Richard Conniff's Blog, page 16

October 9, 2016

The Man Who Invented Modern Ecology

Given four minutes, this film by Patrick Lynch at Yale says a great deal about G. Evelyn Hutchinson, who founded the science of modern ecology, largely by studying a lake just outside New Haven:

Among his many other influences, other writers made Hutchinson’s work the basis for the Gaia Theory, the popular idea of the Earth as a “single giant living system,” in which organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings to form a synergistic self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet.

You can read more about Hutchinson in my book House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth (Yale, 2016).

October 7, 2016

Maggots for Bambi: Endangered Florida Deer Face a Gory Attack

Key deer–& sparing you the sight of maggots for Bambi. (Photo: Steve Waters/’Sun Sentinel’/MCT via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Let’s face it: Key deer, a slightly smaller, stockier subspecies of the common white-tailed deer, had plenty of problems to start with. Only about 800 of them survive, confined to a few small islands in the Florida Keys. You could whip through their entire habitat in about 10 minutes on Route 1, and plenty of motorists do, incidentally killing about 150 of the deer every year. They’re on the endangered species list.

Sound bad? Early this week, it got much worse.

Staff at the National Key Deer Refuge found deer infested with maggots of the New World screwworm fly, an invasive species that hasn’t been seen in this country in half a century. The flies have a nasty habit of laying their eggs on open wounds, and when they hatch, the maggots feed by digging corkscrew holes into the flesh of the host animal.

“They’re in as gory of a condition as you can imagine,” Dan Clark, the refuge manager, told a reporter. He wasn’t exaggerating: One

Infected deer

photo showed a deer waiting stoically as the writhing maggots seemed to be peeling the skin off the back of its head. U.S. Fish and Wildlife staff charged with protecting the deer began euthanizing the victims instead, by firing a spring-loaded bolt into their skulls. Then they collected the maggots to prevent them from spreading. So far about 40 of the infested deer have died.

Other government officials weren’t fretting so much about the endangered deer. They worried instead about cattle, another invasive species. Mention of screwworm flies “sends shivers down every rancher’s spine,” said Adam H. Putnam, Florida’s commissioner of agriculture. He declared a state of emergency, noting that Florida’s livestock industry “generates $2.78 billion in annual economic impact and supports more than 41,000 jobs.” The state has established an “animal health check point” to spot screwworm-infested pets in vehicles leaving the quarantined zone.

Despite the scary headlines, livestock ranchers (and pet owners) probably don’t have much to worry about. The U.S. government succeeded in eradicating the screwworm fly from this country in the mid-20th century, though it persisted in South America and on a few Caribbean islands. It did so then—and will do so again—with the help of the sort of taxpayer-funded basic research that shortsighted politicians love to ridicule. Back then, U.S. Sen. William Proxmire got wind of a $250,000 federal research grant to a Texas entomologist named Edward F. Knipling. Proxmire singled out the project for one of his Golden Fleece Awards because studying “the sex life of parasitic screwworm flies” just seemed like a waste of taxpayer dollars.

Knipling was developing what as “the single most original thought in the 20th century.” It involved releasing large quantities of artificially sterilized male screwworm flies. Female flies of the species mate only once, and because mating with sterilized males produced no eggs, the wild population quickly dwindled, leading to eradication in 1966.

The continuing benefit to cattle ranchers just from the screwworm program is worth an estimated $1 billion a year, not a bad return on a small taxpayer investment in basic science. Public health agencies have also used the “sterile insect technique” against a host of other human and animal pests, and they have announced plans to use it again in the Florida Keys.

So where does that leave the Key deer? I’d like to say that all will be well once the screwworm fly invasion ends. But there is plenty of bad news to spread around: Rising sea levels mean that what’s left of Key deer habitat—low-lying hardwood hammocks, mangroves, and freshwater wetlands—could all vanish in this century. When that happens, there will be no place left for Key deer to call home.

October 3, 2016

Killing Off The Wildlife Is Just a Slow Way to Kill A Forest

(Photo: Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

In the aftermath of bushmeat hunting, pet trade harvesting, habitat fragmentation, selective logging, and other human intrusions, forests and national parks can still look surprisingly healthy. They may even feel like beautiful places for a walk in the woods. But these forests face what researchers in one recent study describe as a “silent threat” due to the rapid decimation of wildlife almost everywhere in the tropics. Without wildlife, forests rapidly deteriorate, losing their value for carbon storage and becoming unsustainable.

That’s because tropical forests, particularly in the Americas, Africa, and South Asia, are primarily composed of tree species that depend on animals to disperse their seeds. This is especially true for the tall, dense canopy trees that are best at carbon storage, a critical factor in climate change calculations. For instance, in a Smithsonian Institution research forest on Barro Colorado Island in the Panama Canal, roughly 80 percent of canopy trees produce large, fleshy fruits. A ravenous cacophony of animals zeroes in on these trees as the fruit ripens.

In a healthy forest like Barro Colorado, the customers may include monkeys, big pig-like tapirs, large rodents like the agouti, toucans with their long, colorful bills adapted for snatching fruit, and a long list of hungry birds, fruit bats, and other species. After these happy diners have eaten

and wandered off, they excrete the seeds of the fruit they have eaten all around the forest. Most of the resulting seedlings inevitably die. But in patches of sunlight or otherwise suitable ecological niches, some find the conditions they need to flourish, ensuring that the tree species remains a part of the forest.

Without wildlife to disperse the fruit, on the other hand, the result is a rain of fruit and seeds in the immediate vicinity of a tree. Even more seedlings die, and the survivors grow more slowly because of crowding and competition for sunlight and water. That’s bad news for the tree species.

In a new study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a team led by Trevor Caughlin, then a forestry student at the University of Florida, looked at the effects of hunting on a wildlife sanctuary in western Thailand. With the help of sophisticated computer modeling, they calculated that the loss of seed-dispersing wildlife multiplied the risk that a tree species would become extinct more than 10-fold over just a century. But the effects of losing wildlife can show up even sooner. Local extinctions of tree species are occurring in Thailand, said Caughlin, as elephants, gibbons, bears, and other seed-dispersing species vanish.

A recent study published in the journal Nature Communications found that declining populations of large seed-dispersing animals can lead to a 60 percent reduction in the abundance of the trees that depend on them. Wind-dispersed species, which tend to be less effective at carbon storage, proliferate in their place. Those researchers calculated that removing just half the wildlife from forests in tropical Africa and America—a modest loss compared with current reality—would reduce aboveground carbon storage there by 2.1 percent. The coauthors note that this would release the carbon equivalent of 14 years of Amazonian deforestation.

All this has come as “a surprise for many of us in forest conservation,” said Caughlin in an interview. “Trees seem really permanent and stable. A single tree can live for hundreds of years and produce hundreds of thousands of seeds, and from that perspective, it shouldn’t seem like the loss of seed-dispersing animals should be a big deal. They can wait it out.

“But these studies suggest that when you lose the seed-dispersal services that the animals provide, you will lose biodiversity value, and you will lose carbon storage in that forest,” he added. “You would expect it would take a long time. But it doesn’t.” He cited another recent study showing that the loss of toucans and other animal seed dispersers is causing palm trees in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest to adapt, over a matter of decades, by evolving smaller seeds.

People who aren’t worried about climate change may think it’s no big thing if forests lose a little carbon storage. But storing carbon is the basis for an entire system of “green finance,” in which companies and countries try to mitigate their carbon footprint by paying to protect tropical forests. These forests are an attractive target because they store about 40 percent of all the terrestrial carbon on Earth—and the worldwide penchant for cutting them down now releases as much as 17 percent of global carbon emissions each year.

Beyond carbon storage, the people putting up the money also often take credit for other “ecosystem services” these forests ostensibly provide. Studies increasingly suggest, however, that what conservationists call “empty forests,” forests without wildlife, lose their ability to provide many of those same ecosystem services. They are no longer nearly so good at protecting water quality, preventing soil erosion, and nurturing pollinators and biological pest control. Caughlin adds that losing seed-dispersing wildlife also compromises the wild stock for fruits beloved by humans, including mangoes, tamarinds, and passion fruit—sacrificing genetic resources that might prove critical when new diseases or a changing climate threatens domesticated varieties of these fruits.

Here is the bottom line. “Empty forests” are not really forests at all until we act to bring back the wildlife that enables them to function.

Killing Off The Wildlife Is Like Clear-Cutting the Forest

(Photo: Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

In the aftermath of bushmeat hunting, pet trade harvesting, habitat fragmentation, selective logging, and other human intrusions, forests and national parks can still look surprisingly healthy. They may even feel like beautiful places for a walk in the woods. But these forests face what researchers in one recent study describe as a “silent threat” due to the rapid decimation of wildlife almost everywhere in the tropics. Without wildlife, forests rapidly deteriorate, losing their value for carbon storage and becoming unsustainable.

That’s because tropical forests, particularly in the Americas, Africa, and South Asia, are primarily composed of tree species that depend on animals to disperse their seeds. This is especially true for the tall, dense canopy trees that are best at carbon storage, a critical factor in climate change calculations. For instance, in a Smithsonian Institution research forest on Barro Colorado Island in the Panama Canal, roughly 80 percent of canopy trees produce large, fleshy fruits. A ravenous cacophony of animals zeroes in on these trees as the fruit ripens.

In a healthy forest like Barro Colorado, the customers may include monkeys, big pig-like tapirs, large rodents like the agouti, toucans with their long, colorful bills adapted for snatching fruit, and a long list of hungry birds, fruit bats, and other species. After these happy diners have eaten

and wandered off, they excrete the seeds of the fruit they have eaten all around the forest. Most of the resulting seedlings inevitably die. But in patches of sunlight or otherwise suitable ecological niches, some find the conditions they need to flourish, ensuring that the tree species remains a part of the forest.

Without wildlife to disperse the fruit, on the other hand, the result is a rain of fruit and seeds in the immediate vicinity of a tree. Even more seedlings die, and the survivors grow more slowly because of crowding and competition for sunlight and water. That’s bad news for the tree species.

In a new study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a team led by Trevor Caughlin, then a forestry student at the University of Florida, looked at the effects of hunting on a wildlife sanctuary in western Thailand. With the help of sophisticated computer modeling, they calculated that the loss of seed-dispersing wildlife multiplied the risk that a tree species would become extinct more than 10-fold over just a century. But the effects of losing wildlife can show up even sooner. Local extinctions of tree species are occurring in Thailand, said Caughlin, as elephants, gibbons, bears, and other seed-dispersing species vanish.

A recent study published in the journal Nature Communications found that declining populations of large seed-dispersing animals can lead to a 60 percent reduction in the abundance of the trees that depend on them. Wind-dispersed species, which tend to be less effective at carbon storage, proliferate in their place. Those researchers calculated that removing just half the wildlife from forests in tropical Africa and America—a modest loss compared with current reality—would reduce aboveground carbon storage there by 2.1 percent. The coauthors note that this would release the carbon equivalent of 14 years of Amazonian deforestation.

All this has come as “a surprise for many of us in forest conservation,” said Caughlin in an interview. “Trees seem really permanent and stable. A single tree can live for hundreds of years and produce hundreds of thousands of seeds, and from that perspective, it shouldn’t seem like the loss of seed-dispersing animals should be a big deal. They can wait it out.

“But these studies suggest that when you lose the seed-dispersal services that the animals provide, you will lose biodiversity value, and you will lose carbon storage in that forest,” he added. “You would expect it would take a long time. But it doesn’t.” He cited another recent study showing that the loss of toucans and other animal seed dispersers is causing palm trees in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest to adapt, over a matter of decades, by evolving smaller seeds.

People who aren’t worried about climate change may think it’s no big thing if forests lose a little carbon storage. But storing carbon is the basis for an entire system of “green finance,” in which companies and countries try to mitigate their carbon footprint by paying to protect tropical forests. These forests are an attractive target because they store about 40 percent of all the terrestrial carbon on Earth—and the worldwide penchant for cutting them down now releases as much as 17 percent of global carbon emissions each year.

Beyond carbon storage, the people putting up the money also often take credit for other “ecosystem services” these forests ostensibly provide. Studies increasingly suggest, however, that what conservationists call “empty forests,” forests without wildlife, lose their ability to provide many of those same ecosystem services. They are no longer nearly so good at protecting water quality, preventing soil erosion, and nurturing pollinators and biological pest control. Caughlin adds that losing seed-dispersing wildlife also compromises the wild stock for fruits beloved by humans, including mangoes, tamarinds, and passion fruit—sacrificing genetic resources that might prove critical when new diseases or a changing climate threatens domesticated varieties of these fruits.

Here is the bottom line. “Empty forests” are not really forests at all until we act to bring back the wildlife that enables them to function.

September 23, 2016

The Real Threat on the Border Threatens Poor Nations

Tuta absoluta may sound like vodka, but it’s Ebola for tomatoes. (Photo: Peter Buchner)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

You may not think of Portal, North Dakota, a town of 120 people on the Canadian border, as a key link in national defense. But late last month, United States Customs and Border Protection agents there boarded a freight train entering the country and found six carloads contaminated with invasive insects and seeds from China and Southeast Asia. They were the kind of invasive species that demolish crops, destroy people’s livelihoods, and displace indigenous wildlife.

The government sealed three carloads and sent them back to Asia, releasing three others to the owners after decontamination. It was a reassuring victory for American agriculture and ecosystems—the sort of save that happens every day on American borders. Ample experience with the destructive power of invasive species, from the gypsy moth to the emerald ash border, has taught this country the importance of being alert to imported danger.

Other nations aren’t so careful, according to a new study in the journal Nature Communications, and that’s likely to become a major problem, especially for low-income countries, as

global trade and travel continue to expand. Most such countries, the authors found, now focus their border screening efforts on five or fewer species they regard as potential threats. To put that in perspective, the United States alone now has 30,000 invasive alien species, and they do an estimated $148 billion worth of damage every year. Countries without proper screening have no idea just how big a risk they are taking.

The threat from invasive species in coming decades will “differ markedly from current threat levels,” the authors write, and will come down hardest on regions “where economies and food production systems are often fragile and human populations are particularly vulnerable to food shortages.” Wildlife and plant species will also suffer, because many of those same countries are home to major biodiversity hot spots, particularly in Central America, Africa, central Asia, and Indochina.

The new study is worth thinking about because of a trend among certain ecologists to argue that the invasive species problem is exaggerated and that we should all just relax a little. A separate and unrelated trend treats concern about alien invasive species as some kind of nativist bigotry, “biological xenophobia,” like Donald Trump raving about Mexicans and Muslims. One animal rights activist has even likened these programs to Nazi genocide, writing, “The types of arguments made for biological purity of people are exactly the same as those made for purity among animals and plants.” But people facing the invasive species problem in the developing world would roll their eyes at such arrant nonsense.

“This is not about some campaign to maintain an artificial purity,” said Jeffrey S. Dukes, an ecologist at Purdue University and coauthor of the new study. “This is about doing our jobs as stewards of a sustainable planet.” Among the countries the study identified as unprepared to deal with the threat of invasive alien species, he listed Peru, Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, and Thailand—all hot spots for species diversity. All are also highly vulnerable subsistence economies.

“In developing countries,” said Dukes, “people live much closer to the land, they are much more dependent on benefits from nature, and they are much less insulated from fluctuations in crop output, or any kind of economic mishap. So you have a situation where there is very little protection against species coming in and causing problems, and very little protection for people once those things arrive. Anything we can do to prevent people in the developing world from dealing with these long-term problems is going to prevent potentially catastrophic changes in their lives.”

One problem for custom agents in border countries is that invasive species can be difficult to identify, or even to see. One of the pests found in the North Dakota incident, for instance, was a miniature fly. It looks trivial but can decimate fruit orchards. Another worrisome invader, Panama disease, is a soil fungus that targets banana plants. A poorly trained customs agent might not even know to look for it. But in the 1950s, a strain destroyed the world’s most popular banana variety, the Gros Michel, and wiped out farms across Central and South America. Now a new strain from Taiwan threatens the Cavendish banana, which replaced the Gros Michel.

Likewise, Tuta absoluta is a very serious moth, with a tiny caterpillar that burrows into plant leaves, making it hard for an untrained custom agent to detect. It has thus hitchhiked around the world from its home turf in South America. In Nigeria, they call it “tomato Ebola,” and this year it destroyed 80 percent of the tomato crop, driving the price from $1.20 to $40 a basket over just three months.

The new study urges vulnerable countries to start the process of protecting themselves by making a proper inventory of invasive alien species that are already present. They need to begin having a conversation about finding cost-efficient strategies, said Dukes, for instance, by coordinating with neighboring countries and taking advantage of international programs. The lesson from encounters with Panama disease, Tuta absoluta, and other invasive pests is that it’s infinitely cheaper to prevent the problem from getting started rather than waiting to fix it when it’s already too late.

There’s one way ordinary travelers can help: The biggest threat in low-income countries comes not from trade, surprisingly, but from air-passenger traffic. That bit of fruit or meat people smuggle into the country with the idea that it’s harmless can easily conceal a catastrophe for people and ecosystems that can least afford it.

September 17, 2016

America’s Wildlife Body Count: Your Tax Dollars at Work.

by Richard Conniff/The New York Times

by Richard Conniff/The New York Times

Until recently, I had never had any dealings with Wildlife Services, a century-old agency of the United States Department of Agriculture with a reputation for strong-arm tactics and secrecy. It is beloved by many farmers and ranchers and hated in equal measure by conservationists, for the same basic reason: It routinely kills predators and an astounding assortment of other animals — 3.2 million of them last year — because ranchers and farmers regard them as pests.

To be clear, Wildlife Services is a separate entity, in a different federal agency, from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, whose main goal is wildlife conservation. Wildlife Services is interested in control — ostensibly, “to allow people and wildlife to coexist.”

My own mildly surreal acquaintance with its methods began as a result of a study, published this month in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, under the title “Predator Control Should Not Be a Shot in the Dark.” Adrian Treves of the University of Wisconsin and his co-authors set out to answer a seemingly simple question: Does the practice of predator control to protect our livestock actually work?

To find out, the researchers reviewed scientific studies of predator control regimens — some lethal, some not — over the past 40 years. The results were alarming. Of the roughly 100 studies surveyed …

September 16, 2016

How China Could Lead the World in Getting Reforestation Right

A site in Sichuan that’s part of the world’s largest reforestation project. (Photo: Eye Ubiquitous/UIG via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart

What if you undertook the world’s largest reforestation program but planted the wrong trees? That’s what China’s been up to. Since 1999, it has spent $47 billion planting trees on 69.2 million acres of abandoned farm fields and barren scrubland.

That’s an area almost equivalent to New York and Pennsylvania combined—and should be great news in an era of worldwide deforestation. Moreover, from China’s point of view, the program has succeeded at its original purpose, controlling soil erosion. But the vast majority of the new forests consist of only a single tree species, according to a new study in the journal Nature Communications. That is, China has been creating tree plantations—monocultures, not forests—and with nonnative trees. That choice has sacrificed one of the major benefits of healthy forests: diversity of plants and wildlife.

The study, led by Princeton University researchers, puts an optimistic spin on these findings. The coauthors argue that China could

easily switch to mixed forests instead of monocultures and eventually to native forests. This change of focus “is unlikely to entail major opportunity costs or pose unforeseen economic risks to households.”

The change would also be timely because the earliest plantings under China’s Grain for Green Program were aimed at fast growth and income production for local farmers. That means some plantations are approaching the time for harvest and replanting. Taking that opportunity to make the relatively minor shift to mixed forests, with two to five tree species, would provide all the same economic benefits, the researchers argue, while significantly increasing populations of birds, bees, and other wildlife.

China began the Grain for Green Program largely because of major erosion and flooding problems resulting from the massive deforestation under Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s. The reforestation program primarily operates with cash payments to encourage rural households to plant trees on sloping fields and scrubland. Timber production has been the main economic focus, with farmers typically planting only one kind of tree, typically either eucalyptus, Japanese cedar, or nonnative bamboo species.

Because there is no nationwide system for tracking tree composition from province to province, study lead author Fangyuan Hua and her coauthors first had to sift through 258 scholarly publications to determine what had been planted and where. Of 202 locations reported, 166 were monocultures.

Then, to figure out how different forest types affected wildlife, the researchers undertook field studies of reforestation sites in south-central Sichuan province, counting birds and bees as a stand-in for overall diversity. They found that Grain for Green Program forests, overall, had 17 to 61 percent fewer birds than native forests, and 49 to 91 percent fewer bee species. In some cases, monoculture forests were worse than cropland for wildlife.

The level of loss was far lower for mixed forests than for monocultures. In interviews with farmers, Hua learned that “in quite a few cases,” they had already made the switch to mixed forests after learning the hard way that monocultures were more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and marketplace fluctuations. The researchers found no significant loss from the shift to mixed forests, even when they looked only at the economic benefit from timber and ignored other potential benefits.

In an interview, Hua noted that in April of this year, China’s central government promulgated a new system for recognizing and paying for ecosystem benefits, possibly making it more amenable to including biodiversity among the considerations for the reforestation program. Moreover, China’s system of government, with a clear line of command from the Central Committee down to the grassroots level, has the potential to make that sort of major change far more rapidly than a democratic system could.

Coauthor David Wilcove, a Princeton University ecologist and an evolutionary biologist, added that a new focus on biodiversity could make the Chinese program a model at a time when many other nations are just beginning to formulate reforestation plans.

Everywhere in the world, he said, “people are leaving the rural areas, moving into urban areas.” Even in Sichuan, “I remember being struck by the number of people working in the fields who were quite elderly. There weren’t any young people.” For urbanization to work, the best agricultural land has to become far more productive. But in marginally productive areas, “I think we are going to see bona fide land abandonment, and that’s going to create opportunities around the world for reforestation.

“The critical policy question is how to restore forests that provide multiple benefits to society, including preventing soil erosion, providing timber, and sustaining wildlife,” Wilcove added. As the first country to undertake large-scale reforestation, China has the opportunity to lead the world by doing reforestation right.

September 9, 2016

Sorry, Right-Wing Hacks: Zika’s No Reason for a DDT Comeback

Osprey coming home on the Connecticut River (Photo: Kris Rowe)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

In New England, where I live, this is the time of year when ospreys take their last turn on the waterways before heading south. They’ve mated, reared their young, and seen their fledglings take wing and begin to hunt for themselves. If you are lucky and know your local watering holes, you can still sometimes see them plunging out of the sky and carrying home blood-spangled fish in their talons. It is one of the great spectacles of summer.

But only for a little while longer. Soon the ospreys will migrate 2,500 miles or more, down to the Caribbean or the northeastern coast of South America, where males and females will overwinter separately. They’ll return in March, find their old nest mate (they’re faithful to mates and nest sites, more or less), and begin the ritual once again.

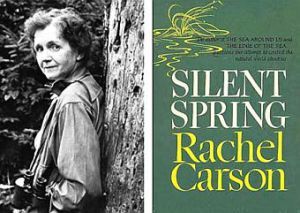

The resurgence of ospreys from near extinction in the 1970s to their modern abundance always makes me think with gratitude of Rachel Carson and the demise of DDT as a standard tool of mosquito control in this country. Her book Silent Spring, published in 1962, first alerted Americans to the risky business of spraying the countryside with as much as 80 million pounds of DDT, an untested chemical, in a single year. One effect of DDT, scientists were demonstrating, was the fatal thinning of the eggshells of ospreys, eagles, peregrine falcons, brown pelicans, and other species. The eggs collapsed under the weight of the nesting parent, and generations were lost. As a result, the osprey population in my home territory, the lower Connecticut River Valley, plummeted from 200 nesting pairs to just two by the early 1970s. The same thing happened to ospreys and other species nationwide. Then the Nixon administration banned most uses of DDT in this country, and wildlife slowly began to recover.

The resurgence of ospreys from near extinction in the 1970s to their modern abundance always makes me think with gratitude of Rachel Carson and the demise of DDT as a standard tool of mosquito control in this country. Her book Silent Spring, published in 1962, first alerted Americans to the risky business of spraying the countryside with as much as 80 million pounds of DDT, an untested chemical, in a single year. One effect of DDT, scientists were demonstrating, was the fatal thinning of the eggshells of ospreys, eagles, peregrine falcons, brown pelicans, and other species. The eggs collapsed under the weight of the nesting parent, and generations were lost. As a result, the osprey population in my home territory, the lower Connecticut River Valley, plummeted from 200 nesting pairs to just two by the early 1970s. The same thing happened to ospreys and other species nationwide. Then the Nixon administration banned most uses of DDT in this country, and wildlife slowly began to recover.

This year, though, my gratitude to Carson, and my pleasure in ospreys, is complicated by the political response to the devastating birth defects and deaths from mosquito-borne Zika virus, along with the persistent effects of mosquito-borne West Nile virus, which has killed

more than 2,000 people since it arrived in the United States in 1999. That’s on top of the 438,000 deaths in 2015 from mosquito-borne malaria, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Zika outbreak has inspired a proliferation of headlines like the one in a June 6 opinion piece in the New York Post: “The Answer to Zika Is Obvious: Bring Back DDT.” These articles are always written by right-wing political hacks with limited familiarity with science. Apart from the chance to use DDT as a political brickbat, they also have no real interest in public health.

People who have spent their lives working on mosquito-borne disease would tell them, first of all, that mosquitoes had already evolved resistance to DDT in many areas, long before Rachel Carson’s book, in part because manufacturers had enthusiastically promoted its indiscriminate use. Second, the federal government never banned use of DDT for public health issues and had no power to ban it abroad.

Mosquito control efforts began to fail in many countries for lack of funding, brought on largely by complacency and political mismanagement once the malaria threat had been somewhat reduced. If you want a good analogy for what happened, look at the congressional failure earlier this year to allocate emergency funding for Zika control. It was the usual partisan blunder fest: Republicans saddled the bill with provisions promoting the Confederate flag and putting limits on Planned Parenthood. Democrats balked. And the public be damned.

Health workers would tell the political hacks, finally, that DDT continues to be used in many countries, and U.S. tax dollars still pay for it through foreign aid block grants. Antimalaria workers spray DDT on the

Spraying DDT in the home, 1955 (Photo: Orlando/Three Lions/Getty Images)

interior walls of homes as a last resort, when safer pesticides have failed. They do it because it can save babies’ lives. But they also recognize, as one specialist in tropical diseases and pesticides told me, that they are “putting DDT in the mouths of babies through the mother’s milk” and that studies have linked DDT exposure to increased incidence of high blood pressure, reproductive disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease, among other health problems. Those political hacks blindly promoting DDT will tell you it is absolutely safe. So offer to spray it in their houses.

In truth, no one wants to live with DDT when other, safer measures are available. The best way to fight Zika and other mosquito-borne diseases is to start by consulting the latest guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which, by the way, is also underfunded because of congressional bickering and complacency. You’ll note the key phrase “source reduction,” which mainly means applying larvicide to kill immature mosquitoes in local waterways and also getting rid of all the incidental places—spare tires, abandoned pools, random containers—where water accumulates and mosquitoes breed. Repellents, protective clothing, proper window screens, and in problem areas, aerial spraying of less dangerous pesticides can also help. (But just last week, South Carolina learned the danger of aerial spraying even supposedly safe pesticides: One farm lost 2.5 million honeybees on the spot.)

We can have public health without sacrificing our environment, our children’s health, and our wildlife. I will continue to watch my ospreys with pleasure and honor Rachel Carson for helping to save them, and us. The politically motivated call for a return of DDT is just a mindless bid to go back to that blighted era when we thought the only way to save the world was to destroy it.

September 8, 2016

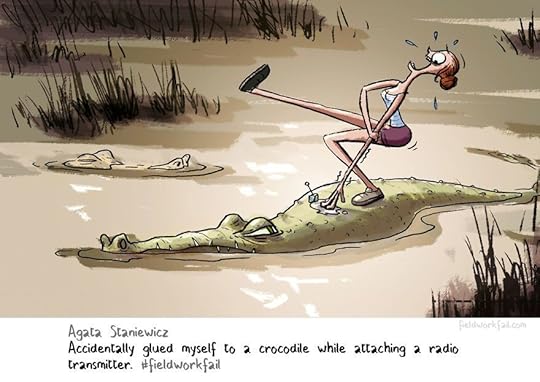

Embarrassing Moments in Research: #FieldWorkFail Illustrated

Scientists doing fieldwork sometimes get into seriously embarrassing, or even dangerous, situations. Some of them end up, tragically, on the Wall of Dead: A Memorial to Fallen Naturalists.

Scientists doing fieldwork sometimes get into seriously embarrassing, or even dangerous, situations. Some of them end up, tragically, on the Wall of Dead: A Memorial to Fallen Naturalists.

But others live to tell the tale, and dine out on their own mini-disasters.

French illustrator Jim Jourdane noticed and has produced a highly entertaining series of drawings of fieldwork: “To make these illustrations,” he explains, “I use stories shared on twitter by scientists with the #fieldworkfail hashtag.”

My favorite:

September 2, 2016

After 500 Million Years, Doomed to Decorate Toilet Tanks

A chambered nautilus off Palau, Micronesia (Photo: Reinhard Dirscherl/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Humans have for centuries coveted the chambered nautilus for its elegantly spiraled shell. But too much beauty can be a dangerous gift. We buy nautilus shells in unbelievably huge numbers, with the United States alone importing 789,000 of them during one recent five-year period, mostly to gather dust as knickknacks. As a result, chambered nautilus populations appear to be crashing in their deep-sea Indo-Pacific habitat.

Later this month, a conference in South Africa will take up the question of what to do about it. Four nations, including the United States, have proposed protecting the nautilus under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. A CITES II listing would not ban the trade but would sharply limit it, according to Frederick Dooley, an evolutionary physiologist at the University of Washington.

The Center for Biological Diversity has also petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the chambered nautilus under the Endangered Species Act, which would completely end imports. (The nautilus is found in American Samoa, a U.S. territory. But its range extends from Indonesia to the Philippines.)

Dooley, coauthor of a recent review of nautilus biology, says he has seen nautilus shells being sold by the basketful in Hawaii tourist shops for as little as $4.99 apiece. If someone has bothered to polish the shells to bring out their pearliness, the price may go up to $9 apiece. “They mostly end up being stuck on

the back of the toilet,” he said. You can also buy them on Amazon for $26, and the higher-quality ones sought by serious collectors can sell for upwards of $100.

Most of the nautilus catch now comes from the Philippines. With other fisheries there depleted, fishermen now set traps 1,000 feet deep to harvest the nautilus as one of their last remaining meal tickets. But for all the work put into it, the catch has declined 80 percent since the 1980s.

Most people, on both the buying and selling sides, have little grasp of what they are dealing in. The nautilus is a cephalopod, related to the squid and the octopus, and “people think of squid and octopus being quick to reproduce,” said Dooley. But the chambered nautilus is not calamari: Recent research has demonstrated that it is rare in the wild and takes about 15 years to reach sexual maturity.

Our standard image of “very long-lived, slow-to-reproduce animals” is a giant tortoise or an elephant, said Lauren Vandepas, a doctoral student who collaborates on the nautilus research. We don’t think of invertebrates that way. But this is a mistake.

One other factor makes large-scale commercial exploitation misguided: The nautilus has survived largely unchanged for half a billion years and is thus older than almost anything else alive on Earth. “Somehow this type of organism—the ammonoids and nautilus—have lived for 500 million years and have survived five mass extinctions,” said Dooley, “and now humans are wiping them out.”

The researchers are concerned that local extinctions, in the Philippines or elsewhere, could threaten the entire nautilus population. They have found remarkably little genetic variation among nautilus populations, even ones separated by vast stretches of open ocean. The nautilus moves by jet propulsion, but it typically travels only a mile or two in a day. Yet the genetic uniformity of different populations suggests that they are somehow interbreeding. One possibility is that each population is essential as a stepping-stone allowing the flow of genes across the entire Indo-Pacific meta-population. Removing one stepping-stone could thus have much broader implications, leading to permanent isolation of populations.

When that happens, said Dooley, “you get speciation”—that is, isolated populations become separate species—“or extinction, and extinction is a lot more common.”