Richard Conniff's Blog, page 78

February 17, 2013

Why Men Go Ga-Ga for Women’s Breasts

Apparently, it’s not so much gaga as goo-goo. Here’s the explanation from Larry Young and Brian Alexander, authors of the book The Chemistry Between Us:

Apparently, it’s not so much gaga as goo-goo. Here’s the explanation from Larry Young and Brian Alexander, authors of the book The Chemistry Between Us:

So breasts are mighty tempting. But what purpose could this possibly serve?

Some evolutionary biologists have suggested that full breasts store needed fat, which, in turn, signals to a man that a woman is in good health and therefore a top-notch prospect to bear and raise children. But men aren’t known for being particularly choosy about sex partners. After all, sperm is cheap. Since we don’t get pregnant, and bear children, it doesn’t cost us much to spread it around. If the main goal of sex — evolutionarily speaking — is to pass along one’s genes, it would make more sense to have sex with as many women as possible, regardless of whether or not they looked like last month’s Playmate.

Another hypothesis is based on the idea that most primates have sex with the male entering from behind. This may explain why some female monkeys display elaborate rear-end advertising. In humans, goes the argument, breasts became larger to mimic the contours of a woman’s rear.

We think both of these explanations are bunk! Rather, there’s only one neurological explanation, and it has to do with brain mechanisms that promote the powerful bond of a mother to her infant.

When a woman gives birth, her newborn will engage in some pretty elaborate manipulations of its mother’s breasts. This stimulation sends signals along nerves and into the brain. There, the signals trigger the release of a neurochemical called oxytocin from the brain’s hypothalamus. This oxytocin release eventually stimulates smooth muscles in a woman’s breasts to eject milk, making it available to her nursing baby.

But oxytocin release has other effects, too. When released at the baby’s instigation, the attention of the mother focuses on her baby. The infant becomes the most important thing in the world. Oxytocin, acting in concert with dopamine, also helps imprint the newborn’s face, smell and sounds in the mother’s reward circuitry, making nursing and nurturing a feel-good experience, motivating her to keep doing it and forging the mother-infant bond. This bond is not only the most beautiful of all social bonds, it can also be the most enduring, lasting a lifetime.

Another human oddity is that we’re among the very rare animals that have sex face-to-face, looking into each other’s eyes. We believe this quirk of human sexuality has evolved to exploit the ancient mother-infant bonding brain circuitry as a way to help form bonds between lovers.

When a partner touches, massages or nibbles a woman’s breasts, it sparks the same series of brain events as nursing. Oxytocin focuses the brain’s attention to the partner’s face, smell, and voice. The combination of oxytocin release from breast stimulation, and the surge of dopamine from the excitement of foreplay and face-to-face sex, help create an association of the lover’s face and eyes with the pleasurable feelings, building a bond in the women’s brain.

So joke all you want, but our fascination with your breasts, far from being creepy, is an unconscious evolutionary drive prompting us to activate powerful bonding circuits that help create a loving, nurturing bond.

My only question is: Then why aren’t women as fascinated as men with other women’s breasts? Or are they?

February 15, 2013

Scientist on a Pub Crawl

I’m at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, where I just heard one scientist wondering aloud how to bring science directly to the general public. It seems to be a running theme of this year’s meeting, with an “America’s Scientist Idol” program and another called “Bad Presenter Bingo 2.0.” And it reminded me of a story told by a sea-bird biologist named Julia Parrish.

She’s a college professor at the University of Washington and, at first glance, looks the part—thin, with a long neck, pale, freckled skin, reddish hair pulled back, and the corners of her mouth drawn slightly down, as if you are about to earn a B plus in Life 101 if you don’t shape up now. Asked to give a talk on sea birds at a venue in the coastal city of Everett, Washington, she arrived at the address on the appointed day and found herself in a dive inhabited by “people who at 4 p.m. had obviously had more than their first drink.” She was starting to think C minus.

But at the appointed hour, about 20 people gathered around, drinking beer and eating nachos, and Parrish got up on the dingy carpeted stage normally reserved for bar bands doing covers of Journey’s greatest hits. Parrish talked about sea birds, and one man in the audience, a retired gillnet fisherman, mentioned a study he had helped work on years before. It turned out Parrish had designed that study, and from that point on, everything was copacetic. People were genuinely interested in her work. They asked good questions. Their inner Jane Goodalls, that childhood sense of being in love with the world, inched back toward the surface. At the end, the bartender announced that he had “something to say about natural history.” Just a week earlier, a mountain beaver had inexplicably made its way into the city, ending up in this very bar. It ended badly for the beaver, and the bartender went to his refrigerator to retrieve the evidence. Then Parrish and her audience gathered around to commune over the cadaver, sipping their beers and chatting about sea birds.

Maybe it wasn’t quite T.H. Huxley delivering his lectures to working men on the new science of evolution. It certainly wasn’t the contemplation of nature at its prettiest or most perfect. But as an instance of how to reach out and make natural history matter for ordinary people who deserve to know, it was a very nice start.

Shut the Damned Door! Those Are Dragons Out There

This comes in from CBS News by way of photographer Mark Moffett. (He and I have been sometime-colleagues at National Geographic, and once spent a couple of weeks together hunting tarantulas in Peru.):

Last year we visited the office HQ at Komodo National Park, dragons resting outside the open door, and noticed that the head ranger sitting at the front desk had a badly scarred leg and arm. Dragons had swarmed into the office two years before and tried to kill him. We were amazed he was still working there, at the same desk in the same room. Guess what…

Komodo dragon wanders into office, attacks two wildlife park employees in IndonesiaCBS NEWS–JAKARTA, Indonesia A park official says two people have been hospitalized after being attacked by a giant komodo dragon that wandered into the office of a wildlife park in eastern Indonesia.

An official at Komodo National Park, Heru Rudiharto, said Wednesday the 6 1/2-foot-long komodo dragon attacked a park ranger after walking into the office on Tuesday. It then attacked another park employee who came to help him. Both were badly bitten and were evacuated to a hospital on Bali Island.

Endangered Komodo dragons can grow longer than 10 feet. Fewer than 4,000 are believed to be alive. They are found in the wild primarily on the eastern Indonesian islands of Komodo, Padar and Rinca.

According to National Geographic, komodo dragons “will eat almost anything, including carrion, deer, pigs, smaller dragons, and even large water buffalo and humans.”

In 2009, two Komodo dragons mauled a fruit-picker to death in eastern Indonesia.

© 2013 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

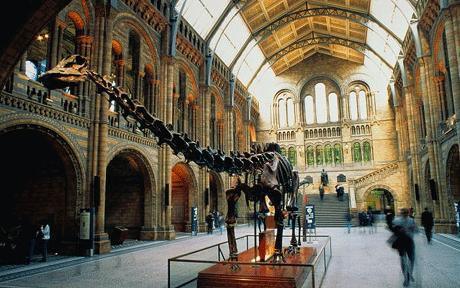

Happy Birthday to a Great Museum

The main hall of the Natural History Museum, London

Being a Yank, and in the U.S. Eastern time zone, I am a little late to the party. But today’s the birthday of one of the world’s greatest museums, in London, and it’s the 260th, if I have my math right. Here’s what I wrote about the great event in my book The Species Seekers:

The British Museum had been founded in 1753, largely based on the collections of the virtuoso par excellence, Sir Hans Sloane. Sloane, a London physician and naturalist, had acquired thousands of specimens, from tiny invertebrates on up to elephant tusks, often describing them in meticulous scientific detail. In death, he gave his carefully chosen trustees the task of making the nation take charge of the collection—and pay a high price for the privilege.

“He valued it at fourscore thousand,” Horace Walpole, who was one of the trustees, carped to a friend, “and so would anybody who loves hippopotamuses, sharks with one ear, and spiders as big as geese! It is a rent-charge to keep the foetuses in spirit! You may believe that those who think money the most valuable of all curiosities will not be purchasers.”

But the trustees shrewdly threatened to sell the collection abroad, and nature mattered enough to national pride that Parliament soon agreed to a £20,000 purchase price, establishing the museum in House,an elegant seventeenth-century mansion in the heart of London. Sloane’s bequest would in time give rise not just to the British Museum, but to the British Library, and the Natural History Museum, London. It was a handsome legacy, though perhaps secondary to the result of a collecting trip in Jamaica, on which he also invented chocolate milk.

But time is harsh and memory mostly fickle. In the first part of the nineteenth century, 70 years after Sloane’s death, Bloomsbury was one of London’s more fashionable neighborhoods. The Bloomsburians liked to promenade in the handsome gardens on the north side of Montagu House. And William Leach seems to have taken equal pleasure in annoying them. “He despised the taxidermy of Sir Hans Sloane’s age, and made periodical bonfires of Sloanian specimens,” Edward Edwards wrote, in his 1870 Lives of the Founders of the British Museum. “These he was wont to call his ‘cremations.’” Unfortunately for his neighbors, “the attraction of the terraces and the fragrance of the shrubberies were sadly lessened when a pungent odour of burning snakes was their accompaniment.”

The taxidermy of the Sloane bequest was probably no worse than in other natural history collections of its day. Rot, insects, careless handling, and other hazards were the common fate of specimens everywhere. Even as Parliament was voting to purchase new specimens in 1823, a writer complained in the Edinburgh Review that those the British Museum already owned were “mouldering or blackening in the crypts of Montagu House, the tomb or charnel-house of unknown treasures,” where moths and beetles were “busily employed amid the splendours of exotic plumage, or roaring through the fur of animals.”

February 13, 2013

The Romantic Moth

Moths do it. (Photo: Raiwen)

This photo caught my eye, on the eve of Valentine’s Day. I’m maybe leaping to a conclusion that these lovely creatures are having sex. It’s possible, I suppose, that the male is just hanging on afterward for a tiresome interlude of mate-guarding. But the species is named Amata alicia, which in my high school Latin translates as “the beloved Alicia.” So I am going with romance.

The photo, by Raiwen, was taken in grassland, in the Sudano Guinean Tree Savanna Region, Moyenne Guinée, Guinea, West Africa. It’s part of a Field Guide to the Moths of Africa on Flickr

February 11, 2013

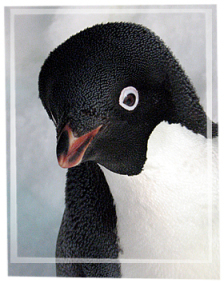

The Polymorphous Perversions of Penguins

Excitable, slightly confused

Sometimes, it seems, penguins are not all that cute:

It was the sight of a young male Adélie penguin attempting to have sex with a dead female that particularly unnerved George Murray Levick, a scientist with the 1910-13 Scott Antarctic Expedition. No such observation had ever been recorded before, as far as he knew, and Levick, a typical Edwardian Englishman, was horrified. Blizzards and freezing cold were one thing. Penguin perversion was another.

Worse was to come, however. Levick spent the Antarctic summer of 1911-12 observing the colony of Adélies at Cape Adare, making him the only scientist to this day to have studied an entire breeding cycle there. During that time, he witnessed males having sex with other males and also with dead females, including several that had died the previous year. He also saw them sexually coerce females and chicks and occasionally kill them.

Levick blamed this “astonishing depravity” on “hooligan males” and wrote down his observations in Greek so that only an educated gentleman would understand the horrors he had witnessed.

February 10, 2013

Polio: The Hidden Cost of the Hunt for Bin Laden

During the search for Osama bin Laden, the CIA made a mistake that continued last week to have tragic repercussions.

The mistake happened in March 2011 when CIA investigators set up a sham vaccination program in the Abbottabad neighborhood where they suspected the Al Qaida leader was in hiding. The idea was to get DNA from the children in the bin Laden compound to see if it matched the DNA of a bin Laden sibling who had died in Boston.

As an inadvertent result, Muslim extremists regard any vaccination program as some kind of Imperialist plot, no matter that it actually protects the health of their children. In December, extremists executed nine polio vaccination campaign workers in Pakistan. And last week, the same thing happened in Nigeria. The victims in both cases were mostly women.

But we may all eventually be the victims.

There are windows of opportunity for eradicating epidemic diseases, and the dismaying thing is that these windows can close. Tuberculosis was on the verge of eradication in the last decades of the twentieth century. But the delayed and inadequate response to AIDS gave the disease fresh breeding ground, in the lungs of patients with impaired immune systems. So tuberculosis is now resurgent, with 8.7 million new cases and 1.4 million deaths per year.

It’s increasingly likely the same will happen with polio. The effort to eradicate the disease has reduced incidence of polio to just three countries–Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan–and the number of cases to just 200 a year worldwide. But getting there costs $1 billion a year. If World Health Organization cannot keep up the pressure, then the computer models say there will be 200,000 cases 10 years from now. “It’s either going to zero,” says a WHO analyst, “or it’s going to come all the way back.”

Given the devastation polio can cause, the CIA investigators hunting bin Laden may have cost us far more than they gained.

Here’s a report from The New York Times:

In a roundabout way, the C.I.A. has been blamed for the Pakistan killings. In its effort to track Osama bin Laden, the agency paid a Pakistani doctor to seek entry to Bin Laden’s compound on the pretext of vaccinating the children — presumably to get DNA samples as evidence that it was the right family. That enraged some Taliban factions in Pakistan, which outlawed vaccination in their areas and threatened vaccinators.

Nigerian police officials said the first shootings were of eight workers early in the morning at a clinic in the Tarauni neighborhood of Kano, the state capital; two or three died. A survivor said the two gunmen then set fire to a curtain, locked the doors and left.

“We summoned our courage and broke the door because we realized they wanted to burn us alive,” the survivor said from her bed at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital.

About an hour later, six men on three-wheeled motorcycles stormed a clinic in the Haye neighborhood, a few miles away. They killed seven women waiting to collect vaccine.

Ten years ago, Dr. Larson said, she joined a door-to-door vaccination drive in northern Nigeria as a Unicef communications officer, “and even then we were trying to calm rumors that the C.I.A. was involved,” she said. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars had convinced poor Muslims in many countries that Americans hated them, and some believed the American-made vaccine was a plot by Western drug companies and intelligence agencies.

Since the vaccine ruse in Pakistan, she said, “Frankly, now, I can’t go to them and say, ‘The C.I.A. isn’t involved.’ ”

February 7, 2013

Russell Baker on the Denatured American

Feral cats in Baltimore (Photo: Vincent J. Musi)

I am kind of thrilled(because, honestly, I thought he was dead) to see that Russell Baker, my favorite columnist of decades past, has a nice review in the New York Review of Books. It’s about former Wall Street Journal reporter Jim Sterba’s book Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards into Battlegrounds. Baker holds it up between thumb and forefinger for an examination that does not exactly amount to an endorsement. Here’s a sample:

This kinder, softer American, Sterba notes, has only a remote relationship with the natural world he inhabits. Over a span of some four hundred years Americans necessarily cultivated a close grasp of nature’s laws and whims in order to survive the cruelty of a primordial wilderness, and to level forests, make land productive, and become competent at hunting, fishing, trapping, and animal husbandry.

Now, in little more than a single generation, this long relationship with nature has withered in a culture that finds Americans giving themselves up to the indoor ease of the technological way of life. Today’s average American spends most of the day indoors or inside an automobile traveling some hellish commuter road between workplace and home. Experience of his own natural habitat comes largely from watching beautifully photographed films on television. In Sterba’s word, he has become “denatured.”

Denaturing has produced an unrealistic and somewhat sentimental view of woodland creatures, which, as Sterba construes the situation, is one reason so many seem to feel they can trespass in our gardens with impunity.

His book, written with considerable charm and more wit than commonly found in works that deal with ecosystems, includes extensive and often entertaining treatments of such common nuisances as beavers, Canada geese, and feral cats, as well as various animal support lobbies that make life miserable and sometimes dangerous for wildlife control agents. For the denatured reader, there is a wealth of useful statistics.

Is it generally known, for example, that the beaver is the largest rodent in North America, that the adult male may be four feet long from nose to tail tip and weigh as much as sixty pounds? Or that the giant variety of Canada goose, weighing ten to twenty pounds, does not migrate but likes to settle in groups of hundreds, sometimes thousands, on golf courses and public parklands where, with their distinctively hyperactive digestive systems, they must void their bowels approximately fives times an hour? Or that the population of feral cats is thought to be somewhere between 60 and 100 million, that they have human supporters—even “national cat protection groups”—that wage bitter struggles against songbird lovers who see the wild felines as a threat to the future of beauty on the wing?

Sterba refers to human champions of this animal or that as “species partisans.” Though sympathetic to their devotion to animals and their care for the environment, he clearly disapproves of some of the tactics they employ in pursuit of their high-minded objectives. Officials of an upstate New York village planning to rid the community of an infestation of Canada geese find themselves, for example, confronted by TV crews summoned to cover a protest against a pending “goose Holocaust.” After sharpshooters are hired by Princeton, New Jersey, to cull its deer population, “the mayor’s car was splattered with deer guts and the township animal control officer began wearing a bulletproof vest after finding his dog poisoned and his cat crushed to death.” People “denatured” from their own habitat tended to treat the environment and its other inhabitants in mindless ways, unintentionally and often with the best of intentions.

Early environmentalists, like Thoreau, wrote of a landscape despoiled by ignorance and exploitation, and this narrative of loss through human meddling—the idea of “man the despoiler,” in Sterba’s phrase—still ran strongly through the last century’s environmentalist culture. Sterba writes that this idea led to the notion that the natural world “was a benign place” where wild creatures lived harmoniously among themselves, and only man was vile:

This idea was in striking contrast to the amorality of a Darwinian nature that was indifferent and random, its creatures living in a world of predators and prey, struggling to eat, reproduce, and survive. In a benign natural world, wild animals and birds not only got along with one another but were often portrayed as tame and peaceable, with human habits and feelings.

This, in exaggerated form, was the world of faux nature packaged for delivery to people who wanted to believe that animals were just like us.

Bambi and Lassie are two of the best-known practically human specimens that warm the popular heart. Those who seek something closer to Darwinian reality may prefer Bugs Bunny.

New Cure for a Nasty Tropical Disease

Leish

Leishmaniasis is one of the more dreaded hazards of traveling in the tropical wilderness. It can turn up months after a trip, causes disfiguring skin lesions, and, worst of all, requires treatment with heavy metals. The cure is said to be a lot like chemotherapy. A photographer I have worked with was out of commission for months as a result.

Traveling last year in a remote corner of Suriname, I was acutely aware of the threat. I treated my tent, my pants, and my socks with pyrethrin beforehand. But the local Indians had the lesions, and the sandflies that transmit “leish,” as it is unaffectionately known, were everywhere. Out on the trail one night, I asked a companion “What are all these gray things in front of my face?” They were a constant moving cloud. “Sandflies,” he replied. (The companion, naturalist and author Piotr Naskrecki, was not exactly blasé about the threat. But he got bitten so often that he once took a macro photograph of a sandfly working on his own arm.)

Luckily, nobody on the trip developed “leish.” And today the good news comes that there is apparently a much easier cure, using antibiotics:

Feb. 6, 2013 — An international collaboration of researchers from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC), Tunisia and France has demonstrated a high cure rate and remarkably few side effects in treating patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) with an investigational antibiotic cream. CL is a parasitic disease that causes disfiguring lesions, with 350 million people at risk worldwide and 1.5 million new cases annually, including U.S. military personnel serving abroad and the socio-economically disadvantaged in the developing world, especially children.

The results of the research conducted by USAMRMC, the Institut Pasteur de Tunis, the Tunisian Ministry of Health and the Institut Pasteur in Paris were published today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“A simple cream represents a tremendous breakthrough in the way we treat this neglected disease,” said Maj. Mara Kreishman-Deitrick, product manager at the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Development Activity, which leads the advanced development of medical products for the USAMRMC. “Currently, patients must stay in a medical center for weeks to receive toxic and painful treatments. A cream would offer a safe, effective option that patients can apply themselves.”

Phase III study investigators evaluated WR 279,396, a combination of two antibiotics (15 percent paromomycin-0.5 percent gentamicin). In the trial, the topical cream cured the CL lesions in 81 percent of the patients who participated in the clinical trial. Curing the disease was defined as the shrinking of the lesion, regrowth of normal skin and absence of relapse. Adverse events were reported in less than 5 percent of all study groups and were primarily reported as minor reactions at the application site.

A cream containing paromomycin alone (15 percent paromomycin) had a similar cure rate of 82 percent. In the study, only 58 percent of the patients who received a vehicle cream not including antibiotics or other active ingredients saw the lesions cured.

Researchers said they expected parity between the single and combination therapies in this study, which treated CL caused by L. major, a parasitic species common in the Middle East and North Africa. However, they noted that the combination therapy could hold additional promise for global use since early research shows the combination therapy may be effective against the parasitic species found in Central and South America.

The 375-patient trial was sponsored by the USAMRMC and was conducted in partnership with the Tunisian Ministry of Health, the Institut Pasteur in Tunis and the Institut Pasteur in Paris.

Current CL treatments called antimonials contain toxic heavy metals that must be administered either intravenously or injected directly into the lesion. Because of toxicity, many health care providers are hesitant to use them to treat the disease. People who have CL must leave home and work to undergo the standard 20-day course of treatment at a medical center. Public health workers in the developing world see patients resort to home treatments like burning their lesions with battery acid or red-hot machetes, rather than seek out painful and expensive medical treatments. These home remedies also can compound the severity of scarring.

More than 3,000 CL cases have been reported among U.S. service members since 2003. Service members who develop CL often must be evacuated from their posts — at an approximate cost of $35,000 for hospitalization, treatment and lost duty time per service member. WR 279,396 has the potential to become a first-line treatment that service members could apply themselves in the field.

“The research community has tended to overlook CL because it is not deadly, but that doesn’t mean the disease does not have a lifelong impact on patients,” said Professor Afif Ben Salah, principal investigator for the Tunisia study and head of the Medical Epidemiology Department at the Institut Pasteur in Tunis. “Many people experience discrimination in social settings, at work or at school as a result of the disease’s devastating scarring. The stigma takes a serious toll on their education, marriage and employment prospects.”

USAMRMC and Institut Pasteur researchers formed a partnership 10 years ago around their common need for better CL treatments. Human transmission of CL has been seen as far north as Texas and CL affects civilian travelers as well as U.S. service members. In Tunisia, where the Phase III clinical trial was conducted, up to 10,000 new cases are reported each year and more than half of those cases are in children.

“With these results, we are on the verge of being able to provide non-toxic and easy-to-use treatments to the people who need them most, including U.S. service members,” said Col. Max Grogl, director of the Division of Experimental Therapeutics at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. “We are grateful to our international research partners for their dedication to developing a more tolerable CL treatment that will benefit patients around the world.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has designated WR 279,396 as eligible for fast-track review, given CL’s status as a neglected disease. The Fast Track program of the FDA is a process designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of new drugs that are intended to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and that demonstrate the potential to address unmet medical needs. USAMRMC is actively engaged with the FDA to support this review. Additional research also is being planned in Latin America to explore the effectiveness of the topical cream for treating the parasitic species found in the western hemisphere.

Journal Reference:

Afif Ben Salah, Nathalie Ben Messaoud, Evelyn Guedri, Amor Zaatour, Nissaf Ben Alaya, Jihene Bettaieb, Adel Gharbi, Nabil Belhadj Hamida, Aicha Boukthir, Sadok Chlif, Kidar Abdelhamid, Zaher El Ahmadi, Hechmi Louzir, Mourad Mokni, Gloria Morizot, Pierre Buffet, Philip L. Smith, Karen M. Kopydlowski, Mara Kreishman-Deitrick, Kirsten S. Smith, Carl J. Nielsen, Diane R. Ullman, Jeanne A. Norwood, George D. Thorne, William F. McCarthy, Ryan C. Adams, Robert M. Rice, Douglas Tang, Jonathan Berman, Janet Ransom, Alan J. Magill, Max Grogl. Topical Paromomycin with or without Gentamicin for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. New England Journal of Medicine, 2013; 368 (6): 524 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202657

February 6, 2013

Moth Says Pimp My Ride, Drives Robot to Sex

This one really needs a photo, or maybe a cartoon. It’s like a 17-year-old boy with the keys to his Dad’s Mustang out trying to pick up girls. Here’s the report from ScienceDaily:

A small, two-wheeled robot has been driven by a male silkmoth to track down the sex pheromone usually given off by a female mate.The robot has been used to characterize the silkmoth’s tracking behaviors and it is hoped that these can be applied to other autonomous robots so they can track down smells, and the subsequent sources, of environmental spills and leaks when fitted with highly sensitive sensors.

The results have been published 6 February, in IOP Publishing’s journal Bioinspiration and Biomimetics.

The male silkmoth was chosen as the ‘driver’ of the robot due to its characteristic ‘mating dance’ when reacting to the sex pheromone of the female. Once the male is stimulated by the pheromone it exhibits a distinctive walking pattern: straight-line and zigzagged walking consisting of several turns followed by a loop of more than 360°.

Lead author of the research, Dr Noriyasu Ando, said: “The simple and robust odour tracking behaviour of the silkmoth allows us to analyze its neural mechanisms from the level of a single neuron to the moth’s overall behavior. By creating an ‘artificial brain’ based on the knowledge of the silkmoth’s individual neurons and tracking behavior, we hope to implement it into a mobile robot that will be equal to the insect-controlled robot developed in this study.”

The researchers, from the University of Tokyo, attached the silkmoth to a free-moving polystyrene ball at the front of the robot which was used for overall control, much like the ball in a computer mouse.

Two 40 millimetre fans were attached at the front to divert the pheromone-containing air to the on-board moth — the researchers believe the fans are comparable to the wings of the silkmoth that flap to generate air flow across its antennae.

A 1800 millimetre wind tunnel was used in the experiments; the pheromone and robot were placed at opposite ends. Fourteen silkmoths were used in the study and all of them were able to successfully guide the robot towards the source.

The researchers also introduced a turning bias to the experiments, changing the power of one of the robot’s two motors so it veered towards one side when moving. This put the silkmoth into an extraordinary situation and required it to adapt and change its behaviour.

“The best way to elicit adaptive behaviours of insects is to put them into extraordinary situations. The turning bias in our study is analogous to a situation in which we try to ride unbalanced bicycles. We need training to ride such bicycles smoothly but the silkmoth overcomes the situation with only simple and fast sensory-motor feedbacks,” said Dr Ando. It is important that the chemical sensors attached to a potential robot have a short response and processing time when tracking down odours continuously, which is why the researchers also investigated the effect of a time delay between the movement of the silkmoth and the response of the motor.

“Most chemical sensors, such as semiconductor sensors, have a slow recovery time and are not able to detect the temporal dynamics of odours as insects do. Our results will be an important indication for the selection of sensors and models when we apply the insect sensory-motor system to artificial systems,” continued Dr Ando.