Richard Conniff's Blog, page 76

March 25, 2013

An Insect That Makes Tarantino Sound Nice

Species names just seem to get stranger and stranger, and now we have a parasitoid wasp named after a character in a Quentin Tarantino film.

In an article in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research, a new species from Thailand in the genus Cystomastacoidesis gets the name kiddo, after the character Beatrix Kiddo in Tarantino’s ‘Kill Bill’ films.

Parasitoid wasps lay their eggs on other insects and spiders, and the larva then hatches out and feeds on its host, often devouring it bit by bit while it remains alive and paralyzed.

Naturally, Donald Quicke and his co-authors thought of the deadly assassin played by Uma Thurman. The fictional Kiddo is a master of the “Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique,” a method of killing a person by quickly striking five pressure points around the heart with the fingertips. After the victim takes five steps, the heart explodes and the person falls dead.

But nature has a way of making even Tarantino macabre fantasies seem almost nice.

March 22, 2013

The Kon Artist

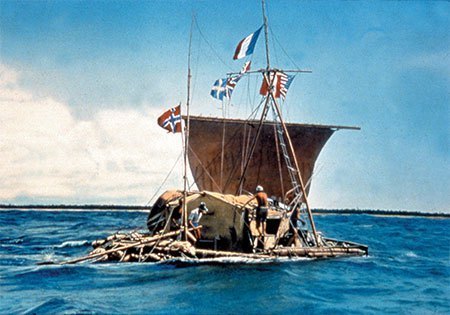

Smithsonian has an article in its current issue about Kon-Tiki, the new Oscar-nominated biopic of Thor Heyerdahl. The film tries to turn the celebrated Norwegian adventurer into a demi-god, much as Heyerdahl himself did in his own lifetime. Like a lot of mid-twentieth century children, I grew up on Heyerdahl’s books and thought of him as a hero. But I later came to realize that Heyerdahl was also a great fraud. Here’s the piece I wrote in 2002, also for Smithsonian, describing my encounter with his deceptions on Easter Island:

Smithsonian has an article in its current issue about Kon-Tiki, the new Oscar-nominated biopic of Thor Heyerdahl. The film tries to turn the celebrated Norwegian adventurer into a demi-god, much as Heyerdahl himself did in his own lifetime. Like a lot of mid-twentieth century children, I grew up on Heyerdahl’s books and thought of him as a hero. But I later came to realize that Heyerdahl was also a great fraud. Here’s the piece I wrote in 2002, also for Smithsonian, describing my encounter with his deceptions on Easter Island:

One of the first lessons you learn going into the field as an anthropologist, archaeologist or journalist is never to come back empty-handed. The cost of the expedition, the need to gratify sponsors, the urge to make a name, all turn up the pressure to get the story. So it’s easy to forget the second great lesson of fieldwork: beware of a story that’s just a little too good.

Thor Heyerdahl, who died in April at the age of 87, spent much of an active and sometimes inspiring life in the thrall of one good story. He believed that, long before Columbus, early ocean travelers—tall, fair-skinned, redheaded Vikings much like himself—spread human culture to the most remote corners of the earth. Academics scoffed, particularly at his idea that the islands of the mid-Pacific had been colonized by way of South America, rather than by Polynesians from the western Pacific. In 1947, Heyerdahl risked his life attempting to prove his point. He built a balsa-log raft, the Kon-Tiki, and in one of the great ocean adventures of the 20th century, he and his small crew made the harrowing 4,300-mile voyage from Peru to French Polynesia.

In the process, Heyerdahl established himself as an almost mythic hero. His best-selling book Kon-Tiki inspired a new generation of scholars—many of whom went on to systematically refute their hero’s great idea.

The trouble with a good story is that it has a way of distorting the facts: we see what we want to see and close our eyes to everything else. In the 1970s, scholars and filmmakers were so enraptured with the idea of peace-loving, Stone Age hunter-gatherers they failed to notice that the gentle Tasaday were a very modern Filipino hoax. In the harsher zeitgeist of more recent times, a hotly disputed book, Darkness in El Dorado, charges that anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon believed so firmly in the savagery of Venezuela’s Yanomami that he instigated the very bloodshed he went there to document. (Chagnon steadfastly denies the charge.)

A good story can be so compelling that teller and subject become entrapped together in its charms, and this was never more true than when Heyerdahl came swashbuckling onto Easter Island in 1955, determined to find hard evidence of South American origins.

He liked to be known to the islanders as Señor Kon-Tiki, and asked, among other things, for samples of old pottery, a technology known in South America but not in Polynesia. One enterprising islander promptly broke up a pot and buried the shards, a ruse Heyerdahl readily detected. “If there is a moral to all this,” another member of the expedition wrote later, “it is that archaeologists should be cautious about telling local, nonprofessionals what they would like to find.” Incautiously, Heyerdahl displayed a stuffed caiman from South America and the llama-like camel on a pack of cigarettes, to elicit the kinds of artifacts he sought.

His 1958 book, Aku-Aku, described just how brilliantly he succeeded. After discovering that the islanders had secret family caves full of “ancient” stone sculptures, Heyerdahl gained admission to them by invoking his own considerable spiritual aura, or aku-aku. By giving the islanders clothing, food and cigarettes, he persuaded them to hand over almost a thousand carvings, some of them redolent of South America: a penguin, llamas, a reed boat like the ones used on Lake Titicaca in Peru.

When I visited the islanders in 1992, they still clearly admired Señor Kon-Tiki, and they celebrated him as “good p.r. for Easter Island.” But they delighted in pointing out how selective and misleading he had been in the evidence he marshaled for his hypothesis.

One day I was talking with an island businessman in gold-rimmed glasses and a blue button-down shirt. “Thor knew I was a very good carver, and he came to see me,” he said. “He asked me to take out of my cave all the ancient objects that I had there, to sell to him. I told him I didn’t have anything, and he said, ‘I know exactly what you have. At the entrance to your cave, there is the head of a whale…’ And he started mentioning things that he insisted I had. I said I didn’t have them, and he said, ‘No, no, no! You have them and I’ll pay you for them.’ So I understood perfectly well that he was saying, ‘Carve them and I’ll pay you.’”

He thought about this for a moment, then added: “He was fooling the world. He was making his own spectacle….He was writing the book to make people say, ‘Ah!’ And it was good for the island in a certain way, because tourists came.”

The first time I heard this, I didn’t believe it: the islanders have a rich tradition of making up their own history, and they naturally wanted to seem like the shrewd ones in this relationship. But the implication that Aku-Aku was riddled with genial deceptions by Heyerdahl and the islanders, on one another and the world, came up over and over, with only minor variation.

One of the most interesting accounts came from a man whose secret cave was the source of 47 of the celebrated stone figures. In his 1975 book, The Art of Easter Island, Heyerdahl described at length how he determined their authenticity, concluding, “It was obvious to all of us that Pedro Pate could not have staged this cave. …” Pate, now deceased, was a 73-year-old fisherman and carver at the time of my visit, and he laughed at the idea of authenticity. When he’d first brought a sack of carvings to Heyerdahl’s camp, he said Heyerdahl refused to look at them. The venue was wrong. “He said, ‘No, no, no, you take these things to the caves,’” where Heyerdahl could discover them.

At Pate’s cave, Heyerdahl wrote, he was particularly impressed with a carving of a two-masted reed boat, on which the dust lay a half-inch thick. He carried it out of the cave himself. To demonstrate that no modern islander could have produced such a masterpiece, Heyerdahl reported that one of the best carvers on the island had tried to create a replica; the result, he wrote, was clumsy and unconvincing.

I showed Pate a two-page photograph of the reed boat from Heyerdahl’s book, and he grinned. He’d carved the boat himself, he said. Dubious, I offered him $100 to carve such a boat now, 37 years later, and he accepted. When I visited him again, he was working in front of his house, with the half-formed sculpture propped up on a block of wood and his chisels, rasps and an adze laid out beneath him on a piece of corrugated cardboard.

A few days later, he presented me with the 18-inch-long reed boat he had carved. It was as good as the one in the book. I paid him, and as he wrapped the boat for me to take, he told me confidentially, like a shopkeeper suggesting a second pair of pants to go with a new suit, that he had actually carved two.

When I got the news, ten years later, that Heyerdahl had died, I retrieved that old carving from my yard. It’s broken into pieces now, and clotted with leaf litter and mud. I phoned an Easter Island archaeologist, William Ayres, who chairs the Pacific Island Studies program at the University of Oregon, and he confirmed that many of Heyerdahl’s cave carvings are now deemed modern. I leafed through my old notes from an interview with an islander who used to kid Heyerdahl in later years about the faked carvings. But Heyerdahl stuck by his story to the end. Once, at a conference, a colleague asked him how he could persist with the South American hypothesis when his own archaeologists had produced overwhelming evidence that the Easter Island culture had, in fact, come from Polynesia. Heyerdahl looked down at him like a giant crane peering down on a small worm, and he said, ‘‘Well, I have my audience.”

An audience is what everyone who works in the field ultimately wants: a chance to climb up out of the dust and make the world say, “Ah!” But at what cost? Turning over Pedro Pate’s sculpture and studying it under the light at my desk, it seemed to me that what I held in my hand was that titillating and very dangerous thing: a good story.

March 21, 2013

Mountain Biking in Africa Can Get Gnarly

Building Roads to Save the Wilderness

A typically scene of illegal logging on an unplanned road into the Amazon

A press release today from the University of Cambridge touts the argument that building roads “could help rather than harm the environment.” It’s based on an article in the current Nature by William F. Laurence and Andrew Balmford. Here’s how the press release puts it:

Two leading ecologists say a rapid proliferation of roads across the planet is causing irreparable damage to nature, but properly planned roads could actually help the environment.

But while this idea has a certain man-bites-dog news value, it’s not what the scientific paper actually says. And check out the weird choice of an image to illustrate the press release (below). It’s like a car commercial about the joy of the open road. Are you shocked? I am shocked. Laurence and Balmford aren’t talking about some ingenious scheme to road-build our way to better animal migratory routes. They’re just trying to minimize the damage from the roads now extending willy-nilly into the wilderness. Here’s the press release again:

Weirdly, the press release from the University of Cambridge uses this bucolic picture to illustrate the story. The picture at top is the one that actually appears in Nature. (Photo: © Iakov Kalinin / Fotolia)

“Loggers, miners and other road builders are putting roads almost everywhere, including places they simply shouldn’t go, such as wilderness areas,” said Professor Andrew Balmford of the University of Cambridge, UK. “Some of these roads are causing environmental disasters.”

“The current situation is largely chaos,” said Professor William Laurance of James Cook University in Cairns, Australia. “Roads are going almost everywhere and often open a Pandora’s Box of environmental problems.”

“Just look at the Amazon rainforest,” said Laurance. “Over 95 percent of all forest destruction and wildfires occur within 10 kilometers of roads, and there’s now 100,000 kilometers of roads crisscrossing the Amazon.”

The problem is that development now happens at the whim of the loggers and miners who build the roads, Laurence and Balmford write:

Often, agriculture follows roads created for other purposes, such as mining or logging. This can result in the expansion of farms into places with marginal soils or climates, or into locations that are too far from markets to be cost-effective. Conversely, well-planned roads can increase farmers’ access to markets, reducing waste and improving profits. Anecdotal evidence indicates that ongoing road improvements in parts of sub-Saharan Africa are gradually raising rural farmers’ access to fertilizers and increasing their capacity to transport crops to markets.

Several studies suggest that road improvements in areas suited to agricultural development can attract migrants away from vulnerable areas, such as the edges of pristine forests …

And that can concentrate human populations in areas that are actually more productive for agriculture.

But how to change where the mining and logging roads go? The authors argue for a shift in public policy and a dollop of public shaming:

Large road projects are often funded by taxpayers, investors or international donors who can be surprisingly responsive to environmental concerns. For example, if corporations that build environmentally bad roads are publicly named, they can lose customers and shareholders. Concord Pacific, a Malaysian logging corporation, was publicly castigated in the early 2000s for bulldozing a 180-kilometre-long road into the highlands of Papua New Guinea — ostensibly to aid local communities. After the company grabbed more than US$60 million in illegal timber, it was fined $97 million by the national court of Papua New Guinea.

Their proposed alternative is a system of global mapping to plan roads more strategically. (Parental advisory: The following passage includes the Z word, widely regarded in the American West as a Stalinist intrusion on individual property rights):

We believe that a collaborative, global zoning exercise is needed to identify where road building or improvement should be a priority, where it should be restricted and where existing roads should be closed. A multidisciplinary team could integrate and standardize satellite data on intact habitats with information on transport infrastructure, agricultural yields and losses, biodiversity indicators, carbon storage and other relevant factors.

Finally, the paper suggests a way to limit the damage when roads are inevitable:

For transport projects that have high environmental costs but seem unavoidable, such as Brazil’s Manaus-Porto Velho highway — which is now under construction and has the potential to speed settlers and land speculators into the heart of the Amazon when complete — alternatives such as railways or river transport might be effective compromises. Trains and boats move people and products but limit the human footprint by stopping only at specific places.

All good ideas. Now it needs statesmanship and public pressure to make logging and mining industries–and the national governments who view them as a ready source of short-term cash–to buy into such a scheme.

SOURCE: William F. Laurance, Andrew Balmford. Land use: A global map for road building. Nature, 2013; 495 (7441): 308 DOI: 10.1038/495308a

March 20, 2013

Biodiversity May Not Protect us from Disease, After All

The theory put forward a couple of years back was that biodiversity prevents emerging diseases from actually emerging. But now researchers at Stanford University say, “Hold on a minute.”

First, by way of background, here’s how I described the “dilution effect” at the time:

A diversity of species can also help prevent the emergence of new diseases, though we tend to blame, rather than credit, nature for this particular ecosystem service. We sometimes respond to Lyme disease, for instance, by trying to kill the major players, blacklegged ticks and white-footed mice. But the “dilution effect,” proposed by Rick Ostfeld at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, suggests counterintuitively that having the broadest variety of host species in a habitat is a better way to limit disease. Some of those hosts will be ineffective, or even dead ends, at transmitting the infectious organism. So they dilute the effect and keep the disease organism from building up and spilling over to humans. But when we reduce biodiversity by breaking up the forest for our backyards, we accidentally favor the most effective host — in this case, the white-footed mouse. And we free the undiluted disease organism to operate at full strength.

The implications go well beyond Lyme disease. Around the world over the past half-century, researchers have tracked about 150 emerging infectious diseases, from Ebola to HIV, with 60 to 70 percent being zoonotic — that is, transmitted from animals to humans. “The question,” says Aaron Bernstein, a Harvard pediatrician and co-editor of the 2008 book Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity, “is whether humans are doing something to make these zoonotic diseases come out of the woodwork.” Clearly, we are doing a lot of one particular thing — knocking down forests and creating species-poor habitats with no “dilution effect” in their place. Thus the fear is that many more such epidemics may lie ahead.

Now here’s the discouraging word from Stanford University:

More than three quarters of new, emerging or re-emerging human diseases are caused by pathogens from animals, according to the World Health Organization.

But a widely accepted theory of risk reduction for these pathogens – one of the most important ideas in disease ecology – is likely wrong, according to a new study co-authored by Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment Senior Fellow James Holland Jones and former Woods-affiliated ecologist Dan Salkeld.

The dilution effect theorizes that disease risk for humans decreases as the variety of species in an area increases. For example, it postulates that a tick has a higher chance of infecting a human with Lyme disease if the tick has previously had few animal host options beyond white-footed mice, which are carriers of Lyme disease-causing bacteria.

If many other animal hosts had been available to the tick, the tick’s likelihood of being infected and spreading that infection to a human host would go down, according to the theory.

If true, the dilution effect would mean that conservation and public health agendas could be united in a common purpose: to protect biodiversity and guard against disease risk. “However, its importance to the field or the beauty of the idea do not guarantee that it is actually scientifically correct,” Jones said.

In the first study to formally assess the dilution effect, Jones, Salkeld and California Department of Public Health researcher Kerry Padgett tested the hypothesis through a meta-analysis of studies that evaluate links between host biodiversity and disease risk for disease agents that infect humans.

The analysis, published in the journal Ecology Letters, allowed the researchers to pool estimates from studies and test for any bias against publishing studies with “negative results” that contradict the dilution effect.

The analysis found “very weak support, at best” for the dilution effect. Instead, the researchers found that the links between biodiversity and disease prevalence are variable and dependent on the disease system, local ecology and probably human social context.

The role of individual host species and their interactions with other hosts, vectors and pathogens are more influential in determining local disease risk, the analysis found.

“Lyme disease biology in the Northeast is obviously going to differ in its ecology from Lyme disease in California,” Salkeld said. “In the Northeast, they have longer winters and abundant tick hosts. In California, we have milder weather and lots of Western fence lizards (a favored tick host) that harbor ticks but do not transmit the Lyme disease bacterium.”

So, these lizards should be considered unique in any study of disease risk within their habitat. Or, as Salked put it, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

Broadly advocating for the preservation of biodiversity and natural ecosystems to reduce disease risk is “an oversimplification of disease ecology and epidemiology,” the study’s authors write, adding that more effective control of “zoonotic diseases” (those transmitted from animals to humans) may require more detailed understanding of how pathogens are transmitted.

Specifically, Jones, Salkeld and Padgett recommend that researchers focus more on how disease risk relates to species characteristics and ecological mechanisms. They also urge scientists to report data on both prevalence and density of infection in host animals, and to better establish specific causal links between measures of disease risk (such as infection rates in host animals) and rates of infection in local human populations.

For their meta-analysis, the researchers were able to find only 13 published studies and three unpublished data sets examining relationships between biodiversity and animal-to-human disease risk. This kind of investigation is “still in its infancy,” the authors note. “Given the limited data available, conclusions regarding the biodiversity-disease relationship should be regarded with caution.”

Still, Jones said, “I am very confident in saying that real progress in this field will come from understanding ecological mechanisms. We need to turn to elucidating these rather than wasting time arguing that simple species richness will always save the day for zoonotic disease risk.”

Bear in mind that a meta-analysis based on only 13 published studies does not constitute the last word on what could be a life-or-death question.

March 16, 2013

Setting Snakes Loose in Ireland

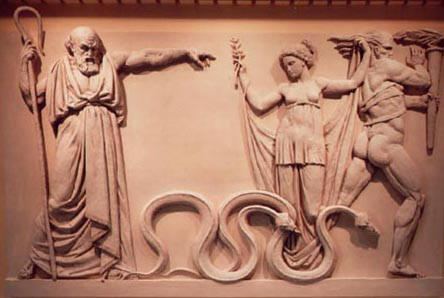

St. Patrick casts out the snakes

Here’s a little heresy-cultural and environmental– for St. Paddy’s Day. It’s from The New York Times:

During the Celtic Tiger boom, snakes became a popular pet among the Irish nouveaux riches, status symbols in a country famous for its lack of indigenous serpents. But after the bubble burst, many snake owners could no longer afford the cost of food, heating and shelter, or they left the country for work elsewhere. Some left their snakes behind or turned them loose in the countryside, leading to some startling encounters.

A California king snake was found late last year in a vacant store in Dublin, a 15-foot python turned up in a garden in Mullingar, a corn snake was found in a trash bin in Clondalkin in South Dublin, and an aggressive rat snake was kept in a shed in County Meath, northwest of Dublin, an area dotted with sprawling houses built during the boom.

“The recession is the thing that’s absolutely causing this,” said Kevin Cunningham, a 37-year-old animal lover who started the National Exotic Animal Sanctuary after he left his job at a Dublin nightclub. He has transformed an old single-room schoolhouse near Ballivor, a hamlet in the Meath countryside, into a reptile sanctuary.

“It was about status,” Mr. Cunningham said as he waved to a four-foot red iguana that was found under a sink in an abandoned house in Dublin. “During the boom, people treated these animals as conversation starters.”

Animals have always been abandoned in greater numbers in times of famine, economic hardship and mass emigration in Ireland, but in the past that usually meant farm animals. The Dublin Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was taking in five or six emaciated horses a week as recently as 2010. Now, though, snakes are more common among the foundlings, including a python named Basie that someone dropped by the side of a road.

“In the Tiger economy,” said P. J. Doyle, a reptile expert, “young people could pay 600 quid for a snake” and the necessary equipment — about $700 to $1,000 during much of the boom. But these days, he said, some owners “just drive up and throw them somewhere.”

Mr. Doyle, a hulking man with weathered skin and a gap between his teeth, helped the cruelty prevention society brace for an influx of reptiles around, of all dates, St. Patrick’s Day, when the warmer spring weather means that the coldblooded snakes will be more active and more likely to show themselves.

“We always get a bump in calls around Paddy’s Day,” Gillian Bird, the education officer at the society, said as she pet Carl, a green iguana from South America that she named after a colleague’s boyfriend.

Irish legend holds that the country has no native snakes because St. Patrick banished them in the fifth century. But science says the country was snake-free long before Patrick’s time. When the glaciers of the most recent ice age retreated from the British Isles more than 10,000 years ago, Ireland was already separated from the rest of Europe by open sea, an isolated ecosystem with a damp, chilly climate that is hostile to almost all reptiles, other than a common lizard.

Most of the recent snake sightings have occurred in the counties around Dublin, where the newly prosperous congregated in the country’s boom years. The government does not require owners to register pet reptiles, so there are no official statistics on the total number of snakes present in the country.

“If you buy a dog, you need a license, but if you buy a snake, you don’t,” said Brendan Ryan, a director of the Irish Pest Control Association.

Like the country’s housing boom and subsequent bust, the snake influx can partly be traced to European integration. In the years when Ireland stood somewhat apart from the broader European economy, it had strict regulations on the types of plants and animals that could be imported, but now Ireland’s standards match the more relaxed rules of other member states of the European Union.

“We’ve got no regulation whatsoever covering exotics,” said James Hennessy, zoo director and founder of Reptile Village Conservation Zoo in County Kilkenny. “Once it’s in Europe legally and coming from other European states, you can pick up whatever you want.”

Reptile Village is often called upon to rescue animals, including a crocodile that had been bought online and then abandoned in a Dublin apartment and a six-foot boa constrictor that had taken up residence under a skylight in an attic in County Meath. “His name’s Sammy, and he’s brilliant,” Mr. Hennessy said of the snake.

Read the full article here.

March 13, 2013

Why Eyespots? The Better to Scare Spiders

Baby blues on an Antheraea polyphemus (Photo: Howard Ensign Evans, Colorado State Univ.)

Eye spots on animals have always intrigued and occasionally alarmed me. Like most naturalists, I always assumed that they had evolved on butterflies and other small animals to scare off birds, snakes, and other big, nasty predators.

Now it turns out that spiders, those underrated predators, may also drive natural selection of this trait. Here’s the press release:

Mar. 12, 2013 — Since the time of Darwin 150 years ago, researchers have believed large predators like birds mainly influenced the evolution of coloration in butterflies. In the first behavioral study to directly test the defense mechanism of hairstreak butterflies, University of Florida lepidopterist Andrei Sourakov found that the appearance of a false head — a wing pattern found on hundreds of hairstreak butterflies worldwide — was 100 percent effective against attacks from a jumping spider. The research published online March 8 in the Journal of Natural History shows small arthropods, rather than large vertebrate predators, may influence butterfly evolution.

“Everything we observe out there has been blamed on birds: aposematic coloration, mimicry and various defensive patterns like eyespots,” said study author Andrei Sourakov, a collection coordinator at the Florida Museum of Natural History’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity on the UF campus. “It’s a big step in general and a big leap of faith to realize that a creature as tiny as a jumping spider, whose brain and life span are really small compared to birds, can actually be partially responsible for the great diversity of patterns that evolved out there among Lepidoptera and other insects.”

Arachnophobe: Red-banded hairstreak

Sourakov’s behavioral experiments at the McGuire Center showed the Red-banded Hairstreak butterfly, Calycopis cecrops, whose spots and tail imitate a false head, successfully escaped all 16 attacks from the jumping spider, Phidippus pulcherrimus. When 11 other butterfly and moth species from seven different families were exposed to the jumping spider, they were unable to escape attack in every case. Sourakov videotaped the experiments and analyzed the results in slow motion.

“From the video, you can see the spider is always very precise,” Sourakov said. “In one video, the spider sees a moth that looks like a leaf and it walks very carefully around to the head and then jumps at the head region. The spider has an innate or acquired ability to distinguish the head region very well and it always attacks there to deliver its venom to the vital center to instantly paralyze the prey. Most importantly, the spider is very small, so sometimes its prey is 10 times larger.”

The species of hairstreak butterfly and jumping spider used in the experiment are both common in the southeastern U.S., with similar relatives spread worldwide. In nature, the spider and hairstreak come into contact when the butterfly lands on leaves or flowers to rest and feed. Female red-banded hairstreak butterflies lay their eggs in leaf litters, which are often crawling with spiders.

David Wagner, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut who was not involved with the study, said the research shows scientists need to rethink what drives adaptive coloration patterns because the results suggest that “birds are only part of the story.”

“I’m just so impressed with Andrei’s experimental protocol and the fact that the jumping spider could not catch the hairstreak butterflies,” Wagner said. “His empirical study will do much to cause us to rethink the vision and the visual acuity that certain invertebrate predators have when hunting their prey and how this has really molded how some organisms not only look like, but perhaps how they act, as well.”

Unlike other butterflies, hairstreaks constantly move the hind wings that carry the false head pattern, a behavior that seems to increase in the presence of the spider, as if the butterfly is attracting attention to itself, Sourakov said. In museum collections, hairstreak specimens are frequently found with the false-head portion of the wings missing. During the experiments, the spider always attacked the butterfly’s false head, thereby avoiding its vital organs.

“The false head hypothesis in hairstreaks has been in circulation for a long time because people always speculated that their tails move around in order to fake out the predators, but there was little experimental evidence,” Sourakov said.

Sourakov said he hopes the study encourages behavioral ecologists to further test the idea that evolution in butterflies and moths may be driven by small invertebrate predators.

“This clearly shows it’s possible that many spectacular patterns that we find in smaller insects may be due to spider pressure rather than bird pressure,” Sourakov said. “The butterfly escapes from the spider — it’s a fairytale story.”

Source: Andrei Sourakov. Two heads are better than one: false head allowsCalycopis cecrops(Lycaenidae) to escape predation by a Jumping Spider,Phidippus pulcherrimus(Salticidae). Journal of Natural History, 2013; : 1 DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2012.759288

March 12, 2013

Why Species Discovery Matters: A Talk by Richard Conniff

Here’s a talk I gave at Ursinus College in February. It’s about the discovery of species, and how that changed almost everything. It’s an hour long, including the questions. So skip around and see if you find something you like.

Here’s a talk I gave at Ursinus College in February. It’...

Here’s a talk I gave at Ursinus College in February. It’s about the discovery of species, and how that changed almost everything. It’s an hour long, including the questions. So skip around and see if you find something you like.

Strategies for Possible Survival on Earth

Here’s another misguided piece of extraterrestrial wishful thinking, in the form of a press release purporting to tell us the secrets of life on Mars. Except that the creatures being studied live, um, right here on Earth. But it is apparently too boring to just take them for what they are.

The study comes from the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the money to pay for it comes, wait, wait, from NASA.

You may recall that NASA got in trouble for this sort of thing not long ago: In 2010, a scientist funded by the space agency purported to have found a prototype for extraterrestrial life in a bacterial species that substituted arsenic for phosphorous in fundamental biochemistry. That species lived not on Mars but in California’s Mono Lake. And as subsequent studies have shown, it didn’t really do what the research suggested at all.

My favorite piece of outer space woo-woo thinking along these lines was a 2011 article in Acta Aeronautica, a scholarly journal, arguing that the real value of studying how species on Earth communicate is to “de-provincialize” our thinking about how to communicate with extraterrestrials. Think about this next time you are talking to your dog. (That one was paid for by the SETI Institute, which, thanks to a rare act of Congressional wisdom, no longer receives its funding via NASA .)

Sooner or later, we are going to figure out that we have absolutely no chance of surviving on other planets, and only the teeny-weeny-weaniest chance of ever communicating with life forms on other planets.

Meanwhile, by even the most conservative account, there are at least eight million species here on Earth we have not yet even identified. And they are worth studying entirely for themselves. They are worth studying not least so we can figure out how not to annihilate them. Maybe then we can figure out how to survive on the only planet we will ever know.

But for now, here we go again, with “Strategies for Possible Survival on Mars” that turn out to be real strategies for surviving on Earth.

Strategies for Possible Survival On Mars: Scientists Found Differences in Core Proteins from a Microorganism That Lives in a Salty Lake in Antarctica

Mar. 11, 2013 — Research from the University of Maryland School of Medicine has revealed key features in proteins needed for life to function on Mars and other extreme environments. The researchers, funded by NASA, studied organisms that survive in the extreme environment of Antarctica. They found subtle but significant differences between the core proteins in ordinary organisms and Haloarchaea, organisms that can tolerate severe conditions such as high salinity, desiccation, and extreme temperatures. The research gives scientists a window into how life could possibly adapt to exist on Mars.

The study, published online in the journal PLoS One on March 11, was led by Shiladitya DasSarma, Ph.D., Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and a research scientist at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology.

Researchers found that Haloarchaeal microbes contain proteins that are acidic, with their surface covered with negatively charged residues. Most ordinary organisms contain proteins that are neutral on average. The negative charges found in the unusual organisms keep proteins in solution and help to hold on tightly to water, reversing the effects of high salinity and desiccation.

In the current study, the scientists identified additional subtle changes in the proteins of one Haloarchaeal species named Halorubrum lacusprofundi. These microbes were isolated from Deep Lake, a very salty lake in Antarctica. The changes found in proteins from these organisms allow them to work in both cold and salty conditions, when temperatures may be well below the freezing point of pure water. Water stays in the liquid state under these conditions much like snow and ice melt on roads that have been salted in winter.

“In such cold temperatures, the packing of atoms in proteins must be loosened slightly, allowing them to be more flexible and functional when ordinary proteins would be locked into inactive conformations” says Dr. DasSarma. “The surface of these proteins also have modifications that loosen the binding of the surrounding water molecules.”

“These kinds of adaptations are likely to allow microorganisms like Halorubrum lacusprofundi to survive not only in Antarctica, but elsewhere in the universe,” says Dr. DasSarma. “For example, there have been recent reports of seasonal flows down the steep sides of craters on Mars suggesting the presence of underground brine pools. Whether microorganisms actually exist in such environments is not yet known, but expeditions like NASA’s Curiosity rover are currently looking for signs of life on Mars.”

“Dr. DasSarma and his colleagues are unraveling the basic building blocks of life,” says E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland and John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “Their research into the fundamentals of microbiology are enhancing our understanding of life throughout the universe, and I look forward to seeing further groundbreaking discoveries from their laboratory.”

Dr. DasSarma and his colleagues are conducting further studies of individual proteins from Halorubrum lacusprofundi, funded by NASA. The adaptations of these proteins could be used to engineer and develop novel enzymes and catalysts. For example, the researchers are examining one model protein, β-galactosidase, that can break down polymerized substances, such as milk sugars, and with the help of other enzymes, even larger polymers. This work may have practical uses such as improving methods for breaking down biological polymers and producing useful materials (see Karan et al. BMC Biotechnology).

Share this story on Facebook, Twitter, and Google:Other social bookmarking and sharing tools:

Ram Karan, Melinda D Capes, Priya DasSarma, Shiladitya DasSarma. Cloning, overexpression, purification, and characterization of a polyextremophilic β-galactosidase from the Antarctic haloarchaeon Halorubrum lacusprofundi. BMC Biotechnology, 2013; 13 (1): 3 DOI: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-3

Shiladitya DasSarma, Melinda D. Capes, Ram Karan, Priya DasSarma. Amino Acid Substitutions in Cold-Adapted Proteins from Halorubrum lacusprofundi, an Extremely Halophilic Microbe from Antarctica. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8 (3): e58587 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058587