The Paris Review's Blog, page 155

July 28, 2020

Redux: A Aries, T Taurus, G Gemini

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Kay Ryan. Photo: Jennifer Loring. CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...). Via Wikimedia Commons.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re feeling esoteric. In the cards are Kay Ryan’s Art of Poetry interview, Fernanda Melchor’s “They Called Her the Witch,” and Charles Bernstein’s “Twelve-Year Universal Horoscope.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or, better yet, subscribe to our special summer offer with The New York Review of Books for only $99. And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Kay Ryan, The Art of Poetry No. 94

Issue no. 187 (Winter 2008)

I’d bought a tarot deck—this was the seventies—a standard one with a little accompanying book that explained how to read the cards, lay them out, shuffle them—all those things. But I’m not a student and was totally impatient with learning anything about the cards. I thought they were just interesting to look at. But I did use the book’s shuffling method, which was very elaborate, and in the morning I’d turn one card over and whatever that card was I would write a poem about it. The card might be Love, or it might be Death. My game, or project, was to write as many poems as there were cards in the deck. But since I couldn’t control which cards came up, I’d write some over and over again and some I’d never see. That gave me range. I always understood that to write poetry was to be totally exposed. But in the seventies I only had models of ripping off your clothes, and I couldn’t do that. My brain could be naked, but I didn’t want to be naked. Nor was I interested in the heart, or love. The tarot helped me see that I could write about anything—even love if required—and retain the illusion of not being exposed. If one is writing well, one is totally exposed. But at the same time, one has to feel thoroughly masked or protected.

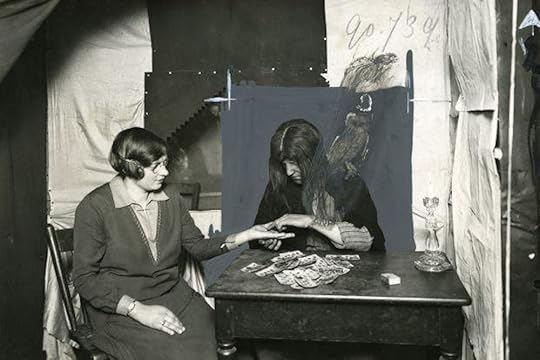

Fortune-teller reading a woman’s palm, 1936. Photo: Nationaal Archief. Via Wikimedia Commons.

They Called Her the Witch

By Fernanda Melchor

Translated by Sophie Hughes

Issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

They called her the Witch, the same as her mother; the Girl Witch when she first started trading in curses and cures, and then, when she wound up alone, the year of the landslide, simply the Witch.

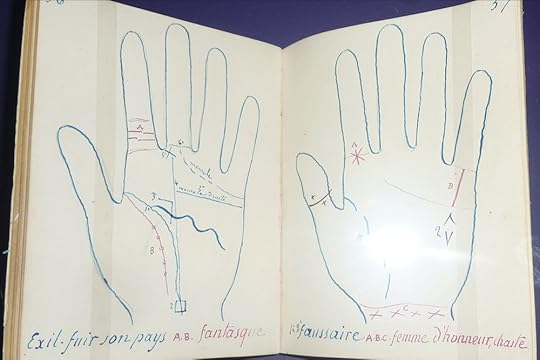

Spread from Manuel pour la pratique de la chiromancie, by Jules Charles Edmond Billaudot, a.k.a. Le Mage Edmond, ca. 1870. Photo: MUCEM Marseille, via Wikimedia Commons.

Twelve-Year Universal Horoscope

By Charles Bernstein

Issue no. 230, Fall 2019

Key: A Aries, T Taurus, G Gemini, C Cancer, L Leo, V Virgo, Li Libra, S Scorpio, Sa Sagittarius, Ca Capricorn, Aq Aquarius, P Pisces. Each section covers one year, then rotates.

A2019, T2020, G2021, C2022, L2023, V2024, Li2025, S2026, Sa2027, Ca2028, Aq2029, P2030

Anticipated reversals occur in unanticipated locations: avoid planar surfaces. As Saturn and Pluto come into alignment, prepare for irrepressible nostalgia. Casual attachments provide a medley of diversions from long-term fantasies. Mix of sulfur and magnesium is at its height on the twelfth and twenty-ninth: stay clear of disarticulating headwinds while remaining open to miscalibrated address. Seek pine- and coconut-flavored dishes. Preferred alcohol: Anisette (neat) …

To read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. And for a limited time, you can subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for just $99.

The Landscape That Made Me

Photo: Corey Coyle. CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...). Via Wikimedia Commons.

In the summer of ’89, it barely rained. More than fifty days passed without a drop. The corn dried up. The crops didn’t yield. Acres of farmland turned brown in the sun. Neighbors and livestock died in the heat; wildfires tore across the plains. But we were too young to worry, to know what the word drought could mean to a small Midwestern town like ours, or the miles of farmland that surrounded it.

We spent our days in the fields and woods, the sun high and bright through the leaves. We traveled in packs; we wandered alone. We were great in number; we were two at a time. We scuffed up our jeans, scraped up our knees, tore holes in shirts that got snagged on branches. We climbed the trees and yelled into the wind, and no one heard but us. We ran for miles, the dry summer grasses nicking our shins, trying to find the place where land met sky. We hiked through the goldenrod, up to our waists, our eyes swelling and legs itching, and laid down to watch the clouds move east. And then we walked back the way we came, outlines of our bodies on the ground behind us, bright-yellow dust on our skin.

We were people of the prairie. We were people of the trees. We were the maple and birch, the oak and elm. We were corn and wheat and soy, we were the black earth that grew it. We were bluestem and switchgrass, we were rivers and lakes. And out past the horizon of hardwood and pine, we were mountains.

We were girls. We were boys. We were neither and both.

We were small. We were nothing. We were taller than the trees.

*

In southwestern Wisconsin, where I grew up, there exists a geological phenomenon. It’s called the Driftless Area, a narrow stretch of land that, somewhat miraculously, was bypassed by the last continental glacier. What results is a strange, rare terrain that extends some twenty thousand square miles, composed primarily of that small corner of the state and edging over the borders of Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois. Its name refers to drift—rocks and gravel, silt and clay and sand—the sediment left in the wake of retreating glaciers. It’s the stuff that exists beneath the surface of most terrain. But here in the Driftless Area, such elemental makeup is scarce, when it exists at all.

The Upper Midwest owes much of its landscape to the movement of the glaciers: Minnesota’s ten thousand lakes, carved from the earth by walls of ice and filled with water; the long rolling prairies of south-central Wisconsin and northern Illinois. But the Driftless Area, also known as the Paleozoic Plateau, is marked instead by a landscape wholly unlike the rest of the region: that of rolling hills and steep, forested hillsides that stretch down to valleys, sharp limestone cliffs and bedrock outcroppings with lakes and quarries below them, paths cut by winding rivers and cold-water streams. If you look to the horizon, you’ll see the most striking part of the region: small mountains, or mounds, and among them monadnocks—strange, solitary peaks that seem to rise up, out of nowhere, from the middle of a plain.

These are the tops of ancient mountains, whole ranges long buried beneath the surface of the earth. After generations of erosion, when layers of softer rock have been washed away in the formation of the surrounding valleys, the harder rock is all that remains, emerging from the earth as isolated mountains.

The mountains shouldn’t be here. They’re incongruous, out of place. They’re an anomaly, an abnormality, a glitch in the system. They’re also beautiful. The landscape of Wisconsin is both forest and farm, lands both flat and rolling. It is endless prairie and deep, untouched woods. It is a place of lakes both great and small, of rivers, creeks, and streams. It is a place whose lands are neither one thing nor the other, a whole containing multitudes. But the mountains, they’re not quite right. Amid the rest of the landscape, it would seem clear to someone first encountering them that they just don’t belong.

This is the landscape that made me.

*

In the summer of ’98, we drank pilfered beer in unfinished basements. We stayed up late and cut our fingers with scissors, pressing them together until our pulses beat in time. We snuck out to the softball field just before sunrise, the sky a blaze of black and blue. We ran the bases, our legs wobbly, the sand and rock beneath the mud, our bare feet slapping against the cold slick of it. We passed a bottle between us, taking long pulls like old pros, like we watched so many people do before us. We rolled our bodies like barrels down the hill to center field, where cleat marks were carved in cold earth, where the ghosts of mosquitoes still buzzed. We breathed hard, our backs on the ground, our knees and elbows slick with sand; our bodies close but not touching. Silent as the sky before a storm.

We were girls but not yet women. We were something in between. We were fifteen; we were on fire. Our skin was hot all the time, buzzing and open and raw, like it could be peeled off entirely—a whole girl-shaped shell, like the thin shedding vellum of a sunburn. To quiet the constant itch of it, we did everything we could to feel something else, to feel anything or nothing at all. We drank, we fought, we went without sleep. We lay on our backs on bedroom floors and turned the music up loud, longing to be the subjects of love songs. We talked on the phone late into the night, the long pink coil of cords wrapped around fingers and wrists. Breasts smashed into sports bras, dirt beneath black-painted nails, we were starting to think about the power our bodies might hold. We did not yet know of the power they lacked, or that which could be taken. We tried on skirts, and our shirts got tighter. We shaved our legs and hair-sprayed our bangs and painted our eyes. We rode with boys in pickup trucks out into the country, the summer wind in our hair. We started kissing those boys, and sometimes let them go further. We might have dreamed of kissing girls, though none of us had the words for it yet.

We ached for everything, and for anything other than this: the slow, quiet life of our small hometown, its stillness and silence, the feeling we were stuck. We knew that somewhere, beyond this place, the whole huge world was waiting.

Melissa Faliveno is a writer, editor, teacher, and author of the debut essay collection Tomboyland, published by TOPPLE Books in August 2020. The former senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine, her essays and interviews have appeared in Esquire, Bitch, Ms. magazine, Prairie Schooner, DIAGRAM, and Midwestern Gothic, among others, and received a notable selection in Best American Essays 2016. She has taught nonfiction writing at Sarah Lawrence College and Catapult, and starting this fall will be the 2020–2021 Kenan Visiting Writer at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Originally from small-town Wisconsin, she currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Excerpt from Tomboyland. Copyright © 2020 by Melissa Faliveno. To be published in August by TOPPLE Books. The original “Driftless” essay appeared in a different form in Midwestern Gothic © 2015.

Apprehending the Light

Photo: Scott O’Connor.

On a mild evening at the end of May, the day after the official U.S. death toll from COVID-19 reached a hundred thousand, I drove thirty miles from Los Angeles to see a work of art. I’d first visited James Turrell’s Dividing the Light seven years before with my wife and son. We shared a night of quiet beauty in the outdoor installation on the campus of Pomona College. That experience stayed with me, a moment of meditative calm to remember when things were hectic or difficult. But the feeling had faded over time. Now, in the midst of the pandemic, I hoped that by returning to the site I could recapture some of that peace.

I listened to the news as I drove, discussions of the number dead. I tried to wrap my head around what it meant that the lives of a hundred thousand people in this country, and so many more around the world, had ended in just the last few months. But after a while I turned off the radio. The enormity of the tally made it impossible to comprehend the individual lives lost. The number was a shapeless whole that consumed its separate parts.

Dividing the Light is one of Turrell’s Skyspaces. Once inside, the Minimalist architecture blocks a visitor’s view of the vastness above, except for an aperture cut into a wall or ceiling, which focuses attention on that single circle or square of sky. The Pomona College piece is an unassuming metal pavilion nestled into a courtyard between academic buildings. There’s a sixteen-foot square opening in the center of the pavilion; a shallow reflecting pool of the same dimensions sits directly below. A low wall of granite benches rings the perimeter, coral-colored, like the light one often sees in the west at the end of a Southern California day.

It was just before sunset when I reached the empty pavilion. I stood and looked at the opening above, the whitish-blue square of sky that seemed removed from the rest, as if it had been cut out and set apart. My mind wouldn’t stop racing, though, cycling between the U.S. death toll, the even larger worldwide number, and the staggering numbers yet to come.

My mask didn’t fit right. It was hard to breathe. I stayed standing because I was too hyperconscious of the virus to sit on one of the surrounding benches. I was sad and anxious and feeling useless, wondering why I had made the trip. I had felt this way for the last two months, but that was the slow-motion version, stretched over blurred days of incessant hand washing and Zoom meetings and wiping down groceries, worrying about my son’s cough and my neighbor’s cough and my father’s cough on the phone five thousand miles away. Worrying selfishly about my own health while a hundred thousand people I didn’t know had trouble catching their breath and then couldn’t breathe and then stopped breathing altogether.

*

There is actually one way I can imagine large numbers of people—the crowds at baseball games. It seems inadequate for the gravity of the current moment, but I know Fenway Park holds thirty-seven thousand people, and fifty-six thousand can fill Dodger Stadium. One of my favorite things to do at a game is to take a moment away from the play on the field to look around the stands. All those faces looking toward the pitcher or batter, all those bodies half rising from their seats, following the trajectory of a fly ball threatening the outfield wall. Will it carry? Will it fall?

Once the ball clears the scoreboard or drops into the right fielder’s glove, that energy explodes in jubilation or fizzles in disappointment. But it’s that anticipatory moment before the question is answered that stays with me, thousands of us rising in collective hope.

*

Every morning I check the data. The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. New infections, cumulative infections, positivity rate. The number of deaths by day, week, month. Scrolling through the numbers, I almost feel like I know what I’m looking at, like I have the training and context to make sense of the charts and graphs filling my screen. I’m not alone. The LA County Public Health Department tweets their numbers every afternoon and the feed fills immediately with comments, other amateur experts parsing the data.

The data are crucial. Researchers, scientists, and medical professionals need the data to make informed decisions. But what do the rest of us do with it? How does it add to our understanding of what’s happening, and to whom? The data feel solid in a way the pandemic most certainly does not. But that solidity comes at a price. It turns this disaster into an abstraction, increasing the distance between those of us on the sunlit side of the illness and those suffering in the dark.

During his daily coronavirus briefings, New York governor Andrew Cuomo almost always attempted to reject that abstraction when he gave the tally of the previous day’s deaths. The number was not just a number. “Three hundred and sixty-seven deaths,” he announced on April 26. There was a chart on the screen beside him, a blue line climbing. “Which is horrific,” he said. “There is no relative context to death. Three hundred and sixty-seven people pass, three hundred and sixty-seven families.”

*

The sound of the water cresting the low walls of the reflecting pool was surprisingly loud, another impediment to the peace I’d hoped to find in Turrell’s pavilion. I tried to block it out, but it was insistent. After a while I thought it might have another purpose: maybe the water was designed to act as a buffer against the noise of the outside world, the car horns and barking dogs and passing conversations that just a few months ago would have been swirling distractions in the evening air. That night in late May, though, as on so many evenings during the pandemic, there was an unnerving silence. The water’s steady white rush underscored that sonic void. I couldn’t ignore it any longer.

I took a breath and paid attention to the silence. For months I had considered it a formless blank, the simple absence of sound. I was wrong. It had so many different parts: the fear and grief and withdrawal from public activity that so many of us were feeling, but also the keen silence of vigilance, the choice to quiet our lives in the hope of saving our neighbors. And surrounding the silence, an unfathomable uncertainty, the dawning realization that there is no end in sight, that we’ll have to learn to live in this uncharted space.

*

Baseball has always been a sport driven by, and viewed through the lens of, statistics. As a kid in the eighties, I pored over the backs of baseball cards, memorizing my favorite players’ batting averages and home run totals. Those statistics hadn’t changed much since the game’s beginnings a hundred years earlier. But in the late seventies a movement began to rethink the ways of viewing player performance, and to go deeper into those reevaluations. That movement broke into the mainstream in 2003 with Michael Lewis’s Moneyball, which opened the floodgates. Many of the game’s long-standing suppositions (walks are for wimps) have been upended (walks are, in fact, a great way to get to first base). We can now determine the percentage of each run created by a particular player, and the rate at which a pitcher spins the ball to fool a batter. Some of us now watch games with a second screen open on our phones or laptops, pulsing with charts and graphs updating in real time.

Advanced stats have enhanced my enjoyment of the game. During the lulls between innings, my son and I discuss batting averages and home run totals, but we also debate FIP and WRC+ (don’t ask). One of the most anticipated rites of spring in our house is the arrival of the Baseball Prospectus annual, a compendium of advanced stats as thick as a midsize city’s phone book. Watching the data play out during a game feels like finding new pieces to a puzzle we thought we’d solved long ago.

But I wonder if the data has changed our perception in other ways. Does the obsession with numbers detract from our appreciation of the sport’s physical beauty, the lazy arc of a long fly ball, the slide into second base that slips below the shortstop’s tag? Does focusing on metrics reduce players to decimal points and percentages? We don’t have stats to measure leadership or teamwork. Sometimes these intangibles are derided by more number-centric fans. But aren’t the attributes I value most in myself and others—our capacity for love, our ability to empathize—intangible? When a player loses his spot on a team because of a falling performance metric, that’s not just a number that’ll be replaced with another, higher number. That’s the loss of a job, a dream, a sense of self. That’s a life changed forever.

*

About ten minutes before sunset the pavilion’s ceiling began to glow. What started as a flat, metallic gray darkened, subtly, to a deep purple. There are LED lights secreted away in the Skyspace, synchronized to the atomic clock, and every evening just before sunset they begin a programmed pattern, bathing the underside of the pavilion with gradually shifting colors. I was still standing alone in the space, still anxious, but the change in light pulled me from my thoughts, quietly but firmly calling for my attention. The square of fading blue sky, now surrounded by a field of violet, seemed to flatten, losing its depth. It looked like a painted canvas in a purple frame. With a ladder I was sure I could’ve touched it.

The color of the pavilion continued to change, sunflower yellow to rubber-ball pink to a wine red, altering the appearance of the square of sky. One moment it was that painted canvas, in the next it acquired sudden depth, making me feel as if the entire space had flipped upside down and I might tumble through that opening. Each change confounded my understanding of what I saw and felt, proving my beliefs wrong, or at least incomplete. Turrell calls this our “prejudiced perception,” the concept of normalcy we drag around with us most of the time, our tendency to stay sheltered within generalizations and abstractions.

Those prejudices don’t fade without a fight. My brain, still not completely quiet, kept up an irritating, insistent reminder: this is just the sky, a small patch of what always surrounds you. It’s not unique, or extraordinary. I hadn’t looked at the sky much that day—not on my drive or the walk across campus. But here in Turrell’s space I couldn’t stop looking. I thought of a line from one of John Cage’s poems, about how certain moments are “invitations to events at which we are already present.”

Of course it was just a small patch of sky. Of course it had been there all along. But now I was finally paying attention.

*

A few days before the 2008 season, the Red Sox and Dodgers played an exhibition game to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the latter team’s arrival in Los Angeles. The game was played, like the Dodgers’ first games in the city, in the Memorial Coliseum, a concrete leviathan that sits just south of downtown, where it has hosted, among other massive events, two Olympics, the Billy Graham crusades, and the last ninety-plus years of USC football.

The game started in the late afternoon, and like most LA crowds this one filtered in gradually, taking its time. By the time the sun had set, though, there wasn’t even standing room to spare. Our rooting interest was split, but the mood was congenial, and increasingly celebratory. We began to notice that this was a very big crowd, much bigger than any at Dodger Stadium or Fenway Park. As we all looked around, there was a growing sense that we were part of some thrilling, illogical stunt, like those old photographs of college kids stuffing themselves into phone booths. It’s the kind of memory that feels wistful and retroactively uneasy in our current reality of physical distancing: so many bodies shoulder-to-shoulder, laughing, cheering, shouting.

The game also felt like a stunt. Wedging a baseball diamond onto a football field involved, among other eccentricities, an absurdly high net in shallow left field, only 201 feet from the batter’s box. The home runs came early and often. Any remaining pretense that this was an authentic game fell away completely.

But by then, we understood that the game wasn’t the point. We were the point, the crowd, our sheer enormity. Every inning, spontaneous bursts of applause rose from a section when the thousands of people noticed, as if for the first time, the thousands in a section on the opposite side of the stadium. Then that applause was returned, like old friends recognizing one another across a great distance.

*

I don’t know how to comprehend a hundred thousand deaths, or three hundred and fifty thousand, or whatever obscene numbers are still to come. But I don’t want to stay numbed by the callous comfort of the abstraction. However we come out of this pandemic, we can’t give in to a collective forgetting, an unspoken agreement to ignore what we’ve lost—who we’ve lost—in the rush to return to the status quo. We can acknowledge the numbers without allowing them to blind us to the individual lives within. For me, this means seeking out the stories behind the numbers—obituaries, remembrances, online memorials—just one or two a day, spending a moment with someone I’ve never met. It’s not enough; it’ll never be enough. But I don’t want to take part in the alternative.

Turrell has said he makes spaces that “apprehend light for our perception, and in some ways gather it, or seem to hold it…” But that word, apprehend, has multiple meanings. Apprehend means to catch, but also to recognize something that might have passed unnoticed—a part of the whole we might still see if we choose to look.

*

Toward the end of that game at the Coliseum, the attendance was announced over the PA system: 115,200 fans. The day’s biggest cheer erupted along the overfull bowl of the stadium. Everyone hugged and high-fived. It was hard to say what we had accomplished, why we were so happy. Simply because so many of us were there together? Was that enough to justify our joy?

The sun set, a tangerine bloom sinking below the highest row of seats. There was a moment of crosscurrent illumination, the sun’s shine fading while the banks of artificial lights woke and brightened. The crack of a bat drew our attention back to the field. Another long fly ball. Everyone half stood in collective anticipation, hoping it would have enough height to clear that ridiculous left field net. I rose with the crowd, then turned away from the moment on the field to the one in the stands, the rows of fans behind me, all of those faces alive and watching, apprehended in the light.

Scott O’Connor’s new novel, Zero Zone, will be out from Counterpoint in October. He is also the author of A Perfect Universe: Ten Stories, Half World, and Untouchable, which won the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Award. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and ZYZZYVA, and has been shortlisted for the Sunday Times Story Prize.

July 27, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 19

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“Founded a decade apart, The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books have had a long friendship. NYRB cofounder and longtime editor Robert Silvers was an early managing editor of TPR, and the two magazines have always shared contributors—the respective archives of both are populated by writers who sent their fiction and poetry to TPR, participated in Writers at Work interviews, and published essays, reviews, and opinion pieces in NYRB. Notable joint contributors include James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Ernest Hemingway, Philip Roth, and Zadie Smith. This summer, The Paris Review has teamed up with The New York Review of Books to offer a special subscription bundle—you can get a year of both magazines for one low price, plus complete digital archive access to both websites. To celebrate, this week’s The Art of Distance shares a few pairings—pieces by three writers who have written for both magazines, their voices tuned and modulated for these two different, but related, settings. May these essays and interviews ignite your imagination and stimulate your intellect.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

You’ll find these essays and interviews by Hilton Als, Toni Morrison, and Susan Sontag are unlocked on both sites this week. Here’s a little preview of each piece.

The New York Review of Books published Hilton Als’s essay “Michael,” his uncategorizable homage to Michael Jackson and the phenomena of his fame, in 2009, shortly after Jackson’s death. Als writes, “Unlike Prince, his only rival in the black pop sweepstakes, Jackson couldn’t keep mining himself for material for fear of what it would require of him—a turning inward, which, though arguably not the job of a pop musician, is the job of the artist.”

“Michael” is a sort of how-to on the art of the hybrid essay, neither journalism nor memoir nor psychoanalysis. In his Writers at Work interview, Als offers as clear an aesthetic manifesto as you’ll find on his sense of truth in fiction and fiction in truth:

For a long time, I was so allergic to the empirical in fiction and nonfiction that I didn’t know where to begin. I was allergic to novelists who were certain that what they were making was a novel, and to journalists who believed it was journalism, and I was for sure distrustful of memoirists who said, At three years old, I remember my mother didn’t kiss me, or whatever. I could only describe the truth that I felt, which was that the truth was not empirical, was what I knew in all ways, was coming in from different directions, and was not the whole story.

A similar relationship between interview and essay appears in Toni Morrison’s Art of Fiction interview, in which she observes how “white writers imagine black people … some of them are brilliant at it. Faulkner was brilliant at it. Hemingway did it poorly in places and brilliantly elsewhere,” and a 2001 New York Review essay she wrote on Camara Laye’s The Radiance of the King: “For those who made either the literal or the imaginative voyage, contact with Africa, its penetration, offered thrilling opportunities to experience life in its inchoate, formative state, the consequence of which experience was knowledge—a wisdom that confirmed the benefits of European proprietorship and, more importantly, enabled a self-revelation free of the responsibility of gathering overly much actual intelligence about African cultures.”

In the very first issue of The New York Review of Books, Susan Sontag writes, in an essay on Simone Weil that would later appear in Against Interpretation:

Perhaps there are certain ages which do not need truth as much as they need a deepening of the sense of reality, a widening of the imagination. I, for one, do not doubt that the sane view of the world is the true one. But is that what is always wanted, truth? The need for truth is not constant; no more than is the need for repose. An idea which is a distortion may have a greater intellectual thrust than the truth; it may better serve the needs of the spirit, which vary. The truth is balance, but the opposite of truth, which is unbalance, may not be a lie.

What might Sontag have thought about this passage many years and books later? Her 1995 Writers at Work interview might offer a clue: “Maybe I’m always reluctant to reread anything I wrote more than ten years ago because it would destroy my illusion of endless new beginnings. That’s the most American part of me: I feel that it’s always a new start.”

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

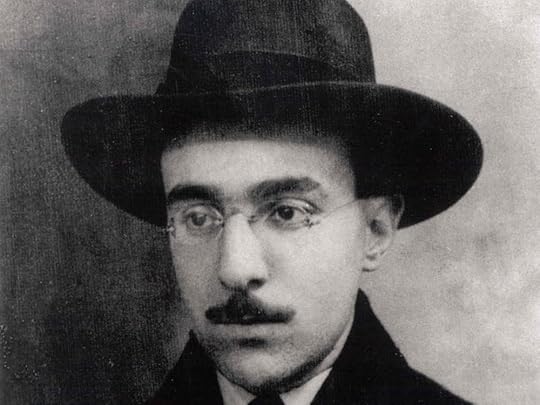

A Little Fellow with a Big Head

Fernando Pessoa. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Fernando Pessoa’s life divides neatly into three periods. In a letter to the British Journal of Astrology dated February 8, 1918, he wrote that there were only two dates he remembered with absolute precision: July 13, 1893, the date of his father’s death from tuberculosis when Pessoa was only five; and December 30, 1895, the day his mother remarried, which meant that, shortly afterward, the family moved to Durban, where his new stepfather had been appointed Portuguese consul. In that same letter, Pessoa mentions a third date, too: August 20, 1905, the day he left South Africa and returned to Lisbon for good.

That first brief period was marked by two losses: the deaths of his father and of a younger brother. And perhaps a third loss, too: that of his beloved Lisbon. During the second period, despite knowing only Portuguese when he arrived in Durban, Pessoa rapidly became fluent in English and in French.

He was clearly not the average student. When asked years later, a fellow pupil described Pessoa as “a little fellow with a big head. He was brilliantly clever but quite mad.” In 1902, just six years after arriving in Durban, he won first prize for an essay on the British historian Thomas Babington Macaulay. Indeed, he appeared to spend all his spare time reading or writing, and had already begun creating the fictional alter egos, or, as he later described them, heteronyms, for which he is now so famous, writing stories and poems under such names as Karl P. Effield, David Merrick, Charles Robert Anon, Horace James Faber, Alexander Search, and more. In their recent book Eu sou uma antologia (I am an anthology), Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari list 136 heteronyms, giving biographies and examples of each fictitious author’s work. In 1928, Pessoa wrote of the heteronyms: “They are beings with a sort-of-life-of-their-own, with feelings I do not have, and opinions I do not accept. While their writings are not mine, they do also happen to be mine.”

The third period of Pessoa’s life began when, at the age of seventeen, he returned alone to Lisbon and never went back to South Africa. He returned ostensibly to attend college. For various reasons, though—among them, ill health and a student strike—he abandoned his studies in 1907 and became a regular visitor to the National Library, where he resumed his regime of voracious reading—philosophy, sociology, history, and in particular, Portuguese literature. He lived initially with his aunts and, later, from 1909 onward, in rented rooms. In 1907, his grandmother left him a small inheritance and in 1909 he used that money to buy a printing press for the publishing house, Empreza Íbis, that he set up a few months later. Empreza Íbis closed in 1910, having published not a single book. From 1912 onward, Pessoa began contributing essays to various journals; from 1915, with the creation of the literary magazine Orpheu, which he cofounded with a group of artists and poets including Almada Negreiros and Mário de Sá-Carneiro, he became part of Lisbon’s literary avant-garde and was involved in various ephemeral literary movements such as Intersectionism and Sensationism. Alongside his day job as a freelance commercial translator between English and French, he also wrote for numerous journals and newspapers and translated Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, short stories by O. Henry, and poems by Edgar Allan Poe, as well as continuing to write voluminously in all genres. Very little of his own poetry or prose was published in his lifetime: just one slender volume of poems in Portuguese, Mensagem (Message), and four chapbooks of English poetry. When Pessoa died in 1935, at the age of forty-seven, he left behind the famous trunks (there are at least two) stuffed with writings—nearly thirty thousand pieces of paper—and only then, thanks to his friends and to the many scholars who have since spent years excavating that archive, did he come to be recognized as the prolific genius he was.

Pessoa lived to write, typing or scribbling on anything that came to hand—scraps of paper, envelopes, leaflets, advertising flyers, the backs of business letters, et cetera. He also wrote in almost every genre—poetry, prose, drama, philosophy, criticism, political theory—as well as developing a deep interest in occultism, theosophy, and astrology. He drew up horoscopes not only for himself and his friends but also for many dead writers and historical figures, among them Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, and Robespierre, as well as for his heteronyms, a term he eventually chose over pseudonym because it more accurately described their stylistic and intellectual independence from him, their creator, and from each other—for he gave them all complex biographies and they all had their own distinctive styles and philosophies. They sometimes interacted, even criticizing or translating each other’s work. Some of Pessoa’s fictitious writers were mere sketches, some wrote in English and French, but his three main poetic heteronyms—Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos—wrote only in Portuguese, and each produced a very solid body of work.

The award-winning translator Margaret Jull Costa lives in England. Read her Art of Translation interview, which appears in the Summer 2020 issue.

From The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro , by Fernando Pessoa, translated from the Portuguese by Patricio Ferrari and Margaret Jull Costa. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

July 24, 2020

Staff Picks: Sex Work, Cigarettes, and Systemic Change

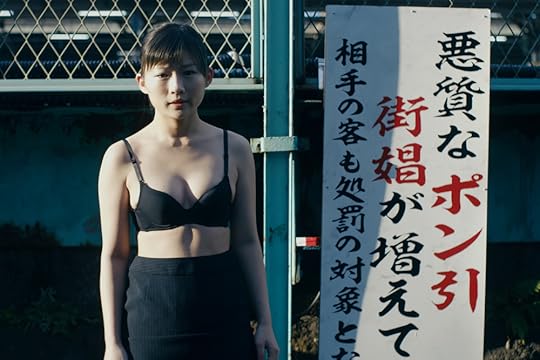

Still from Life: Untitled. © Directors Box.

Life: Untitled, the 2019 directorial debut from Kana Yamada, is a film that bristles. (It is based on Yamada’s stage play.) Focusing on a contemporary Tokyo escort service called Crazy Bunny, it follows Kano, a young woman who initially attempts to become a sex worker as a way to escape what she explains are the constant failures inherent in an ordinary life. She panics during her first appointment and is instead reassigned as an employee on the office side of the service, scheduling client appointments and buying toilet paper. It’s through her eyes that we get to know the other people working there and the indignities and joys that make up their daily lives. Yamada is unflinching in her criticisms of contemporary Japan’s gender dynamics and sexism, and she asks dark questions about what the commodification of sex means for her characters, from the always-smiling Mahiru—who frequently remarks that she’d like to burn the entire city down and eventually reveals a history of sexual trauma—to Hagio, a male employee who sleeps with older customers on the side and holds nothing back in an ugly, judgmental monologue to Kano. The film is currently available to stream online in the U.S. until July 30 as part of the Japan Society’s annual Japan Cuts film festival. —Rhian Sasseen

In the sixties and seventies, New York City experienced a revolution in dance. George Balanchine and Merce Cunningham, who both still cast a long shadow over the art form today, were creating seminal works and new technical styles in ballet and modern, respectively. But the Western dance tradition was built on the marginalization of Black performers and the appropriation of their work, and neither of these men was inclined to make much change. The new aesthetics onstage instead reinforced the near-total exclusion of Black dancers from the mainstream. In the wake of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests, American dance companies are forced to reevaluate their programming and who makes up their ranks. But how will they approach the legacy of these midcentury icons going forward? I’ve been musing on this question ever since a dear friend and Cunningham aficionada shared two recent installments of the podcast Dance and Stuff. In these episodes, the hosts, Reid Bartelme and Jack Ferver, speak with three of the four Black male members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company: Michael Cole, Rashaun Mitchell, and Gus Solomons Jr (the fourth, Ulysses Dove, died in 1996). None of them overlapped in the company, and their conversation is correspondingly rich with shared experiences and differing opinions. Topics move from Cunningham’s failure to cultivate representation, to racial politics in the dance world at large, to touring with the company at the height of the civil rights movement. While a seemingly insurmountable amount of work remains to be done in order to make dance racially equitable, this conversation is a start. In response, the Cunningham Trust featured the podcast at the top of its July newsletter, noting that it is “committed to addressing the company’s problematic past and promoting diversity and inclusion through its current and future programming and resources.” —Elinor Hitt

Elizabeth Acevedo.

There were some long summer afternoons in my childhood when only the crinkle of a library book’s plastic jacket could bring me back to earth. Books took me away from Maryland, and I particularly liked to read those that showed me there was more to do and say as a young woman than I had realized previously. For children of all ages, I wish a long afternoon this summer with Elizabeth Acevedo’s National Book Award–winning The Poet X. Both ambitious and fantastically self-explanatory, Acevedo’s YA novel in verse fills an Amazonian hole in the genre. Acevedo is a poet and began writing and performing poetry as a high school student in New York City. Reading The Poet X, I had the satisfying feeling that Acevedo is not only drawing from her own experience as a young person who found in poetry a language she’d been missing, but also writing to offer what she lacked for young people who are just finding that magic. The novel takes the form of a journal of poems written by a high school junior who finds her power in her own body, her own ideas, and in the performance of the verse she has been writing all along. With growing confidence and support, she gives her work the credence already given to her twin brother’s scientific accomplishments and her mother’s religious commitment. The poems are both satisfyingly complete and contiguous. I slipped through a whole chunk of the sizable hardcover with one arm still in my tote bag the other afternoon. So play yourself—or your young person—Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s rebuke of the patriarchy, and then order The Poet X and hear the message from both New York–born beacons: “I will not stay up late at night waiting for an apology.” But they may stay up to change the world. —Julia Berick

William Carlos Williams famously said: “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.” He might as well have been talking about music, too. But it’s important to keep in mind that Williams said “difficult,” not “impossible”—because the news can be told in abstract narrative strokes, can bear emotional witness. I’m thinking today of the jazz trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire’s powerful new album on the tender spot of every calloused moment. Could there be a better title for this, well, calloused moment, which, like the record, is full of hopeful stirrings, terrified rumblings, and passages of arresting intimacy and sometimes even beauty, calloused as a means of protection against the rampant injustice that each new day in Trump’s America brings? I’m being reductive—about both the moment and the record—but you get the point. Akinmusire is a wildly versatile player, capable of a Wynton Marsalis–like clarity of tone that slides into edgy, uneasy slurring worthy of Lester Bowie. His band has been playing together for a decade, and they’re ever in sync. This music is more guarded than their previous material, more volatile, and seems to be about so much that has happened in recent months—from lockdown and the uprisings following George Floyd’s murder to the current resurgence of the pandemic and the mind-splitting lead-up to the election—though the music was written and recorded well before. It’s another major movement in the soundtrack of now. —Craig Morgan Teicher

If nature takes revenge, the first to fall may well be those poets who reaped it for personal growth, who tortured it with similes and metaphors. Ya Shi will be saved: “This mountain valley is absolutely not a symbol,” he avows, “because I have touched it.” The poems in the astounding Floral Mutter—his first collection in English, translated with remarkable care by Nick Admussen—often start from a place of isolation, a mutual oblivion with the world. “I cannot say that I understand the valley / understand the petal-like, windborne unfolding of her confession,” he writes; later, he asks: “If god did just as he pleased / would the moon still whisper its secrets to wicked people?” Ya Shi, who teaches mathematics at a university, notes, “No matter how swift the bird, it cannot solve this math problem.” The opening sonnets are exquisitely alert to the landscape of Sichuan, to the mist on a lake, “the gem clatter / of spring water.” The land is mutable, strange, bound together through touch and sensation. He writes of lyric poetry as adultery, a poet’s “thirst to see herself in a dream, but without dreaming,” and traces the shared sentiment through laughter, suffering, and endless cigarettes to understanding, then boredom. His vision feels ever new; Ya Shi torches clichés like a divorcé tossing old love letters on the fire. There is also a sinuous melody to this collection that shows Admussen’s poetic hand. He maintains wordplay from the Chinese (“the Way that can waylay”) and even interweaves his own, in a manner that still feels true to Ya Shi. “In life we disturb too much dust. Death ends this reprehensible behavior,” Ya Shi writes, then offers a different view: “Life like light on dust, death like dust in light. / A particolored fantasy.” These sublime poems embody the ecstasy, the oddness of our entanglement with the world. —Chris Littlewood

Ya Shi.

The Baudelarian Horsewoman

In Susanna Forrest’s Écuryères series, she unearths the lost stories of the transgressive horsewomen of turn-of-the-century Paris.

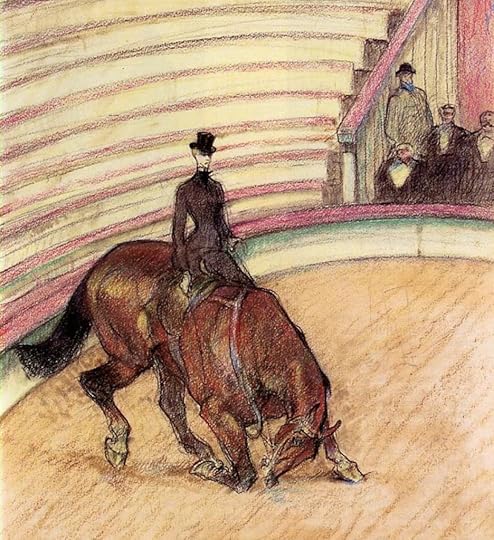

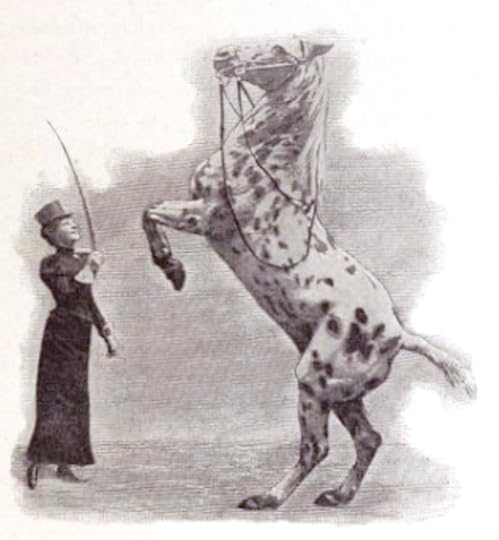

Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, dressage at the circus, 1899

Jenny de Rahden lies on the bed, half raised on an elbow. A gray-haired man who shares her elegant, strong-nosed profile—her father—stands over her, and behind him the room becomes shadow. In the photograph, Jenny lies on a strange counterpane, so great that it conceals the bed itself. Its overspilling edges are frilled, and it is white with large, dark, irregular spots. It has a curly, straggling tail: a horse in the invalid’s bedroom. She is thirty and she is blind, lying on the hide of the Hungarian stallion Csárdás, who carried her when she made her circus debut as a haute école or dressage performer. One day, she writes in her memoir, they’ll wrap Csárdás’s rough coat, the crackling hide that covered his aging, dipping back, around her and place her in her coffin. She hopes it comes soon.

Most of the écuyères or horsewomen of the nineteenth-century circus left no trace of their own thoughts behind. Jenny de Rahden wrote a book. Whether she did it because she needed money or needed to put down her own side of the story after years of being spoken for in the European press—or both—is unknowable but she called it a roman or novel. I can’t tell how much of it is genuine. Jenny lived in an era before fact-checking and though her life was undoubtedly tragic, her style is sometimes melodramatic. “Does life really throw up these bizarreries, of which novelists and playwrights seem to possess the only secret?” she asks at one point. Perhaps calling it a novel gave her freedom to rewrite a messier past and fit it into more conventional romantic feminine tropes, rejecting the saltier stories written about circus horsewomen by male writers of the period. She was, after all, writing in 1902 when the century had barely turned and respectability remained a stifling life vest for women. She’d known its constrictions and buoyancy since birth: Jenny was not circus-born and she had become an artiste to support her father when he bankrupted them by gambling on the stock exchange. As a performer, her reputation as a lady was constantly at risk, not least because she supported not one but two men with her earnings. This dance around sex, money, masculinity, and respectability deformed her whole life—and resulted in a murder in her name.

Le Roman de l’Écuyère tells a familiar tale of a girl from a good family whose mother, as in the best fairy tales, died on hearing her first cries on a stormy night full of omens, and a father who, like Beauty’s, ruined the family with foolish business decisions. The good heroine refused to sell herself in a marriage that would restore the family, and instead bought three magical horses with the last gift her mother left her: an Arabian, a Trakehner, and the spotted Csárdás. Aged just seventeen, she took her father and her faithful aunt Tantante from Breslau (then part of the German Empire, now Wrocław in Poland) to Riga where a circus director and his jealous wife cheated her and stole one of her horses, and a distinguished gentleman at a local newspaper came to her aid like an excellent fairy godmother and ensured her success. On she went on a path through the woods peopled by circus directors who pinched wages, by their wives and daughters who did not want her above them on the bill, and by men who threw roses at Csárdás’s hoofs and rattled the door of her dressing room.

From Riga she went to Moscow, from Moscow to Saint Petersburg, where she was adored. One local aristocrat presented her with a huge golden stirrup as a tribute to her skill and charm. Another Baron asked the circus director, “Is there a way of doing something with the little one?” He was told that she was a good girl with a father and aunt in tow. He stared at her with such intensity that she fell off her horse, and of course he was there to scoop her up and take her home.

Baron Oscar Wladimir de Rahden was the favored nephew of the empress’s lady-in-waiting, a rackety naval officer who slept with his colleague’s wives, ran up debts, and flew into duels at the slightest glancing brush to his honor. In Saint Petersburg, he was running out of favor, his aunt now dead. He liked Jenny. Respectfully, he visited and she found herself falling for this touchy hero. Her father disapproved, and his parents said they would disinherit him if he married an artiste. But they did marry, in Saint Catherine’s catholic church on Nevsky Prospekt. His parents cut him off. The Baron dedicated himself “to literature” and managing his wife’s career.

Baron Oscar Wladimir de Rahden

This Baron was built on a hair trigger, but he was a good man, according to Jenny the memoirist. It’s just that there were so many enemies out there when a woman was paid to perform before all eyes—the horse was no protection. There were men who did not always respect the écuyère’s art or wedding ring. In a portrait circulated by a photographer’s studio, she reclines, her bodice dabbed with stars, a feathered fan behind her head, looking more like an actress than a sober-suited horsewoman.

In Copenhagen, a young Danish lieutenant called Frederick Castenschiold befriended both Jenny and the Baron but fell in love with Jenny. The Baron could not withstand the insult, and a duel was called. Jenny was told the men were going duck hunting. When she arrived in the aftermath, breathless from a performance and a train ride, dazzling circles vibrating before her eyes, she found her Baron bandaged with a Turk’s turban, smoking and laughing with his friends. Castenschiold was the army’s best fencer and her sailor husband preferred pistols—he had taken a saber swipe to the temple from the Dane. The matter resolved, they proceeded to the actual duck hunt. The Baron gave Castenschiold a photograph of Jenny. Castenschiold was reprimanded in person by King Christian for dueling over a circus performer.

*

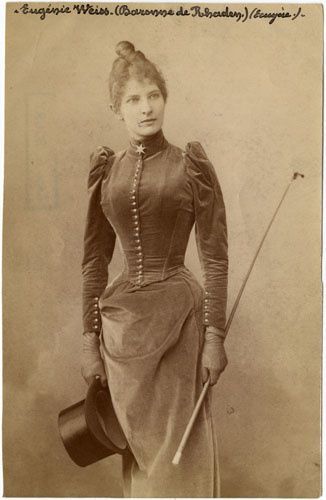

Jenny de Rahden and her feathered fan

When Jenny first appeared at the Nouveau Cirque in Paris in October 1890, the critic and dramatist Jules Lemaître noted her conformation and that of Csárdás: “Very thin and very supple: a black thread; an elegant, dry little head, pale blonde hair tucked up under a top hat, with long kiss curls that cover half her cheeks and reach to the bottom of her ears, giving her pointy face a bizarre and disturbing air. She rides an equally bizarre big horse, pied as you’ve never seen before, riddled with ugly spots like ulcers, and which seems to be made of damp cardboard. She’s a Baudelairian horsewoman.”

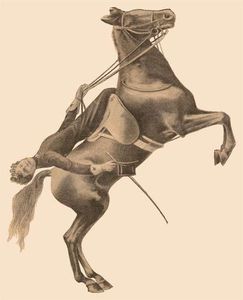

Lemaître could not look away. “I don’t know if what she does is difficult, but it’s very arresting. At one point, the horse rears straight up, and the slender horsewoman bends right over backwards and dangles her head low … She has a bizarre fashion of saluting too, a composite of a feminine curtsey and a masculine salute. Go see her. In short, she’s very fin de siècle. I don’t know exactly what that means, but that’s what she is.”

Jenny de Rahden’s signature trick

Other commentators were keen to relate the story of the duel and the dramatic husband. The Baron wasn’t, as one writer later put it, the only “horse eating at the baroness’ manger.” There was also her father, David. Jenny paid him off when she married and sent him home. Then she called him back.

In Paris, the couple seldom went out. The Baron was always present, even at the circus—no one could talk to Jenny without him there. She was hotly applauded every night after her “brilliant” debut. From Paris, they went on to Italy, and in Milan they lost Tantante to blood poisoning, leaving just Jenny, her father and husband. Jenny earned the cash as the Baron wrote the odd article about Siberia and her father lagged along.

In Turin in May, the Baron managed two duels in one day after a count sent Jenny love letters “in the language of Dante” and, peeved that she did not respond, brought friends to her next performance and blew a whistle throughout. The Baron slapped him; honor was demanded. The Baron slashed the count’s neck with a saber (the count survived), refreshed himself with some marsala, then tackled the count’s friend, the best fencer in Italy, who caught the Baron’s face and then, after “halt” was called, stabbed the Baron in the shoulder. The Baron throttled him and knocked him over. Nobody’s honor was satisfied, but the duels were at least over.

At Asti, another man threw white roses into the ring as Jenny performed, and her horse, startled, leapt into the audience and landed on an old lady, who had to be paid off from Jenny’s meager buffer against destitution. In Lisbon, there was a man who was sure he could perform Jenny’s best trick. He came to the circus with his wife and son, strapped a Mexican saddle to his horse so he would stick, and up he and his horse went in a rear and didn’t stop till they were both on their backs and his leg was broken. So then all of Lisbon was angry that their best “sportsman” had been injured by a woman’s circus trick.

Madrid. Seville. On an afternoon’s outing, Jenny seized a man’s revolver and shot a runaway fighting bull that had disemboweled two mules and turned on her carriage. Malaga. Barcelona. Here, as Jenny joined the Circus Allegria, the Danish lieutenant Castenschiold reappeared like a bad penny, trailing tales of Monte Carlo debts and army discharges. He had been, he said, in Egypt and fighting rebels in the Sudan. He had no money and would like to work in a circus. When the Baron questioned him, he waved a knife at the Russian. The Baron turned his back, and the next day word in the circus said that Castenschiold had left for the Americas. He had not.

At Clermont-Ferrand, in central France, it became clear that Castenschiold was following them. He knew where Jenny kept her horses and lingered nearby. The Baron visited the police, who told him not to worry, even when he said he would defend his wife with his revolver.

August 23, 1890. Jenny was standing backstage beside her horse before her performance, the Baron at her shoulder, when Castenschiold materialized before them in the corridor that ran around the circus arena. The Baron, seeking to avoid what was barreling toward the three of them, turned and walked away around the curve of the corridor. Castenschiold spun on his heels and ran in the other direction, hurrying to meet him. They clashed. The Dane raised his stick and struck the Russian. The Russian drew his revolver and his fingers convulsed on the trigger. Jenny, buttoning her gloves, heard the two shots. Then two more.

She found the Dane bleeding on the floor, asking for someone to bring him two photographs—of his mother and of Jenny. The Baron walked past Jenny without seeing her. “Tell my wife I did my duty,” said his mustache, as he asked for an absinthe at the circus bar. The police took him into custody. Castenschiold died twenty hours later. In his rooms, they found a portrait of Jenny and a box containing unsigned letters from a woman, and more photographs of the Baronne de Rahden. In accordance with Castenschiold’s dying wish, this box was burned.

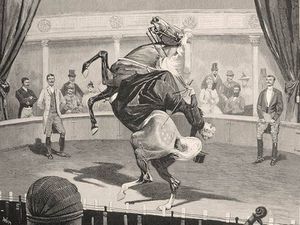

Now every circus director in Europe wanted Jenny, and her Baron, a tiger pacing in his jail cell, waiting for his trial, urged her not to lose her career. Those horses—equine and human—weren’t going to feed themselves. So she took on the best offer although it took her to Paris, which had caught scent of her scandals, and not a circus but a theater: the Folies Bergères.

Eight square meters is all the Folies Bergères gave her to perform on. They nailed coconut matting over the sloping boards and it shifted under the horses’ feet, making them uneasy. No barrier was mounted at the edge of the stage, just the flaring footlight reflectors, and at first the orchestra refused to perform with her, picturing a half ton of Csárdás smashing violins and skulls. When they saw her rehearse, they were won over, because Jenny and her horses were a miracle, a cavalcade on a pinhead.

Let me tell you about the duel Jenny undertook every night, as the men twirled flowers and pistols in the background:

She entered on a horse who bounded to the edge of the stage, his forehoofs thudding just above the heads of the orchestra as they played. Like dancers, she and and the horse stepped to the left and then to the right, the horse’s rigid frame flexing and his legs crisscrossing. They cantered around that eight-meter square space, then dashed across the ring, peeling back in tighter circles, once in each direction. Then she made him skip before they completed pirouettes and left the stage in a high-kneed Spanish walk.

She was back then on another horse, Da Capo, at a gallop, rucking up the matting as they halted. Across the stage and then another pirouette, and then with her hands and her stick she made Da Capo rear and then bow. There were four fences set in a square, and they leapt in and out of the box always, always in that eight … meter … square. The horse stopped dead in the center for a beat, then jumped out from a standstill. They ended with her most dangerous move: Da Capo walking on his hind legs like a bear, and Jenny bent back against the resistance of her corset and hung by her knee from the pommel of the sidesaddle, her head resting at the top of his tail. The first night, Da Capo toppled over backward onto her, pinning her for a second before she could pull herself clear. Miraculously she was only bruised. The barrel of the pistol had spun to an empty chamber.

She returned for her applause on foot and as she raised her top hat Da Capo careered on with neither saddle not bridle and took his own bow. He lay down at her feet and she sat on him. The audience was in raptures; the fee was 1,500 francs a month. Ten days after Castenchiold’s death, a critic wrote that he had seen her flirting with young men backstage.

*

The trial gives me a chance to break away from the strange, rhapsodic darkness of Jenny’s roman. Here, for once, there are other witnesses. The Paris papers sent their best men to cover the Baron’s trial, and when Jenny was fenced into another cramped space—the witness box—another story emerged in the questions the lawyers put to Jenny and her father. That tale splits away from the spare account of proceedings that Jenny the author later gave.

Baronne Jenny de Rahden (born Eugenie Weiss)

In this story, the Baron was a drunk who sank “cup after cup” of absinthe and cognac and treated his wife “like a filthy cow” and his father-in-law “like an old dog” (“He only drank when he got jealous!” protested Jenny in the witness box.) His eyes were small, his face “extremely hard.” The groom said he took out his drunken temper on the horses. In this story, Jenny brought her father back to live with them as protection, and her father confided in a maid that he would prefer rich, young Castenschiold as a son-in-law. In this story, Jenny might, just might, have written those burned letters to the young Dane and told him how to follow them to Clermont-Ferrand. In this story, Castenschiold was visited by a tall, slender woman in a white veil and heliotrope dress that his landlady identified as the Baronne de Rahden.

Jenny stood with her teeth gritted, refusing to answer most of the questions posed to her:

“You perhaps encouraged Castenschiold a little to pursue you?”

She lowers her head without saying yes or no.

“The evening before the murder your husband hit you and your father.”

“I don’t remember.”

The Baron was unmoved. When the jury withdrew, the reporters saw her go to him, “with the moist eyes of a beaten dog that wants to be beaten again,” and say a few words in German to her grim, furious husband. He smiled.

The judge told him off for letting his wife risk her life in the circus. One reporter suggested that he was defending his meal ticket as much as his wife’s honor. But the Baron was deemed not guilty—this was self defense, not premeditated murder—and finally, his composure cracked and he cried. The women in the courtroom swooned at the romance of it. Jenny nearly collapsed; she had leapt out of the square of fences once again, but where had she landed? One reporter saw the Baron as he went to collect Jenny after the trial: “They remained silent for a moment; he always glacial; her frozen, cheeks scarlet, eyes shining.” As he took a step toward her, she backed up in fear and ran away weeping.

Who is being melodramatic here? Jenny, the landlady, or the court reporter? Jenny sums up the court case in a brief chapter of her memoir and does not mention the heliotrope dress or her own interrogation. She is a faithful, distressed wife willing the jury to set her husband free. One journalist notes that the Baron was the “defender of her glory and her virtue,” and “she loved him in that role.”

That evening the couple—and her father—were on the train back to Paris so she could perform. Their life on the road continued, but the wheels were wobbling on their axles. Jenny performed as Leo in Pirates de la Savane —the role made famous by Adah Isaacs Menken thirty years earlier and for which Sarah l’Africaine was once touted—even though it meant swapping her respectable habit, the one buttoned to the neck, in favor of something scanty, and being tied to a galloping horse’s back. “She’s not scared of anything, La Rahden,” said someone leaving the theater. In her memoir, she doesn’t mention that the Baron tried to become a circus performer himself during this period—he was billed as a sharpshooter trained on the Mongolian steppe. He challenged Buffalo Bill Cody to a shoot off for his Paris debut. Cody ignored him, though the Baron did perform in the provinces instead. He made some money in a shooting match and they took it to a casino. The next year, Jenny pivoted to acting on the stage in Hamburg. This also went unmentioned in her memoirs.

In Jenny’s version, at this point, a deus ex machina of sorts appeared in Berlin. A Russian officer approached the Baron and said he would endorse his return to the Russian Navy, but only if La Baronne retired from the stage. A Russian officer could not be supported by an artiste no matter how meager his new salary. The Baron wished it; Jenny held back.

“I had my will, I had one goal in mind, that I was fixed on achieving. And I would not take a step away from the path that would lead me to this goal: independence,” Jenny wrote—shades of the teenage girl who had refused to marry her family out of trouble. But she would never say in her memoir that she could not rely on the dueling, gambling, tempestuous man she married to support her and her father for more than a month at a time, and that there was much, too, in the plaudits, in being the only one who could do that dangerous trick. The “little one” in the top hat on the expensive Hungarian horse from Maas. The horseshoe broach at her throat; the golden stirrups. But the Baron, while sympathetic, wanted to finally man up and rescue her from the circus. They made preparations to sell two of Jenny’s horses.

But what about Csárdás? He was blind. The flare of the footlights had permanently dazzled his great brown eyes. He still performed with Jenny, his trust in her and hers in him absolute, but on the Baron’s wages there was no money to feed the actual horse that had earned his keep for years. Jenny’s heart was wrung: “Ah! It’s cruel and hard to be obliged to separate oneself from a being you hold to heart … My life was intimately tied to that of this poor animal! And I must quit him now, as I would quit my past existence, my success and my career as an artiste.”

*

They did not return to Russia, in the end. Csárdás did not die. The Baron did—felled by a lung infection. Jenny sat and watched as the life rattled out of him and he turned to her and said: Ne tombe pas avec le cheval.

“Don’t fall with the horse.” She was, she wrote, now dead, too, as far as she was concerned. Her “good and loving” husband, so “wrongly judged” by many, was buried and her distress was so complete that the doctors tried to stop her riding. She was consumed with anxiety and headaches. “The life of an écuyère is neither a pleasure nor a joke,” she wrote, her health slowly breaking and her nerve faltering. But there was no one else to support her and her father if she wasn’t in the ring: the horses were not sold; Csárdás lived on. She was legged back into her saddle and on tour across Europe, losing nights to fever and fear. Then one morning, she opened her eyes and was blind. Her screams woke the hotel.

The doctors said that a surge of blood had ripped her retina and severed the optic nerve.

By now she was dogged, an arrow angled at fate; when that night’s circus director suggested that she could still perform, reading aloud the cost of lost receipts to her, she began to think that with dear, blind Csárdás she could trim their routine to satisfy the people who had paid to see La Baronne. Csárdás had never betrayed her, but she signed off fatalistically: “If this adventurous attempt fails, if God disapproves of my act, let his will be done! Better to die under the public eye in the course of my profession than remain condemned to a desolate life, a cursed existence. Death would be a deliverance.” The pistol was cocked; the duel with death was called.

Jenny de Rahden and Csárdás

In the wings, she heard the crowds but her focus was only on Csárdás as he moved under her. A wild energy surged through her in the blackness, and Csárdás felt it—he didn’t like it. The stallion froze. Jenny cued him. He began to resist. Csárdás had felt the sump at their feet, the deliverance Jenny sought, and now he backed away, “as if from an abyss.” And Jenny, for the first time, raised her whip. When it struck the stallion he reared up. He touched down and then leapt forward, and “I had the confused sensation that we were tumbling into the void, into a bottomless precipice, into the immeasurable nothing.” As she whiplashed off the saddle, Jenny struck a column at the edge of the stage and the blackness was absolute. It lasted for seven days.

Jenny dictated this roman from the bed in the photograph where she lies on Csárdás. She is glad, she writes, that her husband did not live to see her in this dingy room in Boulogne, this void with floral curtains. Csárdás is still her companion, she adds, and she has a letter from Castenschiold’s mother offering her deepest sympathy. What grace, what pure and grand consolation. She was not, she says, fitted with the lightness of heart required for the life of an artiste; her education and temperament forbade it. The golden age of the circus horsewoman was over by the early 1900s just as the era of the horse peaked and began a long, slow fade that filled the streets with automobiles. In Jenny’s future lay a brief, failed career as a singer, and when she died in 1921, the Paris papers remembered seeing her in her retirement, being steered around the Bois de Boulogne in a carriage, ignored by all the current belles.

I hope they wrapped her in Csárdás at the end, and let him carry her over to the other side.

Susanna Forrest is the author of The Age of the Horse: An Equine Journey Through Human History and If Wishes Were Horses. She’s currently working on a third book and a series of essays about circus horsewomen in nineteenth-century Paris.

July 23, 2020

The Edge of the Map

Olaus Magnus, Carta marina (detail), 1539. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the collections of Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey, there’s a round ceramic disk, about the size and shape of a cobblestone, with the barest image of a face on it. Two eyes in a mushroom-shaped head, a mouth opened in a howl or scream of some kind. Radiocarbon dating puts its age at about seven hundred years old, which would make it one of the earliest known images of the Jersey Devil.

The Lenape knew it as Mësingw, a spirit being vital to preserving the balance of the forest. Mësingw (“Living Solid Face,” “Masked Being,” or “Keeper of the Game”), according to Herbert C. Kraft, who devoted his life to researching and documenting Lenape culture, was of prime importance to the Lenape. Of all the manetuwàk (spirit beings whose job it was to care for and maintain the world that Kishelëmukòng had created), Mësingw had one of the most important jobs: looking after the animals of the forest and ensuring their health and safety. Mësingw could sometimes be seen riding through the forest on a large buck, covered in long, black hair from head to toe like a bear. The right side of his large, round face was colored bright red, the left side colored black.

Alternately revered and feared, he ensured the prosperity and prevalence of vital game for the people but could also, if displeased, ruin a hunter’s luck, or “break his speech,” causing him to stammer uncontrollably, or scare him to death. Mësingw, for the Lenape, kept the forest in balance, mediating between humanity and animal life. When white settlers came to the land where the Lenape lived, they saw images and masks of a strange creature who, they were told, lived in the forbidding wilds of the Pine Barrens, the edge of the settled world. As they heard tales of Mësingw and saw the masks and effigies of the god, they saw him not as a figure of order but of terror.

Whatever prowled the foreboding Pine Barrens, early settlers thought, it was not Christian. And in the early Puritan imagination, fevered with thoughts of Satan and divine punishment, Mësingw merged with another local legend: the Leeds Devil. Stories tell of a “Mother Leeds,” who was in labor with her thirteenth child when she uttered, out of exasperation or pain, “Let this one be a devil!” resulting in a monstrous birth, the hideous creature fleeing the house as soon as it was birthed.

“Mother Leeds makes no attempt to love or nurture her offspring, and, rather than mourn his loss, is relieved to be rid of him,” Frank Esposito and Brian J. Regal write in their study of the Jersey Devil. “It is the female—a self-centered, uncaring, unloving mother—who bears the brunt of the blame.” This story, Regal and Esposito note, has some basis in fact: Anne Hutchinson, the Puritan leader who was expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1637, later gave birth to a “disturbing mass that bore little resemblance to a child” (what was likely a molar pregnancy, in which a nonviable fertilized egg implants in the womb, resulting in a malformed mass of cells). Another apostate, Mary Dyer (who was later executed for converting to Quakerism), likewise gave birth to a deformed child who was taken as proof of her heresy. Mother Leeds “becomes a scapegoat for various fears about witches, non-Christians, and women in general,” Esposito and Regal explain. “She is an outsider, rural, uneducated, and prone to supernatural and superstitious beliefs and who has sex with the devil.”

The Devil itself, meanwhile, likely took its name from Daniel Leeds, a well-respected and influential early New Jersey writer, but one who increasingly flirted with unorthodox ideas. He brought English astrology with him to America, publishing astrological charts in his popular almanacs. So the Leeds Devil’s emergence as early American folklore came at a time when there was a fair amount of anxiety over colonials living outside of the carefully controlled Puritan power structure.

The early years for European settlers in America were filled with strife, everything from unexpected crop failures, conflict with the indigenous populations, and a general inability to adapt to new conditions and climate so far from England and Europe. As with many communities under siege from external forces, the early colonists responded by enforcing a strict religious and governmental hierarchy; dissent could simply not be tolerated, lest the whole colony fail.

The Leeds Devil prowled at the edges of a tight-knit community, a warning to all who might step out of line. Cryptids have since come to occupy these places, almost exclusively: marginal locations on the edge of the known world. The dense redwood forests of northern California; the deep, forbidding lochs of Scotland; the impassable Himalayan peaks; or the deserts along the border of the United States and Mexico, where the goat-sucking cryptid the chupacabra is often seen. It was here that one was caught in 2007 by a local rancher. (“I’m not going to tell you that’s not a chupacabra,” the veterinarian Travis Schaar, who examined the creature, told the Associated Press. “I just think in my opinion a chupacabra is a dog.”)

Anthropologists use the word liminal, from the Latin limins, or threshold, to describe those moments and places of transition, places where the rules are fuzzy, the laws suspended. These are the frontiers between here and there, between the “savage” and the “civilized.” The sunken continents of Atlantis and Lemuria dreamed up by Ignatius Donnelly and Helena Blavatsky were liminal places, border regions halfway between the known world and a mystical realm beyond our ken. The mysterious denizens of such places have gradually been replaced by Yeti and Nessie, whose purpose remains the same: to patrol the edges of the map.

*

Monsters have always patrolled the margins of the map. In distant lands lived barbarians, cannibals, and wild, unimaginable creatures. Travelers’ narratives, such as Sir John Mandeville’s mid-fourteenth-century chronicle, brought back stories of the horrific and marvelous from far-off lands. Mandeville’s fictional travelogue reported of distant islands where one could find “ugly folk without heads, who have eyes in each shoulder; their mouths are round, like a horseshoe, in the middle of their chest. In yet another part there are headless men whose eyes and mouths are on their backs … In another isle there are people whose ears are so big that they hang down to their knees.” Such wonders populated maps of the period; Roman cartographers had sometimes used the phrase HIC SVNT LEONES—“Here be lions”—to denote unexplored incognita; medieval cartographers updated this with fanciful images of sea serpents, kraken, and dragons.

But these distant races of dog-headed men and basilisks were not solely about cultural superiority and jingoism. They also inspired wonder—a sense of the magic and the mysterious in the far and distant world. Such creatures were able to evoke this feeling of wonder precisely because they lived on the edges of the known world. Medievalist Karl Steel notes that medieval natural historians understood wonders primarily in terms of where they stood in relationship to civilization: “In the bestiaries and medieval natural history tradition in general, unicorns, dragons, and other wonders are not associated with a particular place or habitat,” he says. “Medieval wonders live at the edge of the conceptual map: the further you get from home, the weirder things get.” In the travels of Sir John Mandeville, wonders don’t begin to appear until after he’s passed through Jerusalem; the routes between England and the Holy Land were well documented. But after that, the landscape turns wondrous. By their very strangeness, monsters determined the boundaries of the regular world.

Such tales were less about accuracy and more about creating an organized world of the civilized and uncivilized—marked, first and foremost, by strange monsters. Credibility didn’t matter to an audience who themselves were likely never to see such places, and besides, people who’d never ventured this far were in no position to fact-check a traveler’s assertions. A sense of wonder, divorced from the obligations of veracity, was precisely the point.

Some of these distant species were gradually assimilated into a Linnaean taxonomy as they were definitively collected, observed, and cataloged (the giant squid, for example, or the panda bear). Others, though, simply vanished, receding into the mists of myth. Such creatures could exist only so long as there were unknown corners of the map; as the explorers fanned out over the seas and mountains and it became a small world after all, there were fewer regions that could plausibly be inhabited by monsters.

The birth of cryptids—of strange creatures that exist beyond the reach of civilized humanity—is in part a response to this end of wonders. For the most part, cryptozoologists are re-creating those species which are not only beyond the grasp of understanding but whose realm is specifically in the margins, where they are free to transcend scientific classification.

Cryptids require physical spaces that can’t be fully reached, fully documented, fully inhabited by civilized people. They require the borders between places, the edge lands. Cryptids are nothing without their habitat, and their habitat was, at least for a time, destroyed by colonialism and capitalism throughout the nineteenth century, as the “blank spaces” on the map were filled in, and as cultural differences were more and more assimilated through trade and tourism.