The Paris Review's Blog, page 165

May 18, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 9

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“ ‘To engage your humor and your emotions, that’s quite a trick,’ T. C. Boyle says in his Art of Fiction interview. ‘I’d like to think that I’m able to do that, to keep the reader off balance—is this the universe of the comedy or the tragedy? or some unsettling admixture of the two?—to go beyond mere satire into something more emotionally devastating, and gratifying. If that ain’t art, I don’t know what is.’ Paris Review humor aspires to strike that balance, pull off that trick: taking all the emotional and intellectual and aesthetic requirements of literary storytelling and throwing in what E. B. White calls ‘the sly and almost imperceptible ingredient’ of durable humor. This week, enjoy some levity on us. I think we could all use a few belly laughs.” —EN

I first fell for E. B. White as a little girl, upon reading Charlotte’s Web. I loved him again when, at the conclusion of my first editing job, at the Metropolitan Museum, my boss gave me Maira Kalman’s illustrated Elements of Style, by Strunk and White. I became a fan a third time when I realized White was Roger Angell’s stepdad: What were their dinner conversations like? Lively, based on some action-packed passages in his Art of the Essay interview. Punctuation has never been so threatening (“Commas in The New Yorker fall with the precision of knives in a circus act, outlining the victim”), nor children’s capacity for new vocabulary so vivid (“Children are game for anything. I throw them hard words, and they backhand them over the net”). Also not grandiose, based on his modest assessment of success (on reviving Strunk’s Elements of Style: “It cost me a year out of my life, so little did I know about grammar”) and his utter devotion to Katherine White. He also discusses midcentury satire, recaptioning cartoons, and other funny things in a charming, casual way that the interviewers George Plimpton and Frank Crowther describe as having the “off-hand grace” of an improvising dancer. I call it a fourth arrow in the heart. —EN

Miranda July—author, filmmaker, and humor connoisseur—has been a leader in quarantine morale. In late March, July held a ceremony for her very own COVID International Arts Festival on Instagram, clad in an oversize pink head wrap and her signature wire-rimmed glasses. This past week, she put out a casting call for a mysterious play or film she is producing entirely on social media. Mesmerized by July’s recent projects, I felt inspired to revisit two stories she contributed to The Paris Review in 2003, “Birthmark” and “Making Love in 2003.” In typical July fashion, the latter starts in medias res. A writer sits in her college adviser’s living room, waiting with his wife for him to come home. We are unsure why the writer is there, other than for some kind of help with her career. And it turns out, after a few forced pleasantries, that the college adviser’s wife is Madeleine L’Engle. It is impossible to summarize where the story goes next, but rest assured, this is the first of many unexpected, perversely humorous twists. July’s 2003 stories are absurd but highly logical—a blunt examination of power, sex, and the written word. —Elinor Hitt, Intern

Matthew Baker’s extraordinary satirical story “Why Visit America” was in the first issue I worked on when I joined the staff of The Paris Review, and I’ll admit that when I was setting it up for online publication, I did not like it—it’s a formatting nightmare, full of all kinds of headings and indents and special spacing that the internet simply wasn’t designed for. But then the author read a good portion of it standing atop the office pool table at our issue launch party, and I forgave the hours I’d spent fussing with nonbreaking spaces. This story—a tale of the birth of a brave new bureaucracy wrapped in a kind of travel guide—is, alas, a clear-eyed (and hilarious) view of the contemporary American mess through a pair of cracked rose-colored glasses. May it transport you, via the scenic route, to where you already are. —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Central to most humor is the element of surprise. No fiction writer has mastered this as gracefully as Joy Williams, whose sentences tumble off the page in dazzling, unpredictable sequences. “The Yard Boy,” which appeared in the Winter 1977 issue, is no less deadpan than the rest of her brilliant work, and each of the story’s paragraphs offers a lesson in subverting expectations. Consider this sequence: “Mrs. Wilson follows the yard boy around as he tends to the hibiscus, the bougainvillea, the jacaranda, the horse cassia, the Java flower, the flame vine. They stand beneath the mango, looking up. ‘Isn’t it pagan,’ Mrs. Wilson says. Close the mouth, shut the doors, untie the tangles, soften the light, the yard boy thinks. Mrs. Wilson says, ‘It’s a waste this place, don’t you think? I’ve never understood nature, all this effort. All this will.’ ” These turns and those that follow could be perceived as random, but they’re not. Every bit helps confound the reader. As in many of Williams’s stories, the reward lies in her ability to fully inhabit a scene until the hilarious truth begins to blossom. —Brian Ransom, Assistant Online Editor

Long after her death, Dorothy Parker is still overburdened with invitations to strangers’ ideal dinner parties, dreading another evening of tepid soup and burned stuffed peppers with Gandhi and Einstein and Shakespeare. In her Art of Fiction interview with Marion Capron, Parker acknowledges that her wit precedes her and deflates her: “ ‘Why it got so bad,’ she has said bitterly, ‘that they began to laugh before I opened my mouth.’ ” From her “Hogarthian” apartment, ruled by a poodle and decorated with an ominous painting of a sheepdog, she reflects on the burden of humor. “A ‘smart-cracker’ they called me, and that makes me sick and unhappy. There’s a helluva distance between wise-cracking and wit.” She effaces her wit, just as she demonstrates it: “Wit has truth in it; wise-cracking is simply calisthenics with words.” All this rings true. Now, why haven’t you touched your pepper? —Chris Littlewood, Intern

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

How to Draw the Coronavirus

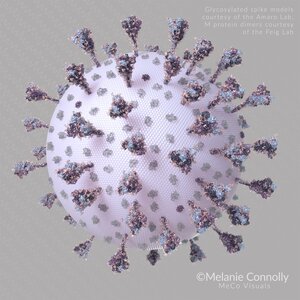

CDC rendering of SARS-CoV-2

The disease that has put the entire world on pause is easily communicable, capable of stowing silently away in certain hosts and killing others, and, to the human eye, entirely invisible. In media parlance it’s become our “invisible enemy”: a nightmarish, oneiric force that can’t be seen, heard, or touched. But with the use of modeling software, scientists and illustrators have begun to visualize coronavirus, turning it into something that can be seen, understood, and, hopefully, eventually vanquished by science. Many of us imagine the virus as a sphere radiating red spikes—but why? Certain elements of these visualizations are based on the way coronavirus appears under a microscope, and others are choices that were made, an exercise of artistic license.

On January 21, CDC illustrators Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins were asked to illustrate the novel coronavirus for use in press briefings and other media materials. Eckert came up with what she called a “beauty shot” of the virus molecule (referred to in the scientific community as a “virion”), a round globule with the crown-like array of spiked proteins that give the virus its name. Eckert and Higgins experimented with a number of color schemes until they settled on red and gray with orange and yellow accents. “It just really stood out,” Eckert told the New York Times. Since then, the illustration has saturated news outlets around the world.

“Their illustration kind of looks handsome,” said Dr. Timothy Mastro, former deputy director for science in HIV/AIDS prevention at the CDC. “It has a certain symmetry to it, an appealing design … [a virus like] Ebola’s just this twisted-up piece of spaghetti, not nearly as attractive.” Mastro recalls having seen artistic renderings of the HIV molecule on posters at the conferences he attended and on the covers of journals. The image, a sphere studded with spiked proteins, similar to the CDC rendering of coronavirus, gave a certain “character” to the disease he was researching. But in the lab, Mastro concerned himself exclusively with images of the actual virus taken by means of a process called X-ray crystallography. The process, in which the crystalline structure of the virion causes a beam of X-rays to diffract in many directions, allows researchers to construct an image of the molecule. The result is a ghostly black-and-white tracing of the invisible.

Mastro showed me an actual image of the coronavirus, the basis for all the colorful renderings I’d seen online. The molecules looked like the cartoon amoebas you’d expect to see in a fifties film reel about germs. But they were the virus qua virus, with its spikes and spherical body. Mastro explained that the spiked proteins connect to receptors on the outside of healthy cells so the virus can overtake the cell body and use it to replicate itself. A variation of these proteins, produced over years of replication, enabled the coronavirus to evolve from a harmless common cold into something capable of devastating the upper respiratory system. I asked Mastro why so many of the illustrations of the coronavirus look different from the CDC version, and one another, given that everyone was working off the same micrograph. “Artistic license,” he said.

iSO-FORM LLC’s rendering of SARS-CoV-2

Nick Klein and Jamie Vitzthum, part of an LLC of scientific illustrators called iSO-FORM, thought very deliberately about the protein spikes in their rendering of coronavirus. The E-protein, the orange spike in the rendering, is taken from models of the SARS-CoV virus, an ancestor of coronavirus that was first reported in Asia in 2003 (the scientific term for coronavirus is SARS-CoV-2). The concept for the M-protein, the green spike, was obtained through something called “predictive neural net processing,” which maps out the full structures of proteins before they have been determined in the lab. Additionally, Klein told me that coronavirus is pleomorphic, meaning it can vary in shape. To communicate that, he and Vitzthum rendered it as ellipsoidal. “Our editorial choices in colors and style emphasize the virus’s structural complexity and aggressive protein configuration, but also hint at its frail nature outside the body,” Klein told me. “With all the fear, death, and tragedy it has caused, it is not a living thing and has no capacity for malice … with perseverance and innovation, humanity can overcome this thing.”

Melanie Connolly’s rendering of SARS-COV-2

Melanie Connolly doesn’t completely agree with Klein’s assertion that the virus isn’t a living thing. “People go back and forth on this,” she said. “Some people think viruses aren’t living because they can’t replicate themselves without another organism’s machinery. But then bacteria use the same method of replication, and they’re considered living things.” Her rendering of the virus is all pastel purples and blues. The “confirmation,” or shape, of the protein spikes is clearly visible as a three-pointed braid. Although just as symmetrical as the CDC rendering, Connolly’s is far more pleasant, like a space crusader’s mute sidekick, a friendly being from another planet—the virion does seem to be, in a manner of speaking, alive. The colors were designed to match what Connolly calls her “aesthetic brand”: she does a lot of illustration work in the realm of women’s health, and wanted to carry the pastels over to this project. “The audience [for this illustration] is scientifically minded, has an interest in the research, but aren’t necessarily researchers themselves,” she said. She imagines the advanced high schoolers in her summer microbiology courses would be particularly interested in this rendering. Connolly sees her illustration work as a form of public education, describing her virion as a simplified version of “Moonlight Sonata”: the beginning pianist learns how to play the basics before being introduced to more challenging versions of the piece. Connolly’s virion meets the scientifically curious right where they are by being rigorous but not prohibitively complex. This is, I imagine, one of the major advantages of artistic license.

Jane Whitney’s rendering of SARS-COV-2

When Jane Whitney and I spoke, I offered her Mastro’s postulation that all depictions of coronavirus differed because of artistic license. She said there were reasons for difference beyond that: people sometimes don’t understand or don’t want to be constrained by molecular visualization, the process by which software is used to create an accurate 3D model of a protein structure. “My [protein] spikes are definitely an abstracted representation of the actual spike structure,” she said. Whitney’s drawing of a coronavirus molecule binding to a healthy cell is two-dimensional and highly stylized: it’s easy to understand, like a graphic from an AP biology textbook. This doesn’t mean that Whitney overlooked molecular visualization, however. She showed me the scientific papers she’d pored over to understand the structure of coronavirus proteins and the organization of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (a virus’s form of DNA). She has used 3D rendering to create a kaleidoscopic and rather lovely animation of a SARS-COV-2 protein spike.

[image error]

Jane Whitney’s 3D rendering of a coronavirus protein spike

Then she showed me how she’d simplified 3D renderings of the three-stranded, torch-shaped protein spikes created by someone else into what looked like a bundle of differently colored Y’s.

Jane Whitney’s illustration of a coronavirus spike

Jonathan Corum, who illustrated the virus for the New York Times, also wanted to produce a stylized version of the virion that would be easily digestible by a wide audience while remaining rigorous in terms of molecular structure. He had begun with the CDC illustration and then “smoothed out the bumps and stylized the spikes.” His virion has the feel of a soccer ball that’s acquired superpowers as the result of radioactive fallout. “[Since] the coronavirus is named after its crownlike halo of spikes, adjusting the spikes is an easy way to give the virus some personality,” Corum told me. “Personality” here means any detail—whether it be the color palette or the shape of the spikes or the width of the sphere—that the viewer’s eye can affix itself to and remember. “The CDC illustration is both yarn-like and sinister, which is an interesting combination, but I wanted something crisper with a bright red that almost vibrates onscreen,” he said.

Johnathan Corum coronavirus sketch

Veronica Falconieri created, like Whitney and Corum, a detailed infographic of the virus’s process of fusing with and infecting healthy cells. Unlike Whitney’s or Corum’s, Falconieri’s rendering is three-dimensional and intended as a reference for fellow medical illustrators and scientists. Falconieri’s sophisticated-looking spikes describe “S1/S2 domain difference” and “sites of glycosylation”—certainly more detail than I’d seen on any other rendering of the virus—but my humanities brain was distracted by the pleasant-looking cotton candy nature of the spikes and the relative smallness of the sphere. Falconieri said she’d consulted the CDC rendering as well as an illustration made by a professor of computational biology named David Goodsell before embarking on the twenty-seven-hour process of research and illustration. While the structure of Falconieri’s spikes is based on studies of SARS-CoV-2 proteins obtained through cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (an alternative to X-ray crystallography where electrons are used to illuminate molecules kept at cryogenic temperatures) the body of the virion is based off images of the older and more researched SARS-CoV, simply because there isn’t similar data yet for SARS-CoV-2. “There’s still a lot unknown,” she said, adding that many scientists have just recently pivoted to coronavirus research. “There’s so much to worry about and so little to do these days—[this illustration] was a small thing that I could do to contribute with my particular skillset.”

Veronica Falconieri infographic

In an attempt to locate Falconieri’s influences, I searched for Goodsell’s illustration, expecting to find an anatomized rendering of the virion. What I found instead was an intoxicatingly beautiful, quasi-psychedelic painting: something you would be as likely to see through a microscope as through hallucinogens. Goodsell—who has produced similarly stunning images of Ebola, zika, and HIV, among other things—visits, like many illustrators, a protein-visualization site called Protein Data Bank for structural reference and PubMed for research on viruses before he draws them. He then sketches the virion—the large picture first, small details last—and paints the sketch with watercolors. “I find that the cartoony, flat-color approach that I use makes it easier to comprehend the whole scene,” he wrote in an article for the Journal of Biocommunication.

David Goodsell’s rendering of SARS-CoV-2

When I told Goodsell that I thought his painting of coronavirus was a work of art, he gently reminded me that the illustration is “very much tied to science … I always want [the illustrations] to be as accurate as possible, and I want them to help people understand the biological processes that are shown.” He hopes to put a face to coronavirus, to help the public conceive of it as “a physical entity, with size, shape and properties that can be understood.” The motivation and constraints for art, he said, are entirely different, though he does appreciate it when viewers recognize his love of color and design. When comparing the CDC rendering of coronavirus to Goodsell’s, art critic Philip Kennicott described the former as “clearly emphasizing the threat this virus poses to those who refuse to, or cannot, socially distance themselves,” and the latter as “a thing apart, to be studied, anatomized, and understood.”

Selections from David Goodsell’s coronavirus online coloring activity

Goodsell is active in using his illustration to spread scientific awareness of coronavirus. In an article he coauthored called “An Integrative Approach to SARS Coronavirus Outreach,” he includes templates of his virion colored in by children and adults. Comments on his illustration range from “Things seem less scary when they’re colorful” to “Art is the work of transforming fear and pain into beauty.” Parents wrote him about helping their kids declassify coronavirus as an invisible enemy and having family conversations about what the virus looks like and how it “just requires the right tools to see.” In the early stages of the pandemic, one parent wrote Goodsell about a child who was sick with worry, unable to comprehend why his school was going to close soon. “So I told him all about viruses, what they are and what they do,” the parent wrote. The next day, the boy arrived at school feeling much better, carrying in his backpack enough coloring book copies of Goodsell’s virion for his entire class.

Rebekah Frumkin’s novel, The Comedown, was published by Henry Holt in 2018. She is an assistant professor of creative writing at Southern Illinois University.

Not for the Fainthearted

Jon McGregor. Photo: Jo Wheeler.

I have been thinking lately of a verdict given to the adult world by a young girl in Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows. “Mary had once said … that the adjectives which really suited grown-ups were ‘lily-livered’ and ‘chicken-hearted.’ ” At the risk of making a disputable comment, I wonder if, compared to the West characters from a century ago, we may be more than ever afflicted by this disease of lily-livered-ness and chickenheartedness, at least in our literary taste. Oftentimes a reviewer feels the urge to warn the readers that such and such a book is “not for the fainthearted”—as though it’s literature’s job to put a cautious finger on the readers’ pulses. Woe to those sacrificed maidens in Greek tragedies and lopped-off heads in Shakespeare plays that fail to bear a sign: TRIGGER WARNING.

The Greeks and Shakespeare, of course, are still being read, perhaps for the reason that it’s easy to forget that they wrote about real people who once lived. Thank goodness we have books like Jon McGregor’s Even the Dogs, a reminder that true literature does not avert its eyes from anything difficult.

The novel is narrated by a group of characters, some named, others unseen but to themselves. Together they are known—because society must offer a label for them—as drug addicts, alcoholics, and homeless people. It may be easy to compare the group “we” to the chorus in a Greek tragedy, but the novel does not allow the readers to find a retreat in the realm of myths, fairy tales, or fantasies. We are, of course, familiar with the gritty and gory images, which are often seen these days on screen—with perfect makeup and the right music so well done that the audience can keep an aesthetic and psychological distance. But McGregor’s novel, with its uncompromising gaze at unadorned details of life and death, eliminates that safe distance between the characters and the readers. Who can say he or she is guaranteed to be free from the characters’ fates? A reader who waves a white flag of lily-livered-ness and chickenheartedness even before opening the book, perhaps.

Even the Dogs opens on a winter day when a body is discovered in an unheated flat. The novel unfolds as the narrators follow the body from the flat to the mortuary, watch it being examined by the coroner and then prepared for cremation, and, holding a wake while remaining entirely invisible to the world, search in their own muddled minds for clarity. The only character who progresses lineally in time is the body, as the dead no longer has the means to change his own destination. This reliable odyssey anchors the readers as it anchors the narrators, whose relationship with time is much murkier. But that, even for those in the direst situation, is a privilege. Time works magic—a cliché, yet time, for the living characters as well as the readers, does hold the unexpected and the unreliable: it circles, superimposes, inlays, and traverses back and forth in years. Like memory, but even less subjected to anyone’s control.

The setting of the novel is an unspecified city in England, but it may as well be set in a town in Ohio or on a street in Chicago. No one needs a passport or a legal document to cross the border between hope and despair, between forgetting and remembering, between life and death, or, perhaps more relevant for the characters (and the readers, too), between desire and addiction. So often addiction is portrayed as a result of poverty or hopelessness, or, in kinder hands, a mental illness. McGregor has not limited himself to those easy answers. He has shown something else—messier, yet more intense—at work: the desire to feel. Can any reader look into his or her own mind and deny the presence of that desire entirely?

Even the Dogs deservedly won the International Dublin Literary Award in 2012. One can go on talking about McGregor’s other brilliant books, including his latest, Reservoir Thirteen. But what strikes me most is his intelligence, which one senses vividly in his prose, and his empathy, which he’s given entirely to his characters, rather than to, say, the readers or the publishers. That, to my mind, makes a superb writer rather than a gifted caterer.

Yiyun Li is the author of five works of fiction—Where Reasons End, Kinder Than Solitude, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers, The Vagrants, and Gold Boy, Emerald Girl—and the memoir Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life. She is the recipient of many awards, including a PEN/Hemingway Award and a MacArthur Foundation fellowship. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, A Public Space, The Best American Short Stories, and The O. Henry Prize Stories, among other publications. She teaches at Princeton University and lives in Princeton, New Jersey. Her new novel, Must I Go, is forthcoming from Random House on July 28, 2020.

Introduction to Jon McGregor’s Even the Dogs © 2020 Yiyun Li, used by permission of the Wylie Agency LLC

May 15, 2020

Staff Picks: Costa, Candles, and California

Eimear McBride. Photo: Sophie Bassouls.

I have been a fervent fan of Eimear McBride ever since I first read her debut novel, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing. Strange Hotel, her latest, does away with the stream-of-consciousness style she first became known for, but it’s no less recognizable in how it explores regret and memory. The plot is simple: A nameless woman checks into a hotel in Avignon, a hotel she’s been to before. She smokes, drinks too much, watches pornography on the hotel television. Her thoughts drift to all the hotel rooms she’s stayed in over the years, hotels all over the world. One hotel, in Austin, stands out; in that particular hotel, a particular man. McBride is skilled at the language of regret, the language of turning a situation over and over in your mind, suffusing it with an increasingly deflated sense of possibility. And for the reader, this is a novel to be mulled over long after it has ended. —Rhian Sasseen

In George Sluizer’s 1988 film The Vanishing, a young Dutch couple named Saskia and Rex drive through the French countryside on holiday. When they stop at a gas station, Saskia runs in to grab some drinks; she never comes out. Out of the many, many films I’ve watched in the past seven weeks, this is not one of the more joyful. But it is the one I’ve found myself thinking about nearly daily since viewing. The Vanishing captivates like a classic thriller but leaves you thoughtful in ways that Basic Instinct may not. The film is an examination of the ways in which hope can be dangerous; Rex never stops searching for Saskia, his life consumed with questions of what happened to her. Although the film spans languages (both Dutch and French), countries, and years, it remains profoundly claustrophobic, owing in part to the plot but mostly to the small cast of exceptional actors. Gene Bervoets and Johanna ter Steege as Rex and Saskia are transformed from a bickering couple to adoring lotus-eaters to two people ripped apart by unimaginable cruelty within a mere twenty minutes. Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu’s quiet but deeply terrifying performance has stuck to my bones, creating a Pavlovian shiver whenever he comes to mind. If I haven’t made the film sound like a treat to watch, that’s because it’s not, at least not in the traditional sense. Sluizer builds dread like a mastermind, composing shots lit by neon browns and purples so drenched in rain they’d look at home in a nightmare Impressionist painting. Layered atop it all is Henny Vrienten’s eerie electronic soundtrack. Watch this film early in the evening so you can palate cleanse with something cheerful afterward—you’ve got time. —Eleonore Condo

Issa Rae and Yvonne Orji in Season 4, Episode 3 of Insecure. Photo: Merie W. Wallace/HBO.

These days I leave my apartment only rarely, and when I do it seems like New York is actively resisting the idea of summer. So even for a creature entirely of the East Coast, there has been something particularly beguiling about the latest season of Insecure: those wide-open California landscapes, the sunshine, a strange world in which people talk to each other, touch each other, gather together. At this point it feels almost like a fantasy universe, but Insecure is one of the realest, most forthright shows on TV. This season trains that candor on an increasingly strained friendship between Issa and Molly, showing each hairline fracture and how it might explode. Ever since the first line—Issa on the phone with someone we don’t know, saying, “Honestly, I don’t fuck with Molly anymore”—I’ve been holding my breath, hoping that by the time the season ends they’ll have put themselves back together. —Hasan Altaf

On Sunday night, the pianist Serene sat before her instrument in a dimly lit room, ready to perform the most recent installment of Fever’s Candlelight Concert series online. The floor was covered in candles as promised, and her piano was situated between a brick fireplace and glass doors that looked out onto the night. To match her dark outfit and elegant frame, Serene played a Bogányi piano, a blue-black structure that looks like it could have been built by Noguchi. In fact, it was conceived by the Hungarian designer Péter Üveges and equipped with a carbon fiber soundboard, making for a clear and resonant sound. After opening with Ravel and Chopin, Serene performed the aria from the Goldberg Variations. She worked the keys with an Apollonian restraint, her two hands playing together as if in casual conversation. A pairing of sonatas by Beethoven followed—op. 31, no. 8, “Pathétique,” composed early in his career, and op. 111, no. 32, which was composed after he had suffered significant hearing loss. Serene urged that we consider Beethoven a master of improvisation—a designation not commonly given to classical composers. But she drove the point home with swinging tempos and athletic trills, positing Beethoven as a classical antecedent to jazz. Then came Liszt and Gershwin, and the concert concluded with a heartening round of “Rhapsody in Blue.” I last heard “Rhapsody” on a summer evening in Central Park, the New York Philharmonic playing as fireworks boomed above the southern skyline. Unsurprisingly, Serene performed a spectacle to match. Watching Serene play is like watching Jackson Pollock paint; she lifts her hands high and strikes the keys with intention, producing an ordered and harmonious spattering of notes. Her next performance with Fever will be streaming on May 24. —Elinor Hitt

Vitalina Varela appears, silhouetted and barefoot, at the open door of an airplane, awaiting a stair car. She descends, to be met with condolences from a group of women on the tarmac. She has waited thirty years for a plane ticket to Portugal, but her husband, who left her in Cape Verde, died three days earlier and has already been buried. There is nothing here for you, she is told—go home. It is a sentiment that she encounters repeatedly in Lisbon. A priest, himself from Cape Verde, tells her the memory of her husband’s immigrant life—“It’s poison!” Why are you taking their side? she asks. She sits alone, unwelcome in her husband’s ill-fitting house, and declares she will die in Portugal. Specters abound. In this film that bears her name, Vitalina Varela plays herself, tells her story, and shares a screenwriting credit with the director, Pedro Costa. (The film is streaming from the distributor’s website; profits are split with a cinema of your choice.) Portugal’s legacy of dispossession, colonial violence, and marginalization is everywhere apparent and persistent. Over the years, Costa has made a series of films about the inhabitants of Fontainhas, an impoverished district of Lisbon, that also chart the neighborhood’s destruction. Now his films seem to take place in a nocturnal netherworld. Neither documentary nor fiction, they have little interest in delineating reality from imagination, dream from memory, or the stories people tell about lives from the lives they lead. Vitalina Varela is glacial and remote, like Europa; it is so much an art film that when I saw it in the cinema, I could hear furious scribbles in a notebook above my neighbor’s gentle snores. There is little continuity or sense of space. People do not converse; they offer testimonies and recite dates, expenses, detritus. It is also a film of flabbergasting beauty. Much of the time is spent with Varela in darkness, yet the film never allows for the easy illusion of empathy or understanding—rather, we see her solitude without intruding on it. The style might impose a cruel despair, the stillness a complacency, were it not for Varela’s sublime performance and a conclusion that adopts her own faith in grace—a gesture of solidarity and an emergence into the light. —Chris Littlewood

Vitalina Varela in a still from Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela. Courtesy of Grasshopper Film.

Family Photographs

Beth Nguyen’s essay “Apparent,” on her absent mother and piecing together a fractured past, appears in our Spring issue.

Family photograph (©Beth Nguyen)

I have no pictures of myself as a baby. I was born in Saigon during a war, and was eight months old when my family became refugees; my memories begin in a worn-down house in a deeply conservative town in Michigan, where we were resettled.

Photographs were expensive then, so we had few of them. The Polaroid colors are muted and mottled, an expression of what it felt like to grow up in a Vietnamese refugee family surrounded by whiteness. It has taken my entire life to understand the beginnings of this awareness. It began with watching my father go to work at a feather factory and come home with down in his hair. My uncles, who shared the house with us, worked different shifts at different factories. They saved money to buy records. My grandmother Noi took care of me and my sister. She knitted us ponchos out of marled yarn, let us wear fuzzy pink slippers into the snow.

I didn’t know what it meant to be a refugee, but I knew we were different because on TV shows everyone else spoke another language. My sister and I learned English this way. I don’t remember wondering where my mother was or realizing she was still in Viet Nam. I didn’t even know what a mother was until I was told. My grandmother would give whole apples and pears to my sister and me, knowing that we would save them. We were always waiting for someone to come home.

All family pictures create a chronology. But I realize only now that the pictures we took and kept were a space just for us. White people determined so much about our lives—jobs, schools, language—but not in these photos. In these images we seem to be in our own world, alone together. It’s such a short time. By the last picture, it’s over.

Why are my father, my sister, and I hanging out on this car? Whose car is it? (It’s not ours.) Why are we dressed like this? Where did my father get that fantastic cardigan? This is my favorite photo because it is unfamiliar to me every time I see it, yet the sky looks the way I remember my childhood. I am two or three years old here, too young to remember this scene itself. I want to believe there was joy and relaxation—my father, barefoot as he loved to be—even though that’s not what I associate with growing up.

This is what my life was like until I left for college: a book in one hand and a television nearby. I didn’t know it then, but my obsession with words was a method of survival. I read every bit of English I could find: instruction manuals, newspapers, the backs of cereal boxes, library books. I studied the diction of actresses on shows like The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I cared more about words than about what I wore, but I loved this dress and I still do. This is probably the cutest picture I’ll ever take.

My grandmother Noi always wore an áo dài whenever we left the house. It wasn’t to be fancy or to call attention to herself; it was to be Vietnamese. Inside the house, she wore flowing polyester pants and a light tunic, adding a hand-knit cardigan in the colder months. She made all of her clothes herself. This was how I knew her, from my first moments of consciousness to the day she died at age eighty-seven. She would take us to parks and watch TV with us but never spoke to us in English. When white kids made fun of her, she understood the racism but often laughed at it, a light laugh that conveyed dismissal. She’s been gone for more than ten years now and I am still in awe of her.

In truth, my sister was more cheerful. I looked to her to figure out what I should feel instead of what I was feeling. She was the one who said we should save the fruit that our grandmother gave us. It was a treat just to hold the apples and pears. We didn’t even know how to eat them whole. We thought fruit had to be sliced before it could be eaten; it had to be set forth on little plates, because that’s what our grandmother did. I think I was twelve before I bit into a whole apple.

Fast forward to age eight, maybe nine? That’s the year I’m obsessed with Pez dispensers, the neatness of the form. I have nail polish on because my sister makes me, but really, I hate it. Still do. I’m watching this face and body painting but I won’t participate. I can’t bear the feel of it, don’t want someone else drawing on any part of me. I am at this age already so much who I will become.

Read Beth Nguyen’s essay in our Spring issue.

Beth Nguyen is the author of the memoir Stealing Buddha’s Dinner and the novels Short Girls and Pioneer Girl. She is the recipient of an American Book Award, and a PEN/Jerard Award, among other honors. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies and publications including the New York Times, Literary Hub, and The Paris Review. She is at work on a series of linked essays about post-refugee life, titled Owner of a Lonely Heart.

Graciliano Ramos and the Plague

Graciliano Ramos.

In 1915, long before he became one of Brazil’s most acclaimed novelists, Graciliano Ramos was a young man trying to make it as a journalist in Rio de Janeiro. I’d always heard that he failed in his pursuit of this career. Shy, homesick, and unsuited to the sophisticated conditions of big-city life, he was a thousand miles and a world away from his remote provincial hometown of Palmeira dos Índios, located in Brazil’s dry northeastern interior. I imagined him beating a retreat, returning to become a shopkeeper like his father before him, getting cranky at customers who interrupted his reading.

In 1928, though, Ramos was elected mayor of Palmeira dos Índios and, by this unlikely route, came into national literary prominence. As a municipal leader, he was required to submit annual reports to the State of Alagoas on budgets and projects, income and expenditures. He treated these reports as a kind of formal challenge. In a narrative divided into subheads such as “Public Works” and “Political and Judicial Functionaries,” he sketched drily hilarious portraits of small-town life, rivalries, corruption, bureaucratic waste. The reports went viral—to import an anachronism—circulating around the country in the press and attracting a publisher’s query: Had he written anything else, by chance? His first novel, Caetés, was published shortly after, launching a luminous literary career.

Ramos would eventually write three more acclaimed novels, a childhood memoir, a monumental account of his incarceration during the Vargas dictatorship, and numerous short stories, essays, and children’s books. A 1941 national literary poll named him one of Brazil’s ten greatest novelists. His influence in the years since has been profound and enduring. Most educated Brazilians have read at least one of his books. His last novel, Vidas secas (Barren Lives), has gone into more than a hundred editions.

Recently, though, I learned that a viral narrative of another sort lurks within his story. After a year in Rio working as a typographer and then proofreader with multiple newspapers, the young man who lamented his timidity in letters home received some ego-boosting news: a number of his nonfiction pieces would shortly be republished in Gazeta de Notícias, one of the most prestigious newspapers of the day. Things looked hopeful, but fate soon intervened. In August 1915, Ramos’s father telegrammed to say that three of his siblings and a nephew had all died in a single day from the bubonic plague then ravaging Palmeira dos Índios. His mother and a sister were in critical condition. “There was no longer any way for him to remain in Rio,” the biographer Dênis de Moraes writes in Velho Graça, his account of Ramos’s life. Ramos abandoned his big-city ambitions, boarded a boat home, married his local sweetheart, and settled down. He wouldn’t move back to Rio for twenty-three years.

I translated Ramos’s municipal dispatches because they’d never been published in English and I love their outraged rectitude and sly humor. Learning about the role of the plague in his biography, though, shifted my view on one mayoral passion that stands out in these reports: hygiene. “I care deeply about public sanitation,” he declared in the 1929 report. He had communal washrooms built; he passed laws against littering. “The streets are swept. I have removed from the city the garbage accumulated by generations who have passed through here, and have burned immense trash heaps, which the Prefecture can’t afford to remove.” He got sarcastic when he mentioned detractors: “There are moans and complaints about my having messed with dust preciously saved up in back gardens; moans, complaints and threats because I ordered the extermination of some hundreds of stray dogs; moans, complaints, threats, squeals, screams and kicks from the farmers raising animals in the town squares.” (I’d forgotten about the dog killings when I read some of my translation of the 1929 report aloud to my kids. They’d been laughing along till then, but now decided they hated this guy. If only I could have explained that dogs can carry fleas and fleas can carry plague and plague decimated the author’s family. Or maybe I should have just skipped that bit.) Ramos even fined his own father for violating the law against letting pigs and goats roam the streets of town. When his father complained, he retorted: “Mayors don’t have fathers. I’ll pay your fine but you will round up your animals.”

Although he’s still admired for the work he did as a mayor, Ramos got out of that game after two years. His writing career had taken off, though he netted more critical plaudits than cash in his lifetime. I’m sure the writer in him enjoyed the acclaim, but as a father of eight, he had bills to pay. By 1950, he was living once more in Rio and well-connected in the literary community, and so was offered the chance to translate Albert Camus’s The Plague into Portuguese. I’d previously assumed Ramos took on the project out of an interest in Camus. On learning about his own tragic losses from the plague, I speculated that he might have been drawn to the novel for what it says about the illness, perhaps even as a charm against some fear at having once more come south, away from his home region.

As it happens, I didn’t find much proof for either supposition: the critical consensus seems to be that, as one of Brazil’s best-regarded novelists in a time when publishers wanted to bring more contemporary foreign literature to the Brazilian reading public, he was commissioned to translate The Plague, though his name wouldn’t appear in the book itself until the second edition. Ramos was originally reluctant—he in fact didn’t think much of Camus’s writing, finding it too ornate—but he needed the money. His solution was to retool the novel, sentence by sentence, in the image of his own chiseled prose—to effectively, as the critic Cláudio Veiga put it, treat Camus’s novel as though it were an early draft of one of his own.

The Plague starts out with a description of a place that sounds familiar to readers of Ramos’s books: an isolated provincial town where people are bored, where they work a lot, “interested most of all in commerce—business keeps them busy, as they like to say.” Camus’s narrator is a reluctant amateur writer, unidentified until the very end. (Ramos, too, centered a couple of his novels on amateur writers, indirectly addressing, as does The Plague, problems of self-expression and storytelling legacies.) We know the narrator is a resident of this place—Oran, on Algeria’s northern coast—left to chronicle the mayhem wrought by an outbreak of the bubonic plague. He frequently slides into the collective first-person, speaking of “our town” and “our citizens,” though he refers to himself in the third-person. Among Ramos’s many modifications to Camus’s style and delivery is the elimination of those our’s and we’s, effacing the sense of community that comes along with those pronouns. And Ramos reduces: he boils sentences down to their essences, not only rendering the narration more distant but making the novel overall terser and tighter.

It was no more rigorous than the process he used for his original prose, which he—no surprise—described in terms of hygiene. As he famously said in a 1948 interview:

Writing should be done the way Alagoan laundry-women do their work. They start with an initial washing, wetting the dirty clothes at the edge of a pond or stream, wringing out the cloth, wetting it again, then again wringing it. They blue it and soap it, then wring it, once, twice. After rinsing it, they wet it again, this time by throwing water on it. They beat the cloth on a slab or rock, then wring it again and again, wringing it until not a single drop of water drips from the cloth. Only after having done all this do they hang the clean clothes on a washline to dry.

Scrub it, pound it, hang it out to dry: that, apparently, was his translation approach as well. I couldn’t help noting a certain irony, reading all this as his translator: I was motivated in large part to translate Ramos into English because I felt he’d been ill-served by translators insufficiently respectful of his stylistic exactitude. And now here he was, radically modifying a French Nobelist who was equally deliberate in his stylistic choices.

But none of Graciliano Ramos’s translators, present company obviously included, have been among their nations’ premier novelists. So when we ask what Ramos was doing, shrinking Camus’s sentences like a mad laundress, reshaping them to his own constricted vision, we need to remember that it’s as if a late-career Faulkner (to whom Ramos has often been compared for his stark illuminations of an isolated region) were translating him. We’d likely be unsurprised by the hubris and curious about the result.

Many dogs are shot in The Plague. Cats, too. But it’s when the rats start reappearing, scurrying from place to place, busy with their business, that the townsfolk of Oran realize life as they knew it is once more resuming. Toward the end of The Plague, Oran’s citizens “threw themselves outside, in this breathless minute when the time of suffering was about to end and the time of forgetting not yet begun. There was dancing everywhere … The old smells, of grilled meat and aniseed liquor, rose in the fine, soft light falling on the town. All around him, smiling faces turned up toward the sky.”

Ever since Susan Sontag crystallized the idea in “AIDS and Its Metaphors,” it’s become a commonplace that we think of plagues as invasions. “One feature of the usual script for plague: the disease invariably comes from somewhere else,” she wrote, listing fifteenth-century names for syphilis—the English called it the “French pox,” while it was “morbus Germanicus to the Parisians, the Naples sickness to the Florentines, the Chinese disease to the Japanese.” We want to believe that plagues visit or are visited upon us from afar, that they are not our own, much less our own fault.

Camus’s radical innovation was to show the plague as arising spontaneously from within Oran’s population—the book ends by saying the bacterium can lie dormant for years before “awakening its rats to bring death to some happy town”—though since the book is most often read as an allegory of the Nazi occupation of France, the alien-invasion metaphor isn’t much of a reach. But what do you do if, like Ramos, you’re trying to define and valorize a national literature in a country still emerging from colonization, when you can’t make a living from your own writing (even though you think it’s going to make a mint after you die) and your publisher wants you to help popularize European writing by translating a plague-y French novel? Maybe you make that novel your own.

Despite its final, dark notes of warning, The Plague is interested in being reassuring in a way that Ramos rarely is. Camus’s narrator tells us he wrote this account as a testimony to the injustice and violence suffered by Oran’s citizens and “simply to say what a person learns in the midst of an epidemic, that there is more in men to admire than to despise.” Ramos’s novels tend to be circular, not linear. They don’t end with faces upturned toward the sun and encomia on man’s essential goodness. Rather, his books bear witness to the marvelous unseen ways people struggle against their fate and fail to change it, because of their own blindness as much as anything. His characters, despite their ambitions, never quite triumph over human nature, their own natures, or nature itself; plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

When Camus’s narrator comes clean about his identity, we learn he is not, paradoxically, either of the two men we have seen actually writing. One of those, who has spent years compulsively revising the first sentence of what will surely be his magnum opus if he can ever make it beyond that opening line, finally achieves some small measure of satisfaction: “I’ve cut all the adjectives,” he says—words Ramos could have lived by.

Padma Viswanathan is the author of two novels, The Toss of a Lemon and The Ever After of Ashwin Rao, as well as plays, personal essays, cultural journalism, and reviews. Her short stories have appeared in Granta and The Boston Review. Her translation of the Graciliano Ramos novel São Bernardo was recently published by New York Review Books.

May 14, 2020

Inside Story: A Wrinkle in Time

In the column Inside Story, parents share the books they are reading with their children to get through these times.

About fifteen years ago, when I was fresh out of college, I taught middle school, sixth and seventh grade English. It was a trip. I knew nothing about anything, let alone the thematic depth of The Red Badge of Courage or all the things a noun can be (person, place, idea, emotion, name, et cetera). I spent my first year, as I imagine many novice teachers do, just trying not to drown. Mostly, I was terrified that my students would find out I barely knew what I was teaching them. I’d stay up late the night before, read a few chapters ahead, and then put together a weekly assignment sheet that suggested an authority I did not have. The next day, we’d go over their homework, and I’d stand at the front of the class sweating through my blazer and praying my voice wouldn’t break. Then I’d preview the coming unit as if I really knew the future, feigning confidence, meaning to reassure them. I could see the path ahead absolutely, could see it all the way to its glorious end in June.

When the lockdown began in Oregon, when it became clear that my five-year-old daughter would not be returning to school for the year, I thought back to those early teaching experiences. It seemed I was again in the same boat: unprepared, ill-equipped, drowning in my own ineptitude. My only option was to do as I had done before, to try as hard as possible. For a while, I really did. I made a schedule that transitioned her, every thirty minutes, from “educational” iPad games, to some kind of art-making, to free play, to basic math, and so on. That lasted one week. My own work piled up (I’m fortunate to be an instructor at a university, and my teaching, like everyone else’s, has gone remote). I decided very quickly to scale back, to ask one thing of her a day. I decided we would try, for the first time, to read a chapter book together.

We didn’t choose Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time for any other reason than it was already in our house. A friend had gifted my daughter the complete series for Christmas. My daughter can sound out words fairly well. The struggle is, of course, with patience, with seeing a new and unfamiliar term and not allowing its length and phonetic combinations to overwhelm her. The work is slow, and I remember from teaching middle school that I must marshal my own patience before I can help with hers.

Together, we attempt a chapter a day, often less. I ask her to read or sound out only four sentences during each session. If she does this, she earns a piece of sugarless gum as her prize, which she loves because she desperately wants to figure out how to blow bubbles. She can’t always sit still while I read, so she wanders about the room, touching scattered stuffed animals, rearranging LEGO sets, putting her model horses in a row and making them eat hay. I sometimes quiz her to see if she’s following along. She always is. She recalls everything without effort, and it startles me, the dynamism of her memory:

“Who’s Charles Wallace?” I ask.

“Meg’s little brother,” she replies.

“What does Meg’s mother do for a living?”

“She’s a scientist.”

“Where is their father?”

“He’s missing.”

Rescuing the disappeared Mr. Murry is, ostensibly, the great aim of Meg and Charles Wallace in A Wrinkle in Time. Yet it is not the most palpable conflict in the novel. In fact, the father is found rather easily. The children, along with their friend Calvin, are sent—by the supernatural Mrs. What, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which—to Camazotz, the planet on which he is being held hostage. And when the time comes, Meg has only to don Mrs. Who’s glasses to see and reach her father, to pull him from the mysterious column in which he is imprisoned.

The joy of his emancipation is short-lived. Mr. Murry doesn’t realize that the villain of the story, IT, has taken control of Charles Wallace. He doesn’t understand how two of his children have traveled to this strange planet. He has no idea who the three Mmes. W’s are. He fails to comprehend all that Meg tries to explain, so his confusion—beautifully, dishearteningly—echoes all the other instances in the novel when the characters struggle to communicate: Mr. Jenkins, the principal at the children’s school, makes “snide remarks about Father” instead of empathizing with Meg. Charles Wallace and “the man with the red eyes” spar with memorized language, with nursery rhymes and multiplication tables. Even the children’s guides, the powerful Mmes. W’s, “find it difficult to verbalize.” Mrs. Who converses only in quotes from literature and Mrs. Which talks at a snail’s pace. The great tragedy of A Wrinkle in Time proves not to be the splintered family or even the Black Thing, but the difficulty of children and adults speaking to one another.

While reading the novel with my daughter, I’ve often wanted to cry out at the grown-ups, who are at times taciturn, at times simply inarticulate. But their struggle is my own as a parent, the seeming impossibility of explaining the world to my child. It seems fitting that the immortal Mmes. W’s bring Meg, Calvin, and Charles Wallace to the Happy Medium, a woman in a mauve turban with a crystal ball. She will show them their father on Camazotz, their mother at home, the Black Thing, and one or two secrets of the universe. She will show because the Mmes. W’s cannot tell.

This is something I and my former partner, my daughter’s mother, have been doing for the last year and a half. We separated at the end of 2018, and since then we have been, as mindfully as possible, trying to show our daughter how she will continue to love and be loved. We were fortunate to stay in the same city for the first months after the break, and this past year we managed to live only two hours apart, her mother in Portland, myself in Eugene. With daily check-ins on FaceTime and routine stays at both houses, we have shown her, I think, that our separation does not mean our disappearance.

This fall we will not be so lucky. I’ve taken a job in North Carolina, and her mother has accepted a position in California. It’s a circumstance we’ve been expecting, one we’ve been planning for. But now that the future is set, now that the geography of our separation has crystallized, the coming relocation looms like the shadow Meg describes in the novel, “dark and dreadful.” The next year will be difficult. When she is with one of us, it might feel as though the other lives on a different planet. I will be sometimes the sun, sometimes the satellite.

We have shown her, on Google Maps, where everyone is going. We have looked for houses together on Zillow. We have made lists of all the fun things to do in California, all the exciting places to visit in North Carolina. But I know the shadow is not just a shadow—it is a Black Thing, which is to say, it requires its own language. I know this because last August, when we all first arrived in Oregon, my former partner and I could feel our daughter’s sadness. Then she showed us an anger she could not explain, an anger she had no words for because we’d not given her any. So, at last, we used the word: divorce.

It’s hard, even now, to grasp how scared I was that the term for our personal calamity would itself prove calamitous. But as in L’Engle’s novel, the children are strongest when they use the language they’ve been given. When first shown the Darkness, Meg wonders to herself, “Was this meant to comfort them?” Later, though, when she and her father confront IT, he implores her to yell aloud the periodic table of elements. He screams, “Say it!”, and her words keep the shadow at bay. As our daughter said, over and over again, divorce, a kind of calm followed. The Black Thing had an edge, a boundary, a border one could trace.

This private disorder happens in the midst of a global one, and I’m certain that many people, for good reasons, would love to borrow from the futuristic science of A Wrinkle in Time. I imagine they would happily tesser—bend the universe—in order to find themselves suddenly beyond the lockdowns, the virus, all the uncertainty. But I am in a strange place, numbed slightly to the chaos, my heart already concussed. I have already been, over the past year and a half, alone in a way I have not been for ten years. I have already been speaking to my child of how her world is changing, how it will continue to change. I have already struggled to put into words a thing that feels much larger than my own narrow experience.

My daughter and I have three chapters left in A Wrinkle in Time. I didn’t read the quintet when I was young, so I don’t know how it ends. The last line we read together was terrifying: “She was lost in an agony of pain that finally dissolved into the darkness of complete unconsciousness.” But there are fifty pages still, and as I write this, she is with her mother, up in Portland for the week. I have a break in our time together. I can, if I want to, read ahead. I won’t, though. I will wait, and I will sound out the words alongside my daughter. Together, we will find out what happens.

Derek Palacio is the author of the novella How to Shake the Other Man and the novel The Mortifications.

July 7

In 1971, the poet Bernadette Mayer spent the entire month of July attempting to capture the movement of her attention and the formation of her memories. Over the course of those thirty-one days, she wrote two hundred pages and shot more than a thousand 35mm slides. The resulting project, Memory, is oceanic. Each of Mayer’s daily journal entries rolls and eddies as she allows herself to thoroughly investigate the elasticity of language and the contours of her mind. Arrayed in grids, the photographs—of grass, cats, friends, flags, skies, boats, herself, the moon—fix into place the minutiae of her days. Later this month, Siglio Press will publish a new edition of Memory that collects the full sequence of images and text for the first time in book form. Mayer’s diary entry and photographs for July 7 appear below.

Do you have access to a T? Do you have access to a xerox machine? This is a major fate hate weigh your fat. So lost so you’re lost how lost can you be when everywhere you turn it’s morning & a flag’s going up over a map: 2 bean sprouts resting on a snow pea pod & then, it snows, it snows for the first time it snows buckets it snows mainly. It snows rain snow gets rid of a lot of germs, says x of the piemonte ravioli co. we pack our pasta in boxes it’s homemade & speak about the weather: homemade stolen electric typewriters it isnt one yet stolen cassette tape recorder he had schemes. Between recorder & he is: the difference between me & the maharajah. We dont we wont atone for that we leave it as it is so, lost you’re lost how lost can you be when everywhere you go it’s morning & the sun’s coming up over a map: & the map a map to alford massachusetts to a certain place in alford massachusetts within the town lines it goes like this forward: start up the car past golf course along winding road across route 183 past j&k’s house (blue & yellow) up to T in road (chesterwood sign) follow the sign make left the road turns to dirt follow the arrows who? Till the road it’s dirt veers off in two directions always bear right on the dirt road. Veering right watch for oncoming cars on this narrow dirt road you’ll go by a white fence just pass by it when you get to real road, asphalt, that’s route 41, take a left go over a small bridge quickly (it’s green) you go a tenth of a mile & make the first right up & around the black surface of winding cobb hill road, if you’re careful you see the sign. Winding & uphill until you read a complex of buildings that looks like a textbook farm, if you make the right right in a second you’ll be passing a big red barn on the left, watch for the cows & people on the road & incidentally here’s where the road — if you walk on it you’ll see — looks like it was hit, the surface of the road, by a series of small meteors burning holes making holes making burns in the surface of the black hard asphalt brown burns. Go right on till you see a small sign that’s faded over it says alford five miles & something else, this is your first left on the road — if you’re on a motorcycle at night you’ll notice here that the temperature of the air is considerably warmer than before, we are in some kind of valley air pocket but after driving a few miles uphill it seems inexplicable except to the people who live here, here we also pass a dream-like farm nestling in the valley’s expensive soil, after making this left the road suddenly turns to gravel — I think this was probably temporary so dont count on it but the gravel begins as you cross the west stockbridge-alford town line sign. Just after you’ve passed the alford brook club or just before alford brook itself is almost invisible like a light on the shore of the country we’re making for, we’re almost there, go about 1.3 miles on this road & then stop at the house.

Before you make it you’ll pass by blueberry hill & the house of a certain dr. pepper a white house with a red car the doctor has a beard, also some house with a title like swann’s way or windy haven, everyone here is dead serious dont go as far as the turn in the road where you pass a white fence on the right & a winding uphill road to a black & white house & dont go as far as the next valley where the view is for miles & definitely dont go as far as the strange house with a gazebo a wooden horse & carriage & an empty reservoir on the left, two bachelors live in this house. If you’ve made the right house it’s the one right on the road on the left opposite a yellow one & it’s brown with blue doors with a chimney of stone in the front, it’s a funny looking house, stop there, across the street is a russian prince who loves cats & a princess who is vincent price’s sister who curls her hair, stop across from them, they have a station wagon & two 35mm movie cameras, her name is cam so lost you’re lost how lost can you be when everywhere you turn it’s morning and a flag’s going up over a map: pack car get gas get j’s car & tv equipment go to beverly’s get key, she had none we had to break a window to get in, buy an alarm clock pick up the bed go to the barn see about electricity, go to j’s remember eileen & call tom, we made a map which is sun which is shade & how many are accidents we almost hit a car there one day. And so, we pass jacques & kathleen’s house on our way home again 3 white chairs in front reflect light & kathleen left for the city last night dont forget to call the massachusetts electric company, we did. Splinter splinter of the headboard of the bed splinter of an unshaved dangerous support board for the body of the bed, the bed set up in the middle of the room, splinter’s clear, we took the splinter out a foregone conclusion pasted it up with hydrogen peroxide bought bandaids & fell through, ed took a picture you are an actor but dont want to act so instead you talk about marriage by a sweet pond near a sound studio sound & sweet the whole story of the orange pen stolen from the basement. Someone smokes quotes if he someone’s son were a few years older he could dip in the cool hollywood pool they provide at an inn, describe gold describe golf get married sink in the deep with no regrets no one looking after him just drown, he could get married he could think, no one would taunt him about it & if marriage had an open end he could think it could become misty in the light could drink light itself, add up the mileage conveniently open find out what’s inside he could work live without light, he could candle & flashlight it, he could ride in a convertible without seeing he could create a shortcut write about prayer he could set up lights take them down take pictures he could photograph lights he could be forced to, he could let the light in he could begin a day without a proper bed he could freeze sentences in air, he could eat out, he could drift in & out of a blue room he never woke up in he could imagine a yellow one small, he could notice windows, how you see them, two eyes, ed read the new york times he will never eat a big mac again.

It’s as simple as that I am looking for 2 u-haul mirrors not fish. And again: legs crossed, who is hungry as I am who is sweet j laughs at cars point risk point. The cars last word, in them, who hears it fall direct a line to women fall by the side of the roadway, men? Gouge out eyes? No, but fall by the side on one-way roadways of those not like to like. It’s too loud a thud, swan swan silvertones comes down & down just a little bit a little bit too hard hard pat pat a person subtle system, laugh & swell life clear smooth & double perf of film, opaque a system system design your life not mine. It’s clear: read genet to describe kathleen run hide give her something run away stay away hide you’re in here I’m out again, hide resist fall get up run away ed smiled in the u-haul store we buy a flashlight. Ed the detective ed the cook & messy erasure, ed or mr. & mrs. ed & mr. & mrs. north, what of this take? 72 times in the year & still the same tone, never come true dreams that ring in your ear that way all around the ear 360 degrees & elaine sets designs rejects set designs one right after the other then, concentrate, set design, freedom a moment a memory away, then one step more, get rid of a memory & laughs “come clean”: “you’re in the wrong doorway!” You’re in the wrong home you’re sitting in the wrong sun writing in the wrong car smelling the wrong burning hair all is wrong over is wrong someone said & someone said “functional & ornamental” & the pictures are like all pictures are lie like sleepers like a railroad crossing sign is a skull & laughs comes clean at the edges & sign the sea is bluer signed a book & sign in time, put dick paul in city hall, why two men & are they both sitting down? Do you give up? The ghost as well? Oceans right & left, since we’re always aware of it, what should we do a-men, men are able so just act sweet & go on: you wake up you walk out a man is raising a flag merican flag in house next door & nixon’s the man do you like trees? Is susan strassberg a famous merican actress, woke up, walked out, owner waters the lawn n’ mows grey house of merican flag & mellow one with basketball hoop, there’s a merican mosquito under my shirt does it hurt? No we moved.

Between the thumb & forefinger of my right hand, between those a splinter zooms in quick & the taste waste of a room — I’m a schoolboy in watercolors, look around, its mountains in merica zoom, what the fuck’s the moon we’re in an insulated room we take our time runnin round we zoom no moon, we make, monster, the greatest milk of all time, like this: one blue head with a black wig on sitting in a window surrounded by skirts, & mercy like they say another merican flag by god a whole display of em, pink, o mesh & gauze cause you to faint for mercy wow up on a mt. top maybe if you’re lucky you prick think back: you saw flowers underneath woman’s head eyes closed reflected in the window you saw flags in, same one, shit man it was a beauty shop if I ever saw one, somebody grabs a 7:30 flight to toronto man & s is doing juliet on the square, what a gas explosion that was red engines galore & ten gallon hats to boot the end. Not by a long shot. Cabs. It was the circle beauty salon with a capital C & wait till you personally see the capitol’s mind’s eye blower encased in space emergency glass — that’s silver & gold case you didnt know, you fucker. The mother’s house was bigger than the house of the fatter father. That’s how it goes, both mother & father resemble police cars & in the dark: a picture of a stone a picture of a mother superimposed on a father, a picture, a prize-winning picture, of bird on tree. We never saw that one, we never looked at it, we didnt come from there, we grew up in the city, we grew up in the shadow of the housatonic riverboat gambling casino we grew up in a cadillac we saw a dog limping we saw a bear in the woods in merrimac forest we saw a bear limping by the side always by the side, they were constant companions, of a giant dog a strange giant dog back behind the swimming pool we saw this sight, it was glorious in the sense that it fit the exact size it fit exactly it was just the right size to be framed by a single standard size, the official size, basketball hoop of this century nba regulations. And so, we bought a berkshire eagle & a couple of side view mirrors, there was nothing playing at the drive-ins, something black, we got home after dark, no juice. No sparks. No gas. No flames. No water at least we had ground. The moon was full the brightest clouds you ever saw moved across in front of it the brightest night clouds move fast, it’s scenery. You think you plan you save this up, your calm drink, black jack daniel’s sour mash whiskey from tennessee where ground is green it’s orange, no colors in the dark fireflies we lit the house with candles on the stone slab center stone is safe turn on the fire brigades, light up pricks & ready for the team, we put out fires after they begin, they burn for a while you call clouds passing all the while passing quickly in front of the moon, when are they coming when will they be ready.

Get dressed in the middle of the night, on call, it’s the volunteer fire dept of new york city we’d like to see you in action we’ll call when we’re ready meanwhile we’re watching these certain clouds go by by the moon & I’ll hold a candle to your face if you’ll hold one to mine, the fireflies in no mood exposure to the moon will . . . & ed with a candle on ed face the moon behind we’re ready for action, the motion’s in the sky candle ed makes a path through the room dont trip to the moon or I’ll call in the brigade again & they’ll sing hearty songs drink all the whiskey we have in the house & sing no juice how? In the sky ed walked through the room with a candle in his hand how did the fire start sir, in the bed in the sink in the dead of night, it must’ve been the bed in the middle of the room caught fire in the, no, it was the matches left out in the moon. Light matches & perhaps you can see fireflies ed with a candle on his face, the big moon behind not long enough I’m lit candles in my hair my hair in braids but not tied like randa wears it the braids coming loose at the bottom so much action in the sky ed walked through the room with a candle in his hand I watched through the big window he passed behind the headboard of the bed, drank & smoked, left matches & a candle outside, the candle got a feather stuck to it no mosquitoes we bought sugar & evaporated milk, had coffee in real cups with water from the pipes left there, boil it, new tv, notes candles nectarines & many matches ed got a new kind of match today a permanent match eternal one. Come out now men in your rubber suits for the permanent match is a dangerous one dangerous to the touch & a flashlight at the auto store, I demanded it, a clear light not from fire soon blow up explode in a flash of . . . drink more, we make a match fire light a cigarette & store or set fire to the end of one & draw in the smoke into our hearts & lungs, the firemen are back to help put out a row of candles sleeping, fifty or a hundred of them shaped like the body of a man or a crown, we light them all drink a cup of hot coffee & sleep in flames. Leaping around the notes we make about moon, sleep, middle of room, wake up clear & alter. It’s annabel lee or something: sharp knives cut fingers & hands, splinters get in they burn we swim at least we like to swim

Bernadette Mayer is the author of more than thirty books, including the acclaimed Midwinter Day (1982), The Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters (1994), and Works and Days (2016), which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Associated with the New York School as well as the Language poets, Mayer has also been an influential teacher and editor. In the art world, she is best known for her collaboration with Vito Acconci as editors of the influential mimeographed magazine 0 TO 9.

All images and text from Memory , by Bernadette Mayer, Siglio, 2020. Images courtesy of the Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego.

Feminize Your Canon: Fanny Fern

Our column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.

In 1854, one of America’s most popular newspaper columnists, the pseudonymous Fanny Fern, published Ruth Hall: A Domestic Tale of The Present Time, an autobiographical novel so thinly veiled as to be downright scandalous. In a preface, Fern announced that her book was “entirely at variance with all set rules for novel-writing,” eschewing an intricate plot, elaborate descriptions, and cliff-hanging suspense. Instead, the author likened herself to a casual visitor, dropping by unannounced with gossip to share—and, clearly, some scores to settle. Fanny Fern’s identity had been an increasingly open secret, but now the life of the woman born Sara Payson Willis in Portland, Maine, in 1811, was revealed, yoked to that of the novel’s long-suffering, noble heroine. Yoked, too, and thoroughly skewered, were Willis’s family: her monstrous mother-in-law, her mean and hypocritical father, and especially her brother, Nathaniel Parker Willis. A famous man of letters and newspaper proprietor, “N.P.” was flayed in the pages of the novel via the character of Ruth’s brother Hyacinth Ellet, a fop, fortune-hunter, and fraud.

Unlike many sentimental fictions of the time, Fern’s book did not claim to impart any obvious moral lesson. Instead, the author wanted to “fan into flame … the faded embers of hope” among readers who felt abandoned and abused—who were, like her heroine, victims of fate rather than of their own failings. Ruth starts the story a lucky young woman: intelligent, beautiful, and about to marry a man she loves. We meet her on the eve of her wedding, reflecting back on her unhappy childhood as an awkward, solitary child, who craved true love but was surrounded by people who cared only for flattery. She appears to have triumphed over her past, however, in a marriage that is blissfully happy. It can’t even be marred by the obsessive malice of her husband’s parents, who are determined to see the worst in Ruth. Their power is limited—until Ruth is widowed. Then she is vulnerable to the neglect and cruelty of her in-laws and her own family. She struggles to keep herself and her two young daughters housed and fed, trying all the limited employment options open to a woman, while her family members duck and twist to avoid providing for them. At her lowest ebb, Ruth decides to become a freelance journalist.

In the second half of the book, Ruth and her creator slowly claw back pride and power, as the sentimental tale transforms itself into a fantasy of vengeance for every downtrodden and underestimated Victorian woman. “I tell you that placid Ruth is a smouldering volcano,” her mother-in-law observes, reluctantly admitting that she’s met her match. One hard-won draft at a time, Ruth ascends to fame and fortune, vanquishes her familial and professional enemies, reclaims the daughter her in-laws tricked her into giving up, and leaves her bleak city lodgings for a country home, paid for with her own pen.

Fanny Fern’s life story tracks closely to Ruth’s, with a few important differences. Where Ruth has only her obnoxious brother Hyacinth, Fern was one of nine children, and had already had some literary success, publishing articles in her father’s newspaper, before she married. Like Ruth’s, her first marriage was a happy one; at twenty-six, she married a Boston banker, Charles Eldredge, and had three daughters. It was a traditional Victorian domestic arrangement, in which she did not need to earn her own living. But after seven happy years, a run of tragedies battered Fern with twice the cruelty she inflicted on her fictional counterpart. Between 1844 and 1846, she lost not only her husband and eldest daughter but also her mother and sister to illness.

Widowhood left Sara Eldredge poor, and she first looked for support via a route Ruth never considers: a second marriage. Her husband, Samuel P. Farrington, was brutal in his jealousy, and after two years his wife made the rare and difficult decision to leave him. Risking poverty and scandal, she took her daughters and moved into a Boston hotel. After two more years, during which he smeared her reputation and turned her family against her, Farrington divorced her, leaving her bereft of both moral and financial support.