The Paris Review's Blog, page 160

June 23, 2020

Redux: When They Could Have Been Anything

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

George Saunders. Photo: Chloe Aftel. Courtesy of George Saunders.

This week, we’re thinking about fatherhood and Father’s Day. Read on for George Saunders’s Art of Fiction interview, Jonathan Escoffery’s story “Under the Ackee Tree,” and Louise Erdrich’s poem “Birth.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

George Saunders, The Art of Fiction No. 245

Issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

INTERVIEWER

Do you think you’d be a different writer if you hadn’t had children?

SAUNDERS

For sure. I’m not sure I would have ever published anything. Before we had our kids, I was a decent person, kind of habitually, but nothing felt morally urgent. Then the kids came, and everything suddenly mattered. The world had a moral charge. If I love these guys so much, it stands to reason that every other person in the world has somebody who loves them just as much—or they should have someone who loves them as much. The world was full of consequence. That which helps what you love is good, that which hurts it is bad, and even a small hurt is significant. You see somebody come into the world, tiny and brand new and blameless, and you’re like, That person deserves the best. So, by implication, everybody deserves the best.

Under the Ackee Tree

By Jonathan Escoffery

Issue no. 229 (Summer 2019)

You name your second son Trelawny to remind yourself of home. It long enough after you reach that you miss JA bad-bad. You miss walk down a road and pick Julie mango off street side. When you try pick Miami street-side mango, lady come out she house with rifle and shoot your belly and backside with BB. In the back of your Cutler Ridge town house, you start try grow mango tree and ackee tree with any seeds you come by, but no amount of water or fertilizer will get them to sprout.

Birth

By Louise Erdrich

Issue no. 111 (Summer 1989)

When they were wild

When they were not yet human

When they could have been anything,

I was on the other side ready with milk to lure them,

And their father, too, the name like a net in his hands.

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives.

On Translationese

Haruki Murakami and Kenzaburo Oe. Murakami photo: © Elena Seibert.

I clearly remember the vivid colors of the two books—one red, the other green—that a high school classmate of mine was reading between periods. It was 1987 or 1988, and my new school was in a provincial city in Oita, Japan. This quiet, introspective classmate was one of the first handful of students from the city to be kind enough to talk to me. I was from a small fishing village that didn’t even have a bookstore, and having come from a junior high school with fewer than forty students, I was intimidated by how he already had clear taste in music and literature. I can’t remember if he mentioned—in his always nearly inaudible voice—the title of the two-volume novel or the author’s name. What I do remember is that he seemed engrossed in the book, and that less than a year later, his life was taken: his mother’s partner killed her before turning to the boy.

The next time I encountered those books was after I moved to Tokyo for university. I came across a large stack of them right by the entrance of one of the city’s largest bookstores. They were the two parts of Haruki Murakami’s novel Noruwei no mori (Norwegian Wood). I was already familiar with him as a master of short essays. My landlady had the bad (or good?) habit of reading books in the bathroom, and Murakami’s essays were among her favorites. One day, she handed me a collection she had finished. In these essays, he writes about literature and music and even cooking in such a natural way that it feels as though he’s addressing the reader personally. Something delightful and friendly in his style fascinated me (it’s a shame that those early essays of his haven’t been published in English). I couldn’t say how exactly, but I immediately felt that his style was different from other contemporary Japanese writers I had read. Probably because one of my professors (who was from Belgium) had translated it into French, A Wild Sheep Chase was the first of Murakami’s novels I read. And I soon found myself reading through them all.

*

In 1978, Murakami went to Jingu Baseball Stadium, located near the jazz bar he ran, to watch the opening game of the season. The moment the lead-off hitter slammed the first pitch cleanly into left field, a thought struck him: I think I can write a novel. Murakami describes this experience as follows in Novelist as a Vocation, the passage here translated by Ted Goossen for the foreword to Wind/Pinball:

I can still recall the exact sensation. It felt as if something had come fluttering down from the sky, and I had caught it cleanly in my hands. I had no idea why it had chanced to fall into my grasp. I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now. Whatever the reason, it had taken place. It was like a revelation. Or maybe “epiphany” is a better word.

Murakami describes this event—even in Japanese—using the English word epiphany. Late that night, he sat down at the kitchen table and began to write. Several months later, he finished a first draft. But it disappointed him. Murakami placed his Olivetti typewriter on the table and began to write again, this time in English.

The resulting English prose was, unsurprisingly, simple and unadorned. However, as he wrote, Murakami felt a distinctive rhythm begin to take shape:

Since I was born and raised in Japan, the vocabulary and patterns of the Japanese language had filled the system that was me to bursting, like a barn crammed with livestock. When I sought to put my thoughts and feelings into words, those animals began to mill about, and the system crashed. Writing in a foreign language, with all the limitations that entailed, removed this obstacle.

It may seem paradoxical that his mother tongue prevented him from writing. But writing in a foreign language liberated him, and he finished the beginning of his novel in English before translating it into Japanese:

What I was seeking by writing first in English and then “translating” into Japanese was no less than the creation of an unadorned “neutral” style that would allow me freer movement. My interest was not in creating a watered-down form of Japanese. I wanted to deploy a type of Japanese as far removed as possible from so-called literary language in order to write in my own natural voice.

The style Murakami describes as “neutral” was deemed by some critics “translationese.” When Murakami became a success in the global literary market, Kojin Karatani—one of the most influential Japanese critics—attributed this success to the “non-Japaneseness” of Murakami’s style.

*

I wonder why I felt that Murakami’s writing was so natural and atmospheric when I first read his work. The writing did not feel like translationese to me at all. Rather, I had a strong feeling that his Japanese was our Japanese, one that I also lived and breathed. I was struck by the fact that one could write a novel in that kind of language. When reading Murakami, I never experienced the difficulty or resistance I felt each time I read Kenzaburo Oe’s later novels, which were written in a highly elaborate style that I considered “literary.”

Like Oe, though, when I began writing my first novel, it felt like a natural choice to set the story in my hometown. On a clear day from the town where I was raised, you can see Shikoku island, where Oe’s hometown is located. I’ve always been encouraged and inspired by the fact that Oe has continued throughout his career to write stories set in his hometown. And I’m strongly drawn to the original and imaginative way in which he develops local myths and small histories (in both senses of the French word histoire: history and story).

I’ve heard that Oe didn’t much appreciate Murakami’s early books, but when Oe made his debut in the late fifties, his writing style was also considered translationese. In an interview with Oe, Karatani said: “Your early works were among the first contemporary Japanese novels I read. Your writing was very new to me. It felt very close to the Japanese used in translation; for example, the Japanese translations of Pierre Gascar or Norman Mailer.” Oe’s early works were so spontaneous and vivid that he quickly gained a huge audience, especially among young people. But the sensual nature of his first few books was gradually replaced by an intellectually elaborated style, one that also has been described by critics as translationese.

So while Murakami’s translationese makes him clearer and more natural, Oe’s translationese makes him more difficult and more artificial. However, according to Karatani, Oe’s clearer and more natural early work was already translationese, too.

*

In Novelist as a Vocation, Murakami says he developed his own original writing style, little by little, specifically by reading foreign novels—either in translation or in the original. He has also said that, having read very few Japanese novels, he didn’t have a firm idea about what a Japanese novel was when he first tried writing one himself.

Oe, on the other hand, said he was largely influenced by Japanese writers in the postwar era, but over time, he became less interested in Japanese fiction and began to read foreign books in their original languages. Generally, Oe is considered in Japan to be influenced by the French. In Oe’s early works, there are resonances of his reading of French existentialism. But Oe’s English influences are also clear: his close reading of English poets like William Blake, William Butler Yeats, Edgar Allan Poe, and T. S. Eliot occupy an essential role in his influential autobiographical novels.

I don’t think anyone would object if I said Oe and Murakami are the two novelists that represent contemporary Japanese literature from the end of the war through the present. Is it surprising that reading foreign literature in the original played a crucial role in their literary development? They are always writing through the experience of the “foreign.” As Proust said: “les beaux livres sont écrits dans une sorte de langeue étrangère (beautiful books are written in a kind of foreign language).” Even if Oe and Murakami seem to be writing in Japanese, they might truly be writing in some kind of foreign language.

*

Historically, the modern Japanese novel has its origins in encounters with Western novels, with foreignness. And for more than thirty years, Murakami—who has translated novels and short stories by American writers throughout his career—has been the cornerstone of Japanese literature. Thus, the Japanese literary field at this moment is heavily influenced by American literature—as if in direct proportion to Murakami’s dominance.

Despite this reality, very few contemporary Japanese novelists read foreign novels—even American or British fiction—in the original. I get the sense that they perhaps don’t feel it’s necessary, since they are able to read a wide range of foreign novels in Japanese translation (translators of literary fiction are relatively well respected in Japan and are considered connoisseurs whose opinions and tastes matter). It is notable, though, that two of Japan’s most exceptional contemporary writers do operate between languages: One is Yoko Tawada, whose The Emissary, translated into English by Margaret Mitsutani, won the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2018. Tawada writes in German as well as in Japanese. The other is Minae Mizumura. When she was twelve, Mizumura moved with her family from Tokyo to Long Island, New York. After studying fine art in Boston and then living in Paris, she went on to study French literature at Yale. Interestingly, she defines herself as a modern Japanese novelist and writes in Japanese.

*

It’s hard to say exactly how and to what extent Murakami’s style has influenced contemporary Japanese writing. I also cannot say with any certainty how and to what extent Oe’s reading of foreign poems in their original language has influenced the creation of his literary style. But it is clear that their experiences with foreignness have been vital to their own work. Notably, Oe developed the cosmology of his homeland in the forest on Shikoku island, far from Tokyo, where he lives. He creates a symbolic opposition between his homeland, a small, local culture with a rich oral and popular tradition, and Tokyo, the center of modern Japanese national culture that has tamed and dominated its diverse peripheral cultures. This fact reminds me of how Cahier du retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), one of the most important books in French Caribbean literature about “home,” was written when Aimé Césaire saw a small island on the Adriatic Sea from a shore in Croatia, thousands of miles away from his home on Martinique. Or that Murakami wrote Norwegian Wood when he was living in Greece and Italy, and that he first began writing his chef d’oeuvre The Wind-up Bird Chronicle in Princeton, New Jersey.

When I was writing my own novel, Echo on the Bay—recently translated into English by Angus Turvill—I was living in Orléans, France. My landlord was the French poet and critic Claude Mouchard, and from the window of my second-floor flat I had a view of his expansive garden featuring every kind of tree—cedar, walnut, linden, cherry, apple, peach, pear, apricot. The summer garden filled with green leaves reminded me of the sea of my hometown. In that garden, a year before, Claude and I had finished a French translation of a long poem by the Japanese poet Yoshimasu Gozo, who also writes in, and across, multiple languages.

It was there, in Orléans, that I began to translate into Japanese Foucault, Glissant, Naipaul, and Marie NDiaye. I feel now that without this effect of distance—geographical distance from my hometown and linguistic distance made possible by it, as well as the in-between space opened up by the act of translation—I couldn’t have written my novel. This distance made it possible for me to see the place and people of my native land in such a vivid way that wouldn’t have been possible if I had been in Tokyo. I am convinced that, like in Murakami and Oe’s work, the in-between space of translation and complete detachment from Japanese helped me to be more sensitive to the language than when I was surrounded by it—or perhaps it allowed me to find my own kind of foreign language.

Masatsugu Ono is the author of numerous novels, including Mizu ni umoreru haka (The Water-Covered Grave), which won the Asahi Award for New Writers, and the Mishima Prize–winning Nigiyakana wan ni seowareta fune, which was published in Angus Turvill’s English translation as Echo on the Bay earlier this month. A prolific translator from the French—including works by Èdouard Glissant and Marie NDiaye—Ono received the Akutagawa Prize, Japan’s highest literary honor, in 2015. He lives in Tokyo.

Essay written in English by the author and revised by David Karashima and CJ Evans.

If you enjoyed this essay, why not read:

The Art of Fiction No. 195 with Kenzaburo Oe, published in issue no. 183, Winter 2007?

The Art of Fiction No. 182 with Haruki Murakami, published in issue no. 170, Summer 2004?

“Heigh-Ho,” by Haruki Murakami, published in issue no. 172, Winter 2004?

We Picked the Wrong Side

When I was in the sixth grade, I met a girl named Nicole. Nicole was a good student; she was polite to teachers. She was in the gifted program, a group of students handpicked for their exceptional promise. I was not in the gifted program. When my mother found out I had not been chosen, she became furious. She wanted to know why I was not worthy and how I might prove otherwise. I suppose this was her mistake—she assumed I was better than I actually was. Over time, Nicole and I became friends. We sat next to each other in class and gossiped during lunch. We watched horror movies on weekends. When boys made fun of me for being queer, she jumped to my defense. If I hadn’t been paying attention in class—which was often—she passed me her notes. Sometimes I imagined what it was like to be Nicole, with her spotless record, her enviable grades. I imagined what her teachers said during parent-teacher conferences, all the glowing, effusive praise.

It must have been the opposite of what they said during mine. I talked too much. I didn’t pay attention. My homework was always late. Sometimes I said I had turned in an assignment when really I had not. I would complete the assignment later and step on it with my shoes—this gave it the effect of some mysterious trauma—and drop it on the floor by my teacher’s desk, as if it was her fault she had lost it and not mine. I was diabolical. I impersonated my father to call myself out of school. I cut class and went to the mall. I intercepted the mail to hide my grades. I pretended to be good when I was not. Nicole didn’t do those things. She didn’t have to cover her tracks; her steps were always measured, taken with great care.

“Why can’t you use your brains for good?” My mother once complained. “Just look at Nicole.”

I spoke of Nicole often, how smart she was and how good her grades were, how she wanted to become a doctor just like my dad. “Wow,” my parents would say, masking their own disappointment in me. “Look at that.” While Nicole was graduating from medical school, I was still unsure of my place in the world, aware of the expectations I had failed to meet. Because Nicole was everything I was supposed to be, the opportunities I had squandered, the chances I’d let slip. In a way, my failure was similar to her success; they both came as a surprise. Because I’m a South Asian. And Nicole is Black.

To say I never saw Nicole’s Blackness would be a lie. To say I never heard the narrative of Blackness in America would be an even bigger one. Though we didn’t speak of race often, I knew what my parents had been told about Black people in America. It was on the news, in movies, tucked into conversations at the table. A story of danger. Fear. I had witnessed car doors locking, purses being hugged. I had heard white people describe an unpleasant encounter with someone before saying “she was Black,” as if this was what they had meant to say all along. The danger of Blackness was their central thesis. They supported it at every turn. I had heard these stories, had grown weary of these stories, had fallen victim to these stories myself. I knew what my mother meant when she said, “Just look at Nicole.” I also knew why I talked about her achievements so much at home: her race was the subtext. I wanted to show that she was good.

*

When I was young, my father had been watching the news in the doctors’ lounge with a white doctor when a crime was reported. The suspect was Black. The white doctor shook his head.

“See that?” he said, turning to my father. “We should have never brought them here.”

My father was stunned. He had never discussed Black people with this doctor before. This doctor had no idea that my father had been born and grown up in Nairobi, Kenya. He saw only that my father was not Black. Perhaps he assumed my father would agree with him—or worse, he assumed my father could be persuaded to agree with him. It’s the kind of imperious attitude only a white person could have.

When my father told me this story, I immediately thought of Nicole. I became enraged. I asked him how anyone could say such a thing. Then I asked him what I had been afraid to ask all along.

“What did you say back?”

*

Many years later, I was on a date with a white man at a bar. It was 2014, shortly after the inception of Black Lives Matter. During the course of our conversation, the topic shifted to race. I was immediately uncomfortable. Race was not something I had wanted to discuss on a first date, especially with a white man. But he persisted, explaining that he wasn’t racist at all—he believed in equality—he just felt Black people needed to get over things. Then he told me a story about his uncle’s store in Mississippi, which had been robbed by three Black men. It wasn’t so much his choice of words that echoed, but the careful layering, the casual way in which he unfurled them. He was telling a story. A story of Black danger. I was shocked. This man was my age. He did color runs and drank kombucha. He was gay. Later, he told me he had many South Asian friends. He knew all about my culture. He loved Indian men. I knew in that moment why he had told me this story. He assumed I already believed it.

A month later, I was at a train station in Chicago when an Indian man approached me, telling me he had been robbed. Two Black men had attacked him and stolen his wallet. He needed train fare and food. I gave him twenty dollars. He thanked me and walked off. Later, I felt good about what I had done. I called my mother and told her what happened. I walked away from that station feeling absolved of my sins, like I had the power to make a difference in the world, like I could be good, too.

Three weeks later, I saw him again. This time it was outside a bank. He approached me with folded hands. He told me he had been robbed. He said two Black men had attacked him and stolen his cash. Every detail was the same. After I told him I had already heard this story, he shrugged and walked off, prepared to tell it to someone else. What struck me then, what still strikes me today, was his choice of words: two Black men. He didn’t need to describe them; I was not a police officer writing a report. This man knew the narrative of Blackness in America and understood the credibility it lent him. He may have been in America only a few months, but that was all it took to absorb the racism in the air.

*

The problem with the narrative of Black danger is that it has normalized Black death to the point where we regard it as an inevitable consequence of the stories we’ve heard. Gangs. Violence. Men with guns. But after witnessing the tragic deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, after hearing the story of Amy Cooper and Christian Cooper in Central Park, after numerous memes and video clips and pleas, we’re ready to hear a different story. We’re shifting the lens back onto us.

A few days ago, I watched a video of a South Asian man urging our community to reframe our narrative. After explaining the impact the civil rights movement had on our immigration, after reminding us that our success in America was by design (post 1965, only the highest-qualified Indians were allowed to immigrate to the U.S.), after condemning the rampant anti-Blackness among South Asians, the racism, the denial, he ended his diatribe with two powerful words: wake up. And we did. Now, as I scroll through Instagram, I see step-by-step instructions on how to combat anti-Blackness in our own spaces. I see a video of Hasan Minhaj urging us to get involved. I see signs that read SOUTH ASIANS FOR BLACK LIVES. I see brown people protesting for the safety of Black people. It’s inspiring to witness, but I can’t help but remember the countless other lives that were lost along the way, and I have to ask: where were we then?

*

I was at a wedding hosted by a wealthy Indian family in the Northeast, an event that served oysters nestled in ice, paella in giant pans, and sparkling flutes of champagne, when a guest, an Indian man, swept his hand across the scene.

“You see,” he said, his eyes glistening. “We are just like the whites.”

I was amused. The man proceeded to tell me that his house, compared to the elegant home we were presently outside of, was larger in size. Then he told me he owned a successful medical practice, and he did very well. I didn’t know then what I know now, that his success, like many other Indians’, came at a cost. That while Indians were minting money from practices all over the nation, Black kids, capable and smart, were being discouraged from even applying to medical school. That in one generation, South Asians have amassed generational wealth—businesses, investments, homes, the kind of wealth that grows—while many Black families who have been here for centuries have nothing to pass on. I hadn’t seen the videos on systemic racism that now circulate the web, explaining the unjust ways in which neighborhoods have been zoned, home loans denied, résumés with Black-sounding names driven to the bottom of the pile, all while South Asians rub elbows with presidents and CEOs. I didn’t think about how fortunate I was to be a guest at that wedding in the first place, crossing paths with well-connected people who could take me far in life. What I did know, in spite of my ignorance, was that I felt sorry for that brown man. At some point in his life he had been told a story of whiteness—a story of power—and he thought he could write himself into it.

*

As a child, I never considered myself privileged; I’m brown and gay. When I finally came out of the closet in 2012, shortly after Trayvon Martin was killed, I expected it to be met with backlash from the South Asian community. It was not. By then, it was deemed cool to be gay. So why did anti-Blackness still exist among South Asians? Why were we still locking our doors and using the N-word and forbidding our children to date Black people? Black people are the ones who built the America our parents crossed oceans to reach. So why have we placed new oceans between us? Because being gay, like being rich, is centered around whiteness. Being Black is not.

*

There have always been those who are in power and those who are not. And there have always been those in between, whose standing could shift up or down depending on whose company they kept. We are those people. We made our choice as far back as the lunchroom, where Black kids sat on one side and white kids on the other, and at recess, where Black kids played double Dutch while white kids sat on the lawn.

Taking directions from white people is nothing new for South Asians; it stems from colonialism. My father still remembers the time he was accosted by a white officer in Kenya for walking through a neighborhood that was allegedly white. He still remembers the haughty way white doctors spoke to him during his training in London. He still remembers the time a white patient walked into his office and, upon realizing my father was brown, immediately walked out. Still, he endured, knowing it was a means to an end: the house, the cars, the security. White people could provide that. Throughout time, we have pandered to white people, ingratiating ourselves with them. We have shared their spaces and held their jobs. We’ve even claimed to be them: in 1923, a South Asian man, Bhagat Singh, petitioned for naturalization under the Naturalization Act of 1906, claiming to be Caucasian. The petition was denied. We have come to view white people, even colleagues, as authoritative figures. We defer to their opinions. We don’t make waves. When that man at the train station told me “two Black men” had robbed him, I believed him. When that brown doctor said, with a gleam in his eye, “We are just like the whites,” I said nothing. When my father’s white colleague made an anti-Black comment in the doctors’ lounge, my father, too, said nothing.

*

Though we’ve drifted apart, though our phone calls are less frequent, our movie nights have ended, and the gossip has stilled, Nicole and I do keep in touch, texting every now and then. Our lives have taken different paths: Nicole is a doctor and married with kids; I live alone and write for TV in LA. The last time we had texted each other, recently, was to discuss a very old picture of us Nicole had sent. It had been taken after a Janet Jackson concert. We laughed at how young we looked. I told her I couldn’t wait to see her at our twenty-year high school reunion. That was eight months ago. The next text was from me, a stilted, fumbling message I would later regret. I told her I was thinking of her, and that I hoped she was finding some peace. It’s the kind of bland text you send to an acquaintance who is grieving a loss. I would have said more, should have said more, but I couldn’t find the right words. I sent the text, then I posted a link to the Minnesota Freedom Fund, an organization providing bail money for protestors, on Instagram. An hour later, my mother texted me: “Don’t get too involved.”

Later, my mother explained that she was afraid of what might happen if I did, considering the people I work with are white. Because my mother, like my father, has seen what whiteness can do: rewrite our futures, erase our pasts. In spite of what she and many others like her have been told, in spite of the narrative of Black danger in America, in spite of TV shows and news reports and whispers from white neighbors, my mother’s true fear was revealed. It’s not the story of Blackness she was scared of after all. It’s the people who wrote it.

Neel Patel is the author of the short story collection, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi, and the forthcoming novel, Tell Me How to Be. He lives in Los Angeles, where he writes for television and film.

June 22, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 14

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

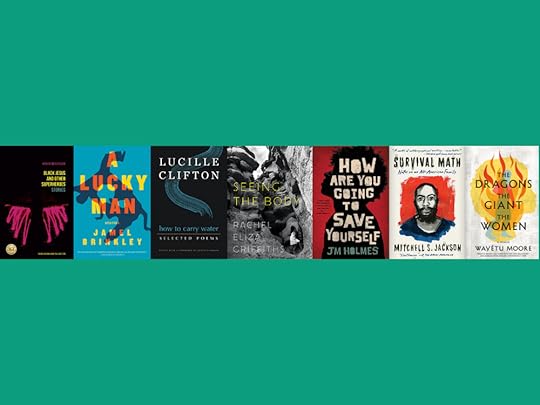

“This installment of The Art of Distance is inspired by the past week’s #BlackoutBestsellerList campaign, which encouraged book buyers to purchase two books by Black authors in order to fill best-seller lists with Black voices. Unlocked this week are seven pieces from recent issues of The Paris Review by Black writers who have also recently published books. If you enjoy this writing, we hope that you will consider buying these authors’ novels, story collections, and nonfiction works. We wish you a week of meaningful reading and hope you stay safe, sane, and engaged.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Read these stories, poems, and essays by TPR authors, and then check out their new, recent, and forthcoming works linked below.

Venita Blackburn’s “Fam” (issue no. 226, Fall 2018) is a haunting glimpse into the social media life of a teen whose past is shadowed by family violence. Her debut story collection, Black Jesus and Other Superheroes, won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize for fiction, and Blackburn was a finalist for both the PEN/Bingham Prize for debut fiction and the Young Lions Award from the New York Public Library.

“Witness,” by Jamel Brinkley (issue no. 233, Summer 2020), is a sobering examination of race and health care in America. Brinkley’s story collection A Lucky Man was a finalist for the National Book Award.

Two unpublished poems by Lucille Clifton, “poem to my yellow coat” and “bouquet,” appear in issue no. 233, Summer 2020. They’re drawn from a group of unpublished poems that will be included in How to Carry Water, a career-spanning selection of Clifton’s work due out in September.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s poem “Hunger” (issue no. 232, Spring 2020) is a searing elegy for the poet’s mother that wrestles with and takes inspiration from a kind of magical thinking. The poem comes from her just-published collection of poetry and photography, Seeing the Body.

Told largely in rapid-fire dialogue, J. M. Holmes’s “What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?” (issue no. 221, Summer 2017, and The Paris Review Podcast Episode 16) barrels toward a shocking revelation about racism and sex. The story appears in his first book, How Are You Going to Save Yourself.

Mitchell S. Jackson’s essay “Exodus” (issue no. 226, Fall 2018) begins in “the wilderness of my hometown” and ends at the foot of the stairs of “what would be my new home.” It opens into a story of life marked by violence and addiction that continues in his memoir, Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family, which was named one of NPR’s favorite books of 2019.

The protagonist of Wayétu Moore’s “Gbessa” (issue no. 225, Summer 2018) is deemed a “cursed” child by the people in her town and must suffer their derision and blame for circumstances beyond their control. “Gbessa” became the first chapter of Moore’s debut novel, She Would Be King. Read an excerpt of her new memoir, The Dragons, the Giant, the Women, on the Daily.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

From Woe to Wonder

Gwendolyn Brooks, in a 1977 interview, describes an ongoing argument with her husband about the fate of a running Black child:

Once we were walking down a road and we saw a little Ghanaian boy. He was running and happy in the happy sunshine. My husband made a comment springing from an argument we had had the night before that lasted until four in the morning. He said, ‘Now look, see that little boy. That is a perfect picture of happy youth. So if you were writing a poem about him, why couldn’t you just let it go at that? Write a poem about running boy-happy, happy-running boy?’ […]

So I said if you wrote exhaustively about running boy and you noticed that the boy was black, you would have to go further than a celebration of blissful youth. You just might consider that when a black boy runs, maybe not in Ghana, but perhaps on the Chicago South Side, you’d have to remember a certain friend of my daughter’s in high school—beautiful boy, so smart, one of the honor students, and just an all-around fine fellow. He was running down an alley with a friend of his, just running and a policeman said ‘Halt!’ And before he could slow up his steps, he just shot him. Now that happens all the time in Chicago. There was all that promise in a little crumpled heap. Dead forever.

*

For every sorrow I write, also I press my forehead to the ground. Also I wash the feet of our beloveds, if only in my mind, in the waters of the petals of the flowers.

I cross my arms and bow to you.

I cross my arms in armor wishing you protection.

*

On August 23, 2014, I joined thousands to march for the life of Eric Garner and against the police who murdered him one month before. The blastocyst that would become my son was multiplying inside my darkest me unbeknownst to me.

Time moved through us. It is now 2020. Ramsey Orta, who filmed Garner’s death and bravely shared that record, is imprisoned on trumped-up charges and beaten by guards. Eric Garner’s eldest child, the activist Erica Garner, has passed at the age of twenty-seven from an enlarged heart after giving birth just three months before.

It is summer, then all the leaves are falling. My kids are two and four, then they are nearly three and nearly five. My son’s birthday, now I know, falls between the birthdays of young Ahmaud Arbery and the poet Kamau Brathwaite. I hear Gwendolyn Brooks: “You just might consider that when a black boy runs…” My partner and I teeter in that argument between Brooks and her husband, our own sight touched by both things: the happy in the happy sunshine and the policeman saying halt. We dance in the circle following both these men—Ahmaud Arbery, ever-becoming, and Kamau Brathwaite, the elder, who wrote in Elegguas:

How all this wd have been one kind of world. perhaps—no—certainly—

kindlier—you wd have been bourne happy into yr entitlement of silver hairs

and there wd have been no threat

My partner and I do not yet speak to our children about racism and such threats here looming. We speak of justice, diversity, fairness. The kids love the story of Malcolm Little: The Boy Who Grew Up to Become Malcolm X. They read a little at first, then a little more. We give them the large brushstrokes of the burning house, but we talk for long about Malcolm’s brilliant family, their commitments and work, the ladybugs in the garden. In Mae Among the Stars, when the teacher dismisses Mae’s dream to become an astronaut, our son is shocked. “Why would a teacher say that to a child?” He asks this very question, out of what seems to us the blue, over several weeks, then months. We do not mention that the teacher is White. We do not mention that the people who burn Malcolm Little’s house are White.

My partner and I talk to other Black parents, including our own. We get advice, ask questions, work and think about how to nourish and fortify our children. It does not occur to us to talk to our kids about Whiteness just yet, but increasingly I think we must. For example, I am startled, in February, by my son’s White schoolmate who runs into the hall to announce to his parent that Martin Luther King Jr. was killed because of the color of his skin. These months later I am again startled by the very young White children who speak openly and, it seems, without fear about George Floyd’s murder.

We are on a Zoom call with my child’s class. One of his White classmates has gone to a march with her family, in the middle of a pandemic, to march for Black Lives. The power of this is not lost on me. I am moved by their family’s investment and risk, a risk I do not take. I study the child’s face. The baby still in her voice, her cheeks, the way she holds her mouth. She says, “George Floyd was killed because…” And I click the sound off. My youngest says, “I can’t hear, Mommy.” Just a second, I tell them both, just a second.

The rest of that sentence might go a hundred different ways, might say something about the brutality, profit, and racialized terror on which the police state is founded, but this is not the sentence I expect. The sentence I expect is a variation on a theme: George Floyd was killed because of the color of his skin. People are mistreated because of the color of their skin. George Floyd was killed because his skin was brown.

Our skin is brown.

We stand in the light of the sentence but the perpetrator is under cover, cloaked. But by what, and in whose service?

It occurs to me in an instant that we have insufficiently prepared our child for the threat inside this fog.

I imagine a seesaw. My children are on one side and this White child, my son’s same age, same height and weight, is on the other side. She is one child, my children are two. And yet they are the ones hovering in the air, ungrounded. He was killed because his skin was brown. So goes the sentence that holds my children, dangling and subject, and that grants the White child her ground, her safety, her natural habitat, and close-to-the-earthness. The consequences of White supremacy are named only in terms of my child’s suffering or potential suffering, named only in terms of the suffering of our beloveds, but not in terms of the causes, the perpetrators, the inheritors, not in terms of the consequences on the minds of the White children who have already been failed, have already been taught wrongly to stand outside of the equation with their families.

Our son already knows the basic principles of physics on which a seesaw is designed. He knows that one and one is two. He knows: from the chicken, the egg; from the apple tree, the apple; and so on. So why should we teach him such a distorted logic that goes out of its way not to name the other subject in the sentence? If we do, the sentence itself becomes a kind of captivity. If we do, he will have no chance of knowing what it is he’s trying to get free from, and White children, too, will think the problem is out there, someone else’s, even his, and not the water they drink, the cleanish air they breathe.

Gwendolyn Brooks writes, in this excerpt from the persona poem “The Near-Johannesburg Boy,” written during apartheid:

My way is from woe to wonder.

A black boy near Johannesburg, hot

in the Hot Time.

Those people

do not like Black among the colors.

They do not like our

calling our country ours.

They say our country is not ours.

Those people.

Visiting the world as I visit the world.

Those people.

Their bleach is puckered and cruel.

She begins to pull Whiteness into the frame. And there is something here for us I think.

When a White person with a White child points to my child, even lovingly, as an example of a Black life who matters, I would also like that person to teach their White child about White life and history, and about how they are going to have to work really hard to make sure that they are not taking up more air, more space, more sidewalk because they have been taught wrongly that the world is more theirs. I would like to give my five-year-old words so that when he is told “George Floyd was killed because his skin was brown,” he is able to say something like, “Well, actually, there is an idea called Whiteness. Some people think that they are better and deserve more of everything because they are White and their ancestors are from Europe. Their ancestors hurt people and hurt the land to get the power that they gave to their children and that their children keep keeping, and keep using to hurt, even today. Isn’t that terrible?”

I want him to be able to say something like, “Those people. Visiting the world as I visit the world.”

*

This spring, we are, in our apartment, two kids and two parents, always together. By the time the last minutes of Ahmaud Arbery’s life are all over the internet, and we have begun to mourn the news of police officers killing Breonna Taylor inside her bedroom, and the news of the police murdering George Floyd, and the people, including children small as my children, have begun marching in the streets, my son and his sister are in their parent’s skin again, consuming only what we want them to consume. For a few months nobody, not even the puppets on Sesame Street, say in front of our children, “He was killed or she was killed or they were treated unfairly because of how they look or act or who they are.” There is a little more time to work on our children’s armor before they go again out into the further world, which, yes, we also love and want them to be in. We want them in the world with our family. We want them running in the sunlight with their laughing friends.

Ahmaud Arbery. Breonna Taylor. George Floyd. I move fast through the house, then slow, trying to listen for my mothers. The kids and I spend an afternoon boiling peony petals in water, then they take turns mashing them in the pilón. We wash the paper in the pigment and the color goes from a nearly invisible violet to a purple so strong it is like medicine. It gets darker and darker through the night, even in our sleep. They know this now. And they know how to pull the smoke over their heads in blessing. But more protection, more. And not just protection, also truth, also dreaming. Violet inside the petal. Purple inside the violet. Truth inside the purple. Dreaming inside the truth. Freedom inside the dreaming.

*

Time repeats through us. Time moves. My son was born, then he was two, and then my daughter was born. This spring they are almost three and five. In April I begin to say, as I do each year, “Right about now we were getting ready for you to be born. My stomach was enormous. My heart was pumping so much blood. The buds were bursting from the trees. The grass was high and green.” I do not mention Eric Garner. I do not mention Mike Brown or Tamir Rice. “Five years ago now we were getting ready.” I do not mention Walter Scott. “Papa put the stroller together, we went on walks, we were followed by a squirrel. We waited for you to be born.” He likes to hear this story and asks questions about the squirrel, the dark, the ice cream, the blood. He asks for all kinds of details from his gestation.

This year we go to the marsh. It is cold and so windy that almost no one else is out there, so we take off our masks and turn our backs to the wind. What was here before us? Who was here? What is here still though we maybe cannot see it? We are teaching the children to ask. This is Lenni Lenape land. There was a wilderness once. When the Dutch arrived in the seventeenth century, they began their colonial project by waging war with the land and its people. The tide is high, and we do not see the crabs or clams or snails, but we know that they are there.

Days later, it is warm again. The kids move up and down the marsh quietly seeing what they can see. The scurrying of the crabs. Their father says, “Gentle, gentle, you don’t want to frighten them.”

*

When I was eleven, I watched a crab scurry upright and frantic across the cobblestones in a small plaza in Colima where my aunt lived. I remember still its panic, how I felt seized by it somehow. With it I shared a skin. I swear, I thought something like, “You are my ancestor. I am you. Until I learned to also become the one who hunted, no longer feeling for your loss of life. At first I said, no, no, and was so sad, crying and snotting into my hands. My parent told me, Shh, eat, because we were hungry, and so then eventually I did. I began to eat your meat not just out of hunger but out of greed, without thanks, without prayer, without guilt, as something to do.”

*

My way is from woe to wonder.

A black boy near Johannesburg, hot

in the Hot Time.

Those people

do not like Black among the colors.

They do not like our

calling our country ours.

They say our country is not ours.

Those people.

Visiting the world as I visit the world.

Those people.

Their bleach is puckered and cruel.

I try to follow the boy from woe to wonder, but these years move often from wonder to woe. It is the thing that animates my quiet. It blazes like lightning through all of my branches. Wonder to woe. LaQuan McDonald, age seventeen. Kwame Jones, age seventeen. Trayvon Martin, age seventeen. Ramarley Graham, age seventeen. Tamir Rice, age twelve. Aiyana Mo’Nay Stanley Jones, age seven. Given names by their families. Names to be called from another room. Names to be taught to write and read. Names to, maybe, be shouted in a circle while their beloveds clap and clap for them to dance.

*

Woe to wonder. Needing to survive and to survive—my country—for my children: Get up. Put the water in the pot and boil the egg. Wash the faces. Empty the trash. “Where are your shoes?” I say. “Let’s count your fingers. Mommy loves you,” I say, and across our lines I hear the other mothers coming through.

My mother, for example, used to tell us, “Death and life is in the power of the tongue.”

Death and life, our mother said, about any number of things and in any number of ways. Part of what I understood was that language could help us to live and could help us to die. That rebuking Satan and anointing our heads and house with oil actually meant something. Whether Satan lasted was not the point, though, yes, we wanted Satan gone. The point was she was teaching us to fight.

*

This spring our son begins to read. He works on words, their smallest sounds, sometimes guessing, sometimes repeating what he hears us say about English: You know laugh is a funny word. It looks like it would sound one way but it really sounds another way. “Without” has two words inside it. He is tickled by what surprises. How the silence of some e’s is not so silent because they change the sound of the vowel before. Hose is one letter away from nose. I begin to imagine that to learn to read English is to begin to know something also about this country. Something hidden, something shown. Something sinister, something joyful. Some things are not what they seem. Other things are what they seem. In the letters I find the shapes my brother’s body makes uprocking inside the circle. I trace the shapes my sister’s body makes as she plants trees. And a million configurations of this letter in front of that one, marching in the streets this spring, this day. My son teaches his sister. W looks like water. This letter looks like that one. Maybe they are a family, maybe not.

With the pigment my son makes a birthday card to mail to his beloved friend. He writes treehouse very neatly in nine brown letters on the bottom of the paper, I don’t know why. Maybe because it is the most wonderful idea he can think of to offer. He asks me, “Have you ever seen a treehouse!?” I am tickled beside his joy that such a thing exists. I take note with my own paper and pencil. A house inside a tree. Oops, it looks like I wrote free.

*

I am late in my thirties when I hear for the first time, from my friend Ross, that one of the strategies of petit marronage for enslaved people was to go into the tops and trunks of trees, finding and keeping a refuge there.

Whenever it is that my partner and I begin to teach our children about the brutality, by design, of this moment and this country, the continuum of catastrophe we are alive and loving and breathing in, I know now that a vital part of what we teach them must have to do with the beauty and power of the imaginative strategies of Black people everywhere. Maroons planting cassava and sweet potato, easily hidden, growing secret in the ground. My best friend’s godsister, Brandy, who, when we were small, knew how to disappear into thin air by opening a book. Tegadelti freedom fighters on the front lines in Eritrea, making pigment out of flower petals, to paint. Palestinians who, when Israeli forces criminalized the carrying of the Palestinian flag in 1967, raised the watermelons up as their flags. Red, black, white, green. The mind that attempts, and attempts again, to find a way out of no way.

It occurs to me that what I right now want for my children is to equip them with fight and armor and space for dreaming in the long, constant work of our trying to get free. I am trying to think like a poet, like a maroon—to tell our children that there were people who, even while under the most unimaginable duress, had the mind to find and keep refuge in the trees. That they are all around us still. Some of them are named Gwendolyn. Some of them are named Kamau.

I am trying to learn with and for the sake of my children. To help them move, even in their woe, toward wonder. To resist the seal of a sentence so complete, and to find, in the syntax, openings through—so onto a ground of their own dreamings, again and again, they alight.

Among the communities doing the vital, brilliant work of tending the dreaming and strength of young people is Little Maroons. For the past fifteen years, they have focused on child-led, African-centered cooperative learning for very young children. If you’d like to support their transition to curriculum development please find them here: http://www.littlemaroonscommunity.com/donate/

Aracelis Girmay is the author of three books of poems, most recently the black maria (BOA Editions, 2016), for which she was a finalist for the Neustadt Prize. She is the editor of How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton (2020).

June 19, 2020

On Horseback

Brianna Noble at a protest in Oakland (Photo: Shira Bezalel)

Bloody news from April laid me low—murders worse than senseless, purposeful slaughter of the sort my country seems to reserve for my people, black Americans. The murders hadn’t occurred in geographical or temporal proximity. They were in the Midwest, Upper South, and Deep South. One had been concealed for weeks, none of the perpetrators had been punished. The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and the needless loss of Sandra Bland, were themselves hard to stomach. Worse was their terrible inevitability, a never-ending history of carnage defined by Emmett Till’s nauseating sacrifice to white supremacy in 1955. An old anguish bound me to these most recent victims.

Then all across the country, Americans rose up for George Floyd, in Black Lives Matters protests against police brutality and Confederate statuary that spread to other countries, where multiracial protestors tore down emblems of colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade. Insurgent masses filled the streets—city streets, suburban streets, little white country town streets, even roads in my outdoor tourist playground of the Adirondacks. The images of protest were glorious, and some took me by surprise by giving me pleasure.

From my hometown of Oakland, California, there came photographs of Brianna Noble on her huge, seventeen-hand horse, Dapper Dan, leading protesters and bearing a Black Lives Matter sign. Noble knew what she was doing, saying, “No one can ignore a black woman on top of a horse.” Her image reappeared nationally, internationally, as above the caption, “Aktivistin Noble bei einer Demonstration gegen Polizeigewalt in Oakland,” in Germany’s Der Spiegel news magazine.

Additional photos of black demonstrators on horseback from Los Angeles and Houston quickly followed, along with quotes from the Compton Cowboys and Cowgirls confirming their decades-long history. There’s even a Federation of Black Cowboys in New York city, founded in 1994, at the border between Brooklyn and Queens.

Most Americans don’t know the history of black cowboys, even though in the heyday of cattle drives from Texas to Midwestern meat processors, black cowboys represented about a quarter of the workers on horseback. After railroads replaced overland cattle drives early in the twentieth century, black cowboys like Nat Love and Bill Pickett turned to the rodeo circuit, where you’re most likely to encounter professional black cowboys and cowgirls today. Cleo Hearn founded the American Black Rodeo Association in 1971, which became the more inclusive Cowboys of Color in 1995. In 1984 Lu Vason founded the annual Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, named in honor of the turn-of-the-twentieth-century inventor of rodeo bulldogging, or steer wrestling. The Oakland Black Cowboy Association is nearly half a century old. Black rodeos are far older than Lil Nas X’s blockbuster hit “Old Town Road,” but the hit record broke color barriers in country music and stirred curiosity about black cowboys.

An attraction to black people on horseback is something I share with millions of others, as an expression of this moment’s protests, and perhaps, I dare add, of hope. There’s more, though, for me, as my antiracist solidarity turned intensely personal. Black Lives Matter photos of black people on horseback brought my autobiography to the surface of my consciousness, as images elicited a memory of my late father.

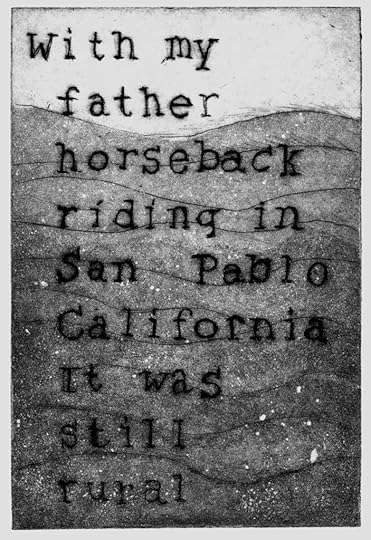

When I was a girl in the fifties, my father would take me horseback riding in San Pablo, which was still totally rural at the time. For him, these outings recalled the joy of boyhood, riding his own blue roan horse in rural Spring, Texas. Both my parents were Texans, united early on by their determination to leave Texas’s mean-spirited segregation. In Oakland they brought me up as a Californian, never sending me back to Texas for summers to reinforce my Texan roots. Of course there were their old friends, also migrants from Texas and Louisiana, their love of certain foods—crab gumbo, head cheese, Texas-style barbecue, and tamales—but little else to make me identify with Texas. Like my mother, I was bookish as a girl. But for my father and me, horseback riding was every Saturday’s treat.

“Memory Piece 300” by Nell Painter (© Nell Painter)

In art school many years ago I made an intaglio, dry point, and aquatint print about my horseback riding. And then, I once again forgot my tie to this Texas of the West and to my father’s equestrian identity. My claim on this Western identity has been something I barely feel, for simply being black imposes a sectional identity that is Southern. Since my youth, a generation of immigrants has added the Caribbean and Africa as places of recognizable black roots. But the West? Not much. Texas is Western, but the blackest part of Texas in historical memory is Juneteenth, the folk holiday (on its way to official recognition) commemorating the 1865 date when Texans learned of their emancipation. When my parents’ Texan origin comes to mind, I usually think Texas = South. Yet horseback riding is Texas = Western. No matter where they were born, the legendary black cowboys of history, of cattle drives and rodeos, came out of Texas.

For me now, to recall my father on horseback, my father as a cowboy, is to reclaim my own personal San Pablo–Californian–Texan past. My reawakening faces down the whitewashed history of Americans—Native Americans as well as African Americans—on horseback. Like so many facets of U.S. history, cowboy history has been lily-whited-out, via the movies’ exaltation of the cowboy as a white man.

In so many ways, too much of U.S. history reads as a story of white men. This is about to change. Although the current upheavals have begun with reforming policing, that’s only a start. History is being remade, including the history of the West. This new history, visualized in images of black women and men on horseback, brings me into more personal, more intimate connection with the political protests that demand wide-ranging, far-reaching improvements in our national life. If the United States can move away from institutional racism and police brutality, millions of my fellow and sister citizens will savor their own complex identities within the comradeship of community.

Nell Painter is the author, most recently, of Old in Art School: A Memoir of Starting Over and The History of White People.

June 18, 2020

Three Possible Worlds

In Black Imagination , a complement to the series of exhibitions of the same name, Natasha Marin curates the voices of Black individuals: Black children, Black youth, the Black LGBTQ+ community, unsheltered and incarcerated and neurodivergent and other Black people. The thirty-six voices in the book are resonant on their own and deeply powerful when woven together by Marin. The following excerpt contains three responses to the prompt “Describe/Imagine a world where you are loved, safe, and valued.”

Photo: Bureau of Land Management. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

close your eyes—

make the white

gaze disappear

*

You don’t talk about moving because I bought the house next to yours. You don’t try to touch my hair, without asking, without saying hello or even speaking when I walk past you. You don’t expect me to do all the work that no one else feels like doing. I’m just out in the world, being myself without fear, shimmering through a star-filled sky. —Laura Lucas, Seattle, Washington

*

I imagine a world where queer babies run wild into the ocean. I imagine a world where queerness is everything and everyone. I imagine a world where pink is blue and blue is pink. I imagine a world where our pain is connected and our liberation is free. I imagine a world where peace is the origin of our hearts. I imagine a world where little boys can wear glitter dresses. I imagine a world where we slay every day. I imagine a world where black babies aren’t killed because of their flamboyance. I imagine a world where little black gay boys can prance in the moonlight. I imagine a world where we each don’t have a gender or color to represent our essence. I imagine a world where black gay boys are leaders and achievers. I imagine a world where seeing is believing. I imagine a world where glitter can stain school hallways and truly uplift those who are queer. I imagine a world where our genitalia do not define our success. I imagine a world where we each have ample opportunity to grow, prosper, and flourish. I imagine a world with pink tutus on black boys. I imagine a world where glitter falls from the sky. I imagine a world where love truly is love. —Tyler Kahlil Maxie, Chicago, Illinois

*

I wonder what it would be like to automatically be given the benefit of doubt; that it would be assumed that I and my opinions have merit; that my contribution is worthy of consideration, even if it is ultimately rejected: to not be dismissed out of hand, and once all other options have been exhausted, to be reconsidered, and found worthy of appropriation. I wonder what the opposite of a pariah is: a paragon, revered instead of reviled. There’s a reality where my skin is not a weapon, rather a virtue; an asset instead of armor. I wonder what it’s like to be the default. I wonder what tenderness is like, what it’s like when the world doesn’t exist to calcify my exterior, to prepare me for the blows to come, but rather cradles and protects so that the slightest scratch is unbearable. I wonder what hardness feels like when all you’ve known is softness. —James E. Bailey, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Natasha Marin is a conceptual artist whose people-centered projects have been featured in Artforum, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and others. In 2018, Marin manifested “The States of Matter,” “The (g)Listening,” and “Ritual Objects”—a triptych of audio-based conceptual art exhibitions in and around Seattle.

From Black Imagination: Black Voices on Black Futures, curated by Natasha Marin, published earlier this year by McSweeney’s.

Dance Time, across the Diaspora

My father, at cocktail parties, liked to get children dancing.

We’d be in the backyard flinging ourselves at and off things: tire swings, tree branches, each other. He’d wander out, beer or scotch in hand.

“What is this?” he’d ask in a loud voice. “The annual Foolishness International board meeting?”

I’d fill with a pleasant warmth.

My father would toss one or two of us over his shoulders. He’d run. We’d chase him to the patio or the living room—wherever the stereo system was.

“Dance time!” he’d say.

He’d teach us moves. Sometimes he’d even do a little choreography. We’d show off, get sweaty. Shy children my father would take by the hand. He’d coax and twirl them until they loosened. I was shy, but not when dancing with him.

“Eiii,” he’d say about any child who was really feeling the vibe.

My father was Ghanaian. Eiii is a sound many Ghanaians make several times a day. Depending on the context and tone, it can mean either that something is very good or very bad. Toward dancing children, my father always meant the sound encouragingly.

Children loved my father. He was playful and funny. For his United Nations job, we moved to a new country every few years: Tanzania, England, Uganda, Italy, Ethiopia. There was little in my life, growing up, that was constant. But at our welcome cocktail party (there was always a welcome cocktail party), I could always count on my father to help me make friends. Those friendships often lasted until we moved again. Most of the children of United Nations employees attend international schools together.

Everywhere we lived, my father’s circle of colleagues and friends was very diverse—multinational and multiracial. They worked for UN agencies, or at various embassies, NGOs, and global enterprises. To parties at their homes—if the hosts were white—my father sometimes brought his own mixtapes.

“You know, I’m African,” he’d joke as he handed them the tape or CD, “I need proper dance music.”

He rarely brought his own music to Black people’s parties. Indeed, the one time I can remember him doing so was because—at that particular friend’s previous party—slow, white country music had been prominently played. That friend was Kenyan.

“What is with you Kenyans and this cowboy music?” my father asked.

“We like the stories,” his friend said.

“I’m an Ashanti,” my father said—referring to his tribe. “We too are storytellers. Even our drums gossip. But what we are listening to now are bedtime stories.”

His friend laughed at my father’s joke, and he laughed again months later, when my father handed him a mixtape.

“Party stories,” my father said.

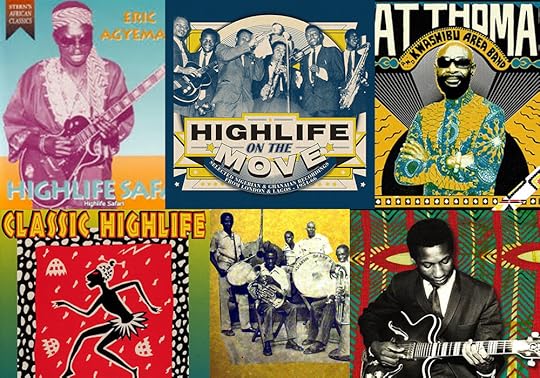

On my father’s mixtapes: Soukous music from what was then Zaire and is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo—Papa Wemba and Koffi Olomide. Soca from Trinidad and Tobago—Mighty Sparrow and Maestro. Mbalax from Senegal—Youssou N’Dour and Fatou Guewel. Black American funk and R&B—Earth, Wind and Fire, Aretha Franklin. And always heavily represented: Ghanaian and Nigerian Highlife and Afrobeat. E. T. Mensah and the Tempos; Bobby Benson; Akosua Agyapong; George Darko; Ebo Taylor; Amakye Dede; and, of course, Fela Kuti.

To start the children’s dance party, my father often replaced whatever was playing with something more to his liking. If an adult protested, he’d say, “Eiii, I’m the DJ.” The eiii, in that case, was a reproach.

I recall a party in Addis Ababa. I was either eight or nine. Against the rules, I’d drunk more than one Coca-Cola. Plus, I’d had cake. Even before we danced, my body buzzed.

The dance floor was on the grass by the pool. My father played “Zombie” by Fela Kuti. I had heard the song before, but that night, I heard it anew.

“Zombie,” like a lot of Ghanaian and Nigerian music, is cyclical. The horns enter with a short fanfare. The lyrics are call and response. With each cycle, the song becomes more urgent. The temperature rises, drops dramatically, then comes back hotter.

Kuti sings: Attention! Quick March! Slow March! My father had us follow Kuti’s orders. He led us in a march with our arms held straight out and taut like zombies. Then, with the horn lines, we went wild—arms swinging, legs kicking. By the end of the song, I was out of breath.

“That was funky,” my father said. He low-fived each of us.

I did not know the meaning of the “Zombie” lyrics. I had not paid close attention. In the car home, as I sat with my head against the back seat window, tired and happy, my father explained that “Zombie” was a protest song—against the brutal and senseless violence enacted upon the Nigerian people by the nation’s army.

“Kuti is saying that the army is full of zombies,” my father said. Then he quoted the lyrics, in Nigerian Pidgin, which is mutually intelligible with Ghanaian Pidgin: “Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think.”

“They only think if they’re told to?” I deduced.

“Yes,” he said. “They just do what the government tells them to do, even kill people.”

“That’s wrong,” I said.

“Yes,” he said, “and Fela got in trouble for writing and performing the song. It became popular. The government didn’t like it at all. They arrested him, beat him. But, through music, he stood up for what he believed in.”

“Funky and brave,” I said.

“That’s right,” he said. I liked that he laughed.

Teaching my sister and me about the history, politics, customs, and culture of Black people, Africa, West Africa, Ghana, and the Ashanti tribe was one of my father’s great preoccupations. On that front, he did not trust our textbooks. Although our schools were called international, the curricula were modeled on either the American or the British system. There was little focus on Africa, even when we were physically located there. And “they will mostly teach you the white, Western versions of everything,” my father said.

My father was also worried that my sister and I would not know Ghana in a deep way; and more than that, he was worried that we would only have a weak sense of home. Our mother is Armenian American. Our parents divorced when I was two and my sister was a year old. My father had primary custody. We were distant from our mother. She lived in America, and we saw her rarely. It would be hard for us to know her culture. My father taught us to say—when asked where we were from—that we were Ghanaian. Yet, from Ghana, in many ways, we were also distant. Some winter and summer breaks, we visited our grandparents in Kumasi. But we stayed only a few weeks at a time. We didn’t speak Twi. When, among my father’s family, I said eiii, everyone laughed. Obruni, some in my father’s hometown called me—foreigner.

Still, to make us feel Ghanaian, my father tried. After school, before dinner, he often gave us lessons. He taught us about the pre-Christian Ashanti gods. Nyame, the sky god. Asase Yaa, the earth goddess. Anansi, the trickster spider who accidentally spread wisdom around the world while trying to steal it all for himself. The abosom—spirits who take the form of trees, rivers, animals, and stones.

Both my grandfather and grandmother came from royal families. My father taught us about the roles my ancestors played in advising the asantehene, the king, and mediating disputes among people in their villages.

In the Ashanti tradition, ancestors are to be venerated. They watch over and protect us, unless they feel ignored. If they do not get their due, we can expect punishment. On our balcony in Rome, my father showed me how to pour libation.

We learned about the Ghanaian fight for independence against the British, and about the vision of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, for Pan-Africanism—unity between all people of African origins, both on the African continent and across the diaspora. I was drawn to this idea. Despite my lack of Twi, no matter where I lived, I was included in Pan-Africanism. I was connected to all Black people, and they to me.

For the same reason that I loved learning about Pan-Africanism, some of my favorite lessons my father taught me were about music.

Ashanti rhythms, he told me, are among the roots of some of the best Black inventions—the blues, jazz, highlife, Afrobeat, funk. Those rhythms survived the Middle Passage.

“You can hear echoes of Ashanti rhythms in Black American music. Then, through trade, tourism, and radio, Black American music forms traveled back to Africa, where they influenced the creation of highlife and Afrobeat. We know, for example, that Fela Kuti was inspired by James Brown.”

This story, to me, seemed miraculous, though I didn’t, then, work to understand why. Now I realize that it was a story of survival, of resilience, of strong roots and wide branches, of mutuality, homecoming, and hope.

My father died when I was thirteen. The many years passed have taught me that I will never stop grieving.

Through my teens and early twenties, for no good reason, I rarely listened to highlife or Afrobeat. Hip-hop and R&B were what I turned to, almost exclusively. Then, when I was twenty-nine, after eighteen years, I returned to Ghana. There were many reasons why it had been that long. My father’s cancer. The instability that followed his death. The cost of the ticket, once I moved, at eighteen, to New York. But at twenty-nine, I got a job with decent pay and paid time off.

I flew into Accra and took a bus to Kumasi to see my grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Almost immediately upon arrival, in a profound way, I felt my father close to me. I saw his face in the faces of people bustling around the airport. I heard him in the voice of a stranger beside me as we waited for our luggage. He had been met by a large group.

“Look at you,” he said to a girl of four or five. “Madam. You are an old lady now.” It was my father’s sense of humor.

Most of all, though, I located him in the music. On the bus to Kumasi, highlife and Afrobeat. In my uncle’s car, highlife. All day, my grandparents played highlife on the radio.

How stupid I’ve been, I thought. I could have been listening all along.

Back in New York, I added to the hip-hop and R&B highlife and Afrobeat. Alone in my room, at the cocktail parties in my mind, I danced with my father.

Years later, I met the man who would become my partner. Professionally, he plays the saxophone. Jazz, funk, Afrobeat. We visit Ghana often. While there, he takes Ashanti drumming lessons, and we both take dance lessons. We go to hear live music in the old and new traditions. We have befriended a group of jazz musicians in Accra—the Ghana Jazz Collective.

These days, musicians like Sarkodie, from Ghana, and Davido, who is Nigerian American, have achieved global success with a mix of, among other genres, hip-hop and Afrobeat. A circle is endless.

“Eiii,” my father might have said, delighted. “Dance time!”

On our last trip, a little less than a year ago, my partner and I went together to meet the highlife legend Koo Nimo, who my grandmother said used to liked her very much when they were young. He told us that, in Ashantiland, drum, dance, and song play central roles in all aspects of life. My father said this to us often. At Ashanti funerals, there is music and dancing. There is joy—a celebration of the departed person’s life. I thought of how, at home, I danced with my memories of my father. I was keeping the tradition—veneration and celebration, strong roots and wide branches.

Nadia Owusu is a Brooklyn-based writer and urban planner. She is the author of So Devilish a Fire (2018) and Aftershocks: A Memoir, forthcoming in 2021. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Literary Review, Catapult, and other publications. Nadia grew up in Rome, Addis Ababa, Kampala, Dar es Salaam, Kumasi, and London. She is an associate director at Living Cities, an economic racial justice organization.

June 17, 2020

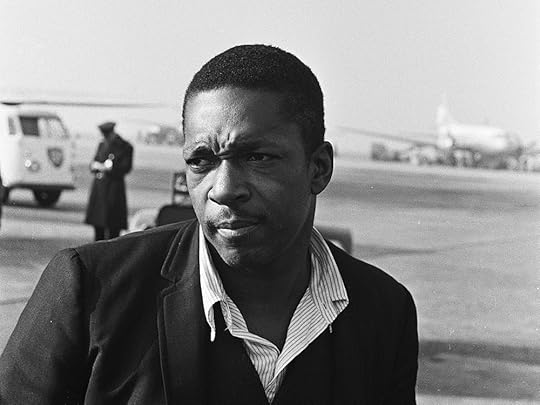

On John Coltrane’s “Alabama”

John Coltrane. Photo: Hugo van Gelderen for Anefo. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The first thing you hear is McCoy Tyner’s fingers sounding a tremulous minor chord, hovering at the lower end of the piano’s register. It’s an ominous chord, horror movie shit; hearing it you can’t help but see still water suddenly disturbed by something moving beneath it, threatening to surface. Then the sound of John Coltrane’s saxophone writhes on top: mournful, melismatic, menacing. Serpentine. It winds its way toward a theme but always stops just short, repeatedly approaching something like coherence only to turn away at the last moment. It’s a maddening pattern. Coltrane’s playing assumes the qualities of the human voice, sounding almost like a wail or moan, mourning violence that is looming, that is past, that is atmospheric, that will happen again and again and again.

What are we hearing?

It has been hard for me to know what to say regarding George Floyd’s murder, or the uprisings that it has sparked. Sometimes I feel as if there is nothing new to say or write, or nothing that I can say or write that I have not already said and written. We watched George Floyd call out for his mother as a police officer suffocated him to death in broad daylight, in full view of citizens, as other officers facilitated the murder by helping to restrain him. On July 16, 2019, Attorney General William Barr declined to bring charges against Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who suffocated Eric Garner in broad daylight, in full view of citizens, as other officers facilitated the murder by helping to restrain him. That murder took place five years, almost to the exact day, before Barr’s decision. I have run out of words for describing the horror of such regularity. I do not even want to describe the horror for you—what will it gain me to describe it again and again and again? What will it teach you to hear me describe it again and again and again?

What would you even be hearing?

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

In “Alabama,” Coltrane asks us to bear witness to this hole in the ground, which is also a hole in America’s story, which is also a hole in the heart of black Americans. He wants us to grieve alongside him at this absence. The quartet recorded the track in November 1963, two months after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, made an absence of four little black girls. When I listen to Coltrane playing over Tyner’s piano I hear smoke rising up from a smoldering crater, mingling with the voices of the dead. He asks us to peer down into the hole, to toss ourselves over into this absence. Just past the one-minute mark, even this funeral dirge collapses in on itself, as Coltrane’s saxophone sinks into a descending arpeggio, coaxing us in.

Then Elvin Jones’s drums enter the fray and Jimmy Garrison begins playing the bass; suddenly we’re on a brisk jaunt that slightly recalls the virtuosity that preceded this track, even though all Coltrane’s sax can muster is squeaking and croaking. We hear Jones mumbling (in delight? Disconcertion?) in the background as if to answer that croak. It all sounds like someone working up a smile in the midst of immense pain, so that he doesn’t disturb the comfort of those around him. And it almost works: we swing and swing until the jaunt comes to an abrupt end, as if the players have remembered why they gathered in the studio that day. We get a second of silence before we find ourselves dropped back down at the beginning of the song, with Tyner’s tremulous keys and Coltrane’s meandering horn. Jones’s and Garrison’s playing disarticulates until they mirror Jones’s mumbling from only a few seconds ago. We’re back at the beginning.