Richard Conniff's Blog, page 19

July 9, 2016

50 Years After Silent Spring, Herbicides Are Everywhere

In a stand of phramites (Photo: Michigan Technological University )

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

As I write this, I’m looking out at a salt marsh that requires regular spraying with the herbicide glyphosate (sold by Monsanto as Roundup) to keep it from being smothered under dense, eight-foot-high stands of an invasive grass called phragmites. At a nearby lake where I’m a member of a rowing club, the aquatic vegetation is now so dense that it’s being treated with another herbicide called flumioxazin. And along the roads back and forth, even more herbicides get applied, to keep down weedy vegetation along the edges.

More than 50 years after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring first raised the alarm about their uncontrolled use, herbicides are everywhere in North American life. Use of glyphosate alone has increased 15-fold since the introduction of genetically modified Roundup Ready crops in the 1990s. In 2014, that worked out to 250 million pounds of the stuff—eight-tenths of a pound for every acre of U.S. cropland. And it’s not just about agriculture.

A new study in the Journal of Applied Ecology attempts for the first time to add up herbicide use on North American wildlands. “The numbers are much less than those for croplands, but they are astonishing,” said lead author Viktoria Wagner, a plant ecologist at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic. She and her coauthors found reliable information on just 1.2 million acres of wildlands, a fraction of the U.S. government’s 640 million acres of parks, forests, refuges, and rangelands. But in a single year, that sample was sprayed with

a total of 443,000 pounds of herbicides—equal, said Wagner, to “the weight of 13 school buses.”

The new study isn’t necessarily aimed at stopping herbicide use. Land managers have an obligation to take action against invasive species that would otherwise devastate native ecosystems, said Cara R. Nelson, a coauthor and a restoration ecologist at the University of Montana.

Cheat grass in the American West

For instance, cheat grass, an Old World species that has run wild across the American West, destroys the food value of rangelands for wildlife, particularly dwindling populations of greater sage grouse. It also causes big, hot wildfires that kill off sagebrush, depriving the sage grouse of shelter. Fast-growing kudzu, “the vine that ate the South,” smothers native plant species and pulls down trees. Water hyacinth chokes ponds and lakes everywhere. Ending herbicide use would just speed up the pace of destruction.

What worries the team of coauthors, including researchers from Mexico, the United States, and Canada, is the almost complete lack of record keeping in those three countries detailing where herbicides are being used on wildlands, in what quantities, at what cost—and to what effect. So there’s no way to tell if herbicides are doing the job—or if they are incidentally damaging native species. “The point of our paper,” said Nelson, “is that we’re using a very large amount of herbicide” on wildlands in an attempt to restore native species, “but we know almost nothing about effects on native plants”—or, for that matter, on pollinators and other native wildlife.

The experience in agriculture suggests this could pose a significant risk: Intensive use of glyphosate on farms has, for instance, incidentally destroyed tens of millions of acres of native milkweed. To farmers, it’s just another weed, as the name suggests. But it’s an essential food source for monarch caterpillars, and loss of that habitat appears to be a major factor in the dramatic decline of the butterfly species.

Glyphosate is also the herbicide of choice on wildlands, a surprise, said Wagner, because it’s “a nonselective herbicide that harms grasses and herbs alike and thus has a higher potential to negatively affect desired native plants.” When she and Nelson made a separate study of two other commonly used herbicides, they found that both inhibited germination of native and invasive plant seeds alike.

“That’s important,” said Nelson, because spraying herbicides to remove invasive species “opens up ecological niches” for other plants—and restoration ecologists generally aim to fill those niches by planting seeds of native species. The United States spends billions of dollars on such ecological restorations every year. But right now, we are spending that money blind.

Both the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management, the two largest land managers in the country, are working to change that. The BLM last year launched its National Invasive Species Information Management System, an attempt to standardize collection of data on invasive species treatments.

But my guess is that Rachel Carson would say this is too little, too late, and that we need to be think much harder about what that 13-school-bus load of herbicides—multiplied across hundreds of millions of acres of North American wildlands—is really doing to our native species.

New Zealand wetland sprayed with herbicide to remove unwanted willows

July 3, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Baby Elephant Walk

This song was an unlikely pop hit from the early 1960s, by Henry Mancini. He wrote it for the 1962 Howard Hawks film “Hatari!” about the adventurous characters who made a living then catching elephants, rhinos, and other African wildlife to stock zoos. These days we would call that line of work “dubious” or even “criminal.” But those were different times.

Hawks had filmed an impromptu scene of the Martinelli character leading three baby elephants to a watering hole. But he didn’t know what to do with it. Before giving up on it, Hawks came to Mancini and said, “Take a look and let me know if you have any ideas.”

Mancini later wrote:

“So I looked at the scene several times and still thought it was wonderful. As the little elephants went down to the water, there was a shot of them from behind. Their little backsides were

definitely moving in rhythm with something. I kept thinking about it; it reminded me of something. I thought Yeah, they’re walking eight to the bar, and that brought something to mind, an old Will Bradley boogie-woogie number called “Down the Road a Piece” … Those little elephants were definitely walking boogie-woogie, eight to the bar. I wrote “Baby Elephant Walk” as a result.

Mancini sat down at a piano to audition the song for Hawks, who kept the scene in the movie.

Two weird afterthoughts: The pop version that made the Billboard Top 100 was by Lawrence Welk and his Champagne Music Makers. Welk was the impresario of a relentlessly wholesome variety show then, and stupefyingly dull. I feel bad saying that, though, as he was my mom’s favorite television personality.

An episode of “The Simpsons” also featured this song, though the backside moving eight to the bar belonged to Homer Simpson:

July 1, 2016

The Notorious Racist Who Inspired America’s National Parks

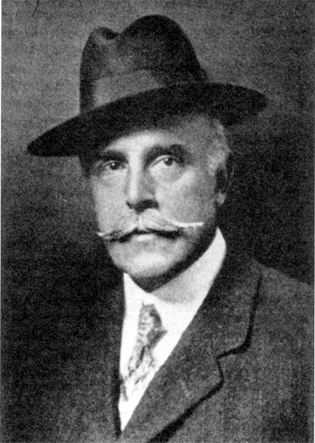

Madison Grant

by Richard Conniff/Mother Jones

I used to tune out when my father would go on about eminent domain: how his immigrant grandparents had built up a modest homestead with two houses, three grown children, and a flock of chickens on the banks of the Bronx River. And then, around 1913, how the government had seized the property to make way for the Bronx River Parkway. That the episode still rankled after almost a century just seemed like a manifestation of my father’s cranky late-life conservatism.

That was before I found out about Madison Grant.

It’s a name you should be hearing a lot this year because of the centennial of the National Park Service—in many ways a product of Grant’s pioneering work as the greatest conservationist who ever lived, according to one early Park Service director, and a creator of “the park concept,” in the words of another. But you probably won’t hear Grant’s name so much as whispered, because his peculiar line of thinking also helped lay the groundwork for the death camps of Nazi Germany.

Born in 1865, Grant enjoyed a blue-blood Manhattan childhood thanks to his mother’s family wealth and his father’s reputation as a doctor and Civil War hero. At 16, he went to Germany for four years of private tutoring before coming back for Yale and then Columbia Law School.

Grant was a handsome, urbane figure with a thick mustache and steady, deep-set eyes and a reputation as a ladies’ man. He set up a Manhattan law office but rarely practiced. Nor did he ever hold public office, despite his keen political interests. Big-game hunting was his real passion, according to the definitive 2008 biography Defending the Master Race, by historian Jonathan Spiro, and he recognized early on that reckless overhunting was driving many species to extinction. Wealth, social connections, and his sharp mind soon earned him membership among such early hunter-conservationists as Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, and George Bird Grinnell in a spectacularly influential little group called the Boone and Crockett Club.

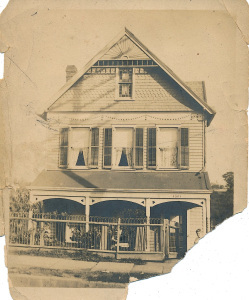

My great-grandparents’ home on the Bronx River

By 1895, Grant was overseeing construction of the Bronx Zoo, dedicated to the preservation of North American species, and had founded its parent organization. (The Wildlife Conservation Society, as it’s now known, likewise never mentions Grant’s name.) Among his many other initiatives, Grant helped launch the campaign to stop the last of California’s magnificent redwoods from being logged, worked to save the bison (restocking the Plains with bison from his zoo), and pushed for the creation of the Denali, Olympic, Everglades, and Glacier national parks.

This legacy might sound like fodder for Park Service accolades and PBS documentaries, except for one problem: After 1908, Grant began extending his efforts on behalf of North America’s native species to what he considered its “native American” people—not Indian tribes but northern Europeans, preferably “of Colonial descent.” In 1916, he published The Passing of the Great Race to call attention to the plight of the “Nordics,” a word he helped popularize. “Unlimited immigration” and intermarriage, he warned, were “sweeping the nation toward a racial abyss.”

The book was a 476-page pseudoscientific compendium of stereotypes. Black men were “a valuable element in the community” so long as they remained “willing followers who ask only to obey and to further the ideals and wishes of the master race.” The Irish tended to be intellectually “inferior,” and “the Slovak, the Italian, the Syrian and the Jew” were “social discards.” Having seen New York City’s Jewish population surge from 80,000 to more than a million in just 30 years, Grant was especially enraged at “being literally driven off the streets…by the swarms of Polish Jews.”

Grant’s book ought to have been a national scandal. But eugenics, the idea that human stock could be improved much like livestock, was then becoming almost an establishment religion. So The Passing of the Great Race was published by Scribner’s and edited by Maxwell Perkins (who later edited F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway). The president of the American Museum of Natural History wrote the preface, and former President Theodore Roosevelt provided a blurb (“a capital book“).

My great-grandfather Bartolomeo Badaracco

Grant parlayed his rising influence as a eugenicist into a series of punitive measures aimed at “inferior races and classes.” The Bronx River Parkway, for instance, was originally about cleaning up a polluted river and adding a roadway through newly picturesque landscapes. But Grant’s commission carefully planned the project to take out “the wrong sort of development”—”Italian shacks” like my great-grandfather’s, and neighborhoods populated by “Negroes.”

Others lost far more than their homes under Grant’s influence. Many states pursued his recommendation to apply mandatory sterilization “to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased and the insane and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings.” Grant was also key to the passage of a 1924 law restricting immigration by groups he deemed undesirable, including Asians and Arabs.

When the Nazis established their compulsory sterilization program in 1933, they said they were following “the American pathfinders Madison Grant” and a Grant disciple, Lothrop Stoddard. Hitler once supposedly wrote to Grant to say his book had become “my Bible.” Grant died in 1937, too soon to see his theories turned into mass murder. But among those he inspired was Karl Brandt, the physician behind the Nazi program of forced euthanasia. At Nuremberg, Brandt’s lawyers presented The Passing of the Great Race as evidence that the Nazis had merely done what an American scholar had advocated.

Conservationists would understandably rather forget all this. But it’s worth remembering because the movement has always struggled with elitist and exclusionary elements in its ranks. Among other things, this country invented and exported worldwide the model of uninhabited national parks—together with its ugly corollary, forced removals of indigenous populations. It’s also worth remembering Grant’s history because minority groups remain vastly under-represented—just 22 percent of all visitors at last count—in our national parks, and even more so in the leadership of environmental agencies and nonprofits. To change that, the conservation movement needs to acknowledge that the ghost of Madison Grant still haunts the natural wonders he helped protect.

Clearcutting Europe’s Last Virgin Forests (& Calling it “Green”)

One of the European brown bears that roam Romania’s Carpathian Mountains. (Photo: Jamie Lamb/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

We tend to imagine that illegal logging mostly targets tropical forests in the Amazon, Southeast Asia, and other remote and poorly regulated regions, not in our own backyards. For people who pay attention to such things, there’s comfort in the idea that buying only Forest Stewardship Council–certified lumber keeps us free of complicity in that sort of criminal destruction of woodland habitat.

The latest undercover work by the Environmental Investigation Agency focuses on Europe and undermines both those assumptions. It’s a significant embarrassment for the FSC, which until last week was putting its seal of sustainability on timber said to be illegally harvested from Europe’s last

A clearcut forest in Romania. (Photo: Environmental Investigation Agency)

surviving virgin forests, in the Carpathian Mountains, and from national parks and other protected areas in Romania. Those habitats were for many years the only refuge in Europe for bears, wolves, lynx, and other species—and they have played a major part in the recent continent-wide rewilding of Europe.

The FSC’s decision to suspend its certification of the Austrian logging company Holzindustrie Schweighofer comes eight months after the U.K.-based EIA published its initial report, Stealing the Last Forest, alleging extensive ties between the company and illegal logging and corruption in Romania. It’s also more than a year after the release of an EIA video showing a company executive offering to accept illegal timber from an undercover investigator posing as an American investor in Romanian forests.

FSC announced that it is also suspending Quality Austria, the auditing body that was supposed to have done due diligence on Schweighofer’s operations. Both suspensions are temporary,

pending the outcome of an investigation to be completed in September. Schweighofer is also under criminal investigation in Romania, after an investigation discovered more than 100,000 cubic meters of illegal timber in just one of its three Romanian mills. The World Wildlife Fund Austria has also filed a complaint with Austria’s Federal Forest Office alleging violations of European Union timber regulations.

Corey Brinkema, president of the Forest Stewardship Council U.S., said FSC “relies on multiple levels of checks and balances to ensure the integrity of our system.” He praised WWF and EIA for “playing an invaluable watchdog role” and also said, “The investigation and suspension of the certification indicate that the FSC system is working. We take allegations of illegal logging and other egregious practices very seriously and invest significant resources into investigating such claims. Where evidence supports it, we have a history of taking strong action to maintain the integrity of the FSC system.”

Schweighofer, a 400-year-old woodworking company, enjoyed a reputation for sustainability in its Austrian forests. But in 2002, it sold off its operations there and began heavily investing in Romania, a country with widespread political corruption. It made a point of touting the FSC certification for its own 30,000 or so acres of forest in Romania, according to the EIA report. But that forest supplied just 2 percent of its Romanian production in 2014, with the rest coming from more than 1,000 individual suppliers.

During negotiations with Schweighofer, EIA Executive Director Alexander von Bismarck posed as an American investor who had purchased a Romanian forest. His permits allowed him to harvest the timber over seven years, he said, but he wanted to cash out in just three. Schweighofer executives repeatedly agreed to accept illegal timber, according to EIA, and while its contract stipulated a small penalty, they told von Bismarck they would pay a bonus of $10 per cubic meter for everything beyond the contracted amount.

In the aftermath of the original EIA study, Holzindustrie Schweighofer chief executive Gerald Schweighofer acknowledged that “Romania’s forest suffers undeniably from illegal logging” but called the charges against the company “unjust, misleading and unsubstantiated.” After last week’s suspension by the FSC, a lower-ranking company executive offered to work to uncover “potential risks with regard to the lawful sourcing of timber” and predicted that “after a successful audit, the FSC certificate can again be used in full.”

Holindustrie Schweighofer’s main factory in Sebes, Romania. (Photo: Environmental Investigation Agency)C

EIA reports, however, that as Schweighofer’s purchases in Romania have come under scrutiny, the company has begun to shift its sourcing to neighboring Ukraine, which ranks 130 out of 167 nations on the Transparency International corruption index and also has a reputation for illegal logging. In a new report aimed at buyers in Japan, EIA warns that “Japanese buyers need to be extra vigilant in questioning the validity of the company’s documents of origin,” in part because of recent media reports about “illegal logging of irradiated pine logs within the forbidden zone surrounding Chernobyl,” site of the world’s largest nuclear disaster.

The EIA campaign against Schweighofer comes in the wake of the agency’s successful investigation of U.S. retailer Lumber Liquidators. Early this year, that company paid $13.1 million, the largest fine in the history of the century-old Lacey Act, for illegally purchasing timber from another temperate-zone forest, the only remaining habitat of the Siberian tiger in the Russian Far East. Lumber Liquidators’ stock price plummeted by 90 percent because of the simultaneous report that it risked poisoning customers through high doses of formaldehyde in its products.

The immediate take-home from the Schweighofer investigation is that the European Union needs to close a major loophole in its rules against sale of illegal timber products. Those rules aim to block imports into the EU but do nothing to stop the sale of illegal timber from member states such as Romania and Ukraine. The Lacey Act, by contrast, bans trafficking in illegal wood products even across state borders. EIA has also been lobbying for Japan to establish rules against illegal logging imports. That country has no equivalent of the EU forest regulations or the Lacey Act but has been a major buyer of Schweighofer wood.

The other big message that major retail buyers should be getting—remind your favorite home supply or furniture store—is that they can’t just look the other way anymore and hope that suppliers are doing the right thing. Though no company executives have gone to jail yet, blissful ignorance is becoming a good way to end up in serious trouble. And for the rest of us? Until the FSC tightens its certification process, we are still back where we started, at “Buyer beware.”

Angry Tweets Won’t Help African Lions

(Photo: Craig Taylor/Panthera)

by Richard Conniff/The New York Times

THE killing of Zimbabwe’s celebrated Cecil the Lion by a Minnesota dentist, on July 1 of last year unleashed a storm of moral fulmination against trophy hunting. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals issued an official statement calling for the hunter, Walter J. Palmer, to be hanged, and an odd bedfellow, Newt Gingrich, tweeted that Dr. Palmer and the entire team involved in the killing of Cecil should go to jail. The television personality Sharon Osbourne thought merely losing “his home, his practice and his money” would do, adding, “He has already lost his soul.”

More than one million people signed a petition demanding “justice for Cecil,” and three major American airlines announced that they would no longer transport hunting trophies. A few months later, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service listed lions from West and Central Africa and also India as endangered, shutting down the major markets for trophies from that region. Australia, France and the Netherlands banned lion trophy imports outright.

Unfortunately, the furor did almost nothing to slow the catastrophic decline in lion populations, down 43 percent over the past two decades. That’s because trophy hunting was never really the main problem. Lions are disappearing in Africa for a reason far more complicated and less susceptible to either moral grandstanding or easy solutions: Impoverished Africans are eating the lions’ prey and killing the lions themselves — at a rate estimated at five to 10 times the take from trophy hunting.

In West and Central Africa in particular, the killing now takes place almost entirely within national parks and other ostensibly protected areas. Poachers and bushmeat hunters …

June 30, 2016

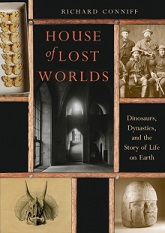

House of Lost Worlds: “Loved This Book! It’s All There”

Fire set to discourage an 1870 Peabody Museum fossil hunt in the American West.

It has been amazingly difficult to get the mainstream press to review House of Lost Worlds, unlike anything I have experienced with all my previous books.

It has been amazingly difficult to get the mainstream press to review House of Lost Worlds, unlike anything I have experienced with all my previous books.

Editors seem to make a snap judgement that it’s just the story of one museum, with no significance outside New Haven. They do not know what they are missing.

Here’s how historian William Hosley reacted in a review on Facebook today:

Finished Richard Conniff‘s #HouseofLostWorld – a 150th anniversary story about Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Spellbound. Riveting. Best book on any aspect of museums I’ve ever read – and the history of museums is one of my favorite topics. Convinces me that Peabody is CT’s most important museum. If I was teaching a survey course on American History this would be on the syllabus. What a bold stroke to tell the story of an institution as

Anchiornis huxley, in full color.

a series of biographical profiles of pathbreakers in science and natural history. As institutional history (if that’s what it is) its unheard of in its combination of reverence and IRREVERANCE. If I’d read this book when I was young, I might have gone into the sciences. Seriously – do yourself a favor – get this book and dig in. Conniff begins and ends his mercifully-short, lavishly-illustrated chapters with openings and closings you will not believe – and filling is all good too. Loved this book! It’s all there – from the discovery of dinosaurs to the defense of evolution to Indiana Jones and the origins of conservation and ecology. Makes me proud to live in a place that spawns such genius. Yale University should be so so proud of this gem of a museum. David Heiser, Richard Kissel Melanie Gordon Brigockas Michael Morand – please share and thanks again for our awesome behind the scene tour and program recently!

https://www.amazon.com/House-Lost-Worlds-Dino…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

And thank you, Mr. Hosley.

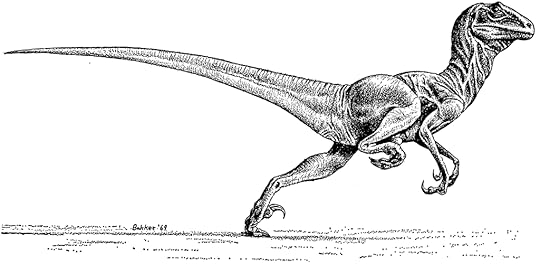

The Peabody’s Deinonychus (before they knew about the feathers)

June 26, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Muskrat Love

Yep, this is a song about two muskrats having sex. And even if most of us have never heard the actual event, muskrat vocalizations consist of squeaks and squeals, which sounds about right. The principals in this song are Muskrat Susie and Muskrat Sam, and there is apparently talk of marriage before they do the thing. Texas singer Willis Alan Ramsey wrote and recorded the song in 1972, under the title “Muskrat Candlelight,” and this is his version.

I find just looking at the Captain and Tenille cover from 1976 hideously painful but if you insist, have at it:

June 24, 2016

The Prince and the Paleontologist

Wieland with a fossil turtle known affectionately as “Stumpy”

This morning a lovely email came in about my book House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life On Earth. It’s from a writer and radio commentator named Jill Hunting:

“I have just finished reading your book and wanted to offer congratulations on a marvelous achievement … The writing throughout is beautiful and consistent, and I am in awe, frankly, of the soft landings at the end of your chapters.”

She added: “My favorite page is 154.” So naturally I wondered what the hell was on p. 154, and found as a short anecdote about an eccentric paleontologist–is that redundant?–named George R. Wieland.

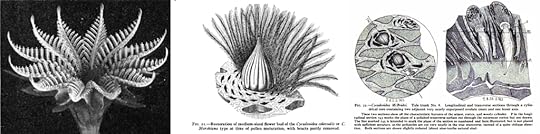

In the late 1890s, Wieland began working in South Dakota on a forest of fossilized plants called cycadeoids, also known as cycads for their resemblance to a variety of modern plant with a woody stem and palm-like crown. He soon became hooked on cycads. They had obvious visual interest, with their intriguing shapes, often resembling a beekeeper’s traditional basket beehive, and with a surface pattern of orderly pockmarks, from old leaf attachment points.

Wieland reconstructions of cycadeoid flowers and cones.

Local ranch families who collected the fossilized trunks as curios described them, Wieland wrote, as “beehives,” “wasps’ nests,” “corals,” “mushrooms,” and even “beefmaws,” for their resemblance to a bovine reticulum, the first digestive organ of a ruminant’s alimentary tract. On repeated trips back to the site in South Dakota, Wieland retrieved more than 700 cycad specimens, giving the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History the most extensive collection of these fossil plants in the world (and also earning Wieland a reputation in South Dakota as a plunderer). He also developed various methods of drilling and slicing cycads to study their interior anatomy. But let’s go to p. 154:

Over the years, Wieland became obsessed with his subject, even by the standards of museum curators. He could talk about nothing else, and he seems to have talked endlessly, to the point that it became necessary to

ban him from the preparators’ workrooms. In time, he “was practically kicked out of the museum,” according to an oral history, and had to move “his big old saw set up” to the basement of another building on campus. (“When did he begin to sort of go to pieces? Was that before he retired or after?” one former director of the museum wondered in that oral history, and another former director replied, “Maybe it was when he was born. He was a queer one all his life.”)

In June 1926, Yale was preparing for a visit by Sweden’s crown prince Gustaf Adolf VI, who was receiving an honorary degree. University authorities were “agog over the rare opportunity of entertaining royalty,” a Yale alumnus later recounted in a letter to Time magazine. They prepared to mark the event “with the utmost dignity and propriety,” beginning with “an exclusive little luncheon for only the mightiest figures of academic and of local society.” Then the prince arrived and asked for the one thing no one had ever thought to include: George R. Wieland. “Consternation smote the party and a frantic search for Yale’s forgotten man ensued.”

Wieland, who had no phone, was eventually tracked down at his suburban home, hustled back to New Haven and seated beside the prince. “The conversation presented pretty tough going for the local elite and even for the President and Fellows, for it dealt almost exclusively with fossil cycads,” the writer continued. Everyone was praying for the luncheon to end so they could escape stupefying talk of cycads and otherwise engage their honored guest’s attention.

Instead, the prince suggested a visit to Wieland’s workroom. Someone raced ahead in a desperate bid to bring order “out of the monumental chaos and dustiness” there, to no avail. The party of dignitaries found it “a little difficult to appear dignified and interested and at the same time keep their morning coats and striped trousers out of the inch-thick dust while the Prince and Wieland continued their ardent and interminable conversation.”

The prince, it was evident, was a serious paleobotanist, and George R. Wieland had found his perfect audience.

There much more worth checking out in the book, which you can buy here: “House of Lost Worlds”

June 20, 2016

The New Kid on the Block Has Nasty Habits: Invasive Species

Tree Slayer: Asian Longhorned Beetle

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

In the summer of 1996, a Brooklyn developer named Ingram S. Carner noticed that the sugar maples in his neighborhood were struggling and also had unusual holes in their trunks. Carner suspected a vandal armed with a portable drill. He staked out the scene, and after a long wait, something far more dangerous crawled out of one of the holes: a beetle.

“He could have looked at it and paid no attention. He could have stepped on it,” said Richard Hoebeke, an entomologist then working at Cornell University. Instead, the specimen soon found its way to Hoebeke’s desk. “It was nothing I had ever seen before, clearly nonnative.” But within a few hours, he was able to pronounce it an Asian long-horned beetle (or rather, Anoplophora glabripennis), the first to be identified in this country.

If it had gone undetected, a study by the U.S. Forest Service later estimated, the beetle could have killed a third of the trees in cities nationwide, at a loss of up to $669 billion. Instead, the discovery launched a major campaign to locate and contain the invasion at a handful of sites around the United States.

Here is the scary thing:

Invasions like that happen all the time. Roughly 50,000 alien species are established in the U.S., and a 2005 study put the economic and environmental costs at $120 billion a year. Most of that is in damage to agricultural crops and forests. But take a look at the plants and animals on the threatened and endangered species lists, for instance, and invasive species are the main reason about 42 percent of them are in trouble.

Scarier still, globalization of trade and increasing international travel make the danger worse each year. A new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has added up the factors determining whether a species invades another country and becomes established well enough to do serious damage. It found that China and the United States are the countries at greatest risk, in purely economic terms. That’s mainly because those two countries lead the world in international trade. For the same reason, they are also the leading sources of species likely to become invasive elsewhere.

But this all sounds a little abstract. So let’s look at a recent case study. Sometime in the 1980s, a trivial-seeming species called the spiny water flea invaded the Great Lakes and spread from there. Lake Mendota in Madison, Wisconsin, in particular, seems to have been spiny water flea heaven. Since spiny water fleas are enthusiastic predators, they demolished the population of a native species called Daphnia pulicaria. The Daphnia in turn are enthusiastic grazers, and when they disappeared, weedy vegetation boomed, turning formerly clear water murky. This is what scientists call a trophic cascade. Nonscientists just say, “What the hell happened to my lake?”

The good news, Madison, is that you can get your lake back. But since you’re now stuck with the spiny water fleas, the only practical way to do it is to get rid of the pollution that’s feeding all that vegetation. To be precise, it’s going to require a 71 percent reduction in the amount of phosphorous entering the lake from farms, lawns, and household plumbing, at a cost somewhere between $87 million to $163 million. (After that we can talk about Lake Monona just next door.) Multiply the mess in Madison by 10,000 or 100,000 other lakes, plus countless rivers, fields, and forests, and you may begin to see why it’s a big deal when alien species slip into the country.

What can we do to minimize the risk? The first step is to stop being stupid: We live in a time of mindless demagoguery about the dangers of “big government,” combined with an irrational drive to cut all federal funding across the board (except for the military), regardless of the demonstrable benefits. So who is going to do proper inspections at ports and airports, if not U.S. Customs and Border Protection? Who will make difficult taxonomic identifications fast enough to block invasive species at the border, other than the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service? This is one of the many reasons we have a federal government.

So call it “defense funding,” if you must. Or call it “standing up to China” when federal agents turn a ship around and order it back to its point of origin because it’s infested with Asian gypsy moths. Just accept that our taxes sometimes work to our joint benefit, and get on the phone to tell your representatives in Congress to fund these watchdogs at our borders.

Since we’re also big on talking about “individual responsibility” these days, it’s worth noting that individuals can make a difference, too, by paying attention to the rules on what you can legally bring back from travel abroad. When the customs agent confiscates the specialty meat you were trying to sneak into the country, that’s not government tyranny in action. It’s not even government tyranny when the law prevents you from carrying firewood across state lines. Instead these are measures to prevent invasive species and pathogens from getting into the country in the first place and from spreading once they get here.

One last point about the new study in PNAS: The authors don’t make a big deal of it, but there’s a poignant dark side to the international trade–invasive species equation: When you look at the potential damage to quality of life—and not just at dollars and cents—the countries that benefit least from international trade seem nonetheless to suffer the worst risks. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa in particular tend to lack diverse economies and depend largely on agriculture, leaving them highly vulnerable to invasion by agricultural pests and pathogens. For us, the risk is about economic loss. For them, it’s about not being able to feed their families. It’s a lot like what’s happening with the consequences of climate change: those least to blame nonetheless face the biggest potential hit.

That’s a hidden cost researchers and political analysts should be taking into account when they talk about the value of international trade.

For India’s Captive Leopards: Life Behind Bars

Leopard detention camp, in Mumbai (Photo: Richard Conniff)

by Richard Conniff/Yale Environment 360

When an escaped leopard tackled a man at poolside on a school campus in the southern Indian city of Bangalore early this year, the video went viral. The victim was one of the wildlife managers trying to recapture the animal. His colleagues finally managed to tranquilize it late that night and return it to a nearby zoo that was serving as a rescue center for a population of 16 wild-caught leopards. A week later, the leopard squeezed between the bars of another cage and escaped again, this time for good.

All the news and social media attention focused on the attack — and none on the underlying dynamic. But that dynamic affects much of India. Even as leopards have vanished in recent decades from vast swaths of Africa and Asia, the leopard population appears to be increasing in this nation of 1.2 billion people. The leopards are adept at living unnoticed even amid astonishingly high human population densities. But conflicts inevitably occur. Enraged farmers sometimes kill the leopards. But trapping is the more common response, and religious and animal rights objections have made euthanasia for unwanted animals unthinkable.

Thus anywhere from 100 to several hundred wild-caught leopards nationwide have ended up being trapped and locked away for life, in facilities that often cannot provide proper security, space, veterinary care, or feeding.

In the Bangalore incident, the attack victim, leopard biologist Sanjay Gubbi, managed to fight off the leopard and stagger away with claw wounds on his right arm and torso, requiring 55 stitches. Two others working on the bungled re-capture effort also suffered minor injuries. The leopard, an eight-year-old male, had escaped in the first place (and later re-escaped), according to a manager at Bannerghatta Biological Park, because it was being kept there in cages designed for tigers or lions, not leopards.

For lack of space, other rescue centers and zoos have kept leopards for months at a time in the box traps that were used to catch them. Until recently, one national park even put leopards on display …

To read the full story, click here.