The Paris Review's Blog, page 152

August 17, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 22

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“August is Women in Translation Month, an annual celebration centered around the #WiTMonth hashtag and started by the book blogger Meytal Radzinski in 2014. Though it’s worth reading literature in translation year-round, August provides an opportunity to shine a spotlight on this work. Even as the coronavirus pandemic puts new distances between people, travel to other places, other periods, and other perspectives is possible via literature. To read a book is to play a trick on space and time; though I may be physically sitting in the same small bedroom where I’ve spent most of my time since March, I am actually anywhere but. And so to celebrate Women in Translation Month, this week’s The Art of Distance lifts the paywall on works of or about translation. Happy reading, happy travels, and stay safe.” —Rhian Sasseen, Engagement Editor

Margaret Jull Costa. Photo: © Gary Doak / Alamy Stock Photo.

This Women in Translation Month archive dive begins with Margaret Jull Costa’s Writers at Work interview, The Art of Translation No. 7. Jull Costa is a legend in the world of translation, having brought work by Fernando Pessoa, José Saramago, Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis, Luisa Valenzuela, and more into English. As she tells interviewer Katrina Dodson, “I think translating is just what I do. I miss it terribly if we go on holiday, and sometimes take some editing with me as my security blanket. So I suppose I’m a translation addict. There are worse things.” (If you’d like to learn more about the process behind this interview, Dodson will be joining us for a live conversation on The Paris Review’s Instagram on Thursday, August 20, at 7 P.M. EST.)

I’ve always appreciated the ways literature in translation encourages me to interrogate my relationship with my native language. As the man at the center of the Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann’s short story “Everything,” translated by Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser, realizes: “It’s all a question of language, and not merely of this particular language of ours, which was created with all the other languages at the Tower of Babel in order to bring confusion into the world. For under them all there’s another language smouldering away.”

There’s also the history that language carries, as the Egyptian poet Iman Mersal writes in “A Celebration,” translated by Robyn Creswell: “Celebration. As if I’d never said the word before. As if it came from a Greek lexicon in which the victorious Spartans march home with Persian blood still wet on their spears and shields.”

Language plays tricks on the reader, too, as it does in the Japanese writer Hiromi Kawakami’s short story “Mogera Wogura,” translated by Michael Emmerich. “Let me tell you about my mornings,” begins the narrator, regaling us with the details of an ordinary day before the twist is revealed: “The humans I’ve collected are in the next room.”

“Once I have the reader’s attention I feel it is my right to pull in whichever direction I choose,” the Italian writer Elena Ferrante argues in her Art of Fiction interview. “I don’t think the reader should be indulged as a consumer, because he isn’t one. Literature that indulges the tastes of the reader is a degraded literature. My goal is to disappoint the usual expectations and inspire new ones.”

New expectations are certainly inspired by reading these two poems by the Brazilian writer Adélia Prado, translated by Ellen Watson, both new looks at colors. “The sky purples morning and evening,” Prado writes in “Purple,” “a red rose growing older.”

Finally, why not pop over to the Daily and read Jennifer Croft’s essay “The Nobel Prize Was Made for Olga Tokarczuk”? Croft, the translator of Tokarczuk’s novel Flights, which won the Man Booker International Prize, joined us on The Paris Review’s Instagram earlier this month to discuss her work translating from Polish and Spanish, her own writing, and why translation is like swimming.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

Oranges Are Orange, Salmon Are Salmon

Luis Egidio Meléndez, Still Life with Salmon, Lemon and Three Vessels, 1772, oil on canvas, 16 x 24 1/2″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Oranges require orange to be. They are a color expectation. If an orange is not orange, it is no orange.

Oranges originated in China, where they were crossbred from a mandarin and a pomelo as early as 314 B.C. From there, oranges passed from Sanskrit नारङ्ग (nāran˙ga) through Persian نارنگ (nārang) and its Arabic derivative نارنج (nāranj). Traveling to continental Europe with the Moors, naranjas soon dotted al-Andalus and Sicily. Oranges arrived in England from France in the fourteenth century, their bright skins holding a taste of a color that became popular in markets, on palates, and, eventually, in tongue.

For centuries, oranges were orange and, still, orange was not a color—it was called yellow-red. It took another two hundred years for the color to earn its name, to become a form that could give itself to others—to be ascribed to flowers, stones, minerals, and the setting sun.

To the west, oranges followed the path of Spanish missionaries and lent their name to Orange County and the Orange State. In California, the fruit fed the miners of the gold rush who passed through mission towns. In Florida, there were so many groves that, by 1893, the state was producing five million boxes of fruit each year. In this tropical climate—nights too humid and too hot—oranges would ripen too quickly: they were ready to be eaten while still green. And so, from the twentieth century onward, green oranges have been synthetically dyed orange, coated to match consumer expectations. Orange reveals that humans cannot imagine a species detached from its color, even when we are the ones who detach it.

Amid all the observations that are made about industrialization and its consequences, the following is rarely heard: the world’s colors are shifting. From infancy, we describe, dream, and remember predominantly with our sense of sight, and there is no seeing without exploring, no static vision. We are raised to bend color to our will, at times admonishing it and elsewhere applying it to our liking. We grow up coloring in pictures of the world—trees are green, earth brown, and yolks yellow. That everything else in life is turned regularly upside down is only tolerable because oranges remain orange and the sky blue. An increasing amount of industrial energy is directed, therefore, toward dyeing the world in natural colors so that life and commerce may proceed.

But dyes may miss their mark. Shifting cues in flesh, scales, skin, leaves, wings, and feathers are clues to the environmental and metabolic metamorphoses around and inside us. The force that is color is not for domestication; it is fugitive. Color colors outside our lines.

*

In 2018, an eye-catching sparrow was spotted on the Isle of Skye. The sparrow was bright pink.

We know what sparrows are supposed to look like, because they have evolved with us. Over several millennia, food scraps from human settlements attracted sparrows from the “wild,” which caused them to mutate into a new species. “House” sparrows have since become a familiar sight wherever humans dwell, metabolizing the shades of our settlements into their brown-gray feathers. They are drabber than their older, tree sparrow cousins, who preserve the brighter tones of the forest.

The pink sparrow, neither forest nor house, was a color leak. The sparrow had turned [salmon].

On the Isle of Skye—whose name comes from the Gaelic for “winged”—colorful feathers lure eyes. Anglers, fishing for sport, carefully tie fish flies from synthetic rainbow plumage that resembles insects, enticing salmon. These iridescent wings are easy prey. Salmon bite on the colors that they find attractive, only to swallow a deadly hook.

In the nineteenth century, colonists in the tropics were drawn to exotic birds and sent them back to Britain. These startling hues and patterns inspired new recipes for salmon flies, and plucked feathers, far from their origins, were used to pluck salmon from their natal streams. A combination of toucans, peacocks, and macaws, the flies mimicked salmons’ cravings. Hued plumage was used to deceive: to confuse the edible and the deadly. Salmon, beings for whom the ingestion of color is essential, took the bait.

Salmon are at home in color. Whipping her tail, a female salmon spends two days making a depression in the riverbed called a redd—the word probably comes from the Early Scots ridden, meaning “to clear”—into which she deposits her roe. Fertilized, these red spheres of nutrients encase young salmon, who eat their way out, taking the color inside. Once the eggs are depleted, salmon swim to the ocean in search of food. There, they feed on red-pink crustaceans, mostly shrimp and krill, as well as small fish with even smaller crustaceans in their digestive systems. From these, they absorb yellow-red orange fat-soluble pigments, called carotenoids, that tint salmon salmon.

Crustaceans swimming at 63°29’19.8″ N, 10°21’55.7″ E might be redder than those at 56°52’01.7″ N, 6°51’00.6″ W, but pinker than those at 56°41’24.9″ N, 175°58’53.5″ W. Salmon record their location by metabolizing these shades—their flesh is color-coordinated. If salmon could peer inside their own bodies, they could distinguish, from their muscle tones, the Trondheim Fjord from the waters of Skye or the Bering Sea.

When salmon are ready to breed, they stop eating. Their stomachs shrink to the size of an olive, to make room for roe and milt, and they are drawn back to their birthplace, searching for home against the current. They follow what scientists suspect to be inherited maps encoded in their DNA, tracing chemical pathways and geomagnetic fields, which can lead them on journeys of more than three thousand kilometers.

Upon reaching fresh water, which bears murky river silt, salmon retinas trigger a biochemical switch that lets them see in infrared for clarity. Changes in sea temperature and water composition, in turn, activate memories of their original stream. Their senses act like a compass—not to determine the location of home, but rather the direction toward homecoming. Olfactory imprints allow salmon to swim through a smell-bank in their brain—what humans would think of as “remembering.” For salmon, this is perhaps not an active decision; it is an urge to return, to retrace innate memories homeward, extending to the moment of their birth.

The swim upstream requires such great exertion that it pushes red pigment to the surface of a salmon’s skin—a sign of health that lures mates. Female salmon pass on carotenoids in their flesh, to plump their roe and make it attractive to prospective males. Color streams through generations, linking salmon to their redd. Salmon color is the pathway—metabolic and geographic—of being; it is the atmosphere in which salmon are born and what they advertise when they spawn and die. Color in this cosmos, then, is more than cosmetic—it is a biological influence as strong as memory.

Salmon are a means by which color moves according to a logic of ingestion: salmon metabolize their color, drawing life from it, and humans, craving this color species, consume an image of health.

*

Such is the human thought of salmon: scales encasing ink-perfect pink flesh, a river leaping with fish on the run. A color bound to a body, a body bound to its own name.

On Skye, however, this pictorial logic is fading. Skye no longer runs salmon: populations have fallen to historic lows and corporate aquaculture has filled the waters around the island with intensive open-net salmon farms. Salmon—the color and the fish—is a red herring.

Open-net fish farms are flow-through feedlots, packed to the gills. Enclosed in pens with one to two hundred thousand other fish, a salmon cannot feed on krill and shrimp. Here, a salmon is naturally deprived of astaxanthin, the carotenoid that makes crustaceans pink and that protects a salmon’s body from solar radiation and stress. A salmon’s color reflects its well-being: darker pink salmon represents access to astaxanthin-rich crustaceans, whereas pale pink salmon represents a lack of nutrients or high stress levels. Farmed salmon, lacking these resources, are no longer truly salmon. Their flesh tone is now closer to white-gray than red. Salmon, the fish, are cleared of salmon, the color. Once they are gray, they are [salmon].

Cooking Sections—Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe—is a duo of spatial practitioners. Since 2015, they have been working on multiple iterations of the long-term site-specific CLIMAVORE project, exploring how to eat as humans change climates. They currently lead a studio unit at the Royal College of Art, London. In 2019, they were awarded the Future Generation Special Art Prize. Daniel is the 2020 recipient of the Harvard GSD Wheelwright Prize for the research project “Being Shellfish.”

From Salmon: A Red Herring, by Cooking Sections. Salmon: A Red Herring is the first work in isolarii, a series of “island books” released every two months by subscription.

August 14, 2020

Staff Picks: Girlfriends, Grenades, and Godheads

Steven Garza in Boys State. Still courtesy of Apple TV+.

What I remember most about being seventeen is how infallible I felt, how naively but deliriously hopeful. So it didn’t surprise me, watching the documentary Boys State, that a group of a thousand seventeen-year-old boys imitating a political election would devolve into a raucous theater of ego. The film follows the 2018 Texas Boys State convention, a weeklong summer camp held every year in every state by the American Legion, and primarily documents the race for the coveted office of governor. Boys State won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, but still, I think I expected shallower thrills. I thought I knew how it would end—who would be the hero, the villain, the winner, the loser. But though it could have said something easy to believe about politics, something easy to believe about boys, the film provides more nuance. It offers a complex interpretation, something frightening but almost forgiving, of being seventeen. Even at the heights of the rampant manipulation and self-aggrandizing enacted by the boys (of which there is so much), every interaction feels like an attempt to be liked and to feel alike. “I thought if I played to that, then they’d love it,” one of them says when his misjudgment of his peers costs him an election. And while I could have told him that trying to read the minds of teenage boys is an effort destined to fail, the best moments are when the godheads come loose. The more heartbreaking moments are when, for some, their ego is only affirmed. Real life, I was reminded, is not a bildungsroman. But I am now barely the person I was when I was seventeen, and 2020 feels eons away from 2018, when the film takes place. These boys could be anyone now. Then again, they could also be exactly the same. —Langa Chinyoka

The poems in Grenade in Mouth: Some Poems of Miyó Vestrini span the years 1960 to 1990 and serve as an introduction to the work of the Venezuelan avant-garde poet Miyó Vestrini for Anglophone readers like myself. Translated from the Spanish by Anne Boyer and Cassandra Gillig and selected by Faride Mereb and Elisa Maggi, these are poems that smash, that break, that throw themselves at the reader without apology and stay lodged in the brain long after the experience of reading is over. They cover death, suicide, love, and political repression. “Give me, lord, / an angry death,” begins “Brave Citizen.” “A death as offensive / as those I’ve offended.” “Sure, it’s beautiful to re-read,” goes a part in “The Smell, the Street, & the Sorrow.” “But somebody wrote it and that somebody was you. Fuck women’s poetry and the two days of labor that serve to help you scripturally weep … You are a poet and you don’t ejaculate. Something that is an unforgivable fault.” Vestrini’s own suicide, too, hangs over the work, such as in “Grated Carrot” (“The first suicide is unique”). In a brief note on translation included near the beginning of the volume, Vestrini writes, “We must admit that all of civilization depends on translation.” To that point, I find myself grateful for this translation for introducing me to a writer whose uncompromising radicalism feels like a necessary slap to the face. —Rhian Sasseen

Still from Claudia Weill’s Girlfriends, 1978.

It has come to my attention that Claudia Weill’s 1978 masterpiece Girlfriends is now available to stream. After years of demanding that everyone I know find and watch it (particularly if they mention Frances Ha, a film I enjoy as a sort of remake of or homage to Weill’s), I am now duty-bound to demand that you, readers of The Paris Review’s staff picks, watch it! Susan (Melanie Mayron) and Anne (Anita Skinner) are two bosom buddies sharing a Manhattan apartment and making art, and then Anne has the gall to desert for a man and a country house. Both women suffer, but the film sticks closer to Susan. Even in the seventies, it’s tough to pay the bills with just one artist’s “salary.” My favorite scene: After accepting yet another wedding photography gig in order to pay her overdue electric bill, she picks up the phone, pulls a Hershey’s bar from the nearly empty fridge, and, with no one on the other end, starts talking in a tone of weary entitlement about an imaginary upcoming assignment from Vogue. It’s a lovely, comforting moment of creative self-care—and then all the lights go out, and she’s in the dark with her chocolate (probably melting, maybe gone) and the vacant receiver. So she does what we all feel when we’re thwarted by the incompatibility of making art and making a living, which is to scream at the top of her lungs to the audience of zero, “I HATE IT!” I think about this often—I’ve never seen a truer depiction of what it’s like. But lest you think the movie is a downer, I assure you it is not. Vibing overall somewhere between the pie-in-the-sky Vogue spread and the sinking reality of wedding photos, Girlfriends manages to be both honest and buoyant. —Jane Breakell

Will Harris, whose collection RENDANG was published by Wesleyan University Press earlier this month, brings back my poetry education with nimble irreverence. His play (in the lines, in the margins, in the points of view) brings a kind of thrill more like Zadie Smith’s handling of E. M. Forster than a jazz musician’s bravado riff. Take “From the other side of Shooter’s Hill,” in which the reader enters the poet’s work space: “OK, you said, suddenly embarrassed, but wait, / why am I telling you this? Don’t you dare think about using me / in a poem, making me into some sad female cypher.” And she is there still, sad and lovely as any female cipher in, for instance, the work of Randall Jarrell or Yehuda Amichai, but here she is in her own voice demanding personhood. Or does she? The poem ends with the further complication of craft, musing on the difficulty of recall, the “impossible to tell who was speaking.” There is “Hanged Man,” a poem with a classic title (or a pseudo-serious reference to tarot) and an immediately relatable twenty-first-century voice: “I hate Bruce Springsteen, he thought. I want to eat better.” But is the third-person voice just a nudge and a wink to the assumption of the confession? Later, there is the line “Hanging there. His parents were alive and dead,” which is the stuff of dreams, though imagine it also as a game with the reader who, after noting references made throughout the book to ailing fathers and a Chinese Indonesian mother, wants to know truths about these people. Harris is so copiously talented that he begins the collection three times rather than once: with a concrete poem, a soliloquy and dedication, and, were you not convinced, a poem whose first line is “everywhere was coming down with Christmas”—which is, I’d say, a banger. Harris is also the author of Mixed-Race Superman, in which he writes about his multiracial background as well as those of Keanu Reeves, Barack Obama, and Friedrich Nietzsche. The desire to represent, to speak on race for himself, is in RENDANG, too, but so is an analysis of that representation and some dialogue with that desire. This would be enough to make RENDANG a standout collection, but Harris has had his time with a pen and in a workshop, and he shows rather than tells that his work is so many other things besides. —Julia Berick

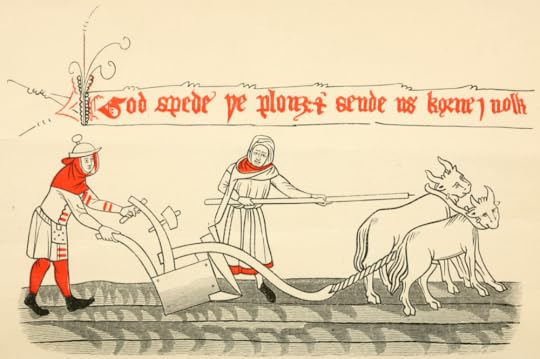

Upon finishing my final semester of college from the (dis)comfort of my childhood bedroom, I felt as though I were being suddenly yanked from the security I’d cherished within small class discussions about books I could barely comprehend. So when a group of my professors emailed me and a group of my former peers about reading William Langland’s fourteenth-century text Piers Plowman over the “somer seson,” it was as if someone had offered me a kernel of truth I’d thought long lost. I can comfortably say that the kernel is still lost, because the endless digressions and inconsistencies of Piers make any sort of search for truth close to impossible. This is not to suggest I found Piers to be a waste of time. On the contrary, it proved to be one of the highlights of my quarantine summer! As our little team tackled the B text of the Middle English poem every week, I experienced the emotional ebbs and flows of comprehension attempting to gain a foothold on the beachhead of my literary training, only to be washed away every time Saint Truth herself felt nearby. Each passus brings you into a dreamlike state—not unlike the seven dream visions Langland himself endures—that presents you with ideals such as conscience personified, only for those personifications to jeopardize repeatedly their own symbolic attachments and logical integrity. The text contradicts itself constantly, frustrating all our attempts to wrestle with its lessons on truth, Christian theology, and the failings of all the virtues. However, in those contradictions lies a nearly imperceptible nuance that rewards trying to find some semblance of truth in equal part to its head-scratching confusion. Through a community of reading, I felt a certain solidarity in our bewilderment, which facilitated my acceptance of the fact that I will never fully understand this poem. The road to truth is inexhaustible; all I can recommend is calling up your former roommate who knows Middle English and spending some of your isolation so confused in the realm of dreams that when you reemerge, the real world feels slightly less erratic. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Illustration from an 1887 edition of Piers Plowman, by William Langland.

There Was Beauty

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces in real time the moments before her daughter leaves for college. The column ran every Friday in November, January, and March. It returns for a final month this August, as Jill and Indie take one final road trip together to Indie’s college campus.

“What is documented, at last, is not the thing itself but the way of seeing—the object infused with the subject.” — Mark Doty

I’m reading the billboards along I-44 East while my daughter, Indie, sleeps in the passenger seat. Today is our second seven-hour drive on our trip to her college in New York. We left Texas Wednesday, and we’ve made it through Oklahoma and Missouri. Now we’re halfway through Indiana, where I pass a sign for foot-high pies. Indie stirs and sits up, tells me she wants to drive.

We talk about that difficult year often now, turn its pages. For years we didn’t. Maybe it’s because she’s leaving, but for the past few weeks we’ve been trading stories about all the places we’ve lived, and that one comes up more than the others. What we carry from it.

Over the phone, the landlady had described the couch, the coffee table, and the desk that would be in the basement apartment before we arrived, but the day we opened the door to our new home, we found a twin bed against the wall. For a year, Indie slept on the mattress on the floor, and I slept on an air mattress on top of the box spring. Our small dining table, the only furniture we brought, took up most of the kitchen and became my writing desk.

That year, Indie walked the two blocks to the elementary school on the corner. Sixth grade. I’d go one block with her, then stand on the sidewalk and watch until she stepped through the gate. Back at the house, I’d climb the steps down to the basement to write or prepare for the two classes I taught at a university downtown. The footsteps of the man who rented a room on the first floor were heavy, unsettling. The landlady hadn’t mentioned he lived there.

We cross into Ohio, glide through unwavering greenery and billboards for antique stores. Indie passes a flatbed truck stacked with bags of grapefruit. I snap a photo.

On the fifteenth of every month that year, my mother sent me a check to help out, and she sent Indie a small stack of single dollar bills. An hour after we pulled away from that house for the last time, I checked my rearview mirror to make sure the buildings of downtown were miles behind us.

But there was beauty that year: The tree outside our landlady’s front yard—she paid me forty dollars a month to buy seed and keep the birdhouses full. All the hours those birds would flit and fly outside the window as I wrote. The sidewalk one morning after Indie and I had taken our nightly walk as she pulled petals from red tulips between our steps. The days we took off for the beach, Indie riding her scooter while I ran behind. The bookstore.

Every time we went, Indie and I’d go straight to a book she found in the children’s section. It was Jon Klassen’s I Want My Hat Back, an illustrated hardcover with a bear on the front. The book begins, “My hat is gone. I want it back.” I’d whisper-read while Indie turned the pages. We loved how the bear asks a fox and a frog and a turtle and a rabbit (wearing a red hat) and a snake and some other creature the same question, “Have you seen my hat?” And while none of them claim to have seen the hat (not even the rabbit), our favorite response was the mysterious creature’s: “What is a hat?” We’d giggle in the aisle then set the book back on the shelf, sorry to leave it behind.

At the end of that year, we moved to New Mexico, a three-day drive. On the second day, before we left a La Quinta in Amarillo, Texas, Indie gave me my birthday present. It was wrapped in paper that looked like an antique map, along with a note she had written on half a piece of white paper, as if she had carefully torn it down the middle after creasing it. The note was decorated with silly faces and hearts and stick figures (us holding hands) and I love yous.

When I pulled back the wrapping paper, there it was—the book with the bear on the cover.

Back home, I keep the book on an end table in our living room. The wrapping paper’s still inside, along with Indie’s note. I’ve always thought of the book as a map, an answer to the question, “What is a home?”

As we pass silos and barns, the miles speed by.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here.

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

August 13, 2020

Listening for Ms. Lucille

The Summer issue features two previously uncollected poems by Lucille Clifton: “poem to my yellow coat” and “bouquet.” These—along with eight more newly discovered poems and a career-spanning survey of her work chosen by the poet and editor Aracelis Girmay—appear in How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton , which will be published by BOA Editions next month. Below, read the first five sections of Girmay’s twelve-part foreword to the book.

Lucille Clifton. Photo: Rachel Eliza Griffiths.

No one writes like Lucille Clifton, and yet, if it were possible to open a voice, like a suitcase, to see what it carries inside, I believe that within the voices of many contemporary U.S. poets are the poems of Lucille Clifton. There is the ferocity of her clear sight. There is the constellatory thinking where every thing is kin. The verbs of one body might also be the verbs of another seemingly disparate or distant body (her streetlights, for example, bloom). And all things have agency: as the speaker of “august the 12th” mourns a distant brother on his birthday, the speaker’s hair cries, too (“my hair / is crying for her brother”). The poems, in their specificity and dilating scale, startle readers into new sense. They discomfort as often as they bless, and they bless as often as they wonder—bearing witness to joy and to struggle.

Over the course of her life, Clifton wrote thirteen collections of poems, a memoir (which she worked on with her editor Toni Morrison), and more than sixteen books written for African American children, including Some of the Days of Everett Anderson and Black BC’s. And in 1988 Clifton was the first writer to have two books of poetry appear as finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in the same year. Those books were Next and good woman.

Her works are explicitly historical and of a palpable present moment. The earliest of the poems in How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton were written during the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the nuclear age, ecological crises, and independence movements across Africa. As the poet Kevin Young writes in the afterword of the monumental Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965–2010: “Both the poetry world and the world of the 1960s were in upheaval; the years from 1965 to 1969 saw the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, and the first human walking on the moon, all of which appear in the poems … The Black Arts movement, which Lucille Clifton found herself a part of and in many ways helped to forge, insisted on poems for and about black folks, establishing a black aesthetic based on varying ways of black speech, African structures, and political action.”

Clifton’s first book, good times, was published when her children were ages seven, five, four, three, two, and one. Her daughters Sidney, Gillian, and Alexia remember their mother’s writing as part of their daily life: “As children, we watched our mother type on her old-fashioned typewriter at the dining room table. For us, this is what mothers did; and where they did it; create worlds, play games, and share meals in the same place. Her creating space was her sanctuary, and ours. So it is with her every word.” Such insistence on acknowledging all worlds in all spaces has emboldened and nourished so many of us otherwise encouraged to shut down our truest circuitry. Instead, her poems pulse with the miracle of the porous and daily. Distilled yet capacious, her poems, like seeds, are miraculous vessels of past and future, of dense and elemental possibility. However large the story they carry, they are always scaled to the particular and resonant detail that amplifies the world at their center.

*

Lucille Clifton was born Thelma Lucille Sayles on June 27, 1936. If someone happened to have looked up at the moon that day they would have seen what looked like a moon split in half, 57 percent of the surface of the moon visible from the earth. I love to think of this poet born with twelve fingers under a moon half visible, half invisible to our eyes. This poet of one eye fixed and another wandering, feeling both ordinary and magic, standing astride at least two worlds, being born out of one Thelma (her mother) into the old and new bones of her own name. Of this naming she writes:

light

on my mother’s tongue

breaks through her soft

extravagant hip

into life.

lucille

she calls the light,

which was the name

of the grandmother

who waited by the crossroads

in virginia

and shot the whiteman off his horse,

killing the killer of sons.

light breaks from her life

to her lives …

mine already is

an afrikan name.

Her poem reveals an archive of, among other things, some of what African America does to English and some of what English does to African America. In the memoir Generations she writes this of her lineage: “And Lucy was hanged. Was hanged, the lady whose name they gave me like a gift had her neck pulled up by a rope until the neck broke and I can see Mammy Ca’line standing straight as a soldier in green Virginia … and I know that her child made no sound and I turn in my chair and arch my back and make this sound for my two mothers and for all Dahomey women.”

Such repetitions of names and stories move across her work. Histories written in circles much like time and weather are recorded in the rings of a tree. It was toward such repetitions and echoes that I listened, and out of them I began to see the shape of How to Carry Water rendered with documentary, spiritual, and mystical sensibilities. Peter Conners, my editor and the publisher of BOA Editions, calls it “listening for Ms. Lucille.” I tried to listen so close I even dreamed of her voice one January morning. It seems not mine to keep but something I should share with you: You’re always whole, she said. Except when you’re dreaming you’re a quarter open.

*

I tried to walk back through the final selections open as I’d be in a dream, or toward that kind of openness anyway. I listened for what I understood to be repeated resonances and reckonings across her life—the power of words, the loss of her mother, the deaths of the beloveds, the poem as a way to wonder, wonder as a way to live. Abortions. Children. The magic of hands. The violations of hands. Environmental crises and the links between racial violence and the devastation of the environment. The terrible stories of the terrible things we do to one another. I listened and heard something mystical: “the light flaring / behind what has been called / the world … ” I listened for what was strange and mysterious and a quarter open. I listened for what was sharp, clear, and yet prismatic and complex. I heard her, again and again, claim her Ones as the ones in the ground without headstones, the ones ringing like black bells, Black people, Black women people. Clifton says:

study the masters

like my aunt timmie.

it was her iron,

or one like hers,

that smoothed the sheets …

Part of her brilliance is in her ability to name, with specificity, her kin, while also leaving an opening for those outside of the frame of her particular knowing. The words “like” and “or” anchor us in the concrete while pointing us to a knowledge still outside of the poem.

*

How to Carry Water begins with the poem “5/23/67 RIP.” Written in 1967, it was not published until 2012, in The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965–2010. I give deep and abiding thanks to the editors Kevin Young and Michael Glaser for the hours and devotion that brought that collection into the world, and out of which How to Carry Water emerges.

In “5/23/67 RIP” Clifton mourns the loss of the great Langston Hughes, writer, activist, and chronicler of Black Life. The poem, dated one day after his death, closes with a lament (“Oh who gone remember now like it was … ”) and in the lines directly above I come to understand that his death also marks Clifton’s eye as she reads even the moon through the veil of her own mourning:

… make the moon look like

a yellow man in a veil

watching the troubled people

running and crying

…..Oh who gone remember now like it was,

…..Langston gone.

The poem is an attempt to remember a community’s loss while simultaneously marking the impossibility of that record ever being precise enough. The decision to begin How to Carry Water here carried a few hopes. I wanted to mark Clifton’s documentary sensibility and a strange, triple-eyed imagery where the moon, for example, looks like a yellow man in a veil, a mourner among mourners, but also watching, like, maybe, a poet. A poet like Langston, a poet like Ms. Lucille.

*

How to Carry Water begins with “5/23/67 RIP” and moves chronologically across the work ending with ten previously uncollected poems. Most of these poems my sister-poet Kamilah Aisha Moon and I came upon together while visiting Clifton’s papers at Emory. To see those poems, whose margins were sometimes scribbled with the math of bills and the drawings of children, was to have yet another sense of the hours and breaths by which the poems were made. And to read across her revisions was to also sense the circuitry and pull of her own listening. In “Poem With Rhyme,” for example, she changes: “I have cried, me and my / possible yes … ” to “I have cried, me and my / black yes … ” This change from “possible” to “black” to me revealed a circuitry of association. For Clifton the lineage of “black” is a lineage of possibility.

I revisited those poems again and again to see which, if any, might resonate with the other poems I’d already set aside for How to Carry Water. A few of them, yes, seemed to utterly be a part and so I contacted the publisher and Clifton’s daughters. Now these are the last poems of the book. This said, it is not clear to me when these poems were written. I love that an otherwise chronological organization is troubled by these poems I cannot place in order or time definitively. This, too, seems essential and part of what her work offers. This, too, seems part of what I have been listening for.

Read two previously uncollected Lucille Clifton poems from the Summer issue: “Poem to My Yellow Coat” and “Bouquet.”

Aracelis Girmay is the author of three books of poems, most recently the black maria (BOA Editions, 2016), for which she was a finalist for the Neustadt Prize. She is the editor of How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton (2020).

From How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton , edited by Aracelis Girmay, published by BOA Editions on September 8, 2020. Copyright © 2020 by Aracelis Girmay. All rights reserved.

A Lost Dystopian Masterpiece

In her column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be. This month, she examines an anomalous work, They, in Kay Dick’s already anomalous oeuvre.

Kay Dick is a name all but forgotten today, but in the midtwentieth century she was at the heart of the London literary scene. A list of the guests regularly entertained by her and her partner, the novelist Kathleen Farrell, at their Hampstead home—they lived together from 1940 to 1962—includes a host of successful and popular writers of the era, including C. P. Snow, Pamela Hansford Johnson, Brigid Brophy, Muriel Spark, Stevie Smith, Olivia Manning, Angus Wilson, and Francis King. I mention them here, because it was the scathing description of Dick’s treatment of her friends, as detailed in her obituary in the Guardian in 2001, that first attracted my attention.

“For many years,” wrote the writer and journalist Michael De-la-Noy, “the novelist Kay Dick, who has died aged 86, was at the centre of literary intrigue and gossip.” The claim he then makes—that she “expended far more energy in pursuing personal vendettas and romantic lesbian friendships than in writing books”—is cutthroat enough to smack of a vendetta all of its own. He describes her as a failed artist, “a talented woman bedeviled by ingratitude and a kind of manic desire to avenge totally imaginary wrongs.” De-lay-Noy’s obituary is less a celebration of Dick’s life and more an all-out character assassination, one that details a litany of grudges maintained, ambitions thwarted, and friendships cruelly smashed to smithereens. Needless to say, I was intrigued enough to immediately hunt down Dick’s books.

Initially, I was slightly disappointed by what I found. Her first four novels—By the Lake (1949), Young Man (1951), An Affair of Love (1953), and Solitaire (1958)—which tell stories of romantic or familial entanglements against the backdrop of refined European settings, were elegant but not especially memorable. Her fifth work, Sunday (1962), proved more absorbing, especially in its psychological astuteness. It’s a loosely autobiographical novel about her childhood (Dick was born in England in 1915, but educated in Geneva, then at the Lycée Française in London, before leaving home at the age of twenty “to mix with a louche set,” as she later put it in an interview) and her relationship with her glamorous single mother. “She must have had great courage,” wrote Dick in an autobiographical piece that detailed the story of her birth, “because illegitimacy in the First World War was a very unpleasant business to be mixed up with, especially for a woman brought up in a reasonably privileged fashion.” But then, almost out of nowhere, I found myself completely bowled over by Dick’s penultimate novel, They: A Sequence of Unease (1977). This disquieting, lean, pared-back dystopian tale, which won the now defunct South-East Arts Literature Prize, is a complete departure from her previous volumes. Reading it was like reading the work of an entirely different writer.

At less than a hundred pages, They is either a novella consisting of nine chapters, or a collection of nine interlinked short stories. The Times’s critic Philip Howard opted to describe it as the latter, and I’m inclined to agree, not least because the final episode, “Hallo Love,” was originally published as a stand-alone piece two years earlier, in 1975. Set amid the countryside and the beaches of coastal Sussex, They depicts a world in which plundering bands of philistines prowl England destroying art, books, sculpture, musical instruments and scores, punishing those artistically and intellectually inclined outliers who refuse to abide by this new mob rule.

Given that the actions of Ray Bradbury’s book-burning “firemen” are not dissimilar to that of Dick’s titular unnamed collective marauders, Fahrenheit 451 (1953) is an obvious point of comparison. As, of course, is Orwell’s 1984. Yet in its style and tone, They is actually much more reminiscent of the work of experimental British writer Ann Quin (is it just a coincidence, I wondered, that one of Dick’s characters is named “Berg,” the same as the eponymous protagonist of Quin’s 1964 debut?) and Anna Kavan’s enigmatic, almost psychedelic final novel, Ice (1967). Kavan’s book, in which a man pursues a silver-haired woman across a snowy, postapocalyptic wasteland, reads like a strange, eerie dream sequence; a description that could also be applied to the unsettling, cryptic episodes of They. Kavan’s much mythologized midlife reinvention was brilliantly summarized by Emma Garman on the Daily: “Once a wholesome young English housewife who wrote conventional women’s fiction, so the story goes, in her thirties she was confined to an insane asylum and emerged as a chic, emaciated bottle-blonde heroin addict, wielding a bleak and anarchic new literary voice,” and it explains the austere nihilism of Ice. Quin—whose struggle with mental illness also suffused her work—never modulated her writing voice. They, however, is all the more fascinating because it’s a complete anomaly in Dick’s oeuvre: a surreptitious late-career aberration, whose genesis is unclear, and which does not seep into what she writes after.

*

It’s apt then that much of the novel’s power lies in its mystery. The narrator—if, indeed, we’re listening to the same single voice throughout—seems to be a writer, who lives in a book-filled ex-coastguard’s cottage, alone apart from their dog. They are never named. Nor is his or her gender revealed, something that’s in line with what Kris Kirk, in an interview with Dick in the Guardian in 1984 described as Dick’s “androgynous mental attitude.” Dick had just finished explaining why the “overall tone” of the personal relationships depicted in her books is always bisexual, which is how she herself identified. She also notes that although she’s sexually attracted to both men and women, there’s “something extra” in her relationships with the latter; “this love, this emotion,” she clarifies. “I have certain prejudices and one of them is that I cannot bear apartheid of any kind—class, colour or sex,” she tells Kirk. “Gender is of no bloody account and if anything drives me round the bend it’s these separatist feminist lessies.” Given that Dick made a habit of loosely fictionalizing her own experiences, I’ve come to think of her protagonist in They as female. Even more inscrutable though are the “they” of the book’s title; “omnipresent and elusive,” as Howard describes them, extremely dangerous and violent, but also strangely vacant and automaton-like. “They” are rarely distinguished as individuals, which situates them in stark contrast to the narrator and her acquaintances.

In the opening episode, “Some Danger Ahead,” the narrator goes to visit the first of these; a man called Karr and a woman called Claire (perhaps husband and wife, we’re never told). Claire, a painter, is working in her studio, and Karr has an impressive library of books. Walking home later that day, the narrator stops by the village shop. “It’s the books at Oxford now,” she’s informed, in the manner of the latest gossip being relayed. No explanation follows. All we’re told is that she feigns disinterest in the news. We’re left in the dark as to what’s being discussed, but the narrator herself clearly knows what’s going on. “It must be possible…” she begins to ask Karr when she returns to his house the following day. “To be missed?” he finishes the question for her. “We shall all be reached,” he tells her. Later still, when she returns to her cottage, she notices that her copy of Middlemarch is missing from her bookshelf. “They took another book last night,” she tells Claire the next morning.

A new servant appears at Karr’s house. “They sent him,” Karr tells the narrator. “They cleared the National Gallery yesterday,” Claire reports shortly thereafter. Karr, it’s explained, is “training” a young boy named Jake (possibly his and Claire’s son, possibly not, Jake’s relationship to the adults is never explained) to remember that which is being destroyed, including scores composed by a man named Garth—who’s in love with Claire—and poems written by the narrator.

As the days pass, more books disappear from the narrator’s shelves. One evening, the friends sip champagne on Karr’s terrace, looking out over the estuary. When, the group later goes inside, they discover that Karr’s library has been stripped of books and the pictures have been removed from the walls. “Claire stroked the spaces where each painting had hung,” then she tells the others she has one more piece to finish and retires to her studio to work. Later that night, the narrator and Karr watch her being led away by “them.” What will happen to her, the narrator asks:

“They will blind her, and return her to me,” Karr said. “She went beyond the accepted limit. She continued to paint.”

Garth raced after them.

“And to him?” I asked.

“They will make him deaf,” Karr said.

“And to me, if?” I was ice all over.

“They would amputate your hands and cut out your tongue,” Karr said. “You’d better destroy the letters you’ve written. One must not leave them any possible opening for confrontation.”

As these vicious acts of retribution are described, a chill just as glacial as that assaulting the narrator descends over the reader. Later we learn that as well as corporal punishment, psychological torture is also employed. Those who resist are taken to treatment centers housed in tall, imposing, jail-like towers, where they’re purged of their memories and emotions.

One element that makes the book especially disturbing is that “they,” whoever they are, are not a government-sanctioned group like Bradbury’s firemen or Orwell’s all-pervading government surveillance, but rather an unsanctioned multitude, the strength of which appears to lie not in official mandates, but rather in the swell of their ever-increasing numbers. “Loners,” as “they” refer to the narrator and her kind, are more at risk than couples or families—“None-conformity is an illness. We’re possible sources of contagion,” another character explains. Television, for example, is compulsory. In a later episode, great bands of “them” march across the downs, “each one holding a pole to match his height.” Disinterest is the narrator and her friend Julian’s only defense. “Don’t look back,” he tells her. “We must not appear inquisitive.” So, too, excessive displays of emotion are forbidden. Love itself has been outlawed. In the final story, the narrator is “permitted” a fortnight of expressing pain after she falls and sprains her ankle: “I allowed myself the luxury of going utterly to pieces for forty-eight hours, moving like one demented through the hours, flooding my mind with old memories, metaphorically wailing at the wall of my loss.” She wonders what other injury she might inflict upon herself so as to be allowed similar “relief” in the future. It’s chilling, but compellingly so. All the more so because of the seamless way in which Dick stitches together what’s an evocatively drawn portrait of otherwise idyllic rural England with this shadow landscape of fear and violence. As Howard concludes in his review, They is “strong stuff, beautifully written, to make a man look behind him in fear and dread when walking down a leafy lane.”

The episodes described thus far read as windows onto a broader, single narrative of “we”—the narrator and her various cultured, artistic friends—versus “them.” Others, however, while set in the same milieu, have the feel of stand-alone tableaux, ending, as they do, on cliff edges of horror. The most arresting of these is “Pocket of Quietude,” in which the narrator travels to visit a man called Hurst who lives in a mill full of his artist son’s paintings, though the son himself is ominously absent. Two more refugees arrive, Russell and Jane—he plays the piano, and she’s a poet, though she’s recently had to learn to write with her left hand, her right having been badly burned, held over an open fire for eight minutes while “they” destroyed her work in the flames below. The mill initially seems like a safe haven, but underneath the surface, dark forces are at work. Hurst is a man “enriching” his “tomb”; he adds to his treasure trove, but in doing so he has to sacrifice those who bring him their work.

There are many ways to read the book: as a straightforward Orwellian dystopia, a sequence of vividly drawn nightmares, or, if we’re to believe De-la-Noy’s portrait of a writer who never fulfilled her potential, perhaps even as a metaphor for artistic struggle.

*

De-la-Noy’s obituary is ruthless, but a more equitable, less hyperbolic appraisal of Dick’s life and work reveals an utterly beguiling woman, one whom, although undoubtedly spiky, actually produced a large body of important work while also living an extremely full, free life in the company of many dear friends. Pierrot (1960), for example, Dick’s study of the commedia dell’arte is considered something of a definitive work on the subject. Then, during the fifteen-year gap between Sunday (1962) and They (1977), she published two absorbing volumes of literary interviews: Ivy and Stevie (1971), and Friends and Friendship (1974). Writing in the Times in 1974, A. S. Byatt declared that the former “would always be required reading” for anyone interested in either of its subjects, Ivy Compton-Burnett and Stevie Smith. Dick’s obituary in the same newspaper attributed her success as an interlocutor to the fact that she was a woman of “sympathy and perception,” one who’d “persuaded two naturally reticent women writers […] to reveal more about their inner lives than they had ever done to anyone, except obliquely through their writings.”

In the forties and fifties, we see in Dick a writer learning her craft. During this time she also worked in bookselling and publishing: aged only twenty-six, she became the first woman director in English publishing, at P. S. King & Son, and later she was the editor of The Windmill (under the pen name Edward Lane), a short-lived but acclaimed literary periodical. But it’s in the latter half of her career that she comes into her own as a writer. The flashes of brilliance found in Sunday are a more permanent fixture in her subsequent autobiographically inspired project, The Shelf (1984), the novel that followed They, and the final book Dick published. The Shelf is intriguing enough that I toyed with making it the subject of this column, before They won out. Written as a letter to her intimate friend Francis (presumably Francis King) it relates the story of a brief sexual affair Dick had with a married woman in the mid-’60s, not long after the breakdown of her relationship with Farrell. With its echoes of Jean Rhys’s stories of unhappy love affairs, what begins as a “wonderfully wanton adventure” swiftly turns into a tragedy when the narrator’s lover commits suicide. As Elaine Feinstein wrote in the Times, this “short, fierce, intelligent novel is as subtly accurate about the aphrodisiac effects of Lesbian love as it is about the pain of loss: and forgetting: and the fear of death.”

“I think,” Dick as her narrator, Cass, movingly writes, “that it is right and renewing to remember acts of love because, in the relative brevity of our lives, there is not time enough for loving. Until I brought myself back to recall that exuberant pleasure, I had almost forgotten about it, placed it, as I said, on the shelf, somewhere in my memory. One should be less mean with one’s memory of love, bring it out now and then, let it glow inside one as a positive element of our experiences to be cherished and to be grateful for. It is all too easy in troubled and preoccupied times to forget the blessings.” This spoke to me, that final line in particular, in our own troubled contemporary times. And here, as in moments in They—“Karr and I sat in the library, which was also a way of loving”—Dick shows herself to be a masterful writer, both more candid and more compassionate than De-la-Noy appreciated. Like any strong allegory, They can be read many ways, but is perhaps best, and most accurately, read as a plea for individual and intellectual freedoms by a woman artist who refused to refused to live by many of society’s rules. As Dick writes in Friends and Friendship, “it is an extremely courageous act to be a writer, painter, composer, because you are out on your own, in limbo, totally unprotected, not much encouraged, driven only by some inner conviction and strength, and the discipline is yours alone.”

Read earlier installments of Re-Covered here .

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

August 12, 2020

Renee Gladman’s Sentence Structures

In 2013, Renee Gladman began drawing a series of dense, looping works that assume the characteristics of handwriting but prove to be indecipherable, a sort of scrawled sprawl of imagined structures. To readers of her Ravicka novels, which take place in a fictitious city-state full of surreal architecture and impossible phenomena, this should sound familiar; no matter the medium, Gladman pursues the limits of language, form, and communication. A selection of these drawings appears in Image Text Ithaca Press’s lovingly constructed One Long Black Sentence , printed in white ink on black paper and accompanied by a contribution from Fred Moten. Below, take a look inside the book.

From Renee Gladman’s One Black Sentence , published by Image Works Ithaca Press.

Losing Smell

My mother, a classically trained dancer, didn’t stop dancing all at once. When she moved to America, she still performed, still taught. She stopped teaching when I was little. Still, she would sometimes be called into action, choreographing dances for the school plays my brother and I were in. A couple decades later, she stopped doing even that. Now, I know, she doesn’t even dance by herself, in her kitchen, as I remember her doing when I was a child. “I could give up dancing,” she told me once. “It wasn’t as if I was going to die. Only, it felt like the color went out of the world.”

*

There have been stretches of time when I have been unable to look at my life through language. What I mean is I was unable to write, but that is not only what I mean. There is a way I move through my life that is about putting language around its small pleasures, the sight of neighborhood flowers or strangers embracing or a crow slipped into a disorienting current of air and gliding backward: the narrative of my own life and the movements between its characters, and the narratives of my friends’ lives revealed through long conversations while walking through my city, on the phone or in person: a way of living in words even if they are not written.

I am not always going around in this state, catching the soft smell of the chamomiles in the tall green vase on the dresser, moved nearly to tears by the sound of my daughter’s laugh in the evening—I wish! Like anyone, I am often preoccupied with the petty anxieties and logistics that rule my days: it’s just that, from time to time, and sometimes more often than others, a window opens. I catch a gust of fresh air, of language. A sentence forms in my head. When I am able to live this way, I understand who I am, even if I am not writing. When I am not living this way, when I am unable to reach out to something beautiful and to name it, I am wretched, a stranger to myself. The color drains out of the world.

*

Of the five senses, sight is the most obvious; smell the most subtle. For those of us who have the full use of these senses, we rely most heavily upon sight, sound, and touch to navigate the world and keep our bodies safe from danger. Aside from the danger of not being able to smell smoke if there’s a fire, people who live without smell can go about their lives without obvious impairment—it is probably the sense you are least likely to notice once it is gone.

I think of smell, and its sister, taste, as the artists of the senses. They’re the ones that seem to exist most obviously for pleasure. Long before neuroscientists mapped the connection between smell and memory, many writers exquisitely intuited it in their work. Perhaps it is this link to memory, a link that bypasses language entirely, that makes their pleasure so rich, so meaningful. Sight, no matter how close a viewer gets to her subject, always keeps one at a remove from the world, as we read, interpret, what we see. Smell, on the other hand, renders the world responsive; it enters you.

Without obvious impairment: people who lose their sense of smell report higher occurrences of psychological ill effects like depression. There is a dullness to the world without scent. Even the bad smells call something up in us, unsettle memory and mood just below the surface of our thoughts. “The links between smell and the language centers of the brain,” writes Diane Ackerman, in her excellent A Natural History of the Senses, “are pitifully weak. Not so the link between smell and the memory centers, which carries us nimbly across time and distance.” Catch the scent of a lemon tree that recalls the bloom of long-ago trees in some summer backyard when you were a child and the present moment deepens, the slant of light, of marriage, the hand wrapped around a cold sweating beer, the summer of adulthood linked to all the summers before. Smells not only tell us about the world, they tell us about ourselves, the lives we have lived. They let us exist in many moments of time at once without even realizing it; they give our experience of the world its color.

*

We have all lost, temporarily, our sense of smell. For some of us, it is because we have experienced the virus—in some cases, the sinister lack of this sense has alerted us to the virus’s presence in our bodies. But for more of us, it is because we cover our nose and mouth when we go outside. For me, I first smell the cloth of the mask, then nothing but my own breath. Some very potent smells creep in, at the edges, but are severely muffled. The world outside my apartment is technicolor against my starved eyes—but it is flat, odorless, like a movie.

*

The longest time I lost my words was after my daughter was born. A week after she was born, I was awake, holding the baby, three in the morning, bleary, writing in my notebook, “With one hand I hold the baby, and with the other I write.” I wrote only this sentence. There was an empty feeling, a kind of blankness where the true words used to be. So when I wrote, when I forced my pen across the page, or more often, my fingers across the keyboard, it was a frantic performance with which I tried to prove to myself that I was not lost, but wound up proving the opposite. What if I never wrote again, I consoled myself, but just lived beautifully, as though I were in a story? But that meant living and thinking in language, which was almost the same as writing, and I didn’t have words. Without the words to describe it to myself, that year was the loneliest of my life.

*

Color, I keep saying. I am, like most of us, born sighted, a visual creature. In fact, as Ackerman points out, there are relatively few words for scent. “When we use words such as smoky, sulfurous, floral, fruity, sweet, we are describing words in terms of other things (smoke, sulfur, flowers, fruit, sugar).” There are literally no words—or at least very few—to describe the way we smell and its lack.

*

I bike with my daughter to Golden Gate Park. At the edge of an empty stretch of field, we get off the bike—she’s running with joy as soon as her little feet touch the grass. She’s not yet two, and doesn’t wear a mask: I have been huffing and sweating in mine, and my glasses are fogged. The sight of so many trees, so much green, relaxes my eyes: the piercing sight of this tree, who we have been visiting throughout quarantine, and whose exquisite hugeness I realize means it is a very old tree. Right now, it is so clothed in spring’s verdancy that it seems young, very young, and happy, and gentle, and wise. It is like seeing the face of a friend. Still, it is only when (no one in a twenty-foot radius) I slip off my mask that tears prick my eyes. The park comes rushing into me, the smell of cut grass, of my own sweat in my cotton T-shirt, the alcohol of my sanitized hands, sun on leaf, damp air lanced with spears of light, sweet, wet earth. All at once, the world is alive in me, and I am alive again in the world.

*

My mother doesn’t dance anymore. But recently she has started teaching the mudras to my daughter, who was born with her graceful hands.

*

I don’t quite know when I started to think again in sentences. Maybe I noticed the breeze from the open window and caught the first lick of fog in the summer air. It could have been a book that I was reading that brought me back into language at last, so saturated by the beauty of the writer’s sentences that I looked up and made one of my own. I started naming again: pink wine, marigolds growing in a pot, sorrow, ice cream, summer.

*

Slowly, slowly, they came back: the words. They always do.

Read Shruti Swamy’s story “A House Is a Body” in our Summer 2018 issue.

Shruti Swamy’s fiction has been included in the 2016 and 2017 editions of The O. Henry Prize Stories. Her collection A House Is a Body is out this week. She lives in San Francisco.

August 11, 2020

Redux: The River Never Dwindled

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

James Baldwin in Hyde Park, London. Photo: Allan Warren.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re celebrating our ongoing summer subscription offer with The New York Review of Books. For only $99, you’ll receive a yearlong subscription and complete archive access to both magazines—a 38% savings.

To mark the occasion, we’re unlocking pieces from the archives of both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books. Read on for James Baldwin’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with his essay “An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis”; Joyce Carol Oates’s short story “Heat,” paired with her essay “Shirley Jackson in Love and Death”; and Elizabeth Bishop’s Art of Poetry interview, paired with two poems.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read their entire archives? And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

James Baldwin, The Art of Fiction No. 78

The Paris Review, issue no. 91 (Spring 1984)

Write. Find a way to keep alive and write. There is nothing else to say. If you are going to be a writer there is nothing I can say to stop you; if you’re not going to be a writer nothing I can say will help you. What you really need at the beginning is somebody to let you know that the effort is real.

An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis

By James Baldwin

The New York Review of Books, volume 15, no. 12 (January 7, 1971)

One might have hoped that, by this hour, the very sight of chains on black flesh, or the very sight of chains, would be so intolerable a sight for the American people, and so unbearable a memory, that they would themselves spontaneously rise up and strike off the manacles. But, no, they appear to glory in their chains; now, more than ever, they appear to measure their safety in chains and corpses. And so, Newsweek, civilized defender of the indefensible, attempts to drown you in a sea of crocodile tears (“it remained to be seen what sort of personal liberation she had achieved”) and puts you on its cover, chained.

Joyce Carol Oates. Photo: Dustin Cohen. Courtesy of Ecco Press.

Heat

By Joyce Carol Oates

The Paris Review, issue no. 110 (Spring 1989)

It was midsummer, the heat rippling above the macadam roads. Cicadas screaming out of the trees and the sky like pewter, glaring.

The days were the same day, like the shallow mud-brown river moving always in the same direction but so slow you couldn’t see it. Except for Sunday: church in the morning, then the fat Sunday newspaper, the color comics print on your fingers.

Shirley Jackson in Love & Death

By Joyce Carol Oates

The New York Review of Books, volume 63, no. 16 (October 27, 2016)

Characterized by the caprice and fatalism of fairy tales, the fiction of Shirley Jackson exerts a mordant, hypnotic spell. No matter how many times one has read “The Lottery,” Jackson’s most anthologized story and one of the classic works of American gothic literature, one is never quite prepared for its slow-gathering momentum, the way in which what appears initially to be random and casual is revealed to be as inevitable as water circling a drain. As the stark title “The Lottery” suggests an impersonal phenomenon, the story’s perspective is detached and reportorial; a kind of collective consciousness emerges from the inhabitants of a small unnamed New England–seeming town that finds expression in tonally neutral commentary reminiscent of Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony.”

Elizabeth Bishop. Photo: Alice Helen Methfessel. Courtesy of Frank Bidart.

Elizabeth Bishop, The Art of Poetry No. 27

The Paris Review, issue no. 80 (Summer 1981)

I’m not very fond of poetry readings. I’d much rather read the book. I know I’m wrong. I’ve only been to a few poetry readings I could bear. Of course, you’re too young to have gone through the Dylan Thomas craze …

Two Poems

By Elizabeth Bishop

The New York Review of Books, volume 53, no. 5 (March 23, 2006)

Whatever there was, or is, of love let it be obeyed:

—so that the grandfather mightn’t have been blinded,

the river never dwindled to what it is now,

nor the leaning big willows above it been blighted,

nor its trout been fished out;

nor, by the naked boys, the swimming hole been abandoned,

dissolved, abandoned, its terra cottas and gilt …

If you like what you read, subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for just $99.

The Other Kellogg: Ella Eaton

Edward White’s monthly column, “Off Menu,” serves up lesser-told stories of chefs cooking in interesting times.

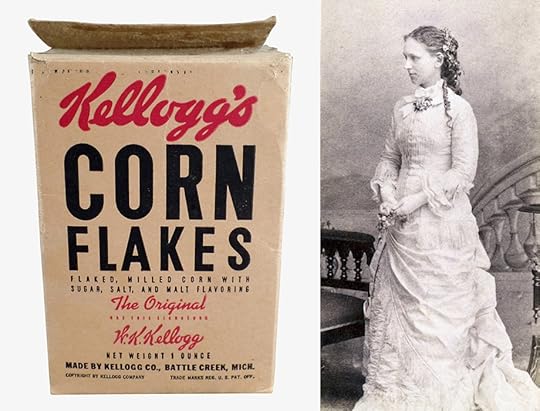

Original Kellogg’s cereal box (left), Ella Eaton Kellogg (right)

Few novels in American history have had the seismic social impact of The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s 1906 work set among the gore and misery of Chicago’s slaughterhouses. Though the critics were sniffy about Sinclair’s drum-beating prose, his vivid descriptions of the insanitary conditions inside America’s abattoirs caused an outcry that hastened the passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act. Despite the sales figures, Sinclair was only partially satisfied with the public reaction to his book. His aim had been to convert Americans to socialism; instead, he lamented, he had succeeded only in turning them into fussy eaters. “I aimed at the public’s heart,” he later wrote, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

1906 turned out to be a landmark year for both the American food industry, and American cuisine. While The Jungle was lighting fires in Congress, in Battle Creek, Michigan, William Keith Kellogg struck a deal with his brother John Harvey Kellogg that would begin a new, acrimonious chapter in the peculiar psychodrama of their relationship, and spark a revolution of the breakfast table. William bought from John full ownership of the company that produced their Toasted Corn Flakes, and swiftly turned a niche health food product into one of the biggest American brands in history, changing the diets of billions around the world.

Both these events, the regulation of the meat industry and the rise of breakfast cereal, were redolent of the Progressive Era of the early 1900s, in which it was assumed that a mixture of moral zeal and technocratic expertise could remedy all social ills, and alleviate individual suffering. But they are also wonderful examples of an unmistakably American approach to cooking and eating, what the academic Nicholas Bauch describes as “an obsession with getting food right … never being satisfied with the movement of organisms from nature to the eater’s body.”

In the Kellogg story there was one person in particular devoted to getting food right—not the flamboyant, egocentric John, nor the embittered, entrepreneurial William, but Ella Eaton Kellogg, John’s wife, one of the most overlooked but most important names in the ever-twisting story of America’s relationship with food. It was Ella who applied the Progressive mindset to a working kitchen, sowed the seeds of dietetics, and devised a new culinary philosophy for ordinary Americans which she outlined in 1892 with her book Science in the Kitchen. In her sober, efficient way—which perfectly mirrored the sober, efficient dishes she concocted in her kitchen—Ella bequeathed a huge legacy. Beyond the content of her recipes, which promoted vegetarianism and swore off refined sugar, she articulated the heady idea that perfecting food (and the systems in which it is created and consumed) is the key to perfecting human civilization. From Diet Coke to the Impossible Burger, America has long sought to perfect its food through scientific intervention. Few have gone at it as successfully as Ella Eaton Kellogg.

*

John and William Kellogg were raised in Battle Creek, Michigan. As a family of devout Seventh-day Adventists, the Kelloggs followed strict dietary proscriptions: no caffeine; no alcohol; no sugar; rules that would eventually become a point of great tension between the brothers. Though given little schooling—his parents favored preparation for the Second Coming over education—John had obvious intellectual talents and an irrepressible personality. At the age of twelve he was taken under the wing of Ellen White, a prophet and leader of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, who gave him the job of copy editor for the Review and Herald. In his early twenties, and with White’s financial assistance, he spent three years studying medicine at the University of Michigan, and Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York, before being appointed, in 1875, head physician at the Western Health Reform Institute, a clinic owned by White and her husband. Within a year he renamed the place the Battle Creek Sanitarium, and began to pursue his dream of turning it into one of the most famous health resorts in the world, a beacon of hygienic living that would improve the physical and moral health of America and beyond.

At this same moment, Ella came into his life. Raised in New York State, Ella is still the youngest person to receive a bachelor’s degree from Alfred University in New York, which she achieved at age nineteen in 1872. In the summer of 1876, Ella and her sister went to visit an aunt in Battle Creek. Soon after their arrival, Ella’s sister was stricken by typhoid, and received care from staff at Kellogg’s sanitarium. When Ella took over nursing duties she caught John’s eye, though it does not sound like love at first sight; he said he was struck by her “absolute reliability and responsibility” and “unswerving devotion to duty,” and convinced her to stay in Battle Creek to help deal with the typhoid outbreak and work at the sanitarium.

They had met at a crucial juncture. He was “struggling with the multitudinous duties” of trying to make the sanitarium the place of his vision, and she was looking for some stimulating outlet for her talents and ambition, somewhere beyond the classroom where she could make a mark on the world. They married in February 1879, and Ella swiftly became integral to John’s mission at Battle Creek. She took on writing and responsibilities at Good Health, gave regular classes in home economics, and became centrally involved in the Women’s Temperance Union. Though she and John never had children of their own, they fostered more than forty during their married life, and adopted nine of them, with most of the parenting duties assumed by Ella, who immersed herself in the latest theories of pedagogy and child rearing. She was also involved in the day-to-day operations of the sanitarium, though that was mainly the stage upon which John performed. It was he who oversaw the dance classes and exercise sessions, the electric light baths and the salt scrubs; it was he who took all the patients up to the roof at the end of each day and led them in a rendition of “The Battle Creek Sanitarium March.”

One historian has described John as having an imperious attitude to his family, treating the children “more like research subjects than beloved sons and daughters,” and Ella “more like a business associate than a wife.” John was certainly a single-minded man with an enormous sense of destiny. Even those close to him found him overbearing and capable of great selfishness. William, the younger sibling by eight years, worked at the sanitarium, supposedly in a senior role, though he felt constantly demeaned by his elder brother. In view of the patients, John frequently rode his bicycle in the sanitarium’s grounds giving dictation to John as he jogged alongside. Sometimes he even had William take instructions from him while John had one of his frequent enemas. “He was a czar and a law unto himself,” said William of his brother, late in life.

On the page, at least, John was capable of tenderness and gratitude toward his wife. “A constant inspiration,” is how he described Ella, “as well as a most efficient and congenial helper and companion,” though she was much more than his “helpmeet.” In addition to all her other activities, Ella was instrumental in creating daily menus for the sanitarium’s staff and patients that were both healthful and palatable, a feat John described as her “greatest single achievement.” For his first several years in charge, John had been frustrated that so many of those who sampled his design for living had balked at the food. Meals were served in strict accordance with John’s philosophy of “biologic living.” Meat, thought to inflame carnal appetites, was banned, as were spices, which the Kelloggs were convinced led directly to alcoholism. Dairy was permissible in certain cases, but refined sugar was rarely allowed. Raised on spartan fare, John had no problem foregoing flavor for healthfulness, but conceded that to most people “what was left after meats of all sorts, butter, cane sugar, all condiments except salt, pies, cakes, gravies and most other likable and tasty things were excluded … was a rather uninviting residue. New arrivals were usually very much dissatisfied.” Many found the diet so grim that a few establishments in town—including the knowingly named Sinner’s Club—did roaring trade with absconding patients in search of a good steak, a cool beer, and a long, lung-clogging smoke.