Lucy V. Hay's Blog, page 5

January 6, 2021

How to Edit Your Novel’s Structure

Editing Your Novel’s Structure By Bethany A. Tucker

Today I have a review for the above book. I’m both an author and a script editor myself, so I am always interested in reading non fiction about the process. No writer is too experienced to learn something new, plus it can be incredibly useful to offer alternative viewpoints to my own clients. Make sure you check out the info and links at the bottom of this post if it sounds of interest to you.

My Review

First up, this is a short book, just 135 pages, so it’s a short read that offers good value. Instruction is clear and precise, plus it is delivered in a conversational style. I particularly liked the fact she places emphasis on what works for the individual, plus I thought the checklists were great for those writers who are struggling.

First up, this is a short book, just 135 pages, so it’s a short read that offers good value. Instruction is clear and precise, plus it is delivered in a conversational style. I particularly liked the fact she places emphasis on what works for the individual, plus I thought the checklists were great for those writers who are struggling.

There’s some excellent commentary on characterisation here, plus I like how Bethany makes reference to diversity, intentional inclusion and cultural appropriation. These are particular focuses of my own writer’s site Bang2write as I really believe writers should consider the potential impact of their words and imagery.

I also love how Bethany talks about movies as well as books. As a script editor for movies as well as a novelist, I see convergence between them too. Whilst obviously there are different ways of presenting screenplays and novels, I’m a great believer there’s ‘no’ difference between the mediums in real terms because it’s all storytelling. This means all writers face the same challenges in getting their stories on the page.

I note Bethany is a fantasy author, which may account for why she seems to talk about stories like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings so much. (I don’t think she goes overboard on this to be fair, I just don’t like that genre much so it seemed to ‘stick out’ to me).

Bethany also seems to conflate structure with what I call ‘thematics’, paying particular attention to storyworld. I prefer to keep structure to plotting elements with thematics as a separate piece of the jigsaw, but this is a personal preference (probably because I am a screenwriter at heart). It was fascinating to read Bethany’s approach because it was different to mine and it never hurts to consider alternatives.

To sum up, I feel this book would especially useful for newbies, or writers stuck in what I call ‘The Story Swamp’ where everything feels like it is going wrong in a draft. Those authors suffering from writer’s block would also benefit in my opinion. Recommended!

Editing Your Novel’s Structure: Tips, Tricks, and Checklists to Get You From Start to Finish

Before it’s time to check for commas and iron out passive voice, fiction writers need to know that their story is strong. Are your beta readers not finishing? Do they have multiple, conflicting complaints? When you ask them questions about how they experience your story, do they give lukewarm responses? Or have you not even asked anyone to read your story, wondering if it’s ready?

If any of the above is true, you may need to refine the structure of your story. What is structure you ask? Structure is what holds a story together. Does the character arc entrance the reader? Is the world building comprehensive and believable? These questions and more have to be answered by all of us as we turn our drafts into books.

In this concise handbook, complete with checklists for each section, let a veteran writer walk you through the process of self-assessing your novel, from characters to pacing with lots of compassion and a dash of humor. In easy to follow directions and using adaptable strategies, she shows you how to check yourself for plot holes, settle timeline confusion, and snap character arcs into place.

Use this handbook for quick help and quick self-editing checklists on:

– Characters and Character Arcs.

– Plot.

– Backstory

.

– Point of View.

– A detailed explanation of nearly free self-editing tools and how to apply them to your book to find your own structural problems.

– Beginnings and Ends.

– Editing for sensitive and specialized subject matter.

– Helpful tips on choosing beta readers, when to seek an editor, and a sample questionnaire to give to your first readers.

Grab your copy of Edit Your Novel’s Structure today! Now is the time to finish that draft and get your story out into the world.

BUY THE BOOK

AUTHOR BIO: Bethany Tucker is an author and editor located near Seattle, U.S.A. Story has always been a part of her life. With over twenty years of writing and teaching experience, she’s more than ready to take your hand and pull back the curtain on writing craft and mindset. Last year she edited over a million words for aspiring authors. Her YA fantasy series Adelaide is published wide under the pen name Mustang Rabbit and her dark epic fantasy is releasing in 2021 under Ciara Darren. You can find more about her services for authors at TheArtandScienceofWords.com.

AUTHOR BIO: Bethany Tucker is an author and editor located near Seattle, U.S.A. Story has always been a part of her life. With over twenty years of writing and teaching experience, she’s more than ready to take your hand and pull back the curtain on writing craft and mindset. Last year she edited over a million words for aspiring authors. Her YA fantasy series Adelaide is published wide under the pen name Mustang Rabbit and her dark epic fantasy is releasing in 2021 under Ciara Darren. You can find more about her services for authors at TheArtandScienceofWords.com.

November 16, 2020

Did 2020 Change YOUR Reading Habits?

How did you spend your free time in 2020?

2020 has meant a lot of free time for many people … or no free time at all! My year has fallen into the latter category, but what of the rest of you?

Because of coronavirus, many people spent a lot more time at home. Some turned to watching YouTube and Netflix, others played video games, baked bread, or made crafts.

Bibliophiles only had one thing on their mind, however — churning through more of their favourite books.

How exactly did coronavirus change our reading habits? Which countries read the most? And what books and genres did we dive into?

Editing and proofreading service Global English Editing gathered statistics from various sources to answer these questions. They summarized all the findings in a great new infographic on world reading habits in 2020.

Some of the most interesting finding include:

35% of people read more because of coronavirus

Print books are still more popular than eBooks, although the gap narrowed significantly this year

Maybe because single people couldn’t find love in a time of social isolation, romance books flew off the shelf like never before.

For more eye-opening insights into world reading habits this year, check out the infographic below.

October 31, 2020

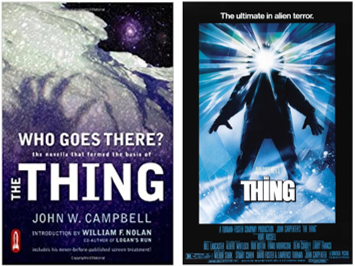

BOOK VERSUS FILM: The Thing

The Thing Is …

Antarctica. Home to penguins, the South Pole, and one of the scariest sci-fi/horror stories ever. But what’s more effective: the page-turner or the popcorn-pleaser? And are those chills just –49˚C winds, or something nastier? Is there some Thing at the door? Zip up your parka, strap on your snow-shoes, and let’s ask Who Goes There? But if you see any stray huskies, don’t pet them…

The Story

A scientific expedition camp finds an alien, preserved in the ice. When it thaws out, they discover that not only it is alive but can also shape-shift into any of them. Suspicion leads to paranoia and even murder, as everyone realises no-one may be whom he seems…

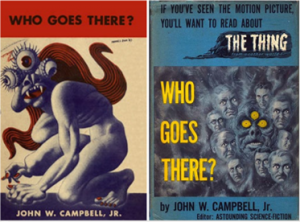

The Novella: Who Goes There?

When it was published in Astounding Science Fiction in 1938, little did anyone guess Who Goes There? would undergo almost as many changes as the alien in it. The title has occasionally been The Thing from Another World (the name of the 1951 film version), the length has been 12 chapters or 14 chapters (and now there’s the recently discovered novel-length edition) and the author has been credited as Don A Stuart, a pseudonym of John W Campbell Jr (the name comes from his first wife, Doña Louise Stewart Stebbins). Like the paranoid denizens of Big Magnet Antarctic base, you’ll be forgiven for wondering which version you’re getting.

The camp’s population is 37, all men, plus dogs and cows. The principal characters are Commander Garry, the base’s leader; McReady, a meteorologist and second in command; Connant, the first person suspected of being an imitation; and Blair, who realises the threat it poses to humanity. These characters are easily relatable. From Garry we feel the self-doubt, when his identity is questioned; from McReady we witness someone having to think fast and assume command; from Connant we experience the fear of suspicion as the others ostracise him; and from Blair we understand the full horror and consequence if the creature should reach civilisation.

The camp’s population is 37, all men, plus dogs and cows. The principal characters are Commander Garry, the base’s leader; McReady, a meteorologist and second in command; Connant, the first person suspected of being an imitation; and Blair, who realises the threat it poses to humanity. These characters are easily relatable. From Garry we feel the self-doubt, when his identity is questioned; from McReady we witness someone having to think fast and assume command; from Connant we experience the fear of suspicion as the others ostracise him; and from Blair we understand the full horror and consequence if the creature should reach civilisation.

Some Thing Wicked …

At the centre of it is the Thing. Unnamed, unidentified. It never speaks in its own voice, though we learn it has telepathic powers, and in a disturbing example of cunning, it accesses the memories of other people to ensure the person it has copied behaves as they expect.

And that’s the novella’s biggest difference to the film versions. This creature is more devious than the parasitic killer onscreen. In the novella’s most memorable scene, a blood-serum test to positively identify humans fails, and suspicion falls upon two people. The Thing rationalises how the other person must be innocent – and by doing so looks innocent itself. It’s hard to escape the notion that the alien is the smartest one in the room.

By writing in the third-person, Campbell Jr never gives us insight into anyone’s thoughts – so we have no idea who is human and who isn’t. This allows the novella’s main theme, paranoia, free reign. The misidentification aspect goes back to the author’s childhood too: his mother and aunt were identical twins, so he grew up knowing how it felt to question if someone was the person they appeared to be.

Whilst there’s a lot of science, it’s handled in a way that doesn’t confuse the reader. However, that method of presentation – dialogue – has its own challenges. Sometimes a character talks for an entire page or more, which comes across as unrealistic, and many scenes – including discovering the spacecraft and sabotaging their aircraft – are related in yet more dialogue. That maxim about ‘show don’t tell’ is largely ignored, so we’re frequently left with the impression of being told a story rather than experiencing it.

The Science Fiction Writers of America described Who Goes There? as one of the “most influential, important, and memorable” stories, and its core idea is now a sci-fi staple; from Doctor Who to The X-Files, we just keep finding bad things in the ice. But if we thought we knew everything about Campbell Jr’s alien, we were mistaken…

In 2018, a novel-length manuscript called Frozen Hell was found among papers sent to Harvard University. A Kickstarter campaign saw the original story finally see print, 81 years after Who Goes There? first sent chills up readers’ spines. Which shows, no matter how long something lies dormant, there’s still life in it yet…

The Film: John Carpenter’s The Thing

Back in the 1970s, producers David Foster and Lawrence Turman felt it was time for a more faithful adaptation of Who Goes There? than 1951’s The Thing From Another World. Co-producer Stuart Cohen suggested John Carpenter for director, but Universal wanted an established name. Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and John Landis (An American Werewolf in London) were considered, but the project stalled until Alien’s box-office triumph. Meanwhile, the most profitable independently produced film up to that point opened in 1978. That film was Halloween. John Carpenter was back on the list.

Back in the 1970s, producers David Foster and Lawrence Turman felt it was time for a more faithful adaptation of Who Goes There? than 1951’s The Thing From Another World. Co-producer Stuart Cohen suggested John Carpenter for director, but Universal wanted an established name. Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and John Landis (An American Werewolf in London) were considered, but the project stalled until Alien’s box-office triumph. Meanwhile, the most profitable independently produced film up to that point opened in 1978. That film was Halloween. John Carpenter was back on the list.

Carpenter was reluctant, being a fan of the 1951 film (it’s on the television in Halloween); however, he loved the novella, having read it in school, so the idea of filming that was tempting. He decided not to adapt it himself, but found the scripts offered somewhat lacking, ignoring the shape-shifting aspect – also absent from the earlier film – and resorting to the dreaded ‘man in a suit’ monster. The one writer who understood his vision was Bill Lancaster.

Lancaster slashed the base personnel to 12, upped the action, dispensed with the story about finding the alien by including a Norwegian camp that found it first, and introduced many concepts that became indelible with the film, including the famous blood-test scene – the scene that convinced Carpenter to sign on. With a budget of $15 million, filming began on location in Alaska and British Colombia (where the exterior camp was built six months earlier, before the snow fell), as well as refrigerated Hollywood studio sets.

Cast & Characters

Many of the novella’s principal characters appear, with minor changes. Microbiologist McReady is now helicopter pilot MacReady, his non-science background making him a better conduit for the audience’s questions. Commander Garry’s part is diminished, as are his leadership qualities. Connant is dropped; his role of first suspect is unnecessary, because once the alien’s chameleon-like nature is known, everyone is suspected. Blair is perhaps the character who changes least between page and screen, still being the first to realise the threat it poses to the world, going mad, being isolated, becoming the Thing and almost building a means of escape.

Carpenter turned to his Elvis and Escape From New York star Kurt Russell for MacReady. British actor Donald Moffat played Garry, and Wilford Brimley was cast as Blair when first choice Donald Pleasence was vetoed as being too recognisable. One significant addition was the mechanic Childs, a first major film role for stage actor Keith David, who filmed most of his scenes with a broken hand. With the decision taken to return to the all-male crew of the novella, the only female cast member was Carpenter’s then-wife (and The Fog star) Adrienne Barbeau, voicing MacReady’s chess computer.

Thing’s Change …

It’s surprising how much of the novella is retained, albeit with a few twists. The creature is once again a shape-shifter, though the telepathy has been dropped; the blood-serum test is sabotaged this time (someone destroys the uncontaminated blood samples); MacReady works out that sticking a heated wire into extracted blood will identify an imposter; and the Blair-Thing still goes all Scrapheap Challenge whilst locked in the shed.

Where the film comes into its own is with what’s added. This camp doesn’t ‘find’ the Thing, it literally runs up to them, disguised as a huskie. When MacReady visits the Norwegian camp, the corpses found there prime us for what follows. And what follows are some of the goriest special effects ever – courtesy of 22-year old (really!) Rob Bottin and his team, with help from Stan Winston (he did the dog-Thing that gets torched). Universal initially budgeted the effects at $200,000. They came to $1.5m – and every cent is there, on screen.

But whilst the effects are rightly celebrated, they’re only one part of the film. Right on the halfway point MacReady says, “Trust’s a tough thing to come by these days,” and paranoia is still the story’s DNA. Carpenter makes us doubt everyone – including MacReady –tightening the screws until the film’s finest scene: the blood-test. The tension is sharper than an alien’s incisors and, until we get to the actual reveal, the whole thing is played out without a single special effect. It’s all in the acting, the writing, the directing.

If there’s one thing that’s discussed more than the effects, it’s the ending. Bleaker than an icy tundra, with the camp destroyed and everyone else dead, MacReady and Childs wait to see if one of them is the Thing as a frozen death awaits. Carpenter wanted this to be a heroic sacrifice: the men forfeiting their lives rather than risk the alien reaching civilisation. The question of whether one of them is ‘it’ has become the focus of much debate. Carpenter has teased that someone is the Thing, but he ain’t saying who. Such ambiguity for a film about suspicion feels rather fitting.

From a story perspective, there are a few unanswered questions (who sabotaged the uncontaminated blood?), and strange inconsistencies (the sign reads ‘United States National Science Institute Station 4’ but everyone calls the base “Outpost 31” – a holdover from an earlier draft). Also, some characters wander off like teenagers at Camp Crystal Lake. We never really get to know them like the crew of Alien, but The Thingdeserves kudos for avoiding the one pitfall of Ridley Scott’s classic: this monster is a whole menagerie of horrors (Bottin theorised it could morph into any creature it has previously assimilated – so there’s a lot of spiders in space) but it is never, ever a man in a suit.

From a story perspective, there are a few unanswered questions (who sabotaged the uncontaminated blood?), and strange inconsistencies (the sign reads ‘United States National Science Institute Station 4’ but everyone calls the base “Outpost 31” – a holdover from an earlier draft). Also, some characters wander off like teenagers at Camp Crystal Lake. We never really get to know them like the crew of Alien, but The Thingdeserves kudos for avoiding the one pitfall of Ridley Scott’s classic: this monster is a whole menagerie of horrors (Bottin theorised it could morph into any creature it has previously assimilated – so there’s a lot of spiders in space) but it is never, ever a man in a suit.

Release & Reception

When the story of an alien stranded on earth opened in the summer of ‘82, audiences went wild. However, that alien was Steven Spielberg’s extra-terrestrial, which came out two weeks earlier, and may have contributed to The Thing’s poor box office. There’s been almost as much debate as to why it failed as there has about that ending, and possibly the nihilistic finale (at a time when America was in recession, so more uplifting films fared better) played its part too. But what about the reviews?

Some critics took offence to those bloodthirsty effects, and others, it seemed, took inspiration. One said it was “entertaining only if the viewer needed to see spider-legged heads and dog autopsies” (five stars, right there), another called Carpenter a “pornographer of violence” (he laughs about it. Now.) It soon found a home, a fan base, and critical reappraisal thanks to the home-video revolution, and is today considered a classic – coming 4th on Empire’s top 50 horror films, one place ahead of Halloween – but its initial failure had consequences. Carpenter’s multi-picture deal with Universal was terminated, he lost the directing job on Firestarter, and his confidence plummeted. He has said that, if not for The Thing, his career would have taken a different path. But he has also said The Thing might just be his favourite, so it’s fitting it has finally been welcomed in from the cold.

2011 Prequel

In 2011, a prequel focusing on events at that Norwegian camp during the alien’s discovery was released. Directed by Matthijs van Heijningen Jr and starring Mary Elizabeth Winstead (a superb Ripley-on-ice) and Joel Edgerton, it shows its fan-love for Carpenter’s original in every frame.

Eric Heisserer’s script meticulously sets out how each discovery made by MacReady comes to pass, but cannily keeps us guessing who will suffer which fate. There’s a neat twist on the blood-test scene, as we learn the Thing cannot replicate metal, so open wide and let’s check for fillings (this throws an interesting slant on Carpenter’s ending, because one of those two gentlemen has an earring…) and it does raise the subject of alien infection, something Campbell Jr discussed but Carpenter dropped.

It also received a frosty reception, but fully deserves its own reappraisal. With our current obsession for origin stories, studios could do far worse than studying this. The only misstep was also calling itself The Thing – leading many to think it was a remake of the 1982 film – but otherwise it barely puts a foot, tentacle or claw wrong.

And the Winner is…

Both novella and film are rightly considered classics, and have been hugely influential. They share a sense of isolation, a feeling of paranoia, the fear of not trusting anyone, including yourself – and credit for that must go to Campbell Jr. But though Carpenter’s adaptation retains those elements, it adds eye-popping effects that no prose could replicate – and whilst the novella gets bogged down by dialogue, the film has a lean, streamlined narrative that’s relentless. It’s as impressive now as it was 38 years ago, and so John Carpenter’s The Thing is the winner.

BIO: Nick Jackson has written several Book V Film comparisons for Lucy, as well as short stories which have been published in numerous anthologies, usually horror and science fiction. He’s fairly sure he is human, but it’s a while since he had a blood test.

October 26, 2020

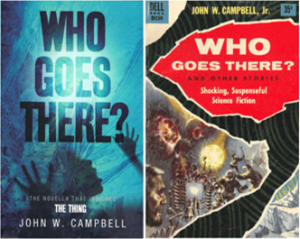

BOOK VERSUS FILM: Twilight – Which Version Is Best?

Twilight In The Garden of Good And Evil?

Is there any franchise as harshly and consistently maligned as Twilight? Fifteen years on from the first book, protagonist Bella is still lambasted as ‘lame’ and a ‘poor role model‘, whereas the Cullens are ‘stupid sparkly vampires’. In addition, various other interpretations insist Twilight is an advertisement for the Mormon faith.

But however you fall on these issues, there’s no doubt about it: Twilight is here to stay. Love it or loathe it, the notion of a human falling in love with a vampire is an iconic story. At its foundation, it’s a modern tale of star-crossed lovers akin to Romeo and Juliet, a pre-sold concept every high school student is familiar with … No wonder it was so popular amongst teenage girls!

With Halloween around the corner, I thought I would revisit Twilight as my first ‘Book Versus Film’ article in many months. As it’s 2020, I thought I’d check out not only the first book in the series and its movie adaptation, but also Midnight Sun, the re-telling of the original from Edward’s POV. Ready? Then let’s go …

The Book – Twilight

Selling over a hundred and sixty million copies, the Twilight saga is a cultural phenomenon. The story kicks off when misfit high school student Bella Swan moves from sunny Arizona to a rainy Washington state, where she meets Edward Cullen, an enigmatic and handsome teen. She is soon captivated by him. Though Edward struggles to stay away from her, Bella discovers her feelings are reciprocated.original

Selling over a hundred and sixty million copies, the Twilight saga is a cultural phenomenon. The story kicks off when misfit high school student Bella Swan moves from sunny Arizona to a rainy Washington state, where she meets Edward Cullen, an enigmatic and handsome teen. She is soon captivated by him. Though Edward struggles to stay away from her, Bella discovers her feelings are reciprocated.original

It is soon revealed Edward is a vampire whose family does not drink human blood. Bella is not frightened by this, but fascinated. Head over heels for him, she enters into a dangerous romance with her immortal soulmate who it appears will do anything for her, even kill.

I first read Twilight back in 2005 when it came out. Meyer also makes some additions to the vampire myth that whilst not always successful – like the aforementioned ‘sparkling’ – feel original. I LOVED the idea vampires have ‘venom’ like snakes. I also loved the contrary ideas that they’re super-strong and yet their limbs break off like tree branches, but can be stuck back on just as easily! There’s also some suggestion that, not needing to breathe, vampires can swim forever or even walk along the bottom of the ocean to other countries when travelling.

Like many feminists, I was a bit creeped out by some aspects of the story, especially Edward’s habit of coming into Bella’s room uninvited to watch her sleep. He also seemed capricious a lot of the time, his moods turning on a dime. This rarely seems to bother Bella though (an important distinction). She also manages to hold her own with him and doesn’t take any crap from him, or his family. I was especially amused by her irritation with Emmett’s grudging acceptance of her plan to escape James!

Like many other readers I found Bella and Edward’s relationship very compelling and dare I say it – considering Edward is a vampire! – realistic. The mutual obsession teen couples go through is deftly illustrated in the first book; they fall for each other hard and cannot imagine ever being with someone else. There’s also an angsty element to the book that again is supremely authentic: teenagers feel everything so deeply and that’s woven expertly here.

Edward and Bella’s love is in jeopardy from the offset, of course. Since the Cullens are living in plain sight (Carlisle is even a doctor at the local hospital), Bella is a threat in that she can expose the family at any time. However we don’t find that much out about Edward’s adoptive vampire ‘parents’ Carlisle and Esmee in the first book, plus moments in which his ‘sisters’ Alice and Rosalie and his ‘brothers’ Jasper and Emmett appear are all too fleeting. That said, every time they appear they feel like a ‘real’ family, with the psychic Alice and her beloved Jasper the real stand-outs for me. I also loved the notion that vampires can only play baseball during thunderstorms because otherwise they’re so strong, humans can hear the CRACK of the bats against the ball for miles.

So the Cullens are established as mostly friendly and helpful and not much of a threat to Bella. That said, Meyer repeats far too much that Edward ‘could’ kill Bella if ‘he loses control’ in my option. Even so, Edward feels like a complex character with plenty under the surface. His backstory is compelling, with us finding out he’s actually over one hundred years old, having been near death in the 1918 influenza pandemic. Carlisle was a doctor on that ward and seeing the young teenager with no one left, ‘resurrected’ Edward as a vampire. Whilst some feminists say this makes Edward a kind of paedophile being so much older than Bella, Meyer goes to pains to remind us Edward is a virgin and was never interested in sex or even romance until he met Bella.

In contrast, it’s hard to understand from Twilight what Edward really sees in Bella. She spends what feels like an inordinate amount of time cooking and cleaning, whereas Edward doesn’t eat regular food and appears to have zero interest in household matters so presumably doesn’t look for that skill in a life partner! Bella seems quite mature for her age – admittedly a plus when you’re a 107 year old virgin looking for love – plus she’s quite open-minded (also handy if your boyfriend is a vampire!). Beyond that, it’s hard to see what’s so special about her in the first book.

So whilst most of the characters, thematics and worldbuilding of the piece are layered and nuanced, plot-wise it feels much more of a slap-dash affair. Though I enjoyed the ‘will they/won’t they’ aspect, it got old fast. What’s more, the ending with the vampire threat of James, Laurent and Victoria seems to come out of the left field and far too late, almost right at the end of the book.Hearing the Cullens playing baseball, antagonist vampires James, Laurent and Victoria run to the clearing and ask to play as well … Only to discover the Cullens have a ‘pet human’ (Bella), whom they want to eat.

Edward and the others are forced to act and face down the new vampire trio and protect Bella, before going on the run. Edward, Carlisle and Rosalie take James on a wild goose chase through the forest, whilst Alice and Jasper take Bella to Arizona. James does not fall for this trick and tracks Bella to Arizona, where he attacks her. When Bella is bitten by James, Edward must save his love by sucking out the venom without killing her. Of course he manages to stop before draining Bella dry, proving he is not the ‘monster’ he thinks he is and showing Bella is right to trust him.

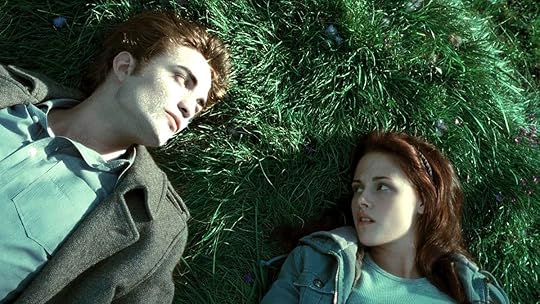

Twilight – The Film

As an adaptation, Twilight is epically faithful to the source material. Unusually, a female duo take control of the movie, but this makes sense when the army of Twilight fans are predominantly female too. Directed by Catherine Hardwicke and written by Melissa Rosenberg (who’d previously been co-executive producer on teen favourite The O.C), the story is in expert hands.

So it should surprise no one that Twilight took a big fat vampire-sized bite of box office revenue when it came out in 2008. The first movie grossed $37m on its opening day and accounted for $400m of the total $3.3bn for the whole franchise. It’s the smallest takings of the bunch but very respectable for a 2008 world that hadn’t seen multiple billion dollar earners courtesy of the likes of Marvel yet.

What was surprising that for a teen movie, a good chunk of its reviews were respectable too. Though many critics could not resist bashing the movie, even those who didn’t like it were forced to give grudging kudos …

“The two hormonal teenagers sizzle like sausages in a frying pan. The supernatural stunts don’t disappoint. Neither does the deadpan wit.” (The Times)

“Some will find it all too polite, but compared to rival blockbuster exercises in explosive CGI mayhem, its character-based index of longing and protectiveness at least provides a viable alternative moodscape.” (Time Out)

“Ten years after its release, Twilight stands as a powerful, darkly stylish depiction of teen female desire.” (Refinery29)

The aesthetic is gorgeous, with Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson born to play these roles. Everyone looks effortless sexy with amazing styling; the movie it feels like an early 90s music video for most of it.

Whilst it’s Bella and Edward’s story, the female characters dominate the frame over their male counterparts, even lesser characters like Jessica (Anna Kendrick). There’s also a considerable amount of diversity in contrast to the book, with many secondary and peripheral characters cast as black and asian actors. The rainy, dark town of Forks brought to life as surely as if it had stepped straight out of the novel.

Also in contrast to the book which was *all* from Bella’s perspective, we see more of Edward’s POV generally. Occasionally he branches off without Bella, usually to give us more of a sense of his family, especially Carlisle, Alice and his brothers. This is a welcome change, since I felt it was frustrating to see so little of them in the first book. It also introduces more chance for action: we are left in no doubt that Edward has super-human strength when he stops the truck from crushing Bella. We also see the others doing incredible things too, such as James running at super-human speed after Edward and Bella in their own vehicle, or Emmett jumping through the trees and landing in the truck’s flatbed behind them as they escape.

The big change in the movie is to the antagonist function of James, Laurent and Victoria. Rather than have them simply ‘turn up’ out of nowhere for the baseball game towards the end, the movie seeds the trio’s dark presence from around the end of Act 1, getting nearer and nearer to Forks. On their way, they attack and kill a number of Forks residents. Since Bella’s father Charlie is police chief for the town, this ties his character ‘in’ to the story in a much more authentic way too, as in the book he kind of ‘floats around’ the periphery of the story. It also adds to the Quileute Nation’s worry about ‘The Cold Ones’, especially from the POV of Jacob. He is somewhat under-used in the first book and more of an ‘Expositional Jo’ character, there simply to tell Bella the history of the Cullens and the tribe.

Twilight – ‘Midnight Sun’

A long-anticipated re-telling of Twilight, Stephanie Meyer’s Midnight Sun has been in development so long that apparently Robert Pattinson used her unpublished manuscript to inform his character work in the movies twelve years ago. Published at long last in August 2020, it sold one million copies in just ten weeks. Though critics were largely unimpressed, the ‘Twihards’ lapped it up.

What drew me to Midnight Sun first and foremost was Edward had always been my favourite character in the Twilight saga. I always wondered what he saw in Bella and felt this retelling might answer that.

I was rewarded with exactly this, but even more: Meyer seeks to put the record straight about Bella and the notion she and Edward are in an ‘abusive’ relationship. Meyer seems to assert that no, Edward is NOT a ‘stalker’, but instead a vampire guardian angel for Bella. She appears to say that Bella is NOT lame, but misunderstood, a girl kind of ‘outside of her time’. Meyer even seems to paint Bella as having some kind of death wish because she thinks of others before herself. Whilst I was not entirely convinced by much of this, I found Bella via Edward’s eyes hugely more compelling, so mission accomplished Stephenie Meyer!

What’s more, Meyer attempts to clear up the whole ‘sparkly vampire’ thing like she does in the 2010 Bree Tanner novella. It’s more convincing here in Midnight Sun, where we see Edward worry about Bella seeing the ‘real him’ and remembering his shock when he saw Carlisle in the sun for the first time. There’s also some suggestion the sparkles look like flames to humans which would have been much cooler than what depicted in the movie, though ultimately I couldn’t get that sparkling image of Robert Pattinson out my head.

We also see lots more of not only the Cullens in Midnight Sun, but also more details of how their gifts work. Edward’s ‘mind reading’ is great and answers lots of questions I had about how he doesn’t seem able to read Bella’s (he can’t!). There’s also some suggestion Bella gets this from Charlie, whose thoughts Edward can’t read either. Alice’s ability to see the future is painted much more vividly too, whilst Jasper’s ability to influence the moods of others around him is brought to the fore here with great effect, especially at the baseball game with James and the others.

We also see a lot more of Edward’s past and his relationship with Carlisle in particular. The father/son dynamic here is fantastic and was entirely missing in the first book. Whilst we know from the movies Edward went ‘rogue’ for a few years, we don’t know any real in-depth details. In Midnight Sun we hear of how Edward hunted down serial killers, rapists and paedophiles, but Meyer goes a step beyond such classic anti-hero tropes. There’s a great sequence where Edward describes ‘hearing’ a man trying to resist his own urge to abduct and abuse a child. Edward hopes the man can stop himself, but of course he can’t, forcing Edward to dispense his particular brand of justice.

We also see a lot more of Edward’s past and his relationship with Carlisle in particular. The father/son dynamic here is fantastic and was entirely missing in the first book. Whilst we know from the movies Edward went ‘rogue’ for a few years, we don’t know any real in-depth details. In Midnight Sun we hear of how Edward hunted down serial killers, rapists and paedophiles, but Meyer goes a step beyond such classic anti-hero tropes. There’s a great sequence where Edward describes ‘hearing’ a man trying to resist his own urge to abduct and abuse a child. Edward hopes the man can stop himself, but of course he can’t, forcing Edward to dispense his particular brand of justice.

At a whopping 756 pages Midnight Sun is far, far too long given we have the first four books, the Bree Tanner novella AND five movies to draw from already. I feel like Meyer could have cut 200-250 pages easily. There’s far too much repetition (‘I’m the villain of the story‘) and general rumination of how great Bella smells which makes her seem like a piece of meat or a freshly baked cake. No doubt humans are food to vampires, but it felt overcooked (arf).

As in the first book, the final showdown with James, Laurent and Victoria is very sudden but again my favourite part. There’s a stronger sense of jeopardy in Midnight Sun than Twilight in my opinion. We are also with Carlisle and Edward every step of the way when they draw James away from Bella through the forest, which is a very welcome addition too.

Verdict

This is such a tough one to call as all three versions of this story have their own charms as far as I am concerned! I really enjoyed the pre-sold, original take on the romance concept and angsty authenticity of the first Twilight book … But then I MUCH preferred the addition of the antagonists’ arc and murder spree on their way into Forks in the movie. Edward has always been my favourite character in this saga which draws me to Midnight Sun, but I also feel like it’s far too long as well.

So there’s a whisker between them … But ultimately, being a plotting junkie and because I love the aesthetic so much, I think the movie just grabs the victory!

What about you?

September 14, 2020

BOOK VERSUS FILM: The Warriors – Fight to The Death

In my youth I was completely oblivious to the fact that creative types would adapt movies from books, so when I discovered that The Warriors was originally a novel, I had to read it right away. The movie adaptation was instrumental to me creating my own novel, The Big Smoke. The exploration of an exaggerated New York and the issues of class and race were hugely relatable themes to my work and the world I grew up in.

So let’s delve into the world of The Warriors because it’s time to play-ay!!!!

About The Book

The Warriors was originally written by American author Sol Yurick and released in 1965. This was a time in America when war was happening externally in Vietnam and internally with the Civil Rights movement. Born and raised in New York and working in the welfare department, early in his life Sol was exposed first hand to hundreds of families and children on welfare (or ‘juvenile delinquents’, as they were referred to at the time). Sol quickly learnt how many different fighting gangs had been created and operated in New York, numbering in the hundreds. Some of them so big they could be classified as small armies and entirely made up of black and Hispanic members.

The story follows one of the many gangs that inhabit New York City, The Dominators. This was a group of African American and Hispanic men and boys who venture out of their territory, along with the other gangs in New York, towards a meeting being held in The Bronx by the leader of the largest gang in the city, Ismael. Despite Ismael’s intentions of uniting the gangs in the city in a bid to take up arms against “the man” things between the gangs quickly escalate. Fights break out and Ismael is caught in the cross fires and the arrival of the police forces the gangs, including The Dominators, to scatter.

The Dominators are forced to trek back home to their territory while trying to avoid the police and rival gangs. Throughout the long journey back home the members of the gang have their ranks, and most importantly their perceived manhood, put to the test.

Told through the different points of view of some of the members of the gang, Sol Yurick is able to explore issues around economic class and opportunity. This includes the racial inequality that was and unfortunately still is apparent in modern day America. Also included is the subject of toxic masculinity and what it means to be a “real man”.

Hinton, as the 2nd’ youngest member of the gang is the focal character of the story. He is tasked with getting his gang back home safely due to his vast knowledge of the city. Throughout the journey home the hierarchy and placement of the gang is frequently questioned which results in acts of “manhood” to settle disputes.

Being one of the newer members of the gang, Hinton often offers up ideas which would help the group on their journey. This includes suggesting the gang remove their insignia to avoid any unwanted attention; however he is often dismissed and told to stay in his place. He’s in a constant battle between right and wrong and trying to find his spot, not only within the gang, whom he considers his family, but also his spot in life. He’s exposed to extreme violence which he feels he must take part in, partly due to peer pressure from his fellow gang members and partly due to an insatiable animalistic desire that supposedly makes him a man.

About The Film

The film rights to Sol Yurick’s novel were purchased in 1969. However no film or development was made on the script until the spring of 1978, with the film being released just under a year later in February 1979, almost 15 years after the book was written.

The basic premise of the movie is the same as the book, The Warriors (known as The Dominators in the book) are invited to a mass gathering by Cyrus, the leader of the most powerful gang in New York who wants to unite all of the gangs in the city. Cyrus is then shot and killed and unlike in the book, the shooter is identified as Luther, leader of the Rogues. Luther subsequently blames the Warriors for murdering Cyrus.

The basic premise of the movie is the same as the book, The Warriors (known as The Dominators in the book) are invited to a mass gathering by Cyrus, the leader of the most powerful gang in New York who wants to unite all of the gangs in the city. Cyrus is then shot and killed and unlike in the book, the shooter is identified as Luther, leader of the Rogues. Luther subsequently blames the Warriors for murdering Cyrus.

The unarmed Warriors are forced to travel through New York City and back to their territory after a hit is put out on them. Every other gang in the city is on the hunt to find The Warriors as doing so would not only allow them to get revenge for Cyrus’s death but it would also elevate their status amongst the other gangs in New York.

Although the films focus is on The Warriors, the main protagonist is Swan, the ‘War Chief’ of the gang who takes charge of the group. It doesn’t take long before The Warriors are separated after being chased off by the police at a subway station in Manhattan. From there the gang are forced to try and reunite while avoiding rival gangs, police and their own egos.

Not all of The Warriors make it back to their turf. When the group finally think they’re home free they’re confronted by Luther, who has been tracking The Warriors since he shot Cyrus. This ultimately leads to the finale, the Warriors redemption and one of the most memorable and iconic lines in cinema history.

Book Versus Film

Whilst both of these stories follow a similar narrative structure in terms of the gang needing to get from point A to point B without facing the wrath of any rival gangs, the stories differ in terms of the deeper contextual meanings and representation of issues on race, class and masculinity.

The book has a heavy focus on predominantly black and Hispanic characters. This includes issues revolving around how they’re seen as lesser beings compared to “the man” which is not just a reflection of the police, but also the white man. The majority of the characters are looked down upon and seen as criminals due to the colour of their skin. This is why many of them have had to join gangs in the first place, something Sol Yurick had seen time and time again when working with children in the welfare system.

Although the film also touches on what it means to be a man, albeit in a much gentler way than in the book (no literal pissing contests to see who can urinate the furthest thus proving themselves to be the manliest!). The film does however explore the idea of class.

The most notable difference in the film (which also dilutes the idea of class and race being connected), is the main character and many of the focal characters being portrayed by white actors and not black and Hispanic. Sol Yurick himself wasn’t happy with the amount of white actors cast in the film adaptation. Sol, who was barely kept in the loop about the production of the film was told that they could not have an all-black cast due to “commercial reasons”.

One of the more noticeable differences between the two versions is the representations of how the gangs are portrayed. The book has an almost realistic reflection of real life gangs and gang warfare in 1960’s New York. The gangs are often of the same race; they also take pride and ownership of their turf and will have some sort of colour or symbol that represents their group.

In contrast, the film takes a much more eccentric and over the top view in expressing the different gangs. Almost all of the gangs are defined by their unique outfit choice which range from a simple waistcoat with no shirt underneath it, to a gang who wear black and white face paint and don a full baseball uniform. The gangs in the movie adaptation are presented in a far more visual and almost camp fashion than they are in the book, which takes a far more simplistic approach. It takes away the realism Sol was trying to portray of New York gangs but as a Hollywood portrayal it is far more visually appealing.

Verdict

Both versions of The Warriors had a great impact on my own work as a writer, so much so that the portrayal of the extravagant gangs in the movie played a huge part in creating the world of my debut novel The Big Smoke.

The subject matter of the book explores profound issues that remain prevalent topics today. The idea of non-white people being seen as ‘less than’ in current society is something that hasn’t changed in the modern world and is very apparent in current day America, such as the Black Lives Matter movement being still necessary.

However, in terms of a compelling story with an engaging narrative and fleshed out characters, the book falls flat. Besides the central character of Hinton I didn’t really care about any of the other players. His progression from young boy to “man” is explored well throughout the book as he explores his own status and views of what it is to be the man he needs to be in the world he lives in. Many of the other characters are fairly one dimensional and similar in presentation.

However, in terms of a compelling story with an engaging narrative and fleshed out characters, the book falls flat. Besides the central character of Hinton I didn’t really care about any of the other players. His progression from young boy to “man” is explored well throughout the book as he explores his own status and views of what it is to be the man he needs to be in the world he lives in. Many of the other characters are fairly one dimensional and similar in presentation.

The story itself, although exploring the depths of class and race, often relies on remarkably violent moments to drive the story, including savage murder and a couple of incidents of gang rape which add nothing to the story except to provide instances of shock value. (Perhaps one could argue Sol was trying to portray a realistic, if not extreme view, of gangs in New York during the mid to late 1960’s).

Where the film misses the mark on focal racial issues it creates a more elaborate and enticing storyworld. There’s a multitude of bizarre and well-rounded characters, all of whom serve a purpose and create a variety of emotional responses from the audience. The film also adds more substance to the story as a whole as it includes the extra layers of The Warriors being blamed for killing the leader of the most powerful gang in the city. This immediately turns the story into a saga about The Warriors proving their innocence while they avoid being hunted by rival gangs. As soon as the idea of a manhunt is put in to place the stakes are instantaneously raised and the tension of the movie is heightened.

Overall I much prefer the film adaptation because it tells the more compelling, structured and enjoyable story. I’ve always preferred substance over style and the film version of The Warriors is able to capture both. If a story can grab my attention and keep me wanting more I consider that story a success and The Warriors does just that in terms of creating a dynamic world filled with diverse characters with beautiful visuals throughout while producing a simple yet engaging storyline.

So The Film Wins It!

What do you think? Let us know in the comments …

BIO: Nathan Srith is a husband and a father of three. He was born and raised in London. Coming from a mixed race – Sri Lankan/British background, Nathan grew up in a very diverse world. He was exposed to a variety of cultures and a wide array of cinema and TV, quite often viewing content he shouldn’t have been. However, he attributes his early introduction to media to his vivid imagination and creative storytelling. Nathan’s writing brings together his love of storytelling and the atrocious behaviour and treatment he has seen impact hard working people every day. Nathan Srith’s debut novel The Big Smoke is available on Amazon here.

May 12, 2020

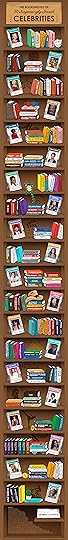

INFOGRAPHIC – 20 Celebrities Share Their Bookshelves

When it comes to book recommendations, your first point of call may not always be celebrities.

However, celebrities aren’t just promoting skincare products on social media or teaching their craft on MasterClass, they also frequently share their favorite recent reads.

Turns out their reading lists are actually as interesting and diverse as any other book lover!

Global English Editing have scoured the internet and found the favorite books of 20 surprisingly smart celebrities. From gripping fiction to moving memoirs to self help classics, these celebrities have some pretty impressive bookshelves.

While Chrissy Teigen is fascinated by murder mysteries, the South Korean singer Kim Ji-soo leans towards 20th century classics. She says her favorite book is The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Who says beautiful people can’t be nerds at heart?

If you’re looking for a new read, check out the following celebrity book recommendations. You may just find your next great book. Enjoy!

April 10, 2020

BOOK VERSUS FILM: Watership Down

It’s Easter, and that means bunnies – and that means Watership Down. For this Book Versus Film we’re taking a stroll through real Hampshire countryside searching for fictional rabbits, but who gets to rule the warren? Let’s hop to it…

The Book

For a modern classic, Watership Down started life without literary any intentions. It came into being as stories Richard Adams told his two young daughters during long car journeys. They insisted he write them down – and 18 months later, the manuscript was submitted to publishing houses. And rejected, seven times.

For a modern classic, Watership Down started life without literary any intentions. It came into being as stories Richard Adams told his two young daughters during long car journeys. They insisted he write them down – and 18 months later, the manuscript was submitted to publishing houses. And rejected, seven times.

Rex Collings, a small London publisher, finally took a chance. It was he who suggested the title, and though he couldn’t afford to pay Adams an advance, he did ensure a review copy went to every prominent critic. His gamble paid off, and word soon spread.

Told in four parts, each chapter begins with a quotation by sources ranging from Aeschylus to Napoleon. All the locations exist, and as the story opens it is May, and the mating season …

The Story

Fiver, a young rabbit, has visions that his home, the Sandleford Warren, will be destroyed in an imminent, inexplicable disaster. Most refuse to listen, except for Hazel, Fiver’s eldest brother. With a few others, they set off in search of a new home – to hills, many miles distant, called Watership Down.

After many perils the group reach the Down, but Hazel knows their long-term survival depends on persuading does to join them. They learn of an overcrowded warren called Efrafa, but it is ruled by the tyrannical General Woundwort, who will not permit anyone to leave. The rabbits instigate a daring plan to infiltrate and rescue several does from Efrafa – but though it succeeds, the General has tracked them to Watership Down, and plans a terrible revenge …

The Characters

Hazel is the main protagonist. He has no pretentions to become Chief Rabbit (or ‘Hazel-rah’) but as the most level-headed, the others turn to him to lead them, both figuratively and geographically. Fiver is hyper-sensitive, prone to seeing portents and used to being dismissed, until he is proven right when Sandleford Warren is destroyed to make way for a housing development – told in horrific detail by two survivors.

Of the other rabbits, the most significant are Bigwig, an officer in the Owsla (the rabbit military hierarchy), and their strongest buck; Blackberry, the clever one, who solves how to cross a river using driftwood as a raft; and Dandelion, their storyteller, an important position within rabbit society, who shares many tales about their mythical leader El-ahrairah.

Two more characters deserve a mention: Kehaar, a seagull the rabbits befriend when he has a damaged wing, and who not only finds Efrafa but also saves Hazel’s life by removing pellets after he’s been shot; and finally the antagonist, General Woundwort, who creates Efrafa and ruthlessly enforces it. He only appears in the final third of the book, but (as in the film) his shadow looms so large across the entire story that – as with Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs – you think he’s in it a lot more than he actually is.

Parallels have been drawn between the Sandleford rabbit characters and Homer’s Odyssey. It’s also been noted how Adams derives his ‘hero’s journey’ from the works of Joseph Campbell, in particular the mythologist’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces – which opens chapter 26, with a quote that perfectly captures Fiver’s (the Shaman’s) plight, after learning of Hazel’s injury.

Creating a World

One expects books like Dune or The Lord of the Rings to have within them a carefully crafted society, a language, mythology, proverbs, etc, but a kids’ book about rabbits? That’s what Adams has done, though. He’s created a language (Lapine), invents an entire creation-myth through the sun/god Frith, presents a mythic character in El-ahrairah the first rabbit – whose stories act as light relief throughout – and provides plenty of proverbs. It’s a terrific feat of world-building, and adds so much depth. And there’s even a map (two, in fact).

One expects books like Dune or The Lord of the Rings to have within them a carefully crafted society, a language, mythology, proverbs, etc, but a kids’ book about rabbits? That’s what Adams has done, though. He’s created a language (Lapine), invents an entire creation-myth through the sun/god Frith, presents a mythic character in El-ahrairah the first rabbit – whose stories act as light relief throughout – and provides plenty of proverbs. It’s a terrific feat of world-building, and adds so much depth. And there’s even a map (two, in fact).

Adams takes great care to ensure this new world is relatable. So many rabbit observations have an anthropomorphic lineage (rabbits count heartbeats between owl hoots to judge distance, in the same way we count between lightning and thunder), and there’s even a sly allusion to the Deluge myth, where a man “built a great, floating hutch that held all the animals and birds”.

But it’s still a story about rabbits, and Adams does not stint on the research. Much of it comes from R M Lockley’s The Private Life of the Rabbit, which is referenced several times. These bunnies fight, brutally; they defecate (or pass hraka, to use the Lapine term); and, most surprisingly, they have an urge to mate that could destroy their new peaceful life unless that need is met – not something you’d expect in a children’s book.

Reception

First published in November 1972, Watership Down received terrific reviews and won the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian’s Children’s Fiction Prize, among other awards. In a 2003 UK survey called The Big Read, it was voted the 42nd greatest book of all time.

For its American release, the book was cannily placed on the adult publishing list. As Connie Clausen at Macmillan astutely put it: “This isn’t about a bunny. It’s about life and death.” This crossover appeal made it a worldwide phenomenon, and by 1985 Penguin books declared it their second highest seller ever (behind Animal Farm), having sold over 5 million copies.

The book became so well known that by 1974, following President Nixon’s resignation, National Lampoon magazine wrote a satirical piece called Watergate Down. Two years later, Fantasy Games Unlimited released Bunnies & Burrows, responsible for many innovations in the then-fledgling role-playing game format, and inspired by Adams’s book. Whilst a belated sequel, Tales of Watership Down, was published in 1996, fans did not have as long to wait before it appeared on the big screen.

There have been several adaptations. In 1999 a British/Canadian TV series ran for three seasons, and in 2018 a BBC/Netflix four-part miniseries was screened. It’s been adapted for the stage at least twice, and radio numerous times – but the most famous interpretation, and the one I’ll focus on here, is the 1978 animated feature.

The Film

When producer Martin Rosen picked three-times Oscar winner John Hubley to direct the film, he probably thought the toughest job was behind him. A year later, however, he fired Hubley (his material can still be seen, in the stylised prologue where we meet El-Ahrairah), and working from his own script – with Hubley’s uncredited input – Rosen took over directing duties himself.

When producer Martin Rosen picked three-times Oscar winner John Hubley to direct the film, he probably thought the toughest job was behind him. A year later, however, he fired Hubley (his material can still be seen, in the stylised prologue where we meet El-Ahrairah), and working from his own script – with Hubley’s uncredited input – Rosen took over directing duties himself.

The Cast

Headlining an impressive cast-list, John Hurt gives an assured performance as Hazel, nicely offset by Richard Briers as a suitably neurotic Fiver. Interestingly, both would return two decades later to voice different characters in the TV series, with Hurt playing his own nemesis, but here General Woundwort is voiced with sombre gravitas by Harry Andrews. For a film so keen to replicate a bygone-era English countryside, however, trust an American to steal the show: Zero Mostel’s Teutonic-accented delivery as Kehaar, entirely in keeping with the book, is truly the gift that keeps on giving.

The Animation

To say this is over forty years old, the animation is still remarkable today. Of course, it cannot match the CGI wizardry of Disney/Pixar fare, but nor does it need to (and the recent miniseries showed just how charmless that would be). Watercolour backgrounds are often overlaid by soft-focus foregrounds to give a genuine sense of depth. Picking up on Adams’s love of nature, it also brings the countryside to life: the way water is represented by fractured, shifting sunlight is as breathtaking as the view from the top of Watership Down.

The characters are also well drawn, subtle use of anthropomorphised gestures making them more identifiable. Fiver especially is well served: a jittery presence throughout, his big expressive eyes always upon some horror neither we nor his friends can see. But if there’s one character that benefits most from cartoon corporeality, it’s Efrafa’s tyrannical leader.

If Darth Vader had a rabbit, it would’ve been General Woundwort. Were Angela Morley’s melodic score to detour into the Imperial March when this leporid leviathan lumbers into view, it would not have felt out of place. So indelible is this cinematic iteration, all future versions have retained Woundwort’s blind left eye – despite him not being so afflicted in the book. It’s also no coincidence he bares more teeth than any other rabbit. The General was designed to scare, and he does this well. Perhaps, as the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) discovered, a little too well. But let’s save that carrot for later…

Changes

To cram a 460-plus page book into a 91-minute film requires a lot of streamlining, so it’s surprising how little is lost. Most of it comes from the final third, where the journey to and from Efrafa, the river escape, and the final showdown are all shortened, though not at the expense of dramatic effect. Otherwise, the main differences come with reordering some events: the farm where Hazel is shot appears earlier, and Efrafa is now introduced when a wounded Captain Holly, having just come from there, finds Hazel and co. This is admittedly muddled: it’s presented as a flashback, but Holly doesn’t appear to be in the scene he’s remembering – and then there’s the question of how he left Sandleford after the rest, yet got all the way to Efrafa, escaped, then limped back to Watership Down just as the others first arrive there – but that’s the only misstep in a very faithful adaptation.

The most noticeable addition is a doe called Violet, who flees the Sandleford Warren with Hazel’s party. She’s not in the book, and sadly not in the film for long either. As the rabbits shelter in a field, she’s killed by a hawk. All we see is the bird swoop down, then a tuft of fur floating away, but the point is made: if the group’s only doe can be killed, nobody is safe.

Of course, whilst violence is permitted, sex is not: this is a British film, after all! These are a chaste bunch of bunnies, saying only that without does there will be no more rabbits. Also pruned are the tales of El-ahrairah. We just get the opening fable, where Frith turned the other animals against El-ahrairah as a punishment – but this does allow for a pleasing recap at the end, when we hear again Frith reminding us that, though the rabbit has a thousand enemies, it will never be destroyed. It’s something unique to the film, and brings it a satisfying close.

Reception

When it opened before Christmas 1978, Watership Down enjoyed good reviews and strong box office. It became a pop culture staple, helped in no small part by that song. Bright Eyes was the UK’s biggest selling single in 1979, and its video – a four-minute trailer for the film – was a marketing-campaigner’s dream. Okay, the lyric about the river of death should have been a clue, but nobody expected a song by one half of folk-rock duo Simon & Garfunkel to accompany anything but the gentlest of movies. And Watership Down is anything but the gentlest of movies.

The film was given a U (suitable for all) certificate, and the BBFC have admitted they’ve received complaints about this almost every year since. Woundwort plays a part, but more disturbing is the blood on display. We see it when Bigwig’s trapped by a snare; we see it as rabbits are ‘marked’ as Efrafans; and most memorably, we see it in the finale, when Woundwort battles several rabbits before facing down a dog. I feel its presence is justified – it adds to the realism – but audiences at the time were more used to The Rescuers or the part-animated Pete’s Dragon, films parents were safe taking their kids to. That it is disturbing is beyond doubt, and a re-certification is long overdue, but the film is simply staying true to the source material. To water down Watership Down would do a disservice to both film and book.

And the Chief Rabbit is …

Was this a tough choice? Do rabbits pass hraka in the woods…? To quote a rabbit proverb: “Our children’s children will hear a good story”, and both tell a very good story.

Whilst the film drops a lot of the incidental material, it absolutely gets straight to the heart of the rabbits’ quest for survival. It also packs an emotional punch then uncommon in animated features at the time (Bambi’s mum aside), and still looks beautiful today.

However, it cannot take us into the life of a rabbit with the same detail as the book. The sheer all-encompassing worldview we are presented in Adams’s prose, always informative yet never obstructive, for me is the deciding factor. It’s a close call, but the book is the winner.

What do you think?

BIO: Nick Jackson is the author of several short stories across numerous genres, and multiple Book V Film comparisons for Lucy. He lives nowhere near Watership Down, which is a relief because General Woundwort’s body was never actually found …

March 12, 2020

BOOK VERSUS FILM: Little Women

Little Women … Again??

Do we REALLY need another adaptation of Little Women? I mean, come on, there are numerous plays, two silent movies, over a dozen TV adaptations, a musical and even a 48 episode animated series. But it seems that a good story will always be revisited, maybe that’s the reason it’s called a classic.

The Book

Little Women barely needs any introduction. We’re all familiar with the March sisters: Meg, Jo, Beth & Amy). The book has been around for a long time (1868). This also present a challenge in adapting the story to the screen. So much have changed since it was written and especially when it comes to women’s role and position in society.

The book was written in a period when a woman’s place was in the home (or kitchen, if you want). Louisa May Alcott was urged to write the book by her publisher as a way to distract her from writing her own novels and poetry. No one expected it to be as successful as it turned to be. The idea was that it would be a guidebook for young girls on how to be the “perfect woman” and will guide them in the transition from childhood to adulthood. The novel addresses three major themes: domesticity, work, and true love. All of these are interdependent and each necessary to the achievement of its heroine’s individual identity.

The book was written in a period when a woman’s place was in the home (or kitchen, if you want). Louisa May Alcott was urged to write the book by her publisher as a way to distract her from writing her own novels and poetry. No one expected it to be as successful as it turned to be. The idea was that it would be a guidebook for young girls on how to be the “perfect woman” and will guide them in the transition from childhood to adulthood. The novel addresses three major themes: domesticity, work, and true love. All of these are interdependent and each necessary to the achievement of its heroine’s individual identity.

The book is beloved because each generation of women can find themselves in one of the March sisters. Most women love Jo the best and I am no different. I could identify with her. Jo is a tomboy, just like me. I also had a quick temper and would lash at people I loved. My own mum always wanted me to be an “Amy”, whom I despised (probably because my mum wanted me to be more like her!). Jo was a role model for me because I admired her individuality, even if the price of that individuality might be loneliness.

At the same time, I knew the book is not relevant to my time. Therefore you would understand why I was skeptical and surprised to find another version in 2019. Is it still relevant in this day and age?

Comparing The Films

I’ve decided to compare two versions of the film: one made in 1994 and and the latest one of Greta Gerwig from 2019. Each filmmaker has chosen to emphasise a different angle of the book. They also illustrate several shifts on the topics of womanhood, social responsibilities and wealth through American history. It was a fantastic lesson in scriptwriting on how a book can be the canvas of your own painting.

1994 VERSION

Ironic to think that in 1994 the era of Girl Power Little Women was considered a risky film to make. Denise Di Novi (Producer) said that at that time it was nearly impossible to get a female-driven film made. They called them “a needle in the eye” movies, where a guy would say to his wife “I’d rather have a needle in the eye than go to that movie”. But Denise di Novi knew Winona Ryder was obsessed with the book, so persuaded her to get on board. Ryder was at the height of her fame then, so Columbia was willing to green light it.

This was the first adaptation of the book into a movie after the Women’s Movement and the mass entrance of women into the workforce. The director (Gillian Armstrong) and scriptwriter (Robin Swicord) had to find a way to tell the story without it being stale and out of date. The story still relies on Jo’s arc, however, they did not want to portrait a bright rebellious woman as a tomboy, so instead Jo is a “theatre kid” – she is clever, creative and intellectually restless.

In the 1994 version the story concentrates on Jo finding employment and following her dreams. We get to see her writing much more than in other earlier versions. (The 1933 & 1949 versions were more about Jo’s challenge of womanhood, marriage and society’s role for her versus her own heart’s desire of writing and being creative).

In the earlier versions of the story Jo refuses Laurie’s marriage proposal because she thinks they are not a good match and that she will not be able to love him in the way that he loves her. In contrast in the 1994 version Jo refuses because she wants to find her own way in the world and focus on her art and writing. She uses the famous phrase of ‘It’s not you, it’s me’ and ‘let’s be friends’, which was more suitable for the 1990s.

In the 1994 version Jo’s mind constantly spins and looks for personal growth and fulfilment. This is how the director saw modern female virtues and the properties of contemporary woman. She believes women can take charge of all aspects of moral and practical life without depending on male support or advice.

Prof. Bear this time is an older man, but contrary to earlier versions, this time we get more screen-time to see their relationship develop. This means we get to see the reason why Jo would choose him over Laurie. Prof. Bear supports her writing and challenges her to improve it. Laurie isn’t ambitious as Jo and sees her writing and theatre as a hobby and a pastime and cannot understand her passion for it. Prof. Bear in this version courts her romantically and supports her … Best of both worlds for a modern woman!

More than earlier versions the 1994 version highlighted issues that were written in between the lines of the book of the 19th century. Swicord said that she tried to write this version in the way Louisa May Alcott might have written it without the restrictions women had in the 19th century. She did this by researching Alcott’s private life and memoires. That might be the reason that many would say that it strayed away from the original version.

2019 VERSION

Greta Gerwig’s version changes the whole structure of the book and is very different from all the other versions. True to the 21st century new direction in scriptwriting, she has chosen non-linear storytelling. The timeline runs back and forth between childhood and adulthood.

To begin, Gerwig’s version starts with the 2nd half of Little Women: the March sisters have grown up and found their way and place in the world. Where other versions treat the sisters peripherally, largely leading them to their marriage and then dropping them as if their life is over, Gerwig version finds parallel moments in their lives which makes them feel like real people who grow into and exist in adulthood.

For example, adult Meg counts pennies to afford a dress before we see her as a young girl eager to join society. Amy receives much more attention than in other versions. Her relationship with Laurie is predicted earlier and shows up more often, making their marriage acceptable and believable.

Interesting to point is that just like in the 1933 version, Gerwig’s version sets marriage as a threatening presence, even though it is also a necessity. Marriage had its practical purpose as an economical agreement. In Gerwig’s version, Amy gives a monologue how, as a woman, she is unable to earn her own income therefore must rely on her husband to sustain her. She feels robbed of her ability to work, so why wouldn’t she marry for money?

This is where Gerwig introduces another major difference and new aspect to this adaptation of the book. By giving Amy’s logic context, Gerwig indicates that individual choices are a consequence of systemic cause and effect. Amy must act in the world she was given until a broader, structural change can take place and offer her freedom.

More than any other versions of this movie, all the four sisters get to have their power. Though Jo is still the protagonist, the other March sisters are all strong and powerful in their own way. I find it a refreshing way of representing the book

This version of Little Women reminds us feminine power is in all of us, just in different shades and ways. In today’s world there is place for all types of women’s power and we should not diminish it when it shows up in a different voice and way than we expect it to be, we just need to look closer.

Another refreshing change in the 2019 version is the way Marmee is being represented. Already in the 1994 version, Marmee is shown as a strong individual woman, some might even call her ‘woke’. Susan Sarandon, who plays Marmee, isn’t the gentle tender character from the book. Instead she is an attractive, feisty heroic mum who isn’t hesitant to deliver short messages about raising her daughters according to unconventional way of life and how society treats women. She is shown as powerful and wise by actions not just words – for example it’s her homeopathic treatments that bring Beth from deathbed, not the traditional doctors.

In Gerwig’s version Marmee brings up a topic that has been a taboo for so long, which is women’s anger. Except for the TV mini-series with Emily Watson the sentence, which appears in the book, all other versions never gave it a place. Marmee confides with Jo by saying ‘I’m angry nearly every day of my life”. We finally get to hear Marmee’s frustrations of the confinements and limitations that were put on women at that time. We get to see the real feelings of that woman who was left to raise four girls on her own without support from her husband or society. Gerwig expresses what isn’t working in how women are treated or measured. This allows us to see the complicated Marmee character. On the surface she seems to be this sweet, loving, encouraging, kind woman. But when she lets the mask slip, you realise that she is fiercely angry with the fact that the world doesn’t repay that kindness. That’s a fantastic change and addition to the book.

The 2019 version fills in the gaps between Louisa May Alcott and Jo and uses biographical elements of Alcott’s life into Jo’s character. Jo negotiates the exact same deal for her book as Alcott did for her Little Women with the same rights and percentage of profits.

This version isn’t just about women’s employment (like the 1994 version) but also taking women seriously and giving them the same rights as men. It’s about respecting women’s ambitions and compensating them accordingly. It’s infuriating to see that though many have recognised this theme, still Gerwig was not rewarded for her work accordingly! This version is another example that the fight is STILL on for proper representation of women and recognition of their talents.

VERDICT

This one is easy. The book is definitely not as powerful today as it was when I read it as a child (and teenager). I couldn’t relate to it even when looking at it through nostalgic eyes.

This one is easy. The book is definitely not as powerful today as it was when I read it as a child (and teenager). I couldn’t relate to it even when looking at it through nostalgic eyes.

It’s true the 1994 version made the biggest change to the representation of the March sisters. However, Gerwig’s version is the one I’ve learned the most from. It deals with changes in structure, adding new layers to the characterisation.

From all the different movie versions Gerwig’s version is the one that, for me, is the most educational and empowering. So … it’s the 2019 movie for me all the way!

What About You?

BIO: Vered Neta is a proof that you’re never too old to start something new. She says she already had three past lives in this lifetime. After 28 years of being a trainer and working with over 150,000 people all over the world, she started a new career as a screenwriter, author and script reader. She wrote 2 screenplays and a musical. These days she is working on a documentary and a novel based on one of her screenplays and have started a YouTube TV program called #GoodLifeRedefined. You can find more on website www.veredneta.com.

February 22, 2020

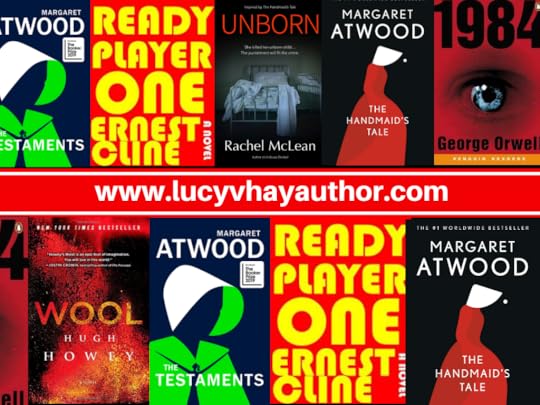

Top 5 Dystopias You Need To Read Right Now

As long-time readers of this blog know, I LOVE dystopian fiction! So I’m delighted to welcome author Rachel McClean to share her top 5 as part of her blog tour. Check out Rachel’s picks and her novel, Unborn, at the bottom of the post. Enjoy!

1) The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood