Richard Conniff's Blog, page 83

December 7, 2012

The Halo Effect from Eating Menhaden (The Oiliest Catch–Part 4)

Atlantic menhaden

The name “menhaden” comes from a Native American word for fertilizer, and it’s generally thought to be the species Squanto advised the Pilgrims to plant with their corn. On the Connecticut coastline, where I live, farmers used to apply them to their crops at a rate of 10,000 per acre—enough to make even a Reedville resident gag. Menhaden meal has been an ingredient in chicken, pig, and dairy feed since at least the nineteenth century. It’s now also a standard part of the diet on many fish farms, where it typically takes four pounds of forage fish to produce a pound of the salmon and other species we like to eat.

Menhaden rarely turn up on our dinner plates baked, fried, or otherwise; the combination of oil and bones is just too daunting. But we eat menhaden more often than we generally realize. It is a key ingredient, for instance, in the Smart Balance Omega-3 spread I buttered onto my toast this morning, and it’s one reason the eggs I just ate, formerly deemed a cholesterol nightmare, are now prominently labeled as a heart-healthy omega-3 product. Highly refined menhaden oil also turns up in salad dressings (such as Cindy’s Kitchen All Natural brand), cookies (Trader Joe’s Five Seed Almond Bars), and other products that can seem just a little healthier thanks to the omega-3 halo effect.

Menhaden rarely turn up on our dinner plates baked, fried, or otherwise; the combination of oil and bones is just too daunting. But we eat menhaden more often than we generally realize. It is a key ingredient, for instance, in the Smart Balance Omega-3 spread I buttered onto my toast this morning, and it’s one reason the eggs I just ate, formerly deemed a cholesterol nightmare, are now prominently labeled as a heart-healthy omega-3 product. Highly refined menhaden oil also turns up in salad dressings (such as Cindy’s Kitchen All Natural brand), cookies (Trader Joe’s Five Seed Almond Bars), and other products that can seem just a little healthier thanks to the omega-3 halo effect.

Almost everyone I spoke with, on both sides of the menhaden fight, also seemed to be taking fish oil in capsule form, at times with almost religious devotion. Research since the 1990s has demonstrated persuasively that omega-3 fatty acids promote normal brain and eye development and can protect against heart disease—hence their reputation as a “miracle food.”

Menhaden is a latecomer to this booming market. Most fish-oil capsules instead contain o il from sardines and anchovies caught on the Pacific Coast of South America. Neither these species nor menhaden actually produce the omega-3 oil themselves. They get it from the algae they eat. And yes, that means it’s possible to bypass the fisheries issue entirely and get your ritual omega-3 dose from algae, too. At a laboratory in a nondescript office park in Columbia, Maryland, a few hours north of Omega Protein, for instance, researchers for Dutch conglomerate DSM take microalgae gathered from beaches or scraped from boat hulls and use them to brew omega-3 oils the way other companies brew beer or antibiotics. But the resulting oil retails for two or three times the price of fish oil.

il from sardines and anchovies caught on the Pacific Coast of South America. Neither these species nor menhaden actually produce the omega-3 oil themselves. They get it from the algae they eat. And yes, that means it’s possible to bypass the fisheries issue entirely and get your ritual omega-3 dose from algae, too. At a laboratory in a nondescript office park in Columbia, Maryland, a few hours north of Omega Protein, for instance, researchers for Dutch conglomerate DSM take microalgae gathered from beaches or scraped from boat hulls and use them to brew omega-3 oils the way other companies brew beer or antibiotics. But the resulting oil retails for two or three times the price of fish oil.

Hence Omega Protein sees a market niche and better profit margins by moving menhaden into the “nutraceuticals” market. Through recent acquisitions, it has its own retail fish-oil brand, Omega Activ. For now, though, the company is still mainly in the business of selling menhaden as animal feed; according to an Omega Protein spokesman, more than half the company’s menhaden catch now goes to China and other Asian markets as pig and fish feed.

Read Dead Pogie Season (The Oiliest Catch–Part 5)

Dead Pogie Season (The Oiliest Catch–Part 5)

People who study fisheries often worry about “shifting baselines,” the insidious tendency to lose track of history and make decisions based only on living memory. It’s what drives fishermen to oppose regulation on the grounds that they had a good catch just last week, or last year—never mind how things looked 40 or 400 years ago. And yet, if you need a sense for how bad things have gotten with menhaden, sometimes memory serves just fine.

In Maine, where they are known as pogies, menhaden were abundant enough in the early 1990s to be deemed a nuisance. Under hot pursuit by bluefish and other predators, whole schools of them would pile into narrow estuaries, where they soon consumed all the available oxygen and died. Horrified vacationers awoke to find fish floating in vast, stinking, yellow mats. Lobsters actually climbed out of the water in desperation. A headline announced, “Massive Kill Means Dead Pogy Season Has Arrived.” The good news was that Maine fishermen caught 60,000 tons of menhaden in a season then. Their biggest customer was a rusting, Soviet-era factory ship named the Riga, which had anchored offshore and was doing a brisk business grinding up menhaden to feed chickens and pigs back in Murmansk.

I got a first-hand sense of how abundant the menhaden were one summer 20 years ago, when I headed out of Rockland, Maine, at midnight aboard a fishing boat named the Bobby E, bound toward an amber light a few miles offshore. To get aboard the Riga, I had to step off the Bobbie E in the dark, clamber across great, elephantine Yokohama fenders floating at the waterline, and climb a skewed wood-and-rope ladder banging against the hull.

The Riga’s factory equipment was primitive. A noisy conveyor belt delivered the fish to a device like a paper shredder which reduced them to a kind of brown sludge, and then . . . but you don’t really want to know. Every surface of the processing area was caked with fishmeal, as if breaded and fried. Fishmeal also drifted up in the corners, like dust in the bottom of a cereal box. An American intermediary living on board told me he had killed a dozen rats in his cabin just within the past month.

What really stuck in my memory, though, was the abundance of menhaden. Riga crewmen, including the ship dentist, vied to work as “lumpers” down in the hold of the Bobby E. Their job, by the light of a bare 60-watt bulb, was to climb up the great walls of stacked menhaden and kick them down in an avalanche toward a large vacuum tube, to be sucked up onto the ship. They came out smeared head to toe in menhaden gore, but with 50 cents a ton in their pockets.

When I woke up next morning back in Rockland, that whole night seemed like a strange dream, and it still seems like a dream today because the menhaden soon vanished from the coast of Maine. The annual menhaden catch there is now close to zero, and it’s stayed that way for almost 20 years. In fact, in all of New England only a single bait company still fishes for menhaden. It’s based in Rhode Island but often has to travel to New Jersey to find fish.

A few people in Virginia still remember the Riga, too, and it serves them as a fallback line of defense. If there really is something wrong with the menhaden fishery, they told me, it isn’t the fault of Omega Protein’s menhaden fleet in Reedville.

They blamed it on the Russians instead.

Read A Knack for Collective Dithering (The Oiliest Catch–Part 6)

A Knack for Collective Dithering (The Oiliest Catch–Part 6)

In fact, the health of the menhaden population has always been the business of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), a 15-state organization that jointly regulates coastal fisheries. But seeing the commission in action does not inspire much confidence, even within its own ranks. It was a small moment, but seemed like a portent, when I got on a hotel elevator en route to a recent ASMFC meeting. The elevator voice said, “Going down,” and the only other passenger bleakly commented, “In so many ways.” He turned out to be the commissioner from the National Marine Fisheries Service. At the meeting itself, 45 people, mostly older white males, sat at tables arranged in a huge rectangle and collectively dithered.

In fact, the health of the menhaden population has always been the business of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), a 15-state organization that jointly regulates coastal fisheries. But seeing the commission in action does not inspire much confidence, even within its own ranks. It was a small moment, but seemed like a portent, when I got on a hotel elevator en route to a recent ASMFC meeting. The elevator voice said, “Going down,” and the only other passenger bleakly commented, “In so many ways.” He turned out to be the commissioner from the National Marine Fisheries Service. At the meeting itself, 45 people, mostly older white males, sat at tables arranged in a huge rectangle and collectively dithered.

They had previously decided to manage menhaden not just by traditional, single-species standards, but also based on how menhaden affect other species that depend on them as prey. A commissioner remarked that he couldn’t figure out how to do this kind of ecosystem management “in a pond in my backyard, much less in the Atlantic Ocean.” When a technical committee staffer said it would require $350,000 to develop rigorous scientific standards, a commissioner truculently suggested that activists in the audience come up with the cash. Then they voted to wait and see if the $350,000 might somehow turn up by their next meeting. Jim Price, who was there with his striped bass numbers, called it “management by procrastination.”

Until recently, scientists at both the ASMFC and the National Marine Fisheries Service repeatedly assured everyone that the menhaden population, though highly cyclic, was doing just fine. But Price kept saying otherwise, and other recreational fishermen—and, more gradually, fisheries biologists—lined up behind him. The failure of the menhaden, year after year, to come back in anything like the numbers seen even in the 1980s (much less the 1800s) also made the scientific assurances seem increasingly wishful.

The way fisheries biologists determine the health of the menhaden population is too complicated even for most commissioners to understand. As with other species, it involves a computer model with lots of assumptions built in. The model for menhaden has turned out over the past few years to be badly flawed. Until recently, for instance, it did not bother to calculate how many menhaden were being killed by bluefish, stripers, and other predators—meaning that a bigger take for commercial fishermen seemed sustainable. Then, in 2010, a Maryland state fisheries biologist working line by line through computer code noticed an error that effectively double-counted some menhaden data.

Finally, a peer review by independent scientists knocked out the most fundamental assumption in the menhaden model. When commercial fishermen talk about leaving enough menhaden in the water to produce 18.4 trillion menhaden eggs annually, they’re referring to an ASMFC standard. It’s based on the assumption that maintaining just eight percent of the menhaden population’s “maximum spawning potential” is good enough. That’s an unusually low number—“We don’t even manage some invertebrates at that level,” a Maryland fisheries biologist told me.

The peer-review panel said that the ASMFC had failed to protect the stock—and that verdict forced, at the very least, a show of change. At a meeting last year the commission voted to boost the eight-percent threshold to a minimum of 15 percent, with a target of 30 percent. It acknowledged for the first time that there had been “overfishing.” In fact, by its new standards, overfishing of menhaden has occurred in 32 of the past 54 years. It also made the somewhat Orwellian distinction that menhaden were not yet “overfished.” That is, they might be flirting with disaster. But they hadn’t arrived.

So far, none of these changes has had any effect on the menhaden fishery, and it’s possible they never will. Analysis by scientists suggests that rebuilding the menhaden fishery could mean cutting the catch by as much as 37 percent. But the commission has yet to decide whether to reduce the catch at all, or on what timeline. Commercial fishermen profess optimism that this process will work out in their favor.

The ASMFC’s critics, on the other hand, tend toward cynicism. “There’s a lot of politics surrounding this, probably more than in any fishery I’ve ever been involved with,” said Jud Crawford, a biologist with the Pew Environment Group. He worries that Omega Protein will thwart the process “or find a way to influence the stock assessment, which should not be possible in an ideal world.”

The cynicism derives in part from the commission’s one previous attempt to protect the menhaden. In 2005, responding to public protest, it set a limit on the menhaden catch in the Chesapeake Bay. But the limit was so high as to be “imaginary,” according to one ASMFC commissioner. “They would have had to significantly increase their fishing to reach the cap.” Even so, both the company and Virginia state officials vehemently resisted. Omega Protein’s lawyers drafted a legal brief, and Virginia’s then-attorney general, Bob McDonnell, used it to argue that Virginia could ignore the ASMFC cap. The eventual compromise was “a farce,” said Jim Price. “It’s now eight years without a single fish being saved.”

Virginia is already resisting any new limits on the menhaden catch. McDonnell, now governor, personally lobbied other governors before the ASMFC vote last fall to oppose raising the eight-percent standard. The state delegation has also maneuvered to delay any effort to rebuild the menhaden population, pushing for a ten-year schedule, twice the usual timeline for a recovery effort.

What will happen if the menhaden fishery ultimately faces a real reduction, on a tighter timeline? (A decision on the issue may come at the ASMFC meeting December 14.) A state senator in Virginia has already introduced legislation to secede from the ASMFC. But a more likely outcome would be another compromise, after years of legal wrangling.

Probably no one is more cynical about this process than Rutgers professor H. Bruce Franklin. After he published The Most Important Fish in the Sea in 2007, he said, Omega Protein sent a legal brief to the university, alleging factual errors and “implying that they were going to take Rutgers to court if it didn’t shut me up.” The tactic failed, but it touched a sensitive nerve for Franklin, who was once forced out of a tenured post at Stanford University for his leftist political activities. Asked what he thought was likely to happen with the menhaden fishery now, he hesitated for a moment, then remarked, “The line from Chinatown popped into my head: ‘As little as possible.’”

(See The Oiliest Catch–Conclusion.)

Inconvenient Truths (The Oiliest Catch–Conclusion)

But there is one final outcome that might be even more disturbing than the messy political fighting and procrastination over menhaden: it could turn out that Omega Protein is not the ultimate cause of the problem. That would no doubt annoy some conservationists for whom the company has served as a convenient target. But much worse, it might mean the menhaden fishery is broken beyond easy repair.

Scientists say they simply can’t promise that making Omega catch fewer fish will lead to recovery of the population. In theory, it ought to work: a mature menhaden female can produce 500,000 eggs annually, enabling even a heavily fished population to bounce back when the environmental circumstances are right.

But the failure of the population to rebound for 23 years straight suggests that something else is going on now, said University of Maryland biologist Edward D. Houde, a member of the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force. One hypothesis is that it’s a periodic shift in weather patterns offshore, where the menhaden spawn. In the past, a “Bermuda high” in March seemed to sweep more young fish into the Chesapeake, promising a good year for menhaden. Or an “Ohio Valley low” kept them out at sea. But that pattern seems to have broken down over the past two decades.

The larger problem of climate change may also mean that more menhaden are bypassing the Chesapeake, said Houde, and moving into estuaries farther north, where “the habitat isn’t big enough to produce what used to be produced.” Finally, there is the dismally polluted state of the Chesapeake itself—to which, ironically, the menhaden may now contribute, by being served up as feed on Maryland’s many poultry farms and then returned to the water in the form of nitrogen runoff.

These are big, intractable problems. Even so, said Houde, reducing the catch now is about the only short-term fix available, and it’s the right thing to do. Such reductions in the past have brought about recovery for species such as striped bass, mackerel, blue crabs, and summer flounder—as well as for the commercial fishermen who depend on them. This time, moreover, it’s not just about a single species.

In Reedville, people naturally focus on the painful economic consequences if the menhaden fishery faces a reduction. But it raises the larger question: What will happen if the base of the entire Atlantic coastal food chain disappears?

THE END

December 6, 2012

Did Ostracism Drive the Evolution of Cooperative Behaviors?

Behavioral scientists have argued for years about how social cooperation originated in an otherwise selfish world. Now a study suggests that the threat of social ostracism is what makes people play nice:

Social exclusion as a punishment strategy helps explain the evolution of cooperation, according to new research.

The new study provides a simple new model that ties punishment by social exclusion to the benefits for the punisher. It may help explain how social exclusion arose in evolution, and how it promotes cooperation among groups. The study, by IIASA Evolution and Ecology Program postdoctoral fellow Tatsuya Sasaki, was published December 5 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society — Biology.

“Punishment is a common tool to promote cooperation in the real world,” says Sasaki. “And social exclusion is a common way to do it.” From reef fish to chimpanzees, there are many examples of animals that promote cooperation by excluding free riders. Humans, too, use social exclusion as a way to keep people following societal rules. For example, says Sasaki, traffic violators or drunk drivers may be punished by losing their drivers licenses, essentially excluding them from the driving community.

But how did such punishment evolve? The new research, which uses evolutionary game theory, shows that excluding people from a group indirectly provides rewards for the punisher, thus encouraging them to exclude those they have reason to punish.

“Imagine a pie,” says Sasaki. The fewer people sharing that pie, the more pie everyone gets. But you can’t deny people pie for no reason. There needs to be a justification, for example, that someone did not contribute to baking the pie — a free rider, in game theory parlance. Sasaki says, “If you punish free riders with social exclusion, it increases the payoff for the punishers.”

Social exclusion also promotes cooperation, the study shows. If free riders are denied a piece of the pie, people will be more likely to cooperate and ensure they get to share in the reward.

Previous studies in evolution and game theory have mostly focused on other punishments that are more costly for the punisher. While a few studies have included social exclusion as one possible punishment, Sasaki’s work is the first to connect exclusion to the benefits for the punishers.

The study also compared social exclusion and costly punishment, showing that social exclusion could more easily emerge in a model system, and that it is maintained more easily than costly punishment.

The work has potential applications beyond biology, for example in understanding international cooperation. “It is important to understand how we have achieved some degree of cooperation across all kinds of collective enterprises that are important to local groups or to humankind at large,” says Sasaki, “In all such cases, our analysis could help design intervention strategies that enable future increases in cooperation.”

Tatsuya Sasaki has just accepted a second appointment as a project postdoctoral fellow at the University of Vienna.

Tatsuya Sasaki and Satoshi Uchida. The evolution of cooperation by social exclusion. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2012 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2498

December 5, 2012

In Africa: No Room for Lions

(Photo: Jonathan Griffiths/ Solent)

Where does the lion sleep tonight? Not in the jungle, the mighty jungle. Not much room on the savanna either. Maybe you can find a spot down the road at the zoo? I’ve written here before about the rapidly advancing likelihood of an Africa without wildlife. Now a new study confirms that lions are rapidly being displaced because of human population growth and agricultural expansion. The stunner here is that only 67 places remain on the entire continent with viable lion populations:

A new study confirms that lions are rapidly and literally losing ground across Africa’s once-thriving savannahs due to burgeoning human population growth and subsequent, massive land-use conversion. Representing the most comprehensive assessment of the state and vitality of African savannah habitat to date, the report maintains that the lion has lost 75% of its original natural habitat in Africa — a reduction that has devastated lion populations across the continent.

Using Google Earth’s high-resolution satellite imagery, the study examined savannah habitat across Africa, which comprises the majority of the lion’s current range, and also analyzed human population density data to identify areas of suitable habitat currently occupied by lions. Incredibly, the analysis identified only 67 isolated regions across the continent where significant lion populations may persist. Of these areas, just 15 were estimated to maintain a population of at least 500 lions.

“The reality is that from an original area a third larger than the continental United States, only 25% remains,” explained Stuart Pimm, co-author and Doris Duke Chair of Conservation at Duke University.

The study also confirms that in West Africa, where the species is classified as Regionally Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, fewer than 500 lions remain, scattered across eight isolated regions.

“Lions have been hit hardest in West Africa, where local governments often lack direct incentives to protect them,” Dr. Henschel commented. “While lions generate billions of tourist dollars across Eastern and Southern Africa, spurring governments to invest in their protection, wildlife-based tourism is only slowly developing in West Africa. Currently lions still have little economic value in the region, and West African governments will require significant foreign assistance in stabilizing remaining populations until sustainable local conservation efforts can be developed.”

Source: Jason Riggio, Andrew Jacobson, Luke Dollar, Hans Bauer, Matthew Becker, Amy Dickman, Paul Funston, Rosemary Groom, Philipp Henschel, Hans Iongh, Laly Lichtenfeld, Stuart Pimm. The size of savannah Africa: a lion’s (Panthera leo) view. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2012; DOI: 10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4

And take a look at Jonathan Griffiths’s stunning photos of big cats here.

December 3, 2012

Germans United for Sheep-Shagging?

Good lord, it must have been a slow news day at The Guardian. They’ve published a column about the proposed tightening of anti-bestiality laws in Germany. For some reason, they also chose to illustrate the article with a photo of an American soldier kissing a British woman on VJ Day in 1945. (O.k., here’s a reason: The editors were just delighted to be able to project allegations of sexual weirdness onto anyone other than the British.) Anyway, here’s the interesting part:

There’s a vulgar joke about a man who complained of a double standard between himself and his fellow villagers: “My neighbour went bungee jumping. Once. And nobody calls him Bertram the bungee jumper. My other neighbour went to the beach. Once. Yet nobody calls him Gunther the beachgoer. But me? I shag just one goat …”

Whatever reputation the man would have acquired in Germany, he would at least have avoided legal repercussions – until now. Germany is banning bestiality, which has been legal there since 1969. The problem is consent – animals can’t give it.

Zoophiles, people who have sex with animals, are suing the German government, however, demanding the continuation of their right to practise bestiality.

You can read the rest of the article here. But take my advice: Don’t. Just savor the weird idea that anyone would come out of the barn long enough to unite on behalf of bestiality.

I’m not sure what the writer had in mind, other than meeting a deadline. But she goes on to take sheep-shagging laws in Europe as the starting point for a discussion of U.S. laws banning various sex acts between consenting adults. Adult humans, I mean.

I am thinking this will not attract anyone to saying anything but “ewwww.” Or maybe: “Ewe.”

The Species Seekers: “A Delightful Book”

Just in time for the holidays, Australia’s science magazine Cosmos has published a review calling The Species Seekers “a delightful book … compelling for its human stories, anecdotes and well-woven storylines.”

“OUR PERFECT NATURALIST,” Charles Kingsley wrote in 1855, “should be strong in body; able to haul a dredge, climb a rock, turn a boulder, walk all day… be able on occasion to fight for his life.”

Kingsley later lampooned the naturalists he so romantically described, in his children’s book The Water Babies, which features Professor Ptthmllnsprts, who collected new species, and, yes, put them all in spirits.

The 19th century saw a revival of interest in the natural world that pulled at the marrow of a set of (mostly) men who dedicated their lives to collecting, labelling, storing and studying the bewildering diversity of life on Earth. They were “fired with a longing” to explore the “romantic land where all the birds and animals were of the museum varieties”, according to the account of one anonymous explorer in Richard Conniff’s rich and fascinating book.

From Wallace to Darwin, and U.S. founding father Thomas Jefferson to brilliant, ruthless anatomist and anti-Darwinist Richard Owen, the 19th-century species seekers were a fascinating cohort of explorers and scientists, showmen and geeks. Darwin would muse over a “wonderfully developed” barnacle penis lying “coiled up, like a great worm”, while ever-active Alfred Wallace “trembled with excitement” as he saw a particularly spectacular butterfly “come majestically toward me”.

Even the more prosaic Charles Willson Peale, the entrepreneurial father of the museum, said his “heart jumped with joy” at procuring a particularly impressive and almost complete mastodon skeleton, which he paraded around the streets to entice the eager public to view his collection.

This is a delightful book from a seasoned and skilful writer, compelling for its human stories, anecdotes and well-woven storylines and its retelling of a golden age of science.

December 2, 2012

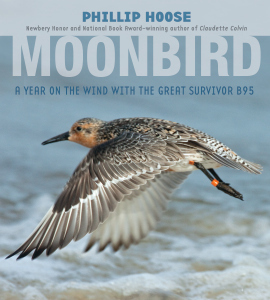

A Moonbird Among the Waning Red Knots

Red knot taking wing (Courtesy of Farrar Straus Giroux)

One day in February 1995, on a beach in Tierra del Fuego, a team of researchers equipped with a cannon net trapped and banded 850 shorebirds known as red knots. Among them was an adult male, at least three years old, who would become a legend in the birding world as B95, or Moonbird.

The red knot is a relatively large sandpiper, with a pointy mid-length bill, a dappled brown-and-black back, and in mating season a rust-colored face and abdomen. The way red knots race nimbly along the tide line searching for food apparently reminded the Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus of the Scandinavian King Canute, famous for calling on his royal dignity to keep the tides from washing around his feet.Hence Linnaeus named the species Calidris canutus.

But the real story of the red knot, and particularly of the subspecies rufa, is their extraordinary migratory behavior, which scientists have begun to understand only over the past few decades. Phillip Hoose brings that story up to date in his latest book Moonbird: A Year on the Wind with the Great Survivor B95 (Farrar, Straus, Giroux).

But the real story of the red knot, and particularly of the subspecies rufa, is their extraordinary migratory behavior, which scientists have begun to understand only over the past few decades. Phillip Hoose brings that story up to date in his latest book Moonbird: A Year on the Wind with the Great Survivor B95 (Farrar, Straus, Giroux).

“B95 can feel it: A stirring in his bones and feathers,” Hoose begins. “It’s time. Today is the day he will once again cast himself into the air, spiral upward into the clouds, and bank into the wind. … He has packed all the fuel he can, gorging on worms, clams, mussels, and tiny crustaceans. His inner GPS is set for north. The whole flock is rippling with anticipation. …”

Every spring these birds, “among the toughest four ounces of life in the world,” make a 9,000-mile trip from Tierra del Fuego, at the farther end of Argentina, to breeding grounds on an Arctic island at the top of Canada’s Hudson Bay. Then, having reared a new generation, they turn around every fall and head 9,000 miles south again. (Other red knot subspecies travel from their Arctic breeding sites to South Africa, Australia, India and other southerly destinations.) It is a highly demanding way of life and, not surprisingly, the average lifespan for a red knot is only six or seven years.

B95 was different. He began to intrigue ornithologists because he kept at it year after year, logging enough mileage, someone calculated at one point, to get to the moon and halfway back. Moonbird, as people began to call him, caught Hoose’s interest in 2009 for a somewhat more complicated reason. When scientists first banded B95, they estimated that 150,000 birds in the subspecies rufa were making this heroic odyssey. Today, for no certain reason, the population has plummeted to just 25,000, putting it on a trajectory to join this era’s slow-motion tragedy of mass species extinction. B95, Hoose writes, “is a bird of the Sixth Wave”—that is, the sixth mass extinction in the history of the Earth.

Hoose (Photo: Gordon Chibroski Portland Newspapers)

Hoose had been hoping to address the great extinction crisis of our day with an earlier book, The Race to Save the Lord God Bird,about the loss of the ivory-billed woodpecker. The Nature Conservancy, where he is a conservation planner, sent him on the road for a year to bring the reality of extinction home to audiences and deliver a simple message: “Extinction is preventable.” But in the middle of his tour, headlines around the world reported the tantalizing news that naturalists thought they may have glimpsed a living ivory-billed woodpecker in the Arkansas woods.

“After that, the only question anybody wanted to ask was ‘Do you believe? Do you believe that bird was the ivory-billed woodpecker?’ You were damned either way. If you said you believed, you could hear people smirking. If you said no, you were a killjoy.” It left Hoose at a loss: “It was an Elvis-like thing. The bird came to represent something imaginary in the wilderness.” He went off instead to work on a book about a young civil rights heroine, Claudette Colvin, for which he won the National Book Award.

The right way to deal with the extinction crisis, he thought, was to hold out for a poster child, not an entire species, but one individual with a compelling story capable of stirring up powerful human emotions. Eventually, the phone call came from a friend, Charles Duncan, head of the shorebird recovery program at the Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences in Massachusetts, saying, “I think I have your bird.”

##

By 2009, when Hoose traveled to Tierra del Fuego to begin work on Moonbird, B95 was already at least 17 years old, older than any other rufa Red Knot on record. He had been recaptured three times, most recently in 2007, by a startled scientist, who recognizing him, at first uttered “Oh, my God,” and then went to work, quickly taking all the usual measurements. “His weight was where it should be,” he later recalled. “He had wonderful plumage. He was as fit as a three-year-old. I was holding a superbird in my hand.”

Animals can intrigue us for several reasons, but one of them is how they adapt to all the far-flung, seasonal opportunities of life on Earth. B95 and his fellow rufa Red Knots travel to Tierra del Fuego every November, Hoose writes, because the reddish-brown restinga tidal flats there are packed with juvenile mussels still soft enough and loosely enough anchored “for the tug of a ravenous red knot’s bill.” The long hours of daylight in the extreme south then also mean that the tidal flats are exposed for two brightly lighted feeding sessions a day.

Thus B95 can double his weight until he looks bloated and beady-eyed before migration. It’s mostly fat, which is better for long-distance flight because it packs eight times the energy per ounce as protein. At the same time, B95’s heart enlarges to pump blood to his flight muscles, and he shelves many internal organs: “His liver and gut shrivel, as do the muscles in his legs. His gizzard—an organ that grinds food—decreases in size by nearly half, meaning he will be able to eat only soft food when he stops to refuel.”

These changes also mean that B95 and his flock depend on having the right foods available on his route. But it wasn’t until May 1979 that researchers discovered rufa’s single most important feeding site on the long trip north. The flight from northern South America to the Delaware Bay is almost 5,000 miles long and can last more than six days, much of it across open water. B95 and his flock make the drop into Cape May, N.J., “panting for oxygen, with bones protruding, desperate for food.” To rebuild for the final 2,000-mile run up to the Arctic, these birds must each manage the equivalent of a human gaining 10 pounds a day. Happily, just in time for their arrival, horseshoe crabs are littering the tidal zone with their soft, nutrient-packed eggs.

In the early1990s, however, commercial fishermen suddenly realized that the horseshoe crab mating season in Delaware Bay made easy pickings for the bait trade. “For a few unregulated years, it was a gold rush,” Hoose told his audience during a recent talk at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. “Out-of-state vehicles drove up and paid locals a pittance for every horseshoe crab they could gather.” On any given day at that time of year, 90 percent of the entire rufa population can be working the beaches of Delaware Bay, and they apparently felt the competition. Over a two-year period, from 2000 to 2002, half of all adult rufa red knots died.

Around Delaware Bay, some state and local authorities have responded by shutting down beach access during mating season and by limiting the horseshoe crab trade. Argentina has also taken steps to protect wetlands critical to shorebirds. But so far, the effort hasn’t placed rufa red knots securely on the path to recovery.

One new plan now in the works would ramp up the supply of food in Delaware Bay with a form of horseshoe crab egg-banking. University of New Haven marine scientist Carmela Cuomo, Ph.D. ’84, has developed a technique for getting horseshoe crabs to lay eggs in captivity, with a projected harvest of up to 5 million eggs per season. Other researchers have begun placing tiny geolocators on rufa red knots to develop a more complete picture of their migration. Finally, a Delaware Bay student group, Friends of the Red Knot, has launched a letter-writing campaign to get the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list rufa as endangered.

Through it all, even as 80 percent of the subspecies has faded into oblivion, B95 has continued to fly. “How can this one bird keep going year after year when so many of his companions drop from the sky or perish on the beaches?” Hoose writes. Maybe it’s good genes, or good luck, like people who live to 100, he told his audience at Yale. Or maybe B95 just has “a gift for the middle of the flock, so he has protection when the peregrine falcons try to harry a single individual out of the flock.” He is, in any case, clearly a smart, adaptable and enduring creature. “Why would you ever let something like that go?” Hoose said. “You can just let biodiversity go, or you can think of each living species as a survivor, as a triumph, as a success story. The trick is not to wipe them out, but to learn to live with them on their terms.”

Hoose was delivering this message at a Nature Conservancy staff meeting last May, just as his book was being published. Then a text message came in from a researcher back on Delaware Bay. On a whim, she’d gone out on the deck to the spotting scope and trained it on the beach. And as if by magic, there he was, B95, Moonbird, with all of his characteristic markings in perfect focus. A photograph confirmed the sighting.

The text message said simply, “I just saw him.”

“Market-based Conservation” = $$$ For Wolf Hunting

A few weeks ago I wrote about the perils of the market-based “ecosystem services” approach to conservation. Now the New York Times reports a case in point. The State of Utah has begun allowing private landowners to sell permits for private hunts on their property for thousands of dollars. The idea, seemingly a sensible one, is to give ranchers a cash incentive to tolerate–and even cultivate–wildlife. But listen to how it has worked out:

Critics of the auction and the convention drawing, like Tye Boulter, the president of the United Wildlife Cooperative, said that too much of the money made by the Mule Deer Foundation and Sportsmen for Wildlife went to promoting the groups and lobbying for their political causes.

But Mr. Moretti said, “We believe we’ve fulfilled our obligation” to bring in convention dollars and support wildlife projects.

An audit of the $1 million from the convention drawing was made public in August, prompted by Mr. Boulter’s complaints. It showed that about $250,000 went toward lobbying for increased hunting of wolves, which at the time were still listed as endangered in the Northern Rockies. “They are catering to the industry — guides, outfitters, landowners, things like that,” Mr. Boulter argued, saying groups that support wolf hunts are not necessarily conservationists.

Check out the whole article here.