The Paris Review's Blog, page 157

July 14, 2020

Redux: Thunder, They Told Her

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Kazuo Ishiguro.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about summer storms, rain, thunder, lightning, and everything watery. Read on for Kazuo Ishiguro’s Art of Fiction interview, Larry Woiwode’s short story “Summer Storms,” and Denise Levertov’s poem “Sound of the Axe.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or, better yet, subscribe to our special summer offer with The New York Review of Books for only $99. And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Art of Fiction No. 196

Issue no. 184 (Spring 2008)

INTERVIEWER

Why did your family move to England?

ISHIGURO

Initially it was only going to be a short trip. My father was an oceanographer, and the head of the British National Institute of Oceanography invited him over to pursue an invention of his, to do with storm-surge movements. I never quite discovered what it was. The National Institute of Oceanography was set up during the cold war, and there was an air of secrecy about it. My father went to this place in the middle of the woods. I only went to visit it once.

Summer Storms

By Larry Woiwode

Issue no. 114 (Spring 1990)

What is so pernicious about summer storms is the resistance in our nature to admit them. We acknowledge the possibility of storms in the spring, yes, when rain on the roof can assume the sound of a waterfall; or in the winter, with a howling wind accompanying drifting snow; or even in the fall, when heavy bodied rain tears off the last of the leaves and pastes them over spearing stubble. But summer is the season we’re to be let off, to be free of this, as we expect, after the ingrained conditioning of years in school, to be freed from all our onerous chores. So summer storms set us outside our expectations, and often isolate us physically, since we don’t take the precautions we do during other seasons; we expect to bask in stillness, taking summer off as recklessly as—well, that storm on its way.

Sound of the Axe

By Denise Levertov

Issue no. 79 (Spring 1981)

Once a woman went into the woods.

The birds were silent. Why? she said.

Thunder, they told her,

thunder is coming.

She walked on, and the trees were dark

and rustled their leaves. Why? she said.

The great storm, they told her,

the great storm is coming …

(And if you’d like, you can listen to this poem be read aloud on Season One of The Paris Review Podcast.)

To read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. And for a limited time, you can subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for just $99.

What’s the Use of Being a Boy: An Interview with Douglas A. Martin

Though a work of fiction, Douglas A. Martin’s recent novella Wolf is written in response to true events: in the early 2000s, two boys, ages twelve and thirteen, were persuaded by a child predator to kill their father. Wolf shifts between various timelines as it imagines the lives of the boys preceding the act—the mental abuse by the father, the manipulation and sexual abuse by the predator—the moment of violence itself, and the courtroom proceedings. In real life and in this novella, the boys were tried as adults and ultimately sentenced to, respectively, seven and eight years in prison.

It’s difficult to write about true events, especially those that receive extensive press coverage, but Martin explicitly writes against the callous sensationalism of the news cycle. He returns the story to the boys themselves. With a narration in the close third person, Martin creates a composite, in all its contradictions. The boys are seeking freedom from their father. They genuinely believe they’ve found an answer in the abusive family friend. Martin allows this belief—this optimism, curiosity, sensitivity, earnestness—to live on the page alongside violation and claustrophobia.

What makes Wolf unique is its refusal to disentangle all these emotions for the reader. In one particularly wrenching scene, the younger boy is writing notes about the nature of love—it seems, perhaps, to be a love note addressed to or about the family friend who has been abusing him: “He writes it on pieces of paper, like it was going to happen the way he wants it to. He knows what love looks like. This was how at first it was going to feel, he has to know like the friend said.” And despite all I know about the context, it is difficult to refute this certainty, he knows what love looks like. The voice is so immersive that I am alongside the boy and, if only for a moment, conflate love and abuse. Even after I shake myself into my own body, I have to ask, How well do I understand the difference? I’m realizing how much I usually depend on instruction to understand and name suffering. Wolf asks us to do this work on our own.

In one of the courtroom scenes, Martin shifts to the perspective of the jurors, who think to themselves: “Best not to get too close to them. Best not to imagine being like one of them, having felt what either must have at one time or another.” When I wrote to Martin, I wanted to ask how to resist this tendency: Best not to get too close. I wanted to know how writing—despite how regularly language is used to lie and mislead—could ever be enough.

This interview was conducted over email in May.

INTERVIEWER

How did you first learn about the crime that inspired Wolf? When did you realize you had questions that needed to be explored in writing?

MARTIN

It was about a year after the actual event, once the story had gone national and the trial was beginning. One day it was a front-page piece, and that was the first I saw of it, almost twenty years ago now. I am not someone who normally reads the paper, but I wanted to know more than just what was behind the picture of two boys and a much larger man in court. My reaction to how my care was being solicited was part of what led to me writing, but also, any time the boys were quoted, it felt so out of place. When I tried to read about the story, the reporting kept bothering me. It continued to play out in the paper for a while, along with new headlines like “bizarre twist,” and stories taking angles on how it was all part a growing trend of children who might be tried as adults given the severity of their violent acts. It got to the point where I felt if I read anything more, I should write it more as I felt it.

INTERVIEWER

The syntax in Wolf is unusual, but the style becomes familiar—almost hypnotic—over time. There’s this sense of simultaneous overwriting and withdrawing, like an overwhelmed child speaking quickly, slightly out of order, dropping words. At one point the younger boy thinks to himself, “He had to know if he wasn’t confident with what he felt it could be taken away from him, time then to pull away, learning to go down deeper into the self, go like breathing disappearing quiet thoughts apart inside where there no one is to see.” How did you find that voice?

MARTIN

Your characterization of the voice puts it together beautifully for me. The sentences have heartbeats but also breathing patterns, and how these two impact each other would be part of it. I think of the voice as in the head, but it is a forced interiority as a retreat, navigated with no small amount of effort. Like you could drown inside your own head, while you were pushed this way or that. These are directives that identity is shaped around. That voice in the head is made up of all these voices that surround and enter whether you like it or not, coming together, gaining weight to try to guide you. I picked it up by thinking how consciousness more often than not is through other forces of nature than water flowing placidly.

For the longest time I thought it was a matter of which of the boys the story would be given to, to center it, but then I grasped it was more a matter of the way thoughts will pool unspoken in a room when everyone there is afraid of how they might be judged or seen.

INTERVIEWER

I’m curious about the absence of names. Since Wolf is based on a true story, there were names you might’ve borrowed. What motivated you to use relational terms—the younger, the older, the friend, the father—instead?

MARTIN

I think it underlines how I want to look at some supposed roles within these positions.

Before I resolved it, I did have proper names, which with the boys for a stretch would get switched in my mind and the page, the character of one seeming closer somehow to someone I knew who shared his name. Then I thought there might be something to that, so I experimented with intentionally reversing them as part of the fiction, but it proved just a calculation, a gimmick in a way. What I settled for I hope is toward a greater truth. Like when I think of myself in my life moments, that would not be as my given name. I do not experience myself inside that way.

At one point I thought of going as far as the book being named after the whole family—King—because there might be allegorical resonance as well, but it was too grand, too major, really. It would have been irony just for the sake of it.

INTERVIEWER

The word boy appears everywhere in the story, usually to refer to the two brothers, but the narrative also slips into a more general voice, where “a boy” can be any boy. How did your understanding of what it means to be a boy shift in the writing of this story? What does it mean to be a boy in a story/world in which men commit such extreme acts of violence?

MARTIN

That is a guiding question for me. I have long loved Gertrude Stein’s formulation, “What’s the use of being a little boy if you are going to grow up to be a man?” When I came across it, this spoke to me because it was during the first years I had begun doing a couple of things. One was to consider maybe I could be a boy—I had never felt like one growing up, though I was told I was one. But also, I was engaged in understanding how, in some of my earlier formative relationships, with these mentors I would have because of their artistry, there were aspects of me that were surely just that for them, boy. It made my loneliness make sense.

INTERVIEWER

I reread Wolf as I was working on my questions, and it was startling to reencounter the text. I knew too much the second time around and the proximity and details of the abuse became even more intense. I started thinking about your proximity as a writer, and the rereading that must have been necessary to editing. What was it like to reread your writing over the course of the project?

MARTIN

It is there, right before you, and you are not seeing it. Really looking at it, I was frayed. Still that must have been nothing like living it as a reality without any relief, and I needed to feel like I couldn’t go to bed after rereading it. Earlier failed attempts at the manuscript were a product exactly of trying not to reread. There were drafts where I played around with putting it all out there in some grab-bag way or more conceptually organized chapters. But really what I needed to do was make my peace with why I had been drawn to take it up, to live with it in this form, strained to its breaking point.

The longer I went, though, many things came up that would assure my commitment. Over the years these were as various as walking through the documentation of a Tehching Hsieh performance, Cage Piece, and remembering about a step-cousin of mine whose hands seemed to never stop shaking, how he and I were both strung, how we both became drawn to dance as one escape from our fraught adolescence.

INTERVIEWER

At various points you describe the boys in the courtroom. I found myself wondering how much of the imagery was speculated and how much was written with reference to real footage and documents. I felt tempted to search for the news articles, and yet I also wanted to allow myself to experience the story without visual references—I caved about three-quarters of the way through. Could you speak about beginning with and transforming images into prose—particularly images from a crime story? I’m thinking about this especially in the context of our media culture, which often sensationalizes traumatic photographs or footage.

MARTIN

Yes, that was the last thing I wanted to do. Even less to invite comparisons like those credit rolls at the end of a film where the actor is situated beside the real-life personage. But there was a tension. I didn’t want to invent, but I also did not want to deny. I wanted a way for those images that existed in circulation to find some dimension beyond flat shock and standard procedures. To see the brokenness of the boy’s handwriting moved me as much as the crime scene photographs, and I wanted to express this. It struck me as incredibly indecent to put the pages of his notebook up on some newsite.com and alongside that also audio files that could be clicked to hear voices during testimony that I listened to sometimes feeling part of the whole violation.

Just recently, before the world took its pause from casual traveling, I was in Chicago to read and also saw a Warhol retrospective thanks to the poet who had arranged to bring me out. I was remembering then how I had studied at points the Death and Disaster series, the electric chairs and car crashes, also his most wanted men, and I had felt something in line with that. In an even more sustained way, I focused some of what I was doing through reading about Gerhard Richter’s reframed presentations of media subjects. I was striving for some similar endeavor in words, like what might supplement a copy of a copy, what can’t but form otherwise than through this trace of an echo. A monograph of his portraits stayed on my desk for a long time.

When I was in college, it was the audio of the opening moment when that rock lands in Heavenly Creatures, the scream that runs at the audience. But before I was a teenager even, even more a child, the girl in Night of the Living Dead with the spade in the cellar was the most unsettling to me, because you could hear it every time you planted anything, if you tried. Something still defying and going beyond the eyes.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a scene in which the younger boy is writing notes to himself about the nature of love. “He knows what love looks like.” Out of context, the scene could be beautiful—the boy’s writing is thoughtful, tender. But readers know that the “love” the boy thinks he knows is the manipulation of the predator. The certainty in he knows what love looks like suddenly seems terrible. What do we do in a world in which such extreme violation of a person and their language—such violation of the word love—is possible? How do you write into that question?

MARTIN

The hardest question I have ever been asked so far, and I do not want to hedge here. I begin wondering what the word is supplementing. I probably do not know much what a love looks like that has not been predicated on imbalances. It can also be the question of pedagogy. It is a question a lot of writers who have formed me have worked upon, and I hold onto those who have been my guides. My teacher Eve Sedgwick said one of the cruelest moves you could make with another person’s mind was to take away their sense of self-definition. I have done something I am sure with her words in crude paraphrase. I remember what I do because of something I need. How I spent many years with a man who would regularly announce he had never been in love and did not believe in it, but still that did not end it for me.

Spencer Quong is a writer from the Yukon Territory, Canada.

July 13, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 17

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“Sheltering in place all these months has made me realize how much I truly enjoy readings—and how much I miss them. Writing is, of course, a solitary practice, and writers—and readers, for that matter—are the types of people who like spending lots of time alone. But readings and discussion panels are among the few forums in which a whole bunch of literary people get together to partake of the written word, to feel a room humming with collective concentration—and to hang out afterward. Social media just ain’t the same. The Paris Review has always held celebrations and readings to joyfully gather our community in a space shaped by literature. For now, that space must be virtual, but the charge and the sense of community are no less real. In that spirit, and until we can get back to gathering before a podium, this installment of The Art of Distance is dedicated to virtual literary events, two of which the Review is participating in next week, with more to come (including Readings from the Summer Issue on July 22, featuring contributors to no. 233). So enjoy these unlocked interviews and stories with contributors whose events you can ‘attend’ in a few days.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Kelli Jo Ford and Benjamin Nugent. Photo of Ford: Val Ford Hancock. Photo of Nugent: Jason Fulford.

This week, the Review is sponsoring or cosponsoring two free events with recent contributors. On Tuesday, July 14, at 7 P.M., the fiction writer Benjamin Nugent will talk on the Review’s Instagram Live feed with the New Yorker staff writer Naomi Fry about the work and influence of Leonard Michaels. And on Wednesday, July 15, at 7:30 P.M., TPR editor Emily Nemens will talk with Kelli Jo Ford as part of Greenlight Bookstore’s Zoom series (RSVP required). Each author’s work from the TPR archive has been unlocked this week to help you get prepped and psyched for the events.

Kelli Jo Ford’s “Hybrid Vigor” (issue no. 227, Winter 2018) is the story of a mule with the bad, if motherly, habit of stealing calves. The story, for which Ford won the 2019 Plimpton Prize, is part of her debut novel, Crooked Hallelujah, a multigenerational saga about four Cherokee women, which she and Emily will discuss on Wednesday.

Benjamin Nugent, winner of the Review’s 2019 Terry Southern Prize, has been a frequent contributor to the magazine since “God” appeared in issue no. 206, Fall 2013 (and was performed by Jesse Eisenberg in Episode 9 of The Paris Review Podcast). It’s sort of a tale about a poet, or a poem, and offers a peek into the college milieu of his recently released story collection, Fraternity, as do “The Treasurer” (issue no. 217, Summer 2016) and “Safe Spaces” (issue no. 225, Summer 2018). Obviously, this is an uncertain time for thinking about the collective return to campus life; Nugent offers a socially distant way to go back to school and ponder some of the complications of college.

Most recently, in issue no. 231, Winter 2019, Nugent spoke with George Saunders for his Writers at Work interview. Nugent develops an easy rapport with Saunders, whom he describes as “chatty, kind, quick to shoot down any glib analysis of his work, and free with an anecdote, often casting himself as a blunderer whose illusions land him in hot water.” It’s a companionable and insight-filled conversation between two people who are obviously enjoying each other’s company. Nugent’s passion for Saunders’s work is plainly evident in “How to Imitate George Saunders,” an essay that he wrote for the Daily shortly after the interview was published.

On Tuesday, Nugent will discuss the work of Leonard Michaels. If you click over to Michaels’s author page, you’ll find everything there—an interview and three stories—unlocked as well.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

The Archive

One quiet spring morning, as a plague engulfs America, I awake, brew coffee, and shuffle to my computer. Outside my windows, a cordillera of snow-thatched roofs. I feel rooted, glooming in grief and rage. The need to stay in place. In the place of our wreckage. In other homes, I imagine children in nightshirts, and daddy flipping pancakes, and some things still good. Meanwhile, the world continues to break in the ways that it has always been broken.

On my computer, a host of small heartbreaks. Records, evidence, stories of child death in foster care. November 2017, I sat in on the murder trial of the stepfather of a young boy, Gabriel Fernandez. Gabriel Fernandez was tortured and beaten to death. We, the journalists, and the family members and the witnesses tuned in daily. Sitting in that small courtroom, I felt strongly that this was about more than one murder.

It was about the many failures of the Department of Children and Family Services, and there were many, but also about the slow, cold violence that permeates these kinds of cases. I had become obsessively curious—not about just how one family could do this, but how a nation with wealth, how any system, could leave so many children tortured and dead. Over the last five years, I’ve reviewed all the case files of murdered children with a pending Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) investigation. I’d found shelter here, in these redacted files. The dark boxes.

What I know about these children has been culled from police reports, and hospital records, and social worker investigations. The documents all come to me redacted. I spend half my days searching for names, matching names to black boxes. The names of our dead children: they give me pause, they give me agency, an agency I’m not ever certain I deserve. I create a website. I build an archive.

The word archive is derived from the Greek arkhon, “ruler, commander, chief, captain,” which is the noun use of the present participle of arkhein, “be the first.” Thence “to begin, begin from or with, make preparation for,” also “to rule, lead the way, govern, rule over, be leader of.” In these dark times I find the archive as the place to begin. A place to unearth truths.

*

In Muriel Rukeyser’s 1939 collection of documentary poems of witness, U.S.1, she writes, “Local images have one kind of reality. U.S.1 will, I hope have that kind and another too. Poetry can extend the document.”

This appears to be where my compulsion was born. If I stay long enough with the archive—a catalog of disasters, racism, and classism, and worker exploitation, and gentrification, and land grab, and cuts to social safety nets, and cuts to access to education, and no medical care, and no childcare, and no safe affordable housing, and mass incarceration—I will stay rooted. If I shine a light here in this dark theater, I, too, can extend the document.

Muriel Rukeyser is no stranger to the document. The FBI has comprised their own 118-page redacted chronicle of her activities. I, too, have a thick file—one that archives my adolescence as a ward of the court in L.A. County’s foster care.

Rukeyser’s poem Book of The Dead recounts the events of the Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster through fragments of victims’ congressional testimony, lyric verse, and flashes of a trip south. Hawks Nest Tunnel was part of a hydroelectric project, a tunnel made near Gauley Bridge, West Virginia. The workers suffered from silicosis, a lung disease brought on by breathing in silica. The conditions were so dense and dusty, the drinking water reportedly turned white as milk. In the 2018 introduction, Catherine Venable Moore writes, “I imagined the ghost lungs fluttering through the forest at night like sets of wings, surrounded by halations of shimmering silica dust.”

The majority of the workers were Black. The death toll has never been confirmed but is estimated at between 476 and 1,000 people, which would make it the worst industrial disaster in U.S. history. After two trials, a congressional labor subcommittee hearing, and eighty-six years of silence, neither Union Carbide nor its contractor—Rinehart & Dennis Company—has ever admitted wrongdoing for the Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster. In 1933 the company issued settlements to only a fraction of the affected workers, in amounts ranging from $30 to $1,600. Black workers received substantially less than their white counterparts.

*

In reading this, I think of Ruby Duncan, a woman I heard on Krissy Clark of Marketplace’s podcast, The Uncertain Hour. Ruby Duncan is a Black woman from Las Vegas. Thirty years after the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster, Ruby was a single mother working in the kitchens at the Sahara Casino, a ringing, shucking, slinging, dinging racket with low ceilings plush with red and royal purple accents. One day, Ruby slipped on some cooking oil. As a result, she suffered back injuries and required knee replacement surgery. With no income or disability payments, she turned to welfare.

On the first of every month, mothers on welfare came to recognize one another in the markets as they filled their grocery carts. Ruby talked with the other mothers. It wasn’t long before she discovered that white women were receiving more in welfare payments than Black women. According to The Uncertain Hour, this was not unique or a fluke. For many decades, dating back to welfare’s inception in the thirties, discrimination was written into guidelines in various offices across the country. In one Los Angeles office, employee Nancy Humphries said that it was right there in the forms she filled out when signing up families for welfare: a white column and a black column. And until the end of the sixties, states didn’t just give Black families fewer benefits, but they made it more difficult for them to enroll.

Employees were told to ask invasive questions, in order to discourage Black families from signing up, such as, “How often do you have sex?” There was also the good-housekeeping test, during which a caseworker would don a white glove and run their finger along a windowsill to check for dust. To ensure there was no man in the house, welfare officials conducted midnight raids, pounding on the door to look for evidence that would disqualify a single mother from her benefits: the man himself, or a man’s belt, or a razor, or a large shoe.

*

One afternoon in 2017, I arrived at the William H. Hannon Library’s special collections in Playa Vista, California. It’s two miles from the beach and less than ten miles from where my high school was located. I climbed the escalators. I was on assignment to write about the twenty-fifth anniversary of the LA uprising. Most of the Center for Study of Los Angeles’s collection was shared with me. I’d arrived again at the archive, which to me, had come to represent a kind of gaze. A corporate gaze. I donned white gloves, wiped clean the loupe, and returned the gaze. I was particularly interested in Rebuild LA, a corporate nonprofit setup to remedy the damage done to South LA after the LA uprising. Amid photos, and blueprints of job-training projects, grocery stores, and gas stations (none ever realized), I came upon a musical score.

I’d read about Rebuild’s job creation efforts briefly before: the supermarkets that would be built, the minority business enterprises (MBEs), the vans to be distributed. Nothing had prepared me for the extent of their liberal looting—they acquired both private and foundation funding in the millions. The privatization argument advanced by Rebuild LA was that over the last decade, the government had failed to deliver. The inner-city neighborhoods of LA, and its residents, were insolvent, inefficient, lazy, corrupt thieves and public subsidies had run them into the ground. This community needed a group of people with good business sense. Those people with good business sense put the money in their own pockets. As noted in a memo by Chuck Frumerie, an executive who was loaned to RLA in their first eighteen months of operation, the organization solicited over $500 million of public and private investments from companies such as IBM and GM, and all of the oldest and largest private sector companies in the world.

Those funds were spent on board salaries and motivational projects, as if what our communities needed to recover were a snappy slogan or a nice song. For example, on June 6, 1992, one thousand chorus members of South LA churches were bussed into the Hollywood Bowl to perform the new anthem to LA. RLA commissioned the song: David Cassidy’s “Stand and Be Proud.”

This is our chance

Now we gotta take it

We may never get to pass this way again

We gotta be strong

If we’re gonna make it

Now it’s time to dry the tears.

Through the ashes hope appears

And if we reach out for the sky

We might touch the stars.

We have a dream

Now we gotta live it

It’s gonna take some work to make this dream come true

All proceeds from this feel-good motivational ditty went to Rebuild LA. The song brands Rebuild LA as a beam of hope, and poverty as an identity problem and the result of poor life choices, rather than circumstances or a lack of access.

Five years after the song, Rebuild LA folded, leaving our neighborhoods in very similar conditions as it had found them.

*

I was fifteen years old during the LA uprising. I watched as the news directed foot traffic. The news would report looting at Pep Boys, then I’d watch as, outside my window, kids ran over to the Pep Boys, then to the RadioShack. People pushed carts of formula and diapers, a man was pulled from his car and it was set on fire. I sat in my foster parents’ home in West Los Angeles, blocks away from the high school. I looked from my foster parents’ white faces to the brown one of our housekeeper, to my own tan skin, and wondered what I should be doing next. The summer before, I had undergone a prolonged identity crisis. “What is she?” people would say. “So exotic. So modern. But what is she?” They got close to me, invited me into their home, supported me, but continued to protect their hearts from my otherness. Would I leave? Would I be removed? Would their love suffice? What is family without a biological echo? The unknown. That trick switch inside.

In school the next week, we heard about how, over in Watts, the malt liquor from forties of Old English 800 had been poured on the ground outside Imperial Courts Housing Project as the Grape Street Crips from the Jordan Downs Project, the P Jay Watts Crips from Imperial Courts, and the Bounty Hunter Bloods from Nickerson Gardens Housing Projects negotiated and signed a peace accord. The formal peace treaty was modeled after a ceasefire reached between Egypt and Israel. The document called for “the return to permanent peace in Watts California” and “the return of Black businesses, economic development, and advancement of educational programs.” Together they laid out a more detailed economic plan and made their demands of the city. Rebuild LA responded with promises to create jobs, requiring the employers to hire only within the affected areas.

What I saw the summer after was that nothing had changed. By then, the streets were teeming with gangsters, busted businesses, and trafficked girls. Somehow, to ourselves and our own streets, we had become a menace. It was the first time I began to consider that I, too, could become one of them. As I neared my eighteenth birthday, talk of college began to dissipate; instead, it was brochures of independent living programs and talks of signing up for general relief. I took a razor to the underside of my thick curly hair. The hair everyone complimented. I lined my lips with a rusted crimson-colored pencil. This won’t be catalogued in the archive. I perfected a dull, flat look of disinterest. One that said, I’m not pleasing you. Yet there was something deeper than these outward changes, and less defined. Something that frightened me. It was at this time that I’d accepted the idea that I was unlovable. That deep down, that trick switch was not a trick at all but rather a monster. A monster maybe because I had done everything I was told to do, by the church, by my grandmother, by the courts, by the teachers, by the city, by the state, and I was still left standing with few to no options.

*

Tuesday, June 3, 2020: helicopters screamed in the skies above Downtown Los Angeles as thousands took to the streets. This time, we were diverse. We were Black, brown, white, Asian. This time we went where the privilege was: Beverly Hills, Fairfax District, Burbank. We did not burn our own storefronts and neighborhoods that still sat in disrepair from the 1992 uprising.

*

June 4, 2020: family and friends congregated inside a sanctuary at North Central University to pay tribute to George Floyd, who died at age forty-six. Meanwhile, in D.C., the Senate reached an impasse as Senator Paul Rand blocked the anti-lynching bill exactly one hundred years since June 15, 1920, when Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie were dragged from their cells by an angry white mob, then tortured, beaten, and hanged.

*

June 12, 2020: Minnesota voted to pardon Max Mason, one of six Black men who were wrongly accused of raping a woman by the name of Irene Tusken. It was June, 1920, and Tusken’s boyfriend said that six men approached them at the circus and raped her, but there was nothing to support this allegation. A total of thirteen men had been jailed, and three—Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie—were dragged from the jail and lynched by a white mob the night of June 15. Mason was convicted in November, 1920, and paroled in 1925. He died in 1942 in Memphis, Tennessee.

*

In The Red Record, Ida B. Wells writes, “The Negro does not claim that all of the one thousand black men, women, and children, who have been hanged, shot and burned alive during the past ten years, were innocent of the charges made against them. We have associated too long with the white man not to have copied his vices as well as his virtues. But we do insist that the punishment is not the same for both classes of criminals.”

Her call to action stands today, “Can you remain silent and inactive when such things are done in our own community and country? Is your duty to humanity in the United States less binding? What can you do, reader, to prevent lynching, to thwart anarchy, and promote law and order throughout our land?”

Wells writes that the frequent inquiry after her lectures is “What can I do to help the cause?”

“The answer always is ‘Tell the world the facts.’ ”

*

The documents that live in my computer: police records, hospital records, social worker assessments. “Assessment Tools,” the Department of Children and Family Services call them. But like any tool, it can be calibrated to offer the results you are seeking. So, if the department is urging family reunification, the assessment will be more lax; if the department is urging the removal of Black and brown children, the assessment will be more stringent.

Saidiya Hartman addresses this discrepancy in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. Of the archive she says, “Power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known.”

She chose to excavate a story of joy and liberation from behind the redacted documents. “In writing this account of the wayward, I have made use of a vast range of archival materials to represent the everyday experience and restless characters of life in the city.”

These records Hartman engaged with—trial transcripts, slum photographs, prison case files—all represent Black women as a problem.

In her note on methodology, she states, “The wild idea that animates this book is that young black women were radical thinkers who tirelessly imagined their ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.”

Hartman writes that Wayward Lives elaborates, augments, transposes, and breaks open archival documents so they might yield a richer picture of the social upheaval that transformed Black social life in the twentieth century.

If ever I want to catalog the failings of our world, our country, our police, the Man, big business, I can come here to the archive. I can take all my helplessness, and hopelessness, and rage, and shine a light into the dark theater of bureaucracy. I can then do what Wells urges us to do: to tell the facts, publish them, point to them. Be a social arsonist, light minds and hearts on fire. I can also dare to do as Hartman has done, and imagine a different, better world. One where we dance and sleep undisturbed, look at birds, and breathe, always breathe. And then push further. We reach, and shimmer, and shine. I sit at my desk reading The Book of The Dead and imagine sheer lungs floating like butterflies over the mountains. In Rukeyser’s poem, she writes

What three things can never be done?

Forget. Keep silent. Stand alone.

Melissa Chadburn’s work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, Longreads, and dozens other places. Her essay on food insecurity was selected for Best American Food Writing 2019. She is the recipient of the Mildred Fox Hanson Award for Women in Creative Writing. Her debut novel, A Tiny Upward Shove, is forthcoming with Farrar, Straus and Giroux. She is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern California’s creative writing program.

July 10, 2020

Staff Picks: Tricksters, Transmogrifications, and Treacherous Beauty

Marie NDiaye. Photo: © Francesca Mantovani.

No one is condemned to being human in the world of Marie NDiaye. People become birds, skulk home as canine omens, as vapors, or transmogrify into logs. What a relief such transformations can be, since consciousness, for NDiaye, is a fraught and painful thing. Even when writing in the third person, she has an extraordinary ability to trap readers in the heads of her characters, leaving us to rattle around in their skulls, crouch in the dark confines, and peek out to witness their humiliation. In the face of a painful reckoning with the world, the mind often gives way. Perhaps the cruelest element of her work is not that her characters suffer but that they are so often left unable to perceive it. That Time of Year, first published in 1994 and elegantly rendered in English by her veteran translator, Jordan Stump, will appear this September from Two Lines Press. Herman, a Parisian, extends the family holiday past August, the end of tourist season. It is abruptly fall—a deluge begins, and his wife and son have vanished. The inhabitants of the village have no interest in the case. Herman, too, finds himself unwilling to break social codes, to plead for help or for their return. He lingers, coming to note certain details: the web of surveillance (run fast); everyone’s exceedingly blonde hair (run far). Roots peek out beneath the dye and give away the newcomers; Herman learns he is not the first to have lost his family. The only way to find them, he is told, is to stay and become one with the village. “You can’t very well change your skin in two days, can you?” There is no distinction between assimilation and dissolution: to find your family, “you have to lose every last bit of yourself.” Rain, brain, go away; the downpour continues, and Herman’s memory and body seem to dissolve. In this self-annihilation, he finds “a timid sort of pleasure.” There is a strange pleasure, too, in this remarkable tale. It feels true even as it is utterly unreal; it seizes the brain like a very bad dream. —Chris Littlewood

Readers of Halle Butler’s novel The New Me will notice many of the same reactions while reading her debut, Jillian, which was reissued this week by Penguin Books. Those feelings are: secondhand dread, secondhand embarrassment, a cringe every so often at an unsettlingly familiar character flaw or moment of the bodily grotesque. Jillian flips between the lives of two women who work admin at a gastroenterologist’s office. Twenty-something Megan’s bitter depressive spiral careens out of control while she obsesses over the happy women in her life, namely Jillian, her colleague and a single mother, whose rosy disposition at the office is masking a breakdown that would put Megan’s to shame. While The New Me pokes fun at the follies of yuppie striving, Jillian is a little rawer, a little darker, while still laying bare the devastating inner lives of deluded and aimless people. —Lauren Kane

Miles Okazaki. Photo: Dimitri Louis.

The pandemic has made it hard for jazz musicians, like other artists who depend on a steady flow of gigs, to make ends meet. The label Pi Recordings is working to help artists through its This Is Now series, a line of digital-only albums and EPs on Bandcamp from which the label takes no cut of sales and instead lets the artists use or donate the proceeds as they see fit. So far, they’ve released wonderful and sometimes unusual recordings by Steve Lehman (solo sax works recorded in his car); Vijay Iyer (an instrumental version of his hip-hop collaboration with Mike Ladd); Miguel Zenón and Dan Weiss (a drum tribute to Elvin Jones); Liberty Ellman (an excellent trio EP); and last week, Trickster’s Dream, a remarkable “live” album and film by the guitarist Miles Okazaki and his band Trickster. Beyond the music—which is drawn from the band’s most recent studio recording, The Sky Below—what makes this album so remarkable, and the reason why I put live in quotations, is that all four musicians recorded their parts at home, layering them atop tracks sung by Okazaki, which were used to sync the performances and then deleted. Okazaki is a wildly versatile musician, freakishly precise, but also full of emotion. Trickster, an aggressive but not ear-splitting blend of contemporary jazz and rock styles, is his best band, and Trickster’s Dream is an ideal way to sample their music. The album only gets better if you keep its making in mind as you listen. —Craig Morgan Teicher

It’s difficult to describe what kind of book Moyra Davey’s Index Cards, newly out from New Directions, is. Ostensibly, it’s a series of essays that meander through subjects as varied as the writings of Vivian Gornick and Natalia Ginzburg, Davey’s own photography and video work, New York in the early aughts, and Quebecois separatism. There are also excerpts from Davey’s diaries and an essay-script for her film Les Goddesses. The overall effect is one of rifling through someone’s notebooks, figuring out what exactly makes them tick—always a thrilling feeling. As Davey says early on, in a paragraph about the work of Ginzburg and Peter Handke, “I wanted to write this without ever saying ‘I feel’ or ‘I felt,’ with Handke and Natalia Ginzburg as my models.” This goal of precision is a fascinating one, and one that I think Davey achieves. —Rhian Sasseen

Talking about poetry—I never thought this would be something I’d miss in quarantine. I miss discussing poetry over the seminar table at school or while congregated around someone’s desk at The Paris Review’s office in Chelsea. I miss that moment in conversation when a puzzling verse suddenly gives way to meaning. I was delighted, therefore, when the professor and scholar Elisa New introduced me to , the documentary series she produces and hosts on PBS. For each episode, New chooses a single poem to examine, discussing its technical intricacies with a variety of guests, always to arrive at some broader emotional question or truth. I was especially moved by on “You and I Are Disappearing,” by Yusef Komunyakaa, veteran and unofficial poet laureate of the Vietnam War. The poem is composed as a catalogue of similes, resurrecting the memory of seeing a young girl burning alive and bringing to mind Nick Ut’s famous wartime photograph. Komunyakaa reads aloud in a deep baritone, accentuating the organic musicality of the verse:

She burns like foxfire

in a thigh-shaped valley.

A skirt of flames

dances around her at dusk.

…

She burns like a shot glass of vodka.

She burns like a field of poppies

at the edge of a rain forest.

As the composer Elliot Goldenthal observes in conversation with New, this elegy for an unknown girl sounds a lot like the blues. Its rhythms convey something dangerously sensual about war, capturing what Komunyakaa calls, in his own words, a “treacherous beauty.” —Elinor Hitt

Elisa New. Photo: Rose Lincoln/Harvard University.

Walt Disney’s Empty Promise

© VIAVAL / Adobe Stock.

If you’ve ever been to Orlando, friend, you’ve been to International Drive. It is the 14.5-mile strip of hotels, restaurants, hotels, time-shares, souvenir shops, lesser theme parks, laser tag emporiums, curio museums, outlet stores, and hotels that’s “as well-known in Boston, England, as it is in Boston, Mass.,” as the line goes. And this is an important point to make. For so very many of the millions of tourists who come to Orlando, this—Disney, Universal Studios, I-Drive, all of it—stands in for America itself. “No matter where you travel in the world, you run into a startling number of people for whom Orlando is America,” John Jeremiah Sullivan has written. “If you could draw one of those New Yorker cartoon maps in your head, of the way the world sees North America, the turrets of the Magic Kingdom would be a full order of scale bigger than anything else.”

International Drive is not Orlando’s main thoroughfare—that’d be Interstate 4, which runs parallel to I-Drive—but as International Drive comprises five hundred plus businesses selling everything from digital cameras to golf clubs, weeklong stays to Argentinian steaks, it is far and away the most vital artery when it comes to Orlando’s economic health. This despite the fact that until very recently, I-Drive was nothing but sand, pines, and palmettos. What happened was an attorney turned developer named Finley Hamilton, who went looking for ways to profit from Walt Disney’s 1965 announcement that he would build a huge new theme park southwest of downtown. On April Fools’ Day 1968, Hamilton paid $90,000 for ten acres of scrubland. This patch of nothing was accessible only by dirt road—but Hamilton figured that Disney-bound tourists would spot his new Hilton Inn from the interstate, take the nearest exit, and drive north on the paved road he would build.

He bought and flipped more acreage along his road in the months preceding Disney World’s opening. “I came up with International Drive,” he later recalled, “because it sounded big and important.” Within a few years, I-Drive included a dozen hotels, two dozen restaurants, and four gas stations, most of which were clustered at the road’s two major intersections. Then the nation’s first water park, Wet ’n Wild, opened in 1977. Just like that, I-Drive went from a place to sleep and eat to a destination in its own right. Arriving not long after were your Ripley’s Believe It or Not!s, your Skull Kingdoms, and the like.

In short, International Drive has developed into a tacky gauntlet whereby families are stripped of armloads of cash on their way to and from Disney parks. It, like Greater Orlando, is premised upon one thing: Uncle Walt’s sloppy seconds.

I hopped on the International Drive Trolley at its southern terminus, so very excited to be aboard a motor vehicle. This being Florida, where fixed meanings are prohibited by the spirit if not the letter of the law—the Trolley I boarded was not a trolley trolley. It was a bus. A bus done up fancy-like in trolley drag, but a bus nonetheless, with slatted wood benches, interior lights sculpted to resemble gas lamps, and a whole honking gaggle of Europeans. Europeans slung with water-bladder-esque purses on the thinnest of straps; Europeans smoking unfiltered cigarettes; Europeans wearing capris hemmed at inspired lengths. Together we rode from South I-Drive to SeaWorld, where the Continental children ooooed at the expanse of parked cars glinting in the sun. We passed an empty municipal bus, which led me to speculate: I bet this is the most used public transit route in the state.

We gathered more passengers outside an outlet mall. Their wrists were braceleted with the woven cardboard handles of upscale shopping bags; their smiles communicated the bliss of completion. We accelerated past the noodly, Lovecraftian slidescape of Wet ’n Wild. Someone dinged the ding for WonderWorks.

In terms of gross economic power, the tourism industry is in the uppermost tier along with energy, finance, and agriculture. Worldwide, it generates $3 billion in business every single day. If frequent flyer miles were a currency, it’d be one of the most valuable on the planet. Why shouldn’t tourism have its own city the way oil has Abu Dhabi and film has Los Angeles?

Orlando is tourism’s pantomime capital. But that’s not all due to Disney. Contrary to Uncle Walt’s founding myth, roadside attractions and theme parks had been dotting city and state long before his arrival. It’s just that their theme was, well, “Florida.” Sunken Gardens and Jungle Gardens dazzled Depression-weary Americans with imported grugru palms, Madagascar screw pines, and the greatest concentration of orchids in North America. Silver Springs, Cypress Gardens, and Weeki Wachee Springs took a similar tack—“Come marvel at Florida’s splendor!”—while adding canny advertising and gimmicks like alligator wrestling to the mix. These “natural” attractions were equal parts organic phenomena and human cultivation. Their grounds had been processed and “improved,” just like the canned and sprayable foodstuffs then appearing on supermarket shelves.

This was midcentury, when a Florida vacation was seen as a marker of middle-class status. What’s more, a Florida vacation underscored one’s support of and participation in the American way of life. You drove your new car to new national wonders like Marineland, where intrepid scientists had trained bottlenose dolphins to perform tricks, and in exchange for your hard-earned money you got the sense that you were combating global communism.

Around the same time, the superhighways were snaking their way into the peninsula. The interstate program—the most expensive and elaborate public works program of all time, mind—was at once a Keynesian economic driver and a geographic equalizer. The impeccable government roads stretched down the Gulf Coast, along the Atlantic coast, and across the gaps in between, buttressing Florida’s sky-high growth like a trellis around a sprout. Tourists no longer had to rely on railroads, bus schedules, or dicey Southern byways while traveling to the Sunshine State. Now, millions of them could pick up and go whenever the mood struck. They could chauffeur their families to difference within a matter of hours, riding the interstates the way aristocrats had ridden Henry Flagler’s trains a generation prior.

This democratization of travel was precisely what Walt Disney observed on November 22, 1963, when he flew over Orlando in a private plane, assessing the area’s potential for his Disney World project. He looked down and saw Interstate 4 intersecting with Florida’s Turnpike, both roads teeming with fast-moving traffic. Not far away from this hub, he eyed a vast stretch of virgin swamp. “This is it!” Disney exclaimed over the roar of engines.

With such a combination of highways and undeveloped land, Disney could build his dreamed-of tourist mecca—America’s “total destination resort,” as his planners referred to it. He bought up 27,000 acres, anonymously and piecemeal, from Central Florida farmers, ranchers, and rural landholders. For $200 per acre, owners were more than happy to sell to one of the five dummy corporations orchestrating Disney’s clandestine “Project X.” In time, the locals noticed that the ground was shifting beneath their feet. Rumors ran rampant as to who or what was purchasing southwest Orlando. In October 1965, one headline in the Sentinel read: “We Say ‘Mystery’ Industry Is Disney.” A year later, Uncle Walt officially announced his plans for a “bigger and better” version of Disneyland in Florida. The Associated Press crowned him “the most celebrated visitor since Ponce de Leon.”

While the Disney saga unfolded, many of Florida’s established attractions were being bled dry by the new interstates, which bypassed their locations along the old roads. Rainbow Springs, Sanlando Springs, Dog Land, Everglades Tropical Gardens, Florida Reptile Land, the Waite’s Bird Farm—they died off. Frog City, Sunshine Springs and Gardens, Atomic Tunnel, Shark World, Bongoland, and—alas—Midget City, too, went under. Times were tough in the early sixties. Perhaps this explains why Disney’s announcement sounded like a godsend to these beleaguered mom-and-pop enterprises. “Anyone who is going to spend $100 million nearby is good, and a good thing,” the owner of Cypress Gardens was quoted as saying.

And he was terrifically wrong. About his own prospects, but also about the size of the investment. Disney promised more than $600 million. He was going to build a Magic Kingdom five times larger than the one he’d created in California. He also vowed to construct a rapid transit system as well as a thousand-acre industrial park and a jetport. “But the most exciting and by far the most important part of our Florida project—in fact, the heart of everything we’ll be doing in Disney World,” Disney said in a promotional film, “will be our Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. We’ll call it Epcot.”

Disney claimed that this model city would “take its cue from the new ideas and new technologies that are now emerging from the creative centers of American industry. It will be a community of tomorrow that will never be completed, but will always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and systems. And Epcot will always be a showcase to the world for the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise.”

Sound familiar? Like the Spaniards and Flagler before him, Disney was taking his second chance in Florida. His grand design—the reason why he was clearing forests, draining wetlands, remaking the place in his image—was to fashion his idea of utopia. “I don’t believe there’s a challenge anywhere in the world that’s more important to people everywhere than finding solutions to the problems of our cities,” he said. “But where do we begin—how do we start answering this great challenge? Well, we’re convinced we must start with the public need. And the need is not just for curing the old ills of old cities. We think the need is for starting from scratch on virgin land and building a special kind of new community.”

The way Disney sold it, Epcot would be a working community of twenty thousand. “It will never cease to be a living blueprint of the future, where people actually live a life they can’t find anywhere else in the world,” he said. “Everything in Epcot will be dedicated to the happiness of the people who will live, work, and play here.” The idea was to build high-density apartments surrounding a business center; beyond that would be a greenbelt and recreation area; the outermost rings would be low-density residential streets. There’d be “playgrounds, churches and schools … distinctive neighborhoods … and footpaths for children going to school” in Disney’s proposed utopia. A multimodal transportation system incorporating surface trains, a monorail, and a “webway people mover” would render automobiles unnecessary, à la Seaside.

Then came the rub: “To accomplish our goals for Disney World, we must retain control and develop all the land ourselves.” Disney demanded municipal bonding authority, three highway interchanges, and the creation of two municipalities together with an autonomous political district controlled by the company. In effect, Disney wanted his own corporate-controlled state within the state. “A sort of Vatican with mouse ears,” the historian Richard Foglesong termed it. In return, Florida would receive a perpetual stream of visitors, more sales- and gasoline-tax revenue, a long boom in construction and service jobs. “You people here in Florida have one of the key roles to play in making Epcot come to life,” Disney inveigled, like a true confidence artist. “In fact, it’s really up to you whether this project gets off the ground at all.”

And the people of Florida bit.

Though Disney wouldn’t live to see it, he was granted his Reedy Creek Improvement District, which is still “governed” by a supervisory board “elected” by the landowners—i.e., the Walt Disney Company. As described by a former head executive, Reedy Creek “gave us all the powers of the two counties in which we sit to the exclusion of their exercising any powers, and of course it let us issue bonds. We could do anything the city or county could do. The only powers that still reside on us from outside are the taxing power of Orange County, the sales tax of the state, and the inspection of elevators.”

Reedy Creek handles its own planning and zoning. It lays out roads and sewer lines, licenses the sale of alcoholic beverages. Building codes? Psh, Reedy Creek employs the building inspectors. It employs its own fire department. Contracts its own eight-hundred-member security force. Technically, it is within Disney’s rights to build an airport and a nuclear power plant within the Improvement District, if Disney so desires.

But that whole utopian city thing? The enticement that ultimately sealed the deal for the people of Florida? It was all a ruse. The Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow was just another theme park. And though more than fifty-five thousand people work in the Reedy Creek Improvement District by day; and though more than a hundred thousand patronize its stand-alone restaurants, clubs, and theaters every night—Reedy Creek retains a permanent population of about fifty. Most of whom are company executives or their family members.

Walt Disney demanded and received the powers of a democratically elected government, and his corporation ducked the botheration of, you know, constituents. Constituents who might challenge Disney’s top-down plans or even vote them out of power. The constitutionality of this arrangement has never been challenged. I suppose this proves no one minds the arrangement all that much. But I tend to think otherwise. I think it proves that the people of Florida are no different from patsies across time and space: too ashamed to admit when we’ve been had.

“By turning the state of Florida and its statutes into their enablers,” T. D. Allman writes, “Disney and his successors pioneered a business model based on public subsidy of private profit coupled with corporate immunity from the laws, regulations, and taxes imposed on people that now increasingly characterizes the economy of the United States.”

So, huh. I guess Disney did get his “showcase for free enterprise” and his utopia both, in the end.

Kent Russell’s essays have appeared in The New Republic, Harper’s Magazine, GQ, n+1, The Believer, and Grantland. He is the author of I Am Sorry to Have Raised a Timid Son. He lives in Brooklyn.

Excerpted from In the Land of Good Living: A Journey to the Heart of Florida , by Kent Russell. Copyright © 2020 by Kent Russell. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cooking with Steve Abbott

In Valerie Stivers’s Eat Your Words series, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

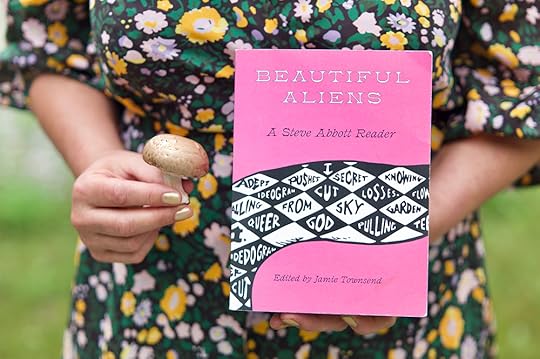

A mushroom like the one Abbott grew in his car.

The Haight-Ashbury poet and activist Steve Abbott (1943–1992) has had an unusual and charmed second act as a domestic icon, though he was not known for his cooking. Abbott was married in his midtwenties while he was a student at Emory University, and he had a daughter in 1970. After his wife was killed in a car accident in 1973, he became a single parent to two-year-old Alysia Abbott and moved to San Francisco with her in what we would now consider to be astoundingly bohemian circumstances. Among other legends is the time when Alysia was eight weeks old and Abbott “took some LSD and went into the bedroom to play with her,” tripping out on the baby’s rolling eyes and flailing legs. Abbott saw “a monstrous id” and explained that “I had to leave her presence because I was too psychically vulnerable.” He also relays that when Alysia was small, he survived by catnapping between work and childcare, and hitting the gay bars only between midnight and three in the morning (and presumably leaving her unattended). It worked out. As Abbott’s daughter grew, she became a sidekick and confidante. Photos from the time show Alysia posed in costume for the cover of one of Abbott’s poetry books or curled up with him on extraordinary seventies furniture, with obvious affection beaming from every frame.

In 2013, the grown-up Alysia published Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father, which details their experiences as a family. In part because of that book’s ongoing success, Steve Abbott’s work is back in print as of December 2019, in the collection Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader, published by Nightboat Books and edited by Jamie Townsend. Alysia has been a tireless promoter of her father’s legacy and explains in public appearances that she chose to tell their story the way she did because while gay parents have become more visible and accepted in America, the heritage of groundbreaking families like hers is less known. And so many gay parents of her father’s generation—including her father himself—died of AIDS that it has fallen on their children to tell their stories.

This can of tuna in oil sits on a vintage tablecloth from my Atlanta childhood. Below, checkered blue-and-white placemats also made by my mother in the same era.

Abbott’s work, as represented in Beautiful Aliens, is not very much about parenting. The book includes poetry, prose poems, novel excerpts, and nonfiction. When asked in an interview titled “About the Kid” why he doesn’t write about Alysia, he says, “I tend to write out of my obsessions and she doesn’t fit into them very directly.” His contribution to posterity was his role as one of the founders of the New Narrative movement, which included writers like Dodie Bellamy and, by some accounts, Dennis Cooper and Kathy Acker. The aims of New Narrative were to represent subjective experience honestly, to allow content to determine form, and to place the author’s role within a political and activist community. Abbott’s playful, loose, personal style and his exploration of relationships—mostly between himself and guys he was obsessed with—are emblematic of this approach. Townsend notes in their introduction to Beautiful Aliens that Abbott’s lifestyle of organizing readings, doing his own small publishing, and connecting and promoting artist friends was also a crucial part of the art. “New Narrative not only foregrounds the relational (the use of friends’ names, gossip, confession, the quotidian, the erotic),” Townsend writes, “it provides ample room for community critique though linguistic devices that dissect and open up traditional narrative writing (parataxis, metatext, metonymy, narrative intrusion). As such it seems an ideal mode for addressing ways in which writing necessitates a social body.”

Gussied-up casserole, shown with rainbow flowers in belated celebration of Pride Month.

For me, some of the most rewarding parts of Beautiful Aliens are Abbott’s essays about his friends and influences, such as the painter Odilon Redon and the Beat poet Bob Kaufman. His literary analysis of a Dennis Cooper paragraph on anilingus is a joy not to be missed, down to the meaning of the saliva-plastered hairs. My favorite work in the collection, however, is a poem about art and parenting titled “It’s a Strange Day Alysia Says.” The first lines go: “ ‘It’s a strange day’ Alysia says, ‘a green / bug in my room & now this mushroom growing in the car.’ ” This poem overjoys me because I can perfectly imagine the terroir of Abbott’s messy car that is able to grow a mushroom. It is similar to so many of our messy cars, especially the messy cars of parents with children, whose backseat foot wells tend to fill up with such a detritus of crumbs, toys, wrappers, and wet single socks that if only our cars, like Abbott’s, let in some rain, we all might grow mushrooms, too. I adore the unexpected creation—a mushroom!—that comes of this parenting “failure.” The poem’s next lines: “Maybe I should get a new car or at least / clean it up, fix the window like the kids say. / But how can I do this & still talk to angels?” These lines run through my head at crazy parenting moments. They provide sustenance.

Alysia’s book about her father has continued to move audiences in part because it taps into the universal well of familyhood that we all share, despite the different ways our families can look. And speaking of sustenance, one thing my very different family shared with Abbott’s is tuna noodle casserole. Abbott serves his with a side of broccoli in the story “The Malcontent,” which is about his fraught relationship with a flirtatious but allegedly straight dude named Jim, who has been sponging off him and sleeping in his bed. There are no specifications as to the recipe, but dollars to doughnuts it was just like the one I loved as a child, made from canned tuna, Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup, frozen peas, and bread crumbs. Incidentally, I’ve known Alysia Abbott since the late nineties, and it was only in reading her father’s book that I realized our families overlapped in Atlanta in the early seventies and that we could have both been babies on the same playgrounds or crossed in slings at the Varsity, though my earnest young Republican parents were extremely unlikely to have known hers.

A classic California writer deserves a classically Californian wine. This one is from the sought-after Russian River Valley, known for its chardonnays.

To honor Abbott, his parenting, and even the errant Jim, wherever he may be, I made two tuna noodle casseroles: one traditional version—I’ll admit I was a little scared of this—and one elevated version with tuna in oil, homemade white sauce, Parmesan cheese, baby kale, and, of course, mushrooms, though not ones harvested from my car. My spirits collaborator, Hank Zona, may have suffered silently at being asked to pair wine with a tuna noodle casserole, but he gamely offered a California chardonnay made by the winemaker Gary Farrell. This style of chardonnay’s soft, buttery notes make it a good pairing with cream sauces, and the Farrell version’s high acid content cuts through the dish’s richness. California wines are expensive, though (the Gary Farrell Chardonnay costs thirty-five dollars), so Zona also suggested a “Love White,” a chardonnay-like white blend from Broc Cellars. Made in a warehouse in Berkeley, this option is a natural wine that taps into New Narrative’s radical and experimental roots.

Both of my dishes had some things to recommend them—the seventies canned-soup casserole sure is fast, cheap, and easy!—and I was surprised by how easily the white sauce came together (it’s the first time I’ve made one) as well as how edible, if not highly recommended, the second casserole was. But my children wouldn’t try them, and neither had much flavor for the wine to hang on to. With tuna casseroles, like with parenting, it turns out to be about getting through the day as best you can, despite the mess in your car or that you’d prefer to be talking to angels. It’s only in hindsight that all those fast dinners and harassed days turn into something. What Abbott probably didn’t realize at the time he was being an “alien” in the Haight—a swinging, young, gay, single parent—and lamenting his double duties as parent and poet was just how much his unorthodox family acted as its own front in the battle for gay liberation, and how his legacy would outlive him, beautifully.

Seventies Tuna Noodle Casserole

2 cups egg noodles, cooked and drained

a 10 oz can Campbell’s cream of mushroom condensed soup

two 5 oz cans tuna, drained

1/2 cup milk

1 cup frozen peas

2 tbs bread crumbs

1 tbs butter, melted

Preheat the oven to 400.

Combine cooked noodles, soup, tuna, milk, and frozen peas in a medium baking dish. Stir the melted butter into the bread crumbs, and sprinkle them on top. Bake for twenty minutes, until the mixture is hot and bubbling and the bread crumbs have browned.

Better Tuna Noodle Casserole

half a 10 oz bag of egg noodles, cooked in salted water and drained

1 tbs olive oil

1 cup cremini mushrooms, sliced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1/4 cup white wine

4 tsp flour

1 3/4 cups whole milk

1/2 tsp salt

pepper, to taste

1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese

a 5 oz can high-quality tuna in oil, drained

1/4 cup sour cream

1 cup baby kale

2 tbs butter

1/4 cup bread crumbs

1/4 cup parsley, minced fine

Preheat the oven to 400.

Heat the olive oil in a medium-size skillet. Add the mushrooms, turn down to medium-low, and sauté until soft. Then add the garlic, toss, and sauté an additional two minutes. Add a quarter cup of wine, turn the heat up to high, and reduce the liquid by half. Dust the flour over the mushroom mixture, and cook, stirring, for two more minutes. Add the milk in a steady stream, stirring constantly, then bring to a boil, stirring so the mixture doesn’t stick. Cook until thickened, about four minutes after it boils. Add half a teaspoon of salt, and pepper, to taste.

In a medium baking dish, combine the cooked noodles, Parmesan cheese, tuna, sour cream, baby kale, and white sauce. Taste for seasoning, and adjust.

In a small saucepan, melt the butter, then add the bread crumbs, and sauté until toasted and brown. Combine with the parsley, and sprinkle the mixture on top of the casserole. Bake until the mixture is hot and bubbling, about twenty minutes.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

July 9, 2020

On Immolation

In her column “Detroit Archives,” Aisha Sabatini Sloan explores her family history through iconic landmarks in Detroit.

Part of the Heidelberg Project in Detroit, Michigan (Photo: Fren Lebalme)

For a period of time in 2014, I couldn’t stop watching the surveillance video of a person setting fire to the Heidelberg Project, a world-renowned art installation by Tyree Guyton in a residential area of Detroit. The recorded arson struck me as a performance piece in itself. In what appears to be the very early hours of the morning, a figure approaches the threshold of a structure called “Taxi House,” a home adorned by boards of wood that have been painted with yellow, pink, green, and white vehicles labeled “taxi.” There is a painted clock, real tires, and toy cars. A meandering, peach-colored line has been painted along a sagging corner of the roof, then it comes down onto the siding, where it moves geometrically, like Pac-Man.

The installation as a whole is like a painting brought to life, imbued with the spirits of Kea Tawana, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Robert Rauschenberg. In a recent profile in The New York Times Magazine, Guyton describes how he began the installation with his grandfather, an act of reinvention rooted in nostalgia. M. H. Miller describes the collection of carefully planned assemblages as “an act of Proustian reclamation, as if Guyton were creating a new neighborhood out of the one he’d lost, embellishing his and Grandpa Mackey’s memories out of the wreckage that surrounded them.” In the video of the fire that destroys “Taxi House,” the figure holds something that resembles a gallon of milk; after a short time, a fireball blooms, and the figure runs away.

The Heidelberg installation has the vibe of Plato’s lost city of Atlantis, the mythic civilization that sank into the ocean overnight after its people lost their sense of virtue. It also brings to mind Jason deCaires Taylor’s undersea sculptures, human figures engaged in activities like typing, playing the cello, or watching TV; cement bodies surrounded by schools of fish. What’s so remarkable about Guyton’s effort is that he’s constructed a frame around the present moment. The collapse he draws our eye to is not a myth or a dream of the future, it’s now.

Though Guyton had originally hoped for the installation to be a solution of sorts, the traffic it brings (around two hundred thousand people a year) also serves as a reminder of the tension inherent to a city undergoing gentrification. In a book written about the project, Connecting the Dots, one neighbor explains, “Every summer night we’ve got people riding up and down looking at what we’re doing. It’s an invasion of privacy. They look at us like we’re animals on display.”

From what I can tell, no motive ever emerged for the arson, and no arrests were made. The one person who checked into an emergency room for severe burns on the day of the fire had been trying to deep-fry a turkey. More fires have been set at the installation in years since.

Guyton exhibits widely, and has a special fan base overseas. Recently, he has decided to take the Heidelberg Project down. According to M. H. Miller, Guyton and his wife plan to “transform the buildings that still stand into a series of cultural and educational centers dedicated to the arts, and then build housing and work spaces marketed for artists out of this central core.”

As buildings around the country were set on fire in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, I thought about the Heidelberg arsonist. Widely dispersed memes featuring the Martin Luther King Jr. quote “The riot is the language of the unheard” have encouraged more and more people to see fire in the context of social upheaval not merely as an act of destruction but as an act of ritualized desecration. What language looks like at wit’s end. A kind of screaming.

So, what did we learn in the wake of the Heidelberg blaze? For one thing, the firefighters who came to put out the fire were delayed because none of the hydrants in the area were working owing to widespread water shutoffs across the city. But, also, the fire begs some of the same questions that Guyton’s work elicited when he first began in the eighties: Who is the artist? Who is the criminal? Who is the bystander? Who is the institution? Can you occupy more than one role at once?

*

The first photograph my father took for Newsweek magazine was of the 1967 uprising in Detroit. In the image, a young man looks toward the camera as a warehouse burns bright orange behind him under a dark night sky. My father likes to point out how he caught the boy in a moment of bewilderment, of total awe. Recently, I asked my dad to take my wife and me to the place where the image was taken. My mother came along, too.

My dad begins the journey by veering into oncoming traffic, because the street has gone two-lane; a street construction project that has turned the neighborhood into an obstacle course. As we make our way down East Grand Boulevard, a painted storefront next to Flamin’ Moez Soul Food reads US AND THEM. The grandiosity of what my parents call the Boulevard clears, and now we are passing grassy fields. We are taking a detour from our detour toward another detour.

We drive past the Packard plant, which has become a kind of unofficial graffiti museum. The British artist Banksy consecrated the space a few years back with a painting of a black boy in a strange black suit holding a can of red paint, next to the message “I remember when all this was trees.” I can’t say I get it, given that the area is and long has been surrounded by overgrown lots. Banksy’s arrival prompted a minor controversy when local gallerists removed the section of concrete he’d spray-painted and sold it for over $100,000. A bit farther down the block, a huge sign promises COMING SOON! PACKARD PLANT BREWERY. I think about the way that ruin is being involved, here, in a kind of transaction. The image that comes to mind is Goya’s painting of Saturn devouring his son.

We pass a public art installation featuring white figures kneeling. On Woodward, a billboard shows a black cop with his arms crossed and it reads: ANSWERING THE TOUGHEST CALL. Later, we will find out that the night before, Detroit cops, “fearing they were under fire,” drove into a crowd of protesters.

Our plan is to first find the site of the Algiers Motel, where a group of police and National Guard killed three people and tortured several others in the midst of the 1967 uprising. My mom says, “On the map it looks like an empty field.” Up a ways, there is a sizable gathering of Black men on the steps of a church, with signs that say GOD BLESS OUR FATHERS. Black men and boys are holding their hands in the air in surrender or praise.

The site of the motel is now a well-cared-for park, gated, mostly empty and surrounded by brick walls. We pause, then turn back into traffic.

Next, we attempt to find the place where my father took the photograph that began his career. After getting caught in a loop in a fancy neighborhood and circling a beautiful garden where a white man in a fedora appears to be considering purchasing the property, we turn in a direction my father hadn’t planned to take. My mother says she’s “going to call Rodney,” my father’s best friend, which is a euphemism for “we’re lost.”

At a red light we find ourselves staring at the bottom of a toppled SUV. It takes a moment to decipher the car’s undercarriage, a desert-colored thing at an odd angle. At the intersection, people are streaming across the street, like liquid, toward what we now understand to be an accident. The crowd does not even look at the wreckage as they cross. I peer more closely into the window of the toppled car but can’t make anything out. A man holding a baby keeps darting toward it. There are fire trucks and a police car, city officials wearing masks and looking at the vehicle, but no one is touching anything. The plan of action seems to be hanging, still, in the air.