The Paris Review's Blog, page 162

June 9, 2020

Redux: The Tempo Primed

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

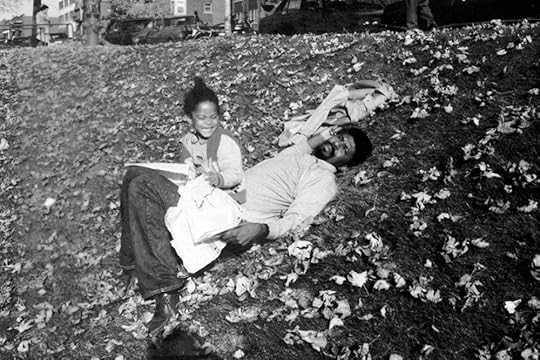

Dany Laferrière with his eldest daughter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re reading Black voices from around the world. Read on for Dany Laferrière’s Art of Fiction interview, Wayétu Moore’s “Gbessa” (the first chapter of her novel She Would Be King), and Wole Soyinka’s poem “Your Logic Frightens Me Mandela.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition—which lowers the paywall on six Writers at Work interviews with Black American authors—here, and then sign up for more.

Dany Laferrière, The Art of Fiction No. 237

Issue no. 222 (Fall 2017)

INTERVIEWER

In 2013, you were elected to the Académie française, the first-ever Haitian or Quebecois writer to join their ranks.

LAFERRIÈRE

Yes, but first they had to sort out whether I was even admissible. You are supposed to be French. It turns out this wasn’t a written rule. At the time the rules were written, they couldn’t even imagine including someone not born in France or a French colony or département, or a naturalized Frenchman. A Haitian in Montreal is none of the above. To be eligible, you also have to live in France—which I did not. So the question became, is it the Académie française as in the French language? Or as in France? The president of the République decided the question—it’s the Académie of the French language. This decision permitted my candidacy to proceed. It was what they call “une belle élection.” I was received with enthusiasm, in the first round of voting. It took Victor Hugo something like four rounds, Voltaire three!

Gbessa

By Wayétu Moore

Issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

Lai was hidden in the middle of forests when the Vai people found it. There was evidence of earlier townsmen there, as ends of stoneware and crushed diamonds were found scattered on hilltops in the unexpected company of domestic cats. But when the Vai people arrived from war-ravaged Arabia through the Mandingo inland, they found no inhabitants and decided to occupy the province with their spirits.

Your Logic Frightens Me Mandela

By Wole Soyinka

Issue no. 107 (Summer 1988)

Your logic frightens me, Mandela,

Your logic frightens me. Those years

Of dreams, of time accelerated in

Visionary hopes, of savouring the task anew,

The call, the tempo primed

To burst in supernovae round a “brave new world”!

Then stillness. Silence. The world closes round

Your sole reality; the rest is… dreams?

Your logic frightens me.

How coldly you disdain legerdemains!

“Open Sesame” and—two decades’ rust on hinges

Peels at touch of a conjurer’s wand?

White magic, ivory-topped black magic wand,

One moment wand, one moment riot club

Electric cattle prod and club or sjambok

Tearing flesh and spilling blood and brain?

This bag of tricks, whose silk streamers

Turn knotted cords to crush dark temples?

A rabbit punch sneaked beneath the rabbit?

Doves metamorphosed in milk-white talons?

Not for you the olive branch that sprouts

Gun muzzles, barbed-wire garlands, tangled thorns

To wreathe the brows of black, unwilling christs …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives.

An Open Letter to All the Future Mayors of Chicago

The following is an excerpt from The Torture Letters: Reckoning with Police Violence , in which Laurence Ralph examines the use of torture—including beatings, electrocution, suffocation, and rape—by officers of the Chicago Police Department.

Piet Mondrian, De rode boom (The Red Tree), ca. 1909, oil on canvas, 27 1/2″ x 39″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I’m a researcher who is writing a book on the history of police torture in your city. The more I learn about this history, the more I feel the need to write to you, even though I cannot be certain who exactly you will be. If history is any guide, you—and all other future mayors of Chicago—are likely a well-connected politician who has a cozy relationship with exactly the instruments of government that I am suggesting are most in need of change. But I must write to you anyway because I believe that change is always possible, however unlikely it may seem in the present.

Indeed, you might already be a career politician, comfortably settled into the state capitol, but you might be, at this very moment, a high school student with lots of big and unrealistic ideas. You may be white or Black, Asian or Latino, or you might not identify with any race at all. You may be gay, straight, or have a fluid gender identity. You may become Chicago’s mayor five years from now, or maybe twenty-five years. Regardless of who you are and how you find yourself as the public persona of this city, it is my sincerest hope that you want to change the culture that has allowed torture to scandalize the Chicago Police Department.

You likely have been briefed about police torture. Perhaps you have gotten assurances from the superintendent of the police department. You might have even met with survivors of police torture. But what I have found in studying this issue for more than a decade is that its complexities are endless. And thus, a strict historical approach, or a policy-oriented approach, doesn’t actually clarify the full extent of the problem. To do that, we need not facts but a metaphor.

The first thing you must know is that the torture tree is firmly planted in your city. Its roots are deep, its trunk sturdy, its branches spread wide, its leaves casting dark shadows.

The torture tree is rooted in an enduring idea of threat that is foundational to life in the United States. Its trunk is the use-of-force continuum. Its branches are the police officers who personify this continuum. And its leaves are everyday incidents of police violence.

*

Let’s begin with the roots, as they are, so tragically, steeped in fear. For all of our achievements as humans, we are still a species that is ruled by very basic instincts, instincts developed millions of years ago and ones shared by most animals. The most basic of instincts is the desire to keep ourselves alive; thus, we are incredibly attuned to danger, and fear shapes much of our emotional life. Because we are fearful of threats, what we crave—perhaps even more than food or companionship—is a sense of safety.

The very idea of safety in the United States is rooted in the frontier logic that justified the settlement of this country in the eighteenth century. For the white settlers, safety was premised on viewing Native Americans as threats and so transforming them into “savages.” It has long been said, most notably by the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, that the idea of the frontier—the extreme limit of settled land beyond which lies wilderness and danger—stimulated invention and rugged individualism and was therefore an important factor in helping to cultivate a distinctive character among the citizens of the United States. This “traditional” narrative has long celebrated our frontier spirit, but the unspoken shadow of that narrative is the fact that invention and individualism are inseparable from the other thing that happened on the frontier—namely, destroying the other. The “civilized” world believed that it had to beat the savages into submission in order to ensure the future of the white race.

This frontier logic is still prevalent today. It is foundational, in fact, to modern-day policing. We can see it at work when one court after another acquits cops who gun down African Americans under the pretext that those cops felt threatened. In such cases, the violence enacted against Black people works to turn the police officers who actually committed the violence into the victims of those Black people. This is how the tangled and twisted logic of fear became rooted in the security apparatus of the United States. But those roots would likely erode were it not for the financial, political, and psychological investment in fear.

Today this investment takes the form of public funding that grounds, supports, and nourishes this country’s enduring logic of threat. Indeed, a key resource that maintains the racial caste system in the United States is the ever-increasing amount of public funding invested in policing and incarcerating people of color. Public funding is the lifeblood of the torture tree. And yet it remains debatable as to whether this funding has made our society any safer, especially for a person of color at the receiving end of police violence. Of the ten most populous cities in the United States, Chicago has the highest number of fatal shootings involving the police from 2010 to 2014. Given that these shootings are often found to be unwarranted, you may be aware that it is common practice for civilians to sue the city and the police department. I’m sure you know that your constituents absorb the cost of those misconduct payouts. But do you realize just how massive the costs have been?

Police misconduct payouts related to incidents of excessive force have increased substantially since 2004. From 2004 to 2016, Chicago has paid out $662 million in police misconduct settlements, according to city records. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that these figures will decrease. Hundreds of Chicago Police Department misconduct lawsuit settlements were filed between 2011 and 2016, and they have cost Chicago taxpayers roughly $280 million. When I was writing this letter in July 2018, the city had paid more than $45 million in misconduct settlements thus far, in that year alone. Keep in mind that misconduct payouts are only a fraction of what the city spends on policing. Chicago allocates $1.46 billion annually to policing, or 40 percent of its budget—that’s the second-highest share of a city budget that goes to policing in the nation. It trails only Oakland, which allocates 41 percent.

I recently came across a report about the funding for police departments in several U.S. cities. The Center for Popular Democracy, Law for Black Lives, and the Black Youth Project 100 authored it. This report is of interest to you. As I read it, one quote in particular stood out:

For every dollar spent on the Chicago Police Department (including city, state, and federal funds), the Department of Public Health, which includes mental health services, receives two cents. The Department of Planning and Development, which includes affordable housing development, receives 12 cents. The Department of Family and Support Services, which funds youth development, after school programs, and homeless services, receives five cents.

As mayor, you have the opportunity to shift these priorities. Needless to say, the way you decide to use public funding reflects your values and the values of your constituents. Your job requires you to defend your constituents’ wants and needs as you negotiate the budget with city council members each year. I know that it will be tempting to spend huge portions of the city’s budget on the police department, especially since that is what the vast majority of cities across the country are doing.

Did you know that our country currently spends $100 billion a year on policing, and $80 billion on incarceration? Well, with this trend, your political advisers might argue that adopting a “tough on crime” stance will be key to your longevity as an elected official. But if you want to address the problem of police violence and make Chicago safer, you must resist the urge to follow the status quo.

The social programs that have been shown to improve people’s well-being in the United States center on health care, education, housing, and the ability to earn a living wage—programs that work to stabilize people’s lives. Time and time again, the research in my field of study has shown that spending money on policing and prison (what scholars call punitive systems) has little proven benefit. To the contrary, Chicago’s spending on policing and incarceration has contributed to a cycle of poverty that has had an impact on generations of people living in low-income communities of color. As you might imagine, the investment in police forces, military-grade weapons, detention centers, jails, and prisons also contributes to an “us versus them” mentality in the police department that justifies police violence.

Although there has been some news coverage on this issue, most of the Chicagoans whom I spoke with for this study were unaware of the financial aspect of policing. When I told them about it, they were upset and disgusted but not particularly surprised.

A Black woman named Monica knew that the city used public funding to finance police violence and to compensate the wrongly convicted. But she thought this approach was shortsighted. “It can’t just be money,” she said. “Money is not enough.”

While speaking about the torture survivors who had spent decades in prison, she elaborated: “Money doesn’t fix the time that has been taken from them, nor does it fix the mental strain that has occurred. It doesn’t fix their access to education or jobs. It’s not enough to just give people money, or to just release them from prison. There needs to be a holistic package.”

Monica thought that elected officials like you should work to funnel funding from policing into public resources and social services. Other people I interviewed agreed with her. They hoped that instead of spending this money merely to compensate torture survivors for what they have endured, the city would instead use a larger share of its public funds for mental health services, housing subsidies, youth programs, and food benefits. These residents regretted the fact that they were implicated in defending police torture. They could only hope that the wider public would start to pay attention to the present reality, the reality that every Chicagoan is financing torture, every day.

Case in point: On July 5, 2018, Chicago youth of color staged a die-in at city hall to protest Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s plan to spend $95 million to build a cop academy. The young protestors set up cardboard tombstones with the names of people who had been killed by the police written on them with black ink. They also wrote the names of schools and facilities that had shuttered because of a lack of public funding. Speaking about her reasons for helping to organize the event, twenty-year-old Nita Teenyson, said: “In my neighborhood there are no grocery stores. We live in a food desert. There are a bunch of schools getting shut down. The mental health facilities are shut down too. And that just leaves people with nothing to do. They become a danger to themselves and their community.” “But if we had those resources,” she continued, referring to the funding earmarked for the police academy, “we wouldn’t even need the police to try to stop those people because resources would already be in place to help them.”

Nita’s description of how the lack of resources in her community contributes to violence was laced with resentment, because a vast expenditure of time and resources was being spent to clean up a problem that should not have existed in the first place. And to make matters worse, the cleanup was taking resources away from larger efforts to make life better in her community.

*

While the roots of the torture tree symbolize the collective fear that materializes in public funding for the police, its trunk represents the police use-of-force continuum. If you don’t have a law enforcement background, you may not know exactly what this continuum is. It’s a set of guidelines, established by the city, for how much force police officers are permitted to use against a criminal suspect in a given situation. The progression of force typically begins merely with the presence of a uniformed officer, who can deter crime simply by parking his squad car on the corner; a step above that is a verbal show of force, such as a cop commanding someone to put his hands above his head; a step above that are the physical tactics an officer might use to establish control of a criminal suspect, like putting him in handcuffs; a step above that are more aggressive techniques that could inadvertently cause injuries or bruising, such as kicking or punching a criminal suspect to subdue him; a step above that is using weapons that have a high probability of injuring someone but are not designed to kill, such as pepper spray; and the last step is the use of weapons that have a high probability of killing someone or at least causing serious injury.

Scholars of policing have often thought that police officers were obligated to be extremely cautious when determining which level of force to use on a civilian. It was this cautiousness, in fact, that was said to distinguish a police officer from a soldier at war. The rationale was that in wartime, one’s cautiousness could be a liability. This is why, when encountering the enemy, soldiers needed to start with the highest level of force and work their way down the continuum. Police officers, however, were supposed to start at the lowest level of the continuum and then work their way up. But most of the Chicagoans I spoke with thought that this distinction no longer exists. Police officers ascend this continuum in the blink of an eye.

In describing this use-of-force continuum, I must make something clear: the protocols that constitute it are human judgments, suffused with assumptions about fear and danger that are too often tied to race. That being said, the way that police officers move up this continuum while deciding how much force to use on a criminal suspect is extremely subjective.

In recent decades, scholars have pointed out that the subjective nature of the use of force among police officers is informed by military thinking. For a long time, soldiers have returned from wars and joined their local police departments. Likewise, police officers have long taken on second jobs—sometimes even second careers—as military personnel. What’s more, when soldiers fight wars overseas, it is common for their perception of the enemy to be shaped by the marginalized groups they grew up hearing stereotypes about. And when they return home, it is common for their ideas about those marginalized groups to be newly informed by the enemy they were just fighting against.

The phenomenon referred to as “the militarization of the police” is often used to describe the way that military equipment—including armored personnel carriers, assault rifles, submachine guns, “flash-bang” grenades, and sniper rifles—once used overseas eventually are allocated to local police stations in small and large cities and towns across the United States. But less often discussed is how alongside this military-grade equipment comes a military mindset wherein the police treat residents as if they were enemy combatants, as if the duties of law enforcement were to occupy and patrol a war zone. This is the mindset of Richard Zuley—a Chicago police officer who became a torturer overseas.

I used to picture the use-of-force continuum as it is described in so many scholarly books: a staircase on which the mere presence of police officers resides at the bottom and death and torture reside at the top. But as I talked to more and more Chicagoans, I realized that the ethos of “justifiable” force that grants police officers permission to mistreat people blends into police torture—the two ends form a circle—until you can’t easily distinguish where mistreatment ends and torture begins.

Laurence Ralph is a professor of anthropology at Princeton University. He is the author of Renegade Dreams: Living with Injury in Gangland Chicago, published by the University of Chicago Press.

This excerpt is reprinted with permission from The Torture Letters: Reckoning with Police Violence , by Laurence Ralph, published by the University of Chicago Press © 2019. All rights reserved.

June 8, 2020

Let It Burn

©Ana Juan

In 2017, I wrote an essay titled “I Don’t Give a Fuck about Justine Damond,” which outlined my perspective on Ms. Damond’s death at the hands of Mohamed Noor, a Minneapolis police officer who also happened to be Somali American and Muslim. My thesis was this: How can I be concerned about a white woman shot and killed by a police officer when there are countless Black people who suffered that fate to the stunning silence and antipathy of the vast majority of white American populace?

The essay was met with the characteristic outrage from white people (but not only white people). They accused me of disrespecting Damond’s memory and being inconsiderate of her family’s feelings. I was also accused of being a hypocrite for not condemning the actions of the cop as I had in previous incidents involving Black victims. Even some of the people closest to me believed that I had crossed a line and thought that I had been too harsh in my assessment and should if not show reverence then certainly remain silent on the matter.

But I could do neither, not with the blood of Black people flowing endlessly in the streets. I insisted that there was a purpose to my position. I had predicted that the outcome of Damond’s death would be unique and that, unlike in the numerous cases in which the murder of a Black person by state agents was considered “justified” and the agents themselves regarded as valiant, the officer who killed Damond wouldn’t have access to the protections or rationalizations that his white compatriots had always been given.

And I was correct.

Without so much as a raised pitchfork, Noor was fired, abandoned by a union that defends even the most egregious actions of its officers. He was swiftly charged, swiftly convicted, and swiftly sentenced to twelve and a half years in prison. And Damond’s family was swiftly compensated, settling for a hefty $20 million from the city of Minneapolis, not at the expense of police forces but at the expense of the taxpayers.

If we are to accept that this is what justice looks like in a penal and punitive nation like the United States of America, the question, for me, is then, why isn’t it applied unilaterally? Why did it take the threat of burning the entire country to ash before the forces of “law and order” would arrest and charge the non-Black (and that’s important to note) police officers caught on camera murdering George Floyd, a Black man? Why are the officers who murdered Breonna Taylor, a Black woman, inside her own home in Louisville, Kentucky, still free to murder another day? Police kill Black people at 2.5 times the rate they kill white people. In 2015, for example, more than a hundred unarmed Black people were killed by police, and only four cops were convicted of any crime in those cases. Experts believe police kill Black people at an even higher rate, but since the nation keeps such spotty records, perhaps intentionally, it’s difficult to grasp and easy for some people to dismiss the magnitude.

The answer to these questions is obvious and yet it’s an answer that this country—from the time it was just a patchwork of greedy and insatiable Europeans who pillaged and plundered the unsuspecting Indigenous people of this land until today—refuses to confront:

The United States of America is, by its very nature, anti-Black.

It isn’t the only anti-Black nation and it isn’t only anti-Black (it also despises the Indigenous, the queer, the trans, the poor, the disabled, and many others). But anti-Blackness is, indeed, the American fact. The nation was constructed on the notion that white people are the only fully human beings on earth, and that humanity exists on a spectrum that moves from the “purity” of whiteness to the “impurity” of Blackness. This isn’t merely some abstract idea; it’s the foundation of every American institution and what animates every American person. It’s what allows, for example, the American media to uphold the pretense that pro-Blackness and anti-Blackness are equal moral propositions or that there can ever be “both sides to the story” when it comes to a state agent murdering a Black person.

Someone should tell the truth. American policing evolves (and I hate to use that word, since I believe policing in this country hasn’t evolved; shape-shift, maybe, but evolve: never) out of the antebellum plantation system of overseers, slave catchers, and lynch mobs; militias of white men (but, again, not only white men) who were charged with (or self-appointed to) the duty of hunting, caging, abusing, and murdering Black people with the blessing of the government. The coalescence of these ragtag arrangements of barbarism under the banner of state will is what we now know as policing. Few of the tactics have changed between then and now. The traffic stops and stop-and-frisk are merely the modern version of slave patrols, where any Black person seen off the plantation was confronted and asked to prove who they were and where they belonged. It’s important to note that in New York City, stop-and-frisk yielded results that were surprising to racists: though Black and Brown people were being stopped at nine times the rate of white people, white people were more likely to be found carrying contraband. Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s response was that even more Black and Brown people needed to be stopped even though his own data indicated the opposite.

That’s because Bloomberg is like most Americans indoctrinated from birth to project all of their fears and sins onto Black people, willing to ignore logic and warp reality to make us their scapegoats. Aside from our cultural productions (America would have no culture without us) and exoticized bodies, they need us because they need someone to blame. And whether they know it or not, most Americans, when they see a Black person menaced by cops, feel a bit of comfort in knowing, whether we call it slave patrol or police patrol, that the more things change, the more they stay the same. These Americans are safe—but more importantly, their property is. And always, their happiness is defined by our misery.

Thus, the refusal of Americans to call evil by its name is an appeal to their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Whiteness, and therefore Americanness, can only function under false pretenses: of its own superiority and of its own innocence. These things become pathological. It’s why white people can be more outraged at, say, the looting of a Target store than the murder of a Black person on camera. It’s how they can devise something like the “George Floyd Challenge” and go viral on social media by filming themselves kneeling on each other’s necks and laughing. They do not understand that in doing so they’ve dehumanized not George Floyd but themselves, for the entire world to see. These people are the dreams of their ancestors just like we are the dreams of ours. Theirs imagined a day when their descendants would be able to own lynching postcards that were no longer static (and that’s how these videos of Black death function: motion lynching pictures). Ours just imagined a day when we would be free.

That is the beauty of these uprisings—which are happening in all fifty states; Washington, D.C.; Puerto Rico; and all around the world, joined, surprisingly, by non-Black people who I can only imagine could no longer suffer under the strain of the guilt that is their blood memory (but not only memory). They hint at the possibility of Black liberation. It will not be achieved, of course. The United States of America would unleash the full fury of its military might upon its own citizens before it would allow that to happen. An America without its proverbial knee on the necks of the Black populace is not America at all. And that is their greatest fear: the collapse of all they hold sacred, which is held together, really, by the fiction that Black people are not people.

We must resist even if defeat is imminent.

I don’t believe we will be liberated from the American regime through superficial and incremental reforms (do you reform a lynch mob by giving them a willow tree instead of a sycamore from which to condemn the hanged?). That is the sacred knowledge that Assata Shakur prophesied for the flock to receive. What is required is a reevaluation, a dismantling. And no nation will go down quietly—especially not one whose character is no different than that of a tick, sucking the blood of the warm body to which it has attached its mandibles until it’s engorged, leaving disease in its wake. When I was a child, I was told that one way to remove a tick was to light a match and hold it near.

The thought of fire frightens me. It can be painful, deadly even, if not deployed with the utmost care and precision. But it can also be cleansing. Nature itself renews the forests in this way, making room for fuller, lusher, greener, more abundant spaces where decay had once resided. And if this is true, if James Baldwin was correct and the rainbow was, indeed, a promise, then what have we to lose that hasn’t already been lost?

I suppose we’ve had the solution the entire time. But given our proximity to our oppressors and our already weary bodies, it was simply too risky to take the chance. I’m still scared, for me and for you. Because we are at the crossroads now (don’t you hear banjo playing?), pushed here by the unrelenting robber barons who have stolen everything from us including our own souls. And all we have—all we have—is the torch in our hand to light our way forward.

Raise your torch high, for that is the stance of liberty; and, as I believe singer Usher Raymond put it most plainly:

Let it burn.

Robert Jones Jr. is a writer from New York City. He has written for numerous publications, including the New York Times, Essence, OkayAfrica, The Feminist Wire, and The Grio. He is the creator of the social justice social media community Son of Baldwin. Jones was recently featured in T Magazine’s cover story “Black Male Writers of Our Time.” His debut novel, The Prophets, will be released in January 2021.

Performing Whiteness

Original illustration © Otto Steininger

When the weather warms up I feel two things: excitement and trepidation. My body longs for the warmth of sun on my skin and my heart remembers that summer is the season of death. It has been this way for a long time, but I think I started counting when I was a teenager. That’s when I learned of the “Red Summer”; in 1919, white supremacist terrorist attacks and riots resulted in mass murder of Black civilians in more than three dozen cities across the United States. Often in the summer I am in the presence of young people who, as teenagers, are just coming into their awareness of the brutality that is cyclically enacted against Black people. Often I need to hold space for their rage, their grief, their fear. I am tired of summers beginning this way.

A short while ago, as I was nursing my son, I scrolled through the New York Times. Reporting about Ahmaud Arbery caught my eye. I clicked on a video link. Though I didn’t intend to, I saw the cell phone footage of his murder. I saw him running as pickup trucks bore down on him, I saw armed white men jump from their vehicles. I saw the buckshot disperse into and out of Ahmaud’s body. I saw him turn to run and fall.

I thought of how we often see Black bodies running, bodies like his in particular—peak fitness and youth and promise. Sprinting, turning on a dime, twisting and perhaps catching a long pass to run a touchdown. Instead, Ahmaud turned, picked up his knee to run, and fell forward, succumbing to the wounds of shotgun blasts to his chest.

I felt my spirit crumple as his body did. It stole my breath and ignited a raging panic in my flesh. My heart pounded with a drumming that goes back generations. My body remembered nursing my firstborn son while protesters marched past my house to demand justice for Philando Castile. My body remembers.

But then something else caught my eye. It was the white man who shot him. It was how he looked down at the human being he’d just mortally wounded. It was the conviction on his face. The posture eerily reminiscent of so many white men who have walked away from the violence they’ve enacted against, in particular, Black men. Black men who, in a fair fight, would’ve wiped the floor with them. But this fight, since the beginning, has never been fair. The deck has always been stacked against us. This fight goes looking for our young, proud, strong men. It hunts them. It runs them down in pickup trucks. It demands their attention, even when it has no authority to do so. It is staggered by the grace and beauty and freedom it sees in what it chases. It wants it and extinguishes it instead.

As a stage director I am trained to watch how people move and to interpret meaning—to read their bodies. As an American I am also trained to read bodies and see race. And, like looking through a pair of binoculars, these two lenses perfectly aligned in the moment after Ahmaud fell, magnifying the embodiment of white supremacy in his murderer. The way that man bore up. The way he turned and walked back to his truck, to his father, a shotgun slung low in his hand. It was in his shoulders, his jaw, his waist, his hips. I saw it come over him and I saw him stand up in it and move with it and, though he didn’t say the words, they were all over him: Take that, nigger. I realized I was watching thousands of white men throughout American history standing over a broken Black body, their breath ragged, adrenaline cresting, spent, feeling legitimated by the proof of their violence. It is more than a rash decision; their bodies betray an assumptive birthright. Their bodies firm up and swagger into a ritualistic circle of savagery. It is a possession.

I am not absenting this man from his choice or his personal culpability in the murder of Ahmaud Arbery. I am trying to acknowledge that part of what motivated the chase, the sense that he could command Ahmaud to stop, the murder itself, was racial inheritance.

He walked away feeling more manly, more righteous, and more like a cowboy than he’d ever feel in his life again. That’s what keeps them after us. They need to feel their groins contract. They need to feel big in this world and they can’t seem to do it without killing us. The feeling doesn’t last and so they come for more of us. It is a voracious, depraved need. It is old and it is still here.

In my work I focus a lot on the body, on embodied racialized trauma and embodied racist sentiment. This work reveals how our bodies are raised into a history so rife with violence that more than half of us won’t look at it, don’t really know it. This is history buried in our flesh, in our ancestry, in our shared nationhood. It works differently on Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color than it does on white folks, but we are all disciplined by it, made smaller by it. Over many years I have worked to exorcise it from myself and from others. I use a blend of theater and healing techniques to examine, excise, and suture.

Epigenetic research focuses on how the body responds to generational trauma. We evolve to survive. But how does a body respond to generational expressions of racial power?

What happens to white bodies in these encounters with us? It is in them, too, this racial past. Perhaps even more than it is in us. Perhaps that is exactly the problem. Perhaps because they refuse do the work to purge that embedded racial inheritance, it keeps lurching blindly outward, like a parasite that’s eaten what it can of its host and needs another and another. Insatiable. Adaptable. Extant.

Shortly after viewing the murder footage, I read a story about a woman who tried twice to kill her child and, upon succeeding, suggested that she’d been carjacked by two Black men who stopped her for drugs and, inexplicably, took her child and her cell phone. Soon we would learn that it was in fact she who pushed her own child to his death in a Miami canal. That feeling that the life of her son, a child with a disability, was expendable is the same brutalizing force that would allow her to scapegoat two imaginary Black men with zero concern for the hunt that her claim would initiate and the innocent lives it might end.

This disease is evidenced in all kinds of unspeakable violences and there are telltale signs before it erupts to claim lives. We’ve just become so accustomed to allowing, ignoring, and avoiding them that we permit the host to become too proximate to another victim.

Days later I watched yet another performance of racial inheritance, this time from Amy Cooper, who called the police to report a fabricated threat from Christian Cooper, a Black bird-watcher, after he asked her to obey the law and leash her dog. I watched her performance escalate. Her initial threat—“I’m going to tell them there is an African American man threatening my life.” How, as the dispatcher asked her to clarify her words, she doubled over, her voice changed pitch, her breath became short. I saw her body lean into a legacy of white fragility and white femininity and in this she expressed a malignant power. I saw her brutalize her dog as she brutalized this man with her words and I realized that in that moment of possession by her racial birthright she didn’t care what she hurt. She needed to feel this power, this control. Or perhaps she needed to feel out of control and assured that the system would service her, the whole thing built around protecting her word, her honor, her fragility.

And finally, in my hometown, a white police officer drives his knee into the neck of an unarmed, handcuffed Black man, forcing his body into the asphalt as he begged for breath. We all know George Floyd’s name today, not because of how he lived his life but because of how he died, at the mercy of another white man determined to demonstrate his authority and control, emboldened by the racial violence perpetuated by a white supremacist administration, enabled by a feckless Republican party, and tolerated by hamstrung Democrats.

If I’m gracious, which I am trying to be, I will acknowledge that the bodies and psyches of these white people have been subjected to white supremacy as well—that they’ve been disciplined to show up this way, to believe that this is the ultimate expression of their power. That perhaps, crushed under the normalizing and brutalizing forces of white supremacy and gender normativity in this country, they feel this is their only available expression of strength. I will acknowledge that these people were once children who did not know hate, who learned dehumanizing lessons from their parents, their elders, their community, and their media about who they should be in the world and how they should treat others in relation to their whiteness. I see their wounds and I want to excise the poison eating away at them. This is not magnanimous. I want to do this because it may save Black lives.

White folks, you must dig into your embodied racism, even—especially—if you think it’s not there. And this is not just to shift what you say and how you shape your arguments, questions, Facebook posts, tweets. It’s not about performing your wokeness. This isn’t about what you say—it’s about how you act; how your body might be predisposed to rely on a racial inheritance that endangers the lives of others. What’s in your guts, in your muscles, in your blood? What are you carrying dormant in your body that springs up when confronted with Black joy, Black power, Black brilliance, Black Blackness in the world? How can you train your bodies to respond differently when you are triggered, when you’re in fight-or-flight mode? How can I help you stop yourselves from killing us?

White people may not realize it, but white supremacy causes disruptions between their psyches and their bodies. These disconnections are both literal and metaphorical. Literally, when white people are racially triggered, they have reported feeling numbness, experienced ringing ears and tunnel vision, a faster heartbeat. Metaphorically, it disconnects white people from the pride of cultural ancestry, which they sacrificed for the fiction of race. When white people risk leaving the cult of whiteness, they find meaningful connections to their own cultural wellsprings that are affirming, nourishing, and empowering.

James Baldwin mused that “one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.” I will acknowledge that white folks may be in pain. They need to find healthy ways to express their rage, sadness, disappointment, and fear, ways that would bring them love rather than admonishment. Too many white people are fine with what they see as “benign” racism until it is outed by video footage and then they scramble to distance themselves from it. Those who are “caught” find that after having expressed the ultimate performance of their racial inheritance, instead of receiving accolades and awards, they are abandoned.

In 2020 with so many video cameras, I worry about the psychic recognition of witnessing embodied racial inheritance. I worry about how seeing racial violence emboldens hate. I wonder how we can fill our consciousnesses with more love.

Here is what I know: hatred is heavier than love; ambivalence is less rewarding than action. We are diminished by the man occupying the presidency. We are diminished by those who enable him. People who have spent most of their adult lives on the sidelines are moving to the center. White folks need to move past their fear and call each other into deep, authentic, and embodied learning and unlearning around what it means to be be white in this country. All of what that means, both the history and the present.

White police officers in Brooklyn recently took a knee with protesters and since then the gesture has spread among white people who once characterized kneeling as an affront to America itself. This simple and powerful gesture cost Colin Kaepernick, one of the NFL’s most talented quarterbacks, his career. When Donald Trump yelled for the league to “get that son of a bitch off the field,” or when Laura Ingraham suggested that LeBron James should “shut up and dribble,” they essentially called for owners to get their “bucks” in line, reminding Black athletes of the social and contractual limits of their agency. They want bodies, not brains; performance, not people.

As a director I do not practice “color-blind” casting. Bodies arrive written with racial scripts that inform the meaning of gesture, stillness, and movement onstage. It means something different for a Black man to take a knee than it does for a white police officer. The difference is in the risk. We have yet to see whether officers kneeling represents a pledge of accountability or merely an attempt to quiet the furor over police brutality. Rather than break, power will bend. Three white men in uniform kneeling with Black protesters shouldn’t be remarkable, but in America it is. In light of the “blue lives matter” campaign, acquiescing seems profound. A simple gesture; a powerful message. It isn’t nearly enough, but it’s a beginning.

Stating that Black lives matter is a very minimum acknowledgement of humanity. The tenacity of the fight against this statement should absolutely stagger Americans and signal how far we have yet to go. Statements of solidarity must be actualized. We need more gentleness, compassion, and courage embodied by white people. We need people, not performance. We need for expressions of Black freedom, joy, grief, and rage not to cost us our lives. We need to get free.

The body is a powerful thing.

If it can breathe.

Sarah Bellamy is a stage director, scholar, practitioner of racial healing, and the artistic director of Penumbra Theatre Company. She lives in Minnesota with her husband and two small children.

The Art of Distance No. 12

The Paris Review began sending out The Art of Distance twelve weeks ago, with the intention of offering hope, solidarity, and good company to readers facing a global pandemic. The pandemic continues, but the killing of George Floyd by police brought to the fore two other deep-rooted crises in our communities: police brutality and systemic racism in America. The Paris Review opposes racism and injustice. We are determined to work with contributors and readers and as an organization to make our industry a more equitable, dynamic, and creative place. This is a long process, but the Review believes it is vital and imperative work.

This week, we’re sharing six more Writers at Work interviews with Black American writers and listing resources for those who wish to contribute to the movement. May these conversations and organizations offer a measure of inspiration and consolation, and may spending time with these texts remind us that this necessary work is ongoing.

Stay safe, whether you are at home or in the streets.

—The Paris Review

This week, we’re highlighting more of the Black American voices in our archive by lifting the paywall on the following interviews (the interviews opened last week remain available as well):

Maya Angelou, The Art of Fiction No. 119

“I thought early on if I could write a book for black girls it would be good because there were so few books for a black girl to read that said this is how it is to grow up. Then, I thought, I’d better, you know, enlarge that group, the market group that I’m trying to reach. I decided to write for black boys and then white girls and then white boys.”

Samuel R. Delany, The Art of Fiction No. 210

“The city gets you used to crowds, used to people relating to one another in a certain way, like strong and weak interactions between elementary particles. The strong interactions only come into play when the particles are extremely close, less than the distance of a single atomic nucleus. Those are the interactions readers want to see in novels. At the same time, paradoxically, cities can be dreadfully isolating places. The Italian poet Leopardi wrote in a letter to his sister, Paulina, about Rome, that its spaces didn’t enclose people, they fell between people and kept them apart.”

Ralph Ellison, The Art of Fiction No. 8

“Now, mind, I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest. Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of nineteenth-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself.”

Charles Johnson, The Art of Fiction No. 239

“We’ve lost something. And so my question is, What does it mean to be civil? What kind of person do you have to be? That’s an idea we can trace back through two thousand years of Western history, and the East as well, going back four or five thousand years. It’s not a question that is going to go away.”

Edward P. Jones, The Art of Fiction No. 222

“Ten or so years ago, someone asked me to come to her class and answer questions about Lost in the City. This one white woman said she had trouble feeling or caring about any people who weren’t like her. You hear that and it’s like somebody slapped you in the face.”

Ishmael Reed, The Art of Poetry No. 100

“With literature you can condemn the powerful, and you can critique the powerful. Of course, Dante paid for it. He was never able to return to Florence. He died in exile. He endured a lot to speak his mind. They tell us, Don’t write about politics. You know, because the politics is aimed at them. But Dante had a political office! And some of those characters in Dante’s Inferno are political opponents of his. The same with Shakespeare. His work was political. I was reading The Merchant of Venice the other day and it includes one of the most devastating antislavery arguments ever written. So I don’t know where they get the bourgeois idea that art shouldn’t be political.”

*

We also urge you to engage with the following resources shared by organizations that are dedicated to working against police brutality or to uplifting Black voices and communities.

The Schomburg Center’s Black Liberation Reading List

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is curating this list of new and classic books in all genres for adults and kids.

Order from These Black-Owned Bookstores

Lit Hub has compiled a user-friendly list of Black-owned bookstores across the country.

Entropy Magazine: Where to Submit: Bail Fund Edition

Entropy has devoted a big slot in this monthly column to a list of bail funds and community organizations working to assist protesters and others.

The Brown Bookshelf: KidLit Rally 4 Black Lives

Kwame Alexander, Jacqueline Woodson, and Jason Reynolds presented this panel on June 4, the first half for kids, the second for parents, to offer resources, solidarity, inspiration, and active ways of fighting racism through literature for kids.

June 5, 2020

Staff Picks: Professors, Paychecks, and Poetry

Still of Kathleen Collins’s Losing Ground. Courtesy of Milestone Films.

Sara, the protagonist of Kathleen Collins’s film Losing Ground, cannot admit that she is a professor first and a wife second, and therein lies her problem. As her desire to break free from her steady, rational nature finds expression in academic fervor, it is held tighter by the bonds of domestic life—a heartbreaking portrayal of what is so often irreconcilable in womanhood. Losing Ground is streaming for free right now on the Criterion Channel, along with films by Julie Dash, Maya Angelou, Cheryl Dunye, and many others. —Lauren Kane

With his roles in George Balanchine’s Agon (1957) and The Four Temperaments (1946), Arthur Mitchell shaped the aesthetic of twentieth-century ballet. He solidified his place as an iconic figure in dance history and post–Harlem Renaissance art when he founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969, the year after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As he told the New York Times in an interview shortly before his death in 2018, “I actually bucked society, and an art form that was three, four hundred years old, and brought black people into it.” DTH, which continues to lead the movement for racial equity in classical and contemporary ballet, is halfway through a two-year celebration of its fiftieth anniversary. With tours cut short by the coronavirus, the company has moved its season online, opening with the seminal Creole Giselle. The work first premiered at the London Coliseum in 1984, choreographed by Mitchell and staged by Frederic Franklin after the 1841 original by Jules Perrot and Jean Coralli. Don’t forget to tune in later today for pre-premiere festivities: DTH member Stephanie Rae Williams will be teaching a variation from the first act on Instagram Live at three. Then, at eight, artistic director Virginia Johnson will lead a conversation titled “Becoming Giselle,” speaking with former DTH ballerina Kellye Saunders and current company dancers about preparing for the title role. Creole Giselle airs on the company’s YouTube and Facebook channels on Saturday night at eight. —Elinor Hitt

Nicole Dennis-Benn. Photo: Jason Berger.

The current issue of Kweli Journal centers on black girlhood, showcasing stories that focus on that particular chapter between “child” and “young woman,” when the characters and settings of life begin to expand and shift into new and difficult patterns. An island sixth-grader seems to know perfectly every road, lagoon, and tree of her world, until she discovers that her mother, a hotel maid, holds deeds to resort land thanks to a secret marriage with her white boss—snaky postcolonial tendrils mixing with her efforts to rise above it. A South Carolina fourteen-year-old slogs through a familiar summer mix of babysitting, helping out with the family business, and working a prized but stultifying internship, her initial excitement at the prospect of making “real money” shattered when she sees just how quickly a paycheck disappears with relatives and neighbors in the picture. A “nerdy round girl” in New York befriends another nerd whose comparatively wealthy immigrant parents keep strict watch over her social life. A girl from Detroit reads Anne of Green Gables, is sent to live with a Marilla-like grandfather in Lansing, and, just as Anne learns the workings of Prince Edward Island society, begins to learn family secrets that preceded her exile. A young Brooklynite ventures into a welfare hotel looking for her mother’s stolen purse, and recognizes her relative privilege. The oldest protagonist, a stoic high schooler used to the idea that things are sometimes good and sometimes bad, is finally left alone with the bad—a cold bath with parents arguing over the hot water and other bills in the background—when her brother moves out. This journal deserves to be read in its glorious entirety; as the guest editor of this issue, Nicole Dennis-Benn, puts it, “In these stories we see our vulnerabilities and complexities as black girls navigating a world that has already made up its mind about us.” —Jane Breakell

I would like this pick to read simply: Ja’Tovia Gary’s work speaks for itself. However, given that my favorite of her films so far isn’t readily available online, I suppose I should tell you that when I saw that favorite, The Giverny Document (Single Channel), at the True/False Film Festival this March in Columbia, Missouri, after a full day of shuffling from movie to meal to movie to movie like some horrible semi-sentient hummus-fueled slug, sitting finally in an overheated and underfilled theater in a side room of a hotel downtown, I suddenly felt like a firecracker was going off inside me. I speak poorly—it’s difficult to put into words the constellation of ideas and emotions Gary commits to those forty-one minutes of film—but trust me: Ja’Tovia Gary’s work speaks for itself. —Brian Ransom

Alondra Uribe is one of my favorite living poets. She’s eighteen, but she writes “Ode to High School” like she’s been to thirty-one and back and can see what it was and how it is over. Alondra would have celebrated her graduation this month. Instead, she wrote and performed that poem as part of a short video project for DreamYard, an organization with which she has been studying poetry since the age of twelve (full disclosure: my partner is an employee of DreamYard, and I owe him the honor of knowing Alondra and her work). “Ode to High School” starts: “What I would have written in my yearbook … ” and comprehends the loss of graduation rituals with an understanding that twirls disappointment like it’s a Styrofoam ball on a science-fair universe. “The devils of the Department of Education ask me what builds community / so they know what to steal,” she wrote when she was sixteen. The Department of Education closed her middle school, JHS145, in 2017, but that goes unmentioned beside other punishments of childhood; you believe her when she delivers the line, “when I say I hate school / I mean it.” I have been reading, watching, and listening to Alondra’s poems for years, but I have to remind myself that she was fifteen when she wrote and performed lines such as “how hard do I have to brush / and buff / my teeth / for the white light / to reach you? / He calls me Heaven.” How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Ask Alondra Uribe; she’s read there. Maybe by knowing her power, her talent, the incandescence of her defiance and her self-definition—and, sure, by practicing. At Carnegie Hall, she had the last word: “brown girls from The Bronx aren’t supposed to write poetry but I did it anyways.” —Julia Berick

Alondra Uribe. Photo: Shannon Finney.

June 4, 2020

Policing Won’t Solve Our Problems

Photo: © Sarah / Adobe Stock.

Policing needs to be reformed. We do indeed need new training regimes, enhanced accountability, and a greater public role in the direction and oversight of policing. We need to get rid of the warrior mindset and militarized tactics. It is essential that police learn more about the problems of people with psychiatric disabilities. Racist and brutal police officers who break the law, violate the public trust, and abuse the public must be held to account. The culture of the police must be changed so that it is no longer obsessed with the use of threats and violence to control the poor and socially marginal.

That said, there is a larger truth that must be confronted. As long as the basic mission of police remains unchanged, none of these reforms will be achievable. There is no technocratic fix. Even if we could somehow implement these changes, they would be ignored, resisted, and overturned—because the institutional imperatives of the politically motivated wars on drugs, disorder, crime, et cetera, would win out. Powerful political forces benefit from abusive, aggressive, and invasive policing, and they are not going to be won over or driven from power by technical arguments or heartfelt appeals to do the right thing. They may adopt a language of reform and fund a few pilot programs, but mostly they will continue to reproduce their political power by fanning fear of the poor, nonwhite, disabled, and dispossessed and empowering police to be the “thin blue line” between the haves and the have-nots.

This does not mean that no one should articulate or fight for reforms. However, those reforms must be part of a larger vision that questions the basic role of police in society and asks whether coercive government action will bring more justice or less. Too many of the reforms under discussion today fail to do that; many further empower the police and expand their role. Community policing, body cameras, and increased money for training reinforce a false sense of police legitimacy and expand the reach of the police into communities and private lives. More money, more technology, and more power and influence will not reduce the burden or increase the justness of policing. Ending the War on Drugs, abolishing school police, ending broken-windows policing, developing robust mental health care, and creating low-income housing systems will do much more to reduce abusive policing.

In the twentieth century, two major areas of policing were eliminated when alcohol and gambling were legalized. These two changes reduced the scope of policing without sacrificing public safety. Prohibition had led to a massive increase in organized crime, violence, and police corruption but had little effect on the availability of alcohol; ending it reduced crime, enhanced police professionalism, and incarcerated fewer people.

Similarly, fruitless attempts to stamp out underground lotteries, sports betting, and gambling proved totally counterproductive, empowering organized crime and driving police corruption. Government control and regulation of gambling has raised revenue and undermined the power of organized crime. By creating state lotteries, regulating casinos, and only minimally enforcing sports betting, the state has limited police power without sacrificing public safety. There is no reason the same couldn’t be done for sex work and drugs today. The billions saved in policing and prisons could be much better used putting people to work and improving public health.

We don’t have to put up with aggressive and invasive policing to keep us safe. There are alternatives. We can use the power of communities and government to make our cities safer without relying on police, courts, and prisons. We need to invest in individuals and communities and transform some of the basic economic and political arrangements in our society. Chemical dependency, trauma, and mental health issues play a huge role in undermining the safety and stability of neighborhoods. People who are suffering need help, not coercive treatment regimes or self-help pabulum; they need access to real services from trained professionals using evidence-based treatments. Even children and teens with some of the most serious personal problems can be helped with sustained and intensive engagement and treatment. They need mentors, counseling, and support services for themselves and their families. These “wraparound” approaches show promising results and cost a lot less than cycling young people through jails, courts, emergency rooms, probation, and parole.

People adapt their behaviors to a dysfunctional environment where unemployment, violence, and entrenched poverty are the norm. Even after twenty years of declining crime rates, there are neighborhoods where violence remains a major problem. These areas are almost all extremely poor, racially segregated, and geographically and socially isolated. The response of many cities has been further intensive policing. Recent crime increases and social unrest in places like Chicago, Milwaukee, and Charlotte attest to the failure to end abusive policing or produce safety. The most segregated and racially unequal cities in the country are its most violent.

Decades of deindustrialization, racial discrimination in housing and employment, and growing income inequality have created pockets of intense poverty where jobs are scarce, public services inadequate, and crime and violence widespread. Even with intensive overpolicing, people feel unsafe and young people continue to use violence for predation and protection. Any program for reducing crime and enhancing social well-being, much less achieving racial justice, must address these conditions. No one on the political stage is talking seriously about this reality. Racial segregation in the United States is as bad today as it has ever been. Poor communities need better housing, jobs, and access to social, health, recreational, and educational services, not more money for police and jails, yet that’s what’s on offer across the country. From Chicago to New York to California, local politicians continue to hold out more police and new jails as the solution to community problems. This must stop.

These communities also need more political power and resources to develop their own strategies for reducing crime. Concepts like restorative justice and justice reinvestment offer alternatives. The money that would be saved by keeping people out of prison could be spent on drug and mental health services, youth programs, and jobs in the community. At the same time, offenders could be asked to make restitution to their victims and the community through community service projects, agreements to stay clean and sober, and participation in appropriate programing. The justice reinvestment movement also looked to use savings achieved by reducing incarceration rates to invest in high-crime communities. Unfortunately, many of these programs ended up only moving money around within the criminal justice system and excluding communities from any role in the process. The basic ideal remains sound, but new efforts at realizing it are needed and communities need to play a major role in deciding how the resources are used. But not all problems can be solved at this level. Access to decent housing and employment and the ongoing problems of polarized income structures and racial discrimination in housing must be dealt with systemically. Raising the minimum wage, restoring transit links, and cracking down on housing discrimination are big problems that operate largely outside these poor neighborhoods. If we want to make real headway in reducing the concentrated pockets of crime in this country, we need to create real avenues out of poverty and social isolation.

The Black Youth Project in Chicago envisions a program for economic development that would substantially improve the lives of people in high-crime communities as an alternative to relying on police and prisons. Their “Agenda to Build Black Futures” calls for reparations to address the long legacy of systematic exploitation of African Americans, from slavery through Jim Crow and into the current era. Just as importantly, it focuses at length on decent jobs that can sustain a family above the poverty line. That means raising the minimum wage through direct government action, as well as giving workers the right to self-organize for better wages. Most of the advances that working Americans have made in the last century have come through the process of unionization and workplace activism, but in the last thirty-five years governments have moved systematically to reduce worker and union power. Private-sector protections have been largely erased, leading to massive union-busting drives and decimating union membership rates. The public sector retains more protections, but austerity economics have substantially eroded earnings and many Republican politicians and conservative courts are actively moving to break unions and further drive down wages. Unfortunately, many unions have resisted racial integration historically, and some remain incredibly white even today, so government protection of unions in the absence of a racial justice program will not be sufficient.

The Movement for Black Lives has also outlined a plan for economic and political justice that includes greater investment in schools and communities based on priorities developed by black communities. At the heart of their program is a set of economic justice proposals, including reparations, which would reduce inequality, enhance individual, family, and community well-being and protect the environment. They call for major jobs programs, restrictions on free trade and Wall Street exploitation, and vigorous protections of worker rights. They specifically demand that funding for criminal justice institutions should be shifted to education, health, and social services. To make this possible, they demand political reforms and are developing plans for grassroots mobilizations. This is what police reform has to look like if it’s going to bring meaningful changes.

Rural areas need help as well. The growth in opioid use is closely linked to the downward mobility of the rural poor and the expansion of the destructive war on drugs. While simplistic protectionism and jingoistic anti-immigrant mania are unlikely to bring long-term stability, our rural areas must become more economically sustainable and livable, with green jobs, infrastructure development, and nontoxic food production. Reducing subsidies to multinational corporations that move jobs overseas to countries with little in the way of labor rights or environmental protections would also be a good place to start, replacing “free trade” with “fair trade.”

None of these initiatives by themselves will eliminate all crime and disorder. They need to be combined and new ideas would need to be developed and tested, but those who would benefit from this process lack the political will and power to do so. U.S. culture is organized around exploitation, greed, white privilege, and resentment. These are derived in large part from our economic system, but even profound economic changes do not automatically produce positive cultural changes, at least not overnight. Cultural norms also impede efforts to change these systems. What’s needed is a process in which the very struggle for change produces cultural shifts. By working together for social, economic, and racial justice, we must also create new value systems that call into question the greed and indifference that allow the current system to flourish. We must take care of each other in a climate of mutual respect if we hope to build a better world. One of the more positive aspects of the Black Lives Matter movement has been its embrace of differences of identity and the diversity of people engaged in leading it. We can’t fight racism while embracing homophobia, any more than we can fight mass incarceration by embracing a politics of punishment.

Both of our major political parties have accepted the politics of austerity that globalized capital has imposed on us. The neoliberal movement has been incredibly successful in normalizing the view that the only way to move forward is to unleash the creative power of a small number of economic elites by stripping away all regulations, worker protections, and financial obligations so that they can maximize their wealth at the expense of the rest of us. For thirty years we’ve been told that the result will be a rising tide for everyone; a trickling down of the spoils—but we’re still waiting. Wages and living standards for all but the wealthiest continue to decline. The middle class is being eviscerated, poverty and mass homelessness are increasing, and our infrastructure is collapsing. When we organize our society around fake meritocracy, we erase the history of exploitation and the ways the game is rigged to prevent economic and social mobility.

When people complain about these realities, they are told it’s their own fault, that they didn’t try hard enough to be part of the glorious “1 percent,” that they don’t have what it takes and thus deserve to be degraded. This justifies defining all problems in terms of individual inadequacy, calling those left behind the architects of their own misery. Rather than using government resources to reduce inequality, this economic system both subsidizes inequality and criminalizes those it leaves behind—especially when they demand something better. The massive increases in policing and incarceration over the past forty years rest on an ideological argument that crime and disorder are the results of personal moral failing and can only be reduced by harsh punitive sanctions. This neoconservative approach protects and reinforces the political, social, and economic disenfranchisement of millions who are tightly controlled by aggressive and invasive policing or warehoused in jails and prisons.

We must break these intertwined systems of oppression. Every time we look to the police and prisons to solve our problems, we reinforce these processes. We cannot demand that the police get rid of those “annoying” homeless people in the park or the “threatening” young people on the corner and simultaneously call for affordable housing and youth jobs, because the state is only offering the former and will deny us the latter every time. Yes, communities deserve protection from crime and even disorder, but we must always demand those without reliance on the coercion, violence, and humiliation that undergird our criminal justice system. The state may try to solve those problems through police power, but we should not encourage or reward such short-sighted, counterproductive, and unjust approaches. We should demand safety and security—but not at the hands of the police. In the end, they rarely provide either.

Alex S. Vitale is a professor of sociology and the coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College. His writings about policing have appeared in the New York Times, New York Daily News, USA Today, The Nation, and Vice News. He has made appearances on NPR and NY1.

Excerpted from The End of Policing , by Alex S. Vitale, published by Verso Books, available now as a free ebook.

June 3, 2020

A Little Patch of Something

I’m growing microgreens. Every couple of weeks they are sufficiently lush to be snipped and eaten. They sit on my nightstand, and there’s just enough light, coming from an adjacent window, to feed them. Outside that window, I can see a tree that is older than anyone I know. I photograph it frequently, watching it change with the seasons.

As much as I love plant life—trees and flowers—growing food is new for me. It comforts. It feels as though, in this uncertain time, I am connected to the ancestors, the way they’d often grow a little patch of something for sustenance. From the time when the Old South turned into the New South, which I suppose is now old again, most all Black folks spent a lifetime of scraping and scuffling. Land of one’s own was hard to come by. Despite how often the gospel of “get you some land” was preached, white supremacy wielded its power over the land. But even for the sharecropper, a little patch of something, a rectangle of dirt on which to grow greens, tomatoes, some cabbage, some berries, was protected and nurtured. Even when the dirt was hard and spent, black hands eked sprouts from it, tended them to fullness. And ate from the bounty.

By any measure of politics and civil order, Black people in the antebellum and Jim Crow South existed in a cruel relationship to land and the agricultural economy. Exploitation happened from birth to death, from the fields all the way to the commissary where people overpaid landowners for minimal goods. Black people gave birth in the cane, died in the cotton, bled into the corn. But out of little patches of something, carefully tended to because beyond survival is love, came reward. The earth gave moments of pleasure: Latching onto a juicy peach—your teeth moving from yellow to red flesh. Digging up a yam, dusting off its dirt, roasting it so long the caramelized sweetness explodes under your tongue. Running your hands across the collard leaves coming up from the ground rippled flowerlike. That green is as pretty as pink.

When the pandemic pushed people indoors, it seemed as though there was a quietly reached consensus that it was time to touch the earth anew. People posted images on their social media accounts of their seeds and sprouts and their little patches of something on balconies and in side yards. I joined this in my little corner as the world slowed down. As a nation we were already growing to understand the importance of sustainability and the existential threat of climate change. Community garden projects and recycling plans have proliferated over the past couple of decades. But during shelter in place it seems touching and tending to plants has become both more universal and more essential.

Soulful even. I watched my friends and family on screens as they delighted in collards, berries, tomatoes, and chives. Small joys as death rolled by. At first there was a rumor that Black people didn’t get COVID-19, as though by some miracle of our physical constitution. Then we were told it cast us all in the same boat, a virus couldn’t discriminate. Finally, we saw that though a virus doesn’t discriminate the persistent ways a society does had us falling fast. And it seemed we, Black people, all knew someone, or knew someone who knew someone, who died alone in a ward, or a home, or at home. Caresses of loved ones were verboten in the final moments. You had to stay safe from the virus.

This was the context in which the world shifted for the second time in the same season. Police officers killed Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and more, and more. So many in fact that even if I gave you the whole list I know I would be missing some precious lives that also deserve to be remembered. Being killed by police officers is the same old same old for Black people. Same rage, same sorrow, same politicians’ calls for quiet protest but never remedy. The protests grew like wildfire. People emerged from their homes, hungry to stand with each other, to beat back loneliness and fear, angry, resistant and insistent. From every quarter and dozens of states and nations, people have stepped outside to say:

“Enough!”

The plants are growing too. Their slowly spreading leaves are synchronous with the shattering glass, the rubber bullets, the gouged-out eyes, the tanks and bullhorns. That synchronicity is not new. When the Klan mobs charged into Black homes, ripping out someone who was loved, dragging them in the dirt, dismembering his body bit by bit before stringing him up, the turnips kept growing. When the bombs shook Dynamite Hill in Birmingham, and the hoses knocked over skinny brown children, the pecans fell from branches. Plums hung heavy, purple and sweet as hot rage bubbled from the gut through the vocal passages.

In the Black Belt of the South of the sixties, where land still stretches as far as you can see, the place where croppers who were kicked off their land for trying to vote, and where young freedom movement organizers were beaten and jailed, folks ate together in the evening. Sheltered from the harrowing night dangers outside, they ate from somebody’s little patch of something. Simply feted and protected by hands accustomed to subsistence labors, they were cared for.

I’m remembering all that, looking at my little tray of microgreens, sleepless with fear about the devastation just around the corner, yet hopeful too because the dam holding back rage has broken. I want to hold hands with my friends who have been tear-gassed and pepper-sprayed, who I have seen stumbling yet still holding a banner aloft: BLACK LIVES MATTER. The grace of a shared meal seems so remote now. But those days will return sooner than we think. And if this moment of righteous rage turns into a movement that will be sustained, we will need to both fight and nourish each other. We will have to bolster and build more networks to share food and provide care and shelter, not as an alternative to protest but as an essential element of it. It is a lesson we learned over centuries. Freedom dreams are grown and nurtured out of the hardest, barely yielding soul. Our gardens must grow. That is a metaphor and a literal truth. When the bruised and battered seek refuge from the storm, may all of us who believe in freedom remain ready to feed and sustain them.

Imani Perry is the Hughes Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and the author of six books, including the award-winning Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry and Breathe: A Letter to My Sons.

June 2, 2020

American Refugee