The Paris Review's Blog, page 158

July 8, 2020

Where Does the Sky End?

Nina MacLaughlin’s six-part series on the sky will run every Wednesday for the next several weeks.

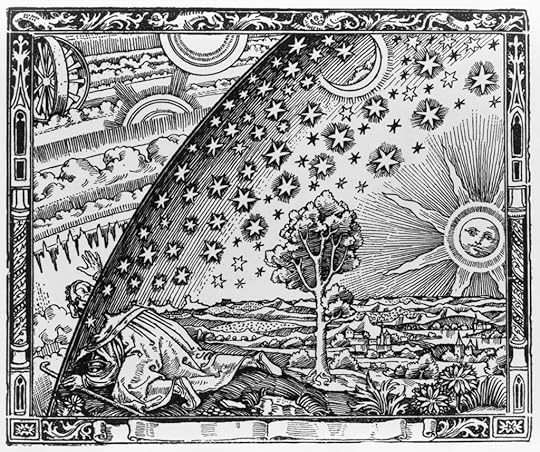

The Flammarion engraving, unknown artist. First appeared in Camille Flammarion’s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888)

Rare right now, the airplanes. Before, the planes taking off from Logan tracked a path I saw from my pillow in bed, high lights wing-blinking in the night sky in ascent from Boston. Not anymore. Not for now. Before February of this year, the planes blurred into the texture of the everyday, cigarette wisps of contrails, sky-height roar, as regular as the honking geese, which sometimes I notice and sometimes disappear into the familiar static of any afternoon, by the river. Now, I see an airplane and think: Who’s going anywhere? And why? Then I remind myself it could be cargo, small packages, love letters. To see an airplane now is to be aware of both presence and lack: Oh, look, there one is; oh, gosh, I notice because they’ve been mostly gone. And then comes the press of knowing, the weight across the chest, the reminder why.

The gravity of knowing. “The more you know the more you think,” Anne Carson said recently. And the more you think the more you question. What are we supposed to know? What’s better sensed than understood? What happens when the gravity of knowing threatens to tear apart and turn upside down the way the world has existed for you? Do you run away?

I pursued some knowing recently, and regretted it. The amount of feet in a mile is a number that’s never stuck with me. I asked a distance calculator to convert 35,000 feet—classic airplane cruising altitude—into miles. When it delivered the answer—6.6287879 miles—I thought, I’ve made a mistake, or it has. This cannot be. Six point six miles up into the sky?

If I were to take a 35,000 foot walk, I could leave my apartment, head more or less due south, and in a little over two hours, reach the Franklin Park Zoo. Two hours on foot and I could look a tiger in the eye. Seems like dreaming. (It’s not an option now: the animals are all locked in.) But six point six miles up? It is a fact I wish I could un-know. It disrupts my comfort. Am I initiating some of you into this distress? If I suffer in knowing, does it mean you ought to as well? You can forget I said anything.

When you dream of flying, do you have wings? To take flight in dreams is an experience of uplift, of thrust, an unburdening of weight and an entering into the voluptuousness, as Gaston Bachelard calls it, of the soar. We’re bathed in the pleasure of defying the pinning laws and drinking in new views. Freedom! Lift! A human impulse, a shared experience in our dream life, to move as seagulls, petals on wind, superheroes, gods. “Dreamtime,” writes poet Nathaniel Mackey, “is a way of enduring reality… It is also a way of challenging reality, a sense in which to dream is not to dream but to replace waking with realization, an ongoing process of testing or contesting reality, subjecting it to change or a demand for change.” How high can we go? How free can we get?

When I fly in my dreams, I don’t have wings. And usually I’m not lifting off the earth, but falling first, and instead of crashing to my bone-crushed death, I sweep above the surface. The relief! The thrill of not ending, of avoiding the crash, of there being more to see, more to know. The relief of an altered arrival. As Mackey writes:

It was Arrival

…………………………………………………we were

in, suddenly so with a capital A, all

…………………………………………………we’d

always wanted it to be, been told it would

…be… Falling from the sky, an immaculate

…………………………………………………dust

…attending

sleep

Does an ultimate landing place exist? Or are we always arriving, always Arriving, falling, faltering, flying, to land once more, then fall again? Our dreams offer glimpses of what could be, visions that can change what we know and how we exist in the waking world where we live. We fall asleep, sink into our dreams, and rise, ascend, Arrive, wake up.

Poet Éireann Lorsung writes also of arrival:

We are flying

machines we cannot land.

One night, I dream

of loving you; another, of falling

without ever coming to earth—the same dream.

Falling without end, machines we cannot land, here we are, immaculate dust, and we are all hurtling—toward what?

Last year, scientists captured the first photograph of a black hole, “a monster the size of our solar system,” according to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette, “that gobbles up everything.” Black holes are “the epitome of what we don’t understand,” said a Harvard physics professor named Andrew Strominger. “And it’s very exciting to see something that you don’t understand.” It is exciting. It lifts us right off the earth. One person I know refused to look at the photograph, because he felt to lay eyes on it would bring curse. Some things, he said, should remain a mystery. Another friend admitted recently that seeing women in masks was turning him on. I wondered, Something akin to the Victorian titillation of a revealed ankle? Octavio Paz writes of “the rotten masks that divide one man / from another, one man from himself” and how when they crumble “we glimpse / the unity that we lost … the forgotten astonishment of being alive.”

The physicist Strominger admits that he wept when he saw the photograph of the black hole, and then he asked, “What can we learn from this?” What’s there to be found? How far can we go? He and the team looked at the rings that surrounded it. “Their individual brightness, thickness, and shape depend on the monster’s manipulation of its surrounding geography.” And here, the article notes, is “where things get stranger: A black hole hoards images of the past.” Bits of light that escape the ring “carry a reflection of what the universe looked like when they entered the black hole’s pull.” Another physics professor, Joseph Pellegrino, describes it like watching “a movie, so to speak, of the history of the visible universe.”

I do not understand. I do not understand. I kneel down and raise my hands to the sky in non-understanding. I hear phrases like “the anticenter of the galaxy” and my brain lights on fire with the excitement of non-understanding. In the article on black holes: the word monster, the word hoard, the word inferno, the words gobbles up. I understand these words, and the imaginative flight required to make sense—there’s no making sense!—of a light-eating, gravity-bending nothing. The language of dream is used, of children’s stories, of comic books, of myth, of the poetry that grants us closer access to our non-understanding and the awe of the incomprehensible. “We take part in imaginary ascension because of a vital need, a vital conquest as it were, of the void,” writes Bachelard. “Our whole being is now involved in the dialectics of abyss and heights. The abyss is a monster, a tiger, jaws open, intent on its prey.”

We rise up, take mental flight, we lift ourselves six point six miles into the sky, and higher, and higher, to conquer the void. But as we rise to conquer, guess what? We’re also moving toward it. See it as threat, as horror, see the abyss as a force that will split you, rip you apart, eat all your thoughts and evaporate your bones. It is, and it will. It’s up to us, how close to get. Up to us, how much we want to know. What does the tiger’s breath smell like? What’s it feel like to stand on a doughnut of light peering in to the nothing we can’t escape? The physicists at Harvard call the center of the black hole “the prize.”

There is always farther to go. Even if we reach the end of the universe, there is still an after-that. We’ll keep ascending in machines we can’t land, moving toward the moment when the masks crumble and we glimpse the unity we thought we lost. It’s here to be found. Know more, think more, ask more, listen. Rise, fall, fall again, fall better. With each inhalation, we take the sky into our lungs. We exhale the dropletted matter of life and death. Haven’t you become more aware of your breath? Felt it compromised by the soft cloth in front of your face? Inhale now. Take a big skyful into your lungs. What luck. Here it is: the astonishment of being alive. And the responsibility. What can we learn? What can we do? What’s here to be found? What’s the prize at the center? We don’t know. The experts don’t know. No one knows. No one knows what happens next. “Sweet is it, sweet is it / To sleep in the coolness / Of snug unawareness,” writes Gwendolyn Brooks. We’ve been locked inside like the tigers, listening for the roar of the planes, wondering about the earth that we’ll return to, or when we will, or if. Through our un-knowing, we re-emerge into the world, out of the sweetness of sleep, stumbling—and soaring—out of our dreams, and taking them with us, not just to endure reality, but to challenge it. To demand that it change in the ongoing Arrival of our waking.

Read earlier installments of Sky Gazing.

Read Nina MacLaughlin’s series on Summer Solstice, Dawn, and November.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice.

July 7, 2020

Redux: This Satisfied Procession

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Joan Didion at the 2008 Brooklyn Book Festival. Photo: David Shankbone. CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...).

This week at The Paris Review, we’re announcing another year of the best deal in town: our summer subscription offer with The New York Review of Books. For only $99, you’ll receive yearlong subscriptions and complete archive access to both magazines—a 38% savings.

To celebrate, we’re unlocking pieces from the archives of both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books. Read on for Joan Didion’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with her essay “California Notes”; Zadie Smith’s short story “Miss Adele amidst the Corsets,” paired with her talk “On Optimism and Despair”; and T. S. Eliot’s Art of Poetry interview, paired with two uncollected poems.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read their entire archives? And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Joan Didion, The Art of Fiction No. 71

The Paris Review, issue no. 74 (Fall–Winter 1978)

Sometimes I’ll be fifty, sixty pages into something and I’ll still be calling a character “X.” I don’t have a very clear idea of who the characters are until they start talking. Then I start to love them. By the time I finish the book, I love them so much that I want to stay with them. I don’t want to leave them ever.

California Notes

By Joan Didion

The New York Review of Books, volume 63, no. 9 (May 26, 2016)

At the center of this story there is a terrible secret, a kernel of cyanide, and the secret is that the story doesn’t matter, doesn’t make any difference, doesn’t figure. The snow still falls in the Sierra. The Pacific still trembles in its bowl. The great tectonic plates strain against each other while we sleep and wake. Rattlers in the dry grass. Sharks beneath the Golden Gate. In the South they are convinced that they have bloodied their place with history. In the West we do not believe that anything we do can bloody the land, or change it, or touch it.

Zadie Smith at the 2012 Paris Review Spring Revel. Photo: Patrick McMullan.

Miss Adele amidst the Corsets

By Zadie Smith

The Paris Review, issue no. 208 (Spring 2014)

And who was left, anyway, to get dramatic about? The beloved was gone, and so were all the people she had used, over the years, as substitutes for the beloved. Every kid who’d ever called her gorgeous had already moved to Brooklyn, Jersey, Fire Island, Provincetown, San Francisco, or the grave. This simplified matters.

On Optimism and Despair

By Zadie Smith

The New York Review of Books, volume 63, no. 20 (December 22, 2016)

But neither do I believe in time travel. I believe in human limitation, not out of any sense of fatalism but out of a learned caution, gleaned from both recent and distant history. We will never be perfect: that is our limitation. But we can have, and have had, moments in which we can take genuine pride.

Sketch by D. Cammell, 1959.

T. S. Eliot, The Art of Poetry No. 1

The Paris Review, issue no. 21 (Spring–Summer 1959)

There is all the difference in the world between writing a play for an audience and writing a poem, in which you’re writing primarily for yourself—although obviously you wouldn’t be satisfied if the poem didn’t mean something to other people afterward.

Two Uncollected Poems

By T. S. Eliot

The New York Review of Books, volume 63, no. 1 (January 14, 2016)

Sunday: this satisfied procession

Of definite Sunday faces;

Bonnets, silk hats, and conscious graces

In repetition that displaces

Your mental self-possession

By this unwarranted digression …

If you like what you read, subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for just $99.

How Neapolitan Cuisine Took Over the World

Edward White’s monthly column, “Off Menu,” serves up lesser-told stories of chefs cooking in interesting times.

When a devastating cholera pandemic reached Italy in 1884, the disease took its heaviest toll on the sharp-edged, unpolished jewel of Naples. The authorities’ response was disastrous, and as panic and anger rose, a conspiracy theory circulated that the suffering was an orchestrated attack on the city’s poor. Physicians and public health officials were attacked in the street; a popular rumor had it that doctors received twenty lire for each person they bumped off, and that some were greedily chucking patients who were still alive onto funeral wagons. One man was arrested for inciting rebellion when he spread the notion that tomatoes, a symbol of Neapolitan peasant identity and a staple nourishment, were being laced with poison.

The discord caused alarm in the government. The Risorgimento—the movement behind the creation of a single, unified Italian nation in 1861—had promised a new era of prosperity and progress for all. Events in Naples made a mockery of that. Italy’s King Umberto I became a passionate advocate of a radical transformation of Naples that would improve the health of the city, and tie Naples closer than ever to the Italian nation. Corruption and chaotic administration kiboshed the plans, but the royal desire to celebrate the Italian-ness of Naples remained. When Umberto and his wife, Queen Margherita, visited the city in 1899, the queen, bored of overly complex French food, supposedly asked for some real food, a true taste of Naples. A local chef served her a pizza in the colors of the Italian flag—the red of tomato sauce, the white of mozzarella cheese, the green of fresh basil—which Margherita loved so much that it’s been named after her ever since. Whatever the precise truth behind the yarn, its intended message is unmistakable: the experience of being Italian is baked into the food of the ordinary Neapolitan.

It’s a story that would have intrigued Vincenzo Corrado, a man born and bred in the south a century and a half before Queen Margherita’s supposed conversion to the delights of Neapolitan cuisine. Corrado explored that cuisine in the pages of his series of cookbooks, which are a vivid testimony to the cultural life of eighteenth-century Naples, a city of dizzying social disparities and abundant artistic expression. Unwittingly, Corrado did more than almost anybody to define what we think of as Italian food, in which—especially as the food exists in its international incarnations—the flavors of Naples are so prevalent. Yet, one wonders what Corrado would have made of the ways in which food has been used as an important binding agent in the creation of an Italian national identity. Sincere as he was in his passion for the food of his homeland, he recognized that a plate of food is layered, like a Neapolitan timbale, with meanings and associations. As his recipes testify, much of what we consider to be authentically local, regional, or national, rests on small acts of self-deception and selective memory, the endless making and remaking of myths.

*

Vincenzo Corrado was born in 1738 in the town of Oria, in the region of Apulia, part of the Kingdom of Naples, which essentially covered the southern half of what we now know as mainland Italy. We know little more about his youth than that his family origins were unspectacular, and that after the death of his parents he may have gone into service at the court of a Neapolitan aristocrat.

The years of Corrado’s childhood were an exciting time for the city of Naples, which was then the heliocentric force within the Kingdom. Since antiquity Naples had occupied a special place in Mediterranean life. In the days of the Roman Empire, it had been a paradisiacal southern retreat for the wealthy and powerful. But by the era of the Renaissance it was one of the most heavily and densely populated cities in the world. As a site of tremendous strategic importance in their wars against Muslims to the east and Protestants to the north, Naples’s Spanish rulers turned the place into a fortress, forbidding any building outside the city walls. The growing population piled up on top of itself. At a time when it was unusual for European cities to have buildings of more than two or three stories, Naples had the early modern equivalent of skyscrapers, reaching five, six, or seven stories tall. When Caravaggio turned up in 1606, he was struck by the intensity of Naples, all the extremes of city life in such close proximity. Within a month of his arrival, he had painted The Seven Works of Mercy, perhaps the most vivid record of the unique energy that so many felt in Naples, a combustible exuberance, simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying.

When the eighteen-year-old Charles of Bourbon acceded the throne in 1734, he embarked upon a reign of so-called enlightened absolutism, turning Naples into what one historian has described as “an intellectual laboratory where intellectuals and government collaborated.” Under his guidance, there were reforms of the judiciary, the civil service, and taxation laws, and Jewish people were officially allowed to settle in the Kingdom for the first time in centuries. Before abdicating the throne to his son Ferdinand in 1759, Charles also invested heavily in Neapolitan arts and culture, patronizing artists, funding theaters, and recruiting the architects Ferdinando Fuga and Luigi Vanvitelli to design many of the landmarks of modern Naples. Taking Charles’s lead, wealthy Neapolitans used their money to beautify the city. One such person was Raimondo di Sangro, who paid for the reconstruction of the Chapel of Sansevero, complete with Giuseppe Sanmartino’s statue Veiled Christ. It was a work of such astonishing quality that locals suspected it had been made with alchemical wizardry rather than a sculptor’s chisel. At the same time as crafting the Neapolitan future, Charles also rediscovered its past: it was he who commissioned excavations of nearby Pompeii, one of the great cultural moments of the eighteenth century.

It was against this backdrop that Vincenzo Corrado entered a Celestine monastery in Naples at the age of seventeen, where he received a thorough education in astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, and history. He also began a culinary education, traveling the Kingdom of Naples and other parts of the Italian peninsula, collecting recipes as he went. We don’t know much about how he refined his skills, but he evidently paid close attention at the tables, kitchens, and marketplaces of the various places he visited; the knowledge he would later display of food from Italy and beyond was immense.

Though it was the contemplative life of the monastery that brought him to Naples, it was the worldly pleasures of cooking and eating that made Corrado’s name. At the court of Michele Imperiali, Prince of Francavilla, he was given the magnificent title of Capo dei Servizi di Bocca, literally translated as “Head of Mouth Services,” and given responsibility for planning banquets that were not only lavish in the quality and quantity of the food served, but distinctly theatrical, of a piece with the social world of Naples that focused so much on display and performance. As well as dozens of individual dishes, Corrado designed table settings and elaborate ornamentations, often complex sugar sculptures or small models made from marzipan. He left few details of exactly who he cooked for, but the Prince attracted the glitterati from across Europe, and Casanova was a guest of his in the 1770s.

The guiding spirit of these elite occasions was certainly Parisian, the default setting of fashionable society across Europe. In Naples, high-status cooks were referred to as monzu, a Neapolitan corruption of monsieur, an indication of the style and atmosphere that Corrado’s food would have been expected to project. It’s for this reason that Corrado’s first book, Il cuoco galante, was a landmark in the development of Italian food—and therefore in the development of Italian national identity—when it was published in 1773. The last cookbook in a native language of Italy was published in the 1690s by Antonio Latini, another Neapolitan, and even that comprised mainly French- or Spanish-style dishes; it was the gastronomic testament of a thoroughbred monzu. In Il cuoco galante, Corrado pointed toward the Italian future, interweaving the dominant fashion for French cuisine with distinctively Italian flavors and textures. Though most of the peninsula is represented in one way or another, it is the Kingdom of Naples to which Corrado returns over and again. Throughout the text, he extols fish from the Bay, as well as the cheese, meat, fruits, and vegetables from Campania, and other southern regions. He has prototypical recipes for things that remain classics of Neapolitan cooking: Genovese sauce, timbales of various kinds, and parmigiana—though as he wasn’t keen on eggplant, his version uses fried slices of squash, layered between Parmesan and butter. For a wealthy, well-to-do audience, Il cuoco galante was the most articulate statement of colloquial Italian food to have been written for more than a century.

There’s a parallel between Corrado’s take on food and other trends in eighteenth-century Neapolitan culture, most notably opera buffa, a form of comic opera that told stories of ordinary Neapolitans, using the language and settings that everyone in the city would recognize. By 1730, Naples had three theaters dedicated to opera buffa, and the form spread to the rest of Italy. Some say the assertion of Neapolitan identity, sometimes at the expense of the political, social, and cultural establishment, can be detected in Corrado’s food writing. In a recipe for pheasant—stuffed with veal, wrapped in bacon, roasted on a spit—he remarks that the birds are in season from winter to spring when they are “persecuted and murdered by hunters,” a strange turn of phrase which the food historian Gillian Riley asserts is a dig at “the sport of kings, enjoyed by the idle and illiterate Bourbons,” the foreign dynasty that ruled the Kingdom.

Corrado was tapping into a widespread feeling of pride in Neapolitan food, but one that was tempered by social and cultural resentments, exacerbated by a deadly famine in 1764. At the cuccagna festival of that year—a kind of early modern Black Friday, in which the poor were encouraged to fight each other as they devoured giant structures made of food—the nobles were disgruntled that the chaos had begun before the King gave his signal. At the carnival four years later, pasta makers, seen by some as guardians of the true Neapolitan identity, handed out pamphlets denouncing the social elite for filling their tables with foreign foods. Pasta had become a symbol of everyday Naples only relatively recently. During the Renaissance, Neapolitans had been referred to, derisively, as “cabbage eaters” by those outside the region. From the late seventeenth century, images of lazzari (the poorest of all Naples’s inhabitants) eating long strands of pasta with their fingers began to appear in depictions of the city, and Neapolitans were now called mangiamaccheroni—“macaroni eaters.” Yet, Il cuoco galante shows us that pasta, and many other types of Neapolitan cucina povera, were also eaten by the wealthy and powerful. Corrado wrote down recipes for gnocchi, lasagna, ravioli, vermicelli, and a startlingly rich macaroni timbale, filled with cheese, sausage mince, mushroom, truffles, and ham, all cooked in a mold of flaky pastry. Though some of Corrado’s recipes were well beyond the means of ordinary people, in this city of extremes the consumption of pasta provided a common experience. Some sources suggest that even King Ferdinand IV ate pasta with his fingers just as the poorest of his subjects did.

What Corrado does not give us, either in Il cuoco galante or any of his subsequent works, is a recipe that fuses pasta with tomato sauce, the combination that, rightly or wrongly, has come to define Neapolitan—and Italian—food for millions around the world. The food historian John Dickie has described tomato sauce in Italy as “a national religion: its Holy Trinity is Fresh, Tinned and Concentrate; and its Jerusalem is Naples.” But, when Corrado was writing, the default accompaniments of pasta were butter and cheese; tomatoes—apples of love, as they were called in English—were still considered poisonous by many Europeans, and even Corrado, who encourages their use, advises removing the seeds and skin before cooking with them, such as in a recipe he called pomodori alla Napolitana, in which tomato halves are stuffed and fried. Elsewhere, he gives us tomato soup, tomato fritters, tomato croquettes, tomatoes stuffed with rice and truffles or anchovies. He also describes a precursor of passata, a broth of tomatoes fried in oil with garlic, parsley, radish, bay leaf, and celery, bulked out with bread crusts and pushed through a sieve. Though he may not have hit upon the killer combination of pasta and tomato sauce, the success of Corrado’s cookbooks (Il cuoco galante was reprinted several times in the decades after its publication) helped ensure that tomatoes became a key ingredient in Neapolitan cooking.

Beyond tomatoes, Corrado adored fruit and vegetables. In 1781, eight years after Il cuoco galante, he published Del cibo pitagorico, expounding the virtues of vegetarian food, and the bounty of the Kingdom’s harvests. His passion for local produce was evident, yet he was also keenly aware that much of what he was dispersing as Neapolitan cuisine was an invention of tradition, rather than its continuation. Tomatoes were products of the Americas, brought to Naples by its Spanish rulers, as were coffee and chocolate, novel ingredients that he included in his recipes. The same was true of potatoes, about which he published a book of recipes in 1798. A number of those recipes, the first in Italian history, have become Neapolitan favorites, such as potato cake, which Corrado suggested making with sweetbreads and pig’s liver.

As Corrado busied himself with a quiet revolution in Italian food, the violence of political and social revolution swept across Italy, leaving the Kingdom of Naples prone. In 1798, alarmed by Napoleon’s conquest of northern Italy, King Ferdinand decided to send an army of seventy thousand soldiers into Rome and halt the French advances. It was a calamitous error. Back in Naples, revolutionaries declared the end of the monarchy, though the nascent republic was violently torn down with the help of thousands of rural peasants and the lazzari of Naples, the “macaroni eaters,” a minority of whom were alleged to have acquired a taste for human flesh. Whether or not reports that counterrevolutionaries “ate their neighbors roasted” are true, they underline the astonishing brutality that enveloped Naples in the final year of the century. For the first sixty years of Corrado’s life, Naples had been a place that spoke of progress, of high ideals of civilization, beauty, and a celebration of Neapolitan culture, all of which shone through in Corrado’s work. As the city spasmed its way to the end of the century, it’s tempting to wonder which of his recipes the old chef turned to for comfort, redolent of the land he loved.

*

Naples was in a tug of war for the next several years, until Napoleon’s demise allowed the Bourbon dynasty to reassert a firm grip on power. Corrado’s writing career wound down; the small amount he published lacked the exuberance of earlier work, perhaps reflecting his mindset in these more subdued, uncertain times. But he lived long enough to see stability return to Naples; he died aged ninety-eight in 1836, by which point a great deal of his take on Neapolitan cuisine had become standard.

Bourbon rule of Naples continued for another twenty-five years, until it was overwhelmed by the forces of national unification. When Garibaldi’s men closed in on Naples, a leader of the nationalist movement had rejoiced that “the macaroni are cooked and we will eat them.” The outside world, it seems, still tended to view Neapolitans through the holes of a colander, and in subsequent decades the old images of the lazzari eating pasta with their fingers were updated, in photographs staged for tourists who wanted a souvenir that summed up the city in one arresting cliché.

By the close of World War Two the Neapolitan diaspora had exported its cuisine to the rest of the planet. Elaborations on the traditional recipes from the old country were now viewed as quintessentially Italian, especially in the United States. When Paulie Gualtieri goes “home” to Naples in The Sopranos, he’s shocked to discover pasta served in ways he can barely stomach. Native Neapolitans mock him for requesting “gravy” with his macaroni: “and you thought the Germans were classless pieces of shit,” they say, in a language Paulie understands no better than the food on his plate.

As the international fame of Neapolitan food grew, so Italy itself became more attached to it. By the sixties, pizza of the variety made for Queen Margherita was essentially a national dish—a national symbol, even—along with many of the recipes sketched by Vincenzo Corrado nearly two centuries earlier. His books are still reprinted and read across the peninsula, and cafés, pizzerias, and trattorias across southern Italy bear the name “Corrado,” a word now synonymous with the glories of Italian gastronomy.

Read earlier installments of “Off Menu.”

Edward White is the author of The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America. He is currently working on a book about Alfred Hitchcock. His former column for The Paris Review Daily was “The Lives of Others.”

July 6, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 16

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“As the pandemic set in, a peculiar thing happened to me: I found myself unable to read fiction, despite having always been drawn to novels and short stories over essays or poetry. I suppose I like the escapist element, or can appreciate a good lie; as Gabriel García Márquez, a former journalist, said in his Art of Fiction interview, ‘A novelist can do anything he wants so long as he makes people believe in it.’ In those early days of panic and uncertainty, the appeal of nonfiction, of facts, figures, and interviews—of real people and real events—was obvious. Public understanding of the coronavirus was murky at best, and I didn’t quite know who or what to believe. Months have passed since and we have learned more about the particulars of this disease, and how best to prevent its spread; I’ve also returned to reading fiction. But I still find myself intrigued by reportage, essay, documentary, and the like. This week’s Art of Distance highlights some of the boundary-pushing nonfiction that the Review has published over its sixty-seven years, and pokes at that sometimes tenuous border that separates fact from fiction. (It’s a border that has at times stretched and changed even within our own pages: this excerpt from Jean Genet’s novel A Thief’s Journal was published as a work of nonfiction in issue no. 13.) Read on for all the news that’s fit to print—or, at least, to be unlocked from the Paris Review archives.” —Rhian Sasseen, Engagement Editor

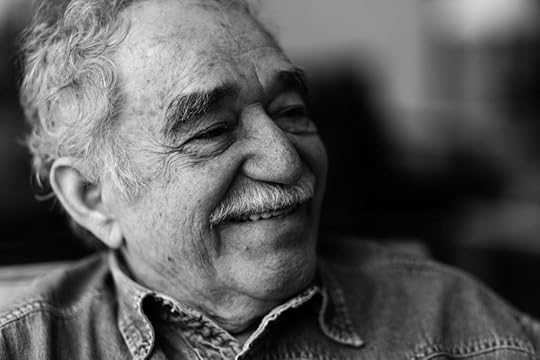

Gabriel García Márquez.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t open this survey with The Art of Nonfiction No. 1, in which Joan Didion speaks with Hilton Als. While Didion constantly dances between nonfiction and fiction (she was also the subject of an Art of Fiction interview), there is something especially fascinating in the way she describes the differences between the two genres: “Writing nonfiction is more like sculpture, a matter of shaping the research into the finished thing. Novels are like paintings, specifically watercolors. Every stroke you put down you have to go with.”

As I mentioned above, Gabriel García Márquez was a writer who worked in newspapers in the early days of his career; in this feature from the Winter 1996 issue, written by Silvana Paternostro, Márquez discusses his own reportaje, saying: “The strange episodes in my novels are all real, or they have a starting point, a basis in reality. Real life is always much more interesting than what we can invent.”

The question of classification, of what constitutes history or fabrication, comes up again and again in discussions of the work of W. G. Sebald, whose novels incorporate photos, facts, and real people and events in a way that stretches the already-elastic definition of the novel. Here, in this 1999 profile from issue no. 151—published just two years before Sebald’s unexpected death from a brain aneurysm while driving—the question of fact versus fiction comes up again: “Facts are troublesome,” he tells James Atlas. “The idea is to make it seem factual, though some of it might be invented.”

Of course, recording facts is a form of witnessing, too, and some writers weave facts together in works that, in their emotional complexity, are equal to any novel, such as the Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich, who creates literary collages out of interviews on subjects ranging from Chernobyl to the experiences of Soviet women in World War II. Her “Voices from Chernobyl” can be found in issue no. 172. And “Nineteen Days,” a series of diary entries from the dissident Chinese writer Liao Yiwu, published in the Summer 2009 issue, paints a clearer portrait of political repression in contemporary China through this record of events on June 4 each year from 1989 to 2009.

There’s plenty of more traditional on-the-ground reporting, too, such as Karl Taro Greenfeld’s “Wild Flavor,” which follows a worker named Fang Lin at the turn of the new millennium and the early days of the SARS outbreak in Shenzhen, China; some of these sentences are especially haunting to read now: “What terrified Fang Lin most when he was conscious was the sense that he was running out of air. No matter how freely he breathed, he felt that he was not inhaling oxygen but some other odorless, tasteless gas.”

Rounding out this selection is Sarah Manguso’s essay “Oceans,” from the Spring 2019 issue; it’s a series of fragmented meditations from the poet turned prose writer on the ocean, surgery, mortality, and the human body. You can also listen to Manguso read the essay on the second season of The Paris Review Podcast. And if you liked “Oceans,” our latest issue features another essay by Manguso.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

Into the Narrow Home Below

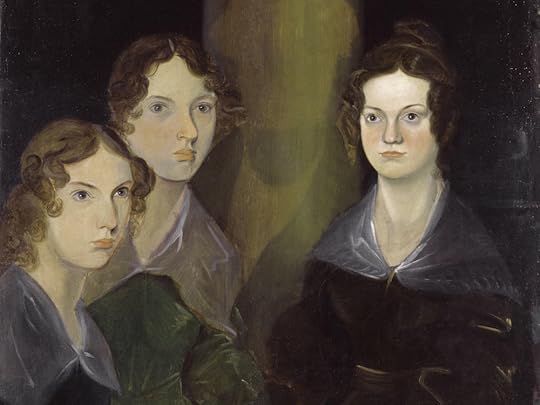

Branwell Brontë, The Brontë Sisters (Anne Brontë; Emily Brontë; Charlotte Brontë), ca. 1834, oil on canvas, 35 1/2 x 29 1/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Well there are many ways of being held prisoner.

—Anne Carson, “The Glass Essay”

Twenty years ago, the writer Douglas A. Martin was a student in my fiction workshop at the New School. He was in his early twenties then, an extravagantly gifted young man who sometimes wore a white feather boa to class, his face regularly shining with tiny bits of pink glitter. His stories about young gay men struggling for a place in this world, erotically and artistically, were shot through with a raw and supple longing.

Martin often came to my office hours, where we’d talk about books and films. I learned about his childhood in Georgia and his alcoholic father, a man he was estranged from and hadn’t seen since he was little. In one of these discussions we talked about the Brontës. I was doing research for a talk on Wuthering Heights. I’d been surprised, as Martin was, to hear the Brontës had a brother. Branwell was a ginger, with “a mass of red hair, which he wore brushed high off his forehead … to help his height.” He fancied flowing white shirts and was both freckled and bespeckled. “Small but well formed,” he was unable to control his emotions and had spells of what was called then hysteria. His friend, the sculptor Joseph Leyland, said Branwell’s conversation, his “beautiful and flowery language,” he “never saw equaled.”

Like his sisters, Branwell wrote poetry and he sent poems along with long, pleading, naive letters to the literary men of the day—Wordsworth, De Quincey, and Coleridge—asking for feedback, for affirmation, even for love. In one letter to Wordsworth, which the great man kept but did not answer, Branwell wrote: “I most earnestly entreat you to read and pass your judgment upon what I have sent you, because from the day of my birth to this the nineteenth year of my life I have lived among wild and secluded hills where I could neither know what I was or what I could do—I read for the same reason I ate or drank—because it was a real craving of Nature.”

Martin was drawn to Branwell’s feminine qualities. “The idea that being a poet,” Martin tells me, “one could be fem.” He did some research of his own and decided to write Branwell: A Novel of the Brontë Brother. The Brontë siblings’ intense circle fascinated him—the way they bled into one another. In Wuthering Heights, Catherine is Heathcliff, and Branwell, it seems, was his sisters, leaning into their gender and leading their literary aspirations. He was the first to publish poems in the local newspapers, first to cut the path toward a life of letters. The Brontë boy was grandiose, emotionally unstable, and eventually a drug addict, but his model of creative engagement opened up a dream space that Emily, Charlotte, and Anne walked into without him, an imaginary room his sisters eventually made their own.

*

What are People of the Book but irrepressible embroiderers of fetishized texts?

—Judith Shulevitz, “The Brontës’ Secret”

“I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.”

Martin’s Branwell dilates one such gap: the “unspeakable acts” Branwell was said to have committed at Thorp Green. In both Daphne du Maurier’s 1962 The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë and Martin’s book, Branwell’s claim of an affair with his employer’s wife, Mrs. Robinson, is seen as a screen for a homosexual liaison. The scholar Richard A. Kaye calls Branwell a queer speculative biography. He suggests that “queering the Brontës often involves an imaginative disregard for the available evidence regarding Brontë’s family secrets in order to take advantage of unresolved biographical cul-de-sacs.”

The less disputed biographical events in Branwell’s life are mostly sad. His mother, Maria, died when he was four. “For seven months,” Martin writes, “she suffered waiting only for Jesus to take her.” His father, the reverend Patrick Brontë, tells his young son that his mother’s holiness has been envied by their enemy, the devil, that this is why his mother yells out, swears, and is often incoherent. Two years later his older sister Maria, who had served as a surrogate mother, also died. Branwell remembered being lifted up so he could see her in the coffin. “Down, down they lowered her, sad and slow,” Branwell will write in a later poem, “Into the narrow home below.”

The Brontë children’s grief was channeled into what Charlotte would later describe as “scribblemania.” Anne, Emily, Charlotte, and Branwell had their own room on the top floor of the parsonage, known as the Children’s Study. There they read the newspaper every day, as well as books about British history and Greek mythology. They perused literary magazines like Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine and church newsletters. They also created their own newspaper, The Monthly Intelligencer, and published small books using stray paper. They covered these books with bits from sugar bags, parcel wrappings, and wallpaper, and developed a tiny script that looked like newsprint.

“Childhood,” Martin writes, “was Branwell’s kingdom to rule over.” The Brontë children’s sagas revolved around a set of toy soldiers that their father gave his son. In an early text written when Branwell was only eight, he creates an origin story from the point of view of the tiny soldiers. “An immense and terrible monster his head touched the clouds was encircled with a red and fairy halo.” Branwell is the ginger-haired giant carrying the soldiers to his sister’s bedroom.

Martin’s Branwell, as he moves into adolescence, is under pressure to move away from fantasy into the world of adult achievement. He is expected to make a name for himself as an artist or a writer and to eventually support himself as well as his siblings. “They will try to give him a certain status, as their real achievement.” “Branwell was to be the pride and joy of them all.” “They’d have to make something of him.” The weight is constant, even haunting. “He can hear his father in the other room committing another sermon to memory. They are pinning their hopes on Branwell, all of them.”

The narrative encloses Branwell in rising familial expectation while also exploring his vulnerability, grief, and bewilderment. The brother cannot break away from his witchy, powerful sisters. Even his first feelings of sexual attraction are mediated by them: “If Charlotte could see him, staring at the broadness of the chests of other men, she might make fun of him.”

Branwell’s desire for men is in keeping with his sisters’ desire for men, though unlike his sisters he cannot transpose that desire for men onto a story. His passion could not be elevated, transformed, and redeemed, as in Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre, because for him to love a man physically in the early nineteenth century was to face not just ostracism and ridicule but possible death.

In Queer City, Peter Ackroyd reports that after the 1533 Buggery Act passed in England “you could die for deeds done in the dark.” Between 1806 and 1835, more than eighty men were hanged for sodomy. After one large raid on the back room of the “molly house” The White Swan, a mob gathered outside the building where the men were being held. When the prisoners were moved, “butcher boys threw dead cats, turnip heads and other garbage.” One spectator reported that the men resembled “bears dipped in a stagnant pool … their faces were completely disfigured by blows and mud.”

*

I had woken in a small pool. Several cattle had wandered into my shelter after me and stood at the far side watching me as I woke and then rose.

—Robert Edric, Sanctuary

Life at the Black Bull bar, a masculine circle of storytelling and lively conversation, finally pulled Branwell from the world of his childhood. “Drinking, he no longer acted like his sisters,” Martin writes. “Branwell, the minister’s son, he’s the wildest boy in town!” His drinking leads to blackouts. “A penniless debauchee rose from the floor of a rather sordid inn and realized this was where he’d spent the night.”

Martin has said that Wuthering Heights had a profound effect on him as a teenager—“I became fixated on the color of my edition, this shade of pink”—but it was Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea that brought the Brontës’ project to life and showed him how to lay his own emotional landscape on top of a fictional character. The novel tells the backstory of Antoinette, the first Mrs. Rochester from Jane Eyre. Rhys, like Branwell, was an alcoholic; The Blue Hour, by Lilian Pizzichini, describes how she once threw a brick through her landlord’s window because his dog had killed her cat, Dr. Wu. How after a bottle of red wine, she’d pin her husband’s World War I medals on her nightgown and go into the streets shouting, “Wings up! Wings up!” Rhys, Pizzichini explains, found “inner peace” whenever she was in crisis: “at the bottom of the abyss was where she belonged … no one could push her down any further.”

As failures pile up for Branwell—he blows all his money on a trip to London where he was meant to enroll in the Royal Academy of Arts; he gets fired from a job with the railroad for embezzling money, then fired again at Thorp Green—he tries opium. Soon he is addicted. “A wretched black bottle, their sister Charlotte says, has become his means of release.”

Opium was as common in Victorian England as spirits, and cheaper. In 1830, in the years just before Branwell tried the drug, British dependency on opium for medical and recreational use reached an all-time high, as 22,000 pounds were imported from Turkey and India. Still, addiction in Branwell’s time was “cold debauchery” and “a disease of the will.” The bondage was recognized but not the fact that humans are bonding creatures—Branwell could no longer bond with his sisters, so he bonded with drugs and alcohol.

Charlotte had not spoken to Branwell for two years at the time of his death. Only Emily continued to care for her brother, helping him up the stairs when he came home drunk and sitting by his bed as he slept. Carolyne Van Der Meer suggests in her essay on the roots of Wuthering Heights that Heathcliff may have also been an opium addict. She points to his “tremors, loss of appetite, obsession with Catherine.” Emily continued to care for Branwell even as paranoia set in—he thinks a wolf trails him and is so convinced someone wants to kill him that he carries a knife in his sleeve. According to Van Der Meer, Emily “recreated Branwell in the body of Heathcliff to give her brother, though a fictional portrayal, the dignity he lacked in life.”

In Branwell’s last months, Charlotte wrote in a letter to a friend that “he leads papa a wretched life.” Both the addict and their loved ones suffer. In the margins of Modern Domestic Medicine by Thomas J. Graham, the Dr. Spock of the Victorian age, Branwell’s father, Patrick, adds to the section on Insanity or Mental Derangement: “delirium tremens brought on sometimes by intoxication—the patient thinks himself haunted: by demons, sees luminous substances in his imagination, has frequent tremors of the limbs.”

Some of Martin’s most beautiful passages describe Branwell’s drug use. Victorians did not get high or stoned but elevated. “Now things were more vivid, the presence of objects near more exaggerated, the outlines of people, places, things more distinct, as if lost a bit in golden mist, as he tried to pin the sun of a summer shining down … alone in his room, a world of wild roses opening up under the yellow.” And: “The opium helps him feel his own suffering. It courses through him in dreams the opium helps bring, dreams that turn the tender look of Emily’s face a bit softer … a bit more toward the motherly, like the skin of a peach.”

*

I know only that it was time for me to be something when I was nothing.

—from Branwell Brontë’s letters

In the last pages of Martin’s book, as Branwell falls deeper into nothingness, he imagines a liaison between himself and his young charge at Thorp Green, Edmund. I have taught Branwell for ten years in my literature seminar at the New School. Every year one of my students will take the Brontë son’s reverie as reality and call him a pervert and a child molester. Martin addresses the readers’ deep unease. “Dear Reader, you want to be told now that you’ve understood. That he might be doing just what you think he might be, and in just what way, you want to be sure.”

“It makes a man a beggar,” Martin writes, “not having the right words for his feelings.” Branwell saw no reparative way forward. He could not, with his illicit inchoate desire, sublimate, as his sisters did, his life into art.

Instead, Branwell served as muse. Not the traditional female muse who inspired the male artist with her beauty, her ethereal angelic soul as well as her sexual favors, but a dark and raging spirit, a drug addict in an endless struggle. A struggle that included scenes of raw need, bloody disappointment, a struggle that frustrated and even horrified his sisters, but one that also gave life to their most compelling characters: Emily’s Heathcliff and also her Hindley, and the alcoholic husband Arthur Huntingdon in Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, even Charlotte’s wild women in the attic. In Jane Eyre, Jane sees the fire in Mr. Rochester’s bedroom but not the arsonist. “Tongues of flame darted around the bed: the curtains were on fire.” In Wide Sargasso Sea, we get to see Mrs. Rochester moving down from the attic, carrying her candle. She’s made a life inside of loss. There are no more acts of self-love, only ones of desperation and violence. “Now at last I know why I was brought here and what I have to do. There must have been a draught for the flame flickered and I thought it was out. But I shielded it with my hand and it burned up again to light me along the dark passage.” In Martin’s book, Branwell also starts fires.

*

I used to think, if I could have for a week the free range of the British Museum—the Library included—I could feel as though I were placed for seven days in paradise but now really Dear Sir, my eyes would roam over the Elgin marbles, the Egyptian Salon and the most treasured volumes like the eyes of a dead codfish.

—from Branwell Brontë’s letters

Even as a boy, Martin told me, he understood his father drank because of the pressures on him. The weight. “He drank because he couldn’t take care of us.” Branwell could not take care of himself or his sisters, so in the Brontë parsonage the father Patrick cares for his dying son, taking him into his bed where he can watch over him and keep him safe. Branwell shows Martin, the son, extending empathy to the alcoholic father. Failure is not to be judged and ridiculed but rather serves as a conduit to grace.

“They were only happy with Branwell when he’d tried to please them,” Martin writes. “The only feelings they’d keep were the ones they wanted him to feel. He didn’t dare hope for forgiveness, as fate became an increasingly darkening thing, didn’t dare ask.”

Darcey Steinke is the author of Flash Count Diary: Menopause and the Vindication of Natural Life, the memoir Easter Everywhere, and five novels: Sister Golden Hair, Milk, Jesus Saves, Suicide Blonde, and Up through the Water. Her books have been translated into ten languages, and her nonfiction has appeared widely. She has taught at the New School, Columbia University School of the Arts, New York University, Princeton, and the American University of Paris. She lives with her husband in Brooklyn.

Copyright © 2020 from the introduction to Branwell: A Novel of the Brontë Brother . Reprinted by permission of Soft Skull Press.

I’m So Tired

Sabrina Orah Mark’s column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

Arthur Rackham, Sleeping Beauty/Briar Rose, 1920

I am halfway through writing an essay about “Sleeping Beauty” when I get a text from my mother: “It’s lymphoma.” My sister. She is twenty. Three lumps on her neck. I erase the entire essay. And then I vomit.

Ever since we went into our homes and shut the door, I have been comforted by images of nature reclaiming deserted places. I search the web and watch snow fall on a dead escalator in an abandoned mall. I find a tree growing out of a rotting piano. The pedals have disappeared into the earth, and on its brown wooden torso someone has carved the initials “C+S” inside a heart. For hours, I search the web for more. Goats walk through city streets as if remembering the woods that once grew there. White mushrooms push up through the floor of a cathedral. I trace each mushroom with my thumb. It makes me want to pray.

“I don’t believe in anything anymore,” says my mother. “Don’t say that,” I say. “Please don’t say that.” But she can’t hear me. She’s already somewhere far, far away.

Before the text, I had been writing about Charles Perrault’s “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” because I wanted to write about the bramble. I wanted to write about the hedge of briars that grows around the castle when Sleeping Beauty pricks her finger on a spindle and falls asleep for one hundred years. I wanted to write about the fairy who touches the governesses, ladies-in-waiting, gentlemen, stewards, cooks, scullions, errand boys, guards, porters, pages, footmen, and the princess’s little dog, Puff, so that they all fall asleep, too. I wanted to write about the kindness of the fairy who makes sure when Beauty wakes up she doesn’t wake up alone. I wanted to write about the wind dying down, and the sleeping doves on the roof. I had an idea that the bramble was good. That what we’ve needed all along is for us to hold still and allow nature to grow wild around us. I had this idea that when we all woke up together, the bramble would teach us something. I imagined we’d all rub our eyes and a new civilization would hobble toward the bramble and learn to read its script. I imagined the bramble clasped together like hands filled with cures and spells. I imagined we’d learn a lesson that could save us.

“The lesson,” says my mother, “is that we’re all going to die.” But my mother doesn’t say this. She would’ve said this two weeks ago before my sister was diagnosed with lymphoma because it’s like a thing my mother would say. But now when she speaks she sounds different. She has an echo now. Like the only mother awake in a castle filled with sleeping daughters.

My sister is breathtakingly beautiful. This is a fact. When she walks into a room people turn around and stare.

“Maybe you should write about widows instead,” says my husband. A small vine begins to creep up his neck and winds around his face. “I am not writing about widows,” I say. And the vine vanishes.

When I was twenty-nine and my sister was five, my mother and I brought her to Disneyland, where you can eat breakfast at Cinderella’s castle with all the princesses. The princesses came out all at once, as if through a hole in the air, and spun around in their blue and pink and yellow gowns. My sister climbed onto the table and reached her arms out. Had my mother and I not pulled her back down, she would’ve let the princesses pick her up and carry her away.

I write about Sleeping Beauty and then I erase everything I write about Sleeping Beauty, while my husband starts saving eggshells, and carrot peels, and coffee grinds, and bread, and dryer lint, and banana peels, and orange rinds in a plastic container that sits on our kitchen counter. He has started worm composting. In three to six months he promises we will have nutrient-rich soil to grow more flowers and vegetables. I am worried there won’t be enough airflow, and he will forget to harvest the worm castings, and all the worms will die. I am worried about maggots and rot. “Trust me,” he says. “Please trust me.” And he’s right. I need to trust him more. And I need to trust the worms and the air and the soil more, too. But I’m still worried.

“I wish everyone would just fall asleep,” says my mother, “and not wake up until Sasha is okay again.” I want to assure her when Sleeping Beauty wakes up she gives birth to a son and a daughter named Day and Dawn. But what a stupid thing to say. What good am I? An old daughter writing about fairy tales when I should be cooking my mother and sister actual soup. “She’s going to lose all her hair,” says my mother, which makes me want to cut off mine and swallow it.

“Your book came,” says my husband. He hands me Christopher Payne’s North Brother Island. I had ordered it weeks ago, and had half given up on it ever arriving. It’s a book of photographs of an uninhabited island of ruins in the middle of the East River. Once used as overspill for college dormitories, then as a quarantine hospital island to treat infectious disease, and then later for drug addiction, it was abandoned in 1963. A forest of kudzu and rust grows around it. Sunlight bounces off disappearing buildings. Water drips through collapsing roofs. Oh, brotherless North Brother. Even the herons who made it a sanctuary flew away in 2011, and no one knows why. And then the swallows came.

“I can’t find my goddamn earbuds,” says my mother. I imagine peonies and daffodils and heliotrope blooming from her ears. “Let me call you back,” she says. But she doesn’t call back. She forgets to call me back. My sister has lymphoma, and that’s all any of us can remember. I imagine her phone crisscrossed by spiderwebs and dust.

In the essay I erased, I wrote about the old fairy. The one who was forgotten. The one who was assumed dead or bewitched, but she wasn’t. She was very much alive, but when Beauty is born she isn’t invited to the ceremony. And so when the fairies bestow gifts upon the princess, the old fairy emerges from her dust and out of spite declares Beauty will die from a prick of the spindle. Another fairy steps out from behind a tapestry. She cannot undo the old fairy’s spell but she can change dying to sleep that will last a hundred years. In the essay I erase, I write something about how we are quarantined inside our kingdom because we forgot the old fairy. I write something about how we are not asleep, but we’re also not awake. I write in the essay I erase that had I been the old fairy, I would’ve cursed us, too, and that we don’t deserve to be kissed and woken up. But I take it all back. I want the bramble to part. When did this tear in a fairy tale become wide enough for my whole family to climb through? I want to beg the old fairy for forgiveness. Where is she? Who cursed my sister?

I want to go to North Brother Island, and just stand there until a patch of moss grows on my cheek. “I’m so tired,” says my mother. “I’m so tired, I’m so tired, I’m so tired.” I want to hold my mother’s hand on North Brother Island. I don’t remember ever holding my mother’s hand though I must have, at least once, as a child. I want the moss to grow on my mother’s cheek, too. When enough moss grows I will peel it from our cheeks and boil it and give it to my sister on a spoon like medicine. Like a miracle cure. I tell my mother about North Brother Island. “Maybe we should buy it,” she says. “I need somewhere to go.” What I don’t tell my mother is that we have already gone somewhere. We are already in this place where the world we once knew is rushing out of us. We are standing in its unbearable greenness. There is a pinprick on my sister’s finger that is so small and so black it can easily be mistaken for a pokeberry seed.

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

July 2, 2020

The Pain of the KKK Joke

“The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend twenty years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.” — Toni Morrison

Some time into my studies at university, as I was walking up the avenue that cut between the green fields of east campus and the wide blue of Lake Michigan, headphones in my ears and daydreaming about something or other, I came across a white classmate who was a rather good friend of mine striding along in a KKK costume.

He was in full regalia: the sheet covering the entirety of his body, the rope tied around his waist ready for lynching, the eye-slitted hood carried under his arm. He saw me and stopped to talk, so I had to stop as well. But, unlike him, I was unable to carry off a nonchalant conversation, and I asked him what he was doing with all that. He blushed, as he began to register how he appeared to me, and said it was for a joke. Then, at my shocked expression, he said it was for a class project. When I asked which one, since we were the same major and in nearly all the same classes that year at Northwestern, he muttered that it was something to do with his fraternity, and that he had to go.

We never spoke of this again. Instead, I remained silent, and we remained friends. He was part of the central group of the privileged, popular, and powerful in my predominantly white university—the kids whose parents’ money or connections already made them players in the careers to which the rest of us aspired. He and I worked on independent film projects together for years, attended the same parties where offers were extended; both my summer internship and the housing situation for that internship were landed because of this group of friends. As second- and third-generation legacies, scions of generational wealth and cultural capital, they had power and access. I, as the first-generation child of refugees, had only the brains and work ethic my parents had gifted me, but which were enough to secure me a tenuous place.

Speaking, I knew even back then, would have meant being shut out of that world. And learning to understand that world, my father had told me, wide-eyed with surprise that I did not yet get it, was the real reason for taking on the student loans and the work-study jobs necessary to afford the elite university I attended. The straight A’s were only half the point, my father had said. The other half was everything else—the cultural capital, the access—which my father, who had worked harder than I could ever understand to survive a genocide and get us to America, knew that I would need in order to succeed in this country.

But mostly, I was just afraid.

So, like many Black people in my situation, I stayed silent even as the racism grew. It was training, I was understanding, for the real world after university, which would be more of the same.

*

I have had the KKK joke made to my face by non-Black people not just at school, but also in personal situations and in professional ones—from after-school jobs as a teenager to the boardrooms I sat in decades later. Now, in the midst of the current global Black Lives Matter protests, when someone wields the KKK joke, I think about how my aunt’s Minnesota neighborhood and several students in my town here in Nebraska have recently been attacked by the KKK and other white supremacists. Since he was six months old, my son and I have had run-ins with white supremacists, unhooded and in daylight, who tell us to go back where we came from while they threaten what violence they are going to do to us if we don’t.

There is no one KKK joke. There is, however, a wide catalogue of unabashed racism to choose from in creating one. There is always a certain kind of person who feels like it is important to make jokes about the KKK, whether or not Black people are present. This is often the same kind of person who thinks Blackface and pretend AAVE—or jokes about raping women or killing transgender individuals—are important as well. It is part of a consciousness—often white, often male—that does not see us as human beings but as objects to be violated because of our Blackness. And, if it cannot be physical or legal violence, then it will be the violence of language and ideas, disguised as humor. This is what I call the KKK joke.

The pain of the KKK joke is so big you can’t even process it all at once—like how can’t you see the solar system, or even the planet, because of the overwhelming immensity. The pain of the KKK joke is that because you cannot name it directly, everyone else pretends not to see it, not to notice that it is there. The pain of the KKK joke is that no one defends you; you must be the one, yet again, to speak up and say: Racism is bad, please don’t do it; it hurts me. It hurts others.

The pain of the KKK joke chokes all the air out of your lungs like a handheld noose slung around a Black unbreathing throat and up over a tree on a hot, wet, American summer night.

*

Sometimes, driving on the highway here in Nebraska, I will see a burning—a wooden shape on fire—and I will think I must not have seen what I have seen. It could have been an accidental bush or twisted tree; maybe a scarecrow could account for that long crossed shape visible through the flames. It cannot be that other thing—my faith made weapon and set aflame.

The first time I was called nigger was in second grade. We had just moved to California. A white girl pushed me off the swings. She said she was named after the state where her people were from, where her daddy and uncles n’em in the KKK strung niggers like me up from trees so shove off, she said.

We learned where was safe.

Victorville. Palmdale. Central California—the central wide space that cuts between the liberal white north and the diverse warm south. These areas were off-limits. The KKK was there. We stayed away.

We know what it means when Robert Fuller and Malcolm Harsch are found strung from trees, one in front of city hall with racist graffiti scrawled close by; we know what it means when another Black teenager is found lynched in an elementary school in Texas just prior to Juneteenth or when, just afterward, the only Black driver in NASCAR, Bubba Wallace, finds a noose in his garage stall. We know what it means when, in the days after that, a Black teenage girl named Althea Bernstein is set on fire by a mob of white men she described as “typical Wisconsin frat boys.”

We know what it means when there is a civil rights struggle and Black bodies start showing up hanging from trees, when warning signs start showing up hanging from other places, and Black women’s bodies are violated with impunity by prowling white men. This is Black history that has never stopped being Black present.

And you can hear, if you listen, the pain of the KKK joke in the quiet sshhhhhh the trees make at night.

*

In 1918, one year before my grandmother was born, a young Black woman, eight months pregnant, was captured and beaten, then hung upside down from a tree by the standard mob of white supremacists of the time who set her on fire, then, growing bored, shot at her. They had already killed her husband. It is unclear at what point the white mob cut out her eight-month-old fetus from her stomach and beat the unborn Black child, bloody and senseless, into the ground, but reports say that when they did, the lynched and burned Black woman was still alive.

The woman’s name was Mary Turner. It is said the white mob targeted her because she had spoken publicly about her husband’s murder by white supremacists. How did they know this? The fact that Mary had been heard to speak was reported in the local papers—as were the actions of any other Blacks who tried to speak, own property, vote, or do anything that was deemed “uppity”—in order to assist the local KKK in bringing that “uppity Negro” to a violent end. This was the normal for Black folks in the South in that time.

Today, the tiny memorial to Mary and her unborn child embedded in the side of the road in Lowndes County, Georgia, is shot through with bullet holes from deer rifles fired by white men eager to kill something. This, too, is the normal for Black folks in America in our time.

*

The KKK, the abbreviation for the Ku Klux Klan, is the most famous and long-standing American white supremacist group. Founded by disgruntled ex-Confederate soldiers in 1865, within a year the KKK had begun a reign of terror against Black communities. Although briefly suppressed in 1872, the KKK resurfaced and continued to use lynching and intimidation—the burning cross and destruction by fire of Black businesses and homes—to terrorize Black families in America.

It is estimated that 6,500 Black women, men, and children were lynched in the United States during the years from 1865 to 1950, according to the latest report by the Equal Justice Initiative. During the twelve years directly after the American Civil War, Black Americans were lynched at the rate of one every other day. In the sixties, the KKK diversified into shooting and bombing. Among their most infamous acts of violence during the sixties are the murder of NAACP leaders Medgar Evers, Harry Moore, and his wife, Harriette Moore, all in their own homes, and the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four little Black girls.

We know the history of lynching as a terror tactic. How innocuous it was—regular Sunday-afternoon fun for white society, complete with picnics on the village green. We have seen, many times, the chilling pictures: the laughing, happy white watchers pointing at the Black hanging dead bodies as a job well done; the watching white children, learning this lesson well. The spectacle of the death of the Black body as a public warning—a tactic still very much in use today.

Because this history is our present, I can never get used to it. But I do not want to ever get used to it—I do not ever want to become so numb and beaten down by racism in America that the pain and rage of this strange fruit can become strange fodder to joke about instead.

*

There are always three violences. The first is the violence itself.

The second is the violence of not righting the original violence. This is, for example, the violence that lets Breonna Taylor’s killers still roam free; this is the violence that let the killers of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery roam free until public outcry led to their arrests; this is the violence that left Michael Brown’s murdered black body baking in the hundred-degree Midwestern summer heat for hours—something no American would let be done to a stray dog.

The third is erasure of the violence.

*

Sometimes, in the first uncertain moments between sleeping and waking, when I cannot tell if the liquid oozing from the trees is black sap or Black blood, I can hear the silenced stories of the lynched rising outward in the language of kinship—of blood and bone and memory—that cannot be denied.

*

This is the pain of the KKK joke: when you share your trauma from racist experiences in order to get people to care that Black lives matter, one of the people listening will make the KKK joke and will expect you to stay silent and take it—like you have taken everything else and stayed silent and then taken some more, for so long.

The pain of the KKK joke is that when you respond, you are attacked for speaking out against its racism rather than the racism that was said; you are made into a stereotype of an angry Black woman. But even though you are scared you have no choice but to speak; after living for a year in a domestic violence shelter with your newborn, the promise you made to yourself, upon leaving, was to never to let another man harm you again; to never let anyone or anything, even the white supremacy of the KKK joke and those who wield it, harm you again.

The pain of the KKK joke is the denial of the racism and white privilege that created it. The pain of the KKK joke is that it keeps weaponizing this violence.

*

But sshhhhhh, the trees still whispering. If you listen, late at night, they are telling the history of the KKK joke.

Hope Wabuke is a poet, writer, and assistant professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Philip Roth’s Last Laugh

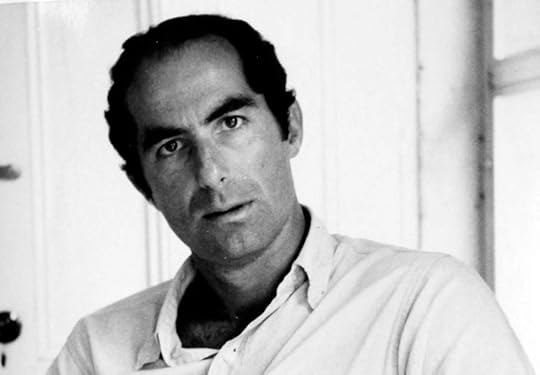

Philip Roth. Photo courtesy of Philip Roth.

April 24, 2018: “Brace yourself, Ben,” Philip calls to say. “Our beloved Meatball has been downgraded by the Health Department from A to B. This will ruin them! People see that sickly green B in the window and stay away.” I report having seen something still more shocking at the Pan-Asian hellhole two blocks up. “I know, I know!” says Philip. “They’re sporting a ptomainish, orange-colored C. A rat in a tuxedo greets you at the door.”

He’s on to the next thing and hangs up without goodbye. It is gratifying to hear him so exuberant. But five days later he phones to say he is “poorly”—one of his old-fashioned turns of phrase. I say I’ll stay with him that night at his apartment. Around two in the morning I hear him cry out from his room. He’s in trouble. I dial 911. Paramedics arrive with exemplary speed but have trouble defibrillating Philip. I can tell by the way they are talking that he could die. After an infinitely long minute or two his heartbeat reverts. We transport him first to Lenox Hill Hospital, then later that day to NewYork–Presbyterian, which he will never leave.

My routine for the next twenty-two mornings is to walk from my apartment to Columbus Circle and take the A train uptown to NewYork–Presbyterian. “What news on the Rialto?” he tends to say when I come through the door of his room. Anything can become an adventure, even a ride on the A train. One morning, a strapping young panhandler enters the sparsely populated car I’m in and says: “Ladies and gents! Ladies and gents! I am attempting to raise some funds, if any of you prima donnas care to help.”

I report this and Philip throws back his head. “Oh, Saul would have loved that! He’d have used it!”

“Frankly, I didn’t see any prima donnas on that train.”

“Unless he meant you, Ben.” It was to be our last laugh together.

*

“Ligt in drerd,” he used to say of anyone dead. “Lies in the ground.” He admired this blunt bit of Yiddish. “Pity our erstwhile mother tongue, spoken by Ashkenazim going back to the time of Chaucer and now reduced in America to stock phrases. A European language that produced a great literature, now consigned to Borscht Belt gags.”

Like him, I can’t help imagining loved ones lying in the earth, as Yiddish would have it—the slow processes going on down there, down where there’s nothing but what’s called in Sabbath’s Theater “the inescapable rectitude, not to mention the boredom, of death,” where you’re deprived of “the fun of existing that even a flea must feel.”

Saul Bellow was certain he would see his parents again after death. Philip Roth was as certain he would not. This is one way of assessing the difference between them. Who does not grasp the fierce impulse to believe? Consideration of all the ages before you existed provokes no shudder. Consideration of all the ages when you will no longer exist is simply unacceptable. How can this immense datum I am be extinguished? How can Mama and Papa be altogether gone—simply gone? How can it be that we won’t be together again? How can that be? When Prince Andrei dies in War and Peace Natasha turns to Princess Maria and says, speaking for all of us: “Where has he gone? Where is he now?” Philip’s solution was to rename mortality immortality and declare himself indestructible till death. It’s not a bad gloss on what’s always been the ultimate human problem.

Strolling past the Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle one spring day a few years back, we take note of the New York City Atheists, who’ve set up shop under a drooping tent with isinglass windows. Within are the washed-out unbelievers purveying their pamphlets and hoping to engage you in philosophical conversation.

“Why must the atheists’ booth look so sad?” Philip asks.

“Saint Patrick’s it ain’t.”

“The big money is behind the fairy tales. All those centuries of fairy tales.”

“Wish away the fairy tales and you wish away all the art, music, and poetry they’ve engendered.”

Whenever we’re walking and Philip has a thought, he’ll stop in his tracks. “Religions are the refuge of the weak-minded. I’d dispense with all the art, music, and even poetry they’ve engendered if we could finally be free of them.”

“The B-minor Mass? The Sistine ceiling? George Herbert’s poems?”

A dog walker comes past with eight or ten doggies of all sizes and shapes. “You see that?” he says. “Perfect concord among the breeds. The border collies admire the Heinz fifty-sevens. The Newfoundlands would make love to the dachshunds if they could. And why? Because dogs are wise enough to have no religion.”

“We had a certain amount of God talk at our house. ‘God knows whether you’re lying’ and that sort of thing. Was there no talk about him in your family?”

“None, fortunately. Our Zion was the United States. Our divinity was Franklin Roosevelt. My mother lit Friday-night candles, true, but only out of piety for her own mother.”

“I think the Romantics got it right,” I say. “They announced that God and the Imagination are one. If I had to declare a religion when passing through customs, that formula would be it.”