The Paris Review's Blog, page 174

April 3, 2020

Poets on Couches: Lynn Melnick

In this series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“Lament”

by Sharon Olds

Issue no. 108 (Fall 1988)

Finally someone just drops it and breaks it

like a mercy killing, the cow butter dish,

it cracks easily into five pieces,

opening like an earthenware flower on the floor:

a crescent of furrowed terracotta, a

dry cold bisque side, a

rogue shard, the cow herself broken

free, upside-down, hollow-muscular inner curves of her body,

slim elliptical hole of her throat leading

into the darkness inside her head.

Long, drawn-out ending of my motherhood,

these kids I see less and less—

better to smash some china like the end of a

love-affair. I take her in my hand,

convex flanks fitting my palm,

thumb and forefinger holding her neck at the

carotids, kiss her mild

dumb forehead, look into her empty

shape smooth and chambered as a woman’s sex,

the way God might have sat on the bank

first shaping the clay.

Even on the hottest day if you

soaked her in cold water in the morning and

set her on the dish she would keep the butter

cool till night in the dark of her body,

fresh, and soft.

Lynn Melnick is the author of the three poetry collections, most recently Refusenik, forthcoming from YesYes Books in 2021. I’ve Had to Think Up a Way to Survive, a book about Dolly Parton that is also a bit of a memoir, is forthcoming from University of Texas Press in 2022.

April 2, 2020

Why Certain Illnesses Remain Mysterious

Michael Peter Ancher, Den syge pige (The Sick Girl), 1882, oil on canvas, 31 1/2″ x 33 1/2″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

When I first began research for my book about women with mysterious illnesses, I was overwhelmed. No two women were alike. The number of illnesses that qualified as mysterious was staggering. Lyme, post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, candida, Epstein-Barr, Ehlers-Danlos, polycystic ovary syndrome, subclinical hypothyroid, dysautonomia, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, nonceliac gluten sensitivity, heavy metal toxicity, environmental illness, sick building syndrome—I had started out with the intention of exploring intestinal health as it relates to chronic fatigue and women’s health, but as soon as I turned on my headlamp, women with mysterious illnesses of all kinds came hurtling out of the jungle, like giant moths to a tiny flame.

And so one of the first things I ever did was come up with a clarifying top-ten list regarding the problems contributing to the mysterious marginalization of the mystery illnesses. This list was not exactly a clue in figuring things out, but rather a series of clues making it clearer and clearer that there really was a veil tightly drawn before anyone who was trying to figure things out.

More than a decade later, the list is still as useful as ever.

Problem 1: Invisibility

Each of the chief mysterious illnesses is largely invisible, at least according to our current standards of seeing. A typical disease presents something a doctor can observe, either under the microscope or in an examination. But not these diseases. There are no tumors, no elevated blood count, no pallor. I noticed I had to catch myself many times in my interviews—a woman would open her door, and look so absolutely normal that I couldn’t help but think I’d finally found the lazybones who was just exaggerating to escape from the pressures of real life. I had to remind myself that this was exactly what people thought (and still think) about me.

But if those women just had some piece of data to hold on to, some scan to hold against the backlight, to show the world the contours of her problem, that would make a huge difference. However, for such symptoms as chronic pain, fatigue, and irritable bowels, there are no scans. And this brings us to a critical point that cannot be underscored enough: the available standardized tests for the mysterious illnesses are very crude. They were in 2006, when I started looking into the matter, and they still are in 2020. Sophisticated tests are produced by sophisticated research. Which brings us right to Problem 2.

Problem 2: No Research, No Funding

This is a chicken-and-egg issue. You can’t get funding to research a disease that is not considered serious or real, but a disease is not likely to be considered serious or real if there is no good research or clinical trials associated with it.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is the most glaring example, the funding for which has been historically minuscule and mismanaged. Currently there are $14 million allocated for research for CFS from the government, compared to $6.3 billion for cancer research. That is, 0.2 percent. Fibromyalgia receives the same—$14 million, a number that comes in at the very bottom ranks of what the NIH chooses to invest in every year. Even the funding allotted for all the autoimmune diseases, which outnumber the incidences of cancer, HIV/AIDS, and heart disease combined, is just $806 million, or an eighth of the cancer fund.

Interestingly, Lyme disease actually serves as a good reminder of how important research is. Lyme disease spent about thirty years as one of the chief mysterious illnesses—and the way they partially demystified it was when they developed a better blood titer. For decades prior, most Lyme patients were often considered as hypochondriac as the rest of us ladies. Nowadays, Lyme is one of the first tests they run if you come in complaining of the usual mysterious problems. This could have been a lesson that when a disease doesn’t show up in the lab tests, but corresponds identically to the anecdotal evidence of thousands of other case histories, that should speak to the inadequacy of the tests, not the inadequacy of the patients.

Alas.

Problem 3: Vague Symptoms

Achy? Yeah, I got aches and pains, too, lady.

Problem 4: Myriad, Overlapping Symptoms

For example, mold illness, Lyme disease, and the Epstein-Barr virus—three distinct, separate problems—can have almost identical achy, fatigue-y, irritable-bowel-y symptoms, yet no two cases are ever exactly the same. Any Lyme specialist will tell you that Lyme manifests in a range of expressions from individual to individual—more so than most illnesses. The same is true for Epstein-Barr, mold illness, and indeed, all the mysterious illnesses. There are simply so many symptoms associated with each illness, you never know which ten of the one hundred the patient is going to present with. Thus it is extremely difficult to figure out just which permutation of the problem the patient actually has, and misdiagnoses are rampant. Furthermore, the sheer number of symptoms that tend to accompany these problems—each manageable on its own, but terrible in the aggregate—is totally overwhelming for a doctor. Night sweats, acne, abdominal distention, dry eyes, lower back pain, left ovarian pain, painful periods, exhaustion, low blood pressure, dizziness, insomnia, sensitivity to dairy, sensitivity to gluten, sensitivity to nightshades, stiffness, constipation, diarrhea, constipation and diarrhea—

If I were a doctor, I might be running in the other direction, too.

Problem 5: Shame

If a woman’s disease happens to veer in any way toward the vaginal, the urologic, or the colorectal, then she is seriously out of luck—too unpalatable for any awareness campaign, too unsexy to start a blog, too vago-uro-colo to merit a ribbon or a million-mom march. Yet these female-centric symptoms are very common with the mysterious illnesses. That means there are millions of miserable women who are not getting the care they need because they are essentially afraid to be the gynecologically squeaky wheel.

Problem 6: Bad Treatment Options

Let’s say you do luck out and get a doctor on your side who wants to help. Well, the next problem is that there are almost no tried-and-true allopathic protocols that actually help. Thus, not only does the doctor have a chronically complaining patient with invisible symptoms—when he tries to take her seriously and test out some treatments, she doesn’t get better. I can see where this would frustrate a doctor and put him back to square one of disbelieving. But I can also see that sophisticated protocols are the product of sophisticated research and implementation.

Problem 7: Bias

You can be sure that if 85 percent of fibromyalgia patients were men, rendering them unable to work from extreme fatigue, bone-deep pain, and mind fog—there would be no problem getting the funding and research to look into this scourge upon the modern male workforce. And so Problem 7 brings us right to Problem 8.

Problem 8: Fear and Loathing of the Female Patient

My own father has been known to ask a certain type of chronically complaining woman if her left elbow hurts when she urinates—a completely bullshit question—and will be amused when the answer is yes. In part, this is because my father is a jokingly self-described egomaniacal chauvinist. (Note: my father is also a very caring physician, if prone to pranks and helping people take themselves less seriously.) But in part, and I hate to say it:

Some women can be very—how shall we say—tenacious about their health. And this tenacity is almost regardless of how healthy they are.

Believe you me.

But on the other hand, let’s be fair:

Isn’t it vital that someone in the family be vigilant about the family’s health? While women are frequently criticized for dragging their husbands to the doctor, the truth is that women frequently save their husbands’ lives. And their own lives. Not to mention that women are also much more active in making sure their children receive regular medical care and checkups, which is a good thing.

But unfortunately, this positive interpretation is not the party line. The party line is that women are irrepressibly worried about their bodies for no reason at all, and seek medical attention more often than men purely because they are the most nervous of Nellies.

Problem 9: Our Broken Health Care System

This merits an entire shelf of books unto itself (and there are of course already hundreds), but the fact remains: the American health care system is not functioning well. As noted, if you have a complex disease that is difficult to diagnose, then a fifteen-minute HMO doctor’s visit and quick-fix prescription for pain medication is clearly inadequate. If you’re healthy as a horse, a fifteen-minute visit is probably inadequate.

Furthermore, most medical schools do not offer almost any training in nutrition, and proper nutrition is the foundational and easiest way to prevent and sometimes reverse many chronic illnesses. Just that statement alone, “proper nutrition is the foundational and easiest way to prevent and sometimes reverse many chronic illnesses,” is anathema to most medical students.

But in the end, the roots of all these problems—not enough time to listen, no emphasis on healthy behaviors, and no robust systems to help patients with behavioral change—come back to the same problem.

They are not wildly profitable.

Virtually every problem in the health care system can be understood by following the money.

If something is not a cash cow, it isn’t just ignored—it will often be actively campaigned and lobbied against as dangerous, indulgent, or pseudoscience. It is a sad state of affairs, but in no way a secret state of affairs, and it can’t be emphasized enough.

Anyway, I promise we’re coming to the end. Did I mention it’s complicated?

And we have yet to talk about the most intriguing problem of all:

Problem 10: These Epidemics Are New

Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Hashimoto’s disease, Lyme disease, lupus, polycystic ovary syndrome—in 1960, these were all rare. But in the past fifty years the new cases of these diseases have been raining down from the sky like hail, frogs, and locusts.

Fifty million women in this country suffer from these illnesses, at a very low estimate.

That’s one in four women.

And that, girls, is a lot.

*

So this is how it began.

After several years of fieldwork in this area, I casually remarked to my friend Elena that I had begun work on a book that would be called The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness. I joked that it would be a modern everywoman’s tale, an Odyssean adventure—complete with mysteriously sick sirens, stethoscope-wearing cyclopses, and an epic intestinal battle. And this friend of mine had (of course) dealt with a horrible mysterious illness of her own, so she was enthusiastic. Encouraged, I went back to the business of sketching out my pet project, wrestling over important questions, like which was the best chapter title, “Yeast of Burden” or “The Red Vag of Courage.”

But then a curious thing happened—something that would happen over and over again during the next decade. By the end of that week, I received emails from six women I had never met. They were friends of Elena’s, and they wanted to share their stories for the project. They all had mysterious maladies—from post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome to candida to chronic fatigue—and we emailed back and forth. And in a few weeks, as they put the word out, women started popping up everywhere, describing to me in the minutest detail the function and dysfunction of their intestinal tracts. We would compare cupboards full of supplements, occult healing modalities, and caches of our rogue research. But what they mainly wanted was for someone to listen to them, and that I could do. I listened to more than two hundred women of all sorts—younger, older, richer, and poorer. I listened to stories of how their own bodies had slowly gone to pieces, or how their daughter’s body was unraveling right in front of them, or how their best friend was vaguely (and often not so vaguely) deteriorating.

On my listening tour, I began to have the sense that my pet project with the joke chapter titles and the strong stances on microbiota and the patriarchy was actually the thing these women had been looking for all those lonely afternoons spent wandering Barnes & Noble, coming up empty among the self-help books, the fad diet cookbooks, and the gentle pastel books about women’s health.

And I confessed to myself, it was the thing I had been looking for, too.

And this is how The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness came to pass—a book designed for aunts, coworkers, sisters, and girlfriends alike—a book to keep under her pillow late into one of her dismal, insomniac nights—a book to share with her support group, or family, or book club—a book bearing a very simple message:

You are not crazy.

And most important, you are not alone.

Sarah Ramey is a writer and musician (known as Wolf Larsen) living in Washington, D.C. She graduated from Bowdoin College in 2003, received an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction writing from Columbia in 2007, and worked on President Obama’s 2008 campaign.

From The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness . Copyright © 2020 by Sarah Ramey. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Quarantine Reads: ‘Faces in the Water’

In this series, writers present the books getting them through these strange times.

Recently, I’ve found myself drawn to stories about women locked up. I’ve been reading Anna Kavan’s short fiction, in which protagonists are pursued by invisible enemies—nameless perpetrators of “some vast and shadowy plot” against them—and shut in asylums “where days passed like shadows, like dreams.” I’ve finished Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, in which two outcast sisters seek refuge from society’s taunts in a crumbling mansion. And I’ve returned to Katherine Mansfield’s restless diaries from the French sanitarium where she died of TB in 1923 (“Felt ill all day … rather like being a beetle shut in a book, so shackled that one can do nothing but lie down”). At a time when neither escapism nor consolation quite appeals, I think I’m enjoying these strange, claustrophobic books for their emotional intensity, their piercing portraits of dissolution, and their dark, absurdist humor in the face of despair.

In my quarantine household, we have a notepad by the bread bin on which we keep a list of the movies we plan to watch in our own indefinite confinement. Last week, we put on An Angel at My Table, Jane Campion’s 1990 adaptation of Janet Frame’s autobiography, which Hilary Mantel has described as “perhaps the most moving film ever made about a writer.” We meet Janet as a squat, determined child, with a frizzy mop of ginger hair. Over two and a half searing hours, we watch her flounder to find her place in a hostile world, from the unremitting tragedy of her childhood in the New Zealand coastal town Oamaru (a father who beat his children, a brother with severe epilepsy, two older sisters who drowned in separate incidents) to the grim unfolding of her twenties in psychiatric hospitals across the country. In 1945, age twenty-one, Frame was diagnosed as schizophrenic and incarcerated at Seacliff Lunatic Asylum, where misunderstood patients were routinely condemned to electroconvulsive therapy. Over the subsequent eight years, as she wrote in An Angel at My Table, she “received over two hundred applications of unmodified ECT, each the equivalent in degree of fear, to an execution.” In 1952, while she was awaiting a scheduled lobotomy, it came to the attention of the hospital superintendent that Frame’s book The Lagoon and Other Stories had recently won the Hubert Church Memorial Award. He canceled the operation and Frame was released. She left New Zealand and spent her life living and writing in exile: some of the film’s last scenes show a suntanned, laughing Frame in Ibiza, enjoying a carefree love affair and creative productivity. She died in 2004 as a celebrity, her funeral broadcast live to the nation, her body of work regularly mentioned alongside that of Mansfield, for whose family Frame’s mother had once served as a maid.

Frame wrote Faces in the Water (1961) at the encouragement of a psychiatrist who had reversed the diagnosis of schizophrenia and declared her sane. Convinced that what others saw as madness was rather the symptom of extraordinary creative genius, he suggested she process her experiences by transforming them into fiction. The novel’s Cassandra-figure narrator, Istina Mavet, is confined to an asylum, for unspecified reasons. Removed from daily life, she sits trapped in a small single bedroom, gazing at the cherry blossoms through windows that slide open no more than six inches, while sinister staff in pink uniforms stalk the corridors, keys jangling on their belts. Each morning, the nurses announce the names of those scheduled for ECT: “the new and fashionable means of quieting people and of making them realize that orders are to be obeyed.” As they approach, Istina attempts to suppress any behavior that might mark her out as volatile: “to leave no trace when I burgled the crammed house of feeling and took for my own use exuberance depression suspicion terror.” She knows that “the doors to the outside world are locked,” so when her name is called, there is no escape: dragged from bed and locked in the observation dormitory, she can hear the faint sounds of the absolved clattering spoons at breakfast. As soaked cotton wool is rubbed on temples, floral screens are drawn down between beds, and pillows placed at an angle, the screams are snuffed into submission, and the patients begin to lose consciousness: “I dream and cannot wake, and I am cast over the cliff and hang there by two fingers that are danced and trampled on by the Giant Unreality.”

When Istina denounces the cruelty with which the most vulnerable patients are treated, one nurse scoffs: “Can’t you understand that these people to all intents and purposes are dead?” When a bright doctor suggests that “mental patients were people and therefore might like occasionally to engage in the activities of people,” the result is horrifying “socials” in which inmates are forced to waltz before an audience in a parodic performance that belies the very humanity it’s purported to affirm. Yet Istina refuses to have her “mind cut and tailored to the ways of the world.” Against stern instruction, she strives to preserve her imagination, and her empathy for those around her, in case “a tiny poetic essence could be distilled from their overflowing squalid truth.” Frame’s major theme, across her work, is the disassociation and anguish inherent in living on the threshold between the outside world and the “Mirror City,” as she called it, of an inner life. Her visionary protagonists suffer in a society that feels threatened by those who refuse to conform. Daphne Withers, the heroine of Frame’s debut novel Owls Do Cry, is a child whose imaginative world provides her with a refuge from the illness and poverty in her family; as she grows up, her spirit is sacrificed to an adult world in which poetic vision is an aberration, not a gift, and where doctors are prepared to modify her brain to make Daphne “be just like other people.” Reviewers likened the novel to Goya’s Disasters of War etchings or the work of Dostoyevsky for its exalted depiction of suffering.

Recalling her time at Seacliff, Frame wrote, “I inhabited a territory of loneliness which I think resembles that place where the dying spend their time before death, and from where those who do return living to the world bring inevitably a unique point of view that is a nightmare, a treasure, and a lifelong possession.” Frame always denied that her books were purely autobiographical. Yet as I read Faces in the Water, spending hours immersed in her shifting, poetic, dreamlike language, it’s clear to me that she’s seeking a literary form to express real truth. Instability and incoherence are embedded within Frame’s rich, associative sentences. Her writing is experimental in the most urgent way possible: in finding her voice, Frame—like Istina — is grappling for a way to survive. In 1947, after the death of her sister, Frame wrote from the asylum to a friend, “We are such sad small people, standing, each alone in a circle, trying to forget that death and terror are near.” But if we “join hands,” she suggested, “we have the strength then to face terror and death, even to laugh and make fun of being alive, and after that even to make more music and writing and dancing.” It’s a remarkably hopeful, generous vision from a writer who has visited the abyss of hopelessness and returned convinced of the power of art.

Read more in our Quarantine Reads series here.

Francesca Wade is the editor of The White Review. Her book Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars is published by Faber in the UK and in the U.S. by Tim Duggan Books in April.

April 1, 2020

Make Me an Honorary Fucking Ghostbuster!

© Zacarias da Mata / Adobe Stock.

Years ago, right after I moved into my last apartment in Chicago, the one I expected to die alone in to the soundtrack of an NCIS marathon, I thought I had a ghost. Several nights a week, I would be awakened from a dead sleep by this—I don’t know how to describe it without sounding like a fucking moron, but I’ll try—vibrational energy? I’d be knocked out atop a pile of pizza boxes and magazines, then be jolted fully awake by a humming and swaying feeling in the air.

I am a dumb person who doesn’t understand building structure or architecture, but it didn’t seem like the kind of thing a fucking midrise apartment building should be doing. It was like my room was droning at me. Every morning while getting ready for work in those days, I would listen to this ridiculous show on Kiss FM hosted by a dude I’m pretty sure called himself Drex. You know what makes me wistful for a happier, simpler time? Thinking about when I could actually crack a fucking smile at prank mother-in-law calls on drive-time radio shows before living turned to hell and I had to be mad about everything all the goddamned time. You know what I listen to now? Pod Save America, on a phone I come perilously close to dropping in a toilet full of feces every single morning. Because we live in a fiery hellscape, and I don’t know what the three branches of government do exactly, I need three IPA bros to explain our crumbling democracy to me between ads for sheets and Bluetooth speakers while I wonder which of the six washcloths scattered around the shower is mine.

So early one morning Drex on Kiss FM tells this riveting story to the other hosts (you know how those shows are: pop hits interspersed with prank calls and ticket giveaways, and they feature a woman of color who is funnier than the host is, but who is forced to play sidekick, and featuring “my old pal Clown Car with the traffic and weather on the twos!”) about how he had a ghost in his place. And he knew it was a ghost because he’d come home after work and cabinets would be hanging open and shit would be rearranged, and no one else had a key to his apartment. I immediately glanced around my clothing-strewn apartment and wondered, Was that novelty Taco Bell bag filled with Corn Chex cereal on my nightstand when I left yesterday? Drex had consulted with a paranormal expert who told him that the best way to deal with a ghost is to firmly yet politely demand that they leave, because apparently ghosts have some strict moral code that they are required to adhere to. And so, the day before, when he’d gotten home from work to find yet another rearranging of his belongings, he yelled at the ghost to leave him alone, and lo and behold, IT DID. I was gobsmacked.

I was brought up in church, but taken there by people who smoked and drank and had multiple children out of wedlock. Whatever lingering side effects I have from my many years of being expected to recite the Apostles’ Creed from memory by a woman who was probably high with a cigarette in her mouth manifest themselves in this way: I’m not really religious and I am ambivalent about church except for the music, of which I have many secret playlists that I listen to on the regular, but I also don’t like to mess with “the devil.” I mean, he’s definitely not real, but just in case? I’m not fucking with a Ouija board or pretending to cast spells I don’t actually understand. I do believe ghosts can be real, especially because I have very little tolerance for “science” and like to leave inexplicable things unexplained. Life is just sexier and more mysterious when the flickering lights could be a poltergeist rather than a fluctuation in voltage or a loose cord.

Okay, so, in the wee hours of every morning, I would be jostled awake by this low-pitched hum, literally feeling my bed swaying beneath me, like I was Rose clinging to that Titanic door. My brain, molded by years of grainy exorcism videos on 20/20, immediately leaped to the conclusion that my apartment was haunted by a pissed-off demon. This was pre-cats, before I full became a spinster witch, so it wasn’t like I had a creature around who could tip me off. By the third or fourth night of this, I was sufficiently spooked, trolling Craigslist for mediums on my lunch breaks and googling “can you legally break a lease due to supernatural inhabitants.” Then I remembered Drex. And his advice to, you know, politely ask a ghost to leave. Sure, I could’ve looked up banishing spells or bought some potions from the occult store, but this is where I remind you that the lingering effects of Many Years of Bible School kept me from dabbling in any Satanry. Or perceived Satanry.

That night, I performed my usual evening routine: dinner for one consumed zombie-style over the sink; many episodes of reality television devoured with rapt attention, my face pressed against the screen; falling asleep fully clothed, with my phone in my hand. And there it was again, at two or three in the morning, a loud humming-slash-vibrating that made my bed quiver so hard I bolted upright the minute it started. I lay there massaging the sleep out of my weary eyes and suddenly remembered what Drex had said to do: acknowledge the ghost’s presence, then politely demand that he leave. Easy, right? Please pack your things and get the fuck out, sir, I have to be at work in four hours! I sat up and looked around to see if I could make out any floating Big Gulps or candy wrappers in the dim light provided by the street lamps in the alley my apartment overlooked. There were no tipped-over bottles or clouds of ecto-mist swirling near the baseboards, nothing other than that weird, ominous moaning and the rattling of the walls that accompanied it. I cleared my throat and in my most authoritative third-grade teacher voice said, “Okay, I hear you. I’m tired of this. Please leave me alone.”

The wailing continued. Louder, I declared: “I pay six hundred and ninety dollars to live in this asbestos closet and I don’t need a roommate. You have to leave!” The droning paused, and for a millisecond I felt like a capable person who could solve her own problems; then it came roaring back even more intensely. I am not so attached to living that I would willingly survive a supernatural terror that would torment me for the rest of my days, so I started feeling around in the sheets for a stray sock to asphyxiate myself with in case some monster with dripping fangs rounded the corner ready to eat me. Bitch, I can’t fight! When the zombies come or the aliens land or whatever dystopian shit that is bound to happen in our lifetime happens, I’m not stockpiling buckets of slop and batteries or any of that doomsday shit. I will be in the fetal position somewhere waiting for them to lobotomize me. I gave it one last try, plugging my ears with my fingers and shouting, “SHUT THE FUCK UP!” at the top of my lungs. The noise stopped immediately. I couldn’t even believe it! First, I couldn’t believe that I had anything in my useless collection of trash and novelty gifts that would be of any interest to someone who had actually been to hell, but more important than that, it seemed unfathomable to me that I could then convince that someone to leave my apartment! I am a horrible negotiator! I pulled the blanket over my head and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.

The ghost appeared to be gone for good; make me an honorary fucking Ghostbuster! A week later I was downstairs in the lobby deciding whether or not to take someone else’s Cosmopolitan magazine upstairs when this good-looking young dude in a cardigan smiled and said hi to me. He flipped his locks over his shoulder and noted my open mailbox door, then asked if I lived in 309. I don’t trust the motives of attractive people, so I just stared at him with my mouth open, hoping he would walk away and forget that he had caught me reading someone else’s steamy sex tips. “I’m in 409,” he said, unprompted. “Right on top of you.” Hot men know what the fuck they’re doing when they say shit like this, with their perfect teeth shimmering through their perfectly groomed beards. I was supposed to think about him grinding on top of me, WHICH I IMMEDIATELY DID. “Anyway,” he continued, “I heard you yelling the other night. Sorry about that. I didn’t know you could hear the reverb from my bass amp so much. I had a friend come soundproof my place. Has it been less noticeable?” And this is why I stopped taking my ass to church. Would a loving God actually humiliate me like this??

Samantha Irby is a writer whose work you can find on the internet.

Excerpted from Wow, No Thank You.: Essays , by Samantha Irby, just published by Vintage Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Samantha Irby.

Poets on Couches: Natalie Shapero

In this series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“Crash”

by Kay Ryan

Issue no. 151 (Summer 1999)

Slip is one

law of crash

among dozens.

There is also

shift—

moving a

granite lozenge

to the left

a little,

sending down

a cliff.

Also toggles:

the idle flip

that trips

the rails

trains travel.

No act

or refusal

to act, no

special grip

or triple lock

or brake stops

crash: crash

quickens

on resistance

like a legal system

out of Dickens.

Natalie Shapero is the author of the poetry collections Hard Child and No Object. She teaches at Tufts University.

Fathers Sway above It All

My father: my savior, my best friend, my confidante. Funder from afar of gymnastics lessons, giver of “kissies” over the phone, called me Princess, called me Peter Pan, photos of infant me sleeping on his chest, love of mine, I love you, dad. I call him with my good news, I call him with my bad. Picture him this way first, eyes squinting to nothing when he smiles. See his Vietnam photo with his hand raised like a wave or maybe saying stop, baby-man in combat, up all night forevermore drinking it away. Understand our lineage: newspaper clip from the early 1900s, Clem Bieker given ten lashes on his bare back for “wife-beating” but the whipping post did him no good. Say it runs in the blood, say it’s a generational disease, and it is, it’s all of that, our curse. Understand my father’s boyhood, hiding under tables while his father beat his mother. See him old now, body stooped, still unable to sleep, half a mind at war, ready for the next bomb to explode. See him hold my son with awe, hands shaking, hear him ask about my daughter, whole voice alight. See him this way first because it’s how I see him, somehow, despite everything.

*

After my mother left me when I was nine, I was made to give a testimony in front of a judge about our life and answer questions. I answered every single one truthfully. I don’t remember what I said, only that I was honest. That’s what my father told me to be. I was not in trouble. I just had to be honest. “Tell them what she put you through,” he said on our drive there. He had appeared the day before as if my desire itself had conjured him, picked me up and bought me new clothes for the occasion. Clean socks pulled up to my knees, a pale-yellow cotton shirt. Nothing smelled like me anymore, or like my mother’s cigarettes. There he was, my father, with me, there for me, saving me. He had flown to me from his job an ocean away, and it was time for the truth about my mother’s alcoholism. It was time to remove me for real, court approved. He had to make a grand gesture now that she had actually left, his letters with survival instructions at the bottom no longer enough for me to get through the dysfunction: If things get too bad there, remember—9-1-1.

Riding with my father, in the haze of my mother’s new goneness, I wondered, has he changed? Was it all a dream, the things he had done in front of me, the way my mother and I had once ran from him, hid under a semitruck in the parking lot of a state fair watching feet walk by, holding our breath for each set of feet because they could be his, and would he kill her this time? The man next to me crunching cinnamon Altoids could not have done that, or could he? Maybe it was my mother’s fault after all, making him that way. She pushes my buttons, he always liked to say, as if my mother had a special ability to summon the monster inside him. But she did seem to have that special ability. I had seen her say the very things we both knew would set him off many times. The traumatized child’s brain just wants logic, wants predictability. I was no different.

When my mother did not show up to the court hearing, I was given over to my father. I remember my grandmother and the way she looked at him with admiration. She liked to say often that my father had “stepped up.” But he felt it would not serve me to move around so much with his job. He worked long hours shifting to new projects every few years, and who would watch me? He’d have to hire a nanny. He’d have to look at me each day and figure out what to do with me. This scared him. He did not want to be around me so much, for fear of what could happen. I understood the fear clearly. I, too, did not want to be around him for more than a visit. For longer than it would take for the pork chops in canned tomatoes to be eaten; for several visits to Madame Tussauds and Ripley’s Believe It or Not!; to collect double samples at Costco and call it lunch; to buy a half a year’s worth of school clothes and, his obsession, a good winter coat, the puffier the better—he might not be able to conceal himself any longer. During the testimony, I was honest, but I never mentioned my father. It felt easy, good in fact, to leave him out of the story completely.

*

My mother’s absence in my life has always haunted me more than my father’s abuse, which is why I suppose I wrote a novel about a mother leaving a daughter. The father is off the page, a figment of memory, a floater in the eye. For a long while I have not been interested in fathers. I should say, I have not been interested in examining my own father through writing. Didn’t I sign a pact long ago during that car drive to the court house, perhaps a silent agreement to let it go, let it be, be cool baby? Women are all nuts, he liked to say, and he’d look at me special as if to say, but not you, and I’d laugh along with him, exempt from the women he meant, all those reckless button pushers.

But now, I want to write this out of love. Love, I have learned, does not mean staying hidden. Sometimes love brings it all up, gagging and ugly, to the rock-strewn shore.

*

After the judge awarded my father custody, I settled in at my mother’s parents’ house. My father, back at work an ocean away, began a routine of Sunday-night phone calls. I didn’t want anything more. Each night I looked forward to bedtime when I could go deep into my world of imaginary siblings: my twin sister, Claire, and our older brother (whose sole purpose was to bring around cute older boys and whose name now is not a part of my memory). They understood our parents and our situation. I was not alone when they were there and we could huddle under the covers. We knew in our bones that our mother would eventually return for us and it was consolation enough to drop me into a thin and ragged sleep. We were like children in movies, wise and crafty, so much smarter than the adults.

At my grandparents’ I ate chicken sandwiches on whole wheat bread for lunch and drank cool, clean water from glasses with little stars on them. My grandmother penned a swooping heart on my lunch bags. Home lunch like the rich kids. I didn’t hang out at the liquor store after school each day anymore, watching the little TV in the corner for hours on end while my mother looped her skinny arms around the owner’s neck, sometimes sitting on his lap behind the counter. The owner’s wife would emerge from the back to offer tea-leaf readings while my mother drank big plastic cups full of whatever they could spare that day. She was like their child and I was an accessory of hers that was very, very good at staying quiet.

I wanted sometimes to break away from my grandmother as we headed into Savemart to shop for our wholesome groceries, and let the owners at the liquor store know I was still alive, that my mother had left and was with a strange man in Reno, but we were not dead. They were always worried about her dying. I’d send him heart messages: Don’t worry! I’d mind-transport Claire over to tell him, and later she would report back that everything was fine.

But eventually, as years passed, so much more time than I ever imagined my mother would be away, I didn’t think of the liquor store quite so often. I didn’t think of those three years I was alone with my mother after she had left my father or the times before that, the things I’d seen my father do to her when we lived in Hawaii. Did I remember the time I begged the police to help us and my mother looked them in the eye and said there was nothing wrong in our home, black eye glistening? In a community college English-class journal my mother’s concerned teacher writes in the margin, You need to leave him! Think of what this is doing to Chelsea.

*

In time, the before-life was reduced to small shocks, little daytime nightmares like it all had never even happened, or if it had, it had happened in some other realm, separate. My grandparents’ house was lovely with blond-wood vaulted ceilings, a huge white-tiled island in the kitchen, a certain smell that even now, the house gone to other people and horrifically remodeled from its beautiful airy state, I wish I could smell once more. The smell of order, the possibility of biscotti baking, natural light twinkling off the glass prisms hanging in the dining room window. A mansion to me then, a palace. My mother had always made me feel like her accomplice, a partner in the show of her life and not a child at all. But now I had escaped. My mother was still out there in the shit but I had become accustomed to my fine nutrition, breathing unsmoked air and wearing matching separates from the local department store my grandmother loved, Gottschalks. Also, I had a deeper meaning now, something neither of my parents had, something that I had tried to push on them for the majority of my youth, mailing Bibles with desperate pleas that they get saved tucked into the pages.

Church was nonnegotiable with my grandparents even though each Sunday morning before service my stomach would cramp and pull me into my knees on the ride there, begging to turn around. We never turned around. I can’t go, I’d wail. Can’t stuck in the mud, my grandmother would say, her outfit pristine, her hair a gorgeous architecture of blonde swoops. I was so unassuming that the youth pastor reintroduced himself to me each week, as if he’d never seen me before in his life. From the bleachers in the kids’ group, I’d sit alone or with one other girl named Ally. If she was not there, the entire thing was ruined. But slowly, in that huge gymnasium with booming music, it began to seem my old life could barely have occurred at all. And here was another way paved in gold. I took to the story of the Lord as if my life depended on it.

If I wanted to ever breathe properly, to ever achieve my goal of salvation, I had to let someone off the hook. I could not manage an expanding anger for both parents at once. And God was here to say that I wasn’t really entitled to be angry at anyone at all, and I should just forgive. And my father was never the person society, or perhaps biology, had taught me to long for in a mother anyhow: protector, mender, teacher, soft and loving warm shoulder, there at bedtime, desireless body housing the solutions to my needs. My father could have any number of desires, but my mother’s desire was in direct conflict to my safety, in conflict to the idea of “mother” I had been taught I deserved. She desired alcohol and terrible men, it seemed. Her desire was not desire, of course, but addiction, but the labels don’t matter in the actual movements of living and growing up. Action, regardless of origin, looks like want.

*

Anything fathers do that is not abandonment or abuse is lauded as extraordinary. My husband, wearing my son in an Ergobaby and pushing my daughter in the stroller could stop traffic for miles, people screaming and clapping out their windows at him for being such a wonderful and resourceful man, caring for his children! And when I do the same thing, on a daily basis, and do it in the grocery store, boob in baby’s mouth at the same time, I get no response, or perhaps even: “He’s too big to be in that thing still, isn’t he? Or, “Uh-oh, someone needs a nap,” when my daughter howls for fruit snacks, the comment not directed at my daughter at all but instead at me, the thoughtless mother who didn’t nap my child at the right time. But my husband, holding a screeching animal of a kid, is endearing, astonishing, a man caught in an act of selfless courage.

“Fathers,” Mona Simpson so beautifully writes in her novel My Hollywood, “sway above it all, tall trees.”

*

My daughter loves workbooks. We do them together. Recently a lesson presented itself about the difference between facts and opinions. Here’s the fact I do not use as an example, but I think it: Growing up my father beat my mother. It is the opposite of opinion. In church or with my grandparents, I tried not to think about it. In church, I was told that God heals the past completely, so I took this to mean “forget it all.” Or else I would be the punished one, the one at fault. But I am coming to understand that we do not, will not, forget. Things rise. Lately they sit on my chest at night, pressing me down. I feel them move into my hands sometimes, a tingly shake. I write these memories into essays, and delete the parts about my father. But now, I want to get it all out. I don’t want to carry it any longer. Can I put it here? I hope.

*

My mother and I called my father the “ticking time bomb.” After an explosion, a beating, a display of violence, my father would have about two days of remorse and denial before he began to climb toward the red zone again and the bomb would go off. It was so predictable. All she had to do was smile at the waiter. All she had to do was buy herself new Jordache jeans. All she had to do was exactly nothing. My mother and I spoke of my father like we were necessary passengers on his ship, like comrades working side by side. I was her equal, her protector. I held hope we might get away from him. My mother seemed to wax and wane with her seriousness about leaving, something I could not understand as a child and something that infuriated me. Back to that system of logic: If someone hits you, you should leave that person. It felt true to me then, watching her be brutalized regularly. When we finally did leave, when I was six, I thought yes, now real life can begin. But being beaten for years and years and told you are worthless, worthless scum leaves its mark. My mother, without my father around anymore to remind her of these things, sailed into further destruction. Sailed farther away from me.

*

I’m an adult woman. I’m in my thirties now and my partner does not beat me. He has never laid a hand on me, has never said, Fuck you, or called me a worthless slut, or a bitch. He has never cut my clothes with a pocket knife or wrapped the long strap of my purse around the steering wheel of the car as I drove on the highway. He has never dumped my bag out on the ground in a crowd, he has never hit the back of my head exclusively so that the bruises wouldn’t show under my hair. My husband has never done that. My father did that to my mother. Did he? Could he really have?

I don’t want to be trapped anymore by the story of my father. My good father, my father I love, the story of my father that we painted over the past once my mother was no longer around. I wonder if my hands are big enough to hold the two truths of him—what he has done and what he has done. I do not see a bad person when I look at him. Only sometimes do I see him spitting on her crouched body, throwing a plate against a wall, pushing me out of the way so he could get to her. Sometimes I see both the good and bad side by side, inseparable like two snakes entwined. I know that my father’s goodness does not negate his actions, though when I was a child it seemed it did. On our biannual visits, sitting on a bench in San Francisco, cracking crabs and eating with our hands, laughing and telling jokes, I wondered if I had completely made up the years of abuse. He was able to settle into this idea, too, I’ve always believed. He liked the way I would never mention that time. When he said, as he still to this day says, “I just wanted us to be a family, but your mother didn’t want that,” I would nod. But has he forgotten? See his hand shake while he opens another beer. See him, in a rare moment of lucidity, desperately trying to explain where this part of him comes from. He looks like someone peeking from behind a curtain, but only for a minute. The show must go on. Play any Van Morrison song, mention where we used to live in Hawaii, say the words of the past, and his tears will come up wild and forceful and he will go silent, look away, away. See him sitting alone in his red truck all day long nodding in and out of sleep while the radio plays on. You tell me who can’t forget.

Chelsea Bieker’s debut novel, Godshot, is out this week from Catapult.

March 31, 2020

Redux: My Definition of Loneliness

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

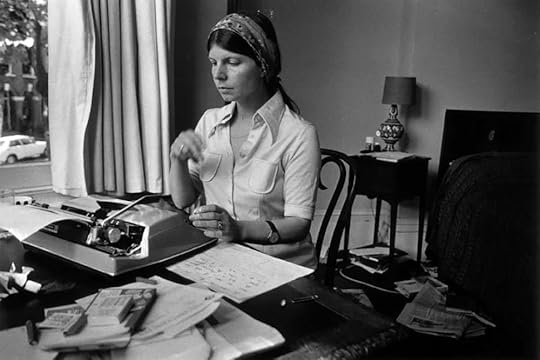

Margaret Drabble.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re feeling a little bored. Read on for some literature that answers our need for stimulation: Margaret Drabble’s Art of Fiction interview, Georges Perec’s short story “Between Sleep and Waking,” and Mary Ruefle’s poem “Milk Shake.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the second edition here, and then sign up for more.

Margaret Drabble, The Art of Fiction No. 70

Issue no. 74 (Fall–Winter 1978)

I wrote my first novel because I just got married and I was living in Stratford-upon-Avon and there was nothing else to do. I was very bored. I had no particular friends there. I’d been very busy up until then—at university, passing examinations—I very nearly took a job that summer and if I had taken a job, I probably wouldn’t have written the book. So in a sense it was accidental. Whether I would have written a novel later, I just don’t know.

Between Sleep and Waking

By Georges Perec

Issue no. 56 (Spring 1973)

For the time being your mind is absorbed by a task that you must perform but that you are unable to define exactly; it seems to be the sort of task that is scarcely important in itself and that perhaps is only the pretext, the opportunity, of making sure you know the rules: you imagine, for example, and this is immediately confirmed, that the task consists of sliding your thumb or even your whole hand onto the pillow. But is doing this really your concern; don’t your years of service, your position in the hierarchy, exempt you from this chore?

Milk Shake

By Mary Ruefle

Issue no. 216 (Spring 2016)

I am never lonely and never bored. Except when I bore myself, which is my definition of loneliness—to bore oneself. It makes a body lonesome, that. Today I am very bored and very lonely. I can think of nothing better to do than grind salt and pepper into my milk shake, which I have been doing since I was thirteen, which was so long ago the very word thirteen has an old-fashioned ring to it, one might as well say Ottoman Empire.

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

Dorothea Lange’s Angel of History

The following essay appears in Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures , a catalogue produced to accompany the exhibition of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art.

Dorothea Lange, Berryessa Valley, Napa County, California, 1956, gelatin silver print, printed 1965, 11 1/8″ × 11 1/2″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.

This woman seems to have been standing in the meadow forever, with it and of it, welcoming us all, an earthbound archangel of the topsoil. You could imagine that below her housedress her feet have taken root or her torso has become a tree trunk, and the way she smiles and reaches out that right hand seems like the most generous way to say that this place is hers.

Everything in the picture affirms a sense of stability. The square photograph is bisected horizontally by the straight line where the flowering meadow joins the bare hill on the right and the tree-covered hill on the left that rise up from either side of her like wings. That line is even with her bosom, and her outstretched hand seems almost to rest on it. Her body is the vertical axis accentuated by the inset panel of her dress. It could seem like a moment in cyclical time, the time of the seasons and the years coming one after another, of the eternal return, and seen in isolation that might be all you’d know: an older woman with a radiantly kind face reaches out welcomingly from the heart of an idyllic California landscape.

As is so often the case with Dorothea Lange’s photographs and maybe with nearly all photographs, the meaning of the image comes in part from beyond the frame. Captions constitute the immediate context, and series and sequences or longer texts the larger one. When Lange published the portrait, it was the opening image inside a 1960 special issue of Aperture magazine titled “Death of a Valley.” (The project had been commissioned a few years earlier by Life, which then declined to publish it.) The woman smiling in the midst of pastoral calm was saying hello to the viewer; she and Lange and Pirkle Jones, who worked with Lange on the documentary project, were saying goodbye to the Berryessa Valley and the town of Monticello.

The text declares, “Demands for more water caused the death of the Berryessa Valley. It disappeared 125 feet deep behind a dam in order to store water for the bigger valleys below and to provide industrial water for the expanding cities.” Then comes the photograph here, on a right-hand page, with, on the left side, “It was a place of cattle and horses, of pears and grapes, alfalfa and grain. It had never known a crop failure … And the valley held generations in its hand.”

That last line all but makes this woman with her outstretched hand the valley itself. And then come the increasingly disturbing photographs as this idyll is wrecked, scraped, burned, and drowned. This was the small valley just east of the famous Napa Valley—sheltered, fertile, warm, doomed to be dammed to hold water for bigger agricultural regions to the south and east. A few pages later, a house is being moved and a farm auction is being held. The men and children in summer clothes are better dressed, more substantial, than the famous Lange subjects from earlier projects, but this is still about displacement.

In 1937, Lange photographed six displaced tenant farmers in Goodlet, Texas, strong men with grim faces standing on bare earth in front of an unpainted wooden structure. On March 27, 1942, in San Jose, California, she photographed a Japanese American farmer sitting on what appears to be a porch: “A young celery grower … who has just completed arrangements for leasing his farm during evacuation.” His sisters flank him in the background, and the white man who’s presumably worked out the arrangements with him looms. The vanishing point architecture boxes him in, and one of his sisters in the background leans against a mattress tipped up against the wall. They’re both uprooted and trapped, the composition says.

Sometimes her uprooted people landed well—the black shipyard workers of Richmond, California, were often escaping sharecropping in the south, but sometimes they had not landed, and perhaps some of us from that era of uprooting never will. In our current era of uprooting, thanks to economic policies that have created mass homelessness again in California and crushing debt across the nation, Lange’s images seem immediate, urgent, thorny again, questions that demand answers.

There’s no such ominousness inside the photograph here of the woman in the Berryessa Valley, but starting with Lange’s White Angel Breadline photograph of 1933, displacement was one of her perennial themes. The Berryessa people weren’t displaced by ecological failure, poverty, or racism, though: they were ousted by development. Further along in “Death of a Valley” comes an image showing two old family photographs lying on a dusty wooden floor in, the caption tells us, an otherwise empty, abandoned house. Then come the exhumed graves and the giant oak tree toppled, the fires, the famous frightened horse—a white horse moving across dusty, distressed ground: “Just raw and mutilated earth remained.”

Moving from image to image in “Death of a Valley,” you come back and see that this sturdy countrywoman is a rustic western version of Walter Benjamin’s angel of history. “The angel would like to stay … and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them.” This time the violence is called progress and the industrialization of agriculture and the control of nature. This time the woman smiles warmly from a valley floor that has been underwater ever since.

Rebecca Solnit is the author of more than twenty books, including A Paradise Built in Hell, Men Explain Things to Me, and, most recently, Recollections of My Nonexistence: A Memoir. She lives in San Francisco.

Excerpt from Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The Fabulous Forgotten Life of Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West

How preposterous is it that Vita Sackville-West, the best-selling bisexual baroness who wrote over thirty-five books that made an ingenious mockery of twenties societal norms, should be remembered today merely as a smoocher of Virginia Woolf? The reductive canonization of her affair with Woolf has elbowed out a more luxurious, strange story: Vita loved several women with exceptional ardor; simultaneously adored her also-bisexual husband, Harold; ultimately came to prefer the company of flora over fauna of any gender; and committed herself to a life of prolific creation (written and planted) that redefined passion itself.

Take as a representative starting point the comically deranged splendor of Vita’s ancestry. Her grandfather Lionel, the third Baron Sackville, fell in love with Pepita, the notorious Andalusian ballerina, and by her fathered five illegitimate children. When Lionel became the British minister in Buenos Aires, he sent those children to live in French convents. Upon transferring to the British Legation in Washington, DC, he summoned his nineteen-year-old eldest daughter to serve as his diplomatic hostess. Vita’s mother charmed Washington senseless with her bad English and so-called gypsy blood, receiving alleged marriage proposals from the widowed President of the United States Chester A. Arthur, Pierpont Morgan, Rudyard Kipling, Auguste Rodin, and Henry Ford. Somehow, from among these suitors, she chose to marry her first cousin, another Lionel. She returned to England and gave birth to their only child, Vita Sackville-West, on March 9, 1892.

By the age of eighteen, Vita had written eight full-length novels and five plays. She describes her childhood self in a diary as “rough, and secret,” frequently punished for “wrestling with the hall-boy,” fondest of her pocketknife, and inspired to start writing at age twelve by Cyrano de Bergerac. Still, when she formally entered society at age eighteen (“four balls a week and luncheons every day”), she was seen as a refined beauty, and took after her mother in attracting various glossy admirers. First among the failed wooers stood Lord Henry Lascelles, Sixth Earl of Harewood and first cousin of Tommy Lascelles, everybody’s favorite right-hand mustache in the Netflix series The Crown (when Vita rejected Lascelles, he married the Princess Mary, sister of King George VI).

But Vita wasn’t dazzled by men of great heritages or homes. She grew up at Knole, the Sackville estate, built in 1455 on a thousand acres and said to contain fifty-two staircases. More saliently, she was already smitten: with Rosamund Grosvenor, “the neat little girl who came to play with me when Dada went to South Africa.” Vita’s son Nigel (more on Nigel later—I have the utmost respect for Nigel) learned of this affair and many others when, after Vita’s death, he opened a locked gladstone bag in her sitting room and discovered her sensational written confessions.

Vita and Rosamund developed a quick intimacy, with ample time alone together granted by unsuspecting chaperones. Vita had no concept of homosexuality as such—her instincts toward Rosamund seemed as ordinary as her penchant for tromping through bogs: an after-school hobby. She compared Rosamund’s company to that of the society men she met at balls, as if—radical thought—all companions were equal and comparable, gender immaterial, apples to apples. “Even my liaison with Rosamund was, in a sense, superficial. I mean that it was almost exclusively physical, as, to be frank, she always bored me as a companion. I was very fond of her, however; she had a sweet nature. But she was quite stupid. Harold wasn’t.”

Harold Nicolson proposed to Vita at the Hatfield Ball in January of 1912, having never kissed her (“He was very shy, and pulled all the buttons one by one off his gloves”). He had recently become the youngest admitted officer in the diplomatic service, the start of a virtuosic foreign office career of global impact. Vita spends little diary space describing her wedding, “because it is the same for everybody,” but the event sounds far from typical: Vita decorated the Knole chapel to look like “a theatre,” her mother stayed in bed because she didn’t like “being émotionée,” and Vita’s two girlfriends, Rosamund and Violet, suffered immeasurably (Rosamund standing directly behind Vita as her bridesmaid) while matrimony reigned supreme.

I haven’t yet mentioned Violet Trefusis because their affair is an insane fable featuring “an acrobat with no arms or legs” that warrants its own encyclopedia, but here we approach their story’s climax and so the whole thing must be explained, if abbreviated. They met as children while visiting a friend with a broken leg. They discussed their “ancestors,” and before leaving, Violet kissed her. The proprietary rush that lanky, unpopular Vita felt in claiming “this extraordinary, this almost unearthly creature” as her friend would evolve, over the next fifteen years, into a mutual psychosexual obsession.

To Vita, Violet was unreliable, irritating, and perfect; but Harold was “unalterable, perennial, and best.” When Vita went ahead with her conventional marriage to Harold, Violet agreed to an unconventional marriage to Denys Trefusis, a man who’d promised to marry her on platonic terms. This created the first fundamental difference between the two lifelong friends: Vita loved her husband; Violet did not. Vita and Harold never expected exclusive heterosexual passion from each other, having admitted their similarly “dual” orientations, but championed their spiritual union absolutely. The greatest test of their marriage came in April of 1918, when Violet wrote to Vita to ask whether she could visit for a fortnight. “I was bored by the idea,” Vita writes, “as I wanted to work, and I did not know how to entertain her.” Yet Violet came, and a week into her stay, Vita tried on one of the estate’s farmhand outfits—breeches and gaiters. “I looked like a rather untidy young man, a sort of undergraduate,” she writes. This look unexpectedly activated some long dormant spell, and they were intoxicated.

The next two years played out an opera of the highest stakes. While Harold went to Paris to, you know, write and sign the Treaty of Versailles, Vita and Violet sprinted to Monte Carlo, where Vita cross-dressed exclusively as a wounded war soldier named Julian, and wrote the first draft of her great novel of independence, Challenge. For four months, the women were so violently happy together, they became furious at each other’s husbands (“I treated her savagely, I made love to her, I had her, I didn’t care, I only wanted to hurt Denys”) and decided to elope, society and obligations be damned. Vita drafted a sort of last will and testament—as if Vita Sackville-West were legally dying, to be survived by Julian—and crossed the Strait of Dover by ferry to join Violet in Calais, France.

By this point, everybody knew everything. In accordance with the mutually encouraging nature of their partnership, Vita had confided in Harold every step of the way (“I am trying to be good, Hadji, but I want so dreadfully to be with her”). On Valentine’s Day, 1920, the husbands flew by two-seater plane from island to continent to retrieve their wives at a hotel in Amiens. In his later account of his parents’ crisis, Nigel endearingly wonders, “How did Denys happen to have a two-seater aeroplane? When had he learned to fly?”

Violet starved herself; Denys cried; Harold had just drawn the new national boundaries of modern Europe only to find himself in a private circus of irreconcilable conflict; and the episode’s finale came when Violet admitted that she’d had sex with her own husband, Denys, the night before fleeing to France. Vita couldn’t abide this lapse, and called it betrayal (one of Vita’s lowest moments of hypocrisy, as she had already borne Harold two sons). The exchange was so profoundly and symmetrically embarrassing that the quartet reacted by reverting to “normal life,” which once again recommended itself as at least a source of sanity. By 1923, Harold and Vita had resumed their “firm, elastic formula,” Violet had returned to Denys, and a new affair stood on Vita’s horizon—this time with a man, the writer Geoffrey Scott.

Scott inscrutably “lived in the Villa Medici” overlooking Florence, (these were the days when one could casually live in what is now a UNESCO World Heritage site) and proved to be one of Vita’s sharpest readers and editors. Harold was “rather pleased” by this one, because he felt Scott “enriched Vita’s mind instead of confusing it.” It seems that within this highest tier of social rank and literary ambition, a feeling of intellectual kinship could translate without restraint into romantic action, openly and productively. Vita was working on her Hawthornden Prize–winning epic poem The Land. She’d also begun her extensive parallel career in garden design, and drew inspiration from Scott’s olive groves. She enjoyed his admiration, affection, and critique until his wits were outmatched by a more formidable mind: Virginia Woolf’s.

Here again Vita maintained her life philosophy of meritocracy in mating: she ignored the most pressing and oppressive cultural expectations in order to award her attention to the most currently excellent candidate. It didn’t matter who, where, what gender, or how married this person might be. The entire Sackville-West family embraced Virginia with warmth and appreciation. Nigel thought of her as “delicate, but in the cobweb sense, not the medical,” and Harold expected Virginia to open in Vita “a rich new vein of ore.” Vita lamented Virginia’s orange wool stockings (“she dresses quite atrociously”), and both she and Harold feared that Virginia didn’t possess the emotional resilience to bear Vita’s seduction without collapse. “I am scared to death of arousing physical feelings in her,” Vita wrote to Harold, “because of the madness … I have gone to bed with her (twice), but that’s all.”

Virginia saw in Vita a symbol of history and consequence. In an extraordinary diary entry, Woolf writes, “Stalking on legs like beech trees, pink glowing, grape clustered, pearl hung… There is her maturity and full breastedness … her capacity … to represent her country … to control silver, servants, chow dogs; her motherhood (but she is a little cold and off-hand with her boys) her being in short (what I have never been) a real woman.” The unmitigated brilliance Vita worshipped in Virginia, and the timeless sophistication Virginia in turned revered—I find this loop almost eerily moving, a moment in which grace best beheld itself.

Virginia documented the Sackville-West spectacle in her 1928 novel Orlando, which flings Vita from century to century and from sex to sex—now a young Elizabethan lad, now a lady ambassador to Constantinople—and concludes with an outright photograph of Vita at her house with her dogs. Woolf here invented a fiction-biography fusion that, in our discussions of contemporary autofiction, we tend to imagine is brand new. Virginia depicted Violet as a flighty Russian princess in Orlando, and Violet in turn wrote Broderie Anglaise, a cutting novel that belittled Virginia and Vita’s romance. In 1930, Vita published her own best-selling novel The Edwardians, a takedown of aristocratic society at large. It’s a masterpiece that nobody ever reads. The prose is cheeky, confident, formally irreverent, revelatory, and as evocative of time and mood as Woolf’s, but posterity saw fit to preserve only one midcentury woman writer whose name began with V.

Vita lived until 1962, Harold until 1968, married in the “sheer joy of companionship.” Harold slept with men while stationed abroad, and Vita did Vita; still, she crossed the Bakhtiari Mountains on foot through a hailstorm to reach his Persian post. Almost incomprehensibly prolific, they wrote a combined total of over seventy books. In her novel Heritage, Vita writes, “Serenity of spirit and turbulence of action should make up the sum of man’s life,” and alongside her literary labors she relied on the tranquility of botany, a study she found bottomless in its yield and mystery. The natural world staged its own wars of the sexes for her amusement: “You must insist upon getting a male plant, or there will not be any catkins. The female plant will give you only bunches of black fruits.” And a zinnia seedling could prove a model of self-sufficiency: “It will do all the better for being lonely.” Her gardening column for the Observer continued until a year before her death.

Which brings us to Nigel. Nigel opened that gladstone bag and spent ten years wondering what to do with his mother’s story.

“The psychology of people like myself will be a matter of interest,” Vita had written in the document, “and I believe it will be recognized that many more people of my type do exist than under the present-day system of hypocrisy is commonly admitted. I am not saying that such personalities, and the connections which result from them, will not be deplored as they are now; but I do believe that their greater prevalence, and the spirit of candour which one hopes will spread with the progress of the world, will lead to their recognition.”

Nigel found these remarks actualized already in seventies England. How far there still was, and is, to go. He added some of his own fine prose, excerpts from his father’s diaries, and select historical supplements, to produce his tour de force, Portrait of a Marriage, in 1973. I have even more admiration for his work as a feat of material organization, after writing this essay, which has been so overburdened by material that I couldn’t even return to the armless, legless acrobat.

What most inspires me about Vita’s mode and model of living is her capacity to participate in her own society at the highest level, capture and comprehend it, and then systematically correct the limitations and small-mindedness she perceived. A century later, I hope for a Sackville-West readership revival—her courage is powerfully instructive. Challenge was too provocative to be published in the UK during Vita or Violet’s lifetimes, but it appeared in the U.S. in 1923. I took its epigraph, three love lines to Violet veiled in Romany-Turkish, as the epigraph of my novel Hex, decoding the Turkish back to English: “This book is yours, my witch, read it and find your tormented soul, changed and free.” One witch need no longer hide her love for another witch under foreign tongues. I asked my Romanian mother to check the translation, but she patiently reminded me that Romany and Romanian belong to two totally unrelated language groups.

At home around the very old farmhouse where my husband and I live in New Hampshire (only one staircase, but to this Manhattanite unaccustomed to “houses” altogether, it feels like fifty-two of them), I plant next year’s flowerbeds according to Vita’s designs. I don’t know the first thing about gardening, but her columns are teaching me the first, second, and forty-fifth. “We now approach the time of year when the thoughts of Man turn towards the pruning of his roses,” she writes. “The only thing is to be bold; try the experiment; and find out.”

For more, read our Feminize Your Canon column about Violet Trefusis.

Rebecca Dinerstein Knight is the author, most recently, of Hex , out today from Viking.

March 30, 2020

Quarantine Reads: Dhalgren

In our new series Quarantine Reads, writers present the books they’re finally making time for and consider what it’s like to read them in this strange moment.

I started reading Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren, a prismatic, nightmarish work of speculative fiction, in New York City a couple weeks ago, when the coronavirus had just begun to spread into the West. Italy had fallen and the threat in the United States was imminent, but the real panic and anxiety still hadn’t sunk in. Stubbornly, and against better judgment, I decided to go through with my plans to take a three-week trip to Japan. I continued reading Dhalgren on my way to Tokyo on March 14. As I was reading on the nearly empty plane, I kept looking down at my hands, getting up, washing them, until they were dry and cracked and my knuckles started bleeding, and by the time I disembarked it looked like I’d been in a fistfight. Dhalgren has been my only real traveling companion this week: gently purring in my hands with the landscape tilting outside the window of the Shinkansen; in the coffee shops of Ginza and Shinjuku, wiped with sanitizer each time, carefully, front and back; and in my lap on a park bench overlooking a river, across which stands the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the battered dome of a ruined building.

The German-language writer Elias Canetti—most famous for his book Crowds and Power—deeply admired Dr. Michihiko Hachiya’s Hiroshima Diary, a powerful and lucid account of the days and weeks following the Hiroshima atomic bombing. In a short essay from 1971, Canetti wrote of Dr. Hachiya’s profoundly vivid hellscape, of the uncertainty each new day brought to the doctor’s treatment of victims (while trying to understand what was happening to his own body), and of the doctor’s narration of the ever-shifting new realities of something completely unknown. As Canetti writes, “In the hardship of his own condition, among dead or injured people, the author tries to piece the facts together; with increasing knowledge, his conjectures change, they turn into theories requiring experiment.”

It had been years since I’d first read Canetti’s essay, but the notion that I should reread it popped into my head while I was distractedly strolling through the crowded Hondori shopping district of Hiroshima. It’s difficult, of course, not to jam the coronavirus into every thought, and I couldn’t help but draw connections to the bombing of Hiroshima—and to a fleeting question that Canetti poses in this essay: “Is misfortune the thing that people have most in common?” Walking around Hiroshima today, with the scars of its past barely concealed to anyone looking for them, I noted the surreal and incongruous way the city still functions normally despite the threat of the virus. The city’s past—even the name, Hiroshima, evokes carnage and loss—seemed to offer a brief moment of perspective: bacteria, an invisible terror, feels somehow less threatening when reminded of this human atrocity, of our capacity to inflict destruction upon ourselves.

One of the things that Canetti found most captivating—and horrifying—in Hiroshima Diary was that it was written in real time, as the events unfolded. This sense of narrating and revising the shifting facts resonated with me, not only because of the strange state of the world, but also in thinking about Dhalgren, which, though I’ve been reading every day for the past couple weeks (but don’t these weeks feel like years?), has felt at times impenetrable, surreal, frustrating, unpredictable. Dhalgren eludes me at every turn—I have a notebook now nearly full of scribblings and half-baked ideas about themes I’d wanted pick apart (about hygiene, the uncanny, mythology, race, migration, disaster, et cetera). I keep trying to wave the book in the air to see if the coronavirus waves back.

Dhalgren takes place in the fictional city of Bellona, a city that once had a population of two million but because of a strange disaster (a series of fires? a race riot?), there are only about a thousand inhabitants left there. In general, Bellona is a pretty dangerous place to find yourself: people die unexpectedly; acts of violence or debauchery occur randomly and often; and a gang of thugs, called the Scorpions, run the streets by night. To stay safe, it’s best to wear an orchid, a bladed weapon that I imagine looks like the Wolverine’s fist, if you have one.

Soon after arriving in Bellona, Kidd (or Kid, or the kid—he’s not even sure of his own name) meets Tak Loufer, who, in these first pages, serves as a guide to the ravaged city. Laufer explains, “You know, here… you’re free. No laws, to break or to follow. Do anything you want. Which does funny things to you. Very quickly, surprisingly quickly, you become… exactly who you are.” Kidd, is, as he soon discovers, a poet. But he is also a nomad, a flaneur, an adventurer, an eyewitness.