipices of various kinds. Sex can go terribly wrong, and the book does explore sex as trauma. But it can also go surprisingly, even miraculously right, and I hope the book also explores how sex can be reparative, maybe even redemptive. How it can expose us to experiences of overwhelming joy.

INTERVIEWER

“Cleanness” is the title of a fourteenth-century Middle English alliterative poem by an unknown author. In that text, “cleanness” has a religious or metaphysical quality. Your Cleanness mentions the word itself only once. Your narrator says, “Sex had never been joyful for me before, or almost never, it had always been fraught with shame and anxiety and fear, all of which vanished at the sight of his smile, simply vanished, it poured a kind of cleanness over everything we did.” Can you say more on what this word means for you?

GREENWELL

No concept is more alluring, more potentially inspiring, or more dangerous than cleanness. I wanted to think about the different ways we use ideas of cleanness and filth, how we apply them to geographies, to desires, to bodies, in ways that confuse the physical and the metaphysical. “Are you clean?” on gay cruising apps, is a question about HIV status. The poem you reference is a retelling of several Bible stories, including the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, which is the nightmare version of the cleanness that rage for purity leads us to. That rage is always a response, I think, to the fear many people feel in the face of the desire we feel for filth. One of the journeys my narrator is on is an attempt to shape a life that accommodates both urges, that acknowledges and makes room for his competing desires for purity and for filth.

INTERVIEWER

I hope we can speak a bit more about content and form. Speaking elsewhere about the new book, you say, “Desire is the great inciting incident of plot, because it’s an impulse that engages our wills … Desire is something that happens to us, something before which we’re prone; it defeats our will and disrupts all our intentions.” Can you expand?

GREENWELL

I think that’s true about desire as a narrative device, that it’s almost uniquely interesting in the way that it at once takes our will from us—we don’t get to choose what turns us on—and itself becomes our will—we’ll go to great lengths to satisfy our desire. That’s true of the desire that motivates art as well. We make many choices as we make art, some of them agonizing, but we don’t get to choose what moves us, what we feel compelled to make.

I hope that both of my books explore desire not just in their content but in their construction and their style. I think this is true at the level of how the books are put together, the way their form pushes against linear plot, striving to inhabit a kind of lyric or queer time. But I feel it most intensely at the level of the sentence. The kind of sentence I’m drawn to, which constantly falls back on itself in correction or hesitation or defeat but is also drawn forward by the demands of rhythm and cadence, feels mimetic of desire to me, even of sex. It also feels mimetic of thinking, or of the kind of libidinal thinking that happens in my writing. I don’t feel that sentences are containers for thoughts that precede them. The sentences, the pressure of syntax, the pleasures and possibilities of rhythm and cadence, produce the thought. In that way, form and content are inextricable.

INTERVIEWER

Your work has always been innovative in scope. You have published in various different genres, from poetry to literary criticism to short stories, a novella, novels. Your work has also been shape-shifting—what one might think of as a novella, Mitko, becomes a novel right in front of our eyes in What Belongs to You. What one might first assume is a collection of short stories—Cleanness— morphs into something else entirely. How did that happen?

GREENWELL

None of this—the shifts from poetry to prose, the fact that the novella grew into something larger—was planned. I wish I were disciplined and confident enough to plan out a career and then embody my plan, like Zola did—or, well, maybe I don’t wish that at all. I like artists whose works feel at once monumental and contingent, hesitating, accommodating of error and accident. The various versions of Leaves of Grass, James’s revisions, Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet. Not a thought, but a mind thinking. Art as object, but also art as action. The ideal is an object that still has the vibrancy, the dynamism, of the action.

INTERVIEWER

Do you see Cleanness as a sequel to What Belongs to You, as a story told by the same narrator, in the same location? And, if so, will there be a trilogy?

GREENWELL

I don’t think of Cleanness as a sequel to What Belongs to You. The books intermingle—their temporalities and characters overlap, but they also are autonomous, I hope. The first two or three pieces of what would become Cleanness were written while I was writing What Belongs to You, and I did have a sense of the projects as continuous. But they each had their own imperatives. It was clear that the first book would be very narrowly focused on the obsessive relationship at its heart. Cleanness is more ample. It lets in more of the world. My next book will be set in America, not Bulgaria, but it will intermingle with the first two in a similar way. I’m drawn to writers whose books feel at once like well-wrought, autonomous objects, and like a single, unfolding project. I don’t know what I will want to write in ten years, but right now, the idea of books that are both individual and porous is something that excites me.

INTERVIEWER

I began this conversation with a few lines of poetry, so I would like to end it on poetry. When I first met you, you wrote and spoke only about poetry. I was worried you might abandon this engagement, but you have clearly continued the conversation. You recently published a beautiful interview with Frank Bidart in The Paris Review. What do you continue to get from poetry that you might or might not get from literary fiction?

GREENWELL

For better and for worse, everything I do as a fiction writer is a result of having spent decades as a poet. Even though I haven’t written poetry in several years, poetry is still central to my life, and I still think of myself more naturally as a poet than as a novelist. I read poems every day. I still write a great deal about poetry. I teach poetry whenever I teach a fiction workshop. When I wrote poetry, I often felt as though I were sculpting language out of silence, trying to divorce words from their necessary relationship to time. Frank Bidart says this in one of his poems, that the goal is to nail something “outside time.” Writing prose, I feel language very much in time—the unit is the phrase or sentence, very seldom the individual word. The interrelation of syntax with time feels generative, a blessing. But I like feeling poetry ready to hand. I like feeling that it is possible to suspend the horizontal movement of prose and reach along the vertical axis of the lyric. Maybe that movement, from horizontal to vertical, from narrative to lyric, is one of the characteristic movements of my fiction, or maybe—I guess this feels more true to me—I’m trying to strike some quixotic, impossible middle ground between them.

I worry about the way that, for American writers, our reading and our identifications seem to be becoming more insular. Many of the fiction writers I know don’t read poetry. Almost none of the American writers I know read in other languages—few of them read widely even in translation. That seems a little tragic to me, and doesn’t bode well for the health of American literature. As an artist, I want to be curious, voracious, promiscuous—to use that word again. I want my sense of what art can do to be enlarged. To do that means turning away from the familiar—our familiar genres, our familiar languages, our familiar locales—toward experiences that challenge us and, especially, that make us question the orientation we’ve adopted toward the world. That turning toward the unfamiliar is something that desire encourages us to dare to do, I think. The writer in America has been professionalized to a perilous extent. I don’t think great art is likely to be made by professionals. I think it’s more likely to be impeded by the demands and values of professionalization. The ideal development of the artist is libidinal, I think, spurred not by the demands of the academy or the world of professional publishing, but by the imperatives of desire, by seeking out complicated pleasures.

Read Garth Greenwell’s “Godospar,” which appears as a chapter in Cleanness, in our Summer 2014 issue, and his Art of Fiction interview with Frank Bidart in our Summer 2019 issue.

Ilya Kaminsky is the author of Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press) and Dancing In Odessa (Tupelo Press). His awards include the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Whiting Writer’s Award, the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Metcalf Award, Lannan Foundation’s Fellowship and the NEA Fellowship. His poems regularly appear in Best American Poetry and Pushcart Prize anthologies. Read his poem “From ‘Last Will and Testament’” in our Winter 2018 issue.

January 13, 2020

We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Die

On the fortieth anniversary of Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping: an unbeliever’s rereading of Christian conceptions of the afterlife.

Still from Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger (2013)

I took one English class in college. The theme was contemporary fiction and, dutifully enough, we read DeLillo, Nabokov, Zadie Smith, Beckett, Coetzee, and—this last author was not like the others—Marilynne Robinson, whose novel Housekeeping appeared midsemester like a kind of anachronism. It was markedly domestic, reserved, inflected with lyricism, not self-serious but definitely sincere in its wonderment. At its first appearance, in 1980, spellbound reviewers praised its humble poetry, its interest in the ephemeral, the fidelity to small-town life.

Housekeeping, now nearing its fortieth anniversary, has returned to me throughout my writing career. Like those enraptured critics, in my first encounters I read for language, for voice, for craft. I loved this book. In graduate school, in a seminar on the literature of travel and trains, my professor recited the opening line to the class with a kind of disgusted glee: “My name is Ruth.” What kind of beginning was this? How had such an otherwise beautifully written book gotten away with it? The declaration—harsh, direct—is perhaps more shocking in the context of the rest of the novel, which proceeds with the gentle indifference of understatement. That opening chapter describes a mass drowning as no more upsetting than an exploratory dive: a train “nosed” into a lake, Ruth tells us, as calmly as a “weasel,” claiming all the passengers within as the water “sealed itself” over their souls. The scene is so soft, so seductive, it may as well have been narrated by a ghost. I remember we spent the remaining hour of that class discussing whether drowning truly was the most romantic way to die. I wonder now if perhaps parting from one’s body becomes more appallingly beautiful when alibied by the suggestion of an afterlife.

Housekeeping was unique among major anglophone novels of the eighties and nineties, a counterpoint to the anxiety and irony of hysterical realism. But it has also proved an outlier in Robinson’s own, formidable oeuvre; unlike her subsequent essay collections and novels, it has not been enshrined as an explicit exploration of her Calvinist faith. It is “about people who have not managed to connect with a place, a purpose, a routine or another person,” wrote the New York Times in 1981. But the detachment goes much deeper than a failure to connect. Certainly Housekeeping “is not about housekeeping at all,” but it is about the “light work” we do to stay alive, on earth, as we wait to join the world beyond. I see now that it is about waiting to die, and embracing death as a return. “Ascension,” Ruth says, “seemed at such times a natural law.” At the heart of the novel lies an unmistakable preoccupation with Christian conceptions of the afterlife.

I myself am uncomfortable about death. I don’t know where to put it. At age nine, I almost died in the kind of freak accident that Housekeeping’s lyricism so gorgeously blunts, an experience that has had a subtle but profound influence on my life ever since. Perhaps I ought to have flinched from a book that muffles the raw mechanics of a death, having once been within hearing range myself. But in fact it is easy to dissociate from that close call. My own accident doesn’t seem like something that happened to me. The memory, like that opening chapter, is muted, a scene overheard a long time ago. I spent weeks recovering in the ICU attached to the university where my parents taught and worked. The blinds were always drawn, and patients tended to slip in and out of consciousness—it was hard to tell if it was day or night, metaphor or real life. Like the characters in Housekeeping, we existed somewhere in between. Perhaps this is why I first loved the book, for the way it made a seduction out of dying. However, I didn’t register its explicit fascination with liminality—its orientation toward death—in my first reads. And now that I do, I question it.

The year after my accident, a fourth-grade classmate was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. This, to me, is the more violent memory. I sat next to him in math. I watched him lose his hair, his composure, his ability to perform simple calculations. He had tantrums over his homework sheets, slamming his fists on the desk. It was a tantrum against the enormity of all that his own body was taking from him—there was no metaphoric potential in this. Then, one day, he gave up. And there, in the giving up, the stories and imagery began. Before he died, he sat beneath a night sky with his mother and pointed into the stars. Will I go there? he asked. She answered the only way a Christian mother can: Yes.

I write novels for a partial living. It should be no terrible leap of the imagination to believe: a little boy finally at peace among the stars. I suspect Marilynne Robinson is able to lean into this scene. But I’m afraid I can’t.

*

Today, while I still admire Housekeeping, I find its impulse toward the Christian afterlife makes me uneasy—unreasonably uneasy. I do not mean that my sensibilities exist at cross-purposes with the politics of the middle of the country, as the stereotype so often goes. I am from the middle country, from towns not unlike the Idahoan village of Fingerbone in which Housekeeping takes place, a town “chastened …by an awareness that the whole of human history had occurred elsewhere.” I mean instead that I have experienced a sort of spiritual gridlock with the kind of person who holds certain ideas about the afterlife, and who might claim jurisdiction over a stranger’s soul; the kind of person who might divulge the unsolicited opinion that you, an unbeliever, are destined for Hell. The implicit corollary to Ruth’s fascination with ascension is, for me, the promise of descension, however hysterical this may seem.

Housekeeping’s relationship to Final Judgement is quieter, more polite, than the evangelic fervor I grew up around—it makes a lullaby of Armageddon. Even still, Fingerbone is brimming, quite literally, with apocalyptic imagery; the lake floods the town once a year, bestowing all its baptismal and destructive promise. The novel opens with the dashed-off deaths and departures of the better part of Ruth’s family—a mother, grandfather, grandmother, and two great-aunts all disappear, more than a few of them to the depths of that lake, a domino effect that leaves the orphaned Ruth and her sister, Lucille, in the care of Sylvie, the whimsical aunt who eventually comes to raise them. “Time that had not come yet,” Ruth says of her most recent guardian, “had the fiercest reality for her.” The year Sylvie arrives, the annual flood is so totalizing that “if we looked at it, the water seemed spread over half the world.” Ruth wonders, “Why must we be left, the survivors picking among the flotsam, among the small, unnoticed, unvalued clutter … that only catastrophe made notable? Darkness is the only solvent.” She longs to dissolve into that darkness, too, to “let the darkness in the sky become coextensive with the darkness in my skull and bowels and bones.” It’s an appealing metaphor. If the afterlife had been presented to me as a kind of dissolution, perhaps by now I, like Robinson, would be a devout and open Calvinist.

I came about my uneasiness with Christian theology of the afterlife as honestly as one can. My parents, themselves raised Catholic, did not baptize me; my father objected to the involuntary nature of the rite; my mother wanted “nothing to do” with an institution that denied the use of birth control and same-sex marriage rights. My mother’s extended family is Jewish (my aunt converted when she married), but they live across the country, and so I was raised without any formal religious education at all, and certainly without the prospect of damnation. At best, faith floated through my life on holidays, and even then in only performatively secular ways. One Christmukkah, after my mother accidentally swapped the salt and the sugar in my cousin’s kitchen, both in jars labeled in Hebrew, we sank our forks into saline apple streusel with a groan.

I do not remember encountering any resistance to my heathenism until we moved from the Adirondacks, where I was born, to Burlington, Vermont, where, as fate would have it, I attended a Catholic school. My parents had chosen it for its proximity to the university where they were employed in research laboratories, and for that fact that no other elementary school in the area offered after-school care past five. (Since both my parents worked, we were reliant on these so-called after-school programs.) They took turns walking me to and from class at the bookends of a day. The school, not especially rigid in its catechism, was interfaith, but I was notably religiously illiterate, and my ignorance made of me the most offensive student in the class by far. For the third-grade poetry competition, I tied for first place but was barred from performing at the assembly after my submission was deemed too blasphemous to be shared before the nuns. My friend Katharine read aloud, and alone, a nuanced verse about practicing Judaism in a Catholic school; for my part, I’d appropriated the rhyme and meter of the Hail Mary for a propagandistic ditty promoting shorter school years and extended recess periods. It was also Katharine who warned me, later in the year, that, like her, I was not allowed to follow our classmates through the pews for first confession, baptism being a prerequisite—indeed, the priest expelled me from the booth, along with the notecard of sins I’d prepared. My science teacher was a nun who once asked us each to state before the class our favorite of the eight Beatitudes. I responded to this invitation with the announcement that God helps those who help themselves. It seemed a fitting and wrathful punishment, a month later, that my terrarium was the only one to grow mold and die. But overall, aside from the occasional suggestion of divine intervention, religion remained adjacent to my experience, something to which I did not and was not expected to belong. I didn’t quite respect it, perhaps in part because I wasn’t yet afraid. For all the time I spent in Catholic school, no one had yet impressed upon me the fact that I was bound for Hell.

When I was ten, my family moved from Vermont to Indiana, where all our neighbors were believers and pushier about their faith. That first summer, the heat was a shock—I spent June playing tennis against myself inside the shuttered garage. One afternoon, I ventured out into the street, where I met two kids riding bikes. I had never encountered evangelists before, which is to say I didn’t know how to read the subtext of a casual invitation: when they asked me over I responded with an only child’s desperate yes. I realized the gravity of my mistake when I arrived at a homeschool Bible study, where the pastor awarded my hosts with plastic toys as a reward for luring me to their living room. I was an impish, arrogant kid, and so I immediately divulged that I was not baptized, assuming this would release me from the lesson, just as the priest had once evicted me from confession. Rest assured the effect on the pastor was quite the opposite. I remember he had picture books depicting graphic, Dantean scenes. He held them aloft as he narrated the images therein, further animating suffering. He made frequent eye contact. I remember he seemed to speak specifically to me.

The promise of the afterlife—and, in my case, the promise of damnation to Hell—became a specter of my adolescence. My fate was brimstone, and I was fascinated and afraid. I asked everyone I knew: Did they truly believe I would go to Hell? I nagged my born-again babysitter over midday meals at Wendy’s or Pizza Hut. I trusted her—this was the woman who’d taught me milkshakes are better when you use them as a dipping sauce for fries. Now she was assuring me God had an umbrella over children, which only led to further questions about diameter, circumference, and at what age one officially left childhood behind. I must have been, as the euphemism goes, a test of faith for her.

Everywhere, ideas of salvation seemed to erect a screen between me and the people I loved; it was as if they’d already died and moved into another realm. There were girls in my classes with whom, through all four years of high school, I never had a conversation about anything other than the assignment for AP Lit; they were members of the Right to Life Club and I was not. I was half in love with a family friend—she was a few years older than I, she drove me to school, did psychedelics, played guitar (of course!)—who returned home from a year of college in Iowa transformed. She perched in my kitchen with an electric, apocalyptic glow: Jesus will reign among us for a thousand years, she said. I spent my lunch periods that year with another friend, scheming over how to join the ranks of Reform Judaism: he because he was gay, and I because I was still too proud to cow to the fear of Hell. Years later, when my Hindu partner and I began to joke about having children in the way couples do, he paused, looked at me. You’re not going to want to baptize them, are you? I felt a profound recognition for the panic on his face. All my life, there had seemed to me something inexcusably aggressive in the act of “saving” someone else. It stole people from themselves. Like a deep lake, it swallowed them whole and sealed over their souls.

*

Growing up, I sometimes felt around believers the way the orphaned sisters in Housekeeping feel about their itinerant aunt. In one sense, Sylvie is a dream mother, a Wendy out of Peter Pan: she serves baked apples for dinner, buys flimsy glitter shoes and ribbons, fails to enforce a bedtime or notice that the girls have been skipping school—to be so out of touch with consensus is the very source of her charm. But as the novelty of neglect begins to wears off, Lucille and Ruth become resentful that Sylvie is no better than a child when it comes to keeping house, which is to say the basic business of survival. Lucille demands a change. Why doesn’t Sylvie buy real clothes, eat real food? Why doesn’t she act like someone who wants to stay put, stay alive? There’s something incurably transient about Sylvie, something restless and erratic, as though she were a compass drawn to an alien and undiscovered pole. One day, when the girls are playing truant, they find Sylvie balancing unsteadily on the railroad bridge some fifty feet over the surface of the lake—the same bridge the train “nosed” over in the opening—looking as if she’s considering leaping in. When she notices the girls, she nonchalantly waves and returns to shore. Lucille requires an explanation:

“What if you fell in?”

“Oh,” Sylvie said, “I was pretty careful.”

“If you fell in, everyone would think you did it on purpose,” Lucille said, “even us.”

Sylvie reflected a moment. “I suppose that’s true.” She glanced down at Lucille’s face. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“I know.”

“I thought you would be in school.”

“We didn’t go to school this week.”

“But you see, I didn’t know that. It never crossed my mind that you’d be here.” Sylvie’s voice was gentle, and she touched Lucille’s hair.

The frustrated logic of this exchange recalls the conversations I used to have with believers. The afternoon I found myself hoodwinked into attending Bible study at the evangelists’ house, I followed the brother and sister down the street connecting our two neighborhoods, trading little facts about our lives. I was a runner, I told them, and very good, to the detriment of everything else—I lacked hand-eye coordination and any intuition at all for team sports. The sister, who was my age, pondered this for a minute. “God didn’t make me out to be a runner,” she said, almost defensively. “He made me a swimmer.” This statement was profoundly perplexing to me. As was my babysitter’s unliturgical claim that God had an umbrella over children, a proposition that implied adults who did not get themselves saved would be damned to Hell. Both of these deterministic outlooks seemed avoidable to me; one could learn to run, could practice and improve. One could pick and choose from ideology, retaining a faith in charity while skipping over the idea that fellow human beings will burn eternally. At age twelve, it seemed to me that we talked past and around one another, avoiding the articulation of something terrible—my own damnation—in the same way Lucille and Sylvie talk around the possibility of Sylvie’s suicide. Only one party acknowledges how avoidable is all this harm; it would be so easy not to leap from the bridge, not to wander into that death trap at all. At the same time, Sylvie’s motive is innocently transparent, blamelessly cruel, and undeniably attractive; she casts a spell. You cannot reason with a mother like this, just as you cannot reason through a belief in God. Like Lucille, as a child I was at first hurt, then angry, that believers could not put their affection for me before a conviction in the Second Coming and the inevitability of Hell.

Distant, distracted, eschewing company, terrible at keeping house, in some ways Sylvie recalls a writer deeply absorbed in the making of a book. “Step out of it,” my partner gently chides, when he finds me deep in the throes of despair over some problem in a story, unable to communicate about anything else. Like a fixation on the world beyond, reading or writing novels draws one into another realm in a way that competes with existing in this one; it requires a kind of conviction in another world. As an adult, I’ve found writing fiction to be solitary-making and brain-addling, tending to siphon away all common sense: you put your sweatshirt on inside out (even upside down), miss appointments, leave your keys in the fridge, forget people cannot hear you nodding on the phone. To have faith, maybe, is to adopt a profound obsession with a clandestine realm that rivals the world—it’s difficult, I hear, to be a mother and a novelist. Perhaps these resonances between faith in the afterlife and faith in literature should establish common ground. But while readers may become evangelical about books—indeed, Housekeeping is one such novel—a passion for literature, unlike a passion for Jesus, tends to stop short of proclamations on the eternal fate of others’ souls. To have faith in Christian conceptions of the afterlife is to believe in a story, sure, but one that projects itself not onto other worlds but onto this one, where it demands to be received as universal truth.

In some ways, I admire this certainty about other people’s souls. There have been times in my life when I’ve suspected that, like Sylvie, I lack appropriate conviction and interest in daily life or human affairs. Strong conviction—on even minor topics: whether to dip fries in milkshakes, the source of one’s talent for swimming butterfly—carries for me a profound charm. I dislike uncertainty as much as anyone, and so it is refreshing to bask in the glow of sureties and stable predicates: I am a writer, I’m a mother, I’m a wife, I’m a Christian; I am a swimmer, because God made me so. But these narratives also carry a hint of deception, precisely because they are presumed to be immutable. In my experience, we are erratic, self-ignorant, constantly shifting beings. We presume stability in our beliefs, and about our compendium of predicates, not because this stability is true or justified but in order to allow a day to take shape; noon morphs around the falsehood of fixity. In other words, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” But this idea is too often invoked as a kind of celebration and rehabilitation of literature, rather than as a simple statement of fact. In the flotsam of social media, it suggests that narrative is a call to self-absolution and confession, rather than a deluded attempt, as implied by Didion’s original context, “to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” What was meant to be a diagnosis has been mistaken for a cure.

To freeze life in stable narrative—to suspend the Brownian motion of human behavior so that we may better understand what is going on—is to lay grounds for delusion. We delude ourselves in order to live. I believe the novelist’s vocation is to cast illusions, not delusions, and that there is a great difference between these two necessary spells. It is the novel’s prerogative to trap experience in the form of a book, but never in such a way that it ceases to morph and shift within the boundaries of its container. The illusion of stability—of “freezing” life—exists precisely to throw uncertainty and ambiguity into greater relief. This is the difference, for me, between the stories we tell ourselves to organize a day and the stories we tell to induce a literary experience. Religion belongs to the former category, while religious texts themselves—including a novel like Housekeeping—belong to the arts.

It smacks of condescension to call religion a delusion. That’s not quite what I want to say. But what I mean is perhaps even more offensive: that in fact religion is literature—is metaphor—and that I am able to worship only up to that point where its figurations become literal, become delusions, become claims about damnation and ascension. “So this is all death is,” Ruth thinks as she falls sleep in a quilt wrapped “warm and soft around my arms and shoulders and my ears.” I am uncomfortable about Housekeeping’s coziness with the afterlife because I cannot separate it from the echoes of those who would confuse literature with a dogma of the soul: We tell ourselves stories in order to die.

*

What is the religion I grew up around but a story about how to part from ourselves and from one another? As a child, I never realized that these stories are all the more important for those left behind. After I was released from the ICU, I learned that while I had been away, the entirety of my Catholic elementary school had gathered in the same gymnasium where I had once been barred from reading my poem to hold a prayer service in my honor. I was vaguely horrified by the idea. I did not want my classmates to know anything about me, did not want them to consider me a freak. When people told me they’d prayed for me, I offered a blank stare. Their appeals to God, I thought, were presumptuous and invasive. This now seems to me misguided, the product of a child’s perceived immortality: I wouldn’t really have rather died alone, I don’t think, with no one to pray for me.

It also never occurred to me, at nine, to wonder how my parents had survived my accident. Where did they turn for comfort as I was wheeled in and out of the OR? Today, when I think of them waiting for me to recover, I am troubled to find that I have no more to offer them now than I did then. No tales about rising to join the stars. No delusions at all. Of course I don’t—in that story, where they are in need of more potent narratives, I’m already gone.

Science, Robinson writes in her most recent essay collection, The Givenness of Things, has offered “the greatest proof of its legitimacy” in having “found its way to its own limits.” It is the kind of Trojan-horse claim that I recognize from my childhood, the kind that puts me reflexively on guard. But there is value in acknowledging the boundaries of any faith, and perhaps my own secularism reaches its limits at the limit of a life. I can imagine a believer addressing me in the same tone in which Lucille addresses Sylvie: Why not simply believe? There is no reason to stroll along the railroad tracks and peer down into the water, terrified, no reason not to accept Jesus into my heart. In return, he will allow me to ascend. But I have never found my way in through that open door. What remains beautiful, to me, in Housekeeping is not that death might be gentle, but that Ruth and Sylvie’s longing is so profound: “When do our senses know anything so utterly as when we lack it?” Ruth says. Her conviction throws my own utter lack thereof into relief. She believes that “to crave and to have are as alike as a thing and its shadow … to wish for a hand on one’s hair is all but to feel it.” When I wish for a hand, I feel its absence.

But I have known smaller comforts. After my classmate’s death, after the tumor sank its deep roots through his brain, his funeral mass was held in a cathedral on the far side of town, near the woods. The stained glass behind the pulpit rose in vibrant purples, and the coffin lay open before the pews. My father has often reminded me of the extraordinary thing that happened next: as the priest prepared communion, a deer appeared in one of the low windows at the back of the church and lingered, looking in at the congregation with its wide, wet eyes. The way my father tells it, the doe must have stood there for five or ten minutes, until the end of the service, before leaping away into the woods. He tells it with an air of disbelief, but also reverence—it seemed to him a sign of something approaching the divine. I never saw the deer, or if I did, I don’t recall.

My father has always been a storyteller, the liturgist of family legend. I can see him telling this particular tale at the pulpit of the kitchen table, his arms wide for emphasis, his face alive with boyish wonder. And for whose benefit, that wonder? He used to keep me entertained like this for hours in the car, spinning elaborate yarns he’d invented just for me. Fairy tales. Meandering jokes. He told stories about Detroit, my great-uncles, my grandfather’s penchant for pickled pig knuckles and an antiquated Polish pegged to nineteenth-century slang—stories that resurrected in the blind spots of my memory all the relatives who’d died. It never occurred to me to question the veracity of these private histories. I have no idea where truth lies. I am still waiting to find out. I ask my friends, my partner. I look over my shoulder, to make sure my parents are still there. When the time comes, I suspect it will no longer matter so much, whether the deer appeared.

Marilynne Robinson’s story “Connie Bronson” appeared in issue no. 100 of The Paris Review. The Art of Fiction no. 198 was published in issue no. 186.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens is a writer and itinerant freelancer. Her debut novel, The Exhibition of Persephone Q, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in March. She has published two stories in The Paris Review, “Honeymoon” and “The Party.”

January 10, 2020

Staff Picks: Sex, Stand-Up, and South Korea

Ha Seong-nan.

There’s something pleasingly matter-of-fact to the many off-kilter moments found in Ha Seong-nan’s short story collection Flowers of Mold (translated from the Korean by Janet Hong). When problems arise for her characters—a potential intruder in a woman’s farmhouse bedroom, a woman’s loss of memory following the arrival of a new neighbor, a group of tenants faced with eviction by a spoiled and wealthy landlord—their approaches to solving them are no-nonsense, even as the stories themselves border the surreal logic of dreams. The tenants hatch a plan to kill their landlord; the woman’s memory loss betrays her own place within her family; the intruder may exist and may be buried in the orchard. Ha lends a critical eye to capitalism, advertising, and gender in contemporary South Korea, and in each story, she combines the ordinary with the extraordinary to truly disquieting effect. —Rhian Sasseen

I know I’m only adding an insignificant note to a swelling chorus when I recommend Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness—it’s already drawn praise from Sheila Heti, Édouard Louis, Carmen Maria Machado, Alexander Chee, Adam Haslett, and, in this same section a few weeks ago, my own colleague Cornelia Channing. But when I finished it, on a plane, where emotions are always more heightened and I am given to dramatic gestures, I clutched it to my chest. I was grateful for this book, as if it had been written for me alone. “I could hear music, Balkan pop, the uneven dreams and pipes, a woman’s voice singing restlessly around them,” the narrator says at one moment. “I couldn’t make out the words but they were always the same: something about love, I thought, something about loss.” The foreignness of Bulgaria—where the narrator is an openly gay American teacher—serves only to remind us that in every place, the song is always the same. Yet in Cleanness, we hear the words in uncannily high definition. Greenwell writes about moments of nuance with unrelenting precision, seeking not to flatten them but to fan them out into an array displaying their every possible shade. His structure reflects that gentle exploration: the sentences revise and layer over themselves, and the sections of the book, each of which could stand alone as its own story, seem to inhale and exhale into one another, as if in waves, drawing the water and sending it out again against the shore. And the sex! Greenwell understands, as so few authors do, that sex is not a single act that takes place in the jump cut before morning but a dialogue worth unfurling across pages, an attempt at communication, achieved or failed, in which our truest selves are revealed. We, and his characters, are altered by it every time. —Nadja Spiegelman

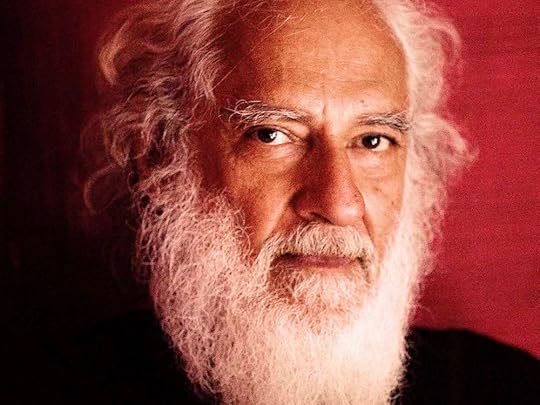

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s poem “The House” finishes like this: “On a railway platform // I saw him last, / Who passes before me / In the cheval glass.” Mehrotra’s poetry nimbly distorts the assumptions a reader might make about speaker and subject; up until this final moment of “The House,” the two are understood as separate. Throughout a recent selection of his work published by NYRB Poets, Mehrotra is both understated and sophisticated, often moving between identities and histories. Amit Chaudhuri writes in an introduction to the collection, “At one point, I’m here, sitting in a chair writing a piece in 2014; at another, I’m Ghalib, receiving letters and poems from friends.” However, you would be misled to think that these are cerebral pieces of philosophy; my favorite thing about Mehrotra’s work is that it is always grounded in the small moments of daily life. His sense of humor is like the shadow of a sideways smile. It’s a quietly forceful collection, one whose spine I’ve already cracked in rereadings. —Lauren Kane

I first met Crissy Van Meter in her role as managing editor for the always astounding Nouvella Books. Since then, she’s founded Five Quarterly and published work in Vice, Bustle, Guernica, and Catapult. Out this week is her debut novel, Creatures, the story of a girl raised by a charismatic drug-dealing father on a fictional island off the Southern California coast. Through a deft handling of temporality and structure, Van Meter traces the emotional wreckage eddying in the wake of that upbringing as her protagonist shifts into adulthood. I am fond of novels that willfully truncate the possibilities—limiting by geography or circumstance and seeing what that does to the narrative—and Van Meter’s book does this with genuine skill, tracing a childhood of nearly literal shipwreck upon a desert island and pushing through to see what such limits do to the human heart. The result is beautiful and moving. —Christian Kiefer

In her new comedy special, The Planet Is Burning, Ilana Glazer is surprisingly nihilistic, her stand-up a frank exploration of the complexities and discomforts of being a woman at the beginning of a new decade. Glazer is best known for her work on Broad City, the recently concluded sitcom that she created with Abbi Jacobson in 2014. In a perfect balance of realism and absurdity, Glazer and Jacobson offered a refreshingly unpolished take on the female-friendship narrative. But after the 2016 election, Broad City took a darker turn, with Glazer’s character openly grappling with depression. The Planet Is Burning allows Glazer to turn even further inward as she examines her own complexities and contradictions in greater depth. In one instant, she embraces her masculine qualities, arguing that she is “sixty to seventy percent female and thirty to forty percent male”; in the next, she admits finding joy in what could be seen as feminine domesticity with her husband. For the second half of the set, Glazer focuses intently on grim and unlikely material, giving a thorough comedic treatment to menstruation and fascism. Yet The Planet Is Burning is something of a celebration. Setting the tone at the top of the show, Glazer takes the stage dancing, clad in her signature cutoffs, her hair styled in exaggerated curls that invariably recall Gilda Radner. And to finish, she nearly embraces optimism. “Women are taking a giant step forward,” she assures her audience. “We are so close to taking it back.” “But,” she concludes in a hurried admission, “I just hope we can do it before the planet bursts into flames.” —Elinor Hitt

Ilana Glazer.

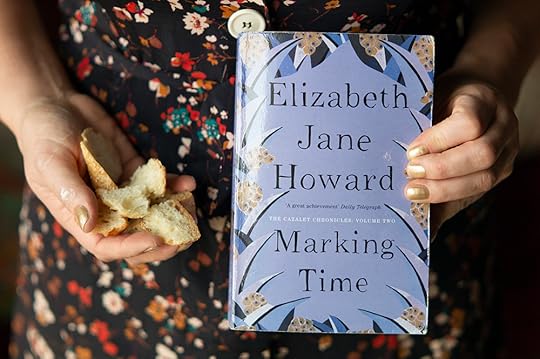

Cooking with Elizabeth Jane Howard

In Valerie Stivers’s Eat Your Words series, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

The old-fashioned matriarch in the Cazalet Chronicles believes in just adding more bread crumbs to the rissoles if there’s not enough food for twenty dinner guests.

The English writer Elizabeth Jane Howard (1923–2014) is best known for the Cazalet Chronicles, a series of family dramas set around World War II that overflow with scenes of meals being prepared for a large English country estate. Published between 1990 and 2013, the books are five floral-covered bricks totaling nearly three thousand pages and centered on the children and grandchildren of a rich English timber merchant, known as “the brigadier,” and his Edwardian wife, “the duchy.” The story concerns the Cazalet family at large as well as their lovers, spouses, children, governesses, great-aunts, cooks, and cousins, all of whose struggles for love, fulfillment, and a place in the world make for page-turning reading.

It was the opinion of Howard’s contemporaries that this was not great literature, and though she hung out in elevated literary circles—most notably as the second wife of Kingsley Amis and the stepmother of Martin Amis—she was often dismissed as a writer of “women’s fiction.” But Howard’s books hold up. She has a dazzling ability to depict a character at a moment of crisis, catching a young woman midstream as she gives up one dream for another or drilling in on a telling lie, a glint of cowardice. It also takes enormous technical virtuosity to keep her huge cast of characters distinct in the reader’s mind, and a master class could be taught from the timing of her interlinked plotlines.

My conversion to the Cazalet Chronicles came midway through the second volume, Marking Time, when Jay, a clever theater student, quotes a poem to one of the heroines, Louise, a moody, damaged young woman who has artistic aspirations in a society on the verge of war (like everyone else, she eventually must give them up for the greater good):

Annie MacDougall went to milk, caught her foot in the heather,

Woke to hear a dance record playing of Old Vienna.

It’s no go your maidenheads, it’s no go your culture,

All we want is a Dunlop tyre and the devil mend the puncture.

…

It’s no go my honey love, it’s no go my poppet,

Work your hands from day to day, the wind will blow the profit.

The glass is falling hour by hour, the glass will fall forever,

But if you break the bloody glass, you won’t hold up the weather.

The poem, Louis MacNeice’s “Bagpipe Music,” captures the sense of social disintegration felt by people in England between the wars, and it brought home to me that the Cazalet Chronicles are a unique, sprawling formal experiment in approaching the loss of a social order, the great theme of Howard’s generation, through a proliferation of stories of relationships, family, love, the domestic, and the home. The approach is necessarily oblique because Howard’s young women experience most of the forces battering their world as sources of mystery and absence. They aren’t told things; they’re sent away when the adults listen to the radio. In one scene, a man on a train forces a teenage girl’s head down as two planes fight overhead and everyone else cheers and claps. Afterward, while the girl seethes with rage, mingled with shock at the realization that she wanted to see what was happening, her mother makes her thank the man. How does one become an adult under such conditions? Howard’s titles are telling. The third volume is Confusion; the last, All Change.

For Howard, the humble sunchoke made a foolproof soup. Would it do so for me?

The Cazalet Chronicles are, to an amazing extent, autobiographical. In Artemis Cooper’s biography Elizabeth Jane Howard: A Dangerous Innocence, we learn that all three of the young female leads are essentially versions of Howard herself, drawing on her life experiences and the different aspects of her character. And the change, turmoil, and confusion that comes through in the novels plagued her extraordinary but tumultuous life. She, too, was a timber merchant’s daughter who spent her younger years on an English country estate. Like her characters, she modeled for Vogue, married young, and had and abandoned a child. And like them, she had many romances, including affairs with the poet Cecil Day-Lewis, the writer and conservationist Robert Aickman, and the anti-totalitarian intellectual Arthur Koestler, as well as her aforementioned marriage to Kingsley Amis, from which she inherited Martin as a stepson (in Martin’s account, far from being a wicked stepmother, Howard set him on the path toward becoming a writer).

The marriage to Kingsley Amis did not last, however, and Howard, a successful author since her twenties, continued to take lovers into her seventies while running her own sprawling country house, where she threw regular weekend parties that were a who’s who of literary London. Unlike their mothers, many of the well-off women of Howard’s generation had to do their own cooking, and she excelled at it, writing a cookbook, making her own marmalades, chutneys, and jams, and, for guests, stuffing her freezer with “stews and fish pies for the weekend, as well as things that don’t freeze quite so well, like game terrines,” Cooper writes.

As a hostess who frequently churns out food for weekend guests, I gloried in these books’ baking scenes, which provide a unique glimpse into the kitchen of a large estate of the era. In one passage in The Light Years, the cook, Mrs. Cripps,

spent the morning plucking and drawing two brace of pheasant for dinner; she also minced the remains of the sirloin of beef for cottage pie, made a Madeira cake, three dozen damson tartlets, two pints of egg custard, two rice puddings, two pints of batter for the kitchen lunch of Toad-in-the-Hole, two lemon meringue pies, and fifteen stuffed baked apples for the dining room lunch. She also oversaw the cooking of mountainous quantities of vegetables—the potatoes for the cottage pie, the cabbage to go with the Toad, the carrots, French beans, spinach and a pair of grotesque marrows.

But when I turned toward making this exciting-sounding food, I discovered how stingy it is. We tend to think of wealth as a monolith and imagine that people in country houses of any era were consuming the cream of the crop. We also—thanks, in part, to The Great British Bake Off—have moved so far from the cliché of English food being terrible that I’d forgotten to expect it. But a reader who is paying attention will notice that one of the first things Howard tells us about the duchy is that she’s an Edwardian who doesn’t believe in taking baths or heating houses or eating toast with butter and jam (it has to be one or the other, or else it’s too decadent). The dishes being turned out in the Cazalets’ kitchen are things like the “cottage pie,” above, and “rissoles”—both to be found in the “leftovers” section of Delia’s Complete Cookery Course (Delia Smith, an English equivalent to Julia Child, was a source Howard used in her personal life). And that’s before the war. During, food becomes even scarcer. One Christmas feast in Marking Time relies on two rabbit pies, because though meat was rationed at the time, people were allowed “to shoot vermin on a Sunday, [and] luckily rabbits count as that.”

Today, unlike in Howard’s time, there are excellent English sparkling wines. Ridgeview makes one of the best.

In order to bridge the gap between my expectations of glamorous English country cooking and the realities of choosing a menu from Howard’s books, my spirits collaborator, Hank Zona, sourced me a bottle of sparkling wine from Ridgeview, an English vintner from Sussex, home of the Cazalets’ fictional estate (and Howard’s real one). England is an emerging region for sparkling wine, thanks, sadly, to climate change, and the twenty-five-year-old Ridgeview is one of the first and most prestigious makers. Their Bloomsbury line, which I especially like, has what Zona describes as “citrusy crispness and tart apple flavors, combined with a touch of the toast and creaminess found in many champagnes.” With some apologies to this excellent bottle of bubbly, I served it with Delia’s rissoles, made in true duchy fashion with leftover chicken I had on hand (not hugely recommended, though I’ve made some recipe tweaks below that may help), plus a sunchoke soup, a rabbit-and-gammon pie, and a rice pudding.

The soup and pie recipes both come from Howard’s own cookbook, Cooking for Occasions (1987), written with her friend Fay Maschler, the restaurant critic since 1972 for the London Evening Standard. I chose the soup because sunchokes are in season at the moment and Howard included it in a section devoted to “foolproof” recipes. That a sunchoke could be considered foolproof surprised me since I’ve always considered the humble, knobby-looking tuber (part of the subterranean reproductive unit of a sunflower) to be a challenging ingredient that has a strange gassy smell when cooked. I found the pie in a section devoted to picnics, and it was the only dish mentioned in the Cazalet Chronicles that I found Howard’s own recipe for. It was a challenge of a different type, since it called for boiling a rabbit together with some pig’s trotters, deboning it, making a hot-water crust, pouring the bone stock into a little hole in the top of the baked pie, and leaving it to set.

A technique that is more difficult than it looks.

I hoped that all my dishes would achieve a sort of rustic elegance and simplicity, with hearty, meaty, creamy, nutmeg-y flavors evoking the English countryside. The soup almost did, though I seasoned it according to my own specifications after I found Howard’s bland. The pie smelled delicious but was also bland, with a thick, flavorless crust and a broth that didn’t set. I’m uncertain if this lack of taste could be attributed to Howard’s recipe or was just user error, since most of the techniques were unfamiliar to me. Lastly, I chose one of two rice puddings from Delia’s—the “rich” version, since the one seasoned with prunes and apricots sounded like a childhood nightmare. The finished product had a thick layer of butter on top and was not to my liking, though in scarcer times it may have been a treat.

Throughout my adventure with the Cazalets’ kitchen, I thought longingly of Mrs. Cripps, who surely would have done it all better. I also considered that if Howard’s food defied my expectations in a bad way, with her writing it was the reverse—and that’s what really matters.

Foolproof Sunchoke Soup

Adapted from Cooking for Occasions, by Fay Maschler and Elizabeth Jane Howard.

2 lbs sunchokes

3 strips of bacon

2 tbs butter

1 cup diced fennel, celery, and carrot

6 cups chicken stock

1/4 tsp nutmeg (or more, to taste)

salt

pepper

dollops of sour cream, to serve

Scrub and cut up the sunchokes. You need not peel them, but do clean them thoroughly.

Fry the bacon till crispy in the pan you plan to use to cook the soup. Then remove the bacon and reserve. Add the butter to the bacon grease, then the diced fennel and carrot, and sauté for a few minutes, until beginning to soften.

Add the sunchokes and stir to coat them in the oil mixture. Then add the chicken stock, cover, and bring to a boil.

Turn down to a simmer and cook until the artichokes are soft. Pass the mixture through a vegetable mill, or blend using a blender or immersion blender. Return to heat, season with nutmeg, salt, and pepper, and taste. Continue to season until the soup suits your liking. Serve with crumbled bacon and a dollop of sour cream.

Rissoles

Recipe adapted from Delia’s Complete Cookery Course.

8 oz cooked meat, preferably lamb or beef

a small onion

a slice of high-quality stale bread, crust removed

2 tbs milk

1/4 tsp cinnamon

2 tbs chopped parsley

a clove of garlic, chopped

an egg, beaten

salt and pepper, to taste

1/4 cup whole wheat flour, seasoned to taste

oil for frying

Place the bread to soak in the two tablespoons of milk.

Grind the meat together with the onion using the meat-grinder attachment of your mixer, or chop finely by hand.

Mash the soaked bread in the milk with a fork, then add the mixture to the ground meat, along with cinnamon, garlic, parsley, egg, and salt and pepper, to taste. Mix with your hands to combine.

Form the mixture into small patties, roll in the seasoned flour, and fry on medium heat until cooked through, five minutes per side.

Cold Rabbit-and-Gammon Pie for a Picnic

Adapted from Cooking for Occasions, by Fay Maschler and Elizabeth Jane Howard.

For the filling:

a rabbit

1 lb lean gammon (or thick slice of ham of a nonsmoked variety)

2 pig’s trotters (or a shank, if trotters are unavailable)

1 cup white wine

1/2 lemon, sliced

a bay leaf

an onion, peeled and sliced

3 carrots, scrubbed and sliced lengthwise

2 stalks celery

8 peppercorns

a sprig of thyme

6 coriander seeds, crushed

For the crust:

4 cups flour

1 tsp salt

a stick of butter

1 cup water

This pie needs to be cooked, cooled completely, then filled with stock and chilled again before serving. Start two days in advance of service.

Put the rabbit and gammon together in a large pot, along with all the other filling ingredients, and cover with water. Bring just to a boil, then turn down to a simmer, and cook until the rabbit is tender and comes away from the bones when probed, about an hour. Remove the rabbit and gammon, and reserve. Strain the broth and discard all the other ingredients. When the meat has cooled, pick the rabbit flesh from the bones, and cube the gammon.

Preheat the oven to 350.

Next, make the crust. Combine the flour and salt in a large bowl, and whisk to combine. Separately, melt the butter on low heat, then add the water and bring to a boil. Working quickly, add the wet mixture to the dry, and stir. This must be done quickly because the paste needs to be molded into shape before the butter has time to solidify; if this is done too slowly, the paste will become brittle.

Put a third of the paste in a cloth, and keep warm. Put the rest into an eight-inch springform pan: press it down over the bottom and then up the sides with your fingers. Now take the rabbit and gammon and fill the tin, but don’t press the meat down. Take the remaining third of the pastry and press it lightly with the palm of your hand into a round for the lid. Place this on top of the pie, trim to fit, and pinch it around the edges to seal. You can use leftover trimmings for cutouts for the top of the pie. Make a hole in the center of the pie with your little finger.

Bake for about ninety minutes, until the crust is golden brown. Let cool completely.

When the pie is cold and the stock has become a jelly, take two cups of stock and warm it in a pan until just dissolved. Using a measuring cup or other vessel with a spout, pour the liquid gently through the center hole of the pie. Do this in little spurts; you will find that if you wait a moment between each pouring, the pie will absorb a surprising amount of liquid. Leave the pie to set, and serve cold.

Rice Pudding

Recipe adapted from Delia’s Complete Cookery Course.

1/2 cup sushi rice

3 cups milk

1/3 cup sugar

4 tbs butter

3 eggs, beaten

grated rind of 1/2 lemon

pinch of nutmeg, freshly grated or ground

Preheat oven to 300.

Butter a four-cup baking dish.

Put the rice into a saucepan, add the milk, and bring it slowly to the brink of simmering. Allow to cook gently until the rice is chewy and almost tender, around twenty minutes.

Next, add the sugar and butter, and stir until dissolved. Take the saucepan off the heat, let the mixture cool until it is merely warm, and then add the beaten eggs and lemon zest. Transfer to the buttered dish, sprinkle on some freshly grated nutmeg, and bake for forty minutes—or longer if you prefer a thicker consistency. Cool and chill before serving.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

Turtle, Turtle

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces the moments before her daughter leaves for college. It ran every Friday in November, and returns this winter month, then will again in the spring and summer.

Childhood is full of fictions, at least it should be. When my daughter, Indie, was little, her favorite game to play in the pool was Turtle, Turtle. She’d climb on my back, and I’d swim around saying “Turtle, Turtle,” the way you’d say “Ribbit, Ribbit” for a frog.

We found him in my parents’ backyard pool, all four of his legs flipping. Indie was seven that summer. She and I had been taking one last swim before heading back to Oklahoma, four hours north. While I dove down, Indie stood on the steps of the pool. The turtle, a red-eared slider, was tiny, about the size of my palm. Indie named him Flipper.

We lived in a duplex those four years in Oklahoma. We had a little garden patch beneath our front window. There were four units in all, so we shared a sidewalk with an opera singer who worked at the grocery store, a large, loping Marine who had done two tours in Afghanistan, and a frumpy student who mostly wore brown and sat outside to study in a chair from his kitchen. I had a visiting professor’s salary, and there wasn’t a month when we made it to the thirtieth or thirty-first before we ran out of money.

Indie and I made a home for Flipper out of a kitty litter box, a blue one. We filled it with rocks, grass, and leaves, and put it in our garden. He was a happy turtle. He’d bask on one of his rocks in the corner or burrow beneath a layer of leaves. When we’d find him with his right front leg stretched out, we’d know he was sleeping.

For the people in our duplex community, life was either on hold or had no hold. At night, the singer played piano, practiced trills, but sometimes she played another song, long and loud sobs, an opera of despondence. The Marine stared at the blare of his oversize TV from his couch, working through a twelve pack every night, and the student made the same walk to the grocery store every day, a drooping plastic bag in each hand. We wondered what their real stories might be. I’m sure they wondered about mine.

I don’t know when I made up the story, but at some point I told Indie that Flipper’s house was a coffee shop he ran called Sinatra’s. From sunup to sundown, Flipper took orders, whipping up Frappuccinos and lattes. He even had a little apron, like the one the Marine wore when he cooked. And the student, on his daily errand, bought the ingredients and supplies Flipper needed. Indie and I’d step out to the porch and order drinks, and we’d marvel at the long line or see that it was a slow day, and some mornings, one of us would guess the muffin from the scent—cinnamon.

Our neighbors liked to say hello to Flipper when they passed, coming and going, but when we told them about Sinatra’s, we started hearing them ask things like, “Hey, Flipper! How’s business?” or order a vanilla latte.

One day, the opera singer knocked on our patio door and held up a three-inch plastic dinosaur, purple and yellow. She said she thought Flipper could use some help. Indie rushed out and set the dinosaur on top of a rock in the middle of the café. We named him Frank.

That coffee shop gave us all a fiction we needed.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

January 9, 2020

The Horsewomen of the Belle Époque

In Susanna Forrest’s Écuryères series, she unearths the lost stories of the transgressive horsewomen of turn-of-the-century Paris.

Blanche Allarty (source Rosine Lagier)

In Berlin, the old patches of wasteland left by the bombings of World War Two are vanishing, replaced by shiny glass and granite luxury apartments. But sometimes, the remaining squares of grass and cracked concrete will throw up white tents, brightly painted caravans, and swirls of colored light bulbs, moth-eaten camels grinding hay in their teeth—the unmistakable children’s-book shorthand for the circus. Scarlet and yellow posters sprout on neighborhood lamp posts offering matinee performances and promising that the animals are well kept (“Doesn’t your dog like driving in a car?” asked one poster I saw. “Our dogs are no different.”) At least once a Christmas season, a zebra escapes and gallops through a German town. Despite the animal-welfare restrictions and Netflix, the circus endures.

I wasn’t a child who liked clowns, and, barring a large and sticky red lollipop, I barely remember being taken to the Moscow State Circus when it visited my British hometown, but for the last nine years I’ve been scratching up the time and funds to immerse myself in another circus—that of nineteenth-century Paris—for days at a time. I’m looking for fragments of lives, for women who lived at the center of public attention while simultaneously being marginal. They dealt with racism, misogyny, abuse, and great physical danger but, like the circus, they endured.

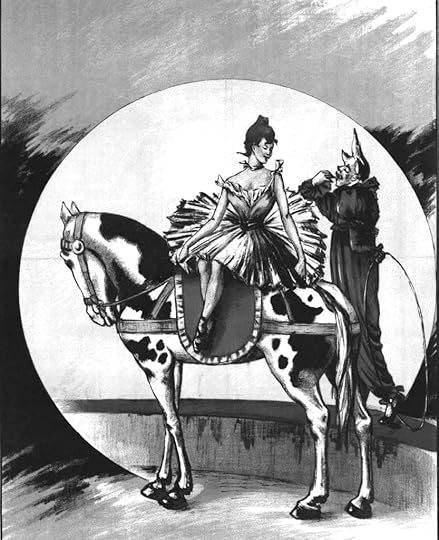

I read about the circus écuyères or “horsewomen” of that period in Hilda Nelson’s The Ecuyère of the Nineteenth Century in the Circus when I was working on my first book, a cultural history of pony-mad girls called If Wishes Were Horses. They were perhaps the first professional horsewomen in an equestrian culture storied in masculinity. They came in two forms. One, another children’s-book silhouette recognizable from Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat, and Picasso: the vaulter or acrobat who balanced on the broad barrel of a docile rosinback and leaped through flower hoops or wobbled in arabesques, as sinewy and feminine as a ballerina.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Circus: Work in the Ring, 1899

The other circus horsewoman, the haute école écuyère, has largely disappeared from our consciousness, though she was the star of the nineteenth-century circus. She’s a dressage or “upper school” rider gingering up the classical moves of the courtly riding academies of early modern Europe by jumping over dinner tables and making her horse walk on its hind legs. She, too, was drawn by Toulouse-Lautrec in his 1899 “Au Cirque” series—the unnamed woman bent in a strange, spidery curtsey or sitting, pin-headed, in a severe riding habit on her horse.