Nir Eyal's Blog, page 34

July 18, 2014

The Link Between Habits and Customer Satisfaction

Nir’s Note: In this essay, Ryan Stuczynski and I discuss the relationship between habits and user satisfaction. Ryan was the Director of Analytics at Fab and today leads growth for theSkimm. Follow Ryan on Twitter or Medium.

Here’s the Gist:

People have limited bandwidth when it comes to mobile app usage and habits matter for long-term engagement.

Usage frequency helps explain whether a company is successfully creating user habits.

Companies able to create more frequent usage habits enjoy higher user satisfaction as measured by Net Promoter Scores.

In the company’s first quarter earnings call, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerburg told Wall Street investors, “almost 63% of people who use Facebook in a month, will use it in a given day.” He continued, “another stat that I think is actually quite interesting is we track how many people use Facebook not just every day … but what percent of people used it 6 days out of 7 days of the week. And that number, for the first time in the last quarter, passed 50%. So, that’s pretty crazy, if you think about it … more than 50% of people have used it 6 days out of 7 days of the week, almost every single day of a week.”

What Zuck is calling attention to is the fact that not only are a lot of users visiting Facebook on any given day, but more importantly, over half of them use Facebook almost every day. Mark’s right, that is “pretty crazy” indeed.

There’s an adage in the television industry that TV viewers have the mental bandwidth for just 12 to 15 channels. After that short list, few other channels matter to most viewers. The same can be said of mobile apps.

For most of us, there are the frequently used apps on our home screens and then there are all the rest on the second, third, fourth screens. As Nir has written previously, “In a world of ever-increasing distractions, habits matter.”

Given consumers limited bandwidth and the challenges of changing user behavior, habits are the key to delivering long-term engagement.

On to the fun stuff …

Let’s take a look at a few of the largest mobile apps — Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and WhatsApp. The data below is from paid surveys conducted using Google Consumer Surveys. In order to minimize the noise in the data, only respondents considered to be regular users were included, which in this case meant using it at least twice per week.

For the purposes of this study, the Net Promoter Score is used as a proxy for user satisfaction and the standard NPS question, “How likely are you to recommend [app name] to a friend?” was asked. The survey was limited to American adults over 18 years of age and 8,000 responses were collected.

Frequency of Weekly Use

Some observations:

Facebook and Instagram are the clear winners when it comes to daily usage.

Twitter and Snapchat are clearly in the daily mix but are behind by a reasonable margin.

WhatsApp is not quite a mainstream daily habit yet. However, it isn’t far off with 31% of respondents using the app often and perhaps on their way to using it daily , thereby joining the two other Facebook apps atop the leaderboard.

To help qualify the data above, if the once per week users were included, the percentage of users using Facebook at least 6-7 days a week would have been 48% — roughly in-line with the global number Zuck referred to in his investor call.

Net Promoter Score by Frequency of Use

You can see by the chart above that there is a clear relationship between app usage and NPS scores. The more days per week the app is used, the higher the NPS of each app across the board.

For those keeping score, the average NPS for each app is: Instagram at 22, WhatsApp at 16, Snapchat at 12, Twitter at -24, and Facebook at -42.

Why do Twitter and Facebook have negative Net Promoter Scores? One reason may be that people are less likely to recommend more established apps since they know their friends already use Twitter and Facebook. Nonetheless, even for these two apps, the more days per week someone uses them, the more likely they are to say they would recommend it.

Just how big is the benefit from a daily habit? From the chart below, you can see a change in usage from occasional (2-3 days per week) to frequent (4-5 days per week) has less of an affect on NPS than the change from frequent (4-5 days per week) to daily (6-7 days per week). There is a disproportionate return on NPS when usage become someone’s daily habit. The one exception here is WhatsApp.

Why might the daily habit not boost NPS for WhatsApp? Well, if your core capability is delivering images and video as entertainment, as is the case on Snapchat and Instagram, perhaps giving a daily fix is very important. However, if WhatsApp is used primarily as an SMS replacement, users may not need the app to entertain them as much as to connect them to others. WhatsApp is arguably less emotionally impactful and serves more as a communication utility than a daily routine.

The Value of Habit

When considering how important viral and word-of-mouth growth can be to helping companies dominate a market, understanding which users are most likely to recommend the product to others becomes a strategic asset. By recognizing the value of user habits, companies can leverage the loyalty of their happiest customers.

To put a value on habits, Nuzzel CEO Jonathan Abrams, pointed out recently, “We asked investors … how many other apps or services they used several times per week, that were not yet worth at least $1 Billion, and the answer was always a very short list.”

Note: This essay was co-authored by Ryan Stuczynski and Nir Eyal

July 3, 2014

Big in Japan and Hooked in SF and Boston

“Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products,” was just published in Japan! I’m happy to announce the book will be translated into at least 6 more languages by the end of the year.

“Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products,” was just published in Japan! I’m happy to announce the book will be translated into at least 6 more languages by the end of the year.

Also, I’ll be giving my half-day Hooked workshop in San Francisco on July 24th and in Boston on October 22nd. Click the links below to learn more.

San Francisco – July 24th

Boston – October 22nd

Blog subscribers get $50 off by using the code “NirAndFarFriends”

I hope to see you there and thanks for reading.

Best,

Nir

June 17, 2014

What Triggers Word of Mouth?

Nir’s Note: Jonah Berger is a marketing professor at the Wharton School and author of the New York Times bestseller Contagious: Why Things Catch On. Contagious explains the science behind word of mouth, how six key factors drive products and ideas to become popular, and how you can apply that science to get your own stuff to catch on.

Whether you run a small business or work for a large one, and whether you sell a product or offer a service, everyone wants their stuff to catch on. More users, more sales, and more growth. But why do some products and ideas become popular while others fail? And how can we harness that science to get make our own stuff more popular?

Whether you run a small business or work for a large one, and whether you sell a product or offer a service, everyone wants their stuff to catch on. More users, more sales, and more growth. But why do some products and ideas become popular while others fail? And how can we harness that science to get make our own stuff more popular?

One of the most shared ads of 2013 was GEICO’s Hump Day. It stars an annoying camel walking through a crowded office interrupting people. “Guess what day it is?” he bellows. People roll their eyes and try to ignore him, but he persists. “Julie! Hey…guess what day it is??? Ah come on, I know you can hear me.”

Finally, he finds someone who responds. “It’s Hump Day,” she says. “Whoot Whoot!” yells the camel. “How happy are folks who save hundreds of dollars switching to GEICO?” a voice intones, “happier than a camel on Wednesday.”

The ad is funny, but it’s not that funny. And GEICO didn’t spend more money showing this ad than its others. So why was the ad so successful? Why did over 20 million people share it?

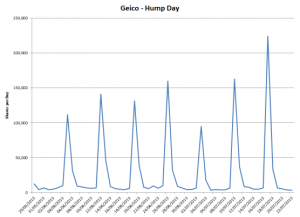

One clue comes from analyzing the temporal pattern of share data. If you look at the number of people sharing GEICO’s Hump Day Ad over time, you’ll notice an interesting pattern. There is a spike in shares and then it goes down. Then another spike and it goes down. And so on, again and again.

Look closer though and you’ll notice that the spikes are not random. In fact, they’re exactly seven days apart. And if you look even closer you’ll notice that they’re always on the same day of the week. That day? Wednesday.

Or as it is colloquially known, Hump day.

GEICO’s ad is equally bad (or good, depending on your preferences) every day of the week. I’ve checked. It’s good or bad on Monday, good or bad on Tuesday, good or bad on Wednesday, etc.

But Wednesday provides a ready reminder, what psychologists would call a trigger, to make people think about (and talk about) the GEICO ad. Because if something is top-of-mind, it’s much more likely to be tip-of-tongue.

The Power of Word of Mouth

Word of mouth drives all sorts of products and ideas to catch on. It’s 10 times more effective than traditional advertising and shapes everything from the products people buy to the services they use.

But why do people talk about some things rather than others?

It might seem random. Just chance that one product or app or service gets more buzz than another. But it’s not. As I talk about in Contagious: Why Things Catch On, six key factors, or what I call STEPPS, drive all sorts of products and ideas to become popular.

Take triggers. If someone said “cats and…” you might immediately think of, well, dogs. If someone said “peanut butter and…” you might immediately think of jelly. Peanut butter is like a little advertisement for jelly. Seeing, hearing, or even thinking about peanut butter makes people think about its frequent partner, jelly.

And because triggers make things top-of-mind, they also shape what we talk about and how we behave. Hershey’s used triggers to help reinvigorate the Kit Kat brand. Sales were down and Hershey’s needed to get people thinking about Kit Kat again. So they started linking Kit Kat to coffee. Taking a coffee break? Have a Kit Kat. Thinking about coffee, think about Kit Kat. Kit Kat and coffee. Coffee and Kit Kat. Best friends forever.

Twelve months later, sales were up almost 40%.

Why? Linking Kit Kat to coffee helped remind people of the brand. And coffee was a great trigger because many people drink coffee frequently, multiple times a day. Making it more likely that they would think of Kit Kat frequently as well.

So what’s your peanut butter? What’s the thing in the environment that will remind people of your product, service, or idea, even if you’re not around? Because you can spend a lot of marketing dollars trying to remind people you exist, or you can link yourself to a trigger and the environment will do the reminding for you. Every time people see that peanut butter, they’ll think of you.

Generating word of mouth or getting something to go viral sometimes seems like magic. Like catching lightning in a bottle. But it’s not. There’s a science behind it. Triggers are only one of the six key principles that drives all sorts of things to catch on. Understand that science, and you can make your own products and ideas more contagious.

Nir’s Note: This guest post was authored by Jonah Berger, the author of the New York Times bestseller Contagious: Why Things Catch On.

June 2, 2014

Is Some Tech Too Addictive?

Addiction can be a difficult thing to see. From outward appearances, Dr. Zoe Chance looked fine. A professor at the Yale School of Management with a doctorate from Harvard, Chance’s pedigree made what she revealed in front of a crowded TEDx audience all the more shocking. “I’m coming clean today telling this story for the very first time in its raw ugly detail,” she said. “In March of 2012 … I purchased a device that would slowly begin to ruin my life.”

Addiction can be a difficult thing to see. From outward appearances, Dr. Zoe Chance looked fine. A professor at the Yale School of Management with a doctorate from Harvard, Chance’s pedigree made what she revealed in front of a crowded TEDx audience all the more shocking. “I’m coming clean today telling this story for the very first time in its raw ugly detail,” she said. “In March of 2012 … I purchased a device that would slowly begin to ruin my life.”

At Yale, Chance teaches a class to future executives eager to know the secrets of changing consumer behavior to benefit their brands. The class is titled “Mastering Influence and Persuasion,” but as her confession revealed, Chance was not immune from manipulation herself. What began as a research project soon turned into a mindless compulsion.

Chance admits she has a weak spot for games, at times, playing until it hurts. “I have had problems with video games,” Chance tells me. “Basically, I can’t have any video game on any computer or phone or anything that I own because the first day that I have it, I just stay up playing it until my eyes bleed.” But during her presentation, Chance was not confessing her addiction to a video game. She was admitting her dependency to something much more benign but which had nonetheless controlled her mind and body. “They market it as a ‘personal trainer in your pocket,’” Chance said. “No! It is Satan in your pocket.” Chance was referring to a pedometer. More specifically, the Striiv Smart Pedometer.

Too Much of a Good Thing?

Admittedly, having rabid users is not a problem most companies face. The much more common dilemma is the opposite: a lack of customer engagement. However, Dr. Chance’s story brings up an ethical dilemma for companies seeking to change user behavior — is there ever too much of a good thing? Although addiction is most often associated with physical dependencies and controlled substances, behavioral addictions can be just as powerful and destructive. Gambling addiction for example, haunts an estimated 2 million Americans and is formally recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Behavioral addictions can wreak havoc on people’s lives and millions suffer from problems related to online gaming, pornography, and other digital dependencies. Even when companies build products intended to help their users (like a gamified pedometer) there is potential for abuse, which begs the question: What responsibilities do companies have to protect users from themselves? Should companies like Facebook and gaming apps take measures to counteract the addictive properties of their products? If so, how?

Having written a book about how to build habit-forming products, I’m often asked about the morality of manipulation and I believe it is time to take ethics seriously.

The Addiction Paradox

The trouble is this: The attributes that make certain products engaging also make them potentially addictive. There is no way to separate the fun of gaming, for example, with its potential for abuse. Social media is exciting principally because it utilizes the same variable rewards that make slot machines compelling. Spectator sports or television watching, enjoyed by billions of people, share common traits with the primary function of illicit drugs — they provide a portal to a different reality. If what we’re watching is engaging, we experience the high of being mentally elsewhere.

For proof, just visit your local sports bar during a big game. Instead of watching the match, watch the people. Look at the fans’ faces. Watch as the flickering images on the screens transport them across the digital cables and satellite signals to a different place. During the most exciting parts of the game, when their eyes stare with laser intensity on what is about to happen, they’ll be in a state similar to what cultural anthropologist and MIT professor Natasha Dow Schüll calls, “the zone.” Though Schüll used the term to describe what drives gambling addicts, the zone defines the same exhilarating mental state experienced through other mediums.

To be clear, games, spectator sports, and social media are wonderful things. Few of us, myself included, would want to live in a world without them. These forms of entertainment provide harmless fun for the vast majority of people who enjoy them. However, each also has a potential dark side.

Dr. Chance’s experience with the Striiv pedometer provides a telling example. According to Striiv’s CEO, David Wang, the device is meant to help inactive people get moving by collecting points as they walk. Wearers of the pedometer use their points to build virtual worlds in the company’s Farmville-like app called “MyLand” but Wang admits some people, like Chance, go overboard.

As with many obsessions, it was only a matter of time before Chance went too far. At the end of one particularly active day, Chance said she received a late-night notification from the app challenging her to walk a few flights of stairs. She accepted the challenge and marched quickly down and back up the steps leading to her basement. As soon as she completed the first challenge, she received another offer — walk four more flights and the app promised to triple her points. “Yes, of course! It’s a good deal!” Chance thought.

That’s when Chance says she lost control. For the next two hours she walked the stairs to and from her basement like a fitness-crazed zombie. By two in the morning, she had climbed over 2,000 stairs — far surpassing the 1,576 steps to climb to the top of the Empire State Building.

It wasn’t until the next morning that Chance felt the repercussions of what she had done. The Striiv spree left Chance with a painful hangover. The incessant jarring had strained her neck making normal walking painful and her Striiv-motivated fitness goals impossible. “When the neck injury happened I had to take a break,” Chance said. “Which allowed me to finally acknowledge what my husband had been saying for a while — that I had a problem.”

Intervention

Though Dr. Chance’s story reveals the power some technologies have on some people, the fact is most people do not get hooked. According to Wang, only 3% of users walk the 25,000 daily steps Chance was logging. Like most potentially addictive technologies, the percentage of users who meet the definition of engaging in, “continued repetition of a behavior despite adverse consequences,” is very small. Studies show that relatively few people are susceptible to addiction and that even those who do get addicted quit their dependencies when they change life stage or social context. However, there are people who can not stop, even when they want to.

The current thinking among technology companies is that too much is never enough. Limitless time scrolling Facebook feeds, hours of pinning on Pinterest, days spent leveling-up in online games — there are no bounds. In the name of personal responsibility, companies leave addicts alone, never interrupting their zone-state cocoons.

While a laissez-faire customer relationship is the right approach for most users, when the user is addicted — no longer in control and wanting to stop but can’t — companies should intervene. Standing idly by while reaping the rewards of users abusing their product is no longer acceptable — it is exploitation. Thankfully, and for the first time, makers of potentially addictive technologies have the power to do something.

Outside of consumer tech, companies making potentially addictive products can claim ignorance regarding who is abusing their products. Makers of alcoholic beverages for example, can throw up their hands and claim they have no idea who is an alcoholic. However, any company collecting user information can no longer take cover under the same excuse. Tech companies know exactly who their users are and how much time they are spending with their services. If they can hypertarget advertising, they can identify harmful abuse.

In fact, some companies have already started limiting certain features to people who overuse their sites. StackOverflow, the world’s largest technical question and answer site, deprecates certain features to limit use. Jeff Atwood, the company’s co-founder, says the system was designed to not only improve the quality of content on the site but also to protect susceptible users. “Programmers should be out there in the world creating things too,” Atwood writes, making the point that he wants StackOverflow to be a utility, not a mindless distraction.

Use and Abuse

Though Dr. Chance says she was able to kick her behavioral addiction to the Striiv pedometer on her own, it took physical pain to help her realize she had lost control. “The blessing of the stairs episode was the neck injury.” It wasn’t long after she realized she had a problem that Chance decided to give up using the Striiv for good. She vowed to never use the pedometer again and mailed it to her sister far away in Massachusetts.

When it comes to potentially addictive products, companies should not wait for users to harm themselves. Companies who know when a user is overusing their product have both an economic imperative and a social responsibility to identify addicts and intervene.

Companies have an obligation to establish what I call a, “Use and Abuse Policy,” which sets certain triggers for intervention and helps users retake control. Of course, what constitutes abuse and how companies intervene are topics for further exploration, but the current status quo of doing nothing despite having access to personal usage data is unethical. Establishing some kind of upper limit helps ensure that users do not abuse the service and that companies do not abuse their users.

—

Here’s the gist:

- When it comes to potentially addictive technology, there are two types of users — those who use the product under normal parameters and those who abuse it.

- Addiction is defined as, “continued repetition of a behavior despite adverse consequences.” Generally, a relatively small number of users form addictions with their technologies.

- However, companies who have information on which users are abusing their service have a moral responsibility to intervene.

- Drafting a “Use and Abuse Policy” that sets the upper limits of normal use and defines what constitutes harmful overuse, is good for both the company and its users.

—

What do you think? Should companies building potentially addictive products have a “Use and Abuse Policy”? What else can companies do to limit abuse of their products?

May 15, 2014

Can Online Apps Change Real-Life Behavior?

Nir’s Note: This guest post is written by Max Ogles. Max is an editor for NirAndFar.com and heads marketing for CoachAlba.com, a mobile health startup. Follow him on Twitter and read his blog at MaxOgles.com.

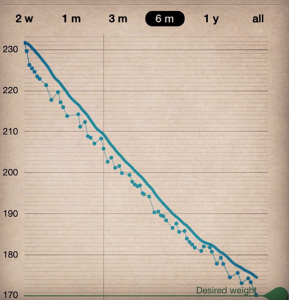

Weight gain happens pound by pound, over many years, and that’s how Dave Haynes found himself sixty pounds away from a healthy BMI. In his career, Dave was immersed in the startup world; he helped start Soundcloud, which allows anyone to share and produce music and has over 10 million users. So when he ultimately resolved to reverse this disturbing weight trend, he naturally looked to technology for the solution; he downloaded the popular fitness apps and bought an Internet-connected Withings scale. But could these online apps help him achieve real-life behavior change?

Weight gain happens pound by pound, over many years, and that’s how Dave Haynes found himself sixty pounds away from a healthy BMI. In his career, Dave was immersed in the startup world; he helped start Soundcloud, which allows anyone to share and produce music and has over 10 million users. So when he ultimately resolved to reverse this disturbing weight trend, he naturally looked to technology for the solution; he downloaded the popular fitness apps and bought an Internet-connected Withings scale. But could these online apps help him achieve real-life behavior change?

For Dave, the answer was “Yes.” In just six months he returned to a healthy weight. And when I asked if the apps helped, he didn’t hesitate. “I couldn’t have done it without them,” he told me. “I wouldn’t say any one app was the most important, but together they absolutely made it possible to achieve my goal.”

Dave’s success was a personal cocktail of technology to fit his personality, and it worked. But the variety of apps and the even greater variety of personalities that exist in the world make it questionable whether a single behavior tech product can work for everyone.

On the Screen vs. In Real Life

Most technology products are looking to change behavior in some form or another. With the help of psychology, many online companies are leveraging the feedback loops within their products to form strong, addictive user habits. Whether a company is focused on user engagement, growth, or monetization, the ultimate goal is to get people to take action. From push notification triggers to highly enticing variable news feeds, dozens of design strategies have cultivated tech habits that we rely on; there’s a reason that 60% of Facebook users are active on the site daily.

But when you’re trying to change behavior, getting users to engage within the app or web platform isn’t enough. That’s because no matter how many times a user logs in to WeightWatchers online or opens the Nike+ app, the products are really only successful if users take action in real life. For behavior change products to be successful, users have to go to the gym, eat a healthy salad, or say “no” to ice cream–not just scroll mindlessly through cat memes.

The Science of Captology

One of the most popular behavior change models used by behavior tech companies is that of Stanford professor BJ Fogg, a pioneer in the area of persuasive technology. Fogg even coined the term “captology”–Computers As Persuasive Technology. The gist of Fogg’s model is that for any behavior to occur, three components must be present: motivation, ability, and a trigger.

One of the most popular behavior change models used by behavior tech companies is that of Stanford professor BJ Fogg, a pioneer in the area of persuasive technology. Fogg even coined the term “captology”–Computers As Persuasive Technology. The gist of Fogg’s model is that for any behavior to occur, three components must be present: motivation, ability, and a trigger.

For example, if you’re trying to get yourself to go to the gym, that might mean having the desire to exercise (motivation), having the time and resources to get to the gym (ability), and setting a calendar event to remind yourself to go (trigger). The best health and fitness apps incorporate some or all of these components in the user experiences that they offer. And that’s just to get yourself to the gym one time! In order to make a significant lifestyle change, like losing a lot of weight or quitting smoking, motivation, ability, and triggers must be consistently optimized for the new behavior.

Of the three components, triggers are probably the easiest to implement using technology. Emails, text messages, and push notifications can be sent to us on our smartphones at any time and in any location to poke us towards good behavior. The real question is how well apps can offer the motivation and ability that people need to achieve their goals.

Real Addictions, Real Motivation

Dozens (likely hundreds) of apps are designed to motivate users. Fitocracy uses gamification to help users earn rewards, accept challenges, and advance to a new level. CarrotFit entertains users by berating them into shape with humorous insults. With the Lift app, an entire community of like-minded individuals is there to offer “props” any time you’re successful with a habit. And that’s just to name a few of the apps and types of motivation that are out there.

One of the most unique “motivating” technologies is Stickk.com, which relies on the economic principle of loss aversion to create motivation. Loss aversion, oversimplified, is the idea that people are more motivated by the prospect of losing something (e.g. money) than they are by the prospect of a reward. Most people who sign up for Stickk choose a goal, like “I want to quit smoking” and then commit to a consequence if they don’t achieve their goal: donating money to an organization that they despise, like a political party.

Though I’ve signed up for Stickk.com, I’ve never had the guts to put it to the test, so I went searching for someone who had. Plus, I wanted to know how powerful the effects of loss aversion really were, so I went on the hunt for someone with a real addiction. I searched through some public profiles on Stickk.com and that’s how I found Jeremy Stevenson, a student at the University of Adelaide in Australia. Jeremy wasn’t addicted to meth or heroin but instead a 21st century drug fueled by technology itself: pornography.

“There were a lot of things I didn’t like about [pornography],” he told me. “I felt guilty after I looked it up and I found myself looking up dirtier and dirtier shit. Also, it changed my expectations of sex and also what women looked like naked, so I was disappointed when I started having my first sexual experiences.”

Over the course of about 8 months, Jeremy set commitments with Stickk to avoid pornography altogether. And did it work? “I had a 100% success rate with Stickk, it worked remarkably,” he said. “It’s difficult to explain why, perhaps the notion of my money being donated to some horrendous cause like the American Republican Party, perhaps the knowledge of how disappointed I would be if I failed. …It was the pinnacle of commitment and I really hate failing at a commitment that I value.”

For Simplicity’s Sake

For Jeremy, Stickk definitely supplied the motivation necessary to change. And with the variety of technologies available, it seems that most people are likely to find at least one that offers the type of motivation that will truly help them. The only remaining ingredient in BJ Fogg’s recipe for behavior change is ability.

One way to think about ability is to think in terms of simplicity. Is the app simple enough? And, more importantly, is the action, such as “going for a run” or “saying no to dessert” simple enough? As Fogg says, “Simplicity differs by person and by context,” meaning that all the tiny details of our environent matter significantly, and lead to his conclusion: “Simplicity lies outside the product.”

This is where the true effectiveness of behavior change apps comes seems debateable. Even the best apps–with simple and intuitive UI, engaging content, and research-based methodology–are helpless when it’s time to actually go for a run.

Limititations on our time, money, and the level of effort we’re willing to exert all affect simplicity. And, to complicate things further, these limitations are constantly changing. It may be relatively simple to spend 30 minutes at the gym on a Saturday, if you have fewer weekend appointments on your calendar. But by Monday, when your calendar is packed and you only have intermittent free time, going to the gym becomes significantly more difficult. If innovative apps can find ways to make the real-life behavior challenges easier, these apps will succeed.

For example, think about the time it takes to track calories. There are plenty of apps available to do this, but anyone who’s counted calories knows that logging fresh food meals (which are generally the healthiest) is a painstaking process. So much so that for many people the challege isn’t eating healthy food, it’s preparing it. After losing 100 pounds, former Apple employee Michael Grothaus gained back the weight for that very reason. The problem frustrated him so much that he built a solution called SITU–a smart-scale and calorie counting app combo that simplifies the process of tracking fresh foods. Though it’s too early to tell, SITU seems to fill the void between online app and real-world simplicity by making a cumbersome task fairly quick and efficient. As technology improves, I suspect that more apps will find ways to buoy users with ability by simplifying physical tasks

The Future of Tech Change

If you visit the website of just about any behavior change tech product, you’ll see testimonial after testimonial from users lavishly extolling the app that finally made the difference–for them. There’s still no pill, no app that solves everyone’s bad habits, and with the complexity of human psychology will likely never be one. In the mean time, the weight loss apps, fitness games, and wearables should offer something unique for just about everyone. And the apps that remove as much friction as possible, while still inspiring users, are the most likely to succeed.

Thanks to Dave Haynes , Jeremy Stevenson, and Michael Grothaus for the stories they shared for this essay.

April 20, 2014

What Tech Companies Can Learn from Rehab

Nir’s Note: This guest post is written by Max Ogles. Max is an editor for NirAndFar.com and heads marketing for CoachAlba.com, a mobile health startup. Follow him on Twitter and read his blog at MaxOgles.com.

Last year, The Huffington Post published some fascinating statistics about the U.S. prison population. The headline for the article blared, “America Has More Prisoners Than High School Teachers.” It’s no secret that the United States has a high rate of incarceration, not to mention a recidivism rate of nearly 60% for serious criminals.

Last year, The Huffington Post published some fascinating statistics about the U.S. prison population. The headline for the article blared, “America Has More Prisoners Than High School Teachers.” It’s no secret that the United States has a high rate of incarceration, not to mention a recidivism rate of nearly 60% for serious criminals.

These stark facts put into perspective the incredible work of the Delancey Street Foundation, a drug and rehabilitation center based in San Francisco. Delancey Street accepts the most hardened criminals and drug addicts; most have multiple felony convictions. But despite the difficulty associated with overcoming a criminal past, over 14,000 Delancey residents have returned to society as productive citizens. Perhaps Delancey’s most impressive accomplishment is the fact that over 90% of its graduates never return to prison.

I first learned about Delancey Street when I read the book Influencer. The book details the rehabilitation process used at the facility. After reading about Delancey Street, I asked the same question most people ask when they hear about Delancey’s incredible success: “How do they do it?” The authors of Influencer answer this question by describing the process of teaching new behaviors to those admitted to the program.

The more I thought about Delancey Street, the more I began to connect how some of the world’s most successful technology companies utilize similar principles in the design of their products. The strategies Delancey Street uses to help ex-convicts overcome bad habits can be applied to technology products intended to help users learn new beneficial behaviors. Since most of us don’t work with hardened criminals and addicts, let’s take a look at how we can use the behavior change principles from Delancey Street to create better products.

It’s About Us

When people arrive at Delancey Street, they’re looking for help. They’ve realized they can’t overcome their drug habits or tendencies towards crime on their own. In a similar way, new users show up to your product hoping it will solve a problem. And though it may sound counterintuitive, it is important to give users a “responsibility” when they arrive — ask them to complete a task that teaches them the importance of your product and how it can help them connect to something larger than themselves.

Shortly after entering the Delancey Street program, each new resident receives a small assignment, such as learning how to set the table at the foundation-run restaurant. The revenue from the restaurant helps fund the program and after just a few days of doing this small job, residents receive an additional responsibility, for example, training the newest incoming residents.

At this year’s Habit Summit, Josh Elman an early Product Manager at Twitter, stressed the importance of the on-boarding process to technology companies. “It’s your moment to take as much time as you possibly can from this user to train them on what’s important in your product,” Elman said. Twitter’s on-boarding process is able to assign users small tasks that teach them why the service is valuable to them, namely, it connects them to other people in a valuable new way. Just like at Delancey Street, Twitter teaches new users that the product isn’t just about them, it’s about others.

At this year’s Habit Summit, Josh Elman an early Product Manager at Twitter, stressed the importance of the on-boarding process to technology companies. “It’s your moment to take as much time as you possibly can from this user to train them on what’s important in your product,” Elman said. Twitter’s on-boarding process is able to assign users small tasks that teach them why the service is valuable to them, namely, it connects them to other people in a valuable new way. Just like at Delancey Street, Twitter teaches new users that the product isn’t just about them, it’s about others.

Easy Steps to Success

In applying the principle of starting with small tasks, it is important to guarantee success. The job must be easy enough that any user can accomplish it quickly. Delancey Street is careful to give residents tasks they can handle at every step of the program.

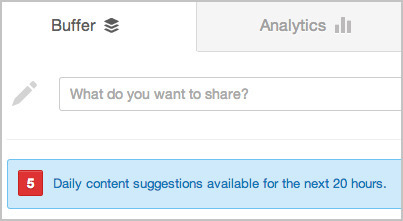

A great example of guaranteeing success online can be found in the registration process used by a social media tool called Buffer. The service’s first goal is getting people to sign up, but that action alone isn’t enough unless users ultimately share content.

A great example of guaranteeing success online can be found in the registration process used by a social media tool called Buffer. The service’s first goal is getting people to sign up, but that action alone isn’t enough unless users ultimately share content.

Buffer realizes a key behavior for new users is to schedule content; they also realize finding new content, deciding to share it, and scheduling it, can be inconvenient, especially if a user is learning how Buffer works for the first time. To ensure users share a post and realize the full benefit of the product, Buffer hands them high-quality curated articles.

By offering-up good content for users to immediately share, Buffer guarantees anyone can be successful using their technology – all the user has to do is hit “Schedule.”

Making a Contributor

Just a few days after Delancey residents check into the facility, they’re given responsibility to oversee other residents. In this way, Delancey is able to keep their newest residents accountable and teach other residents new responsibilities. This principle manifests in technology products when companies help consumers become contributors.

Many companies depend upon user generated content to keep their online communities engaged. Pinterest, for example, relies upon users pinning and re-pinning interesting images from the web. Tumblr needs users to post content they find to their own tumblelog. Instagram needs users to find and filter fantastic images to provide content for other users’ photo feeds.

These products succeed by teaching users what is most important about their services and simplifying the steps to participate in making something other people value. Each of these services turns content consumers into content contributors.

Using principles from one of the most successful behavior change programs in the world, tech entrepreneurs can help users live better. By giving people a way to connect with others, providing simple tasks to make them successful, and enabling them to contribute towards a shared purpose, services can sustain ways to benefit the individual as well as the community.

Note: This guest post is by Max Ogles. Photo Credit: h.koppdelaney

April 1, 2014

The Secrets of Addictive Online Auctions

Nir’s Note: This guest post was authored by Lisa Kostova Ogata, one of the first product managers at Farmville and a VP of Product at Bright.com (sold to LinkedIn). While at Zynga, Lisa learned how to shape user behavior, but in this essay she describes her surprise when she found herself unexpectedly hooked.

I don’t consider myself a gambler. I’m the person who places a minimum bet at the roulette table with the specific intent of getting a free drink — after all, it’s cheaper than buying one at the bar. Yet, there I was on a Monday night, glued to my computer screen for over an hour as I watched an online auction. I couldn’t resist.

I don’t consider myself a gambler. I’m the person who places a minimum bet at the roulette table with the specific intent of getting a free drink — after all, it’s cheaper than buying one at the bar. Yet, there I was on a Monday night, glued to my computer screen for over an hour as I watched an online auction. I couldn’t resist.

I experienced a mix of emotions as my adrenaline rushed and the clock ticked. Minutes earlier I didn’t even know the product on sale existed, but now I had to have it. Worse still, I couldn’t peel myself away from the screen. I needed to cook dinner, but I decided it could wait. I ached to go to the bathroom, but I had to hold it.

As the auction ticked on, the realization finally set in. I understood what was going on. It became painfully clear to me that I had fallen prey to an online compulsion. I should know, I had designed these sorts of habit-forming technologies as a product manager working on Farmville for Zynga.

The Hold

It’s the feeling that takes control of your fingers when you can’t stop eating popcorn during an exciting movie. It’s the desire to keep playing an online game. It’s the need to keep endlessly scrolling through a social media feed, again and again. It’s the feeling that traps your inner critic inside a zombie shell, temporarily suspending rational judgment.

It’s what Natasha Dow Schüll calls “Addiction by Design” in her book by the same name. I heard her speak at Nir Eyal’s Habit Summit in a crammed conference hall at Stanford University the day after I fell into my own online auction addiction. Dr. Schüll described the science behind how designers of casino slot machines create their perfect mouse traps. Their machines come complete with sensory stimuli, an altered sense of reality, and a false perception of winning. I silently thanked Nir for inviting Dr. Schüll to hold a mirror up to the audience to reveal habit’s ugly cousin — addiction. At times, it’s hard to tell the two apart.

The Habit Summit and my online auction binge made it clear to me that my work as a practitioner of behavior design did not guarantee immunity from potentially addictive technology. Having worked as a product manager on Farmville and other Zynga games, I thought I had learned all there was to know about creating user compulsions. Buildable items, quests, drip rewards, mystery boxes — these were the tools of my trade. I had witnessed the power of compulsion in social games but what I experienced on an online auction site called Quibids, sent shivers down my spine.

How to sell a $4,000 iPad

Quibids has many things in common with gambling. The online auction site lets users bid on popular items, such as iPads and Playstations, and potentially win them for a fraction of the retail price. The design is as brilliant as it is sinister. To participate in a Quibids auction, users buy bids at a cost of 60 cents each. The auction has a count-down timer that “sells” the item to the highest bidder when the clock reaches zero. Every time someone places a bid, the price of the item is raised 1 cent and 10 seconds are added to the timer.

Quibids has many things in common with gambling. The online auction site lets users bid on popular items, such as iPads and Playstations, and potentially win them for a fraction of the retail price. The design is as brilliant as it is sinister. To participate in a Quibids auction, users buy bids at a cost of 60 cents each. The auction has a count-down timer that “sells” the item to the highest bidder when the clock reaches zero. Every time someone places a bid, the price of the item is raised 1 cent and 10 seconds are added to the timer.

For example, an iPad which retails for $499 was recently sold for $65.13. The winning bidder used 366 bids costing $219.60 ($0.6 x 366) plus the sale price for a total out of pocket cost of $284.73. Not bad for a brand new iPad Air.

Quibids prominently displayed these “savings” after the auction ended to showcase the value of the deal. What Quibids did not show however, was that the auction netted the company $3,972.90. A total of 6,513 bids, each costing 60 cents, were spent on the auction. In other words, Quibids figured out a way to sell an iPad for over eight times the retail price.

Knowing the rules of the game, a rational person should construct a strategy that goes something like this: Set a maximum budget of bids that never exceeds the retail value of the item. Then, wait for the clock to go down to 1 second before placing a bid. Next, wait for the number of bidders to decrease before starting to use one’s own bids — ideally waiting on the sidelines for other bidders to burn through their cash before making a bid. That’s what I should have done. But of course, I didn’t.

Upping the Ante

Unfortunately, the moment the auction starts, logic tends to fly out the window. The constantly changing seconds on the countdown clock transfixed me, especially when they started flashing red and got oh-so-close to zero before bouncing back again. The majority of bids are placed when the clock has at least a few seconds to go, making for a very bumpy emotional roller coaster. Often times, two players enter a bidding war whereby one person immediately counters the other, seemingly out of spite.

Quibids has also designed a way to increase the velocity of bidding. A user can place a package of bids triggered at a certain price threshold using the so-called, “BidOMatic.” Using the BidOMatic submits bids while the user is away. This mechanic enables more bids in the auction as well as allowing players to bid on multiple auctions simultaneously.

Of course, the BidOMatic increases the amount of money extracted from the user while doing little to increase their actual chances of winning. By using the BidOMatic, the user easily forgets the total cost of the bids. Even though the amount of bids spent on an auction is displayed below the item, it’s easy to lose track of how much you’ve spent on each auction when playing several auctions at once. A user can easily pay over retail if not careful.

Judging by the auction stats displayed on the site indicating whether bidders were placing single bids or BidOMatic bids, I estimated that at least half of the bids were placed using the automatic tool.

The last piece of my strategy — waiting until the competition was exhausted to place a well-timed bid at the one second mark — backfired. Quibids locks auctions after a certain number of bids have been placed, restricting the auction to the people who’ve placed recent bids and who have bid a minimum number of times. This simultaneously raise the minimum pay-in, while creating what is known as a “false win.” The remaining players are under the impression that their odds of winning the deal are now higher because there are fewer bidders. However, there is little actual upside. What Quibids has done is identify the power players and pits them against each other to maximize profit.

Lessons from an Addictive Technology

Quibids has undoubtedly borrowed much from the slot machine playbook and has made improvements along the way. The key drivers of user compulsion can be summarized as follows:

Slot machine incremental bidding – A few cents doesn’t sound like much but hundreds of bids make it easy to lose track of how much you’ve spent in total.

Tapping into the compulsion to win – The initial prize of an “iPad for half the price” is an attractive hook. But as Schüll puts it, the “hold” is the compulsion to dominate the auction and beat the competition into submission. At Farmville we’d call the competitive type of player “a min-maxer” – they’d always know which crop had the most advantageous yield per minute in order to earn the most points as quickly as possible.

An asymmetric marketplace — For every person that gets a deal there are at least a dozen who lost — they paid something and got nothing in return. In a way, this is a similar concept to a mystery box in games, where the gamer’s willingness to pay increases with the inclusion of rare and valuable items in the loot.

The pressure cooker – There is nothing like a count-down timer to create a sense of urgency and the compulsion to reach for the wallet or click on the “bid” button. Social games and retail stores alike recognize the power of flash sales and there is a spike in purchases whenever a company reminds a user that they need to act quickly because a deal is going away. Experiments at Farmville showed that items would sell much better if they were being offered as a limited edition.

Identifying the big spenders – Locking the auctions late into the bidding creates a false sense of being close to a win. Creating an exclusive club increases the willingness to spend, squeezing more revenue out of power bidders.

A careful look at the psychology of Quibids reveals powerful mind tricks that serve as a case study in user engagement mechanics as well as a cautionary tale. As far as I’m concerned, I’m cashing in my remaining bids on Quibids so I can break my addiction and return to my relatively benign shopping habit — hunting for deals on Amazon.

Note: This guest post was authored by Lisa Kostova Ogata

March 27, 2014

Teach or Hook? What’s the Real Goal of Online Education?

Nir’s Note: This guest post is written by Ali Rushdan Tariq. Ali writes about design, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation on his blog, The Innovator’s Odyssey.

As I clicked the big green “Take This Course” button, I became acutely aware of an uneasy feeling. This would be the 22nd course I’d have signed up for on Udemy.com, one of the world’s leading platforms for teaching and learning classes online. I had become a binge-learner.

Or had I? After scanning my enrolled course list, I gathered the following stats:

And so the uneasy feelings inside bubbled to the surface. With 13 courses left virtually untouched since enrolling (the price ranging from free to $30 for each of them) I naturally started deriding myself. I thought I was a non-finisher, bad at commitments, and lacked focus. Perhaps even a compulsive buyer, financially carefree, or worse yet, a wanna-be learner. Perhaps it was some combination of the above?

In other words, I thought something was wrong with me. Then I remembered the teaching of designer Donald A. Norman in his most popular work, The Design of Everyday Things. In it, he extolls that people’s ineptitude in using objects stems not from their own incompetence but from poor design. He says, “… people feel guilt when they are unable to use simple things, guilt that should not be theirs but rather the designers and manufacturers of the object.”

This gave me a little respite and I began to wonder: Is Udemy well-designed, because of its ability to convince me to continuously enroll for new courses, or is it poorly-designed, because of its inability to help me follow-through with my learning objectives?

In the rest of this article, I step through Nir Eyal’s hook framework to show how some specific design decisions lead to Udemy’s seemingly diametric user experiences.

Triggers

Udemy operates in the education sector and thus, the triggers that drive students to it are not that difficult to understand. The external triggers are quite explicit. They come largely in two types: 1) email triggers and 2) on-site triggers.

1) Email Triggers

Once a user signs up as a member of the site, the company periodically sends promotional emails to engage them. For me, the most compelling emails advertise course sales. Interestingly, these emails generally tend be sent by the teachers of the courses rather than by Udemy staff. This tends to make the emails targeted and relevant for students.

2) On-site Triggers:

Udemy’s course catalog is an aesthetically pleasing display of courses with compelling titles (e.g. “7 Comedy Habits to Becoming a Better Speaker”) laid out in aisles upon aisles of course offerings. The easy-on-the-eyes look and feel of the course listings coupled with the announcements of deep discounts makes browsing Udemy similar to grocery shopping — you enter looking to buy milk, then leave with some frozen fruits, a bag of potato chips, a jar of pickles and some condiments.

Over time, if users follow through on these external triggers enough, Udemy will be the first thing they think of when they want to learn a new skill. On a personal note, I have stepped through the above external triggers so frequently that the next time I find myself wanting to learn mobile app development, I will likely make it a point to search for a course on Udemy first.

Action

Most students search Udemy’s course offerings when they are motivated to learn a particular skill, from Excel mastery to learning how to sing. This desire may come from an innate curiosity or perhaps when a job prompts the user to strengthen or complement their existing skills.

But motivation alone is not sufficient; in order for users to take action, they must also have the ability to do so. Similar to Amazon’s one-click shopping, Udemy makes enrollment in courses as easy as possible — first, popping-up a purchase window and second a purchase order. Your credit card details are kept on file, saving you time and effort on every purchases.

When the ability to enroll is this easy, deep discounts boost motivation. When the right triggers are present, BJ Fogg’s Behavior Model predicts that students will follow through with the intended behavior.

Rewards

By virtue of the constantly changing roster of courses on a wide range of topics, Udemy’s offering has inherent variability. Depending on what courses you are taking, you may learn how to code an app in Javascript and then learn how to get better sleep. This variability keeps things interesting and enticing.

Udemy leverages Reward of the Hunt – that is to say, our craving for amassing possessions. This is manifested in the site’s two main lists that students use most often — the Learning list and the Wishlist. The former displays courses the student has enrolled in, while the latter displays courses that the user wants to track for future reference. I found myself adding more and more courses to my Wishlist, even if some of them only partially interest me. And yes, a number of these courses from my Wishlist, eventually ended up in my Learning list.

Investment

The final major design decision Udemy employs to keep users habitually coming back, is displaying how much they have invested in their learning. The site offers a real-time progress bar to show students what percentage of a course they have completed. The way courses automatically move to subsequent lectures after completing a section makes progress appear seamless and makes students more likely to return.

Possible Improvements

The product designers at Udemy deserve credit for implementing decisions that lead to higher user enrollments. The Hook framework demonstrates a number of key areas that Udemy has benefitted from in its rapid growth to 2 million members. Specifically they have made it as painless as possible to discover and sign-up for courses while providing relevant and timely triggers for users to act on their motivations to purchase.

But if the company’s goal is to help people learn, it should more deliberately invest in enabling users to not only sign up, but also to see them through to the end. The danger of not doing so will be that students like me who find themselves overwhelmed by their course-loads suffer a kind of course fatigue and avoid coming to the site altogether. Here are some ways I suggest that Udemy’s can address their completion challenges:

1) Invest in Rewards of the Tribe

Currently, the social aspect of Udemy’s offering is very limited. In my six months on the site, I have yet to collaborate with other students and I am not even sure how I would do so. Like going to the gym with workout buddies, a supportive community would provide camaraderie to encourage members to stick to their lesson plans and see themselves through to completion. While each course does have a discussion section, the site does not provide many cues or incentives for students to collaborate.

2) Implement course-based triggers

In its current design, once users sign up for a course, they are only contacted when a teacher has a message to broadcast. Udemy should consider sending reminder messages or emails to prompt students to revisit courses they have not completed. A harsher and more tenuous measure might be to set caps on students’ course-loads, much like at traditional schools. A hard limit of say five courses at a time will act as a trigger for students to buckle down and complete their enrolled classes. While this might hamper sales initially, it may very well lead to higher course-completion rates in the long-term and thus higher customer satisfaction.

I believe that as long as Udemy helps its customers achieve their learning goals (as opposed to simply amassing more course sales) it has a bright future.

What other ways do you think Udemy and other online courses could increase completion rates? Let me know in the comments section below.

Note: This guest post is written by Ali Rushdan Tariq, who writes at The Innovator’s Odyssey.

March 17, 2014

Using Mind Control to Raise Startup Cash

Nir’s Note:

This guest post is written by Michael Simpson. Michael is the co-author of The Secret of Raising Money, which he wrote with Seth Goldstein.

Nir’s Note:

This guest post is written by Michael Simpson. Michael is the co-author of The Secret of Raising Money, which he wrote with Seth Goldstein.

Raising money for a startup is like sex. The more unattainable you seem, the better your chances of getting lucky. Also, the more interest you receive from others, the more appealing you will become to everyone else.

This essay discusses two psychological principles at work in an entrepreneur’s fundraising efforts: social proof and scarcity. Nir has discussed both in previous blog posts regarding product design. In this article, I’ll take you through the mechanics of each, and show you how entrepreneurs use these tools to close their rounds.

SOCIAL PROOF

“If you’re walking down the street and everyone is looking up at the sky, you look up at the sky.” -Babak Nivi, AngelList

Social proof, in essence, is the herd instinct: people are more compelled to do something if others are already doing it. In the context of fundraising, social proof dictates that investors are more likely to invest in a company if others are already invested, or at least showing interest. This effect has more power if the initial investors are well regarded within the investor community. Social proof is why getting a commitment from the first investor in a round is significantly more challenging than the final investor: everyone is looking to somebody else to provide validation before they commit.

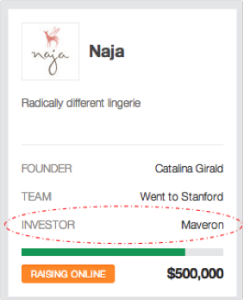

Social proof is the reason AngelList, a platform for startups trying to raise money, displays the names of current investors on the profiles of registered startups. Below is part of the profile for Naja, currently raising $500,000:

So how do shrewd entrepreneurs take advantage of social proof to close a round of funding? Firstly, if they have already taken money from investors, they advertise this fact in conversations with prospective backers. If they haven’t yet taken in money, they tell potential investors about positive signals and interest that they are receiving from others. When done correctly, this can create a feeding frenzy of interest.

Because of the power of social proof, the best approach to fundraising is to condense it into the smallest window of time possible. Ideally, entrepreneurs approach all investors at once. This increases the likelihood of being able to use verbal offers to drum up interest from others, which in turn they can use to attract still others. If companies are out in the market raising money for too long, they begin to run the risk of being perceived as “shopped,” as investors begin to wonder what is wrong with the business. This is the negative side of social proof and can create a death spiral where more and more investors stay away from a deal because they fear other investors are doing the same.

Companies also utilize social proof from name-brand advisors, which is one of the reasons many startups go to such great lengths to recruit industry icons in their respective fields. Endorsements from well-known funds and individuals will make a business more appealing.

Investors may argue that social proof is rational and indeed some VC funds are momentum investors whose explicit strategy is to follow the investments of so-called, “smart money.” We’ve even met investors who strictly do follow-on investments in companies who have received funding from one or more of a list of the top 30 funds within the last 90 days.

Some investors shun social proof. Fred Wilson says, “Make up your own mind. Don’t follow the herd. Don’t chase.” But that’s easier said than done. Social proof is an unavoidable component of the VC’s decision process, so successful startups learn how to use it to their advantage.

SCARCITY

“The best entrepreneurs made me feel like the train was leaving the station whether I got on board or not.” Jon Callaghan, True Ventures

Scarcity is the principle that a person will be more compelled to act if he believes the opportunity will soon vanish — it’s why infomercials demand that you “order before midnight to receive half off!” In the context of fundraising, investors will be significantly more interested in participating in a financing round if they believe space is running out. Sufficient scarcity triggers a fear within an investor that he may be passing up on a big opportunity, increasing the chance he will invest. It is FOMO at its finest.

One way entrepreneurs utilize scarcity is by being transparent about how much there is left in a round when they are nearing its close. Investors are a lot more compelled to invest if there is $100,000 left in a $1m round then if there is $900,000 still available. I recommend keeping round sizes modest to test the waters initially and upsizing as the company garners more interest.

Without the perception of scarcity, there is a danger that a deal will grind to a halt. VC’s are incentivized to delay and retain optionality if at all possible: If an investment opportunity isn’t going to disappear, and the investor isn’t 100% sure about the investment (they almost never are), his best bet is to delay as long as he can (and gather more information as the company progresses) rather than turn the company down.

WHY DOES IT WORK LIKE THIS?

So why do emotions play such a significant role in early stage investing? There are two primary reasons.

The first is that early stage venture capital is one of the most information-scarce forms of investing around. Let’s compare VC to hedge funds. When a hedge fund is evaluating a new investment in a publicly traded company, one of the first things the analyst will do is to build a financial model based on publicly available information, specifically historical financial and operating data from filings, press releases, and earnings calls. This data will form the cornerstones of the analysis and inform the ultimate investment decision.

Such information simply does not exist for early stage companies. They do not have financial reporting requirements. They do not have an operating history. And financial forecasts, especially at the very early stage, are frequently a little more than a starry-eyed guesstimate. The absence of data means emotions plays a larger role in decision making than might otherwise be the case.

The second reason is that all human beings are wired to respond to social proof and scarcity. We tend to follow the herd and we automatically assume that scarce resources are more valuable. That’s why we observe social proof and scarcity at work in so many seemingly disparate spheres from the dating world to venture capital investing.

Photo Credit: kevin dooley

Note: This guest post is authored by Michael Simpson. Use discount code “nirandfar” to get 20% off his book, The Secret of Raising Money, until March 25th.

March 12, 2014

How To Build Habits In A Multi-Device World

Nir’s Note:

Michal Levin asked me to write this essay for her new book, Designing Multi-Device Experiences.

Nir’s Note:

Michal Levin asked me to write this essay for her new book, Designing Multi-Device Experiences.

Allow me to take liberties with a philosophical question reworked for our digital age. If an app fails in the App Store and no one is around to use it, does it make a difference? Unlike the age-old thought experiment involving trees in forests, the answer to this riddle is easy. No!

Without engagement, your product might as well not exist. No matter how tastefully designed or ingeniously viral, without users coming back, your app is toast.

How, then, to design for engagement? And as if that were not challenging enough, how should products that touch users across multiple devices, like smartphones, tablets, and laptops, keep people coming back?

The answer is habits. For the past several years, I have written and lectured on how products form habits, and my work has uncovered some conclusions I hope will prove helpful to product designers.

To be clear, not every product requires user habits; plenty of businesses drive traffic through emails, search engine optimization, advertising, and other means. However, if the company’s business model requires users to come back on their own accord, unprompted by calls to action, a habit must be formed.

The good news is that in today’s multi-screen world, the ability to interact with multiple devices has the potential to increase the odds of forming lasting user habits. By designing across devices, developers have a unique opportunity to leverage an ecosystem approach to drive higher engagement.

Through my research, I have found a recurring pattern endemic to these products, which I call “the Hook Model.” This simple four-phase model is intended to help designers build more engaging products.

Building for habits boils down to the four fundamental elements of the Hook: a trigger, an action, a reward, and an investment. This pattern can be found in any number of products we use automatically, almost without thinking.

Trigger

Designing for multiple interfaces means your product is more readily accessible throughout the day. The more often the user chooses a particular solution to meet her needs, the faster a habit is formed. A trigger is the event in the user’s life that prompts her to use the product.

Sometimes the trigger can be external, such as when a user receives a notification with a call to action. Other times, the trigger is internal and the information for what to do next is imprinted in the users’ memory through an association. For example, many products cue off of emotions as internal triggers. We use Facebook to socially connect with friends and family when we’re lonely and check ESPN or Pinterest when we’re bored.

It is important that companies understand the users’ internal triggers so they can build the product to meet those needs. Designers should be able to fill in the blank for the phrase, “Every time the user (______), they use my app.” The blank should be the internal trigger.

Take, for example, the experience Nike has constructed for its aspiring athlete customers. Nike’s suite of products includes wearable monitors, which track physical activity throughout the day, as well as a host of smartphone apps to be used while running, playing basketball, or golfing.

For Nike, it is critical that users attach the company’s products to a discrete moment in their lives. To succeed, Nike has to own the instant just before the user heads out the door to work out. Athletes want to know their effort matters and Nike helps them meet that need. By digitally recording the workout, Nike’s apps tap into a deeper emotional need to feel that all that sweating is not going to waste, that the amateur athlete is making progress.

By creating an association with a moment in time—in this case, every time the user exercises—Nike begins the process of creating a habit.

Action

When it comes to multi-screen experiences, it is important to design a narrative for how the product is actually used. Knowing the sequence of behaviors leading up to using the products, as well as the deeper emotional user needs, is critical for successfully executing the next step of the Hook, the action phase.

The action is the simplest behavior the user can take in anticipation of reward. Minimizing the effort to get to the payoff is a critical aspect of habit-forming design. The sooner users can get to the reward, the faster they can form automatic behaviors.

In Nike’s case, simply opening the app or wearing one of their body-mounted devices alleviates the user’s fear that the exercise will be in vain. Clicking a button marked Run in the Nike+ running app, for example, begins tracking the workout and gets the user closer to the relief he was looking for.

Finding ways to minimize the effort, be it by eliminating unnecessary logins or distracting functionality, improves the experience both on mobile and web interfaces. Nike makes the action of tracking exercise easier by building products designed to make recording even easier — for example, shoe-mounted devices that passively collect information.

Designers should consider how many steps they put in the way of users getting what they came for. The more complex the actions, the less likely users are to complete the intended behavior.

Reward

The reward phase of the Hook is where the user finally gets relief. After being triggered and taking the intended action, the user expects to have the internal trigger satisfied. If the user came to relieve boredom, she should be entertained. If the trigger was curiosity, she expects to find answers.

Thus, the reward phase gives the user what she came for, and quickly! When the athlete uses the Nike app, for example, a 3-2-1 countdown displays to signify that the workout is about to begin. The user can get on with her run, knowing it is being recorded. But the Nike suite of products layers on more rewards. The apps not only record the workout, they also motivate it.

To boost their habit-forming effects, many products utilize what psychologists call intermittent reinforcement. When products have an element of variability or surprise, they become more interesting and engaging. For example, scrolling on Twitter or Pinterest offers the allure of what might be found with the next flick of the thumb.

In Nike’s case, the element of variability can be found in various forms throughout its product experience. For example, when athletes connect to Facebook, the app posts to the social network and runners hear the sound of a cheering crowd every time one of their friends “likes” their update. The athlete never knows when they’ll hear the encouragement and the social rewards help them keep pushing forward.

Nike also implements a point system called NikeFuel, which is meant to be a quantification of physical activity. However, the mechanics of how rapidly points are earned is intentionally opaque, giving it an element of variability. Finally, exercising itself has an element of surprise, which Nike’s products accentuate by encouraging users to complete new and increasingly challenging activities.

Investment

Lastly, a critical aspect of products that keep users coming back is their ability to ask for an investment. This phase of the Hook involves inviting the user to do a bit of work to personalize the experience. By asking the user to add some effort into the app, the product increases in value with use, getting better the more the user commits to it.

Investments are actions that increase the likelihood of the next pass through the Hook by loading the next trigger, storing value, and creating preference for using the product. It is important that the four phases of the Hook are followed in sequential order for maximum impact.

Every time the user exercises with a Nike app or body monitor, she accrues a history of performance. The product becomes her digital logbook, which becomes more valuable as a way of tracking progress the more entries she makes. Additionally, each purchase of a Nike+ device—like a FuelBand, for example—is a further financial and psychological investment in the ecosystem.

Nike and other exercise training apps, like Strava, allow athletes to follow other athletes to compare performance. The action of selecting and following other users is a form of investment; it improves the product experience with use and increases the user’s likelihood of using the product again.

In the future, products like Nike+ could automatically collect information from multiple touchpoints to create an individualized workout plan. The product could improve and adapt the more the user invests in using it.

An Engagement Advantage

For multi-interface products that rely upon repeated user engagement, understanding the fundamentals of designing habits is critical. By following the Hook Model of a trigger, an action, a reward, and finally an investment, product designers can ensure they have the requisite components of a habit-forming technology.

By building products that follow users throughout their day, on smartphones, tablets, and more recently wearable devices, companies have an opportunity to cycle users through the four phases of the Hook more frequently and increase the odds of creating products people love.

Note: I will be speaking at the upcoming Habit Summit at Stanford. Blog readers get $50 off when using this link: https://habitsummit.eventbrite.com/?discount=NirAndFarFriends

Photo Credit: Robert S. Donovan