Richard Conniff's Blog, page 72

June 24, 2013

Buying Endangered Species for the Kids

There’s always been a kind of zen, a sense of serenity and connection to nature, about watching ornamental fish. That’s one reason more than 10 percent of American households keep fish tanks, ranging from goldfish bowls to vast, meticulously maintained saltwater ecosystems. But according to a new study in the journal Biological Conservation, this popular hobby may be causing some of the most beautiful species on Earth to become extinct.

The study looks at the trade from just one country, India, from 2005 to 2012, and it reports that dealers there exported 1.5 million freshwater fish in at least 30 threatened species, including a dozen that are endangered.Just within the red Lined torpedo barbs, a colorful species complex, more than 300,000 individual fish were shipped to the United States and a half-dozen other countries.

Dealers probably took many times that number from the wild, the study suggests, counting those that died before they could be exported. Uncontrolled harvesting of these charismatic fish “during the last two decades is associated with severe population declines, and an ‘Endangered’ listing” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (The IUCN is the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.)

Part of the problem with the trade has to do with limited or misguided regulation in India. When the Department of Fisheries in the southern Indian state of Kerala set out in 2008 to control the trade in red Lined torpedo barbs, the new study reports, it did so with little scientific advice. So it closed the trade in June, July and October, to allow the fish time to breed in peace. But these species actually breed … to read the rest of this story, click here.

June 13, 2013

An Obituary for My Dad

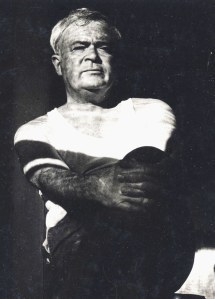

J.C.G. Conniff, c. 1971 (Photo: Richard Conniff)

James C. G. Conniff, an author and writing professor, died Saturday at his home in Montclair, N.J. He was 92.

At St. Peter’s College in Jersey City, he taught the craft and love of writing to generations of students, many of whom went on to become writers themselves. Even decades later, they often sent letters celebrating “the legendary two-middle-initialed James C.G. Conniff,” as one of them put it.

“He was the best English teacher I ever had–tough, demanding, and inspirational,” one student recalled. Many former students remembered Conniff’s practice of requiring freshmen students to memorize great poems, and they wrote that even decades later the lines of “Lycidas” or “Ode to Autumn” still came to mind.

“No matter where I worked,” wrote another, “I always carried the legacy of an incorrigibly intense Irishman with a Caesar haircut and a quick-triggered impatience for cant. His passion about writing well—and his intolerance for lousy writing—challenges me to this day. Although I’ve forgotten everything I learned about classical Greece, for example, I still remember the Greek word for excrement. He sometimes wrote that word in the margin of a rushed or carelessly written assignment I submitted that had earned his unique displeasure.”

Conniff, who grew up in Woodlawn section of the Bronx, was the author of seven books, including Governor Al Smith, a biography of the first Catholic presidential candidate. He wrote for The Saturday Evening Post, Sports Illustrated, and many other magazines.

The Congressional Record credited one of his articles with helping win the first federal funding for research into the causes of Down syndrome. Another of his articles won the American Heart Association’s Howard W. Blakeslee Award for distinguished reporting on stroke prevention. With then-U.S. Congressman Peter W. Rodino, Jr., he successfully campaigned in 1982 for a U.S. first class postage stamp honoring Francis of Assisi on the 800th anniversary of his birth.

In one widely-noted article in the New York Times magazine, Conniff wrote about the decision with his wife Dorothy to raise a Down syndrome child at home with their other children, at a time when institutionalization was standard. He noted the difficulty of seeing Mark as an adult struggling “in a family of writers, to produce copy. Pages of hand-scrawled and sometimes typed letters, all higgledy-piggledy, spill from his fevered efforts to ‘follow in your footsteps, Dad!’” But Conniff also wrote: “For 31 years, Mark has been a central fact of our family life, knitting us together, trying our patience, helping us laugh, probably making us better people than we would have been without him.”

In recent years, Conniff has actively supported Mark’s annual walk-a-thon to raise funds for ARC-Essex, an organization devoted to helping developmentally-challenged women and men become independent members of their communities. This year, the two men together raised more than $6000.

Conniff’s other great cause in recent years has been the preservation of Montclair’s special character. He fought unsuccessfully against the demolition of the Marlboro Inn, and earlier this year against the demolition by Montclair Kimberly Academy of a house on Upper Mountain Avenue that had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. He also campaigned to ensure continued funding for the local library at a time when the town had proposed turning the Andrew Carnegie-endowed Bellevue Avenue branch over to developers.

Conniff’s wife Dorothy died in 1999. He leaves his sister Julia Demarski, daughters Susan Manney, Deborah Suta, and Cynthia Cavnar, sons Gregory, Richard, and Mark Conniff; 12 grandchildren, and 9 great-grandchildren. Visiting hours Fri. 2-4 p.m., 7-9 p.m. at the Moriarty Funeral Home in Montclair. Funeral mass 10 a.m. Saturday at St. Cassian’s. In lieu of flowers, please consider donations to Arc of Essex, 123 Naylon Ave., Livingston, NJ 07039 or Lamp for Haiti Foundation, P.O. Box 39703, Philadelphia, PA 19106.

June 10, 2013

Tinkering and Puttering

This is a story I wrote about working with my father. It ran in the New York Times magazine in 1985:

I stand before you today to confess that I honestly like the pastime known, God help me, as home repairs. I like the perfect dimple my hammer leaves in wallboard when I drive home a nail. I like the drifts of sawdust across the floor and the curlings of wood when I plane down a door. I even like the language of home repairs, with its blind nailing of floorboards and floating of concrete, its snapping of chalk lines, sistering of beams and doubling of headers.

I say “God help me”` because tinkering about the house is, in truth, a pastime with no heroes and no social status. Considering how many people are involved (61.7 million households, according to an industry survey), “doing it yourself”” suffers under a remarkably dismal image. On television, in comic strips and elsewhere, the business of home repairs is practiced by bungling husbands, who usually end up with bruised egos and swaddled thumbs. In the minds of many people, the do-it-yourselfer is a well-meaning fellow who has been hit on the head and rendered permanently middlebrow by a falling 2-by-4.

I’ve been thinking about this lately because of an article in Time about movie actor Harrison Ford. A photo showed Ford standing in the shell of a house, which, as the article noted incredulously, he is “actually constructing.” Ford, who once worked as a carpenter, was quoted discussing a bedside table he had made: “It’s a simple piece with turned legs and a band- sawed skirt. I just like the work itself.”

Now this had a surface incongruity that I found pleasing: that an “interstellar swashbuckler,” a “dashing romantic,” a star of five of the 10 “highest grossers of all time” should bother to be his own carpenter! That a Hollywood leading man talking about “skirt” could mean something capable of being band-sawed! It was so square, so reassuring to my do-it-yourself sensibilities. But I also recognized something familiar about that offhand tone and something false about that phrase “just a simple piece.”` I bet Harrison Ford sweated more over that band-sawed skirt and those turned legs than he did over the viper pit in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

A sort of low-key, self-deprecating machismo is, in fact, common among do- it-yourselfers, and it suggests one of the main reasons why this pastime is so discreetly popular. The ability to use tools intelligently is, after all, one of the defining characteristics of the species, and it is still part of the measure of a man. In the Time article, Ford is described as an actor who “plays somebody you can rely on, who will take care of whatever it is, from a kid’s hurt finger to a murder to saving the galaxy. He has that quality.”Carpentry, not space fantasy, is what makes me feel that way. Men may readily assert that they don`t know one end of a hammer from the other; but secretly, all of us like to think that, at the very least, we can drive a nail straight.

I’ve been tinkering around the house ever since my father taught me as a child to take apart a window and make the pulleys work again–a sort of domestic epiphany. Before then, I knew only that windows went up and down, or refused to go up and down. But what my father showed me within the sides of the window was a system of sash cords and counterweights that had the unexpected beauty, even elegance, of engineering. It was, moreover, engineering that a child could fix. And fixing it, I felt competent.

My father and I rarely if ever played catch. What we did was to build things: two garbage sheds (one that rotted and its replacement), a workbench (still standing), a couple of fences, latticework sections for the porch, a wisteria trellis, bookshelves, a rowboat. Sometimes when we finished a project, we would mark an undersurface with our initials and a phrase such as “hoc fecerunt anno Domini 1963.”

At one point or another, almost all handymen go around the bend. They decide to build the Ark in the back yard, or to add a new wing now that the kids have moved out. I call this Do-It-Yourself Dementia, and I speak as one of the afflicted. Three years ago, after years of tinkering and puttering, my wife and I bought a neglected house that we have since come to know as “the kingdom of rot.” We were moved by the ravaged beauty of the place and by an exaggerated sense of our own capabilities.

What followed was the usual hell of restoration and a prolonged drain on our time and finances. I will never be able to make up to my wife for some things: for leaving her with her mother the week after she had given birth so I could spend the weekend working on the house, or for one hot July evening spent smashing apart the old heating system while our 1-year-old was supposed to be sleeping.

By now, on our own and with contractors, we have made the house habitable; parts of it are even beginning to look quite lovely. I begin to see the time when we will pull back from dementia to mere tinkering and puttering. Sometimes I set aside my hammer, clear my mind, and just think, and what strikes me most clearly and puzzles me a bit is the realization that the human urge to say, “We made this. We built this with our own hands,” is so strong.

Family Business: Manchild Coming of Age

My Dad died Saturday, age 92. He was a writer and a passionate teacher of the craft and love of writing. I’ll post an obituary later, but this is an article he wrote for the New York Times magazine about my brother Mark, who has Down syndrome, and about raising him at home when institutionalization was the more standard practice:

My Dad died Saturday, age 92. He was a writer and a passionate teacher of the craft and love of writing. I’ll post an obituary later, but this is an article he wrote for the New York Times magazine about my brother Mark, who has Down syndrome, and about raising him at home when institutionalization was the more standard practice:

MY YOUNGEST SON, MARK, has his suits and jackets fitted with extra care, because, 5 feet tall, he weighs more than 170 pounds and is built like a padded fire hydrant. He is dieting to fight that image, though, and has 27 Special Olympics awards on his wall to prove it, right beside life-size posters of Michael Jackson, Kenny Baker and Barbara Mandrell. Mark is a powerful swimmer, and five of the awards are for first place in the category.

For 31 years, Mark has been a central fact of our family life, knitting us together, trying our patience, helping us laugh, probably making us better people than we would have been without him.

I remember the night call, hours after he was born, and the doctor’s trying to be gentle as the darkness around me grew suddenly deeper: ”I regret having to tell you your new son may be mongoloid.”

They don’t say that anymore. They don’t call leprosy leprosy, either. Now it’s Hansen’s disease. And mongolism is Down’s syndrome, or trisomy 21, a chromosomal abnormality that hinders the development of the mind. The growing brain signals its imprisonment in the smaller skull by causing erratic gait, slower growth, vulnerability to infections, clubfeet, other anomalies.

Knowing I was a medical writer, the doctor shared with me the details that left little room for doubt: the epicanthal fold of the eyelids at either side of the nose, excessive bone-flex even for a newborn, deeper-than-normal postnatal jaundice, clubfeet, the simian line across the palm of each hand. Later, one of many specialists we consulted would say of Mark: ”Let’s leave a door open for me to back out of. There are people in Congress less bright than he may yet turn out to be.”

Nobody’s perfect, in other words. Even so: mongoloid. The word boomed in my soul like the tolling of a leaden gong. No more sleep for me. Next morning, I entered upon a conspiracy of one.

”Why can’t I see the baby?” was my wife’s first question after the kiss, the forced congratulatory smile. The lie ”They’re getting him ready,” came with clinical ease. ”He’ll be up to see you soon.”

Then the quick maternal discovery of his clubfeet, and my too-swift assurance that the feet were ”only an anomaly” which remedial measures would correct. Worst of all, her tearful puzzlement at learning we would have to leave him in the hospital ”for a few more days” to make sure his casts ”weren’t on too tight” – or some such double talk.

Back home without him, I found myself unable to keep up the charade under mounting internal pressure. After a few miserable days, I blurted out the truth and endured her dry-eyed demand that we ”Go bring him home, right away, so I can take care of him. Now. Today.”

Caring for a baby with legs in plaster casts spread wide at the ankles by a rigid steel bar to straighten the growing feet can take its emotional toll. But from the start, Mark’s older brothers, and especially his sisters, devoted themselves to helping us raise him. Under what I now look back on as a cascade of sunrises and sunsets ”laden with happiness and tears,” we overcame any misguided temptation we may have had to institutionalize him.

One undeniable result has been that he is much further along, and far better equipped to deal with life in spite of his limitations, than he would have been if we had done that to him. Today, as he stands poised to see whether he likes it in a group home, we take comfort in knowing we tried to do right by him. Another gain has been that he has done well by us; caring for him has matured us. Aged us too, no doubt, but that would have happened anyway.

The father of a retarded child wonders if in some unforeseeable way he may have contributed to the tragedy (in my case, possibly the case of mumps I had before Mark was conceived). Some men walk out on what they see as an impossible situation, a saddling of their marriage with an unending burden. Some come back. Each case is unique. No one outside it can judge.

Ironies abound. Long before Mark was born, I wrote an article on mental retardation. It helped, I’m told, get Federal funds for research into the causes. And when Hubert H. Humphrey’s granddaughter was born retarded, he and I wrote pieces pleading with readers to recognize that mental retardation is a totally different affliction from mental illness. ”It’s not contagious, either!” Hubert would shout at me, as if I needed convincing. Yet in my own extended family some still think Mark is contagious.

Harder to take is watching him strive, in a family of writers, to produce copy. Pages of hand-scrawled and sometimes typed letters, all higgledy-piggledy, spill from his fevered efforts to ”follow in your footsteps, Dad!” And almost nightly, lonely and eager for an audience, Mark interrupts our reading or television watching to rattle off plots from reruns of ”M*A*S*H.” We try to look attentive, even though it drives us nutty. Shouting matches help ease tension, and I have on occasion threatened to work Mark over. But sooner or later he forgives me. With a hug.

Indefatigable, Mark has handsawed his way through storm-toppled tree trunks without resting, mowed lawns, backstopped me on cement-laying jobs. I repay him with prodigious hero sandwiches, which he seldom fails to praise.

At 31, he still cannot read, but he does guess at numbers, at times embarrassingly well. When, here lately, he began to put a cash value on his toil and asked for pay, I offered him a dollar. He looked at me with a knowing grin and said, quite clearly despite his usual speech problems, ”Five bucks, Dad, five bucks.” I gave him five ones.

For signs like this that the manchild is coming of age, I am grateful. And for something else: I can’t say we feel he’s ready for Congress, but he has given us hope. Unlike the night he was born, in part because of Mark, I am no longer afraid of the dark.

Green Highways: Saving Nature at 65 MPH?

Monarch butterflies could use some roadside relief (Photo: Chip Taylor)

Not long ago, a biologist took Florida landscape architect Jeff Caster aside and suggested that he ought to be designing highway margins not just for safety or scenic value, but as habitat, to help address the nation’s drastic decline in pollinating insects.

Caster passed the idea along to his boss at the Florida State Department of Transportation (DOT), who looked at him as if he were crazy. Even in the best of circumstances, highways are notorious for fragmenting habitat, spreading pollution, causing roadkills, and otherwise disrupting the natural world. Highways are where insects go to be splattered on windshields. “You expect the DOT to do research on bees?” she told him. “Get real.”

Instead, Caster walked her through the reasoning behind the proposal from University of Florida entomologist Jaret C. Daniels: The population of feral honeybees has dropped more than 50 percent nationwide over the past half-century. Pathogens, pesticides, and habitat loss have also decimated native pollinating insect species. But in Florida, agriculture is the second-biggest contributor to the state economy, after tourism, and roughly 100 valuable crops depend on pollinators. Florida DOT not only manages 186,000 acres, about 0.5 percent of Florida’s total area, but its land, says Caster, is “next door to, or one property away from, almost every farm in the state.”

Caster’s bosses all eventually signed onto the proposal, a decision no doubt made easier because the state is now also actively promoting highway wildflower tourism. A $90,000 study to determine how changes in the DOT mowing regimen might benefit roadside pollinator populations is now underway.

In most places, the public may still largely want their highway margins “to be either tidy or flowery,” as a roadside biodiversity report for Scottish Natural Heritage put it early this year. They are not looking for Darwin’s “entangled bank.” But in countries around the world, ecologists, and transportation engineers are increasingly joining in an improbable alliance to turn roadsides and other travel conduits into functional habitat.

In France, highway stormwater runoff ponds have become critical amphibian habitat. In the U.S. Midwest, naturalized roadsides have become prairie corridors and nesting grounds. Hawaii has developed an elaborate program to keep invasive plants from spreading along roads. And, in Florida, researchers are now testing a sophisticated new system to alert motorists to black bears and endangered Florida panthers on the Tamiami Trail.

Designing roads with nature in mind isn’t entirely new. Planners of many early highways, like New York’s Bronx River Parkway in 1907, intended them to look like naturalized countryside. But the emphasis was on scenic value. Interest in roadsides as habitat for native plants and wildlife began to develop in the 1980s and 90s, particularly in northern Europe. The British government, for instance, designed a section of roadside along the M40 east of Oxford as a travel corridor for invertebrates between two protected woodlands. By 1994, 25 butterfly species had colonized the corridor, notably including the rare black hairstreak.

But the pioneering roadside experiments undertaken then have now developed into a movement, encouraged in part by landscape ecologist Richard T.T. Forman’s 2002 book Road Ecology: Science and Solutions. There’s now also an International Conference on Ecology and Transportation. (It meets later this month in Scottsdale, Arizona.)

Why the renewed interest in roadside habitat now? It is one way to respond to the loss of both species and natural spaces as the landscape has become more urbanized and as the expansion and intensification of agriculture have eliminated many old pockets of habitat.

The sides of highways are, in some cases, the only place left to live. In northern Europe, for instance, up to 90 percent of the natural ponds and wetlands have disappeared over the past century. But in France, by law, there are stormwater ponds every two kilometers along highways, and by default they have become a partial substitute — though a somewhat problematic one due to roadkill and other factors. When researchers last year surveyed 58 such highway ponds, they found that they had become home for numerous amphibian species, including one that is now rare in nature.

In Iowa, where there’s little left of the original prairie habitat, farmers who used to set land aside under the federal Conservation Reserve Program have instead withdrawn more than 1.5 million acres since 2008 to plant wall-to-wall corn and try to cash in on the market for ethanol. That makes roadsides “the last refuge, the last vestige of hope” for ground-nesting birds like quail, pheasants, meadowlarks, and bobolinks, as well as for many butterflies and other insect species, says Rebecca Kauten, manager of the integrated roadside vegetation management program at the University of Northern Iowa.

The tripling of herbicide use in agriculture since the introduction of Roundup Ready corn and soybeans has also eliminated milkweed and other native species that used to live in U.S. farm fields. That’s caused monarch butterfly populations to crash, says University of Kansas insect ecologist Orley Taylor, founder of Monarch Watch. One way to partially compensate would be for highway authorities to plant roadsides with milkweed — notably in Alabama, Idaho, Illinois, Texas, West Virginia, and Minnesota, all of which have named monarchs their state butterfly.

The United States, with about 4 million miles of highways, has generally lagged behind European efforts to naturalize roadsides. Belgium, for instance, now has most of its major highway roadsides planted for conservation, and according to a planner at the Department of Nature, Environment, and Energy, it’s one easy way, and sometimes the only way, to put people back in touch with the natural world. Similar efforts in the U.S. have faltered, partly because there’s no central agency promoting such programs.

The U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides funds to states for roadside enhancement, but that can mean anything from sound barriers to decorative plantings: “Arizona does a pretty good job, with lots of natural grasses and cactus,” said an FHWA spokesman. Iowa has also been a leader in protecting roadside habitat, with a program that times mowing to the natural cycles of ground-nesting birds and other species. “But other states may think paving over the roadsides with concrete is the way to go.”

Decisions often get made at the county level, where political patronage often drives the investment in mowers and fuel contracts, according to Monarch Watch’s Taylor. Even though mowing less frequently would simultaneously save tax dollars and benefit the environment, “there’s institutional resistance,” he says. “The guy who runs the highway department wants to defend his fiefdom and keep his little army of mowers.”

The Great Recession has begun to change that mentality by forcing cuts in mowing budgets. Virginia, for instance, found it could save $20 million in 2009 by cutting its roadside mowing in half. But budget pressures also affect programs to develop naturalized roadsides — Minnesota, for example, recently cut $50,000 for its roadside seed-purchasing program.

Resistance may also arise because managing roadsides for biodiversity is much more complicated than managing them for safety. In France, for instance, the same stormwater ponds that now harbor amphibians also typically collect heavy metals, petroleum products, salts, pesticides, and other runoff. That means they may function as a biological sink — a death trap, over the long term — for the very species they attract. Amphibians are 80 percent of the roadkill in some European countries, and heavy traffic has made some populations extinct. Last year, a dozen European nations formed a coalition to develop ways of providing more appropriate freshwater habitat and reducing road mortality.

The idea of attracting wildlife to roads also raises the specter of more accidents for motorists. But in the case of deer, some studies suggest that reduced mowing may actually discourage the animals from using roadsides, because there’s not as much fresh grazing. In Arizona, highway planners choosing native species for roadsides avoid what they call “ice cream species” that might attract elk.

The pressure to make those kinds of nuanced choices will undoubtedly increase, as undeveloped real estate becomes more precious and as new research makes the benefits more apparent. Soybeans, for instance, are a self-pollinating crop. But in Australia and Brazil, studies have recently found that having honeybees nearby increases yields by as much as 50 percent, for reasons that remain open to debate.

At Iowa State University, research by entomologist Matt O’Neal has demonstrated that it’s possible to get the same sort of bump from native pollinators and other beneficial insects living in strips of vegetation just 10 to 50 feet wide. O’Neal’s group has tested a Michigan State University list of tallgrass prairie plants and provided Iowa farmers with a list of a dozen native plant species — like pinnate coneflowers, meadow zisia, and swamp milkweed — that are “best bets” for attracting pollinators.

And where will Iowa farmers plant these precious vegetative strips? The sides of the road may be the only place left.

June 7, 2013

The Last Butterfly: An American Beauty Faces Extinction

Papilio aristodemus male (Photo: Jaret Daniels)

The survival of a spectacular American species depends this week on a small band of volunteers wandering in the dense tropical hardwood hammock of the Florida Keys. Despite the heat and humidity, the searchers must wear heavy jackets, gloves, face masks, and other protective gear to keep off the swarming mosquitoes. It’s backcountry work, often knee-deep in the water, constantly scanning for Schaus’s swallowtail butterfly, a beautifully colored creature with a wingspan as big as a man’s hand, and which is now on the brink of extinction.

Since the emergency collecting effort began back in April, the searchers have found just a single adult, a female. They netted her two weeks ago on Elliott Key in Biscayne National Park and kept her there for four days in a special container, hoping she would produce a crop of up to 400 eggs. But rainy weather worked against them, and she yielded … TO READ THE REST OF THIS ARTICLE CLICK HERE.

June 4, 2013

Murdered for a Turtle Egg Aphrodisiac

Mora working with a marine turtle nest (Photo: action.seaturtles.org)

It’s no secret that protecting wildlife can be dangerous work. As many as 1000 wildlife rangers and conservationists around the world have been murdered over the past decade by poachers, illegal loggers, ranchers, drug dealers and militias, according to one estimate. Still, Costa Rica, long regarded as one of the greenest and happiest countries on Earth, is just about the last place you would expect it to happen.

But late last Thursday night, a young Costa Rican conservationist, together with three women from the United States and a fourth from Spain, found out otherwise.

The group was driving back from patrolling a beach where endangered leatherback sea turtles make their nests in the sand. A downed palm tree blocked their way on a remote stretch of road, and when 26-year-old Jairo Mora Sandoval got out of his Suzuki 4×4 to move it, five masked man with guns suddenly appeared. The kidnappers took the group to an abandoned house, where they tied up the women and stole their cellphones and money. Then two of the kidnappers drove off with Mora in the Suzuki.

Playa Moín, where the incident took place, is … to read the rest of this story, click here.

May 30, 2013

Mammoth Blood, Yes. Cloning? Not So Fast.

There’s nothing quite like fresh blood on the ice to stir excitement in the journalistic community, especially when it’s the blood of an extinct mammoth. It’s an irresistible leap of the imagination to the idea of Jurassic Park-style cloning, and the vision of extinct giants rumbling out of the Ice Age into the modern world. Mix in an element of the Asian wildlife-trafficking mafia in hot pursuit of ivory—from animals now living, or very, very dead—and you have a story.

There’s nothing quite like fresh blood on the ice to stir excitement in the journalistic community, especially when it’s the blood of an extinct mammoth. It’s an irresistible leap of the imagination to the idea of Jurassic Park-style cloning, and the vision of extinct giants rumbling out of the Ice Age into the modern world. Mix in an element of the Asian wildlife-trafficking mafia in hot pursuit of ivory—from animals now living, or very, very dead—and you have a story.

But let’s stick with the facts, for now.

The blood turned up earlier this month when a team of Russian paleontologists began to excavate a newly discovered carcass of a female mammoth on the Lyakhovsky Islands, off the north coast of central Siberia.

“The lower part of the body was resting in nearly pure ice, and the upper part was found in the middle of the tundra,” team leader Semyon Grigoriev told a Russian newspaper.

The temperature was -10 Celsius (about 14 degrees Fahrenheit) and the researchers were working around the carcass with a poll pick, a miner’s tool like a crowbar. Suddenly, they hit a pocket underneath the ice, and to their amazement, liquid blood came flowing out … To read the rest of this story click here.

The Dragon Mother of King Kong

One fine evening in the mid-1920s, W. Douglas Burden, a New York City gentleman “with sporting tastes and a real interest in natural history,” came home to ask his wife “how she would like to go dragon hunting.”

One fine evening in the mid-1920s, W. Douglas Burden, a New York City gentleman “with sporting tastes and a real interest in natural history,” came home to ask his wife “how she would like to go dragon hunting.”

Burden was a great-great grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, with a bank account to match, and a track record as an adventurer in his own right. So this was the sort of whim he could readily indulge. In 1926, with the blessings of the American Museum of Natural History, Burden and his expedition set out in the S.S. Dog for an obscure island in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, where the existence of a huge reptile had been reported.

Burden was seeking what he called “a primeval monster in a primeval setting.” Rumors of dragons had been repeated by Dutch sailors in the East Indies as far back as the 1600s. Finally, in 1910, a Dutch colonial administrator with a double-barreled name, Lieutenant van Steyn van Hensbroek, visited the Lesser Sundas, and came back with the skin of a six-foot-long Varanus lizard. Van Hensbroek published the first scientific description and named the species Varanus komodoensis, after the island of Komodo, where it was found.

That account inspired Burden to undertake this expedition in pursuit of bigger specimens. But even very big Varanus lizards did not match his sense of adventure, so he dubbed them “Komodo dragons” instead. The destination also needed to be suitably mythic. When his expedition first laid eyes on the island … to read the rest of this story, click here.

May 28, 2013

Skull and Bones: The Pleistocene Diet

Flick-blade marsupial lion (Illustration: Peter Schouten)

Let me admit up front that I am an enthusiastic admirer of predatory behaviors. I have taken unseemly delight in the spectacle of a cheetah tackling and disassembling a wildebeest. And once, while tracking radio-collared African wild dogs in Botswana, I had the great privilege of arriving at the scene of the kill before the rest of the pack. (The smell of fresh blood in the morning. Hmmmm.) When a television documentary dwells mournfully on the plight of an aging zebra no longer able to keep up with the herd, I am generally rooting for the killers.

Kanjera dig

And I have a hunch I am not alone. Research on predatory behaviors has been in the news a lot lately, starting with the discovery of the earliest known archaeological evidence of our own past as predators, and as scavengers on other predators’ kills. Writing early this month in PLOS ONE, Baylor University anthropologist Joseph Ferraro and his co-authors describe new finds from the Kanjera archaeological site [photo] on the shores of Lake Victoria in western Kenya.

For our hominin ancestors two million years ago, this was the perfect picnic spot, a grassy plain between the shore of a lake and the wooded slopes of nearby hills and mountains. And the menu? Mainly small to mid-size antelopes like Grant’s gazelle and topi, but with the occasional buffalo or hippopotamus as a special treat.

The authors of the new paper note that when modern lions or hyenas kill small antelope, they generally consume the carcass within minutes after death. “As a result, hominins could only have acquired these valuable remains on the savanna through active hunting.” The fossil bones also show evidence of tool use “consistent with both defleshing and disarticulation activities,” including marks of fist-size hammerstones for … To read the rest of this article click here.