The Paris Review's Blog, page 181

March 4, 2020

Detroit Archives: On Hello

In her column, Detroit Archives, Aisha Sabatini Sloan explores her family history through iconic landmarks in Detroit.

Interior, Detroit public library (photo: Jason Mrachina)

When I went to my parents’ house the other day, in what has become a popular area of Detroit, a group of white twenty-somethings walked by in all beige—capes and boots and leggings—looking like they might have wandered away from a Burberry photoshoot. Less than two miles away, in a part of town with far fewer white faces, my father went to gather the last of his family’s belongings from his childhood home. “Check for Aunt Cora Mae’s photographs,” I asked him. But whoever bought the property after it went into foreclosure had already cleared the upstairs out and put a padlock on the door.

The last time we drove around his old neighborhood, he recited the names of his neighbors, repopulating empty lots with a litany of remembered faces: “A guy named Jeffrey Martin lived here. There was a house about here, that’s where Danny Collins lived. And you cross Forest, that’s where Rodney grew up.” As he spoke, the streets came back to life with the remembered sound of boys screaming with laughter.

Halfway between the house where he lived as a child and the one where he lives now, there’s a street called Goethe. When my father was young, he and everyone he knew pronounced the word phonetically, “Go-thee.” Later in life, he went on to learn German and began to pronounce the street with all the necessary “r” sounds. Whenever we cross it, it is as if we have located the exact intersection that would determine his life’s trajectory. A life filled with detours to places like Los Angeles and Sarajevo, only to return. That street is an inception point, ushering him into a bigger world. The discrepancy between these worlds has taken on a greater significance now that his childhood home sits on a largely vacant block, where squatting families power flat screen TVs with giant extension cords that reach out to whatever house still has electricity.

*

If we’re being accurate, the threshold that more realistically marks where my father stepped into the larger world was the Detroit Public Library, located at 5201 Woodward Avenue. While he attended school at Wayne State University, he worked as the manager of the page pool at the main branch. For as long as I’ve been alive, my father has told me stories about a guy named Kurtz Meyers, who was the head of the library’s music and performing arts department. Kurtz is the guy who suggested that my father perform in the opera Aida when Leontyne Price came to town. Kurtz took him on a trip to the Shakespeare Festival in Ontario. When Johnny Mathis was on tour, Kurtz said, “Why don’t you go over there and say hello?” My dad, who might never have done something like this on his own, walked across the street and knocked on Mathis’s door.

In the Detroit Public Library’s Burton Historical Collection, which I’ve accessed online, there is a photograph from 1967 of Kurtz Meyers looking straight at the camera. He is white, gray haired, and modestly dressed, in a suit with a thin tie, surrounded on either side by four exquisitely dressed African Americans, three of whom are decked out in furs. Two women, gazing down at pictures on the table in front of them, are Eloise Uggams and Eva Jessye, from a touring company of Porgy and Bess.

The photograph was taken by my father, who had recently become curious about photojournalism. He walked his negatives over to Life magazine’s Detroit office, and his career began. They directed him to go to Newsweek, where he would work for the next twenty-five years.

What this archival photograph captures is not just an encounter between a music librarian and a crowd of touring musicians, but the gaze of a mentor to his mentee. The look on Kurtz’s face is specifically for my dad. It is one of such quiet delight. He seems to be saying, “Get a load of this.”

In his life as a photojournalist, my father would interview black artists and actors to collect their life stories before they were forgotten by history. In 1991, he sat in Rome with a man named Al Thomas, who reminisced about touring with Porgy and Bess in Moscow. It is as if, all those years later, my father was still chasing Eva and Eloise.

*

Back in the sixties, my father was near the entrance to the library when he picked up the phone at the guard’s desk and called the loan bureau desk. He wanted to talk to the cute Italian girl who manned the phones. He asked her out. She was my mother.

One recent winter day, I ask my parents to take me on a tour of the library where they first met. I’m surprised by how extraordinary the space is. Designed by Cass Gilbert and opened in 1921, the building was constructed in the Italian Renaissance style. At the Woodward Avenue entrance, you pass through bronze doors, and you’re greeted by a mosaic by Frank Vega depicting Copernicus. Above the grand staircase, ceilings designed by Frederick Wiley show figures from Aesop’s fables. The arched, painted windows in Strohm Hall stand almost three times the height of a human being, letting in light through depictions of the zodiac.

My parents reminisce about what other couples met for the first time at which elevator: their friend the Jamaican choreographer who went on to world renown, the lady who dated the Motown artist I’m not allowed to mention here, their friend Mary, who passed out tampons and repaired the flag every day until it began to shrink. They’ve made such a mythology out of this place, this cast of characters. In person it’s at once larger and smaller than I imagined. They seem at a loss as to how to beckon it all back on cue. My dad points to a cart and says, “When he was a page, your uncle used to curl up on one of those things and read.” It is a point of pride for my father, who respects my mother’s brother deeply, that he was once my uncle’s boss.

When I ask my uncle what he remembers of the library, he recalls glass floors. “Light came from the floor up. It was not clear, it was frosted, foggy.” He would turn off the lights and walk around with just the floor lights on, spooky, glowing underneath him. There were floors and floors of stacks unseen to the patrons. “But the rooms are so tall,” I say, thinking of the majestic space where a mural of a man’s upturned face and neck spans three arched sections, majestic as the Sistine Chapel, a triptych called Man’s Mobility by John S. Coppin. My uncle remembers a maze-like place full of wonder behind and below, floors stacked in a way that brings to mind Borges’s “The Library of Babel.”

As we walk past an enclosed area, the E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts, I notice a flyer for an upcoming lecture on Lionel Richie. I’m a child of the eighties, and the sight of Richie’s album covers, especially Can’t Slow Down—white room, white pants, small fro, backward chair—transports me right back to the gray carpeted living room where I choreographed dance routines as a kid.

*

On the night of the lecture, I return to the library with my parents. The music librarian, Romie Minor, reads from a binder full of laminated pages. He tells us that when Lionel Riche was a child, his grandmother played Bach and Mozart for him. Later, he studied to be a priest. But, “he was not priest material.” A man in the back of the room laughs.

There are folding chairs for around thirty. Eight of us are here.

Romie Minor says, “Let me play this one for you.” He puts a CD in a boom box situated on a desk at the front of the room. As the music plays, a woman in a yellow pantsuit says, “There it is.”

When we walked into this book-lined room, Minor was prepping. At the top of the hour, he picked up a microphone and began to sing “Oh No,” by the Commodores. “I’m going crazy in love” he spoke-sang, then leaned over to the woman in the yellow pant suit, who cooed back: “over you.”

My dad picked up his camera. We were in the same room where he snapped that picture from the archives fifty-three years ago.

Over the course of the evening, Minor described the highs and lows of Richie’s career. A slideshow with album covers played on a television standing on a rolling cart.

The audience thrummed:

“That’s a jam”

“This music represents about two-thirds of my kids. That’s how they got here.”

“Lord have mercy.”

“Can’t remember my address but I remember that.”

When “Easy like Sunday Morning” came on, almost all of us sang. The curator’s manner was quiet but totally hooked in. He held court with the audience without raising his voice, or really even modulating his tone. This contrasted beautifully with his body language, which was similarly contained, but with flourishes. When a new song came on, he threw his hands out like he was splashing water. In a monotone, he punctuated the gesture: “Crossover hit.”

A library security guard, who’d wandered into the lecture on his break, closed his eyes. He said, “I spent a lot of time on the dance floor to that one.”

Minor started to talk about the tension within the Commodores when Richie began to get famous. The library audience was definitively team Lionel. They responded to each fragment of Commodores versus Richie gossip with an elongated, “Mmhmm.”

When “Endless Love” played, and Diana Ross sang “bum bum bum” with Lionel Richie, a member of the audience in a beret impersonated an electric guitar.

“I don’t know what he was doing out on the road,” the curator said.

“Yes, you do,” somebody responded, insinuating something salacious.

I got emotional when the curator put on “Night Shift.” It was the Commodore’s first hit without Lionel. It is one of my favorite songs of all time, and I’m not alone. In an interview for the radio program On Being, Claudia Rankine talks about the time she sang “Night Shift” from start to finish with a stranger on a plane. At one point, my mother calmed my father as he panicked about his blood sugar, and I blurred my eyes, wondering what their young selves would have thought about this glimpse into their future.

As we listened to “Hello,” Minor told us an anecdote about the song’s famously melodramatic music video. Apparently, Richie disliked the bust that the fictional blind student sculpts of his likeness. He claimed it looked nothing like him. “But she was blind,” the director explained. My dad stage whispered: “So she was sculpting his voice.”

I told my mother that our parking meter was about to expire. My dad raised his hand and explained that we shouldn’t be surprised that America’s greatest export is our culture. He told the story of being in Berlin as the wall came down. How the East Germans sang black American music, and called out to him in solidarity. “Anyway, we’ve gotta go,” he said. The talk was far from over. I apologized a bit too profusely, cheeks burning, as we all got up to leave.

On the way out, I saw the security guard, who had since returned to his shift near the exit. “Do you go to these talks often?” I asked. “Oh yeah,” he said.

My mother had recently told me about the time when she was in the library basement on a break, and a security guard, a man she liked very much, came down to eat his lunch. He put his plates away, stabbed himself, and later died. “It was awful,” she’d said.

That night, I thought of the security guard we’d met, working the remaining hours of his night shift. Ordinary life continues on in this city despite all its extremity—water shut offs and casino lights, Burberry-draped hipsters and foreclosed homes. And amid all that, there’s a small room of people chuckling quietly at the main branch of the public library while listening to albums on a cold winter night.

As we left the building, we passed the reception desk. My parents restaged their first conversation:

“I was here.”

“No, you were over there.”

“And I called.”

“Yeah, I picked up the phone, and I said, ‘Who is this?’ And you were standing right over there.”

Aisha Sabatini Sloan is the author of the essay collections The Fluency of Light and Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit. She is the Helen Zell Visiting Professor of Creative Nonfiction at the University of Michigan Writers’ Program.

March 3, 2020

Oh, Do Tone It Down, Ladies

Auguste Toulmouche, The Reluctant Bride, 1866. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Docile quietude has long been wielded by conduct books as a specifically feminine virtue. In 1946, the magazine Photoplay published the article “That Romantic Look,” an instructional piece for women who were aiding their soldier husbands in acclimating to civilian life after World War II. The paramount goal was to minister to one’s head of household without injuring his proud masculinity:

Listen to your laughter too. Let it come easily, especially when you’re with boys who had little to laugh at for too long. Laugh at the silly things you used to do together. Laugh for the sweet sake of laughter. And if you hear your laugh sound hysterical, giddy, or loud, tone it down, oh do tone it down!

Easy enough to say, “Speak gently. Laugh softly,” I know. The tone of our voice and laughter generates within us. When we’re worried or rushed, it’s in our voice and laughter that hysteria will manifest itself … Serenity is the very wellspring of a romantic look. In it you have the beginning of the smooth brow, the easy carriage, the low voice, the gentle smile. This Christmas with our men home, surely we should know serenity. So let us look happy and contented and starry-eyed.

Historical context aside, these directives might have come from a Victorian lady’s etiquette book. Midcentury America draws liberally upon the rhetoric of hysteria in admonishing its women to cultivate placid demeanors and soft, dulcet tones. And yet, with a more modern and progressive approach, this conversation—how to aid someone in the transition from a violent, traumatic context to the routines of daily life—would be a productive one. It would not be until the Vietnam War that we began even to discuss how to engage with those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder: these early efforts to soothe those who had recently endured the unthinkable are well intentioned but, unsurprisingly, entrenched in gender-normative philosophies regarding femininity and distribution of emotional labor. Oh, do tone it down, ladies.

As for nineteenth-century etiquette books, their positions on women’s voices and general dispositions are what you might suppose: if, as the old chestnut goes, children were to be seen and not heard, women’s guidelines hardly differed. Feminine exuberance would have been received as unseemly at best when so much as opening one’s mouth demanded special care and modulation. As in all other topics, Ella Adelia Fletcher’s The Woman Beautiful takes a maniacally specific approach to addressing how a woman should speak without afflicting the genteel ears of those present. After instructing her readers in how to beautify their mouths and lips, Fletcher proceeds to tackle voice:

Naturally, the beautiful mouth and coral lips should be fittingly completed by a lovely voice; but, too often, this harmonious trinity is violated by a discordant, rasping, badly-placed voice. It is usually the result, not of any physical defect, but of careless habits: careless habits of breathing, of thinking, and of speaking. The commonest defect in a woman’s voice is pitching it too high; and often this is accompanied by a nervous tension which holds the muscles of the throat taut and strained; and by short, hurried breathing which cuts the vibrations, destroys the overtones, and imparts an unpleasant rasping, dead, or shrill timbre to the voice.

Based on her account, it seems that Fletcher keeps close company with a hoard of verbal zombies, such is the purported ghastliness of women’s faulty speaking habits. It’s unclear how Fletcher has arrived at her conclusions regarding the ways that one might butcher her tone of voice—her description doesn’t strike me as especially scientific—but her paramount motivation is not educating her readers on the mechanics of vocal cords and breath. Rather, the primary object is to render women more hesitant before they speak, less eager to pipe up in conversation, and more inclined to focus their efforts on adopting speech patterns that, while likely difficult to maintain, ensure that Victorian women uphold their foremost public role: emollient decoration. As Fletcher has made eminently clear, there is no aspect of one’s person that cannot be chiseled and squeezed and pressed upon until it obliges masculine sensibilities of female beauty and, above all, does not agitate a man’s amour propre. A woman should arrange herself so that she serves as a complement to bolder, brasher masculinity:

Train your ear to notice pleasant, agreeable voices, and listen to your own critically. In the seclusion of your own room, try the pitch of your voice until you discover its most melodious one, that upon which you can develop the fullest and sweetest timbre, —the tone which you determine shall be known by your friends as your voice.

It’s a wonder that anyone could proffer an argument for essentialist gender types, when literature like this makes no bones that femininity arises from an assemblage of learned behaviors and traits. Although Fletcher does not directly address relations with men, the issue looms large on every page, with the implicit argument that if one liturgically adheres to her lessons, she will be the sort of woman who is pleasing to men and will therefore attract their attention, as opposed to her imagined “rasping, dead”-voiced competition.

While Fletcher was dispensing her advice across the pond, Mrs. C. E. “Madge” Humphry, one of the first female journalists in Great Britain, was also publishing etiquette manuals for men and women alike. In 1898, she released A Word to Women, which followed her popular 1897 volume Manners for Women. Her advice, rooted snugly in fin-de-siècle gender politics, acknowledges women’s increased, but tenuous, presence in the public sphere while adhering to the enduring philosophy of the “Angel in the House”—in other words, the Victorian argument that a woman’s rightful place was the domestic sphere, which she should cultivate as a place of pacific harmony, a palliative contrast to the rough-and-tumble of male-dominated public life.

Humphry reiterates the necessity of maintaining tranquility in the home, but moreover directs women to wield this influence in whatever social context they may inhabit. In her chapter titled “Golden Silence” she posits that a woman should limit her chatter without becoming tedious company:

The lesson of quiet composure has to be learned soon or late, and it is generally soon in the higher classes of society. In fact the quality of reticence, and even stoicism, is so early implanted in the daughters of the cultivated classes that a rather trying monotony is sometimes the result. After a while the girls outgrow it, learning how to exercise the acquired habit of self-control without losing the charm of individuality. When maturity is reached, one of the most useful and delightful of social qualities is sometimes attained—not always—that of silently passing over much that, if noticed, would make for discord. Truth to tell, there is often far too much talking going on.

Humphry’s lessons are evidently aimed at “the cultivated classes” in English society, not surprising in such a trenchantly hierarchical arrangement. And as she vigorously indicates, one mark of good breeding is striking the balance between boring one’s company and not allowing the “charm of individuality” to unravel into dreaded loquaciousness. A woman, she insinuates, ought to be a peacemaker; that is to say, she should not address comments that are upsetting or inappropriate; after all, this would introduce “discord” into the atmosphere. Instead, one must suppress one’s more ardent impulses to ensure smoother discourse. Being oneself was welcomed so long as that self was stringently groomed with the paramount goal of appealing to everybody and offending no one.

For, as Humphry elucidates in a later chapter, “Lightheartedness,” it is not sufficient for a woman to monitor the quality and effect of her conversation; she must perform these feats with a smile. Unsurprisingly, the infuriating habit perpetuated by so many men—“Give me a smile, baby”—has firm roots in Victorian expectations of women to ameliorate every social environment, to transform their surroundings into pleasant, cheery contexts through the performance of good humor:

Men are always telling women that it is the duty of the less-burdened sex to meet their lords and masters with cheerful faces; and if any doubt were felt as to the value of the acquirement—for cheerfulness often has to be acquired and cultivated like any other marketable accomplishment—shall we not find a mass of evidence in the advertisement columns of the daily papers? Do not all the lady-housekeepers and companions describe themselves as “cheerful”? Lone, lorn women could scarcely be successes in either capacity, and cheerfulness is a distinct qualification for either post.

Humphry’s chain of rhetorical questions is telling. For a late Victorian woman, what men desire—to be greeted as kings of their castles by beaming, beatific faces—demands attention and supplication (for sanity’s sake, we’ll pass over the suggestion that women are “the less-burdened sex”). “Well, ’tis our duty to be cheerful,” Humphry concludes, soon after these remarks. For that matter, she treats her commentary regarding the necessity of “cheerfulness” in service positions as something of an afterthought; the greatest sign of “the value of the acquirement” lies in male pleasure. But in mentioning the necessity of a sunny disposition in “lady-housekeepers and companions,” two positions in which a woman joins a household as an inferior member, Humphry lays bare a larger truth: that all women must be at the service of their so-called male betters, and that they must quash their own uglier sentiments so that they may ensure they do not detract from the social atmosphere. Humphry is not so naive to overlook the “marketability” of this quality: by drawing a comparison between good breeding and business transactions, she insinuates that women are always, to some extent, selling themselves as welcome members of polite company. But in this case, that which is “marketable” happens to be inextricable from ironbound duty.

And yet Humphry resists the perspective that a woman’s purpose is exclusively to serve as a decorative vessel. Overlooking the extent to which women’s education has been obstructed and regarded as unnecessary, she censures her readers in a chapter aptly named “Deadly Dulness” (sic) for failing to elevate their minds beyond more trivial pursuits. “Ninety out of every hundred women bury their minds alive,” she declares. “They do not live, they merely exist.” But the fault, she maintains, rests with women, for being inclined to indulge in less intellectual activities, for occupying themselves with fashionable trends rather than, say, reading the newspaper:

The great world and its doings go on unheeded by us, in our absorption in matters infinitesimally small. We fish for minnows and neglect our coral reefs … And yet the news of the universe, the latest discoveries in science, the newest tales of searchings among the stars, to say nothing of the doings of our own fellow creatures in the life of every day, should be of interest. But we think more of the party over the way, and the wedding round the corner. Is it not true, oh sisters?

On the one hand, it’s not undesirable for a Victorian woman with some influence to encourage reading and self-education. But clearly she’s referring to her “sisters” in equal or loftier socioeconomic classes: Humphry, like so many other Victorians, evinces little interest in empowering women of the working class. What’s more, women were often condemned for acclimating to their prisons: while certainly intellectual curiosity varied—not every Victorian woman was a Brontë sister or George Eliot—it was a vastly uphill battle for women to procure the sort of education so readily available to men of a certain economic or social stature.

It was also not uncommon for intellectual women to accuse others among their ranks of silliness. In 1856, George Eliot penned the scathing essay “Silly Novels By Lady Novelists,” wherein she derides—with gusto—the sort of literature written by her female contemporaries, arguing that it is frivolous, detached from reality, and altogether an indication of what the novel should not be. Jane Austen delighted in the ridiculous social manners of men and women, although her critiques of women, in light of their often circumscribed opportunities, sometimes blistered with especial cruelty. And in this case, Mrs. Humphry castigates women of means for frittering away their days with dresses, parties, and wouldn’t you know—fiddling novels. Women, it seems, were enthusiastic about the wrong things precisely because they were coded as undeniably feminine. To edify oneself, according to Humphry, requires one to consider more sober goings-on. Not a deleterious endeavor on its own, but its purpose here is to teach women to behave so that they will be taken seriously by men, or shall we say, as serious as ever a man might have taken a woman in 1898 British high society.

Perhaps, buried within the coils of internalized sexism, is Humphry’s genuine desire for women to navigate a world that regards them as subordinate and foolish. Three decades prior, the American etiquette writer Florence Hartley undertook a different task, one that resembles Ella Adelia Fletcher’s scrupulous methodology of behavioral micromanagement. In The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness (1860), Hartley reminds women readers through every possible avenue that their primary object in all things is “true politeness.” And in the chapter “Polite Deportment, and Good Habits,” she delineates how politeness should manifest in a woman’s every gesture, admonishing especially against exuberance and volume:

Many ladies, moving, too, in good society, will affect a forward, bold manner, very disagreeable to persons of sense. They will tell of their wondrous feats, when engaged in pursuits only suited for men; they will converse in a loud, boisterous tone; laugh loudly; sing comic songs, or dashing bravuras in a style only fit for the stage or a gentleman’s after-dinner party … It may be encouraged, admired, in their presence, by gentlemen, and imitated by younger ladies, but, be sure, it is looked upon with contempt, and disapproval by every one of good sense, and that to persons of real refinement it is absolutely disgusting.

Hartley’s rhetorical maneuvers in this passage lean heavily on emotional manipulation. You may believe that others enjoy your company, that you are a social success, but everyone who matters, everyone whose approval you should crave, finds you “absolutely disgusting.” For, as she insinuates, this “loud, boisterous” behavior only suits women of questionable virtue, the so-called fallen women who often made their livings catering to rich men in after-hours. What we now refer to as slut-shaming Hartley deploys as a tactic of dissuasion: it’s best to pipe down or else everyone will think you loose and skanky.

But rather than merely dispense this warning against unwomanly conduct, Hartley offers guidelines that demand the most punishing regimens of self-monitoring. It is not enough to keep one’s voice soft; every muscle must be trained to enact genial docility:

Never gesticulate when conversing; it looks theatrical, and is ill-bred; so are all contortions of the features, shrugging of shoulders, raising of the eyebrows, or hands.

When you open a conversation, do so with a slight bow and smile, but be careful not to simper, and not to smile too often, if the conversation becomes serious.

Never point. It is excessively ill-bred.

Avoid exclamations; they are in excessively bad taste, and are apt to be vulgar words. A lady may express as much polite surprise or concern by a few simple, earnest words, or in her manner, as she can by exclaiming “Good gracious!” “Mercy!” or “Dear me!”

…

Avoid a muttering, mouthing, stuttering, droning, guttural, nasal, or lisping, pronunciation.

The list continues in a similarly—and obsessively—fastidious manner. At base, Hartley, Humphry, and Fletcher share a common assumption: women should not gab so much that these exacting rules for discourse are difficult to follow. Being “cheerful” as Humphry directs is by no means a state to be confused with an easy, relaxed attitude; although, if one practices the appearance of it enough, perhaps verisimilitude will suffice. Nineteenth-century women generally understood the constrictions of their milieu: they would not be regarded as men’s equals no matter their accomplishments or character. Women of privilege, those born to families with wealth and status, knew that, at best, they could distinguish themselves as examples of genteel femininity. But to achieve this distinction demanded an unyielding suppression of too muchness—of brash opinions and political fervor and heated emotions. After all, Victorian literary heroines like Middlemarch’s Dorothea Brooke were beloved for their gentle, not dispassionate, but certainly refined demeanors. Maggie Tulliver, from The Mill on the Floss, and the most famous of chatterboxes, Anne Shirley, learn to lower their voices and quench their confabulation as they grow older. Most of Victorian literature’s notoriously headstrong heroines, like Elizabeth Gaskell’s Margaret Hale or Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley Keeldar, could hardly be described as bombastic, though Shirley Keeldar, who is proud and difficult and sometimes deliciously rude, perhaps comes closest. To seize the tatters of respect and tolerance has always meant whittling ourselves into shapes that are legible and, above all, the easiest to swallow. And indeed: we’ve been swallowed whole, consumed for centuries in our most palatable, pleasing forms. To live authentically, and thereby refuse this protracted social annihilation—that’s the aim.

Rachel Vorona Cote publishes frequently in such outlets as The New Republic, Longreads, Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, Literary Hub, Catapult, the Poetry Foundation, Hazlitt, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, where her essay on Taylor Swift and Victorian female friendship was one of the site’s most popular essays in 2015. She was also previously a contributing writer at Jezebel. Rachel holds a B.A. from the College of William and Mary and was A.B.D. in a doctoral program in English at the University of Maryland, studying and teaching the literature of the Victorian period. She and her husband live in Takoma Park, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Excerpted from Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today . Copyright © 2020 by Rachel Vorona Cote. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Redux: Monologue for an Onion

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

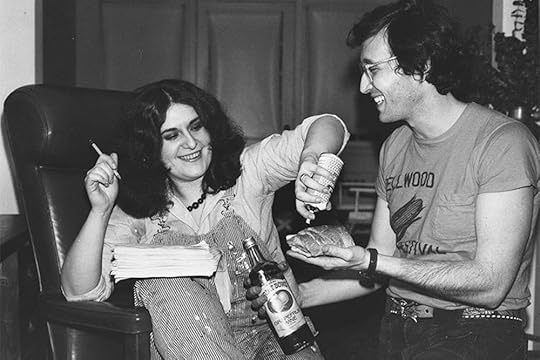

Jane and Michael Stern at home in Connecticut in 1975, with the manuscript of the first edition of Roadfood.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re weeping over the alliums in our archive. Read on for Jane and Michael Stern’s Art of Nonfiction interview, Aleksandar Hemon’s short story “Fatherland,” and Sue Kwock Kim’s poem “Monologue for an Onion.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And don’t forget to listen to Season 2 of The Paris Review Podcast!

Jane and Michael Stern, The Art of Nonfiction No. 8

Issue no. 215 (Winter 2015)

We were eating in all these road-food places, which didn’t have a name then. There wasn’t the concept of “road food”—there were just these little mom-and-pop cafés, and we kept a little notebook of these places.

Fatherland

By Aleksandar Hemon

Issue no. 162 (Summer 2002)

The train was much too salty: the Soviet masses everywhere, wearing the expression of routine despair: women with bulky bundles huddled on the floor; stertorous men prostrate up on the luggage racks; the sweat, the yeast, the ubiquitous onionness; the fading maps of the Soviet lands on the walls; the discolored photos of distant lakes; the clattering and clanking and cranking; the complete, absolute absence of the very possibility of comfort. I survived only because I followed Jozef, who cheerfully moved through the crowd, the sea of bodies splitting open before him. We found some standing space in the compartment populated solely by our schoolmates.

Monologue for an Onion

By Sue Kwock Kim

Issue no. 148 (Fall 1998)

I do not mean to make you cry.

I mean nothing, but this has not stopped you

From peeling away my flesh, layer by layer.

The tears clouding your eyes as the table fills

With husks, ripped veils, all the debris of pursuit.

Poor deluded human: you seek my heart …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

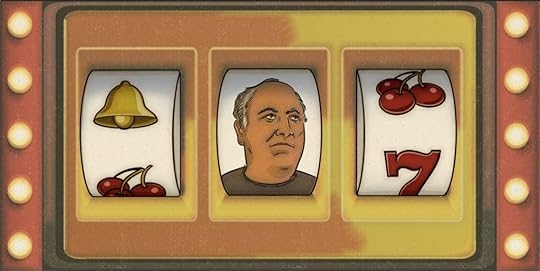

The Pioneer of Online Gambling

Michael LaPointe’s monthly column, Dice Roll, focuses on the art of the gamble, one famous gambler at a time.

Original Illustration © Ellis Rosen

In April 1995, traders on the floor of the Pacific Exchange were in a frenzy. The jury in the O. J. Simpson trial had refused to come to court that morning. In the Washington Post, a law professor said that the probability of a hung jury had increased. And so at the exchange, if traders had shares in guilty or not-guilty verdicts, they wanted to dump them; a hung-jury share was looking a lot sharper today. Everyone was looking for Steve.

This had nothing to do with the stocks on the ticker, and everything to do with an elaborate, parallel marketplace operated by Steve Schillinger, an independent broker, who sold futures on the side for countless things you couldn’t find at the exchange: Who would win baseball’s MVP award? Who would make the Final Four? Would O. J. go to prison? Although Schillinger was a decent enough stockbroker, his real talent was in figuring the odds for nebulous outcomes like that of the O. J. verdict and revising them as events unfolded. His colleagues placed bets with him, and he’d pay out on the basis of whatever the odds had been at the time of the wager. He was, in short, a bookie.

“People were leaving their stocks to come bet on the NCAA,” Schillinger said, explaining why he was quietly asked to leave the exchange. But by then, he had a dream. In his covert marketplace, he’d glimpsed not just his own future, but the future of gambling. That vision would lead him to become the pioneer of a multibillion-dollar industry, and then a fugitive from justice who would die in exile.

*

Originally from Chicago, Schillinger came to San Francisco in 1979. He was preternaturally gifted at perceiving probabilities. Golf, backgammon, chess—he could set odds on anything, and place a savvy bet. I recently spoke to a former colleague of his, who said that the day Princess Diana died, Schillinger bet that Elton John would write a song about her. “That was a long shot,” the colleague told me, “but Steve won it at twenty to one.”

In the mid-’90s, Schillinger and two friends from the exchange, Jay Cohen and Haden Ware, decided to start an online sports book. On the surface, the start-up conformed to the logic of many early dot-com endeavors: take a well-established practice and put it online. But in fact, what Schillinger, Cohen, and Ware were developing was far more radical. They wouldn’t just book conventional bets. In keeping with Schillinger’s O. J. experiment, in which the odds fluctuated as the trial progressed, the start-up would offer “sports futures.” You could buy stock in eventual outcomes—who would win the AFC Central division in football or who would appear in the NBA finals—and the value of those shares would rise or fall in real time, depending on the breaks of a season. Even the bets on individual games would follow a futures model, with probabilities fluctuating as the outcome came into focus. “The future of sports gambling is totally interactive wagering during the game,” Cohen declared.

This innovative futures market gave the start-up its name: the World Sports Exchange. They raised $600,000 and registered an alluring website: www.wsex.com.

It was time to book some bets—but where? Unless you were a Nevada casino, it was illegal to be a bookie in America. Of course that didn’t stop it from happening. In 1998, it was estimated that Americans illegally wagered about $100 billion. But WSEX was proposing to do its business proudly out in the open, not in the smoke of some dingy backroom bar.

And so they set out for Antigua and Barbuda. In the aftermath of devastating hurricanes, the island nation’s tourism industry was in decline, and it was pivoting to online gambling. With underwater fiberoptic cables connecting it to the U.S., Antigua was ideally positioned to capitalize on this burgeoning business. By 1999, the online gambling industry would be the island’s second-largest employer, and the nation of 65,000 would account for over half of the world’s remote gambling market.

Above a camera shop in a Saint John’s strip mall, Schillinger, Cohen, and Ware set up an office and launched WSEX in November 1996. At first, they had about twenty customers. Then came the golf tournaments. With dozens of players competing over several days, golf was perfect for showcasing WSEX’s futures market. News of the start-up spread by word of mouth, and business started flourishing. In 1997, the client list grew to five hundred. In 1998, it blossomed to two thousand, and it was six thousand the year after that. By 2000, as they were booking bets on the outcome of Bush v. Gore, or who would get booted off Big Brother, the annual income of WSEX was reportedly more than $300 million.

*

As far as its founders were concerned, WSEX was doing nothing illegal. They were fully licensed by Antigua. Certainly they were doing nothing immoral—at least nothing worse than what they’d done at the Pacific Exchange.

Drawing comparison to the stock market was the WSEX company line. “You can’t tell me that when someone buys a stock on Monday and sells it on Tuesday that that’s investing,” Jay Cohen told Sports Illustrated. “That’s gambling, just like our [sports] futures market. Internet gambling is the same as my last career, except the folks I work with now are less sleazy.” Haden Ware added, “If you go on our site and change Boston Red Sox to Boston Market, we’re Ameritrade just like that.”

They weren’t wrong to draw such parallels. As David G. Schwartz writes in Roll the Bones, his history of gambling, the pioneers of finance capitalism saw speculation as a kind of gambling. A coffeehouse near the royal exchange in London was described as “being full of gamesters, with the same sharp intent looks”; but as Schwartz writes, “these gamesters had turned in their cards and dice for stock.” The stock exchange inherently attracted gamblers. In The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), John Maynard Keynes states that “the game of professional investment is intolerably boring and overexacting to anyone who is entirely exempt from the gambling instinct.”

But the law wasn’t amused by these comparisons. As WSEX flourished, Schillinger and his colleagues made powerful enemies. Back in the U.S., Senator Jon Kyl of Arizona was crusading against online gambling. Likening the practice to crack cocaine, Kyl said that sites like WSEX were “where little Johnny can basically bet away mom’s entire credit card before she gets home from work.” In time, the senator refined this message into a kind of fearmongering jingle: “Click the mouse and bet the house.” He introduced the Gambling Prohibition Act of 1997, under which an online bookie would face a four-year prison term. Kyl tried out another, less melodious slogan: “Use email and go to jail.”

WSEX tried to make light of the opposition. They even set odds on whether the Kyl bill would pass. It did not, but in March 1998, Schillinger, Cohen, and Ware were nevertheless charged in federal court with violating the Wire Act.

Introduced in 1961, the Interstate Wire Act was intended to cut off the lifeline of bookies, making it illegal to use telephone wires for booking bets. WSEX argued that the act didn’t apply to them. Not only was the law obsolete, having been written decades before the internet, but that also just wasn’t how they did business. WSEX customers wired money, sure, but that wasn’t a bet. The money remained banked until they made a wager, and those wagers didn’t occur over phone lines; they occurred in the internet server housed in Antigua, where everything was legal.

I recently spoke with Haden Ware, and he described the mood of cautious optimism the three men felt when Jay Cohen returned to the U.S. to fight the charges. “We felt that it was a bluff,” Ware told me, “and that if we called it, they’d go away fairly quickly.” Cohen urged his colleagues to keep WSEX plugged in, estimating he’d be back in six months.

It would be eight years. On July 24, 2000, Cohen was found guilty. He served eighteen months at Nellis Federal Prison Camp, north of Las Vegas, and was sentenced to a lengthy parole that kept him away from Antigua.

WSEX continued its operations, but for Schillinger and Ware, the writing was on the wall: returning home would mean prosecution and imprisonment. They were exiles.

*

When Morley Safer disembarked in Antigua to interview Schillinger and Ware for 60 Minutes, he was turned back by customs. The island wasn’t sure what kind of slant he’d give the story, and they didn’t want any bad publicity. The WSEX team went to meet him on the nearby island of Saint Martin. The story, which aired in January 2001, showed the men happily golfing. Safer enviously observed that Schillinger never wore a tie to work—or “We’re real happy down here,” Schillinger said. “If you’re going to be trapped somewhere, it’s not a bad place to be trapped.”

The reality of exile was slightly different. Schillinger had brought his wife and children with him when he first moved to Antigua. He’d thought it would be a temporary adventure before WSEX became legitimate and they returned home. But by 2000, the family was back in California. Antigua was “not a great place to raise young ones,” he said. “There’s nothing here for them to do.” The family tried meeting on various Caribbean islands about once a month. Then his wife filed for divorce.

Around the same time, Schillinger called to wish his father a happy seventy-sixth birthday, and his mother informed him that he’d died five days before. She’d refrained from telling him, in case he impulsively risked arrest by coming home for the funeral. “I knew something like that would happen one day,” Schillinger told the New York Daily News. “It was horrible.”

But he vowed to keep going. “There’s really no slowing us down,” he said. “There’s no stopping us.” By 2003, WSEX was planning to strike back.

*

While serving his sentence, Jay Cohen received fan mail. People had seen the WSEX founders on 60 Minutes and were impressed by how they’d stood up to figures like Senator Kyl. One such letter contained two ideas. The first was for a betting service that would track pregnancy due dates. Cohen discounted that one. But the second idea was intriguing. What if Antigua sued the U.S. government for violating trade rules?

After all, the letter writer argued, the U.S. allowed some long-distance wagering, such as offtrack horse-race betting. By outlawing WSEX but still allowing offtrack betting, the government was giving preferential treatment to U.S. companies. That violated World Trade Organization rules.

In 2003, the WSEX lawyer filed a complaint with the WTO on behalf of the Antiguan government. The U.S. responded by claiming their laws were designed to protect public morals. But in a repudiation of Senator Kyl’s rhetoric, the WTO ruled that the U.S. had failed to demonstrate a moral basis for their laws. Instead, targeting the Antiguan gaming industry was clearly an attempt to protect economic interests. The U.S. was ordered to pay damages.

“The U.S. doesn’t control Antigua and it doesn’t control the internet,” Schillinger declared. But above the camera shop in Saint. John’s, things were starting to unravel.

By then, Ware told me, “We were a law firm fronting as a sports book.” Much of the company’s revenue had gone into fighting the Cohen and WTO cases, and whatever remained went back into the site. Meanwhile other, fiercely competitive sports books had emerged online, and the comparatively low-tech WSEX struggled to keep pace. What’s worse, after licking its wounds from the WTO decision, the U.S. government circled back on Antigua.

On October 13, 2006, President George W. Bush signed the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act. Full of typos and tacked onto an unrelated homeland security bill, the act prohibited banks, credit card companies, and eWallet services from transferring funds between U.S. residents and offshore gambling businesses. It was spearheaded by none other than Senator Kyl.

Now WSEX had its money seized by banks, and credit card companies wouldn’t process payments. Soon, complaints started circulating that WSEX wasn’t paying its customers on time. In 2010, the sports book had its Antiguan gaming license revoked. In 2013, the site went dark.

*

“Steve was a very analytical person,” Ware told me. “He looked at things from a probability standpoint, not a human standpoint. And he looked at his life and death that way.”

Around five o’clock on April 20, 2013, neighbors at the Darkwood Beach apartment complex went around to invite Steve Schillinger to a gathering. They found his door ajar. Inside, they discovered Schillinger’s body, a .38 revolver, and a suicide note. He was sixty years old.

In the company’s final days, Schillinger had been saying that he was too old to start over. He hadn’t saved anything from the WSEX heyday; he didn’t even have a bank account. Where would he go? What would he do? The consummate oddsmaker saw a high probability of becoming a burden on others, and that was intolerable: worse than exile, worse than death. “For him, there was no emotional attachment to the decision,” Ware said. “It was all very cold and calculated.”

After Schillinger’s suicide, Ware spent a few more years as a fugitive, then returned home in 2016. The FBI handcuffed him at the airport terminal. He pleaded guilty to a felony and was sentenced to time served, plus probation.

When Ware’s legal troubles were finally over, the Supreme Court was hearing a case that would allow states to legalize sports betting. The mood had changed in the intervening years: a majority of Americans now favored regulating the betting industry. In 2018, the decision came down: states were free to legalize it. Schillinger, Cohen, and Ware had always felt they’d be vindicated one day. “Maybe even ten years [from now], they’re going to look back at my case and say, ‘We sent a man to prison for that?’ ” Cohen told NPR in 2005. (Cohen’s current whereabouts are unknown. He has renounced his American citizenship and declined to comment for this story.)

If Steve Schillinger had come home, faced the music, and waited until the Supreme Court decision, perhaps there would’ve been a future for him, one he couldn’t quite perceive in the black months of 2013. That’s what Ware wagered on. With a fairly thin and suspect résumé after decades at large, he applied to one of the newly legal sports books in New Jersey. After all, he’d helped start up one of the first online sports-betting enterprises, a multimillion-dollar business that had juggled probabilities in real time, fielding hundreds of thousands of bets a month. But his application was denied; he was a felon.

Michael LaPointe is a writer in Toronto. His debut novel, The Creep, will be published by Random House Canada in 2021.

March 2, 2020

My Life as Lord Byron

Aubrey Beardsley’s illustration from page 87 of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé: A Tragedy in One Act. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir was on. We’d seen it before, but who can resist a romantic fantasy between a young widow and the ghost of a ship captain in a seaside English village? Certainly not my mother, who loved England, romance, and ghosts. My mother communicated with ghosts regularly. This was such a matter-of-fact part of her life that I had taken it for granted from the very beginning; I wasn’t sure what I believed about ghosts themselves, but knew for certain that, whatever they were, my mother saw them, sensed them, and spoke with them. Stories about the ghosts of former residents alerting her to their presence at open houses for coveted real estate, chats with those who’d passed to the other side, et cetera: these were simply part of the ongoing family conversation about multiple realities unfolding simultaneously.

“You know, I had to help this guy who died out there a little while ago,” she said, waving a hand over her shoulder at the Puget Sound. I was back on Bainbridge Island between periods of travel. My mother was house-sitting the big waterfront home of some people who worked for Microsoft and had gone to Australia. She sat tucked into the corner of the sofa, wrapped in a blanket and holding a cup of tea.

“Really?” I said. It was the word that came out of my mouth most often on visits to the island, in a way that meant, “Please tell me more, and I’m also not sure what to think about this.”

“I saw a crew out searching for him one evening,” she said. “He was a diver for some official department. He’d gone missing.”

“My God,” I said.

“So I spoke to his ghost,” she said. “He was very confused. Like, Whoa, where am I? What’s happening? He didn’t get that he was dead, you know? He had a lot of cocaine in his system. I had to break the news to him.”

“Jesus,” I said. This was new. It could’ve made an interesting contemporary update of The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, which is about a woman, played by Gene Tierney, who rents a house on the English coast that’s haunted by an irascible sea captain, played by Rex Harrison. She helps him write his memoirs from beyond the grave. It has a remarkable ending for a romantic comedy: in her old age, Tierney’s character dies, united with Rex Harrison at last.

“I had to tell him gently, of course,” she said. “It’s best to be gentle with a ghost that doesn’t know it’s dead. It can come as quite a shock to them.”

I thought about all of this for a moment. “So you helped a coke ghost cross over,” I said.

My mother laughed. “A coke ghost!” She liked that. “Well, he was a good person.”

“Poor guy,” I said. “I wonder if a lot of divers use cocaine on the job. Are they like the long-distance truckers of the sea?” I later looked up the details of the case. My mother shunned the news, generally feeling it to be a conspiracy of negative vibes, fear-mongering, et cetera, et cetera. “Not in my home” was her attitude toward the news, as though it were a kind of pornography. (Lord knows it can be.) She was sensitive to the world, like me. And she wasn’t wrong about the news, exactly. I, however, occasionally swung to the opposite extreme. I wanted to know everything, especially everything scandalous, criminal, tragic, everything indicative of human evil, folly, and misguided passion. “Evil and disaster are part of a well-rounded diet,” I used to say to her, when I tried to persuade her to listen to the news. “They’re part of the informational food pyramid.” The diver, I learned, had been just twenty-four when he died of “salt water drowning” and acute cocaine intoxication. I had just turned thirty.

Ghost talk interested me because it often sidestepped the personal. Or, to be more exact, it seemed to me like a way of repurposing personal details in riddles, fables, and metaphors. The only times it rankled were when my mother said things like, “You’ll know when I die, because I’ll come visit you.” Meaning, in other words: “Don’t worry, I’ll haunt you when I’m gone.”

I didn’t mind being visited by the spirit of my dead mother in theory, but it seemed like a potential violation of the well-protected private life I’d worked so hard to cultivate. Could one make a convenient appointment for visitations by one’s dead mother, in the same way that one made sure to call every couple of weeks? Or did the ghosts of dead mothers know when to show themselves without making a scene? I had read that Oscar Wilde had experienced a ghostly vision of his mother on the night of her death across the country, so maybe it was just her Irish side coming out. Delightful Oscar, who wrote of Salome requesting the head of Jokanaan on a silver platter as a reward for her dancing. The subject of being eventually visited by my mother’s ghost brought me back around to those images—those decadent Aubrey Beardsley drawings with their insectile human figures, Salome feverish and floating on air, her eyes gazing deep into those of Jokanaan’s severed head.

In any case, ghost life was a branch of my mother’s supernaturalism that I rather enjoyed. Another branch, the existence of aliens, also entertained. On another visit I’d sat in a similar formation with my mother—her on the couch, me sitting across from her in a chair—but in my childhood home, which had recently been rebuilt after a freak fire left it half-collapsed and charred. I listened to her speak at great, almost trancelike length about Paul Hellyer, the ninety-one-year-old former Canadian defense minister who around that time decided to announce that world leaders were hiding secret documents that confirmed the existence of UFOs and alien species. Aliens, he said, had been visiting earth for thousands of years; they were, he said, unimpressed with the way we lived, feeling that we spent too much money on military expenditures and not enough on helping the poor.

“So the aliens are leftists?” I said, throwing this into the whirlwind of my mother’s speech about aliens.

She continued repeating and riffing on Paul Hellyer’s claims, frightening me a little with her fervor, passionately agreeing that certain modern technologies, such as the Kevlar vest and LED light, had been helped into existence by aliens. Certain species of aliens, according to Hellyer, passed for human, among them a group referred to as “Tall Whites.” This makes me laugh, since it described me as a person. The “Tall Whites” were working with the U.S. Air Force in Nevada. Why was it that aliens always seemed to be pale and to prefer hanging out in the American desert? One rarely heard rumors of, say, aliens roaming Saudi Arabia or Sudan. And the public would have taken immediate issue with reports that a species of aliens known as “Tall Browns” wandered the planet, passing for human. I eagerly awaited the publication of the alien equivalent to Nella Larsen’s Harlem Renaissance novel Passing. What American literature really needed, I thought, was an Alien Renaissance. Maybe it was already having one.

But far be it from me to discourage anyone’s passion for aliens. Even I had my moments in that regard—I was only human. I’m not sure what’s real or true. And, unlike Hellyer’s aliens, I’m often impressed by the way we lived. Human beings built architectural marvels of storytelling around their beliefs; even paranoia, harnessed and applied with focus, can create mental hanging gardens of breathtaking sublimity, reflections of the human psyche at its most baroque. Stories, novels. Essays.

However, it saddened me sometimes to venture out onto the branch of my mother’s growing preoccupation with past lives, which, having moved on from the coke ghost, we began to do there in the living room of a high-earning, absent family’s seaside home.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about Lady Duff lately,” my mother said.

“Really?”

I knew what this meant. My mother had been fascinated by past lives for … well, longer than I’d been alive. By the time I came on the scene—a story replete with its own significant paranormal touches, including an Indian guru who, my mother said, astral-projected himself into her bedroom to hang out with her while she was pregnant—her interest in things like hypnotherapeutic past-life regression and speaking with the dead was already firmly established. She’d experienced a crack-up shortly after my birth, owing, to hear her tell it, to a mix of severe postpartum depression and being overwhelmed by the wide-open, wildly swinging doors of perception. During that time my brother and I were briefly placed in the care of friends and family. My mother and I were separated for two weeks. I don’t remember any of it. I’ve had my own crack-ups over the years, including a brief but intense and humbling one a couple of months before turning in my book of essays. It runs in the family. It fascinates me. A relative a couple of generations back, pushed to see how long he could spend inside a hot tank in the desert during his army training, lived the rest of his life after that with a permanently fractured psyche. Another spent her final days in Ypsilanti State Hospital, setting for the book The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, in which a social psychologist makes three men, each of whom believes he is God, spend time together to see what they’ll do. (They went on believing.) In any case, my earliest memory of my mom talking about past lives involves a skit on the children’s TV show Sesame Street that reduced me to hysterical tears. I was a little boy.

Everything was unfolding like normal, the usual colorful, festive parade of multicultural puppets and humans living and singing in relative harmony—my mother wept years later when Jim Henson died—until a segment came on that terrified me. In it, confirmed bachelor housemates Bert and Ernie, whom I normally enjoyed, explored an Egyptian pyramid. (They naturally refrained from identifying this as a tomb.) Bert’s Egyptophilic enthusiasm did nothing to quell the creeping fear of Ernie, who followed his companion with reluctance. They came upon two ancient statues that, eerily, wore faces identical to theirs. I became nervous at that point. Ernie told Bert he wanted to go home, that he was frightened, but Bert insisted on staying. He left Ernie by the statue to investigate a dark tunnel around the corner. Then, while Ernie’s back was turned, the statue in his own likeness momentarily came to life, tapping him on the head with his crook. Ernie wailed in fear, calling for Bert, to whom he explained the source of his panic.

Bert sighed. “This statue here, made of stone thousands of years old, it tapped you?”

“That’s right, Bert,” said Ernie.

“Ernie,” said Bert, nasal and skeptical, “Ernie, don’t you think maybe you were using your imagination, hm? It didn’t really tap you, you’re just imagining it, hm?”

Bert once again left Ernie, that clownish imagination-user, who tried to talk himself down. With confidence tenuously restored, he said to the statue, “You didn’t tap me, did you, statue?”

“Sure I did,” said the statue, coming to life again, its voice echoey. Its laughter, uncannily Ernie-like, a staccato hiss, threw me into a state of terror. My screams and crying summoned my mother, who must have thought I’d hurt myself.

“What’s wrong?” she said. “What is it?”

Afraid to look at the TV, I pointed at it, blubbering about Egypt and statues. “It came to life,” I said, still crying. “It came to life!”

My mother held me on the couch, comforted me. “Shhh,” she said, “it isn’t real.” Like many children, I was fascinated by ancient Egypt; I wanted to bring home from the library as many books about the pyramids, the Sphinx, and the pharaohs as I could. Maybe this supported my mother’s impulse, at that moment, to introduce the idea that I may have had a past life in ancient Egypt.

I stood up next to her on the couch, holding her hands, and sniffled, curious.

“I’ll bet you were a pharaoh then,” she said.

Thus the idea of past lives became part of the family language—nothing unusual, really, just the taken-for-granted reality that one had lived before in a time and place other than this one, and that one would likely live again, live elsewhere.

For my mother, affinities for another time and place suggested a literal lived relationship to them. A fascination with Paris in the twenties, as culturally prescribed or insisted upon as that fascination might be, hinted at having once walked through the era oneself. I have many thoughts about this. At my most critical I consider suspect the aspirational quality that marks many past-life fantasies—that and a certain received cultural nostalgia, modes of historical fantasy that limit the variety of lives we’re meant to imagine we’ve lived. Patterns in past-life fantasies—much like fantasies about one’s present life—have their own loaded preoccupations. They reflect our desires and our frustrations. Then again, I’m intrigued by childhood psychology studies reporting that, at a certain age, usually shortly after children begin to speak in coherent sentences and stories, many people have been known to spout uncannily cogent narratives that have the appearance of memories from another life. My former drag mentor Glamamore once told me that when she was a little boy she suddenly began speaking Gaelic to her mother and grandmother. And my younger sister had, in fact, told a fully formed and uncanny story when she was little, one that my mother says was a family memory from an earlier generation: a boiler bursting, a house exploding, everyone running outside into the snow.

So my attitude toward past lives remains a tangle: curiosity, skepticism, willingness to accept the limits of my own understanding. I’m a little bit Ernie, a little bit Bert. As with any instrument of human meaning-making, it gets played in different ways, sometimes virtuosically (as though it were, in fact, the one doing the playing), sometimes in clumsy practice or with suspect motives. Which brings me back to the open question of my mother and Lady Duff. Having broached the subject, she produced a printed copy of a photograph from a pile of papers on a folding card table by the window.

“It’s in the eyes,” she said, handing it to me. The photo showed Lady Duff Stirling Twysden with Ernest Hemingway and four other figures, all of them at a table in a café in Pamplona. The eyes of Lady Duff did, indeed, gleam with creative fire, a radiant zeal and lively wit that my mother shared to a certain extent. “Do you see it?”

“Yes,” I said, “in a way.”

There was so much I felt I shouldn’t say. These past lives seemed important to my mother, part of a creative process of some kind. My sympathies lay with the creative process and my mother’s relationship with it. She, too, was an artist. Her creative energies seemed to me to be funneling more and more into past lives in which she’d been a woman in the shadow of some legendary male author. Lady Duff, inspiration for Brett Ashley in The Sun Also Rises, was one; she’d also discovered that she’d been the wife of the Irish poet and songwriter Thomas Moore. Why not be Thomas Moore himself? Maybe, I thought, these acts of imagination amounted to a feminist reclaiming of sorts. Was my mother traveling back through time in order to liberate the ghostly lives of women who, flesh and blood and brains, were remembered primarily for their roles in the existential dramas of literary men?

Maybe the ephemeral form this creative energy took satisfied her, though. Maybe it was just me, driven by my fear of annihilation, who wanted to turn living magic into monuments. I wanted us all to stay here, now, in this life. (My mother and I later identified my terror as possibly stemming from those weeks of abandonment when I was three months old. Maybe her going off to be Lady Duff or whoever else felt too much like that traumatic primal separation for me at the time.)

“We’re still trying to figure out who you were back then,” she said. By “we” she meant the other seers and psychics she consulted regularly, and, possibly, the spirit world itself. “We’re thinking Faulkner.”

Though I’d grown outwardly quiet, I couldn’t help but laugh. She said it the way one might suggest a holiday destination. Part of me didn’t particularly like having my soul dragged through history with hers—it was hard enough carving out an independent place for myself in the world without being asked to believe that I was, at any given moment, accompanying my mother on an endless literary Grand Tour through nonlinear time. Maybe I should be more grateful. I don’t know. I complained about it once when she claimed that I’d been around during her tenure as Thomas Moore’s wife. I was the handyman who worked on their cottage.

“So not only do I have to escort you through history,” I said, “I have to fix your house while I’m at it?”

She laughed, but it was as though she feared abandoning me in her time travel experiments. Part of me wanted to say, “Please, Mother, go be Thomas Moore’s wife! I’m a grown man. I can take care of myself.” Shortly after voicing my complaint, however, I was not cut loose from the fantasy, but instead promoted within it. I had not been a handyman after all: I had been Lord Byron. The Right Honorable Lord Byron, notorious and strong-nosed. The mercurial, flamboyant mess of myth responsible for Don Juan, a poem of eunuchs, androgynes, and a hero whose decadent effeminacy makes him the object of lesbian desire in a sultana’s harem. Byron, plagued by rumors and malicious gossip about an affair with his half sister, which, along with those of his homosexual proclivities—a taste for “Greek love,” as it was sometimes referred to—drove him out of England. The role suited me fine: a bit showy, pale, dark-haired, full of unpaid debts and ill-starred love affairs. I could live with having lived as Byron.

Only later would I learn that Thomas Moore—my mother’s past-life husband and Byron’s literary executor—had, after a concerned, contentious gathering with publisher John Murray and several others, been present at the burning of Byron’s memoirs. Moore fought against this injustice. He protested the destruction of the memoirs. Not hard enough, apparently: the opinion of those who found the memoirs scandalous and debauched prevailed. They were torn up and thrown into the fireplace of the publisher’s home on Albemarle Street in Piccadilly. Now they will never be read.

Evan James received an M.F.A. in fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has received fellowships for his writing from Yaddo, the Carson McCullers Center, the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation, the University of Iowa, and the Lambda Literary Writers’ Retreat, where he was a 2017 Emerging LGBTQ Voices Fellow. His personal essays and fiction have appeared in, among others, The Paris Review Daily, Oxford American, The Sun, The Iowa Review, Travel + Leisure, Catapult, Ninth Letter, and the New York Times. His essay “Lovers’ Theme” was selected as the winner of the 2016 Iowa Review Award in Nonfiction, judged by Eula Biss. Born in Seattle, he now lives in New York and teaches creative writing and English at the Pierrepont School.

© 2020 by Evan James. Excerpted from I’ve Been Wrong Before , by Evan James, out tomorrow from Atria.

February 28, 2020

Staff Picks: Long Walks, Little Gods, and Lispector

Jessi Jezewska Stevens. Photo: Nina Subin.

Anyone who has googled their own name knows the curious thrill of watching the page populate with alternate identities. Percy, the narrator of Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s debut novel, The Exhibition of Persephone Q (out next week), suddenly finds herself awash in that potent mix of familiarity and alienation. She indeed googles herself not long after receiving a new exhibition catalogue of photographs, taken by her ex-fiancé, of a naked woman with a hidden face. Percy feels certain the woman is her—she recognizes the apartment, the body—but she cannot prove it, and the more she insists, the less plausible it all starts to seem. Previously a person of apathy, Percy has long been satisfied to be taken through life by a slow-moving current as invisible to herself as it is to those around her. She learns she is pregnant and keeps not mentioning it to her husband; she goes out for long walks at night, makes money in vaguely nondescript ways, and seems generally on the brink of disappearing from her own life. The arrival of the catalogue upends her complacency and sends her reeling into a quest of self-discovery and assertion amid the social landscape of post-9/11 New York. Stevens uses her wry perspective and lucent style to pose a deceptively simple question of personhood: How could you prove who you were? —Lauren Kane

It is an uncharitable position, but I confess: I was nervous about reading Marcial Gala’s The Black Cathedral, a 2012 novel whose English translation, the writer’s first, didn’t appear until this January. Polyphonic novels are tricky things, with as many pitfalls as they have voices, and of all the many challenges translators face, slang and informal language must rank among the stickiest. On both fronts, though, Gala’s book turns out to be a pleasant surprise: each voice is distinct and individualized, and although between the covers they push and pull against one another, once you close the book you realize he has been making them work together all along, building a structure much like the cathedral of the title. Anna Kushner, too, deserves a great deal of praise—there is nothing stilted or forced about the translation from the Spanish, and it shifts gracefully from register to register and character to character. I am grateful to both Gala and Kushner, and if it’s not too presumptuous to impose, since it turns out that this is in fact part of a trilogy about the city of Cienfuegos—can I please ask for the rest? —Hasan Altaf

Meng Jin. Photo: Andria Lo.

If the mark of a good novel is its ability to delicately rewire the reader’s brain, then Meng Jin has given us a very good novel in her debut, Little Gods. The central character, a gifted physicist named Su Lan, theorizes a universe that tends toward order, not chaos. A broken water glass can reassemble, spilled water flying back into it. What else is this but time moving backward? The fact that humans experience time differently does not make it impossible. Su Lan’s thought experiment turns slowly in the background, stretching our puny human preconceptions, as we move through a nonlinear account of her life in space-time, told by a neighbor, a husband, a friend, a daughter. What is order? In an early scene, Su Lan paints a rented room in a new city white from floor to ceiling, creating an impression of blank limitlessness. For her, the past—famine, poverty, dirt, village life—is chaos. Over and over, she seeks a clean start. She moves with her toddler, Liya, to America and, once there, from place to place, job to job, never rooting, retreating further and further into the open plane of her mind. Liya, on the other hand, craves the personal order of “a story so deep in the mud of history it could be passed as identity—as self!” This is the story that Meng Jin tells, and it’s a page-turner—but all the while it winks, reminding us that possible explanations in our universe are as varied as the beings who populate it. —Jane Breakell

Since its inception in the late fifties, West Side Story has courted controversy. The musical’s composer, Leonard Bernstein, made half-hearted efforts to “research” Puerto Rican culture at a gym in Brooklyn. Its lyricist, Stephen Sondheim, was more forthcoming about his lack of knowledge: “I can’t do this show,” he admitted. “I’ve never been that poor, and I’ve never even met a Puerto Rican.” Ivo van Hove’s new version, which had its opening at the Broadway Theatre last week, reimagines this complicated production. It is a cinematic spectacle, taking a cue from Daniel Fish’s adaptation of Oklahoma! by projecting live video footage onstage. The West Side Story camera operators are agile and athletic performers in their own right, bringing the audience into intimate conversations and revealing the queer desire that underpins the show. I was particularly excited about the recruitment of the Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, whose avant-garde work is a far cry from traditional Broadway dance. Her aesthetic, however, seems to have been restrained for the New York audience. The choreography for “Cool” is most authentically De Keersmaeker, the dancers moving easily in a tight, militant formation and embodying the muted tension of the song. Van Hove’s bold vision seems, at times, not wholly realized. Yet this new production engages with the show’s powerful and problematic legacy in ways that others do not. —Elinor Hitt

At the center of Amina Cain’s Indelicacy is the question of work. Vitória, the main character, begins the novel as a cleaning woman in an unnamed art museum in an unnamed city; by the end, after her unexpected marriage to a rich man has dissolved, she is divorced and a writer. Fairy tale isn’t quite the right term to describe Cain’s prose; there is a fable-esque quality, yes, in its refusal to name places or dates, and she touches on familiar archetypes—Cinderella, the woman in need of a room of her own, the well-meaning but useless husband—with the ease of spinning straw into gold. Ultimately, though, this novel is a celebration of writing, and women’s writing in particular. Characters are named after those in the works of Clarice Lispector, Octavia Butler, and more. Vitória’s interest in writing, rather than children, is taken as evidence by her husband that she is unwell, and she alludes to a childhood marked by monetary difficulties and too many mouths to feed. But Vitória pushes on, carving out time to write, and by the novel’s end, Cain makes a compelling argument for the spiritual necessity of creative freedom. —Rhian Sasseen

Amina Cain. Photo: Polly Antonia Barrowman.

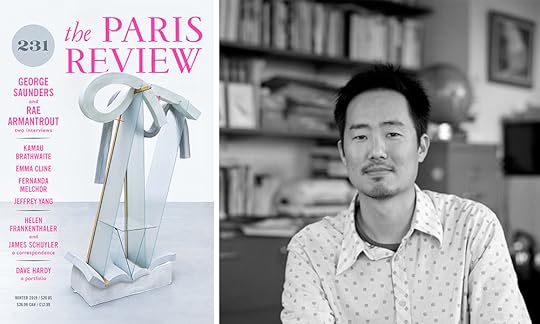

Learning Ancientness Studio: An Interview with Jeffrey Yang

Jeffrey Yang. Author photo: Nina Subin.

On an overcast Friday this January, I rode the Metro-North up along the Hudson to meet Jeffrey Yang at Dia:Beacon. Yang’s wife is an educator there, and the couple has lived in the town of Beacon, New York, for the past fifteen years. His poem in The Paris Review’s Winter issue, “Ancestors,” centers around an exhibition at a gallery in Seoul, South Korea, and the piece made me curious about his work as it overlaps with visual art. When I asked Yang if he might show me one or two of his favorites at Dia before we sat down to talk, my request was met tenfold. We embarked on a comprehensive tour: Dorothea Rockburne’s complex mathematical concepts alchemized through abstract, geometric installations; Richard Serra’s heavy, leaning sculptures of steel; the minimalist reimagining of a book of hours by On Kawara (about whom Yang recently wrote here). The pieces that he found exciting were as aesthetically diverse as his poetry.

The world of a Jeffrey Yang poem is eclectically populated. His abecedarian debut collection, An Aquarium, is a taxonomy of aquatic life that incorporates characters from Aristotle to Emperor Ingyo. His most recent collection, Hey, Marfa, takes the Texas city (coincidentally home to Donald Judd, Dia:Beacon darling) as its subject, and examines the strange, transient nature of its history alongside paintings and preparatory drawings by Rackstraw Downes. In between, he edited the collection Birds, Beasts, and Seas, a seventy-fifth-anniversary tome of poetry from the New Directions archives, and he has translated work by Liu Xiaobo, Su Shi, and Ahmatjan Osman.

Yang is warm and familiar. For every insight into a piece we were looking at, he had a humorous anecdote about Dia:Beacon—he was serious about art without solemnity. After our conversation, he walked with me to town to pick up a sandwich and then saw me and my lunch onto the train. In his career and his process, Yang has pursued his interests without expectation, with the simple faith that they will lead him where he is meant to be going. To all accounts, they have.

INTERVIEWER

What were your first forays into poetry like?

YANG

I probably started with Chinese poetry, because both my sister and I went to a Chinese school on Saturdays, and we were required to memorize and recite poems. I remember having some children’s poetry anthologies, too, and enjoying the rhythm and the music of those poems.

At the University of California, San Diego, there was a pretty experimental literature department. I took one of my first writing classes with Carla Harryman, who was visiting. Melvyn Freilicher, Fanny Howe, Rae Armantrout, Wai-lim Yip, Jerome Rothenberg, Quincy Troupe, all taught there. Amiri Baraka also taught as a visiting writer. They were all involved in a more avant-garde idea of poetry in different ways. I remember reading the anthology Premonitions, published by this press called Kaya, an Asian American press, which was eye-opening for me. I hadn’t heard of most of the poets in that book, and it all felt fresh to me, how they were really pushing the language. It included some of Theresa Cha’s work, which was also performative and visual. I was curious.

INTERVIEWER

Did you know early on that you wanted to be a poet? Did you conceive of yourself as a poet?

YANG