The Paris Review's Blog, page 153

August 11, 2020

The Unreality of Time

© Allen / Adobe Stock.

I was listening to an episode of the BBC podcast In Our Time, on which a group of English scholars was discussing the French philosopher Henri Bergson, when one of them mentioned an essay called “The Unreality of Time,” originally published in 1908, by a philosopher named John McTaggart. The phrase startled me—I was writing a book called The Unreality of Memory. It’s possible I’d heard the title before and forgotten I knew it—as the scholars note, it is a famous essay. (“Is forgotten knowledge knowledge all the same?” is the kind of question we asked in my college philosophy classes.) In any case, I had never read it. I paused the podcast and found the essay online, curious what I’d been referencing.

McTaggart does not use “unreality” in the same way I do, to describe a quality of seeming unrealness in something I assume to be real. Instead, his paper sets out to prove that time literally does not exist. “I believe that time is unreal,” he writes. The paper is interesting (“Time only belongs to the existent” … “The only way in which time can be real is by existing”) but not convincing.

McTaggart’s argument hinges in part on his claim that perception is “qualitatively different” from either memory or anticipation—this is the difference between past, present, and future, the way we apprehend events in time. Direct perceptions are those that fall within the “specious present,” a term coined by E. R. Clay and further developed by William James (a fan of Bergson’s). “Everything is observed in a specious present,” McTaggart writes, “but nothing, not even the observations themselves, can ever be in a specious present.” It’s illusory—the events are fixed, and there is nothing magically different about “the present” as a point on a timeline. This leads to an irresolvable contradiction, to his mind.

Bergson, for his part, believed that memory and perception were the same, that they occur simultaneously: “The pure present is an ungraspable advance of the past devouring the future. In truth, all sensation is already memory.” He thought this explained the phenomenon of déjà vu—when you feel something is happening that you’ve experienced before, it’s because a glitch has allowed you to notice the memory forming in real time. The memory—le souvenir du présent—is attached not to a particular moment in the past but to the past in general. It has a past-like feeling; with that comes an impression one knows the future.

Bergson was hugely popular in the early twentieth century. He was friends with Marcel Proust—and married to Proust’s cousin—and his ideas influenced many other Modernist writers and artists. He is less well-known and celebrated now in part because of a years-long debate with Albert Einstein over the nature of time. Bergson believed that “clock-time” and what he called capital-T Time—time as we experience it, a lived duration—were entirely different. It was this other kind of time, time in the mind, that interested Bergson. Einstein thought this was poppycock. “Il n’y a donc pas un temps des philosophes,” he said on April 22, 1922, at an infamous lecture in Paris: There is no philosophers’ time. Einstein felt his theory of relativity was the final word—time is what clocks measure, in their own frames of reference—and that Bergson did not understand the theory. Einstein thought the separation of time and space was dead as a concept, that he’d killed it. He was wrong—we still think of time and space as different, even if we grasp relativity. Nonetheless, many took his side, and it did lasting damage to Bergson’s reputation.

Philosophers and physicists still speak of the specious present. “The true present is a dimensionless speck,” Alan Burdick writes in his book Why Time Flies. “The specious present, in contrast, is ‘the short duration of which we are immediately and incessantly sensible’ ”—he quotes James. The specious present, Burdick adds, “is a proxy measure of consciousness.” It is what we think of as now. Not the general now, as in “the way we live now,” but right now.

And how long is now? In an eight-minute YouTube video with over one million views, called “What exactly is the present?,” the physicist Derek Muller attempts to explain. According to Muller, engineers working on the problem of syncing video and audio in preparation for the first live television broadcasts found that viewers didn’t actually notice if they were a little out of sync, but there was “an asymmetry”—the sound can lag the video by up to 125 milliseconds before people notice something’s wrong, but if the sound leads the video by more than 45 milliseconds, they know it’s off. Of course, sound and “video” aren’t synced in the real world either: When we watch someone walk down the street, away from us, dribbling a basketball, the sound takes longer and longer to reach us, but we still perceive the bouncing sounds and the bouncing visuals as simultaneous. That’s because “now” is not a speck but a span, of about a tenth of a second. During that interval, Muller says, “your brain can perform manipulations that distort your perception of time and rearrange causality”—syncing up the audio and video, like a live broadcast on a slight delay. It’s as though your brain takes in the information and processes it a little before you do. Researchers have exploited this discovery to fool people into thinking a computer program can read their minds, that it knows what they’re going to do before they actually do it. We’re capable of perceiving an effect before we realize we’ve caused it.

The neuroscientist David Eagleman has said, “You’re always living in the past”—meaning not that the past haunts us, though it does, but that what we experience as the present is in fact the past, the very recent past, the just past. In a way, then, time is memory—not clock-time, perhaps. Not Einstein’s time. But human time is human memory.

*

I started writing The Unreality of Memory in 2016, in what seemed like a state of emergency. In the months leading up to the election, I was following reality like it was TV, as though every day ended in a cliffhanger. There was something addictive about Donald Trump’s incredible rise—incredible in the original sense, unable to be believed.

This profound sense of unreality reached its culmination on the night of the election. Earlier that day, I’d felt light on my feet, optimistic—I risked jinxing it by purchasing proleptic champagne. I remember the moment, late into the night, when a win for Hillary Clinton had become vanishingly unlikely, though not technically impossible. John and I were watching the returns come in on his laptop, and stress-drinking, though not champagne—that stayed in the fridge. We watched a newscaster nervously talk through the maps showing Clinton’s last outs. John turned and looked at me in horror and said, “He’s going to win.” A bottomless moment.

In the summer of 2017, I spoke on a panel called something like “Art in the Age of Trump.” One writer on the panel insisted that the role of the artist is empathy; with an air of limitless patience, he suggested writing a story or a novel from the perspective of Donald Trump—to attempt to understand him. I felt a portion of the audience grow increasingly restless and frustrated. One man cried out, “There’s no time!” I recognized the note in his voice, a note of urgency unto panic.

That panic, for me, has mostly passed. It has not passed for everyone—not for trans people I know, or for immigrants and the families of immigrants. But as scared as I am of the future, I must admit that for now I’m fairly safe, even comfortable. When news of another school shooting hits—the word “another” seems inadequate—or when I read calm, measured reporting of slowly progressing disasters like ice melt in Antarctica (or, or … I hate these placeholder lists of atrocities), I’m disturbed—logically I’m disturbed. I recognize the facts as disturbing, though what’s no longer shocking or even surprising can verge quite horribly into boring. I still find Trump evil, but I no longer find him interesting. And I still have to work (how can it be so, that I have to waste my life this way, when the world is ending?), eat, sleep, and start over again. I move through the days in a flux of anxiety and denial. But that fear in the background changes things. It changes how I make decisions. I can’t say how long this relative safety will last. It feels like a suspended emergency—like the specious present has been extended in both directions. Now feels longer.

Is the world ending? Which end is the end? For a while I told people, facetiously I suppose, that I was writing a book about the end of the world. Once at a family lunch, my aunt asked me what I was writing about, and I said I was writing about disasters. “What about disasters?” she asked, and I wasn’t sure how to answer. My mother stepped in with a much better elevator pitch: “Isn’t it more about how we think about disasters?” My own thinking, at least with regard to the disaster—the end—has shifted. To be clear, I do worry that civilization is doomed. (The word “worry” seems inadequate; I almost wrote “believe.”) But I’m not sure the doom will occur like a moment, like an event, like a disaster. Like the impact of a bomb or an asteroid. I wonder if the way the world gets worse will barely outpace the rate at which we get used to it.

I don’t have faith that my sense of history, from here inside history, is accurate, or that the view through the rickety apparatus of my body is clear. Eagleman notes that “most of what you see, your conscious perception, is computed on a need-to-know basis.” We ignore what our brains—independently!—deem unnecessary. There is no other self, to tell yourself what to do. The German biologist Jakob von Uexküll had a term for what animals pick up on in their surroundings: the Umwelt. The Umwelt is always limited by the organism’s equipment, by its immediate needs. Eagleman, explaining Uexküll’s ideas, writes: “In the blind and deaf world of the tick, the important signals are temperature and the odor of butyric acid. For the black ghost knife fish, it’s electrical fields. For the echo-locating bat, it’s air-compression waves. The small subset of the world that an animal is able to detect is its Umwelt. The bigger reality, whatever that might mean, is called the Umgebung.” The Umgebung is the unknown unknown, the unperceived unperceived.

There’s the matter of perspective, and there’s also the matter of scale. A young poet I know noticed that I often write about the self watching the self. He quoted an essay in which I wrote that I fantasize in the third person, connecting this to another piece, which mentions Robert Smithson’s earthwork sculpture Spiral Jetty. “Do you think land artists moreso desired their work to be experienced within (standing on the rocks, beside the hole) or from above (via camera, airplane)?” he asked me in an email. My mind spiraled off. It’s very hard for me, I told him, to be “present in the moment”—I’m always going meta, narrativizing, thinking about what I’m thinking about, imagining the future—and then in my specious present, I’m comparing what is happening to what I had imagined would happen, my souvenir du présent to my memoire de l’avenir. I didn’t say that Smithson didn’t mean for Spiral Jetty to be seen at all, or at least not for long—he built it when the water levels in Great Salt Lake were unusually low: a comment on ephemerality at epic scales. Finished in 1970, the jetty had disappeared by the time he died, in 1973, in a plane crash while surveying sites for a new piece. It stayed hidden for thirty years. Since 2002, drought has kept the water levels low, so it is now usually visible. The ephemerality doubles back: The design exposed, it’s Smithson’s intention, human intention, that’s ephemeral.

*

I’ve grown tired of reading about disasters. Friends send me links, and I click them and skim halfheartedly. One article, published just after the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris was partially destroyed in a fire, references the sociologist Charles Perrow’s 1984 book, Normal Accidents, which notes that safety systems increase the complexity of technology, inevitably leading to unforeseen errors, which can be catastrophic. The Chernobyl meltdown was triggered by a safety test. (In 2019, HBO made a series about Chernobyl, but I didn’t watch it; I’m tired of disaster movies.) Another questions the slippery use of “we” in writing about climate change, as in “We are emitting more carbon dioxide than ever.” “The we responsible for climate change is a fictional construct, one that’s distorting and dangerous,” writes Genevieve Guenther, a writer who founded a volunteer organization called EndClimateSilence.org. “By hiding who’s really responsible for our current, terrifying predicament, we provides political cover for the people who are happy to let hundreds of millions of other people die for their own profit and pleasure.” It provides cover, in other words, for the giant corporations, like ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP, that are responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions. In 2017, the Carbon Majors Report revealed that a hundred companies account for more than 70 percent of those emissions. “Always remember that there are millions, possibly billions, of people on this planet who would rather preserve civilization than destroy it with climate change,” Guenther writes. “Most people are good.”

That sentence gives me pause. “Most People Are Good” is also the name of a country song I hate: I believe this world ain’t half as bad as it looks, the guy croons in the chorus. The more I think of it, the more I disagree. I don’t think most people are good, or bad, for that matter. I think people are neutral. From a distance, they look almost interchangeable. It seems to me that “good people” can become “bad people” when provided the opportunity within an existing power structure—to claim and exert power at a deadly cost to others and get away with it. It is not an act of empathy for me to say that Trump is not inherently evil, but “we” have created opportunities for him to be evil. To say that most people are powerless—that evil is a role. In some novel I once read, one character reminded another that a “revolution” is simply a turn of the wheel; it doesn’t break the power structure, it just changes who is on top. I think about that all the time. I think about these lines from an Ilya Kaminsky poem: “At the trial of God, we will ask: why did you allow all this? / And the answer will be an echo: why did you allow all this?” We, you and I, are not corporations, but we do give those corporations godlike power. “They” is a dangerous construct, too. There’s no one to dismantle them but us.

I recently read my friend Chip Cheek’s novel about a honeymoon gone wrong. It starts off feeling escapist—the publisher clearly marketed it as a beach read—but it turns into a kind of apocalypse novel. It’s about what ruin really looks like; there are consequences for the couple’s immoral (and stupid) behavior, but in the end we’re denied the pleasure of an all-out catastrophe, the realization of what Sontag called our “fantasies of doom,” our “taste for worst-case scenarios.” The novel is set in the fifties, but even period fiction written now is climate fiction, I realized; it’s always on some level aware of what we’ve reaped. The storms have levels of foreboding.

My research into past disasters—the plagues and the almost nuclear wars—was often oddly comforting. We’re still here, after all. But I can only take so much comfort in the past. This point in history does feel different, like we’re nearing an event horizon. How many times can history repeat itself? It’s generally accepted that our memories are fallible—that they’re missing information, that they include new details we’ve simply made up—and that over time they are less and less reliable, as we keep rewriting the inaccuracies. We’re more trusting, though, of what we take to be our direct experience, our experience of the present. I’m drawn to Uexküll’s idea of the Umwelt; like a tick or a bat, we only know what we know. I’m drawn to Bergson’s idea that perception and memory are coterminous. It suggests that we don’t experience reality as it is, and then warp it in recall, but that even the first time we live through X, we are already experiencing our warped version of X.

Elisa Gabbert is the author of five collections of poetry, essays, and criticism, most recently The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays and The Word Pretty.

Excerpted from The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays , by Elisa Gabbert. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2020 by Elisa Gabbert. All rights reserved.

August 10, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 21

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“It’s been a year of storms—political, viral, and, this past week, meteorological. At the Review, two of us lost power for a couple of days after Hurricane Isaias. But to paraphrase Emily Dickinson, the Daily—and our social media, our virtual events, and the production of the quarterly—could not stop for that. I felt lucky to be part of a team that didn’t hesitate for a second to offer help. Hopefully, as far as readers could tell, TPR didn’t miss a beat. And so I’m thinking a lot right now about the power of community. Throughout the pandemic and the attendant lockdown, through all the political agony, through the many major and minor crises of the past months, friends, kind strangers, public commentators, essential workers, shopkeepers, artists, and activists have been unusually generous with their time and energy, whether raising a virtual glass over Zoom, taking to the streets in solidarity, sending a donation where it’s needed, or helping to clear fallen trees. I hope you, too, are feeling the love of your community right now, and I hope these unlocked pieces from the Paris Review archive offer some much-needed respite or an opportunity to think deeply about what it means to support one another. Unlocked this week is all the work TPR has published by a writer who has been very much a part of this year’s pressing conversations, the poet and essayist Cathy Park Hong. Stay safe, and happy reading.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Cathy Park Hong. Photo: Beowulf Sheehan.

Cathy Park Hong has been a regular Paris Review contributor for more than a decade. Her poems combine whimsy and humor with precise and often gymnastic linguistic manipulations to interrogate how words convey and carry history, community, and, most pointedly, racism. Her nonfiction debut, Minor Feelings, which came out earlier this year, is part memoir, part work of social criticism that explores Asian American identity and broadens Hong’s investigation of how language upholds—but also has the power to fight—hate and racism.

The Review has published Hong’s poems in three issues, and in 2020, Hong became not only a Paris Review author but an interviewer as well, conducting the Art of Poetry interview with Nathaniel Mackey in issue no. 232. But perhaps the best place to start your deep dive into Hong’s work is with this Daily excerpt from Minor Feelings, a meditation on the comedy of Richard Pryor:

In Pryor, I saw someone channel what I call minor feelings: the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic, built from the sediments of everyday racial experience and the irritant of having one’s perception of reality constantly questioned or dismissed.

These five poems, published since 2009, showcase Hong’s insight into the histories of words, her formal dexterity, and her ever-alert social conscience. They’re also always armed with irony and humor. Here are the first lines of each to whet your appetite for more.

“Garçon, you snore so rhapsodically but hup hup … ”

“A heartvein throbs between her brows: Ketty-San’s … ”

“I want to write like a man, probing … ”

“The whole country is in a duel and we want no part of it … ”

“Ate stew, shot a man … ”

Finally, there is Hong’s interview with the poet, novelist, critic, and National Book Award winner Nathaniel Mackey. In The Art of Poetry No. 107, Hong and Mackey find themselves to be fellow travelers along many roads, discussing their shared passions for postmodern poetic practice, the insider language of subcultures, and much more. At one point, they delve into the ways their poetry and criticism overlap. Mackey explains:

I’d say my criticism has informed my poetry very organically and intimately. It’s no accident, no coincidence, that the various writers and artists whose work is addressed in my criticism are those who have informed and influenced my writing. I went to school in their work. My criticism might be said to be my class notes.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

Comics as Place

In his column Line Readings, Ivan Brunetti begins with a close read of a single comics unit—a panel, a page, or a spread—and expands outward to encompass the history of comics, and the world as a whole.

Robert Crumb, “A Short History of America,” panel 1, 1979

Most comics focus on the actions of a figure, and the narrative develops by following that figure as it moves through its environment, or as it is commonly referred to by cartoonists, who have the often tedious, time-consuming task of actually drawing it, the background. One widely used cartoonist’s trick is to draw/establish the setting clearly and then assiduously avoid having to redraw it in subsequent panels, or at least diminish the number of background details as the sequence progresses. After all, once this setting/background has seeped into the reader’s brain, the reader can and will fill in the gaps. Moreover, sometimes drawing the background would only clutter the composition and distract the reader from the emotional core of the narrative, and so the background might judiciously disappear altogether, having outlived its graphic usefulness, until the next shift in scene.

Robert Crumb’s 1979 “A Short History of America” upends all of the above. It is a small miracle of concision and grace, consisting of a mere twelve panels that span across four pages (of three horizontal panels each) and roughly a hundred and fifty years of history. Every line, every mark in this comic imparts not only texture, but vital narrative information. In some ways, this short piece encapsulates the very art form of comics: one panel becomes panels, becomes a page, becomes pages, becomes story. Here the background is not simply a component of the story; one might say it is entirely the story.

Robert Crumb, “A Short History of America,” panel 2, 1979

The comic is bookended by two pieces of nondiegetic text. We start with the title hovering above a pastoral scene, nature as yet unspoiled: trees, deer, birds, and a gently sloping hill. We can safely assume this is America, but when? It could be yesterday, or thousands of years ago. We deduce that the second panel shows this same setting not long after, because of a key continuity: the trees, placed in the same position inside the two panels, haven’t grown much. Our eyes adjust quickly to repetition and become acutely sensitive to any deviation, however small. Instantly, we take in the hill and felled trees, along with the introduction of the railroad track, upon which chugs a small train, billowing steam as it disappears into the distance. The wild animals are gone, a visual shorthand for the encroachment of humans. Because of the train’s presence, we infer that these first two panels take place in the early-to-mid-nineteenth century. In the third panel, a few birds glide in the sky, recalling the first panel. The hill remains in the scene (though altered), as well as the train track, but years must have passed, because we also see a house, shed, and cart (signifying “farm”), as well as a dirt road (signifying “town”), telegraph wires, and a man with horse and buggy. Will this fellow be our main character?

Robert Crumb, “A Short History of America,” panel 3, 1979

No such luck. In the second page, as details accumulate, the main characters appear to be the sloping hill, the modified house (complete with handsome picket fence), and the road (branching into both a walkway and crossroad, and eventually expanding its width). The home has become a homestead, judging from panels 4 and 5. A signpost hints there are towns nearby, with quantifiable distances. On this page, information accretes slowly but surely. Structures multiply: we see a reservoir, places of business, warehouses, railroad tracks (now plural), larger carriages, a relatively fancy brick building, and wires galore. The main road has been well worn in panel 5, but repaired by panel 6. I am excited when a new character is introduced in panel 4: a sapling. By panel 6, it has matured into a healthy full-grown tree. Meanwhile, the fence has aged, shrunk, and died. Fortunately, the hill is still visible, grounding us in the original scene.

Robert Crumb, “A Short History of America,” panels 5 and 6, 1979

When we get to page 3, we have a sense from context clues that roughly a decade is passing between each panel. The house transforms into a store, and diegetic text in the form of signage and logos first appears on this page; the landscape thereafter will be forever permeated by advertising and sales. Crisscrossing wires and cables usurp the sky in panel 6. Streetcars and motorcars are introduced and morph with time. The town sprawls, palpably congesting the space. Lamps, traffic lights, sidewalks, and neon signs clutter the panels. We begin to experience sensory overload, but then in panel 8, an abrupt shift: the town feels desolate and devoid of bustle, the street and sidewalk are in disrepair, businesses have failed, and a roustabout leans on the light post. The Great Depression (we surmise) has brought everything to a crashing halt. Even the tree that we have watched grow up and grow old has suddenly vanished, and with its death the panel truly becomes elegiac.

Robert Crumb, “A Short History of America,” panels 7 and 8, 1979

As page 4 brings us to a close, time continues its detached, mechanistic march, and the environment clearly possesses its own consciousness and will. Density is destiny. Cars have become stand-ins for humans. With the demise of streetcars and their cables, some of the techno-clutter has lessened, but wires still dominate the air. The street lamp that barely changed on the previous page seems to have come alive, its design streamlining; the cars, however, may have undergone an inverse process of clunkification. Whether these aesthetic changes are an evolution or devolution is left up to the reader. The reappearance of people in the final panel implies a glimmer of hope, although the sign OAKWOOD VILLAGE is sardonic; the reader recognizes it as an empty gesture of reclamation, as the original bucolic scene has been decimated, the stubborn hill its only ghost. The final, non-diegetic text asks us, “What next?!!” The extraneous punctuation indicates a mixture of shock, dismay, and bemusement. We can picture the artist, head shaking, standing at a busy street corner, wondering how we got here.

Robert Crumb, “A Short History of America,” panels 11 and 12, 1979

Incidentally, in 1988 Crumb drew an intriguing one-page epilogue to “A Short History of America,” although some may not consider it “canon” (to borrow the language of superhero fandom). Nonetheless, the epilogue is worth examining. The story suddenly jumps far forward in time, imagining three possible future scenarios for America, a sort of choose-your-own-adventure for humanity that ranges from inferno to purgatory to paradise. There must be an optimist lurking within Crumb, because the strip concludes with, and thus favors, the most positive choice of the three.

Crumb is best known as a trenchant satirist, having created many iconic characters of the sixties counterculture, such as Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural, along with what might be the most widely dispersed image—endlessly, criminally copied—from what came to be known as “underground comix”: Keep on Truckin’. Although Crumb did not invent the underground comic, his Zap Comix #1 (1968) is considered the watershed publication for the movement. Preternaturally talented, even the comics Robert Crumb drew as a child display an impressive command of storytelling and form; from the outset, his figures possessed true heft, convincingly existing in physical space. Throughout his career, Crumb has plumbed the dark recesses of his own psyche as well as the underbelly of the American soul, occasionally wandering into the proverbial “too-far” corner. Always a diligent observer, his best work, such as “A Short History of America,” transcends satire and shock and instead evinces a deep empathy for spaces, people, and life. Today, there are comics for an adult audience, and there is an entire graphic novel industry to prove it; this development may have been delayed, or even nonexistent, without Crumb.

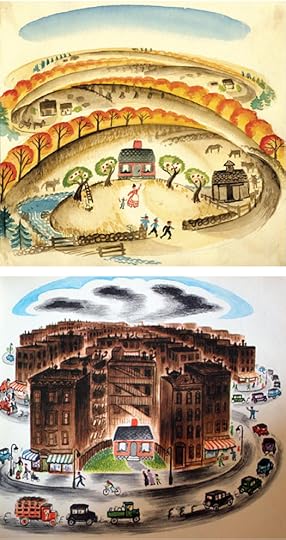

Virginia Lee Burton, The Little House, 1942

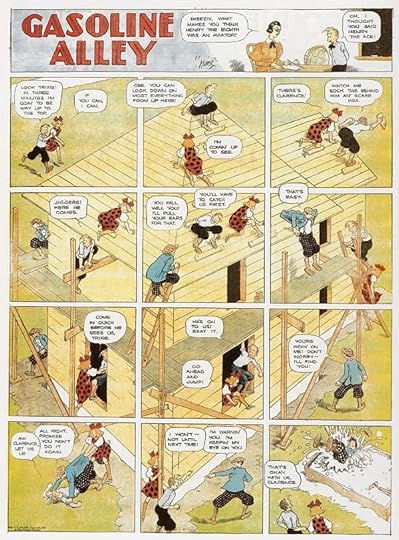

One way to analyze the multifarious comics form is in terms of lineages, and one possible precursor (or distant relative) of “A Short History of America” might be Virginia Lee Burton’s 1942 classic children’s book The Little House, which follows the life of a house from 1900 to 1940 as its environment continually changes, eventually crowding, dwarfing, and neglecting it. The tale ends happily, I should note, through the house’s being repaired and relocated by the great-great-granddaughter of its original builder. We should all be so lucky. Another sharer of DNA may be a series of Gasoline Alley Sunday comics from 1934. In these successive strips, the cartoonist Frank King draws the action unfolding within one continuous space: we see a house being built, week to week, from foundation to finish, the panel grid dividing the depicted space into discrete moments in time. These comic strips remind me of Art Spiegelman’s observation, unsurpassed in its elegance, that “comics are time turned into space.” There is no better definition of the cartoonist’s essential practice.

Frank King, Gasoline Alley, 1934

Arguably, any fragmentation of space immediately suggests the passage of time, but in comics time can pass in different directions, overlap, or stop. Because comics are static, not temporal, they can be thought of as physical objects, solid and tangible in their external form (page, chapter, book), but plastic and elusive in their internal workings. Cartoonists, like their readers, generally move forward, but at any time might decide to change directions or skip around, trying to take in the whole.

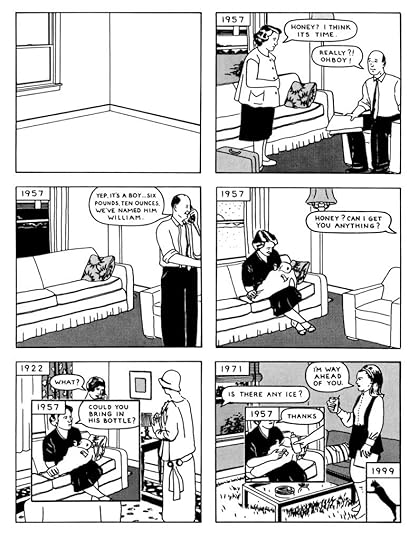

Richard McGuire’s highly influential 1989 story “Here” is another tale that could be thought of as a direct descendant of “A Short History of America”; if so, the parent has given birth to a child prodigy. It is a short piece, just six pages, each anchored by what appears to be six equally sized panels, suggesting an even flow of time. However, by the fourth panel, the reader enters terra incognita: the panels and the space within them are subdivided into increasingly complex grids within a grid, and time starts jumping backward and forward in unpredictable intervals. While the story always remains in one very particular space, the corner of a room (“here”), the reader views the entire history of that space, both cosmic and mundane, with space-time fragmenting into a multilinear peephole: sometimes passing slowly, at other times hurtling unfathomably. The scenes bounce, comment, and riff on each other, and the story becomes a meditation on birth, death, the cyclical workings of the universe, family, and America’s problematic history.

Richard McGuire, “Here,” page 1, 1989

One is reminded of Michelangelo chiseling away at marble, revealing the hidden form latent within it; only in this case, the marble is the totality of time. A better 3D metaphor might be Chinese carved-ivory spheres: these concentric, nested orbs are ingeniously constructed so that the balls move freely inside each other, and holes on their surfaces allow the holder to catch piecemeal glimpses of all the inner balls. “Here” functions along similar principles. Furthermore, with the expanded, graphic-novel length version of Here (2014), which delves deeper into its many themes, the book becomes a kinetic sculpture: the corner of the room is not drawn, but rather implied by the book’s spine, and the pages in our hands likewise become the walls.

Two other noteworthy strips along these lines were drawn by Chris Ware in the early nineties. One is a Big Tex page, an homage to the aforementioned Gasoline Alley strips but with a darker-edged humor, also depicting an isometrically projected and panel-divided single space, except now covering a much longer span of time, which is revealed to be moving backward. The other is an untitled one-pager (let’s call it “Lamp”), originally black-and-white but colored in for the 2003 collection Quimby the Mouse. Ware has often acknowledged the influence and inspiration of McGuire’s work, and in this variation on “Here,” we focus not on a space, but the life cycle of a single, humble object, from store to home, room to room, lampshade to lampshade, decade to decade, and finally to a new home. Through the lamp, we experience the lives of the unseen people in its environment: love, sex, marriage, birth, divorce, attachment, abandonment, acceptance, illness, death, even a tornado. The elliptical narrative unfolds through casual-seeming yet precise fragments of dialogue, as well as through closely cropped, minimal scenery. Every detail is densely narrative-packed, like the family snapshots that unwittingly chart fashion trends, the vagaries of human relationships, and the travails of aging.

Chris Ware, Untitled, (excerpted – 1/2 page), from Quimby the Mouse, 2003

Drawing the past perhaps allows cartoonists a way of understanding the present, with the ultimate hope of beneficially affecting the future. In its immaterial form, the past haunts our memories and imagination, its effects lingering even when repressed, distorted, or denied. In its material form, the past manifests itself in every extant molecule, in all that surrounds us or is us, at any given moment, every consequence a subsequent cause. The genius of comics is that it splits the difference between time and space—the abstract and the concrete—in an accessible, unassuming, and lyrical way. History, after all, exists only as dreams or ruins.

Ivan Brunetti is a professor at Columbia College Chicago, the author of Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice and Comics: Easy as ABC, and the editor of both volumes of An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories. His drawings occasionally appear in The New Yorker, among other publications.

August 7, 2020

Texas History

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces in real time the moments before her daughter leaves for college. The column ran every Friday in November, January, and March. It returns for a final month this August.

The Baker Hotel

The Baker Hotel rose above the Texas trees so straight ahead we didn’t trust the turns we were told to take. I pulled off I-20, and my daughter, Indie, read directions from her phone. I took a left, away from the building that loomed like a castle in the distance. It felt as if we were going in the wrong direction, until we turned onto Oak Street. As we got closer to the fourteen-story hotel (abandoned since 1970), we leaned down to marvel at the top-floor balcony, at all those empty rooms towering over the small town of Mineral Wells, fifty miles west of Fort Worth.

The state reopened in May, and the makeshift sign that had been hanging on the side of Applebee’s (Open To Go) came down. For forty-nine days, before reopening, the state of Texas had been limited to essential businesses, and while Governor Greg Abbott declared a statewide emergency, he never issued a formal Stay-At-Home order. All that time, I only went to the grocery store or 7-Eleven, darting with a Pac-Man-savvy down aisles, away from the maskless. Only on July 2, after the reopening of Texas proved to be a disaster, did Abbott mandate the wearing of masks.

When Indie began her senior year last fall, she was gone more than she was home—band practice and contests, game nights, working until 1 am sometimes at her restaurant job, going out with friends, hanging out at their houses. I understood it was a prelude, a slow and increasing separation to prepare us for her leaving. Suddenly we were both at home, navigating a new direction.

It’s hard to tell when spring turned to summer, every day the same, and for so many of those days I wondered if Indie’s last year at home would turn out not to be the last year at all. But when her university announced in June that they would hold classes on campus in the fall, I wanted to make these very last days something we’d both remember.

We call them half-tank trips, because that’s as far as we go, half a tank. We never leave the car, and we’re back home within an hour or two. Indie prefers I surprise her with the direction and destination, so it’s only after we leave—about once a week—that I tell her where we’re headed.

We live forty miles north of Dallas in a town crowded by highways, concrete, and construction. Population: 142,173. The cities we visit hover between one and five thousand, except for Mineral Wells, which is around fifteen.

This summer, we’ve gone in search of an abandoned motel just north of town (never found it); followed farmland for nineteen miles to Pilot Point, Texas, where the bank robbery scene in Bonnie and Clyde was filmed; toured a town nicknamed “Gingerbread City” for the architecture of its houses; placed silk wisteria flowers on my parents’ grave; taken a fifteen-minute drive to the largest mansion in the state; learned the histories of towns as Indie read them from her phone; parked in front a saloon built in 1873, the last stop on the Chisholm Trail before the Red River; we’ve wondered at empty train depots; pulled into the parking lots of the First United Methodist Churches in Nocona and Pilot Point and Sanger, where my grandfather served as the preacher decades ago. I took photos of all these places from the car, photos that will one day be an archive of the summer Indie left for college.

Indie and I’ve watched Ghost Adventures for years, following Zak Bagans and his crew through abandoned hotels, dusty mansions, and rusty prisons. One episode, “Crazy Town,” featured an investigation of The Baker Hotel and one of its ghosts, a woman who fell from the balcony in the thirties.

Opened in 1929, The Baker Hotel boasted 450 rooms, two ballrooms, a beauty shop, a bowling alley, a gymnasium, and the first Olympic-size pool in the country. It was a high-class destination in the thirties and forties, but once the interstate system led traffic away from the city in the sixties, the hotel suffered a decline until its closure. The hotel is currently being restored. As we drove around the construction fence, Indie read that Judy Garland stayed in the hotel in 1943 and mailed a letter from the post office up the hill from the hotel.

Rolling through these quiet towns, we note storefront signs: Please wear a mask. All Customers Required to Wear a Mask. No mask, no entrance. And the one we saw on the front of an antique store: Governor Abbott recommends wearing masks or keeping a 6 foot distance!!!

What stays with us, sometimes, is not what we expected to find, but what we found instead. Beyond the town square courthouses, the landmarks and landscapes and Fleetwood Mac’s Greatest Hits, beyond the Office Ladies episode for “Casino Night,” when we learned it was John Krasinki’s first on-screen kiss (Jenna Fischer’s second)—Indie and I encountered a truth we wouldn’t have known as sharply had we not turned through these small pockets of Texas: the 2020 flags promoting a second term.

Could anyone have convinced any of us a year ago of all the turns to come, of all the wrong directions or the way so many would stand up to demand the right ones? Maybe there’s never been any such thing as straight ahead.

During what turned out to be our last half-tank trip, Indie received an email from her university: she will have to quarantine for fourteen days in New York before arriving on campus. Driving west, we counted the days back from her move-in date and realized how soon we must leave.

In a few days, Indie and I will begin the cross-country trip on a road we’ve never traveled, the one that will separate us.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

This Is Not Beirut

Beirut sunset, with port in the distance (© Adobe Stock)

This is not Beirut.

But no—this is Beirut! A city broken and wounded, whose blood spreads like glass over the eyes. A city paved with glass, as though glass had turned into eyes, plucked out and filling the streets. In Beirut, you must tread on your eyes in order to see. And when you see, you are struck blind. A city of glassy blindness, of ammonium nitrate, and of the searing blast that swallowed the city and split the sea.

This is not Beirut.

For forty-five years we have been saying of Beirut that it is not Beirut. We lost Beirut while searching for it in the deficient past. “The City of Is-No-More”—that is the name we gave it, for, starting with the destruction of the civil war, we have attributed everything in Beirut to its past. This week, however, as we fell to the ground before the monster that exploded at the city’s port, we discovered that it was the destruction itself that was our city, these houses stripped naked were our houses, these groans were our groans.

This is Beirut! Everyone, tear your eyes away from the ground and behold your city reflected in these ruins! Stop searching for its deficient past! Do not stand and wonder, for the explosion that turned your city to rubble was neither coincidence nor mere accident. It was your truth that you have tried so long to hide. A city handed over to thieves to violate, a city where the authority of idiots holds sway and which has been ripped apart by warlords working for foreign powers.

A city that exploded because it lay prone on the bed of its drawn-out death agonies.

Don’t ask the city who killed it. Those who killed it were those who rule it. Beirut knows this, and all of you know it.

The killers of the city are the ones who tried to kill the 17 October Revolution by forming a government of technocratic puppets and who unleashed the dogs of repression on the streets.

The killers of the city are the communal party Mafias that took the country over and proclaimed the civil war ended by converting its menacing ghost into a political regime.

The killers of the city are the ones who elected Michel Aoun as president, converting the catastrophe created by oligarchy into farce.

Your city—our city—is dying. Twenty-seven hundred tons of ammonium nitrate, confiscated and placed in the port six years ago, exploded, and the flesh of its children was scattered. What monstrous nonchalance and stupidity!

In the past, the warlords of the civil war buried chemical wastes in our mountains. Today we discover that the nonchalance of these same warlords, who have transformed themselves into the Mafia bosses of this era that they declared to be that of “national peace,” has allowed Beirut to be smashed to pieces by something approaching an atomic bomb.

They sit on thrones fashioned from the bones of our dead, our poverty, and our hunger.

Hyenas! Are you not yet done with tearing our corpses apart?

Be gone! The time has come for you to be gone! Leave us be with our country that you have dragged into the abyss! Go to the Caribbean with its islands and its ocean, to which you have smuggled the people’s wealth and property so that you can live in luxury there!

Are you not yet done?

Your death knell has struck. Our death, and the torment in our hearts, have today become the weapon with which we shall face the coming days of darkness and humiliation.

We shall face you with our charred corpses and with our bleeding faces, and you will drown with us in the abyss of this destruction.

Listen well! Beirut has blown us apart to proclaim your demise, not ours.

Beirut is not its past. Beirut is its present. It bleeds blood, not honor. Stop talking! Shut up! Nothing you have to say concerns us. We want just one thing from you, to be gone.

Go—you, and the bankers, and everyone else who has gambled with our lives all the way to Hell!

Then we shall bind Beirut’s wounds. We shall tell our city that it will return to us, poor but joyful. Its soul shall be renewed, and, though weakened by its wounds, it will hold us tight to its pain and wipe away the tears from our eyes.

The time of the bastards who have ruled our lives for so long is over!

We don’t want your masters’ oil, we don’t believe your mullahs, and we don’t give a damn about your sects!

Take your sects with you and get out of our way!

The young women and men of the 17 October uprising must know that the time for total revolution has come.

Arise, and let us take vengeance for Beirut!

Arise, and build a homeland for yourselves from the ruins!

Arise, and redraw Beirut in the ink of its children’s blood!

—Translated by Humphrey Davies

Humphrey Davies received the 2010 Prize for Arabic Literary Translation for his translation of Elias Khoury’s Yalo. In addition to translating Khoury novels, Davies has also translated Naguib Mahfouz’s Thebes at War, Alaa al-Aswany’s The Yacoubian Building, and Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq’s Leg over Leg.

Elias Khoury was born in Beirut. His Gate of the Sun received the Palestian Prize and was named Best Book of the Year by Le Monde Diplomatique, the San Francisco Chronicle, and a Notable Book by the New York Times. Laila Lalami wrote in the Los Angeles Book Review: “the beautiful, resilient city of Beirut belongs to Khoury.” He encourages donations to the Lebanese Red Cross.

What Our Contributors Are Reading This Summer

Contributors from our Summer issue share their favorite recent finds.

Recently, I was inspired by the poet Solmaz Sharif to revisit June Jordan’s collection of essays, Civil Wars (1981). At a time when courting sickness and death is described by the president as “opening up,” or else framed as a concern about the education of children, when the attorney general defines peace as submission to police force, and when some voices, in the midst of a genuine emergency, are petulantly and nebulously complaining about “forces of illiberalism” and “cancel culture,” it’s been refreshing to revisit Jordan, who cuts through all the nonsense to show what is truly at stake with the politics of language and calls for polite civility. If you’re interested, maybe begin by checking out this excerpt from “White English/Black English: The Politics of Translation”:

They all—all them whitefolks ruling the country—they all talk that talk, that “standard (white) English. It is the language of the powerful. Language is political. That’s why you and me, my Brother and my Sister, that’s why we sposed to choke our natural self into the weird, lying, barbarous, unreal white speech and writing habits that the schools lay down like holy law…

See, the issue of white English is inseparable from the issues of mental health and bodily survival. If we succumb to phrases such as “winding down the war,” or if we accept “pacification” to mean the murdering of unarmed villagers, and “self-reliance” to mean bail money for Lockheed Corporation and bail money for the mis-managers of the Pennsylvania Railroad, on the one hand, but also, if we allow “self-reliance” to mean starvation and sickness and misery for poor families, for the aged, and for the permanently disabled/permanently discriminated against—then our mental health is seriously in peril: we have entered the world of doublespeak-bullshit, and our lives may soon be lost behind that entry.

Or maybe this, from the titular essay:

Most often, the people who can least afford to further efface and deny the truth of what they experience, the people whose very existence is most endangered and, therefore, most in need of vigilantly truthful affirmation, these are the people—the poor and the children—who are punished most severely for departures from the civilities that grease oppression.

If you make and keep my life horrible then, when I tell the truth, it will be a horrible truth; it will not sound good or look good or, God willing, feel good to you, either.

Still from video of performance Pajé Onça Hackeando a 33ª Bienal de Artes de São Paulo © Denilson Baniwa

Reaching for my mask along with the standard phone-wallet-keys when I venture out for groceries or remember that it’s healthy to go outside (mostly), I keep thinking of artist Denilson Baniwa’s series “Ritual Masks For a World In Crisis,” part of a quarantine-era commission of 125 artists by the Instituto Moreira Salles in Brazil, with an essay translated here by Tiffany Higgins. In these eight self-portraits, Baniwa mixes the surgical or hand-sewn pleated masks and bandannas that have become our new everyday around the world with woven crowns, feather headdresses, baskets, and jaguar heads that evoke Indigenous forms of protection and communication with the invisible world. These ritual masks are a way to negotiate with the God of Maladies, the code name he offers so as not to give away the Amazonian Baniwa people’s name for the spirit who takes the form of a sloth. The bright headdresses and face coverings with cheerful patterns like potted succulents and diamonds with stars morph from photo to photo, while Baniwa wears the same white T-shirt with his own silk-screened design, a stylized roaring jaguar with the words, “Floresta de pé, fascismo no chão,” a slogan seen and heard at Indigenous rights protests, which translates roughly to, “Up with the forest, down with the fascists.” Some of the headdresses trade the usual feathers and thread for electrical wire and the jagged teeth of long, thin hacksaw blades broken in pieces to form crowns and a halo. These unexpected juxtapositions shape the playful, absurdist, and activist tone of Baniwa’s work, which mixes memories of his people’s traditions from the Rio Negro region of the northwestern Amazon with the modern-day artifacts and practices of an artist based in Rio de Janeiro. Before the pandemic, Baniwa walked the streets and museums of São Paulo and sites like the Biennale of Sydney with a mask and cape as the Pajé Onça, a powerful shaman who takes the form of the spotted jaguar, a figure that appears throughout Baniwa’s street murals, wheat-paste posters, museum installations, and performances, displayed on his site and on Instagram. COVID-19 has hit communities in the Amazon especially hard, with the widespread loss of loved ones, elders, artists, healers, and shamans, like Feliciano Lana, the Desana artist whom Baniwa cites as a major influence, and Vó Bernaldina, a spiritual and political leader of the Macuxi people. For Baniwa, it brings up memories of plagues brought by past colonizers, and the ways Indigenous people had to update their sacred rituals to include vaccines, antibiotics, and other medicines that intervened with the unseen world. The present mask and hand-washing rituals are yet another update. He writes, “May the God of Maladies see that we are fulfilling all the rituals, and soon be soothed. May our people survive this, one more end of the world.” —Katrina Dodson

These days I have been enfolded in Adeeba Talukder’s beautiful collection of poems, Shahr-e-Jaanaan, City of the Beloved. Like a graceful arabesque the collection soars into Urdu poetry and swerves back into English. Lines like these leave me breathless: “Longing, air spent / travels the length of age, then receives / a faint reply: / You have a conquered a curl, at last.” Talukder’s poetry captures the exquisite pain of the lover; the Urdu ghazal glimmers behind the English and invites me to dwell in both worlds. Walking alone in empty streets, I’m drawn to her contemplations on loneliness and companionship, “Come walk with me / by the lake’s empty benches. / Tell me, dressed in roses / we need some air.” Her collection of poems has been my companion and my lover, the one I reach out to when I need a place to breathe. — Krupa Shandilya

Possibly out of a desire (or need) to escape the modern, COVID-ridden world, I’ve been revisiting Jane Austen. With no happy ending to our current situation in sight, I’ve found her novels enormously reassuring, knowing that everything will come right and love will triumph. I’ve also been luxuriating in her prose, so witty and so wise, and taking particular pleasure in the most awful of her characters: the vain, snobbish Sir Walter Elliott, the splendidly egomaniacal Mrs. Elton, and, of course, the obsequious Mr. Collins. There is something so delicious and, yes, so unflinching, about her depiction of these fools, and I found myself wishing she were alive today to sharpen her quill on some of our present-day and all-too-present imbeciles. A thought to savor. And which novel to choose as a starting point? For no particular reason, I started with her last novel, Persuasion, and ended with her first, Northanger Abbey, as if reading her work on rewind, from the more sober tale of twenty-seven-year-old Anne Elliott reencountering a lost love to seventeen-year-old Catherine Morland discovering love for the very first time. And not a mention of viruses.

And still safely in the past, but at least in the twentieth century, I’ve been watching the thirties Marseilles Trilogy based on the plays by Marcel Pagnol. Many of the actors had already appeared in the plays on stage, which gives the movie a real ensemble feel. Just superb. —Margaret Jull Costa

There were two problems with the Great War’s dead on the Western Front: how to handle the bodies and how to handle the absence of bodies. The number of Great War dead was so enormous that a decision was made to bury them where they had fallen. Families could not bring their soldier home. The Imperial, and now Commonwealth, War Graves Commission, was founded in 1917 to locate and record the last resting places of fallen soldiers. After the Armistice, it cleared the battlefields of the dead and designed and built hundreds of cemeteries and memorials. By 1921 records indicated that hundreds of thousands of bodies were still missing—drowned in mud or vaporized by artillery shells. These missing continue to haunt families, historians, and, for some reason I don’t fully understand, me. They lie at the center of my recently published long poem, Salient. Every year some emerge, one by one or in small clusters, when a new building needs a foundation or a highway needs a new off-ramp.

In 2008 hundreds of them, mostly Australian, were found in mass graves just south of Pheasant Wood near Fromelles, France. The fierce fighting at Fromelles on July 19–20, 1916, was just a sideshow in the Battle of the Somme. But for the efforts of a retired and persistent Australian schoolteacher, clear documentation of these graves would have remained lost in German and British archives. Hundreds is a big number. For the first time in decades the CWGC had to build a whole new cemetery. How could no one have found these men for ninety years?

In support of my disbelief, I offer you the British trench map below, from late July 1916. I have marked the location of the graves:

The graves are located at 36 SW 2 Radingham N.17.c.3.1 on British trench maps of the time.

Maps were constantly updated from intelligence reports. Doubtless the map revision had been based on aerial photos like this one, below, from September 1916, showing that five of the eight large pits have been filled in:

The Lost Legions of Fromelles is Peter Barton’s highly granular answer to my question and reads like a detective thriller filled with courage, tragedy, politics, good intentions, prisoners, spies, and evidence hidden or overlooked, all in the context of unimaginable and now invisible carnage. Barton also includes a gripping description of the July 1916 battle, and its predecessor of 1915, pushing back against parts of the classic Australian narrative using German sources. Fromelles was a catastrophic defeat, seared, like Gallipoli, into Australia’s psyche. Now we have a clearer picture of what happened, and, in 2010, two hundred and fifty of the men who went missing at Fromelles were interred with full military honors. Through DNA tracing, many families have been reconnected with a grandfather or great uncle. There are still another fourteen hundred men missing on that ground. The Fromelles Project continues its work. — Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.

Can I recommend my friend, Bill, the Shakespeare professor from Chicago? Two years ago he came to Jersey City to see his new granddaughter. Afterward I met him over at the piers. “What’s new, Bud?” he asked. For half an hour, I told Bill some lame bullshit about my construction job and he kept laughing and slapping his knee. Finally I said, “What’s new with you, Bill?” He looked at me seriously, “I had a stroke.” He’d collapsed in his kitchen three weeks before, couldn’t reach the phone and his wife had just left in the car. So Bill made peace with death. Luckily his wife had forgotten the grocery list and she came back and found Bill on the floor and called an ambulance and he got to the hospital and made a complete recovery. Thank God. On the piers that day Bill then gave me a literary intervention. Drop everything, read Don Quixote, and Madame Bovary, and all of Virginia Woolf and on and on. “You can’t just read junk food, Bud. You have to read the best to see where the ceiling is.” Since it sounded like the man’s dying wish, I lied and said I would read these “better” books. Well, the next month he called my bluff and I received a huge box in the mail, random classic paperbacks, marked up and dog-eared. Thanks Bill, I loved the books so much I’m recommending everyone who reads The Paris Review should become your pal. Recently, I made the mistake of posting a picture of a Nabokov novel I liked (which Bill hadn’t recommended, by the way). He commented, “LIFE IS TOO SHORT FOR BAD BOOKS!” Maybe it used to be, but now we’re in a pandemic. There’s nothing but time. Last month I binged six whole seasons of Columbo (my favorite show) starring Peter Falk (my favorite actor). Bill saw one of my social media posts about that and commented I should read Crime and Punishment. “Go right to the source!” Shit, why did the source have to be a doorstop Russian novel? Anyway, I read it and loved it. Turns out Columbo is a thousand percent based on Crime and Punishment. It’s structured just like the novel, and inspector Porfiry Petrovich is the nearly same character famously played by Falk, right down to the mannerisms and the way he antagonizes the murderer. Just amazing. Thanks again, Bill. Hope you’re doing good today. Miss ya, man.

But Bud, wait, what are you recommending? Be more specific, please.

Hey! Start with these these five episodes of Columbo—“Suitable for Framing” (1971); “The Bye-Bye Sky High IQ Murder Case” (1977); “Étude in Black” (1972); “A Stitch in Crime” (1973); “The Most Crucial Game,” (1972) and then read Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. —Bud Smith

Installation view, Why Is It Hard to Love?

What I would like to recommend is what most of you will not see. Vilnius has a new museum for contemporary art: MO, the brainchild of Danguolė and Viktoras Butkus, scientists turned art collectors. The building was designed by Daniel Libeskind, opened in 2018, and the collection is devoted to contemporary Lithuanian art. Located in the center of the city, on the edge of Old Town, the building has a bright white edifice that juts like the prow of a ship over Embankment Street (as Robert Hass translated the name of Pylimo Street in Czesław Miłosz’s poetry, so I leave the literary connection). Underneath this majestic bow, a staircase climbs to an amphitheater that hosts regular readings of contemporary Lithuanian poetry. There is a sculpture garden to the side, providing pleasant green space. The present exhibition (on view into January 2021) is the first curated by international artistic celebrities: the British filmmaker, Peter Greenaway, and his wife, the Dutch artist, Saskia Boddeke. They have created an immersive experience in the third-floor primary exhibition hall where the sound and lighting effects spill out from their two video installations and envelop the selection of paintings branching through the space, all to the theme of Why Is It Hard to Love? The visitor turning from the winding stairs is greeted by the two showstoppers: Monika Furmana’s three-meter-high painting in oil and spray paint, The Tree of Life, and then, through a dark cleft, the curators’ video installation, Number 34 is Missing!, replete with dark reflecting pool and stacked chairs arcing through the air. (A limited look at various pieces is available here.) The exhibit answers “Why is it hard to love?” in many different ways, with alienation, inequalities, social differences, and prejudices all having their say, and yet, as those first pieces make clear, the struggle to love is also a path to both self-discovery and greater meaning. You would do well to have MO Museum on your itinerary when you are able to visit Vilnius. —Rimas Uzgiris

Explore the contents of our summer issue, and consider subscribing to The Paris Review

August 6, 2020

Rapunzel, Draft One Thousand

Sabrina Orah Mark’s column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

Photo © Sabrina Orah Mark

I call the Wig Man. He picks up. “My sister,” I say, “was diagnosed …” He interrupts me because he is driving and he is in a rush. “My store,” he says, “was looted last night.” “My sister,” I want to say, “…” He tells me he gathered all the hair that was left on the floor. “Glass everywhere,” he says. “I filled my Toyota Tacoma with all the hair that was left. I am driving home now,” he says. “Is you sister’s hair long?” he asks. It is. It is very long. “Because if it’s long what your sister should do before treatment begins is cut all her hair off and I will sew it, strand by strand, into a soft net. It’s called a halo,” he says. “I want to help your sister,” says the Wig Man. I imagine his Toyota Tacoma so stuffed with wigs that black and brown and blond hairs press up against the windows. Like animals trapped inside their own freedom. He starts to cry. I am certain he is driving across a bridge. “I don’t know how much more of this I can take,” he says.

“Neither do I,” I don’t say.

Sewing a wig strand by strand is called ventilating. I watch a tutorial. With a needle you draw each strand through a lace net and knot it on itself. The needle goes in and then out like thousands of tiny breaths. Ventilating a wig takes the patience of the dead. Each knotted strand is like a person sewn into a free country. The knot is tight, and the net is manufactured. “Of course my life matters,” says Eli my six-year-old. “Why wouldn’t it matter?”

My sister decides not to cut her hair. Instead she lets it fall out, slowly and then suddenly. She yawns, rises, and climbs up the stairs. She leaves behind a trail of blondish gold thread, like a princess coming undone. I write six different essays on Rapunzel. All of them are terrible. I help my sister into bed, though she prefers I not touch her. On her nightstand are six glittering tiaras. She wears one to chemo. Another to breakfast. “Isn’t it strange,” I say, “that I write about fairy tales and you are a fairy tale princess?” She looks at me hard. “A sick princess,” she says.

Of all the fairy tales, Rapunzel gives me the most difficult time. “It’s because,” says my husband, “you are trying to use her to write about systemic racism, and protest, and cancer, and a global pandemic.” “Should I just take out the racism?” I ask. “No,” he says. “You can’t take out the racism.” “I know,” I say. “That was a stupid question,” I say. “Can I take out my mother?” “Does your mother appear?” he asks. “I don’t remember your mother appearing.” “Eventually,” I say, “my mother always appears.”

I am following my husband around the kitchen. “Should I add how after George Floyd was killed you sat on the edge of the bathtub and cried? Remember how you said,” I say, “‘We’ve been here before’? Remember when you said, ‘When will this stop,’ but you said it like an answer not a question?”

“Thugs,” says the Wig Man. “They destroyed my shop,” he says. “Everything is ruined.” I never call the Wig Man back. Instead, my mother buys my sister four wigs made out of strangers’ hair. Two brown ones, and two blond. My sister refuses to try the wigs on so my mother tries them on instead. In the wigs my mother looks sad and incredibly young. I can see my sister’s face gazing out from inside my mother’s, like a girl locked inside a tower.

My husband sits on the edge of the bathtub and cries. “We’ve been here before so many times,” he says. “When will it stop?” he says. “I don’t know how much more of this I can take,” says the Wig Man. “Of course my life matters,” says Eli, “why wouldn’t it matter?” “Did you know,” says my sister, “that in Disney’s Tangled Rapunzel lives inside a kingdom called Corona?” “That can’t be right,” I say.

I cut off all my hair. A twelve-inch braid long enough for nobody to climb. I throw the braid in the trash and then remove it from the trash. It’s soft and dumb. “I can’t look at it,” says my mother. “Get it away from me,” says my sister. I put it in an envelope and send it to a dear friend’s brother, an artist who makes Torahs and animals and money out of human hair and skin. I mean it as an act of solidarity, but I get the feeling my sister and mother read it as an act of pointless sacrifice. To punish Rapunzel for betraying her captivity, the enchantress winds her braids around her left hand, cuts them off, then takes Rapunzel to a wilderness and leaves her there. “See,” I say to my sister. “It’s not so bad.” She looks at my short hair, and a small forest grows between us.

Other than Disney’s, in no version of Rapunzel is Rapunzel’s hair magical. It can’t bring back the dead, or heal a broken bone, or keep a woman young forever. It can’t light up dark water. It can’t be thrown like a lasso so Rapunzel can glide from mountaintop to mountaintop. It doesn’t, like his hair does for Samson, give her god’s power or the strength to kill a lion with her bare hands. It cannot keep a man from being shot for his blackness. It’s just hair.

“I’m sure Rapunzel is wonderful and not terrible,” emails a friend, “but also there’s something Sisyphean about Rapunzel …” She’s right. I know what she means. Rapunzel’s hair is no more magical than a mountain the enchantress climbs day after day, pushing the burden of her own spell. I know what she means, but now I am imagining rolling boulders up Rapunzel’s back as she bends down to pick the roots and berries she survives on while pregnant in the wilderness. I roll the boulder up Rapunzel’s back, and each time I reach the crest the boulder rolls back down. Rapunzel, the mountain. Rapunzel, my sister. I am using my sister’s cancer to write about the impossible because it’s impossible my sister has cancer. And it’s impossible my sons cannot go to school or play with their friends. And it’s impossible my husband could be shot for being black. And it’s impossible the air is filled with tear gas and viral particles. I have stolen my sister’s tiara to wear. I am covered in sweat and dust, and on my head the tiara is crooked. I stole the most beautiful one. I stole the one embellished with glass stones and little pink stars.

It is late afternoon and my sister is sleeping. In the dining room, my mother has lined up all the wigs on their Styrofoam heads. Like four extra daughters. She keeps walking by them and smoothing their hair with her hand. She puts one to her face and inhales. The afternoon light lengthens her shadow. I don’t know if she notices I am there. The story of Rapunzel begins with a pregnant woman’s insatiability, her hunger for the finest rapunzel (also known as rampion, or the “king’s cure-all”) that results in the barter and entrapment of her daughter. In Giambattista Basile’s “Petrosinella,” one of the earliest versions of the story, a pregnant woman is caught stealing parsley from an ogress’s garden. She apologizes, and explains she had to satisfy her craving. In the sixteenth century, there was a widespread belief that if a pregnant woman’s cravings weren’t satisfied, the shape of whatever she craved would appear on her newborn. Birthmarks are called voglie in Italian, which means longings. My sister and I have identical birthmarks on the right side of our faces. Near our ears. Like a handful of scattered acorns. I am twenty-five years older than my sister. We don’t have the same father, but we do have the same mark of our mother’s longing.

Every two weeks my mother takes my sister to be infused with poison through a hole in her neck so she doesn’t die. My mother looks over at me. I am writing a birthday card with butterflies on it. “I hate butterflies,” says my mother. “It’s a stupid thing to put on a birthday card. They’re barely alive and then they’re dead.” Every mother has the exact same single greatest fear. It’s the boulder we push while praying for no crest.

“Of course my life matters,” says Eli, my seven-year-old. “Why wouldn’t it matter?”

By now the Wig Man must have stopped crying and arrived home. I imagine he is working in the same afternoon light that comes in through my mother’s window. He is bent over as he sews each of us, like strands of hair, into a soft net. Listen, we are breathing. You are breathing. My sons and husband are breathing. The Wig Man sews and sews. One piece of glass is still caught in a strand but he doesn’t notice it yet. My mother is breathing. My sister is breathing. We will make a magnificent wig. Rapunzel will wear us in this lost version of her fairy tale. We are not magical, but at least we are alive. “Rapunzel, Rapunzel, / Let your hair down.” When she lets us down what will climb up? We have one last chance to answer right. A revolution or the enchantress who keeps us?

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

August 5, 2020

Poets on Couches: Reading Max Jacob

In this series of videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“Ravignan Street”

by Max Jacob, translated by Elizabeth Bishop

Issue no. 226 (Fall 2018)

“One never bathes twice in the same stream,” the philosopher Heraclitus used to say. However, the same people always turn up again! They go by, at the same time, gay or sad. You, passers-by in Ravignan Street, I have given you the names of Historical Defuncts! Here’s Agamemnon! Here’s Madame Hanska! Ulysses is a milkman! Patrocles is at the foot of the street while a Pharaoh is near me. Castor and Pollux are the ladies on the sixth floor. But you, old rag-picker, you who, in the enchanted morning, come to get the garbage, the garbage which is still fresh when I put out my nice big lamp, you whom I do not know, poor and mysterious rag-picker, you, rag-picker, I have named you a noble and celebrated name. I have named you Dostoyevsky.

Srikanth Reddy’s latest book of poetry, Underworld Lit, will be published by Wave Books in August 2020. He is a Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Chicago.

Suzanne Buffam is the author of three books of poetry, the most recent of which is A Pillow Book (Canarium, 2016). She teaches at the University of Chicago.

Jean-Patrick Manchette’s Cabinet of Wonders

Jean-Patrick Manchette, 1967.

They were nearly all Islanders in the Pequod, Isolatoes too, I call such, not acknowledging the common continent of men, but each Isolato living on a separate continent of his own.

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Herman Melville called them isolatoes—the word he coined for those among us who don’t have much truck with fellow humans. The bonds of society, except in odd and extenuating circumstances, are not really for them. Love, marriage, family seem as strange, distant institutions, things one might observe with a notebook in the other hand. At best, there are a couple of old comrades accumulated on life’s journey to whom one might turn when things go south. For isolatoes, the most constant of companions are those voices inside the head.

Jean-Patrick Manchette’s protagonists are isolatoes. Georges Gerfault in Three to Kill, Julie Ballanger in The Mad and the Bad, Martin Terrier in The Prone Gunman, Aimée Joubert in Fatale: windowless monads, all of them. Memorable, violent, alone.

Eugène Tarpon, Manchette’s private eye in No Room at the Morgue, is among these nations of one. Like many fictional private eyes he’s come to the end of his rope; in fact, as the novel begins, he’s already thrown his badge in the river. Only an unlikely client—is there any other kind?—coming through the door puts his retirement plans on ice.

You perhaps know (and Manchette certainly knew) Dashiell Hammett’s Flitcraft story, an existential parable embedded within The Maltese Falcon. It contains the sentence “He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.” In No Room at the Morgue it goes the other way: As we meet him, Tarpon has submitted to a certain quiescence. He has adjusted himself to a life where beams no longer fall. And then one does. Providing him with a headache, us with a narrative.

*

As is so often the case with Manchette, the shadow of May ’68 hovers over all, much as the shadow of the Occupation hovers over the novels of Patrick Modiano. It’s what our Lacanian friends would call “the structuring absence.” The France of Eugène Tarpon is littered with the debris of failed revolt. If those who make half a revolution only dig their own graves, Tarpon’s journey is a slow stumble across that graveyard: his Paris is a Père Lachaise of the soul.

Yet Tarpon is no soixante-huitard; rather, he’s a retired (or cashiered) gendarme who killed a militant during a protest (imagine a Sam Spade who, like Hammett, had previously worked as a Pinkerton but, unlike Hammett, had also been a strikebreaker). When we meet him in the “fifth floor, no elevator” flat near Les Halles that serves as his home, his office, his life, he’s drinking pastis straight, his bank account has cratered, he’s within twenty-four hours of going home to Mom in the provinces. The adventure/misadventure into which he is then swirled—with about the same degree of agency here as Dorothy when a twister swept her to Oz—takes him to that most Manchettian of locales, an abandoned house in the country, where pro-Palestinian rebrands and American mobsters clash by night. Tarpon’s attitude toward the former mirrors Manchette’s own—as he wrote in his diary, “the collapse of leftism into terrorism is the collapse of the revolution into spectacle.”

From the carnage of the countryside, Tarpon makes his bloodied way back to Paris—to what might nominally be called civilization—only to be followed, abducted, drugged, shot at, and stabbed by a farrago of gangsters, pornographers, miscreants, sociopaths, and killers. In this upside-down world, the nice guys turn out to be the cops. They don’t beat you up unless there’s a reason for them to do so.

For all of the gimlet-eyed precision with which Manchette observes human activity in the post-’68 landscape, he always gives us a character or two who behave well, and with empathy for their fellow beings. In Three to Kill it was Raguse, the kindly alpine recluse who takes in our protagonist. In No Room at the Morgue it’s the journalist Haymann, who helps Tarpon when he doesn’t really have to, and the upstairs neighbor, the elderly tailor Stanislavski, who has never harmed a soul, and suffers the consequences. Manchette uses these figures to cast in high relief the bad faith and worse behavior of the rest of us, caught in the convulsions of late, or one may say after-hours, capitalism.

The language he uses to depict these convulsions only heightens the terror and the absurdity—André Breton would surely recognize in Manchette a fellow practitioner of humeur noire. As Tarpon narrates, “I was making up theories in my head: Was Haymann an Israeli agent? And was it in fact Memphis Charles they’d tried to assassinate the other night? My theories were collapsing one by one, but I started constructing them all over again. At the same time, I was dreaming of steak frites. And it was getting mixed up in my theories. Béarnaise sauce was dripping down the faces of Palestinians. In my head, I mean. In my head.” Or, more offhandedly: “Memphis Charles had dragged the American who was still alive into the workshop and she was attaching him to the pipes. Life goes on, like the song says.”

Still, from time to time—and this is what makes No Room at the Morgue so poignant—we’re also allowed a window into the heart, an access given legitimacy by the fact that it occurs so rarely and against a landscape so invariably gray. Here we have a mobster who inexplicably breaks down in tears. We don’t understand it but are moved. And then, later, we do understand it and are moved yet more deeply. For Manchette, these moments of fragility, of tenderness, aren’t moments of weakness. But they’re not moments of strength, either.

*