The Paris Review's Blog, page 151

August 21, 2020

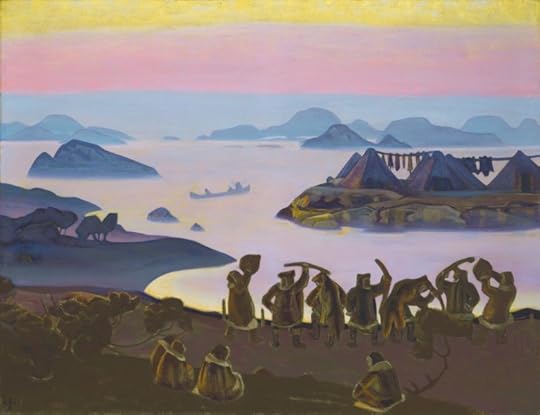

Staff Picks: Dictators, Deep Souls, and Doom

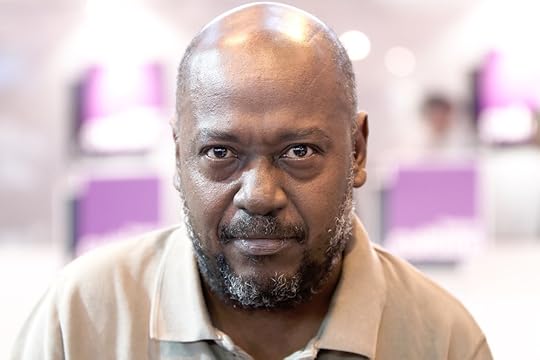

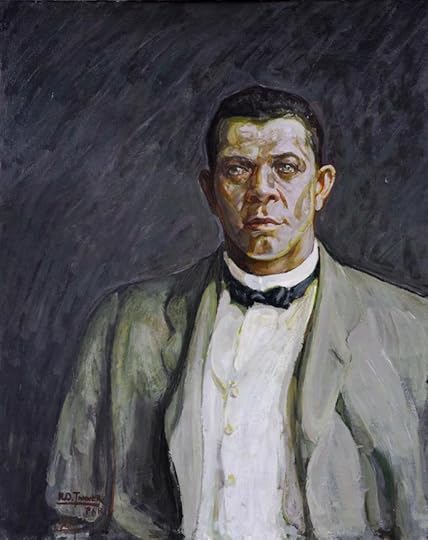

Lyonel Trouillot. Photo: Georges Seguin. CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...).

A sense of unease pervades the Haitian writer Lyonel Trouillot’s Street of Lost Footsteps, translated from the French by Linda Coverdale, as does a sense of political hopelessness. The novel charts, over the course of a single night, a violent uprising in Port-au-Prince against the dictator Deceased Forever-Immortal, told from the perspectives of three characters: a taxi driver, a madam in a brothel, and a post office employee. Central to the story is the problem of how one should approach the subject of political violence in a work of art. In language that does nothing to prettify—in fact, the poetry of Trouillot’s sentences serves to better underscore the horrors he describes—the characters navigate lives lived in a moment of grim uncertainty. “How could we have made love,” the postal worker asks his lover, “when we were perhaps already dead, uncertain of our own existence, even incapable of imagining the point of existence? … What do such pretty phrases have to do with the paralysis of terrified flesh, already absent from its own desires?” These are salient questions, questions that have no answers. “In the silence,” he continues, “the dream flowered in her eyes. In some way or another, we had led the night to us.” —Rhian Sasseen

It wasn’t until my four brief years living in Appalachia that I realized how distinct it is from the Deep South as a culture. Certainly, the two overlap and relate to each other in a number of ways, but you need only look at their landscapes to sense the difference: flat forests and swamps versus vast mountain ranges and swaths of coal country necessarily provide for divergent experiences. Appalachia’s struggles lie forgotten in comparison to those of the North, the South, and even the Midwest. For that reason, I urge you to pick up Leah Hampton’s F*ckface and Other Stories. The humor and the hardship of those mountains are imprinted in the very bones of this collection. The title story immediately grabbed me with its compassion and wit, and the rest of them continued to push the envelope by constantly reasserting the dignity of the populace alongside the political, economic, and ecological tragedy of the region. The stories work hard to reject “all the stories blaming mountain people” for America’s systemic problems but work harder to represent the complex reality of living in Appalachia. Ranging from a forest ranger’s marriage falling apart in the midst of ruinous fires and elections to a lovestruck woman’s vision of splendor in Dolly Parton—patron saint of Tennessee—each story envisions an especial view of the mountains. Oftentimes, my friends from the area would tell me quite grim stories about themselves or their families, but they would be laughing the entire time; Hampton captures this sensation to an incredible exactitude. And if it’s any indication of how enthralling and rich these stories proved to be, I finished eighty percent of the book in a single sitting. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

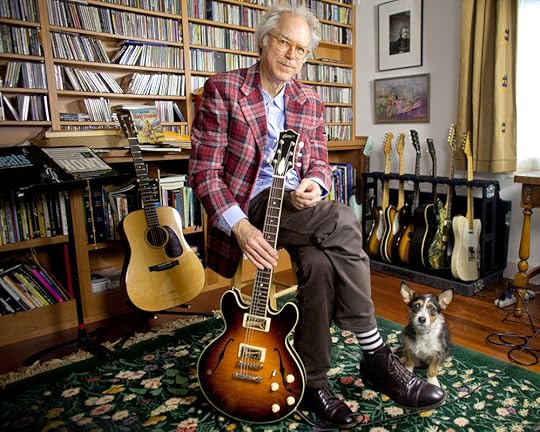

Bill Frisell. Photo: Monica Frisell.

Bill Frisell is one of my top three favorite living musicians, along with Joni Mitchell and a rotating third artist I can’t decide on today. The fact that so much sadness, so much joy, and so much humor can seamlessly coexist in one sensibility, one body of work, even one song, has always meant that I feel less alone in the world listening to Frisell’s music, lovers and haters be damned—which is to say I recognize myself, or something I aspire to, in his music. Out today is Frisell’s new album Valentine, featuring his current working trio with Thomas Morgan on bass and Rudy Royston on drums. Frisell has been playing with each of them for years, and both have appeared on many of Frisell’s recordings, but Valentine is the first record with this exact configuration. Morgan has one of the best bass tones in the business, like he’s playing an ancient, deep-souled redwood tree, or like if Nick Drake had been an upright bass player. Royston plays, at times, like a super-precise popcorn popper. With every new album—and there’s one or two every year—Frisell tries on a different mood, mode, genre. I sometimes want a “regular” Bill Frisell album, just his dreamy sensibility against a backdrop of jazz. That’s what Valentine is, and I’m really grateful for it. It mixes old and new tunes by Frisell and others; on ones he’s played a lot, like “Baba Drame” and “What the World Needs Now,” Frisell finds a deep groove, embellishing meaningfully everywhere, leaving space everywhere else, weaving a cohesive fabric with his partners. There’s a gorgeous version of “Keep Your Eyes Open,” a decades-old Frisell composition. And the album ends with a subtly triumphant rendition of “We Shall Overcome,” a gentle anthem for and against current events. All of which is to say that this is a great album, one of Frisell’s clearest statements in years. It won’t change anyone’s opinion about his music, but it may feel to many, as it does to me, like a much-needed visit from a dear old friend during a lonely time. —Craig Morgan Teicher

The second episode of Hulu’s High Fidelity, aptly titled “Track 2,” begins with Minnie Riperton playing as Zoë Kravitz describes the “delicate art” of making a playlist. There are rules, apparently—it can’t be too obvious or too obscure, it has to feel familiar but still surprising, it has to tell a story—that the show itself seems to follow. And certainly every song in every scene feels as intentional as a carefully curated playlist, as tributary as a love letter. Here, the soundtrack says, I made this for you. This invitational approach to music redeems the show’s characters, who otherwise could be seen as snobs. An early scene shows them playing “Come On Eileen” in earnest, off of a playlist that supposedly also contains Lauryn Hill. It’s not about what music you love, the show offers; it’s about how much you love it and how hard you’re willing to go. So an anticipatory energy hangs heavy above each scene as the music plays. An energy that feels like listening to a playlist, waiting to hear track 2 and so on and so on. A delicate art, a story. I’ll admit (albeit semi-ashamedly) that I’ve never actually read the Nick Hornby book the show is based on, but I’ve seen the 2000 film starring John Cusack, and barely any specific songs come to mind when I think of it. The opposite is true with this version. So when Hulu recently announced that the show wouldn’t be returning for a second season, the first thing I did was turn on its soundtrack. I wasn’t surprised to hear of its cancellation. All the best shows get only one season. But now I think of this one every time I hear Ann Peebles or Minnie Riperton or “Come On Eileen.” —Langa Chinyoka

In the 2016 video game Doom (which I wrote about a year and a half ago), hell is an energy drink, a panic attack, a condemned corporate office park in space. In the game’s 1993 forebear, also titled Doom, hell is a methodically mapped but no less nightmarish procession of puzzles. Booting it up for the first time on my Nintendo Switch, I expected to encounter a mere historical curiosity, something I might play for thirty minutes before setting it down for good. As technology progresses and game design develops alongside it, the classics become further enshrined in the dust of memory, barely scrutable to future generations. Instead, I was thrilled to discover that the joys of the original Doom require no footnotes, no scholarly preface; immediately, the player is immersed in a cramped, bloody, pixelated approximation of the netherworld and asked to shoot their way out. The early levels challenge the player to learn the game’s language; the later levels spit out whole paragraphs at once, demanding complete fluency, an innate, twitch-level understanding of how each demon behaves, how quickly a rocket can collapse a distance, how much everything, absolutely everything, can hurt. Nearing my fortieth attempt at a mission in the game’s fourth episode, “Thy Flesh Consumed,” I couldn’t keep my hands, and then my entire body, from quaking. Stress-induced tremors are perhaps not the usual mark of a good time, but I promise that in this case, they absolutely were. As you’re reading this, I’ve probably found my way back to the game once more, flitting through the fields of one-eyed cacodemons, ducking the volleyed flames of imps, dancing to the howls of the barons of hell. —Brian Ransom

Still from the video game Doom, 1993.

On Lasts

Jill Talbot’s column, The Last Year, traces in real time the moments before her daughter leaves for college. The column ran every Friday in November, January, and March. It returns for a final month this August, as Jill and Indie take one final road trip together to Indie’s campus.

© Matthew Lee High

Summer slips away, like so much else this year. It’s late August, midafternoon, and I’m sitting on a porch in upstate New York. This is the final week my daughter, Indie, and I have together on our cross-country trip to her new college. These days are the last ones before we say goodbye at her dorm, before we begin to unfold the pages of our separate lives.

*

Not long before we left Texas two weeks ago, I asked Indie if she’d like to take me on a tour of her favorite places in high school. She grabbed her keys and drove us to a doughnut store, to the turn she took so many times on Crescent Street, past her school parking space under a tree, to the restaurant where she had worked for over a year, to Sonic Drive-In, space 23, the one she and her best friend pulled into every time, and to the band practice field, telling me stories the whole way. At the Dairy Queen on University, she told me it had the slowest drive-through in town, but the best mint Oreo Blizzards.

*

At the final custody hearing in Boulder in 2003 (Indie was sixteen months old), the judge ordered the only visitation Indie’s father requested (five days every summer). He left the courtroom without a word. My parents had flown in from Texas, and together we watched him walk down the hallway and step into an elevator. As the doors closed, my father said, “Well, you’ll never see him again.” He was right.

*

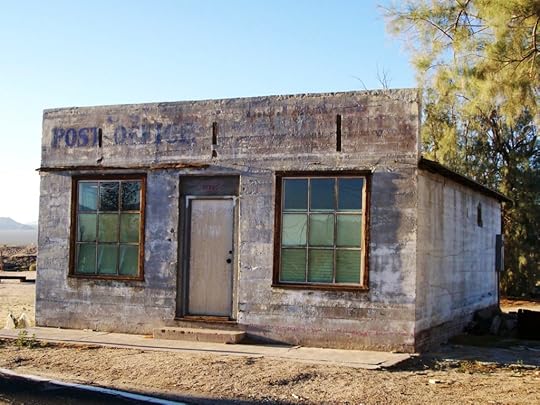

I’ve long been fascinated with a photo of an abandoned post office in the middle of the Mojave. The blue POST on the small building, the faded OFFICE. The two windows with blinds sun-stained to teal. The wooden door with 90820 painted in red above it. Who was the last person to pull that door closed, to check the lock and make sure?

*

In college I had an American-literature professor who liked to pose the question, What happens after the last page? I’d raise my hand to answer, my mind running wild at the idea of what happens after an ending.

*

When Indie was little and it was time to leave—a friend’s house or a playground—I’d tell her, If you don’t leave now, you can’t come back. I never had to tell her twice. The first time, she understood, was the last time.

*

Door Wide Open: A Beat Affair in Letters, 1957–1958 includes the correspondence between Jack Kerouac and Joyce Johnson that started the year On the Road was published. Johnson offers commentary throughout, beginning with the first sentence: “The night of our blind date in January 1957, Jack couldn’t even afford to buy me a cup of coffee—his last twenty had vanished earlier that day when he’d bought a pack of cigarettes and received change for a five, so I treated him to a hot dog and baked beans at Howard Johnson’s.” I tell my students they can often find an entire work in its opening line, and sometimes even the ending.

*

Last October, Indie and I went to the State Fair of Texas on the last day. We followed the route my father had taken us on every year—Fletcher’s Corn Dogs, the automobile building, the Midway for Skee-Ball, the food building for a bag of malt balls, a ride through the haunted house with the cars that swoop down a hill (my father, in his ball cap, always whooped on the way down). We did everything he had loved to do, along with giving our leftover game tickets to a family with small children on our way out.

This fall, there will be no fair.

*

As we’ve been driving across the country, we’ve seen CLASS OF 2020 signs on barns and marquees, once on a large rock in the Adirondacks. This year has given us all unexpected conclusions.

How many lasts came and went without our knowing? And how many lasts slipped away?

*

We’re quarantining at an Airbnb, our final stop before the four-hour drive to Indie’s campus. There’s a nice breeze on the porch today. A few houses down, a man mows his lawn.

Every night here, we’ve been watching a movie we loved when Indie was little (last night, Fantastic Mr. Fox). When the movie’s over, I come out here and listen to Jackson Browne. I’ve always loved the last lines of “These Days”: “Don’t confront me with my failures / I had not forgotten them.”

*

It turns out the last thing I bought my mother was a vanilla bean Frappuccino. She had never had one, and when she took a sip, she looked over at the nurse with joy: “It tastes like snow ice cream!”

*

On September 29, Indie and I sat high in the stands behind home plate at the final Texas Rangers game in Globe Life Park. I have a picture of Indie, about two years old, standing at the home plate gate in a pink shirt, jean shorts, and a blue Rangers cap. My mother took the photo. My father’s hand reaches for Indie’s in the frame. Last September, when Indie and I left the stadium, I showed her where the picture had been taken.

*

Every time I’ve moved, I’ve pretended the last time I see people is not that at all.

See you tomorrow.

See you soon.

I can’t bear to say goodbye.

*

This isn’t the last essay in this series, but it’s the last one I’ll write while Indie’s in the next room.

*

When her senior year began, I decided to keep fresh flowers on her nightstand. I enjoyed choosing different types, different colors, surprising her every week or so with a fresh vase. I thought of the flowers as celebration, but when everything shut down, they felt more like an apology, or an offering of grace. I let her pick out the last ones. They were cream roses, their petals like stationery.

*

I never leave behind the last sip when I drink wine in a restaurant. Yesterday, Indie told me she’ll miss sitting across from me in a booth, talking while I finish my wine.

*

“Everything that happens is the last time it happens.” —Sarah Manguso

*

I’ll always carry the look on Indie’s face when she turned to take one last look at our apartment.

*

If I were home, I’d read the final underlines I’ve made in my favorite books.

*

Earlier, the scent of rain was sudden. I looked up to see clouds fold away the last bit of sun like an envelope. The breeze cooled. And then a falling so quiet I had to stare at the trees to see the drops.

I threw open the screen door and called out to Indie. She ran outside, and we stood on the steps watching a rain that reminded me of the beaded curtains we once had in a kitchen doorframe, several homes and years ago.

*

I already know the last thing I’m going to say to her.

Read earlier installments of The Last Year here. Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t: A Memoir and Loaded: Women and Addiction. Her writing has been recognized by the Best American Essays and appeared in journals such as AGNI, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Ecotone, Longreads, The Normal School, The Rumpus, and Slice Magazine.

August 20, 2020

The Waiting Game

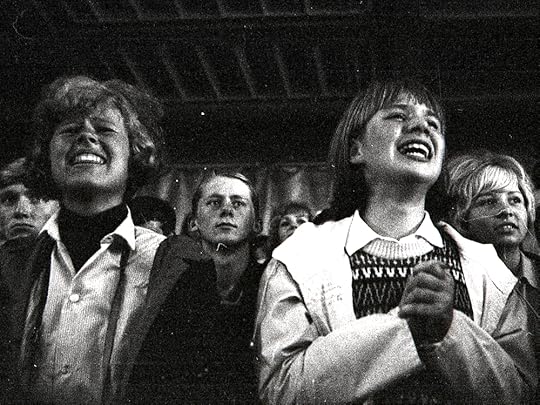

Rolling Stones fans in Norway, 1964. Photo: National Archives of Norway. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Teenage girls are yelping. It’s just after four in the morning and a huge rat—a heaving, greasy, small-dog-size thing—is dragging its weight along the pavement next to us.

“Eurgh, fuck off!” yell fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds, one pulling the cord of the hood of her sleeping bag tight so only her eyes are looking out. “You always see them this early, especially in London,” she says solemnly.

We’re all sitting or lying outside London’s Brixton Academy, one night in March 2017. Every ten minutes or so, girls arrive in darkness to wait for the pop-punk show happening the following night. Two friends, fifteen-year-old Lauren and fourteen-year-old Jess from across town in Bethnal Green, were already there at its steps when I shuffled over at three. They greeted me like I was another teen fan, not a writer in her midtwenties. “Come and sit down.” “Are you excited?” Their immediate assumption was that I was there for the same reason. They’d had waffles and whipped cream one of their mothers had made at about one and had been dropped off in her car. Both showed me their supplies for the night, day, and evening. Out of duffels come blankets, a full-size pillow, doughnuts, hair ties, makeup, portable chargers, money, exercise books, marker pens, T-shirts, CDs (very odd), phones, digital cameras, disposable cameras; enough for a camping trip. They are, I thought, camping, just with one of the ugliest backdrops I’ve ever seen. “We’re going to wait until security get here and set up the barriers and then we’ll sleep,” Lauren says. Along the grimy beige pavement down the left of the building, multiple girls are already passed out in sleeping bags like a row of wood lice, some savvy enough to bring foam mats. “Our mums didn’t mind us being here because it’s the last day of term.” She shrugs. “We’ll just say we’re ill or something.”

A girl wanders over timidly. “I was scared no one else would be here because I haven’t got friends to come with,” she says. Lauren and Jess welcome nineteen-year-old Simran onto their perch. Soon they’re chatting away about their favorite bands and talking the logistics of their joint mission. They’re annoyed because they don’t have signing tickets that allow you to meet the band. None could afford to be part of the exclusive paid-for fan club. “If I asked my dad to pay for that every month he’d probably laugh in my face,” says Jess. Simran empties a bag of mobile phones onto the pavement. “The things I do for bands,” she says. “Get all these fucking phones for a start.” They’re on various networks so she can get different priority tickets—the option to buy gig tickets a day or so before the rest of the general public. “I come to shows early all the time. I’ve never come more than two days early, though—until they get portable showers at venues I don’t know if I can do it.”

Over the next few hours, various groups play music off tinny speakers, knock back energy drinks, and share origin stories, not of their own life but of becoming a fan. One girl with bright blue hair, lying on her belly in a sleeping bag, is eating baby food from a jar. (“Hey! It’s only a fruit one, not weird, like a chicken one or anything!” she yells at me.) Quite a few need the toilet, including me, but the only nearby public ones are in McDonald’s, which opens at seven, so we collectively decide to stop talking about how much we could feasibly wet ourselves.

Through winter 2016 and early spring 2017 I’ve been waking up at two or three in the morning and taking the night bus across London from my Peckham flat to a music venue. I don’t know who I’m going to find but since there’s a pop or rock gig on the following night, the fans will be there, wanting to be first in. It doesn’t feel especially exclusive to any type of music, as long as the fan base includes a lot of them. When I say “them” I mean almost exclusively teen girls, since that is who I find every time.

The first time I did this, I arrived at a rock show a couple of hours early. Passing along the queue, I noticed a big group of laughing girls at the front chatting with a mother across a barrier. This would be the first of many times I met Bea and the others. This was a freezing cold night in February and Bea’s mother had brought them all hot chocolates. They only knew each other because they lived across the south of England and had met queueing for nights and days pre-shows. They told me that they did this for every show they went to, and they went to as many as they possibly could, regardless of artist. Since most young music listeners now are less bound by genre, many of the same faces were at shows as disparate as hardcore punk and bubblegum mainstream pop.

Waiting outside venues has been an integral part of the fangirl experience and something of an embodiment of their lifestyle from the very beginning. Columbus Day, New York City, 1944, a Frank Sinatra show, and the New York photojournalist Weegee was there when the first of the pop stars as we know them was about to take to the stage. “The line in front of the Paramount Theatre on Broadway starts forming at midnight,” he recalled. “By four in the morning, there are over 500 girls … They wear bobby sox (of course), bow ties (the same as Frankie wears) and have photos of Sinatra pinned to their dresses.” The three-thousand-seat house was quickly filled with girls waiting to see Sinatra for the first of his scheduled performances of that day. Apparently inside the theater the ammoniac smell of pee was heavy in the air because girls refused to leave their seats for food, water, anything, unless they were physically moved by attendants. Over the duration of the day, a riot bubbled over outside where, according to records, police had to deal with thirty to thirty-five thousand young female Sinatra fans, lining the streets around the theater, calling out to be let in.

Across the world, the practice has spread in astonishing ways. In Helsinki, Finland, during David Bowie’s 1976 tour, streams of girls who had been poised for hours outside his hotel propelled their arms through the open windows of his limo, hoping to get autographs as it passed by. London girls waited as his train pulled into Victoria Station ahead of his first shows in his home country in years, and some with multiple tickets stayed outside Wembley Stadium (then called the Empire Pool) overnight since he was playing a string of back-to-back dates. In Brighton, Bros fans—or Brosettes—in their bandannas and leather jackets and with packed lunches, sat from daybreak in the sea breeze before the 1988 Bros gig at the Brighton Centre. Decades later the same girls, who’d become women with families and careers, would wait in merchandise they had bought at those shows outside the O2 Arena for Bros’ 2018 comeback gig. High school girls with BRITNEY SPEARS IS GOD badges pinned to their chests came from all over California to watch Britney perform a few songs at the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium for her 2011 appearance on Good Morning America. Queuing from the early hours of the morning for more hours than she played songs was normal for Britney performances. In North Dakota, in 2009, teen girls waited through the night and even from the previous day, sleeping in the parking lot of the Alerus Center. Nicole Robertson, nineteen, and Beth Dennison, twenty, cuddled together on the tarmac for warmth. When asked by local media—who were there for a charming human-interest story—how long they’d been fans of Britney, Robertson answered with a sarcastic “Oh, please,” and added that they’d been fans since the nineties. This? For Britney? This was no sacrifice, of time or of comfort.

Later some sort of record was set in Rio de Janeiro. In 2013, Justin Bieber fans started queuing outside the Sambadrome a whole fifty days before his November 3 show. They constructed tents and took it in turns to sleep in this Belieber camp overnight. Before the authorities stepped in and banned under-eighteens from staying overnight, they had a brilliantly executed rota of names and times, like an efficiently run restaurant floor. Fans returned regardless, and local businesses were letting them use their toilets and showering facilities for a small payment. This effort was only to be bettered when Bieber returned four years later for his Purpose world tour. Camp Bieber opened five months in advance of his March 2017 date this time. Again, the 130 or so fans took turns to guard the camp, since they still had to pursue activities of a mundane nature, like going to school. One fan told the local paper, O Globo, “We are here for our idol and our love for him made us do this madness.” Madness, to most, but you can’t deny that commitment. It doesn’t feel like acts of individual delirium either, when girls want to do this together.

When waiting is thrust upon you, minutes and hours become prison bars across your current reality. Why wait, if there’s a choice, when our Western culture seems to be more and more about instant gratification, when a vegan tiramisu could be delivered to your door in the space of an hour or a taxi playing the music of your choice could meet you in five minutes? Both communication and validation are available in real time. Friends or lovers are even irritable if you haven’t replied to a message within the afternoon. We’re getting so bad at the skill of waiting that when we have to do so we find it utterly intolerable, anger inducing, sitting in it like it is a punishment. It doesn’t come naturally at all. As such, the younger you are, the more alien the concept becomes, and Gen Z, current teens, the first real digital natives, are frequently depicted as impatient and demanding.

The white band around the 1920s-built dome of the Brixton Academy the night I’m there reads ALL TIME LOW, the name of the band, in blue lettering. One girl has already taken a picture to share on social media but curses because it’s decidedly too dark. Lauren and Jess offer condolences. Era-defining and well-respected bands have played here before—the Rolling Stones, Nine Inch Nails, Alkaline Trio, the Clash, Blondie, Motörhead—making it one of London’s iconic rock venues. Whether tonight’s event will be written into the venue’s legacy or completely lost to history, it’ll have lasting meaning for everyone here.

Conversation turns to gossip about recent adventures in extreme queues. Fifteen-year-old pink-haired Nonny remembers her first. It was -3° C, snow and rain. They had to find somewhere warm or dry to sleep. She slept for a while under a bench, then was forced by security to move to a bus station, then a Tube station, dragging around her little sleeping bag. There were fifteen of them and they lay across escalators to go to sleep, before being told to move. “You’ve got to laugh at how bad your situation is. Scavenging for a toilet, security kicking you out of everywhere … We lost a girl at 4 A.M. or something. She just left. We were the first people there so we felt responsible. I’m like, ‘I’m fifteen! I have no idea what to do.’ I was so worried. We checked in the underground, all around the Tube. In the end she was in the toilets.”

One recent legendary wait was in honor of Twenty One Pilots, a group whose music has pulled in a die-hard fan base of young mainstream chart-pop fans. They played at Alexandra Palace on a Friday and Saturday in London, so hundreds of female fans camped all week. Notably mature eighteen-year-old Immy from Norwich was there that night. She sits slightly back from the others, smiling sagely, and speaks with confidence and clarity. She retells events: “One girl there had frostbite on her thigh. It was really bad, where she’d been laid on the concrete for three days and nights. I think she got taken away by emergency services.” Apparently, security had to bring in special cattle-pen-type barriers that none of them had seen before.

Another girl pipes up from inside her sleeping bag: “That was fun the first couple of nights but then when the younger kids got there it was so annoying. They brought ukuleles and kept playing Smash Mouth—‘All Star.’ I personally find ukuleles so cringey.” Ironically, only five minutes previously Immy and the others had vented frustration at older fans finding them immature.

What they’re describing, out of context, sounds like some sort of war zone. Being taken off to casualty, sleeping through turbulent weather conditions, minor altercations with security, rationing food. Once inside, it appears no better. A stampede, during which ankles are sprained and bodies fall down flights of steps.

You might wonder if there’s an element of hyperbole in these tales, but the exaggeration simply lies in the melodrama of the girls’ retelling, their grandiose gestures and the playing for laughs, as others shake their heads knowingly. Some of them offer queue stories that older teens once told them or that happened to their friends. What occurs when these girls wait passes into folklore; the only place these accounts are likely to be shared is on a pavement next to each other.

“On one of those nights, the amount of people who threw up in the crowd made me want to be sick,” says Lauren. I ask why and Immy says, “You get young kids who don’t understand that they need to hydrate and these are massive venues. It’s intense standing up and it gets so hot in the middle. They’ve not been drinking or eating enough throughout the days and nights if they’ve been waiting outside. They don’t think about it. Queuing people don’t eat.” Jess pipes up: “And the food inside is so expensive!”

There’s community feeling here between strangers or those who’ve met once or twice. Phones are used to document their time, play music, or give them more to discuss, like photos of them with their favorite artists—Immy proudly scrolls, showing me pictures of her with members of All Time Low’s support act—or videos of shows they were at. They’re not crutches: signs of social inadequacy or awkwardness. These girls are not inside, hiding away on laptops. Some are on camping chairs like a red-faced dad at a music day festival.

In the age of the internet where so much is done online, these spaces are the (albeit unauthenticated and sprawling) IRL fan clubs that don’t exist elsewhere. The waiting connects the public and private parts of fandom. Here the inner world of a person’s fan feelings meets their outside world; it’s both a personal and a group experience.

Eventually Bea arrives, to shrieks. Everyone knows Bea. She is a fifteen-year-old icon among fangirls of the south of England. She grins as she’s prancing over, her blond hair bouncing. I’ve seen her at multiple shows. Bea is always waiting.

Bea’s mother will get up at any hour of the day or night to drive her the three hours to London to leave her in the queue. She’ll entertain herself around town in the day, periodically coming back with anything Bea and the queue girls might need—blankets when it’s cold, sun cream when it’s hot. “My mum is such a legend,” Bea told me the first time we met. “Sometimes I’ll have concerts Friday, Saturday, and Sunday and she’ll drive me to all of them.” I asked her mother how long she’d been supporting Bea’s fan trips. “Oh, she’s been bossing me around since she was born. I have a half-term rule: no waiting before concerts in term time, but it never works.” Parents and mothers in particular are crucial to the plans because without them—the consent, the transport, the money—it wouldn’t happen.

In the hierarchy of fangirls, charismatic Bea sits at the top. She has tens of thousands of followers on social media through her frequent access to bands, shows, and waiting to get to the front row. This has come with its downsides—people pretending to be her friend for clout, people she doesn’t know finding out her where her school is. Once someone sent a necklace to her home address in the post, and none of her friends knew who it could have been. Girls will approach her like she’s a minor celebrity, having seen her at the front, tagged in barrier photos, or recognizing her from posting prominent pictures on social media. She’ll talk among fans about meet-and-greet tickets and back-to-back shows while others reply with barely concealed envy that they’d love to do it more but it’s too expensive.

For a lot of fans camping out and going to shows exist more as a semiregular treat than a central part of the music-fan lifestyle. Eighteen-year-old Lucia shares her frustrations with me. After meeting girls waiting at shows she’ll follow them on social media, and this is where comparisons are easily made. “You see these fifteen-, sixteen-year-olds getting to go to London and spending all their time and money on shows. It’s not their money, it’s their parents’ money. It’s all right if you have parents who also let you do what you want with it.” She considers herself just as much a fan, but recognizes that how she and many others are able to show that love and dedication is hugely dependent on wealth and social class.

I can sympathize. A significant teenage friendship had allowed me to have experiences as a fan I’d never have been able to have otherwise. No boat to the mainland, no gig tickets. I wouldn’t have been jealous of other fans, because I didn’t know many. But I did know what I wanted to have. Any inequality in the fan experience has been slightly lessened since the internet; before, the only way to hear music by your favorite artists was to buy records or CDs, which cost money. Now, music is instantly accessible for free. Yet it’s also thanks to the internet that fans like Lucia are hyperaware of any differences in the fan experience, ones they’d have been mostly ignorant of before. Hierarchies exist in every teenage social group. The barely visible distinctions based on who your parents are, the school you go to, what you can and can’t afford. Fandoms are no different, which is especially obvious when you start seeing the same faces at these gatherings. You realize who arrives at what time, who keeps appearing, whose voices are loudest.

“Oh hi, I haven’t seen you since that concert last month,” Bea says, hugging every girl in turn. She speaks very quickly and with high energy, following every trail of thought. “I need to sleep today. I went to a show last night and I haven’t slept, I’ve just carried on going and at some point I’m going to get really tired.” She’s arrived later than other girls but joins the biggest group right by the entrance to the venue. They’ve saved her a spot. When I catch up with Bea in a year’s time she will have followed Fall Out Boy on tour to every date with her mum, and flown to America to see them.

Hannah Ewens is currently the features editor and a writer at Vice. She writes about youth culture, mental health, music, and film for publications such as the Guardian and the Telegraph.

Excerpted from Fangirls: Scenes from Modern Music Culture , by Hannah Ewens, © 2020, published with permission from the University of Texas Press.

Leaving It All Behind: A Conversation with Makenna Goodman

I met Makenna Goodman last fall, after moving to a small town in Vermont near the college where I teach. When I say “small town” I mean it: we don’t have a stop light, there’s no restaurant or gas station, and no one really comes here unless they live here. Makenna is my new neighbor, across the road, and she threw me a welcome-to-the-neighborhood party that was the first anyone had ever thrown for me. It was also the last party I attended in someone’s house before quarantine. When Makenna asked me if I wanted to read her debut novel, I said yes, even though I feared the awkwardness that would ensue if I didn’t like it.

Luckily, The Shame is startlingly original, the story of a young woman in Vermont who leaves her husband and children to drive off in the middle of the night for New York, to meet a woman she is obsessed with, a ceramicist she knows only through the internet. Part of its pleasure is in the construction—the recursive loops through the mind of a woman who is breaking down from not making the art she absolutely must make. The structure feels both assured and free—free of so many of the anxieties I’ve seen in so many debuts over the years. I’ve seen a few of the recent reviews address that the narrator is a mother, and say that this is somehow a novel about motherhood, but I think of it as a novel about art and anxiety, and the narrator is a mother. More importantly, this is a novel about how you can feel driven to take risks that don’t matter in order to avoid taking the risks that do matter. How you will drive all night to meet someone you know only from the internet, but won’t sit down and make art. Most importantly, to my mind, it is a novel about the emotional labor of self-sacrifice, a portrait of how the white middle class eats itself, especially by devouring women, who are asked to prepare themselves like a dish to be served—and then to serve it too, as it were.

Makenna’s novel isn’t particularly autobiographical, but it is a bit like talking to her—like her novel, she is blunt and funny, and moves in any direction she wants. It was a pleasure to speak to her about everything from authenticity to social media to “connection.”

INTERVIEWER

I’ve gleaned that you wrote this novel in secret. Is that an accurate statement?

GOODMAN

You make it sound so mysterious and exciting. Yes, I wrote it in secret. I was deep in my editing career, I hadn’t been trying to publish anything, I wasn’t a professional writer. So, writing felt like this thing that was just for me, and I didn’t need to tell anybody about it. At a certain point, after I had finished the first draft, I said to Sam, my husband, Oh yeah, I’ve been working on this thing. I don’t know if it’s any good, and he said, Let me read it. We read very different things and have different taste, so I thought, Well, he’s going to hate it and that’ll be good. Because then he’ll tell me he hates it and then it’ll all be over. But then he said I should send it to my agent, whom I hadn’t talked to in years. And I was like, I don’t know, I don’t know. Okay. But I sent it to her and literally four days later, she wrote me back and she said, We’re sending this out. So, it was kind of traumatic.

INTERVIEWER

This is an interesting way to react. Traumatic?

GOODMAN

Okay, traumatic is probably too strong a word. Writing was a very personal process, very much about these deeply psychological questions. So to have it go from in my head to the hands of all of these editors was really frightening. And then to wait for their feedback. And then to get their feedback. It didn’t happen in the fairy tale debut-novelist way. I didn’t even realize what I was writing until they were telling me that it wasn’t right for them. To get critical feedback about how a piece of art will sell when you’re still raw from making it—I didn’t realize what a psychological challenge that would be. And also, I was very unconnected to the literary world at that time. Yes, I was an editor in Vermont, but my very small niche was agriculture. I was reading books on soil biology. I wasn’t aware of any literary news, of any trends. I didn’t check my email on the weekend, I had no social media. But still, I felt like, Oh, no, am I allowed to be a writer and an editor? I should be researching regenerative agriculture, not writing about these other things … Eventually these mind-states worked their way into the novel. It became this weird experience of learning how to trust myself. How do you locate the deeper confidence and belief in what you’re doing when the world may not understand it? Then my editor, Joey McGarvey, found me. She had faith in it.

INTERVIEWER

One thing that I think is so difficult about being a debut writer is that nobody ever explains to you that this practice, which was basically like a refuge for you, effectively becomes a public space. And it’s a deeply disorienting feeling.

GOODMAN

For me, the writers I’m drawn to are the people who write to an unanswerable space. It’s an existential question that is all about exposing the darkness and the shadows and the risk of being ridiculed and humiliated—these human emotions that feel so singular and individual, when they’re in your head. Like, I’m the only one who feels this alone. And I guess I had to write that way, because it’s how I want to live. And that’s even scarier, because a lot of the book is drawn from emotional experience. The characters aren’t the characters in my life, but still someone might read them that way.

INTERVIEWER

It’s interesting, it’s not really exposing something if it’s not your life, right? It’s more about opening up your life to the possibility of being misapprehended.

GOODMAN

Exactly—misinterpreted. And it gives away the power of deciding what’s true or what you meant or what you feel. I think the fear of criticism consumes a lot of people. To publish means you have to kind of put a bubble around yourself. I’ve found that, at least, and it’s ultimately kind of spiritual. But the book explores criticism as it weaves its way into our lives and identities.

INTERVIEWER

I suppose that brings me to, I mean, it is called The Shame. What was the inspiration for you? What got you writing your secret novel?

GOODMAN

I read this little book of psychoanalytic theory that was given to me by an astrologer years ago, whom I had seen in one of my prolonged quests for truth. It was written in the early eighties by this psychoanalyst who was talking about feminine, archetypal psychology and the Eros and Psyche myth. He deconstructed the myth as a metaphor for every woman’s coming into awareness. And then he broke down the myth, scene by scene, character by character, explaining it in Jungian psychoanalytic terms. This book somehow made things multidimensional in a way that was compelling. So often the myth is interpreted as a woman desiring a man and then the man rejecting her and then she wins back his favor and they live happily ever after. In this writer’s interpretation, all the characters were the woman. It was all about the layers of psyche and how projection fuels or hinders awakening. And I was just like, Yes, yes. Oh my God. A light bulb went off. I looked at my life as if it were a story. I was like, Okay, well, if I’m Psyche, Eros, the god of love, and her jealous sisters who don’t want her to be happy, and Aphrodite the goddess of love, who is this all-knowing, beautiful temptress who has all the power, if I’m all of these characters, then perhaps I can find the key to my longing?

At the same the time I was really bothered by social media and I talked about it often at dinner parties. I was bothered by how advertising had invaded my friends’ lexicon. Everybody seemed to be selling something to everybody else. Some of them were even paid to sell the thing and were sort of hiding it in quippy narratives (this became the “influencer”). And then the rest were selling things passively by just bragging about the things they had. Of course there is an important component of activism on social media; it is a tool for many things. But at the time I began writing, I was really focused on how it was the epitome of capitalism invading the individual space. I had just had my second child and I would take these long walks up our road, with her asleep in the little sling, and I would talk to myself. And through these conversations with myself came the book.

INTERVIEWER

Which novels do you gravitate toward when you read?

GOODMAN

I tend to gravitate toward novels that have been “rediscovered,” and also women in translation. I recently read Nella Larsen’s Passing, which was brilliant. I love Mieko Kawakami. I loved Vigdis Hjorth’s newest novel to be translated into English, Long Live the Post Horn!, which is, in a way, an ode to the postal service. I love everything she’s done. She’s a Norwegian writer, and it feels like I’m reading some back channel of my own mind. Not like, Oh, me and Vigdis Hjorth have so much in common, I can’t wait for us to sit down in Oslo, over coffee. But more like, there’s more of us out there. More of us who think this sort of way. I’ve also been getting into Caryl Churchill’s plays, the British playwright. I’m reading a lot about nonfiction about authoritarianism and anthroposophy. And I really love Annie Ernaux’s work. I came to her very recently. I couldn’t believe I’d never read her. Ernaux is considered a memoirist, although she rejects that. She calls her books novels, but they’re known as memoirs. And Vigdis Hjorth has been accused of writing autofiction.

INTERVIEWER

That must be so annoying.

GOODMAN

Isn’t it? She said it’s a novel, guys! Does it make it more titillating and sellable if it’s really true? Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament created such a scandal in Norway that her sister wrote a rebuttal novel, and she isn’t even a novelist. She wrote a novel to dispute the veracity of Vigdis Hjorth’s novelistic fictionalization of their father abusing her. When you could just as easily interpret Will and Testament as a novel about not being listened to, being misinterpreted, and the shame of trauma, which is actually such a universal feeling. Even in the U.S. media, everyone seemed to wonder, Is it Vigdis? Is it Vigdis? Was she abused by her father? But it was a novel! The whole point is that she’s asking us to look deeper into society, not about the facts of her life.

INTERVIEWER

One thing that I think happens with the autobiographical tag, accusing a novel of secretly being a memoir, is that it becomes a really easy way to stop talking about what a book is about. It becomes a game of, Did this really happen to her? Did this really happen? And not, Look at what she’s saying about the culture in the novel. Which is the whole point of writing a novel.

How did you end up editing books? What was the path to becoming an editor at a small publishing house in Vermont?

GOODMAN

After college, I lived in New York and I was trying to get a job. I wrote for some independent art magazines and I wrote film reviews. One of these free dailies put me on the rape-revenge-movie beat, which I didn’t even know was a genre. And it was so deeply horrifying to me, but I had to stay until the end of all of the movies because I had to write the fifty-word review. Eventually I thought, If this is writing, I can’t do this. I couldn’t get a job at any restaurant because I didn’t have that much restaurant experience. And I heard from a friend that an editor needed an editorial assistant. I applied and got the job. I worked at a big-five house as an assistant for a year, then I moved over to the agenting side and worked for a literary agent for less than a year. In 2008, I moved to Vermont. I couldn’t work in publishing in New York anymore. I wasn’t competitive. I secretly wanted to be a writer. I didn’t think I had it in me to be an agent. It just seemed so impossible. The hierarchy, everything. Every day I would sit at my desk and I looked the wrong way, I dressed the wrong way. I remember I wore cowboy boots every day. That wasn’t great in corporate publishing.

INTERVIEWER

Really?

GOODMAN

Oh yeah, totally. All the assistants were like J. Crew catalogues, high heels or flats. They were diminutive and racing around, frightened for their lives. Maybe this was only at the places that I worked. Anyway, I had grown up mostly in Colorado, and I would Google image search the Rocky Mountains all day and just stare at them. But I wasn’t going to quit my job because it was a good job. And finally, I lost my job. I lost my job on a Friday evening and Saturday I had a train ticket to come up to Vermont. I went to a semester program here in high school and one of my teachers had died, so I was coming back for the memorial. And Sam was there. He had built the man’s deck.

INTERVIEWER

Wow.

GOODMAN

We had already met a couple summers before when I worked on a farm here. So now I was in Vermont, I had no plan, I had no money. I had debt. It wasn’t that much debt, but still, I had no idea what I was going to do. I was about to work, finally, at a restaurant! I was going to work at a diner and I was so excited because they had the best cheesecake. And then I saw there was a radical small publisher nearby. They didn’t have a job opening but I reached out, and the publisher hired me anyway. I quickly became an editor and then I stayed for eleven years. And it was a great experience, because we weren’t really connected to the rest of the publishing world. We were an independent house, we were super niche, we were mission-driven. We didn’t offer big advances, and so we didn’t work with a lot of agents. So it didn’t feel like traditional publishing and all of the authors that I was acquiring and working with were all practitioners who all taught me something I wanted to learn. I was learning about soil biochemistry and raising animals while doing the exact same things at the same time on our homestead. It was just this immersive decade where I was reading only about agriculture, growing food, and integrative health. I was completely immersed in agriculture, at home and at work. And I loved it.

INTERVIEWER

We see all these people gardening now, myself included. People have talked a little bit about why they are turning to this during the pandemic and the subsequent collapse of the American government. Do you have any sense of why they would?

GOODMAN

That’s a good question. Probably part of it is the fear that we will not be able to procure food in another way and so we better get to gardening and raising our own chickens. We were trying to order chicks in March, and they were all out, which has never happened before. I don’t know if you know this, and maybe the readers don’t know this, but the way that you get chicks is you order them through a hatchery and then they send them through the mail. They send incubated eggs through the mail, and the chicks hatch on the way, and the post office calls you and says, They’re here.

But also gardening is beautiful and spiritual. It’s amazing to work the land and to connect with the earth. Energetically, it’s grounding. Scientifically, it’s literally grounding. Like if you walk barefoot outside, there is a balancing action. The earth has a negative electric charge and when you stand with your feet on the earth, there is energetic harmony. Whereas if you wear flip-flops, the rubber insulates you from that electric charge and so you don’t experience the same connection to the earth.

INTERVIEWER

I did just go outside and stand barefoot on the grass as you were saying that, to see if I could feel it. It’s interesting because the back-to-the-land movement was one of the more recent countercultural movements that lasted long enough to become, I guess, almost even a potentially conservative position, like formerly radical. Is it still radical, do you think?

GOODMAN

Oh, that’s such a good question. I’m very interested in the back-to-the-land movements. The one pioneered by the Nearings in the thirties, the early back-to-the-land heroes who wrote a book about how the simple life is where the true answers are, how all you have to do is work hard and then you shall flourish. Then there were hippies in the sixties, intellectuals and educated people who often had means, and yet most of them went back to the cities or where they came from. I’m friends with a lot of the people who did stay. And regardless of where they came from originally, they’ve lived close to nature for many, many years. Even though they live in a kind of bubble, they live intentionally. In the past there has been a rise of young, branded, educated farmers—the ones with really great T-shirts and Instagram accounts. Now, in this moment of capital, farming is considered an okay thing for educated, wealthy people to dabble in. Like, it’s okay for these kids to work a summer on the farm in between high school and college. Their parents are okay with that. In the sixties, it seemed to be more about self-reliance and moving against the oppression of the fifties. People were going to live in the middle of nowhere, away from it all, to learn how to dye their own clothes and bake their own bread. But in this era of late capitalism, people buy up old farms and instantly have a product and a brand. It’s not about self-reliance, but more about operating within and succeeding within the market. And it feels like a little bit of a lie. For example, everyone sees Vermont as this bucolic place, just dotted by small farms. And that’s what it used to be. But now most of those farmers have been completely bankrupted. The farming industry here is mostly self-sustaining home farms or ecotourism. And maybe it’s the image of bucolic bliss, but that’s not the economic reality of agriculture for most people. So I do think the back-to-the-land movement now feels like it’s hiding behind a mask, in a way. Then of course there’s the land grabbing happening post-COVID, where people are buying whatever they can in rural areas right off the internet.

INTERVIEWER

Do you want to say anything about the new book, or—

GOODMAN

I’m still in the moment of not one person having read it at all, ever. Not one word of it.

INTERVIEWER

So don’t describe it, then, let it be a secret, too.

GOODMAN

I will say that it explores the ethical underpinnings of land and who gets it, who’s gotten it, who receives the fruits of whose labor, and who doesn’t have even access to that labor. And also the idea of escapism and fleeing to the rural parts of the world—who can do that and what that means. I’m interested in class, and the idea of who gets to be in nature. Who gets to “claim” nature.

Alexander Chee is the author of, most recently, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. He teaches at Dartmouth College.

An Inheritance of Loneliness

In this series, Quarantine Reads, writers present the books getting them through these strange times.

Quarantine has made me a lonelier woman, but I’ve always held the inheritance of another woman’s loneliness. When my mother was in her early twenties, she left her mother’s house in Bangalore to move to New York City, where her new husband—my father— had been living for the previous few years. It was her mother, my grandmother, who arranged the match. My grandmother was thrilled to send my mother to America, even though my mother didn’t want to marry and didn’t idealize coming to America the way her mother did.

You can be happy anywhere, unhappy anywhere, my grandmother told her. The two of them had a mother-daughter relationship like something out of a Jamaica Kincaid novel: loving but contentious, fraught with discipline and warnings about the difficulty of being a woman.

My mother remembers her early life in New York as a kind of self-quarantine. While my father worked, she spent her days isolated in their tiny studio apartment, going stir-crazy, cooking and cleaning and staring at the clinical white walls. A gossipy relative back home had spooked her into believing she’d be assassinated if she opened the front door in America. Occasionally, she spoke to the women holed up in the neighboring apartments. But most of her downtime, my mother spent sleeping. She slept purposefully and often, trying to reenter her old life in her dreams: the long walks with college girlfriends to the pani puri truck, the yipping of a neighbor’s Pomeranian, the pulse of life as an unmarried woman, alive with vagary and freedom. My mother resented her mother for marrying her off. They spoke once a month, on an international call, during which they’d argue about fate. And then my mother would hang up, miss her mother, and sleep away some more of her time.

Experiences like my mother’s are commonplace for many women. They’re often fictionalized and folded into novels about immigrant experiences, novels many readers from immigrant communities have grown tired of. Can’t we tell stories other than the one about coming to America and assimilating? And yet, those narratives have a pull for me—they contain the stories about women’s loneliness that have always absorbed me.

I’ve read Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy over and over. It’s the novel I turn to when I crave the order of a book I have loved before. First published in 1990, Lucy is about a young woman who leaves her home in the West Indies to work as an au pair for Mariah and Lewis, a well-to-do white couple in the United States. At first glance, Lucy seemed to me like the kind of novel I am built to love: I had always wanted to be a woman rising, and so I liked stories about women rising. Lucy’s premise suggests a narrative about social ascendance—a young, wage-earning woman, a modern governess type who pulls herself up by her bootstraps. It seems, on the surface, to promise to be another immigrant bildungsroman, charting the arc of a young woman’s maturation into a society where things like bootstraps are celebrated.

But Lucy doesn’t care about ascendance or assimilation. Kincaid doesn’t concern herself with a woman becoming, but rather with a woman being. How does a person get to be that way? Lucy wonders, over and over again. What she wants to be—all she wants to be—is alone. She wants to isolate herself before society seizes the chance to isolate her. Solitude is an act of self-preservation, whereas loneliness can be an act of violence, and so every choice Lucy makes is in pursuit of solitude. She chooses to leave her island behind. She chooses to leave her mother behind, a mother who, for all the ferocity of her love, raised her daughter with the same patriarchal hand that had raised her.

Once in the States, Lucy ignores the stack of letters her mother sends her, all the notes of love and punishment and longing. She comes to love her employer, Mariah, like a mother figure, and the two form a bond despite the chasm of their class difference. “The right thing always happens to her,” Lucy says of Mariah. “The thing she always wants to happen, happens.” After Mariah’s marriage breaks apart, Lucy stands by her. But the gap between them widens, and eventually Lucy saves up enough funds to leave her proxy mother, too. With the money she’s made as an au pair, Lucy and a friend move into an apartment together and split the rent. There, her solitude found at last, she finally writes back to her mother. She intentionally signs off with the wrong return address, severing their correspondence forever. But even in her apartment, with its tiny rooms and its barred bathroom window, Lucy isn’t free of her mother. Her mother’s voice lives inside her—it’s Lucy’s voice, too. Lucy is made up of two women: herself and her mother. “I was not like my mother,” she says, “I was my mother.” No one who contains multitudes is ever quite alone.

As I sit, alone, through quarantine, it’s my fourth time rereading Lucy, but I still remember my first. I was in college, and my professor introduced each novel we studied with a chalkboard quote culled from another novel. For Lucy, that quote came from George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Eliot writes, and I have never forgotten:

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow, and the squirrel’s heartbeat, and we would die of that roar that lies on the other side of silence.

The quote arrives at a point in Middlemarch when the heroine has just married. She’s crying on her honeymoon. Her new husband, of whom she wanted to be an equal, has relegated her to the position of an assistant. The heroine’s pain is visceral—the claustrophobic friction of a marriage, the realization that a man is what he always was—but it’s also ordinary, and Eliot’s shrewd narrator knows that readers don’t sympathize with ordinary pains. To sympathize with the ordinary would be impractical; it would mean feeling too much.

In solitude, Lucy sees the world with that keen vision and feeling. The ordinary moves her; she sees it down to a depth that others don’t. Some of those depths are painful: I think of a moment when Mariah asks Lucy if she’s seen daffodils before. To Mariah, the flowers are just pretty spring flowers. But Lucy can’t appreciate them. To her, daffodils mean growing up on an island that was also a colony. They mean the time at Queen Victoria’s Girls School, when she was made to memorize an old British poem celebrating daffodils. They mean being made to recite that poem aloud, the sound of imperialism ringing out from her own mouth.

And then some of those ordinary depths are beautiful: on a trip to the lake with Mariah and Lewis, before the family parts, Lucy meets a boy who piques her interest. They talk and later hide away behind a hedge of wild roses. The boy is ordinary and kisses Lucy all over with his “ordinary mouth.” Still, Lucy enjoys their intimacy more than with any man before him. His kisses aren’t just kisses, but metrics of how much Lucy misses home, of how long it’s been since she’s been touched and kissed.

“I was not happy,” Lucy admits at the end of the novel, in the solitude of her bedroom, having successfully left behind all the women and men she loved. “But that seemed too much to ask for.”

These past few months, I’ve done the journey so many of these women have in reverse. I’ve left my life in New York City and returned to my mother’s house. It’s the same house in which I grew up, an hour south of the city, where my mother and father moved after packing up their studio in Queens, one daughter then little, one daughter on the way. I spend my days sleeping away the hours in my childhood bedroom or going stir-crazy to the sounds of the squirrel’s heartbeat and the grass growing, the washer thrumming and the slow thuds of the boxes that pile up outside our front door. Sometimes I hear the sound of a woman grieving under my sheets. And then my mother knocks. “Why are you crying?” she demands. And I want to tell her that I’m unhappy, but that seems too much to ask for. Instead I ask her, as she turns to leave—Aren’t you lonely? And she just shrugs, an expert where I’m only an amateur. “I was lonely like this before,” she says. “Only difference now is that the world is lonely with me.”

August 19, 2020

My Cephalopod Year

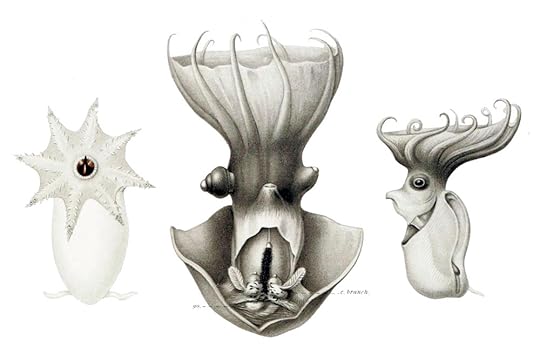

Ewald Rübsamen, Vampyroteuthis infernalis, 1910. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Way down deep, in the perpetual electric night of the water column—a place where sunlight doesn’t register time or silver filament—the vampire squid glides in search of a meal of marine snow. These lifeless bits of sea dander are actually the decomposing particles of animals who died hundreds of feet above the midnight zone. The vampire squid reaches for this snow with two long ribbons of skin, which are separate from its eight tentacles. If it is truly hungry, it trains its large eye on a glow, the lure of something larger—a gulper eel, perhaps, or an anglerfish waddling through the inky water. The squid’s eye is about the size of a shooter marble, but this is nevertheless the largest eye-to-body ratio of any animal on the planet.

If the squid feels threatened or wants to disappear, perhaps no other creature in the ocean knows how to convey that with a more dazzling yet effective show. When the vampire squid pulse-swims away, each of its arm tips glow and wave in different directions, confusing for any predator. To make an even more speedy getaway, the squid uses jet propulsion by flapping its fins down toward its mantle and simultaneously blasting a stream of water from its siphon—all of its arms in one direction. In the next stroke, the squid raises all of its arms over its head in what is called a “pineapple posture.” The underside of these arms is lined with tiny toothlike structures called “cirri,” giving an appearance of fangs ready to bite down on anything that wants to chase it down for a snack.

As if that wasn’t enough to shoo away a predator, the vampire squid discharges a luminescent cloud of mucus instead of ink. The congealed swirl and curlicue of light temporarily baffles the predator, who ends up not knowing where or what to chomp—while the vampire squid whooshes away, meters ahead. It’s as if you were chasing someone and they stopped, turned, and tossed a bucketful of large, gooey green sequins at your face.

I wished I was a vampire squid the most when I was the new girl in high school. We had moved around for so much of my childhood, but the most difficult move I ever made was between my sophomore and junior years. I moved from a class of about a hundred students in western New York to well over five hundred in Beavercreek, a suburb of Dayton, Ohio. I went from sophomore class president to a little no one, a gal who tried out for the tennis team not because I had any interest in the sport but because at practice, at least, I didn’t have to be alone. I ate lunch in the library. I ate lunch in a stairwell hardly anyone used. I ate lunch in the dark enclave of the only elevator, hidden outside anyone’s eyesight, except for the occasional student on crutches or in a wheelchair. Once I ate lunch—my sad peanut butter and jelly sandwich—while standing up in a scratched and markered-up bathroom stall. To pass the hour, I read the often vulgar, sometimes funny graffiti scrawled on the stall door, just so no one could see that I had no one to talk to.

This was my cephalopod year, the closest I ever came to wanting to disappear or sneak away into the deep sea. I had never feared the first day of classes or meeting new people before. After tennis practice, when everyone else was making plans to meet up at the local pizza parlor, I made myself vanish. I don’t know if my teammates even noticed, or wondered where I went.

Oh, I didn’t finish high school like that, swimming in darkness. I did end up making friends, giggling with them in the back of the school bus. I joined a bunch of delightfully nerdy pals on the speech and debate team, and I eventually made the varsity tennis team, playing doubles at the district level with my sister. There was no hiding anymore. People noticed when I had to leave parties early for my curfew. They didn’t want me to go. And I had a teacher—Ms. Harding—who wanted me to shine. I know it sounds incredibly precious, but these friends made me believe the mantra “If one of us does well, we all do well.” They were generous with their support. Playing it cool was boring. They were my kinfolk, my people—many of whom I’m still friends with today, though we’ve scattered across the country, spilling out in different directions as fast as we could once we’d tossed our graduation caps in the air.

But there wasn’t one specific turning point where I stopped trying to disappear. I don’t know how I wiggled out of that solitude, how I made it through the darkest and loneliest year of my youth. No more of those half-eaten lunches hurriedly tossed into the trash. No more make-believe “research” I pretended to do so the librarian would just let me read in peace. Instead, I began scribbling in notebooks and notebooks, trying to write my way into being since I never saw anyone who looked like me in books, movies, or videos. None of this writing was what I would remotely call poetry, but I know it had a lyric register. I was teaching myself (and badly copying) metaphor. I was figuring out the delight and pop of music, and the electricity on my tongue when I read out loud. I was at the surface again. I was once more the girl who had begged my parents and principal to let me start school a whole year early. And I was hungry.

I emerged from my cephalopod year, exited my midnight zone. But I’m grateful for my time there. If not for that shadow year, how would I know how to search the faces of my own students? Or to drop everything and check in, really check, with each of my sons when they come home from school, to make sure they are having a good time and feel safe? If not for that year where no one talked to me on the school bus, where I had no valentines, no dates, I wouldn’t know what to say to my student with the greasy backpack, who sits in the corner by herself and doesn’t make eye contact. Who never talks in her other classes and never spoke in my class unless called upon. I wouldn’t know how to tell if her solitude is voluntary or if it covers up a hunger to be seen, to glow with friendship like I had every other year. I secretly love the audacity of her tousled hair, stacked into a giant sloppy bun on top of her head—this student who constantly shuffles in late and is the last to leave but always, always reads ahead on the syllabus. The one who tells me after I come back from being out sick with the flu for a whole week: I missed you, I am so, so glad you were here today.

Me too, I say. And I mean it. I wouldn’t know how wide and how radiant a student like that could make me smile.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is the author of four collections of poems, including, most recently, Oceanic, winner of the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Award. Other awards for her writing include fellowships and grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Pushcart Prizes, Mississippi Arts Council, and MacDowell. Her writing has been anthologized twice in the Best American Poetry series and appears in Poetry, The New York Times Magazine, ESPN, and Tin House. She serves as poetry faculty for the Writing Workshops in Greece and is a professor of English and creative writing in the University of Mississippi’s M.F.A. program.

From World of Wonders , by Aimee Nezhukumatathil (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions.

Periwinkle, the Color of Poison, Modernism, and Dusk

Claude Monet, Water Lilies

On a stretch of rural road not far from my house, there is a small wood where, once a year, for just a few short and cold days, the ground turns a magnificent shade of purple. In a reversal of fortunes, the stand of gracious Maine trees becomes secondary to the ground cover below. When the periwinkles are blooming, it’s hard to have eyes for anything else. The delicate mist is an impossibly soft color, like clouds descending into twilight, like the snowfall in an Impressionist masterpiece. It’s a color that almost doesn’t belong here—it’s a plant that certainly doesn’t.

Periwinkle goes by many names. You might know her by one of her more fabulous monikers, like sorcerer’s violet or fairy’s paintbrush. In Italy, she is called fiore di morte (flower of death), because it was common to lay wreaths of the evergreen on the graves of dead children. The flower is sometimes associated with marriage (and may have been the “something blue” in the traditional wedding rhyme), sometimes associated with sex work (because of its supposed aphrodisiac properties) and also with executions. I grew up calling her vinca, a pretty little two-syllable name, taken from her proper Latin binomial, Vinca minor. My mother cultivated periwinkle in our forested Massachusetts backyard, encouraging the hardy green vines to trail over the boulders and under the ferns. I would have been delighted to know even a fraction of vinca lore back then, but I knew nothing except she was poison. I could eat the royal-purple dog violets, but I was not to pick the vinca. Vinca was poison and poison meant death.

This, it turns out, is false. It’s one of the many easy assumptions of childhood. I thought all plants that grew in my yard were meant to be there, and I thought all poisonous things were bad. Vinca—or periwinkle or creeping myrtle or dogbane, as she’s also called—is invasive to North America. It chokes out other plants, stealing too many nutrients for native ground cover to grow. Many New England gardeners do not plant it for this reason. Yet I grow it, partially because I know what it can do, what it has done.

Charlotte Berrington, Vinca Minor

Vinca contains alkaloids, which can be terribly bad for you if ingested in the form of a flowering vine. If you’re a dog and you munch several vinca vines, it could kill you. But let’s say you have cancer. Let’s say its lymphoma and you’re my husband and I can’t imagine the world without you, can’t imagine what would happen if the small, hard tumors nestled around your collarbone took your life. For three hours every two weeks, you go and sit in a room with other patients, other sick people who have lost their hair and their eyebrows. Together, you get alkaloids injected into your veins. You live because there is a medicine made from Madagascar periwinkle (a close relative of Vinca minor) that can kill cancer cells and cure your blood disease. You live because something poisonous can also be healing, an invasive species can also be curative—for a landscape and its people.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Madame Monet, ca. 1872–74

Vinca is a complex little plant, and periwinkle, named for its blossoms, is an equally complex color. A subset of violet, which is a subset of purple, periwinkle denotes a precise shade that appears somewhat brighter than lavender, bluer than lilac, clearer than mauve, and dimmer than amethyst. But it’s hard to say with precision, because the purples are strange ones, polarizing, and violets are even more so. Few hues are more beguiling and more reviled than this grouping, the last stop on the rainbow and the tacked-on v at the end of that schoolchild’s mnemonic, Roy G. Biv. According to the scholar David Scott Kastan, shades of violet exist within their own special category. Violet is, like glaucous, a color-word that denotes a certain quality of light. “Violet seems to differ from purple in whatever language—not so much as a different shade of color than as something more luminous: perhaps a purple lit from within,” Kastan writes in On Color, his 2018 book on the subject. “Violet is the shimmering, fugitive color of the sky at sunset, purple the assertive substantial color of imperial robes.”

This latter kind of purple—reddish, bold, saturated—has been bedecking the backs of the rich since its discovery by the Phoenicians, who were milking snails for their secretions long before the Common Era began. Known as Tyrian purple (supposedly for Tyre, in present-day Lebanon), Phoenician red, or imperial purple, it even has a heroic myth about its “discovery.” According to Roman scholar Julius Pollux, Hercules’s dog was the first creature to discover the pretty color hidden under those predatory shell-dwelling creatures (Peter Paul Rubens painted his vision of this event in Hercules’s Dog Discovers Purple Dye). Hercules had been on his way to court a nymph named Tyro, and when he got to her abode, she took one look at the stained dog and asked for a gown the same color as his mouth. Thus, Hercules was granted the glory of “inventing” Tyrian purple. The nymph, meanwhile, went on to get raped by Poseidon. (“And by the beach-run, Tyro, / Twisted arms of the sea-god, / Lithe sinews of water, gripping her, cross-hold,” wrote Ezra Pond in the Cantos.)

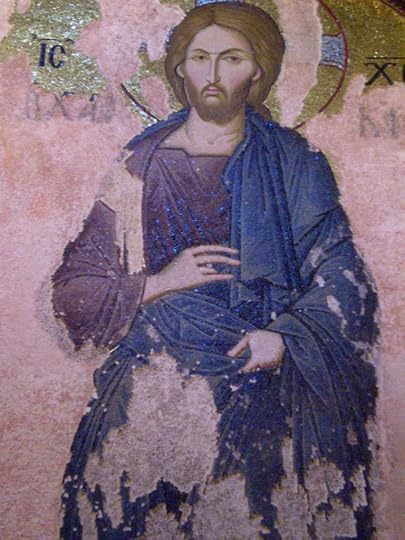

Christ, Byzantine Mosaic, 1320

Tyrian purple was a difficult color to manufacture. Thousands of snails were required to create a single ounce of dye. In first-century Rome, a pound of Tyrian purple cost “about half a Roman soldier’s annual salary, or the equivalent of the cost of a diamond engagement ring today,” according to a 2019 exhibition from the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology at the University of Michigan. While it was possible to mix other dyes and pigments to create shades of purple, Tyrian remained the most significant color until the invention of “mauveine.” This, too, was an accidental invention, though we have more documentation about the creation of mauve than we do of Tyrian purple’s. In 1856, teenage chemist William Perkin was attempting to create quinine for a university assignment when he discovered his black, tarry mess had a purple tint. He patented the formula and soon it became the first chemical dye to be mass-produced. Samples of the early mauveine dye show it to be a bright reddish purple, vivid and intense. It is a bit less brown than Tyrian purple, but it clearly exists in the same color family. It’s a purple, a true one.

According to the historian Sarah Lowengard, author of The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe, “modern American English” tends to consider purple and violet synonymous, “as simply red plus blue.” But that wasn’t always true: “In eighteenth-century conventions, purple has more red (r + r + b) and violet more blue (r + b + b); one can have light and dark violet as well as light and dark purple.”

Claude Monet, Impression, Soleil Levant, 1872

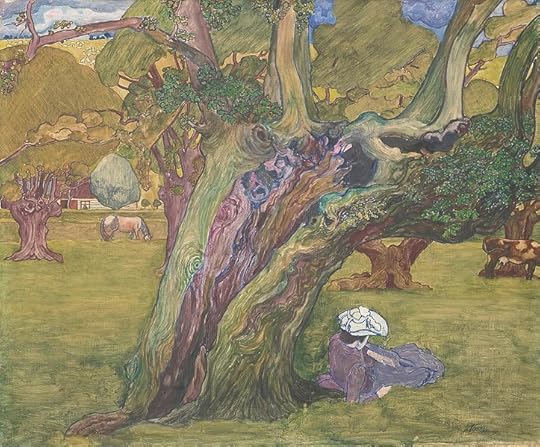

Violet was deeply significant to the impressionist painters of Europe—and deeply offensive to their critics. Kastan pinpoints Monet’s Impression, Soleil Levant (1872) as the inciting incident in the critics’ war against this artistic use of the shade. “Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape,” wrote Louis Leroy after his eyes were subjected to the wishy-washy scene.

It’s a painting of the ocean, but it’s a painting about color. It’s about misty gray blues and light violets. The same could be said for Monet’s Water Lilies series or Pissarro’s winter landscapes or Renoir’s crowd paintings or even J. M. W. Turner’s turbulent marine paintings. The more adventurous art galleries in 1870s Paris were filled with blurry landscapes, portraits, and still lifes, tied together by their techniques (thick layers of wet paint applied to wet paint) and their strange, almost surreal colors. To twenty-first-century eyes, these images look ordinary, but critics were unimpressed. Human skin, lamented the members of the artistic establishment, had turned green and purple and orange. Naturalism had been abandoned in favor of these periwinkle monstrosities.

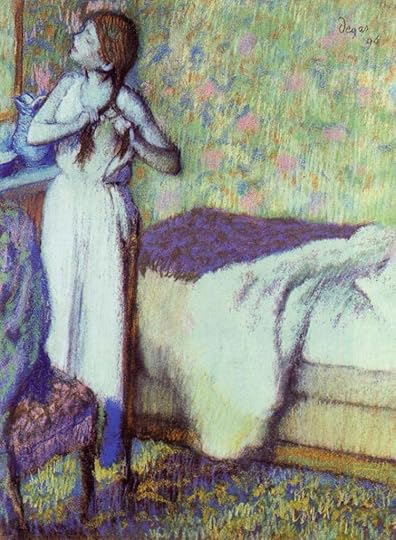

Edgar Degas, Young Girl Braiding Her Hair, 1894

Periwinkle’s first known appearance in English as a color-word was in the 1920s, but it has been in the painter’s toolbox for far longer, nestled under the violet umbrella. Periwinkle is a Modernist word for a Modernist color. It’s a word that has several meanings—in addition to being a flowering plant, a periwinkle is also a type of snail, though not, confusingly, one that secretes purple liquid. It’s a nature word for a color most often found in nature. A dreamy word for a color that exists at the edges of the night.

Edgar Degas, Portrait of Giulia Bellelli (Sketch), 1860