Richard Conniff's Blog, page 71

July 23, 2013

Hello, DreamWorks? King Julien Calling.

King Julien and Friend

I spent some time with lemurs in Madagascar a few years ago. So the idea that they may disappear from the Earth has gotten stuck in my head this morning. So let’s take another look at those numbers.

Saving the northern sportive lemur will cost just $25,000 a year, to put full-times guards in the field. Overall, the IUCN figures that the program to get all 104 lemur species through the next three years will cost $7.6 million.

To put that number in perspective, the three “Madagascar” animated movies released by DreamWorks Animation since 2005 have so far earned about $1.9 billion worldwide, with another sequel now in development.

Also by way of perspective, DreamWorks founders Stephen Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and David Geffen recently donated $90 million … to support elderly members of the entertainment industry.

It is of course a wonderful thing to help those who helped get you where you are. And this reminds me of King Julien, the colorful lemur on whose charm DreamWorks has developed one of the most lucrative franchises in the history of entertainment.

If readers agree with me that DreamWorks, together with Spielberg, Katzenberg, and Geffen (who is no longer associated with the company), could together go a long way toward saving the colorful tribe of lemur species, why don’t we let them know right now.

You can contact the DreamWorks board at this address. Or go to Twitter and post this message: Save King Julien and his tribe of lemur species #dreamworks #savethelemurs http://www.takepart.com/article/2013/07/22/northern-sportive-lemur-extinct

Stephen? Jeffrey? David? King Julien wants to know: Isn’t it time the lemurs got a little payback, too?

Dead Primate Walking

No primate species is known to have gone extinct during the last 200 years. But that’s almost certain to change dramatically over the next decade, and the first to go may be a mild nocturnal lemur with huge amber eyes.

No primate species is known to have gone extinct during the last 200 years. But that’s almost certain to change dramatically over the next decade, and the first to go may be a mild nocturnal lemur with huge amber eyes.

The northern sportive lemur (Lepilemur septentrionalis) is now thought to be down to just 19 individuals, living in two dwindling patches of tropical dry forest at the northern tip of Madagascar. The larger patch is just under 200 acres—about a quarter of the size of Central Park in Manhattan.

If that word “sportive” brings to mind the flamboyant ring-tailed lemur, King Julien, voiced by Sacha Baron Cohen in the Madagascar animated movie series, hold that thought for a bit.

In fact, the northern sportive lemur is a decidedly sedate and uncharismatic creature, eight inches tall, with gray brown fur, weighing under two pounds. It spends its nights steadily feeding on whatever leaves it can still find. By day, it perches at the mouth of its tree trunk nest hole, soaking up the sun.

The British apparently applied the term “sportive” to species in the genus Lepilemur either because they adopt a boxer-like stance when threatened, or because of the way they leap from a vertical position on a tree trunk. But leaf-eating makes for a low-energy diet, and compared to the balletic movements of sifaka lemurs, for instance, the sportive lemurs are “really rather sluggish,” says primatologist Christoph Schwitzer. “You need a radio collar to follow them, because they leap from tree to tree. But they can’t keep that up for long because they run out of fuel.” The truth, he says, is that “nobody really knows why the British called them sportive. In German, they’re wieselmaki, or weasel monkeys.”

The main threat to the continued survival of the northern sportive lemur (and most of the other lemur species in Madagascar) comes from local villagers gathering wood either for cooking or to turn into charcoal for sale in the city. The Malagasy still practice slash-and-burn agriculture, as well. That means cutting down and burning a patch of forest, using the ashes to make the nutrient-poor tropical soil fertile, and then moving on to a new patch after two or three years.

“It was sustainable when there were only a few people living on Madagascar,” says Schwitzer, who is vice chair of the Madagascar primate specialist group for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). But there are now 21 million people on this island off the southeast coast of Africa, and only about 15 percent of its original forest remains intact.

The continued survival of the lemurs is also at risk because of political and economic turmoil following the 2009 overthrow of Madagascar’s last democratically elected government. That coup forced most international aid organizations to pull out, and Madagascar, already among the poorest nations on Earth, became significantly poorer. Bushmeat hunting of lemurs, which was rare in the past, has become increasingly common.

Early this year, the World Bank returned to Madagascar with the promise of substantial new aid. But election of a new national government, originally scheduled to take place this week, has been repeatedly postponed.

Madagascar should be doing far better, says Schwitzer. It has substantial petroleum, iron ore, and sapphire reserves, and its motherlode of rare and colorful animal species should be the basis for a thriving tourist economy. “For such a country to be so poor is crazy,” he adds. “It has to do with a recurring political crisis every 10 years and people not getting their act together.”

And that puts lemurs on death row. When the IUCN issues its new three-year lemur conservation strategy later this month, it will report that more than 90 percent of Madagascar’s 104 lemur species are now vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered.

Captive breeding might sound like the logical next step for the northern sportive lemur. But with only 19 individuals in the wild, it’s hard to justify pulling out part of the population for a captive breeding program, especially when the likelihood of failure is so high. The lemur’s leafy diet is difficult to replicate in a zoo, particularly because most science-based zoo programs are in the northern hemisphere, where leaves are unavailable in winter.

To keep the northern sportive lemur from becoming extinct over the next three years, the IUCN is proposing to place forest guards in the field round the clock. “You have to get somebody on ’em 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and they have to know where every animal is,” says Russ Mittermeier, chair of the IUCN primate specialist group and president of Conservation International. “Otherwise, if somebody decides to go out lemur hunting, the species is gone.”

The good news is that the program to put guards in the field will cost only $25,000 a year. And given proper protection, lemurs can rebound even from very small population numbers. (Mittermeier says that if readers want to make a donation and have it go 100 percent toward the cost of those guards, you should mark your donation for that purpose and address it to his attention at Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202.)

Overall, the IUCN figures that to get all 104 lemur species through the next three years will cost $7.6 million. To put that number in perspective, the three Madagascar animated movies released by DreamWorks Animation since 2005 have so far earned about $1.9 billion worldwide, with another sequel now in development.

Maybe this would be a good time for the DreamWorks team to send a little thank you cash to King Julien‘s family.

July 18, 2013

Behind the Scenes at The Truman Show for Ants

My new post for TakePart:

Even in the arcane world of ant behavior, the right headline can make all the difference. Back in May, Danielle Mersch and her colleagues at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland published an article in Science.They got very little attention for it, perhaps because the headline wasn’t exactly an attention-grabber: “Tracking Individuals Shows Spatial Fidelity Is a Key Regulator of Ant Social Organization.”

But a new article, just published in Current Biology, gives Mersch’s work the spin it clearly deserves. Under the headline “Animal Behavior: The Truman Show for Ants,” the authors describe how the system Mersch’s team devised to track the second-by-second movements of every individual in an ant colony resembles the popular 1998 film starring Jim Carrey. In that film, Truman Burbank, played by Carrey, belatedly discovers that his entire life has been a reality show produced and managed for broadcast.

At Mersch’s laboratory in Lausanne, the lives being recorded take place in a row of Styrofoam boxes, each about the size of a bar refrigerator, lined up on a counter. A computer precisely controls temperature and humidity inside each box, where a colony of about 150 carpenter ants (Camponotus fellah) goes back and forth between daytime and nighttime compartments. Mersch has 11 separate colonies under watch at the moment. Like Truman before he wakes up, the ants are apparently oblivious that the outside world is looking in, though every ant carries a barcode-like placard on its back, for automated identification, and an overhead camera … to read the rest of this post click here.

July 15, 2013

Underwater Vampire Sex

Rock sucker ( (Photo: Courtesy of Cory O. Brant, Michigan State University)

This is my latest for TakePart.com. The lovely headline is from my editor Sarah Fuss, who gets the SEO prize for headline of the week, I think. (SEO, for those of you happily unaware of the peculiar ways of the internet, stands for search engine optimization, and the trick is to choose your first three words in such a way that no sentient human can help but double-click. Sarah’s three words hit the nail on the head, I think, or maybe drive the stake into the heart of SEO.)

Animals don’t come much uglier than the sea lamprey. It’s a 550-million-year-old eel-like species, typically less than 20 inches in length. In place of a mouth and a jaw, it has an oral disk. Think of a suction cup, but studded across the inner surface with wicked little teeth. (Photo at right: Luis Fernandez Garcia/Wikimedia)

In the Great Lakes, it uses this formidable instrument to latch onto trout, whitefish, and other species. Then it rips through the skin with its razor sharp tongue and slowly sucks out its victim’s blood and other bodily fluids.

Now a new study takes a closer look at the sex lives of these aquatic vampires and makes it sound—not too surprisingly—like a bad night at a leather bar. Writing in The Journal of Experimental Biology, Michigan State University researcher Weiming Li and his co-authors set out to determine the function of a swollen ridge called “the rope” that develops just ahead of the front dorsal fin in mature males. It turns out that the rope makes males hot, literally and figuratively… to read the rest of this story, click here.

July 11, 2013

Saving the Monarch Migration

Here’s my latest blog item at TakePart:

It’s been a dismal year for North America’s favorite migratory species, the monarch butterfly, beginning with the report that populations at overwintering sites in Mexico were down 59 percent from the previous winter. When researchers there measured the total area of trees occupied by monarchs—the stock for most of the continent—it added up to less three acres, an all-time low.

Nothing about the spring migration, which recently ended, gave new cause for hope. Monarch numbers are now so low that any catastrophic event could “send the population spinning downward even more,” says University of Kansas insect ecologist Chip Taylor, whose advocacy group Monarch Watch works to protect and rebuild monarch butterfly populations. The thin population could weaken conservation efforts, he says, “because if you don’t see them, you don’t have the motivation to do something about it.” He expects that the numbers will probably go even lower this coming winter.

The tendency is to blame the problem on Mexico, where logging of critical forests has been a perennial issue. Taylor says Mexico has made “a terrific effort to control illegal logging” and has largely put a stop to “the organized mafia-like groups that go in there with guns and cut down a hectare of forest in one night.” But serious incidents still sometimes occur.

A far larger problem, though, is the increasing intensity and efficiency of agriculture in the United States. Taylor dates the dramatic decline in monarch butterflies to the introduction of Roundup Ready corn and soybeans by the Monsanto Co. in the late 1990s. Until then … to read the rest of this post, click here.

July 9, 2013

Frogs on Ice: A Way to Save Amphibians

For one of the most colorful animal groups on Earth, the 21st century is looking a lot like the end of the world. Scientists suspect that 165 amphibian species—frogs, toads, newts, salamanders, and caecilians—have gone extinct over the past few decades. Another 2,000 species—roughly a third of the 6,260 known amphibians—are either threatened or endangered. That’s not counting the 1,500 species for which scientists lack adequate data. Habitat loss is the usual culprit, together with the worldwide amphibian pandemic commonly known as chytrid fungus.

For one of the most colorful animal groups on Earth, the 21st century is looking a lot like the end of the world. Scientists suspect that 165 amphibian species—frogs, toads, newts, salamanders, and caecilians—have gone extinct over the past few decades. Another 2,000 species—roughly a third of the 6,260 known amphibians—are either threatened or endangered. That’s not counting the 1,500 species for which scientists lack adequate data. Habitat loss is the usual culprit, together with the worldwide amphibian pandemic commonly known as chytrid fungus.

But a team of researchers from eight countries, writing in the journal Biological Conservation, now proposes a slender thread of hope in the form of “biobanking,” the preservation of genetic material for amphibian species. In the face of “what seems to be an inevitable march of destruction and loss,” the authors write, their proposal amounts to “an eleventh hour, last-ditch effort” to save what could amount to the entire taxonomic class Amphibia.

It may sound a bit like science fiction: A liquid nitrogen tank taking up half the space of a typical desk can hold sperm samples from hundreds of individuals. Some may be used next month, or ten years from now, to help save a species. Others may be stored away for 200 or 300 years, to be resurrected in some future world that, with luck, will be more hospitable than the one amphibians now face on Earth. Like candidates for flight to a distant planet, donor amphibians must have the right stuff: Lab technicians screen them to ensure that … to read the full story, click here.

It may sound a bit like science fiction: A liquid nitrogen tank taking up half the space of a typical desk can hold sperm samples from hundreds of individuals. Some may be used next month, or ten years from now, to help save a species. Others may be stored away for 200 or 300 years, to be resurrected in some future world that, with luck, will be more hospitable than the one amphibians now face on Earth. Like candidates for flight to a distant planet, donor amphibians must have the right stuff: Lab technicians screen them to ensure that … to read the full story, click here.

July 8, 2013

A Rhino with No Horns: What the World Needs Now

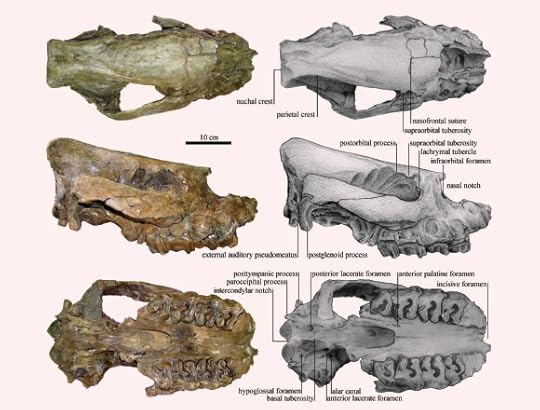

Reconstruction of the Late Miocene habitat of Aceratherium piriyai at Tha Chang

This is just what we need for the modern world–a rhino with no horns. The bad news: It’s already extinct.

Here’s James A. Foley’s account from NatureWorldNews:

A new but extinct species of hornless rhinoceros has been identified by fossils uncovered in Thailand.

Local villagers working in sand pits located about 140 miles northeast of Bangkok found the fossils, which were turned in to experts and later identified as “a mid-sized rhinocerotid in the subfamily Aceratheriinae, and represents the first discovery of Aceratherium in Thailand,” according to the abstract of the description of the new species written in the Journal of Vertebrate Pathology.

The hornless rhino was named Aceratherium porpani in honor of Porpan Vachajitpan, who donated the specimens to science, according to Sci-News.com

Aceratheriinae is an extinct subfamily of the rhinoceros that lived through the Pliocene era, which ended 3.4 million years ago.

In their description of the new species, the researchers indicate the creature had smaller-than-usual teeth, which are indicative of a woodland habitat. Paleobotanical evidence from the Tha Chang sand pits regions where the species was uncovered is consistent with description of A.porpani’s habitat.

The description of the news species a was based on a jaw bone and partial skull, which is now housed in Northeastern Research Institute of Petrified Wood and Mineral Resources, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand.

There are two other known species of Aceratherium and the latest find exhibits a mixture of characteristics that are primitive to and derived from the other known species, suggesting that it lived at a point in time somewhere in the middle of the other two.

Holotype skull of Aceratherium piriyai sp. nov. (Credit: Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences)

Killer Rats and Monster Cockroaches

Life on the little ecosystem of a ship at sea can be strange, and two items I happened to come across today made me stop and think about that. The first is a report in the current issue of the scholarly journalAnimal Behaviour with the curious title “Do ship rats display predatory behaviour towards house mice?”

Life on the little ecosystem of a ship at sea can be strange, and two items I happened to come across today made me stop and think about that. The first is a report in the current issue of the scholarly journalAnimal Behaviour with the curious title “Do ship rats display predatory behaviour towards house mice?”

This is probably not the question you wake up thinking about most mornings, unless you happen to be aboard one of our leading cruise ships. But a group of experts in New Zealand set out to answer the question for an eminently practical reason: They want to eliminate ship rats (Rattus rattus) from local forests, where the invasive and highly aggressive rats are a deadly threat to nesting birds and other native species. But when they manage to get rid of the rats, the population of invasive house mice just increases to fill the gap. And the mice are a problem too.

In the interest of getting rid of both, the researchers wanted to know: Are the rats just scaring off the mice? Or do they actually prey on them?

It’s always entertaining to find out how scientists answer such questions, especially given the requirement to do so humanely. In this case, the co-authors report, “Dead mice were attached to fishing line … to read the rest of this story, click here.

July 3, 2013

Saving Butchered Rhinos

Black rhino in South Africa (Photo: Richard Conniff)

In the middle of a war on rhinos, it’s easy to get desensitized by endless photographs of horribly butchered corpses. South Africa alone has already lost 428 animals so far this year, their horns hacked off with chainsaws and machetes to supply the traditional Chinese medicine trade. But what happens when an animal survives the butchery?

Will Fowlds, a 42-year-old veterinarian, was living at Amakhala Game Reserve outside Port Elizabeth, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, when he got the call in February 2011. Poachers had attacked a rhino on a neighboring reserve. After a moment, the owner of the reserve added, “William, he’s still alive.”

When Fowlds arrived at the scene, the owner simply pointed him into the bush. He’d already seen too much. Fowlds found the rhino propped up on three legs, with his mouth pushed into the ground as a kind of crutch. His left front leg was crippled, from having been caught under his own massive weight after the poachers’ tranquilizer knocked him out. His face was hacked open, with loose flesh hanging off either side. Blood bubbled in the exposed nasal passages.

The rhino saw Fowlds and stumbled toward him … to read the rest of this story click here.

June 28, 2013

New Bird in the Big City

We live in a great age of species discovery, with scientists describing new and spectactular creatures at a rate that would fill the explorers of the Victorian era with sheer envy. The usual explanation is that modern researchers get to explore remote forests and mountaintops that used to be inaccessible.

We live in a great age of species discovery, with scientists describing new and spectactular creatures at a rate that would fill the explorers of the Victorian era with sheer envy. The usual explanation is that modern researchers get to explore remote forests and mountaintops that used to be inaccessible.

But sometimes a sensational species can turn up even in our own backyards. Something like that happened to Simon Mahood, an ecologist for the Wildlife Conservation Society, who has just described a colorful new bird species found less than a half-hour from his home, in the heart of Cambodia’s crowded capital city Phnom Penh.

The new species is wren-sized gray bird with a cinnamon cap, white cheeks, and a black throat, and it’s one of just two birds species that are found only in Cambodia. Hence its new common name, the Cambodian tailorbird. In an article published in the Oriental Bird Club’s journal Forktail, Mahood and his co-authors have given it the scientific name Orthotomus chaktomuk. Mahood explains that Phnom Penh was historically known as “krong chaktomuk,” meaning “city of four faces.” It’s a reference to the low lying area where four rivers come together downtown.

The new species first turned up in January 2009, when … To read the full article, click here.