Richard Conniff's Blog, page 77

March 7, 2013

The Face of Happiness

Happy Jack, happy Clare

Josie Glausiusz, with whom I worked at the old Discover Magazine, has a nice piece about the facial expression of joy. It appears today at The Last Word on Nothing, a blog run by another friend, Ann Finkbeiner:

I’ve often thought that old books – both the classics and the more obscure tomes that one finds tucked away in dusty old bookshops – deserve their own reviews. Some are beautifully written but often ignored. Others are just plain weird, but worth a look (and a laugh). So here goes with my first “really old book review”: Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published in 1872.

As biologist Edward O. Wilson explains in his introduction to the work – published in So Simple a Beginning: The Four Great Books of Charles Darwin, “The Expression of Emotions” is both an “old-fashioned descriptive treatise” and “rich and accurate enough in interpretation to have served as part of the foundation of modern psychology.” Emotions are instincts that have evolved via natural selection, Darwin claimed, serving as communication signals that enable individuals to survive in complex societies.

Since they are inborn, such expressions should be found consistently in different societies throughout the world. So Darwin drew upon his own observations of the indigenous inhabitants of the Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America, as well as accounts of world travelers to southern Africa, India and Australia. He gained insights from earlier thinkers and writers from Homer to Shakespeare, and the book is liberally dotted with entertaining quotations.

“The Expression of Emotions” is a fat tome divided into chapters describing every emotion from dejection to sulkiness, surprise, horror, shyness and blushing, anger, disgust, patience and pride. I’ll choose, however, to focus on my favorite chapter: “Joy, High Spirits, Love, Tender Feelings, Devotion.” As Darwin notes in the opening to the chapter, “Joy, when intense, leads to various purposeless movements–to dancing about, clapping the hands, stamping & c., and to loud laughter [...] We clearly see this in children at play, who are almost incessantly laughing.”

He discusses in detail the physical movements and physiological changes that occur when we laugh; thus: “During excessive laughter the whole body is often thrown backward and shakes, or is almost convulsed; the respiration is much disturbed; the head and face become gorged with blood, with the veins distended; and the orbicular muscles are spasmodically contracted in order to protect the eyes. Tears are freely shed.”

Most moving are Darwin’s tender observations of the first smiles of his own children. (Together with his wife and cousin Emma Wedgewood, he had ten of them, and was a devoted father.) At the age of 45 days, one of his infants, “being in a happy frame of mind, smiled; that is, the corners of the mouth were retracted and simultaneously the eyes became decidedly bright.” Similarly, affection, “a pleasurable sensation,” “generally causes a gentle smile and some brightening of the eyes.” A strong desire to touch the beloved person is commonly felt, “hence, we long to clasp in our arms those whom we tenderly love.”

Not every expression of affection is universal, Darwin observed. Europeans are accustomed to kissing as a mark of affection, yet the practice is unknown “with the New Zealanders, Tahitians, Papuans, Australians, Somals of Africa, and the Esquimaux.” The desire for close contact with a loved one is so innate, however, that “in various parts of the world, kissing is replaced “by the rubbing of noses, as with the New Zealanders and Laplanders, [or] by the rubbing or patting of the arms, breasts, or stomachs.” Perhaps that’s why, when Darwin asked a four-year-old child to describe what was meant by being in good spirits, the child replied, “It is laughing, talking, and kissing.” It would be difficult, Darwin concluded, “to give a truer and more practical definition.”

Silent Spring for a Celebrated Bird

Gunnison’s sage grouse (Photo: Joel Sartore)

This one’s worth reading, on the impending loss of one of America’s more spectacular birds. It’s by John W. Fitzpatrick of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, and appears in today’s New York Times:

SEVERAL springs ago some friends and I arose before dawn in Moab, Utah, to witness the sunrise mating dance of the Gunnison sage grouse: a surreal display of nine ornately plumed, chicken-size birds tottering about amid the sagebrush like windup toys, fanning their spiky tails and uttering a magical sound — “pop … pop-pop!” — as they thrust yellow air sacs out of their snow-white chests.

Now as I look back, I realize I might have been inadvertently paying my last respects. For the Gunnison sage grouse, only recently known to science, is going extinct, right before our eyes.

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has a chance to stop this by listing this bird as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, and I strongly encourage the agency to do so immediately.

The Gunnison sage grouse received its common name in the year 2000, after several astute scientists recognized that its long crown plumes and elaborate mating display were completely different from other sage grouse. It was the first new bird species to be described in continental North America in a century, and it was already in trouble, its range having almost entirely shrunk to within the Gunnison Basin of western Colorado.

Today, fewer than 5,000 of these birds remain, and they are rapidly dwindling. They are split into seven genetically isolated populations in Colorado, one of which includes a tiny group in adjacent eastern Utah. The species is now in danger of local population collapses, as each population edges closer to an extinction vortex. The likely loss of genetic variability would reduce fertility and survival, limit the numbers of new grouse and in turn make inbreeding even worse. As these insular populations become ever smaller, random events — one storm, or even an especially savvy coyote — have greater probability of wiping them out.

The federal Endangered Species Act was created specifically for situations like this, and it has repeatedly proved effective for stabilizing, and even recovering, species threatened by forces we understand and can reverse. The bald eagle, peregrine falcon, California condor, whooping crane, Kirtland’s warbler and the golden-cheeked warbler all have benefited from scientifically designed, federally supported regulations and recovery measures leading to steadily growing populations. For example, the number of condors, North America’s largest bird, had dropped to an estimated 25 to 30 birds in the 1970s; today, thanks to aggressive conservation efforts, there are now about 400 of these condors; slightly more than half live in the wild.

Some private landowners and energy companies have protested listing the Gunnison sage grouse as endangered, fearing that will result in federally imposed limits on how they use their land within the 1.7 million acres the agency has proposed as critical habitat. State officials in Utah and Colorado have generally sided with the landowners, citing the importance of encouraging voluntary conservation measures in these fiercely independent ranching communities.

Such cooperation is providing hope for another sage-grouse species, the greater sage grouse, whose numbers are also declining. Ranchers in 11 Western states are adopting sustainable grazing systems that promote healthy sagebrush plant communities and create habitat. But the Gunnison sage grouse’s situation is far more dire, as its tiny populations face continued pressure from conversion of sagebrush to irrigated agriculture and livestock grazing, residential development, expansion of roads and power facilities, invasive plants like cheatgrass and human-altered fire patterns.

Efforts by state agencies and private landowners to stabilize Gunnison sage grouse populations have failed. The prolonged drought across the western United States is further depressing reproductive output, and we are entering our last possible period in which emergency actions could save this species.

In 2006 the Fish and Wildlife Service declined to place the Gunnison sage grouse on the endangered species list after concluding that its estimated population of about 5,700 had remained stable over the previous 10 years, a finding that was challenged by many biologists. In 2010, in response to a lawsuit, the agency reversed itself and began the process of placing the bird on the endangered species list. The public comment period on this proposal closes on Tuesday.

It is urgent that the Gunnison sage grouse be listed as an endangered species immediately and that a federally financed recovery team of biologists, state officials, local conservation groups and landowners expedite efforts to halt the imminent extinction of this remarkable bird. Possible actions include establishing or expanding well-managed habitat preserves in all core populations, moving individuals to promote genetic exchange, and strategically restoring sage habitat to link the now-isolated populations.

The Gunnison sage grouse is an emblematic species for a uniquely American ecosystem, every bit as worthy of investment in its preservation as our finest man-made treasures. Future generations will marvel at the Gunnison sage grouse, as I did on that cool spring morning several years ago. But only if we save it today.

March 4, 2013

Fraudulent Food Labeling: It’s Not Just the Fish.

Snacking on mountain zebra?

It’s amazing, and sometimes dismaying, what you can find out with DNA. We all know that the fish being sold by most retailers and restaurants may not be as labeled: They price it as red snapper, but it’s really just tilapia.

Now it turns out the same thing may be happening with at least one form of red meat.

When I travel in southern Africa, I routinely pick up a bag of biltong, dried wild meat, to snack on as I drive. It’s usually labeled wildebeest, kudu, or even giraffe. But now it turns out it may be something entirely different, even including an endangered species. Here’s the report:

Want to know what you are eating? DNA barcodes can be used to identify even very closely related species, finds an article published in BioMed Central’s open access journal Investigative Genetics. Results from the study show that the labelling of game meat in South Africa is very poor with different species being substituted almost 80% of the time.

In South Africa game meat biltong (air dried strips) is big business with over 10,000 wildlife farms and is supplemented by private hunting. This meat is considered to be ‘healthier’ than beef because it is lower in fat and cholesterol and perceived to be lower in additives.

Using mitochondrial COI DNA barcoding and cytb sequencing, researchers analysed samples of game meat from supermarkets, wholesalers and other outlets and compared them to known samples and library sequences. From 146 samples over 100 were mislabelled.

All the beef samples were correct, but for the most badly labelled case 92% of kudu was a different species. Only 24% of springbok and ostrich biltong was actually springbok or ostrich. The rest was horse, impala, hartebeest, wildebeest, waterbok, eland, gemsbok, duiker, giraffe, kangaroo, lamb, pork or beef. Worryingly one sample labelled zebra was actually mountain zebra, a ‘red listed’ species threatened with extinction.

Maria Eugenia D’Amato from the University of the Western Cape commented, “The delivery of unidentifiable animal carcasses to market and the general lack of regulations increases the chances of species mislabelling and fraud. This has implications for species safety but also has cultural and religious implications. This technique is also able to provide new information about the identity of animals and meant that we found several animals whose DNA had been misidentified in the scientific libraries.”

Maria E D’Amato, Evguenia Alechine, Kevin W Cloete, Sean Davison and Daniel Corach. Where is the game? Wild meat products authentication in South Africa: a case study. Investigative Genetics, 2013; (in press) [link]

March 1, 2013

Name That Dancin’ Ant

I’ve written here before about to species now known only by their cumbersome scientific names.

Now there’s a chance to do it for an American species. Submit your flights of fancy at yourwildlife.org

February 25, 2013

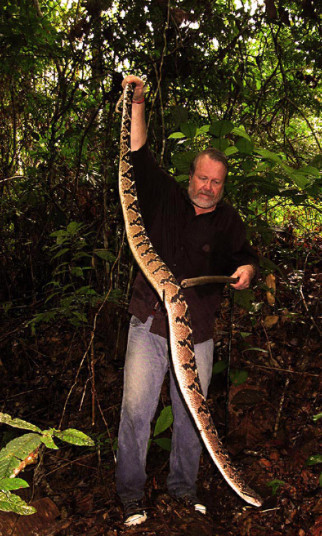

Is a Monster Snake in Hand Worth Two in the Bush?

Bill Lamar and a live bushmaster in the rain

Since we seem to be on the topic of doing crazy things with snakes, take a look at this photo from herpetologist Bill Lamar. One more thing to give us all nightmares. He and I once traveled together on a National Geographic assignment about tarantulas. (You can read about it in my book Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time. Correction: It’s in my book Spineless Wonders, now out of print, but I am working on an ebook edition.) I vividly recall a dismal rainy night that we spent about 45 kilometers outside Iquitos, Peru, digging up tarantulas in a downpour.

When we got back to our truck, it would not start again, and we spent that night in and around it with assorted live tarantulas, which seemed utterly innocuous by then. But Lamar had also collected a live coral snake in a clear plastic bag, which took some getting used to. All night people woke up from their bad dreams to ask, “Donde es el naca naca?” or “Where’s the damned coral snake?”

We tied the bag to the handle over the passenger door, where the entomologist found the direct eye contact disconcerting, then tucked it into the glove compartment, until someone concluded that the glove compartment probably had not been designed to be snake-tight. Then we heaved it with considerable relief onto the muddy road outside, until it occurred to us that we might now step on it in the course of our nocturnal wanderings.

But seeing this photo, I am just glad now that he did not find a bushmaster that night instead.

February 24, 2013

Black Mamba Bite: The Back Story

The model (a black mamba) gets snappish with the photographer

There’s been a lot of buzz on the internet suggesting that photographer Mark Laita’s image of a black mamba biting him on the calf is just a set-up, a bid to publicize his book Serpentine, due out next week. So I contacted him for further details and he quickly phoned me with the story.

“It looks like a set-up,” he said, “because who the hell would stand there with a black mamba biting his leg and take a photo of it? The whole thing seems preposterous.” But it has also become a distraction and an embarrassment, he said, because everybody is talking about the black mamba bite instead of the book. “The whole thing is stupid, and it makes me look like a reckless jackass, which I’m not.”

It happened when he was photographing snakes at the home of a leading collector, he said. With other venomous snakes, he had taken all the usual precautions. Because the king cobra is aggressive and fast, for instance, he photographed that snake completely enclosed in a plexiglass box. With the spitting cobra, he wore a mask, long sleeves and gloves to keep off the venom.

But when it was time to photograph the black mamba, the collector “was handling him like you would a boa. He was a really calm, cool snake. An old snake, not a young, excitable one.”

Laita said he wore shorts because the movement of pants legs might have startled the snake, and also because snake handlers told him “the worst thing is when it climbs up your pants leg.” (O.K., I think we can all agree on that one.)

Laita proceeded to make the kind of photographs that appear in the book, on a black background, to reveal the texture and color and shape of the snake. Afterward, the mamba calmly started to circle around his foot and Laita asked the collector to take his studio camera and hand him a point-and-shoot. Then he began rattling off 20 or 30 photographs, at which point the collector reached in with the snake hook to draw the mamba away. Instead, the hook bumped into a red photographic cable that was hanging down.

That spooked the snake, which struck.

Laita said he felt nothing at first and wasn’t looking through the viewfinder of the camera, so didn’t actually see what had happened. But after a minute the collector said, “Dude, you got hit.”

“The blood was gushing out” Laita recalled, and I said, ‘Oh, fuck.’ He said ‘How do you feel?’ It had been a minute and I felt fine. ‘How’s your heart? How’s your breathing?’ And I said, ‘I’m not happy at getting bitten by the snake, but I’m fine.’” He still felt that way 20 minutes later. His sock was soaked and his sneaker was filled with blood.

“”Both fangs hit an artery in my calf, like the snake knew what it was doing,” said Laita.

They stopped the bleeding with a paper towel compress held down with a can of Red Bull, he said. There was a big welt around the fang marks. “It looked kind of like a mushroom was growing under my skin.” He did not go to the doctor or the hospital, which the collector said is equipped with black mamba antivenom. Laita said that herpetologists have all told him since then that this was incredibly stupid, because even if you feel fine, “something can happen even seven hours later.” It “hurt like hell that night. It was like being stuck with a couple of push pins.” But that was it.

A reader of my previous post about the incident had suggested “The snake is likely venomoid which entails having the venom glands removed in a pointless surgery that hurts the snakes so that yahoos can have ‘venomous snakes.’” But Laita said this snake had not had its venom glands removed. He figures that an older snake might “bite without injecting venom, to hold it for something it was going to eat, and it obviously wasn’t going to eat me.” Or maybe whatever trace of venom was in the bite got immediately flushed out by the rapid bleeding.

One reason people think the whole incident was a set up, Laita said, was that a British newspaper account incorrectly reported that he did not even noticed he’d been bitten till next day. What he actually told that reporter, Laita said, was that he did not know he had gotten a photograph of being bitten till he was reviewing photos that night. Then he blinked through the 10 or 20 photos of the snake slithering around his leg, and 10 or 20 more of the blood pouring down, and sure enough, right in the middle, “There it was.”

When he got home and told his wife, “She wanted to hit me in the head with a frying pan,” he said. His editor just laughed and said it would be great publicity. “But I just want it to go away and not talk about it any more,” he said.

And I believe him. But I also pointed out that in this case, the old saying seems especially pertinent: “The only bad publicity is an obituary.”

February 23, 2013

Darwin’s Other Dangerous Idea

Today in 1871, Charles Darwin published his Descent of Man. It contained his theory of sexual selection, one of the most important and controversial ideas in our understanding of human and animal behavior. Here’s an excerpt from an article I wrote in 2007 for Men’s Health Magazine:

Charles Darwin is of course best known for his theory that species evolve by natural selection. It holds that nature steadily weeds out unfavorable traits by killing individuals who display them, with the dirty work (or quality control) getting done by predators, natural disasters, accidents, and disease, often with considerable help from stupidity. Last year, for instance, a student writing in the University of Nebraska campus newspaper lambasted seatbelt laws as “intrusive and ridiculous,” then promptly died, unbuckled, on being flung from an SUV in a rollover. For his trouble, he got a Darwin Award, commemorating those “who improve our gene pool by removing themselves from it.” That’s natural selection.

But in his 1871 book The Descent of Man, Darwin proposed that it isn’t enough simply to avoid getting killed. Species also evolve depending on which individuals do better at attracting members of the opposite sex. This may sound obvious. But sexual selection has turned out to be far more quirky and surprising than anyone expected. Among other things, it often rewards stupid male behavior. In fact, sexual selection often puts back the very things natural selection weeds out.

Peahens, for instance, like a peacock with a big tail, precisely because the tail is costly, cumbersome, and makes him more vulnerable to predators. Is this because she wishes, once their little romantic interlude is over, that he would just go away and die?On the contrary, displays that entail high cost or danger impress because only a male with the right stuff could act like that and survive. The destiny of males, it seems, is to walk a fine line between Darwin’s two theories, showing off enough to win the admiration of females, and yet not so much that it gets you killed.

Darwin’s theory of sexual selection put primary importance on the role of female choice. For Victorian readers, that was a sticking point. Female choice challenged an orthodoxy more sacrosanct than the Biblical account of Creation: The idea that males are in charge. Thus the theory of sexual selection languished for the next 100 years, until its rediscovery and resurrection beginning in the 1960s.

How to Get Bitten by a Black Mamba

Southeast Asia’s beautiful pit viper (Trimeresurus venustus)

Photographer Mark Laita has a spectacularly beautiful book of snake photographs, Serpentine, coming out soon. His style of taking the animal out of its environment and into a photographic set allows us to savor the textures and colors of these beautiful creatures.

Here’s what Wired has to say:

“My intention was to explore color, shape and movement, using snakes as a subject, but of course herpetologists will probably enjoy these photographs as well,” says Laita, a Los Angeles photographer known for his stunning studio compositions.

During the making of Serpentine, Laita visited dozens of locations in the U.S. and Central America essentially exporting his studio to zoos, venom labs and to the home and workplaces of breeders and collectors.

“I shot everything from the most venomous — an Inland Taipan — to a harmless garter snake,” says Laita. “As for the most dangerous, though, I would think a king cobra is the most capable of doing serious harm to a human. Very big, fast and angry.”

But along the way, Laita also managed to get bitten by a black mamba, a highly venomous African species. Apparently, he managed to survive. But check out the photo, which tells you something about studio photographers: Is this really how you want to dress when working close up with a black mamba?

The model (a black mamba) gets snappish with the photographer

February 21, 2013

Score Another Round for Mosquitoes

The first time I used the insect repellent DEET while reporting a story was in the late 1980s, in the rain forest in eastern Peru. I remember it because laptop computers were a new phenomenon then. They typically cost about $3500 (about $5600 in today’s money) and a biologist on that trip had boldly brought hers into the field. She also used DEET, generally regarded as the most effective protection against mosquitoes, and thus against malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, and so on. Unfortunately, DEET also melts plastic. She didn’t realize this until the keys on her laptop became gooey as asphalt at noon on a hot summer day.

The first time I used the insect repellent DEET while reporting a story was in the late 1980s, in the rain forest in eastern Peru. I remember it because laptop computers were a new phenomenon then. They typically cost about $3500 (about $5600 in today’s money) and a biologist on that trip had boldly brought hers into the field. She also used DEET, generally regarded as the most effective protection against mosquitoes, and thus against malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, and so on. Unfortunately, DEET also melts plastic. She didn’t realize this until the keys on her laptop became gooey as asphalt at noon on a hot summer day.

So now comes the news that the whole idea of DEET leaves mosquitoes totally bored. After the first few hours of revulsion, they just ignore it and zoom in for the blood meal.

Happily, lower tech methods still work:

Here’s the report from the Public Library of Science:

Feb. 20, 2013 — Mosquitoes are able to ignore the smell of the insect repellent DEET within a few hours of being exposed to it, according to research published February 20 in the open access journal PLOS ONE by James Logan, Nina Stanczyk and colleagues from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK.

Though most insects are strongly repelled by the smell of DEET, previous studies by Logan’s research group have shown that some flies and mosquitoes carry a genetic change in their odor receptors that makes them insensitive to this smell. The new results reported in the PLOS ONE study uncover a response in mosquitoes based on short-term changes, not genetic ones.

“Our study shows that the effects of this exposure last up to three hours. We will be doing further research to determine how long the effect lasts,” says Logan.

In this study, the authors tested changes in responses to DEET in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which are notorious for biting during the day and are capable of transmitting dengue fever. They found that a brief exposure to DEET was sufficient to make some mosquitoes less sensitive to the repellent. Three hours after the exposure, these mosquitoes were not deterred from seeking attractants like heat and human skin despite the presence of DEET. The researchers found that this insensitivity to the smell could be correlated to a decrease in the sensitivity of odor receptors on the mosquito’s antennae following a previous exposure. “We think that the mosquitoes are habituating to the repellent, similar to a phenomenon seen with the human sense of smell also. However, the human olfactory system is very different from a mosquito’s, so the mechanism involved in this case is likely to be very different,” explains Logan.

He adds, “This doesn’t mean that we should stop using repellents — on the contrary, DEET is a very good repellent, and is still recommended for use in high risk areas. However, we are keeping a close eye on how mosquitoes can overcome the repellent and ways in which we can combat this.”

Source: Nina M. Stanczyk, John F. Y. Brookfield, Linda M. Field, James G. Logan. Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes Exhibit Decreased Repellency by DEET following Previous Exposure. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8 (2): e54438 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054438

February 19, 2013

A Microbe to Keel-Haul Troubled Sinuses

Here’s a way to understand the stuffiness and thick nasal congestion of sinusitis: Imagine you are sailing some hulk of a freighter through the Sargasso Sea enveloped in a fog as thick as pillow.

So the latest news from biomimicry fits just right.

Researchers who originally studied a marine microbe with the idea of using it to help strip crud off the hulls of ships have instead discovered that they can use it to clean out troubled sinuses.

Here’s the press release from Newcastle University:

Feb. 18, 2013 — A team of scientists and surgeons from Newcastle are developing a new nasal spray from a marine microbe to help clear chronic sinusitis.

They are using an enzyme isolated from a marine bacterium Bacillus licheniformis found on the surface of seaweed, which the scientists at Newcastle University were originally researching for the purpose of cleaning the hulls of ships.

Publishing recently in PLOS ONE, they describe how in many cases of chronic sinusitis the bacteria form a biofilm, a slimy protective barrier which can protect them from sprays or antibiotics. In vitro experiments showed that the enzyme, called NucB dispersed 58% of biofilms.

Dr Nicholas Jakubovics of Newcastle University said: “In effect, the enzyme breaks down the extracellular DNA, which is acting like a glue to hold the cells to the surface of the sinuses. In the lab, NucB cleared over half of the organisms we tested.”

Sinusitis with or without polyps is one of the most common reasons people go to their GP and affects more than 10% of adults in the UK and Europe. Mr Mohamed Reda Elbadawey, Consultant of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Freeman Hospital — part of the Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust — was prompted to contact the Newcastle University researchers after a student patient mentioned a lecture on the discovery of NucB and they are now working together to explore its medical potential.

Mr Elbadawey said: “Sinusitis is all too common and a huge burden on the NHS. For many people, symptoms include a blocked nose, nasal discharge or congestion, recurrent headaches, loss of the sense of smell and facial pain. While steroid nasal sprays and antibiotics can help some people, for the patients I see, they have not been effective and these patients have to undergo the stress of surgery. If we can develop an alternative we could benefit thousands of patients a year.”

In the research, the team collected mucous and sinus biopsy samples from 20 different patients and isolated between two and six different species of bacteria from each individual. 24 different strains were investigated in the laboratory and all produced biofilms containing significant amounts of extracellular DNA. Biofilms formed by 14 strains were disrupted by treatment with the novel bacterial deoxyribonuclease, NucB.

When under threat, bacteria shield themselves in a slimy protective barrier. This slimy layer, known as a biofilm, is made up of bacteria held together by a web of extracellular DNA which adheres the bacteria to each other and to a solid surface — in this case in the lining of the sinuses. The biofilm protects the bacteria from attack by antibiotics and makes it very difficult to clear them from the sinuses.

In previous studies of the marine bacterium Bacillus licheniformis, Newcastle University scientists led by marine microbiologist Professor Grant Burgess found that when the bacteria want to move on, they release an enzyme which breaks down the external DNA, breaking up the biofilm and releasing the bacteria from the web. When the enzyme NucB was purified and added to other biofilms it quickly dissolved the slime exposing the bacterial cells, leaving them vulnerable.

The team’s next step is to further test and develop the product and they are looking to set up collaboration with industry.

Journal Reference: Robert C. Shields, Norehan Mokhtar, Michael Ford, Michael J. Hall, J. Grant Burgess, Mohamed Reda ElBadawey, Nicholas S. Jakubovics. Efficacy of a Marine Bacterial Nuclease against Biofilm Forming Microorganisms Isolated from Chronic Rhinosinusitis. PLOS ONE, 18 Feb 2013 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055339