The Paris Review's Blog, page 177

March 25, 2020

Diannely Antigua, Poetry

Diannely Antigua. Photo: Savuth Thor.

Diannely Antigua is a Dominican American poet, born and raised in Massachusetts. Her debut collection, Ugly Music (YesYes, 2019), was the winner of the Pamet River Prize. She received her B.A. in English from the University of Massachusetts Lowell and received her M.F.A. at New York University. She is the recipient of fellowships from CantoMundo, Community of Writers, and the Fine Arts Work Center Summer Program. Her work has been nominated for both the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Her poems can be found in Washington Square Review, Bennington Review, The Adroit Journal, Cosmonauts Avenue, Sixth Finch, and elsewhere.

*

“Praise to the Boys”

………….On Thursdays the boys played basketball

in the church parking lot

………….while Sister Priscilla taught the girls

to sew on buttons, stitch hems, iron collars.

………….She’d lean her rigid body to guide

my hands at the machine, her cabbage breath

………….lingering as she walked to the next girl.

God lingered too. God watched

………….my hands feed the needle blue cloth bits at a time. He

watched my mouth, knew where I’d put it next, on the end

………….of a thread before pulling it through the eye.

Sometimes I’d imagine hemming my uniform

………….above my knee. Sometimes I’d fake a migraine

so I could watch from the attic, the boys

………….with sleeves to their elbows, maybe

just down to a T-shirt. I’d watch

………….their bodies sweat in ways I’d only seen at the altar

to a song I was singing, my voice inducing

………….a twitch of limbs, a wag of tongue

in something we weren’t meant to understand.

………….But God understood. He watched

one of those boys sell drugs at gunpoint,

………….watched one marry my sister, then another

kiss a baby’s toes. Three years later

………….I’d touch the sweat of one, in the backseat

of a Dodge Ram van, windows tinted, skirt

………….pulled up to my waist. God saw the boy

lick a silent prayer, saw my back

………….curve in exalt.

*

“Diary Entry #1: Testimony”

I hope no one reads this—

I was pregnant in the purple dress

when I escaped from the house.

I was going camping, I was going to Canada. I was

missing a girl who was not a bride.

And I’m still searching for

the face. There was a surgery,

a bald head and a grieving. Tomorrow

I will apologize

about that burst, my ugly ghost.

I’ll feel guilty for two people. I’ll go

to the bathroom to get married

and dream of a driveway. In the dream, I’ll feel

the kiss. It’s the year 2000

and I did all my homework. The pastor

suspects nothing. I am 12.

We play the weird game.

And that’s not the end.

Aria Aber, Poetry

Aria Aber. Photo: Nadine Aber.

Aria Aber was raised in Germany. Her debut book Hard Damage (University of Nebraska, 2019) won the 2018 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry. Her poems are forthcoming or have appeared in The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, The Yale Review, The New Republic, and elsewhere. She was the 2018–2019 Ron Wallace Fellow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

*

“Afghan Funeral in Paris”

The aunts here clink Malbec glasses

and parade their grief with musky, expensive scents

that whisper in elevators and hallways.

Each natural passing articulates

the unnatural: every aunt has a son

who fell, or a daughter who hid in rubble

for two years, until that knock of officers

holding a bin bag filled with a dress

and bones. But what do I know?

I get pedicures and eat madeleines

while reading Swann’s Way. When I tell

one aunt I’d like to go back,

she screams It is not yours to want.

Have some cream cheese with that, says another.

Oh, what wonder to be alive and see

my father’s footprints in his sister’s garden.

He’s furiously scissoring the hyacinths,

saying All the time when the tele-researcher asks him

How often do you think your life

is a mistake? During the procession, the aunts’ wails

vibrate: wires full of crows in heavy wind.

I hate every plumed minute of it. God invented

everything out of nothing, but the nothing

shines through, said Paul Valéry. Paris never charmed me,

but when some stranger asks

if it stinks in Afghanistan, I am so shocked

that I hug him. And he lets me,

his ankles briefly brushing against mine.

*

“Operation Cyclone, Years Later”

For all I know, God could be,

after all, favoring a mountain

boy brown with dust, his brow

calloused from the memory of men

he’s stoned to death, pissed

on the corpse of. He is a student.

He has seen, so has been

ruined; each eyeball astonished

with what has shot through

its pupil: a body will morph, in fall,

into its surrounding—even dam. Even

stone. We are what we are taught,

yes, but also what we

hope for. I hope for more than a war

that whittles us to chameleons

or refrigerated paper tags

hanging from ankles. It is so certain,

where we’ll end, yet arbitrary

are the words determining the trajectory

of our journeys; a name, too, is a gene

and may flourish or impugn

the chromosome. Students hope

to be cradled by mothers—hope for lunch,

an hour to play ball. Students

rock back and forth, warmed by the water

of prophecy. A lie, if repeated

ad nauseam, eventually becomes

a prayer. And a cyclone is not a cyclops

although it too has an eye—

it can see. But would it testify?

If the myths are right, the student gathers,

then science is right, and the god particle

isn’t, in the end, meant to be

kind to us. Still, the student imagines God

as moving, colorful shapes. He hums

before pulling the firing pin,

singing I am a student,

I am a student, I am a student

of God, and he is right, for that

he is, and the rotten field we have scythed

of this country is his school.

March 24, 2020

Redux: I Struggle to Stay inside Sleep

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

James Laughlin. Photo courtesy of New Directions.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re reading long, multipart selections—all the better with which to stay indoors. Read on for James Laughlin’s Art of Publishing interview (part one and part two), Roberto Bolaño’s complete The Third Reich (in parts one, two, three, and four) and Frank Bidart’s poem “The Fifth Hour of the Night.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And for even more reading material, check out the Art of Distance, The Paris Review’s new weekly dispatch from indoors.

James Laughlin, The Art of Publishing No. 1, Part 1

Issue no. 89 (Fall 1983)

There were so many different things I had to do. I had to keep in touch with the authors and read the manuscripts, and I had to copyedit manuscripts, and I had to find printers and binders. Then I had to get up ads and do the catalogs. I had to try to sell the books. Publishing, when it’s a one-man operation, is an extremely varied occupation. It isn’t like a big firm where each person does a different job. I don’t know that I looked at it very objectively; I just did it.

The Third Reich: Part 1

By Roberto Bolaño

Issue no. 196 (Spring 2011)

Through the window comes the murmur of the sea mingled with the laughter of the night’s last revelers, a sound that might be the waiters clearing the tables on the terrace, an occasional car driving slowly along the Paseo Marítimo, and a low and unidentifiable hum from the other rooms in the hotel. Ingeborg is asleep, her face placid as an angel’s. On the night table stands an untouched glass of milk that by now must be warm, and next to her pillow, half hidden under the sheet, a Florian Linden detective novel of which she read only a few pages before falling asleep. The heat and exhaustion have had the opposite effect on me: I’m wide awake.

The Fifth Hour of the Night

By Frank Bidart

Issue no. 229 (Summer 2019)

The sun allows you to see only what the sun

falls

upon: the surface. What we wanted was what was elsewhere: cause.

…………………..*

Or some books say that’s what we once wanted. Prophets of

cause

never, of course, agreed about cause, the uncaused cause: or they

…………………..*

terribly did. Asleep, I struggle to stay inside sleep, unravaged by

heart-

piercing dreams—craving, wish, desire to remain inside, if briefly,

…………………..*

obliteration. I cleave to the voice of Poppea’s nurse:

oblivion

soave …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

What’s It Like Out?

In her monthly column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Turns out that watching an actual pandemic unfold in real time isn’t enough for many of us. Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion is being streamed by droves across the globe, sales of Camus’s The Plague are through the roof, and I just received a message from a friend asking if Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year was worth a read. Seems like none of us can get enough of stories that echo our current moment, myself included. Fittingly, though, as the author of this column, I found myself drawn to a scarily appropriate but much less widely known plague novel: One by One, by the English writer and critic Penelope Gilliatt.

Originally published in 1965, this was the first novel by Gilliat, who was then the chief film critic for the British newspaper the Observer. It’s ostensibly the story of a marriage—that of Joe Talbot, a vet, and his heavily pregnant wife, Polly—but set against the astonishing backdrop of a mysterious but fatal pestilence. The first cases are diagnosed in London at the beginning of August, but by the third week of the month, ten thousand people are dead. Initially the government is more concerned with covering its own back than looking out for its citizens, so it’s slow to take action: “No one in power grasped the danger because everyone was busy trying to find a scapegoat.” Soon, however, it’s impossible to ignore the bodies. The eerie “glow in the sky” above the city at night is evidence of vast makeshift crematoria. London is put under lockdown, cut off from the rest of the country. Joe gallantly offers his much-needed help in one of the capital’s overcrowded, understaffed hospitals, while Polly, scared about her impending confinement and increasingly lonely, obtains a medical certificate verifying her health so that she can make the arduous journey to her mother-in-law’s house in a distant, uninfected coastal town. Some enterprising journalist hails Joe as a national hero, but then another digs up a gay sex scandal from the selfless vet’s adolescence and he becomes persona non grata.

Elements of the novel cut unpleasantly close to the bone right now. From the government’s tardiness through the fear that spreads like wildfire through the city: “Seven million lives pounding behind locked doors and twitching net curtains.” Gilliatt even makes the point that comparisons with war—then, of course, still a relatively recent memory for many Londoners—are extremely unhelpful, the danger in this case being “hopelessly different,” with “nothing heroic about it.” Such a warning is still important today. Here in the UK, where I live, both boomers and the elderly have needed reminders that the blitz spirit of “keep calm and carry on” doesn’t work when you’re trying to fight a highly contagious pandemic.

For some, these details will be encouragement enough to seek out a copy of this out-of-print book, but in all good conscience I can’t advocate for One by One’s republication. The novel’s balance is off; although it begins as an apocalyptic nightmare, there’s a discombobulating and not entirely successful shift, about three-quarters of the way through, to cutting social commentary. Writing in the New York Times, Martin Levin called it “a curious muddle of a novel,” the conclusion of which is “a climactic non sequitur.” Even Anthony Burgess—who was a fan—recognized its flaws: “More action and characters and ideas than the small space could carry.”

The shortcomings of One by One weren’t unique to it. Gilliatt’s novels—she published four more: A State of Change (1967), The Cutting Edge (1978), Moral Matters (1983), and A Woman of Singular Occupation (1988)—were not to everyone’s taste, and haven’t aged particularly well either. She had, as Burgess put it, a tendency to focus on “the surface of life—conversations, the taste of pears, facial twitches, ideas that offer themselves but are never pursued.” As such, “action is shunted to the margin,” important events appear in otherwise throwaway sentences. Blink and you miss them. Burgess admired this approach, declaring that it “owes something to E. M. Forster,” but others were less impressed. In the New York Times, Thomas Lask described Gilliatt’s second novel as “boneless” and without structure. “It rambles from one conversation to another,” he criticized, “from one small scene to the succeeding one.” But that which made Gilliatt an imperfect novelist was the same thing that made her such a fascinating short story writer. The terser medium lent itself well to her uneven, texture-heavy approach. I’m much more confident championing her short fiction—of which she published seven volumes—in particular her debut collection, What’s It Like Out?, which was published in 1968 (appearing the following year in America under the title Come Back If It Doesn’t Get Better).

*

Reading the stories in What’s It Like Out?, I can’t help but think of the famous epigraph to Forster’s Howards End (1910): “Only connect!” If there’s one thing that unites the nine tales in this collection, it’s Gilliatt’s characters’ abject failure to connect with those closest to them. As Marian Engel put it in her New York Times review, “All the stories deal with separation and disintegration: marriages break up, partnerships split; people grow away from each other, even as they fear the pain of parting.”

Take the impressively capacious opener “Fred and Arthur,” about a vaudeville duo whose lives are a double act both on and off the stage. “When they went out on their own with girls, they tended to fix things for the same evening so as not to spend two nights separated where one would do.” Their closeness is tested, however, when Fred decides to get married. The night before the wedding, Arthur takes the soon-to-be happy couple out to the Savoy Grill, where he tells Daisy, Fred’s intended, that they’re all going to drink Dom Pérignon:

“We’ve gone off beer since you decided to get spliced,” he said, looking at Fred.

“Fred hasn’t. We always drink beer,” said Daisy, collaring the “we.” Then she regretted it, and touched Arthur’s arm and laughed.

In other stories, marriages deteriorate to such a degree that the couples communicate only by means of letter. The elderly, aristocratic couple in “The Tactics of Hunger” live all-but-separate lives under the same roof. The thorny, unkempt, cardigan-wearing Lady Grubb has decided to preempt the loneliness she fears will envelop her on the occasion of her rheumatism-ridden husband’s death by ceasing all communication with the man. “I hate her,” Lord Grubb protests to his daughter. “I’ve written her notes and notes and notes and she’s never answered one of them. Surely she could send me a message of some sort?” As with many of the stories in the collection, what begins life as a tale of entertaining unconventionality ends with startling emotional resonance. Lady Grubb eventually repels her daughter and her daughter’s boyfriend’s rebukes with a rare outburst of sentiment. “No one understands loneliness if they haven’t been married,” she shouts at them. “For forty years … You two. Fly-by-night affairs. You risk nothing.” Gilliatt doesn’t spare her characters—she portrays them warts and all—but she sees their pain too, and doesn’t shy away from that either.

Gilliatt’s at her very best when she’s writing about oddballs. “For her, character is crucial,” wrote William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, the magazine where eight of these nine stories originally found publication. As Engel writes appreciatively of the collection, “There is, best of all, a confirmation that the welfare state has not deprived England of its eccentricity.” Harriet, the splendid protagonist of “The Redhead,” joins the likes of Lady Grubb. She’s a gangly, Victorian-born woman whose youthful heroines are Queen Elizabeth, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Edith Cavell. She becomes a suffragette, then a nurse during the First World War—beautifully described as “Boadicea with a bedpan”—and who lives on, “tough as old boots,” surviving both the Second World War and cancer, only to be ridiculed by those around her. There’s that poignant sting in the tail, too: “I put this down,” reads the final paragraph, “only because I have heard her daughter’s friends call her ‘mannish,’ and her own generation ‘monstrous.’ This is true, perhaps, but not quite the point.”

Sentence by sentence, Gilliatt also offers up deliciously original descriptive passages. Lord and Lady Grubb’s cold, unhappy home is “decorated almost entirely in weedy shades of green and looked to the children like a fish tank that needed cleaning out.” She’s a writer unafraid of a cruel but necessary detail or two. After the then-thirteen-year-old Harriet has her “thicket” of auburn locks hacked off, the Norland nurse (once a staple in any wealthy English home’s nursery) “robbed of her pleasure in subduing the hair, turned her savagery more directly on to Harriet and once in a temper broke both of her charge’s thumbs when she was forcing her into a new pair of white kid gloves for Sunday School.” The “surface detail” that could be so distracting in Gilliatt’s novels comes into its own in her stories. “She celebrates the bittersweet human condition in prose that brings us her visions undistorted,” wrote the Los Angeles Times admiringly, while Shawn concluded his praise of the collection by declaring that Gilliatt “does not turn away from the dark disorder of existence but defiantly brings to bear on it a powerful intelligence, a benevolent wit, passion, style and pure sanity. She leaves us exhausted.”

*

Shawn began publishing Gilliatt’s short stories in 1965. Two years later, he hired her as a staff writer, and she gave up her job at the Observer to become The New Yorker’s film critic. This, if she’s remembered at all, is what she’s best known for today. Or, perhaps more accurately, she’s known for not being Pauline Kael. The two women shared the role, each working half a year on, half a year off. As the now much more famous Kael put it, they were “ships that pass in the night every six months.” The two women had completely different writing styles. Kael’s reviews were shot through with personal taste and “unbridled passion,” according to Slate’s Sarah Weinman, while “Gilliatt’s enthusiasm came through in elegant turns of phrase crafted with the same care she took with her fiction.” She sums them brilliantly up thus: “Gilliatt was Glenda Jackson to Kael’s Barbra Streisand.” And both were lured by Hollywood. Kael left New York for Los Angeles in 1979, becoming a consultant at Paramount Films, but she chucked it in and returned to the magazine after only a few months. Gilliatt’s dabble with the industry came earlier, right at the beginning of her New Yorker tenure, when she wrote the Academy Award–nominated screenplay for John Schlesinger’s magnificent 1971 film, Sunday Bloody Sunday, the story of a London love triangle with, for the time, a surprisingly liberal attitude to queer relationships. Following the success of Sunday Bloody Sunday, Gilliatt tried very hard to turn “Fred and Arthur” into a film, but was ultimately unsuccessful, according to her friend Betty Comden, who wrote her obituary in the Independent. “It kept almost happening,” wrote Comden, “and then not, a source of great disappointment to her.”

Though she was only in her midthirties when she was hired by Shawn, and thirteen years younger than Kael, Gilliatt’s contract at the magazine came to an end long before that of her esteemed colleague: in 1979, to be exact, when Gilliatt supposedly lifted eight-hundred-odd words from a piece in The Nation for her profile of the author Graham Greene. Intriguingly, Gilliatt was publicly defended, albeit posthumously, by Mary Gilliatt, the second wife of her first husband. In a letter to the New York Times in response to Gilliatt’s obituary, Mary wrote that no one who knew Penelope Gilliatt or her work believed the accusation: “Gilliatt was altogether unlikely to plagiarize anybody’s work and was certainly not known for inaccuracy in other profiles.” Gilliatt was tricky to work with in the best of times, though, in part because of a drinking problem. In Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark (2011), Brian Kellow claims that extra minders from the New Yorker fact-checking department were sent to shadow Gilliatt at film screenings, to ensure she actually sat through the movie she was reviewing. And yet, perhaps because of their long friendship, Shawn continued to publish her short stories even after she was taken off the reviewer beat. And Gilliatt continued to drink. She eventually died from alcoholism in 1993, at the age of only sixty-one. It would seem that her addiction, coupled with the rather ignominious end to her career as a critic, has thrown a dark shadow over Gilliatt’s reputation. It’s unfair: her short stories, with their virtuosity and intelligence, should speak for themselves. For those of you who’ve had enough of pandemic-related entertainment, leave One by One aside and turn to those instead. They certainly make for wonderfully distracting reading right now, and are perhaps a reminder of how difficult it is for us all to connect, even in the best of times.

Read earlier installments of Re-Covered here .

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

Poets on Couches: Stephanie Burt

In our new series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“Untitled [There are more of us]”

by Killarney Clary

Issue no. 88 (Summer 1983)

There are more of us. We came out of a time when birth was happy.

We are prizes. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been so important, so healthy. If any of us suffered war, we were pained less by the enemy than our ability to kill him.

Our number seems a useless power. We were sold on dis-satisfaction—now we’re sold families but they’re no sign of survival this time.

I am very lucky but that’s not life. And maybe no more than any person born in any year, I want but don’t know what, feel unsettled in a sea of similarly restless faces. The breadth of possibility makes choosing seem evasive. We decide but we are slow and small with doubts.

It was 1954 when my parents moved to have room for me. I remember a box my mother packed for me to store at school, filled with canned milk and soup and Hershey bars.

Two thousand good nights. My checked uniform on a hook. My face to the hall light because that felt like a day in the sun. Not fear, not loneliness, but my preference for sleeping near the window and near the floor, humming.

Stephanie Burt is a professor of English at Harvard University, coeditor of poetry at The Nation, and the recipient of a 2016 Guggenheim Fellowship for poetry. Her work appears regularly in The New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker, London Review of Books, and other journals. She lives in Massachusetts.

March 23, 2020

A Brief History of Word Games

Paulina Olowska, Crossword Puzzle with Lady in Black Coat, 2014

When I began to research the history of crosswords for my recent book on the subject, I was sort of shocked to discover that they weren’t invented until 1913. The puzzle seemed so deeply ingrained in our lives that I figured it must have been around for centuries—I envisioned the empress Livia in the famous garden room in her villa, serenely filling in her cruciverborum each morning. But in reality, the crossword is a recent invention, born out of desperation. Editor Arthur Wynne at the New York World needed something to fill space in the Christmas edition of his paper’s FUN supplement, so he took advantage of new technology that could print blank grids cheaply and created a diamond-shaped set of boxes, with clues to fill in the blanks, smack in the center of FUN. Nearly overnight, the “Word-Cross Puzzle” went from a space-filling ploy to the most popular feature of the page.

Still, the crossword didn’t arise from nowhere. Ever since we’ve had language, we’ve played games with words. Crosswords are the Punnett square of two long-standing strands of word puzzles: word squares, which demand visual logic to understand the puzzle but aren’t necessarily using deliberate deception; and riddles, which use wordplay to misdirect the solver but don’t necessarily have any kind of graphic component to work through.

WORD SQUARES

The direct precursor of the crossword grid is the word square, a special kind of acrostic puzzle in which the same words can be read across and down. The number of letters in the square is called its “order.” While 2-squares and 3-squares are easy to create, in English, by the time you reach order 6, you’re very likely to get stuck. An order 10 square is a holy grail for the logologists, that is, the wordplay experts.

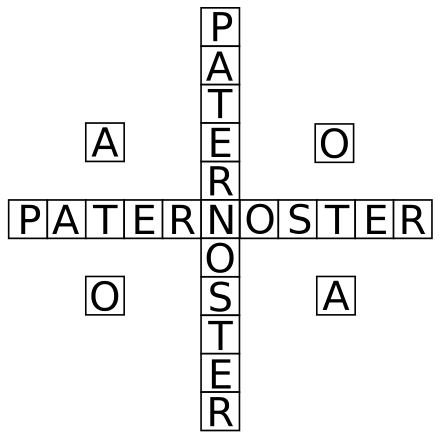

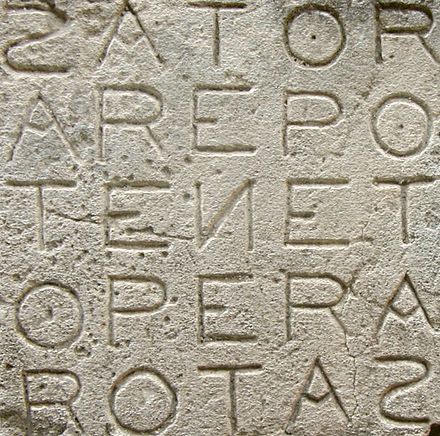

The ancient Romans loved word puzzles, beginning with their city’s name: the inverse of ROMA, to the delight of all Latin lovers, is AMOR. The first known word square, the so-called Sator Square, was found in the ruins of Pompeii. The Sator Square (or the Rotas Square, depending on which way you read it; word order doesn’t matter in Latin) is a five-by-five, five-word Latin palindrome: SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS (“the farmer Arepo works a plow”).

Sator square, Oppède, France

The Sator Square is the “Kilroy Was Here” of the Roman Empire, scrawled from Rome to Corinium (in modern England) to Dura-Europos (in modern Syria). It’s unclear why this meme was such a thing. “Arepo” is a hapax legomenon, meaning that the Sator Square is the only place it shows up in the entire corpus of Latin literature—the best working theory is that it’s a proper name invented to make the square work.

But the Sator Square has more tricks up its sleeve. If you reshuffle the letters around a central n, you can make a Greek cross that reads PATERNOSTER (“our father”) in both directions. Four leftover letters—two a’s and two o’s—stand for alpha and omega. Early Christians might have used the square as a discreet way to signal their presence to one another.

Through the Middle Ages and beyond, the Sator Square persisted as a magical object, gaining a reputation as a talisman against fire, theft, and illness. The devil, apparently, gets confused by palindromes, not knowing which way to read, so a five-by-five two-dimensional palindrome is an extra-powerful snare. The square appears etched on tablets as prevention against mad dogs, a snakebite cure, and a charm to protect cattle from witchcraft.

While word squares maintained their quasimagical reputation for hundreds of years, other visual word games became popular during the nineteenth century. The Victorian era saw a boomlet of visual word games, such as double acrostics, that paved the way pretty directly for the crossword. Queen Victoria, an ur-cruciverbalist, constructed the “Windsor Enigma” to teach her subjects how to bring coals to Newcastle:

Queen Victoria, “Windsor Enigma,” in Victorian Enigmas, or Windsor Fireside Researches by Charlotte Eliza Capel (1861)

Oxford mathematician Charles Dodgson, better known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, invented a game called doublets, in which you transform one word into another of equal length, changing a single letter at a time, using as few moves as possible; all the linking steps also have to be legitimate words. As in a crossword, the process of moving stepwise from letter to letter forces you to think about all the possible word combinations. And each doublet has a theme, a kind of mini-alchemy: Drive PIG into STY. Raise FOUR to FIVE. Make WHEAT into BREAD.

Charles Dodgson, “Doublets: A Word Puzzle” (London: Macmillan and Co., 1880)

But the particular magic of the crossword came when riddles entered the grid.

RIDDLES

Crossword clues trace their origins to riddles, ancient and ubiquitous little games that run the gamut from divine spells to dick jokes. The Exeter Book, an eleventh-century Old English manuscript, has about a hundred riddles of all types: a sweet ditty about a bookworm, barely veiled double entendres about swords in scabbards and bread rising in ovens, and solemn liturgical hymns. There are “about” a hundred because these riddles are still maddening their readers. In the ten centuries since their composition, scholars haven’t conclusively solved every one, which also means that some of the things that get treated as separate puzzles might actually be one giant long riddle, or what we think is a long clue might have two or three answers. Riddle snark is a cottage industry among medievalists, who love to argue about solutions to the riddles, mostly by means of long, ostentatiously thorough academic articles. There ain’t no scholarly rap battle like a multigenerational face-off over whether Riddle 86’s answer is an “organ” or a “one-eyed seller of garlic.”

There are four basic ways that riddle logic operates: true riddles, wordplay, neck riddles, and anti-riddles. The enigma, a metaphorical statement that’s designed to feel like it has one solution but actually contains unresolvable multitudes, is different. Think of koans, like What is the sound of one hand clapping?, or meditative statements like 1 Corinthans 13:12: “For now we see through a glass, darkly.” These are logic knots that want to stay knotted, or (k)not solved.

Riddles, on the other hand, do want to be solved.

TRUE RIDDLES

A true riddle transforms thing A into solution B (A—>B). Take Little Nancy Etticoat:

Little Nancy Etticoat

In a white petticoat

And a red nose;

The longer she stands,

The shorter she grows.

The answer? A candle: the “white petticoat” is the wax, the “red nose” the flame, and of course the longer you leave a candle standing, the shorter it’s going to become. True riddles rely on a logical connection that’s not obvious on the surface, so you have to twist your brain to get it. They’ve been around for millennia, and the best have been repeated for that long. Take, for example, “What has six legs but walks on four feet?” (Answer: a horse and rider.) Or the Sphinx’s riddle: “What walks on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three in the evening?” (A human: crawling as a baby, standing upright as an adult, and using a cane when old.)

When riddles become baked into culture, they can turn into in-jokes. Consider an egg. Egg’s a great solution for lots of images: a house without doors or windows; a house that cannot be reentered; begets parent; and more. In fact, one egg riddle has become synonymous with the whole genre of riddling itself: Humpty-Dumpty—or, if you prefer, his counterparts: Boule Boule (France), or Tille Lille (Sweden), or Wirgele-Wargele (Germany), or Hümpelken-Pümpelken (also Germany)—was originally printed as a riddle with the answer “egg.” The true riddle can thus become a meta-riddle.

WORDPLAY RIDDLES

A wordplay riddle does the same thing as a true riddle, but adds an extra layer of trickiness (A—>∀—>B). Wordplay riddles include puns and other bits of linguistic gymnastics to take the anticipated answer to the next step. A rebus, for example, uses letters as part of the clue. One simple French rebus riddle uses just two letters—G and a—to be read as J’ai grand appetit (“G grand, a petit”). A syllable riddle acts as a game of charades, connecting seemingly disparate parts, as in this eighteenth-century example:

My first is expressive of no disrespect,

But I never call you by it when you are by;

If my second you still are resolved to reject,

As dead as my whole, I shall presently lie.

The answer: “herring” (her + ring).

NECK RIDDLES

A neck riddle gives a solution that would be impossible for the solver to arrive at without context (?—>B). The term “neck riddle” comes from stories in which the hero uses an unsolvable riddle to outwit a judge and save himself from being hanged: a neck riddle saves your neck. One typical folktale example:

As I walked out and in again

From the dead the living came.

Six there is and seven there’ll be,

So tell me this riddle or set me free.

The answer is a horse’s skull that contains a bird hatching eggs; six have hatched but one is still to come. A neck riddle has an answer that’s so specific it’s deeply unsatisfying, because that’s precisely the point: after all, it’s not actually a solvable, it’s got to be such a stumper that you get off scot-free. Often that’s achieved through overprecision, but sometimes a change in perspective will do the trick. In The Hobbit, our hero Bilbo Baggins bests Gollum in a riddle contest by asking him the unknowable “what’s in my pocket?”

ANTI-RIDDLES

An anti-riddle is one that tricks the reader by looking like a riddle but not actually being one at all (A—>A). “Why did the chicken cross the road?” smells like a riddle, but the answer, “To get to the other side,” is just the literal answer. “What’s black and white and red/read all over?” might not be “a newspaper” but rather “a zebra with blood on it,” defying the anticipated pun with the unexpectedly ultraliteral.

*

If you’re a piece of artificial intelligence software, you might have a hard time solving a crossword. You’d have to separate the puzzle into two separate strands of problems to tackle the issue: how to figure out what a clue is saying (or, rather, what it’s precisely not saying); and how to fill the letters in the grid in the way that makes the most sense. Crosswords force the brain to cross wires and solve both these problems at once, balancing the visual-spatial part of the brain with the logic-pun part of the brain. This is part of the reason why even the best crossword-solving AI in the world isn’t yet better than the best human: the AI can fill in the grid pretty quickly, but in terms of resolving that grid through riddle logic, humans are still a step ahead. The most innovative aspect of the crossword is that, through braiding together tasks the mind already wanted to do, it created an itch we didn’t know we had. And yet we’ve always been primed to solve them.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live without Them.

March 20, 2020

Staff Picks: Demons, Decadence, and Dimes

Ladislav Klíma.

Prince Sternenhoch is lovelorn, despite his qualities: “Leaving aside my family and wealth, I may boldly say of myself that I am a beau, in spite of certain inadequacies, for example, that I stand only 150 centimeters and weigh 45 kilograms, and am almost toothless, hairless, and whiskerless, also a little squint-eyed and have a noticeable hobble—well, even the sun has spots.” He meets the silent Helga, whom he instinctively loathes and swiftly marries. She opens up, travels as a brigand, finds her métier as a demon, and starts to murder “like a doctor.” Ladislav Klíma’s (1878–1928) The Sufferings of Prince Sternenhoch, styled as the eponymous noble’s edited journals, is a phantasmagoric freak-out, a work of consummate madness. It is gross and wretched; it is a Tinder date in a pandemic. Sternenhoch lives in a succession of ghoulish castles. He transcribes his titters and cackles and—after he is possessed by the spirit of his defenestrated Saint Bernard, Elephant—his barks. He schemes to make a gorilla cry and invests his fortune in a nut. Helga is killed, gains a swift promotion in hell, and visits to torment. Perhaps they reconcile, when she confesses, “My financial outlook is atrocious, my rabbits all died suddenly, and I have come to realize I lack artistic talent.” The truth is impossible to discern: the tale is all delusion, but for Klíma, delusion is all there is. In A Czech Dreambook, Ludvík Vaculík remarks that “Klíma’s horror stories have no more than a poetic effect on me. I can read them last thing at night and then have a nice peaceful bureaucratic dream.” For Vaculík, Sternenhoch might offer no relief from those anesthetic dreams proscribed by the state, but at present I could do with a good night’s sleep. Besides, I was moved. In Klíma’s “Autobiography,” which is appended to this edition—vividly translated, like Sternenhoch, by Carleton Bulkin—he writes of his life spent in “consistent divergence from all that’s human”: he eats only raw flour and raw horse meat, gobbles mice half eaten by cats, and “would glug down bathwater from people with smallpox.” At that, I put the book down and immediately washed my hands. Then I opened it again. —Chris Littlewood

During these early days of social isolation, I’ve gone surprisingly deep down a rabbit hole of German productions on Netflix. One of my favorites, Babylon Berlin, just dropped its third season with barely any notice. The historical thriller follows the homicide detective duo Gereon Rath and Lotte Ritter through the gritty, decadent Berlin of 1929. Every episode is packed with vivid depictions of debauchery, addiction, and violent crime, all shaded by the specter of rising fascism. About five episodes in, though, I needed a break, so I turned to Isi & Ossi, a German rom-com about a billionaire heiress who falls for a boxer from the wrong side of the tracks. My expectations were low, and I was stunned by the artful and attentive cinematography. In one quiet shot, Isi and Ossi are lying in bed, and a round mirror frames them like a painting. Isi takes notice, self-consciously tucking her hair behind her ear. “We used to have a picture like that in my parents’ bedroom,” she says. “They were lying there like this.” Isi & Ossi, like Babylon Berlin, is remarkable for such small and well-crafted moments of human connection, which, however brief, offer consolation to the solitary viewer. —Elinor Hitt

On October 25, 2015, the New York Times ran a piece about the Dimes crowd. I had been in New York for seven months and wanted to be a New Yorker my whole life. Ticking through the pictures, I felt the aspiration of a suburban teenager all over again. This was clearly where creativity sat down for a wheatgrass margarita and worked the bar. Once I visited, I realized Dimes was everything I wanted New York to be. It’s full of friends and flirting, the waitstaff is always just a month ahead of even the most fashion-forward citizens, and when I finally did get to know them, they told me about their dance companies, their bands, their radio stations. They are cool in a city of young people seemingly made all alike by Instagram and start-up capital. The food feels virtuous and tastes delicious. There are whale songs in the bathroom. In the past few days, as New York City suspended all sit-down restaurant service, Dimes launched a cookbook years in the making. Dimes Times: Emotional Eating captures the charm and character of the restaurant. The trim size is funny, the table of contents is funky fresh, there is a running narrative about the emotional moments of the Dimes day, and there are even cutouts. This weekend my man cooked us Alberto’s unbeatable posole (page 107), and for just a moment it was all still possible: a last-minute trip to Mexico City, a hug across the bar, a waiter job that would keep you afloat between gigs, the din and the smiles of a noisy dining room. Whenever I settle into a seat at Dimes, I think, I’m one of the lucky ones; I’m having my moment in this crazy city. Consider ordering a copy of the cookbook this week or directing a little something straight to the staff. It might just be the coin that keeps Dimes waiting for us somewhere beyond quarantine. —Julia Berick

Praised by Ocean Vuong and Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Vietnamese poet Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s first novel, The Mountains Sing, is a beautiful evocation of a lost world. Nguyễn’s family saga tells the story of a country torn apart by the vagaries of history and the fires of a quickly globalizing political world. But lest I give the wrong impression, Nguyễn’s interests are centered largely on the hearts of her characters, their struggle to maintain their own humanity in a landscape drowned in the blood tides of the past. Her book tour has been canceled due to the current pandemic, but that’s no reason to miss out on this beautiful, stirring novel. —Christian Kiefer

I bought my copy of Culpeper’s Complete Herbal a few years back, not because I am particularly interested in herbal medicine but because I am fascinated by so-called early America, the period when the Northeastern United States was considered by Europeans a wilderness. In those anxious days, the Herbal, first published in 1653, could be found alongside the Bible in settlers’ homes—books to protect body and soul. This week the world again feels like wilderness, the body and soul small and isolated amid looming, shadowy dangers. Depending on your beliefs, Culpeper’s cures can seem pathetic—thank modern medicine, for example, that we’ve moved beyond purslane to cure “blastings by lightning”—but his visual descriptions of plants are timeless. Consider his entry on hellebore, long a favorite of mine for the name’s suggestion of a mythic queen: “It has sundry fair green leaves rising from the root … abiding green all the winter … about Christmas-time … the flowers appear upon foot-stalks, also consisting of five large, round, white leaves a-piece, which sometimes are purplish towards the edges, with many pale yellow thumbs in the middle; the seeds are black, and in form long and round. The root consists of numberless blackish strings all united into one head.” In New York, hellebore appears around March and can be white, rose, green, or purple. Among its many uses, according to Culpeper, the roots are effective for madness. My mind, however, is calmed by the precision of his language and the reminder that outside the walls of social isolation, these flowers—muted in color, bold in their advance against winter—bloom on. —Jane Breakell

Line engraving of Nicholas Culpeper, 1827. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

An Attentive Memoir of Life in Parma

© Olga Demchishina / Adobe Stock.

How tempting to describe Wallis Wilde-Menozzi’s memoir Mother Tongue as a page-turner, as it surely was for me more than twenty years ago. But really, it’s a page-pauser. The instantly trustworthy voice invites the reader to slow into its fine focus, its acute parallels and oppositions, the deft leaps from the frustrations of a Renaissance abbess commissioning Correggio to paint her room in Parma, say, to the homely act of buying bread at the corner store in the same city almost five hundred years later. Much underlining, notes and exclamations crammed in the margins. I’ve been in conversation with this book for many years.

And now, yet again, with the undertow of the pandemic clutching Italy in its fierce grip, the book speaks. Wilde-Menozzi and her husband are “hunkered” (the new verb form of our lives) in Parma, where she continues to take her keen-eyed notes. In an email this week, she reports that the caskets wait in long lines and the nurses weep because they can’t find words to give to those who are frightened.

The signal of a reliable reporter—journalist, memoirist, poet, historian—is the capacity to see oppositions and contradictions with unblinking acceptance: this is reality. Finally, she writes: “All in all, though, spring is unstoppable—after all, it, as well as the virus, is part of nature’s ways. Italy is doing a good job, with many people making sacrifices and being selfless.”

Just now, in the midst of the growing pandemic, my latest consideration of her book underscores its uncanny immediacy. My enthralled first reading probably had something to do with its moment in modern literary history. Mother Tongue appeared in the early wave of personally voiced books in which the narrator is not a heroine, though she’s the protagonist, the seeking soul. This was nonfiction (wasn’t it?), but also lyric, essayistic, inquiring, thoughtful prose. Yet not dowdy “belles lettres.” Research underlay some of it, but it wasn’t scholarly—just reliable. There was even stealth poetry. A mind was revealing itself—to itself. And I, the reader, got to eavesdrop.

There was something intriguingly feral, without guile but with native intelligence, about the book. And all the more engaging for refusing the narrative device of plot, ascending the high wire of associative thought to spin across the trajectory of time. Astute asides about politics—Communism, the Catholic Church, past, present. A passionate inner manifesto was claiming the right to a personal “take” on the world. Yet how did it manage to avoid being self-regarding?

The book employed autobiography as a kind of scaffolding for the real subject, which was an account of an independent mind seeking meaning of and from the world, and from the milky reaches of history. There was a moral imperative at the heart of the enterprise. Heart is the right word for the pulse of feeling penetrating the thinking. It wasn’t just a “story.” Still, the book hoisted itself aloft with captivating vignettes from a supposedly ordinary life, translated improbably from a Wisconsin upper-middle-class Protestant girlhood to Italian family life in still very Catholic Parma, wartime desperation sharp in its memory.

Autobiography may be centuries older in the Western canon than the novel (Augustine sits down in North Africa in 397 to write his Confessions), but when Wilde-Menozzi was writing this book, the term “memoir” was newly adopted to label works that were not reminiscences or the bully tales of “great men” (or great lovers). She was one of the writers—often women—colonizing the dusty self-advertising form and turning it into the quest literature of the age.

Memoir, of course, remains a celebrity genre—apparently you can’t run for president without writing one or having one ghosted. But memoir as Wilde-Menozzi was employing it ceased to be an old-age summing up or an advertisement for the self; it turned into an urgent midlife project. Just as Dante, not all that far from Parma, began his exile quest: “In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself in a dark wood, the straight way lost.”

History’s encounter with contemporary, immediate life is the lodestar and essential business of Mother Tongue. History with a capital H and other histories as well. The history of paper, for example, an early Parma specialty, leads to dismay that it has never been understood as “the embodiment of the infrastructure between private and public; it visibly holds thought.” There should be a Paper Age, the author feels, like a Bronze Age and an Atomic Age. Or the consideration of midday lunch in Parma—a hot sit-down meal, family together, please—a model of incontrovertible social control. On and on, the scalpel makes its meticulous nicks on the surface of life, opening, revealing.

This is not a how-I-got-to-be-me memoir. Those inevitable parental players—mother, father—do come and go here, ghostly Midwestern shapes moving through the mists of the life. They matter, of course. But the beloved daughter is a brighter star, growing up a Parma native as her mother never will be. Or the Italian spouse, a scientist who believes in the intelligence of poetry, for whose love her exile has been undertaken.

But always, the immediacy of history—the great abbess Giovanna’s convent a brief walk away from the Menozzi home, a Renaissance woman modeling early humanist thinking: cloistered, shut down, shut up. The injustice of her enforced silence simmers down the centuries to be protested here by this American woman with the birthright of free speech. Yet perhaps the greatest grandee of the spirit is Alba, her husband’s mother, widowed early, the lean embodiment of postwar labor and love: the hardness of her life, with her love at least as hard—and sharp.

I was heartened, on my first reading all those years ago, to see it was possible to “write a life” and yet not be hopelessly self-absorbed. That it was possible to think with emotion and to feel with intelligence. Here was a writer’s attentive curiosity, as engaged as a scientist studying a slide under the microscope, knowing this attention could lead not only inward, but outward.

Mother Tongue is “an American life,” as its subtitle says, lived in provincial, family-laden Parma (not international Rome, not the Amalfi coast, nor a restored Tuscan villa). This is a life knocked wonderfully off-balance (well, wonderful for the reader) to reveal an almost shockingly frank intelligence. A rare candor pervades and enlivens these chapters. No doubt its keen focus is bred of isolation, even loneliness. Such is exile. The job is to say what you see—inside and outside. It’s an act of faith in our supposedly faithless world.

The exile is not only geographic. It’s linguistic. This is an American writer; English is her business, but her life and the life around her is lived in Italian. “English carried me,” she writes in one heartbreaking line, “but it no longer exists for daily traffic.” She is alone with English, her mother tongue (not a bad thing, perhaps, for a writer). It’s clear she speaks fluent Italian, though we don’t learn how she acquired it, and she can argue with Italians. My favorite episode is her very American fury at the Italian linguistic stop sign: “Impossible.” Impossible, she is told time and again, the word employed to shut down—well, anything, including statements of fact. “Impossible” is a wall without a gate. She storms it, a can-do American. Not that she breaches that wall. “In Parma I have taken this word like a slap in the face, a punch to the stomach, an insult that I am unable to blast in spite of my protests.”

She is left with history, especially what it means to think about women’s lives over time and in time, and to acquiesce to daily life when nothing can be assumed as a cultural given. Assumption about the simplest daily gestures is erased, maybe left back in Chippewa Falls. Such is the fate of exile—the freight of uncertainty and the development of a necessarily keen eye and ear. For this is not an expat story, not about being a visitor observing exotica. Rather, from an American point of view, it’s a reverse immigration story: here the American is the alien trying to wedge into a deeply rutted, traditional way of life, yet determined to maintain her authentic self—whatever, whoever that is.

Her dislocation is often painful, but never expressed as a complaint. Love brought her to Parma, and to that fact—spouse, child, widowed mother-in-law—there is unbroken loyalty. This relentless attention requires radical honesty, a form of inventive humility. That’s what you get from this writer. No wonder I couldn’t put the book down.

*

Books seem permanent—there they are, chunks of effort, bound, stamped with title and author name. But they come into existence, like everything, in time. They are more likely to be ephemeral than eternal. Some books, initially ignored or even vilified, endure and become classics much later. Think Melville and Moby-Dick: “The style of his tale is … disfigured … hastily, weakly, and obscurely managed” (London Athenaeum, 1851).

Nabokov insists that rereading is the real reading. It allows for greater intimacy, but also for fresh judgment. Almost a quarter century (put it that way, and take a deep breath) has passed since this book was new. The bright daughter of this book, a child no longer, is a mother herself, and gone from Parma. Even the touching reference to the exiled writer’s passionate anticipation of “the feast of mail” arriving with the postman has been superseded by the flash-fluency of email. The Italian Berlusconi in the book now seems an unwitting harbinger of the American Trump. Yet Mother Tongue is now more, not less, “relevant,” to use a catchword from the era of the book’s first publication. Partly that’s because the questions the book engages are enduring, indeed eternal—the religious term feels accurate here.

Sensuous writing, the exactitude of metaphor—reading’s signal pleasures—are evergreen on rereading: the “forthright woman … round as an opossum, with permanents that made her hair look like grapes on her head,” and the streets of Parma, “often tucked in by wisps of fog, have a domestic, sleepy, elegant charm … ”

Beyond the elegance of its stone-cut language, the fact of exile envelopes the book. It’s even more eloquent today than twenty-five years ago. At no time in human history, we are told, have so many people been migrants. The exile, back turned from the language and habits of home, facing uncertainty, is the emblem of the human being in our world. And in an eerie turn, right now every “self-isolating” person has become a new kind of exile, sent into social detention where only fellow-feeling can meet and comfort one another. Relationships are no longer “in person,” but perhaps even more “in spirit” as Mother Tongue so often exemplifies in the heart of the experience of dislocation and isolation.

The value of “writing a life” that Wilde-Menozzi undertook, against great odds and alone in her exile language, is now the model to express our times. “Everyone who turns any light on herself,” she writes, “will find sadness and disorientation, ruins, missteps, as well as stupendous beauties and dreams. You change when you act, just as you exist when you stand your ground. The important thing is not to panic, not to give up what you can’t relinquish, and never confuse life with art.”

How strangely apt just now, this caution from a prepandemic life—not to panic. At the heart of this extraordinary memoir written a quarter century ago from “the middle of the journey of our life,” the straight way was—and remains—lost. Mother Tongue shares the personal and social vulnerability Augustine recounted as Rome shattered, and Dante affirmed in his exile. When a writer of such exceptional spirit comes to herself “in a dark wood,” the work becomes an act of surrender, the self giving over to the testimony of history played upon the pulses. Which is to say, the personal speaks for the commonweal. Hope is revealed not as pitiful wishfulness, but as solidarity.

Patricia Hampl is the author, most recently, of The Art of the Wasted Day.

Excerpted from Mother Tongue: An American Life in Italy , by Wallis Wilde-Menozzi. Published by North Point Press, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 1997 by Wallis Wilde-Menozzi. Preface copyright © 2020 by Wallis Wilde-Menozzi. Foreword copyright © 2020 by Patricia Hampl. All rights reserved.

The Rooms

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces in real time the moments before her daughter leaves for college. The column ran every Friday in November and January. It returns through March, and then will again in June.

It’s the middle of the night, or maybe it’s just dark in my memory. I’ve already put my daughter, Indie, to bed. She’s ten, maybe eleven, and we’re living in northern New York. I’m standing in the living room, hitting my palm against a wall and shouting, “Something has to change. Something has to change.”

Not long ago, I asked Indie if she remembers that night. She said she doesn’t. But I can still summon the room, still feel the pinch in my chest. My weariness. At what, I don’t remember, but I can guess it was about a late check in the mail or not finding a permanent university position or maybe it was the snow falling outside the window in April.

In our memories, there are rooms we’ll always be standing in, saying one thing or another. Or not saying what we should.

In high school, before I had my driver’s license, I snuck my father’s Olds 98 out of the garage. I wanted to borrow an outfit from my friend, Amy, an outfit my mother would never allow. I can still feel the rush of rounding Riggs Circle, the windows down, the radio up. Later, when my parents pulled into the garage in my mother’s Cutlass, my father noticed pens and a notebook on his floorboard. I had forgotten to put the seat back (and turn down 97.1 FM, The Eagle). In the living room, I sat on the brick ledge of the fireplace, watching him yell. At fifteen, I was growing more defiant, more confident in my rebellions. “When you leave this house,” he raised his arms, “you’re going to go wild. Wild!” I stood up, arms by my sides, fists clenched. I yelled back, “I already have!”

By that time, I was a weekend drinker, always going as far and as fast as I could toward oblivion. My escapes were the kind that came from roaming our Texas town and passing a bottle of Boones Farm in the backseat or giving some guy from geometry class a twenty for ecstasy or roaring beyond the city limits toward the shores of Lake Ray Hubbard.

My curfew was eleven thirty, but I often got around it by spending the night at Amy’s. Worse yet, she told her parents she was staying with me. The only connection I had to my parents on those nights was from a pay phone.

When my daughter was little, we were poor. I’d often take rolls of toilet paper from the English building. I’d add prices while grocery shopping, Almost daily, I’d divide my checking balance by how many days were left in the month. Sometimes I’d falter under the pressure and yell into the cramped rooms of our apartment. Every time, I’d assure Indie, “I’m not yelling at you. I’m yelling at the world.” It wasn’t until she was twelve that she finally responded in a sad voice: “It sure sounds like you’re yelling at me.”

I stopped yelling.

As Indie approached high school, I braced myself for a turn. I readied myself for her own wildness, her rebellions, her yelling at the world and at me. I figured the smokes I’d kept locked in my glove box at her age, the boys who lingered outside my bedroom window, even the Bartles & Jaymes I’d kept in my trunk had set me up for the surge I assumed would come. It never did.

I gave Indie the same curfew, eleven thirty, though I added an “ish,” remembering how I used to speed across town to get through the back door on time. More often than not, Indie texts me well before her curfew that she’s on her way home.

When she started driving, I told her to text me both when she arrived and when she left. She told me how some of her friends gasped in horror at my rule, while others said they wished their parents cared where they were. Last month, I told her she could stop texting because soon she’ll be coming and going from places I don’t even know exist a thousand miles away. Just now she texted, “I’m at work!”

My mother and I spoke a jagged language, and sometimes we didn’t speak at all. When I was in sixth grade, I told her she was a bad mother. I don’t remember why. We were standing in the dining room—I can still see the thick gold carpet, the shine of the dining room table, her tears. I never apologized. I should have.

Those years when we lived in New York, I had a friend whose children were in their twenties. She and I would go on walks through the woods beyond the campus, and once, as we stepped around a fallen tree limb, she said, “Always apologize to your child. If you want a good relationship with her when she’s older, say you’re sorry when you need to.” It was good advice.

In graduate school, one of my professors asked why I never wrote about my daughter, who was barely one at the time. “There’s no conflict there,” I told her. And so it has gone, all these years. No shouting matches, no slamming doors, no silent treatments.

Indie was only three when I went to rehab. My days had turned into a steady stream of wine. My mother mailed me a letter: “You have a daughter who calls you her best friend. Don’t lose that.” My father left a message on my voice mail: “Pull your head out of your ass.”

I did.

At eighteen, Indie still calls me her best friend.

Maybe she and I have always gotten along because it’s the two of us. Or maybe it’s because we only have each other. It’s tough to turn on that.

Earlier this year, we went to New York City for the first time. I think it was our fourth day of riding subways and staring at maps on our phones and sharing a small hotel room. We were turning onto Forty-Sixth Street from Sixth Avenue just as dusk settled between the buildings. After a long day of walking, we were weary. When Indie said she was tired, that she wanted to get back to our hotel, I stopped. I spun around and shouted into the blur of horns and a passing tour bus.

The days of this last year with her at home are dwindling. Soon so much will have to change.

It had been years since I yelled at the world. And for the first time, my daughter yelled back. We stood in a front of a bodega, stunned. Suddenly the busy street felt like a small room. We dropped our heads and stared at the sidewalk as if we had spilled something. “You know,” she said, “we don’t have to fight because I’m leaving.”

We both said our sorrys. We went on our way.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

March 19, 2020

Krazy Kat Gets the Spanish Flu

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat ran in the Sunday papers from 1913 until 1944. The strip’s offbeat poetry and idiosyncratic dialect made it one of the first comics to be taken seriously by intellectuals and praised as high art (e. e. cummings wrote the introduction to the first collection of the comic to be published as a book). The premise is a deceptively simple love triangle: Ignatz the mouse despises sweet, simpleminded Krazy Kat, who nurses an undying love for him. Ignatz hurls bricks at Krazy, who takes each one as a sign of affection (“Li’l dollink, allus f’etful,” he says, as the bricks bounce off his head). Officer Pup, in love with Krazy Kat, attempts to protect him by thwarting Ignatz and jailing him. In the strip below, from 1918, Ignatz and Krazy come down with the Spanish flu, which apparently can be contracted by dreaming of bull fights.

Page courtesy of Michael Tisserand, author of Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White

George Herriman was a cartoonist, best known for the influential ‘Krazy Kat.’

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers