The Paris Review's Blog, page 180

March 10, 2020

One Word: Bonkers

photo courtesy Harry Dodge

1. I want now to investigate bonkers (a word that strikes me as germane to our times), but the word busted (also a fine word) keeps popping into my head. Not at all interchangeable, busted suggests mechanicity and palpability while bonkers seems to indicate something mental and systemic. But they inhabit the same register; both words are punchy (is that a register or a tone?) and both words suggest mitigatability—they’re carrying little hope suitcases. Do you feel that? I wrote the word busted the other day to describe birds I saw in a book of photographs, impossibly bent-up birds captured during liftoff, during landing—weird contorted flight surfaces, tangled wings like flat hands, ruddering volte-face, cartoony dustups apparently necessary to occasion real-life avian landings. I like the word busted—not shattered, not completely demolished. BUSTED!, as in currently unusable: an ugly leg thrown out of the tub too wounded even to soak. But you know what? I’m a repairman. I’m a research assistant! Give me what is busted and I’ll take a look. Here. See how in the break or the torn area, let’s call it the rupture, something truly bent or baffling is sometimes lined with an undeniably fecund matrix, raw lamina where new stuff is now compelled to grow?

2. The word bonkers entered the dictionary in 1945, accompanied by other newly minted words, such as: A-bomb, allomorph, antibias, blip, chugalug, extraliterary, fissionable, gadzookery, honcho, koan, Medal of Freedom, mom-and-pop, radiomimetic, squawk box, superorgasm, unfazed, up-front, whing-ding, and zingy. I know, what a year, right? What a year for crazy words. (That last sentence is absolutely a viable segue to poetics.) Poetics is a word I tend to use as synonymous with anything unquantifiable: objects (things, ideas) that defy translation or any kind of re-rendering. Unquantifiable bosh=poetics: a license to glittering specificity, something uncategorizable that nonetheless exists. The poetics of bonkers is a tautology. Bonkers is berserk but in weirdly large hunks, big pixels. Bonkers is video noise like hail. Bonkers sounds British. Bonkers is a word used wholly positively only in the context of discussing art. Bonkers has amplitude, gleam—it is not like a puddle, it is not evidentiary of despair, but its use rather indicates (bravado through grim humor?) a reserve of defiance (think: the mouse flipping off the swooping homicidal eagle in the seventies cartoon). As it turns out, bonkers is a refusal of despair! When something is “bonkers” it is unacceptable but somehow not lethal to l’esprit de corps and thus connotes afterness: life on the other side. An online news-rag the other day published the headline, “Five of the Most BONKERS Arguments from the White House.” Or, maybe it was, “Bonkers White House Post-Impeachment Speech Explained.” (I’m doing this from memory, believe it or not.) These rotten logics distend our psyches with an unwelcome pandemonium and now our heads seem strained, about to pop! We’re trying to track it all, we’re making notes! (“we” as in hobbyist political scientists), which distracts from the gathering and crashing wave of criminality and corruption. (Tyranny is built on a manipulation of the fear of uncertainty, aka fear of death.) Bonkers is outside, as a rule or at least frequently; which is to say that when the word bonkers shows up on the tip of your tongue, from the literary alluvium, chances are you’re referring to the “not-me.” Something quixotic and vertiginous—and also vaguely humorous—taking place outside your skin. When you say bonkers you’re pointing your finger.

3. In conceiving his philosophically minded taxonomy of games Man, Play and Games, Roger Caillois coined several terms, including alea, which appertains to games of chance; agon, relevant to games of skill; and ilinx, which, in Caillois’s cosmology of play, refers to a state of transport: pure vertigo and its related ecstasies. Caillois does not define ilinx as an apex state of disarray but—rather simply—happening lostness, a temporary disintegration of perception. He writes that games based on the pursuit of vertigo, such as roller coasters, whirling and spinning games, inebriation, et cetera, generate from a common human urge to seek disorientation for its own sake. Players (and who’s not?) attempt to “momentarily destroy the stability of perception” in order to “inflict a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind.” As I see it, and building off Caillois, the pleasure here lies not only in the fleeting (but thorough) deliverance from a perhaps lusterless chronicity but also in the erotics of “wow-this-is-totally-crazy-but-I-got-this”—which is to say: challenge followed by triumph. (Here, stolidly, I’ll interrupt myself in order to point out that I’ve had three people read this brief discursion and exactly none of them agreed that the pleasure of self-induced vertigo is always and necessarily wrapped in the pleasure of finally righting the ship. This series of responses taken en bloc suggests that the strong correlation is peculiar to me alone.) Caillois’s term ludus denotes the primitive desire to gather one’s organismic resources in order to settle problems sought for just such a purpose: the joy of solving them. (Though this relationship, ilinx to ludus, seems at first glance to be inversely proportionate, it is infinitely, open-endedly lush.) By setting obstacles into motion, we (gentle bedlamites) create opportunities to deploy the full or partial set of (too often occulted) skills we already possess (or immediately develop or suddenly expose). The practice of wrestling chaos into order is a kind of amusement: the pleasure of the gusty puzzle (my term)—because according to Caillois, not just any puzzle qualifies as ilinx (though this seems to me debatable), just the most conceptually or physically turbulent of them. (Video game developers have, by virtue of a surge in resolution, recently developed better ways of producing an experience of vertigo by generating the sensation of high-speed movement—often enhanced by creative effects that are called, um, speed haze. The Millennium Falcon’s hyperspace is an old version of this.) Ilinx is bonkers come indoors: inoculation, familiarization, a way to safely entertain chaos.

4. Bonkers is a mad answer, too—obliquus interruptus: a clown honking a horn riding a unicycle that caroms through a standoff between protesters and cops (makes laughter happen), or you abruptly put on a wig while hotly debating curfew with your adolescent son. As action or objection, bonkers (different again and suggested here suffused with a mote of gravitas) might be deployed oppositionally—shock and awe response to madness all around. (Or emotional pain.) A battering ram of surreality hauled out for a critical self-defense; you’re busted, say: Crazy? Meet crazy. Bonkers is meritorious every now and then, when it answers obliquely those questions asked with hammers, with nails.

5. I appreciated today that I thrill to a challenge (shocker); if I stay in the ring I get to flex (my son says, Weird flex, bro). Thrill is the wrong word. I thought just now, “Bonkers Life.” And for a split second, I was [sad-face emoji] that I have FORM and FLOW tattooed on my fingers instead of BONKERS LIFE tattooed over my knuckles, thumb, palm, and fingernails.

Harry Dodge is the author, most recently, of My Meteorite: Or, Without the Random There Can Be No New Thing.

March 9, 2020

On the Timeless Music of McCoy Tyner

McCoy Tyner in April 2012 [Photo: Joe Mabel]

There are many ways to understand the passage of time—it’s not just one thing after the next, the pinhead of the present gnarling the flesh of your foot as you try, impossibly, to balance upon it. Not just peering through the mist of memory. Not just cutting through the ice ahead. Time moves back and forth, slows down, speeds up, it eddies—it does a lot of eddying. It concentrates itself in one moment and becomes diffuse and vague in another. We’re always in the present, though we can never quite get there, nor can we leave. All of this is what the music of McCoy Tyner, who died on Friday at the age of eighty-one, teaches, though as soon as one tries to paraphrase music in anything other than other music, it’s robbed of some of its magic and much of its meaning.

Tyner was one of the defining musicians of the jazz period that began in the early sixties and which, I’d argue, we’re still in: pure art music that renews its inspiration in the the last hundred-plus years of pop music. As the pianist anchoring the classic John Coltrane quartet, Tyner’s instantly recognizable style—pendular, percussive, full of melodic flights and returns—created, hand in hand with drummer Elvin Jones, the landscapes across which Coltrane’s solos famously and fathomlessly ranged.

I’ve been gratefully lost for years somewhere between the interminable vamp of the 1961 studio recording of Coltrane’s rendition of “My Favorite Things” and the pounding sinews of Tyner’s 1976 solo track “Fly with the Wind.” The latter isn’t fusion, isn’t exactly jazz, but is all Tyner: intellect, melody, and abandon. Tyner’s art has guided my imagination, and now that he’s gone, and because the meaning of music is so slippery, I want to take a moment to say why.

I think I saw Tyner perform live twice: once at an outdoor concert at Lincoln Center, where he was a vigorously pulsing dot in the distance, and later at the Blue Note downtown, where he was only a few feet from me and I could stare, mesmerized, at his thundering left hand. He raised it high over the keyboard, above his head, before sending it hammering down, blasting open the time that followed, filling the bars with cascading showers of high notes. That, more than anything else, was the definitive Tyner gesture: opening the musical measure with that heavy left-hand chord, which was simultaneously a drum, a cymbal, and a signal to the rest of the music about where it should begin and end; more than any pianist save Cecil Taylor, Tyner understood his instrument as a series of pitched drums.

How, from that high distance, did his hand know where to find the chord he wanted when it slammed back down to the piano? But that is the least of his miracles. As Johnny Cash said, “Your style is a function of your limitations, more so than a function of your skills.” That’s a humbling truism about all creative work, but the limiting factors are different for each art form. Writers are stuck with a particular vocabulary, a language, and the deep memory of the kinds of sentences they heard growing up. A singer is stuck with the particular resonating chamber that is their body. Tyner was perhaps blessed by being stuck with those catapult hands and an unwavering conviction that rhythm and melody should tell a story, enact a high drama. It can be cheesy at times, but mostly I find I agree with—am glad to be a part of—the story his music tells.

It’s enough, more than enough, really, for an artist to simply find a voice, to chisel it out of the noise and to keep it ringing clear across a lifetime. Though he tried lots of modes and moods, Tyner began his professional career in the early sixties as a fully formed artist, and his last albums, from the aughts, are not unlike his first. From the beginning, his musical voice—seeking, earnest, exciting—was his alone. There was no one like him, except for almost every pianist after him. So many of the greats are leaving the earth in this dark time when we need them most. But his music is ever present, alive in so many fingers, awakening so many ears, swinging back and forth and thundering through time.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the digital director of The Paris Review and the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers: Poems and We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress.

Little Fires for the One Who Was Lost

Alejandra Pizarnik’s work has long served as a touchstone for Latin American writers. The late Argentine poet has been cited as an influence by everyone from Roberto Bolaño and Julio Cortázar to Octavio Paz, who described her writing as exuding “a luminous heat that could burn, smelt, or even vaporize its skeptics.” But this fervor didn’t reach the English-speaking world until some four decades after her death, with the publication of her collection A Musical Hell in 2013. Since then, translations of five more collections of her poetry have appeared to near universal acclaim, and several of her poems have been published in The Paris Review. Ugly Duckling Presse has recently published A Tradition in Rupture, which presents Pizarnik’s critical writings in English for the first time. In the excerpt below, she ponders the nature of poetry and the pain of revisiting past work.

Alejandra Pizarnik.

Poetry is where everything happens. Like love, humor, suicide, and every fundamentally subversive act, poetry ignores everything but its own freedom and its own truth. To say “freedom” and “truth” in reference to the world in which we live (or don’t live) is to tell a lie. It is not a lie when you attribute those words to poetry: the place where everything is possible.

In opposition to the feeling of exile, the feeling of perpetual longing, stands the poem—promised land. Every day my poems get shorter: little fires for the one who was lost in a strange land. Within a few lines, I usually find the eyes of someone I know waiting for me; reconciled things, hostile things, things that ceaselessly produce the unknown; and my perpetual thirst, my hunger, my horror. From there the invocation comes, the evocation, the conjuring forth. In terms of inspiration, my belief is completely orthodox, but this in no way restricts me. On the contrary, it allows me to focus on a single poem for a long time. And I do it in a way that recalls, perhaps, the gesture of a painter: I fix the piece of paper to the wall and contemplate it; I change words, delete lines. Sometimes, when I delete a word, I imagine another one in its place, but without even knowing its name. Then, while I’m waiting for the one I want, I make a drawing in the empty space that alludes to it. And this drawing is like a summoning ritual. (I would add that my attraction to silence allows me to unite, in spirit, poetry with painting; in that sense, what others might call the privileged moment, I speak of as privileged space.)

They’ve been warning us, since time immemorial, that poetry is a mystery. Yet we recognize it: we know where it lies. I believe the question “What does poetry mean to you?” deserves one of two responses: either silence or a book that relates a terrible adventure—the adventure of someone who sets off to question the poem, poetry, the poetic; to embrace the body of the poem; to ascertain its incantatory, electrifying, revolutionary, and consoling power. Some have already told us of this marvelous journey. For myself, at present, it remains a study.

*

If they ask me who do you write for, they’re asking about the poem’s addressee. The question tacitly assumes such a character exists.

That makes three of us: myself; the poem; the addressee. This accusative triangle demands a bit of examination.

When I finish a poem, I haven’t finished it. In truth, I abandon it and the poem is no longer mine or, more accurately, it barely exists.

After that moment, the ideal triangle depends on the addressee or reader. Only the reader can finish the incomplete poem, recover its multiple meanings, add new ones. To finish is the equivalent, here, of giving new meaning, of re-creating.

When I write, I never imagine a reader. Nor does it ever occur to me to consider the fate of what I’m writing. I have never searched for a reader, neither before, nor during, nor after writing the poem. It’s because of this, I think, that I’ve had unforeseen encounters with truly unexpected readers, those who gave me the joy and excitement of knowing I was profoundly understood. To which I’ll add a propitious line by Gaston Bachelard:

The poet must create his reader and in no way express common ideas.

*

Nothing in sum. Absolutely nothing. Nothing that doesn’t diverge from the everyday track. Life doesn’t flow endlessly or uniformly: I don’t sleep, I don’t work, I don’t go for walks, I don’t leaf through some new book at random, I write badly or well—badly, I’m sure—driven and faltering. From time to time I lie down on a sofa so I don’t look at the sky: indigo or ashen. And why shouldn’t the unthinkable—I mean the poem—suddenly emerge? I work night after night. What falls outside my work are golden dispensations, the only ones of any worth. Pen in hand, pen on paper, I write so I don’t commit suicide. And our dream of the absolute? Diluted in the daily toil. Or perhaps, through the work, we make that dissolution more refined.

Time passes on. Or, more accurately, we pass on. In the distance, closer every moment, the idea of a sinister task I have to complete: editing my old poems. Focusing my attention on them is the equivalent of returning to a wrong turn when I’m already walking in another direction, no better but certainly different. I try to concentrate on a shapeless book. I don’t know if this book of mine actually belongs to me. Forced to read its pages, it seems I’m reading something I wrote without realizing I was another. Could I write the same way now? I’m disappointed, always, when I read one of my old pages. The feeling I experience can’t be precisely defined. Fifteen years writing! A pen in my hand since I was fifteen years old. Devotion, passion, fidelity, dedication, certainty that this is the path to salvation (from what?). The years weigh on my shoulders. I couldn’t write that way now. Did that poetry contain today’s silent, awestruck desperation? It hardly matters. All I want is to be reunited with the ones I was before; the rest I leave to chance.

So many images of death and birth have disappeared. These writings have a curious fate: born from disgrace, they serve, now, as a way to entertain (or not) and to move (or not) other people. Perhaps, after reading them, someone I know will love me a little more. And that would be enough, which is to say a lot.

—Translated from the Spanish by Cole Heinowitz

Alejandra Pizarnik (1936–1972) was a leading voice in twentieth-century Latin American poetry. Six books of her poetry have been translated into English: Diana’s Tree, The Most Foreign Country, The Last Innocence / The Lost Adventures, A Musical Hell, Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962–1972, and The Galloping Hour: French Poems. She died in Buenos Aires, of an apparent drug overdose, at the age of thirty-six.

Cole Heinowitz is a poet, translator, and scholar based in New York. Her books of poetry include The Rubicon, Stunning in Muscle Hospital, and Daily Chimera. She is the translator of Mario Santiago Papasquiaro’s Advice from 1 Disciple of Marx to 1 Heidegger Fanatic and Beauty Is Our Spiritual Guernica and the cotranslator of The Selected Late Letters of Antonin Artaud. She is the director of the literature program at Bard College.

From A Tradition in Rupture: Selected Critical Writings , by Alejandra Pizarnik, translated from the Spanish by Cole Heinowitz, published in December 2019 by Ugly Duckling Presse.

March 6, 2020

Staff Picks: Cinema, Sebald, and Small Surprises

Still from And Then We Danced

Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire captured critics’ hearts, and seemed a sure shot to capture mine. An acclaimed French lesbian film? Made for me! And yet, though I did like looking at Adèle Haenel’s incongruously contemporary face in period garb, the overblown, gestural romance left me un-aflame. “Do all lovers feel that they’re inventing something?” Heloise asks Marianne before they first sleep together, and I wished that something more precise, more personal, were being invented. I found that specificity in a different international gay film, And Then We Danced, which follows a delicate-boned dancer as he tries to keep his hands from fluttering during traditional Georgian dance, his only path out of a country where he cannot survive. Shot in four weeks on a minuscule budget, the film received a standing ovation at Cannes. In Georgia, it was met with such violent far-right protests that it closed after three screenings, but a queer Georgian youth movement has mobilized around the film, and its soundtrack, as a beacon of hope. The movie’s portrayal of first love made me bite my lip, but even more vivid were the moments of tenderness between two brothers, between grandparents and grandchildren, and the spaces the camera inhabits in Tbilisi, from nightclubs to cramped apartments to ballrooms. It’s a love letter to Georgia that asks simply: Love me back. —Nadja Spiegelman

I spent much of December working with Nathaniel Mackey and Cathy Park Hong on Mackey’s Art of Poetry interview, which is in our new issue (online now, on newsstands Tuesday). In working on the manuscript across winter’s darkest days I had a sensation not unlike that accompanying opening up an Advent calendar. Behind one paper door was the poetry of Henri Coulette, behind another was John Coltrane—both of which were familiar to me, as Michael S. Harper made Coulette required reading for his undergraduate seminars, and Coltrane, well, I was carrying a coffin-size saxophone case around Seattle at age twelve, of course I know my Trane. But other doors opened to new-to-me delights—Mackey’s epistolary novels, which are but a grace note in this Art of Poetry interview, revealed a rabbit hole, and I eagerly devoured N’s letters in Late Arcade. The epic poem Paterson wasn’t new to me, but after reading Mackey’s description of its landscaping, I’ll never look at William Carlos Williams the same way again. Behind another door was Cathy’s new essay collection, Minor Feelings, which I started one Friday night and didn’t look up from again until it was done on Saturday evening. It’s a tremendous book of essays, inquisitive and honest and necessary. It seems I’ve just picked four books and a record, which is to say I’m actually pointing to a style of creative exploration that Mackey has internalized and deployed to great effect across his storied career. One part explorer, one part magpie, he weaves his work from many threads, and that curiosity is catching. As for me, I’m keeping those doors open all year. —Emily Nemens

From Sam Youkilis’s Instagram

In the hellscape of Instagram lies a savior, Sam Youkilis. In a simplistic way, Youkilis could be described as a travel photographer, but that moniker does no justice to breadth of his work. Yes, he’s more often than not in a beautiful place, eating gorgeous food and drinking perfect wine, but he is also capturing the soul of the landscape and the people who inhabit it. A great deal of his work is showcased in the Stories feature of Instagram, where he posts moving (in both senses of the word) portraits, often in curated series. Recently he has been posting videos from Chefchaouen, a city in Morocco known for its buildings in varying shades of blue. When you click on the geotag for Chefchaouen, a grid appears, dappled with travel influencers posing cross-legged on blue steps. In stark contrast, one of Youkilis’s posts features two little boys arm in arm running down a cerulean alleyway. Often it feels like Instagram’s sole purpose is to elicit envy, and yet I, someone prone to jealousy, never feel spiteful looking through Youkilis’s posts. His ability to capture the purest moments of everyday life assures me that if anyone deserves to be somewhere exciting and new—it’s @samyoukilis. —Eleonore Condo

There are no huge surprises on this new album from jazz legend Charles Lloyd, 8: Kindred Spirits, Live from the Lobero—it sounds a lot like Lloyd’s recent live albums—except the usual surprises that come with excellent, sinuous improvisation, and the presence of once-rising, now-risen star Julian Lage on a guitar that is alternately icily cutting and warmly resonant, and the organist Booker T., who quietly adds dimensions. Lloyd is one of the last active musicians from his great mid-’60s generation, and his round tone on sax and distinctive phrasing, which alternates between long, slow notes and sudden crunched runs, is recognizable from a mile away. His music moves effortlessly between a kind of hip profundity and a funky strut. He’s backed here by longtime bandmates, including Eric Harland, one of the best drummers alive, and pianist Gerald Clayton, who comes to the forefront of this music. There’s also a very expensive limited-release deluxe edition that includes an additional hour of music that is as wonderful as the rest, except for a rather ham-fisted vocal number called “A Song for Charles” (“Charles is a gift to the world/to me and you …”), which most listeners will want to skip over. No huge surprises, but, actually, lots of little ones, particularly in the twenty-minute version of Lloyd’s warhorse “Dreamweaver,” which opens the album. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Nick Mauss, Compilation, 2020 (© Nick Mauss, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and 303 Gallery, New York)

Nick Mauss, though a visual artist by trade, is a scrupulous scholar of modernist dance. With each new work, he tests the limits of his form, capturing, in paint, the ephemeral nature of bodies in motion. Mauss is no stranger to Chelsea, having made a home at both the Whitney and 303 Gallery, where his latest solo show is on view through April 11. In a new collection of sketches and paintings, as in his other work, Mauss pays homage to the mid-century aesthetic. His architectural compositions recall the neoclassicism of Balanchine and Stravinsky. And his tender representations of the male body evoke the poetry and portraiture of Frank O’Hara and Fairfield Porter, respectively. Upon entering through a painted door, the viewer is immediately disarmed by a sketch of nearly life-size nudes in foreshortened perspective. These figures, rendered in ink on enamel paper, appear unfinished. Like others in the gallery, the work seems as if it has been torn from an oversize sketchbook. Neighboring pieces are even stained with coffee and ring-shaped marks where cups of paint once rested. The art, seemingly a record of Mauss’s own dynamic process, brings to mind dance notation. I left the gallery imagining the artist at work, in motion, as much a dancer as he is a choreographer. —Elinor Hitt

My memory has always been bad, though the past two years or so it’s been dreadful. Sufficiently poor that, when I’m tired, it seems that the blanks extend to the most common of words. If severe, the forgetting of words is called anomic aphasia. Or so my doctor told me when—quite blithely—she dismissed my concerns out of hand. (“No, you don’t have it. Get some sleep.”) Others have different names for the condition: in my conversations with the Review’s digital director, he has referred to it as “middle age.” Regardless of the nomenclature, the rewards of the condition are few, and the frustrations are many. But my obsession did recently draw me to a collection of interviews with, and essays on, W. G. Sebald, titled The Emergence of Memory and edited by Lynne Sharon Schwartz, a highlight of which is Sebald’s interview with Michael Silverblatt. I had first listened to this episode of Bookworm one evening, years ago, in a small kitchen in Paris while I cooked dinner, my laptop perched precariously on top of the fridge, and the conversation between these two respectful, calmly erudite men stayed with me. Early on, Silverblatt describes the manifestation of the Holocaust in the elegiac Austerlitz as a “silent presence being left out but always gestured toward.” To this Sebald responds: “Your description corresponds very much to my intentions.” It is an inconsequential reply, I suppose, but something about it seemed so simple, so accurate, and so very full of him. I remember how formal Sebald seemed, almost weary, though still friendly and engaged. I remember, too, his tones as he spoke that phrase, and have often repeated it to myself over the years, though I don’t precisely know why. It was reassuring to see the sentence reproduced on the page. And not only because I had remembered it correctly. —Robin Jones

The Envelope

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces the moments and seasons before her daughter leaves for college. The column ran every Friday in November and January. It returns through March, and then will again in June.

My daughter, Indie, has been on a college tour her whole life—riding in her stroller through the snow in Boulder; rolling down a hill outside the English building in Utah; peering from the passenger window while football fans swarm sidewalks toward a blue field in Idaho; sitting under my office desk in Oklahoma, silently passing me notes or drawing pictures; climbing the three stories to my office in northern New York to race her Razor on the shiny hallway floor; spinning in the revolving doors of a building in Chicago as the El barrels overhead; snapping photos of red-tile roofs in New Mexico; thumbing through the books in my office on a Texas campus covered by trees.

Indie was the first student to show up for kindergarten. Her teacher pointed to a ball of clay on a table, and Indie immediately sat down. I slipped out the door but stood just beyond it, watching her play through the window. Days later, she hopped into the car holding something small and misshapen, painted purple and green. “Here,” she said, handing it to me, “I made you a bowl.”

In first grade, Indie asked if school could be her space. Because it’s always been the two of us, I understood it was important for her to have a world she did not have to share, one she could move through alone. How young she was to ask for this, but as the years have disappeared behind us, I recognize it as a claim my daughter has always made for herself. She will do it alone. I agreed not to interfere unless I had reason: a call from a teacher, a pattern of bad grades, missing work.

I kept my distance, allowed Indie her own.

Last November, she attended a visitation day at a university where I once taught. Out of all the places we’ve lived, this school stands out as her favorite. I let her go alone. From Dallas, two flights—one to Boston, then a nine-passenger plane farther north. If I had climbed in my car and followed, I would have driven 1,660 miles.

When I was in second grade, my teacher sent a note home requesting a meeting with my parents. I handed over the sweaty note to my mother after waiting as long as I could before bedtime. When she read the note to my father, he sat forward in his chair: “I raised my daughter to be sociable and to have a personality.” The next day, my mother walked into Nat Williams Elementary alone.

All through elementary school, the notes from Indie’s teachers arrived, tucked into bright folders. The phone rang after dinner or during planning periods. Teachers leaned into my car’s window after school: “Are you Indie’s mother? Do you have a minute?” At the third grade parent-teacher conference, Mrs. Brown showed me a desk set apart from the rows, a desk suffocatingly near her own. “That,” she said, pointing, “is Indie’s desk.” Indie, it turns out, had inherited my behavior. I inherited my father’s response to it.

Every note, every call, every concern from Indie’s teachers was about her talking in class. In seventh grade, when the Spanish teacher called to complain about Indie’s laughter, I sat for a moment, then asked, “You’re calling me because she’s laughing?” That night, I told Indie we had six more years of this to go. But the Laughing Phone Call turned out to be the last one.

Indie submitted applications to five universities, completing every step of the process on her own, including her selection of schools. She checked email first thing every morning. She walked to the mailboxes at our apartment complex every afternoon, and when she got home late from band rehearsal or work, she’d walk through the door, “Did you check the mail today?” She was accepted to four of the five universities. She was holding out for that last one, the only one she really wanted.

In an attempt to distract her, I started adding a simple sentence to the end of all of my texts to her, followed by an emoji.

Here is a train.

Here is a salad.

Here is a door.

Here is a pen.

Here is a taco.

Here is a television.

She loved it, and her friends did, too. When she texted from English class that her best friend had been accepted to his dream school, I replied, “Here is a highway. To Stillwater.”

Imagine going to five schools in seven years. Imagine the conversation you know is coming because of the way your mother sits down on the couch, the way she holds herself and her face, the way she begins, “I got an offer from a school—in Utah, Idaho, Oklahoma, New York, Chicago, New Mexico, Texas.”

Now imagine after all those states and moves that you get to pick the state, the school, and stay there.

Imagine that wait.

The morning email checks.

The walks to the mailbox.

Two weeks ago, the bells of the apartment office rang as I stepped inside to tell the manager our garbage disposal wouldn’t churn. He held up a finger and disappeared into the package closet. When he stepped out, he handed me a stiff, oversize envelope. The date of its arrival, six days before, had been scribbled in the bottom corner in black sharpie. I rushed out, the bell ringing behind me as I snapped a photo of the insignia in the left corner, the university 1,660 miles away. I sent it to Indie. And then I turned the envelope over and read the words on the back:

Think about how far you’ve come—And how far you’re about to go.

We hide our small sorrows away.

We search for a way to carry them.

Here is a bowl.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

Cooking with Cesare Pavese

In Valerie Stivers’s Eat Your Words series, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

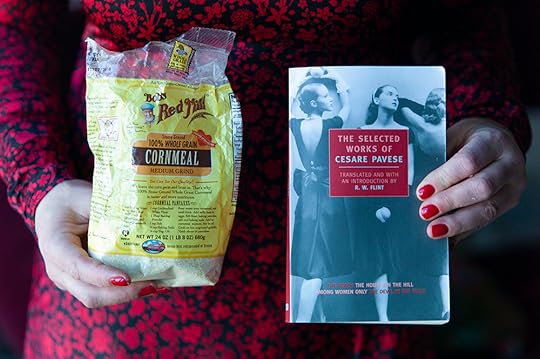

Characters in Pavese’s work follow the unchanging traditions of the countryside, including eating much polenta, easily made from medium-grind cornmeal, like this.

Film buffs will know the Italian modernist writer Cesare Pavese (1908–50) because his novel Among Women (Tra donne sole) was the source for Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Le Amiche. But I came across his work in the unlikely location of a cookbook, English food writer Diana Henry’s How to Eat a Peach. Pavese, Henry writes in a chapter entitled, “The Moon and the Bonfires (and the Hazelnuts),” was born in Piedmont in Northern Italy, and his native landscape was “almost a character” in his work. She quotes him as saying that, if you live there, you “have the place in your bones like the wine and polenta.” How to Eat a Peach is formatted as menus drawn from Henry’s travels and interests, and her Pavese-Piedmont menu, inspired by the 1949 novel The Moon and the Bonfires, offers an ox cheek stew, white truffle pasta, and a hazelnut-strewn chocolate cake. She suggests an accompaniment of the local Barolo or Dolcetto wine.

This was intriguing to me, and more so because Henry’s book had already been something of a journey. It falls into a category that’s strangely frequent in my life: cookbooks that at first I don’t use, but then I do. The book is beautiful, broody, and atmospheric. I certainly imagined myself cooking from it, but in practice the menus felt obscure and the titles too specific and unalluring—“Darkness and Light: the Soul of Spain” or “I Can Never Resist Pumpkins.” Is that really what I want for dinner? Do I have to cook the whole menu? How to Eat a Peach ended up on the shelf where it remained, mocked occasionally by my children for having a stupid title, until months later I did what I should have done in the first place and read the introductory essays. Henry’s writing is vivid, personal, and seductive, and contains gems like the introduction to Pavese. Now that I know the backstory, I do want “the Moon and the Bonfires (and the Hazlenuts)” for dinner. And now that I’ve read Pavese, I’m delighted by Henry’s idiosyncrasy in choosing him as inspiration for a meal. She acknowledges that his writing is “not cheerful”—and this turned out to be an understatement.

The hazelnut topping for the chocolate bonet gets poured onto a greased cookie sheet where it sets—very quickly. Then you bash it up with a mortar.

Cesare Pavese was born in the village of Santo Stefano Belbo, in Piedmont, and grew up in in Turin, a northern Italian manufacturing city. He became a translator of American authors like Walt Whitman and Herman Melville, and an important writer in his own right, as well as an inspiration to a young Italo Calvino. For people of Pavese’s generation, Italian life was defined by Mussolini who came to power in 1922, before any other fascist leader in Europe. Pavese, like many Italian intellectuals, ran afoul of the state and briefly served time in an internal penal colony in the thirties. The Italian version of the penal colony was almost humorously fair weather and civilized compared to its Russian counterpart, but nonetheless the period was one of arrests and exiles, tides of violence and repressions, war, German military occupation, communist partisan resistance, and social disruption. Neighbor turned against neighbor with disastrous results.

In The Moon and the Bonfires, a nameless narrator who grew up as an orphan and indentured farm laborer in Piedmont has returned after the war, after a time in exile in America, where he’d fled one step ahead of the fascist authorities. He’s seeking a homecoming: “…what I wanted was only to see something I’d seen before … to see carts, to see haylofts, to see a wine tub, an iron fence, a chicory flower … the more things were the same … the more I liked them.” His quest proves impossible. The hills are there, the vineyards, the place names, the Mora, the Belbo. Nothing has changed. And the narrator clearly has an attachment to the land. He writes, “There’s nothing more beautiful than a well-hoed, well-tended vineyard, with the right leaves and that smell of the earth baked by an August sun. A well-worked vineyard is like a healthy body.” Yet the homecoming project is a loss. If we think of Piedmont as rich, stylish, and wine-producing, in Pavese it is dour and savage and unrecognizable.

The aura is of ruin. A different character explains that “the life still lived on these hills was animal-like, inhuman, because the war had accomplished nothing, because everything was the same, except the dead.”

It is the dead, then, who define the landscape, and the hills are full of them. It’s a powerful, profoundly sad book, and upon finishing it I saw its publication date of 1949 in a new light.

I browned my ox cheeks in small batches with plenty of room; it keeps the pan hot and prevents the meat from steaming.

This could not be further from the viva Italia impulse experienced users of a travel-inspired cookbook. And yet Henry’s menu had wine and polenta, a truffle funk, a rich braise, and a neat chocolate cream dessert topped with jewel-box hazelnuts that seemed to capture the beauty and darkness and simplicity of the foods and ingredients mentioned in the novel. Pavese writes with such simplicity about his memories: “These peach and apple trees whose summer leaves are red or yellow make my mouth water even now, because the leaf looks like ripe fruit and it makes you happy just to stand underneath them. I wish all plants bore fruit; it’s like that in a vineyard.” I decided to cook from Henry’s menu, without deviation, as a nod to the old-fashioned world where cooking was determined by tradition.

The “without deviation” approach immediately ran into problems and reminded me of the real reason the book sat on the shelf for so long: Henry’s recipes are challenging, and while they work if you follow them correctly, every little gap or change can cause trouble. I did try a few when the book came in, without perfect success, and then gave it up. The Pavese menu called for homemade pasta with white truffles, but I had no pasta machine, as the book breezily directed me to use, and truffles were out of season. I ended up making the pasta by hand—actually, accounting for mistakes, I made the pasta by hand three times—and can report that I approve of Henry’s usage of only eggs and flour in her pasta (some recipes, like the one I tried on the second batch, also call for oil and salt). Hopefully, what I learned, relayed below, will allow the reader to make theirs only once. Also, instead of white truffles I used black truffle oil, which I’d skip in the future. With such simple dishes, the quality of each ingredient matters.

If you fold your homemade pasta like an accordion, as opposed to rolling it, it’s less likely to stick together.

The second dish, an ox cheek stew with polenta, allowed me to follow the recipe more closely. The finished meat was exquisitely melted and savory, with notes of cinnamon and juniper, and the polenta was the best I’ve ever made. Henry’s recipe directs that we make it with milk and cream instead of water, which is a splendid idea. My adaptions on that recipe below mostly offer more explanation on techniques like browning meat (it takes a long time, and needs to happen in batches, and is improved by aggressively seasoning the meat first) and some pacing suggestions. One wonderful tip from Henry was to add the polenta to the milk by picking it up in handfuls and drizzling it through your fingers. Anyone who has tried to slowly and steadily pour a clumpy ingredient like polenta into the steam cloud above a pot of boiling milk while whisking will appreciate this.

The last dish, a bonet, a traditional Piedmontese dessert since the thirteenth century, is a kind of baked chocolate custard, topped in Henry’s version with spectacularly pretty hazelnut caramel. This recipe worked well for me, but I’ve made caramel before. I know not to stir it, not to walk away at the end, and to pay attention to the direction that tells you to place a buttered cookie sheet next to the stove; also not to stick your finger in for a taste, and what shade of “amber” means it’s done. Know all that and it works like a charm. I made two small ingredient substitutions for the baked custard, one by using golden syrup instead of “golden caster sugar,” which was not readily available to me, and the other using strong brewed espresso instead of the instant kind, also on the premise that in simple dishes the ingredients that convey flavor should be of the highest quality.

The wines of Piedmont are elegant and challenging, like the work of Cesare Pavese.

My attempts to really follow the recipes showed just how hard that is to do. We are always adapting, or at least I am, as a rootless American, despite my best intentions. But it was a successful and thrilling encounter with Italian culinary traditions. I made pasta by hand and dressed it correctly, using the pasta water. I braised an old-fashioned cut of meat. I made superb polenta, and a bonet and caramel.

Henry’s wine recommendation was Barolo, the top-of-the-line Piedmontese wine, which is made from the Nebbiolo grape, “the noble grape” of Piedmont (meaning the one that grows most perfectly there). According to my spirits collaborator Hank Zona, Barolos can be “spectacular, elegant” wines, which taste of “tar, roses and red fruit.” They can be challenging to drink because they’re very tannic (chalky, mouth-puckering) and it wasn’t ideal to run out and buy one, both price-wise and because, Zona explained, these are usually collector wines that will benefit from aging before they’re ready to drink. “Most off-the-shelf offerings need some cellar time before really being optimal,” he said. Zona recommended a more affordable Nebbiolo from the Langhe, the subregion of Piedmont that Pavese was from and where Barolo is made. A bottle of 2018 Langhe Nebbiolo from G.D. Vajra, an acclaimed Barolo producer, “uses Nebbiolo grapes grown in the same vineyards as the grapes used for their Barolos,” and tasted of tar and straw and cranberries—and, I thought, had a whiff of smoke as well. It was a beautiful wine for the meal, the moon, and the bonfires.

Homemade Tagliatelle with White Truffles

Inspired by Diana Henry’s How to Eat a Peach .

2 cups Italian-type 00 flour, plus 2 tbs (white flour also works)

4 large eggs

3 tbs unsalted butter

1/3 cup freshly grated parmesan

a white Alba truffle, smaller than a table tennis ball (or 1/2 tsp truffle oil)

Place two cups of flour on a work surface, and make a well in the center. Break the eggs into the well, and stir with a fork until combined, slowly allowing the flour at the rim of the well to fall into the eggs and be stirred in. Continue to stir, in a circular motion, slowly incorporating the flour into the egg mixture and shoring up the sides of the “bowl” as need be. When the mixture is no longer wet, push the rest of the flour on top, and mix with your hands to combine.

If the dough is still wet, add flour a tablespoon at a time until you can form a sticky ball for kneading. If the mixture is too dry, add water by the tablespoon. The dough should be soft but cohesive. Transfer it to a clean, lightly floured surface, and knead for eight minutes, until it is smooth and elastic. Add more flour to the work surface as need be to prevent sticking. Wrap the dough loosely in saran wrap, and let rest for an hour to allow the gluten to relax and make rolling out possible.

At this point, people with pasta machines will want to use one. The following instructions are to roll out dough by hand: Lightly flour a large work surface. Roll out the dough as thin as possible using a rolling pin, to about a millimeter thinness. It may be a little thicker in spots but should never be thinner than a millimeter. One test of thickness is that you should be able to see your hand through the dough. (I had to use a combination of a rolling pin and my hands and forearms to stretch the dough to the desired thinness.) Redust the work surface with flour, and set the sheet of pasta out to dry for an hour, flipping and reflouring after thirty minutes.

Fold the sheet of pasta like an accordion, and cut in six-millimeter strips. When you’re done cutting the entire accordion, immediately open out the strips to prevent sticking. If they’re too long, cut them to the desired length. Leave to dry on your floured work surface until you’re ready to cook. After sufficient drying, they’ll also survive overnight in the refrigerator, gently piled in Tupperware.

Set a large pot of salted water to boil. Add the pasta, return to a boil, and cook for two minutes, until the pasta is chewy and al dente. Remove and reserve about a cup of the cooking liquid, then drain the pasta and return it to the pan with a splash of the reserved cooking liquid. Add the butter, cut into pieces, and shake the pan to emulsify. Use a fork to turn the noodles until they’re well coated, adding more liquid if need be.

Season with salt and pepper. Gently stir in the parmesan. Shave more than half the truffle (or add the truffle oil). Serve in warmed bowl, topping with more shaved truffle and offering more parmesan on the side.

Ox Cheeks in Red Wine with Polenta

Adapted from Diana Henry’s How to Eat a Peach .

For the polenta:

1 1/4 cup whole milk

2 cups water

3/4 cup coarse cornmeal

4 tbs unsalted butter

scant 1/2 cup Parmesan cheese

For the ox cheeks:

2 tbs olive oil

3 lbs ox cheeks

salt

freshly ground pepper

2 onions, roughly chopped

2 large carrots, finely chopped

2 celery stalks, finely chopped

3 tbs marsala

3/4 cup red wine

4 cups beef stock

a cinnamon stick

6 juniper berries, bruised

6 thyme sprigs

2 bay leaves

To make the ox cheeks:

This dish is most convenient and tastes best when made a day ahead of serving.

Preheat the oven to 300.

Heat the olive oil in a medium Dutch oven on medium-high. Pat the ox cheeks dry, salt and pepper them aggressively, and brown them in several batches, making sure to get a nice crispy crust on both sides. This is where you develop your flavor, and it can take a while.

Remove the ox cheeks to a plate, and reserve. Turn down the heat to medium-low, add the onions to the pan, and sauté until limp and golden. Then add the carrots and celery and give it 5 minutes more, until the vegetables are soft. Turn the heat back up, add the marsala and red wine, and cook until reduced by half.

Return the ox cheeks to the pot, along with any accumulated juices, the cinnamon stick, the juniper berries, the thyme, the bay leaves, and the beef stock. Bring to a simmer. Cover and place in the oven. Let cook for four hours, until the meat is melting apart.

Remove the ox cheeks from the broth. Strain the vegetables and spices out and discard them, reserving the broth. At this point, it’s convenient if you’re making the dish the day before, as you can set the meat and the broth separately in the refrigerator to chill overnight. If chilled, it will be easy to remove the hardened fat from the top of the liquid the next day. But if not, just do your best to remove the fat with a spoon. If you want the liquid to be thicker, put it back in the pan and boil until it reduces to the desired consistency. Halve each ox cheek, and return to the cooking juices. Serve on top of a smear of polenta.

To make the polenta:

Put the milk in a large, heavy-based pan with the water and 3/4 tsp sea salt flakes and bring to a boil. Add the polenta, letting it run in thin streams through your fingers, whisking continuously. Stir for 2 minutes until it thickens.

Reduce the heat to your lowest setting and cook, mostly covered, for 40 minutes, stirring every 4–5 minutes to prevent the polenta from sticking. When it’s done, it should be coming away from the sides of the pan. You might need to add more water, it shouldn’t get dry and stiff, but should be thick and unctuous. Stir in the butter and Parmesan, taste for seasoning, then serve in a warmed bowl with the reheated beef.

Bonet

Adapted from Diana Henry’s How to Eat a Peach .

unsalted butter, for the tin

1 cup sugar

1/2 cup water

1/3 cup blanched hazelnuts

3/4 cup whole milk

1 cup heavy cream

1/4 cup strong brewed espresso

1 1/2 tbs cocoa powder

1/3 cup 70% cacao chocolate, chopped

3 eggs

3 tbs golden syrup

5 1/2 oz amaretti, crushed

This dish is most convenient if made a day ahead of serving.

Preheat the oven to 350. Butter a loaf pan, and a baking sheet and set aside. Measure out the hazelnuts and set them next to the stove.

Make a caramel: Heat the sugar and water gently in a saucepan until the sugar has dissolved. You must not stir it, but you can tilt the pan a little to ensure it’s heating evenly. Now turn up the heat and boil until the sugar turns toffee colored and caramelizes. You will know when it’s ready by the color and the smell; be careful not to burn it. As soon as it reaches this point, quickly pour half into the base of the loaf tin. Add the hazelnuts to the other half and pour that onto the oiled baking sheet. Tilt the loaf tin so that all of the base and some of the sides are covered. Leave this to set. Leave the caramel on the sheet to set, too, then coarsely break it up and set it aside (you’ll use this for decoration later).

Put the milk and cream into a saucepan and bring to a simmer. Add the cocoa and chopped chocolate and stir until the chocolate is melted, then immediately remove from the heat.

Using an electric mixer, beat the eggs and the golden syrup together until they form soft peaks. Slowly add the warm milk and chocolate mixture, pouring it from a height to cool it as it pours, then add the rum and crushed amaretti and mix well. Pour this into the loaf tin and stand it in a roasting tin. Add enough just-boiled water to come one-third to halfway up the sides of the loaf tin.

Bake for 1 hour. (It may need as much as 1 1/4 hours.) The top should feel set when you touch the center, but will tremble slightly. Remove from the water bath, cover with saran wrap, and chill for six hours to firm up. Alternatively, if you are like me and didn’t read about the six-hour chill time until it was too late, you can fill another roasting pan with very icy ice water and set the cake inside to chill, uncovered, for an hour or so.

When ready to serve, run a knife between the bonet and the tin, then carefully turn it out on to a serving plate. The caramel should run down the sides. Top with the shards of hazelnut-caramel.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

March 5, 2020

Ode to Rooftops

John Sloan, Sunset, West Twenty-Third Street, 1906

Jane Jacobs’s canonical 1961 treatise on city planning, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, begins with a thesis of community safety that would raise eyebrows today, in the common era of the NSA. Self-policing the streets, she argues, depends on three elements: the “clear demarcation” of public and private space; street-facing storefronts that act as “eyes upon” public throughways; and the continuous population of sidewalks. Cities, she proposes, ought to make “an asset” out of strangers.

As New York’s patron saint of neighborhood preservation, Jacobs undoubtedly had gentle intentions. She prevented a four-lane highway from razing Washington Square Park, another from dividing Lower Manhattan. Her analysis of the ways in which the design of public spaces can foster or frustrate community bonds continues to shape (and, some would argue, impede) New York housing policy and stock. But in an age of digital surveillance, this motion for keeping “eyes on the street” at all times takes on a decidedly ambivalent ring—in 2020, New Yorkers are already on camera everywhere south of Ninety-Sixth Street. These days, it feels just as urgent to ask after those sites where we might evade the stranger’s gaze. Enter the humble apartment rooftop, the canopy of city life that supports a social order all its own.

The best rooftops, to my mind, are tar platforms on which one may stake a lawn chair and a cooler of beer. I’m biased, of course—my first roommates in New York, two queer Midwestern transplants two decades my senior, held court on the roof. They were exceedingly kind to me, and so it’s likely I will always harbor affection for a stretch of tar. The roommate I saw most often was a robust woman with a penchant for floral prints. On weekend evenings, on the roof, she spilled regally over a cheap lawn chair like a kind of hanging garden, orating on city history. “See those facades?” she’d say. “The city ordained them to beautify the tenements…” Our own rooftop had a vestigial tenement-era cornice, and once a man pushed me up against it, a gesture I indulged mostly because an uninvited kiss beats a five-story drop onto the awning of a newly inaugurated IHOP. She held in contempt those tar-free ordeals leveraged to justify luxury rents. Just look at the Village! Union Square! Penthouses galore. “I blame NYU,” she said.

What heightened the mood of those evenings on the roof, aside from our vertiginous height? Every proper rooftop offers a sense of seclusion, an “eye” on the street, along with the sense that you cannot be seen, though could be; other tenants might imminently appear on your rooftop or on those nearby. It is exactly this partial escape from the gaze of Jacobs’s “natural proprietors”—the blurring of that “clear demarcation” of public and private space—that gives the rooftop its delicate promise of mischief and freedom. Also its intimation of danger: there is no community policing here, just you policing your proximity to the edge. Thus, there pervades on the rooftop a mood of celebratory misdemeanor, further aided by the fact that it is uncolonized by purpose. There’s no one thing you’re supposed to do on a roof, and, more crucially, nothing that’s technically forbidden. It is a private space exposed to public view, and yet with fluid rules of public conduct.

Edward Hopper, Untitled (rooftops), 1926

Because what, really, are the rules of the roof? How do they differ from those of the New York apartment, a privately owned space whose interior, arguably, is just as public as anywhere else? Take Hitchcock’s Rear Window, in which a wheelchair-bound man, confined to his Manhattan walk-up, surveils his neighbors through a pair of binoculars after witnessing what he believes to be a murder. Or the man who used to live above the brand name bakery on the corner of Christopher and Bleeker, who must have known that tourists ogled his half-nude progress from living room to kitchenette, especially in the evenings, when he raised the blinds and turned on the lights. In most New York apartments, someone can see in. But the rooftop and the apartment are decidedly distinct: Is there not an enormous difference between, say, masturbating in one’s private bedroom, even with the blinds open, versus in the semipublic of a roof? On the roof, if you’re caught, you’re a creep, but if not—well, you’ve rather gotten away with something. A confession, a cigarette, a frustrated scream, a song, all change their tenor when indulged in on a roof as opposed to in a living room. Who wants to see The Fiddler on Floor Two? It is the precarious perch that makes the fiddler’s scene; the reckless rooftop cancanning for which we remember Mary Poppins’s chimneysweeps. Antoine Yates, the man who famously raised a Bengal Tiger named Ming and an adult alligator named Al in his Harlem high-rise, used to bring his pets to the roof. “I did get to experience rooftops with them,” he says in the documentary film Ming of Harlem: Twenty One Storeys in the Air. “The city is quiet. That was a nice, beautiful setting … the ultimate moment. It’s like, I’m on top of the world.” There is a thrill to secrets shared on a roof. The sense that you should not be there creates an accidental bond. The sight of the city compresses the sense of public solitude; the intimacy of the roof permits the telling of secrets that otherwise might not be told at all. In Saudi director Haifaa al-Mansour’s Wadjda, the film is punctuated by a series of rooftop scenes in which a mother gently reveals to her ten-year-old daughter the challenges that lie in store for her when she grows up. It is on the roof, unveiled, that the iconoclastic Wadjda learns to ride a bike.

The rooftop is a haven for mischief. Unlegislated, it satisfies the human impulses to be in public and escape supervision at once. “Safety on the streets by surveillance and mutual policing of one another sounds grim,” Jacobs acknowledged. And it is! Even utopian communities are in need of public spaces without surveillance, where one can indulge in a little mischief and imagination; sites accommodating of misdemeanors unacceptable in the regulated public of civilized life; places to test the boundaries of the self. In rural areas, one may retreat to the mountains, the plains, the woods. That’s the beauty of rural life, the ease with which one may escape the public eye. City dwellers need this, too. Perhaps our woods, in a way, are our roofs.

Foucault described “counter-sites” like rooftops as “heterotopias,” places that are “outside of all places.” Their social role is to establish a “space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory.” He invokes as examples the honeymoon, the cemetery, the menstruation tent, the museum, which quarantine sex and death and history in “no-places,” in other-than-here places, in order to protect the greater illusions of chastity and immortality that veneer and facilitate civilized convention; they are little wormholes in the space-time fabric of daily life. By “juxtaposing several incompatible sites” at once, heterotopias transport us to places that logically shouldn’t be able to exist, but, paradoxically and phenomenologically, do. The menstruation tent and prison, for example, are “heterotopias of crises,” places to sequester human phenomena that polite society does not wish to see; the museum and the cemetery are heterotopias of time (“heterochronies”), static places that accumulate years. Perhaps the rooftop—at least the ones not yet sanitized for luxury and leisure—might be called the paradoxical heterotopia of surveillance, a space that superimposes the public and private policing of oneself. To be on a rooftop is to watch yourself through the perspective of a potential witness (can someone see you from their apartment, or yet another roof?) as well as to inhabit the power of looking out at an unsuspecting world. Wherever there are eyes—on the streets, on the internet—we perform. But on the rooftop, the audience remains abstract, without legal or physical power to intervene. One performs for possibility itself.

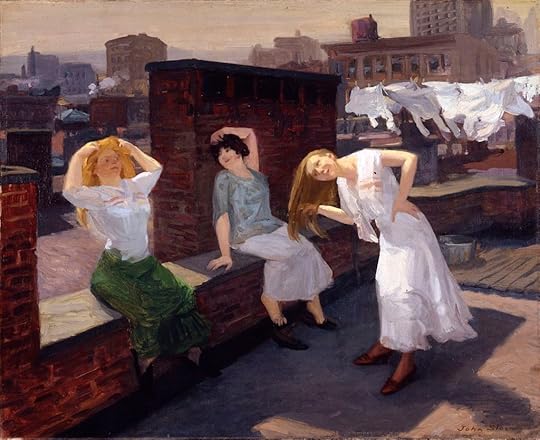

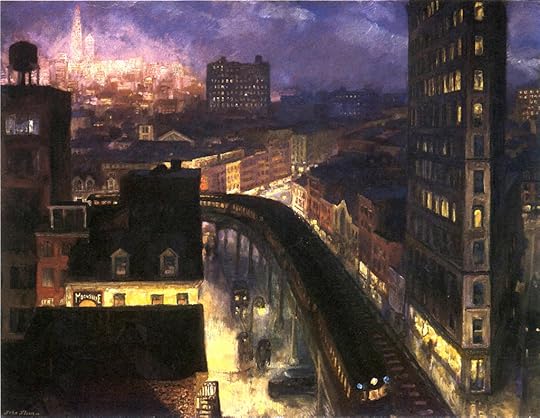

John Sloan, Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair, 1912.

The paradigmatic heterotopia for Foucault was a ship, “a floating piece of space, a place without a place…,” paradoxically “closed in on itself and given over to the infinity of the sea,” and which constituted, he argued, “the greatest reserve of imagination.” He might as well have meant the urban rooftop, a raft adrift in an ocean of its kind. In Balzac’s The Magic Skin, the lovesick Raphael contemplates the “undulations of a crowd of roofs, like billows in a motionless sea,” beneath which lay the “populous abysses” of common Parisian apartments. “[The roofs] suited my humor,” he says, “and organized my thoughts… we are obliged to use material terms to express the mysteries of the soul.” Émile Zola, upon moving to Paris from Aix in 1858, found himself equally transfixed by the romance of the rooftops, which rose in frozen peaks outside the window of his atelier: “It was then, from my twentieth year on, that I dreamed of writing a novel in which Paris, with its ocean of roofs, would be a principal character, something like the chorus of antique Greek tragedies.” Perhaps rooftops really are the chorus of city life, indifferent observers of the pedestrian drama. They break the fourth wall of Jane Jacobs’s street. In a landlocked and airborne world, it is the rooftop, suspended in the infinity of the skyline, that provokes the imagination and invites the private projection of a world. But what do we imagine up there, and for whom?

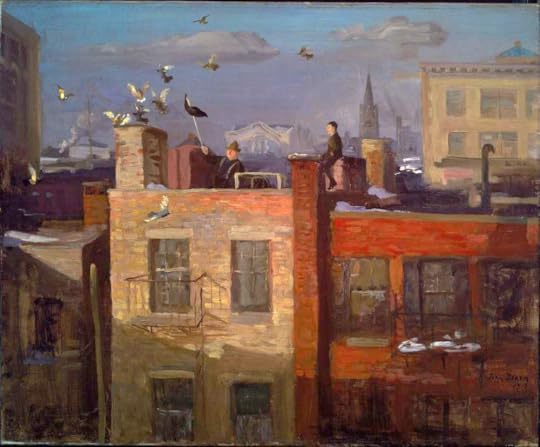

The multipurpose nature of the New York City rooftop was amply documented by American artist John Sloan, painter, etcher, and exponent of the Ashcan School, who devoted himself to depicting the subculture (or rather, superculture) of tenement-era rooftop life. Sloan’s canvases feature laundresses, sun bathers, lovers, dust storms and thunderstorms, nappers, women drying their hair, couples sleeping in the open humidity of a summer night. He observed all this and more from his eleventh-story Greenwich Village apartment: “Work, play, love, sorrow, vanity, the schoolgirl, the old mother, the thief, the truant, the harlot. I see them all down there without disguise.” Without disguise! The roof is private enough that one can cast aside the mask, but also public enough that Joan Sloan can observe it in painterly detail. Tenement dwellers played cards, did laundry, bathed, relaxed, cooked; the roof was as multipurpose as the cramped, one-room tenement itself—yet also an escape, a place of promise the apartment could not provide.

The rich, to be sure, wouldn’t have been caught dead in such a rooftop scene: this was the age of walk-ups, when the parlor level was sought after and upper floors were reserved for laundry, chores, the middle class, and the poor. Only recently have rooftops become the playground of the wealthy, because only fairly recently have rooftops been serviced by elevators. Much like the right to privacy itself, rooftop use has always been determined by class and ease of access. Heterotopias like rooftops “presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable,” says Foucault. “To get in one must have a certain permission and make certain gestures,” and not all rooftop permissions are the same. Swanky bars on hotel roofs establish their exclusivity through rituals of money—the marble lobby, the bouncer at the door. The unfinished, tar-topped roof, by contrast, establishes its charm through sheer, physical inaccessibility; by signaling that the roof is not meant to be inhabited at all. Once, after a break-up, I spent a week apartment-sitting at a friend’s where accessing the roof was usually a two- or three-person job: one to spot, one to climb the rickety ladder and hold open the skylight, another to bring up the wine. I went every evening to that roof, alone, and often entertained visions of myself splayed out on the floor in the empty hall below. Had the roof been accessible by elevator or stairs, I don’t think I would have visited at all. The inaccessibility signaled precisely that it wasn’t meant to be visited, and that was its charm. Like the moon, the rooftop does not naturally support life, though one can make an expedition. If implicit in the heterotopic visit are ideas of escape—from the surveillance state, from rules and social expectations—then perhaps we ought to be most interested here in rooftops that are not meant to be comfortable, and so offer an indifferent invitation to invent, in private, in public, a new use of space. It’s here, on this kind of roof, that one feels most free: once you break the rule of entry, there is no other regulation to acknowledge or obey.

John Sloan, Pigeon Trainer, 1910

In literature, rooftops tend to attract children and itinerants who scramble upward to escape the tyranny of supervision. In Zola’s Belly of Paris—the novel inspired by that ocean of roofs outside his window—two street urchins, Marjolin and Cadine, leap between the gutters and cornices, making picnics of delicacies stolen from Les Halles. In The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Anderson, Kai and Gerda live in buildings with adjoining roofs, and in the high window boxes establish a queen-conquering bond. And is there any better ode to the imaginative freedom of the rooftop than Roberto Bolaño’s The Spirit of Science Fiction, set in Mexico City, where rooftops were, historically, the domain of servants? It is in one of these makeshift rooms that Bolaño’s seventeen-year-old poet sits on a yellowed mattress, writing inane letters to Ursula K. Le Guin. “I was born in Chile,” he writes, “but now I live on a rooftop in Mexico City, with views of incredible sunrises….The showers are cold-water, except for one, which has a boiler that runs on sawdust—it belongs to the mother of four and has a lock.” In Philip Roth’s “The Conversion of the Jews,” an overly inquisitive Hebrew school student flees to the roof after calling his rabbi a bastard. The better part of the story takes place up here, as Ozzie Freeman evades the anxious attempts of community elders, the fire department, his mother, to coax him down to earth and spare the congregation considerable embarrassment. “So far it wasn’t-so-bad-for-the-Jews,” the narrator says, “But the boy had to come down immediately, before anybody saw.” Onlookers encourage him to leap into the fireman’s net, but Ozzie’s power grows the longer he holds out: “Being on the roof, it turned out, was a serious thing… [he] wished he could rip open the sky, plunge his hands through, and pull out the sun; and on the sun, like a coin, would be stamped JUMP or DON’T JUMP.” He makes the entire temple pledge allegiance to Jesus Christ before he acquiesces; escaping to the roof, in a way, makes him more powerful than the rabbi. For children, rooftops are an opportunity to turn the tables. They symbolize power, freedom, an open space for mischief, a chance to reverse the hierarchy of who sets the rules.

The more expensive and well maintained the roof, the more the roof is sterilized, reduced from a heterotopic space to a single-purpose venue among many, zoned for leisure. The zoned roof makes exhausting demands: Enjoy yourself. Enjoy your view. And this imperative implies a presence, an authority, a sense that you are being watched by an anonymous official who leaves his traces in the rules of use: No music. No smoking. No unaccompanied guests. By compartmentalizing life into neat rectangles (gym, pool, rec room, laundry), luxury living sets a predictable trap: one no longer has the opportunity to escape from purpose, for every space and object has its use. Life, fully groomed for convenience—and, one might add, for “best practice”—loses imagination, and therefore delight.

After Iran’s contested presidential election of 2009, demonstrators took to the rooftops to protest Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s victory, secured, allegedly, through vote rigging. As Iranian American journalist Borzou Daragahi wrote in the Los Angeles Times that in the protests that followed, until “10 P.M. arrives, there is nary a sound except for the wind brushing against the drapes. But then the silhouettes begin to emerge [on the roofs], lithe teens and potbellied men. ‘Allahu akbar!’ the two young women cry out across the rooftops. Another voice joins in, and then another, and then another, building to a crescendo.” The practice of rooftop chanting harkens back to the Iranian Revolution, when military curfew prevailed from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M. in an effort to quash public dissidence against the Shah: “It was a way to reassure others that they weren’t alone in feeling wronged and enraged,” Daragahi writes. Minoo Moallem, professor of gender studies at University of California, Berkeley, echoes this sentiment: “After the announcement of curfew, word circulated that every night at midnight everyone should turn off the lights, go to the roof, and shout “God is great!” (Allah-o Akbar!) as a protest against military rule… The roof (bam, or pohstebam) found a new function as a liminal urban space, neither public nor private.” In a nation under lockdown, it was one of the only remaining spaces that could accommodate a public protest, because it was just private enough to escape military rule.

John Sloan, The City from Greenwich Village, 1922

In today’s New York, even the ostensibly free rooftops, like the rooftop garden at the Met, increasingly revolve around the $17 cocktail. The same trend—loftiness equals elite equals money—can be found from Tokyo to London to Paris. The rich have already, have always, reserved their mandate for special exceptions from the rules. What need have they for roofs? And what happens, I wonder, when, like the right to privacy, the right to mischief becomes an exclusively class-based asset. Who can circumvent surveillance, claim space? Who can afford to stand outdoors and feel alone? What happens when surveillance of the public colonizes the sky?

One doesn’t like to think of a world that has lost access to its roofs, that last frontier for escaping rules increasingly written by the rich, and enforced by right-wing governments. I remember those evenings with my two roommates, listening to stories of a city below that, the way they told it, had already ceased to exist. They looked at me, a recent grad—I was the problem, and yet there I was, indelible, up there with them. This transfer of knowledge could have taken place nowhere but that roof. “Hey, you!” one felt emboldened to shout at the IHOP just downstairs. On a humid night, deranged, you looked over the cornice and felt that you could float. I’ve fallen out of touch with that feeling now, though I think the IHOP, and the roof above it, are still there.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens is a writer and itinerant freelancer. Her debut novel, The Exhibition of Persephone Q, is out this week from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. She has published two stories in The Paris Review, “Honeymoon” and “The Party.”

Jonathan Escoffery Wins Plimpton Prize; Leigh Newman Wins Terry Southern Prize

Left, Jonathan Escoffery (Photo: Colwill Brown); Right, Leigh Newman (Photo: Christopher Gabello)

The Paris Review’s Spring Revel is coming up on April 7. At the Revel, we present annual prizes for outstanding contributions to the magazine, and it is with great pleasure that we announce our honorees for the 2020 Plimpton Prize and the 2020 Southern Prize.

This year’s Plimpton Prize is awarded to Jonathan Escoffery for his story “Under the Ackee Tree,” from our Summer 2019 issue. Escoffery’s “Under the Ackee Tree” follows three generations of a family split between Jamaica and Florida. Escoffery tracks the ways in which fathers and sons misunderstand each other, and the nuanced loss and pain endured by immigrant families, with a keen eye to language and pathos. How do you make things right? As he writes:

If you’re a man who utterly failed his child, you can either lie down to join him in death, or you can do more for those remaining.

The Plimpton Prize for Fiction, presented annually since 1993, is a $10,000 award given to a new voice in fiction. Named after our longtime editor George Plimpton, it commemorates The Paris Review’s zeal for discovering new writers and celebrates an outstanding story written by an emerging writer published by The Paris Review in the previous calendar year.

Upon hearing the news that he had won the Plimpton Prize for Fiction, Jonathan shared, “I don’t know that you can plan to win a prize, but you can dream about it, and I’ve dreamed of winning the Plimpton Prize for Fiction for a very long time.”

At the Spring Revel, the Plimpton Prize will be presented by the novelist Alice McDermott.

This year’s Southern Prize will be presented to Leigh Newman for “Howl Palace,” from our Fall 2019 issue. In Newman’s “Howl Palace,” an Alaskan woman revisits her adventurous past as she prepares to sell her “unique” lakeside home:

To the families on the lake, my home is a bit of an institution. And not just for the wolf room, which my agent suggested we leave off the list of amenities, as most people wouldn’t understand what we meant.

The Terry Southern Prize, presented since 2003, is a $5,000 award honoring “humor, wit, and sprezzatura” in work from either The Paris Review or the Daily. It’s named for Terry Southern, a driving force behind the early Paris Review perhaps best known as a screenwriter behind Dr. Strangelove and Easy Rider.

When she heard she’d won the Southern Prize, Leigh shared, “I’m moved and honored—not just because of the caliber of the authors associated with the Terry Southern Prize, authors I deeply admire—but because working on ‘Howl Palace’ with Emily and Hasan, getting to profit from their deeply considered editing, was one of the greatest joys of my writerly life.”

At the Spring Revel, the Southern Prize will be presented by the cartoonist Roz Chast.

We look forward to celebrating the honorees and their work at the 2020 Spring Revel on April 7, at Cipriani 25 Broadway in downtown Manhattan. That night, we will be joined by the 2020 Revel benefit chairs, actor, writer, and director Greta Gerwig and writer and director Noah Baumbach. Singer, songwriter, and musician Bruce Springsteen will present our Hadada Award for lifetime achievement to Richard Ford. Tickets are available on our site.

We are also proud to mention that The Paris Review won the 2020 ASME Award for Fiction for our submission of three stories, two of which were 2020 Plimpton Prize honoree Jonathan Escoffery’s “Under the Ackee Tree” and 2020 Southern Prize honoree Leigh Newman’s “Howl Palace.” Rounding out our winning submission was Kimberly King Parsons’s “Foxes,” from our Summer 2019 issue.

Congratulations to the winners! We hope you will join us to celebrate them, and to usher in a new decade of groundbreaking literature.

Sleeping with the Wizard

Sabrina Orah Mark’s monthly column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

Illustration from a book of 1920s halloween costumes, Cole S. Phillips

When I was nineteen I lived with a wizard. Her hair was like dandelion seed, and she had a map crookedly taped to her bedroom wall. She smoked unfiltered Lucky Strikes and her clothes were always wrinkled and she gave me Walter Benjamin and the poems of Paul Celan and she kept me secret. No one knew I lived with a wizard in an awful, cold apartment that cost $940 a month. She spoke many languages in an accent that seemed to originate from an ancient ruin. I thought she might give me a brain. I already had a dumb heart, and even dumber courage. She was the farthest place from home I could go. The first time we kissed I knew she would undo me.

In L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Great Oz appears as a head, a lady dressed in “green silk gauze,” a beast, and a ball of fire. The first time my wizard appeared to me, she was my literature professor. Her office had no window. I don’t remember her ever smiling, though she did laugh and so her laugh must have resided in a face slightly distant from her face. Like two cities over. I didn’t know then, as I know now, the difference between worship and love.

The Wizard in Baum is a humbug. He’s a sweetheart and a fake. My wizard was no sweetheart and she was no fake. She needed no curtain because I was the curtain. When I pulled myself all the way back there she was. The Wizard of Oz’s real name was nine men long: Oscar Zoroaster Phadrig Isaac Norman Henkle Emmannuel Ambroise Diggs. My wizard’s real name was a little girl’s name. It was the wrong name for her. Her name was the name of a drawing of a girl eating an ice cream cone in a soft pink dress. But I called her by her name anyway. And she called me by mine.

What even is a wizard? A master, a father, a mother, a lover, a god, a magician, a rabbi, a priest, a president, a beautiful, enraged professor? Like Godot, the wizard can be a holding place for what we emit but can’t yet claim or name or know. Our dust in the sunlight. The spell we have but don’t yet know how to cast. Each of us wants something different from the wizard. I wanted to be undone.

“On the fabrication of the Master,” writes Lucie Brock-Broido, “he began as a Fixed star.”