The Paris Review's Blog, page 182

February 26, 2020

Sex in the Theater: Jeremy O. Harris and Samuel Delany in Conversation

Left: Samuel Delany (photo: Michael S. Writz) Right: Jeremy O. Harris (photo: Marc J. Franklin)

At three in the afternoon on a Friday in late January, Jeremy O. Harris arranged for an Uber to bring Samuel Delany from his home in Philadelphia to the Golden Theatre in New York City. Chip, as the famed writer of science fiction, memoir, essays, and criticism prefers to be called, arrived in Times Square around seven that evening to watch one of the last performances of Harris’s Slave Play on Broadway.

Though the two had never met before, Delany has been hugely influential on Harris, and served as the basis for a character in the latter’s 2019 Black Exhibition, at the Bushwick Starr. And Delany was very aware of Harris. The superstar playwright made an indelible mark on the culture, and it was fitting that the two should meet on Broadway, in Times Square, Delany’s former epicenter of activity, which he detailed at length in his landmark Times Square Red, Times Square Blue and The Mad Man.

After the production, Harris and Delany met backstage. “A lot of famous people have been through here to see this play, but this is everything,” Harris said. The two moved to the Lambs Club, a nearby restaurant that Harris described as “so Broadway that you have to be careful talking about the plays. The person that produced it is probably sitting right behind you.” (Right after saying this, Harris was recognized and enthusiastically greeted by fellow diners.) Over turkey club sandwiches and oysters, Harris and Delany discussed identity, fantasy, kink, and getting turned on in the theater.

HARRIS

Can I ask you about the play? How are you processing it?

DELANY

I was confused in the beginning, but then I realized, Aha! This is therapy. And then, Aha! The therapists are nuts! Then I traveled around having sympathy for all the characters, especially the stupid good-looking guy. He was sweet, I’ve had a lot of those. The character that I identified with most is the one who insists that he’s not white. I used to get that all the time, I mean, the number of times I was told by my friends at Dalton, Well, I would never know that you were black. As if I had asked them.

One of the best things that ever happened to me happened when I was about ten, which was a long time ago. I was born in 1942, so this is 1952, and I’m sitting in Central Park doing my math homework. This kid, he could have been about nineteen or twenty, and I think he was homeless, he walks up to me, and he says to me with his Southern accent, You a n****, ain’t you? I can tell. You ain’t gonna get away with nothing from me.

And I looked up at him, I didn’t say anything, and he looked at me and said, That’s all right. You ain’t gonna get away with nothing from me.

And I was so thankful for it. I realized, first of all, he was right. He was being much more honest with me than any of my school friends.

It was also my first exposure to white privilege. There were a lot of white people from the South who felt obliged to walk up and say, You’re black, aren’t you? They thought it was their duty. In case I thought, for a moment, that they didn’t know. This was part of my childhood: people telling me that I was black.

HARRIS

I appreciated the fact of race in the South. That is one of the reasons why I think a play like Slave Play came out of me. Growing up, I was considered special because I looked the way that I looked, and yet I was smarter than all the white kids, and these are the richest white kids. The teachers had to understand that in some way, and so they thought that if I was smarter than any black person, smarter than all the white kids, that must mean I was an alien. You’re an alien kid, and let’s treat you like an alien. We’re going to put you on a pedestal and other you more than you’re already othered through this intellect.

When I came up North, I encountered this notion that my performativity, the way I performed and the way I engaged in the world, made me not black. I was not black and not white but in a different way than in the South. In the South, everyone was like, you’re black and different and therefore you’re even more special, but the blackness was always there. In the North, they pretended that the blackness wasn’t why they saw me as different. It made me hate the North. You guys are more fucked up. The fact of my blackness is always there, and when I meet someone like you, Chip, I’m like, you’re black.

The sense of gender-nonbinary spaces is something you already knew before there was language for that in the public sphere. Do you feel like that was partially because of your race? Because of the way in which your race was understood?

DELANY

Yes, partially, yes.

HARRIS

You have an engrained articulation for queerness, and you wrote it into your fiction better than anyone could write it into theory. I’ve always been so inspired and enthralled by that. The only thing that I have an innate understanding of is my psyche, all learned through osmosis, from having had a therapist and also from existing in a family that refused to acknowledge that different brains work differently. I could look around my family and figure out that my uncle had schizophrenia just by cataloguing the way he processed the world. I thought, It’s interesting that Uncle Chris listens to the radio when he talks to me. That’s the only time that we can make lucid conversation, when a radio is playing static next to him.

DELANY

Did you ever hear of the radio play made out of The Star-Pit? For a decade it was played over WBAI once a year as a Thanksgiving tradition. I do the narration. It was hundreds of years ago.

HARRIS

You do have an actor’s voice.

DELANY

I was a ham. I was a stagehand in the Charles Stanley dance company, and the dancers and all of the stagehands had to perform onstage naked. I got used to performing on the stage naked a long time ago, which is interesting because my partner, Dennis, has never had any stage experience. We have been together around thirty years and we have two entirely different takes on our bodies. He is actually very private. He walks around the house naked with me, but he doesn’t want me shooting pictures of him naked, which I am prone to doing.

However, there are many naked pictures of me around. There is a woman named Laurie Toby Edison who has a book of male nudes called Familiar Men, and there’s a photo of me in there from when I was fifty-five. Dennis and I also posed nude for Mia Wolff for Bread and Wine.

I’m not shy. I have had sex with so many men I literally cannot count. I once estimated it must be about fifty thousand.

HARRIS

I can’t imagine fifty thousand penises entering in and around my orbit.

DELANY

Well, it was because of the theaters in Times Square, where you could go in and have sex with twelve people in twenty-four hours. You made out much better in the theaters than you could at the bars. Then our totally vicious mayor, Rudy Giuliani, closed them all down. Dennis and I used to go to the theaters and have sex with each other and he was comfortable doing that. One October, we went to the theater and there were chains around the doors. Dennis used to say that Rudy Giuliani ruined our sex lives.

HARRIS

I’m working on a movie about a queer party, so I went to a bunch of queer parties in Berlin, on Fire Island, and in LA this summer. We were at one party in Berlin for thirty-six hours, and a friend of mine, who had spent most of that time continuously having sex in a blacked-out room, swore we were only there for three hours. There is something really interesting about group sex, dark-room sex, where you can lose all relationship to time.

In Slave Play, the sexual encounter between the gay couple had to feel the most queer so it could be revealed as the most mundane later. I mean, they’re into boot licking, and that’s like a Thursday night at the LabOratory in Berlin. That’s not high kink, it’s midlevel. High-level kinks are anything related to large objects in orifices, because it requires training. You can’t go into that as a rookie. And anything with high psychic consequences is high-level kink.

What do you consider high-level kink?

DELANY

Well, I got to the point where I could fit almost anything down my throat. Which is good, because Dennis is hung like a horse. If I had met him when I was much younger, maybe we never would have gotten together.

HARRIS

You had trained.

DELANY

I remember going down to one of the bars down on the waterfront years ago. They used to have something called Wet Night on the second Wednesday of the month. I was drinking so much urine that it began to shoot out of my butt. It was going in one end and coming out the other end, and it was really bizarre. It was quite an amazing experience, but I only did that once. I wrote a few letters about this to my friend Mark, who is now dead, but the letters served as the basis for parts of my book The Mad Man.

HARRIS

How much urine does one have to drink for that to happen?

DELANY

Well, I was not measuring it. I was sitting in the john, one guy after another came in, and I let them know that they could use me. And it was fun. And, you know what, there was no damage whatsoever. It’s sterile, it’s absolutely sterile.

You have this bag of hydrochloric acid down there, it’s the first step on the immune system. Very few germs get through that. If you get it as far down as your stomach, you’re either fine, or you’ll throw it up. Unfortunately, I sucked so much dick I lost my gag reflex, so after a while I stopped being able to throw up.

HARRIS

In Black Exhibition the character Little Delany says, “I’m an expert oralist.”

DELANY

Well, I was.

HARRIS

I’m glad it was true to you. In a lot of ways, my sexual imaginary was so much more broad than my sexual experience until this summer. This summer I started engaging more frequently, partially because I had writer’s block and I thought it would be helpful to engage in some of the things that I was thinking about. I feel like a lot of the writers I know have the same experience, but you seem to be the opposite. You seem like your sexual experience must outpace your sexual imaginary.

DELANY

For a while it did. Now, it has kind of gone the other way. I’m not nearly as sexually active now, but part of that is just the neighborhood I live in. I used to be in the gayborhood. Now I’m in the Museum District. I can walk to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Barnes is right over there, and the Rodin Museum, which are all wonderful.

HARRIS

I’ve only had one experience in Philadelphia, but I did have sex there. I used to tour with my friend’s band, Florence and the Machine, and one night after a show we went out to a club, and one of the fans of the band was trying to needle his way into our hang space via having sex with me. All he got was sex with me.

It felt like a not-very-happening gay space. In LA and London and New York, having sex in a bar bathroom is not crazy, but this guy in Philadelphia made it seem like it was the most insane thing we could possibly be doing. Do you feel like that’s true of the environment there? That it’s a little more puritanical in Philly than it is in New York?

DELANY

Now it is, but years ago, when all of the films in New York closed, you could still find theaters to go to in Philly. They’re now all gone. As far as I know, there are no theaters like that anywhere.

It was a really interesting institution, and a very welcoming one for gay people. I met a lot of people and I made a lot of friends at the theaters. Dennis and I used to use the same theater, but we never met there because I would use them during the day and he would use them at night. Once we were together, we loved to go. Dennis loved going to the theater and getting sucked off and I loved going to the theater and sucking him off.

HARRIS

I love that you say “used” the theater. That’s such an interesting verb choice. The theater was a utility, something that was used, not just somewhere to go to, to be.

DELANY

Right, which is to say, people got used to going to the place, sitting in the theater, and masturbating. Some of the guys didn’t mind if you joined them, some of them didn’t want to be bothered, but usually there were enough of each to make it work.

HARRIS

Were there any full-on orgies at the theaters?

DELANY

No, it was just a lot of guys going around sucking people off and masturbating, that was that. There was very little fucking. There was one place called the Variety Photoplays that had a spot behind the balcony called the lounge where every once in a while someone would drop their pants, lean over, and get screwed. A guy named David Wojnarowicz made a book of drawings called Memories That Smell Like Gasoline, and they were very accurate. The roof of the Variety Photoplays used to leak, it would drip down, and in one of Wojnarowicz’s drawings, there’s a bucket there catching water.

HARRIS

It would be amazing if there were more documentation of these queer spaces.

I wanted to ask you how you felt during the first act of the play. One of my goals was to make people feel turned on in the theater again, but also to have them be confused about why they were turned on.

DELANY

I didn’t feel turned on at any point during the play. However, I was very moved by what happened between the characters. In your mind, is the guy who keeps referring to himself as not white, part black?

HARRIS

He’s not part black. I wanted it to be ambiguous. I think he is someone who is non-racialized in a way that a lot of my ex-lovers have been. I have a recent lover who is frequently perceived as white, but I’m from the South, so he doesn’t look white to me. Some people are like, He’s just Jewish. Whatever people need to say to make sense of his race, they say it. I wanted that to be the character Dustin.

DELANY

I found it both interesting and somehow inevitable that you chose to have the heterosexual couple come out as the last people we see onstage.

HARRIS

I often think about just how queer straight people are. I think straightness is way more queer than queerness now. What two straight people do together is insane. We all walk around every day and talk about gender and equality, and then we all go into bedrooms and play power games around our gender and flip power back and forth all the time. What does it mean to be a straight girl that’s like, I am a girl boss, but choke me. That’s really interesting, more interesting than me saying that to a dude. Me saying that to a dude is like, Yes, sure, I’ll choke you I guess. There’s nothing abject about that anymore, but there is something interesting and abject in our current moment around thinking about what fantasy means inside of heterosexuality.

What does it mean to be a man who is trying to be so good in everyday life that he can’t engage with that fantasy of being in power, because he also feels like his fantasy reifies his reality? It’s like Antony and Cleopatra, it’s a tragedy. Straight couples are fucked up.

DELANY

I’ve been thinking that for years.

HARRIS

Can we go back to fantasy? I was a fantasy nerd growing up, and I feel like sci-fi still helps me make sense of our current moment. I think of Slave Play as a speculative fiction. People ask me where I found out about Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy, and I tell them, My brain. It does not exist.

And yet I feel like there’s some reality in our modern space where couples might think about going to something like Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy. As a child I went to exposure therapy for my PTSD, and it was really fucked up. It was like a horror film, what they made me go through psychologically to “fix me.” So this is not that far outside of the realm of reality, it’s a mirror to how psychotherapy is a psychedelic endeavor.

DELANY

I always used to feel like with religion, art, and therapy, each was trying to destroy the other two. Sometimes you get one of them, sometimes two, but if you have all three, it is hell. All of them do promise that somehow you’ll have a better life. Up until I was thirty-five, I would have these attacks of dissociation, and sometimes it would manifest as terror, sometimes as panic attacks, sometimes as going away from it all. And then they stopped.

HARRIS

The brain is a fickle muscle. There are things that can wake it up and stretch it out.

Waiters hovered nearby, the house lights were on, the restaurant had all but closed. As they gathered their belongings, Harris and Delany continued to discuss film adaptations of Delany’s work, and there was mutual excitement over the idea of a future collaboration. Delany had brought copies of his two most recently published books for Harris, the Dover Thrift Edition of Dark Reflections and The Atheist in the Attic.

They walked around Times Square for a short while, Delany pointing out sights where restaurants and bars significant to him once stood; the ones that remained were rare. Harris navigated toward the spot where Delany would be picked up to head back to Philadelphia. They continued talking as they approached the car.

HARRIS

Can I ask you—you’ve written so much. And you’re still writing. Do you ever feel like you’re done?

DELANY

Well, I write a lot less than I used to. But it’s like Da Vinci said, a work of art is never finished, it’s abandoned. You just have to know when to abandon it.

They thanked each other warmly for the evening and parted ways.

Read our Art of Fiction interview with Samuel Delany in our Summer 2011 issue.

Toniann Fernandez is a writer based in Brooklyn.

February 25, 2020

Redux: Pull the Language in to Such a Sharpness

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Maya Angelou.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re celebrating Black History Month by highlighting African American writers in our archive. Read on for Maya Angelou’s Art of Fiction interview, Edward P. Jones’s short story “Marie,” and Toi Derricotte’s poem “Peripheral.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And don’t forget to listen to Season 2 of The Paris Review Podcast!

Maya Angelou, The Art of Fiction No. 119

Issue no. 116 (Fall 1990)

I try to pull the language in to such a sharpness that it jumps off the page. It must look easy, but it takes me forever to get it to look so easy. Of course, there are those critics—New York critics as a rule—who say, Well, Maya Angelou has a new book out and of course it’s good but then she’s a natural writer. Those are the ones I want to grab by the throat and wrestle to the floor because it takes me forever to get it to sing. I work at the language.

Marie

By Edward P. Jones

Issue no. 122 (Spring 1992)

Every now and again, as if on a whim, the Federal government people would write to Marie Delaveaux Wilson in one of those white, stampless envelopes and tell her to come in to their place so they could take another look at her. They, the Social Security people, wrote to her in a foreign language that she had learned to translate over the years, and for all of the years she had been receiving the letters the same man had been signing them. Once, because she had something important to tell him, Marie called the number the man always put at the top of the letters, but a woman answered Mr. Smith’s telephone and told Marie he was in an all day meeting. Another time she called and a man said Mr. Smith was on vacation. And finally one day a woman answered and told Marie that Mr. Smith was deceased. The woman told her to wait and she would get someone new to talk to her about her case, but Marie thought it bad luck to have telephoned a dead man and she hung up.

Peripheral

By Toi Derricotte

Issue no. 124 (Fall 1992)

Maybe it’s a bat’s wings

at the corner of your eye, right

where the eyeball swivels

into its pocket. But when

the brown of your eye turns

where you thought the white saw,

there’s only air & gold light,

reality—as your mother defined it—

(milk/no milk) …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

Emily Dickinson’s White Dress

Photo: James Gehrt.

The first time the writer Thomas Wentworth Higginson met Emily Dickinson, he remembered five details about the way she entered the room: her soft step, her breathless voice, her auburn hair, the two daylilies she offered him—and her exquisite white dress.

Dickinson’s white dress has become an emblem of the poet’s brilliance and mystery. When Mabel Loomis Todd moved to Dickinson’s hometown in the 1880s, she gushed about the poet’s attire. “I must tell you about the character of Amherst,” she wrote her parents. “It is a lady whom the people call the Myth … She dresses wholly in white, & her mind is said to be perfectly wonderful.” Jane Wald, the executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum, believes Dickinson began dressing primarily in white in her thirties, and it was common knowledge around town that a white dress was the poet’s preferred article of clothing. Dickinson realized people gossiped about what she wore, and once joked with her cousins, “Won’t you tell ‘the public’ that at present I wear a brown dress with a cape if possible browner, and carry a parasol of the same!”

Photo: James Gehrt.

Only a few articles of Dickinson’s clothing have survived: a brown snood, a paisley wrap, a blue shawl, and a single white dress. The dress is unpretentious: cotton piqué, loose fitting with no waistline, featuring a box-pleated flounce at the bottom, twelve mother-of-pearl buttons, a flat collar, and a pocket on the right hip. More than fourteen yards of embroidered lace edge the collar, cuffs, pleats, and pocket. The surviving dress is typical of an inexpensive house garment of the late 1870s or early 1880s and was most likely worn during the last years of the poet’s life. Known as a “wrapper,” it was casual clothing for home and not for social occasions. Stitches indicate it was made on a sewing machine with some handwork. Comfortable and easy to clean, it did not require a corset.

No one talks much about Dickinson’s brown snood, but speculation concerning the poet’s white dress abounds. There are reasons for that, of course. Some of Dickinson’s most memorable poems reference white. “A solemn thing – it was – I said -/ A Woman – white – to be-”; “Dare you see a Soul at the ‘White Heat’?”; Mine – by the Right of the White Election!” Her letters also evoke the color. As a young woman, she imagined her own death scene, “eyes shut and a little white gown on, a snowdrop on my breast.” A decade later, in one of her most mysterious letters, Dickinson wrote to an unidentified Master, asking, “What would you do with me if I came ‘in white’?” Critics contend Dickinson’s white dress might suggest renunciation, purity, spiritual devotion, escape from the daily world, or fierce dedication to art. No single rationale has stuck. In justifying her reluctance to publish, Dickinson once remarked, “My barefoot rank is better.” Perhaps the dress is her barefoot fashion statement.

Photo: James Gehrt.

While preparing my new book, These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, I asked the photographer James Gehrt to take pictures of Dickinson’s white dress at the Amherst Historical Society. For someone who wrote, “The Soul selects her own Society,” Emily Dickinson is everywhere in today’s Amherst. Her portrait is on a utility box in the center of town, a local bakery uses her gingerbread recipe, and visitors regularly leave items at the poet’s grave: notes, coins, and recently a soggy copy of Dante’s Inferno.

The afternoon we shot the photos, Marianne Curling, the curator of the Amherst History Museum, helped James lift the form supporting Dickinson’s dress out of its archival case. Once the dress was upright, James began taking close-ups of the collar, the cuffs, and that pocket—just the right size for a pencil and paper. It was late in the afternoon, and the light was lovely in the museum, one of the oldest houses in Amherst. With Marianne’s help, James carefully moved the form. “Be careful with her,” I heard myself saying. Later on, James positioned the garment’s arms to simulate motion. “I want to see if we can make her move,” he said. All of us that day used personal pronouns to refer to the dress—not “it” but “her,” as if Emily Dickinson were still inhabiting the dress and moving with her own soft step.

Photo: James Gehrt.

Before Higginson met Emily Dickinson that auspicious day, he confessed that he could not always understand her. “Sometimes I take out your letters & verses, dear friend, and when I feel their strange power, it is not strange that I find it hard to write & that long months pass. I have the greatest desire to see you, always feeling that perhaps if I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you; but till then you only enshroud yourself in this fiery mist & I cannot reach you, but only rejoice in the rare sparkles of light.”

Emily Dickinson’s white dress is significant because it is so personal, so intimate, a literal embodiment of who she was. But like the poet herself, the white dress is also inscrutable—more a glint than a conclusion. The dress stayed in Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s mind because it was like those rare sparkles of light—blinding, transitory, and elusive. Is it any wonder? Evanescence was Dickinson’s stock-in-trade. Her poems freeze life’s fleeting moment with startling clarity.

James’s photographs of Dickinson’s white dress capture the poet’s weightless energy and airy restlessness. They reveal something else, too—about both the poet and her poems. Dickinson’s a sly one. She will always be furtive. Always here and gone. There is dash and vanish to everything about her. Just when you think you have her, she slips out of sight.

Photo: James Gehrt.

Photo: James Gehrt.

Photo: James Gehrt.

Photo: James Gehrt.

Martha Ackmann, author of Curveball and The Mercury 13, writes about women who have changed America. The recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship, Ackmann taught a popular seminar on Dickinson at Mount Holyoke College and lives in western Massachusetts. Her latest book, These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, is out this week from W. W. Norton.

Finding Anna Karina

Anna Karina

Anna Karina’s rehearsal for her first major scene with director Jean-Luc Godard ended early. The scene was for the film The Little Soldier (1960), in which the male lead photographs Karina’s character in her apartment, asking her questions and telling her to move around so he can get at her “truth.” Godard intervened and took the mock interrogation one step further, demanding to know when she had first had sex and how many men she’d slept with. She didn’t know whether the director was asking her or her character, and Karina’s face flashed from white rage to scarlet embarrassment. “Ça ne vous regarde pas,” she replied in hesitant French, It’s none of your business. The line is included in the final cut.

This exchange between Karina and Godard launched one of the most important partnerships in the history of cinema. A year later, they married, and Paris Match called Karina “the newlywed of the New Wave.” She went on to star in six more of Godard’s feature films, becoming the icon of a movement. Her body served as the visual anchor for his films, and her own language often appeared word for word in his scripts. Was there anything about her that was not his? Godard didn’t think so. When he worked on a tight budget, Karina went unpaid for her work as an actress, with the justification that they lived together.

The kind of intellectual attracted to Godard’s cinema has often remained uninterested in Karina, beyond the superficial planes of her face. In the catalogue of the National Library of France, there are 152 critical studies taking on his work, and seem to be none devoted to Karina. In the books on Godard, she is featured exclusively during his so-called Karina Years, disappearing after their last collaboration together, Made in U.S.A. (1966). There does exist a rigorous school of feminist criticism that takes on the representations of female characters in New Wave cinema (notably the work of Geneviève Sellier), but this line of inquiry considers the women in these films through the symbolic violence enacted against them rather than considering their personhood.

In the obituaries written after Karina’s passing on December 14 last year, critics have attempted to rehabilitate her life story. But these write-ups consistently refer to Godard to do so. Karina is cited explaining how she taught him not to slam doors; he is quoted calling her a “woman of action.” I started writing this piece with every intention of “finding” Karina, but fell into the same trap in my first draft: I occluded Karina’s voice by looking for it in the images Godard made of her.

*

The story of Karina, born Hanne Karin Blarke Bayer in 1940 in Solbjerg, a suburb on Denmark’s east coast, has been turned into a fairy tale. Abandoned by her father and neglected by her mother, she found solace in the pizzazz of dance numbers and American jazz, often going to the movies at the invitation of her mother’s boyfriends. At the age of seventeen, she hitchhiked from Copenhagen to Paris to follow her dream of becoming a performer. Her first break: a modeling agent spotted her at Les Deux Magots, the Left Bank café of the Tout-Paris. “She was really dirty,” the agent later said. “But she had an incredible gaze that seemed to devour everything around her.” Soon after, she landed the cover of Elle. Coco Chanel gave her the screen name, or so the legend goes, the singsong ANN-a kar-IN-a a syllable off from Tolstoy’s heroine, as if she’d go on to live a life out of a Russian saga.

Her modeling career was short-lived because she couldn’t sit still. Her most famous cinematic moments are in her gestures: the improvised swing solo in My Life to Live (1962), the run through the Louvre and the Madison dance in Band of Outsiders (1964), her rock-skipping as she asks, “What can I do?” in Pierrot le fou (1965). The pleasure in her movements seems to belong to her above anyone else. If the existentialists had declared that every generation would need to learn to love anew, Karina was their object lesson. She seemed to act with and through her fantasies, even those informed by B movies and the discs on her record player. If her characters aspire to sing and dance in Broadway musicals, it’s because she did, too—though Godard would often lampoon the ambition and make her sing in parody.

Many New Wave actresses lacked formal training, their inexperience lending itself to the freshness of the avant-garde, but they also tended to hail from the high Parisian bourgeoisie. The public images of Brigitte Bardot, Catherine Deneuve, and Anne Wiazemsky depended on the decorum of their upbringing. Karina, on the other hand, came from nothing. She spoke French hesitantly, with an accent, and never settled into the veneer of a persona. In the slippage between Karina and her characters, there seemed to be the promise that the self was the performance, and just as invented. Her fidgety mannerisms and schoolgirl earnestness made the effort of acting visible. It revealed the masquerade of the New Wave model of femininity: though it claimed to be more natural than its predecessors, it, too, had been dreamed up by men.

*

Three of the seven feature films Karina made for Godard end with her in the passenger seat of a car, a man at the wheel, as they head into “the sunset.” In one of them, she ends up in bed. In the others, her character dies. These have always been my least favorite. I see them as willful acts on the part of Godard to finish her off so that she would not outlive his camera. In The Little Soldier, the character that serves as his alter ego flatly states that women shouldn’t live past the age of twenty-five. The pronouncement would serve as an eerie harbinger: when Karina was twenty-five, their collaboration fell apart. They divorced in 1965.

He never filmed her in the buff (only body parts framed in bits and pieces) as he did with other young actresses, such as Bardot in Contempt (1963). His interest in Karina was first piqued by her refusal to undress; he had wanted her to play a minor nude role in Breathless (1960), which she turned down. But even if Karina always kept her clothes on, she gets beaten up, tortured, and killed in many of his films. Godard seemed to think of it as war. “The cinema does not query the beauty of a woman,” he wrote during his tenure as a critic. “It only doubts her heart, records her perfidy.”

Karina took notice, even if she still played along. In the last scene of My Life to Live, her character, Nana, is traded by her pimp. When he stiffs the deal, he uses her body to protect his; she is shot, shot again, then almost run over with the getaway car. The original script featured what might have been called a happy ending. Nana was supposed to earn more with her new boss, and find love. When Karina learned of the Godard’s revision, she tried to commit suicide, her second attempt during their marriage.

*

Karina’s directorial debut, Living Together (1973), can be seen as a pointed response to My Life to Live. There’s the echo of the title, even more pronounced in the French: “Vivre sa vie”/“Vivre ensemble”; “together” critiques the solipsism of Godard’s heroes. As he did in his film, Karina organized the plot in tableaux, or chapter-like moments. She plays an aspiring but failed actress—just like Nana—in an ironic nod to her then-knockout career. The last shot follows her leaving work as a salesgirl. It’s another reference to My Life to Live, where Nana tries working at a record shop. The difference is that in Living Together, Karina’s character strides alone and very much alive through the streets of Paris to her infant son at home.

If there was a message in her film’s narrative, Karina also seemed to launch a manifesto in the politics of its style. In My Life to Live, Godard interspersed the opening credits with obsessive close-ups of Karina’s face. She applies the same tactic at the beginning of Living Together, but reverses the usual gendered power dynamics of the image. Rather than using the camera like a voyeur—the man looking, the woman looked at—the credit sequence moves from the male lead to Karina and back again, as if recording the mutual exchange of their look. “I wanted to show that it is difficult to find somebody to live with,” said Karina in an interview just after the film’s release. Most of the scenes are more cringe-inducing than feel-good. There’s a raw corporeality in the open-mouthed eating, alcohol abuse, and the couple’s interactions, which range from tender to violent.

With Living Together, Karina became one of the first major actresses turned auteurs. At the time, she observed that since the invention of the movies, 160 women had worked as directors as compared with with 5,000 men. Her attempt to “tell a story my way,” as she put it, was not welcomed. Though she had spent a decade in the industry, her project was met with skepticism and disapproval. One of the few exceptions was François Truffaut’s production manager, who taught her how to plan the budget. Karina founded her own company to finance the film, since nobody else would. When the movie was released, she had plans for another, with a script in hand. That project never went to production. She did not make another film until Victoria, in 2008, and it would be her last. It is always mentioned in her list of accomplishments but now does not have so much as a trailer available online. Her debut as a director coincided with a falling off in her acting career, as if by claiming authorship over her own work, she had diminished her aura as an actress in the eyes of the French cinema establishment.

Outside the public eye, Karina continued writing. “I’ve been writing short stories since I was a little girl,” she said in a 2016 interview. It was a habit that seemed less like an intellectual pastime—she left school at the age of fourteen—and more about imagining other worlds. In 1983, she published Golden City, a novel with an ambience reminiscent of the gangsters in Band of Outsiders. Building from the casual language of Living Together, she drew from wildly idiosyncratic French mobster slang with a recklessness so atypical of the written language that it can be compared to the guttural poetics of Céline.

As both writer and director, Karina had a style characterized by excess, what might be theorized as the return of everything she had never been allowed to say. In her next two novels, On n’achète pas le soleil (“One does not buy the sun,” 1988) and Jusqu’au bout du hasard (“To the edge of chance,” 1998), her preoccupation is revenge. Both feature adolescents as main characters; both end with patricide. There are no nice strangers. The twelve-year-old heroine of Jusqu’au bout du hasard is repeatedly raped by her father before being sold to a pedophile by her best friend. Rage simmers on the page.

*

If Karina was angry at the system—the institutions of cinema that kept her out, all she experienced at the hands of men in power—she refrained from expressing such feelings outside her art. “I am afraid that if I tell the truth, I will hurt lots of people,” she said in 2018. The most she ever did was politely reproach Godard for the way he humiliated her while they shot their last film together, Made in U.S.A., as well as for his extended absences. “He would say he was going out for cigarettes and come back three weeks later,” she noted in 2016.

I kept searching for Karina’s tell-all, but this was not the kind of history she was interested in. When asked about Godard in interviews—as she inevitably was—Karina was the first to disavow claims that she was anything more than his muse. “It was like Pygmalion, you know?” she said in 2016. It’s remarkable how often she is the object rather than the subject of her own sentences. A director sees her in the streets of Copenhagen; an agent spots her at Les Deux Magots; Godard watches her fawning over suds in a soap commercial and offers her a job. The word “ambition” seems to have been scrubbed from her vocabulary.

Karina gave voice and form to Godard’s women, women who put up with all manner of abuse in ways that normalized that abuse. I started watching these films as a teenager and fell in love with her spirit, which makes me wonder if I have been complicit in objectifying her as a spectator. How do we remember actresses who collaborated with male directors and, in doing so, perpetuated the way the institution of cinema treats women both on and off the screen?

Still, one can choose to interpret her abandon as a meaningful form of resistance. While playing the melancholic sister in Jacques Rivette’s The Nun (1966), adapted from Denis Diderot’s novel, Karina breaks her series of deliberate, mournful speeches with a smile. It is wide and not particularly beautiful, a grin she lets slip as if forgetting about the camera. In a role that could have so easily given way to melodramatic duress, she transforms her smile into one of the film’s high moments of surprise. She is not a pinup amalgamated from the eternal feminine: her face, her body reveal the interiority of an active subject. While Godard so often takes credit for the work, this moment is Karina’s, and Karina’s alone.

Madison Mainwaring is a writer based in Paris and New Haven.

February 24, 2020

Inside Jack Youngerman’s Studio

Jack Youngerman (photo: Hans Namuth)

Last week, my mother called to tell me, her voice wobbling, that the artist Jack Youngerman had died. He passed away on February 19, after a fall. He was ninety-three years old.

I was ten years old the first time I visited Jack’s studio. My father brought me—perhaps to pick up a print he’d bought, or perhaps simply to say hello. I recall the feeling of the space, the cool cement floors, the wide skylights, the bright colors dancing off the canvas-lined walls.

My family’s house sits approximately four hundred yards from Jack’s, at the end of a long dirt driveway in Bridgehampton, New York. As a kid, I passed his house and the adjacent studio—a small red barn nestled on the edge of a meadow—every day on my walk home from the school bus. Growing up, we had few neighbors and Jack was a friendly presence. Rosy-cheeked and white-haired, he would often drop by our house with his corgi, Winslow, trotting by his side. I would sometimes catch glimpses of him at work through the window; painting or measuring something at his big drawing table or laying a print out to dry. If he happened to be outside, we would exchange waves and quick hellos. Our relationship was friendly, if not particularly close.

It was only after my father died, in 2015, that I got to know Jack a little better. Grieving and eager to learn more about my dad’s early life, I reached out to some of his old friends. Jack was high on the list. The two of them had spent quite a bit of time together in the early seventies and my father considered Jack something of a mentor. I composed a long, rambling email to Jack. Minutes later, I received a three-word reply: come on over.

Jack Youngerman in his studio (photo: Cornelia Channing)

And so it happened that in February of 2016, I found myself in Jack’s sunlit studio once again, this time with a mug of Earl Grey tea in my hands. We began by talking about my father, but our conversation quickly roamed to other topics: his art, what books he was reading, the many ways the East End has changed in recent years. He showed me what he was working on—the design for a cobalt-blue wooden relief—and gave me a tour of his personal archive, housed in an adjacent barn. We sifted through old photographs of the years when he shared a studio space with Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly, and Frank Stella. Jack was charming, funny, and abundantly kind. As I walked home after that first meeting, he called down the road after me: “Don’t be a stranger!”

So I wasn’t. Over the following years, I’d pop by to visit Jack in his studio from time to time, to share a cup of tea and discuss his latest project. He was generous with his time, happy to answer my questions and tell me stories about the “old days”—the fifties and sixties when he first came out to Long Island.

Jack was part of a storied era of Long Island history. He expressed a longing for those years, before the East End got “all gussied up,” when it was still possible to live out there on an artist’s income, but he wasn’t one to wax poetic. He struck me, first and foremost, as a rationalist, sensitive but unsentimental. He had little patience for name-dropping or nostalgic talk. He was simply too busy for all that. More than anything, he wanted to discuss his current work, the most recent idea he’d had, and what was on the schedule that day.

Jack Youngerman, Ram, 1959 (Collection of Museum of Modern Art)

Jack in his studio was a man in his element. Everything in the space—from the neatly stacked pencil boxes to the alphabetized collection of cassette tapes (Bach and Schubert mostly)—was efficiently organized and pristinely curated. He was distinct in his tastes and disciplined in his working habits, which had varied little over the past fifty years. Since moving to Bridgehampton in 1968, Jack kept what he referred to only half-jokingly as “business hours.” He worked from around nine in the morning to around five or six in the evening, Monday through Friday, with a short break in the middle of the day for lunch. “I’m like a banker,” he joked, “except my job is a lot more fun.”

Slender and soft-spoken, Jack was as gentle as his work ethic was ferocious. He was easy-going and quick to make a lighthearted joke, which he often followed with a trill of chirping laughter. His blue eyes appeared to possess their own light source. He was, on the whole, a wonderfully bright-tempered person.

This is not to say he was without demons. It was just that, whatever they were, he seemed to have reached a peaceful compromise with them. During our last conversation in June, Jack made several references to the difficulties of his childhood. He never went into specifics, but recalled “my earliest years were exceedingly stressful. Since then I have been very fortunate. But my first six years were…” he trailed off, shaking his head, “… really very troubled.” Just what those troubles were, I never learned. But I have often wondered if, perhaps, those years were part of what inspired Jack to make work that can be characterized, largely, by joy.

Jack Youngerman, Rochetaillee, 1953 (Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

Jack’s career spanned many decades and mediums. As a young man in Paris in the forties, he studied under the figurative painter Jean Souverbie, from whom he learned formal technique in oil painting and gouache. His work from this era demonstrates a clear constructivist influence, employing simple shapes and graphic geometries reminiscent of Calder sculptures. Later, he returned to the United States where he developed his own, more heavily abstracted, style. Showing at galleries around the city, Jack soon emerged as a leading figure in a generation of painters who sought to redefine the terms of abstraction in the wake of the bombastic abstract expressionist movement. In 1959, his work was exhibited in the pivotal “Sixteen Americans” show at the Museum of Modern Art alongside his contemporaries Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ellsworth Kelly. In the late seventies, he began making sculptures, first in fiberglass and later in steel, aluminum, and wood. As recently as last summer, Jack had a show of “Cut-Ups,” small, hand-painted paper collages, at the Washburn Gallery in Chelsea.

From the mid-’60s to mid-’70s, Jack went through a particularly prolific period in which he produced a number of candy-colored acrylic prints that depict botanical forms in an expressive, minimalist style. Of all of Jack’s works, the paintings from these years, which might aptly be called his “floral period,” are among my favorites.

THE PARIS REVIEW NO. 38 SUMMER 1966

Without making overt references, the shapes in these prints recall gestures from nature: the curl of a nautilus shell; a blossom opening; the swoop of a bird’s wing as it takes flight. Rendered in contrasting pastels with sharp edges and clean contours, they possess an affinity with Matisse’s cutouts. One of the prints from this era—a celebration of red, white, and blue—appears on the cover of the Summer 1966 issue of The Paris Review.

In 1971, New York Magazine called him “a master of the simple yet meaningful shape.” And yet, despite their visual clarity these forms are elusive. They evoke nature in motion, a tender poetry whose meaning will never be fully known.

Jack Youngerman, Changes #2, 1970

I am particularly fond of a 1970 lithograph from a series called “Changes” that Jack gifted to my parents as a wedding present. The print, which features an abstract yellow shape dancing across a landscape the color of raspberry sorbet, hung on the wall of my childhood bedroom and, later, my college dorm room. It is an unabashedly joyful image; the shape’s upward gesture seeming to soar skyward, like a helium balloon or the hook of a great pop song, inviting you along with it. Today, it hangs on the wall above my desk. I am looking at it now as I write this and, despite the weight in my chest, can feel its gentle lift.

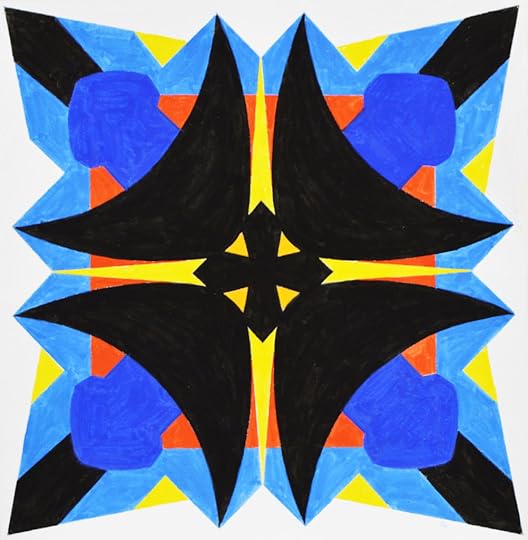

Jack Youngerman, Foil Black II, 2019 (Jack Youngerman Studio and Archive)

In the last years of his life, Jack’s style underwent a significant shift. His most recent work—the paintings hanging on the walls of his studio when I saw him last—were quite different from those that covered the walls on my first visit. His 2016 collection “Spectrum,” a series of large (60″ x 60″), kaleidoscopic paintings, stands out in particular for its bold use of color and stark symmetry. For a painter known for organic forms, these images introduced a hard geometric vocabulary. At first, I was curious about the paintings; they seemed, to me, a little aggressive, almost disorienting, in their contrasts. When I asked about them, he said:

For a long time I had the idea that symmetry and geometric shapes weren’t expressive or emotional; but geometry is at the heart of natural form. People think of nature—plants and clouds and things—as imperfect, asymmetrical, soft. But if you look deeper, on the cellular level there is a pervasive symmetry lying beneath. It has the potential to be quite emotional, too. There is energy in these shapes. There is drama. I want the images to vibrate with that, to have a resonance that is more than just visual … that hums with something … something beyond the image.

Over the past few days, I’ve thought a lot about this answer. While he was constantly in pursuit of new frontiers of abstraction, it seems odd that he would upend his philosophy so late in life. What strikes me most about this statement, though, is that last line: “something beyond.” It crosses my mind that, perhaps, the stylistic changes that attended Jack’s twilight years were evidence of a more interior shift; a slackening of his hold on the rational principles of form that had defined his career—and a growing interest in whatever lay beyond form.

His answer moved me for what it suggested about the enduring depth of his work. What could be more hopeful than to reach the ninth decade of one’s life and still feel that there are new discoveries to be made, that nature’s mysteries are still revealing themselves?

The last time I saw Jack was in November. As I recall, it was a Sunday afternoon. I was packing up my car to head back to New York and Jack was standing outside his studio, apparently talking on the phone. He waved; I waved. I considered going over to chat with him but, glancing at the clock, thought, next time. It was a naive and youthful assumption: that there would, of course, be another time. That there will always be more time.

Cornelia Channing is a writer from Bridgehampton, New York.

The Strange, Forgotten Life of Viola Roseboro’

Center, one of the few remaining images of Violo Roseboro’, in her 20s

Viola Roseboro’ (apostrophe intentional), the larger-than-life fiction editor at McClure’s, haunted magazine offices from the 1890s to the Jazz Age. A reader, editor, and semiprofessional wit, she discovered or mentored O. Henry, Willa Cather, and Jack London, among many others. Today she is nearly completely forgotten.

She could often be seen walking through downtown Manhattan alone, recognizable from her preoccupied step, thick dark hair, gray eyes under arching brows, and her purported resemblance to George Sand. She declined to wear corsets and loved cigarettes, and insisted on getting as much fresh air as possible. Instead of occupying a desk, she liked to pack manuscripts into a suitcase and take them to a bench in Madison Square Park, where in all seasons she could be found smoking, reading, and strategizing about how to develop a protégé.

Roseboro’ forged an identity for herself as a tastemaker, claiming she was “plugged in on a stronger current.” Her originality was specific to the city. She was the kind of New York character later embodied in figures like photographer Editta Sherman (the “Duchess of Carnegie Hall”) and literary agent Roz Cole, who represented Andy Warhol and lived at the Waldorf Astoria for more than fifty years.

Roseboro’ did not leave a comprehensive archive, autobiography, or series of cohesive literary works. The most remarkable thing about her, what is worth trying to conjure even now, was her genius at the spoken word. “She was one of the greatest conversationalists of her time,” said magazine editor S. S. McClure, while journalist Will Irwin placed her, in this respect, “at the very top.” Irwin characterized her as a “kind of feminine Dr. Johnson without his touch of pomposity and without a Mrs. Boswell.” The Johnson comparison crops up again and again. Another friend once said of her, “Anybody who does not acknowledge that something is happening when Viola Roseboro’ is talking is stupid.”

Roseboro’—she fiercely defended that apostrophe, reserving her family name, Roseborough, for her life on the stage—was more zealous than many a missionary. She was utterly convinced that books were all that mattered in life. She offered to give one promising young writer her ideas “as you put cloves into an apple you are going to roast.” And yet, though she championed voices who are today seen as canonical and left behind a literary legacy with which few other readers and editors can compete, she died destitute, rarely leaving her rented rooms on Staten Island.

*

She was born in 1858, in Pulaski, Tennessee. Her parents, fervent abolitionists, named their delicate only child Viola (Vee-ola), and called her the Pet. Her childhood was itinerant, and her tendency toward croup and “nervous prostration” was treated with classic Victorian remedies: beef tea, mustard water, cold-water treatments, and long stretches in the house reading and dreaming of a future on the stage.

After she graduated from a women’s college near home, her mother urged her to write, while her father fretted that she should marry. Instead, she embarked on a “reading tour” of the South, reaching as far as Cincinnati. For her performances, she would walk onstage and recite poems and monologues, demonstrating her facility with both Southern literature and Scotch dialect. Audiences were rapturous. She had her sights on the real stage, in New York, and after she moved to the city around 1882, she acted in at least two plays, Two Orphans and The Lights O’ London. But her health was fragile, and she abandoned acting after a bout of pneumonia. The only thing she would ever have in common with Sarah Bernhardt, she wrote to her mother, was a liking for eating apples in bed.

Her pivot to a literary career was swift and confident. She got a weekly column from the Nashville Daily American, and a press pass that gained her entry to cultural events across the city. Five years after her move to New York, she was contributing to The Century, The Cosmopolitan, The Daily Graphic, and working on her first novel. Richard Watson Gilder, editor of The Century, folded her into his family and circle of friends, and she also frequented artists’ studios, especially stained-glass artist and muralist John La Farge. She was hired as a reader at a literary syndicate run by S. S. McClure, and moved to the fiction desk at his magazine, McClure’s, when it launched in 1893.

At McClure’s, she was known to her colleagues as Rosie. She became close friends with rising investigative journalist Ida Tarbell while both were on staff at the magazine, and Tarbell wrote of her: “By good fortune McClure’s in this period happened upon a reader of real genius—Viola Roseboro—the only ‘born reader’ I have ever known. … Her judgments were unfettered, her emotions strong and warm, her expressions free, glowing, stirring, and she loved to talk, though only when she felt sympathy and understanding. … An unsleeping eagerness to find talent and give it a chance, and secondarily, she said, to enrich the magazine, made every day’s work with the unsifted manuscripts an adventure. If she found exceptional merit that was also suited to McClure’s, she might weep with excitement.”

On one famous occasion, Rosie hurried to the editor with tears in her eyes to insist on the publication of Booth Tarkington’s The Gentleman from Indiana. She struck up a correspondence with O. Henry—the pseudonym of William S. Porter, who was then serving time in the Ohio Penitentiary—and McClure’s featured his first published story under that name, “Whistling Dick’s Christmas Stocking,” in 1899.

To Willa Cather, who joined McClure’s in 1906, Rosie was “my first critic.” Reportedly, on reading the manuscript for My Ántonia, she told Cather, “[You] have told your novel through the wrong character’s eyes, from the wrong point of view. Have you the courage to throw the [manuscript] away, and sit down and re-write it from [Jim Burden]’s point of view, you have a great book.” Cather heeded her words. After its success Roseboro’ often gave the book to visitors, calling it “one of the books of the world” and “wholly perfect.”

Many of Rosie’s authors are no longer read today, but were acclaimed in their time: Josephine Daskam, George Madden Martin, Myra Kelly, Harvey J. O’Higgins. Others, like Rex Beach, are hovering on the edge of total obscurity; still others are experiencing a moment of resurrection, as with recent reissues of Booth Tarkington’s major novels The Magnificent Ambersons and Alice Adams.

Her mentorship could be prickly, and her critiques could be jarringly personal. She did not entertain any notions of separating the writer’s character from the work. As she told one resistant young writer, “It is nonsense to think you can get criticism on manuscripts that is not criticism on yourself—if it has the least depths or is worded so as to be useful.” Some received her involvement with “elation”; others distanced themselves. Her attachments and convictions were often too fiery to appeal for long, and her temper was notoriously short.

Books were Rosie’s life, and there were a handful that formed her foundation. She knew Shakespeare back to front, though her preferred play depended on her mood and stage of life. When she was older, she enjoyed King John especially because, as she wrote to a friend, “I do find the Bastard a most strikingly alive and individualized being, not composed, made by reflection, but delightful principally because he is a kind of miracle of just being born all there, as if Shakespeare did not know what he would say next until he said it to him.” The Iliad and the Odyssey awed her, and as a minister’s daughter, she had entire passages of the Bible by heart.

She loved Whitman, Emerson, and Housman, and whenever anyone came to her she would press a book on them to take away. For Rosie books were the connective tissue that gave relationships meaning, instead of the reverse, as it is for most of us. “About all the companionship I can have now is talk in letters about books that I and my correspondents have both read,” she wrote a friend, when her eyesight was bad.

The one work she cared for most of all, though, was surprisingly unliterary: The Mystic Will, by Charles Leland, a self-help volume focused mainly on willpower and visualization. A kind of prototype of The Secret, it was behind Rosie’s frequent advice to younger people: “Become what you are.”

What was Rosie herself, besides a live wire with a tendency to Wildean pronouncements, if Wilde had been a New Yorker? One could dwell only on her recorded quotes and come away with riches. Of Lillian Wald, celebrated founder of Henry Street Settlement, Rosie remarked, “She is entirely uncorrupted by a lifetime of doing good.” In describing a woman she disliked, she said her hair looked “like rats had sucked it.” Once she remarked that “the greatest defect of modern civilization was the absence of any place where one could adequately insult people. Either you were in the relationship of guest and hostess or you were both guests of someone else, and when you chanced upon each other at the Grand Central Station, there was no time for you were dashing for a train.” (She would, it is clear, have adored Twitter.)

She never abandoned staginess, and friends often reported that her large presence made her seem much taller than her actual five-foot-three. She rarely revealed her true age—“Prenatal memory prompts the reference,” she once told a colleague who asked about a long-past incident. Her electric spirit hardly dimmed in middle age. One young writer described her as a “great table thumper. I have seen her make the silverware at the old Lafayette jump, and the cups at the Brevoort rattle in their saucers!”

Her personal eccentricities multiplied over the years. She lived alone, or boarded in a family home; friends report no knowledge of a romantic entanglement. She dreamed of having a son, however, and periodically “adopted” young men in her circle. Men were her preferred company; she didn’t believe in women’s suffrage. But she didn’t care to be ladylike, she wore cheap, slouchy clothes and rolled her own long, skinny cigarettes. Unconventionally, but mainly because she was so unsuited to cooking, she ate mostly raw food. Some of her quirks put her ahead of her time; she was evangelical about yogic breathing and staying hydrated, and she often carried an old gin bottle full of water around the city. When someone once protested that it couldn’t be healthy to sip old water throughout the day, she angrily replied “Well, damn it, die!”—an expression that rippled outward among her writer friends, a byword for Rosie-ness. In the summer, her preferred way of living was to move to Provincetown, on Cape Cod, where she would sleep on her porch.

After McClure’s floundered in the 1910s, she struggled financially. She became increasingly deaf, and her hands, too, became worn out by the strain of rewriting others’ drafts and sending long editorial memos. Despite her money troubles, she couldn’t resist anonymous acts of charity and frequent social outings. Touched by the story of a spinster who had died in Italy, she paid for the perpetual care of the woman’s grave. Even in her eighties, she would occasionally leave her rooms in Staten Island, take a friend and a pillow, and go downtown to see up to four picture shows at a time. She knew every inch of the Metropolitan Museum, but she didn’t like concerts. Whenever anyone came to her, she entertained them with sherry outdoors if it was fine, or tea by her little Franklin stove if it was cold. Her own favored drink while she was working was a mug of half-coffee, half-chocolate.

She wrote, too—not only letters upon letters in her “huge, blind” handwriting, but short stories and articles. She published the novels Old Ways and New (1892), The Joyous Heart (1903), Players and Vagabonds (1904), and Storms of Youth (1924). Her prominence as a talent whisperer and literary booster meant few reviewers were willing to really criticize her. One confessed of The Joyous Heart, “Candidly, I love the writer, revealed through the book, better than the book itself, albeit it has my warm heart.”

Again and again, others remarked on her regal intensity and expressiveness. Frances Perkins, a labor-activist friend who became the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet, wrote, “Of course I remember her vividly—her conversation, her attitudes, her courage … Miss Roseboro’ was essentially an expressive person. She couldn’t bear to enjoy … things alone, and that is why she would ask me to go along with her because she said, ‘I like to go with you because you enjoy having me talk about it.’” In later life Viola Roseboro’s close friend Gertrude Hall said to her: “To you the gods have granted a boon … to command instant attention and interest the very instant you care to. It is like sovereignty.” The McClure group liked to say her initials stood for Viola Regina.

There is a rumor that when Rosie died, in 1945, she was working on a memoir of the people she’d known and loved titled Let Me Tell You. If it ever existed, the manuscript is likely lost. It’s tantalizing to imagine the coda Rosie would have written for herself, how much she would have exceeded the last line of her New York Times obituary: “She was unmarried.”

Stephanie Gorton is the author of Citizen Reporters: S. S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine that Rewrote America , out this month from Ecco.

February 21, 2020

Staff Picks: Menace, Machines, and Muhammad Ali

Anna Kavan.

Anna Kavan’s short story “Ice Storm” begins in winter, with the narrator leaving Grand Central Terminal to visit friends in Connecticut, to clear her head and make a decision (about what, is left unspecified). They can’t understand why she has chosen to leave her “nice warm Manhattan apartment” for the relentless chill of the country. A similar question: Why would we leave the warmth of a relatively comfortable life to enter fiction like Kavan’s, which is often fraught and frigid? Her masterful lucidity and dispassionate affectation—on display in Machines in the Head, a collection of Kavan’s short fiction, out this week from NYRB Classics—is a journey into the cold to clear your head. Unlike her most popular work, the excellent novel Ice, which skids along planes of disrupted reality, these stories (selected from the span of her writing life) are tighter and more focused. The psychological reality of her characters is rendered sharply: in the title story, the narrator awakens “just in time to catch a glimpse of the vanishing hem of sleep as, like a dark scarf maliciously snatched away, it glides over the foot of the bed and disappears in a flash under the closed door.” Her narrators are often faceless, unnamed, and ungendered; rather than being alienating, this instead asks you to imagine your way inside. Her narratives are uncanny enough to ultimately forge a safe distance, but her characters familiar enough to make one understand anew what it means to wake up and be unable to fall back asleep, or feel unable to decide one’s future. —Lauren Kane

Dan Bejar of Destroyer, christened by Pitchfork as “indie rock’s most lovable curmudgeon,” is the only performer for whom I’ve considered becoming a groupie. Sometimes he takes the stage with an acoustic guitar and a set list scrawled on ripped notebook paper; other times, it’s with a tambourine and beer, leading a full band, saxophone and all, in thirteen-minute anthems. Bejar revels in understated theatricality, which is once again in full bloom on his latest album, Have We Met, released in January. On his 2017 record, ken, Bejar joyously embraced the hearty beats of eighties pop, and Have We Met begins in a similar register, though one a bit more electronic in tone (an aesthetic change of which I was initially skeptical). The music here remains steeped in a literary and geographic nostalgia familiar to Bejar’s listeners; his lyrics depict locales of Vancouver past and present, endowing his highly poetic world with a sense of realism. The track “University Hill” is named for Bejar’s childhood neighborhood, though his recollections of the place seem more haunted than anything. He narrates the scene of some grim execution, but the opening lines conjure the memory of a loving mother or a beloved:

And when they come

to round us up

to gather us up

shadow and air

I think of you standing there

lovely in the light.

As one comes to expect from Bejar, it is as unnerving as it is soothing. —Elinor Hitt

Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury. Photo: Ryan Hafey / Premier Boxing Champions.

The old adage “styles make fights” will be put to the test tomorrow night, when the most proficient boxer in the heavyweight division confronts its most powerful puncher, in the most eagerly anticipated rematch of recent decades. Tyson Fury assumes the role of “boxer,” and not since Muhammad Ali has a heavyweight been so light on his feet or so elusive. An exponent of the “sweet science,” he fights according to boxing’s original tenet: hit and don’t get hit. Meanwhile, his opponent—Deontay Wilder, the World Boxing Council champion—has been touted as the fiercest puncher since Mike Tyson, since George Foreman, or perhaps even in the history of the sport. (A record of forty-three fights and forty-one knockouts corroborates this. Of the two challengers who went the distance, the first, Bermane Stiverne, was knocked out in the first round of their rematch. The second opponent to hear the final bell was Fury, and he ended up on the canvas twice in their first fight.) Observers seem to agree: Fury will either win on points, or Wilder will win by knockout. Fury, ever the contrarian, has predicted a knockout in round two. His new trainer—if we are to believe what we have been told—has been helping him to sit down on his shots, and while it is true that Fury isn’t the hardest puncher in the division, nor is he as feather-fisted as his opponents like to make out. Fury stands six-foot-nine and weighs in at (reportedly) somewhere around two hundred seventy pounds; it would be a mistake for Wilder to think he can walk through Fury’s punches. As they say in heavyweight boxing: if you get hit, you stay hit. On the other side of the ledger, it’s worth noting that Wilder isn’t as flawed a boxer as his detractors like to pretend. It is true that he windmills his punches once he’s got his opponents hurt, but he has a hard, effective jab when he chooses to use it, as well as that fearsome right. Far better “technicians” have tried to land clean on Fury and failed, though Wilder did precisely that in the first fight—not once but twice. This isn’t luck. As Joyce Carol Oates puts it in her book On Boxing: “Life is hard in the ring, but, there, you only get what you deserve.” Should Wilder win, it will confirm what he has told us all along: that he truly is the “baddest man on the planet.” Should Fury win, it will cap a remarkable comeback, following, as it does, his much-publicized depression, weight gain, and years away from the ring. There have been rumblings of some vague difficulty in the Fury camp. Let’s hope there is no truth to this, because tomorrow we’ll see a spectacle all too rare in boxing: the best fighting the best. —Robin Jones

In many of Gustave Roud’s (1897–1976) self-portraits, he appears as a shadow pitched against the fields, or cast toward the men who work the land. However, Roud’s subtle presence, and the quiet composition of these photographs, is no preparation for the ecstatic intensity of his writing, now, for the first time, available in English, in a luminous translation by Alexander Dickow and Sean T. Reynolds. In his prose works Air of Solitude and Requiem, Romandy is a place of rapture and reverie, through which he wanders alone in awe, like an exile in Eden. “What have I been doing here for hours on end among the snares of time and absence, laughable summoner of shadows, a shadow myself in the kingdom of my dead,” he wonders. Every scene becomes an unwitting show: the glow of a man’s bare chest in the sun; the song of a cuckoo; the unfurling of a flower. The laborers shape the scene, as Roud, the sole spectator, gazes on at the theater of the seasons, all words “undone like a vain foam.” —Chris Littlewood

Perhaps no other rap album bottles an aesthetic as well as Mobb Deep’s masterpiece The Infamous, which I’ve found my way back to again this week, as I have many times over the course of my life. The second LP from the rapper Prodigy and the MC-producer Havoc plays out in New York’s Queensbridge public-housing development, which in Mobb Deep’s music becomes a kind of perverse snow globe: it is seemingly always winter, not a single soul is to be trusted, and the slightest misstep can get you killed. These stakes are established right from the start; a promise to shoot “in all the shows and even at the hoes” on the first track is underscored almost immediately by “The Infamous Prelude,” a two-minute intermission wherein Prodigy humorlessly affirms that none of his tough talk is empty bluster: “There’s a good chance your ass is gonna get shot, stabbed, or knuckled down—one out of the three.” This unrelenting seriousness, this haze that never lifts, is exactly why I love The Infamous. Prodigy, especially, plays the dead-eyed street nihilist well; he is effortlessly menacing, clicking threats together like Lincoln Logs. On “Shook Ones (Part II),” he taunts his opponents: “I can see it inside your face: you’re in the wrong place / Cowards like you just get their whole body laced up / With bullet holes and such / Speak the wrong words, man, and you will get touched.” The thing about a snow globe, though, is that you can’t escape. There is seemingly no way out for our protagonists, who live one day at a time, dodging corrupt cops, piecing together jobs, and finding relief in substances and revenge: “As long as I send your maggot ass to the essence,” Prodigy raps at one point, “I don’t give a fuck about my presence.” The production throughout the album is appropriately dour: crackling piano loops, unplaceable sirens, and drums that hit like a series of blows to the head. I’ve yet to find a more perfect marriage of beats and rhymes, of gleam and grit, of pure art and utter hopelessness. —Brian Ransom

Mobb Deep.

National Treasure, Elizabeth Spencer

A PORTRAIT OF ELIZABETH SPENCER FROM THE FILM LANDSCAPES OF THE HEART.

When she died last December at the age of ninety-eight, the novelist Elizabeth Spencer was described as “a national treasure.” The author of nine novels, eight story collections, a memoir, and a play, she had mastered every mode of literary fiction. Her first novel appeared in 1948 and her most recent book in 2014. On the page, Spencer makes what’s technically difficult seem unusually clear, then psychologically inevitable. From the start, her voice was praised for its tonal nuance, its stratospheric empathy. Spencer had the gift for infusing social situations with a bullfight’s fatality.

She was born in 1921 in the waning plantation culture of Carrollton, Mississippi. Senator John McCain was her second cousin. She grew up owning a horse and believing in ghosts. The subject of race was inescapable in the Jim Crow South and it figured strongly in her fiction.

At her career’s very start, Elizabeth Spencer won the admiration of wise older writers, fine judges of talent like Robert Penn Warren and Eudora Welty. They identified her depth of insight, her fellow feeling, and the warm richness of her character.

A Guggenheim Fellowship in 1953 allowed her to depart Mississippi for Italy. There she met and married John Rusher, an Englishman from Cornwall. The couple moved to Montreal in 1956. I first encountered Spencer when I published my first story at age twenty-six. She sent me a letter praising what I’d done. Beginner’s luck on all fronts. When Spencer became writer in residence at the University of North Carolina in 1986, she took up residence in Chapel Hill, where we became neighbors.

Though she was my parents’ age, I always considered her a contemporary. I admired her irreverent wit, her forgiving nature, her unsentimental love of animals. Elizabeth had some essential confidence that made her wonderfully receptive to others. Thin, she wore clothes it seemed she’d always owned. She was beautiful but—as a lapsed tomboy—didn’t seem to have noticed yet. She was an old hand at receiving and flirting with “gentleman callers,” and I was quite happy to be one. Her loyalty to friends was returned by a community that quietly adored her.

Spencer’s fiction reveals a trenchant eye for what’s questing and ludicrous and therefore fully human. She has the keenest ear for all that people try to say but rarely speak aloud. She proved herself an indispensable witness to the difficulties of having a home and then leaving it, to the struggles of smart, sexually alive young women trying to find their way in the world. She had an aristocrat’s insouciant talent for being talented. She treated others as her equals, though few actually were.

Her 1956 novel The Voice at the Back Door offered a prophetic overview of the Civil Rights era. The work chronicles the twisted politics surrounding a small town’s execution of black citizens. The New York Times pronounced it “practically perfect.” Editorial pages in Mississippi rebuked her as a traitor. The book was unanimously chosen by the Pulitzer jurors, but its governing committee chose to give no prize in 1957. Spencer’s candor about virulent segregationist racism is sometimes cited as the reason her award was withheld. Four years later, in 1961, To Kill a Mockingbird—based on a similar racial crime and clearly influenced by Spencer’s book—told its story from a child’s perspective and won the Pulitzer.

In 1962, Spencer’s long story “The Light in the Piazza” was filmed with Olivia de Havilland. And in 2005, the work became an opera of great freshness and force, winning six Tony Awards. It has become a staple of world theater.

In The Paris Review’s Art of Fiction interview, Spencer was asked if she had ever adjusted to leaving the South. She responded, “Oh, no, I can never ‘adjust’ to losing anything I love. You have to count on memory more and daily rhythms less. But memory is a muse, after all, a girl with a vital life of her own.”

Let it be stated: as great as Elizabeth Spencer will remain on the page, she equaled and surpassed that as a friend.

Allan Gurganus’s books include Local Souls and Oldest Confederate Widow Tells All. Winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, Gurganus is a Guggenheim Fellow and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

February 20, 2020

Feminize Your Canon: Inès Cagnati

Our column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.