Richard Conniff's Blog, page 68

September 19, 2013

The Fraud Hunter

(Photo: Julie Brown)

I’m back in the territory of my book, The Natural History of the Rich, for this story. It’s my profile of Jim Chanos, the most successful short-seller in the world, and a Sherlock Holmes of corporate bad behavior.

Here’s an excerpt:

You would think that by now financial types would stop to listen when Chanos says “Uh-oh.” He has been raising the red flag on companies—from the merely troubled to the outright fraudulent—for more than 30 years, often while corporate executives and Wall Street analysts were still eagerly flogging those companies to gullible buyers. “He’s been pretty much right about everything,” says Nell Minow, a leading advocate for responsible corporate governance. “He’s a smart guy.” The investments he has shorted constitute a nearly complete chronicle of bad business behavior in our time. The most famous among them landed Chanos on the cover of Barron’s in 2002 as “The Guy Who Called Enron.” But the list of his targets stretches from Michael Milken’s junk bond empire through the real estate boom of the late 1980s, the telecom bubble of the late 1990s, Dennis Kozlowski’s Tyco and Bernie Ebbers’s WorldCom at the turn of the century, subprime mortgage lenders and homebuilders in 2007, and most recently an entire nation. (China, he says, is “on an economic treadmill to hell.”)

Chanos has inevitably also been wrong about some companies—or right, but

You can read the whole article as published in the Yale Alumni Magazine here. Or …

The magazine had to cut slightly for space. So here’s the story as written. One caveat: Their fact checking process picked up a few minor mistakes I had made (Chanos didn’t apparently put the hockey puck through the window; it was his teammate).

So go with the published version for accuracy:

On a muggy Thursday in the dog days of August 2011, the news broke that the American technology giant Hewlett-Packard was about to acquire British software maker Autonomy Corp. The offer price represented a 64 percent premium on the previous day’s close. At his office in mid-Manhattan, hedge fund manager Jim Chanos ‘80 did not rejoice.

Only a few weeks earlier, his firm, Kynikos Associates, had put together a report on Autonomy, calling its chief operating officer unqualified, its customers unenthusiastic, its market share and growth numbers questionable, its financial disclosures “very poor,” and its margin profile “suspiciously high.”

“We thought this was one of the great shorts of all time,” says Chanos, who specializes in ferreting out corporate bad behavior and then short-selling the companies that indulge in it. (That is, he borrows shares in a company and sells them at the current price, in the expectation that he will be able to pay back the loan, or “cover the short,” with shares purchased at a much lower price when the ugly truth comes out.)

The rules at Kynikos preclude investing more than five percent of its assets in any single position. But with $6 billion under management, that could mean as much as $300 million, and Autonomy was the firm’s largest short position in Europe. So Hewlett-Packard’s decision to more than double the value of the company, to $11.7 billion, was—and here Chanos laughs –“very painful.”

Chanos passed along a copy of his Autonomy analysis to a friend who had friends on the board at H-P, saying “You should look at this. This is going to be a disaster.” The deal closed anyway, and Chanos was soon shorting H-P as enthusiastically as he had shorted Autonomy. Thirteen months later, in November last year, H-P management belatedly woke up, announced that it was shocked to find itself in bed with “serious accounting improprieties” at Autonomy–and handed shareholders an $8.8 billion loss on the deal. By then, Chanos had already covered his short, pocketed the profits, and moved on.

You would think that by now financial types would stop to listen when Chanos says “Uh-oh.” He has been raising the red flag on troubled companies for more than 30 years, often while corporate executives and Wall Street analysts were still eagerly flogging those companies to gullible buyers. And he has been right often enough that the investments he has shorted constitute a nearly complete chronicle of business bad behavior in our time. The most famous among them landed Chanos on the cover of Barron’s in 2002 as “The Guy Who Called Enron.” But the list of his targets stretches from Michael Milken’s junk bond empire through the real estate boom of the 1980s, the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, Dennis Kozlowski’s Tyco and Bernie Ebbers’s Worldcom at the turn of the century, subprime mortgage lenders and homebuilders in 2007, and most recently an entire nation. (China, he says, is “on an economic treadmill to hell.”)

Chanos has inevitably also been wrong about some companies– or right, but too soon, as with his first go-round on Autonomy. He has taken losses, sometimes for years on end that, according to a longtime-friend, would make an ordinary man “go out and shoot himself.” Even so, he has managed not only to survive but to prosper and put an exuberant face on a notoriously treacherous line of work. “Jim Chanos,” International Business Times declared in 2011, “is the best short-seller in the world.”

In certain circles, this is a bit like saying he is the world’s best agent of Satan. But Chanos turns out to be a more complex character than the labels “hedge fund manager” and “short-seller” might suggest.

##

“I hope you are here,” Chanos tells a packed classroom at the Yale School of Management, on a Monday afternoon in March, “for ‘Financial Fraud Through History: A Forensic Approach’ and not for ‘How to Run a Hedge Fund 101.’” He’s just flown up from a weekend in Florida. His hair, still sand-colored at 55, sweeps down over his forehead. He wears thick-lensed rimless eyeglasses, and a blue blazer over a purple cashmere sweater, which makes him look momentarily like an Episcopalian minister gone astray. But he quickly reveals himself to be a confident guide to the topic he will be covering for three hours, once a week, over the next eight weeks, “the rogues and charlatans” who have cheated investors down through history.

Chanos has been teaching this class for three years now, starting soon after he mentioned to then-Yale President Richard Levin that his fantasy was to come back to New Haven to earn a graduate degree in history. As an undergraduate, Chanos had been a student of Levin’s. (“He says the only reason I uncovered Enron was because of what I learned in Econ 130.”) Levin countered that Yale’s fantasy was to have Chanos teach. Then, says Chanos, Levin heard the course description and had second thoughts: “He said, ‘You’re not going to teach them how to commit fraud, are you?’”

That’s not the plan, Chanos tells the class, though one or two students may perhaps cross that line. But it is “almost inevitable that you will come across fraud in the course of your careers.” It has already happened to a former student in this class, whose first job confronted him with a discrepancy that ultimately ended up in the corporation counsel’s office. Corruption is everywhere in the business world, he warns them, citing one survey in which 45 percent of chief financial officers said their CEOs had asked them to falsify financial results, and more than a third had complied. In another survey, corporate executives estimated that one in five publicly traded companies manipulate their earnings to misrepresent quarterly performance.

The point of the class, Chanos tells his students, is always to look beyond face value and to spot the fudging and the fraud in time to protect their employers, as well as their own wallets and reputations. Just such a moment of recognition, early in his own career, set him on the thin line between finding his calling and getting fired.

##

Chanos grew up in a Milwaukee suburb, in a Greek immigrant family that operated a chain of dry-cleaning shops. He helped pay his way through college with a summer job as a union steel worker. At Yale, he majored in economics and political science, with a minor in laconic and often self-deprecating humor: The quotation he chose for the 1980 yearbook was “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes,” and his future career ambition was “world leader.” His non-academic credentials included two years as social chairman at Davenport College, where he and his roommate, Keith Allain, now coach of the Yale hockey team, once inadvertently slapped a puck through the window of the master’s house. (Allain, who has described his former roommate as “one of those special guys who could light the candle at both ends and never get burned,” let Chanos go inside to explain the puck.)

After college, Chanos got his start as a bottom-rung analyst for Blyth Eastman Dillon in Chicago, working 80-hour weeks at $12,500 a year. It began to dawn on him, he says, that “I could’ve made more money shoveling snow in Milwaukee.” But when a group of partners split off to start their own firm, Gilford Securities, they took Chanos along. And there Baldwin-United Corp. entered his life.

Baldwin was a piano company that had transformed itself, by a series of acquisitions, into an insurance giant and Wall Street darling. When it announced its latest acquisition in the summer of 1982, Chanos got the job of figuring out if the proposed deal would be good for Gilford clients, among them the hedge fund titans George Soros and Michael Steinhardt. “And I started looking at this mess of a company and couldn’t figure out how they were making money and what their disclosures were saying.” Insurance accounting is different from regular corporate accounting, and bad insurance accounting even more so. “I was just simply calling up people and asking questions and trying to figure this thing out.” Then one night when he was working late his direct line rang. “Is this Jim Chanos?” the caller asked. “You’re the guy asking all the questions about Baldwin-United?”

“Yes,” Chanos answered. “Who’s this?”

“It’s not important who this is.” The caller proceeded to point Chanos to public files of correspondence between Baldwin and state insurance regulators in Arkansas.

“I kept saying, ‘Well, who is this? Who is this?’ This was before caller i.d. And I got a click. It was this Deep Throat moment. I went in the next day and told my boss, and he asked me if I’d been drinking.”

The files from Arkansas, where Baldwin had an insurance subsidiary, turned out to be a beginner’s guide to financial chicanery. Among other things, regulators there had belatedly discovered that Baldwin was using insurance reserves to finance its acquisitions. Chanos put out his report, saying sell Baldwin and sell it short, in mid-August, 1982, right at the start of what would become one of the longest bull markets in Wall Street history. Baldwin’s stock price promptly doubled. “So my sense of timing was impeccable,” says Chanos.

Soros, Steinhardt, and other clients were soon flushing money down the drain on his advice “and not happy about it.” The firm’s New York partner wanted to hand them the 24-year-old analyst’s head, but the Chicago partner fended him off. Chanos went home for the holidays feeling miserable about screwing up on his first real job. Then, on Christmas Eve, the Chicago partner phoned to give him the news: Arkansas had just seized the assets of Baldwin-United.

Until then, Chanos had never felt any predisposition to be a short-seller. But Baldwin was a good early lesson, he says, “because it was painful as heck and I was almost fired, and yet we were sitting on all this evidence that the market was ignoring. And it was completely accurate and completely predictive.” It dawned on him that “if you do your work and uncover things that the market either doesn’t see or doesn’t want to see, you might be able to do well by your clients.” Baldwin developed into what was then the biggest bankruptcy in corporate history, and the question soon came filtering down from clients: “What else does Chanos not like?”

##

Today Chanos manages his hedge fund out of a not-particularly grand office in a midtown neighborhood known more for art and restaurants than for high finance. (There’s also a London office, and for grandeur, he has an apartment on Fifth Avenue and a sprawling shingle-style house on the ocean in East Hampton.) The conference room features a library of financial calamity including such titles as Conspiracy of Fools, Mr. Market Miscalculates, and A Colossal Failure of Common Sense—bookended with bears, not bulls. The wall at the far end is decorated with a large photograph of what appears to be a red flag, in a moiré pattern. Or is that blood in the water? In his own office next door, Chanos has an Argentinean artist’s mockup of a work called “House of Cards.”

Though Chanos doesn’t put it quite this way, short-selling goes against some of the most basic proclivities of the financial marketplace—not to mention human nature and, some would say, God. It is an article of faith among investors that stock averages rise over the long term, and even market professionals tend to believe that their own chosen stocks will turn out, like children in Lake Wobegon, to be above average. Moreover, when an investor buys a stock the usual way, going long, the potential gain is limitless, at least in theory. But the potential losses stop when the stock hits zero. The really treacherous thing about short-selling is that it works the other way around: When an investor goes short, it’s the losses that can be limitless. And the agony can go on for months or even years as a bad company, puffed skyward by a charismatic CEO and a chorus of fawning analysts, ascends into the stock market heavens.

Beyond the financial pain, short selling also exacts a psychological toll. Stock markets are “giant positive reinforcement machines,” says Chanos, and they’re built for the sole purpose of selling stocks. “So almost everything is positive, everything is bullish.” The taboo against going negative is so powerful that when circumstances oblige analysts to badmouth a stock, they spell it H-O-L-D. The word “sell” turns up in just five percent of their recommendations, usually after a company has strewn flowers on its own grave. For short-sellers, that means the rest of the market is constantly shouting (sometimes literally and in the most personal terms) that they are wrong. And studies show “that people’s rational decision-making breaks down in an environment of negative reinforcement,” says Chanos. Good short sellers “drown it out. It means nothing to them. But I think most people can’t do that.”

Chanos got his first public taste of the corporate world’s ill will in 1985, when the Wall Street Journal ran a “blisteringly negative” front-page article, as he recalls it, about “this cabal of evil short-sellers.” Corporate executives and investors who had been “victimized” told the Journal that Chanos “epitomizes all that is wrong with modern short sellers.” The article alleged that Chanos and his ilk sometimes resorted to “innuendo, fabrications, and deceit to batter down a stock.” One company even hired detectives to investigate his business practices and pick through his garbage, the Journal reported, but came up with nothing more damaging than: “Chanos lives a nice, quiet yuppy existence.” Chanos denied any wrongdoing and otherwise shrugged it off, telling the Journal: “People think I have two horns and spread syphilis.”

Soon after, Chanos and a partner put together $1 million of their own capital and $15 million from a single client to form Kynikos. The name came from the Cynics, philosophers in Ancient Greece who stood for self-sufficiency, mental discipline, and proper judgments of value. Less conveniently, the Cynics also stood for poverty. One of them lived in a tub on the street. After a year of watching the stocks they had shorted rise in the continuing stock boom, Chanos’s partner couldn’t stand the negative reinforcement. He offered to sell his share for $1 so he could write off the tax loss and sleep at night. Chanos took the dollar bill out of his wallet on the spot, and the crash of 1987—good news for short-sellers– came soon after. “It was the best purchase I ever made, ironically,” says Chanos, and the ex-partner’s wife “still wants to kill him over it.”

Kynikos went on, however, to lose almost everything as the markets recovered in the first half of the 1990s. “We got clobbered,” Chanos says. Clients defected, the firm was on the brink of collapse, and he was paying staff out of his own pocket, while also supporting four young children. With his original clients, he eventually reorganized the firm and devised a compensation scheme that took overall market movements out of the calculation. (Like many hedge funds, Kynikos collects a one percent fee on the funds it manages and earns a 20 percent bonus. But contrary to the practice at some hedge funds, the bonus kicks in only on the amount by which its investments beat the market, which “is how it should be,” says Chanos.) Kynikos has prospered ever since, and Chanos has become widely respected, though perhaps still privately loathed, for his shrewd marketplace insights.

The peculiar chemistry that enables Chanos to handle the stress in bad times, and the negative reinforcement almost all the time, remains, however, largely a mystery, even to him. “Good short sellers have something in the DNA,” he offers. “It’s not just a research process. Or maybe we were dropped on our heads as babies.” His friend James Grant, publisher of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, is equally cryptic, quoting Bernard Baruch’s line about a celebrated financier being “all nerve—and no nerves.” It’s maybe not an absent of certain feelings, but an ability to set them aside. To blow off steam in the 1990s, Chanos says, he threw himself into playing basketball, working out, and lifting weights. (He benched-pressed 340 pounds last year, but says he is down to 310 at the moment.) When his gym on the Upper East Side was going bankrupt, he bought the place and now runs it at a loss, more or less happily. It is a vanity investment, times two

The other factor that may explain his buoyant personality– the Financial Times once aptly described him as “an inverse optimist”– is his sense of himself as a Wall Street outsider. This may seem improbable, given his wealth, his next-door neighbors, his long-time position as board chairman of a coveted Upper East Side private school, his frequent appearances on CNBC, and his many Yale connections. But until the early 1990s, Chanos was probably the only hedge fund manager who was also still a dues-paying member of the Boilermakers Union, a holdover from his summer job in college.

He also often talks an anti-management line, and not just because he’s shorting a company’s stock. In 2011, for instance, he spoke out in defense of the Occupy Wall Street movement: “People are angry,” he told a reporter, “they feel the game is rigged, that they didn’t get their fair shake.” When Hollywood director Oliver Stone took a second shot at the financial world in his “Wall Street” sequel, “Money Never Sleeps,” Chanos served as a consultant and even made a cameo appearance.

His sense of moral outrage at financial chicanery has at times trumped even his political loyalties. Chanos is a frequent contributor to Democratic candidates. (A right-wing website recently dubbed him “Obama’s Billionaire Playboy Bundler,” and a business friend jokes that he supports Democrats because that’s the quickest way to ruin the companies he has shorted.) But when Attorney General Eric Holder commented early this year that bringing criminal charges against some large companies is difficult because it might hurt the economy, Chanos lashed out, warning that “too big to jail” would further aggravate public mistrust of the markets. Then he went a step further, declaring that the last time the Justice Department demonstrated real leadership on corporate crime was when it put away executives from Enron, Tyco, and Worldcom—under President George W. Bush’s attorney general John Ashcroft.

##

In his class, Chanos constantly nudges his students to challenge established opinion. When one of them remarks that a scandal-ridden firm had a reputable auditor signing off on its reports, he remarks, “They all have reputable audit firms. That’s one thing I want you to take away from this course: Every big fraud had a great audit firm behind it.” He likens auditors and government regulators to archaeologists. “They’ll tell you what happened after the damage has been done.”

Chanos’s job—and what he tries to teach his class– is to get there in time to predict the damage: What were the signs that an outsider might have seen? What were the tip-offs? Are there patterns of bad behavior that repeat from one scandal to the next? Unlike some other hedge funds, Kynikos boasts no ingenious market model, no brilliant quantitative analysis, and, says Chanos, “no opinions on interest rates, or drilling offshore, or the dollar, or the Fed.” Instead, his brand of short-selling typically comes down to basic financial detective work. He seems to rely largely on a heightened instinct for bad behavior, a willingness to follow up with phone calls and legwork, and an inordinate appetite for hieroglyphic footnotes and disclosures buried deep in corporate 10-Q and 10 -K reports.

Chanos also routinely invites analysts and other interested parties to the conference room at Kynikos, mostly to persuade them that the bad news he has dug up is accurate, but also to find out if they have evidence to the contrary. It’s not exactly the disinterested pursuit of the truth, says his friend James Grant, but “really successful investors, including Jim, make it a point to be open-minded and seek out opinions, all in the interest of knowing everything they can about a situation, Jim has to have the facts.” Then he adds that Chanos would have made a good investigative reporter, “if only journalism paid as little as $25 million a year.”

As in journalism, good stories like Tyco and Enron have often started with a seemingly trivial item in the news. In mid-October 1999, for instance, Chanos was reading a New York Times roundtable discussion with business leaders. The interviewer asked a mild question about focusing too much on short-term results, and Dennis Kozlowski, CEO of Tyco International, jumped in to say “you absolutely have got to deliver what you promised in the short term” because missing the estimate by even a penny could instantly slice billions off the stock price. It was “a strong, strong answer to an innocuous question,” says Chanos. He promptly began digging through the company’s SEC filings.

A Kynikos analyst was soon also on the case, chatting up strangers at a fire alarm convention and discovering a Tyco scheme to misrepresent the purchase price when it acquired companies. Later, an investment banking friend mentioned to Chanos that Tyco was so hellbent on acquisitions that it insisted on seeing every potential deal above a certain size. When Chanos sympathized about having to constantly run deals up to Tyco’s famously frugal headquarters in New Hampshire, the friend replied, “What are you talking about? They’re at 9 W. 57th Street in the most opulent office you ever saw.” The Tyco dossier eventually included almost every trick for cooking the books in the repertoire of corporate scandals. Kynikos shorted the company in the high 50s, and within a year the price had dropped below 20. Kozlowski briefly made headlines for his $15,000 umbrella stand and his $6,000 shower curtain, and then moved on to become inmate No. 05A4820 at the Mid-State Correctional Facility in Marcy, New York.

Chanos’s role in the Enron debacle likewise began modestly. In October 2000, an accounting column by Jonathan Weil in the Wall Street Journal noted that Enron traders were signing energy contracts that would deliver income over a standard 10- or 20-year term. But they were booking them as if the total anticipated profit was already safely in the bank. Enron was then one of the hottest stocks on Wall Street, but incredibly the item ran only in the paper’s Texas regional section. A friend sent a copy to Chanos, and the so-called mark-to-market accounting instantly caught his attention, partly because it echoed one of Baldwin-United’s favorite tricks. Chanos spent hours that weekend circling questionable items in Enron’s SEC filings. What mostly interested him were a few simple numbers available to anybody who took the time to look: The company’s ostensibly ingenious managers were earning just seven percent a year on capital that was costing them more than 10 percent. Enron was bleeding itself dry.

Kynikos shorted the company in November, at about $80. Then Chanos exhibited the cabalist behavior that has gotten him labeled as a company-bashing trafficker in innuendo, and worse: He spoke to the press. (“And you know,” Chanos once mused to an interviewer, “there are 10,000 highly paid analysts and investment bankers and PR agents who are out shilling for corporations all day along and no one seems bothered by that.” But a short seller points out a problem with earnings, and “you’re in business with the devil.”) In January 2001, a young reporter named Bethany McLean phoned up scrounging for story ideas, and Chanos told her what he knew about Enron. The resulting article, published that March in Fortune magazine, began gently to pull apart the loose threads of the Enron rat’s nest.

“There was no way to know then that this was a fraud,” Chanos tells his class. “They were just overstating earnings.” But over the next few months, the whole sordid tale unraveled, with all the telltale signs of ethical collapse that are the running theme of this class: The larger-than-life CEO (Jeff Skilling was still posing manfully on magazine covers as late as that February, when Business Week featured him over the tag line “Power Broker”), the weak board of directors, the staff of loyal youngsters, the culture of fear, the conflicts of interest, the willful ignorance, and the willing suspension of disbelief by investors caught up in Enron euphoria.

For Chanos, there was “a great postscript,” he tells the class. “A me-too company called Dynegy” tried to buy Enron as it was spiraling down to bankruptcy. “Someone said, ‘Have you looked at Enron’s books?’ And Dynegy said, ‘That’s the good news. We’ve looked at the books and their accounting is exactly the same as ours.’ I backed up the truck on Dynegy at that point. We made as much on Dynegy as we did on Enron.”

And at that moment, you can begin to see why Wall Street insiders might just hate Chanos, why they might publicly praise him as a hero, and privately wish him to be caught in a very bad, possibly terminal, short squeeze. You can even understand why ordinary investors, standing over the $62 billion black hole that used to be Enron, might sometimes share these misgivings. Revealing the ugly truth (and making lots of money at it) isn’t necessarily a great way to win friends.

But that evening at Pepe’s, where he regularly takes a group of students out for beer and pizza, Chanos is looking ahead, not back. There are other SEC filings in need of careful scrutiny, other companies to short, other forms of corporate entitlement and bad behavior to stoke his sense of outrage. The idea that he might give all this up to go back to Yale for a graduate degree in history is just a fantasy. Right now, he is too busy burning the candle at both ends, and still not getting burned.

END

September 17, 2013

Spiders Make Some Bug Lovers Freak Out

Hairy news from American Entomologist: Even people who spend their lives studying bugs sometimes think spiders are creepy. They should check out my book Spineless Wonders, where I describe therapy for arachnophobia. (Or, to put it another way, where I put my pet tarantula in the hands of a woman who suffers from a lifelong terror of spiders.)

Anyway, here’s the press release from the folks at American Entomologist.

For some entomologists, an apparent paradox exists: Despite choosing a career working with insects, they exhibit negative feelings toward spiders which range from mild disgust to extreme arachnophobia.

An article in the next issue of American Entomologist features the results of a survey involving 41 arachnophobic entomologists who were asked questions about their fear of spiders. Although most entomologists had low scores (indicating mild disgust or mild fear), they still claimed to react differently to spiders than to insects. On the other end of the spectrum, some respondents scored in the clinically arachnophobic range and react to spiders in an almost debilitating manner.

Some of the arachnophobic and arachno-adverse entomologists developed their negative feelings toward spiders in childhood, well before choosing a career in entomology. These feelings were not overcome in adulthood.

“The results of the study show that arachno-adverse entomologists share with arachnophobes in the general public both the development of response and the dislike of many of the behavioral, physical, and aesthetic aspects of spiders,” said Rick Vetter, author of the article. “Paradoxically, I found that despite the great morphological diversity that insects exhibit and despite years of professional exposure to insects, these entomologists do not assimilate spiders into the broad arthropod morphological scheme. However, for the most part these entomologists realized that their feelings could not be rationally explained. Through the mere existence of the study, several of them took solace in learning that they were not alone with their negative spider feelings.”

“Vetter’s study illustrates how the fear of spiders found in some entomologists may have roots in negative events that happened in childhood,” said Gene Kritksy, editor-in-chief of American Entomologist. “This gives us insight on how to lessen this fear in future generations. If parents have a genuine interest in the natural world, including spiders, and they share this positive interest with their children, it could reduce the incidence of arachnophobia in the long run

Whales Have Major Earwax

Majestic, but messy: Big whale, big earwax

Almost everything about blue whales is big, except their pinhole ears. And I know it’s early in the story, but, fair warning, this is where things get kind of gross: Because of those tiny ears, whales don’t have any good way to get rid of their earwax.

The wax—scientists call it cerumen, which sounds so much nicer—just builds up over an animal’s entire lifetime. It forms a stick like a crayon or a candle, but waxy, roughed up, fibrous, with a familiar yellow-brown coloration. “It’s not really appealing,” is the understated way Stephen Trumble, a marine mammal physiologist at Baylor University, puts it.

A few years ago, Trumble and a colleague were chatting about whale earwax while strolling across campus to the coffee shop. Trumble mentioned that biologists sometimes use the lamina, or layers, in these earplugs to age a whale, and a light blinked on in Sascha Usenko’s head. “Earplugs?” he said.

Yes, earplugs. That 10 inches of earwax

Usenko, an environmental chemist, had been analyzing sediment cores to construct a modern history of pollution in various national parks in the American West. Maybe, he wondered aloud, they could try the same thing on a whale’s earplug?

They phoned Michelle Berman at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History to ask if she happened to have a whale’s earplug handy. By good luck—and this is the sort of thing that makes science so wonderful—she replied, “I have one in my freezer. It may take me a while to find it.”

The result … to read the rest of this story, click here.

September 16, 2013

Poem to a Cockroach

Going through my father’s papers, I came across a poem I wrote in about 1980.

It was an homage to the Robert Burns poem “To a Mouse“:

TO A ROACH WHO JOINED ME

FOR DINNER AT AN ELEGANT RESTAURANT

Omnivorous, fat, and brazen bug,

Making this tablecloth your rug,

Stirs there no panic in thy thorax

Of Roach Motel, Bug Getter, Borax?

Of anthropocentric folk who’d like

To stop your crawling with a spike?

Would you restore the social union

Of Man and Nature in communion

Here amidst the silverware?

Roach bold! Roach brave! Roach debonair!

Roach feasting on my butter stain,

My olive pits, my spilled champagne!

On tabletop where all can see

We’re joined in sweet ecology,

Blattidae blessed, ever friend!

But brotherhood’s boring. Crunch! The end.

–Richard Conniff

With apologies, I haven’t figured out how to make this blog display social media links unless the article jumps to a second page. If you liked this item, please share it via the social media of your choice (below, I hope).

September 12, 2013

Snow Leopards, Religion, and Richard Dawkins

In need of divine protection. (Photo: Getty Pictures)

The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has managed lately to be more outrageous than usual in his war to “eradicate the virus of religion.” And, to be fair, religion has given him plenty of fresh material to work with, from the criminal (arranged marriages that amount to religiously-ordained child rape) to the comical (the recent warning by an Egyptian Salafi group that “Tomatoes are Christian”).

For environmentalists, however, it raises the question of whether this relentless assault on religion is really the best way to go about saving the world. No doubt religion has given us an endless supply of holy idiots. The Reverend Jerry Falwell, for instance, attacked environmentalism as an attempt to “use pseudo-science” to destroy the freedom and “economies of the western world.” But Falwell was an outlier even among white evangelical Americans. A 2010 survey by the Pew Center for Religion and Public Policy found that 73 percent of them actually favor stronger environmental regulations.

And now a new study from the other end of the Earth serves as a reminder that religion can sometimes be a powerful force to protect wildlife. … to read the rest of this story at TakePart, click here.

September 11, 2013

The Birth of Antibiotic Resistance

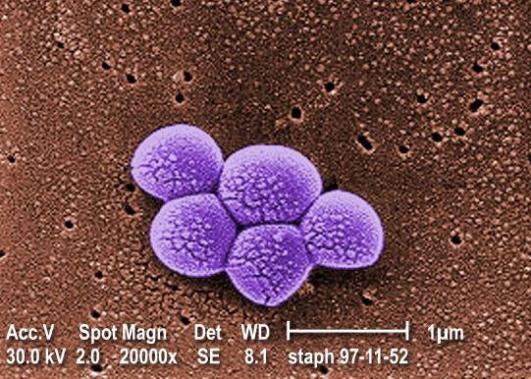

Staphylococcus bacteria get their name from the Greek “staphyle,” meaning bunch of grapes

Rob Dunn at North Carolina State University recently asked me to write a sort of introduction to MRSA. Here’s the result, now live at the Invisible Life project:

One of the most tantalizing moments in medical history took place in February 1941, as a policeman named Albert Alexander struggled to fight off a devastating infection at an infirmary in Oxford, England. A few months earlier, puttering around his rose garden, he’d gotten a minor scratch on his face. It would have been just a scratch, nothing to bother about, except that Staphylococcus aureusbacteria infected the wound and gradually took over his body. Now he was “oozing pus everywhere.”

By good luck, Alexander had landed in the one place in the world where penicillin was being developed, and on February 12, 1941, he became the first human ever treated with the new antibiotic. His condition improved dramatically. But the new drug was so scarce the medical staff had to recycle it from the patient’s urine for reinjection. Then the penicillin ran out before the infection was completely gone. A month later, Alexander was dead.

To those of us who take antibiotics for granted, the idea of dying from a scratch may sound like a bad joke. But it was commonplace before World War II, and every mother lived in fear of losing her child to “blood poisoning.”

It was a hazard because bacteria, and particularly Staphylococcus aureus, are everywhere. About 20 percent of us are normally long-term carriers of some form of staph, as it’s commonly known, and about 60 percent of us carry it intermittently, usually on the skin and in the nostrils. It’s harmless most of the time. But it can also turn deadly in the event of an injury or an illness.

The ability of penicillin to fight off these staph infections was one reason antibiotics seemed like such an astonishing miracle as they became widely available in the aftermath of World War II. Doctors and hospitals were soon prescribing antibiotics for almost any illness, and patients used them with abandon, often failing to complete the full course of a prescription once their symptoms disappeared. The inevitable result was that antibiotics quickly killed off the susceptible bacteria and cleared the field for bacteria that happened to be resistant.

Penicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus proliferated, and in 1959 a drug company responded with the new antibiotic methicillin. It was a backup line of defense, specifically designed to fight the bacteria that penicillin couldn’t touch. But methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (or MRSA) strains appeared just two years later, and soon spread through Western Europe, the United States, and the world.

Though methicillin itself is no longer used in patients, the name MRSA has persisted for staph strains that resist penicillin, oxacillin, ampicillin and other antibiotics. Staphylococcus aureus is by no means the only pathogen to develop antibiotic-resistant strains. Resistant Salmonella and E. coli, for instance, are also common and deadly. But MRSA is the most notorious of these so-called Superbugs.

The majority of MRSA outbreaks have always occurred in hospitals and nursing homes, where antibiotic use in humans is most heavily concentrated. But in the 1980s, community-associated MRSA also began to appear from skin-to-skin contact or use of shared equipment in locker rooms, military barracks, dormitories, and jails. More recently, livestock-associated MRSA has become an issue, because of the meat industry’s heavy reliance on antibiotics. A 2011 study in U.S. supermarkets found MRSA on 25 percent of meat samples, and some of those bacteria were resistant to as many as nine different antibiotics.

The symptoms of MRSA resemble any other staph infection: It begins with swelling and reddening of the skin around a wound, often with small red bumps like pimples. From there it can progress to a deep, painful abscess oozing pus, sometimes followed by infection of the bloodstream, which can then seed the lungs or heart with the infection. Treatment can involve draining the wound, keeping it clean and dry, and, if a test shows that it’s MRSA, administering a new or more potent antibiotic to which the bacteria has not yet become resistant.

Failure to recognize MRSA or take it seriously—for instance, by not completing the full course of a prescription– can be deadly. In 2005, MRSA was a factor in the deaths of 6639 people in the United States, more than half the 11,406 staph-related deaths that year. Since then, health care facilities have made serious efforts to control these infections, reducing incidence dramatically. But incidence of community-related infections has not significantly diminished.

MRSA also remains a serious concern because of the continuing danger that resistance will spread to the relatively few antibiotics on the market that remain effective, especially because there are few promising new antibiotics in the drug company pipeline. We stand on the brink of a “post-antibiotic era,” Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, recently warned. That could mean “an end to modern medicine as we know it. Things as common as strep throat or a child’s scratched knee could once again kill.”

And in Britain in 2010, this once-and-future peril became real for a 73-year-old patient named George Emmerson. He arrived at a hospital in Yorkshire with a rapidly spreading infection. Doctors amputated a finger, and then an arm. But nothing they could do, and none of the antibiotics they administered, stopped the infection from progressing to full-blown sepsis, or blood poisoning.

The cause of death? Like the policeman Albert Alexander almost 70 years earlier—and on the other side of the antibiotic revolution—Emmerson had gotten a trivial scratch while puttering in his rose garden.

September 10, 2013

How to Keep Bats from Causing the Pandemic Next Time

The Indian flying fox (Photo: Gavriel Jecan/Getty Images)

In 2007, in a rural district in northwestern Bangladesh, a man fell ill with fever, followed by fatigue, headache, and coughing. His wife tended to him at home over the next four days, feeding him and wiping froth and saliva from around his mouth. When he began to have trouble breathing, a cousin and a friend rode to the doctor’s office with the patient sandwiched between them on a motorcycle. The next day, they transported him via microbus to the nearest hospital, where he quickly died. All five people in close contact with the patient in his final days soon came down with the disease, known as Nipah virus, and the wife and cousin also died.

It was a small tragedy at the other end of the Earth, and in the grand scheme of things hardly worth noting.

But a new article in the journal Antiviral Research argues that we ought to pay close attention, and not just for philanthropic reasons. Without intervention by the developed world, says Stephen P. Luby, M.D., of Stanford University, a case like this is how the next great plague could leap from wildlife and quickly turn up in our own homes. “Bring out the dead” could become the catch phrase of 2014, or 2040.

Bangladesh is among the poorest and most densely populated nations in the world, says Luby, who worked there for eight years before returning to the United States in 2012. But when he talks with people back home about poor clinical care there, and the absence of basic infection-control measures, “they see it as an issue only … to read the rest of this article, click here.

September 9, 2013

10 Ways Obscure Species Save Our Lives

Look what’s in your medicine cabinet

Why should it matter when scientists discover yet another obscure insect or fungus? Who really cares if we let one such species, or 100,000, go extinct? I get the question from time to time when I am giving a talk. Sometimes I find myself asking it, because the astonishing abundance of life on Earth can at times seem overwhelming. So why does it matter?

Without meaning to make it too personal, my standard response is that the person asking the question would probably be dead, or in great discomfort, were it not for a variety of obscure and often forgotten species. (I try not to add, “And good riddance.”)

About half the drugs we depend on in our daily lives come directly or indirectly from the natural world. Even doctors and drug companies tend to forget this inconvenient truth, maybe because they like to think that they are the ones who cure what ails you. So here are some examples to suggest why Nature deserves a considerable share of the credit: … to read the full article, click here.

Pig Downs 18 Beers, Has Altercation with Cow

The latest report on odd behavior by feral pigs comes from Western Australia, by way of The Guardian:

A rampage by a feral pig that consumed 18 beers has prompted warnings for people at campsites to properly secure their food and alcohol.

The pig struck at the DeGrey River rest area, east of the remote Western Australian town of Port Hedland in the Pilbara, according to the ABC. The animal was seen stealing three six-packs of beer from campers before ransacking rubbish bags for food.

One camper reported seeing the pig guzzling the beer before getting involved in an altercation with a cow.

“In the middle of the night these people camping opposite us heard a noise, so they got their torch out and shone it on the pig and there he was, scrunching away at their cans,” said the visitor, who estimated that the pig had consumed 18 beers.

“Then he went and raided all the rubbish bags. There were some other people camped right on the river and they saw him being chased around their vehicle by a cow.”

The pig was reportedly last seen resting under a tree, possibly nursing a hangover.

Said to have been drinking Foster’s, “Australian for Pig Swill.”

September 8, 2013

Cross a House Cat with a Mantis. Then Run for Your Life.

A praying mantis mated with a cranky housecoat (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

The excellent field biologist and photographer Piotr Naskrecki has filed a report on his latest findings in Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park. Here are the killer paragraphs:

Some of the first animals that I spotted when I resumed my nightly patrols around the lights of the Chitengo camp were huge praying mantids Heterochaeta orientalis, whose head morphology immediately brought to my mind a scrawny, long-eared house cat, and that’s what I decided to call them. The Cat mantids are probably some of the largest in Africa, with the females’ body length approaching 20 cm. Males are about 15 cm long, which still makes for an imposing insect.

Little is known about this species’ biology. I have always found Heterochaeta on tall shrubs and bushes in the woodland savanna, albeit finding them is definitely not easy – despite their size they are some of the most cryptic insects of Gorongosa. It is enough to take your eyes off an individual sitting on a branch for a few seconds to completely lose sense of its whereabouts. When resting on a branch these insects hold their long raptorial legs outstretched to the sides in an uncanny resemblance of two dead twigs coming off a larger branch, very unlike the typical “praying” stance of other mantids, who tend to hold their raptorial legs neatly folded under the pronotum. The pointy protuberances on the Cat mantis’ eyes enhance the illusion that this animal is just a dead, spiky stick. Clearly, their main defense mechanism is to remain undetected by either predator or prey.

But in addition to its superb crypsis the Cat mantis has another trick up its sleeve when it comes to avoiding being eaten. When I first tried to pick up one of the individuals that came to the light, it immediately responded by rearing up its body, opening the front legs to reveal a bright patch on the underside, and fanning its wings to flash a beautiful, contrastingly yellow and black pattern. This color combination signifies danger (think wasps and their stingers) and many potential predators may pause before attacking the Cat mantis, giving it time to fly away. The mantis is bluffing, of course, as other than a very weak pinch it can deliver with its long forelegs it does not have any real weapons or chemical defenses.

Read the rest of the story at his Smaller Majority blog.

Spectacular mimicry: Find Felix the Fabulous Mantis (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)