Nir Eyal's Blog, page 31

April 22, 2015

Here’s Why You’ll Hate the Apple Watch (and the Important Business Lesson You Need to Know)

If you are among the 19 million people Apple predicts will buy an Apple Watch, I have some bad news for you — I’m betting there is an important feature missing from the watch that’s going to drive you nuts.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t buy one. In fact, I’m ordering one myself. However, this paradox illustrates an important lesson for the way companies design their products.

Rarely are v.1 products very good. How is it, then, that some products thrive despite flagrant shortcomings?

Meet Mr. Kano

To find out why you’ll likely be disappointed by the Apple Watch, meet Professor Noriaki Kano. In the 1980s Professor Kano developed a model to explain a theory of customer satisfaction.

Kano believes products have particular attributes, which are directly responsible for users’ happiness. He discovered that some qualities matter more than others. Kano describes three product attribute types — (loosely translated from Japanese as) delightful, linear, and hygienic features.

A delightful feature is an attribute of a product that customers love but do not expect. For example, if the Apple Watch madeyou coffee every morning, that would be a delightfully surprising feature.

A linear feature, on the other hand, is one users expect. More of that quality increases satisfaction. Battery life is an example of a linear feature of the Apple Watch. You trust that it will last all day but the more juice the battery has, the less you need to charge it, and the happier you are.

Customers are typically able to articulate the linear attributes of a product – “I want it to have long battery life” – whereas by definition they can’t tell they want a delightful feature until they’ve seen it in action. Like knowing the punchline of a joke, if you know what to expect it fails to delight.

Finally, hygienic or “basic” features are must-haves. Customers not only expect these attributes, they depend on them. If the Apple Watch is bad at telling time, for example, you would undoubtedly be very ticked (tocked) off.

Ellen DeGeneres tweeted a sardonic comment that perfectly demonstrates what happens when we make a basic feature sound like a delighter.

Joking aside, Apple CEO Tim Cook knows just how important telling time is for an expensive timepiece. Cook emphasizes that the device is accurate within 50 milliseconds. In addition, when the battery is almost depleted, the watch kicks into “Power Reserve” mode, shutting down everything but the ability to see the time.

Obviously, Apple understands telling time is a hygienic feature. However, when it comes to this basic feature, something is still missing — which finally brings me to what will likely annoy you about the Apple Watch.

Inconspicuous Consumption

A basic attribute of any watch is that it allows wearers to see the time all the time. With a regular watch, checking the time couldn’t be easier. You only need to glance down to know what time it is — not so with the Apple Watch.

To save battery life, the watch goes dark when it thinks you’re not using it. To turn it back on, you have to shake the device with enough momentum to, in Apple’s words, “Activate on Wrist Raise.”

Early Apple Watch reviewer John Gruber, wrote about his experience wearing the device during the end of a meeting with a friend. “It got to 3:00 or so, and I started glancing at my watch every few minutes. But it was always off … the only way I could check the time was to artificially flick my wrist or to use my right hand to tap the screen — in either case, a far heavier gesture than the mere glance I’d have needed with my regular watch.”

Who hasn’t sat across from an overly gabby colleague wondering whether you’ll be late to your next meeting? If we’ve bothered to wear a watch, we expect to be able to see the time at a glance. But if telling the time on your Apple Watch requires a spastic wrist jolt, you’ll curse it.

Gruber continued, “… for regular watch wearers, it’s going to take some getting used to, and it’s always going to be a bit of an inconvenience compared to an always-glance-able watch. It’s a fundamental conflict: a regular watch never turns off, but a display like Apple Watch’s cannot always stay on.”

The problem is significant enough that other smart watch makers already see Apple’s failing as an opportunity. The recently announced Pebble Time for example uses a low-power color e-paper display and never goes dark.

You’ll Still Buy It

Of course, all this doesn’t mean you’re not going to buy the watch. Apple may very well make the wake feature so sensitive that few people are troubled by it. After all, even an obvious wrist shake is better than the inconvenience of checking the time by taking out your phone. However, greater turn-on sensitivity will come at the expense of battery life, a compromise consumers aren’t going to be happy about. To avoid disappointment, keep your expectations low and be prepared to miss some basic features you’d expect from even a cheap watch.

Remember, in the beginning the iPhone had its problems. Apple’s choice of AT&T as the exclusive service provider for the first few generations of the iPhone meant more dropped calls and poor reception. The device was often loathed for its inability to deliver the basic Kano feature customers expected most from a phone, namely, to complete a call!

Over time, the technology improved, but why did people put up with these seemingly fatal flaws for so long? Here again, the Kano model helps us better understand the mindset of consumers.

People kept using (and often praising) the iPhone because the delight factor made up for it’s lack of basic attributes. Mainly, Apple’s App Store and its near infinite variety of nifty solutions provide a constant stream of delightful features even Steve Jobs could never have imagined.

The iPhone still doesn’t make coffee, but it does so many other surprising things you didn’t know it could do when you bought it (from checking your heart beat to identifying constellations) that you overlook its flaws.

As for the Apple Watch, over time Apple will no doubt fix quirks in the first generation just as it did in subsequent iPhone editions. Ultimately, better battery life or alternative screens will keep future versions lit throughout the day. But the real delighter behind the Apple Watch, like the iPhone, will be the apps. Cook recently sent an email to Apple employees announcing that more than 1,000 apps have already been submitted.

Expect future generations of the Apple Watch to have more delightful features customers currently don’t expect like new apps and other improvements. My money is betting that the Apple Watch 2 will come with a forward facing camera, which wearers will discover makes taking pictures even easier and faster than using their phones. And it adds an element of delight every time they take a surprisingly good shot.

We have a love / hate relationship with technology and the Apple Watch will be no exception. By applying Kano’s model, companies can overcome the unavoidable deficiencies that come with new products by building-in features that continue to surprise and impress.

Here’s the Gist:

Dr. Noriaki Kano developed a revealing model for understanding how various product features affect customer happiness.

A “delightful” feature is an attribute of the product customers love but do not expect — for example, new apps in the app store.

A “linear” feature is one the user expects and more of that quality increases satisfaction — think more battery life.

A “hygienic” feature is a must-have. Customers not only expect these attributes, they depend on them — for example, reliably telling the time on a watch.

To save battery life, Apple designed the Apple Watch to only display the time when it thinks you’re looking at it. This violates a hygienic feature and will annoy users.

However, like the first versions of the iPhone, users will forgive the watch’s flaws if the delightful features (namely the apps in the App store) knock their socks off.

Products can win markets by ensuring their “delighter” features compensate for flaws.

The post Here’s Why You’ll Hate the Apple Watch (and the Important Business Lesson You Need to Know) appeared first on Nir and Far.

April 15, 2015

The Secret Psychology of Snapchat

You’ve undoubtably heard of Snapchat, the habit-forming messaging service used by over 100 million people monthly. This week, I teamed up with Victoria Young and Dori Adar to help explain what makes the app so sticky.

We decided that instead of writing a long blog post, we’d share our insights in a slide presentation. Let us know what you think of the format and the content in the comments section below!

The Secret Psychology of Snapchat from Nir Eyal

The post The Secret Psychology of Snapchat appeared first on Nir and Far.

April 2, 2015

Can’t Kick a Bad Habit? You’re Probably Doing It Wrong

I had just finished giving a speech on building habits when a woman in the audience exclaimed, “You teach how to create habits, but that’s not my problem. I’m fat!” The frustration in her voice echoed throughout the room. “My problem is stopping bad habits. That’s why I’m fat. Where does that leave me?”

I had just finished giving a speech on building habits when a woman in the audience exclaimed, “You teach how to create habits, but that’s not my problem. I’m fat!” The frustration in her voice echoed throughout the room. “My problem is stopping bad habits. That’s why I’m fat. Where does that leave me?”

I deeply sympathized with the woman. “I was once clinically obese,” I told her. She stared at my lanky frame and waited for me to explain. How did I hack my habits?

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

The first step is to realize that starting a new routine is very different from breaking an existing habit. As I describe in this video, there are different techniques to use depending on the behavior you intend to modify.

For example, creating a habit requires encoding a new set of automatic behaviors, while breaking a habit requires a different set of processes. The brain learns causal relationships between triggers that prompt an action and the associated outcome. If you’d like to get in the habit of taking a vitamin every day, for example, the key is to place the pills somewhere in the path of your normal routine–say, next to your toothbrush, so you remember to take it each morning before you brush. Doing so daily acts as a reminder until, over time, the behavior becomes something done with little or no conscious thought.

However, breaking an existing habit is an entirely different story, and the distinction is something many people mischaracterize. For example, Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, describes a bad cookie-eating habit that added eight pounds to his waistline.

Every day, Duhigg says, he found himself going to the 14th floor of his office building to buy a cookie. When he began to analyze this habit, Duhigg discovered that the real reward for his behavior was not the cookie itself but the socializing he enjoyed while nom nom nom-ing with co-workers. Once Duhigg figured out that the reward was connecting with friends, he could get rid of the cookie-eating habit by substituting one routine for another. Voilà!

Duhigg echos the popular belief that the key to breaking a bad habit is replacing it with another habit. I’m not so sure.

Maybe replacing cookies with co-workers did it for Duhigg, but what if you’re the kind of person (like me) that loves the hell out of cookies? I was obese precisely because, among many other delicious things, I love cookies and for no other reason than the fact that they taste amazing! For me, ooey gooey chocolate chewy beats chatting it up with Mel from accounting every time.

“Where does that leave me?” the woman in the audience wanted to know. Having struggled with my own weight for years, there was no way I was going to look her in the face and tell her she should chat it up with her co-workers the next time she has a sugar craving. Not going to happen.

Progressive Extremism

When it comes to gaining control over bad habits, like eating food we know isn’t good for us, I shared with her the only thing that has worked for me. I call it “progressive extremism,” and it works particularly well in situations in which substituting one habit for another just won’t do. Before diving into the method I use to transform my habits, follow me back about 20 years.

I was once a vegetarian. As anyone who has made a dramatic shift in diet knows, friends always ask, “Don’t you miss meat? I mean, it tastes so good!” Of course I missed meat!

However, when I began calling myself a vegetarian, somehow what was once appetizing suddenly became something else. The things I once loved to eat were now inedible because I had changed how I defined myself. I was a vegetarian, and vegetarians don’t eat meat.

Saying no to eating animals was no longer difficult. It was no longer a struggle. It was something I just did not do, much in the same way I’d imagine a Hasidic Jew does not eat pork or an observant Muslim does not drink alcohol–they just don’t.

Identity helps us make otherwise difficult choices by offloading willpower. Our choices become what we do because of who we are.

Don’t Versus Can’t

Recent research reveals why looking at our behaviors this way can have a profound impact. A study published in the Journal of Consumer Research tested the words people use when confronting temptation. During the experiment, one group was instructed to use the words “I can’t” while the other used “I don’t” when considering unhealthy food choices. Then the real experiment began.

When people finished the study, they were offered either a chocolate bar or granola bar to thank them for their time. Unbeknownst to participants, the researchers were measuring whether they would take the relatively healthy or unhealthy choice. While 39 percent of people who used the words “I can’t” chose the granola, 64 percent of those in the “I don’t” group picked it over chocolate. The study authors believe saying “I don’t” rather than “I can’t” provides greater “psychological empowerment.”

I was meat-free for about five years, and during that time resisting certain foods was not that difficult because it was consistent with how I saw myself. “I don’t eat meat,” was tied to my identity as a vegetarian.

If not eating meat was easy when it was something I just didn’t do, why couldn’t the same technique be used to stop other unhealthy habits? It turns out it most certainly can.

Here’s How it Works

First, a disclaimer. This technique only works for triggers that can be removed from your environment–for instance, this doesn’t work for quitting a nail-biting habit unless you’re looking to dispose of some digits.

Start by identifying the behavior you want to stop. For example, say you’d like to stop eating processed sugar. Taken all at once, cutting out the sweet stuff is too big of a goal for most people to quit cold turkey.

Instead, think of just one specific food you’d like to cut from your diet. However–here’s the important part–it needs to be something you wouldn’t really miss and it needs to be forever.

Overwhelming research reveals diets don’t work because they are temporary fixes. If you imagine you’ll get to eat Goobers some day when you’re thinner, this technique won’t work. Temporary diets do nothing but train the brain to binge eat.

To become part of your identity, the commitment needs to be forever, just as vegetarians believe they’ll eat the same way for the rest of their life–it’s who they are.

The mistake most people make is they bite off more than they can chew (excuse the pun). The key is to only remove the things from your diet you won’t really miss. For example, do you like candy corn? I sure don’t. As a kid, the stuff was always the dregs of my Halloween haul. For me, removing candy corn for life was no big deal, so it was first on my list. I don’t eat candy corn and I never will. Done!

Next, write down what you no longer eat and the date you gave it up for good. Writing this down marks the shift from a temporary “can’t” to a permanent “don’t.” Remember, the things you give up have to be easy enough to give up for the rest of your life.

The next step is to wait. This method takes time. When you’re ready, reevaluate what else you can do. Find another trigger to remove that meets the criteria of something you can give up for life that you wouldn’t really miss. For me, I decided to never have sugary carbonated drinks at home. I could still have them elsewhere, just not inside the house. Easy peasy.

If the commitment feels like too much, you’re doing too much. Each step needs to feel almost effortless, no big deal, but involve something you can be proud to give up forever.

For example, when I wanted to stop a bad habit of mindlessly surfing the internet and reduce the online distractions in my life, I didn’t quit the Web entirely. I quit one simple thing I wouldn’t miss and intend not to do it for life. I don’t read articles in my Web browser during working hours–ever! Instead, every time I see something that looks interesting, I use an app called Pocket to save it for later (see more about how Pocket works here).

The process of unwinding bad habits takes years, but progressive extremism is an effective way I’ve found to stop behaviors that weren’t serving me. Occasionally, I look at all the unhealthy things that no longer control me the way they once did, and if I feel up to it, I find new bad habits to slay.

By slowly ratcheting up what you don’t do, you invest in a new identity through your record of successfully dropping bad habits from your life. It may start small, but over time, it adds up to a whole new you.

Here’s the Gist:

The process for stopping bad habits is fundamentally different from forming new ones.

Existing behaviors etch a neural circuitry that makes unlearning an association between an action and a reward extremely difficult.

Whereas learning new habits follows a slow progression, stopping old behavioral tendencies requires a different approach.

A process I call “progressive extremism” utilizes what we know about the psychology of identity to help stop behaviors we don’t want.

By classifying specific behaviors as things you will never do again, you put certain actions into the realm of “I don’t” versus “I can’t.”

Thanks to James Clear for his help with this post.

The post Can’t Kick a Bad Habit? You’re Probably Doing It Wrong appeared first on Nir and Far.

March 25, 2015

Everything Is Obvious (Once You Know The Answer) Book Review

Here’s the Gist:

Here’s the Gist:Duncan Watts is a sociologist and principal researcher at Microsoft Research. His latest book is Everything Is Obvious (Once You Know the Answer): How Common Sense Fails Us .

Personal preference, though not entirely arbitrary, is likely constructed and justified on the fly.

According to Watts, the problem with prediction is not that we’re good or bad at it, but rather we are bad at distinguishing predictions that we can make from those we can’t.

Business should embrace “strategic uncertainty” and “measure-and-react strategies.”

Nir’s Note: This book review is by Sam McNerney. Sam writes about cognitive psychology, business, and philosophy.

At a special event in the Yerba Buena Center in San Francisco, the CEO of Apple Tim Cook riffed on Apple’s latest gadget, the Apple Watch. “It’s the most personal device we’ve ever created,” Cook said. “It’s not just with you; it’s on you. And since what you wear is an expression of who you are, we designed Apple Watch to appeal to a whole variety of people with different tastes and preferences.”

In just one sentence, Cook perfectly captured the genius of Apple, insisting that technology is not just about selling great products but merging them with lifestyle and identity. We no longer use electronics. They’ve become an expression of who we are.

The seductive appeal of Apple raises a fascinating question about how the human mind calculates preference. For most of the 20th century, social scientists believed that people possessed a set of fixed preferences. We may not have a detailed understanding of these preferences—we may not know why we like a certain wine or song or a burger joint—but we believe that there are things in the world that we prefer.

In the last few decades, psychologists have discovered that this view of human nature is at best limited. Research shows that the music playing in a liquor store influences our choice of wine, that the font and size in which something is written can make it more or less credible, and that we’re more likely to recycle hotel towels after reading that everyone else does. We report that we love Wes Anderson films, but when the weekend arrives, we opt for Michael Bay’s Transformers.

These studies are not making the rather innocuous observation that smart marketing matters, or that self-reports are unreliable. They reveal the more groundbreaking finding that the notion of “true” preference might be a myth. More likely, preferences, though not entirely arbitrary, are pieced together and justified on the fly.

Just So Stories

The idea that preference is constructed is one of the essential themes of Duncan Watts’ Everything is Obvious: Once You Know the Answer. Watts’ broader point is that common sense—a seemingly useful tool for understanding the world and oneself in it—is mostly an inexhaustible source of just-so stories designed to confirm purpose and instill agency where both may not exist. Common sense tells me that I’m a good person willing to donate my organs for the greater good. More likely, I’m an average guy who, like others, is highly susceptible to the default choice on the DMV form.

If our folk theories of individual behavior are systematically flawed, then our mental models of collective behavior are even worse. Trends, memes, cultural icons—everything from Shakespeare to Hush Puppies emerge from the collective behavior of human beings. We get together in groups to share information, spread rumors, meet new people, form new friendships, talk about what we like to eat, what we like to watch, and what we think is right or wrong.

According to Watts—a sociologist, physicist, and principal researcher at Microsoft—when we explain social phenomena, we tend to focus on the thoughts or intentions of the individual parts, or fictitious clusters like “the market” or “the economy.” Yet explanations that rely on a single cause to explain complex social phenomena typically gloss over the exceedingly intricate and chaotic nature of human interaction.

Foibles of Common Sense

“..the Mona Lisa is famous because it’s more like the Mona Lisa than anything else.” Image credit: Wikipedia Creative Commons

For instance, Watts wonders why Mona Lisa is the most famous painting in the world. Most people point to its unique inherent qualities—the gauzy finish or the subjects’ enigmatic smile. “But what we’re really saying,” Watts writes, “is that the Mona Lisa is famous because it’s more like the Mona Lisa than anything else.”

For many centuries, the Mona Lisa was an obscure masterpiece owned by notability. In 1911, a disgruntled Louvre employee named Vincenzo Peruggia stole the Mona Lisa and smuggled it to its “rightful” home in Italy. Italians treated Peruggia like a hero, the French threw him in jail, and Marcel Duchamp adorned a mustache and goatee on a reproduction in 1919. The succès de scandale hurled the Mona Lisa into the spotlight while that enigmatic smile went unchanged.

How we explain group behavior also reveals the limits of common sense explanation. Watts considers a famous survey, The American Soldier, conducted by the U.S. Military during World War II involving 600,000 servicemen. In the 1960s the brilliant sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld discussed one of the survey’s major findings: “Men from rural backgrounds were usually in better spirits during their Army life than soldiers from city backgrounds.” It makes sense. Soldiers from rural backgrounds were happier because they were better accustomed to dealing with harsh living standards. Effete city intellectuals, on the other hand, struggled to cope with the brutal psychological realities of war. It’s a fairly obvious finding… Right?

Image credit Wikipedia Creative Commons

Not exactly. Lazarsfeld revealed that this “finding” is the exact opposite of what the survey actually uncovered. Soldiers from the city, not rural areas, were happier during wartime. Of course, had Lazarsfeld told readers the correct answer first, they would have just as easily constructed a narrative about why it made sense—why, for example, city dwellers were used to crowded conditions, stricter social etiquette, and command and control style hierarchies. “If the correct answer and its exact opposite appear equally obvious, then, as Lazarsfeld puts it, ‘something is wrong with the entire argument of ‘obviousness.’”

Thinking More Clearly

In the final third of Everything is Obvious, Watts explores the foibles of prediction and strategic planning. We learn less from history than we think we do, he says, and this illusion further distorts our ability to forecast the future.

Watts prescribes a few heuristics to help us think more clearly about the future. The first is so simple that most people ignore it: distinguish domains in which we can confidently rely on data to make predictions from domains where randomness plays a big role or domains dominated by unexpected shocks. Predicting when Halley’s comet will next swing by Earth is easy because physical laws are stable—figure out the laws, figure out the path of the comet. Predicting who will win the next Super Bowl is harder because chance plays a significant role over the course of an NFL season, even though the rules of football and the dimensions of the field are fixed. Predicting the stock market is probably impossible, especially over the long term. Unlike physics and football, it is prone to unforeseeable shocks and sensitive to smart random variations.

Forecasting is such a difficult business not just because reliable data is hard to find but also because it’s hard to know what data matter. To paraphrase Watts, humans are generally good at perceiving which factors are relevant to a particular problem—a pitchers’ ERA is a better indicator of future performance than his relationship status—but they are generally bad at judging how important one factor is relative to another—is ERA more important than the Wins? What about more obscure baseball statistics like FIP and K/9 ratio?

And what’s worth predicting in the first place? “Making the right prediction is just as important as getting the prediction right,” Watts says.

One solution is to embrace “strategic uncertainty.” Watts details Michael Raynor’s book The Strategy Paradox, in which Raynor convincingly demonstrates that in many cases, the main cause of strategic failure, such as Sony’s MiniDisc, is not bad strategy but bad luck. The vision was clear, leadership strong, and execution flawless, but a black swan emerges—the Internet, Automobiles—and undermines everything. “Strategic uncertainty” assumes that even the best-laid plans are prone to unexpected changes and plans for a range of scenarios—even scenarios that seem unimaginable.

Image Credit Wikipedia Creative Commons

Watts also endorses the “measure-and-react strategy.” The Spanish clothing retailer Zara, for example, admits that it cannot anticipate what shoppers will buy next season. Instead, it pays agents to scour shopping malls to observe what consumers are already wearing. Then, a team creates a massive portfolio of the styles, fabrics, and colors that are trending and sends the portfolio to stores where everything is tested. Zara’s flexible and swift manufacturing and distribution makes it possible to design, produce, and ship new garments anywhere in the world in just over two weeks.

Of course, the logic behind “measure-and-react” has become widespread among Internet companies. Before Google or Huffington Post or Buzzfeed introduce a new feature, they test it, usually on a small portion of users. With feedback and observational metrics, it’s easier for these companies to know, compared to the opinion of one expert, what to keep and what to abandon.

“Whenever it comes to questions of business strategy or government policy, or even marketing campaigns and website design, we must rely less on our common sense and more on what we can measure,” Watts says.

When Steve Jobs famously remarked that people don’t know what they want until you show it to them, he probably wasn’t contemplating the details of the psychology of preference construction. And yet, he perfectly captured decades of research showing how common sense reasoning and everyday introspection can lead us astray. Apple geniusly merges technology with lifestyle not by tapping into the pre-existing identity of its customers but by creating one. Apple doesn’t sell products that we prefer; it creates the preference in the first place.

This distinction might sounds like a snobby cultural critique, a warning that Apple is shamelessly exploiting a vulnerable part of our minds. In reality, Apple is simply thinking clearly about how common sense actually works, insisting that what customers say they like is not a good indicator of what they’ll end up buying. This gap–the gap between what we say and what we do, what we think will happen and what actually happens–is a fascinating component of human psychology that Watts brilliantly weaves into Everything Is Obvious.

“The paradox of common sense,” he concludes, “is that even as it helps us makes sense of the world, it can actively undermine our ability to understand it.”

The post Everything Is Obvious (Once You Know The Answer) Book Review appeared first on Nir and Far.

March 16, 2015

Your Fitness App is Making You Fat, Here’s Why

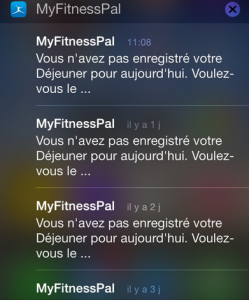

Fitness apps are all the rage. An explosion of new companies and products want to track your steps and count your calories with the aim of melting that excess blubber. There’s just one problem — most of these apps don’t work. In fact, there is good reason to believe they make us fatter.

One study called out “the dirty secret of wearables,” citing that “these devices fail to drive long-term sustained engagement for a majority of users.” Endeavour Partners’ research found “more than half of U.S. consumers who have owned a modern activity tracker no longer use it. A third of U.S. consumers who have owned one stopped using the device within six months of receiving it.”

While the report mentioned several reasons why people don’t stick with these tracking devices, my own theory is simple, they backfire. Here are three surprising reasons why fitness apps may be making us less happy and more flabby.

1 – Not Just Calories In, Calories Out

The first reason fitness apps make us fat is that almost all of them are based on a pervasive myth. Most of these gadgets and apps attempt to push people to eat less and exercise more. They ask users to track what they eat and record their physical activity in order to quantify whether dieters intake a surplus of calories for the day. Eat too much or move too little, the thinking goes, and you’ll get fat, right? Not exactly.

Evidence that the calories in, calories out theory is too simplistic is plentiful. For example, doctors have known for some time that certain medications cause patients to gain or lose weight by changing hormone levels in the body. If putting on pounds was just a matter of “energy balance” then these medications shouldn’t make people heavier. But they do.

Drugs aren’t the only things that can change hormone levels. Certain foods prompt the body to store fat by spiking the release of hormones like insulin. According to Dr. Peter Attia, co-founder of the Nutrition Science Initiative, “All calories are not created equally … The energy content of food (calories) matters, but it is less important than the metabolic effect of food on our body.”

To most fitness apps, a calorie of high-fructose corn syrup is the same as a calorie of protein despite the fact that science, and our bodies, tells us otherwise. Clearly, a calorie isn’t just a calorie and by perpetuating this untruth, fitness apps help people tack on the pounds instead of shedding them.

2 – You Won’t Exercise Yourself Thin

Exercise is probably bad for you. Did you read that right? Let it sink in.

For one, exercise causes many people to overeat by giving them permission to indulge. The phenomenon is called moral licensing — the psychological tendency to splurge in one area of our life when we’re being good in another.

Moral licensing is why a study found people “are more likely to cheat and steal after purchasing [environmentally] green products as opposed to conventional products.” It’s why other studies found participants who believed multivitamin pills provided significant health benefits also exercised less, were less likely to choose healthy food, and smoked more cigarettes.

The phenomenon accounts for why many runners gain weight while training for a race. They expend more calories during their runs, but by rewarding themselves with indulgences throughout their day like an insulin-spiking post-workout “sports drink,” they ultimately negate many of the health benefits of exercise.

There’s another reason people rarely exercise themselves thin. According to science writer Gary Taubes, “The one thing that might be said about exercise with certainty is that it tends to makes us hungry. Maybe not immediately, but eventually.” Though Taubes cites extensive evidence backing his claim in his multiple books on the topic, the idea also makes intuitive sense. However, most fitness apps ignore the fact we work up an appetite.

When we exercise, the blood stream is drained of glucose so the body activates an uncomfortable sensation to get us to refuel. Hunger pangs, or the fear thereof, drive our search for sustenance.

For roughly 95% of the 200,000 years our species has existed, food was relatively hard to come by. Today however, sugar-laden calorie bombs are cheap, delicious, and readily accessible. Whereas our ancestors laboriously cracked nuts with their hands and primitive tools or gnashed animal caracas with their powerful jaws, we sip pre-masticated Mega Mango Smoothies at Jamba Juice (with 52 grams of sugar in the smallest 16 ounce size).

Exercise does us in by making us hungrier throughout the day and since our food is so full of stuff that makes us fat, we become more likely to over-consume without noticing. A few extra bites at lunch and an extra piece of fruit after dinner and we’ve negated the 300 calories we burned running for 30 minutes on the treadmill.

I’m not saying all exercise is bad for all people. I enjoy running three days per week and we’ve all heard the countless studies supporting the benefits of exercise. However, people don’t live in a behavioral vacuum and there are deeper physiological and psychological influences we must be aware of. Not only are we hungrier but we are more likely to yield to temptation thinking we’ve already paid for our sins in the gym.

Too many fitness products emphasis sweating the pounds away without establishing a base of proper nutrition. People look to their fitness products as authorities for what’s good for them but unfortunately most fitness trackers perpetuate behaviors that backfire in ways we don’t even notice and certainly don’t intend.

3 – Want To, Not a Have To

What’s the best workout in the world? The answer is the one you actually do. However, most people don’t sustain their lofty exercise goals. When they fail, people blame themselves instead of the poorly designed weight-loss system. The cycle of yo-yo dieting and subsequent self-loathing makes us fat.

Most fitness apps fail because they miss a critical component of what it takes to change long-term behaviors. For my recently published book, HOOKED, I studied some of the most successful consumer technology companies in the world. I looked into what makes Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and the iPhone so good at changing user behavior. My hope was that what I learned could be utilized by those who seek to change habits for good. I discovered these products and services had several common attributes, among them the fact that using them is fun. In contrast, by and large fitness apps are a drag. As the data regarding long-term usage of these services shows, fitness trackers that make people do things they hate doing, fail to change long-term behaviors.

The psychological phenomenon of reactance tells us people tend to resist doing things they feel coerced into completing. Attempting to form habits for behaviors people feel they have to do instead of want to do just doesn’t work over the long-term. Sure, we can starve ourselves for a while or pay homage to the elliptical machine for a few weeks but eventually we give up if it’s not fun. That’s why the only people who sustain using these bossy services are those who were already tracking their activity and nutrition before they started using the app, or the relatively few who somehow learned to enjoy the behaviors for their own sake.

To date, the burgeoning fitness app industry has relied too heavily upon game-like incentives to motivate behavior — but games invariably come to an end. When the novelty of extrinsic prizes like points, leaderboards, and step counts wear off, the experience becomes monotonous and users quit. The next generation of fitness apps need to focus on helping users enjoy the activity itself instead of making artificial and often frivolous goals the aim.

As for me, I run because I enjoy running, not because an app tells me to. I learned to love exercise without setting strict fitness goals. Instead, I found Minimum Enjoyable Actions I could fit into my schedule regularly because I enjoyed the exercise itself.

Though I’ve taken fitness trackers to task, herein lies the opportunity for the future of health tech. By finding ways to help people learn to love physical activity, moral licensing and reactance are kept at bay and users are more likely to continue to do the activity in the future. In addition, products that help us eat the right foods, not just fewer calories, are needed.

Someday, a host of new technologies will finally fulfill the promise of helping us maintain a desirable weight and conceivably live better, longer lives. We’re just not quite there yet. Until then, we should be cautious of products that attempt to change our bodies without first understanding our minds.

Here’s the Gist:

Most fitness apps and activity trackers operate from the pervasive myth that all calories affect the body in the same way. They don’t!

People who dislike physical exercise elicit a psychological phenomenon called “moral licensing,” which makes them more likely to over consume to reward their hard work. Without a base of proper nutrition, we can’t exercise ourselves thin.

The psychological phenomenon of “reactance” shows people tend to resist doing things they feel coerced into completing. Attempting to form habits for behaviors people feel they have to do instead of want to do does not work over the long-term.

Fitness trackers that don’t differentiate the types of calories people consume and don’t help users learn to enjoy exercise perpetuate the problems associated with yo-yo dieting and make people gain weight over time.

If you found this article interesting, please share it. Thanks!

The post Your Fitness App is Making You Fat, Here’s Why appeared first on Nir and Far.

March 3, 2015

The Psychology of Notifications: How to Send Triggers that Work

In his famed experiments, Ivan Pavlov trained his dogs to associate mealtime with the ring of a bell. Pavlov found he could elicit an involuntary physical response in his dogs with a simple jingle. Every time his bell rang, the dogs began to salivate.

Today, the beeps, buzzes, rings, flags, pushes, and pings blasting from our phones prompt a similar response. They are the Pavlovian bell of the 21st century and they get us to check our tech incessantly.

However, as powerful as these cues are, people are not drooling dogs. Your product’s users can easily uninstall or turn off notifications that annoy them.

What makes an effective trigger? How can you be sure that the notifications you’re sending are welcome and lead to higher engagement instead of driving users away? Below are a few tenets of notifications that engage users, instead of alienating them.

1 – Good Triggers are Well Timed

Great apps create an instantaneous link between an emotional itch and the salve the service provides. To create this mental connection, effective messages are thoughtfully timed. There are two kinds of triggers, as described in Nir’s book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

External triggers are cues in the user’s environment that provide information for what to do next. A button telling the user to “click here,” “tweet this,” or “play now,” are all examples of external triggers.

Internal triggers, on the other hand, rely upon associations in the user’s mind to prompt actions. The most frequent internal triggers are emotions. When we’re feeling lonely, we check Facebook. When we’re uncertain, we Google. When we’re bored, we watch YouTube videos, check Reddit or scroll Pinterest.

Habit-forming products align the external trigger (a push notification for example) with the moment when the internal trigger is felt (say the feeling of uncertainty or boredom). The closer the timing of the external trigger is with the internal trigger, the sooner the association is formed.

For instance, imagine you have a connecting flight and only forty minutes to spare. As soon as you land, you’re worried about which gate to go to next and how long it will take you to get there. You turn your phone off airplane mode and voilà: there’s a notification from your airline with all the right information. Your boarding time, gate number, and whether your departure is on time, are presented at the moment you’re most likely to feel anxious. Now you can get to your next connection without having to frantically scan one of the terminal’s crowded departure screens. By providing information at the moment the user is likely to need it, the app builds credibility, trust, and loyalty.

2 – Good Triggers are Actionable

Good triggers prompt action while vague or irrelevant messages annoy users. It’s important that a trigger cue a specific, simple behavior.

For instance, notifications from Whatsapp make it easy for users to check the latest update on a thread and respond accordingly. Their notifications are simple, focused, and instruct the user what to do next.

The intended action prompted by the notification can also occur outside the app itself. Google Now tells users when to leave for an appointment based on what it knows about their location, traffic conditions, and mode of transport. Google Now can tell the user: “Leave by 11:25 am to arrive on time.”

Google Now sends actionable notifications.

3 – Good Triggers Spark Intrigue

A bit of curiosity goes a long way when it comes to prompting specific, intended actions. Triggers entice users to swipe to learn more when there’s some mystery regarding what they might find if they do.

Timehop, for instance, sends a cheeky notification reading, “No way, was that really you?,” and prompting the users to open the app. To see the photo, users need to simply swipe. It helps that Timehop’s messaging is lightweight and humorous enough to be out of the ordinary.

Timehop prompts intrigue with its notifications.

Of course, if Timehop used the same copy everyday, it would prove less compelling over time. Variability stimulates curiosity, and can make a notification worth checking. The element of surprise or a bit of the unexpected can make users more likely to respond to a notification so don’t send the same notification again and again.

Don’t send the same message again and again.

Building for the Ping

All of us experience the annoyances of poorly designed notifications and triggers. Irrelevant, ill timed, or repetitive triggers grate on us like fingernails on a chalkboard. The worst offenders bare the wrath of fickle users who stop using, unsubscribe, or uninstall products that don’t respect the rules of building good triggers.

By integrating thoughtful, interesting, and actionable triggers that are closely coupled with users’ deeper needs, designers can build notifications that people look forward to engaging with.

Photo Credit: William Hook

Note: Ximena and Nir will be speaking about designing engaging products at this year’s Habit Summit.

The post The Psychology of Notifications: How to Send Triggers that Work appeared first on Nir and Far.

February 23, 2015

How Technology Tricks You Into Tipping More

You are unconsciously paying more. (Photo credit: Digital Dispatch)

My taxi pulled up to the hotel. I got out my credit card and prepared to pay for the ride. The journey was pleasant enough but little did I know I was about to encounter a bit of psychological trickery designed to get me to pay more for the lift. Chances are you’re paying more, too.

Digital payment systems use subtle tactics to increase tips, and while it’s certainly good for hard-working service workers, it may not be so good for your wallet.

A new report by the tech research firm Software Advice discovered that digital point-of-sale terminals, like the one in my cab, increase the frequency and amount of tips left by customers. What’s the secret behind how these manipulative machines get us to pony up?

The Power of Defaults

A recent Iowa State study cites a mobile payment company that effectively “nudges consumers” into tipping. Study author Kam Leung Yeung, writes, “Upon swiping their credit or debit card, consumers then need to choose among … preloaded tip amounts (e.g. 15 percent 20 percent, or 25 percent), or to enter their customized tip amount, or decide not to tip at all.” This simple interface “increased the proportion of tipping by 38 percent.”

How did tipping increase so dramatically? Clearly the service wasn’t 38 percent better. Patrons didn’t suddenly become more generous. Rather, the higher tipping is a result of a few intriguing design decisions by the payment processor.

For one, digital interfaces make it just as easy to tip as to not tip — a marked change from the way we used to pay in the past. When cash was king, anyone not wanting to give a tip could easily leave the money and dash. “Whoops, my bad!” However, with a digital payment system the transaction isn’t complete until the buyer makes an explicit tipping choice. Clicking on the “No Tip” button is suddenly its own decision. This additional step makes all the difference to those who may have previously avoided taking care of their server.

Making sure customers don’t forget to tip is certainly a good thing. But there is another subtle nudge that gets those who intend to tip to give even more than they otherwise would.

Tipping conventions say the appropriate amount to tip a taxi drive is in the range of 10 percent to 18 percent. However, making the default choices 15 percent, 20 percent or 25 percent bumps up the tip in two ways.

First, users tend to take the easiest route; they do whatever requires the least amount of physical and cognitive effort. In this case, you’re less likely to customize the tip because doing so necessitates more thinking and more clicking. Picking a preloaded amount is simply easier than changing the tip amount even if you know you’re overtipping.

Second, offering three choices utilizes the anchoring effect to nudge people into picking the middle tip option. The vendor knows you likely won’t pick the least expensive amount — only cheapskates would do that. So even though 15 percent is squarely within the normal tipping range, by making it the first option, you’re more likely to chose 20 percent. Picking the middle-of-the-road option is in-line with your self-image of not being a tightwad. Therefore, you tip more and you’re not alone. The New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission reported tips increased from 10 percent to 22 percent on average when the new payment screens were turned on.

Reducing the Pain of Paying

These systems also make it easier for customers to let go of their money. In another sense, they eliminate what Duke Professor Dan Ariely calls the pain of paying. Ariely states, “The agony of parting with our money has to do with the saliency of [seeing] this money going away.” In other words, the less real money feels, the less painful it is to spend and subsequently, we spend more of it.

The payment processors have followed in the footsteps of another industry that has effectively reduced the pain of paying — the gambling industry. Step into any casino on the Las Vegas strip and you’ll notice slot machines by and large no longer take cash. To take a spin on a gambling machine today, money must first be loaded onto a loyalty card. As soon as the card is dipped into the machine, it turns into points. Why did the casinos yank the cash out of their slot machines? Simple. They know gamblers will spend more when their money doesn’t feel like money.

Similarly, whereas handing over a tip with cash once meant physically feeling the money as it left your wallet, digital payments systems obfuscate the act of paying into something much less tangible. With digital payment systems, customers simply press a few buttons with their finger and the funny money is gone — just like in a casino.

Yeung, the Iowa State study author, calls for government action to protect consumers from being taken advantage of by these systems. He states “policy makers should further explore alternative payment interfaces that can balance the convenience of paying and its corresponding spending-regulatory effect.” The issue Yeung raises with these systems is that they make people pay more without realizing it.

Certainly, digital payment systems aren’t all bad. For one, they improve customers’ experiences by making transactions easier and faster, eliminating the antiquated card-swiping and pen-signing systems still used by most retailers today. They also give bad tippers and non-tippers an extra nudge to tip properly. Clearly, service workers deserve to be tipped, and tipped well, for a job well done.

However, for the average person just trying to do the right thing, these devices can mean hundreds if not thousands of dollars spent unintentionally. As we quickly pay while getting out of a cab, for example, most of us don’t have the time or mental bandwidth to think about how the way we’re paying affects how much we are paying.

During these times, our brain is operating out of habit, and we quickly act with little or no conscious thought. We remain woefully unaware of how these interfaces leverage our deeper psychology to change our behavior by design.

The post How Technology Tricks You Into Tipping More appeared first on Nir and Far.

February 9, 2015

Habit Summit is Coming!

I’m thrilled, giddy even! This year’s Habit Summit promises to be a one-of-a-kind event.

On March 24th at Stanford University, the best in the business will share their knowledge of how to drive customer engagement using the power of habits.

You’ll hear Ryan Hoover, the CEO and Founder of Product Hunt, share how he built a company TechCrunch just called the “Best New Startup” of the year.

Jake Knapp and Daniel Burka from Google Ventures will share techniques any team can use to design and build great products.

James Clear will teach you how to improve your products by improving your personal and work habits.

You’ll also meet 350 attendees from around the world, all interested in building products that move people.

There are many other amazing speakers, check-out HabitSummit.com for more.

The Habit Summit sold out last year but tickets are available now for $150 off the final call price. Get your ticket before they’re gone at: http://habitsummit2015.eventbrite.com

As a special thanks to blog readers, enter the promotional code “NirAndFarFriends” to receive $50 off the general admission price.

See you there!

Nir

PS – I’m giving my half-day Hooked Workshop on how to build habit-forming products in San Francisco the day before the Habit Summit. See: habitsummit2015.eventbrite.com for details

The post Habit Summit is Coming! appeared first on Nir and Far.

February 3, 2015

Latest Tech Trend: Products to Reduce Distraction and Boost Willpower

Four minutes into pitching the wonders of his invention to an influential reporter, Patrick Paul gets hit with the kind of snarky comment startup entrepreneurs dread.

Four minutes into pitching the wonders of his invention to an influential reporter, Patrick Paul gets hit with the kind of snarky comment startup entrepreneurs dread.

Paul is the founder of Hemingwrite, a “distraction free writing tool with modern technology like a mechanical keyboard, e-paper screen and cloud backups.” At first glance, the Hemingwrite could be mistaken for an old-school typewriter inlaid with a Kindle display. Despite its “modern technology,” it looks like a 1980s throwback from Radio Shack. Two gaudy dials sit on either side of chunky black plastic and a huge red button — which could easily be mistaken for an ignition switch — turns it on. The company website calls this esthetic “retro.”

Despite its looks, the Hemingwrite has struck a nerve. The company quickly surpassed its $250,000 crowdfunding goal on Kickstarter and sold hundreds of units of a machine that hasn’t even been manufactured yet.

At $399 a pop, the Hemingwrite costs much more but does much less than just about every personal technology on the market. But that, according to the company, is exactly the point.

By design, the Hemingwrite has no web browsing, no social media functionality, and no apps. The device promises to “set your thoughts free” by reducing distraction and is for people who find it difficult to focus amid all the pings, buzzes, and notifications that come with working on a PC.

Paul tells a tech reporter, “With the Hemingwrite, we burn that bridge. There is no way to get on Facebook, Reddit, or Twitter. You can only write.” Then comes the snark. The reporter quickly retorts, “Right, unless you pull your phone out of your pocket.” (Insert Homer Simpson-esque “D’oh!” here.)

Tech Versus Tech

Maybe the Hemingwrite isn’t for everyone. However, it is an example of a new breed of products designed to help us regain control over digital distractions.

To some, the idea of using a dumbed-down word processor is silly. Why buy an expensive box that does less than a PC? The answer for many bleary-eyed workers is: because I need to get stuff done.

Jonathan Franzen, the man Time Magazine calls the “Great American Novelist,” uses a distraction free tool to write his masterful works — though his is homemade. According to a 2010 cover story, “He uses a heavy, obsolete Dell laptop from which he has scoured any trace of hearts and solitaire, down to the level of the operating system. Because Franzen believes you can’t write serious fiction on a computer that’s connected to the Internet, he not only removed the Dell’s wireless card but also permanently blocked its Ethernet port. ‘What you have to do,’ he explains, ‘is you plug in an Ethernet cable with superglue and then you saw off the little head of it.’”

Franzen’s methods may seem extreme but desperate times call for desperate measures. In the battle for attention, the only solution may be periodic forced amputation from the Net. Franzen is not alone in devising ways to kill distraction.

A software developer named Ned Batchelder published code for an app he created to restrict his use of the very site he posted to. Stack Overflow, a site known to nearly every programmer on the Web, has comment strings related, “How can I keep from getting addicted to Stack Overflow?” The site even has built-in breakers to prevent overuse. According to Stack Overflow co-founder, Jeff Atwood, “The current system is designed to reward continued participation, but not to the point that it creates obsession. Programmers should be out there in the world creating things too.”

The struggle to not do what we ought not to do is nothing new. Thousands of years before Facebook and YouTube, the ancient Greeks used the word “akrasia” to describe the act of doing one thing when you know you should do another. The term appears several times in the New Testament.

However, what is new about our struggle with distraction today is that we have yet to develop what famed investor Paul Graham calls the “social antibodies” needed to inoculate ourselves from the negative aspects of addictive products. Although personal technology is an indispensable and largely beneficial part of our everyday lives, we haven’t yet worked out the kinks and faults associated with too much of a good thing.

Having written a book on what makes technology habit-forming, I believe products will become harder to resist as companies leverage new ways to keep users coming back. However, just because I understand how products hook us doesn’t mean I don’t struggle with distraction myself. In fact, in the words of Richard Bach, “You teach best what you most need to learn.” I’ve had to devise my own behavioral hacks to regain control over my own bad tech habits. I’ve even revived my sex life by using thoughtful (and perhaps extreme) ways to turn off tech.

Attention Retention

Given the growing need, technologies that help people stay focused so they can do the things they really want to do could be a boon for entrepreneurs and investors. These technologies could be the social antibodies we’ve been waiting for.

A host of new products have recently come to market offering respite from the constant barrage of attention-sucking diversions like email, news sites, and social media. They promise to keep us focused so we can actually get work done instead of mindlessly checking and pecking at our screens.

I’m eagerly awaiting these new technologies that seek to fix the flaws of old technologies. However, like any nascent trend, I anticipate there will be many failures before we’ll see any big successes.

The biggest problem with these technologies is that they don’t exhibit many of the important traits found in products that change behavior for good. For one, they’re not fun to use. Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram, among other habit-forming technologies, changed users’ daily routines by being inherently enjoyable. I worry many of the products attempting to keep us focused are things people feel they have to use instead of want to use. Pasting-on cheesy game mechanics like points and badges won’t solve the problem, but my guess is that products that can make focused work easier and more enjoyable will succeed.

To be clear, my doubts aren’t fatal flaws, just challenges I’m sure smart innovators will overcome. Of course, predicting the market potential of this new breed of products is nearly impossible, but over the next few years I expect to see many more companies emerge to help us live and work better by helping us put technology in its place.

What Do We Call It?

Here’s where I need your help …

What tools or products do you use to stay focused? Let’s start a list of the best tools and techniques in the comments section below.

There still isn’t a name for this industry – yet! Here are some of my ideas: concentration technology, attention tools, anti-distraction devices, focus tech. I’m sure you can do better. What do you think we should call it? Leave an idea in the comments section below.

The post Latest Tech Trend: Products to Reduce Distraction and Boost Willpower appeared first on Nir and Far.

January 28, 2015

3 Ways to Make Better Decisions Using “The Power of Noticing”

Nir’s Note: This book review is by Sam McNerney. Sam writes about cognitive psychology, business, and philosophy.

In Moneyball, Michael Lewis tells the story of Billy Bean, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics who transformed the A’s using sabermetrics, the data-driven approach to understanding baseball. Bean noticed that instead of using data to predict player performance, baseball professionals relied on faulty intuitions and anecdotes. Commentators debate how effective sabermetrics actually is, but Bean’s original insight—that we can’t learn that much about baseball just by watching—changed the game.

In Moneyball, Michael Lewis tells the story of Billy Bean, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics who transformed the A’s using sabermetrics, the data-driven approach to understanding baseball. Bean noticed that instead of using data to predict player performance, baseball professionals relied on faulty intuitions and anecdotes. Commentators debate how effective sabermetrics actually is, but Bean’s original insight—that we can’t learn that much about baseball just by watching—changed the game.

The essential theme of Max Bazerman’s new book The Power of Noticing: What the Best Leaders See is similar. Like Bean, the best leaders don’t make decisions based only on what they can see and what they can recall. Instead, they ask for more information, question the status quo, and are aware of common biases. Becoming a “first class noticer,” as Bazerman phrases it, isn’t necessarily about noticing things-in-the-world but becoming conscious of our systematic mistakes. Here are three suggestions from The Power of Noticing.

1. Widen Your Frame

The single best thing you can do to make better decisions is to ask for more information–that is, to “widen your frame”–and to know when you’re working with incomplete information.

This strategy might sound obvious but there are countless instances of smart people who ignore it. Take, for example, the fatal crash of Space Shuttle Challenger, which broke apart 73 seconds after liftoff when an O-ring on one of the rocket boosters began leaking gas. The cause of the leak was low pre-flight temperatures (it was 18 °F the night before launch) but the relationship between the temperature and the strength of the O-rings was not initially obvious. Here’s Bazerman describing the pre-launch debate:

“Technically trained engineers and managers from Morton Thiokol and NASA discussed the question of whether it was safe to launch at a low temperature. Morton Thiokol was the subcontractor that built the shuttle’s engine for NASA … in seven of the shuttle program’s twenty-four prior launches, O-ring failures had occurred. Morton Thiokol engineers initially recommended to their superiors and NASA executives that the shuttle not be launched at low temperatures; they believed there was an association between low temperature and the magnitude of O-ring problems in the seven prior problem launches. NASA personnel reacted to the engineers’ recommendation with hostility and argued that Morton Thiokol had provided no evidence that should change their plans to launch.”

At that point, NASA should have asked for more information. In order to determine how low temperatures could be affecting the O-rings, NASA needed to examine the temperatures during the 17 successful launches. If they had, NASA would have noticed a clear pattern: O-rings didn’t necessarily fail when it was cold, but they only failed when it was cold. Here’s Bazerman:

“… looking at all of the data shows a clear connection between temperature and O-ring failure and in fact predicts that the Challenger had a greater than 99 percent chance of failure. But, like so many of us, the engineers and managers limited themselves to the data in the room and never asked themselves what data would be needed to test the temperature hypothesis.”

An easy way to remember to ask for more information is to remember this phrase: “what you see is rarely all there is.” Which brings us to the next section…

2. Remember The Dogs That Don’t Bark

Bazerman writes about Silver Blaze, a short story by Arthur Conan Doyle about how Sherlock Holmes solved a mystery by noticing something that did not happen. Holmes was investigating the murder of a horse trainer named John Starker and the disappearance of his horse, Silver Blaze. The evidence pointed toward Fitzroy Simpson, a London bookmaker who had bet against Silver Blaze in an upcoming high stakes race. Holmes ingeniously solves the case by focusing on a stable dog that didn’t bark during the evening of the murder. “The midnight visitor,” Holmes writes, “was someone the dog knew well.”

Holmes correctly reasons that Starker was living a double life. He was deeply in debt, so he drugged the stable boy and led the horse “into the hollow” where he planned to cut him with a knife and frame Simpson. However, Silver Blaze lashed out and struck Starker in the forehead–killing him instantly.

Noticing what didn’t happen in a given situation is a critical skill not only in detective work but also in business and during negotiations. And Bazerman isn’t the only one giving this advice. Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel Prize in economics for his research about how people mistakenly believe that “What You See Is All There Is.” That is, when we decide, we tend to construct the most plausible story based almost exclusively on information that’s obvious and known. We must also focus on information that is not apparent–the dog that didn’t bark.

Nate Silver makes a similar point in his best seller The Signal and the Noise. He writes about “failures of imagination,” or mistakes that result from having enough information but ignoring and overlooking the most relevant information. (September 11 and Hurricane Katrina are two dramatic examples.) How can we distinguish helpful information from the irrelevant stuff? It helps to….

3. Keep a Decision-Making Journal

Recall a crisis that surprised you or your organization. What happened? Who was responsible for what? What was the result? Now imagine that you’ve answered these questions in front of a friend. He responds, “Why didn’t anyone see it coming?”

In the last chapter of The Power of Noticing, Bazerman asks readers to think through what their answer would be. (He recommends writing answers on a piece of paper.)

Here’s the question:

Was your response something like one of the following:

No one could have predicted what happened.

The odds of it happening were so low that it didn’t seem worth of consideration.

Or did it sound something like this:

I didn’t examine what threats were confronting our organizations.

I didn’t ask others about what data were missing.

You might have noticed a difference between the two lists. The first consists of external attributions; the second of internal attributions. There is not a huge list of psychological findings that have withstood fifty years of research, but our tendency to attribute our successes to internal forces and outsource our failures to external forces is one. Most crises result from a combination of internal and external reasons. We could have done a better job anticipating and managing the crisis–but our organization was ill-prepared to begin with.

Bazerman’s point is that even if the reasons for a crisis rest with the organization, we should always focus on internal attributions.

“Even when failures occur, [first class noticers] focus on what they did and, more important, on what they could do differently in the future. As a result, they avoid repeating their mistakes. It is this focus on self-improvement that allows us to learn from experience and develop the tendencies needed to become first-class noticers.”

A helpful method to adopt an “internal locus of control” is to maintain a decision-making journal. Use it to write down the reasons for your decisions, how confident you were when you made them, and the results. It will not only help you recognize where you went wrong but also how lucky you might have been. Most importantly, decision-making journals help us remove hindsight biases that make evaluating our previous decisions so hard.

Conclusion

In Moneyball Michael Lewis explains that “The market for baseball players was so inefficient, and the general grasp of sound baseball strategy so weak, that superior management could run circles around taller piles of cash.” Bazerman wonders: “Why didn’t anyone else in baseball (or basketball or football or hockey or soccer) notice the obvious flaws in the system?”

It’s a great question because just about everyone from every industry has asked a version of it. And like baseball professionals before the sabermetric era, the problem is not a lack of intelligence but a lack of tools. The Power of Noticing provides a number of practical tools grounded by smart psychological science. The ones mentioned here are just a few.

The best part of the book is its perspective. Instead of questioning the status quo, we tend to rely on it. “To become the Billy Beane of your industry,” Bazerman concludes, “the question you should be asking yourself is this: What conventional wisdom prevails in my industry that deserves to be questioned?”

Here’s the Gist

Harvard Professor Max Bazerman’s new book is The Power of Noticing: What the Best Leaders See.

When you decide, always ask for more information.

Don’t forget errors of omission—the so-called “dog that didn’t bark.”

If you want to decide better, keep a decision making journal!

Note: This book review is by Sam McNerney.

The post 3 Ways to Make Better Decisions Using “The Power of Noticing” appeared first on Nir and Far.