Richard Conniff's Blog, page 82

January 2, 2013

The Lure of Long Distances: The Last Frontier

Mars has been an object of colorful speculation ever since the Egyptians first noted its presence in the night sky almost 3500 years ago. Name the first of NASA’s robotic rovers to touch down on the Red Planet and send back detailed close-ups:

a. Curiosity

b. Opportunity

c. Sojourner

d. Asimov

And the answer is:

(c) Sojourner began to explore the Martian landscape on July 4, 1997 , after a voyage of 312 million miles aboard NASA’s Mars Pathfinder . It was named for Sojourner Truth, the abolitionist, whose own great voyage of discovery, on foot, in 1826, covered only 11 miles . But it took her from slavery to freedom.

The Lure of Long Distances: A Quiz

Ancient Polynesian canoe (Herb Kane)

Great journeys have a powerful hold on the human imagination. We love the idea, if only from an armchair, of cutting loose from the comforts of everyday life and venturing into uncharted worlds, with no certain destination, and no guarantee of safe return. In its January issue, National Geographic magazine begins a series of seven quizzes, written by me with help from my wife Karen Conniff, celebrating the spirit of exploration. I’ll post the first round of questions over the next few days, starting with this puzzler:

1. A daring voyage in open canoes across thousands of miles of ocean brought the original settlers to Easter Island. This tiny mid-Pacific “navel of the world” is closest to the longitude of which city?

a. Honolulu, Hawaii

b. Juneau, Alaska

c. Santiago, Chile

d. Moab, Utah

And the answer is

1. (d) Easter Island (109°37′ W) lies almost directly south of Moab, Utah (109°75′ W). The original Polynesian settlers are thought to have reached the island more than 800 years ago after traveling almost 2400 miles from the Marquesas Islands. Curiously, Easter Island is now governed by Chile, 2300 miles to the east (and due south of Boston).

NOTE: Here’s a link for more information about Trans-Pacific voyagers. Thanks for research help to Claire Saravia and Meaghan Mulholland

December 27, 2012

Life Inside Life Inside a Leaf

The travels of a leaf miner (an American species, I think)

I often find myself hating leaf miners, mostly when I am picking spinach or swiss chard, only to find their little paths of destruction winding through the leaves that I had planned to eat for dinner.

For those of you who have not had the pleasure, leaf miners are caterpillars of a tiny, exceedingly flat character, and they meander through the sliver of world inside a leaf gobbling up everything in sight. They are the immature offspring not of any single insect group, but of flies, beetles, moths, and even some wasps. Thus calling them “leaf miners” isn’t really a taxonomic description. It’s behavioral.

In any case, you may find it hard to fathom, at first glance, why someone would travel deep into the war-torn, infrastructure-deficient, bushmeat- and-bribe-happy Democratic Republic of the Congo to discover new leaf miners.

But that’s what researchers at the University of Florida and the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Belgium did in 2008, and it cost them $250 in handouts just to get their luggage out of the airport. They also saw guns everywhere, including bubble-wrapped AK-47s as carry-on luggage on domestic flights. Was it worth it?

Some of their results, including descriptions of 41 new leaf miner species, are just out in Zootaxa. The researchers also have another 100-200 new species from the trip still to be described, according to co-author Akito Kawahara, assistant curator of lepidoptera at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the UF campus.

Despite our image of the Congo forest as a wonderland of gorillas and forest elephants, the researchers saw no large mammals on the trip. They’ve all been hunted out. Even in a national park, said Kawahara, he could hear the gunfire of poachers at night. Maybe they were going after whatever’s left of the birds.

In any case, much of the biodiversity that survives, in the Congo and elsewhere in the tropics, consists of insect life, and it is weirdly wonderful, though not conventionally charismatic.

With the familiar specialist’s love for his subject, Kawahara said that leaf miners “can be extraordinarily beautiful with colorful markings and metallic scales.” But he added: “If you think of a regular caterpillar and then you squished it and shrunk it, that’s what they look like.”

They’re typically just a millimeter thick, and 2-5 millimeters long, and with a microscope you can see right through them, Kawahara told me by phone. You can also see everything that’s going on inside them. One of the gruesome facts of life for all caterpillars is that wasps like to lay their eggs on them, so the larva can hatch, burrow inside, and feed on the living caterpillar, until eventually the adult form bursts out, alien style, and flies off, leaving a husk of dead caterpillar behind. Caterpillars have taken up the leaf-mining way of life partly to escape this wretched fate, and also to avoid more conventional predators.

That may also be the reason for all their meandering inside a leaf. I thought they just wandered back and forth eating whatever happened to be in front of them. But according to Kawahara, parasitic wasps locate their victims even inside a leaf using vibration. They tap-tap-tap till they hear or feel something that sounds like caterpillar. But all those tunnels tend to confuse and delay them. Since the wasps also have their own predators to worry about, they give up after a while and fly off in search of a more rewarding leaf.

The wasps also hunt by sense of smell, and that may explain why leaf miners stash their poop in a sort of toilet inside the leaf: Misguided wasps may end up laying their eggs on something that smells like caterpillar but is in fact a cesspool.

Sad to say, these deceptions don’t always work: “If you look at what is happening inside a leaf under a microscope, it’s just an incredible world,” Kawahara said. “You’ll see a tiny wasp larva living within a caterpillar, and another, even smaller wasp larva living inside that larger wasp larva that is inside the moth larva. It’s a parasitoid of another parasitoid. It really opens your eyes to this incredible, unknown world and makes you think, ‘What is going on here?’ It’s truly amazing.”

Interested? I just checked on Kayak, and it looks like you can book your flight from JFK to Kinshasa for under $1400. With luck, no AK-47s will be included in the price.

SOURCE: Jurate De Prins, Akito Y. Kawahara. Systematics, revisionary taxonomy, and biodiversity of Afrotropical Lithocolletinae (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae). Zootaxa, 2012; 3594

December 19, 2012

Males Show Off for Female Strangers (Duh)

This is going to sound awfully familiar to any woman who has ever watched her otherwise lackluster male partner suddenly brighten up and become debonair when there’s an unattached female around. This account comes from ScienceDaily:

Male birds use their song to dupe females they have just met by pretending they are in excellent physical condition.

Just as some men try to cast themselves in a better light when they approach would-be dates, so male birds in poor condition seek to portray that they are fitter than they really are. But males do not even try to deceive their long-term partners, who are able to establish the true condition of the male by their song.

Researchers at the University of Exeter studied zebra finches to establish how trustworthy birdsong was in providing honest signals about the male’s value as a mate. Singing is a test of the condition of birds because it uses a lot of energy. Fit and healthy birds are thought to be able to sustain a high song rate for longer, making them more attractive to females.

The research team, which included scientists from the Université de Bourgogne in France, looked at short and longer encounters with unknown females, as well as patterns of song around females who were familiar to them.

The team discovered that males in poor condition could “cheat” and vary their song to give a false impression to stranger females. But they did not even try to fool those who knew them, who used song as a reliable test of their underlying qualities. The research is published on December 19 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

This seems a little off to me. If fathering the next batch of young is the ultimate goal, you’d think the male would also want to impress his partner a bit. The article says they partner for life. So it would be interesting to know more about female infidelity to put this male behavior in perspective. One other caveat: I am a little skeptical about studies that seem to confirm our human stereotypes, especially when the researchers reach for glib human analogies. Nothing against glib human analogies, mind you, but that’s my job as a journalist:

Dr Sasha Dall, of the University of Exeter, was involved in the research. He said: “Every man wants to cast himself in a favourable light when he meets an attractive female, and we have shown that birds are no different. But just like many humans, it seems zebra finch males are unable to dupe females who know them well enough. When the birds were in an established relationship, the female could tell the true condition of a male by his song, and judge whether he would make a good father for her next brood.”

Zebra finches are Australia’s most popular finch. They make common pets and are widely used in scientific research. They are particularly easy to keep, and adapt extremely well to their surroundings. For zebra finches, both colour and birdsong are important factors in choosing a mate.

The research was funded through a young researcher prize of the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation for life sciences and a PhD grant, as well as two honorific master grants provided by the Conseil Régional de Bourgogne in France.

The team studied 91 male and 91 female birds from a colony at the Université de Bourgogne and 12 of each gender from a colony at the University of Exeter. The body condition of each of the birds was measured. Scientists then videoed both brief and longer encounters between birds of each gender who were unknown to each other, and patterns of behaviour when they were with their mate, with whom they pair for life. They were also monitored to see if they showed signs of mutual attraction and going on to breed.

In the study, there was no difference in the singing of male single birds in either short or long encounters with unknown females. But, when in front of their partners, paired birds who were in good condition sang at a higher rate than those in poor condition.

Dr Morgan David, who led the research, said: “This is the first study to find evidence that the link between male body condition and birdsong differs depending on the context of the encounter with the opposite sex. It could have significant implications for learning more about the evolution of courtship patterns such as birdsong.”

Source: Morgan David, Yannick Auclair, Sasha R. X. Dall, and Frank Cézilly Pairing context determines condition-dependence of song rate in a monogamous passerine bird

Proc R Soc B 2012 280: 20122177

December 12, 2012

The Last of the Pound-Netters

In the course of reporting on the menhaden fight, I spent a day out on one of the big, industrial-style ships that now dominate the fishery. But I also got a chance to look in on an old-style way of fishing for menhaden that reminded me of the classic Chesapeake waterman in William B. Warner’s book Beautiful Swimmers. My host, Walter Rogers, manages to eke out a living in the same market as ships that harvest tens of thousands of times more fish per day. It clearly isn’t easy, but he does it. Rogers won’t agree with this. But to me this suggests that it’s possible to have a reduced menhaden fishery and actually create more jobs by moving away from the current model of an industrial fishery dominated by a single large company, Omega Protein. Moreover, that model encourages people to become independent small businessmen, not just wage slaves. And that’s something to think on as the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission meets tomorrow to decide the fate of the menhaden:

I headed out of Cockrell Creek before dawn one morning, past Reedville’s restored smokestack, now brightly lighted up against an indigo sky. Walter Rogers, a 48-year-old college-educated father of two, was at the helm of a classic Chesapeake Bay deadrise, the Glenna Fay, 40 feet long, powered by a 1940s Detroit Diesel engine, and with a wooden skiff tagging along behind.

Rogers catches menhaden much as his great-grandfather did, with pound nets. Starting in February, he drives heavy pine poles into the bay bottom, then uses them to arrange his nets into a series of underwater hallways and rooms, divided by chutes. The fish end up in a pound at the end, from which Rogers and a crewman haul them up in a net by hand. It’s hard work, but also beautiful, especially when the sun breaks through the last blue remnants of night and beats a path across the water.

“I love what I do,” said Rogers, and immediately he added, “There are times I hate it. The days when you go out and lose money, or spend money on all that gear.” The regulations. There used to be thousands of pound netters working the Virginia stretch of the Chesapeake, he said. Now it’s down to about 50.

He scooped up a mess of fish in a big net with a handmade cedar handle, cried “Yup!” to signal a man at the winch to help lift the load over the rail of the Glenna Fay. Then he pulled a release cord and the fish showered down like coins into the hold of the boat, till it was shin-deep in menhaden. It looked like the lost age of the Chesapeake Bay watermen, barely hanging on in the twenty-first century, and it was hard to miss the contrast with the big Omega Protein boats.

But Rogers wasn’t buying the role of the artisanal fisherman, or the idea that industrial-scale fishing might be putting him out of business. “Those people on the menhaden boats get vilified as guys with white boots and no teeth,” he said. “But those people are me. They’re working hard, they’re away a lot, they’re doing what they can to feed their families.” For Reedville, that was the only reality that mattered, those 275 jobs. Next to that, all the science and stock assessments were just a heap of meaningless talk.

Then Rogers grimaced and said something that seemed to me to apply about equally to all sides in the war for the future of menhaden: “You’re arguing with people you can’t convince.”

[image error]

December 9, 2012

“That Neglected Cloak of Stillness”

I love this paragraph from a New York times interview with novelist Ian McEwan, about the pleasure of reading poetry. It’s so perfectly phrased, and such a complete, rounded thought that it makes me wonder if these interviews are written, or spoken:

Do you read poetry?

We have many shelves of poetry at home, but still, it takes an effort to step out of the daily narrative of existence, draw that neglected cloak of stillness around you — and concentrate, if only for three or four minutes. Perhaps the greatest reading pleasure has an element of self-annihilation. To be so engrossed that you barely know you exist. I last felt that in relation to a poem while in the sitting room of Elizabeth Bishop’s old home in rural Brazil. I stood in a corner, apart from the general conversation, and read “Under the Window: Ouro Preto.” The street outside was once an obscure thoroughfare for donkeys and peasants. Bishop reports overheard lines as people pass by her window, including the beautifully noted “When my mother combs my hair it hurts.” That same street now is filled with thunderous traffic — it fairly shakes the house. When I finished the poem I found that my friends and our hosts had left the room. What is it precisely, that feeling of “returning” from a poem? Something is lighter, softer, larger — then it fades, but never completely.

December 8, 2012

We Need Some of These Suckers in New York City

O.k., I know that introduced species are a recipe for disaster. Pigeons in New York City, for instance. But this is just so sweet. A catfish from Europe that thinks it’s a freshwater killer whale, and leaps out of the water to seize its feathery prey. Let’s go to the video, showing behavior filmed on the Tarn River in Southwestern France:

Here’s the background:

A new study published in PLoS One has revealed that the Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) is successful at hunting birds on the shore. The research found the catfish was able to catch a pigeon 28% of the time, out of 45 observed beaching behaviors.

The researchers say, “Since this extreme behavior has not been reported in the native range of the species, our results suggest that some individuals in introduced predator populations may adapt their behavior to forage on novel prey in new environments, leading to behavioral and trophic specialization to actively cross the water-land interface.”

Back to the idea of how great these would be in Manhattan, here’s a photo of one Wels catfish, fat, ugly, and with what looks like a cigar in his mouth, just the thing for fitting in on Wall Street.

Back to the idea of how great these would be in Manhattan, here’s a photo of one Wels catfish, fat, ugly, and with what looks like a cigar in his mouth, just the thing for fitting in on Wall Street.

Source: Cucherousset J, Boulêtreau S, Azémar F, Compin A, Guillaume M, et al. (2012) “Freshwater Killer Whales”: Beaching Behavior of an Alien Fish to Hunt Land Birds. PLoS ONE 7(12): e50840. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050840

December 7, 2012

Small Town, Split Reputation (The Oiliest Catch–Part 1)

Heading out of Reedville, past the restored smokestack of an old fish meal factory

The small town of Reedville, Virginia, on the western shore of Chesapeake Bay, is a 1950s, Norman Rockwell sort of place. Bunting hangs from a white picket fence ahead of a holiday weekend, and there’s a tire swing in a front yard. The big, handsome houses on Main Street have wraparound porches and a smattering of gingerbread on the gable peaks.

Reedville is also still a working town. Summer days start around 5 a.m. with the thrum and rumble of heavy diesels as the big fishing boats head out, followed at 5:50 by the whine of the spotter planes taking off. If a fishy smell, or even the occasional stink, wafts across Cockrell Creek from the Omega Protein Corporation’s fish-processing plant—Reedville’s major employer—locals just breathe deeper. They recently raised $350,000 to restore a beloved landmark, the 130-foot-tall smokestack of another fishmeal factory, now defunct.

For almost 140 years, Reedville’s prosperity has depended on one species: the Atlantic menhaden, Brevoortia tyrannus. It’s a modest-looking little fish, generally under a foot in length, with a deeply forked tail and such rich reserves of oil that it’s sometimes called “the soybean of the sea.” A school of them leaves a slick in its wake. Dutch Harbor, Alaska, is the nation’s largest fishing port by tonnage and gets celebrated in “The Deadliest Catch” television series. But Reedville, home of the oiliest catch, comes in second—and gets widely vilified for it.

Menhaden used to be unbelievably abundant on the Atlantic seaboard. When Captain John Smith visited the Chesapeake 400 years ago, he found them “lying so thicke with their heads above the water” that his crew tried to skip a step and “catch them with a frying pan.” New York Harbor, according to a 1679 Dutch travel account, also swarmed with “whales, tunnies and porpoises” as well as with osprey, all feeding on “marsbankers.” (Mossbunker, or bunker, is still a common name for the species.) Harvesting this resource became the business of the menhaden “reduction” industry in the mid-nineteenth century, after a fisherman’s wife in Blue Hill, Maine, figured out how to separate the oil from the menhaden’s flesh. As recently as the 1980s, dozens of reduction plants from Florida to Maine were still at it.

Menhaden used to be unbelievably abundant on the Atlantic seaboard. When Captain John Smith visited the Chesapeake 400 years ago, he found them “lying so thicke with their heads above the water” that his crew tried to skip a step and “catch them with a frying pan.” New York Harbor, according to a 1679 Dutch travel account, also swarmed with “whales, tunnies and porpoises” as well as with osprey, all feeding on “marsbankers.” (Mossbunker, or bunker, is still a common name for the species.) Harvesting this resource became the business of the menhaden “reduction” industry in the mid-nineteenth century, after a fisherman’s wife in Blue Hill, Maine, figured out how to separate the oil from the menhaden’s flesh. As recently as the 1980s, dozens of reduction plants from Florida to Maine were still at it.

But now the menhaden are going bust, according to a highly vocal coalition of scientists, conservationists, and recreational fishermen. Whereas they were once abundant along the entire Atlantic seaboard, the fishery has shrunk to an area from Virginia to New Jersey, and the annual catch has plummeted by almost 80 percent since the 1950s. Omega Protein executives like to point out that the commercial fishery leaves enough menhaden in the water to produce 18.4 trillion menhaden eggs annually. It sounds like a big number, and in theory it’s almost double what’s needed to maintain the species at target levels. But that 18.4 trillion is down from a peak of 117 trillion in 1961. Moreover, something in the process of turning those eggs into grown-up fish has gone badly awry in recent decades. Conservationists say overfishing is the problem, and they liken the collapse of the menhaden to the decimation of the great bison herds and the extinction of the passenger pigeon in the nineteenth century. Three-quarters of the remaining catch now goes to Reedville, which has the East Coast’s last surviving reduction plant.

Hence Reedville’s split reputation. Depending on your point of view, it is a manufacturing center for what has lately become one of the healthiest and most highly prized products on the planet—omega-3 fatty acids in the form of fish meal and fish oil. Or it is the Death Star for marine species on the entire Atlantic seaboard.

Read Bringing in the Catch (The Oiliest Catch–Part 2)

Bringing in the Fish (The Oiliest Catch–Part 2)

At dawn one recent morning, just off Tangier Island in mid-Chesapeake, the start of the day’s fishing felt like a military maneuver, with a fleet of big boats—up to 170 feet in length—milling about and spotter planes circling in a Cessna dogfight overhead. “Can’t get my eye on any color right now,” a pilot drawled over the radio on the Indian Creek, one of Kellum’s boats, a former Navy tug now converted to purse-seine fishing. Menhaden travel in such densely packed schools that they appear as inky splotches on the surface. Spotter pilots become adept at reading the color and the “whips”—or surface splashing—to estimate the number of fish to the nearest 10,000.

Menhaden breed offshore, and the juveniles then make their way into estuaries, with the Chesapeake serving as the most important nursing ground on the Atlantic seaboard by far. Some menhaden overwinter there. Others begin to arrive in May as vast schools of menhaden migrate northward. “I see two or three here this morning,” said the pilot, meaning schools of fish. “They ain’t no whackers, but they’re worth a set.”

A big, open tub of a boat with six crewmen aboard motored away from the Indian Creek. Under direction from the airplane, it dropped a 1,200-pound sea anchor with one end of its purse seine attached and began paying out the rest—900 feet of buoyed rope from which the net drifted down like a curtain. “Steady, steady, steady,” said the pilot, as the boat slowly circled. “Come right around on ‘em. Lookin’ good. Got every bit of it. Now, just like that, go into the sea anchor. Color there is good.”

A big, open tub of a boat with six crewmen aboard motored away from the Indian Creek. Under direction from the airplane, it dropped a 1,200-pound sea anchor with one end of its purse seine attached and began paying out the rest—900 feet of buoyed rope from which the net drifted down like a curtain. “Steady, steady, steady,” said the pilot, as the boat slowly circled. “Come right around on ‘em. Lookin’ good. Got every bit of it. Now, just like that, go into the sea anchor. Color there is good.”

With the net now surrounding the school of menhaden, the crew began drawing in a rope that runs through metal rings along the bottom edge, cinching it closed like a coin purse. The clanking of metal parts mixed with sounds of water sheeting down, men shouting, and the spattering of the fish across the surface as the circle steadily contracted around them.

Men in their oilskins reached over to haul in the net, their faces straining, hair flecked with fish scales. The Indian Creek, which had now pulled alongside, lowered a big vacuum tube down into the seething pocket of fish, and the menhaden came flying up into the fish hold, where the streams of chiller water turned murky red with blood and oil.

Men in their oilskins reached over to haul in the net, their faces straining, hair flecked with fish scales. The Indian Creek, which had now pulled alongside, lowered a big vacuum tube down into the seething pocket of fish, and the menhaden came flying up into the fish hold, where the streams of chiller water turned murky red with blood and oil.

The Indian Creek would sell that day’s catch to the bait trade, mainly for crabbers in the Chesapeake and lobstermen as far north as Maine. But most of the other boats that day were bound for Omega Protein, where 550 million menhaden a year get reduced to fish meal and oil—and ultimately transformed into human food.

Read What’s for Dinner (The Oiliest Catch–Part 3)

What’s for Dinner? (The Oiliest Catch–Part 3)

The modern battle over menhaden began one day in 1997, when a recreational fisherman named Jim Price turned up at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources with a malnourished and diseased striped bass he had caught. A pathologist there speculated that stripers may have gotten “decoupled from their prey,” and Price, who has no scientific training, thought, “What the hell?” But the phrase stuck in his head.

The modern battle over menhaden began one day in 1997, when a recreational fisherman named Jim Price turned up at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources with a malnourished and diseased striped bass he had caught. A pathologist there speculated that stripers may have gotten “decoupled from their prey,” and Price, who has no scientific training, thought, “What the hell?” But the phrase stuck in his head.

At six o’clock one recent Saturday evening, at a dock on Maryland’s Eastern Shore where sports fishermen bring their catches to be cleaned, Price was scissoring open the bellies of striped bass carcasses. With each dissection, he called out a litany of data, to be noted down by his wife Henrietta: “Thirty inches. Male. Zero body fat. Spleen good. Stomach empty.”

Price is a jeweler and gem dealer by trade, 69 years old, overweight, hunched, with big rimless eyeglasses on a knobby round face. His manner is both plodding and mildly hectoring. Henrietta has learned to fend him off in an endless round of spousal thrust-and-parry. But no one can keep him from talking about either striped bass or menhaden, preferably both, in a relentless monologue punctuated with phrases such as “I’m the only one out there who sees this” or “They don’t understand like I do.” At one point, midway through a dissection, he mentioned that he has cancer of the colon and liver and that his doctor gave him a few months to live, three years ago. Then he cut open the next fish.

A few of the striped bass carcasses that evening had menhaden in their bellies, swallowed whole. One came out ghoulishly half-digested, eyes gone, skin dissolved, muscle just receding from the pearly, translucent tips of its ribs. But most of the 55 fish Price dissected had empty stomachs and zero body fat. And it was his passionate contention, from 10,000 such dissections, summer and winter, that striped bass in the Chesapeake Bay are starving. They are starving, he said, because the reduction industry has fished the menhaden almost down to nothing.

Many of the most familiar Atlantic Coast predators, from bluefish to humpback whales and from pelicans to bald eagles, depend on menhaden. Like herring, sardines, anchovies, and other small, prolific species, menhaden are “forage fish” and vital as prey for other species. Or as a sports fisherman explained to me, “In nature it’s eat or be et, and menhaden are on the ‘be et’ side of the equation.”

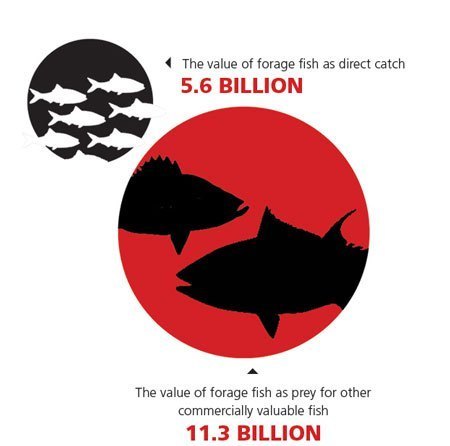

What’s happening to them also fits what scientists say is a dangerous pattern of overharvesting forage fish and jeopardizing their predators worldwide. Off the coast of Peru this year, for instance, overfishing of anchovies, together with shifting weather patterns, has caused massive die-offs of seabirds and dolphins. In April, the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force, a panel of marine and fisheries scientists, called for cutting the catch of forage fish globally by half. It also calculated that forage fish would be worth twice as much to fishermen if they just left them in the water to be eaten by pricier species such as striped bass, cod, or tuna.

What’s happening to them also fits what scientists say is a dangerous pattern of overharvesting forage fish and jeopardizing their predators worldwide. Off the coast of Peru this year, for instance, overfishing of anchovies, together with shifting weather patterns, has caused massive die-offs of seabirds and dolphins. In April, the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force, a panel of marine and fisheries scientists, called for cutting the catch of forage fish globally by half. It also calculated that forage fish would be worth twice as much to fishermen if they just left them in the water to be eaten by pricier species such as striped bass, cod, or tuna.

The idea that overharvesting little fish starves out the bigger ones is an old complaint. Fishermen in the 1870s actually rioted and burned down a menhaden reduction plant on the coast of Maine because they blamed it for the loss of cod and other valuable species. The same concern for species farther up the food chain has in recent years caused every East Coast state except Virginia to ban the reduction industry within its waters.

The complaining has gotten louder in recent years, partly because of the importance of Chesapeake Bay as a nursing ground for the entire East Coast and partly because some people have begun to question the logic of investing large sums to restore other commercial fish species if there aren’t enough menhaden out there for them to eat. The target for these complaints has also become more obvious: concentration of the industry means that the fate of the Atlantic menhaden may now be determined by a single state and a single corporation, Omega Protein.

People in Reedville, where Omega Protein has 275 employees and a dwindling fleet of just nine boats, tend to return the complaints, times two. “The campaign by conservationists is not about cutting back. It’s not about getting more fish. It’s about getting rid of Omega Protein,” said Jimmy Kellum, who owns two menhaden boats and sells about half his catch to the reduction plant. He fumed a bit as he slapped paint on parts for a new boat he was building. Then he added, “What right does Florida or Maine have to say what we can do with our resource? I know you’re going to say he’s a migratory fish. But he’s mine when he’s in my yard.” If menhaden have been largely absent from New England waters since the early 1990s, it’s not Reedville’s fault, he said. “That’s God’s will, whether he contracts the fishery, or expands the fishery into Maine.”

Read The Halo Effect from Eating Menhaden (The Oiliest Catch–Part 4)