The Paris Review's Blog, page 175

March 30, 2020

Poets on Couches: Maya C. Popa

In our new series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“Monet Refuses the Operation”

by Lisel Mueller

Issue no. 84 (Summer 1982)

Doctor, you say there are no haloes

around the streetlights in Paris

and what I see is an aberration

caused by old age, an affliction.

I tell you it has taken me all my life

to arrive at the vision of gas lamps as angels,

to soften and blur and finally banish

the edges you regret I don’t see,

to learn that the line I called the horizon

does not exist and sky and water,

so long apart, are the same state of being.

Fifty-four years before I could see

Rouen cathedral is built

of parallel shafts of sun,

and now you want to restore

my youthful errors: fixed

notions of top and bottom,

the illusion of three-dimensional space,

wisteria separate

from the bridge it covers.

What can I say to convince you

the Houses of Parliament dissolve

night after night to become

the fluid dream of the Thames?

I will not return to a universe

of objects that don’t know each other,

as if islands were not the lost children

of one great continent. The world

is flux, and light becomes what it touches,

becomes water, lilies on water,

above and below water,

becomes lilac and mauve and yellow

and white and cerulean lamps,

small fists passing sunlight

so quickly to one another

that I despair, my brush not being

long, streaming hair. To paint

the speed of light! Doctor,

our weighted shapes, these verticals,

burn to mix with air

and change our clothes, skin, bones

to gases. If only you could see

how heaven pulls earth into its arms

and how infinitely the heart expands

to claim the world, blue vapor without end.

Maya C. Popa is the poetry reviews editor of Publishers Weekly and the author of American Faith.

March 27, 2020

Staff Picks: Puddings, Pastels, and Plano

Still from Autumn de Wilde’s Emma.

The coronavirus has thrown a wrench into Aries season, but plans for my March birthday remained unchanged. I watched Autumn de Wilde’s new adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma entirely alone. I am a harsh critic when it comes to film versions of Austen and consider myself a purist—a champion of the Pride and Prejudice BBC miniseries, which culminates in Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy diving into a pond at Pemberley, scantily clad by Regency standards. As far as Emma is concerned, I am a tried-and-true disciple of Clueless and find Cher Horowitz hard to match, even by a silky-skinned, pre-Goop Gwyneth Paltrow in the 1996 version. Anya Taylor-Joy, however, is the perfect Emma, exuding a quiet, even intimidating confidence; her tight blonde curls and perky ruffs are a flawless manifestation of her character. Emma’s world, too, is an appetizing spectacle in de Wilde’s film, the walls of the Woodhouse estate painted in decadent pinks and greens. To match, every inch of the banquet tables is covered in absurd towers of cakes, puddings, and tarts. Against my recent sluggish tendencies, Emma has inspired me to action. I will surely emerge from this quarantine an accomplished lady with a penchant for matchmaking, clad in only hand-stitched ruffs, and always poised for a contra dance. —Elinor Hitt

What’s more exciting about having a mutual crush than the unspoken lexicon of codes and signals that you both somehow know to employ? Like the lingering glances when you pass each other in the hallway. It’s a touchstone of high school life, and so it is for Olivia, the eponymous protagonist of Dorothy Strachey’s 1949 novel about a teenager who develops a crush on the headmistress of her new boarding school in fifties France. Coded language is essential to LGBTQ literature of a certain era, though I’d argue that Olivia has a relatively heavy hand (possibly because Strachey wasn’t certain it would ever be published). Olivia’s vivid desire is interwoven with the enlightenment of her education (the moment she falls in love is when Mlle Julie reads aloud from Jean Racine’s Andromaque). The complications of the boarding school’s all-female world, its relationships and jealousy, soon unfurl into tentacles that threaten to strangle all involved. But through the melodrama cuts the fresh frankness of Olivia’s all-consuming ardor, and in her Strachey captures perfectly the urgency, excitement, and fire of a first adult crush. —Lauren Kane

Still from Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers.

This week, as news of stubborn college students flooding Florida and Gulf Coast beaches made the national news, I’ve been thinking a lot about Harmony Korine’s 2012 film Spring Breakers. It’s a trip, on many levels—the classic road trip story of four coeds (including, notably, Selena Gomez) escaping the rigid confines of their Christian college for a memorable week on the beach. Also trippy: the bacchanalian scenes, shot with glee (fair warning: there is a lot of booty) and a tremendous eye for color (Korine seems to have mainlined the pastels and neons of Miami Beach). Trip number three: James Franco playing a high-ish roller named Alien—it’s a bombastic role, played with relish, and a lot of fun to watch. Of course things go sideways, operatically so. Come for the vicariousness; stay for the cautionary tale. I don’t wish ill will on any undergrad, and it’s unfortunate that spring break (along with book tours, major league baseball, and a million other things we were looking forward to) got canceled, but after watching Spring Breakers again, I am more confident than ever that sometimes it’s best to stay off the beach. —Emily Nemens

Last year, the nominees for the Goldsmiths Prize in experimental writing included the intriguingly named Good Day?, by Vesna Main, a Croatian writer living in London. I hadn’t heard of her, but descriptions of the plot intrigued me, and so I hastily started to search for more information about Main’s work. Described by her publisher as “variations and fugue on the theme of obsession,” her 2018 short story collection Temptation: A User’s Guide is a witty compendium of recalibrations of Modernism, from “Mrs. Dalloway”—a sly contemporary take on Virginia Woolf’s classic—to “Love and Doubles,” whose fascinating thesis concerns the plagiarism of desire. Along the way, Main explores violence, obsession, and love in a series of stories that are as clever as they are formally interesting. —Rhian Sasseen

The adrenaline started way before the lights came up and has never faded. This past spring, my gentleman and I realized we had one last chance to see our genius friend Taylor Reynolds direct a play in our own neighborhood. We had ten minutes. We made it. Were there seats? We were on standby. Then we were sitting front row, stage left, and I have never been more scared nor laughed harder in a theater—screen or stage. We were watching Plano, by Will Arbery, who won a Whiting Award on Wednesday night. I wish I had been in a room of people to shout at the top of my lungs—I know that if New York continues, I’ll have another chance. Plano is about three sisters who are in a space-time vortex in Texas—or is it the vortex of family and habit? The dialogue spins ahead by a clever tick in which Arbery has the characters explain, “It’s later,” without missing a beat. It’s a tidy joke on storytelling, on stagecraft, on metafiction, and on the audience: “It’s later. I’m pregnant.” There are fucking belters, and there is a man without a face. The sister who has a string of ailments explains the whole span of contemporary health anxiety: “NO, I’m fine. It’s celiac. It’s endometriosis. It’s fibromyalgia. It’s FULL UTERINE FAILURE.” There is a husband who splits into two—one of whom (spoiler) is smothered with Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle. There is no description of the play I can give to credit its lift. Any number of these devices could have been stickily cerebral, but instead, Arbery’s feeling (the man has seven sisters) and Reynolds’s good judgment brought me to tears of laughter, joined fully by the women behind me. So delighted were we all that we stood talking after the show—together in our admiration. Someday again there will be theaters, big and small, filled with people. Here’s hoping that when the lights come up again, they’re on Will Arbery. —Julia Berick

Performance view of Will Arbery’s Plano, 2018.

Gone

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces in real time the moments before her daughter leaves for college. The column ran every Friday in November, January, and March. It will return again in June.

I’m pulling onto I-35 North. It’s morning, and my daughter, Indie, is in the passenger seat. The sky’s a soft blue, as if every cloud has somewhere else to be. When I put on my blinker and move into the right lane, Indie tells me that I-35 runs from Laredo, Texas, to Duluth, Minnesota, something she learned last year in school. I ask her how far that is, and she taps her phone. 1,568 miles. Today we’re only traveling forty.

Indie and I watch the news at night. We see the empty streets of New York City. We listen to the stories about San Francisco. Texas moves at a slower speed, and the only sign our world is changing is in the empty grocery store shelves. But we feel it coming, especially when Indie worries that all the ceremonies of her senior year will be canceled.

I had a plan, something we could do before we couldn’t do it anymore: get in the car and go far enough to leave everything behind, if only for a little while. Last night I asked Indie if she wanted to get up early and get on the road and cross the Oklahoma border. No stops, no gas stations, just there and back. Her face lit up. We set our alarms.

My daughter grew up on highways, I-70 and I-84 and I-90, chatting or slumbering in the passenger seat as we moved from state to state, nine in all. Every time we crossed a border, I’d honk the horn. This highway, I-35, crosses six states. Today we’re only crossing one.

I don’t like to admit this, but I don’t always know what Indie needs when she’s upset, when she folds into herself or drives the streets of town with no direction or when I hear a catch in her voice over the phone. In those times, I feel useless and sad and lost.

Last week I was running around the lake when I saw a young woman in a clearing off the path. She had a blue backpack, a dark coat, and lavender hair. Indie put pink highlights in her blonde hair a few weeks ago. I love them. She loves them.

If you grow up always going, it’s hard not to want to always be gone.

The sign says twenty-one miles to Gainesville, the last Texas town before the border. Along the way, Indie points to cows in a field, a dilapidated horse ranch, an empty mansion with window frames but no windows. I tell her she can turn on her alt-rock station, but she says what’s playing is fine. The Doobie Brothers, “Minute by Minute.” We sing along.

On my second pass around the lake, I watched the lavender woman move in circles while a wand hovered in midair around her. She guided it with her hands. Magic, I thought, she’s practicing magic.

We’re approaching the city limits of Gainesville. I turn down “Sister Golden Hair” to ask Indie where she would go if she could go anywhere. Boston, she says, because she had a layover there when she traveled to her university’s visitation day last November, and from her plane window, Boston looked beautiful.

A few days ago, the president of the university she will attend in the fall sent an email with these words: “The campus, at the moment, is absolutely still. The shadows remain long at dusk and dawn, east and west.”

Up ahead, we see a large bright sign between the north and south routes of I-35. Oklahoma. I speed up a little. I honk the horn. Indie raises her arms and lets out a long whoop.

In two days, our county will declare a shelter-in-place order. Four days after that, we will be under a stay-at-home order.

But for now we pass grassy fields and wooden fences, an abandoned single-story motel with diamond-shaped windows, and one gas station after another. My daughter and I talk the way we always do on the road, a conversation that hovers between what we dream and what we remember.

On the way back, I think of the woman in the clearing, her magic wand floating. How I wish she could say the word that would turn back time.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

Poets on Couches: Cynthia Cruz

In our new series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“BODY. HISTORY. EVIL. GOD. HUMAN.”

by Lawrence Joseph

Issue no. 229 (Summer 2019)

i.

So it is, the chaos

contracted

in an unfolding scene

in five sentences:

Body. History. Evil. God. Human.

ii.

But what ideas,

in what facts? Inside the sun

the heat is sucking

the soil’s moisture,

a blue-and-red

Diet Pepsi logo is imprinted

on a lobster’s claw,

flashes of lightning, steady rains

complicating the identification

of bodies

charred

to bones,

Town of Paradise a fire zone,

anywhere is everywhere.

And in another intensity the Great

Migrations of Peoples,

ecocidal petro-

capitalist qualitative

destruction,

every cubic meter

of the planet’s air,

inch of its surface,

drop of water,

affected;

and, now,

endless

wars,

and proliferating sorrows.

Cynthia Cruz is the author of six collections of poetry and a collection of essays, Disquieting: Essays on Silence (2019). She is the Kowald Visiting Writer in Poetry for the M.F.A. creative writing program at the City College of New York. Cruz also teaches at Sarah Lawrence College and in the Columbia University graduate writing department.

March 26, 2020

Your Tove

In 1955, after hitting it off at a party in Helsinki, Tove Jansson and the artist Tuulikki Pietilä developed a romance that would last a lifetime. They spent some of the early days of summer 1956 together on the island of Bredskär, where the Jansson family had a summerhouse. The letter below, sent shortly after Pietilä left to teach at an artists’ colony, sees the Moomin creator exploring the dimensions of this new love, recounting the festivities of her uncle Harald’s birthday (“which has traditionally always been a big bash, celebrated at sea”), and drawing “a new little creature that isn’t quite sure if it’s allowed to come in.”

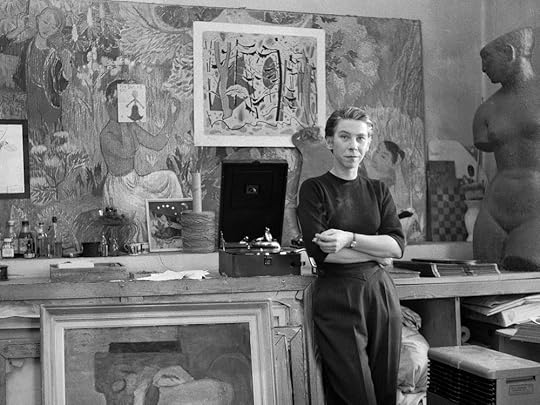

Tove Jansson, 1956. Photo: Reino Loppinen. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

7.10.56 [Bredskär]

Beloved,

Now my adored relations have finally gone to sleep, strewn about in the most unlikely sleeping places, the chatter has died down, the storm too, and I can talk to you.

Thank you for your letter, which felt like a happy hug. Oh yes, my Tuulikki, you have never given me anything but warmth, love, and good cheer.

Isn’t it remarkable, and seriously wonderful, that there’s still not a single shadow between us? And you know what, the best thing of all is that I’m not afraid of the shadows. When they come (as I suppose they must, for all those who care for one another), I think we can maneuver our way through them.

I’m glad you have the advantage of a room to yourself at Korpilahti, so you can just get on with your work and not be disturbed by the cares and intrigues of the colony.

If you write in Finnish, please could you be a dear and use the typewriter; your handwriting’s a bit tricky sometimes. I very much wonder if you could read my last letter at all, Uncle Harald having fallen in the sea with it, along with a consignment of comic strips and a bag of whiskey.

It’s all been intense family living here since they arrived on their sailing boat from Sweden. I ruthlessly go off and draw when I have to, but between times I’m available for household tasks, Bacchanals, child minding, and conversation, whatever turns up. Part of me enjoys it, the other part takes out its frustrations chopping wood. Harald arrived just in time for his birthday, which has traditionally always been a big bash, celebrated at sea.

This year it was magnificently framed by a storm and ended in the traditional joyous whirl of dancing on the rocks, tumbling into pools, and climbing trees. Gentle mother Saga looked after their children for the evening, but in return, all the youngsters from Viken will be coming over to sleep out in tents sometime soon.

The invasions of our beaches are intensifying. Bitti’s in town and will be coming out any time now. After the 20th Uca and Nita. Maybe Kurt. Maybe Maya Vanni. I’m going to try to try to keep my work very separate and leave the cooking to them as much as I can—which is hard, because it’s easier and more natural to do what’s necessary myself.

But I expect it will sort itself out. Presumably there are going to be various strange collisions, but I’m not worried. As regards you and Bitti, it might be much better for you to meet here than in town. The island stays just as beautiful and relaxing, whatever the context in which folk come gadding over the rocks.

One day the whole of Viken came out, Peo as well, bathing was soon in full swing and I had to cook like crazy. It’s good to have the strip cartoons to work on sometimes, I can cope with those however lively my surroundings. I’ve put up the nesting box for the starlings—other than that I’ve been busy with work or socializing. I miss those quiet June days when you were piecing together your mosaic or whittling away at some knotty bit of wood and it was possible to listen, contemplate, and explore how we felt.

On the subject of mosaics, Ham and I gave your “Fishermen” to Harald for his birthday. It was for sale, after all. You said eight, didn’t you?

He was very pleased with it, and it will have a fine place in a home that actually has good taste when it comes to beautiful objects.

Tuulikki, I long to read more in the book of you. I long for you in every way, and I’m more alone with all these people around me than when I was wandering about on my own, thinking of you.

And here is a new little creature that isn’t quite sure if it’s allowed to come in!

Your Tove.

—Translated from the Swedish by Sarah Death

The Finnish writer, artist, and political cartoonist Tove Jansson (1914–2001) is best known for her books about the Moomins, adventurous, amusing cartoon trolls who had much in common with their bohemian, nature-loving author and, it seems, shared many of her family’s traits. She is also the author of eleven novels and short story collections for adults, including The Summer Book and The True Deceiver.

Sarah Death is a prize-winning literary translator, mainly from Swedish, with some forty translated titles to her name.

Excerpt from Letters from Tove, by Tove Jansson, edited by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Letters from Tove © Tove Jansson / Moomin Characters . Selection, introduction, commentaries © Boel Westin and Helen Svensson. English translation © Sarah Death and Sort of Books. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

. Selection, introduction, commentaries © Boel Westin and Helen Svensson. English translation © Sarah Death and Sort of Books. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Poets on Couches: Mark Wunderlich

In our new series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“Our Dust”

by C.D. Wright

Issue no. 109 (Winter 1988)

I am your ancestor. You know next-to-nothing

about me.

There is no reason for you to imagine

the rooms I occupied or my heavy hair.

Not the faint vinegar smell of me. Or

the rubbered damp

of Forrest and I coupling on the landing

en route to our detached day.

You didn’t know my weariness, error, incapacity.

I was the poet

of shadow work and towns with quarter-inch

phone books, of failed

roadside zoos. The poet of yard eggs and

sharpening shops,

jobs at the weapons plant and the Maybelline

factory on the penitentiary road.

A poet of spiderwort and jacks-in-the-pulpit,

hollyhocks against the tool shed.

An unsmiling dark blond.

The one with the trowel in her handbag.

I dug up protected and private things.

That sort, I was.

My graves went undecorated and my churches

abandoned. This wasn’t planned, but practice.

I was the poet of short-tailed cats and yellow line paint.

Of satellite dishes and Peterbilt trucks. Red Man

Chewing Tobacco, Black Cat Fireworks, Triple Hit

Creme Soda. Also of dirt dobbers, nightcrawlers,

martin houses, honey, and whetstones

from the Novaculite Uplift. What remained

of The Uplift.

I had registered dogs 4 sale; rocks, dung,

and straw.

I was a poet of hummingbird hives along with

redheaded stepbrothers.

The poet of good walking shoes—a necessity

in vernacular parts—and push mowers.

The rumor that I was once seen sleeping

in a refrigerator box is false (he was a brother

who hated me).

Nor was I the one lunching at the Governor’s

mansion.

I didn’t work off a grid. Or prime the surface

if I could get off without it. I made

simple music

out of sticks and string. On side B of me,

experimental guitar, night repairs and suppers

such as this.

You could count on me to make a bad situation

worse like putting liquid make-up over

a passion mark.

I never raised your rent. Or anyone else’s by God.

Never said I loved you. The future gave me chills.

I used the medium to say: Arise arise and

come together.

Free your children. Come on everybody. Let’s start

with Baltimore.

Believe me I am not being modest when I

admit my life doesn’t bear repeating. I

agreed to be the poet of one life,

one death alone. I have seen myself

in the black car. I have seen the retreat

of the black car.

Mark Wunderlich is author of three critically acclaimed books of poetry, and his poems, interviews, reviews, and translations have appeared in journals such as Slate, The Paris Review, and Poetry, and in more than thirty anthologies.

Twinning with Eudora Welty

Young Eudora Welty (courtesy The Eudora Welty Foundation)

In The Optimist’s Daughter, Eudora Welty introduces the idea of confluence—of two rivers merging, inexorably, magically, disturbingly. Fate gently takes the reins from Chance. We can rest, we can be held. And the life we thought was singular turns out, reassuringly, to be a strand in a larger pattern.

I became a young woman in the house where Welty spent six months as a young woman. We touched the same walls with our same searching fingers. We grew up shopping at the same grocery store—the Jitney 14—where also, I should mention, a thousand other people shopped; there is nothing sacred about a Jitney. We learned gardens from our mothers, who were always more skilled in dirt than we were; we trailed behind them, gathering blooms, starting our own plots of earth. We left home for college at the age of sixteen, we tried on the North for size. It didn’t fit. I imagine she looked back at the South with that same disturbed wonder that I did—missing it, accusing it, forgiving it. We started publishing in our midtwenties, and we began to migrate: around the world, between jobs, across stories.

You can want to become someone without fully understanding them. Welty was never my favorite author; she was too roundabout. In high school, I got lost in her sentences. Her Southernness felt too artful. Besides, she was notoriously single, one of the many maiden aunts of literature. She found herself in the tradition of women writers who pursued craft at the expense of family—or whose craft was repellent to suitors—or who believed art meant freedom, and freedom meant solitude. To a young girl who still believed in a soulmate-based romanticism, Welty’s aloneness felt damning.

Welty was distant, marble, Katharine Hepburn on a pedestal in The Philadelphia Story, her craft too elegant, her life too celibate. But I grew older. Partners disappointed me; that elegance became a prize. And last year I turned over the soil of Welty’s fiction—carefully tended—and came upon the rich and drifting worminess of her gardening letters.

Tell about Night Flowers, Julia Eichelberger’s selection of Welty’s letters of the forties to two friends—her agent, Diarmuid Russell, and, for lack of a better word, her crush John Robinson—crumbles the marble statue. She is unrepentantly silly; she makes jokes, drinks beer in the morning, gets filthy. She gets into tiffs with neighbors, she has big dreams, she is tired. I had been mapping myself against the facts of her life but never against her character; she was too grand, I was too young. But now, in these letters, we were the same age—early thirties, alone, not wanting to be alone, loving being alone. In December 1941, in the wake of Pearl Harbor, she wrote: “Sometimes I am in despair about people and it feels good to hate them as a kind and to give all your love to a few and to flowers and animals.” How right this sentiment sometimes feels!

My soul fell into hers most readily, like a nesting doll, when she crouched in the dirt and described the heat, the mosquitoes, the loss of dignity, the thrill of a blossom unexpectedly found. “The first flower on the Leila [camellia] opened today,” she wrote John in February 1945. “It is at the back of the bush in the hardest place to see—it means you have to sort of go into the bed on your elbow, full length, and look up.” Gardening for her entailed a purity of purpose; writing, meanwhile, she considered “a secondary thing in my life which gives me intense pleasure (I mean secondary in that it is work—definition)—it is not quite like gardening.” I, too, found my equilibrium in the beds, the only place where words could be entirely banished, and the restless brain could be reduced to a series of mechanical motions: weed, prune, dig, plant, mulch, mow, trim. Some writers took to big-game hunting, others to drink; Welty and I grew flowers.

As I was first reading Tell about Night Flowers last November, I wrote my mother a breathless email:

In five pages, Welty mentions wildflowers growing in Rome; the train from Jackson to New Orleans; writing a novella (“I wish I had a sign to tell me which I had better do that day, write or work the garden”); her inability to prevent her mother from sneakily doing Eudora’s own chores; her mother’s obsession with political news; wanting to write every day (“I jump into it with almost a shout of pleasure—no I don’t quite yell—it just fascinates me and works me”); and a rose that just opened in her garden: MRS. FINCH.

WE ARE THE SAME.

Yes, my own brain was circling around Rome, the Amtrak from Jackson to New Orleans, the tension between wanting to write my novella and wanting to be wrists-deep in the garden, my mother’s kindness, her thirst for news, and the fact that Mrs. R. M. Finch, an antique polyantha rose, was just then blooming in my own bed.

Welty mailed her love of her garden—as carefully packed as a glass vase, as raw as her heart—to John Robinson. She felt easy with this old friend of hers, a writer, a fellow gardener—perhaps because he was a gay man, a fact that she either didn’t know or took pains to not believe. He was stationed in Italy during World War II, where she wrote to him in a voice that’s confused, pleading, flirtatious, a jumble of complicated wants and restraints. (As I read her letters, I too was trying awkwardly to seduce a man via correspondence.) She wrote in November 1944:

It’s been the 18 months—do they just need you too badly. I wish you could get a rest, in Paris or Jackson (I’d enjoy it more here). I don’t know why I thought you were on the way, it was just my interpretation. I wouldn’t take my coat to the cleaners for fear it wouldn’t be back in time. It would be so fine to see you. I thought I might wander to New York and see you light. Write it plain, when you do come—just say Now … I hope you keep warm. I wish you could have this nice day, or rather this moment of it with the sun out and a mockingbird is singing. Mother sends love. Yours, E.

This was what I wanted to say to the man I was yearning for: “Write it plain, when you do come—just say Now.” Sentences even more intimate seemed pulled from my brain—that “all day I was thinking of you”; that “I wish I could see you. The day is so tender here”; that her love was “a daily kind of hope, not ever idle.” She asked him to send a picture of himself, promising to “keep it positively secret, in a drawer, like goldfish that have never seen the light of day.” Ah, that feeling of a world built only for two. “I miss you when I taste something,” she wrote, “like frozen peaches.”

She was in her early thirties, trying to make sense of a love that was unreturnable. I think she was also trying to understand where romantic love fit in the pantheon of emotions. How did it mimic or undercut or amplify her art? I read her words like I was reading my own sadness: “It is so good to hear from you and it changes everything sometimes when things have happened in the world that make a fresh mystery of how you are.” Seeing the heart of another person up close can feel as electric as creating love on the page—no, more so. How could you not want to engage with the reality of what you spent all day inventing? How could you not stumble as you approached its light, its heat?

Love is not a natural companion to art; it may be a competitor. I don’t know how Welty juggled it—what was available to her, what she sought, what she suppressed. If John Robinson had been attracted to women, had returned from the war and dropped to a knee and held out a velvet box, would she have attached her life to his? Would she have had children, written less, become even more of a cheerleader for his career? She sent her New Yorker editor one of John’s stories, which she’d typed and lightly edited; she seemed more comfortable—of course, I think—championing him. But perhaps when I’m in my sixties, I’ll read her letters to the writer Ross Macdonald and learn anew what love is.

Welty was a giver. She was a Southern woman, trained in generosity and sacrifice. I know these things. You can be fiercely independent and still bend to duty. This summer I spent time at an artists’ colony—I went to MacDowell, she to Yaddo—and I was struck by how unusual such indulgence felt. We were both highly privileged women, with means enough to write (mostly) the way we wanted to write, but we also felt keenly the necessity of saying yes to others. In those colonies, there was no yes: there was only the self. We were fed, housed, given tools and time and space, and left alone. I found it radical—she found it “tense.” She was, reportedly, uncomfortable, homesick, and couldn’t work on new stories. Did she ever learn to breathe into that space, to accept it, if never quite to demand it? She worked there on page proofs for her first story collection; I worked on page proofs for my third novel. I picture both of us with our red pencils in the Northern woods, wondering whether home was Mississippi, or home was Art.

If I take her as my model, am I asking for her life: unmarried, childless, alone, creative, someone who gives but also keeps, is kept from some of life’s richness, but also uses her freedom to create more? Or am I telling myself, when I am afraid to be alone, Welty was alone. Which is to say not alone; who among us doesn’t want to have a clubhouse in our backyard where we bring our friends and silly hats and tell ghost stories and dance? A role model is a tool: we use them to push ourselves, to clarify what we want, to console ourselves for falling inevitably short.

Looking for a mirror of ourselves in the world is a primal act of identification. We need assurances that our experiences exist on a spectrum of reality—that we are unique, our character so singular that it must be expressed, but also that we are normal. In this way we are perpetually adolescent. Let me blend in, let no one notice me, but also let me be the only one of my kind. Finding a twin among prodigies is a psychologically easy way to balance both desires at once: I am strange, but in just this extraordinary way. In fact, Welty and I are not alike in voice or talent or accomplishment. We are alike in being women from Jackson, both white, both middle class. Who want both to create and to love, though love is fraught.

But what about the fact that Tell about Night Flowers ends as she embarks, solo, for Lisbon? And that I read those letters when I had just returned, solo, from Lisbon? Some confluences are coincidental and should be discounted.

In Rachel Cusk’s novel Transit, a character finds herself strongly identifying with a famous painter, Marsden Hartley. She eventually comes to a “cataclysm of realisation”: “Rather than mirroring the literal facts of her own life, Marsden Hartley was doing something much bigger and more significant: he was dramatising them.” The mirroring between me and Welty isn’t extraordinary; other people shopped at the Jitney, other people planted roses. It’s the way her life has dramatized mine that’s driven me to write this. Her path is teaching me what my own has meant, or will mean; her story colorizes my own. I read her now—riskily, perhaps—as an oracle.

Last year I took a job at Millsaps College—a few blocks from my house, from her house—where she taught briefly in the sixties. The position was the inaugural Eudora Welty Chair for Southern Literature. The English Department gave me a big sun-filled office in the old English house, where I hung a photograph of Welty looking through a window. I sat in that empty office in the heart of our shared town and looked back at her looking at me. I taught her stories to my students—“Why I Live at the P.O.,” “No Place for You, My Love,” “Where Is the Voice Coming From?”—and tried to keep a neutral expression when they deconstructed her, pointed out her flaws. She is still living, I told myself, imagining her delight—the delight that I would feel if fifty years from now my words were still alive enough to be picked apart.

“The Welty Chair,” people say with raised eyebrows when I tell them of my position, Welty being synonymous with grand, weighty, out-of-reach. But outside my office is a weedy bed, nut grass and Virginia creeper gobbling up the azaleas, and when I sit at my desk grading papers, I feel what I think Welty would feel: not grand at all, but an aching desire to leap up, bolt through the screen door, and start ravaging the clover. “The weeds grow here with a rush practically audible,” she once wrote in despair. I like to think this makes me suited for the job in her name, but really anyone with a loving heart would be suited for it, and don’t most all of us have loving hearts? Not as wide and deep and knowing as hers, perhaps, but loving all the same? Doesn’t each of us want to give, want to be kept, want to make, want to grow?

Perhaps Welty’s magic is not her uniqueness but that anyone could read her and find themselves there. She allows for the illusion of twinness. Maybe this is what art does: it makes you feel that you are suddenly seen. That you have twinned with something in the world. Trying to force a commonality with the artist herself may, in fact, be missing the point of art.

Yesterday I turned thirty-four. The river of my life will take many more bends, some toward the path of Welty’s river, some away. I might have children; I might only have nephews and nieces. But she and I will always be Jackson girls, will thrill at the sight of a spring flower, will cleave to our families, and will find the broader world a bright palette for our fictions. We start—like most writers, or most Southerners, or most people—with wide arms. The mouth of the river. We gather silt, we open outward, we expand to salt. The confluences become too many to count.

Katy Simpson Smith is the author, most recently, of The Everlasting, out this week from HarperCollins

March 25, 2020

Introducing the Winners of the 2020 Whiting Awards

For the sixth consecutive year, in 2020 The Paris Review Daily is pleased to announce the winners of the Whiting Awards. As in previous years, we’re also delighted to share excerpts of work by each of the winners. Here’s the list of the 2020 honorees:

Aria Aber, poetry

Diannely Antigua, poetry

Will Arbery, drama

Jaquira Díaz, nonfiction

Andrea Lawlor, fiction

Ling Ma, fiction

Jake Skeets, poetry

Genevieve Sly Crane, fiction

Jia Tolentino, nonfiction

Genya Turovskaya, poetry

Since 1985, the Whiting Foundation has supported creative writing through the Whiting Awards, which are given annually to ten emerging writers in fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and drama. The awards, of $50,000 each, are based on early accomplishment and the promise of great work to come. Previous recipients include Lydia Davis, Deborah Eisenberg, Jeffrey Eugenides, Tony Kushner, Sigrid Nunez, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Mona Simpson, John Jeremiah Sullivan, and Colson Whitehead. Explore all the winners here.

Congratulations to this year’s honorees. And for more great writing from Whiting Award recipients, check out our collections of work from the 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 winners.

Genya Turovskaya, Poetry

Genya Turovskaya. Photo: Willis Sparks.

Genya Turovskaya was born in Kiev, Ukraine, and grew up in New York City. She is the author of The Breathing Body of This Thought (Black Square, 2019) and the chapbooks Calendar (Ugly Duckling, 2002), The Tides (Octopus, 2007), New Year’s Day (Octopus, 2011), and Dear Jenny (Supermachine, 2011). Her poetry and translations of contemporary Russian poets have appeared in Chicago Review, Conjunctions, A Public Space, and other publications. Her translation of Aleksandr Skidan’s Red Shifting was published by Ugly Duckling in 2008. She is a cotranslator of Elena Fanailova’s Russian Version (UDP, 2009, 2019), which won the University of Rochester’s Three Percent Award for Best Translated Book of Poetry in 2010. She is also a cotranslator of Endarkenment, The Selected Poems of Arkadii Dragomoshchenko (Wesleyan, 2014). She lives in Brooklyn.

*

“Failure to Declare”

I am beside myself

I have no beast in this ring, no horse in this race

Nobody always waves goodbye

The stars are different here

The wind is gusting in reverse

I left something out, something crucial, crossing through the customs gate

A figure, behind me, waving, reflected in the plexiglass partition

I could recognize the shape but not the face

I didn’t need to; I knew it

An empty window

Limp curtain flapping in the breeze

I pitched forward, tried to right myself, but kept falling without end

Keep falling to no end

There was nothing there to catch on, snag against

A tantalizing glitter, a blatant blank

The fortune in the fortune cookie says Learn Chinese

To have a fever

And When one can one must

Where do I live?

Where do I go when I go away?

The departures board was wiped clean

There was no message

But something happens to interrupt all well-laid plans

I was alert to the fog, a fugue of massing clouds, to a change in pressure, coalescing rivulets of rain

A physical vibration, the faintest tremor of the ground beneath my feet, the shifting of tectonic plates

The chafe, the plea in pleasure, for pleasure’s sake

Or was the fortune: When one must one can?

I recognized the empty window, the tantalizing glitter of my own reflection

The shape but not the face

I knew it, that there would be no message, no way to get a message back

I fell I fall I left I leave something out

The ground beneath my feet gives way

Where were we?

Here I am?

Where do I go?

Who is the witness to this story that I tell myself?

Is this rupture?

Rapture?

Attention? Inattention?

The bonds grown slack?

There is an errand I’ve been sent on

An errancy

I am not spared

I am inside the observation tower beside myself astride the horse

I do not have a horse in this

Nobody ever always waves goodbye goodbye

The stars are different here, the stars do not make sense

I can connect these burning dots

There is a hummingbird

There a dancing bear

There a face with night pouring out of the black sockets of its eyes

What are these strange celestial figurations?

Is any crossing safe?

When does the dancing bear claw its way back to nature?

When does a hummingbird become a hurricane?

Which is the miracle and which the natural disaster?

What is at stake?

Jia Tolentino, Nonfiction

Jia Tolentino. Photo: Elena Mudd.

Jia Tolentino is a staff writer at The New Yorker, formerly the deputy editor at Jezebel and a contributing editor at The Hairpin. She grew up in Texas, went to the University of Virginia, and got her M.F.A. in fiction from the University of Michigan. Her book of essays, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion (Random House, 2019), was a New York Times best seller. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The New York Times Magazine, Time, and other publications. She lives in Brooklyn.

*

An excerpt from Trick Mirror:

The call of self-expression turned the village of the internet into a city, which expanded at time-lapse speed, social connections bristling like neurons in every direction. At ten, I was clicking around a web ring to check out other Angelfire sites full of animal GIFs and Smash Mouth trivia. At twelve, I was writing five hundred words a day on a public LiveJournal. At fifteen, I was uploading photos of myself in a miniskirt on Myspace. By twenty-five, my job was to write things that would attract, ideally, a hundred thousand strangers per post. Now I’m thirty, and most of my life is inextricable from the internet, and its mazes of incessant forced connection—this feverish, electric, unlivable hell.

As with the transition between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0, the curdling of the social internet happened slowly and then all at once. The tipping point, I’d guess, was around 2012. People were losing excitement about the internet, starting to articulate a set of new truisms. Facebook had become tedious, trivial, exhausting. Instagram seemed better, but would soon reveal its underlying function as a three-ring circus of happiness and popularity and success. Twitter, for all its discursive promise, was where everyone tweeted complaints at airlines and bitched about articles that had been commissioned to make people bitch. The dream of a better, truer self on the internet was slipping away. Where we had once been free to be ourselves online, we were now chained to ourselves online, and this made us self-conscious. Platforms that promised connection began inducing mass alienation. The freedom promised by the internet started to seem like something whose greatest potential lay in the realm of misuse.

Even as we became increasingly sad and ugly on the internet, the mirage of the better online self continued to glimmer. As a medium, the internet is defined by a built-in performance incentive. In real life, you can walk around living life and be visible to other people. But you can’t just walk around and be visible on the internet—for anyone to see you, you have to act. You have to communicate in order to maintain an internet presence. And, because the internet’s central platforms are built around personal profiles, it can seem—first at a mechanical level, and later on as an encoded instinct—like the main purpose of this communication is to make yourself look good. Online reward mechanisms beg to substitute for offline ones, and then overtake them. This is why everyone tries to look so hot and well-traveled on Instagram; this is why everyone seems so smug and triumphant on Facebook; this is why, on Twitter, making a righteous political statement has come to seem, for many people, like a political good in itself.

Mass media always determines the shape of politics and culture. The Bush era is inextricable from the failures of cable news; the executive overreaches of the Obama years were obscured by the internet’s magnification of personality and performance; Trump’s rise to power is inseparable from the existence of social networks that must continually aggravate their users in order to continue making money. But lately I’ve been wondering how everything got so intimately terrible, and why, exactly, we keep playing along. How did a huge number of people begin spending the bulk of our disappearing free time in an openly torturous environment? How did the internet get so bad, so confining, so inescapably personal, so politically determinative—and why are all those questions asking the same thing?

As we move about the internet, our personal data is tracked, recorded, and resold by a series of corporations—a regime of involuntary technological surveillance, which subconsciously decreases our resistance to the practice of voluntary self-surveillance on social media. If we think about buying something, it follows us around everywhere. We can, and probably do, limit our online activity to websites that further reinforce our own sense of identity, each of us reading things written for people just like us. On social media platforms, everything we see corresponds to our conscious choices and algorithmically guided preferences, and all news and culture and interpersonal interaction are filtered through the home base of the profile. The everyday madness perpetuated by the internet is the madness of this architecture, which positions personal identity as the center of the universe. It’s as if we’ve been placed on a lookout that oversees the entire world and given a pair of binoculars that makes everything look like our own reflection. Through social media, many people have quickly come to view all new information as a sort of direct commentary on who they are.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers