Richard Conniff's Blog, page 13

April 19, 2017

Why Wait for De-Extinction? Finding & Saving Lost Species Now

Alive? Myanmar’s “extinct” pink-headed duck. (Photo: Philip Nelson)

by Richard Conniff/Scientific American

A few years ago at a bar in Reno, graduate student John Zablocki was talking about his research on the rediscovery of lost species—those presumed to have gone extinct only to turn up again alive and well. “The Lord Howe Island stick insect,” someone down the bar remarked, recalling the widely reported 2001 rediscovery of that species on an island in Australia. Then, living his beer glass, he uttered the celebrated line from the 1993 movie Jurassic Park: “Life, uh, finds a way.”

And this is the tantalizing thing when a species thought to be lost comes back, in effect, from the dead. It hints at rebirth in an era otherwise dominated by headlines about climate change and mass extinction. Scientists even refer to these rediscovered organisms as “Lazarus species,” after the man raised from the dead by Jesus Christ in the New Testament.

But finding lost species does not take a miracle, according to Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), a small Texas-based nonprofit. GWC is now launching an ambitious “Search for Lost Species” initiative to rediscover 1,200 species in 160 countries that have not been seen in at least 10 years. The first expeditions will launch this fall in pursuit of the 25 “most wanted” species, says GWC herpetologist Robin Moore, who is leading the effort.

Among the top 25: a pink-headed duck last seen in 1949 in Myanmar, a tree-climbing freshwater crab last observed in 1955 in the West African forests of Guinea and the world’s largest bee (with a wingspan of 2.5 inches) last sighted in 1981 in Indonesia. “For many of these forgotten species,” Moore says, “this is likely their last

chance to be saved from extinction.”

The plan is to work with international partners to put scientists in the field, with an initial fund-raising goal of $500,000. That’s not much—just $20,000 each for the 25 “most wanted” species, which have been missing in action for a collective 1,500 years. But Moore is optimistic, he says, because of his past experience leading a 2010 “Search for Lost Frogs” initiative. That effort, a collaboration between GWC and Conservational International, rediscovered only one of its “top 10” species in its first six months but found a total of 15 species over its first year as a result of 33 expeditions. In one case in Borneo, local researchers made repeated expeditions over eight months before eventually finding the missing frog higher up the mountain than it had ever been seen. “Some species,” Moore says, “just require persistence.”

To improve the odds of success, the plan for the new initiative is to put researchers in the field in places where recent evidence suggests a lost species may persist. For instance, Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, a spiny, egg-laying mammal, is known from only a single specimen collected in 1961 by a Dutch researcher in Indonesia’s Papua Province. But a 2007 expedition in the Cyclops Mountains there led by the Zoological Society of London spotted burrows, tracks and the sort of holes echidnas dig for worms. Local hunters have also reported sightings of the elusive creature. “We have been in touch with an Indonesian conservation group about setting up an array of camera traps in the area over a longer period,” Moore says, “to see if we can get a photograph.”

Other technologies could also make rediscoveries more likely. Sequencing the DNA in a body of water, a technique called environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling, can reveal the presence of certain fish or amphibians. Likewise, sequencing blood from mosquitoes or leeches, known as invertebrate DNA (iDNA) sampling, can reveal which species they have been feeding on. New mapping technologies can also combine high-resolution images from Google Earth with species data to identify an animal’s likely habitat more precisely.

Even without modern technology, species rediscoveries have been a relatively common occurrence. A 2011 study in Trends in Ecology & Evolution documented 351 such rediscoveries over the previous 122 years—an average of about three a year. They include such sensational cases as the 1938 discovery of a living coelacanth, at a time when this fish was presumed to have gone extinct with the dinosaurs; the 1966 discovery of Australia’s mountain pygmy possum, previously known only from bones found in a cave; and the 1951 rediscovery of the cahow, or Bermuda petrel, then thought to have been extinct since the 1620s.

In northern Australia a research team not connected to the GWC initiative is currently undertaking fieldwork with the equally sensational goal of rediscovering the thylacine, or “Tasmanian tiger,” which has been presumed extinct for the past 80 years. James Cook University ecologist Sandra Abell, who is leading the effort, rates the likelihood of success as “low” but “not impossible.” Even so, Richard Dawkins excitedly tweeted, “Can it be true? … Has Thylacinus been seen alive? And in mainland Australia not Tasmania? I so want it to be true.”

The reality of such rediscoveries, says John Zablocki, a biologist at The Nature Conservancy who is not involved with the GWC effort, is that wildlife biology suffers from “a gap in knowledge” about the behaviors and whereabouts of most species. “Our survey capacity is just so limited. Even here,” he says, of properties The Conservancy owns in the Mojave Desert, “we may have an ‘extinct’ vole” that is actually just missing.

Zablocki (who was the graduate student in the Reno bar conversation) wrote his master’s thesis, “The Return of the Living Dead,” on rediscoveries. The thesis recommended exactly the sort of focused rediscovery effort now being undertaken by GWC, partly for the potential to engage the public in what amounts to a wildlife detective story. “It’s still kind of tantalizing that we just don’t know what’s out there, even with our remote-sensing technology and DNA analysis,” Zablocki says, “and it does give us hope. Conservation is so fraught with doom-and-gloom stories that the opportunity to get things right a second time is also important. The flip side is that it can give people the sense that species can come back from extinction or that the extinction risk isn’t as serious as it really is,” he notes.

Both Zablocki and Moore argue, however, the excitement about rediscoveries tends to motivate conservation efforts. For instance, after researchers discovered a remnant population of 24 Lord Howe Island stick insects dwelling under a single bush on an island cliff face, conservationists launched a major captive-breeding program. As a result, the Melbourne Zoo hatched 16,000 eggs in 2016 and established insurance populations of the species at three other zoos. The rediscovery also helped motivate a program to eradicate species-killing invasive rats from the island group.

Rediscovery, says Moore, is “a very powerful motivator. The risk of always telling people how bad things are with the environment is that we instill despair. We’re trying to instill that glimmer of hope, to remind people that there is still a lot worth fighting for, and that the world is a wild and mysterious place.”

##

Richard Conniff is an award-winning science writer for magazines and a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times. His books include House of Lost Worlds (Yale University Press, 2016) and The Species Seekers (W.W. Norton, 2010).

April 6, 2017

As Ethiopia Reclaims the Nile, Egypt Dwindles

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Africa’s largest, is now nearing completion. (Photo: Zacharias Abubeker/AFP/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Yale Environment 360

Though politicians and the press tend to downplay the idea, environmental degradation is often an underlying cause of international crises — from the deforestation, erosion, and reduced agricultural production that set the stage for the Rwandan genocide of the 1990s to the prolonged drought that pushed rural populations into the cities at the start of the current Syrian civil war. Egypt could become the latest example, its 95 million people the likely victims of a slow motion catastrophe brought on by grand-scale environmental mismanagement.

It’s happening now in the Nile River delta, a low-lying region fanning out from Cairo roughly a hundred miles to the sea. About 45 or 50 million people live in the delta, which represents just 2.5 percent of Egypt’s land area. The rest live in the Nile River valley itself, a ribbon of green winding through hundreds of miles of desert sand, representing another 1 percent of the nation’s total land area. Though the delta and the river together were long the source of Egypt’s wealth and greatness, they now face relentless assault from both land and sea.

The latest threat is a massive dam scheduled to be completed this year on the headwaters of the Blue Nile, which supplies 59 percent of Egypt’s water. Ethiopia’s national government has largely self-financed the $5 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), with the promise that it will generate 6,000 megawatts of power. That’s a big deal for Ethiopians, three-quarters of whom now lack access to electricity. The sale of excess electricity to other countries in the region could also bring in $1 billion a year in badly needed foreign exchange revenue.

GERD can only begin to meet these promised benefits, however, by holding back river water that would otherwise pass down the Nile to Sudan and then Egypt, and that’s obviously a big deal for both those countries — so much so that, according to Wikileaks, government officials in Cairo at one point talked about aerial bombing or a commando raid to …

April 3, 2017

Black Hound at Sunset

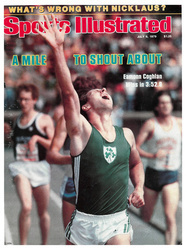

This isn’t quite the first piece I published in a national magazine, but it’s the first one that I felt good about. It ran in Sports Illustrated, which back then took an interest in the world beyond Big Four sports. I sent a copy to E.B. White, to thank him for some of the the things he had taught me about writing, and he replied, saying “when I got around to reading it, later, I could not put it down.” This piece also appeared in my story collection Every Creeping Thing (Holt 1998).

by Richard Conniff

The sun was shining over the Atlantic when I arrived at the end of what had been a wet, stormy September day. I was staying the night at a hostel on Crohy Head about five miles from Dunglow, County Donegal. Inside, there was a turf fire and tea, and though I had already put in many miles on foot, the sun drew me out of doors again as soon as I had warmed myself a bit.

The hostel stood on a high spot with pasturage running down to the rocks and the water. Clambering over a stone wall, I walked slowly down through the grass. A stream babbled nearby, though the overgrowth almost hid it completely. Distracted by the murmuring water, I didn’t notice until the last moment the black dog racing down on me. It ran with a crazy, bucketing speed, and it leaped up at me almost before I had spotted it.

I have always been good with dogs, and I found I was particularly compatible with those in the West of Ireland. It was easy. The dogs there generally look alike and share the same quiet temperament; they are bred to herd sheep. “You seldom get a cross sheep dog,” a Mayo farmer had told me, as his dog rested its head against my knee. I hadn’t met a cross one yet, and so I didn’t panic when the dog

came at me.

It twisted in midair, landed at my feet and was up again immediately, leaping and turning. Like a sheep dog, it didn’t growl or bark, but I’d never seen one so wild and frenetic. Most of them I had come across in Ireland were content to sit listening and watching in the corner of a field or to wait patiently in a farmhouse for their meal of potato skins and milk. I saw by the mad, happy look in this dog’s eyes that it wanted a tussle. I offered it my arm. Then I wrestled and boxed with it and spun it around, letting it leap for my hand and the sleeve of my jacket. It was skinny and stood only knee high, so I was able to toss it about without much effort.

The sheep dog started playing other games with me, trying to make me run. It charged me, cutting and bobbing. It dashed down the hill and then came back a bit to tease me on, leaping out of reach each time I drew near. After running in tight circles around me, it bolted out of sight, only to appear a few moments later on a knoll two fields away. Its speed and energy startled me. It didn’t leap the stone walls with the compact forward motion of a horse. Instead, it took them with an insane springiness that seemed to leave it suspended in the red sunlight, 1½ feet above the wall.

I followed the dog across the fields, playing the game. When I stopped to catch my breath by the ruins of a church, the dog darted in and out of the vacant doors and windows, calling me back to the chase. It drew me on insistently until we got to the bottom of the field, which surmounted a sheer, 30-foot cliff.

A finger of the Atlantic ran beneath the cliff and the sea whirled and spat and washed around the rocks below. I paused to take the scene in. The sun, a great red ball, was slowly dropping into the sea. It lit up the red-and-brown cliff face, the rich, green grass, the gray stone ruins. Everything in sight was timeless, as if it had not changed in the centuries since the Armada sailed past these shores.

But the dog had no interest in sightseeing. It ran down the irregular rocks to the sea as a house dog might go down the back stairs. It was as if the dog could have done it blindfolded. It stopped only to look at me curiously. Twice it came back up onto the grassy headland to urge me on. I didn’t move at first. I didn’t trust the way the sea rolled into the little inlet and then went sucking back out. Was it a rising or a falling tide? How deep was the water around the rocks?

Such considerations didn’t affect the dog, who ran down to the water’s edge and continued on, stepping from one rock to another, into the middle of the inlet, where the sea was all around it. It made the trip slowly, looking over its shoulder as if to instruct me. Then once again it returned to me on the headland. There was really nothing to be afraid of, I thought. The weather was fine. There was still plenty of daylight. The dog would be my guide.

I climbed down slowly, unsure of my footing. The dog ran ahead with its characteristic abandon, stopping at intervals for me to catch up. I slipped and fell once, and it came back to inspect me with its gray-blue eyes. It pronounced me well and then stood behind me, urging me on.

I looked again at the swirling water and at the clear sky. I thought of Ireland’s weather, “changeable as a baby’s bottom.” Only that afternoon, on the Bloody Foreland, the country’s northwestern tip, I had watched this same sea lashing at the rocky coast in a great, white, boiling fury. A blinding rain had whipped in over the low farmland, tearing at the hand-stacked oat ricks. “There’s nothing from here till you get to America,” one fellow had told me, “so the sea has plenty of room to work up a rage.”

From its perch on a rock a few feet away, the dog looked back at me expectantly. The red sun showed it handsomely, all black, with those penetrating eyes. It waited for me. I wondered, only half jokingly, if it was some agent of the sea gods, leading me away from the safety of land. I had been told of demon cats in Irish folklore. Were there demon dogs, too? In the un-Anglicized Irish, my family name (MacConduibh) means “Son of a Black Hound.” Was this dog the agent of some personal Irish destiny, some retribution due my ancestors who had lived in the West of Ireland a long time ago?

I stepped out onto the rock. The dog turned, and with that characteristic springiness, leaped one rock farther out. Then it turned and waited. When I hesitated too long, it came back to draw me on. And so I followed it from rock to rock. It wasn’t satisfied until I had come to the last rock in the little archipelago. We stopped, with the sea rushing around us and cliffs on either side, and at last it sat down like a sheep dog, staring quietly straight ahead.

I followed its gaze, peering anxiously into the west for a squall rolling in from America, but the Atlantic had taken on a glassy evening calm.

The dog was watching the sunset.

It was a perfect spot. At the mouth of the inlet there was no distraction, nothing to obstruct our view. The sun lit up a great red path straight across the sea. We watched silently as it settled down into the ocean. Then, in the dusk, the dog led me slowly back over the rocks and up onto the headland. Someone was calling when we reached the road. The dog’s ears went up, and we parted almost as abruptly as we had met.

END

P.S. The story ran in the July 9, 1979 issue of Sports Illustrated, and I was grateful that they did not decide that it had to wait till March because the subject matter was Irish. But coincidentally, the cover of that issue featured the Irish miler Eamonn Coghlin, who had just run a 3:52.6 indoor mile.

March 28, 2017

How Cleaning Up Coal Pollution Helped Beat My Daughter’s Asthma

A coal-fired power plant in Kentucky

Today’s the day the Trump Administration makes its bid to set the coal industry free, against all the basic research demonstrating that this will be terrible for both the climate and the health of the American people. It reminds me of a time, not so long ago, when wiser Republicans saw the value of basic research, and genuinely worked to make America a better country. I wrote what follows for the National Academy of Sciences, so its not a personal piece. But as I wrote, I was remembering that my daughter Clare had asthma all the time she was growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s. And as the the Clean Air Act Amendment of 1990 gradually came into effect, sharply reducing pollution from coal-fired power plants, Clare’s asthma went away. That’s an experience many other families have shared, without ever stopping to think that they owed their improving health to basic research by –of all people–economists.

by Richard Conniff/National Academy of Sciences

On the morning of June 13 1974, readers of The New York Times swirled their coffee and mulled the front-page headline, “Acid Rain Found Up Sharply in East.” A study in the journal Science was reporting that rainfall on the eastern seaboard and in Europe had become 100 to 1000 times more acidic than normal—even “in occasional extreme cases,” said the Times, “as acidic as pure lemon juice.” The analogy was a little misleading: Lemon juice is not nearly as corrosive as the nitric and sulfuric acids then raining down on the countryside. But it was enough to make acid rain a topic of anxious national debate.

Both the recognition of the problem and the eventual solution to it would be products of basic research, the one in physical science, the other in social science, neither directed at any narrow purpose. The journey from problem to solution would be tangled and difficult, across unmapped scientific and political territory, over the course of decades. Along the way, it would become apparent that acid rain was more serious than anyone suspected at first, threatening the health of tens of millions of Americans. The solution, when it came, would demonstrate the potential of basic research to be literally a lifesaver.

The authors of the Science study hadn’t set out to find acid rain. Their long-term project was aimed merely at understanding how forest ecosystems work, down to the chemical inputs and outputs. But the first rain sample they collected in the summer of 1963, at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire, was already surprisingly acidic. By the early 1970s, after almost a decade of corroborating research, they felt confident that acid deposition, both wet and dry, had become a significant regional problem, and a factor in declining forest productivity, fish kills, and the deterioration of buildings and bridges.

Roughly 70 percent of the problematic emissions came from power plant smokestacks, and the Times noted that “no widely accepted, reliable technology” was available to fix the problem. Critics were soon dismissing acid rain as an environmental hoax, with one federal official claiming any fix would cost $6000 for every pound of fish saved. But scientific evidence of damage, and public concern about it, continued to mount. By 1984 the federal Office of Technology Assessment had concluded that acid rain and the associated small particle smokestack emissions “have harmed lakes and streams, lowered crop yields, damaged man-made materials, decreased visibility, and might even threaten human health.”

By 1988, wet scrubbers using limestone to remove sulfur oxides from smokestacks seemed like the best remedy. But research put the likely capital cost at $400 million per power plant, or $20 billion just for the nation’s top 50 polluters. One approach at that point would have been for the government to issue regulations and order polluters to install the equipment needed to reduce emissions. But resistance had been building to that “command-and-control” style of addressing environmental issues. Expensive and time-consuming lawsuits were common in such cases. An impasse seemed likely, until a way around it emerged, surprisingly, from a line of pure economic theory pursued by academics over the course of a century.

The first step in that thinking was to recognize the importance of what we now call externalities. That is, transactions between two parties often cause benefits and harms to third parties, or to society, that should be part of the accounting but generally aren’t. The utilitarian philosopher Henry Sidgwick first articulated this idea, in his 1883 book The Principles of Political Economy. He did not suggest how to get anyone to pay for externalities.

British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou fleshed out the externality idea in his 1920 book The Economics of Welfare. For broad negative effects on society, he proposed a government tax proportionate to the damage. Such “Pigovian” taxes would in time become commonplace. The United States, for instance, imposed an excise tax in 1980 on hazardous chemicals, to support its Superfund cleanup work, and another on petroleum products, after the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster, for the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund. Politicians, pundits, and economists from Al Gore to Alan Greenspan continue today to advocate such a tax on carbon, as a means of addressing climate change.

But Pigou also elicited a scathing attack in 1960 for his “faulty view of the facts” and “mistaken” economic analysis. In his paper “The Problem of Social Cost,” economist Ronald Coase, then at the University of Virginia, described government-imposed solutions as crude and inefficient. Nor was he impressed by legal remedies, often based on points of law that seemed, to an economist, “about as relevant as the colour of the judge’s eyes.” Instead, Coase advocated measures that would make it easier for the affected parties to negotiate and allocate costs in the marketplace. He later admitted that he didn’t recognize the broader implications of what he had written until a colleague pointed them out afterward.

But it was enough to influence the Canadian economist John H. Dales. He began his slender 1968 book Pollution, Property & Prices with the engaging promise that it would contain “virtually no factual information and very little in the way of outraged denunciation of evil.” Instead, he declared, “Let us try to set up a ‘market’ in ‘pollution rights.’”

Using the example of water pollution in Lake Ontario, Dales proposed that a regional board set an overall limit, or cap, on pollution and divide up that cap in the form of annual pollution allowances distributed to major polluters. Some companies might buy additional allowances on the marketplace and even increase their pollution. But others would instead choose to improve their wastewater treatment, paying for it in part by selling the allowances they no longer need. The board might later choose to lower (or raise) the cap, leaving the price for pollution allowances to adjust in the marketplace. It was the system now known as cap-and-trade. But it was still a long way from being a practical reality.

In the early 1970s, an environmental economist named Dan Dudek became interested in behaviorally-oriented approaches to pollution problems. Dudek had learned during a stint working on pollution issues at the U.S. Department of Agriculture that “command-and-control–telling people what to do–is not exactly the way to win friends when dealing with farmers. That part of it got burned off me pretty quickly.” Teaching at the University of Massachusetts in the early 1980s, Dudek turned to Dales both for his understanding of human nature and because he thought the directness and clarity of his writing might appeal to undergraduate students. Later, when he went to work for the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Dudek took Dales’ marketplace approach with him out of the realm of scholarship and into politics.

Incoming President George H. W. Bush had promised to be “the environmental president.” When EDF suggested that fixing acid rain with a marketplace approach would fulfill that commitment, Bush’s chief counsel Boyden Gray latched onto the idea, which also fit Republican sensibilities. Utility executives loudly objected. So did many traditional environmentalists, who saw emissions trading as a way for polluters to buy their way out of fixing the problem. But the marketplace in acid rain emissions became law in the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, written in part by Dudek. It set an ambitious goal of cutting those emissions in half, by 10 million tons.

Would it work? No one knew for sure until the program took effect in 1995. Soon after, a federal policymaker browsing through emissions reports stopped dead at an Ohio power plant that had been a major polluter. Almost overnight, it had cut emissions 95 percent, from 380,000 tons of sulfur dioxide annually down to 19,000. Other utilities soon joined in, and the program hit its 10-million-ton target in 2006. Allowing utilities the freedom to find the most cost-effective way forward for individual power plants—and profit from emissions allowances they no longer needed–proved to be a major factor in driving program costs down by at least 15 percent below the cost of the command-and-control alternative. The acid rain cleanup eventually cost less than $2 billion a year, a third of the federal government’s 1990 estimate.

Rainfall in the Eastern seaboard is less acidic, and visibility has improved dramatically. Gene E. Likens, a retired ecologist who was among the first to spot the acid rain problem in 1963 (and still continues his research at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest), cautions that soils and forests will take much longer to recover. But human health has turned out to be an unexpected beneficiary, because of the belated recognition that fine particles in acid rain emissions were finding their way into peoples’ lungs, causing increased sickness and death from conditions like asthma and bronchitis. The acid rain program now produces benefits estimated at up to $116 billion a year, mostly in avoided mortality.

Building on the American success with cap-and-trade, the European Union in 2005 launched a trading scheme to reduce climate change emissions. That program has at times stumbled badly, in part because it issued too many allowances at first, but also because reducing carbon emissions has turned out to be a much larger and more difficult proposition. Even so the EU program appears to have stabilized and gained acceptance in the business community. It now covers 11,500 power plants, factories, and other facilities in 31 countries.

[image error]

Asthma inhalers: Due for a comeback?

In 2009, Congress declined to establish such a cap-and-trade program for carbon emissions in the United States. But that same year, a group of Eastern states representing a fifth of the nation’s gross domestic product launched a regional cap-and-trade program. California and three Canadian provinces are now banding together on a similar program. And in September 2015, China’s president came to Washington, D.C., to announce plans to implement cap-and-trade on carbon emissions nationwide in 2017. It will be the largest cap-and-trade program in the world.

None of this would have happened without what Dan Dudek, who is advising China, called “that initial spark,” meaning the idea that emerged from the theories of Pigou, Coase, and Dales. “It’s hard to imagine that coming from government officials bogged down” in the day-to-day details of managing programs. For “big transformative ideas” like a marketplace in pollution, it takes basic research, broadly defined and insulated from short-term considerations. For Dudek, there is consolation in knowing that China at least will still profit from such basic research, even as the United States turns away.

Richard Conniff is a contributing opinion writer to the New York Times, and the author of The Species Seekers, and other books. Find out more here.

March 18, 2017

To End Bushmeat Hunting, Let Them Eat Chickens

(Photo:Jeannie O’Brien/Flickr)

by Richard Conniff/The New York Times

The idea that the humble chicken could become a savior of wildlife will seem improbable to many environmentalists. We tend to equate poultry production with factory farms, downstream pollution and 50-piece McNugget buckets.

In much of the developing world, though, “a chicken in every pot” is the more pertinent image. It’s a tantalizing one for some conservationists because what’s in the pot there these days is mostly trapped, snared or hunted wildlife — also called bushmeat — from cane rats and brush-tailed porcupines to gorillas.

Hunting for dinner is of course what humans have always done, the juicier half of our hunter-gatherer origins. In many remote forests and fishing villages, moreover, it remains an essential part of the cultural identity. But modern weaponry, motor vehicles, commercial markets and booming human populations have pushed the bushmeat trade to literal overkill — an estimated 15 million animals a year taken in the Brazilian Amazon alone, 579 million animals a year in Central Africa, and onward in a mad race to empty forests and waterways everywhere.

A study last year identified bushmeat hunting as the primary threat pushing 301 mammal species worldwide toward extinction. The victims include bonobo apes, one of our closet living relatives, and Grauer’s gorillas, the world’s largest. (The latter have recently lost about 80 percent of their population, hunted down by mining camp crews with shotguns and AK-47s. Much of the mining is for a product integral to our cultural identities, a mineral used in

the circuit boards of our cellphones.) The victims also include at least three species humans have probably already eaten into extinction: the kouprey, a water-buffalo-size animal from Southeast Asia; the Wondiwoi tree kangaroo from Papua; and a squirrel-size hutia from Cuba.

Bushmeat hunting also often leaves large carnivores without prey animals to eat, one reason so-called protected areas across Africa now harbor only a quarter as many lions as they could, according to a recent study in the journal Biological Conservation. The lions and other predators frequently get caught in wire snares set out for smaller animals. Some animals escape, minus a limb, and

To read the full article, click here.

Richard Conniff is a contributing opinion writer to the New York Times, and the author of The Species Seekers, and other books. Find out more here.

March 14, 2017

Climate Change Complicates the Whole Dam Debate

Oroville Dam in California. (Photo: California National Guard)

by Richard Conniff/ScientificAmerican.com

With California now on track to have the rainiest year in its history—on the heels of its worst drought in 500 years—the state has become a daily reminder that extreme weather events are on the rise. The recent near-collapse of the spillway at California’s massive Oroville Dam has put an exclamation point on the potentially catastrophic risks.

More than 4,000 dams in the U.S. are now rated unsafe because of structural or other deficiencies. Bringing the entire system of 90,000 dams up to current standards would cost about $79 billion, according to the Association of State Dam Safety Officials. Hence, it has become increasingly common to demolish problematic dams, mainly for economic and public safety reasons, and less often to open up old habitats to native fish. About 700 dams have come down across the U.S. over the past decade, with overwhelmingly beneficial results for river species and ecosystems.

Now, though, a new study in Biological Conservation takes the science of dam removal in an unexpected direction. While acknowledging that reopening rivers usually leads to “increased species richness, abundance and biomass,” a team of South African and Australian authors argues

that in some cases threatened species may actually benefit from keeping existing dams intact.

The idea for the study arose because both South Africa and Australia are now experiencing “an incredibly dry period,” says co-author Olaf Lawrence Weyl, a specialist in endangered fish with the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity. Many native fish species have been “pushed right back into headwater streams” by competition with alien fishes, typically introduced for sportfishing and by “dewatering of entire rivers” to supply irrigation water for crops, Weyl adds. In some cases, the streams and reservoirs backed up behind dams are the only remaining aquatic refuges for endangered species.

The prolonged drought has been especially intense in southwestern Australia. Even before modern development, many streams there naturally dried up for much of the year, confining endemic fishes to a few disconnected pools. Two species actually evolved to burrow into the mud and become dormant in the dry season, a strategy called aestivation. But since the 1970s median stream flow has declined by half, with further declines predicted over this century. Even the aestivating fishes have suffered sharp losses—but they have managed to hang on, along with other endemic species, in artificial ponds created by dams. Removing these dams “for economic reasons without proper evaluation of their potential ecological value,” the co-authors warn in the new study, “may therefore cause a major loss of vital refuge habitat.” In some cases, removal of dams could also open upstream habitat to introduced sport fish, which typically kill or otherwise outcompete native species.

“This isn’t a call to stop dam busting, or a one-size-fits-all scenario,” Weyl explains. “What we are saying is that there are sites in some regions, particularly dry regions, where dams could have important conservation value, and that needs to be taken into account when planning removal of dams.”

Many U.S. scientists and conservationists have responded to the new study with one eyebrow raised. The argument “sounds plausible for the particular cases they’re talking about,” says Jeffrey Duda, a research ecologist for the U.S. Geological Survey’s Western Fisheries Research Center. But in the U.S. most dam removals occur in less arid regions, where “very few cases meet the criteria in the article.” The co-authors “are very careful and specific to acknowledge that the vast majority of dams have negative impacts on the environment,” adds Shawn Cantrell, Pacific Northwest director for Defenders of Wildlife, a conservation nonprofit organization.

[image error]

Sockeye at swim (Photo: Katrina Liebich/USFWS)

Moreover, if climate change is sometimes a reason to preserve existing dams, it can also make the argument for removing other dams more urgent, says Scott Bosse, a former fisheries biologist who is now Northern Rockies director for nonprofit American Rivers. Last year a federal judge tossed out a proposal for the continuing operation of hydropower dams in the Columbia River Basin, saying the plan failed to take adequate account of climate change’s “potentially catastrophic impact” on populations of salmon and steelhead (sea-run, or anadromous, rainbow trout), which are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Removing the dams, Bosse says, would reopen “some of the coldest, highest-elevation spawning habitat for anadromous fish”—a move that could be critical to their survival.

But the new study is correct, says Bosse, in saying some dams can also serve as essential barriers to invasive species. The Hungry Horse Dam in northwestern Montana, for instance, keeps lake trout—introduced for sportfishing—out of the south fork of the Flathead River, preserving “our best native trout habitat,” Bosse says. “Everything upstream is bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout,” native species that have lost much of their original habitat to logging, grazing, mining and introduced nonnative species. Likewise, dams in the Great Lakes region play a critical role in keeping invasive sea lampreys out of potential spawning grounds.

“Not only are some dams not coming out,” Bosse says, “there are barriers being installed to protect habitat. Right here in Montana in any given year, we probably see five or 10 such projects, and it’s similar across the West.” In such cases, the U.S. Forest Service typically collaborates with a state fish and game department to create an artificial waterfall on a headwater stream or to erect a six- or 10-foot concrete dam, “just high enough to prevent brook trout or brown trout from invading upstream habitat.”

But this practice involves a trade-off, a 2009 study in Biological Conservation warned: Isolating native fish with protective barriers also risks cutting them off from old migratory routes, preventing natural gene flow from one population to another, and increasing the likelihood of extinction. Moreover, anglers may simply introduce a favorite nonnative fish above a barrier because they think it looks like a good place to fish. The 2009 study warned against the danger of making decisions about a dam or barrier installation subjectively, based on “personal philosophy or simply what has worked elsewhere.”

For Weyl and the other co-authors of the new “dam busting” study, that seems to be the bottom line—the debate about dams has always been prone to ideological or exclusively economic arguments. The greater challenge, they suggest, is to come to terms, dam by dam, with the ecological nuances.

March 7, 2017

Celebrating Psychedelica: Live on The Leonard Lopate Show

Swims like a drunken sailor. (© David Hall/seaphotos.com)

I was a guest this afternoon on “The Leonard Lopate Show” on WNYC in New York, talking about species discovery. The and listening to it is definitely better than a sharp stick in the eye. (A courageous listener called in to tell one of the other guests that he didn’t like the sound of her voice. Thank goodness, I didn’t have a call-in segment.)

At one point, I talked about a favorite new species from 2009 named psychedelica. Here’s the background, from my previous post on the discovery:

Once again, science makes my day. Researchers have discovered a wonderful new fish in shallow water off the Indonesian island of Ambon, much visited by great naturalists of the past including Alfred Russel Wallace. And this one just makes you want to keep looking and looking, even in the same places everybody else has looked before, because Mother Nature is such a relentless joker.

University of Washington scientist Ted Pietsch has dubbed the discovery Histiophryne psychedelica because, well, just look at that face. Or consider its swimming behavior, which also suggests that it has been dabbling in mind-altering drugs. It doesn’t so much

swim as bounce off the bottom, using its fins to push off the seafloor and jetting itself forward by firing water from its tiny gill openings. Check out the QuickTime video.

It hops along with so little control that, according to the press release, it looks as if it “should be cited for DUI.” Like other frogfish, it also uses its pectoral fins like feet to go stumping along the bottom.

Fortunately, psychedelica is covered with thick folds of skin to keep it from getting punctured as it bangs along the coral reef. It also has a flattened face with eyes directed forward, something Pietsch, with 40 years of experience studying and classifying fishes, has never seen before in frogfish. He speculates that the species may have binocular vision, overlapping in front, as it does in humans. Most fish, with eyes on either side of the head, don’t have vision that overlaps; instead they see different things with each eye.

Toby Fadirsyair, a guide in Ambon, and Buck and Fitrie Randolph, co-owners of Maluku Divers, first spotted the fish and alerted Pietsch. David Hall, a wildlife photographer and owner of seaphotos.com, speculates that the fish came by its crazy coloring by mimicking corals.

Here’s the citation: A BIZARRE NEW SPECIES OF FROGFISH OF THE GENUS HISTIOPHRYNE (LOPHIIFORMES: ANTENNARIIDAE) FROM AMBON AND BALI, INDONESIA Theodore W. Pietsch, Rachel J. Arnold, and David J. Hall Copeia, 2009(1):37−45, 18 February 2009

March 5, 2017

Fantastic Bloody Pigeon! (Or Hitchcock Nightmare)

Bloody pigeon (Photo: Wellcome Images/Scott Echols)

The Wellcome Trust presents an annual award for scientific imagery, and two of this year’s winners (above and below) caught my eye for the new ways in which they reveal the natural world. Think of the one above as new insight into the cardiovascular system of living (and extinct) dinosaurs. Or just a bloody pigeon.

Here’s how The Guardian‘s Nicola Davis describes it:

Open-beaked against a jet-black background, the image of a bird leaps forth, a frenzy of red-and-white squirming lines hinting at its form. It looks like a still from a Hitchcockian nightmare. “It looks so cross, sort of squawking at you,” says Catherine Draycott, head of Wellcome Images.

In fact, the eerie shot is the product of

data captured during a CT scan; the hectic lines are the blood vessels inside a humble pigeon. “It is fascinating because of the way it shows the incredible density of blood vessels around the collar area, around the base of the neck,” says Draycott, pointing out the secret of the pigeon’s ability to regulate its internal temperature.

The picture was captured by Scott Echols, a veterinarian and president of Scarlet Imaging, as part of an ongoing endeavour known as the Grey Parrot Anatomy Project, which aims to develop ways to aid diagnosis and treatment for a host of animals, from birds to humans.

But the image isn’t just an arresting testament to the ingenuity of mother nature – it is also a tribute to scientific innovation. As Echols explains, using CT scans and contrast agents (substances to improve the visibility of things inside a body) to map blood vessels is a tricky business. “I had a student and we were working with what was considered at the time the best agent to look at the cardiovascular system,” he says. “And at some point the material exploded – it exploded all over me and, more concerning, all over my student – and left a mark on the wall like a crime scene where you have a body and a chalk outline.” Even more worrying, the contrast agent was toxic. “It was a mixture of lead, cadmium, mercury – horrible stuff,” says Echols.

In a bid to find a non-toxic alternative, Echols began concocting various experimental mixtures. The result was a contrast agent known as BriteVu. “That pigeon represents one of the earlier images after we figured out how to get the formula right,” says Echols. “It circulates through all the blood vessels to the capillary level, so you can see every single capillary in the body.” Echols says that the image is limited only by the capability of the CT scanner. “That particular pigeon was scanned at 100 microns, so you are seeing a fraction of the vessels that are there,” he says. “If we were to scan it in greater detail you’d see even finer vessels.”

The upshot is a technique that offers the chance to explore cardiovascular systems in three dimensions. But the success hasn’t been limited to birds. “We ended up testing the product on different animals and since then we have discovered anatomy no one knew existed,” says Echols, adding that all animals used in the project are already diagnosed as having terminal conditions.

But while the image, and the technique behind it, is shedding new light on anatomy, Echols, a former wildlife artist, hopes it will also captivate those outside the lab. “One of the beauties of art is that it brings out something inside of you maybe you didn’t even know was there, a curiosity, a past memory – whatever it may be,” he says. “I hope it brings out that inner curiosity that I believe is in all of us.”

To find out about the Hawaiian bobtail squid, below, check out the Guardian article.

[image error]

(Photo: Wellcome Images/Macroscopic Solutions)

February 23, 2017

An American Catfish En Route to Extinction

The last of a North American heritage (Photo: William Radke)

by Richard Conniff/Yale Environment 360

It’s the simple declarative starkness of the sentence that catches the eye: “Extinction in the United States is predicted by 2018.” The species in question is the Yaqui catfish, which few Americans have ever heard of, much less seen (or eaten). It is, however, the only native catfish west of the Continental Divide, capable of growing up to 2 feet in length, with the familiar whiskery barbels drooping down from its chin and the flattened underside characteristic of the bottom-dwelling catfish way of life.

The remaining U.S. population, in and around the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge in southeastern Arizona, has been declining by 15 percent a year, according to a new study in the journal Biological Conservation. That decline has continued even as a cooperative restoration effort by federal officials and private landowners has proved highly successful at protecting other aquatic species there. But for the catfish, with population recruitment “essentially zero” (meaning no younger generations surviving), the co-authors conclude that the last few elderly individuals still hanging on represent the end of the species in this country.

Moreover, the threat of U.S. extinction coincides with trouble for the larger Yaqui catfish population in northern Mexico. Its extensive habitat running southwest from the border down to the Gulf of California is now experiencing the same damming of rivers and draining of aquifers that occurred earlier on the U.S. side of the border. Introduction of nonnative channel catfish throughout the Mexican range also threatens to hybridize the last remnants of the Yaqui catfish into oblivion.

The threat to survival of the species coincides with a move in the Republican-dominated U.S. Congress to “modernize” the Endangered Species Act, under which the Yaqui catfish is protected as threatened with extinction. In a hearing last week, Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY) proposed to eliminate “the red tape and the bureaucratic burdens that have been impacting our ability to create jobs” and impeding land management plans, housing development, and cattle grazing.

To read the rest of the story, click here.

February 17, 2017

The Hunger Gains: Calorie Restriction Shows Anti-Aging Benefits

Note: Almost 40 years ago (!) I wrote a piece on anti-aging research. Part of it was about the fasting diet (aka severe calorie restriction or CR). The article featured Roy Walford, a pioneer of that research at UCLA. Walford did not merely research CR, he also practiced it, and he looked emaciated to me. He later became part of the Biosphere 2 experiment of the early 1990s, which turned into a prolonged CR experiment for everyone. Walford came out of it with his health broken, and died in 2004 at 79, about normal life expectancy then. So I came to the latest research on CR with a lot of caveats in mind.

by Richard Conniff/Scientific American

The idea that organisms can live longer, healthier lives by sharply reducing their calorie intake is not exactly new. Laboratory research has repeatedly demonstrated the anti-aging value of calorie restriction (or CR), in animals from nematodes to rats—with the implication that the same might be true for humans.

In practice though, permanently reducing calorie intake by 25 to 50 percent or more sounds to many like a way to extend life by making it not worth living. Researchers have also warned that what works for nematodes or rats may not work—and could even prove dangerous—in humans, by causing muscle or bone density loss, for example.

But now two new studies appear to move calorie restriction from the realm of wishful thinking to the brink of practical, and perhaps even tolerable, reality. Writing in Nature Communications, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the National Institute on Aging reported

last month that chronic calorie restriction produces significant health benefits in rhesus monkeys—a primate with humanlike aging patterns—indicating “that CR mechanisms are likely translatable to human health.” The researchers describe one monkey they started on a 30 percent calorie restriction diet when he was 16 years old, late middle age for this type of animal. He is now 43, a longevity record for the species, according to the study, and the equivalent of a human living to 130.

In the second study, published this week in Science Translational Medicine, a research team led by gerontologist Valter Longo at the University of Southern California (U.S.C.) suggests it is possible to gain anti-aging benefits without signing up for a lifetime of hunger. Instead, a “fasting-mimicking diet,” practiced just five days a month for three months—and repeated at intervals as needed—is “safe, feasible and effective in reducing risk factors for aging and age-related diseases.”

Some researchers, however, still find the calorie-restriction argument unpersuasive. Leslie Robert, a biochemist and physician at the University of Paris who was not involved in the two new studies, says pharmaceutical approaches offer greater anti-aging potential than “inefficient and apparently harmful” diets. The important thing, adds Luigi Fontana, a longevity researcher at the Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis who also was not involved in the new work, is “if you’re doing a healthy diet, exercising, everything good, without doing anything extreme, without making life miserable by counting every single calorie.”

Rozalyn Anderson, a researcher in the Wisconsin study, does not necessarily disagree. “Life is difficult enough without engaging in some bonkers diet,” she says. “We really study this as a paradigm to understand aging. We’re not recommending people do it.” The combined results in the Nature Communications paper show aging is “malleable” in primates, she explains, and that “aging itself presents a reasonable target for intervention.” Whereas conventional medicine views aging as a fight against cancer, cardiovascular issues, neural degeneration and other diseases, she adds, calorie restriction “delays the aging and vulnerability. Instead of going after diseases one at a time, you go after the underlying vulnerability and tackle them all at once.”

Despite her reservations about recommending CR, Anderson praised the work of the research team in the Science Translational Medicine study for “pushing this forward for possible application in clinics.” In that study, test subjects followed a carefully designed 50 percent calorie restricted diet (totaling about 1,100 calories on the first day and 70 percent (about 700 calories) on the next four days, then ate whatever they wanted for the rest of the month.

Longo, the gerontologist at U.S.C., says the underlying theory of the on-again/off-again approach is that the regenerative effects of the regimen occur not so much from the fasting itself as from the recovery afterward. By contrast, long-term, uninterrupted calorie restriction can lead to the sort of negative effects seen in extreme conditions like anorexia.

The calorie-restricted diet in Longo’s study was 100 percent plant-based and featured vegetable soups, energy bars, energy drinks and a chip snack as well as mineral and vitamin supplements. It included nutrients designed to manipulate the expression of genes involved in aging-related processes, Longo explains. (Longo and U.S.C. are both owners of L-Nutra, the company that manufactures the diet. But he says he takes no salary or consulting fees from the company and has assigned his shares to a nonprofit organization established to support further research.)

Even the five-day-a-month calorie restriction regimen was apparently a struggle for some test subjects, resulting in a 25 percent dropout rate. But health benefits in the form of decreased body mass and better levels of glucose, triglycerides and cholesterol, along with other factors, showed up after the third month and persisted for at least three months—even after subjects had returned full-time to a normal diet. Notably, given concerns about other forms of calorie restriction, lean muscle mass remained unchanged.

The benefits were greater for people who were obese or otherwise unhealthy, Longo says. But those individuals might also need to repeat the five-day regimen as often as once a month to the point of recovery, he adds, whereas individuals who are already healthy and athletic might repeat it just twice a year.

Neither of the two new studies argues the benefits of CR necessarily add up to a longer life. Longevity in humans is still an unpredictable by-product of our myriad variations in individual biology, behavior and circumstance. The objective, according to researchers, is merely to make the healthy portion of our lives last longer.