Richard Conniff's Blog, page 18

July 31, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Ants Marching

An ant from Madagascar named Eutetramorium mocquerysi (SEM photo: Molly Gibson)

Yikes, it’s been more than 20 years since the David Matthews Band released its anthem (that may be a pun), “Ants Marching,” in December 1995. The gist of it was that we sometimes allow our lives to lapse into a state of tedium and repetition, like ants: “All the little ants are marching, red and black antennae waving, they all do it the same, they all do it the same way.”

I think ants are actually way more interesting than DMB lets on. In fact, I once traveled to Madagascar to jump a freight train and go bushwhacking for ants with the California Academy of Sciences entomologist Brian Fisher. You can read about that episode in my book Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals.

But, oh, shit, I just realized that trip happened ten years ago now.

The week ends, the week begins.

Animal Museum Monday: Ants Marching

An ant from Madagascar named Eutetramorium mocquerysi (SEM photo: Molly Gibson)

Yikes, it’s been more than 20 years since the David Matthews Band released its anthem (that may be a pun), “Ants Marching,” in December 1995. The gist of it was that we sometimes allow our lives to lapse into a state of tedium and repetition, like ants: “All the little ants are marching, red and black antennae waving, they all do it the same, they all do it the same way.”

I think ants are actually way more interesting than DMB lets on. In fact, I once traveled to Madagascar to jump a freight train and go bushwhacking for ants with the California Academy of Sciences entomologist Brian Fisher. You can read about that episode in my book Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals.

But, oh, shit, I just realized that trip happened ten years ago now.

The week ends, the week begins.

July 29, 2016

Natural History Museums Go Digital & Science Benefits

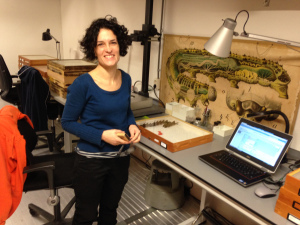

(Photo: Richard Conniff)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Until the 1990s, at many prominent natural history museums, the staff would ritually log new specimens into their collections much as they did it 200 years ago, using a pen dipped in India ink to inscribe the details into a leather-bound volume.

It was Dickensian, and reliance on that sort of record keeping at museums everywhere was a major impediment to knowing where different specimens were located. That made it difficult, at best, for scientists to put those specimens to work making sense of our world. But this old roadblock is rapidly disappearing, because of the digitization of specimens at museums around the world. At the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands, recently, entomologist Eulàlia Gassó Miracle showed me how it works.

Before digitization. (Photo: Richard Conniff)

First, we took a look at what it’s like for scientists to begin to make sense of a collection that hasn’t been properly sorted—specifically tens of thousands of swallowtail butterflies collected by a Dutch physician, JMA van Groenendael, working in Java in the 1930s. A drawer-size sorting box held a dusty jumble of 20 or so of these specimens at a time, each contained in a wax paper envelope or a page of a colonial newspaper neatly folded into a triangle. The job was to open each specimen, photograph it, identify the species, record the information on a database, and place it in a properly labeled archival envelope for permanent storage. Now and then a rare specimen would be set aside to be pinned, or mounted, as if alive, in a collection drawer.

Van Groenendael and his wife had survived in a Japanese internment camp

during World War II, said Gassó, and his collection then came back to him only through the help of a Javanese colleague. But most of the villages (or kampongs) where he collected no longer exist, and most of the old forests are now palm oil plantations and rice paddies.

(Photo: Richard Conniff)

Next Gassó led me to a collection room downstairs to show me how much easier it gets once you have digitized a collection. She picked up a handheld scanner, like the ones used at checkout counters, and with a flash of red light, read the label on the front of the drawer and displayed its contents on a nearby computer screen: males and females of Southeast Asia’s common birdwing butterfly, Troides helena.

In the past, a researcher wanting to know more about a particular specimen would have had to pull up the pin and slide off as many as five or six fragile paper labels, on which the collector had written detailed information in tiny chicken scratch. Instead, with another flash of her bar code scanner, Gassó displayed all the labels instantly on a computer screen.

Moreover, these details—increasingly including genetic data for many species— are now visible not just in Leiden but to anyone interested, anywhere in the world, free and on demand through websites like iDigBio.com and gbif.com (the Global Biodiversity Information Facility) or the Naturalis center’s own Bioportal. That universal access matters because most of the world’s natural history museums, and most of the preserved specimens, are in industrialized nations. But most of the undescribed species are in a handful of nations with emerging economies such as Brazil, South Africa, India, and the Philippines. Digitizing collections gives scientists in those countries easy access to their own natural history. It makes natural history collections less colonial and more global and democratic.

Moreover, these details—increasingly including genetic data for many species— are now visible not just in Leiden but to anyone interested, anywhere in the world, free and on demand through websites like iDigBio.com and gbif.com (the Global Biodiversity Information Facility) or the Naturalis center’s own Bioportal. That universal access matters because most of the world’s natural history museums, and most of the preserved specimens, are in industrialized nations. But most of the undescribed species are in a handful of nations with emerging economies such as Brazil, South Africa, India, and the Philippines. Digitizing collections gives scientists in those countries easy access to their own natural history. It makes natural history collections less colonial and more global and democratic.

It also matters because digitized collections make it much easier for scientists to locate specimens anywhere in the world and put them to work in their research. Thus digitized specimen collections are helping to answer questions about the natural range of different species, and to predict whether they will be able to adapt to climate change. They are also helping to document the spread of invasive species and patterns of extinction.

Digitized specimen collections allow scientists to answer novel questions about how the world works. For instance, many butterflies have eyespots on the upper surface of their wings, and the long-standing theory is that they serve to scare off potential predators. But Antónia Monteiro, a biologist at Yale-NUS College in Singapore, wanted to know how those eyespots got there in the first place. Digitization enabled her to examine a broad sampling of nymphalid butterflies. Sophisticated bioinformatics software identified specimens with eyespots and coded the location and size of the spots.

Monteiro then overlaid that data onto the evolutionary history of nymphalid butterflies and traced the origin of eyespots back 90 million years. Weirdly, she found that the first eyespots were small and in the wrong place, hidden on the underside of the hindwing. It took millions of years of evolution—and many, many butterflies being eaten by predators—for the eyespots to enlarge and migrate to a more useful position on the upper side of the forewings.

At this stage, only about 10 percent of specimens in collections worldwide are available through digitization. It will require a substantial commitment of time and money to complete the job. But as this trend strengthens, it makes natural history collections far more relevant to the pressing scientific questions of our day. As Monteiro’s research demonstrates, it may also help the museums that maintain these collections regain some of the sense of wonder embodied in a question like “Where did the butterfly get its spots?”

END

Check out this short video by Naturalis on the digitizing process:

July 25, 2016

Bikini on Baker Day

By Richard Conniff

Carl O. Dunbar, director of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History in the 1940s, wasn’t the sort of person you would immediately imagine as an eyewitness to one of the epochal events of the twentieth century. He was a paleontologist, specializing in little known marine invertebrates called fusilines, which vanished from the Earth, along with most other life forms, in the Great Permian Extinction of 252 million years ago.

So I was surprised during the research for my book House of Lost Worlds, about the Peabody’s colorful history, when a researcher at the University of Kansas sent me the painstakingly photographed pages of a journal kept by Dunbar 70 years ago this summer, during his time as part of a scientific delegation invited to witness Operation Crossroads, the first atom bomb tests of the post-World War II era, on Bikini Atoll in the mid-Pacific. (Dunbar, a Kansas native, had left the journal and associated papers to the university archives, where they were largely forgotten.)

James Dwight Dana

The Pacific had figured in my research, up to that point, mainly because one of the Peabody’s founding scientists, James Dwight Dana, had served as naturalist on the 1838-42 U.S. Exploring Expedition around the world. Dana saw the Pacific islands much as they were when they first entered Western lore, as places of incredible beauty and occasional terror, both due in part to the underlying volcanoes. He wrote about climbing the volcanoes, and also about gathering corals by “floating slowly along in a canoe,” studying the reefs through the clear water and pointing out specimens for his hired divers to retrieve. In the “Feejee” Islands, he did his collecting among people he regarded as “a cruel, treacherous race of cannibals.” But they were “kindly disposed towards us,” he wrote, adding, “A white man, they say, tastes bitter.”

This work led Dana to a theory about the origin of Pacific atolls with their peculiar, idyllic lagoons: Coral reefs had built up in a ring around volcanic islands, which later subsided. He was no doubt dismayed on arriving in Australia in November 1839 to find a brief notice that Charles Darwin had just proposed the identical theory. Dana generously remarked that Darwin’s work “threw a flood of light over the subject, and called forth feelings of peculiar satisfaction, and of gratefulness to Mr. Darwin.” The two men later corresponded at length, each playing the part of the gentleman scientist.

#

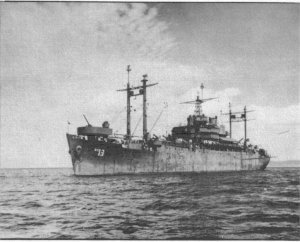

USS Panamint

Dunbar’s colleagues in the summer of 1946 were also gentlemen scientists, 22 of them altogether, invited not just from the United States, but from Russia, China, and other nations to see for themselves the appalling power unleashed just eleven months earlier on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The U.S.S. Panamint, a Navy amphibious force command ship, carried them from San Francisco, and the atmosphere was remarkably casual, even high-spirited, as the scientific delegation made its way more than 4000 miles across the Pacific. At various stops en route, the military welcomed the group with an open bar and tours of recent battle sites. (Only the summer before, Panamint itself had faced repeated torpedo and Kamikaze attacks as flagship for the invasion of Okinawa.) The scientific delegation would not be performing any studies; they were there only “for the witnessing of this impressive experiment,” as Vice Admiral William H. P. “Spike” Blandy, commanding officer of the task force, advised them. The actual science was being undertaken by the military.

Dunbar aboard USS Panamint

Dunbar’s journal thus reads like a prolonged Pacific vacation–up to day of the atom bomb blast itself. “The sky is largely overcast today and there is only a light breeze,” he wrote, early in the voyage. “It is warm enough to be comfortable on deck in shorts.” To pass the time, the scientists gave lectures each afternoon: “Today Dr. Galstoff spoke on the biochemistry of the sea, and Trask spoke on the article that claimed we were in imminent danger of destruction by the atomic bomb. He did a good of debunking it. Movies are shown on the after deck each night at 20:00.”

Bikini, roughly midway between Hawaii and the Philippines, was just the sort of Pacific atoll Dana had theorized about, a ring of coral limestone and sand islands, encircling a 229.4-square mile lagoon—roughly the size of municipal Chicago. Bikini’s 167 residents had agreed to relocate elsewhere in the Marshall Islands, under the false impression that this was to be a temporary arrangement. (The American public was apparently also deceived. The New York Times headlined its story “The Strange People from Bikini,” with a subhead noting that “they love one another and the Americans who took their home.”)

With the islanders gone, the Navy anchored a fleet of captured and war surplus vessels in the lagoon. The ambition, as an aid to the Secretary of the Navy said at the time, was to “test the ability of ships to withstand the forces generated by the atomic bomb,” and also counter “loose talk to the effect that the fleet is obsolete in the face of this new weapon.” At the

center was the battleship U.S.S. Nevada, painted red, except for the forward gun turret, which was white, indicating the bull’s-eye. Other target ships radiated out from there like spokes, to a distance of two miles. Roughly 10,000 measuring devices and cameras

Test animals

positioned in and around the fleet would assess the ability of the ships and other military equipment–the Army trucks, tanks, ammunition, gun mounts, and radar gear arrayed on the decks–to withstand nuclear attack. Rats, mice, guinea pigs, goats, and pigs were on board to test the effects of radiation.

The first bomb was dropped from a B-29 on July 1, dubbed Able Day, before the scientific delegation arrived. It was underwhelming, with the bomb falling short of its targets and sinking only five ships. The radiation quickly dispersed into the stratosphere. The second bomb was to be exploded underwater in the middle of the fleet on July 25, dubbed Baker Day, or “Boom Day,” in some of the documents provided to the scientific delegation. The military’s radiation safety unit had warned that Baker was liable to contaminate the lagoon and send a radioactive rainstorm down on any target ships that survived the blast, rendering them “dangerous for an indeterminable time afterward.” But officers generally ignored these warnings.

On Baker Day, Dunbar took up a position on the fire control deck of the Panamint, 80 feet above sea level, and 10 or 12 miles upwind from the target area. He braced his elbows on the rail and held his binoculars to his eyes as the loudspeaker called out warnings at 15 minutes, 5 minutes, and 1 minute. “My field of vision covered the center of the target area including the [aircraft carrier] Saratoga at the left, and the Nevada at the right,” he wrote. The explosion came at 8:35 a.m., on schedule. The flash and fireball reported on previous blasts happened underwater, out of sight.

“At the instant of explosion I was looking through the binoculars with my focus exactly on the spot where the burst occurred,” Dunbar wrote. “The first sign of disturbance was a white dome-like bulge from which immediately burst a geyser-like jet about half a mile in diameter that shot upward to a height of a mile or a mile and a half expanding slightly into a cauliflower at the top.” It looked, another observer remarked, as if “the world was standing on end, with the sea pouring down through a hole in the sky to the universe beyond.”

After 10 seconds, tons of water, sand, and matériel flung up into the sky “collapsed back into the lagoon,” Jonathan M. Weisgall, an attorney for the Bikini Islanders, wrote in his 1994 book Operation Crossroads, “creating a gigantic curtain of mist and spray that moved outward at more than 60 miles an hour and soon engulfed almost all of the target ships.”

After 10 seconds, tons of water, sand, and matériel flung up into the sky “collapsed back into the lagoon,” Jonathan M. Weisgall, an attorney for the Bikini Islanders, wrote in his 1994 book Operation Crossroads, “creating a gigantic curtain of mist and spray that moved outward at more than 60 miles an hour and soon engulfed almost all of the target ships.”

To Dunbar, it looked like a “ring of cloud rolling out and upward, like a smoke ring, and expanding rapidly, with a very violent, turbulent, rotary motion. It spread until, for a fleeting moment, I was ready to duck, fearing that it might roll clear out and envelop us.” Vibrations from the blast temporarily disabled the engines of Panamint. When the target area cleared, nine ships, including the 29,000-ton battleship U.S.S. Alabama, had disappeared. “The speed with which the whole thing took place leaves you gasping,” Dunbar wrote. “The violence of the forces is simply beyond human conception.”

Decontamination drill on Baker test support ship.

The invisible threat of radioactive contamination was also seemingly beyond conception for the U.S. Navy. Officers took what one member of the radiation safety unit later characterized as “a ‘hairy-chested’ approach to the matter with a disdain for the unseen hazard.” Just 90 minutes after the blast, Dunbar wrote, “we began steaming in toward the target area, coming up to within about 1 mile of the reef and 4 or 5 miles of the center of the target area.” Navy crews began working around the target vessels at noon. At 5 p.m. Panamint anchored in the lagoon, though the center of the area was “still ‘hot’ with radioactivity,” Dunbar noted, adding, “Rumor went around that the area of radioactivity was spreading and that we might have to move out of the lagoon before morning.” An observer from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was happy to advise his fellow scientists that there were no dead fish floating and that, “a few minutes after the explosion terns were flying over the island apparently unconcerned with what happened in the lagoon.”

The deadly consequences of the blast became evident only after most of the observers had headed home, when Navy seamen without protective gear began trying to decontaminate the surviving ships with anything they could lay their hands on–saltwater, soap, coconut shells, sand, ground coffee, air compressors, and old-fashioned scrubbing. A pile of sand on one such ship, “gave off a reading of 200 roentgens per day” twenty days after the blast, Weisgall wrote, “meaning that a person lingering over a ‘hot spot’ like this would reach his daily tolerance limit in just 45 seconds.” A Joint Chiefs of Staff evaluation later characterized the contaminated target ships as “radioactive stoves,” capable of burning “all living things aboard them with invisible and painless but deadly radiation.”

Working ships also became contaminated when they began taking in seawater from the lagoon for their evaporators, condensers, and other systems, including the drinking water supply. An observer on one ship saw sailors using radioactive saltwater to rinse off meat racks. “The primary concern” of Operation Crossroads, Admiral Blandy had declared during planning “is to protect the lives of Americans in this and future generations.” Instead, Weisgall wrote, “the U.S. Navy managed to expose tens of thousands of men and more than 200 ships to radioactive contamination more than 2000 miles from decent port facilities without ever having attempted … to determine how—or whether—a ship could be decontaminated.” Glenn T. Seaborg, head of the Atomic Energy Commission in the 1960s, called it “the world’s first nuclear disaster.”

The “Baker Day” test was also a disaster in international politics. Under the United Nations “Baruch Plan,” proposed just a month earlier, the United States was offering to turn its atomic weapons over to an International Atomic Development Authority, provided other nations pledged not to develop such weapons and agreed to a system of inspections. The idea of staging the tests just at the moment “when our plans for effectively eliminating them from national armaments are in their earliest beginnings” seemed inappropriate to J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, which designed the bombs. The “only important impression these tests are going to give the world,” warned Sen. James Huffman of Ohio, “is that the United States is not done with war.” In fact, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had already developed “Pincher,” a top-secret plan to bomb 30 Soviet cities as a preventive measure. The “Baker Day” headline in the New York Times declared, “Atomic Bomb Sinks Battleships and Carrier; Four Submarines are Lost in Mounting Toll; Soviet Flatly Rejects Baruch Control Plan.” The Soviet Union staged the first atomic bomb test of its own just three years later, in 1949.

For Dunbar, the experience of witnessing the blast was overwhelming. His field notes are full of drawings of the cauliflower/mushroom cloud, as if in an attempt to comprehend what he had seen. His work with fusulines and the Great Permian Extinction had in some sense prepared him to think about the annihilation of life on Earth. Back home, he spoke about “a new order of horror and destructiveness” in the world. But horror has its own half-life. The testing program was already entering global culture in ways that trivialized it. A fashion designer in Paris registered the name “bikini” for a bathing suit because, “like the bomb, the bikini is small and devastating.” For fashion writer Diana Vreeland the bikini was the “atom bomb of fashion.”

As the Cold War began, the military also minimized the catastrophic nature of the atomic bomb. “When not close enough to be killed,” a U.S. Army informational film advised in the 1950s, “the atomic bomb is one of the most beautiful sights in the world.” Dunbar soon became an advocate for fallout shelters and other Civil Defense measures and lent his eyewitness authority to the “duck and cover” mythology that nuclear attack would be survivable. In a 1951 interview for a Connecticut radio show called “Yale Interprets the News,” he described going “aboard the worst damaged target vessels” and “swimming the beach within 3 miles of the point where the bomb had burst,” just two days after Baker Day.

“If an atom bomb burst over New Haven,” he continued, “3 or 4 square miles of the business district would likely be destroyed by the blast and ensuing fire. But our suburban homes in Westville, Woodbridge, Hamden, and North Haven would suffer no more than broken windows. Our families would be safe there and we could all stand by to help fight fires, rescue the wounded, and perform the thousand services that need to be done at once to save a stricken city. Each of us will have a task to do, and our common welfare will be jeopardized by everyone who yields to panic and tries to flee.” This was a brave London-in-the-Battle-of-Britain scenario. It was of course also hopelessly optimistic.

The testing program continued. Bikini Atoll was the site of more than 20 nuclear detonations over the next dozen years. A few Bikini islanders attempted to return home in the 1970s, only to be evacuated again on account of sharply elevated levels of radioactive materials in their bodies. The atoll is today inhabited only by a few caretakers and occasional visiting scientists.

#

It was no more than a small scientific footnote to the chaos of Baker Day. But in the aftermath, a U.S. Geological Survey researcher named Harry S. Ladd was curious to know if Pacific atolls had risen up and gotten their circular shape, as Darwin and Dana had theorized, on the periphery of old volcanoes. Deep drilling on Bikini and nearby Eniwetok Atoll from 1947 to 1952 eventually passed through 1200 meters and roughly 50 million years of limestone cap formed from shallow-water coral reef. Finally the drill bit broke through into basalt, the unmistakable remains of a volcano.

Ladd posted a sign next to the borehole bearing the only positive result of the entire episode: “Darwin was right!”

END

Richard Conniff is the author of House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth (Yale, 2016)

New Neighbor, Serial Killer, Just Wants to be Friends

The ghost of Griffith Park (Photo: Steve Winter/National Geographic)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Most people are clueless that carnivores—big, scary flesh eaters—can adapt to live among us, unnoticed, even in the most densely populated landscapes. By adapt, I mean, for instance, that 4,000 coyotes are living in and around the Chicago Loop, without incident. One especially wily pack has even chosen to make its den on Navy Pier, one of the world’s top 50 tourist attractions. The 9 million or so visitors a year who come to ride the giant Ferris wheel or see an IMAX movie never notice.

It’s the same in Southern California, where a mountain lion hunts deer in Griffith Park, in the middle of Los Angeles, and may recently have snatched a koala from the city zoo. In central Spain, wolves bed down in agricultural fields on the outskirts of Madrid and picnic on wild boar. In Norway, lynx hunt in the forests just outside Oslo. In Mumbai, India, the most spectacular case of mutual adaptation, 35 leopards live in an unfenced national park in the middle of the city’s

21 million people—and because leopards and people alike have learned to be careful, there hasn’t been a human fatality in three years.

Living together with carnivores, and even walking the same footpaths (preferably at different times), is becoming the new normal as the world’s population expands to 10 billion people in this century. The carnivores simply have no choice but to live in human-dominated landscapes, because those are just about the only landscapes left. A new commentary in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution argues that we need to make coadaptation work, with a combination of “social legitimacy” for them and “tolerable levels of risk” for us. Otherwise, many carnivore species will disappear completely.

For coauthor Neil H. Carter, a wildlife ecologist at Boise State University, the term “social legitimacy” means that we need to get over the idea that “they don’t belong here,” in “my city” or “outside my door.” Carnivores were typically living in this countryside long before our cities and suburbs sprang up, and they have as much right to the landscape as we do. Adapting isn’t just about putting up with carnivores. For Carter, it’s about recognizing them as part of the natural richness of the habitat.

Europe is one place that seems to be getting coadaptation right. Carnivores there have come back in a big way, partly because farmers have abandoned marginal lands in remote areas, turning that acreage back to nature. The European Union’s habitat directive, which functions like the Endangered Species Act in the United States, has also made a major difference.

The result is a carnivore resurgence over the past 30 years that makes American boasting about “great open spaces” seem like hollow rhetoric. Not counting Russia, Europe is home to 500 million people—and 9,000 lynx, 12,000 wolves, and 17,000 brown bears. That compares with about 3,000 wolves and just 1,800 grizzly bears in our Lower 48. Even counting Alaska, we don’t compare.

John D.C. Linnell, coauthor of the new commentary, pointed out the irony. Germany had no wolves for many decades, and the great proponent of American wilderness, Aldo Leopold, was flatly disparaging after a 1935 visit: “We Americans, in most states at least, have not yet experienced a bear-less, eagle-less, cat-less, wolf-less woods,” he wrote. “Germany strove for maximum yields of both timber and game and got neither.” But Germany now has 30 wolf packs and perhaps 200 wolves, roughly double the number in the American Southwest, where Leopold first conceived his wilderness ideas.

So what does it take to increase populations of this country’s major predators? They need natural habitat that’s well protected and has an adequate prey base. “Green bridges”—wildlife overpasses and underpasses—also make a significant difference in reducing deaths from road accidents. Willing ranchers need help going back to old methods of coexistence—using guard dogs and even range riders, or cowboys, to oversee their livestock. They need help establishing marketing outlets and finding buyers for “wildlife friendly” products.

What the carnivores mostly need is a change in attitude. “We have more experience with failures,” Carter acknowledged. A system that compensates farmers when predators kill their livestock might work in Europe, but it “has failed miserably across the American West, largely because wildlife managers didn’t take the time to understand why people were so vehemently opposed to wolves. It wasn’t the economic loss.” Instead, the wolves became a symbol of lost control and of big government butting into their lives.

People need “a sense of ownership in the whole decision-making process,” said Carter. Too often, ordinary people feel left out. “Their value system and their input was never incorporated, and everything that happens after that is tainted, because it was never legitimate to begin with.”

Beyond that, all of us need to get back to the idea that carnivores “belong here; they are a part of the ecosystem; they have always been a part of the ecosystem,” said Carter. It’s not enough for our fish and game agencies to stock some trout for fishermen or build up elk populations for hunters. That same level of effort should be going to rebuild our carnivores, because they are part of the character and greatness of the country.

July 24, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Rockin’ Robin

Leon René, a West Coast R&B producer and composer, had an ornithological hit with this song, released in 1958 by Bobby Day. It fits with a tradition, dating back to the Middle Ages, of trying to imitate birdsong in music. Both René and Day found gold in the animal music theme. Just the year before, Day sang “Buzz Buzz Buzz” with the Fabulous Flames. René, born in 1902, had written the very 1940 hit “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano,” later performed by musicians from Glenn Miller to Pat Boone. Here’s the original, from the Ink Spots.

And it’s worth checking out this pretty fabulous 1972 version of “Rockin’ Robin” by Michael Jackson:

July 17, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Dead Skunk In The Middle of the Road

Loudon Wainwright III is said to have written this absurdist little country tune by accident, in 15 minutes. He later mock-boasted that it made it to number one on the hit parade for six weeks in Little Rock, Arkansas, “and only very intelligent people live in Little Rock.” It became his biggest hit, reaching number 16 on the Top 100 nationwide in 1973.

People still have a fond place for it in their redneck olfactories. A radio station in Quincy, Illinois, has played it every Friday night at 9 p.m. since 1985, as a clarion call to weekend nonsense. The stadium where Georgia Tech plays baseball plays it at the seventh inning stretch, because “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” is just too sentimental.

July 16, 2016

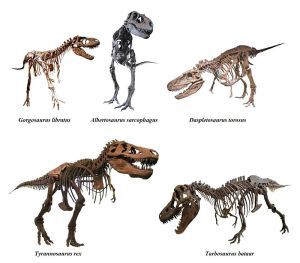

Tyrannosaurs: It’s Not Just About Rex

by Richard Conniff/Wall Street Journal

by Richard Conniff/Wall Street Journal

Given that tyrannosaurs are the most studied of all dinosaurs, and familiar to almost everyone above the age of 5 (or maybe make that 3), it’s extraordinary how little we really know about them: huge bodies, big spiky teeth, tiny arms, scary as hell. That’s about it for most of us.

Go a little deeper and we mostly go wrong, according to David Hone, a paleontologist at the University of London. “Tyrannosaurs,” he writes, in “The Tyrannosaur Chronicles,” “were not pure scavengers; they didn’t spend their lives battling adult Triceratops, they did not have poor eyesight, they could not run at 50 km/h, females were not bigger than males,” and they weren’t all Tyrannosaurus rex, that flesh-rending, scenery-chomping, lunkheaded box-office giant of our nightmares.

Mr. Hone’s unsensational and resolutely middle-of-the-road account lists 29 tyrannosaur species. He adds that

Little friends & big friends

he had to change that number three times while working on the book, because scientists have been discovering about one new tyrannosaur species a year for the past decade. Our obsession with giants like “Sue,” the celebrated Tyrannosaurus rex specimen at Chicago’s Field Museum, which measured more than 42 feet in length and weighed more than 15,000 pounds when alive, may be misplaced. Most tyrannosaurs were comparatively small—as little as 2 feet in length, with the tail accounting for half of that.

The tyrannosaurs, Mr. Hone explains, lived and evolved over a period of some 100 million years—from 167 million years ago to the dinosaur apocalypse 66 million years ago—and they roamed Asia, North America and Europe, and possibly beyond. They stayed small to midsize until the multi-ton giants came along in the final 15 million or 20 million years of tyrannosaur evolution. But it’s safe to say that all of them would have made for unpleasant company. That diorama at the Creation Museum depicting smiling children playing in a lush garden beside two tyrannosaurs? It’s wrong in so many ways, but mostly because the smile would have been on the tyrannosaurs.

Mr. Hone begins his book with a primer on basic anatomy, including helpful illustrations to take readers from premaxilla bones (just below the nostrils, or nares) to caudal vertebrae, and to sort out ilium from ischium. He goes on to explain that a primordial mutation gave some ancestral carnivore somewhere in Asia “more robust premaxillary teeth.” And thus the kings, or more properly tyrants, of the dinosaur world began their reign of terror.

Tooth of the new tyrannosaur Timurlengia euotica, found in Uzbekistan.

Those spiky teeth, D-shaped in cross-section and serrated on the inner edge, together with fused nasal bones to make the skull strong enough for its massive bite, became the defining tyrannosaur features. Though museum specimens and illustrations tend to depict neat rows of teeth that would make a tyrannosaur orthodontist proud, the reality would have been spottier: Tyrannosaurs routinely shed and replaced teeth in the course of their flesh-rending and bone-crushing. “A single tyrannosaur that lived for a decade or more might thus go

through hundreds, or even a thousand or so, teeth in a lifetime,” Mr. Hone writes. In any case, paleontologists increasingly suspect that the whole nasty array may have been hidden behind lips. (The better to smile with, my dear?)

Mr. Hone does a good job of explaining the long odds against a carcass becoming fossilized in the first place and the astronomical odds against the skin and other soft tissues being preserved. For paleontologists to rediscover and make sense of an entire superfamily of extinct species across tens of millions of years seems nearly miraculous. Though their nicknames (“Sue,” “Bucky,” “Stan,” “Scotty”) make them sound as familiar as grade-school classmates, “we have at best perhaps 30 or so decent specimens of the largest tyrannosaurines,” Mr. Hone writes.

There are as a result more questions and theories about them than answers: Were tyrannosaurs sit-and-wait predators, like cheetahs? Or was their gait—head low, tail up—efficient enough, even if not particularly quick, to engage in extended pursuit of prey, or even some form of group hunting, like wolves? Why did the arms become smaller over the course of evolution? (Mr. Hone suggests that big, powerful arms would have been deadweight as the powerful head and teeth took over all the bloody work of killing.) Were they social creatures? Did they provide parental care and bring food to their young? If they spent much of their lives sleeping, like modern predators, how did they get back on their feet again?

And, speaking of awkward, how do 15,000-pound serial killers have sex? Mr. Hone notes that birds, now recognized as the only dinosaurs to have survived the great extinction 66 million years ago, commonly mate “with little more action” than pushing their cloacas—the combined excretory-genital openings—together in what’s known elsewhere as a “cloacal kiss.” But given that tyrannosaurs had a huge, heavily muscled tail in the way, this might well have been an air kiss. Mr. Hone’s proposal is that we seek hints in the strange sex lives of ducks: “An explosively inflating organ that is both longer than the animal that bears it and helical in shape is really only the start.” And you thought tyrannosaurs couldn’t get any scarier.

A Yutyrannus rendering

It also suggests just how dramatically our theories about them can change with the discovery of new evidence. For instance, unearthing Yutyrannus, the “feathered giant” found in northeastern China in 2012, has left many paleontologists thinking that even Tyrannosaurus rex may well have been feathered and brightly colored.

At times, Mr. Hone becomes too focused on the details and neglects to bring aspects of the story to life. It’s intriguing to know that tyrannosaurs had hollow, pneumatic bones. But his explanation of how the hollow spaces in the bones functioned as part of the respiratory tract left me baffled, and he offers no hint of how they might have affected tyrannosaur locomotion.

He also misses a major opportunity for engaging readers by almost completely omitting the colorful stories of the characters who have made the discoveries, developed the theories and then fought about them. The few times he does mention them, it’s not in a way that encourages confidence. It’s odd to describe Henry Fairfield Osborn as “a great American paleontologist of the 1800s,” because the modern consensus is that his science wasn’t so great. Not to mention that he described and named Tyrannosaurus rex in 1905 and continued to work almost until his death in 1935.

But these are quibbles. For readers who got hooked on tyrannosaurs as 5-year-olds, and want to know more at 15 or 50, this book is a useful introduction to some of the most wonderfully terrifying animals ever to walk the Earth.

##

If you’d enjoy some of those stories of discovery, check out my new book House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth (Yale, 2016).

July 14, 2016

Our Blue-Butterfly Days Are Rapidly Vanishing

The large blue butterfly is on the way to recovery in the United Kingdom after having been declared extinct there in 1979. (Photo: Education Images/UIG via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

You do not need to be a naturalist to love butterflies. Dolly Parton sings about them. So does Miley Cyrus. Tracy Morgan says he used to be an angry young man in a cocoon, but “now I’m a beautiful black butterfly.” And the poet Robert Frost once celebrated the “blue-butterfly” days of spring.

But hold the lyrics. The butterflies are vanishing, according to an article in this week’s edition of the journal Science, and it’s happening even in protected areas. In a reserve in Germany’s Bavaria region, for instance, a study early this year found that just 71 butterfly species survive where there were 117 in the 19th century. That’s a 40 percent decline. In the Netherlands and England’s Suffolk County, researchers have found that 25 to 42 percent of resident breeding species are extinct.

“There is evidence for similar declines,” writes Oxford University lepidopterist Jeremy A. Thomas, “in North America, Japan, and hotspots of butterfly endemism such as Brazil, South Africa, and Australia.” Charismatic species such as the Indo-Pacific birdwings, with their six-inch wingspan, are among the victims.

Thomas acknowledges that the decline in butterflies is not exceptional. Bumblebees, dragonflies, moths, and ladybirds (or ladybugs, in this country) may be even worse off because of environmental damage inflicted by humans. Those insect groups really matter in the sense that they have ecological value for pollination and predator control. Butterflies, on the other hand, are mostly just pretty to look at.

But their very uselessness, their pointless beauty, is the one thing that has made butterflies

seem so important. I’ve always figured William Blake had butterflies in mind when he wrote that beautiful little poem: “He who binds to himself a joy / Does the winged life destroy / But he who kisses the joy as it flies / Lives in eternity’s sun rise.”

And the idea that we are destroying butterflies—not just individual butterflies but vast swaths of species—resonates ominously.

The main thing killing the butterflies, according to Thomas, is our continually intensifying use of the land, especially for agriculture. Adult butterflies are often generalists flitting from plant to plant, but their young typically depend on just one or two plant species for food and habitat. These native plant species are being shoved aside to make room for crops, plantations of exotic trees, suburban lawns, and urban development. The decline of milkweed in North America is the most notorious example. For monarch butterflies, the herbicide-induced loss of the plant that harbors their eggs and feeds their young has been a major factor in the population crash from a billion in 1990 to just 33 million today.

Unlike monarchs, about 80 percent of butterfly species are confined to narrow home ranges that can be as little as an acre, and they’re unlikely to migrate across even a half-mile of inhospitable ground to find another suitable habitat. So a neighborhood of meticulously maintained lawns, or a single highway, can be fatal for a species. Some butterfly species also have complex relationships with local ant species. The alcon blue butterfly is a classic example. Its caterpillar emits a chemical signal that tricks local ants into carrying it back to their nest, where it is safe from being jabbed by parasitic wasps. Inside the nest, it refines its signal to induce the ants to feed and tend it.

These kind of complicated relationships are easily jeopardized by change. For instance, when farmers in Europe abandon the marginal hillside fields where they used to intermittently graze livestock, that land becomes scrubbier and less grassy. That’s good news for many large mammals and a factor in Europe’s current rewilding. But it’s bad news for the butterflies that depended on those grasslands. Thomas lists pollution, drainage schemes, and climate change among the other landscape-scale factors threatening butterflies.

It is, however, possible to restore butterfly populations, with a little effort. By paying closer attention to the nuances of species ecology, protected areas in the United Kingdom have brought back four of six nationally threatened butterfly species. For example, the iconic large blue butterfly went extinct there in 1979, just about the time Thomas discovered that its life cycle requires it to feed on the grubs of a particular red ant species. By importing butterfly stock from Sweden and focusing on those red ants, conservationists have established a population of about 10,000 butterflies back on old haunts.

Hey, Tracy Morgan, I’m betting you could find room here for the other kind of butterflies, too.

People can make that kind of difference for butterflies everywhere. The best way to start is by scaling back that big, useless green lawn. (Morgan, comedian and self-declared butterfly, could set a great example with the enormous lawn at his new house in New Jersey.) If you have the money, hire a landscaper specializing in butterfly gardens. Or go to local gardening-for-butterflies lectures and pick up the plants they recommend for your neighborhood. (Here’s a list for the U.S. mid-Atlantic region. The Xerces Society is also a good source for information. )

People clearly care about butterflies. Thomas notes that volunteers in Britain have walked about 466,000 miles monitoring butterfly populations over the past 40 years. That’s like walking to the moon and back counting butterflies.

Time for the rest of us to take the first step.

July 10, 2016

Animal Music Monday: From the Diary of a Fly

This is a piece by Béla Bartók, both whimsical and empathetic, about a fly becoming caught in a spider’s web. It’s built on what musical types call ostinato, a single repeated musical phrase, and somehow over the course of less than two minutes, this captures both the buzzing repetitiveness of an insect’s life and the desperation in the face of death.

This one caught my attention because I have written about flies, without much empathy, in my book Spineless Wonders (currently out of print but one of these days I will get it back as an ebook). I have also written about spiders building their webs, and in that case I felt so much empathy that I went out to a climbing wall and tried to build my own web. I wrote about it in my book Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time. Here’s an excerpt:

One day back home, I was watching a spider spin its astonishing construction between my desk lamp and telephone (it was a slow day), and I suddenly wanted to become a spider, at least for a little while. I picked up the phone (a cataclysm for the spider) and found a climbing instructor named Stefan Caporale, who agreed to help me build my own orb web, in the corner between two climbing walls at the YMCA in Worcester, Massachusetts. Caporale fitted me out with a climbing harness and Jumar ascenders. I’d never done any rope climbing, but with a slingful of the metal clips called carabiners over one shoulder and a rope bag in lieu of a silk gland over the other, I felt like Charlotte’s Web meets Rambo.

I was, of course, going to have to cheat,

starting from the moment I climbed one wall, tied my first line, and looked across 15 feet (4.5 meters) of open space to the point where I’d be anchoring the opposite end. A spider bridges this span the same way it makes a parachute, by lifting its hind end and paying a length of silk out onto the breeze. This wasn’t going to work for me.

It was cheating just to look. A spider knows what’s happening around it largely by touch. It relies on as many as 3,000 vibration sensors, called slit sensilla, most of them on its legs. Eberhard had e-mailed me this thoughtful advice on my web-building: “Do it (as much as you can) with your eyes closed.”

Having tied my line to a bolt hanger, I climbed back down and climbed up the other wall, where I pulled my spanning line taut. Then I shinnied back out the spanning line, trailing rope behind me. The idea was to leave this rope slack and let the middle of it drop down to become the hub of the web. A spider can do this blindfolded. Then it rappels down from the hub and stretches a spoke to the bottom of the web, keeping the whole thing under tension. Creeping out into midair, 15 feet (4.5 meters) above the concrete floor, I moved by millimeters. My muscles quivered. Then I began to oscillate, until I was flailing wildly from side to side and spinning sweat in all directions. It took me a half hour to get the first spokes in place. The average orb-web spider, working at an effortless trot, would already have completed an entire web, with perhaps 30 spokes. Many spiders rush to complete their webs in the last minutes before dawn, to minimize their daylight exposure to predators and also to have everything nice for insect rush hour.

Check out the whole story in Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time. And listen to the Bartok again. That’s a happy ending: The fly gets away.