Nir Eyal's Blog, page 32

January 22, 2015

Getting Over Your Fear of Missing Out

Nir’s Note: This post is co-authored with Stuart Luman, a science, technology, and business writer who has worked at Wired Magazine, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and IBM.

“I wish that I could be like the cool kids,” goes the catchy hook for the hit song by Echosmith. The official video has been viewed over 15 million times on YouTube, perhaps tapping into something deeper than mere adolescent angst.

We all want to be like the cool kids.

In 2013, the word “FoMO” was added to the Oxford English Dictionary. The “fear of missing out” refers to the feeling of “anxiety that an exciting or interesting event may currently be happening elsewhere.” Although the terminology has only recently been added to our lexicon, experiencing FoMO is nothing new.

Most people at one time or another have been preoccupied by the idea that someone, somewhere, is having a better time, making more money, or leading a more exciting life. For those who skew towards such feelings, smartphones and social media have made it easier than ever to track what others are doing.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with wanting to keep tabs on people we care about. An important part of what makes us human is our need to be social. But recently companies have found ways to tap into this impulse to keep users coming back to their apps and websites habitually.

Whether social media induces FoMO or simply makes it easier to indulge in our feelings is up for debate. It’s not surprising that something as new and transformative as this technology would have complex implications on our daily lives, both positive and negative.

According to a 2014 study in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions, habitual Facebook users were motivated by their need to socialize and connect with others, to escape boredom, and to monitor their friends’ activities (what the authors called surveillance gratification). The study also found a correlation between depression and anxiety and higher social media usage. A 2013 study in Computers in Human Behavior featured a series of ten statements such as “I get worried when I find out my friends are having fun without me,” and asked participants to rate themselves from one to five on how well those statements correlated with their own lives. The study found that three-quarters of respondents (mostly college-age students) experienced FoMO. Those who scored higher were more likely to report lower life satisfaction and use social media immediately before and after sleeping, during meals and classes, and to engage in dangerous behaviors such as texting while driving.

Not all studies reach such negative conclusions. A 2014 study found shy and depressive individuals benefited from increased social media use and online relationships. While a 2009 study in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication found a positive correlation between college students’ use of Facebook and increased life satisfaction, civic engagement, and political participation.

It’s clear that we can’t yet fully grasp how new technologies affect our psyches. Regardless, it appears that they are here to stay. Therefore, it is up to us as users to figure out where, when, and how often to use these products and services.

Here are a few suggestions for keeping gadgets and FoMO in check.

Relish feeling out of the loop. Great things are indeed happening out there and sometimes you’re not invited. Admit that you are missing out and there’s nothing you can do about it. In fact, one approach may be to savor the fact. Blogger and entrepreneur Anil Dash wrote about the “Joy of Missing Out,” a term he coined to describe the satisfaction of doing things on his own terms. Dash learned to find pleasure in JoMO after the birth of his son when he discovered the simple joy of getting home in time to give his son a bath and put him to bed.

Take a hiatus from social media. Try staying offline for a day, a week, or maybe even a month. Examples abound of people cutting themselves off and waking up to the wonders of the real world. Steve Corona, former CTO of TwitPic, did just that in 2012. He took himself off social media for a full month. It changed his life. He read books, spent time with friends, meditated, ran three miles a day, and wrote a book. When he returned, he intentionally decided which sites he spent time on and which he didn’t.

Use software to avoid succumbing to FoMO. Apps such as Moment for iOS, BreakFree for Android, RescueTime for Windows, or SelfControl for Mac generate reports to help users see just how much time they spend online and set time limits. For those who need more radical solutions, Internet-blocking software Freedom or browser extensions such as Website Blocker or WasteNoTime block sites that cause unwanted distractions.

Delete social media apps from your mobile device. It is not as radical as quitting Facebook altogether but is a quick and relatively easy way to reduce social media use when you are away from the computer.

For those who need a full-on intervention, enroll in a digital detox camp like Camp Grounded. The camp is located two-and-a-half hours northwest of San Francisco and set on an idyllic property amid redwoods. At the camp, adults get in touch with their pre-smartphone selves by playing capture the flag, gazing at the stars, writing songs, and engaging in analog pursuits like print photography and woodworking. Rules are simple: No work talk, no watches, no outside food, no booze or drugs, and of course, no digital technology.

Clearly, what we see of others online isn’t a full representation of their lives. Instead, it’s personal social-media marketing, similar to the images of airbrushed models in fashion magazines that highlight and exaggerate only their most positive aspects. The inevitable disappointments, cringeworthy embarrassments, personal failures, and existential doubts are rarely seen in Facebook posts.

It’s also important to remember that most people experience FoMO to some degree and at some time. The uncomfortable emotion is normal and with the advent of social-sharing tools, increasingly common. However, understanding the feeling and finding positive ways to deal with it can help us be happier with our own lives without getting wrapped up in a fear that we might be missing out on what the cool kids are doing.

Photo Credit: Yaniv Golan

The post Getting Over Your Fear of Missing Out appeared first on Nir and Far.

January 12, 2015

The Limits of Loyalty: When Habits Change, You’re Toast

“I’m endlessly loyal,” my wife said, staring straight into my eyes. But she wasn’t talking about our marriage — she was pledging her allegiance to a piece of software.

“I’m endlessly loyal,” my wife said, staring straight into my eyes. But she wasn’t talking about our marriage — she was pledging her allegiance to a piece of software.

“I’ll never quit Microsoft Office,” she told me. “It does too much for me to leave it.” For a moment I wondered if her husband had engendered the same reverence, but then I remembered things at Microsoft aren’t all wine and roses. In fact, the conversation with my wife was sparked by a debate over switching from Office to Google Docs for our home business.

Apparently, we aren’t the only ones considering other options. Industry analysts say Google Apps has already beaten Office as the top choice for smaller businesses and is in a “dead heat among companies with more than 1,000 employees.”

The threat to Microsoft Office is the latest reminder of how quickly technology tides can turn. It is also a testament to the power of customer habits and what is at stake when those habits change.

Microsoft is not taking the assault lightly. The Wall Street Journal reported, “Microsoft executives are now encouraged to promote user engagement over product sales.” In a recent interview, Qi Lu, the man leading Microsoft’s Office suite of products, emphasized, “We want Office to be a habit.”

The story of how Microsoft shaped, and may eventually lose control of people’s routines, provides ample lessons for any company dependent on repeat customer engagement.

To understand what makes Office so sticky and what competitors are doing to break the habit, we need to dig deep into the psychology of our technology routines.

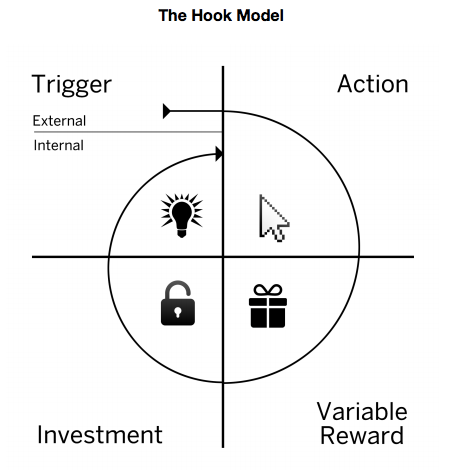

In my book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, I offer a design pattern called the “Hook Model,” to describe how products eventually become things we turn to with little thought, day after day.

Office’s user experience follows 4 discreet phases, which over time create strong behavioral impulses to use the product automatically.

Hooking Users in 4 Steps

First, there’s the Trigger phase, where the user is given an explicit cue to engage in a particular behavior. In the case of Office, the trigger might be receiving a Word, Excel or PowerPoint file sent by a colleague. To open the file, the user must of course use the software.

Over time, the new user will no longer need external triggers like an email with a file attached and will instead be cued by internal triggers — prompts to action informed by association in the user’s mind. For example, when a user turns to Office spontaneously to crunch numbers or use a word processor, the habit has taken hold. Of course, forming these associations with internal triggers is the end goal of a habit-forming product, but to get there, users must pass through successive Hook cycles.

The next step in the Hook Model is the Action phase. This step is defined as the simplest behavior in anticipation of a reward. In the case of Office, the action couldn’t be simpler — just open the file!

The Reward phase is the third step. Here, the user scratches an itch. In Office, the itch is the curiosity of knowing what is in the attachment. Opening the file provides quick relief.

The final step of the Hook is Investment phase. Here, the user puts something into the product in anticipation of a future benefit. Investments increase the likelihood of the next pass through the Hook cycle.

For example, opening, editing, and saving a file as a new version, is a small bit of work that increases the likelihood the user will return to use the software in the future. Several studies have demonstrated the powerful effect small investments have on changing user preferences. With each small investment in the product, users cement their commitment to one product over another.

One of the most powerful forms of investment is spending time to acquire new skills. When users devote time and money to learning how to use a particular software, they tacitly commit to it. The fact that there are countless books, tutorials, and courses on mastering the Office Suite is a testament to customer appetite to invest in the software.

Changing Habits

Ironically, the Investment phase is also where Office faces its greatest competitive threat. Recently, industry trends have begun to chip away at the strength of Microsoft’s hook. For one, products like Google Docs and Apple’s iWork remove a major form of investment from the equation by making the software free (at least for individual users). Second, file formats are now interoperable meaning that when a colleague sends a Word doc, that file can just as easily be opened as a Google Doc.

Finally, the skills users acquired to use Office are, for the most part, transferable to competitors’ products. Switching to the Google Doc or iWork interface is not perfectly seamless, but given these products work and look very similar to Microsoft’s, the transition is not that onerous for all but the most powerful of power-users. Some would even say competitors have bested Microsoft’s feature bloat with minimalist designs that emphasize only the most crucial functionality.

What’s more, Google’s early moves to differentiate its products by making them collaboration tools, added a new type of reward to their hook. Allowing users to work together in real-time over the web suddenly made boring enterprise software social by incorporating what I call, Rewards of the Tribe. Microsoft has taken pains to make its tools more social, but here again, old habits die hard. Whereas Google’s products are built with in-browser collaboration at their core, Microsoft’s users will have to learn new behaviors outside their existing routines.

The power of the Office hook depends on getting new users to invest in the product by learning the software, creating documents, and eventually paying for it. Microsoft’s Qi Lu acknowledged that many users, particularly younger ones, have never acquired the Office habit.

“This world is changing,” Lu said. “It’s driven by cloud and mobile devices, certainly a new generation coming to embrace those devices. They may not necessarily have been exposed (to Office).” Lu went on, “Within the next 12 months or so around the world, over two billion people will be using cloud-connected mobile devices…Those people may not necessarily have used Office before…” Though Lu views this as an opportunity, he must also know it is a daunting threat. If would-be Office users form habits with his competitors’ products instead of his, he’s sunk.

Today, several trends conspire against the Microsoft habit. Yet despite the current challenges ahead of Lu and his team, Microsoft Office sits in an enviable position. After all, Office is used by more than a billion people worldwide.

Office is the default solution people like my wife turn to. That is, until something unusual happens. Whenever the interface people use to access a technology changes — such as the shift we see now from desktop to mobile — the deck of user habits is reshuffled.

Suddenly, behaviors must be reworked for use on another interface — say on a 5-inch phone screen.

For example, while it’s my job to make a weekly trip to buy groceries for the family, my wife is responsible for making the shopping list.

In the past, she kept track of what I should buy on an Excel print-out. Recently however, she’s switched to using a mobile-optimized Google Sheet to save the list.

When it comes to even our strongest technology habits, we’ll make a change when a new interface forces us to look for new solutions. The same four basic steps of the hook — a trigger, action, reward, and investment — help us form new routines and establish new habits, no matter how endlessly loyal we think we are.

Illustration by Scott Porembski

The post The Limits of Loyalty: When Habits Change, You’re Toast appeared first on Nir and Far.

January 7, 2015

4 Ways to Use Psychology to Win Your Competition’s Customers

Let’s say you’ve built the next big thing. You’re ready to take on the world and make billions. Your product is amazing and you’re convinced you’ve bested the competition. As a point of fact, you know you offer the very best solution in your market. But here’s the rub. If your competition has established strong customer habits than you have, you’re in trouble.

The cold truth is that the better product does not necessarily win. However, there’s hope. The right strategy can crowbar the competition’s users’ habits, giving you a chance to win them over.

To understand how to change customer habits, we first need to understand what habits are and how they take hold. Simply put, habits are behaviors done with little or no conscious thought. Research shows almost half of what we do, day in and day out, is driven by these impulsive behaviors.

Consider just about any product you find yourself using without thinking and you’ll find a hook. Do you sometimes check your phone without really knowing why? Hook. Ever opened Facebook or Twitter to do just one thing only to find yourself scrolling and tapping 30 minutes later? Hook. Have you ever found yourself unable to stop playing a game like Candy Crush Saga or Angry Birds? Hook, hook, and more hooks.

Hooks have four basic parts: a trigger, action, reward and investment. User habits are valuable precisely because they do such a good job of keeping competitors out, making it exceptionally difficult for a new company to shake users from their existing routines. Here are the four ways fledgling products can win over users from the competition and successfully migrate them from one product habit to another.

1. Faster hooks.

In his book Something Really New, author Denis J. Hauptly deconstructs the process of innovation into its most fundamental steps. First, Hauptly states, understand the reason people use a product or service. Next, lay out the steps the customer must take to get the job done. Finally, once the series of tasks from intention to outcome is understood, simply start removing steps until you reach the simplest possible process.

Though it’s excruciatingly simple, understanding Hauptly’s first principles yield big results. Removing steps between the user’s recognition of a need and the satiation of that desire is at the core of all innovation, from the cotton gin to the iPhone. Products that can shuttle customers through the four steps of the hook more quickly than competitors, stand a good chance of winning them over to new routines.

For example, take the corporate collapse of Blockbuster at the hands of Netflix. Customers could watch the same movies at relatively similar prices from either movie rental company. Yet, the ease of having a film always ready to watch, versus needing to drive to a store to pick up the flick, delivered the reward faster. The ease of satiating the need and passing through the hook more quickly made all the difference. Movie enthusiasts migrated their habits to Netflix and Blockbuster subsequently filed for bankruptcy.

2. Better reward.

Our brains crave stimulation. Whenever an experience is more satisfying, more interesting, or more rewarding, we want more of it. Sometimes products establish new habits just because using them feels better.

For example, take Snapchat, the massively popular messaging app, which 77 percent of American college students say they use every day. The company is rumored to have turned down a $3 billion acquisition offer by Facebook, conceivably prompted by Mark Zuckerberg’s fear of losing his grip on college kids’ habits.

But why do so many users impulsively open Snapchat instead of Facebook? For many people, Snapchat is more rewarding. Whereas using Facebook involves scrolling through a cluttered newsfeed of ads, posts from distant acquaintances, and messages from tragically uncool relatives, Snapchat delivers pure high-octane excitement.

A defining Snapchat feature is that messages sent through the app can self-destruct — the receiver has just a few seconds to view the image before it’s gone. Facebook posts stay on the Net forever, whereas Snapchat gives users more freedom to share with, shall we say, indiscretion.

In a recent survey, 14 percent of users admitted to sexting on Snapchat. Though the study found that sharing pics of naughty bits doesn’t occur often, it is one example of what makes the app more enticing.

The ability to share spontaneous (and often embarrassing) images without fear they’ll linger on the web generates more interesting messages for the receiver and therefore increases the likelihood of using the app. If a user was to receive two messages simultaneously, one a message on Facebook and the other on Snapchat, it’s the more rewarding app that gets clicked.

3. Higher frequency.

Studies show behaviors done more often have a higher habit-forming potential while those done less often do not usually become routines. When it comes to pulling users away from their existing habits, products that can engage users more frequently than their competitors, have a better shot at bringing users back.

Every few years, a new way of engaging customers becomes possible. What I call an “interface change,” reshuffles the deck of user behavior and creates new opportunities to form habits. For example, successive interface changes occurred with adoption of the personal computer, then widespread Internet connectivity, then mobile devices, and now the coming of wearables. Each created an opportunity to shift customer behavior out of existing routines and into new, more frequently used interfaces.

When Amazon first began selling books online in the 1990s, it made shopping a more frequent behavior by putting the store inside the customer’s home via the Internet. Today, Amazon has become the world’s “everything store” and threatens all offline retailers with the ease and convenience of shopping for whatever whenever. In many households, dropping an item into their Amazon cart is something done nearly every day.

4. Easier in.

A characteristic of many habit-forming products is that they are easy to start and hard to stop. By breaking down some barrier to begin using the product, companies have found success wooing users away from competitors.

For example, though Microsoft Office is still the world’s most popular productivity software, the suite has come under attack by rivals such as Google and Apple who each removed a major barrier to start using their software by making it free and easy to use. When Google Docs first launched, it provided a fraction of the functionality offered by Office. But at the time using Office required downloading and paying for the software while Google Docs provided immediate entry.

Over time, learning how to use Google Docs, creating new files and inviting others to share those documents online, all made leaving difficult. The more the product was used, the more the habit took hold.

The Monopoly in the mind

Habit-forming products utilize four strategies to get inside users’ heads. By shuttling users through the four steps of the hook faster, better, more frequently, or by making it easier to start using the product in the first place, companies can wrestle user habits away from incumbent competitors.

The post 4 Ways to Use Psychology to Win Your Competition’s Customers appeared first on Nir and Far.

December 22, 2014

Email Habits: How to Use Psychology to Regain Control

I don’t usually write about personal and revealing matters, but recently I’ve noticed something I don’t like about myself–I check email too often.

I don’t usually write about personal and revealing matters, but recently I’ve noticed something I don’t like about myself–I check email too often.

This confession doesn’t come easily, because, ironically, I am the author of a book titled Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. It is a guidebook for designing technology people can’t put down. There’s just one problem–I can’t put my technology down.

I ritually check email when I wake up in the morning. If I’m out to lunch, I’ll sneak a peek on my way to the restroom. I even look at my email when stopped at a red light. Most troubling, I catch myself emailing instead of being fully present with the people I love most. My daughter recently caught me scrolling on my iPhone and asked, “Daddy, why are you on your phone so much?” I didn’t have a good answer.

I wish I could say I’m in full control of my habits, but I’m not. Although I know exactly why digital gadgets hook us (I wrote a book on it, after all), that hasn’t stopped me from overusing. It’s not that email is bad per se; it’s a tool like any other. Rather, I’ve recently noticed that how and when I use this tool is hurting me instead of helping, and I’ve decided something needs to change.

Of course, you pick your compulsion. What one person finds engrossing is utterly boring to someone else. Video games, spectator sports, social media, television, and email compel some and repel others. So it is.

Not everyone struggles with email like I do, but my hope is that I can share some generalizable lessons. Here are a few ways I’m tackling my problem, using what I know about the psychology of habits.

Getting unhooked

In my book, Hooked, I describe how products form habits–behaviors done with little or no conscious thought. The impulse to use these products attaches to what I call an internal trigger. Internal triggers are cues informed by mental associations and memories. Certain places, situations, routines, and most frequently, uncomfortable emotions all act as internal triggers. When we’re lonely, we check Facebook. When we’re uncertain, we Google. And when we’re bored, we check YouTube, sports scores, Pinterest, or any number of other digital distractions.

In my case, my unconscious email checking coincides with a particularly uncomfortable sensation. The urge to check is hardest to resist whenever I feel I should be elsewhere.

This cognitive itch comes in barely perceptible waves of anxiety prompted by unanswered questions. Is there something important waiting for me in my inbox? Perhaps good news? Perhaps bad? Maybe a quick response would scratch the itch to check? Even as I write this I feel the urge to check email.

The holidays didn’t help. The extended time away from work meant emails piled up unanswered. Furthermore, the potent mix of uncomfortable small talk with rarely seen relatives created a cocktail of dull disquietude. I felt the urge to check as kin grasped for something to say between the forced smiles, sips of wine, and shuffling feet.

While older members of the clan plugged the awkward pauses in conversation by bringing cocktail glasses to lips, the 20-somethings planted screens to faces. I realized we were all conceivably using our booze and our phones for the same reason–a brief escape from a restless reality.

Recognizing the internal trigger prompting the habit helped me confront the urge. Although I haven’t quite figured out what to do with the social anxiety and need to escape quite yet, I’m attempting to become more aware of it. Simply acknowledging the sensation can be a way of disarming the power of the trigger.

Burying the triggers

I having been looking for practical ways to put my mind at ease. For one, I have designated time on my calendar for email. I now schedule a daily meeting with my inbox, as opposed to letting messages barge into my life throughout the day. When I feel the need to check, I remind myself I’ll get to it soon and that there’s an apportioned time for it.

While internal triggers cue behaviors through mental associations, there is another type of trigger I have to deal with if I want to break the habit. External triggers prompt action by telling the user what to do next. The notifications, icons, and buttons we see throughout our day tell us to check, open, and respond. Sometimes these notifications are helpful, other times they are not. These digital tidbits can needlessly distract us.

I knew what I had to do–remove the external triggers prompting me to check email. However, actually doing what I knew had to be done was harder than I expected.

I’d stopped charging my phone by my bed for some time, so that was no longer a problem. But to go a step further, I turned off email notifications on my phone. Not seeing the red jewel hovering over the Gmail app icon on my phone would reduce the temptation, or so I thought.

Unfortunately, that idea backfired. The app icon was still on the home screen, implicitly telling me what to do every time I used my phone. “Open me! I have something special for you!” it seemed to scream.

Although I can’t kill the email app on my iPhone completely (Apple doesn’t allow it), I did the next best thing. I buried it.

Dr. BJ Fogg of Stanford’s Persuasive Technology Lab posits that making a behavior harder to do makes it less likely to occur. I looked for ways to make opening email more difficult. Surprisingly, I found just adding a few extra steps makes me less likely to check my email.

By moving the email icon to the second page of a nested group, opening the app requires a bit more effort. Opposed to the one tap needed to open it before, now I need to open the group, swipe to the right, and tap on the app. Remarkably, adding just two more steps actually makes a difference. Not only is Gmail no longer staring me in the face every time I check my phone, but the extra steps give me a bit more time to think about whether opening email is really necessary at that moment.

Ebbing the flow

Finally, I looked for ways to reduce the number of incoming messages. The fewer messages that come in, the less tempted I am to respond.

First, I turned on my email’s vacation responder so that everyone who emails me receives an automatic reply, even when I’m not on vacation. My immediate return message includes a list of answers to questions I frequently receive. For example, I discovered that a sizable chunk of emails are from readers and entrepreneurs who’d like to know how to schedule time to talk with me. Instead of attempting to slog through the dozens of email volleys, I provide a link to an online calendar anyone can use to schedule time with me.

The robo responder helps reduce email volume by directing people with appropriate information, as well as reducing the inevitable email flurry that follows a subject line such as, “Time to chat?”

A work in progress

This is uncharted territory for me. I usually stick to teaching businesses how to make their products stickier, and since most companies struggle with customer engagement, my work has been eagerly received. However, in this case, I want to be free of the urge to overuse technology.

When it comes to wrestling back control over digital devices, I admit I don’t have all the answers (yet). What I do know is that I’d like to change this aspect of my life. Figuring out when, where, and how to use technology is still an open question, both personally and societally. What we all want is to control our habits, rather than allow them to control us.

How about you? Have you struggled with bad habits, tech related or otherwise? How have you regained control? Give me some tips in the comments section below.

Photo Credit: Jay Watson (he's awesome!)

The post Email Habits: How to Use Psychology to Regain Control appeared first on Nir and Far.

December 11, 2014

The Real Reason “Stupid” Startups Raise So Much Money

Have you noticed all the startups raising massive sums of money recently? Perhaps you’ve scratched your head wondering how a company like Buzzfeed, known for its website full of animated gifs, listicles and quizzes, just raised $50 million dollars, valuing the company at a reported $850 million. Snapchat, the messaging app known for helping teenagers sext one another, reportedly received a $10 billion valuation from its investors. Has the world gone mad?

Some industry watchers see the recent boom in seemingly trivial apps and websites as foretelling tech bubble 2.0. However, there’s much more to the story.

Our knee-jerk reaction to classify innovation as either important or frivolous is exactly why many are left aghast when previously dismissed companies reveal shocking valuations in ridiculous investment rounds.

Vitamins and Painkillers

Most people, including many professional investors, tend to put new products into one of two categories: vitamins or painkillers.

Painkillers tackle important problems. They solve an obvious need, relieving a customer’s specific pain and address a quantifiable market. Think Tylenol, the brand name version of acetaminophen, and the product’s promise of reliable relief. It’s the kind of ready-made solution for which people are happy to pay.

Innovators in companies big and small are constantly asked to prove their idea is important enough to merit the time and money needed to build it. Gatekeepers such as division heads and managers want to invest in solving real problems — or, meeting immediate needs — by backing painkillers.

In contrast, vitamins do not necessarily solve an obvious pain-point. Instead they appeal to users’ emotional rather than functional needs. When we take our multivitamin each morning, we don’t really know if it is actually making us healthier. Efficacy is not why we take vitamins. Taking a vitamin is a “check it off your list” behavior we measure in terms of psychological, rather than physical, relief. We feel satisfied that we are doing something good for our bodies — even if we can’t tell how much good it is actually doing us.

Unlike a painkiller, which we can not function without, missing a few days of vitamin popping, say while on vacation, is no big deal. Likewise, people tend to dismiss innovations like Buzzfeed as vitamins believing it’s a nice-to-have product, not a must-have — and for the most part, they’re right.

However, what we often fail to realize is that over time, vitamins can become painkillers. As Buzzfeed investor Chris Dixon wrote, “the next big thing will start out looking like a toy.”

Becoming a Habit

Let’s consider a few of today’s hottest consumer technology products — say Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest. What are they selling — vitamins or painkillers?

Most people would guess vitamins, thinking users aren’t doing much of anything important other than perhaps seeking a quick boost of social validation. Before making up your mind on the vitamin or painkiller debate for some of the world’s most successful tech companies, consider this idea: A habit is when not doing a behavior causes a bit of pain.

Think back to before you first started using these services. No one ever woke up in the middle of the night screaming, “I need something to help me update my status!” Like so many innovations, people did not know they needed Facebook until it became part of their everyday lives — until it became a habit.

It is important to clarify that the term “pain point,” as it is frequently used in business school and marketing books, is somewhat hyperbolic. In reality, the experience we are talking about is more similar to an “itch,” a feeling that manifests within the mind and causes discomfort until it is satisfied. The habit-forming products we use are simply there to provide some sort of relief. Using a technology or product to scratch the itch provides faster satisfaction than ignoring it. Once we come to depend on a tool, nothing else will do.

Seeking pleasure and avoiding pain are two key motivators in all species. When we feel discomfort, we seek to escape the uncomfortable sensation. Over time, the solution to the user’s pain is found in the product’s use.

Habit-forming technologies seem, at first, to be offering nice-to-have vitamins, but once the habit is established, they provide an ongoing pain remedy. It is easy to dismiss these seemingly frivolous technologies when we don’t understand the deeper psychology compelling users to come back again and again.

This essay is an adapted excerpt from my book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products .

The post The Real Reason “Stupid” Startups Raise So Much Money appeared first on Nir and Far.

December 4, 2014

The Psychology Behind Why We Can’t Stop Messaging

Today, there’s an app for just about everything. With all the amazing things our smartphones can do, there is one thing that hasn’t changed since the phone was first developed. No matter how advanced phones become, they are still communication devices — they connect people together.

Though I can’t remember the last time I actually talked to another person live on the phone, I text, email, Tweet, Skype and video message throughout my day. The “job-to-be-done” hasn’t changed — the phone still helps us communicate with people we care about — rather, the interface has evolved to provide options for sending the right message in the right format at the right time.

Clearly, we’re a social species and these tech solutions help us re-create the tribal connection we seek. However, there are other more hidden reasons why messaging services keep us checking, pecking, and duckface posing.

In my book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, I detail a pattern found in products we can’t seem to put down. Though the pattern is found in all sorts of products, successful messaging services are particularly good at deploying the four steps I call, “the Hook,” to keep users coming back.

The Hook is composed of a trigger, action, variable reward, and investment. By understanding these four basic steps, businesses can build better products and services, and consumers can understand the hidden psychology behind our daily technology habits.

The Hook Model

Trigger

A trigger is what cues a habit. Whether in the form of an external trigger that tells users what to do next (such as a “click here” button) or an internal trigger (such as an emotion or routine), a trigger must be present for a habitual behavior to occur.

Over time, users form associations with internal triggers so that no external prompting is needed — they come back on their own out of habit. For example, when we’re lonely, we check Facebook. When we fear losing a moment, we capture it with Instagram. These situations and emotions don’t provide any explicit information for what solution solves our needs, rather we eventually form strong connections with products that scratch our emotional itch.

By passing through the four steps of the Hook, users form associations with internal triggers. However, before the habit is formed, companies use external prompts to get users to act. For messaging services, the external trigger is clear. Whenever a friend sends a message via WhatsApp, for example, you see a notification telling you to open the app to check the message.

WhatsApp’s External Trigger

Action

Notifications prompt users to act, in this case tapping the app. The action phase of the Hook is defined as the simplest behavior done in anticipation of a reward. Simply clicking on the app icon opens the messaging app and the message is read.

When the habit forms, users will take this simple action spontaneously to alleviate a feeling, such as the pang of boredom or missing someone special. Opening the app gives the user what they came for — a bit of relief obtained in the easiest way possible.

Variable Reward

The next step of the Hook is the variable rewards phase. This is when users get what they came for and yet are left wanting more.

This phase of the Hook utilizes the classic work of BF Skinner who published his research on intermittent reinforcement. Skinner found that when rewards were given variably, the action preceding the reward occurred more frequently. When forming a new habit, products that incorporate a bit of mystery have an easier time getting us hooked.

For example, Snapchat, the massively popular messaging app that 77% of American college students say they use every day, incorporates all sorts of variable rewards that spike curiosity and interest. The ease of sending selfies that the sender believes will self-destruct makes sending more, shall we say, “interesting,” pics possible. The payoff of opening the app is seeing what’s been sent. As is the case with many successful communication services, the variability is in the message itself — novelty keeps us tapping.

You never know what you’ll see when you open Snapchat

Investment

The final phase of the Hook prompts the user to put something into the service to increase the likelihood of using the service in the future. For example, when users add friends, set preferences, or create content they want to save, they are storing value in the platform. Storing value in a service increases its worth the more users engage with it, making it better with use.

Investments also increase the likelihood of users returning by getting them to load the next trigger. For example, sending a message prompts someone else to reply. Once you get the reply, a notification appears and you’ll likely click through the Hook again.

Growing a “buddylist” on Snapchat is an investment in the platform

Through frequent passes through the Hook, user preferences are shaped, tastes are formed, and habits take hold. Messaging services are here to stay and we’ll most likely see many more iterations on the theme as technological solutions find new ways to bring people together. By understanding the deeper psychology of what makes us click by knowing what makes us tick, we can build better products and ultimately live better lives.

November 25, 2014

The Psychology of a Billion-Dollar Enterprise App: Why is Slack so Habit-Forming?

Slack isn’t just another office collaboration app. The company has been called, “the fastest-growing workplace software ever.” Recent press reports claim that “users send more than 25 million messages each week,” and that the company is, “adding $1 million to its annual billing projections every six weeks.” Smelling an opportunity, investors just plowed $120 million into the company, giving it a $1.12 billion valuation.

Slack isn’t just another office collaboration app. The company has been called, “the fastest-growing workplace software ever.” Recent press reports claim that “users send more than 25 million messages each week,” and that the company is, “adding $1 million to its annual billing projections every six weeks.” Smelling an opportunity, investors just plowed $120 million into the company, giving it a $1.12 billion valuation.

“Our subscription revenue is growing about 8 percent monthly, before we add new sales,” says Slack’s business analytics lead Josh Pritchard. “This is, as far as I know, unheard for an enterprise SaaS company less than seven months after launch.”

Perhaps even more surprising, Slack’s user retention stands at an astonishing 93 percent. How does Slack get its users hooked?

On the surface, no single factor seems to set Slack apart from a plethora of other collaboration tools. However, a closer look using the model described the book Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Product, reveals the user psychology behind the company’s success.

A habit is an impulse to take an action automatically, with little or no conscious thought. Slack’s ability to quickly form a habit could be the key to the company’s tremendous customer loyalty and high engagement.

Slack leads users repeatedly through a cycle called a “hook.” The four steps of the hook include a trigger, action, reward, and investment, and through successive passes through these hooks, the new habit is formed.

The Slack Habit

The Slack team understood that it is much easier to displace an existing habit than to create an entirely new one. Slack doesn’t try to radically change user behavior. Instead, it makes existing behaviors easier and more efficient.

Slack also meets one of the most important prerequisites required to form a new habit: the key behavior occurs frequently. The company says the average Slack user sends 40 messages a day. Habituated users send twice as many.

Slack’s Triggers

A trigger is a cue to action. Users keep Slack open all day on a variety of devices and receiving a notification prompts opening Slack. Pritchard says, “It becomes a way of saying to your co-workers ‘I am at work and I am available.’” The company has focused on making Slack easy to use when on the go. Slack user James Gill said, “I personally have found myself catching-up on things much more from my phone now than I ever did before.”

Though Slack clearly utilizes effective triggers in its own product to get users checking the app, don’t all those notifications overwhelm people? How can a company with the slogan, “Be less busy,” avoid perpetuating mindless multi-tasking with each new ping? The key appears to be how Slack helps workers avoid other distractions.

Teams often use multiple tools in their work — Asana for project management, Github for version control, and Dropbox for files — all the while receiving notifications and reminders from those tools via email. However, all these messages and notifications can clutter a worker’s day, especially when they are received and processed in the same email inbox they use for all their other messages. Combined with all the interoffice chatter we send back and forth through email and we soon find ourselves in the email deluge we swim in today.

Slack provides shelter from the storm. By offering a centralized hub for team communications, including the information streaming in from work-related tools, professionals reduce distraction from the irrelevant messages bombarding their email inbox throughout the day. “Anything in Slack is internal,” says Slack user Jamie Lawrence. “Anything in my inbox should be external.” Slack acts as a protective shield focusing user’s attention on what’s important by reducing irrelevant triggers.

Slack’s Action and Rewards

By focusing on only the triggers that matter and by making it easier for users to respond through any number of devices, Slack increases the likelihood of the user taking the key action — opening the app.

The next step in Slack’s hook is the reward. Slack taps into team members’ need to feel included as well as their fear of missing out on important work-related information. Like any number of social media sites, Slack provides variable rewards to its users in the form of new tidbits of information or approval from their peers, which arrive at unpredictable intervals. Intermittent rewards are endemic to all sorts of habit-forming products. In fact, Pritchard says the product reminds him of his former employer, “My time at Slack is definitely … reminiscent of early Facebook,” he says.

Investing in Slack

The final step of the hook is the investment. Here, users put in a bit of work into the product to make it more useful and therefore increase the likelihood of using it in the future. Users invest in Slack in multiple ways: inviting colleagues, sending messages (which then become part of the searchable archive), adding integrations with external tools, and of course, eventually paying for the service.

Slack understands the power of getting users to invest. In fact, whereas most enterprise tools offer limited features during free trial periods, Slack holds almost nothing back. The company wants to maximize usage and and therefore opportunities to form the Slack habit. The only difference between Slack’s free and paid version is the quantity of messages that can be searched and the number of external tools which can be connected. By the time companies need this functionality, their teams are already hooked.

Habit-forming products make it as easy as possible to invest. Persuading users to pay, for example, is often a challenge for a previously free tool. However, Slack found a way to overcome some users objections to ponying-up. Pritchard said, “teams will not be charged for inactive users. This seems to significantly reduce the cognitive friction in the purchase process.” Slack’s 30 percent conversion rate from free to paid customers is one of the highest in the enterprise business.

Slack makes the path from new to habituated user as smooth and as swift as possible. It effectively triggers checking the app, delivers immediate social and information rewards on an intermittent basis, and prompts users to invest by adding colleagues, content and eventually cash.

Nir’s note: This post was co-authored with Ciara Byrne, a technology journalist whose work has appeared in Fast Company, Forbes, VentureBeat and The New York Times Digital.

Photo Credit: Zuerichs Strassen

November 17, 2014

Mind Hacking a Book

HOOKED debuts on the WSJ bestseller list.

“Hi Nir,” the email began. “I have been reading your work and find it incredibly interesting.” Naturally, this is the kind of message a blogger loves to receive. However, this email was special for another reason. It was from a prominent New York publishing agent who represents several authors I read and admire. “I don’t know if you’ve already started down this road or whether writing a book interests you, but I’d be delighted to have a conversation with you if you are interested.”

Was she kidding? Heck yeah I was interested!

We scheduled a time to talk. She told me she is fond of my work and thought it could reach a larger audience if it was promoted by a major publisher. That email and the subsequent call would lead to the release of my book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, which just debuted on the Wall Street Journal bestseller list this week.

I should mention that the focus of my research for the past several years — and the topic of my book — is mind hacking. I study the psychology of how products change human behavior. Given my knowledge of the subject, I’d be foolish not to use what I teach others. Here are three surprising techniques I utilized to write my book and a few tips from some very successful friends.

Write What You Want to Know

When Daniel Pink began working on his mega-hit book, Drive, he knew relatively little about the subject he was going to write about. What he did know for certain was that his curiosity was not yet satisfied. Pink told me he knew “enough to realize that the science of motivation was utterly interesting but woefully under-covered.” Interestingly, the more Pink learned, the more things fit into place. Today, Pink is an expert in his own right.

Curiosity is author rocket fuel. In my own book, I describe the psychological power of variable rewards. Receiving positive reinforcement at variable intervals — that is, not knowing when the good stuff is coming — has been shown to spike dopamine levels in the reward centers of the brain. It is a major reason why all sorts of experiences like video games, slot machines, action movies, and even our cell phones, keep us so engaged. For authors, searching for the answers we seek can be just as engrossing. The unpredictable nature of the hunt for knowledge can provide endless motivation for those able to harness it.

As Pink told me, “The big motivator for good books is the author’s own curiosity. If I’m not curious about a topic, why should I expect any reader to be?” Leveraging the variable reward of pursuing answers to one’s own burning questions is one of the best mind hacks I know.

Get Frequent Feedback

Many would-be authors believe they have to know all the answers before they start writing. Whether it’s a full volume book or a 500 word blog post, people tend to not start until they have all the pieces of the puzzle figured out. Generally, this leads no where. Far too many people who have important things to share never publish because they fail to take the first step.

When New York Times bestselling author Gretchen Rubin began working on her forthcoming book, Better Than Before, she admits that like Pink, she didn’t have all the answers. “If I have what I think is a good idea, I want to get it out into the world,” Rubin told me. “I don’t hold ideas back.” Despite knowing her ideas were only half-baked, Rubin began putting her thoughts and theories out into the world via her blog because, she says, “I learn more about them as I write about them and also because my creativity is more stimulated by throwing ideas out there … Often I will write a post about a new idea to see what responses it evokes.”

In my own book, I detail the psychology behind taking action. Psychologists have known for years that when a behavior is difficult to do, we need more motivation and willpower to do it. For many people, the burden of needing to have all the answers before writing, make the book writing journey too difficult to start. Instead, breaking down the process into small iterative steps can reshape and improve the work. Publishing small posts frequently with the intention of testing new ideas with readers not only provides a constant stream of critical feedback but also supplies a kind of intoxicating encouragement that can push an author forward.

Help Your Readers Invest in Your Work

Like Gretchen, the content of my book started as blog posts. After I had published my thoughts for several years, I began to see common themes emerge. I turned my posts into a series of lectures I later taught at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. As my blog readership grew, I received a few emails asking when I’d write a book. One of those messages came from Ryan Hoover who offered to help arrange my essays into a book format. Ryan’s work also helped identify holes in the text where I needed to do more research and writing.

When I had completed a rough draft, I decided to ask my blog followers for help and did something most authors would think is nuts — I placed the full text of the book online. Certainly, some people may think giving the entire world access to an unpublished book is crazy. However, the response was tremendous and the experience taught me something profound. By letting people make suggestions and improvements, readers were also investing in the book with their time and effort.

Psychologists have studied the powerful influence small investments can have on the way we think and act. Several studies have demonstrated that putting effort into an activity makes us more committed to it. A happy by-product of asking my readers for help editing my book is that I now have a team of advocates ready to tell others about the book they helped create. I also made sure to list the names of everyone who helped in a special contributor section in the book.

When I received my literary agent’s email asking if I was interested in publishing a book, I was ready. I had put the psychological principles featured in my book to good use. By following my own curiosity, getting frequent feedback and asking my readers to invest in the text, I was in a great position to take my book to stores and eventually readers’ hands.

I am extremely grateful for the interest and support of my early readers. Hooked is for you and in many ways by you. Thank you!

November 10, 2014

Framing Reward is as Important as Reward Itself

On May 1, 1981, American Airlines launched its frequent flyer program AAdvantage. Since then, a flood of loyalty programs have attempted to bring customers back through rewards.

On May 1, 1981, American Airlines launched its frequent flyer program AAdvantage. Since then, a flood of loyalty programs have attempted to bring customers back through rewards.

Today, you can become a card-carrying member of just about anything: hotels, supermarkets, drugstores and pizza chains. If you’re in a store, chances are someone will ask, “Would you like to join our rewards program?”

Marketing professors, store managers and executives are still not sure how effective these initiatives are. One puzzle is the link between participation and loyalty. It’s not that strong. Millions of Americans are enrolled in at least one loyalty program, but just a fraction of them are dedicated customers. Typically, loyalty programs work only to the extent that they reward customers who are already loyal.

Another part of the mystery is the reward itself. Most loyalty programs offer additional perks to create a positive feedback loop — the more we shop in one store, the more we get in return, the less we’ll shop in another store. But in a world saturated with offers, it’s difficult to turn a reward into a habit.

Here’s one idea. Instead of asking, “What rewards should we give away?” ask “How should we give away a reward?” It might not be the reward per se, but how the reward is framed, and the steps customers must take to obtain the reward, that matters.

How to Frame a Reward

In 2004, marketing researchers Joseph Nunes and Xavier Dreze teamed with a local car wash in a busy metropolitan area. For one month, the researchers handed out loyalty stamp cards every Saturday. They used two different cards depending on the week. Customers on the first and fourth week received a card with an offer to “buy eight car washes and get the ninth one free.” The second group of customers received a card with a slightly different offer. They were awarded one free wash for every ten purchases, but they were also gifted two free credits.

In absolute terms, each deal was the same. Eight trips to the car wash earned one free wash. Yet twice as many people in the second condition completed the stamp card; having earned two credits, the feeling of progress nudged them to return. Nunes and Dreze term this tendency the endowed progress effect: We’re more committed to completing a goal when we have made some progress.

How to Frame Progress

PayPal illustrates how complete my profile is with an easy-to-digest visual. By highlighting the progress I’ve already made — even though the “progress” is the mere act of signing up — I’m motivated to give them my phone number. No turning back now; I’m already 80 percent of the way there.

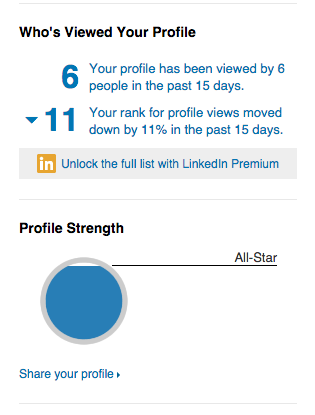

LinkedIn, where I can gauge my “profile strength,” is similar. My profile is nearly finished — but not quite — a compelling reason to “strengthen it.” Yet LinkedIn is more sophisticated than PayPal. It informs me that six people have viewed my profile in the past 15 days adding an element of social pressure. Notice the copy underneath this notification: “Your rank for profile views improved by 11 percent in the past 15 days.” With the feeling of progress, I’m more likely to click on the aptly placed “LinkedIn Premium” offer.

Candy Crush Saga, an addictive puzzle app, is different from PayPal and LinkedIn but employs a similar tactic to keep users engaged. If a user does not complete a level in the given number of turns, the game offers bonus items like “lollipop hammers,” “disco balls,” and more turns. However, there’s a price for the virtual goodies. Users must pay real money for a better shot at finishing the level.

It’s unlikely players would agree to pay at the beginning of a level. However, after spending time and energy, it’s a different story. Given the chance to beat that level you’ve been stuck on, these offers are much more appealing. What’s true of Candy Crush Saga is true of other popular games and platforms — they convert the users’ investment of time into money.

Framing as a Tool to Create Habits

An important step in creating routines is the gap between variable reward and investment. Variable rewards (new tweets, specials at the restaurant, deals at a retail outlet) keep us coming back for more, but they don’t necessarily lead to investment unless the product is designed to get the user to, “put something of value into the service.”

The variable reward on LinkedIn, for example, is the newsfeed and the notifications. Investment occurs when the user updates his profile, makes connections, and purchases LinkedIn Premium.

Smart framing can convince users to invest further in the experience, making it more likely they will return. It’s a subtle but psychologically powerful maneuver. Instead of trying to persuade customers to invest in a product or service, why not show them they’ve already invested?

Loyalty programs, in contrast, typically attract customers by offering better prices or superior products: ”Spend $100 and get $10 off!” or “Become a Platinum Elite member and get free upgrades!” are two familiar examples. Yet focusing on what a customer can acquire, instead of the time and money they’ve already spent, could be one reason these programs are ineffective. The trick is not strengthening the link between use and loyalty with better deals. It’s reinforcing the perceived relationship between use and loyalty. That starts with smart framing.

Nir’s Note: This post was co-authored with Sam McNerney, a freelance writer who focuses on psychology and business.

Photo credit: opensourceway

November 5, 2014

Why I Wrote “Hooked”

More than a year and a half ago, with the dedicated help of Ryan Hoover, I started working on my book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

More than a year and a half ago, with the dedicated help of Ryan Hoover, I started working on my book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

Hooked compiled 2 years of writing and research (and many more years of professional experience) into a guide to help people like you design engaging products that have a positive impact on users’ lives.

Today, I’m thrilled to announce that Hooked is available in a new professionally published edition. The book looks and feels much better than the previous self-published edition and as a special offer to my readers I’ve created special bonus content to help you build more impactful products and better personal habits.

The bonus bundle contains content not found in Hooked, including:

A 10-part video interview with me on designing for user engagement.

The Hooked workbook — a step-by-step companion to the book.

10 videos from the 2014 Habit Summit at Stanford featuring luminaries from Facebook, Airbnb, Expedia and more, revealing how they build habit-forming products.

The Traction workbook for finding new potential customers and growing your business.

An ebook by James Clear on mastering your personal habits.

.. and more!

The content is clearly worth a ton, but that’s not the point. What I really want is to give you the best possible chance at building something great. That’s why I am giving away the entire bundle for free to anyone who orders Hooked by this Saturday, November 8th.

Amazon and Barnes & Noble are heavily discounting the book right now so it’s certainly worth a look.

After getting the book, go to: hookmodel.com/#special-offer to claim your free bonus content immediately.

PS – As an added bonus … to support local book stores, I’ll send you a personally signed book plate for your copy of Hooked as an added thank you for buying from your local book seller (US only). Just email me a picture of your receipt before Saturday. To find your local book store, go to: http://www.indiebound.org/indie-store-finder or click below: