Nir Eyal's Blog, page 37

September 18, 2013

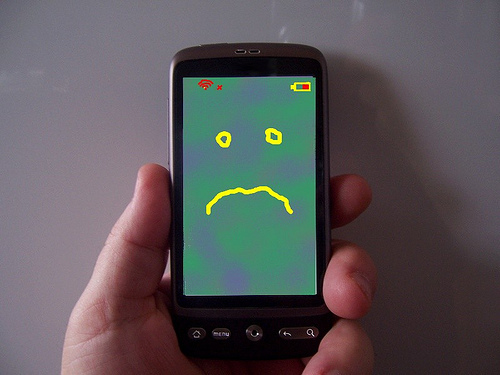

The Real Reason You’re Hooked to Your Phone

Nir’s Note: This guest post by Avi Itzkovitch offers some clues as to why we can’t seem to put our cell phones down. Avi (@xgmedia) is an Independent User Experience Consultant. He is currently working from his Tel-Aviv Studio XG Media.

Do you constantly check your smartphone to see if you’ve received messages or notifications on Facebook? Does your phone distract you from your studies or work? Do your friends, parents, children, or spouse complain that you are not giving them enough attention because of your phone? You may be addicted.

Do you constantly check your smartphone to see if you’ve received messages or notifications on Facebook? Does your phone distract you from your studies or work? Do your friends, parents, children, or spouse complain that you are not giving them enough attention because of your phone? You may be addicted.

The smartphone has become a constant companion. We carry it throughout the day and keep it by our bedside at night. We allow ourselves to be interrupted with messages from social media, emails and texts. We answer phone calls at times when it is not socially acceptable, and we put our immediate interactions with friends and family on hold when we hear that ring tone that tells us a message is arrived. Something fundamental in human behavior has changed: our sense of phone etiquette and propriety has caused us to get out of whack in our interactions with one another.

So why is it that we allow ourselves to be interrupted? Why do we feel it necessary to answer these calls? Maybe the addiction started long before cell phones even existed, with the advent of the phone itself. Albrecht Schmidt speculates in the Interaction Design Foundation Encyclopedia:

This behaviour is perhaps rooted in the old model of synchronous telecommunication where phone calls were expensive and important – which is less true nowadays. Also, before the advent of caller-id, you could not simply return the phone call as you would not know who had called you unless you actually answered the call. Although technology has changed a lot, some of our behaviours around new technologies are still rooted in an understanding of older technology.

Long before cell phones existed, we began to assign importance to every interaction on our phones because if we didn’t act in the moment, we’d miss the opportunity. With smartphones, however, a host of features make the addictive nature of the phone even worse.

Smartphones Offer Variable Rewards

Schmidt may have a point, but I believe it goes further. Many smartphone users have never experienced the older technology and so, for these users, there are no such roots to old technology. The truth is that we have become so addicted to our phones that we feel compelled to allow these interruptions, even to the point where we no longer even consider them interruptions. Just like an addiction to gambling and the alluring sounds of slot machines, we addictively react to the sounds our smartphone makes. Some have postulated that the theory of variable rewards could explain what makes us addicted to the digital world of Facebook, Twitter and the ringtone from a smartphone.

Nir Eyal has written about this digital addiction on this very blog, with specific attention to the nature of variable rewards. He describes a study by B.F. Skinner in the 1950s that demonstrated the theory of the variable schedule of rewards. Skinner observed that lab mice responded most voraciously to random rewards. When mice pressed a lever, they sometimes got a small treat, other times a large treat, and other times nothing at all. Unlike other mice that received the same treat every time they pressed the lever, the mice that received variable rewards pressed the lever more often and compulsively.

Similar to how mice behave when expecting to receive treats, we eagerly check our phones at the slightest ring or buzz, because the dopamine trigger in our brains compels us to answer. The everyday mundane phone messages that we receive frequently throughout the day are akin to the mice’s small treats. The big treats are the messages that give us pleasure — a message from a friend, a phone call from a loved one, or that funny video we must see. It’s the big treat that is addictive to us and, since we don’t know when that big treat is coming, we “press the lever” compulsively and as often as the ringtone calls us. We are compelled to look at the screen and answer, regardless of where we are and who we are with.

Of course this mobile device addiction goes further. There is a clear human need for self-expression – and especially self-expression that prompts feedback from others (Signs of Facebook Addiction). Our need to immediately share sometimes causes us to forget to enjoy and embrace the moment. This point is illustrated clearly in the YouTube video “I forgot my iPhone,” an exaggerated but accurate reflection of our social behavior. As social animals, we need human contact for emotional and psychological health. Our mobile devices have enhanced our ability to have that contact. They have become a tool important for social interaction.

There ARE Solutions

There are many causes and effects of this addiction, which is also an issue with our computers and other communication devices. However, if we learn to manage this addiction, we can increase our productivity and free up time during the week. It is not only the wasted time that results when we allow ourselves to be interrupted, when staring at the screen, when replying to emails or answering the phone. We also lose valuable time recovering from these interruptions after our attention has been diverted.

This has become recognized as enough of a problem today that we are starting to see some technological solutions being developed, including research on context aware management of interruptions or guidelines for the workplace that could increase productivity For example, a Loughborough University study recommends a set of guidelines for email usage that will increase employee workplace efficiency by reducing interruptions, restricting the use of email-to-all messages and reply-to-all responses, setting the email application to display just the first three lines, and checking for email less frequently.

Freeing ourselves from this addiction will not be easy for many, but there are some technological solutions worth exploring. An android app called “Human Mode” allows the user to disconnect from his mobile phone and become human. It allows the user to place phone calls and messages on hold until a time that’s more convenient. Jake Knapp’s article in Lifehacker, “How I Turned My iPhone Into A Simple, Distraction-Free Device,” describes how a one-week experiment to disconnect from distraction has now become his lifestyle. He makes the point that sometimes we must take serious action to resolve our addictions. But it has always been true that the first step in overcoming any addiction is to admit that it exists. If we identify how the variable rewards of our smartphones are affecting us, we can implement appropriate solutions and break the technological addiction.

Note: This guest essay was written by Avi Itzkovitch.

Photo Credit: Ron Bennetts

September 10, 2013

The Two Words that Created a #1 App

Nir’s Note: In contrast to last week’s post on the power of saying “no,” Eric Clymer shares how a creative attitude helped his team build a #1 ranked app. Eric was the lead developer of the “A Beautiful Mess” app and is a Partner at Rocket Mobile.

In improv comedy, there are really only two words that matter: “Yes, and.” You share a premise, form a scene, create a character, and if everything works out right, kill the audience. Then, you try and do it again with another, “Yes, and.”

In improv comedy, there are really only two words that matter: “Yes, and.” You share a premise, form a scene, create a character, and if everything works out right, kill the audience. Then, you try and do it again with another, “Yes, and.”

Before I began developing for iOS, I performed stand-up and improv as a hobby. I never thought “Yes, and” would apply to the development of software and how to work with clients. But, in my best Louis CK voice, “It TOTALLY did.” This essay is about what I learned working with the artists who hired my company to create “A Beautiful Mess,” an app that went to #1 in the App Store 15 hours after its release (it’s still near the top of the app store).

Elsie Larson & Emma Chapman, the creators of the do-it-yourself blog ABeautifulMess.com are amazing at what they do. Over the past six years, their mix of recipes, photography projects, and other fun arts and crafts ideas, have amassed them a following of over 1.5 million visitors per month.

They came to my company with the premise for a “cute photo app that you add little sayings or doodles to your pictures and share them with friends.” I’ll bet no developer reading this has ever seen “doodles” on a requirements document, let alone it being the only requirement on a non-existent requirements document. When we started the project, I immediately reverted to a character I call the “Defensive Developer.” This character says things like, “We need requirements! There’s a ton of photo apps! What if they want to add on things? It could TOTALLY mess up my architecture! I mean we’re building a house here people!” Defensive Developers love the house analogy by the way. Unfortunately, the Defensive Developer shtick gets old. If he were on stage, his four to six minutes would be joyless and painful.

But this was a role I had played before and so sought comfort in what I knew. I was nervous. “What do artists know about software,” I thought. These women make scrapbooks and cupcakes. How could I possibly explain to them a navigation stack or view hierarchy?

Then, I had an epiphany. I realized they had not entered their projects with a complete, omnipotent understanding either. I realized I was discrediting them and their creative process because it was as foreign to me as Object Inheritance was to them. When we’re scared or insecure we tend to say “no” too quickly. “No” is why most of us can’t be improv comics and for that matter, why so many designers and engineers keep churning-out more of the same old tried-and-true work they’ve done for years. “No” is safe, uncreative, and boring.

Then, I had an epiphany. I realized they had not entered their projects with a complete, omnipotent understanding either. I realized I was discrediting them and their creative process because it was as foreign to me as Object Inheritance was to them. When we’re scared or insecure we tend to say “no” too quickly. “No” is why most of us can’t be improv comics and for that matter, why so many designers and engineers keep churning-out more of the same old tried-and-true work they’ve done for years. “No” is safe, uncreative, and boring.

There are times where “no” is appropriate however. “No” creates a framework through which you can move onto “yes, and”. In fact, you can’t say “yes, and” without starting with “no.” In improv comedy, establishing the premise is how you say “no”. For example, if an improv situation begins with, “You’re a lawyer who’s interviewing for a job,” the comic must go with it. If something occurs outside the constraint, say for example the actor pulls out a stethoscope, the audience will know the premise has been violated. A proper “no” creates the boundaries within which the performer can thrive.

While creating the app for A Beautiful Mess, the period of “no” was brief. The premise of “photo sharing that lets you add texture and content over your photo,” was strong and we went with it. “No” was only used to limit scope and focus the product. “What about a social network of scrapbooks?” — no, that dilutes the product. “What if you could make your own doodle?”– no, that takes away from A Beautiful Mess’s brand. Once we agreed on our basic premise, the process of improvising features and design through “yes, and” was natural.

One particular feature that was internally driven by “yes, and” was what we call our “Intro and Outro” screens. In early versions of the app, the user was dumped into the photo editing view. We needed a way to bookend the creative experience because the user had no real way of knowing what to do next. Users were unsure if they were supposed to select a photo, a background, or just start editing an empty canvas. So we started riffing:

“Can we make it more clear how to get started?” — “Yes, and…”

“Can we make getting started look more like Elsie & Emma’s brand?” — “Yes, and…”

“Can we make the end of the editing experience just as branded and clear?” — “Yes, and…”

“Can you share your creation or start over from the same Outro screen?” — “Yes, and…”

“Can we make the transition from Outro to Intro seamless and one-touch?” — “Yes, and…”

When we were done, we had a clear start and finish to a much better user experience. More importantly, we found our recipe for success.

After a couple months of what became collaborative riffing, requirements emerged, design and development sessions ensued and ultimately, we came out with a beautiful product. In contrast to my Defensive Developers act, a new, much more enjoyable character emerged. He’s much more popular with audiences. People like watching him overcome new challenges. He’s imperfect, flawed, and has a lot to learn, but because he doesn’t get scared and start saying “no”, he gets a lot more laughs.

Note: This guest essay was written by Eric Clymer