Richard Conniff's Blog, page 85

October 26, 2012

A Good Handful of Sea Snakes

The great heyday of natural history museums is over, and nowadays, these institutions, and their vast backrooms of aging specimen collections, tend to be badly funded, or even completely put out of business.

But they also continue to produce surprises, including the discovery of new species. Here’s a ScienceDaily account of a newly found sea snake, Aipysurus mosaicus, from a museum in Copenhagen.

In a formalin-filled jar in Copenhagen Natural History Museum, a new snake species has recently been discovered.

“Museums are probably full of undiscovered species, and are an invaluable archive worthy of protection, just like the jungle itself,” says Johan Elmberg, professor of animal ecology at Kristianstad University in Sweden.

The newly discovered mosaic sea snake, named after its unusually patterned skin, which looks just like a Roman floor mosaic, lives in one of the world’s most endangered environments — the tropical coral reefs around Northern Australia and Southern New Guinea.

“Sea snakes are a good indicator of how the coral reefs and other precious ecosystems are doing. If there are snakes left in the environment it shows that the reefs are healthy and intact,” says Johan Elmberg.

The new sea snake was found by chance by two research colleagues, John Elmberg and Arne Rasmussen, associate professor at the School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. One day at the Natural History Museum in Copenhagen they examined formalin-filled jars of snakes and found two sea snakes with the same name on the label, which had been there since being sent home by the great collectors of the eighteen hundreds.

As it happened, the specimens had been misidentified by one of my least favorite nineteenth-century naturalists, John E. Gray of the British Museum. (I am inferring that he was the Gray named on the identifying label simply as Gray 1849.) He was a closet naturalist, never left the comforts of home, but made a minor career out of ridiculing field biologists for their mistakes. (You can read about some of this in my book The Species Seekers.) This time, it was Gray who made the mistake.

“But they looked different and didn’t seem to belong to the same group of snakes. That was where the detective work began. After comparing the sea snakes with other similar species in other museums in Europe it was even more obvious that we had found a new distinct sea snake,” says Johan Elmberg.

The Mosaic sea snake belongs to a good handful of species ranging in southeast Asia and Australia. The snake never goes ashore and now that its identity is known it is apparent that it is relatively common in the sea in northern Australia and southern New Guinea.

“There are millions of sea snakes, but how they live, where and at what depth is difficult to know exactly because these snakes are so difficult to study,” says Johan Elmberg.

Some species of sea snake are considered as having the strongest venom of all snakes, but because the species that Johan and Arne discovered is one of the few that feed on fish eggs, it has only very small fangs and is therefore virtually harmless. Of all the 3000 snake species in the world, only 80 or so live in the oceans. To analyze the tissue samples Johan Elmberg and Arne Rasmussen were helped by Kate Sanders, a molecular ecologist in Australia, who also collected tissues from living individuals of the new species and examined them in a DNA lab. The analysis showed a very clear difference in the genetic composition of the newly discovered species compared to other similar sea snakes.

“When Kate told us that we actually had found a new snake species, I got chills. To find a new species is a biologist’s ultimate dream,” says Johan Elmberg.

Johan believes that it is very important to document the biodiversity of the marine environment to get a grip on the status of the coral reefs for example.

“This discovery also highlights very clearly the importance of the museum’s treasure trove of biodiversity. There are lots of species still to be discovered in the world’s museums, which unfortunately often struggle to finance their operations,” says Johan Elmberg.

You can read the full species description in the journal Zootaxa. Among other details, it notes that the new species and the one for which it was originally mistaken have been separated by about two million years of evolution.

October 25, 2012

Educate Boys and Girls Equally. Both Matter.

I believe in increasing educational opportunities for girls. But I am disturbed by what seems to be a corresponding tendency to trivialize education of boys. Look on the internet, and you will see the idea sanctified with a supposed African proverb: “Educate a boy and you educate an individual. Educate a girl and you educate a community.”

As far as I have been able to tell (and please correct me if anybody out there can point out an actual African origin), this fantasy “African proverb” is actually a sort of Reader’s Digest condensation of a thought in Greg Mortenson’s book Three Cups of Tea.

Here’s what Mortenson wrote:

“Once you educate the boys, they tend to leave the villages and go search for work in cities. But the girls stay home, become leaders in the community and pass on what they’ve learned. If you really want to change a culture, to empower women, improve basic hygiene and health care, and fight high rates of infant mortality, the answer is to educate girls.”

So here’s a better condensation of the first half of what Mortenson wrote: “Educate a boy and you educate a city,” and thus perhaps a nation.

And regarding the second half: Isn’t it kind of patronizing to think that all you do when you educate a girl is educate a village?

Malala Yousafzai was reaching a little higher than that. Boys can, too.

October 24, 2012

Sorry, What? Gaga Ferns and Bootylicious Horseflies

Lady Gaga and namesake fern gametophyte.

Weird science, from ScienceDaily:

Pop music megastar Lady Gaga is being honored with the name of a new genus of ferns found in Central and South America, Mexico, Arizona and Texas. A genus is a group of closely related species; in this case, 19 species of ferns will carry the name Gaga.

At one stage of its life, the new genus Gaga has somewhat fluid definitions of gender and bears a striking resemblance to one of Gaga’s famous costumes. Members of the new genus also bear a distinct DNA sequence spelling GAGA.

Two of the species in the Gaga genus are new to science: Gaga germanotta from Costa Rica is named to honor the family of the artist, who was born Stefani Germanotta. And a newly discovered Mexican species is being dubbed Gaga monstraparva (literally monster-little) in honor of Gaga’s fans, whom she calls “little monsters.”�

“We wanted to name this genus for Lady Gaga because of her fervent defense of equality and individual expression,” said study leader Kathleen Pryer, a Duke University biology professor and director of the Duke Herbarium. “And as we started to consider it, the ferns themselves gave us more reasons why it was a good choice.”

For example, in her performance at the 2010 Grammy Awards, Lady Gaga wore a heart-shaped Armani Prive’ costume with giant shoulders that looked, to Pryer’s trained eyes, exactly like the bisexual reproductive stage of the ferns, called a gametophyte. It was even the right shade of light green. The way the fern extends its new leaves in a clenched little ball also reminds Pryer of Gaga’s claw-like “paws up” salute to her fans.

The clincher came when graduate student Fay-Wei Li scanned the DNA of the ferns being considered for the new genus. He found GAGA spelled out in the DNA base pairs as a signature that distinguishes this group of ferns from all others.

Celebrity species abound in science. There’s a California lichen named for President Barack Obama and a meat-eating jungle plant named for actress Helen Mirren. In January, an Australian horse fly described by its discoverer as “bootylicious” was named for singer Beyonce.

But those are just individual species. This is an entire genus that so far includes 19 species of ferns.

Except for the two new species, germanotta and monstraparva, the rest of the Gaga ferns are species that are being reclassified by Pryer and her co-authors. They had previously been assigned to the genus Cheilanthes based on their outward appearance. But Li’s painstaking analysis of DNA using more than 80 museum specimens and newly collected plants showed they’re distinct and deserving of their own genus.

New tools for genetic analysis are reorganizing the family tree of ferns, said Pryer, who is currently president of the American Fern Society, and president of the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, the scientists who name and categorize plant species.

Like most ferns, the Gaga group is “homosporous.” They produce tiny spherical spores that drift to the ground and germinate into heart-shaped plants called gametophytes. These independent little organisms can be female, male or even bisexual, depending on growth conditions and what other kinds of gametophytes are around. When conditions are right, they exchange sperm between gametophytes, but when necessary they sometimes can also self-fertilize to produce a new fern.

“The biology of these ferns is exceptionally obscure and blurred by sexual crossing between species,” Pryer said. “They have high numbers of chromosomes and asexuality that can lead to offspring that are genetically identical to the parent plant.”

Pryer freely admits that she and her lab are big Gaga fans. “We often listen to her music while we do our research. We think that her second album, ‘Born this Way,’ is enormously empowering, especially for disenfranchised people and communities like LGBT, ethnic groups, women — and scientists who study odd ferns!” Pryer said.

“What a remarkable, unexpected, perfect tribute to name a genus of ferns for Lady Gaga,” said Duke faculty member Cathy N. Davidson, who was involved in the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media and Learning Initiative that helped Lady Gaga to create the Born This Way Foundation, a national anti-bullying initiative. “Encouraging her fans and kids everywhere to be brave, bold, unique, creative and smart is what Lady Gaga is about,” Davidson says. “It’s rare that a celebrity so young gives back so much to society.”

The research was funded in part by National Science Foundation, grant DEB-0717398.

Editor’s Note: A YouTube video of Lady Gaga’s performance at the 2010 Grammys, which helped inspire this naming honor, may be found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehJ4PB5o6cA

Why Flies? Maybe for Fish Farm Feed

Salmon feeder? (SEM by MicroAngela)

In my book Spineless Wonders: Strange Tales of the Invertebrate World, I included a chapter with the headline, “Why Did God Make Flies?”

Now we know, thanks to this intriguing report from NPR’s Eliza Barclay. Recycled maggots, anyone?

What’s the lowly house fly got to do with the $60 billion fish farming industry?

Quite a lot, says Jason Drew, a jet-setting British entrepreneur who is so enthusiastic about the potential of flies, he’s just written a book called The Story of the Fly and How It Could Save the World. He thinks flies can solve one of aquaculture’s most vexing issues: what to feed the growing ranks of farmed fish.

Farm-raised salmon, trout and shrimp need a lot of animal protein in their diet. Right now, that protein comes mainly from small, wild fish that are turned into fish meal. It takes about 3 pounds of fish to produce 1 pound of farmed salmon, and as we continue to deplete wild fish stocks, fisheries experts say we’re going to run out.

And so aquaculture experts all over the world are scrambling to figure out what to do about it.

A few years back, Drew was checking out some farms in Saudi Arabia that were exporting chicken and shrimp to South Africa, where he lives. He saw all the fish meal going to feed those creatures, and got to thinking just how unsustainable it was.

He also noticed, he says, that “the price of fish meal was moving in one direction only: up. Unless we find a new sea.”

At a slaughterhouse in Saudi Arabia, he stumbled upon what could become the new sea: a huge pond of blood, buzzing with flies. After consulting with some scientists, Drew became convinced that flies could recycle the protein in animal blood and replace fish meal to feed fish, chicken and other animals.

He was so convinced, he founded a company to give it a shot. In 2009, his company, AgriProtein, purchased its first batch of flies to breed for industrial production. After a couple of years of tinkering, his team figured out how to produce protein-rich larvae in bulk. It helps that one fly can lay up to 1,000 eggs, and 1 pound of eggs can grow into 380 pounds of larvae.

The fly larvae in the AgriProtein factory feed on cow blood and bran.

Courtesy of Jason Drew

Today Drew has a fly factory up and running near Cape Town and is selling his Magmeal, a brown crumbly protein meal made of maggots, or fly larvae, to South African salmon and chicken farms. By next year, he says his factory will be producing 100 tons of fly meal a day. “That’s 100 tons we don’t have to take out of the sea,” he says. “And we can’t keep up with demand.”

At one end of the factory the mother flies lay their eggs. Members of Drew’s staff extract the eggs, but save a small number of them to put back into the breeding stock. They take the remaining eggs and hatch them into larvae, where they’re fed a rich meal of blood from a nearby slaughterhouse, plus bran. After two or three days, they’re the perfect size for harvesting and are ground into Magmeal.

Drew says it’s only a matter of time before more entrepreneurs around the world discover fly farming.

“What we’ve done is just industrialize a natural food source,” he says. “It takes a fair bit of cash to get off the ground, but I believe small-stock farming is going to be one of the great businesses of the next 20 years.” And he’s already talking to people around the world who want to license his technology.

Of course, the search for a fish meal replacement goes far beyond flies. Researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are looking for ways to use more marine algae, fish processing trimmings and plants in fish feed. And as we reported last year, other scientists think biofuel co-products, poultry byproducts and soybeans have potential, too.

October 23, 2012

Elephant Poo Air Conditioning

Dung beetle in booties

Apparently, elephant excrement is the next best thing to a Frigidaire window unit, if you are a dung beetle, according to researchers studying how the beetles roll balls of dung across the desert to their nest, in South Africa:

“The beetles climb on top of their moist balls whenever their front legs and heads overheat,” said Prof. Marcus Byrne from Wits University. “We stumbled upon this behaviour by accident while watching for an ‘orientation dance’ which the beetles perform on top of their balls to work out where they’re going. We noticed that they climbed their balls much more often in the heat of the midday sun.”

Further experiments showed that this midday phenomenon only held true when the beetles were crossing hot ground. In fact, beetles on hot soil climb their balls seven times as often as those on cooler ground.

To show that it was the beetles’ hot legs that made them climb the ball, the researchers applied some cool (as in temperature) silicone boots to their front legs as alternative protection from the heat. “To our great surprise, this actually worked, and beetles with boots on climbed their balls less often,” said Dr Jochen Smolka from Lund University, who collaborated on the research.

You have to love any study that involves putting booties on dung beetles. And one last bit of ickiness:

Once on top of a ball at midday, the beetles were often seen “wiping their faces,” a preening behavior that the researchers suspect spreads regurgitated liquid onto their legs and head to cool them down further. That’s something the insects never do at other times of day.

Source: Jochen Smolka, Emily Baird, Marcus J. Byrne, Basil el Jundi, Eric J. Warrant, Marie Dacke. Dung beetles use their dung ball as a mobile thermal refuge. Current Biology, 2012; 22 (20): R863 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.057

October 22, 2012

Continental Drift Science: From Heresy to Jail Time

A few months back, I profiled the scientist who discovered continental drift. The Smithsonian Magazine version of the story opened this way:

In a courtroom in Italy, six seismologists and a civil servant are facing charges of manslaughter for failing to predict a 2009 earthquake that killed 308 people in the Apennine Mountain city of L’Aquila. The charge is remarkable partly because it assumes that scientists can now see not merely beneath the surface of the earth, but also into the future. What’s even more extraordinary, though, is that the prosecutors put such faith in a scientific insight that was, not so long ago, the object of open ridicule.

So now, an Italian court has convicted the seismologists and packed them off to jail for six years for the crime of having given false assurances in the days before the earthquake. It’s an astonishing decision, and especially ironic on the hundredth anniversary of the fundamental theory underlying all geology. The theory of continental drift, proposed by Alfred Wegener in 1912, was considered scientific heresy for much of the twentieth century. Now it gets you jail time.

The sentencing has caused deep dismay in the scientific community and on the internet. On Twitter, @dbasch says, “Being a seismologist in a country that doesn’t understand science is a risky job. This is insane.” (Looking on the bright side, he’s not talking about the United States, for once.)

And @seamusmccauley says, “Italy’s remaining seismologists unanimously predict daily earthquakes at all locations for the next 500 years.”

You can read my continental drift story–and weep for Alfred Wegener–here.

Splitsville with Constantine Raffinesque

Today’s the birthday of Constantine Rafinesque (1783-1840), a notorious “splitter.” What did he split?

1. He split his specimens for easy storage.

1. He split his specimens for easy storage.

2. He split established species into several new species.

3. He split wood.

4. He split collections to sell to different museums.

And the answer is

Constantine Rafinesque was a species monger, too drunk on the elixir of discovery to take much care with his work. Rafinesque’s zeal for names and categories was such that he once supposedly submitted a scientific paper describing 12 new species of thunder and lightning. Certain naturalists, Rafinesque notorious among them, had mastered the trick of racking up “discoveries” by taking one perfectly good species and subdividing it into a half-dozen new species based on trivial differences. These “splitters” drove naturalist Thomas Say, who was otherwise mild and genial, to fulmination: “… posterity will rise up in judgment against all those pirated names & indignantly strike them from the list.” He was right. In the twentieth century, “lumpers” would devote whole careers to the heroic but tedious work of un-discovery, recombining spurious species and ushering them back to their proper places in the taxonomic order.

Read more about Rafinesque’s colorful career in The Species Seekers by Richard Conniff.

Back to the Essence

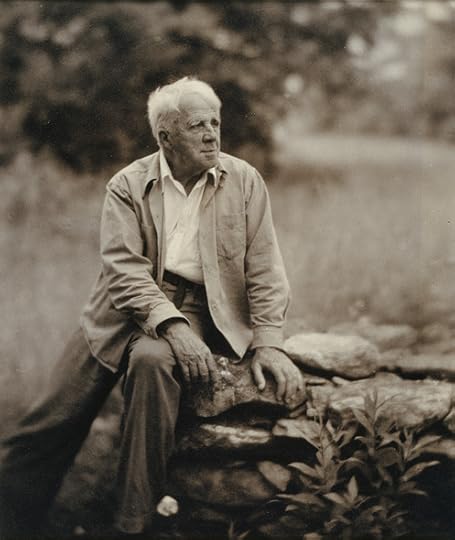

Robert Frost (1874-1963)

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, has just opened a show called “Poetic Likeness: Modern American Poets,” and it reminds me of the intimate connection between poetry and a love of the natural world. People who become biologists tend to get caught up in taxonomy, or population dynamics, or even, good lord, ecosystem services, and these are all important enough. But it’s good to get back to the essence. So here’s Frost’s celebrated poem “Birches”:

WHEN I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay.

Ice-storms do that. Often you must have seen them

5

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain. They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells

10

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

15

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

20

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm

(Now am I free to be poetical?)

I should prefer to have some boy bend them

As he went out and in to fetch the cows—

25

Some boy too far from town to learn baseball,

Whose only play was what he found himself,

Summer or winter, and could play alone.

One by one he subdued his father’s trees

By riding them down over and over again

30

Until he took the stiffness out of them,

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

For him to conquer. He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

And so not carrying the tree away

35

Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise

To the top branches, climbing carefully

With the same pains you use to fill a cup

Up to the brim, and even above the brim.

Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish,

40

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

45

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

I’d like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

50

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love:

I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,

55

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

60

You can also hear Frost himself reading the the poem here:

October 19, 2012

Duelling with a Flick-Knife Frog

Flick knife (by yunalee)

A Japanese researcher (and presumptive anime fan) has revealed how a frog can flick out sharp spikes from a false thumb for both combat and mating.

Noriko Iwai from the University of Tokyo, studied the Otton frog (Babina subaspera), on the Amami islands in southern Japan. Unlike most frogs, Otton has a fifth digit, a sort of pseudo-thumb, containing the switchblade spikes. Science Daily reports that the thumb serves mainly to hang onto the female in the muddy throes of amphibian love-making:

“While the pseudo-thumb may have evolved for mating, it is clear that they’re now used for combat,” said Dr Iwai. “The males demonstrated a jabbing response with the thumb when they were picked up, and the many scars on the male spines provided evidence of fighting.”

The conditions on the Amami islands make combat, and the need for weaponry, a key factor for the frogs’ mating success. Individuals fight over places to build nests, while the chances of a male finding a mate each night are rare, thus the ability to fight off competitors may be crucial.

Sadly, the frogs don’t face off as in the rumble scene from “West Side Story” (or, to stick with anime, like Spike versus Vicious). Instead, they go in for the desperate clinch and then dirty-box:

Armed charmer

Perhaps unfortunately, the comic book hero image is slightly dented by the frogs’ fighting style. Rather than dueling with thumb spikes the males wrestle each other in an embrace, jabbing at each other with the spines. This fighting style helps confirm the theory that the spines were original used for embracing mates.

Also sorry to say, Dr. Iwai’s closeup of the weaponry suggests sharpening may be in order.

Also sorry to say, Dr. Iwai’s closeup of the weaponry suggests sharpening may be in order.

N. Iwai. Morphology, function and evolution of the pseudothumb in the Otton frog. Journal of Zoology, 2012; DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2012.00971.x

October 18, 2012

Danger Ahead: Business as Nature’s Savior

Here’s my latest article for Yale Environment 360.

Ecosystem services is not exactly a phrase to stir the human imagination. But over the past few years, it has managed to dazzle both diehard conservationists and bottom-line business types as the best answer to global environmental decline.

For proponents, the logic is straightforward: Old-style protection of nature for its own sake has badly failed to stop the destruction of habitats and the dwindling of species. It has failed largely because philosophical and scientific arguments rarely trump profits and the promise of jobs. And conservationists can’t usually put enough money on the table to meet commercial interests on their own terms. Pointing out the marketplace value of ecosystem services was initially just a way to remind people what was being lost in the process — benefits like flood control, water filtration, carbon sequestration, and species habitat. Then it dawned on someone that, by making it possible for people to buy and sell these services, we could save the world and turn a profit at the same time.

But the rising tide of enthusiasm for PES (or payment for ecosystem services) is now also eliciting alarm and criticism. The rhetoric is at times heated, particularly in Britain, where a government plan to sell off national forests had to be abandoned in the face of fierce public opposition. (The government’s own expert panel also found that it had “greatly undervalued” what it was proposing to sell.) Writing recently in The Guardian, columnist and land rights activist George Monbiot denounced PES schemes as “another transfer of power to corporations and the very rich.” Also writing in The Guardian, Tony Juniper, a conservationist and corporate consultant, replied in effect that Monbiot and other critics should shut up, on the grounds that campaigning against payment for ecosystem services “could inadvertently strengthen the hand of those who believe nature has little or no value, moral, economic or otherwise.”

Not all critics reject the PES idea outright. Some say they’re merely making constructive criticisms of what they see as blind faith in new financial markets, and in global initiatives like the United Nations’ REDD mechanism (for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries).

The first mistake, says Kent H. Redford, an environmental consultant, is to assume that old-style conservation methods have failed. “They’ve worked in certain circumstances, in certain ways, for certain things.” They’re the reason, for instance, that state-sponsored protected areas now cover 25 percent of the land in Costa Rica, 27 percent in the United States (at the federal level alone), 30 percent in Tanzania and Guatemala, and 50 percent in Belize.

Writing in Conservation Biology, Redford and co-author William M. Adams catalogued some of the ways PES transactions can go wrong, beginning with the whole question of price. Traditional conservationists sought to protect forests and other landscapes primarily for their intrinsic value, says Redford. But those values are likely to carry less weight when even conservationists think first in economic terms. Many ecosystem services are also likely to be hard to price — for instance, the arguably beneficial effects on climate and agriculture (minus the deleterious impacts on health) when atmospheric dust from the African Sahel drifts across the Atlantic. And even if you can put a price on an ecosystem service, Redford and Adams argue, figuring out who has a legitimate right to sell it means picking winners and losers. In developing countries, indigenous communities may lack the documentation or the political clout to assert their ownership.

Payment schemes also risk creating perverse incentives, Redford and Adams warn. If the system pays landowners to bank carbon, they may plant non-native species, or genetically “improved” trees, to bank carbon faster. Or they may discourage natural phenomena that happen to be good for biodiversity, but bad for people, including such ecosystem disservices as

Making the economic case for ecosystem services often ‘has more resonance’ with decision makers, one researcher says.

fire, drought, disease, or flood. Finally, Redford and Adams point out, the effects of climate change, “always the joker in the pack,” could toss carefully constructed economic schemes — and natural habitats — into disarray.

Stuart H. M. Butchart, a researcher at BirdLife International, replies that embracing the ecosystem services idea doesn’t necessarily mean abandoning the argument that species and habitats have intrinsic value. But making the economic case often “has more resonance” for decision-makers.

A study published last week in Science, co-authored by Butchart, also suggests why the PES idea now seems so urgent. To determine what it would cost to meet current targets set for the year 2020 under the international Convention on Biological Diversity, the study looked at the cost of protecting and down-listing threatened bird species. Then it extrapolated that preventing further loss of species across all plant and animal groups would cost $78 billion a year. That’s an order of magnitude above current conservation spending — but the study noted that it was only between 1 and 4 percent of the value of the ecosystem services being lost through habitat destruction every year.

PES proponents can also point to early success stories: Vittel-Nestlé Waters recognized a few years ago that its aquifer in northern France was being polluted by nitrate fertilizers and pesticides from nearby farms. It devised a scheme to pay farmers to change their methods and deliver the ecosystem service of unpolluted water. Beijing undertook a similar scheme in the catchment around one of its reservoirs, ahead of the 2008 Olympics. (It had previously tried anti-growth regulations and resettlements.)

But there isn’t always a wealthy corporation or a big city nearby willing to pick up the tab (for Vittel, $31.4 million over the first seven years), and other transactions are more complex. Norway, for instance, pledged $1 billion each to Brazil and Indonesia for forest preservation efforts under the REDD mechanism, partly to compensate for failing to meet its own greenhouse gas emissions targets. But the Norwegian government recently felt compelled to issue a public warning to both countries against backsliding on their forest preservation commitments.

Monbiot adds that making nature fungible, so one asset can be substituted for another, guarantees that they will be: “If a quarry company wants to destroy a rare meadow, for example, it can buy absolution by paying

Critics are uncomfortable with viewing nature ‘as a service provider fit to be incorporated into the global capital markets.’

someone to create another somewhere else.” When governments and PES proponents talk about employing marketplace solutions instead of traditional regulatory approaches, he says, “what they are really talking about is shrinking democracy, shrinking public involvement in decision making, shrinking transparency and accountability. By handing it over to the market you are in effect handing it over to corporations and the very rich,” and to “a very plutocratic” decision-making process.

Pavan Sukhdev, a former international banker who has pioneered efforts to highlight the economic importance of biodiversity, says none of these criticisms is especially new. He has raised many of them himself and says the marketplace is working to address them. “It’s useful to hear criticisms, but the critics must remember one basic fact. It wasn’t Christopher Columbus who discovered America, it was the Native Indians who lived there. So critics should not think that they have invented knowledge. They should be a little more humble in their attitude. And understand that the people on the ground are professionals who have been working on this and thinking about this for quite some time.”

But no amount of financial tweaking or social engineering is likely to allay the deeper discomfort voiced by many PES critics with the whole idea of nature, in the words of one recent paper, “as a service provider fit to be incorporated into the global capital markets.” Or the notion, expressed by Jean-Christophe Vié, of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, that nature is “the largest company on Earth.” When you view nature in economic terms, as a provider in a sort of “master-servant” relationship, they suggest, you make a fundamental change not just in the world around us, but in ourselves.

MORE FROM YALE e360

Putting a Price on

The Real Value of Nature

Indian banker Pavan Sukhdev has been grappling with the question of how to place a monetary value on nature. In an e360 interview, he discusses the ways natural ecosystems benefit people and why policymakers and businesses must rethink how they assess environmental costs and benefits. READ MORE

Sian Sullivan, a University of London anthropologist, warns that past revolutions in capital investment, like the enclosure of common lands in eighteenth-century Britain, and the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century, resulted in “the shattering of peoples’ relationships with landscapes” and the conversion of rural folk into factory workers and service-providers for capital. In the ecosystem services movement, Sullivan warns, we are seeing “a major new wave of capture and enclosure of Nature by capital.” And it will come, she says, at the cost of profound cultural and psychological upheaval.

It may be, as some argue, that we have no better way to save the world. But the danger in the process is that we may lose our souls.