Nir Eyal's Blog, page 33

October 24, 2014

Habits, Obstacles, and Media Manipulation with Ryan Holiday

This week I chat with Ryan Holiday, an author, hacker, and self-described “media manipulator.” Ryan’s new book “The Obstacle is the Way” takes an interesting look at how challenges shape and improve our lives.

We discuss the personal habits Ryan integrated into his working life to reveal how he accomplished so much in so little time. Enjoy!

October 14, 2014

A Free Course on User Behavior

I do quite a bit of research, writing, and consulting on product psychology — the deeper reasons underlying why users do what they do. I also frequently teach and speak on the topic. Invariably, after each talk, someone approaches me and asks, “That was very interesting. Now where do I learn more?”

I’m never sure what to say, since there’s so much great information available. What this person really wants to know (and I’m assuming you do, too) is where all the really good stuff is. They want to know the highlights, the takeaways, and the methods and techniques that can help them be better at their careers, build better products, and ultimately improve people’s lives.

That’s why I’m proud to announce a new online course called Product Psychology. This free course taps into the collective wisdom of some of the brightest minds in the field to help you better understand user behavior. They’ve taken the time to dig up their favorite articles, videos, and resources to get you up to speed quickly. Best of all, lessons are sent free via email.

Lessons include insights into how to understand what your users really want, how to build for emotional engagement, how to do effective user research, and many other topics. The lessons are curated by several notable psychologists, entrepreneurs, and designers including Michal Levin from Google, Matthew Pearson from Airbnb, Ryan Hoover from Product Hunt, and many others.

If you want to understand the deeper reasons why users do what they do, check out this free course.

Sign up at ProductPsychology.com.

September 18, 2014

This Simple Equation Reveals How Habits Shape Your Health, Happiness, and Wealth

Nir’s Note: This guest post is by James Clear. James writes at JamesClear.com, where he share ideas for mastering personal habits. Join his free newsletter here.

In 1936, a man named Kurt Lewin wrote a simple equation that changed the way we think about habits and human behavior.

The equation makes the following statement: Behavior is a function of the Person in their Environment. [1]

Known today as Lewin’s Equation, this tiny expression contains most of what you need to know about building good habits, breaking bad ones, and making progress in your life.

Let’s talk about what we can learn from it and how to apply these ideas to master the habits that shape your health, happiness, and wealth.

What Drives Our Behavior?

Before Lewin’s Equation became famous, most experts believed that a person’s habits and actions were a result of the type of person they were, not the environment they were in at the time.

You can still find many examples of this belief today. For instance, if you struggle to stick to a diet you might say, “I just don’t have any willpower.” Or, if you can’t seem to finish that big project like writing a book, you might say, “I’m a great starter, but a lousy finisher.” These statements imply that our habits and actions are determined by some set of characteristics that we are born with; that our habits are fixed based on who we are.

Lewin, however, said something different. He said that it is not just your personal characteristics, but also your environment that drives your behavior. Your habits are highly dependent upon context. In many cases, your environment will drive your behavior even more than your personality. So, maybe you’re struggling to stick to that diet because you’re surrounded by bad options or unhealthy people, not because you were born with too little willpower.

Let’s break down these two areas, personality and environment, and talk about how you can improve them to build good habits and break bad ones.

The Elements of Personality

We know more about our personal characteristics today than we did when Lewin was around. Perhaps most importantly, we know that your abilities are not fixed in stone. You can improve.

The key, however, is to believe you can improve. Carol Dweck, a Stanford professor, has become well-known for her work analyzing the differences between the fixed mindset and the growth mindset. When you are using a fixed mindset, you believe that your abilities in a particular area are fixed. When you are using a growth mindset, you believe that you can improve, learn, and build upon your current abilities.

While reading Dweck’s best-selling book, Mindset, I found it interesting that the same person can have a growth mindset in one area and a fixed mindset in another.

In other words, your identity and beliefs play a role in your habits and if you’re looking to create a new identity, you have to cast a vote for that identity. The best way to improve your abilities and skills is through deliberate practice.

The Elements of Environment

The second factor in Lewin’s Equation, environment, can often seem like something that happens to us rather than something we have control over. It can be difficult to change where you work, who you’re surrounded by, and where you live. That said, there are actually quite a few strategies that you can use to adjust your environment and build better habits.

First, you can do what BJ Fogg calls “designing for laziness.” Fogg wanted to reduce the amount of popcorn he ate, so he took the bag of popcorn out of his kitchen, climbed the ladder in his garage, and put the popcorn on the highest shelf. If he really wanted popcorn, he could always go to the garage, get the ladder, and climb up to get it. But his default decision when he was feeling lazy would be to make a better choice. By designing his environment for laziness, Fogg made it easier to stick with healthier habits.

Second, the physical space you live in and the arrangement of the things you come across can dramatically alter your behavior. For example, in his book Nudge, Richard Thaler talks about how grocery store products on shelves at eye level get purchased more than those down by the floor. Researchers Eric Johnson and Daniel Goldstein conducted a study that revealed dramatic differences in organ donation rates based simply on two different types of forms that were passed out. Finally, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston discovered that they could instantly increase the amount of water people drank and decrease the amount of soda they drank simply by rearranging the way drinks were displayed in the cafeteria. This concept, which is known as choice architecture, refers to your ability to structure the physical space around you to prime good choices.

Third, we have the digital environment. There are a wide range of digital triggers that prompt our behavior. As Nir Eyal describes, when Facebook notifies you of a new action, you’re prompted to log back on. When someone emails you, you are prompted to respond. These digital triggers are simple ways of building habit-forming behaviors in online products and services. In many cases, these digital triggers become distractions that take you away from the work and habits that are actually important to you. As much as possible, I prefer to combat this distraction by simplifying and eliminating everything that isn’t necessary. Another option is to use a service like Freedom to reduce procrastination and distraction.

Behavior, the Person, and the Environment

Changing your behavior and sticking to new habits can be hard. No doubt about it. Thankfully, Lewin’s Equation keeps things simple.

B = f(P,E). Behavior is a function of the Person in their Environment.

Improve yourself and adjust your environment to make good habits easier and bad habits harder. If you can do those two things, sticking with better habits will be much easier.

Sources

Lewin’s Equation was originally published in Kurt Lewin’s 1936 book, Principles of Topological Psychology.

Thanks to Nir for telling me about Lewin’s Equation, which led me down the path to this article.

Note: This guest post was written by James Clear, who writes at JamesClear.com.

September 8, 2014

It’s Not All Fun And Games: The Pros and Cons of Gamification at Work

Nir’s Note: This post is by Stuart Luman, a science, technology, and business writer who has worked at Wired Magazine, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and IBM.

MAKING WORK INTO A GAME HAS ITS CRITICS. IS THIS A PRACTICE WORTH KEEPING?

In the never-ending effort to motivate employees, companies are taking cues from video games–adding scoring, virtual badges, and other game-like elements to everyday work processes to make jobs more fun.

In the never-ending effort to motivate employees, companies are taking cues from video games–adding scoring, virtual badges, and other game-like elements to everyday work processes to make jobs more fun.

Some proponents insist that one day every job will somehow be gamified, while detractors fear it’s just another management fad or worse, a sinister new form of corporate control.

To weed through some of the hype, here are four pros and cons to gamifying the enterprise.

The Good

1. GAMIFICATION INCREASES EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT

The most often cited reason companies try gamification is to improve employee motivation. Apparently, there are a lot of workers who need the extra boost. According to a 2013 Gallup poll, 70% of U.S. workers reported themselves as not being engaged in their jobs.

Companies have found that gamification can help. LiveOps, a call center outsourcing firm, reported that adding game elements to reward employees reduced call times by 15% while increasing sales at least 8% and customer satisfaction 9%. The company also reduced training time from four weeks to only 14 hours when it added badges and rankings to motivate its workforce.

2. GAMIFICATION OFFERS IMMEDIATE SIGNS OF ACHIEVEMENT AND PROGRESS

In traditional workplaces, employees receive annual reviews that decide raises and promotions. Most of the time, however, they toil away unnoticed and unrewarded.

In the gamified workplace, employees receive constant updates on their performance as they earn higher rankings and badges that get the attention of colleagues and supervisors. Companies like Spotify and LivingSocial have already replaced traditional reviews with mobile and gamified versions and have reported that 90% of employees are voluntarily participating in the programs.

3. GAMIFICATION ALLOWS THE BEST AND BRIGHTEST TO SHINE

A vital benefit of gamifying business is that it helps companies identify their future stars and leaders. Rather than just motivating the disengaged, gamification provides tools for motivated workers to contribute and be recognized.

Unlike in the past, when managers would call attention to their best employees, workers now identify each other. NTT Data and Deloitte use gamification to provide their employees with the chance to learn about leadership roles, develop management skills, and become better known within their organizations based upon their gameplay.

4. GAMIFICATION IS A NEW TYPE OF CREDENTIAL

German enterprise software company SAP has used a point system to rank top contributors on its SAP Community Network (SCN) for a decade. Users of the social media site earn points when they contribute to forums and when their posts are liked. Rankings are visible on a global leaderboard, which is then used in employee performance reviews and when managers are searching for domain specialists when forming project teams.

Users have even begun including SCN ranking on resumes and employers are asking for them on job applications. What was intended as a purely internal metric to encourage community participation has become a valuable credential in the real world.

The Bad

1. GAMIFICATION IS OFTEN HAM-FISTED

Many companies implementing enterprise gamification do so in the most generic ways. They slap point systems, badges, and leaderboards onto any work process they can think of rather than creating thoughtful experiences that balance competition and collaboration. They overlook the importance of creating meaning and fun in employees’ lives. For these reasons and others, Gartner predicts that 80% of efforts to gamify the workplace will fail.

2. MANDATED PLAY ISN’T REALLY PLAY

Wall Street Journal technology reporter Farhad Manjoo questions any attempt to gamify work, musing that employees will rebel en masse when corporate managers try to make otherwise mundane jobs “fun.”

Furthermore, gaming evangelist and Reality Is Broken author Jane McGonigal, who has distanced herself from gamification, insists that games by their nature must be voluntary. When a company insists its employees play along, it stops being a game and is a form of coercion.

3. GAMIFICATION IS AN INVITATION TO CHEAT AND STAB COWORKERS IN THE BACK

For as long as people have played games, they’ve cheated at them, too. When people’s jobs, promotions, and raises are based on a game, the temptation to cheat or take advantage of loopholes in the system can be hard to resist. Even worse, efforts to increase internal competition could provoke employees to actively sabotage each other or make unethical choices rather than work together for the good of the company as they attempt to hit specific goals. A quick search of SAP’s Community Network reveals many allegations by users of others cheating to increase their site rankings.

4. THE NOVELTY WEARS OFF

At some point, most games get tiresome. Remember FarmVille? A challenge for enterprise gamification designers will be engineering variety and novelty into the experience to keep it novel. Workers may tire of badges, leaderboards, and challenges designed to keep them motivated in jobs that they otherwise wouldn’t want to do. Gamification might offer short-term productivity gains rather than long-term benefits.

The problem that enterprise gamification is trying to solve is real: the profound disengagement of the U.S. workforce. Yet it’s no cure-all. Even as some companies have seen positive results, deployments must first and foremost provide useful benefits to employees.

Simply adding game-like elements to every job, while neglecting the long-term welfare of the people using the software, is clearly unsustainable. However, when the common pitfalls are considered and game mechanics are carefully implemented, gamification can add fun, meaning, and motivation to the workplace.

Note: This post was written by Stuart Luman.

Photo Credit: peddhapati

August 28, 2014

Getting Traction: How to Hook New Users

Nir’s Note: Justin Mares is the co-author of the new book Traction , a startup guide to getting customers. Justin’s framework provides a simple way for new marketers to discover their most effective triggers. Get 3 chapters of Justin’s book free at tractionbook.com .

In his book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, Nir Eyal introduces the concept of triggers as they relate to building user habits. As a quick refresher, triggers are anything that cues action. For example, when you see a “Sign-up Now” button on a blog asking for your email, the trigger is effective when it prompts you to submit your email address.

In his book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, Nir Eyal introduces the concept of triggers as they relate to building user habits. As a quick refresher, triggers are anything that cues action. For example, when you see a “Sign-up Now” button on a blog asking for your email, the trigger is effective when it prompts you to submit your email address.

As we learn in Hooked, people will only take an action when they’ve been triggered by some cue. But how do you decide what triggers to use? Furthermore, once you have ideas for your triggers, how do you make them as effective as possible? What insights can we glean from user psychology to help us get more users to start using our product in the first place?

In this post, I’m going to cover how you can use external triggers to get traction: how to use cues in a user’s environment to engage current customers and acquire new ones. By the end of this post, you will have a list of triggers you can immediately implement to get more traction and ultimately make your product more engaging.

Types of Triggers

First, let’s review the different kinds of triggers. Nir mentions four kinds of external triggers in his book:

Paid triggers. These triggers include advertising, search engine marketing, and other paid channels that attract user’s attention and get them to check out a product or service.

Earned triggers. These are triggers that you can’t buy directly, but that still generate short-term exposure. Things like press, viral videos, App Store rankings and speaking gigs are all earned opportunities to get wider exposure. Though they can be very effective, these kinds of triggers are also harder to consistently replicate.

Relationship triggers. These triggers are generated by referrals from people you have a relationship with. Think of tweets you see from friends playing the Kardashian game, things that Facebook connections “Like”, or hearing about products from word of mouth. All are triggers that leverage existing relationships to reach new users, and can be extremely powerful.

Owned triggers. Lastly, these are triggers that are a part of your user’s environment by their choice: the app icon on a user’s phone, an email newsletter the user subscribers to, or push notifications the user has opted in to.

Owned triggers help drive repeat engagement until a habit is formed. The other trigger types help you acquire new users. For the purposes of this post, I’ll focus on the first three types of triggers, those that help acquire new users by driving first-time use.

The Bullseye Framework

The first step to growth is determining what triggers might work to acquire new users and where you want to deploy those triggers. In our research, we found there are 19 ways companies acquire customers.

With so many triggers at your disposal, figuring out which one to focus on can be tough. That’s why we use a simple tool we call the “Bullseye Framework” to help you find the most suitable triggers to drive use of your product.

Step 1: Brainstorm

The goal in brainstorming is to come up with reasonable ways you might trigger users. If you were to advertise offline, where would be the best place to do it? If you were to give a speech, who would be the ideal audience?

In terms of research to feed your brainstorm, you should know what marketing strategies have worked in your industry, as well as the history of successful marketing campaigns in your space. It’s especially important to understand how other companies acquired customers over time, and how unsuccessful companies wasted their marketing dollars. I’d suggest talking to advisors and other founders in your industry to learn what’s worked for others, and what hasn’t. You can also use tools like SEMrush and KeywordSpy to see the paid triggers others are using, and sites like Compete to see where most of their traffic is coming from. What triggers have historically worked in reaching your audience – ads, viral relationship triggers, or earned triggers like PR and email marketing? What triggers have failed?

Step 2: Rank

The ranking step helps you organize your brainstorming efforts. It also helps you to think critically about your potential triggers.

Place each of the triggers into one of three columns, with each column representing a concentric circle in the Bullseye:

Column A (Inner Circle): which triggers seem most promising right now?

Column B (Potential): which triggers seem like they could possibly work?

Column C (Longshot): which seem like worth exploring but only after the low-hanging fruit has been picked?

Your research in the brainstorm step should guide your rankings. Ranking is more gut feel than a science. Usually, a few ideas you thought of will seem particularly compelling – these belong in column A. Triggers that seem less plausible but still worth exploring go in column B. The stretch ideas, that are less practical and promising belong in column C.

How you rank these triggers will depend on your stage as a company, funding and willingness to experiment. Some paid triggers – ads and the like – could be effective, but are too expensive to test in the very early stages of a company. Others (like offline ads) may not make sense given the audience you’re trying to reach.

Step 3: Prioritize

In this step, we’ll identify your inner circle: the three triggers that seem most promising. You should have more than one trigger in your inner circle so you don’t waste valuable time finding your successful trigger by testing them one by one. Instead, you’ll need to run multiple experiments at the same time.

Many of the tests you’ll be running (AdWords vs. content marketing) can be done simultaneously, and may take some time to run after they’ve been set up. This is why running tests in parallel is so important: it helps you figure out what’s working (and what’s not) much faster.

Step 4: Test

The testing step is where you put your ideas into the real world. The goal of this step is to find out which of the triggers in your inner circle are worth focusing-on and which you should dump.

You will make that decision based on results from a series of relatively cheap tests. These tests should be designed to answer the following questions.

Roughly how much will it cost to acquire customers with this trigger?

How many customers are available with this trigger?

Are the customers that respond to this trigger the ones you want right now?

Keep in mind that when testing, you are not trying to get a lot of traction just yet. Instead, you are simply trying to determine what triggers work for you.

Step 5: Focusing

If all goes well, at least one of the triggers you tested in your inner circle produced promising results. In that case, you should start directing your traction efforts and resources towards that most promising one.

The goal of this focusing step is quite simple: to wring every bit of traction out of the trigger. To do so, you will need to continually experiment to optimize your current trigger by testing things like ad copy, demographic targets, and other attributes.

The 5-step bullseye framework helps companies systematically determine which channels make sense to invest their time and effort into. What triggers have worked for you? Let me know in the comments!

Note: This guest post was written by Justin Mares. Get 3 chapters of his Traction book free at http://tractionbook.com .

Photo Credit: emiliokuffer

August 23, 2014

Designing for Behavior Change Book Review

Nir’s Note: This guest post comes from Marc Abraham, a London-based product manager. In this article, Marc reviews the recently published book Designing for Behavior Change by Stephan Wendel. Follow Marc on Twitter.

Behavioral economics, psychology and persuasive technology have proven to be very popular topics over the past decade. These subjects all have one aspect in common; they help us understand how people make decisions in their daily lives, and how those decisions are shaped by people’s prior experiences and their environment. A question then arises around what it means to change people’s behaviors and how one can design to achieve such change.

Behavioral economics, psychology and persuasive technology have proven to be very popular topics over the past decade. These subjects all have one aspect in common; they help us understand how people make decisions in their daily lives, and how those decisions are shaped by people’s prior experiences and their environment. A question then arises around what it means to change people’s behaviors and how one can design to achieve such change.

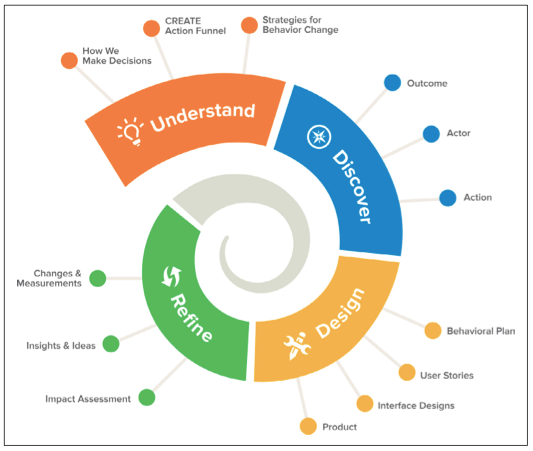

Stephen Wendel, a Principal Scientist at HelloWallet, has written Designing for Behavior Change, which studies how one can apply psychology and behavioral economics to product design. In this book, Wendel introduces four stages of designing for behavior change: Understand, Discover, Design and Refine (see Fig. 1 below):

Understand – The process starts off with gaining an understanding of how people make decisions and how our cognitive mechanisms can support (or hinder) behavior change.

Discover - The second stage is about a company working out what it wants to accomplish with the product, and for whom.

Design – The actual design stage can be broken down into two subtasks: (1) designing the overall concept for the product and (2) designing the specific user interface.

Refine – Analyzing data to generate insights and ideas for ongoing improvement of the product.

Fig. 1 – Stages and outputs per stage of the designing for behavior change – Taken from: “Designing for Behavior Change” by Stephen Wendel

Stage 1 – Understand

This stage is all about understanding how people make decisions and how the mind decides what to do next. There is a clear distinction between the deliberative and the intuitive mind. Our deliberative or “conscious” mind tends tends to be slow, focused and self-aware. In contrast, when people are in an intuitive or “emotional” mode they are likely to act on “gut feeling”, fast and unaware. Most of the time, we are not consciously deciding what to do next. Instead, we often act based on habits. Even when we do think consciously about what to do next, we actively try to avoid hard work.

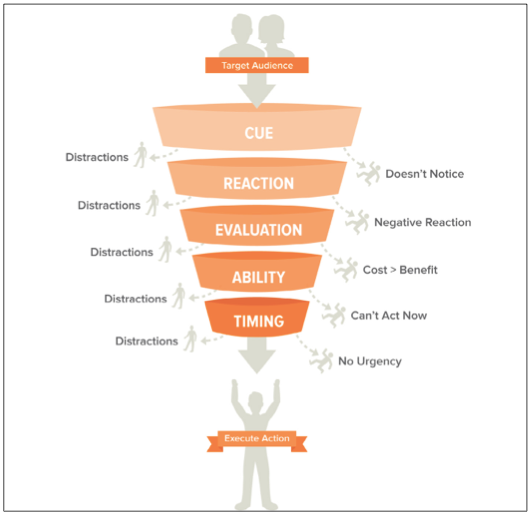

Designing for Behavior Change stresses the importance of being very clear about the type of behavior one is trying to encourage: a conscious choice or an intuitive response. Wendel proposes a simple but powerful model – “Create” – which helps to understand what products need to do to get users to take a particular action:

Cue – A cue for users to think about what to do can either be internal or external. External cues happen when there is something in our environment triggering us to think about a certain action. Internal cues are the result of our minds thinking about the action on its own, through some unknown web of associated ideas.

Reaction – Once the mind has been cued to think about a potential action, there is an automatic reaction in response. This reaction tends to be intuitive and automatic.

Evaluation – After an initial intuitive response, there might be room for a more conscious evaluation of the action and of potential alternatives. This happens especially when we are facing novel situations, and we do not have an automatic behavior to trigger.

Ability -

Assuming the choice has been made to act, the question arises whether it is actually feasible to undertake the action. Wendel suggests that the individual must be able to act immediately and without obstacles.

Timing - When should you take the action? The decision when to take action can be taken based on a sense of urgency, and by other, less forceful factors.

These five mental events can be best summarized through the “Create Action Funnel” (see Fig. 2 below). The main point to make with respect to this funnel, is that people can drop out out at each stage. A person will most probably only continue through the funnel if the action is more effective or better than the alternatives.

Fig. 2 – The Create Action Funnel – Taken from: “Designing for Behavior Change” by Stephen Wendel, p. 40

“Strategies for Behavior Change” is the third and final output of the Understand stage. The book suggests three possible strategies to consider:

Cheat - If what you really care about is the action getting done, and it is possible to all but eliminate the work required of the user beyond giving consent, then do it.

Make or change habits - If the user needs to take an action multiple times, and you can identify a clear cue, routine, and reward, then use the “habits” strategy (see Fig. 3 below).

Support conscious action – If neither of the two aforementioned strategies is available, then you must help the user consciously undertake the target action.

Stage 2 – Discover

The second stage of Wendel’s designing for behavior change process is the Discover stage. The main goal is of this stage is to figure out what it is that one wants to accomplish with the product. Wendel identifies five distinct steps with regard to discovery:

Clarify the overall behavioral vision of the product.

Identify the user outcomes sought.

Generate a list of possible actions.

Get to know your users and what is feasible and interesting for them.

Evaluate the list of possible actions and select the best one.

When thinking about “target outcomes,” you can think about what both the company and the user aim to accomplish with the product. You can then clarify this outcome by asking yourself some of the following probing questions:

Which type? – Does the product ultimately seek to change something about the environment or about people?

Where? – What is the geographic scope of the impact?

What? – What is the actual change to the environment or person?

When? – At what point should the product have an impact?

Within the Discover process, a lot of emphasis is placed on finding the “Minimum Viable Action.” This is the shortest, simplest version of the target action that users must take so that you can test whether your product idea (and its assumed impact on behavior) works.

At the end of the Discover stage, you should have detailed observations about your users, a set of user personas, and a clear statement of the target outcome, actor and action.

Stage 3 – Design

Wendel then explores the Design stage. The purpose of this stage is to create a context that drives action. There are three key aspects to this process:

Structure the action – To ensure that an action is feasible and inviting for the user. Creating a “behavioral plan” can be a good way to outline the different steps users should take from what they are doing now to using the product and completing the target action. This can be a simple flowchart or a written narrative; the key objective here is to think about the sequence of real world steps a user needs to take to complete an action.

Design the environment – To ensure that the environment is constructed in such a way that it supports the action. When talking about “environment,” Wendel means two things. Firstly, the product itself. For example, a web page or smartphone where a user takes an action. Secondly, the user’s local environment, which can be both physical and social. Wendel then goes on to identify a number of ways in which products can construct an environment, e.g. by increasing the motivation for people to act or by generating a feedback loop.

Prepare the user – How does one prepare the user to take action? Wendel suggests three tactics which can help to prepare the user to take action, now or in the future: “narrate” (change how users see themselves), “associate” (change how users see the action) and “educate” (change how users see the world).

Stage 4 – Refine

Refine is the fourth stage of the behavior change process. This stage is all about learning about how people actually use the product, its behavioral impact and identifying areas for improvement. There are three main components of this stage:

Impact Assessment – Measure the impact of the product, based on clear target outcomes and well defined metrics for each outcome. Here it is important to set clear thresholds for success and failure.

Identifying obstacles to behavior change – Discover problems, develop potential solutions and generate additional ideas for how to make the product better. One can start this process by watching real people using the product (direct observation) and by gathering usage data. We can thus start getting a better insight into how people use the product, what the bottlenecks are, where the product is having the most impact on people, etc.

Learning and refining the product – Determine what changes to implement through (1) gathering lessons learned and potential product improvements (2) prioritizing potential improvements based on business considerations and behavioral impact and (3) integrating potential improvements into the appropriate part of the product development process.

Designing for Behavior Change offers insight into how to build products and experiences to impact human actions. Not the easiest of topics, Wendel provides clear frameworks for constructing products and experiences to improve the lives of our users.

NOTE: This guest post is by Marc Abraham

August 11, 2014

The Sneaky Trick Behind the Explosive Growth of the Kardashian Game

Recently, I started looking into the explosively popular new game Kim Kardashian: Hollywood. The game has ranked at or near the top of Apple’s U.S. App Store charts for the most downloaded free game. Industry watchers say the app could gross $200 million annually and net Kardashian a sizable chunk of the game’s profits.

My line of work is researching what makes some products so compelling and in the case of the Kardashian game, I wanted to know what was behind the app’s phenomenal growth.

I soon discovered that one potential driver of all of its installs is a rather sneaky tactic that exploits user error and can unwittingly post messages to players’ Twitter accounts.

It’s called the “viral oops.”

Unlike viral loops, which are actions users take in the normal course of using a product to invite new members, viral oops rely on the user ‘effing-up.

A classic example of a viral loop can be found in a product like Paypal. If one user wants to send cash to another, the receiver generally opens a Paypal account to redeem the funds. Conceivably, when the new user wants to send money themselves, they’ll usher-in more new members and the loop continues.

However, in the case of a viral oops, the user doesn’t realize what they’ve just done. A viral oops isn’t necessarily a deception by the company — in the way sending messages without the user’s permission might be — rather, it is more of a digital sleight of hand. Like a magic trick, when retracing the steps to figure out what just happened, it’s obvious how the viral oops occurred and the user most often blames themselves rather than the company for allowing the misstep.

In the case of Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, the game begins innocently enough. The app is a classic role-playing game where players take the part of an up and coming Hollywood celebrity determined to climb the ranks up to “A-List” status. To get there, players must pass through lower levels of stardom on the E, D, C, and B-Lists. Moving through these levels requires completing tasks like posing for magazines, going on dates, and as best as I can tell, shoplifting for Kim Kardashian.

My avatar shoplifting for Kim Kardashian’s avatar

Finishing a task requires repetitive thumb tapping that uses-up energy points. Energy is replenished by waiting for a period of time or by paying real dollars to get back into the game. This is how the millions are made, but that’s not the sneaky part.

Here’s how the viral oops works: The game features a “feed update,” which pops-up occasionally to provide news and gossip like a Twitter account. Fictitious characters in the game like Paris Hilton lookalike @WillowPape update their feeds with hashtag-filled 140-character bursts — just like on Twitter. A constant count of “fans” hovers on screen, further giving the impression that the game has it’s own version of Twitter.

When the game asked me to follow a news reporter named Ray Powers by his handle @StarNews_Ray, doing so felt like part of game play. Naturally, I assumed that the Twitter in the game isn’t the real-world Twitter. How could it be?

In the screen shot below my avatar reads tweets between @WillowPape and @StarNews_Ray, both fictitious characters in the game, right? Not exactly.

Can you tell the difference?

Unbeknownst to me, when I followed @StarNews_Ray in the game, my real world Twitter account also began following @StarNews_Ray and apparently I’m not the only one. The real-world Twitter account of fake @StarNews_Ray has racked-up over 400,000 followers.

Now the trap was set for the viral oops. During my first session of play, the app offered points for sharing news on (what I assumed was) in-game Twitter. However, what I thought was fake Twitter turned out to be real Twitter and the tweet was sent to thousands of my followers’ streams.

The game automatically posted, “I’m now an E-list celebrity in Kim Kardashian: Hollywood. Come join me and become famous too by playing on iPhone!” and included a link to download the app.

A search on Twitter revealed multiple similar tweets posted every minute. It is unclear how many of these tweets were sent by people unaware of what was happening but in the month of July over 396,000 similar auto-populated tweets were sent. One of those tweets which was certainly not intentional was from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Water, which quickly deleting the post after realizing the error.

The EPA’s “oops”

It appears all these mistakes were no accident. However, according to Glu Mobile’s CEO, Niccolo de Masi, cases of people mistakenly tweeting from the game are rare. “There is always .0001% of people who get confused,” de Masi told me. “When you have this many people installing the game,” de Masi said during our call, “you’re going to have a lot of people playing that haven’t played games before. It’s a symptom of tremendous success and popular appeal.”

Perhaps as de Masi argues, the people making this mistake are tech novices. However, even Sarah Buhr, a reporter for TechCrunch and conceivably one of the most tech-literate people around made the very same error, admitting, “What the game neglected to tell me is that it would tweet out to all my followers in real life that I, a grown woman, was playing Kim Kardashian Hollywood.”

De Masi was quick to point out that, “this is the best reviewed game in the app store” and that the company has not heard significant complaints from players. He credited Kardashian’s celebrity and massive social media following for the game’s popularity.

Glu Mobile insists there is no intent to deceive but De Masi would not comment on what percentage of installs came from Twitter. De Masi believes the game is growing through word of mouth — people just want to tell others about it.

Regardless of whether the tactic is something the company is doing consciously or not, it appears to be benefiting from all the tweeting. De Masi said, “Glu as a company doesn’t spend as much money as competitors [on user acquisition] … We spend 15% whereas our competitors spend 40%.” As is often the case with the viral oops, I wasn’t sure if even the game maker wasn’t fooled into thinking all that tweeting was authentic.

When I asked De Masi whether the company had any plans to change the game, his response was that the problem was “not an issue” and “not on our radar as far something that has been a concern to millions of fans.”

Clearly, the 2.8 billion minutes players have spent in the game is a testament to its appeal. However, how much of the game’s growth is a result of real player endorsements versus a technological sleight of hand called the viral oops, is still an open question.

August 4, 2014

The Sweet Spot: Where Technology Meets the Motivational Brain

Nir’s Note: This guest post is by Dr. Marc Lewis, who studies the psychology and neuroscience of addiction. After years of active research, Marc now talks, writes, and blogs about the science and experience of addiction and how people outgrow it. Visit his website here.

You’ve just obliterated the last seven or eight zombies. It was a narrow escape and you’re flushed with satisfaction. But you didn’t see that horrendous creep, weaping sores and oozing pus, because he was hidden behind the dustbin in the shadow of a bombed out building. You get slimed, you’re dead. Or worse than dead. So you touch the “play again” bar at the bottom of the screen. Now you start further ahead than last time. You know you’re going to meet the slime-master again. Soon. Be prepared.

You’ve just obliterated the last seven or eight zombies. It was a narrow escape and you’re flushed with satisfaction. But you didn’t see that horrendous creep, weaping sores and oozing pus, because he was hidden behind the dustbin in the shadow of a bombed out building. You get slimed, you’re dead. Or worse than dead. So you touch the “play again” bar at the bottom of the screen. Now you start further ahead than last time. You know you’re going to meet the slime-master again. Soon. Be prepared.

Or you’ve crossed the desert and scaled the abandoned fortress, nearly to the top, moving along pathways that require hair-trigger adjustments with your joy-stick. But the wind is getting stronger by the second. It keeps pushing you back along the path, dangerously close to the edge. You make a daring dash between gusts. But you miscalculated, and the force of the wind blows you right off the edge. Down you plummet, to a plateau you crossed minutes ago. Now you have to make that climb again. But do it better. Get it right.

The enormous appeal of video games can be captured by a single phrase — a phrase I’ve heard bandied about by game designers, psychologists, and other professionals who need to know how video games work. It’s the sweet spot. The sweet spot is the unique space that games take you to, and keep you in, where you’re winning enough “rewards” (points, pineapples, distance traveled, or zombies killed) to feel good. But also losing enough to keep trying — hard — because you really want to go all the way.

If video games just let you win, win, win, they would get boring pretty quickly, and you’d stop playing. But if you kept losing repeatedly, the disappointment and frustration would get you to quit just as soon. The genius of game designers consists, partly, of recognizing this fundamental duality in human nature and capitalizing on it creatively. The sweet spot — where satisfaction and motivation are perfectly balanced — is what makes video games irresistible.

I study the neuroscience of addiction. I write books about addiction. And in those books I try to wrap the scientific picture inside rich, real-life narratives — the experience of addiction, the thrill, the loss, and the compulsion to do it again. My first book was about my own addiction to drugs, which bit a large chunk out of my twenties. And my nearly-finished next book uses the biographies of other addicts, ex, recovering, or still working on it. In the process of writing it, I’ve talked to a lot of addicts. And I continue to be amazed by the parallels among addictions to very different things: heroin, methamphetamine, coke, alcohol, cigarettes; and the behavioral addictions: gambling, sex, porn, food, and — of course — gaming.

The brain changes that take place with addiction are also remarkably similar, regardless of what you’re addicted to. At a recent conference I gazed at fMRI (brain scan) images that showed excessive activation in exactly the same spot — the nucleus accumbens (or ventral striatum, a structure inside the cortex, behind the eyeballs) — for addicts anticipating their next hit, whether of potato chips, heroin, or roulette. The nucleus accumbens also glows with activation in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and that’s revealing. The compulsive nature of addiction, the feeling that you just can’t stop, makes it look like a spinoff of OCD, a long-recognized psychiatric disorder. So what’s that all about?

Our brains compute three things about reward: how much will we get, how soon will we get it, and how certain are we that we will in fact get it? All that computation goes on in the nucleus accumbens and its neural neighbors. The fuel that activates the nucleus accumbens is dopamine. The bigger and more immediate the expected reward, the more dopamine gets sucked up (from the midbrain) into the nucleus accumbens. And the more charged we feel as a result: wanting, reaching, straining toward that all-consuming goal — whatever it is. But here’s the catch. You might think that the more probable the reward, the more dopamine gets released as well. Wrong! (You just lost a life.) It’s actually when the probability of reward hovers at around 50% that dopamine flow is maximal. When the probability of getting it is as high as the probability of not getting it — the point of maximum uncertainty. That’s what turns us on the most.

In that sense, the sweet spot is the perfect technological reflection of the brain’s fundamental formula for achievement motivation. We try hardest (and are most thrilled and enticed) when the game is hard enough but not too hard.

But why are video games so addictive? Start with the notion that most addictive drugs, and most addictive activities, are products of technology. Heroin comes from opium, but it passes through a lot of chemical manipulations first. Booze comes from distilleries and breweries. Porn comes from cameras. Gambling requires, at the very least, a deck of cards or a pair of dice, and the rows of slot machines in Vegas or Tokyo? — simply technological upgrades. Technology finds ways to make things more efficient or more effective. Technology evolves as an outcropping of human (cultural) evolution, serving its needs and desires with ever more refined versions of what we want.

Video games are really just another step in the evolution of games, and games are enticing because you might win but you might not. Games have been around for millenia. But video games do it so well — so efficiently — because they ride the tide of computer technology. The balance between winning and losing is continuously adjusted, according to how well you’re doing, as measured in hits and misses, gains and losses, moment by moment. If you lose too much the game gets easier. If you win too much it gets harder. Incrementally. That’s how it’s programmed. You hardly notice this insidious trick because you are so drawn in, so absorbed by it. And you are so absorbed because you are in the sweet spot. The sweet spot knows you, it finds you. It adjusts to you.

In fact the sweet spot adjusts to what’s going on in your nucleus accumbens, the flow of dopamine molecules in and out of that intimate structure. As with heroin, meth, whisky, and porn, technology serves the workings of the motivational brain. We desire winning, getting, achieving — but not constantly. Even drug addicts get utterly bored when they have unlimited supplies of whatever it is. The hunt is more thrilling than the act itself. The momentous feeling of moving forward, from the present to the immediate future — the next scene, the next screen, the next belt, hit, shot, snort, or rush — is really what we’re after. And the sweet spot keeps us going for it.

As a last word, I want to emphasize that “attractive” and “addictive” don’t equal “evil”. The surging wave of video game development keeps finding new ways to help people. Rocket Math uses the sweet spot to launch children through math instruction. SIMS games help kids understand the mechanics of evolution. As a psychologist, I’m particularly drawn to the power of video games for improving the lives of people with personal problems. Some games are geared to the learning deficits of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). And a new generation of games is aimed at those suffering from depression or anxiety disorders, enticing users through well-paced challenges and then rewarding them with skills that pay off in the real world. Mindlight draws children with anxiety disorders through real fears — the ones they go to bed with at night — and then rewards them with skills for relaxing, refocusing, and persevering — skills that allow them to enter the schoolyard with more confidence the next day.

Mechanisms of motivation churn away at the center of the brain. And, as with other elemental forces, the manipulation of those mechanisms can serve to help rather than hurt people. The sweet spot does not have to be the brain’s velvet prison. It can also be its wellspring of growth.

NOTE: This guest essay was written by Marc Lewis.

Image Credit: Skakerman

July 31, 2014

The Number One Reason Good Habits Don’t Last

Nir’s Note: This guest post is written by Max Ogles. Max writes at MaxOgles.com about behavior change, psychology, and technology. Sign up for a free copy of his upcoming e-book, “9 Ways to Motivate Yourself Using Psychology and Technology.”

A commonly quoted and incredibly scary stat reveals that 9 out of 10 people who undergo heart bypass surgeries as a result of poor health are unable to change their habits, even with their lives on the line.

A commonly quoted and incredibly scary stat reveals that 9 out of 10 people who undergo heart bypass surgeries as a result of poor health are unable to change their habits, even with their lives on the line.

We’ve all failed at something, though luckily most of us don’t face death as a consequence. Here’s a short list of some of the habits I started, only to eventually fail:

For two months, I went running 3 to 4 times each week. (I even ran a half marathon!) Then I quit running and didn’t run again for over a year.

I decided to improve my reading speed and comprehension. I read every day, practicing with a course called Breakthrough Rapid Reading. I quit after the first month.

I finally created a habit of waking up early. For three months, I woke up at 5:30 AM every day. Sleep debt and laziness caught up with me–now it’s hard to get up before 7:30.

Thankfully, these failures didn’t have any significant consequences attached to them. My life would be slightly better if I had kept them up, but even without them I can be pretty happy and content.

But the thing that bothers me is that each time I felt that these were habits, firmly in place; I had done them consistently for fairly long periods of time before I failed. I had mastered self control, exercised willpower, and shaped my life with these new productive routines, but each time the final outcome was a miserable regression back to the status quo.

The #1 Reason

So what the heck happened?! The reason these habits failed for me, and the number one reason people give up on good habits generally is that they just aren’t enjoyable.

It’s a simple truth: you are less likely to continue doing something that you do not enjoy. Here’s some proof.

Earlier this year, researchers completed a simple study about work “burnout.” First, they asked 154 undergrads to complete a series of word puzzles. Depending on your personality, “word puzzles” might sound like the 10th circle of hell, or maybe it works you up into a giddy, border-line embarrassing excitement. The researchers accounted for this by asking students, “How enjoyable do you think this task will be?” then they set them to work on the puzzles.

The results were impressive: the students who enjoyed working on puzzles performed the best when solving them. To make things even more interesting, researchers asked students to complete a simple task after working on the puzzles. The students had to squeeze a “grip exerciser,” the spring-loaded contraption used to strengthen your hand. Researchers then proved that the students who enjoyed completing the puzzles were also less fatigued, and were able to squeeze the grip for a longer period of time.

Regarding the experiment, researcher Paul O’Keefe said, “Engaging in personally interesting activities not only improves performance, but also creates an energized experience that allows people to persist when persisting would otherwise cause them to burn out.”

(This research has some limitations, namely that it was for a short term assignment rather than habit formation over time. I did find two other research studies that confirm a direct correlation between enjoyment and adherence to a habit. Find them here and here.)

That Makes Sense, But So What?

If you enjoy doing something, naturally you’ll be more likely to do it. This is practically common sense. But let’s say I’m trying to create a new habit, like running daily, and it’s really not something that I innately enjoy. How will I get myself to run every morning? I’ll convince myself that it doesn’t matter if I enjoy it, because I have the willpower to achieve anything (cue superhero music). I’ll gut it out, forcing myself to run with the “no pain, no gain” mantra, enduring agony as I run each day. And that’s a mistake.

In a another study, this one at Northwestern University, researchers administered a “willpower test” to a group of heavy smokers. In reality, it wasn’t a willpower test at all, just mindless word associations in a quiz, but at the end the participants received a score indicating that they had either high or low “impulse control.” In other words, after taking this meaningless test, some of the smokers were told that they had high willpower and others were told that they had low willpower.

In the second part of the experiment, all of the smokers watched the movie Coffee and Cigarettes, and they were offered rewards to refrain from smoking. In this scenario, researchers found that the group that believed they had “high impulse control” was actually more likely to give in to the temptation of smoking!

Remember, neither group actually had higher willpower–random assignment made it so that the groups were relatively the same. But one group thought that they had higher willpower, and that led to them overestimating their abilities. As soon as we begin to rely too much on willpower and overestimate our self control, that’s when we’re most vulnerable to fail.

Convert to Enjoyable

The same pattern held true for each of my failed behaviors. For example, I worked for months to adjust to waking up early, always forcing myself out of bed even though I hated it. I reached the point where I thought I had mastered it, and that’s the point when I failed.

Eventually I read an article from accomplished personal development blogger Steve Pavlina, entitled, “How to Wake Up Feeling Totally Alert.” Steve’s premise is that if you feel terrible when you wake up and have to work extra hard to get out of bed in the morning, you’re doing it wrong. Waking up early should be something that you enjoy and look forward to. If you teach yourself to enjoy the habit, you won’t even need to rely on willpower because you’ll be excited to do it.

The more I thought about my failed habits, the more I realized that I really didn’t enjoy any of them; I did them to be productive and often felt good afterwards, but initiating the process was always painful. As I diagnosed my failed habits, I came up with this matrix:

During the months that I woke up early, I had the habit of waking up, but didn’t enjoy it; every day was painful. I was stuck in the top left quadrant of the Habit Success Matrix, which made the behavior “difficult to maintain.” If I had found a way to make it enjoyable, I could have moved to the sweet spot, the top right quadrant, and the behaevior would have been easy to maintain.

During the months that I woke up early, I had the habit of waking up, but didn’t enjoy it; every day was painful. I was stuck in the top left quadrant of the Habit Success Matrix, which made the behavior “difficult to maintain.” If I had found a way to make it enjoyable, I could have moved to the sweet spot, the top right quadrant, and the behaevior would have been easy to maintain.

Instead, my willpower and desire slowly drained until I eventually gave up.

The moral of this story? Focus on making new behaviors enjoyable. If you’re trying to start a new behavior and you find it enjoyable, it will be easy to change and make it a habit.

How Do You Make Things Enjoyable?

Full length books can be devoted to answering this question, “How do you make behaviors enjoyable?” so I won’t promise a solution here. Instead, I’ll stick with one simple idea that I’ve seen over and over in different forms. Nir has written about this principle–he calls it a “Minimum Enjoyable Action,” MEA for short. It’s a tried and true principle of behavior change: when you start a new habit, stick to the absolute simplest action possible. The idea is that if you start with an incredibly simple action, you can slowly add on to it to create behavior change.

In the words of habit blogger Leo Babauta, “Make it so easy you can’t say no.” Much of the pain and agony we experience as we try to engage new habits comes from self imposed expectations. We tell ourselves, “I have to go to the gym every day or I’m a failure,” or “If I eat one dessert, my entire fitness plan is ruined.”

By focusing on the simplest possible action, we guarantee our success and make it much easier to progress over time. Trying to eat healthy? Start by eating one piece of lettuce. Just one. Do that every day for a week, until you feel ready to work yourself up to another piece of lettuce. Your body and mind have time to adjust, and it will be much easier to learn to enjoy your new habits instead of forcing yourself into something you simply can’t enjoy.

This guest post was authored by Max Ogles.

Image credit: zeevveez

July 22, 2014

How Successful Companies Design for Users’ Multi-Device Lives

Nir’s Note: This guest post comes from Marc Abraham, a London-based product manager at Beamly. In this article, Marc reviews the recently published book “Designing Multi-Device Experiences” by Michal Levin. Follow Marc on Twitter or check out his blog.

We live in a world where the number of connected devices is growing on a daily basis at an immense rate, with people constantly switching between these devices (PCs, smartphones, tablets, TVs and more). The question arises how we can design optimally for a device to be used together with other devices.

We live in a world where the number of connected devices is growing on a daily basis at an immense rate, with people constantly switching between these devices (PCs, smartphones, tablets, TVs and more). The question arises how we can design optimally for a device to be used together with other devices.

Michal Levin, a Senior User Experience Designer at Google, has created a framework which aims to capture the interconnections between different devices. Levin calls this framework an “ecosystem of multi-connected devices.’ The underlying goal behind this framework is to enable designers and product creators to “understand the different relationships between connected devices, as well as how individuals relate to them.” As a result, companies can create natural and fluid multi-device experiences for their users. Levin has written about the fundamentals of this ecosystem in her book Designing Multi-Device Experiences.

How does one build such an ecosystem of connected devices? What does a “multi-device experience” entail? A key ingredient is Levin’s “3Cs Framework”. The 3Cs are “Consistent”, “Continuous” and “Complementary” design approaches:

The Consistent Design Approach – Consistent design happens when the same experience and content offering is ported across devices. Despite the inherent degree of consistency between devices, adjustments will nevertheless still need to be made to adjust to different devices’ characteristics. Elements such as content offering and navigation can remain consistent across all devices whilst functional and visual optimisations can be made per individual device.

For example, Trulia – an online real estate mobile app for home buyers, sellers, renters, and real estate professionals – offers the following core elements as part of a consistent experience across all devices:

Content offering – The entire set of Trulia’s property listings is available on all devices.

Search bar – The search bar is consistently placed at the top of the app, irrespective of the device.

Property details box – This is offered across all devices, and provides more details about the property in focus.

Fig. 1 – Screenshot of Trulia’s mobile app

Trulia has optimised a number of things per individual device type. For example, in the smartphone — which has the smallest display out of all devices — the Trulia app focuses on the product’s essence only: a map view of available properties with a price distribution layer. Everything else is displayed upon interaction (see image to the right).

The Continuous design approach – With the continuous design approach, the multi-device experience flows from one device to the next. Michal Levin describes this approach as “a user flow that runs along a set of contexts, during which devices “pass the baton” to one another until the user reaches her information goal or completes the desired activity”. There are two ways in which this continuous user flow can be broken down: a single activity flow and a sequenced activity flow.

With a single activity flow, activities such as reading a book or writing a document can be carried out throughout different contexts (e.g. at work, in bed or at an airport). The end goal remains unchanged; finish reading a book or writing a document. A good example of a single activity flow is the Amazon Kindle. The Amazon Kindle Ecosystem (see Fig. 2 below) enables users to have a seamless reading experience across multiple Kindle devices and Kindle apps.

Fig. 2 – Sample Amazon Kindle’s Ecosystem

In the sequenced activities flow, the user typically goes through a number of different activities to complete her end goal. These steps can be done in different locations, at different times and with different devices being available and/or most convenient for each activity. The fact that each step can be of a very specific nature or have a different duration, has an impact on the way we design for this continuous experience. A good example is Eventbrite, a product focused on organising and attending events. With Eventbrite, the typical user workflow consists of multiple steps and tasks:

Register for an event – The user typically gets an event invite over email or through browsing. Typically, for the user to decide on registering for the event, she will want to read the event details (e.g. timings, location, etc.) after which she can complete the sign-up form.

Attend the event – The user workflow related to attending an event tends to comprise a number of subtasks such as getting to the event and checking in at the event venue. Eventbrite’s mobile app accommodates for these tasks through features such as providing directions to the venue and offering a scannable barcode for a quick check in.

The Complementary design approach involves collaboration among multiple devices operating together as a connected group. Whereas the consistent and continuous design approaches center around a single device, the complementary approach is all about user interaction with at least two devices — usually simultaneously — at any given moment. There are two types of device relationships that can help achieve a complementary approach: collaboration and control.

Collaboration – Different devices, each with its own distinct role, work together collaboratively to construct the whole user experience.

Control – The user’s primary experience takes place with a particular device, while other devices control aspects of that experience, usually remotely.

Fig. 3 – Sample Real Racing 2 Multiplayer

Additionally, devices can play different roles in the complementary experience. Devices can either be an integral part of the experience (‘must have’) or can be added to deepen the user’s experience (‘nice to have’). The book mentions the racing video game Real Racing 2 as an example of ‘must have collaboration’ between devices (see Fig. 3). Players of this game can use their smartphones to play the game on a tablet in front of them. Xbox Smartglass is an example of a product where collaboration and control meet (see Fig. 4 below). A smartphone or tablet can transform into a second-screen companion to the Xbox Smartglass by automatically serving up extended-experience TV shows, movies, music, sports and games (nice to have ‘collaboration’). On the other hand, the smartphone, tablet, and PC can all control the living room Xbox experience (must have ‘control’).

The remainder of Designing Multi-Device Experiences explores how to best measure the multi-device experience, tracking usage across all devices and understanding how users navigate through the product flow. The book ends with a chapter on potential challenges with respect to creating a multi-device ecosystem, identifying both challenges and potential ways to address them.

Michal Levin has written a very insightful and practical book, which should provide a lot of food for thought for anyone involved in designing or building a user flow which involves multiple devices.

Note: This guest post comes from Marc Abraham

Image Credits: Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4